Submitted:

10 December 2024

Posted:

11 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

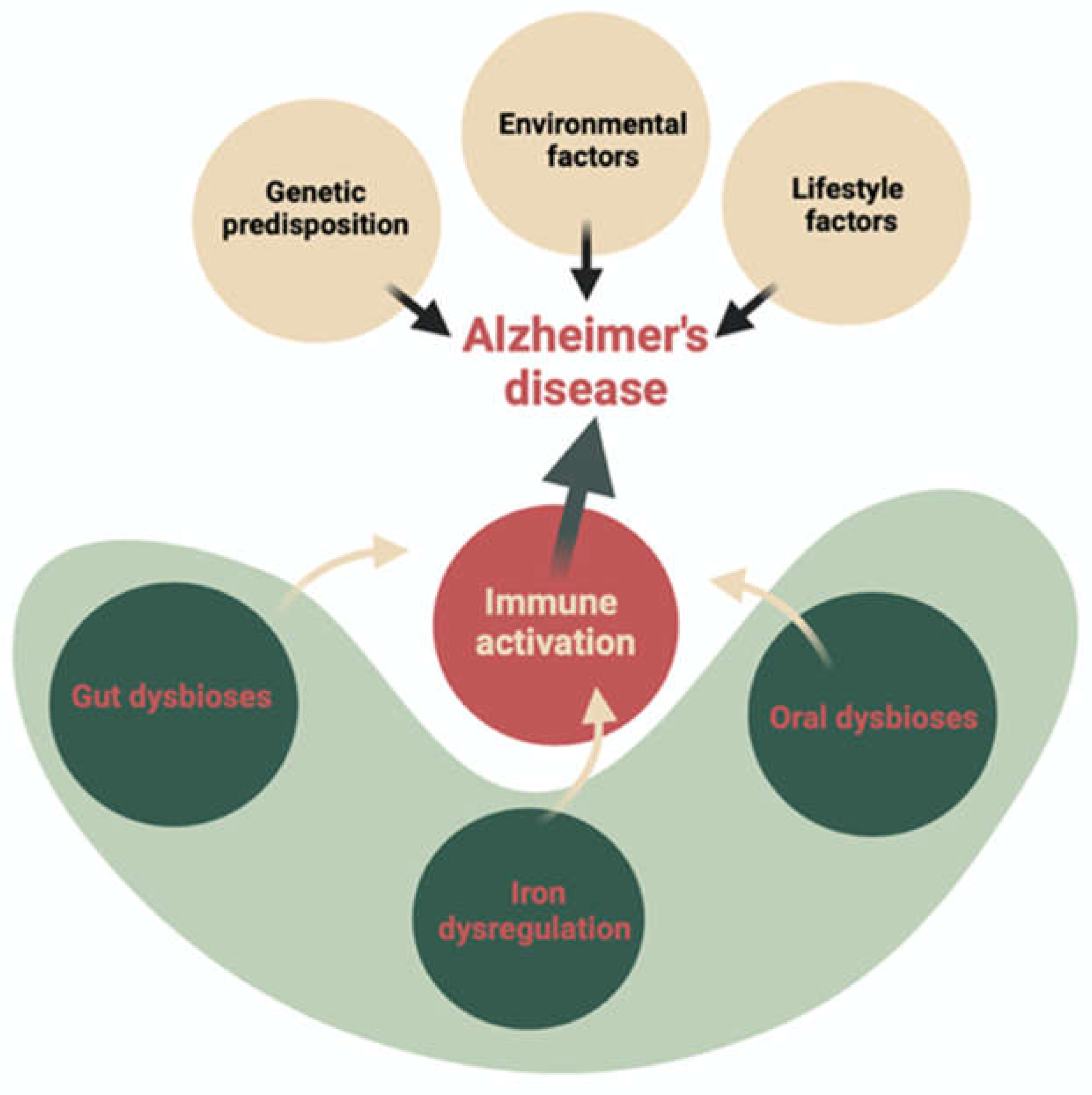

1. Introduction

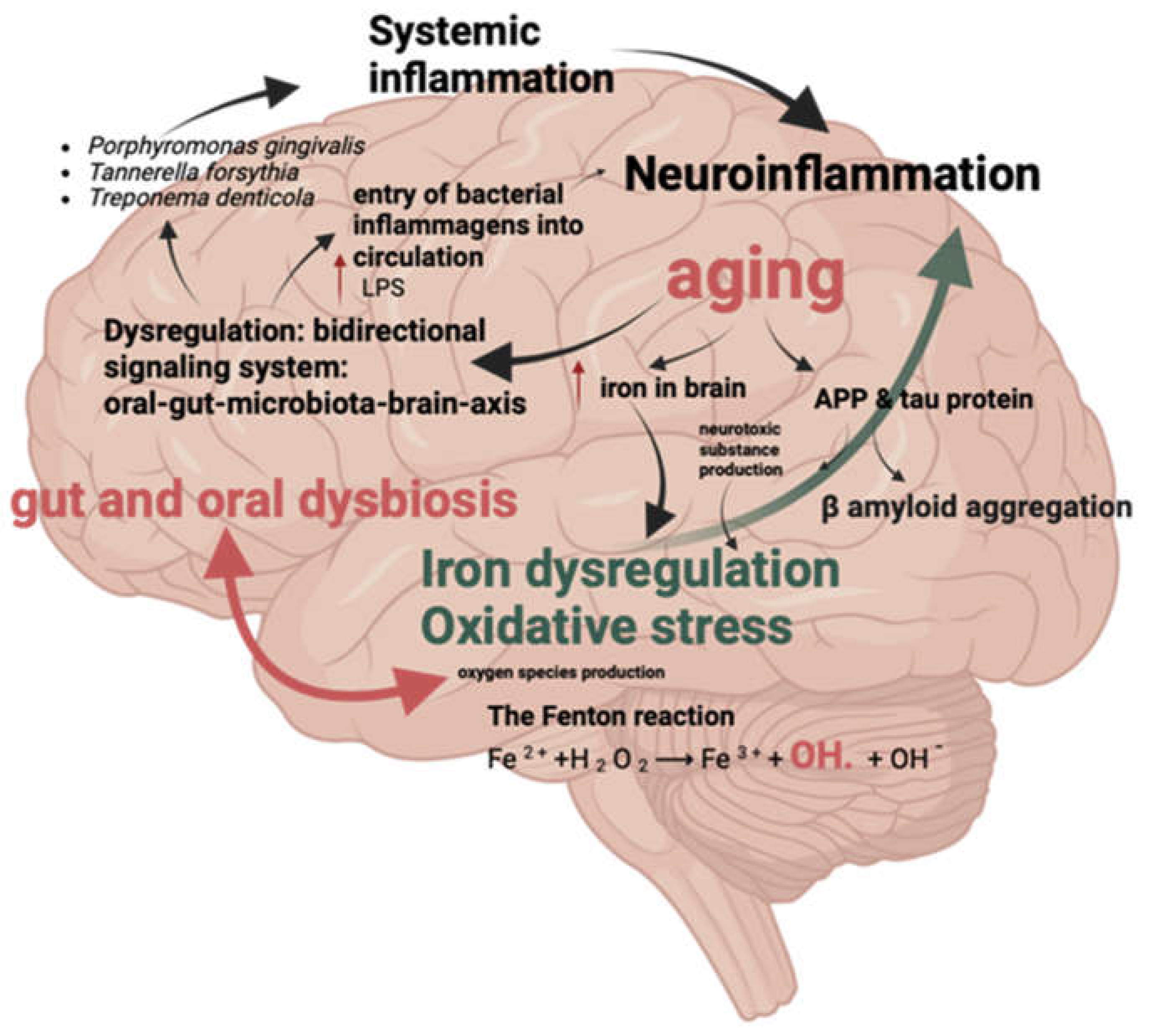

2. The Role of Iron, Oxidative Stress Ferroptosis, and Systemic Inflammation in AD Pathomechanism

2.1. Role of Iron

2.2. Oxidative Stress and Ferroptosis Promoting Inflammation in Neurodegeneration?

3. The Microbiota and Microbiome as a Potential Source of Excess Iron and Inflammatory Biomarkers in the Context of Alzheimer’s Disease

3.1. Bi-Directional Communication Between Gut Microbiome and Brain

3.2. Iron Homeostasis Is Associated with the Microbiome

4. Correlation Between Intestinal and Oral Dysbiosis and the Number of Free Bacterial Antigens

4.1. Gut-Microbiota

4.2. Oral Microbiota

4.3. Oral and Gut Dysbiosis Factors Promoting Neuroinflammation

4.4. Bacterial Antigens

4.5. Lipopolysaccharide—Endotoxin

5. Therapeutic Possibilities and Pharmaceutical Interventions

5.1. Iron Chelation

5.2. Antibiotics and Probiotics

5.3. Faecal Microbiota Transplantation

5.4. Additional Therapeutic Options

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scheltens P, De Strooper B, Kivipelto M, Holstege H, Chételat G, Teunissen CE, et al. Alzheimer’s disease. The Lancet 2021;397:1577–90. [CrossRef]

- Nichols E, Steinmetz JD, Vollset SE, Fukutaki K, Chalek J, Abd-Allah F, et al. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health 2022;7:e105–25. [CrossRef]

- Chandra S, Sisodia SS, Vassar RJ. The gut microbiome in Alzheimer’s disease: what we know and what remains to be explored. Mol Neurodegener 2023;18. [CrossRef]

- Gaweł M, Potulska-Chromik A. Choroby neurodegeneracyjne: choroba Alzheimera i Parkinsona. 2015.

- Friedland RP, McMillan JD, Kurlawala Z. What are the molecular mechanisms by which functional bacterial amyloids influence amyloid beta deposition and neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative disorders? Int J Mol Sci 2020;21. [CrossRef]

- Selkoe DJ, Hardy J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol Med 2016;8:595–608. [CrossRef]

- Shcherbinin S, Evans CD, Lu M, Andersen SW, Pontecorvo MJ, Willis BA, et al. Association of Amyloid Reduction after Donanemab Treatment with Tau Pathology and Clinical Outcomes: The TRAILBLAZER-ALZ Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurol 2022;79:1015–24. [CrossRef]

- Frisoni GB, Altomare D, Thal DR, Ribaldi F, van der Kant R, Ossenkoppele R, et al. The probabilistic model of Alzheimer disease: the amyloid hypothesis revised. Nat Rev Neurosci 2022;23:53–66. [CrossRef]

- Gulisano W, Maugeri D, Baltrons MA, Fà M, Amato A, Palmeri A, et al. Role of Amyloid-β and Tau Proteins in Alzheimer’s Disease: Confuting the Amyloid Cascade. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2018;64:S611–31. [CrossRef]

- Gulisano W, Maugeri D, Baltrons MA, Fà M, Amato A, Palmeri A, et al. Role of Amyloid-β and Tau Proteins in Alzheimer’s Disease: Confuting the Amyloid Cascade. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2018;64:S611–31. [CrossRef]

- Ashrafian H, Zadeh EH, Khan RH. Review on Alzheimer’s disease: Inhibition of amyloid beta and tau tangle formation. Int J Biol Macromol 2021;167:382–94. [CrossRef]

- Kim AC, Lim S, Kim YK. Metal ion effects on Aβ and tau aggregation. Int J Mol Sci 2018;19. [CrossRef]

- Masaldan S, Bush AI, Devos D, Rolland AS, Moreau C. Striking while the iron is hot: Iron metabolism and ferroptosis in neurodegeneration. Free Radic Biol Med 2019;133:221–33. [CrossRef]

- Ndayisaba A, Kaindlstorfer C, Wenning GK. Iron in neurodegeneration—Cause or consequence? Front Neurosci 2019;13. [CrossRef]

- Wang C, Wang Z, Zeng B, Zheng M, Xiao N, Zhao Z. Fenton-like reaction of the iron(ii)-histidine complex generates hydroxyl radicals: Implications for oxidative stress and Alzheimer’s disease. Chemical Communications 2021;57:12293–6. [CrossRef]

- Zeidan RS, Han SM, Leeuwenburgh C, Xiao R. Iron homeostasis and organismal aging. Ageing Res Rev 2021;72. [CrossRef]

- Stadlbauer V, Engertsberger L, Komarova I, Feldbacher N, Leber B, Pichler G, et al. Dysbiosis, gut barrier dysfunction and inflammation in dementia: A pilot study. BMC Geriatr 2020;20. [CrossRef]

- Zenobia C, Darveau RP. Does Oral Endotoxin Contribute to Systemic Inflammation? Frontiers in Oral Health 2022;3. [CrossRef]

- Lukiw WJ. The microbiome, microbial-generated proinflammatory neurotoxins, and Alzheimer’s disease. J Sport Health Sci 2016;5:393–6. [CrossRef]

- Quigley, Eamonn M.M. Microbiota-Brain-Gut Axis and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2017;17. [CrossRef]

- Rusu IG, Suharoschi R, Vodnar DC, Pop CR, Socaci SA, Vulturar R, et al. Iron supplementation influence on the gut microbiota and probiotic intake effect in iron deficiency—A literature-based review. Nutrients 2020;12:1–17. [CrossRef]

- Das NK, Schwartz AJ, Barthel G, Inohara N, Liu Q, Sankar A, et al. Microbial Metabolite Signaling Is Required for Systemic Iron Homeostasis. Cell Metab 2020;31:115-130.e6. [CrossRef]

- Holbein BE, Lehmann C. Dysregulated Iron Homeostasis as Common Disease Etiology and Promising Therapeutic Target. Antioxidants 2023;12. [CrossRef]

- Levi S, Ripamonti M, Moro AS, Cozzi A. Iron imbalance in neurodegeneration. Mol Psychiatry 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ni S, Yuan Y, Kuang Y, Li X. Iron Metabolism and Immune Regulation. Front Immunol 2022;13. [CrossRef]

- Elstrott B, Khan L, Olson S, Raghunathan V, DeLoughery T, Shatzel JJ. The role of iron repletion in adult iron deficiency anemia and other diseases. Eur J Haematol 2020;104:153–61. [CrossRef]

- Peng Y, Chang X, Lang M. Iron homeostasis disorder and alzheimer’s disease. Int J Mol Sci 2021;22. [CrossRef]

- Gutteridge JMC, Halliwell B. Mini-Review: Oxidative stress, redox stress or redox success? Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2018;502:183–6. [CrossRef]

- Mayneris-Perxachs J, Moreno-Navarrete JM, Fernández-Real JM. The role of iron in host–microbiota crosstalk and its effects on systemic glucose metabolism. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2022;18:683–98. [CrossRef]

- Rosell-Díaz M, Santos-González E, Motger-Albertí A, Ramió-Torrentà L, Garre-Olmo J, Pérez-Brocal V, et al. Gut microbiota links to serum ferritin and cognition. Gut Microbes 2023;15. [CrossRef]

- Bogdan AR, Miyazawa M, Hashimoto K, Tsuji Y. Regulators of Iron Homeostasis: New Players in Metabolism, Cell Death, and Disease. Trends Biochem Sci 2016;41:274–86. [CrossRef]

- Galaris D, Barbouti A, Pantopoulos K. Iron homeostasis and oxidative stress: An intimate relationship. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 2019;1866. [CrossRef]

- Pretorius L, Kell DB, Pretorius E. Iron dysregulation and dormant microbes as causative agents for impaired blood rheology and pathological clotting in Alzheimer’s type dementia. Front Neurosci 2018;12. [CrossRef]

- Wang F, Wang J, Shen Y, Li H, Rausch WD, Huang X. Iron Dyshomeostasis and Ferroptosis: A New Alzheimer’s Disease Hypothesis? Front Aging Neurosci 2022;14. [CrossRef]

- Yan N, Zhang J. Iron Metabolism, Ferroptosis, and the Links With Alzheimer’s Disease. n.d.

- Apple CG, Miller ES, Kannan KB, Thompson C, Darden DB, Efron PA, et al. Prolonged Chronic Stress and Persistent Iron Dysregulation Prevent Anemia Recovery Following Trauma. Journal of Surgical Research 2021;267:320–7. [CrossRef]

- Reid BM, Georgieff MK. The Interaction between Psychological Stress and Iron Status on Early-Life Neurodevelopmental Outcomes. Nutrients 2023;15. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Hu R, Li M, Li F, Meng H, Zhu G, et al. Deferoxamine attenuates iron-induced long-term neurotoxicity in rats with traumatic brain injury. Neurological Sciences 2013;34:639–45. [CrossRef]

- Charlebois E, Pantopoulos K. Nutritional Aspects of Iron in Health and Disease. Nutrients 2023;15. [CrossRef]

- Zeidan RS, Martenson M, Tamargo JA, McLaren C, Ezzati A, Lin Y, et al. Iron homeostasis in older adults: balancing nutritional requirements and health risks. Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging 2024;28. [CrossRef]

- Loveikyte R, Bourgonje AR, van Goor H, Dijkstra G, van der Meulen—de Jong AE. The effect of iron therapy on oxidative stress and intestinal microbiota in inflammatory bowel diseases: A review on the conundrum. Redox Biol 2023;68. [CrossRef]

- Haines DD, Tosaki A. Heme degradation in pathophysiology of and countermeasures to inflammation-associated disease. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21:1–25. [CrossRef]

- Mendoza E, Duque X, Moran S, Martínez-Andrade G, Reyes-Maldonado E, Flores-Huerta S, et al. Hepcidin and other indicators of iron status, by alpha-1 acid glycoprotein levels, in a cohort of Mexican infants Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved n.d. [CrossRef]

- Malesza IJ, Bartkowiak-Wieczorek J, Winkler-Galicki J, Nowicka A, Dzięciołowska D, Błaszczyk M, et al. The Dark Side of Iron: The Relationship between Iron, Inflammation and Gut Microbiota in Selected Diseases Associated with Iron Deficiency Anaemia—A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2022;14. [CrossRef]

- Gleason A, Bush AI. Iron and Ferroptosis as Therapeutic Targets in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurotherapeutics 2021;18:252–64. [CrossRef]

- Logroscino G, Gao X, Chen H, Wing A, Ascherio A. Dietary iron intake and risk of Parkinson’s disease. Am J Epidemiol 2008;168:1381–8. [CrossRef]

- Kernan KF, Carcillo JA. Hyperferritinemia and inflammation. Int Immunol 2017;29:401–9. [CrossRef]

- Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, et al. Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 2012;149:1060–72. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Cao F, Yin H liang, Huang Z jian, Lin Z tao, Mao N, et al. Ferroptosis: past, present and future. Cell Death Dis 2020;11. [CrossRef]

- Sfera A, Bullock K, Price A, Inderias L, Osorio C. Ferrosenescence: The iron age of neurodegeneration? Mech Ageing Dev 2018;174:63–75. [CrossRef]

- Ma H, Dong Y, Chu Y, Guo Y, Li L. The mechanisms of ferroptosis and its role in alzheimer’s disease. Front Mol Biosci 2022;9. [CrossRef]

- Stockwell BR, Friedmann Angeli JP, Bayir H, Bush AI, Conrad M, Dixon SJ, et al. Ferroptosis: A Regulated Cell Death Nexus Linking Metabolism, Redox Biology, and Disease. Cell 2017;171:273–85. [CrossRef]

- Smith M. Increased Iron and Free Radical Generation in Preclinical Alzheimer Disease and Mild Cogni 2010.

- Ayton S, Faux NG, Bush AI, Weiner MW, Aisen P, Petersen R, et al. Ferritin levels in the cerebrospinal fluid predict Alzheimer’s disease outcomes and are regulated by APOE. Nat Commun 2015;6. [CrossRef]

- Seyoum Y, Baye K, Humblot C. Iron homeostasis in host and gut bacteria–a complex interrelationship. Gut Microbes 2021;13:1–19. [CrossRef]

- Ashraf A, Jeandriens J, Parkes HG, So PW. Iron dyshomeostasis, lipid peroxidation and perturbed expression of cystine/glutamate antiporter in Alzheimer’s disease: Evidence of ferroptosis. Redox Biol 2020;32. [CrossRef]

- Goedert M. Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases: The prion concept in relation to assembled Aβ, tau, and α-synuclein. Science (1979) 2015;349. [CrossRef]

- The prion-like propagation hypothesis in Alzheimerʼs and Parkinsonʼs disease. Current Opin n.d.

- Formanowicz D, Radom M, Rybarczyk A, Formanowicz P. The role of Fenton reaction in ROS-induced toxicity underlying atherosclerosis—modeled and analyzed using a Petri net-based approach. BioSystems 2018;165:71–87. [CrossRef]

- Krewulak KD, Vogel HJ. Structural biology of bacterial iron uptake. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 2008;1778:1781–804. [CrossRef]

- Schaible UE, Kaufmann SHE. Iron and microbial infection. Nat Rev Microbiol 2004;2:946–53. [CrossRef]

- Lyte M, Cryan JF. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology 817 Microbial Endocrinology Microbial Endocrinology: The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in Health and Disease. n.d.

- Marchesi JR, Ravel J. The vocabulary of microbiome research: a proposal. Microbiome 2015;3. [CrossRef]

- Berg G, Rybakova D, Fischer D, Cernava T, Vergès MCC, Charles T, et al. Microbiome definition re-visited: old concepts and new challenges. Microbiome 2020;8. [CrossRef]

- Shanahan F, Ghosh TS, O’Toole PW. The Healthy Microbiome—What Is the Definition of a Healthy Gut Microbiome? Gastroenterology 2021;160:483–94. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee S, Lukiw WJ. Alzheimer’s disease and the microbiome. Front Cell Neurosci 2013. [CrossRef]

- Vogt NM, Kerby RL, Dill-McFarland KA, Harding SJ, Merluzzi AP, Johnson SC, et al. Gut microbiome alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep 2017;7. [CrossRef]

- Rawls M, Ellis AK. The microbiome of the nose. Annals of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology 2019;122:17–24. [CrossRef]

- Strandwitz P, Kim KH, Terekhova D, Liu JK, Sharma A, Levering J, et al. GABA-modulating bacteria of the human gut microbiota. Nat Microbiol 2019;4:396–403. [CrossRef]

- Stasi C, Sadalla S, Milani S. The Relationship Between the Serotonin Metabolism, Gut-Microbiota and the Gut-Brain Axis. Curr Drug Metab 2019;20:646–55. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Tong Q, Ma SR, Zhao ZX, Pan L Bin, Cong L, et al. Oral berberine improves brain dopa/dopamine levels to ameliorate Parkinson’s disease by regulating gut microbiota. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2021;6. [CrossRef]

- Braga JD, Thongngam M, Kumrungsee T. Gamma-aminobutyric acid as a potential postbiotic mediator in the gut–brain axis. NPJ Sci Food 2024;8. [CrossRef]

- Loh JS, Mak WQ, Tan LKS, Ng CX, Chan HH, Yeow SH, et al. Microbiota–gut–brain axis and its therapeutic applications in neurodegenerative diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024;9. [CrossRef]

- Abdel Haq R, Schlachetzki JCM, Glass CK, Mazmanian SK. Microbiome–microglia connections via the gut–brain axis. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2019;216:41–59. [CrossRef]

- Chandra S, Di Meco A, Dodiya HB, Popovic J, Cuddy LK, Weigle IQ, et al. The gut microbiome regulates astrocyte reaction to Aβ amyloidosis through microglial dependent and independent mechanisms. Mol Neurodegener 2023;18. [CrossRef]

- Arabi TZ, Alabdulqader AA, Sabbah BN, Ouban A. Brain-inhabiting bacteria and neurodegenerative diseases: the “brain microbiome” theory. Front Aging Neurosci 2023;15. [CrossRef]

- Mossad O, Erny D. The microbiota–microglia axis in central nervous system disorders. Brain Pathology 2020;30:1159–77. [CrossRef]

- Lynch CMK, Cowan CSM, Bastiaanssen TFS, Moloney GM, Theune N, van de Wouw M, et al. Critical windows of early-life microbiota disruption on behaviour, neuroimmune function, and neurodevelopment. Brain Behav Immun 2023;108:309–27. [CrossRef]

- Arnoriaga-Rodríguez M, Mayneris-Perxachs J, Burokas A, Contreras-Rodríguez O, Blasco G, Coll C, et al. Obesity Impairs Short-Term and Working Memory through Gut Microbial Metabolism of Aromatic Amino Acids. Cell Metab 2020;32:548-560.e7. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Xu Z, Guo J, Xiong Z, Hu B. Exploring the gut microbiome-Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction connection: Mechanisms, clinical implications, and future directions. Brain Behav Immun Health 2024;38. [CrossRef]

- Martin CR, Osadchiy V, Kalani A, Mayer EA. The Brain-Gut-Microbiome Axis. CMGH 2018;6:133–48. [CrossRef]

- Clemmensen C, Müller TD, Woods SC, Berthoud HR, Seeley RJ, Tschöp MH. Gut-Brain Cross-Talk in Metabolic Control. Cell 2017;168:758–74. [CrossRef]

- Kesika P, Suganthy N, Sivamaruthi BS, Chaiyasut C. Role of gut-brain axis, gut microbial composition, and probiotic intervention in Alzheimer’s disease. Life Sci 2021;264. [CrossRef]

- Saitoh O SKMR et al. The forms and the levels of fecal PMN-elastase in patients with colorectal diseases. American Journal of Gastroenterology 1995;103:162–9. [CrossRef]

- Gagnière J, Raisch J, Veziant J, Barnich N, Bonnet R, Buc E, et al. Gut microbiota imbalance and colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2016;22:501–18. [CrossRef]

- Ng O. Iron, microbiota and colorectal cancer. Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift 2016;166:431–6. [CrossRef]

- Buhnik-Rosenblau K, Moshe-Belizowski S, Danin-Poleg Y, Meyron-Holtz EG. Genetic modification of iron metabolism in mice affects the gut microbiota. BioMetals 2012;25:883–92. [CrossRef]

- Andrews SC, Robinson AK, Rodríguez-Quiñones F. Bacterial iron homeostasis. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2003;27:215–37. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Conesa D, López G, Ros G. Effect of probiotic, prebiotic and synbiotic follow-up infant formulas on iron bioavailability in rats. Food Science and Technology International 2007;13:69–77. [CrossRef]

- Cornelis P, Wei Q, Andrews SC, Vinckx T. Iron homeostasis and management of oxidative stress response in bacteria. Metallomics 2011;3:540–9. [CrossRef]

- Timofeeva AM, Galyamova MR, Sedykh SE. Bacterial Siderophores: Classification, Biosynthesis, Perspectives of Use in Agriculture. Plants 2022;11. [CrossRef]

- Timofeeva AM, Galyamova MR, Sedykh SE. Bacterial Siderophores: Classification, Biosynthesis, Perspectives of Use in Agriculture. Plants 2022;11. [CrossRef]

- Řezanka T, Palyzová A, Faltýsková H, Sigler K. Siderophores: Amazing Metabolites of Microorganisms. Studies in Natural Products Chemistry, vol. 60, Elsevier B.V.; 2018, p. 157–88. [CrossRef]

- Lau CKY, Krewulak KD, Vogel HJ. Bacterial ferrous iron transport: The Feo system. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2016;40:273–98. [CrossRef]

- Seyoum Y, Baye K, Humblot C. Iron homeostasis in host and gut bacteria–a complex interrelationship. Gut Microbes 2021;13:1–19. [CrossRef]

- Çelen E, Kiliç A, Moore GR. The role of Escherichia coli bacterroferrrttn n stress nduced conddttons. vol. 74. 2015.

- Sender R, Fuchs S, Milo R. Are We Really Vastly Outnumbered? Revisiting the Ratio of Bacterial to Host Cells in Humans. Cell 2016;164:337–40. [CrossRef]

- Das B, Ghosh TS, Kedia S, Rampal R, Saxena S, Bag S, et al. Analysis of the gut microbiome of rural and urban healthy indians living in sea level and high altitude areas. Sci Rep 2018;8. [CrossRef]

- Kitamura K, Sasaki M, Matsumoto M, Shionoya H, Iida K. Protective effect of Bacteroides fragilis LPS on Escherichia coli LPS-induced inflammatory changes in human monocytic cells and in a rheumatoid arthritis mouse model. Immunol Lett 2021;233:48–56. [CrossRef]

- Chang C, Lin H. Dysbiosis in gastrointestinal disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2016;30:3–15. [CrossRef]

- Angelucci F, Cechova K, Amlerova J, Hort J. Antibiotics, gut microbiota, and Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroinflammation 2019;16:108. [CrossRef]

- Wang B, Yao M, Lv L, Ling Z, Li L. The Human Microbiota in Health and Disease. Engineering 2017;3:71–82. [CrossRef]

- Sochocka M, Donskow-Łysoniewska K, Diniz BS, Kurpas D, Brzozowska E, Leszek J. The Gut Microbiome Alterations and Inflammation-Driven Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease—a Critical Review. Mol Neurobiol 2019;56:1841–51. [CrossRef]

- Pluta R, Ułamek-Kozioł M, Januszewski S, Czuczwar SJ. Gut microbiota and pro/prebiotics in Alzheimer’s disease. Aging 2020;12:5539–50. [CrossRef]

- Kim H soo, Kim S, Shin SJ, Park YH, Nam Y, Kim C won, et al. Gram-negative bacteria and their lipopolysaccharides in Alzheimer’s disease: pathologic roles and therapeutic implications. Transl Neurodegener 2021;10. [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Albornoz MC, García-Guáqueta DP, Velez-Van-meerbeke A, Talero-Gutiérrez C. Maternal nutrition and neurodevelopment: A scoping review. Nutrients 2021;13. [CrossRef]

- Baltrusch S. The Role of Neurotropic B Vitamins in Nerve Regeneration. Biomed Res Int 2021;2021. [CrossRef]

- Lauer AA, Grimm HS, Apel B, Golobrodska N, Kruse L, Ratanski E, et al. Mechanistic Link between Vitamin B12 and Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomolecules 2022;12. [CrossRef]

- Popescu A, German M. Vitamin K2 holds promise for Alzheimer’s prevention and treatment. Nutrients 2021;13. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Wang X, Li H, Ni C, Du Z, Yan F. Human oral microbiota and its modulation for oral health. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy 2018;99:883–93. [CrossRef]

- DIbello V, Lozupone M, Manfredini D, DIbello A, Zupo R, Sardone R, et al. Oral frailty and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Neural Regen Res 2021;16:2149–53. [CrossRef]

- Sureda A, Daglia M, Argüelles Castilla S, Sanadgol N, Fazel Nabavi S, Khan H, et al. Oral microbiota and Alzheimer’s disease: Do all roads lead to Rome? Pharmacol Res 2020;151. [CrossRef]

- Bello-Corral L, Alves-Gomes L, Fernández-Fernández JA, Fernández-García D, Casado-Verdejo I, Sánchez-Valdeón L. Implications of gut and oral microbiota in neuroinflammatory responses in Alzheimer’s disease. Life Sci 2023;333. [CrossRef]

- Narengaowa, Kong W, Lan F, Awan UF, Qing H, Ni J. The Oral-Gut-Brain AXIS: The Influence of Microbes in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Cell Neurosci 2021;15. [CrossRef]

- Orr ME, Reveles KR, Yeh CK, Young EH, Han X. Can oral health and oral-derived biospecimens predict progression of dementia? Oral Dis 2020;26:249–58. [CrossRef]

- Dioguardi M, Crincoli V, Laino L, Alovisi M, Sovereto D, Mastrangelo F, et al. The role of periodontitis and periodontal bacteria in the onset and progression of alzheimerʹs disease: A systematic review. J Clin Med 2020;9. [CrossRef]

- Bui FQ, Almeida-da-Silva CLC, Huynh B, Trinh A, Liu J, Woodward J, et al. Association between periodontal pathogens and systemic disease. Biomed J 2019;42:27–35. [CrossRef]

- Sedghi LM, Bacino M, Kapila YL. Periodontal Disease: The Good, The Bad, and The Unknown. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2021;11. [CrossRef]

- Mysak J, Podzimek S, Duskova J. Porphyromonas gingivalis: Major Periodontopathic Pathogen Overview. 2014.

- Franciotti R, Pignatelli P, Carrarini C, Romei FM, Mastrippolito M, Gentile A, et al. Exploring the connection between porphyromonas gingivalis and neurodegenerative diseases: A pilot quantitative study on the bacterium abundance in oral cavity and the amount of antibodies in serum. Biomolecules 2021;11. [CrossRef]

- Chen CK, Wu YT, Chang YC. Association between chronic periodontitis and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease: A retrospective, population-based, matched-cohort study. Alzheimers Res Ther 2017;9. [CrossRef]

- Kim SR, Son M, Kim YR, Kang HK. Risk of dementia according to the severity of chronic periodontitis in Korea: a nationwide retrospective cohort study. Epidemiol Health 2022;44. [CrossRef]

- Ryder MI. Porphyromonas gingivalis and Alzheimer disease: Recent findings and potential therapies. J Periodontol 2020;91:S45–9. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z, Liu D, Pan Y. The Role of Porphyromonas gingivalis Outer Membrane Vesicles in Periodontal Disease and Related Systemic Diseases. n.d.

- Narengaowa, Kong W, Lan F, Awan UF, Qing H, Ni J. The Oral-Gut-Brain AXIS: The Influence of Microbes in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Cell Neurosci 2021;15. [CrossRef]

- Sansores-España LD, Melgar-Rodríguez S, Olivares-Sagredo K, Cafferata EA, Martínez-Aguilar VM, Vernal R, et al. Oral-Gut-Brain Axis in Experimental Models of Periodontitis: Associating Gut Dysbiosis With Neurodegenerative Diseases. Frontiers in Aging 2021;2. [CrossRef]

- Verma A, Azhar G, Zhang X, Patyal P, Kc G, Sharma S, et al. P. gingivalis-LPS Induces Mitochondrial Dysfunction Mediated by Neuroinflammation through Oxidative Stress. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24:950. [CrossRef]

- Dominy SS, Lynch C, Ermini F, Benedyk M, Marczyk A, Konradi A, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer’s disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. 2019.

- Cox LM, Weiner HL. Microbiota Signaling Pathways that Influence Neurologic Disease. Neurotherapeutics 2018;15:135–45. [CrossRef]

- Weber C, Dilthey A, Finzer P. The role of microbiome-host interactions in the development of Alzheimer’s disease. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2023;13. [CrossRef]

- Cook J, Prinz M. Regulation of microglial physiology by the microbiota. Gut Microbes 2022;14. [CrossRef]

- Cherny I, Rockah L, Levy-Nissenbaum O, Gophna U, Ron EZ, Gazit E. The formation of Escherichia coli curli amyloid fibrils is mediated by prion-like peptide repeats. J Mol Biol 2005;352:245–52. [CrossRef]

- Smith DR, Price JE, Burby PE, Blanco LP, Chamberlain J, Chapman MR. The production of curli amyloid fibers is deeply integrated into the biology of escherichia coli. Biomolecules 2017;7. [CrossRef]

- Das TK, Blasco-Conesa MP, Korf J, Honarpisheh P, Chapman MR, Ganesh BP. Bacterial Amyloid Curli Associated Gut Epithelial Neuroendocrine Activation Predominantly Observed in Alzheimer’s Disease Mice with Central Amyloid-β Pathology. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2022;88:191–205. [CrossRef]

- Dua P ZY. Microbial Sources of Amyloid and Relevance to Amyloidogenesis and AlzheimerÂ’s Disease (AD). J Alzheimers Dis Parkinsonism 2015;05. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y, Jaber V, Lukiw WJ. Secretory products of the human GI tract microbiome and their potential impact on Alzheimer’s disease (AD): Detection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in AD hippocampus. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2017;7. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Y, Smith D, Leong BJ, Brännström K, Almqvist F, Chapman MR. Promiscuous cross-seeding between bacterial amyloids promotes interspecies biofilms. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2012;287:35092–103. [CrossRef]

- R. Deane. RAGE mediates amyloid-β peptide transport across theblood-brain barrier and accumulation in brain 2003.

- Vargas-Caraveo A, Sayd A, Maus SR, Caso JR, Madrigal JLM, García-Bueno B, et al. Lipopolysaccharide enters the rat brain by a lipoprotein-mediated transport mechanism in physiological conditions. Sci Rep 2017;7. [CrossRef]

- Kim W-G, Mohney RP, Wilson B, Jeohn G-H, Liu B, Hong J-S. Regional Difference in Susceptibility to Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Neurotoxicity in the Rat Brain: Role of Microglia. 2000.

- Zhao Y, Cong L, Jaber V, Lukiw WJ. Microbiome-derived lipopolysaccharide enriched in the perinuclear region of Alzheimer’s disease brain. Front Immunol 2017;8. [CrossRef]

- Zhao J, Bi W, Xiao S, Lan X, Cheng X, Zhang J, et al. Neuroinflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide causes cognitive impairment in mice. Sci Rep 2019;9. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y, Jaber VR, Pogue AI, Sharfman NM, Taylor C, Lukiw WJ. Lipopolysaccharides (LPSs) as Potent Neurotoxic Glycolipids in Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). Int J Mol Sci 2022;23. [CrossRef]

- Kantarci A, Tognoni CM, Yaghmoor W, Marghalani A, Stephens D, Ahn JY, et al. Microglial response to experimental periodontitis in a murine model of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep 2020;10. [CrossRef]

- Fakhoury M. Microglia and astrocytes in Alzheimer’s disease: implications for therapy. Curr Neuropharmacol 2017;15. [CrossRef]

- di Penta A, Moreno B, Reix S, Fernandez-Diez B, Villanueva M, Errea O, et al. Oxidative Stress and Proinflammatory Cytokines Contribute to Demyelination and Axonal Damage in a Cerebellar Culture Model of Neuroinflammation. PLoS One 2013;8. [CrossRef]

- Zhou J, Windsor LJ. Porphyromonas gingivalis affects host collagen degradation by affecting expression, activation, and inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases. J Periodontal Res 2006;41:47–54. [CrossRef]

- Andrian E, Mostefaoui Y, Rouabhia M, Grenier D. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases by porphyromonas gingivalis in an engineered human oral mucosa model. J Cell Physiol 2007;211:56–62. [CrossRef]

- Wolf AJ, Underhill DM. Peptidoglycan recognition by the innate immune system. Nat Rev Immunol 2018;18:243–54. [CrossRef]

- Arentsen T, Qian Y, Gkotzis S, Femenia T, Wang T, Udekwu K, et al. The bacterial peptidoglycan-sensing molecule Pglyrp2 modulates brain development and behavior. Mol Psychiatry 2017;22:257–66. [CrossRef]

- Gabanyi I, Lepousez G, Wheeler R, Vieites-Prado A, Nissant A, Wagner S, et al. Bacterial sensing via neuronal Nod2 regulates appetite and body temperature n.d. [CrossRef]

- Halliwell B. Oxidative stress and neurodegeneration: Where are we now? J Neurochem 2006;97:1634–58. [CrossRef]

- Gupta SK, Vyavahare S, Duchesne Blanes IL, Berger F, Isales C, Fulzele S. Microbiota-derived tryptophan metabolism: Impacts on health, aging, and disease. Exp Gerontol 2023;183. [CrossRef]

- Maitre M, Klein C, Patte-Mensah C, Mensah-Nyagan AG. Tryptophan metabolites modify brain Aβ peptide degradation: A role in Alzheimer’s disease? Prog Neurobiol 2020;190. [CrossRef]

- Sun DS, Gao LF, Jin L, Wu H, Wang Q, Zhou Y, et al. Fluoxetine administration during adolescence attenuates cognitive and synaptic deficits in adult 3×TgAD mice. Neuropharmacology 2017;126:200–12. [CrossRef]

- John A. Hardy. Alzheimer’s Disease: The Amyloid Cascade Hypothesis | Science 1992.

- Takasugi N, Komai M, Kaneshiro N, Ikeda A, Kamikubo Y, Uehara T. The Pursuit of the “Inside” of the Amyloid Hypothesis—Is C99 a Promising Therapeutic Target for Alzheimer’s Disease? Cells 2023;12. [CrossRef]

- Rudge JDA. A New Hypothesis for Alzheimer’s Disease: The Lipid Invasion Model. J Alzheimers Dis Rep 2022;6:129–61. [CrossRef]

- Sperling RA, Rentz DM, Johnson KA, Karlawish J, Donohue M, Salmon DP, et al. The A4 study: Stopping AD before symptoms begin? Sci Transl Med 2014;6. [CrossRef]

- Javitt DC, Martinez A, Sehatpour P, Beloborodova A, Habeck C, Gazes Y, et al. Disruption of early visual processing in amyloid-positive healthy individuals and mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Res Ther 2023;15. [CrossRef]

- O’Connor A, Weston PSJ, Pavisic IM, Ryan NS, Collins JD, Lu K, et al. Quantitative detection and staging of presymptomatic cognitive decline in familial Alzheimer’s disease: A retrospective cohort analysis. Alzheimers Res Ther 2020;12. [CrossRef]

- Elliott P Vichinsky. Iron chelators: Choice of agent, dosing, and adverse effects. 2024.

- Schreiner OD, Schreiner TG. Iron chelators as a therapeutic option for Alzheimer’s disease—A mini-review. Frontiers in Aging 2023;4. [CrossRef]

- Nuñez MT, Chana-Cuevas P. New perspectives in iron chelation therapy for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Pharmaceuticals 2018;11. [CrossRef]

- Pereira FC, Ge X, Kristensen JM, Kirkegaard RH, Maritsch K, Szamosvári D, et al. The Parkinson’s disease drug entacapone disrupts gut microbiome homeostasis via iron sequestration. Nat Microbiol 2024;9:3165–83. [CrossRef]

- Naomi R, Embong H, Othman F, Ghazi HF, Maruthey N, Bahari H. Probiotics for alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review. Nutrients 2022;14. [CrossRef]

- Cheng Y, Liu J, Ling Z. Short-chain fatty acids-producing probiotics: A novel source of psychobiotics. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2022;62:7929–59. [CrossRef]

- Plaza-Diaz J, Ruiz-Ojeda FJ, Gil-Campos M, Gil A. Mechanisms of Action of Probiotics. Advances in Nutrition, vol. 10, Oxford University Press; 2019, p. S49–66. [CrossRef]

- Cristofori F, Dargenio VN, Dargenio C, Miniello VL, Barone M, Francavilla R. Anti-Inflammatory and Immunomodulatory Effects of Probiotics in Gut Inflammation: A Door to the Body. Front Immunol 2021;12. [CrossRef]

- Nagpal R, Wang S, Ahmadi S, Hayes J, Gagliano J, Subashchandrabose S, et al. Human-origin probiotic cocktail increases short-chain fatty acid production via modulation of mice and human gut microbiome. Sci Rep 2018;8. [CrossRef]

- Angelucci F, Cechova K, Amlerova J, Hort J. Antibiotics, gut microbiota, and Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroinflammation 2019;16. [CrossRef]

- Angelucci F, Cechova K, Amlerova J, Hort J. Antibiotics, gut microbiota, and Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroinflammation 2019;16. [CrossRef]

- Elangovan S, Borody TJ, Holsinger RMD. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Reduces Pathology and Improves Cognition in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Cells 2023;12. [CrossRef]

- Sun J, Xu J, Ling Y, Wang F, Gong T, Yang C, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation alleviated Alzheimer’s disease-like pathogenesis in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Transl Psychiatry 2019;9. [CrossRef]

- Nassar ST, Tasha T, Desai A, Bajgain A, Ali A, Dutta C, et al. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Role in the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2022. [CrossRef]

- Dominy SS, Lynch C, Ermini F, Benedyk M, Marczyk A, Konradi A, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer’s disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. Sci Adv 2019;5. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen S V., Nguyen MTH, Tran BC, Ho MTQ, Umeda K, Rahman S. Evaluation of lozenges containing egg yolk antibody against porphyromonas gingivalis gingipains as an adjunct to conventional non-surgical therapy in periodontitis patients: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J Periodontol 2018;89:1334–9. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).