1. Introduction

In today's world, with the increasing patient population, the demand for tailored and complex medications is increasing enormously. However, the limitations of traditional manufacturing platforms are limiting the capability of pharmaceutical industries. Oral formulations are much preferred among various dosage forms, attributing to low cost and easy administration [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Oral medications have colossal demand and generate good revenue for the pharmaceutical industry.

Knowing that “one dose fits all” is not true in all scenarios is essential. The pharmaceutical industries have researched and recommended the doses of the medications available in the market based on safety and efficacy, leaving no flexibility for the physicians to adjust the dose based on the severity of disease condition, age, sex, and race [

5,

6,

7]. Few patients might even require dosage forms with varied drug release profiles to overcome any side effects of high plasma drug concentrations. The majority of the geriatric patient population is required to administer several medications each day depending on their disease state, which might also be challenging for patients with dysphagia [

8,

9,

10]. Developing combination products might benefit the geriatric population to a certain extent. However, developing tailored medications to address the patient's needs by employing traditional manufacturing platforms such as direct blending, dry granulation, and wet granulation remains challenging [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

In 2015, the approval of Spritram medication by the United States Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) developed by the Zip dose additive manufacturing platform attracted the attention of researchers from various avenues of the pharmaceutical sectors [

16,

17,

18,

19]. Since then, much research has been conducted in academia and industries exploring the opportunities and applications of additive manufacturing techniques for developing tailored medications. Additive manufacturing involves fabricating a three-dimensional (3D) object by depositing the material layer by layer until the desired object is printed [

14,

15,

20,

21]. The 3D-printing process is most widely employed in automobile industries for designing a prototype model. It is also utilized to manufacture various complex components that are difficult to manufacture using traditional approaches [

16,

17,

22,

23,

24]. Additive manufacturing provides advantages such as on-demand manufacturing of precision medicine, dose adjustment, fabrication of polypills, and extemporaneous clinical supplies. Even pediatric medications can be fabricated for different shapes and flavors to attract children and make them adhere to the prescription medications [

25,

26,

27,

28].

To date, the various 3D printing techniques investigated for developing pharmaceutical dosage forms are classified as inkjet printing (IP), stereolithography (SLA), binder deposition, powder fusion, and nozzle-based printing techniques. The process of inkjet printing is suitable for solutions and drug suspensions. It utilizes low temperature and low pressure. The liquid material is sprayed on the build platform through a nozzle in the printer head. The deposited material requires time to cure between the printing of successive layers [

27,

28,

29]. As the process is suitable for low-temperature additive manufacturing, the faster curing of deposited material might require infrared or ultraviolet light. The resolution of printlets developed by the IP process depends on the printer nozzle size. The SLA type of additive manufacturing involves polymerization and solidification of resin material. Similar to the IP process, the SLA technique involves layer-by-layer printing of material until the desired object is formed. The major disadvantage of the SLA type of 3D printing is the availability of a limited number of cross-linked polymers, which are generally considered safe (GRAS). Binder deposition type of 3D printing is a powder-based technique where a layer of liquid binder is sprayed between successive layers of powder particles. The binder deposition technique manufactures the first FDA-approved commercial 3D printed product, SPIRTAM. Another type of powder-based additive manufacturing technique is powder fusion. This approach involves the application of heat using a laser beam where powder particles are bound using a low melting point material [

29,

30,

31,

32]. Lastly, the other type of additive manufacturing is the nozzle-based technique. It can be further classified as fused deposition modeling (FDM) and pressure-assisted microsyringe (PAM). FDM and PAM are thermal manufacturing techniques where the material is melted and deposited on top of the build platform until the object of desired geometry is fabricated. This review article mainly focuses on the critical material and process attributes essential in developing a robust dosage form utilizing nozzle-based additive manufacturing techniques, i.e., FDM and PAM. In addition, the suitability of nozzle-based additive manufacturing for establishing a continuous manufacturing line pairing with the hot melt extrusion process is also discussed, along with their advantages and limitations.

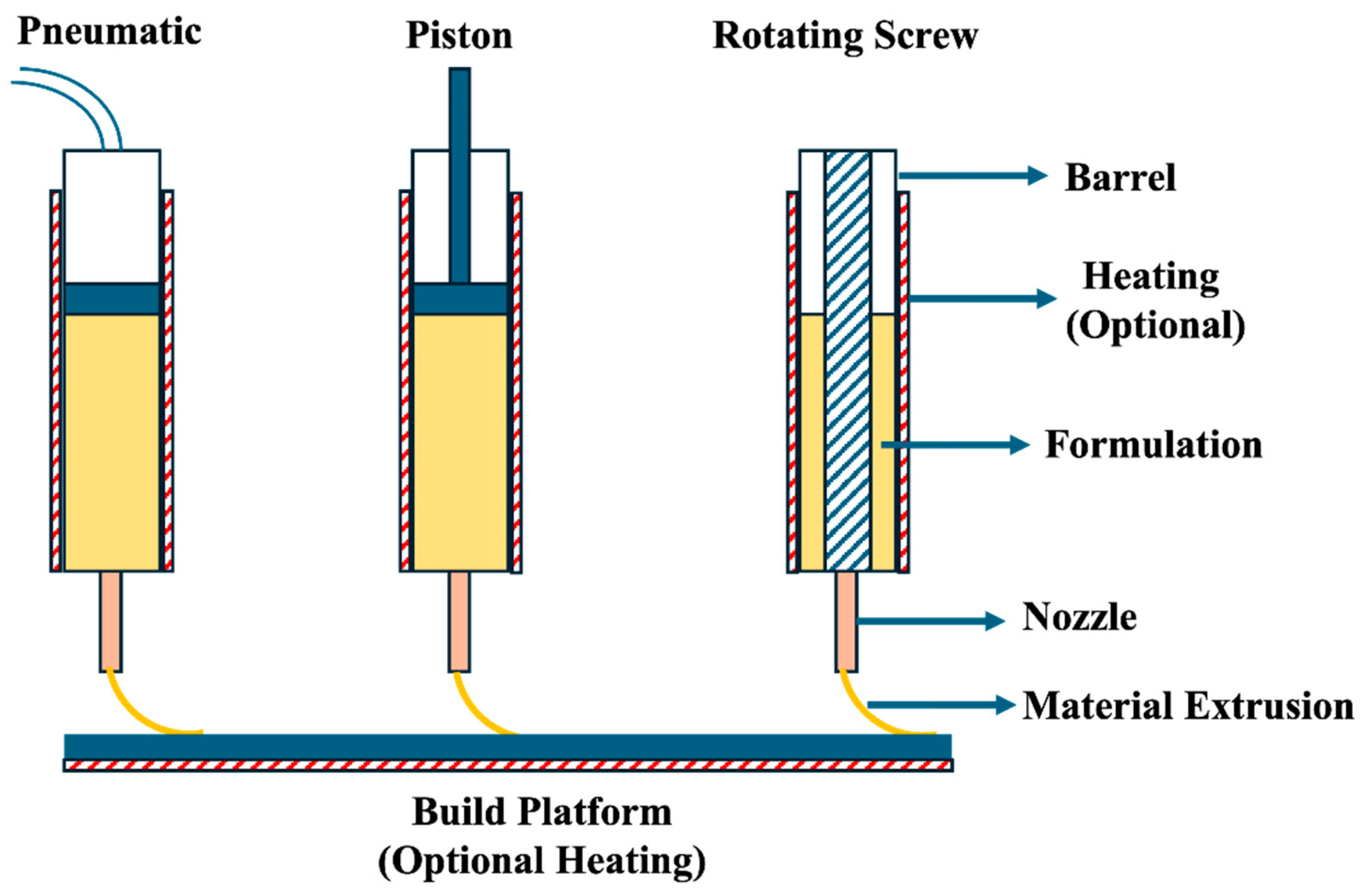

2. Pressure-Assisted Microsyringe (PAM)

PAM, called semi-solid extrusion (SSE), is a computer-controlled extrusion process. The instrumentation resembles a “syringe and piston” assembly, as shown in

Figure 1. The formulation materials loaded into the cylindrical body get extruded and deposited onto the build platform layer by layer until the object is fabricated completely [

33,

34]. The piston inside the barrel will be guided by pneumatic or mechanical force. The other type of mechanism is a rotating screw which conveys the material towards the nozzle, and the accumulation of material generates the force and extrudes the material from the nozzle. The barrel has the flexibility of heating or can be maintained ambient, making it suitable for processing powder and semi-solid materials. The curing time for the 3D printed mass depends on the type of material loaded into the barrel. The powder material loaded into the barrel gets melted by applying thermal energy. For such a process, the product's curing happens readily compared to the processing of semi-solid solvent material. The critical process parameters associated with this process include barrel temperature, build platform temperature, printing speed, and piston pressure [

35,

36]. Various critical material attributes, critical process, and instrument parameters that play a key role in the successful fabrication of medications are further discussed in detail.

2.1. Critical Material Properties

2.1.1. Thermal Properties

The process of PAM or SSE involves the application of thermal energy. Thus, the thermal properties of the processing materials play an essential role in successfully printing the dosage forms. The thermal properties of the processing materials, such as melting temperature, glass transition, and degradation temperature, need to be studied carefully. Considering the residence time of the material inside the heated barrel, the thermal process is unsuitable for heat-sensitive materials but can still be processed by preparing a semi-solid paste using appropriate solvents. The solvent-mediated process can also be employed for materials with low degradation temperatures. For the processing of formulations consisting of drug and polymer, while screening the materials, the glass transition temperature and melting point of the polymer must be considered, which might require high processing temperatures [

37,

38]. The addition of solid plasticizers such as polyethylene glycol (PEG) and stearic acid needs to be studied for processing at low temperatures. The processing temperature should be above the glass transition temperature of the processing material to avoid any clogging of materials in the nozzle and to avoid applying high extrusion pressure. It should stay below the degradation temperature of the materials. Below the glass transition temperature, the material exhibits a rigid and brittle nature, which is challenging to print. Above the glass transition temperature, the material becomes easily flowable, but its effect on the deformation of the structure needs to be monitored. Maintaining the printing temperature close to the glass transition temperature aids faster cooling, retaining the structural integrity. One another aspect that needs to be studied is thermal expansion. Few of the thermally expanded materials will shrink upon cooling, losing the bonding between the layers and affecting the mechanical integrity and quality of the dosage form [

39]. The processing temperature needs to be optimized by considering the drug's desired physical state (amorphous or crystalline) within the dosage form.

2.1.2. Rheological Properties

The viscosity of the processing material and the flow of material from the nozzle onto the build platform play an essential role in successfully fabricating 3D-printed medicine. Thus, it is very important to understand the rheological properties of the formulation components. An optimum viscosity of the material inside the barrel needs to be maintained. Highly viscous materials are challenging and require high process temperatures and extrusion force. Processing high viscous materials requires longer printing time than low viscous materials [

40,

41]. The materials exhibit thixotropic behavior where the viscosity decreases with increasing temperature, but it would be crucial to process the material with a low degradation temperature. For semisolid materials, the viscosity can be reduced by increasing the amount of solvent. However, the complete evaporation of the solvent needs to be ensured during the curing process to avoid toxicity to the patient population. In addition, the viscosity of the material extruding from the nozzle also needs to be studied. The high viscosity of the extruded material might affect the bonding between the successive layers, and the extrusion of low viscous materials might result in the deformation of the shape due to the pressure exerted by the layers deposited above. The material extrusion rate from the nozzle also needs to be controlled since faster extrusion also results in the deformation of shape, and a slower extrusion rate will result in the drying of material before reaching the build platform, affecting the product quality [

27]. An optimum yield stress of the material inside the barrel will prevent any premature flow of material and will maintain consistent flow under pressure. An optimum yield stress will also ensure the structural integrity of the 3D design without undergoing any deformation under pressure. Most of the material will exhibit shear-thinning behavior, where the viscosity decreases with increasing pressure, which is beneficial for the PAM process. Thus, processing temperature and pressure are essential in maintaining the optimum rheological properties for successful fabrication.

2.1.3. Miscibility

The miscibility of formulation components alone and in the presence of a drug needs to be studied. Immiscible components are unsuitable for developing robust dosage forms and need to be avoided. Miscible formulation composition ensures homogeneous distribution of drug and polymers in the dosage form. Immiscible systems will affect the drug release profiles and eventually affect the oral bioavailability of the drug. For the solvent-aided process, solvent compatibility with the formulation materials needs to be evaluated [

42,

43]. Immiscible composition results in a non-homogeneous mixture and will result in non-uniform extrusion of material from the printer, affecting the quality, performance, and mechanical properties of the 3D-printed medication. In fact, immiscibility would result in a non-homogeneous distribution of polymer in the case of modified medications, affecting the dosage form's release profiles. A thorough pre-formulation study must be conducted to screen the drug, excipients, and suitable solvent system. Various characterization tools such as differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) can be employed for screening the miscibility of formulation components. Thus, miscibility is a critical factor influencing homogeneity, printability, mechanical properties, drug release profiles, and dosage form stability.

2.1.4. Density of Material

The density of the materials plays an important role in the segregation and non-homogeneous extrusion of material from the nozzle, affecting the quality of the dosage form. In the solvent-aided process, the particle size distribution of any undissolved materials needs to be monitored, which might result in clogging of the nozzle, eventually interrupting the printing process. Screening materials with similar particle size distribution and density will result in better product design and development. In other aspects, the printing of high-density materials requires the application of high pressure, and low-density materials will flow easily from the printer nozzle, which also influences the geometry of the 3D design [

44]. Processing of high-density materials will result in high resolution of the dosage form, attributing to high melt viscosity and poor material spreading. Formulations composed of low-dense materials will produce high porosity, affecting the mechanical properties and drug release profiles. In contrast, high-dense materials will result in less porous objects, delaying drug release [

45]. Thu,s depending on the type of dosage form (immediate or modified release) being developed, the materials can be screened based on the density.

2.2. Critical Instrument Parameters

2.2.1. Type of Piston

The instrumentation of PAM can accommodate different types of pistons, such as screw-driven pistons, pneumatic pistons, and hydraulic pistons. The screw-driven piston moves in rotational and linear motion, conveying the material toward the nozzle. The conveying material builds the pressure at the nozzle and extrudes the material, and gets deposited on the build platform. By employing a screw type of piston, the entrapped air in the material can be removed, and also, the rotational motion helps in maintaining homogeneity. The screw speed dictates the flow rate of the material from the nozzle [

46]. However, the screw-driven piston is not suitable for processing of high viscous materials. In the case of pneumatic pistons, compressed air is applied onto the piston to push the material from the nozzle. Compared with the screw-driven process, the pneumatic piston is more straightforward and can be operated at high speed. The pneumatic piston is also capable of extruding highly viscous materials. However, the process is noisy, and maintaining a consistent air pressure is challenging, impacting the flow rate and quality of the medication. The other type of piston most commonly employed in the PAM process is the hydraulic piston, which utilizes pressurized liquids. Similar to the pneumatic process, this process is also suitable for processing highly viscous liquids, and the pressure can be maintained consistently without affecting the flow rate of material from the nozzle [

26]. It requires frequent maintenance to prevent leakage of pressurized liquids, which makes the process expensive. Thus, each piston type is significant for processing the materials. A suitable piston needs to be selected depending on the material properties.

2.2.2. Nozzle size

Nozzle size is another essential instrument component that plays a crucial role in successfully fabricating medications using the PAM additive manufacturing process. The nozzle size determines the resolution and quality of the printed dosage form. Smaller nozzle size results in a high-resolution printlet and increased printing time. It is also suitable for low-viscous materials. The printed dosage form's surface appears smoother with a smaller nozzle. Printing highly viscous materials requires high pressure, and employing larger nozzles will be beneficial. Employing larger nozzles will reduce the printing time, but the resolution will be compromised, resulting in a rough surface. Larger nozzles require less pressure for extruding the material and are suitable for highly viscous materials [

47,

48]. The size of the nozzle determines the layer thickness. In case of any formulations with undissolved particles, employing larger nozzles will be beneficial for successfully printing the dosage forms. A wide range of nozzles ranging from 100 - 1000 microns in size are available. However, nozzle sizes ranging from 150 - 500 microns are most commonly utilized for pharmaceutical manufacturing. Thus, depending on the rheological properties of the formulations and the acceptability of dosage form resolution, the printer nozzle's size must be selected.

2.2.3. Cooling Fan

Within the instrumentation of PAM, the cooling fan is another component that needs to be considered as a critical aspect for the successful development of quality 3D printed products. The cooling fan controls the temperature of the printing material and the printing environment. High cooling fan speed is advantageous to prevent material overheating upon prolonged runs. At the same time, the cooling rate needs to be optimized to avoid rapid drying of material, which might affect bonding between the layers [

49]. The location of the fan also plays an important role in cooling the printed object. Uniform cooling of the object should be achieved, but non-uniform cooling will affect the structural integrity and quality of the dosage form. A high cooling rate benefits low viscous materials where rapid cooling will prevent structural deformation. In the case of amorphous dispersions, a rapid cooling rate will aid the stability of the dosage forms. Thus, the cooling fan speed must be adjusted and optimized to print the medications successfully.

2.2.4. Build Platform

The build platform is essential and is a backbone for successfully printing the dosage form. The initial layer of the material extruded from the nozzle deposits and adheres to the build platform. Thus, the build platform supports the object being printed throughout the process. The build platform material needs to be compatible with the formulation components. Different build platform materials include glass, polyetherimide, polypropylene, polyethylene terephthalate, silicone, and polytetrafluoroethylene [

27,

39]. Towards the end of the printing process, the object needs to be ejected quickly without damaging the surface.

2.3. Critical Process Parameters

2.3.1. Barrel and Nozzle Temperature

The process of PAM can be carried out at ambient conditions and by applying thermal energy depending on the physical state of the material being processed. In the solvent-aided process, where the material's physical state is semi-solid, extrusion and printing can be carried out in ambient conditions by applying piston pressure. The processing of semisolid material has to be carried faster to avoid evaporation of solvents, which might result in increased viscosity of the processing material. Thermal energy might be needed to prevent nozzle blockage. However, the material's thermal stability inside the barrel must be considered before applying heat. In the case of processing the powder material, the barrel needs to be heated to a temperature more significant than the glass transition point of the processing material or greater than the melting point of the drug substance, depending on the intended physical state of the drug within the dosage form (amorphous or crystalline) [

38,

42]. To prevent blockage of the nozzle and to maintain a consistent flow of the material, the nozzle has to be heated, and the temperature needs to be maintained consistently throughout the process. In the case of employing different barrel and nozzle temperatures, it should be ensured that no heat conduction occurs in either direction. The entire barrel has to be heated uniformly to prevent any variations in the melt viscosity, which might influence the flow and the quality of the dosage form. The temperature needs to be maintained entirely below the degradation point of the materials. Processing the powdered form of thermolabile materials remains to be challenging [

34,

36]. Processing powdered materials requires longer heating time within the barrel to melt the formulation components. Thus, barrel and nozzle temperatures are essential in successfully fabricating medications.

2.3.2. Printing Speed

Printing speed is a critical process parameter that determines the quality and mechanical integrity of the printed object. Printing speed, viscosity of processing material, and extrusion rate are interrelated and influence the quality, structural integrity, and successful printing of the medications. Low printing speed requires a longer time to fabricate the medicines. At slow speed, the deposited layers get dried up quickly and affect the bonding of newly deposited layers. Low printing speed might benefit low viscous materials, providing enough residence time for the layers to get dried up and preventing the structure from deformation. Low printing speed will result in a smooth surface of the extruding material from the nozzle, resulting in high-resolution medications. The piston pressure must be adjusted to match the extrusion rate with the printing speed at low printing speed. Faster extrusion of material at low speed will result in over-deposition of the material, affecting the product quality [

35,

50]. High printing speeds can be employed for highly viscous materials, which will not cause any deformation of the 3D-printed structure. High piston pressure must be applied at a high printing speed to increase the extrusion rate and match the deposition. Thus, printing speed plays a vital role in successfully printing the dosage form, and a balance must be maintained between the printing speed and piston pressure.

2.3.3. Piston Pressure

Depending on the physical state of the processing material and printing speed, the piston pressure needs to be applied and optimized. Processing of low viscous materials requires low piston pressure, which will maintain a consistent and uniform flow of material and result in the successful printing of the medications [

30,

33]. An optimal piston pressure needs to be applied for low viscous materials, and a low extrusion rate needs to be ensured, allowing sufficient time for the deposited layers to solidify and preventing deformation of the printed material. Each type of piston can withstand different levels of pressure. The piston type needs to be optimized based on the amount of pressure being applied. The piston pressure has to be maintained below the maximum resistance limit to avoid any damage resulting in the process interruption. The barrel temperature must be increased in a few situations to reduce the melt viscosity and execute the process at low piston pressures. In case of high printing speed, a high piston pressure needs to be applied to maintain the extrusion rate of material in line with the printing speed.

2.3.4. Build Platform Temperature

During the additive manufacturing process, the build platform serves as a backbone, providing support for printed medication. The build platform temperature plays an important role in successfully printing the dosage forms. The need to maintain the build platform temperature depends on the nature of the material being processed. Few materials will adhere to the heated build platform, resulting in unsuccessful printing. Thus, heating the build platform and the temperature needs to be optimized during the early stages of development. In a few instances, irrespective of adjusting the build platform temperature, the materials fail to adhere to the build platform, indicating an investigation of different construction materials for the build platform. Maintaining a heated build platform also aids in easily ejection of the printed medication, which deforms or affects the surface quality [

37]. An optimal temperature needs to be maintained for successful processing. High build platform temperatures will affect the viscosity of the initial later, thereby resulting in the loss of bonding between the platform and the printed medication. Similarly, a low platform temperature will result in poor bonding of the initial layer with the platform, resulting in unsuccessful printing of the dosage forms.

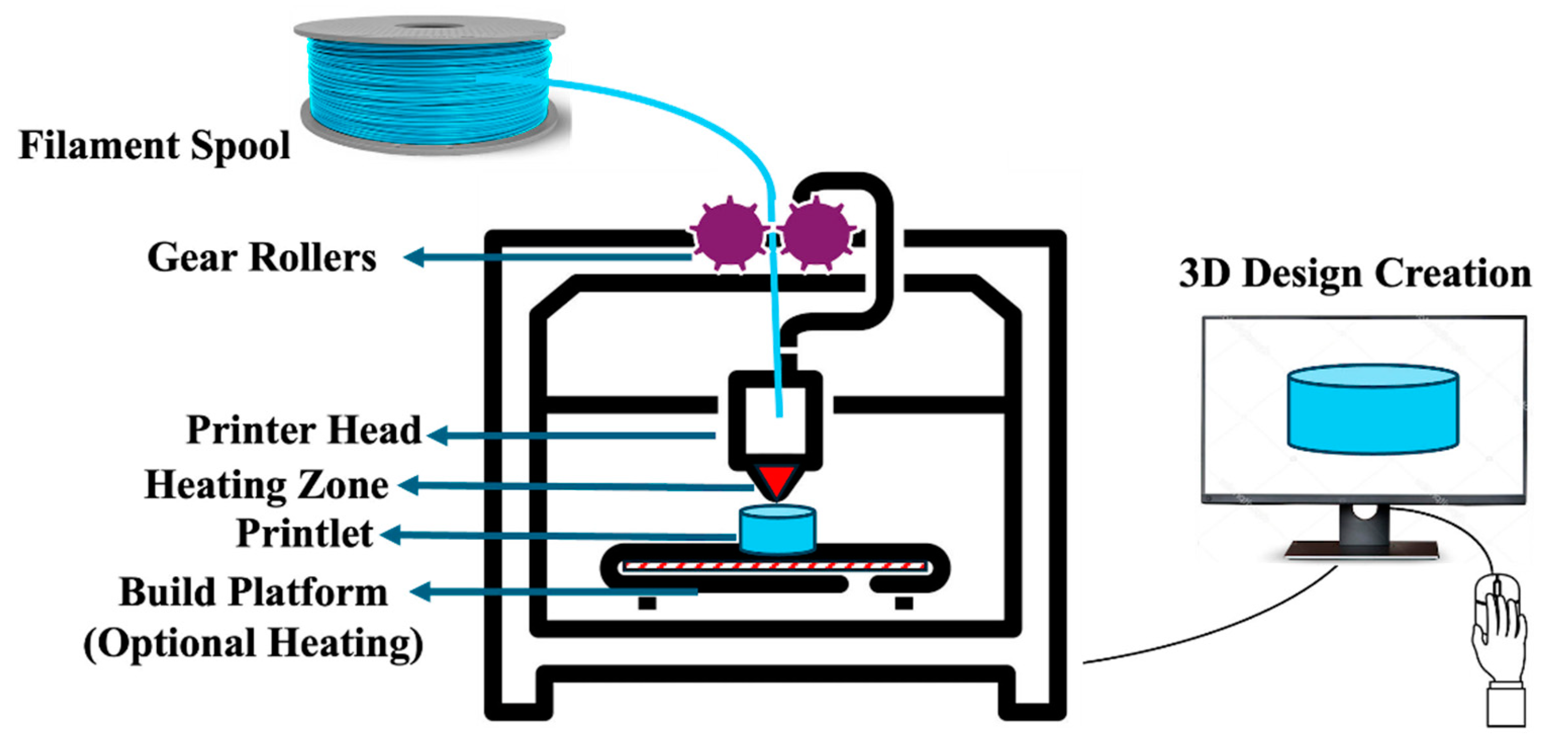

3. FDM 3D Printing

FDM 3D printing is a nozzle-based additive manufacturing technique that requires drug-loaded polymeric filament as “ink” for printing the medications. An FDM 3D printer typically consists of a gear roller, printer head, and build platform. FDM 3D printing begins with creating a 3D design, which is transferred as a .stl file into the printer software, which controls the printer. The software conveys the information to the printer as G-code layer by layer until the fabrication is completed. FDM 3D printing involves heating and softening polymeric filaments within the printer head and depositing them on top of the build platform until the object of the desired size and geometry is formed [

51,

52]. The gear roller conveys the polymeric filament into the printer head, which serves as a piston for extruding the molten mass through a heated nozzle onto the build platform. A schematic representation of an FDM 3D printer is shown in

Figure 2. Various process parameters involved in an FDM 3D printing process include printing speed, nozzle temperature, and build platform temperature.

The drug-loaded polymeric filaments required for FDM 3D printing can be prepared by impregnation or using a hot melt extrusion process (HME). Impregrantion involves the soaking of commercial filaments in solvent-based drug solutions, which results in low drug loading, and careful screening of compatible solvents are needed to avoid any solvent-induced damage to the filaments [

53,

54]. Drying the filaments to remove any toxic solvents altogether is also challenging. HME was most widely investigated for manufacturing drug-loaded filaments suitable for the FDM process. HME is a solvent-free, single-step process that can also be coupled with an FDM 3D printing process for establishing a continuous manufacturing line [

55,

56]. Various critical material, instrumental, and process parameters that play crucial roles in successfully fabricating pharmaceutical medications by employing the FDM process are discussed below.

2.4. Critical Material Properties

2.4.1. Mechanical Properties

The mechanical properties of the filament play an essential role in the successful printing of medications employing the FDM 3D printing process. Following the HME process, the filaments are collected as spools and loaded onto the FDM 3D printers to fabricate dosage forms. The filaments should have enough flexibility to be rolled into spools, making handling easier. While feeding the filament into the printer head, the filament has to pass between the gear rollers, pushing the filament continuously towards the melting zone in the heated nozzle. The gear rollers will exert a certain mechanical pressure on top of the filaments during the process [

57,

58]. Brittle filaments get damaged between the gear rollers, and soft filaments get coiled inside the printer head, interrupting the process. Thus, a balance between brittleness and flexibility needs to be maintained to be suitable for the FDM process. As the gear rollers push the filament towards the melting zone, the filament will also act as a piston for moving the molten material outside the nozzle. The mechanical properties of the filaments also get altered by any change in the filament diameter. Thus, ensuring consistent extrusion of filaments is crucial. Any impact of the conveyor belt on the filament dimensions has to be controlled. An inconsistent material feed rate into the extruder barrel will affect the fill volume and throughput, influencing the filament properties. Thus, the extrusion process has to be carefully optimized, and automation of the process would eliminate human error [

59]. To date, acceptance criteria for mechanical properties such as breaking force have yet to be established for the filaments to be suitable for the FDM 3D process since the mechanical properties greatly vary based on the filament composition.

2.4.2. Surface Morphology

The surface morphology of the filaments plays an important role in the successful printing of the dosage forms. The filaments with rough surface morphology get stuck inside the printer head, interrupting fabrication. The surface morphology of the filaments will also influence the resolution of the printed medication. Thus, a smooth surface of the filaments needs to be ensured to develop quality medications. The surface morphology of the filaments is affected by the HME process. Extrusion of the materials at low temperatures where the processing material is highly viscous would result in a rough surface of the filaments [

60,

61]. The presence of any un-dissolved particles would also result in a rough surface. The presence of undissolved particles will not only influence the resolution of the medications but will also result in blockage of the printer nozzle. The resolution of the medications printed using rough surface filaments can be controlled by increasing the printing temperature and reducing the printing speed. Thus, the surface morphology of the filaments needs to be controlled during the extrusion process.

2.4.3. Filament Dimension

The dimensions of the filament are another critical material quality attribute that plays an important role in determining the suitability of filaments for the FDM 3D printing process. The polymeric chains undergo compression during the extrusion process due to high mechanical stress induced onto the processing materials. Following the extrusion of the filaments from the extruder die, the polymeric chains will relax, resulting in the swelling of the filament diameter, called the “die swell” behavior [

62,

63]. Each type of FDM 3D printer accommodates different diameters of filaments. The die size connected to the extruder barrel must be selected based on the type of FDM 3D printer. Most commonly. The FDM 3D printers will accommodate filaments with diameters between 1.75 - 2.85 mm. Any filaments greater than the diameter the 3D printer can accommodate will not be suitable for processing. There is a need for advancement in the instrumentation of FDM 3D printers' efficiency to accommodate different filament dimensions between the gear rollers. During the process of HME, the die size needs to be selected based on the nature of polymeric materials. For materials with die-swell behavior, the size of the die nozzle needs to be selected to be smaller than the gap between the gear rollers, ensuring the suitability and processability of the filaments. Thus, filament dimensions are important and must be controlled during the HME process.

2.4.4. Rheological and Thermal Properties

Similar to the process of PAM or SSE, the rheological and thermal properties of the processing materials play an essential role in the successful fabrication of the medications. The melt viscosity and flow of the material are critical properties that must be carefully monitored. Both melt viscosity and flow of the material from the printer nozzle are temperature dependent, which can be controlled by increasing or decreasing temperature. The degree of bonding between the layers is higher for low-viscous materials than high-viscous materials. High viscous materials require a high amount of pressure to be exerted by the filament to push the molten material outside the printer nozzle, which might be challenging for brittle and soft filaments. Processing of highly viscous materials requires high extrusion and printing temperatures [

64,

65]. However, the processing temperature must be maintained below the degradation temperature of the drug substance, polymers, and other additive materials. In the case of high processing temperatures, the incorporation of plasticizers has to be studied to lower the melt viscosity and allow the glass transition temperature to process at low temperatures. For printing of low viscous materials, the temperature needs to be controlled to prevent deformation of the object being fabricated. Compared with the PAM process, FDM 3D printing is unreliable for highly viscous materials and requires high processing temperatures to reduce the melt viscosity [

66]. Thus, process temperature needs to be carefully optimized to control the rheological properties of the materials for the successful fabrication of quality medications.

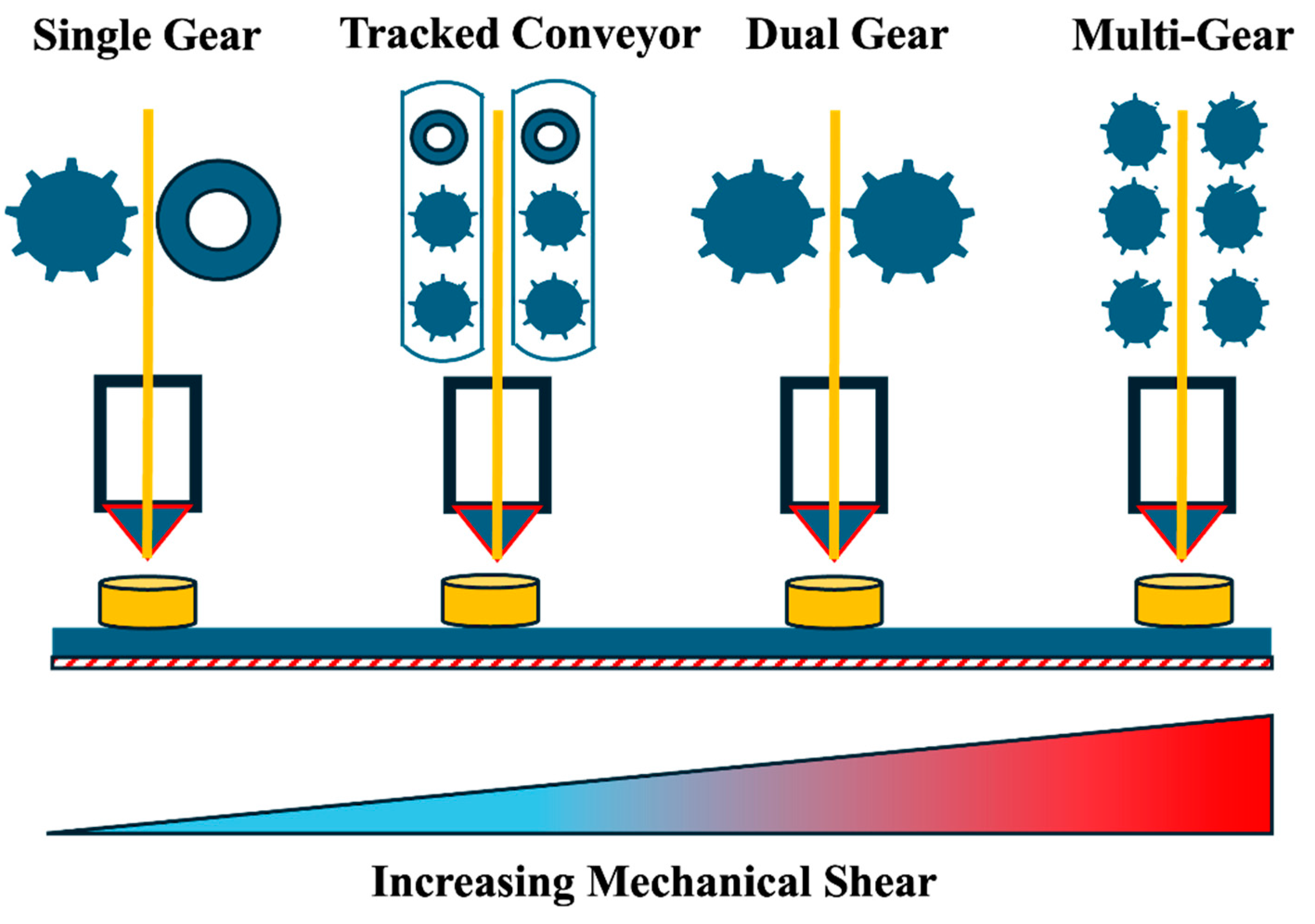

2.5. Critical Instrument Parameters

2.5.1. Gear Rollers

Within the instrumentation of an FDM 3D printer, the gear rollers are the key components that play a crucial role in successfully fabricating the medications. The gear rollers are essential in feeding the filaments into the printer head. Different gear rollers are available, such as normal, dual-gear, multi-gear, and tracked gear roller systems, as shown in

Figure 3. The majority of commercial FDM 3D printers are equipped with dual-gear roller systems. Compared with dual and multi-gear roller systems, the normal and tracked roller systems will exert a low level of mechanical shear on the filaments, making brittle filaments suitable for the process [

67,

68]. The location of gear rollers on the instrument also plays an important role in successful printing. Geater distance between the nozzle and gear rollers will exert greater mechanical pressure on the filaments making it unsuitable for brittle materials. Having the flexibility to change different gear roller systems for the same piece of instrument will be beneficial for processing the filaments with different mechanical properties.

2.5.2. Nozzle Size

The nozzle size is important in determining the resolution and printing time. Within the FDM 3D printer, the nozzle is the heating zone, which softens the filament and extrudes outside for deposition onto the build platform. With increasing nozzle size, the resolution of the printed material gets lowered [

69,

70]. Conversely, the printing time can be reduced by increasing the nozzle size. Different nozzle sizes are available in the market, ranging from 0.1 - 1.0 mm. The nozzle size of less than 0.4 mm results in longer printing time but delivers a high-resolution medication. Different construction nozzle materials, such as brass and stainless steel, are available on the market. Depending on the type of material being processed and the temperature required, the nozzle size and construction material need to be selected. For the processing of low viscous materials, a smaller nozzle size is beneficial for faster drying of the deposited layer and to prevent any deformation. For processing of high viscous material, a nozzle with a larger diameter is recommended. Utilizing a larger nozzle to process viscous materials requires less mechanical pressure to be applied to the filaments [

71]. The thickness of each printed layer depends on the diameter of the nozzle. Thus, the nozzle size has to be chosen based on the quality of the printed medication.

2.5.3. Cooling Fan and Build Platform

Following the extrusion of material from the printer nozzle, the cooling fan and build platform are the two other key instrument components determining the successful fabrication of medications. Most of the FDM 3D printers available in the market do not have any control over adjusting the cooling fan's speed. Faster cooling fan speed will result in rapid drying of the material before depositing it onto the build platform and affects the bonding and mechanical properties of the printlet. Similarly, a lower cooling rate will delay the drying process of low viscous materials, which might result in the deformation of the structure [

72]. Thus, an optimum cooling rate must be maintained to fabricate medication successfully.

The build platform provides the foundation support to the printing object throughout the process. Loos of bonding between the bottom layer and the build platform will interrupt the printing process. The material used to construct the build platform determines the success rate of the printing process. Only some polymers will have superior adhesion properties with the build platform. Depending on the nature of the processing materials, the compatible platform needs to be identified [

73]. Towards the end of the fabrication process, the object has to be quickly ejected without damaging the surface, which might influence the product's performance. The commercial equipment should be flexible when switching between different build platforms depending on the compatibility of processing materials. The platform construction material must be thermally stable to be suitable for the FDM 3D printing process.

2.6. Critical Process Parameters

2.6.1. Printing Temperature

The printing temperature is a critical process parameter determining the successful fabrication and quality of the medications. The process of FDM 3D printing requires the application of thermal energy to melt the drug-loaded polymeric filaments. The process cannot be carried at ambient temperatures and is impractical for thermolabile materials. Compared with the PAM or SSE process, the FDM process requires a higher temperature to melt the filaments. The material extrudes from the nozzle by gently applying pressure by the unmelted filament in the printer head [

74,

75]. The filament inside the printer head might not be capable of applying high pressure attributed to its mechanical properties compared with the pressure applied by the pistons in the PAM or SSE process. The processing materials' thermal properties must be studied, and the temperature must be maintained below the degradation temperature. Additionally, the nozzle temperature needs to be maintained below the melting point of the nozzle material of construction. The maximum recommended temperature by the equipment manufacturer has to be strictly followed. In the case of high viscous formulations where low viscosities cannot be achieved below the degradation temperature, the incorporation of plasticizers has to be studied. Usually, the FDM process requires 10 - 20 °C greater than the HME temperature for printing the dosage forms [

76]. Thus, various aspects need to be considered when optimizing the nozzle temperature.

2.6.2. Printing Speed

Printing speed is another critical process parameter that determines the mechanical integrity and quality of the 3D-printed medications. Printing speed needs to be optimized based on various factors, such as the viscosity of the processing material and the binding property of the material. Higher printing speed for low viscous materials will result in deformation of the printed dosage forms, affecting the quality. Meanwhile, faster printing speed for highly viscous materials will provide superior bonding and mechanical integrity for the dosage forms [

77,

78]. However, slower printing speeds will result in high resolution of the 3D printed medications.

2.6.3. Build Platform Temperature

Similar to the build platform material, the temperature of the build platform is also an essential critical process parameter for the successful fabrication of quality medications. Higher build platform temperatures might result in poor adhesion of printing material with the platform due to melting or softening of the initial support layer interrupting the printing process. Maintaining a low bed temperature will also result in poor material bonding with the platform [

79,

80]. Thus, the build platform temperature needs to be carefully optimized to develop 3D medications successfully. Maintaining a higher build platform temperature might also result in the dehydration of deposited material, resulting in shrinkage and loss of bonding between the successive layers affecting the mechanical properties [

81].

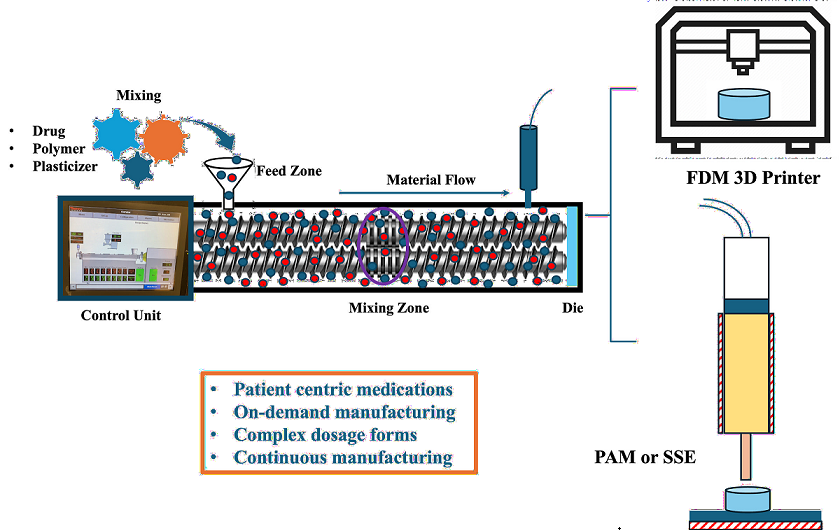

4. Coupling with HME

HME is a single-step continuous manufacturing process introduced earlier in the food, plastic, and rubber industries. Later, in the 1980s, the suitability of the HME process for developing amorphous solid dispersions of poorly water-soluble drug substances was investigated [

82,

83]. With the successful adaptation of the HME platform into the pharmaceutical industry for developing amorphous solid dispersions, its suitability for various other applications within the pharmaceutical sector was also studied [

84,

85,

86]. Today, the HME process is being most widely utilized in the pharmaceutical industries for developing amorphous solid dispersions and also for performing various types of granulations called twin screw granulation. Attributing to the solvent-free and single-step manufacturing process, the HME was employed in various continuous manufacturing lines coupling with suitable downstream manufacturing equipment and process analytical technology (PAT) tools [

87,

88,

89]. The instrumentation of HME includes a barrel enclosed with co-rotating or counter-rotating twin screws, a feeder, and a die connected at the discharge point. The physical blend of the formulation will be fed into the heated extruder barrel where the material gets exposed to thermal and mechanical shear [

50,

90,

91]. The screws inside the barrel consist of various elements, such as conveying and kneading elements. The conveying elements have no mixing property but will convey the material between the mixing zones. The mixing elements will impart a high level of mechanical shear onto the processing material and will exert distributive and dispersive mixing. The kneading elements can be configured into different levels of offset angles depending on the level of shear needed to be applied. With the increasing offset angle, the shear imparted onto the processing material will increase, and the conveying property will decrease. The processing material inside the barrel will be conveyed and pumped through the die connected at the discharge point [

92,

93,

94,

95,

96]. During the granulation process and semi-solid pastes' extrusion, the die connected at the discharge point can be removed. The critical process parameters include feed rate, barrel temperature, screw speed, torque, and screw configuration [

97].

In recent years, researchers from academia and industries have worked closely to couple HME with additive manufacturing processes for developing patient-centric medications. HME is the primary equipment for developing drug-loaded polymeric filaments used as stock material for fabricating 3D-printed medications using the FDM process. The filaments collected from the extrusion process can be transferred to the compounding pharmacies where on-demand patient-centric medications can be fabricated [

98,

99,

100]. To transform compounding pharmacies into digital pharmacies, the filaments' shelf life must be established. In addition, HME can be paired with the FDM 3D printing process for developing a continuous manufacturing line. Various PAT tools can be coupled to monitor the homogeneous distribution of drug substances, the diameter of the filaments, surface morphology, printing temperature, and build platform temperature [

101,

102].

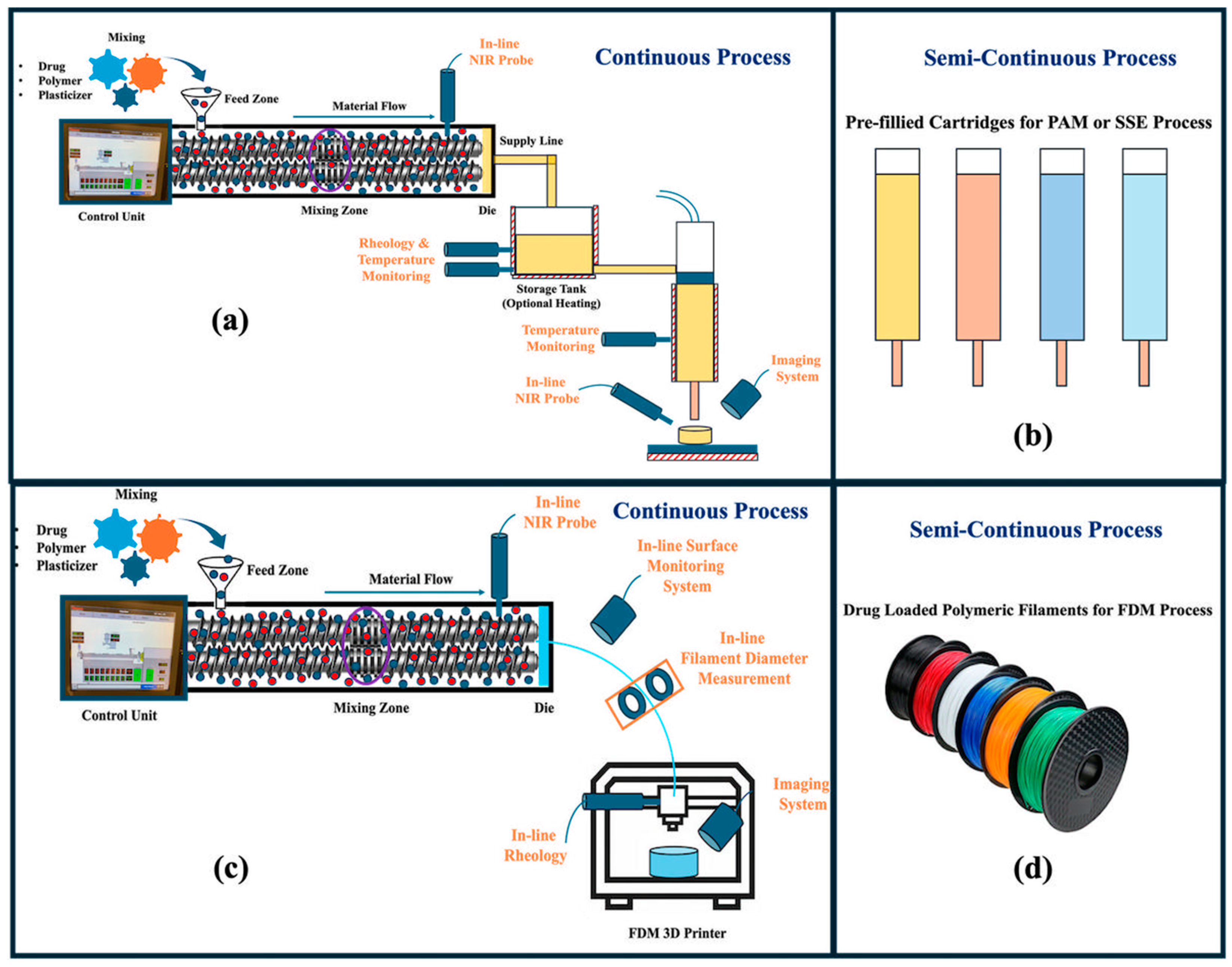

Similarly, the process of PAM or SSE can also be coupled with the HME process. By coupling HME with the PAM or SSE process, the pre-filled formulation cartridges can be prepared and shipped to the compounding pharmacies, where the desired medication can be printed for different doses and release profiles depending on the patient's needs [

103,

104]. Coupling with HME will also ensure and improve the homogeneous distribution of the drug within the cartridges. In the case of a solvent-assisted process, the cartridges can be supplied with powdered formulation, and the semi-solid paste can be prepared instantly by adding the required amount of solvent before printing. Along with a semi-continuous process, a continuous manufacturing line can be developed by coupling HME with PAM or SSE equipment. Various PAT tools to monitor the critical process parameters and quality attributes of the medications can be monitored and controlled [

35,

105,

106]. A detailed instrumentation of HME coupling with PAM or SSE and FDM platforms is shown in

Figure 4.

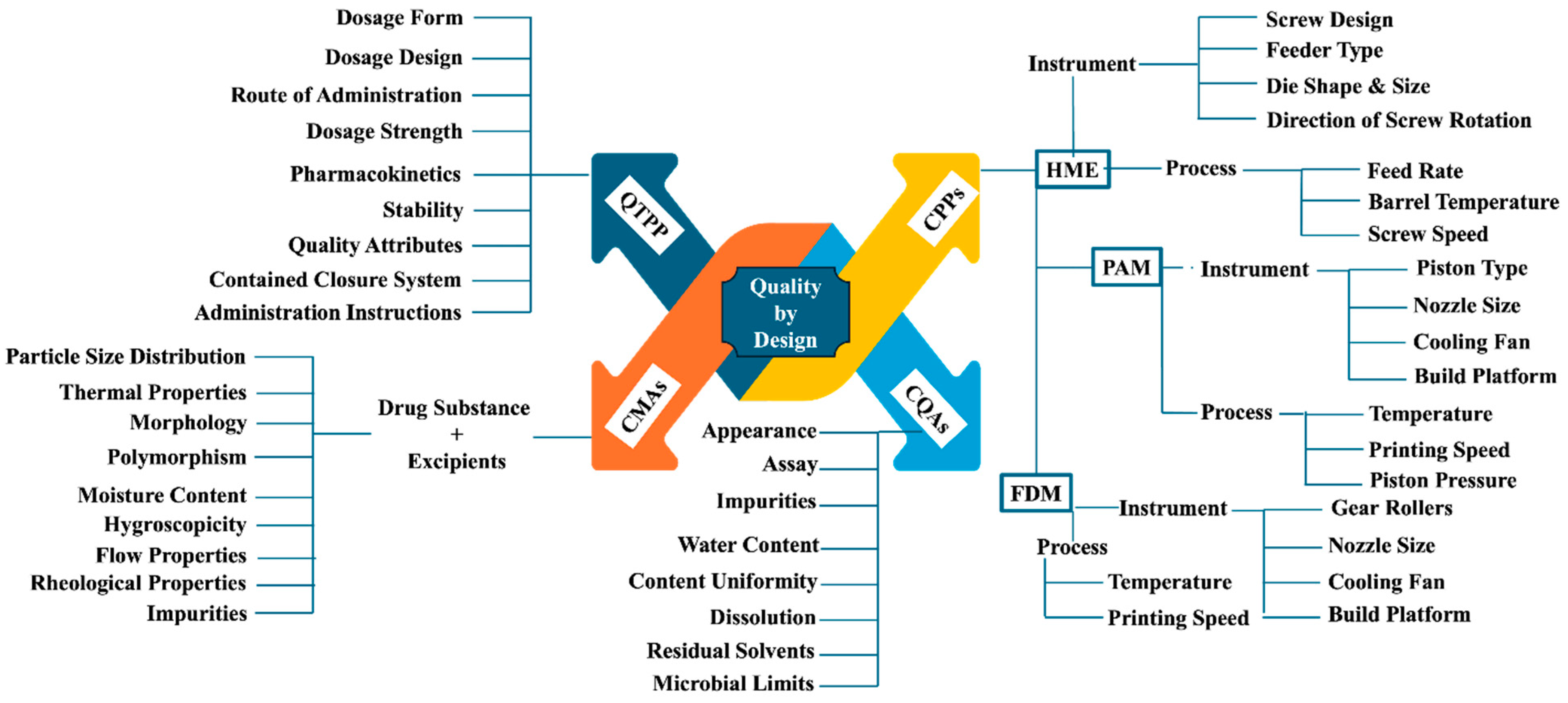

5. Quality by Design (QbD) Elements

QbD plays an important role in the successful development of drug products. A thorough understanding and control of critical material attributes (CMAs) and critical process parameters (CPPs) and their impact on the critical quality attributes (CQAs) of the drug product will enable the development of safe, efficacious, and quality products. ICH guidelines Q8(R2) (Pharmaceutical Development) discusses the implementation of QbD elements for developing robust medications in detail [

107,

108]. Implementing these guidelines will give an in-depth understanding of the process and formulation parameters and build the product's quality. The optimization of the process will ensure the reproducibility of the medications. The main goal of QbD is to develop a reliable and reproducible process for delivering safe, quality, and efficacious medicines to the patient population. QbD involves a step-by-step implementation of various QbD elements discussed below. Implementing QbD for developing patient-centric medications by employing an additive manufacturing process is essential for ensuring consistency in product quality [

109]. Much research is needed to understand the CMAs, CPPs, and their impact on the drug product CQAs.

5.1. Quality Targeted Product Profile (QTPP):

Any development activity begins with the drafting of the QTPP element. It serves as a reference guide for formulation scientists throughout the development phase. It provides developmental scientists with a blueprint for the characteristics of the drug product. Various elements of QTPP include dosage form, dosage design, route of administration, dosage strength, pharmacokinetics, stability, drug product quality attributes (appearance, assay, impurities, water content, content uniformity, dissolution, residual solvents, and microbial limits), container closure system, administration instructions and alternative methods of administration.

5.2. CQA’s

The CQA elements are listed within the QTPP section. However, the impact of process and material attributes on the CQAs of the drug product needs to be carefully monitored. Failure to maintain the CQAs of the drug product will affect the safety and efficacy of the product, resulting in potential risk to the patient population [

110]. Throughout the shelf life, the CQAs of the product need to be preserved. Prior knowledge, experience, and literature review are important for identifying the CQAs during early-stage development.

5.3. CMAs

The CMAs of the drug substance and the excipients utilized in the design and development of drug products play an important role and influence the CQAs. Identification of CMAs will help identify and optimize the CPPs. For example, the degradation temperature of the drug substance can be considered as a CMA, attributing to the thermal processing conditions. Based on the CMA of the drug substance, the process temperature can be identified as a CPP and must be maintained below the degradation temperature of the drug substance [

111].

5.4. CPPs

Identification of CPPs requires previous knowledge and experience of the process and identification of CMAs impacted by the process parameters, which will eventually affect the CQAs of the finished drug product [

112].

5.5. Risk Assessment:

Risk assessment is another critical aspect of building quality into the product. Once the CMAs, CPPs, and CQAs are identified, the effect of CMAs and CPPs on the drug product CQAs needs to be identified, and the level of risk needs to be determined [

113,

114]. The initial risk assessment involves the evaluation of risk associated with drug substance attributes (solid state form, particle size, solubility, moisture content, residual solvents, process impurities, chemical stability, and flow properties,) formulation variables (drug substance particle size, excipients, flow properties) and process variables (The effect of each unit operation process variable on the CQAs needs to be assessed) on the CQAs of the drug product needs to be assessed. Implementing risk assessment tools such as fish-bone diagrams or failure mode effect analysis (FMEA) will aid in better risk assessment tracking [

105]. In addition, by employing the design of experiments (DoE), the effect of CMAs and CPPs on the CQAs of drug products can be studied in detail, and it helps reduce risk severity by operating the process within the design space.

5.6. Control Strategy and Continuous Improvement:

Based on the knowledge gained from product and process development, a control strategy can be defined to ensure consistent delivery of product quality. A range or limit can be established for each aspect and must be strictly followed to develop a quality product. The various control strategies are discussed below.

CQAs: Need to be within the established limits to ensure the quality of the product.

CMAs: The drug substance and the excipient should comply with the specification and satisfy the pre-determined requirements to eliminate any associated risk.

CPPs: The process needs to be operated within the qualified and validated ranges to prevent any unwanted effect on the CQAs of drug products.

In-process controls: Throughout the manufacturing process, the critical process parameters must be monitored continuously to ensure they stay within the established range and the intermediate product meets the pre-established specification, directly influencing the final product CQAs.

Specifications: An acceptance criterion needs to be established within the specification to ensure product quality.

PAT: Implementation of PAT tools will help monitor the CMAs and CPPs, which are directly associated with the CQAs of drug products.

Real-time release testing (RTRT): RTRT involves in-line testing of the intermediate and finished drug product. Implementing RTRT will increase productivity and will reduce costs. For example, the uniformity of the drug within the formulation blend can be monitored by mounting a near-infrared (NIR) probe. This process will ensure the development of a quality and safe medication. Any discrepancies can be controlled immediately without being realized towards the end of the manufacturing during end product testing.

Even after commercialization, continuous monitoring and improvement of the product quality is needed, The trends in the manufacturing process need to be continuously monitored and corrected as needed. Quality metrics need to be implemented to track the yield and any defects. Any discrepancies must be resolved by proper measures utilizing corrective and preventive action (CAPA). Feedback from the manufacturing and end product users needs to be considered to find any improvement areas. Innovative technologies can be implemented to simplify the process and reduce the probability of incidents. Various elements of QbD are listed in

Figure 5.

6. Future Perspectives

In recent years, additive manufacturing has been the most widely explored method for developing patient-centric personalized medications. Much research is ongoing in academia and industries exploring the suitability and capability of various additive manufacturing techniques for developing pharmaceutical medications [

115,

116]. In 2021, the FDA approved an investigational new drug application (IND) for conducting first-in-human (FIH) clinical trials for rheumatoid arthritis using a 3D printed medication manufactured by Triastek, a Chinese pharmaceutical company specialized in developing 3D printed dosage forms [

117,

118]. This shows pharmaceutical companies' interest and future focus and the encouragement of regulatory agencies to explore and adapt novel manufacturing technologies for delivering safe and efficacious medications to the patient population. Additive manufacturing has been successfully implemented for developing various complex medical devices, and even regulatory agencies such as the FDA have released specific guidelines for the industries. Employing additive manufacturing will address various limitations associated with the current manufacturing technologies. The limitations related to tableting and encapsulation, such as poor compressibility, poor flow, capping, lamination, and high friability, can be avoided, and the developmental timelines and costs can be reduced drastically [

119,

120]. The scaleup of the additive manufacturing process can be achieved by increasing the printing speed and the number of printer heads on the build platform. The medication can be easily fabricated at the clinical sites for different dosage strengths without initiating the reformulation activities. Usually, any formulation composition or manufacturing change requires establishing the bioequivalence between two formulations, which is expensive and more time-consuming. Pharmaceutical industries will not be willing to change the formulations to ensure the product is being launched into the market. Still, they will face high-level challenges during scale-up and commercial manufacturing [

121]. By employing additive manufacturing, any change in the dose can be easily adjusted without changing the formulation composition, and the release profiles can be adjusted by studying different infill densities and patterns. This will save huge investment and time for the pharmaceutical industry.

In the future, the nozzle-based additive manufacturing techniques discussed in the current review article can transform into a single-step continuous manufacturing line by coupling with the HME process. Various PAT tools can be employed to monitor the critical process parameters and quality attributes. Any discrepancy in the process can be monitored and controlled, thereby developing a safe, efficacious, and quality product for the patient population. In addition, both PAM and FDM platforms can be established within the compounding pharmacies in the hospitals, and the material required for the fabrication process, such as pre-filled cartridges for PAM and drug-loaded polymeric filaments for the FDM process, can be supplied by the pharmaceutical companies. Thus, compounding pharmacies can be transformed into digital pharmacies to fabricate on-demand medications. Pediatric medications with different geometries, colors, and flavors can be fabricated to attract children and to stick them to the prescription medications. Complex medications such as polypills can be manufactured easily without challenging multilayer traditional compression processes [

122,

123,

124]. Overall, the additive manufacturing process for developing pharmaceutical medications answers various unmet needs of the pharmaceutical industries and the patient population. A detailed SWOT (strength, weakness, opportunities and threats) analysis critical for additive manufacturing is shown in

Figure 6.

7. Conclusion

In recent years, additive manufacturing has been widely explored for developing patient-centric medications. The complex medicines needed on demand for the patient population can be fabricated in emergencies. The performance of the medicines can be altered by modifying the infill densities, infill pattern, and geometry of the 3D design without undergoing reformulation activities. Adapting the additive manufacturing process will provide advanced capabilities for the pharmaceutical industries and address various unmet needs of traditional manufacturing platforms. The additive manufacturing platforms PAM and FDM can be implemented in compounding pharmacies or coupled with the HME process to develop a continuous manufacturing process. Medications' quality, safety, and efficacy can be ensured by employing various PAT tools. Still, a lot of research needs to be conducted to understand the effect of various factors on the quality of the medications before they are introduced into the industries for commercial manufacturing. Novel next-generation materials must be developed to be compatible with the thermal processing conditions. An advancement in instrumentation is also needed to comply with good manufacturing practice (GMP) standards, be compatible with the processing materials, and support commercial batch sizes. The successful implementation of the additive manufacturing platforms and the launch of various commercial products will revolutionize the entire pharmaceutical history.

Author Contributions

Nyavanandi, topic selection and design. Nyavanandi, Mandati, Vidiyala, Parupathi, Kolimi, Mamidi, literature review, content writing. Nyavanandi, Mamidi, final review and editing.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Khan, K.; Minhas, M.; Badshah, S.; Suhail, M.; Sciences, A.A.-L. ; 2022, undefined Overview of Nanoparticulate Strategies for Solubility Enhancement of Poorly Soluble Drugs. Life Sci 2022, 291, 120301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhalani, D.V.; Nutan, B.; Kumar, A.; Singh Chandel, A.K. Bioavailability Enhancement Techniques for Poorly Aqueous Soluble Drugs and Therapeutics. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva, F.L.O.; Marques, M.B.D.F.; Kato, K.C.; Carneiro, G. Nanonization Techniques to Overcome Poor Water-Solubility with Drugs. Expert Opin Drug Discov 2020, 15, 853–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazzo, G.C.; Pezzini, B.R.; Stulzer, H.K. Eutectic Mixtures as an Approach to Enhance Solubility, Dissolution Rate and Oral Bioavailability of Poorly Water-Soluble Drugs. Int J Pharm 2020, 588, 119741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B.; Baidya, A.T.K.; Mathew, A.T.; Yadav, A.K.; Kumar, R. Structural Modification Aimed for Improving Solubility of Lead Compounds in Early Phase Drug Discovery. Bioorg Med Chem 2022, 56, 116614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tekade, A.R.; Yadav, J.N. A Review on Solid Dispersion and Carriers Used Therein for Solubility Enhancement of Poorly Water Soluble Drugs. Adv Pharm Bull 2020, 10, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pires, P.C.; Rodrigues, M.; Alves, G.; Santos, A.O. Strategies to Improve Drug Strength in Nasal Preparations for Brain Delivery of Low Aqueous Solubility Drugs. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.K. Liposomes for Enhanced Bioavailability of Water-Insoluble Drugs: In Vivo Evidence and Recent Approaches. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Wei, Y.; Lu, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhang, J.; Gao, Y.; Qian, S. Co-Amorphous Systems for the Delivery of Poorly Water-Soluble Drugs: Recent Advances and an Update. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2020, 17, 1411–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes, A.J.; McKenna, P.E.; Ramöller, I.K.; Naser, Y.A.; Volpe-Zanutto, F.; Li, M.; Abbate, M.T.A.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, C.; Abu-Ershaid, J.M.; et al. Microarray Patches: Poking a Hole in the Challenges Faced When Delivering Poorly Soluble Drugs. Adv Funct Mater 2021, 31, 2005792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathor, S.; Bhatt, D.C. Formulation, Characterization, and Pharmacokinetic Evaluation of Novel Glipizide-Phospholipid Nano-Complexes with Improved Solubility and Bio-Availability. Pharm Nanotechnol 2022, 10, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barradas, T.N.; de Holanda e Silva, K.G. Nanoemulsions of Essential Oils to Improve Solubility, Stability and Permeability: A Review. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2020 19:2 2020, 19, 1153–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Lee, S.E.; Pyo, Y.C.; Tran, P.; Park, J.S. Solubility Enhancement and Application of Cyclodextrins in Local Drug Delivery. J Pharm Investig 2020, 50, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Md.K.; Moshikur, R.M.; Wakabayashi, R.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Kamiya, N.; Goto, M. Biocompatible Ionic Liquid Surfactant-Based Microemulsion as a Potential Carrier for Sparingly Soluble Drugs. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 2020, 8, 6263–6272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Chowdhury, M.R.; Wakabayashi, R.; Kamiya, N.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Goto, M. Ionic Liquid-In-Oil Microemulsions Prepared with Biocompatible Choline Carboxylic Acids for Improving the Transdermal Delivery of a Sparingly Soluble Drug. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, D.; Ramsey, J.D.; Kabanov, A.V. Polymeric Micelles for the Delivery of Poorly Soluble Drugs: From Nanoformulation to Clinical Approval. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2020, 156, 80–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuckin, M.B.; Wang, J.; Ghanma, R.; Qin, N.; Palma, S.D.; Donnelly, R.F.; Paredes, A.J. Nanocrystals as a Master Key to Deliver Hydrophobic Drugs via Multiple Administration Routes. Journal of controlled release 2022, 345, 334–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, A.H.; Smått, J.H.; Govardhanam, N.P.; Ibrahim, H.M.; Ismael, H.R.; Afouna, M.I.; Samy, A.M.; Rosenholm, J.M. Formulation and Optimization of Drug-Loaded Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticle-Based Tablets to Improve the Dissolution Rate of the Poorly Water-Soluble Drug Silymarin. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2020, 142, 105103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Otte, A.; Park, K. Evolution of Drug Delivery Systems: From 1950 to 2020 and Beyond. Journal of Controlled Release 2022, 342, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.L.; Cheng, W.T.; Chen, L.C.; Ho, H.O.; Lin, S.Y.; Hsieh, C.M. Honokiol/Magnolol-Loaded Self-Assembling Lecithin-Based Mixed Polymeric Micelles (Lb MPMs) for Improving Solubility to Enhance Oral Bioavailability. Int J Nanomedicine 2021, 16, 651–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, K.; Moseson, D.E.; Taylor, L.S. T: Solubility Advantage, 2024.

- He, M.; Zheng, W.; Wang, N.; Gao, H.; Ouyang, D.; Huang, Z. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Drug Solubilization Behavior in Surfactant and Cosolvent Injections. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, N.; Jennotte, O.; Gasparrini, Y.; Vandenbroucke, F.; Lechanteur, A.; Evrard, B. Cannabidiol Aqueous Solubility Enhancement: Comparison of Three Amorphous Formulations Strategies Using Different Type of Polymers. Int J Pharm 2020, 589, 119812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Merwe, J.; Steenekamp, J.; Steyn, D.; Hamman, J. The Role of Functional Excipients in Solid Oral Dosage Forms to Overcome Poor Drug Dissolution and Bioavailability. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Kumar, M.; Choudhary, D.; Chopra, S.; Bhatia, A. 3D Printing Technology in Drug Delivery: Polymer Properties and Applications. J Dispers Sci Technol 2023, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muehlenfeld, C.; Duffy, P.; Yang, F.; Zermeño Pérez, D.; El-Saleh, F.; Durig, T. Excipients in Pharmaceutical Additive Manufacturing: A Comprehensive Exploration of Polymeric Material Selection for Enhanced 3D Printing. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishnoi, M.; Ankita; Mody, N.; Jain, A. Additive Manufacturing Strategies for Personalized Drug Delivery Systems and Medical Devices. In Medical Additive Manufacturing: Concepts and Fundamentals; Elsevier, 2024; pp. 619–647 ISBN 9780323953832.

- Muehlenfeld, C.; Duffy, P.; Yang, F.; Zermeño-Pérez, D.; Durig, T. Polymers for Pharmaceutical 3D Printing: Printability and Critical Insight into Material Properties. In 3D Printing; Springer, Cham, 2024; pp. 97–137 ISBN 978-3-031-46015-9.

- Anaya, B.J.; Cerda, J.R.; D’Atri, R.M.; Yuste, I.; Luciano, F.C.; Kara, A.; Ruiz, H.K.; Ballesteros, M.P.; Serrano, D.R. Engineering of 3D Printed Personalized Polypills for the Treatment of the Metabolic Syndrome. Int J Pharm 2023, 642, 123194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M.; Wahab, A.; Khan, S.U.; Naeem, M.; ur Rehman, K.; Ali, H.; Ullah, A.; Khan, A.; Khan, N.R.; Rizg, W.Y.; et al. 3D Printing Technology: A New Approach for the Fabrication of Personalized and Customized Pharmaceuticals. Eur Polym J 2023, 195, 112240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizam, M.; Purohit, R.; Taufik, M. 3D Printing in Healthcare: A Review on Drug Printing, Challenges and Future Perspectives. Mater Today Commun 2024, 40, 110199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhindo, D.; Elkanayati, R.; Srinivasan, P.; Repka, M.A.; Ashour, E.A. Recent Advances in the Applications of Additive Manufacturing (3D Printing) in Drug Delivery: A Comprehensive Review. AAPS PharmSciTech 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.A.; Algahtani, M.S.; Ahmad, M.Z.; Ahmad, J. Optimization of Semisolid Extrusion (Pressure-Assisted Microsyringe)-Based 3D Printing Process for Advanced Drug Delivery Application. Annals of 3D Printed Medicine 2021, 2, 100008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Aita, I. Manufacturing of Solid Dosage Forms Using Pressure-Assisted Microsyringe 3D-Printing, 2021.

- Seoane-Viaño, I.; Januskaite, P.; Alvarez-Lorenzo, C.; Basit, A.W.; Goyanes, A. Semi-Solid Extrusion 3D Printing in Drug Delivery and Biomedicine: Personalised Solutions for Healthcare Challenges. Journal of Controlled Release 2021, 332, 367–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Aita, I.; Rahman, J.; Breitkreutz, J.; Quodbach, J. 3D-Printing with Precise Layer-Wise Dose Adjustments for Paediatric Use via Pressure-Assisted Microsyringe Printing. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2020, 157, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auriemma, G.; Tommasino, C.; Falcone, G.; Esposito, T.; Sardo, C.; Aquino, R.P. Additive Manufacturing Strategies for Personalized Drug Delivery Systems and Medical Devices: Fused Filament Fabrication and Semi Solid Extrusion. Molecules 2022, 27, 2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez Gutiérrez, C.L.; Cottone, F.; Pagano, C.; Di Michele, A.; Puglia, D.; Luzi, F.; Dominici, F.; Sinisi, R.; Ricci, M.; Viseras Iborra, C.A.; et al. The Optimization of Pressure-Assisted Microsyringe (PAM) 3D Printing Parameters for the Development of Sustainable Starch-Based Patches. Polymers (Basel) 2023, 15, 3792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panraksa, P.; Zhang, B.; Rachtanapun, P.; Jantanasakulwong, K.; Qi, S.; Jantrawut, P. “Tablet-in-Syringe”: A Novel Dosing Mechanism for Dysphagic Patients Containing Fast-Disintegrating Tablets Fabricated Using Semisolid Extrusion 3D Printing. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, J.; Quodbach, J. Versatility on Demand – The Case for Semi-Solid Micro-Extrusion in Pharmaceutics. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2021, 172, 104–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyser, A.J.; Mahmoud, M.Y.; Herold, S.E.; Lewis, W.G.; Lewis, A.L.; Steinbach-Rankins, J.M.; Frieboes, H.B. Formulation and Characterization of Pressure-Assisted Microsyringe 3D-Printed Scaffolds for Controlled Intravaginal Antibiotic Release. Int J Pharm 2023, 641, 123054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrero, C.; Urpí, L.; Aguilar-de-Leyva, A.; Mora-Castaño, G.; Linares, V.; Millán-Jiménez, M.; Martínez de Ilarduya, A.; Caraballo, I. Application of Ultrasound-Assisted Compression and 3D-Printing Semi-Solid Extrusion Techniques to the Development of Sustained-Release Drug Delivery Systems Based on a Novel Biodegradable Aliphatic Copolyester. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 2024, 95, 105652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizam, M.; Purohit, R.; Taufik, M. Extrusion Based Additive Manufacturing of Medicines. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceedings; American Institute of Physics, February 20 2024; Vol. 3007, p. 100046.

- Tagami, T.; Okamura, M.; Ogawa, K.; Ozeki, T. Fabrication of Mucoadhesive Films Containing Pharmaceutical Ionic Liquid and Eudragit Polymer Using Pressure-Assisted Microsyringe-Type 3D Printer for Treating Oral Mucositis. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Racaniello, G.F.; Silvestri, T.; Pistone, M.; D’Amico, V.; Arduino, I.; Denora, N.; Lopedota, A.A. Innovative Pharmaceutical Techniques for Paediatric Dosage Forms: A Systematic Review on 3D Printing, Prilling/Vibration and Microfluidic Platform. J Pharm Sci 2024, 113, 1726–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Belton, P.; Teoh, X.Y.; Gleadall, A.; Bibb, R.; Qi, S. An Investigation into the Effects of Ink Formulations of Semi-Solid Extrusion 3D Printing on the Performance of Printed Solid Dosage Forms. J Mater Chem B 2023, 12, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, N.L.; Leão, J.; de Oliveira, T.V.; Beck, R.C.R. Semi-Solid Extrusion (SSE) in Pharmaceuticals. In Additive Manufacturing in Pharmaceuticals; Springer, Singapore, 2023; pp. 171–200 ISBN 978-981-99-2404-2.

- Mathew, E.; Pitzanti, G.; Larrañeta, E.; Lamprou, D.A. 3D Printing of Pharmaceuticals and Drug Delivery Devices. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Kang, D.; Liu, B.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Gao, X.; Zheng, A. Feasibility of Developing Hospital Preparation by Semisolid Extrusion 3D Printing: Personalized Amlodipine Besylate Chewable Tablets. Pharm Dev Technol 2022, 27, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seoane-Viaño, I.; Trenfield, S.J.; Basit, A.W.; Goyanes, A. Translating 3D Printed Pharmaceuticals: From Hype to Real-World Clinical Applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2021, 174, 553–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumpa, N.; Butreddy, A.; Wang, H.; Komanduri, N.; Bandari, S.; Repka, M.A. 3D Printing in Personalized Drug Delivery: An Overview of Hot-Melt Extrusion-Based Fused Deposition Modeling. Int J Pharm 2021, 600, 120501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandari, S.; Nyavanandi, D.; Dumpa, N.; Repka, M.A. Coupling Hot Melt Extrusion and Fused Deposition Modeling: Critical Properties for Successful Performance. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2021, 172, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nashed, N.; Lam, M.; Nokhodchi, A. A Comprehensive Overview of Extended Release Oral Dosage Forms Manufactured through Hot Melt Extrusion and Its Combination with 3D Printing. Int J Pharm 2021, 596, 120237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Xu, P.; Chung, S.; Bandari, S.; Repka, M.A. Fabrication of Bilayer Tablets Using Hot Melt Extrusion-Based Dual-Nozzle Fused Deposition Modeling 3D Printing. Int J Pharm 2022, 624, 121972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viidik, L.; Vesala, J.; Laitinen, R.; Korhonen, O.; Ketolainen, J.; Aruväli, J.; Kirsimäe, K.; Kogermann, K.; Heinämäki, J.; Laidmäe, I.; et al. Preparation and Characterization of Hot-Melt Extruded Polycaprolactone-Based Filaments Intended for 3D-Printing of Tablets. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2021, 158, 105619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Feng, S.; Almotairy, A.; Bandari, S.; Repka, M.A. Development of Multifunctional Drug Delivery System via Hot-Melt Extrusion Paired with Fused Deposition Modeling 3D Printing Techniques. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2023, 183, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omari, S.; Ashour, E.A.; Elkanayati, R.; Alyahya, M.; Almutairi, M.; Repka, M.A. Formulation Development of Loratadine Immediate- Release Tablets Using Hot-Melt Extrusion and 3D Printing Technology. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 2022, 74, 103505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyavanandi, D.; Mandati, P.; Narala, S.; Alzahrani, A.; Kolimi, P.; Pradhan, A.; Bandari, S.; Repka, M.A. Feasibility of High Melting Point Hydrochlorothiazide Processing via Cocrystal Formation by Hot Melt Extrusion Paired Fused Filament Fabrication as a 3D-Printed Cocrystal Tablet. Int J Pharm 2022, 628, 122283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.; Xu, P.; Zhang, J.; Bandari, S.; Repka, M.A. Development of Controlled Release Oral Dosages by Density Gradient Modification via Three-Dimensional (3D) Printing and Hot-Melt Extrusion (HME) Technology. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 2022, 71, 103355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshkar, S.; Rathi, M.; Zambad, S.; Gandhi, K. Hot Melt Extrusion and Its Application in 3D Printing of Pharmaceuticals. Curr Drug Deliv 2021, 18, 387–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumpa, N.R.; Bandari, S.; Repka, M.A. Novel Gastroretentive Floating Pulsatile Drug Delivery System Produced via Hot-Melt Extrusion and Fused Deposition Modeling 3D Printing. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, G.G.; Figueiredo, S.; Fernandes, A.I.; Pinto, J.F. Polymer Selection for Hot-Melt Extrusion Coupled to Fused Deposition Modelling in Pharmaceutics. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vo, A.Q.; Zhang, J.; Nyavanandi, D.; Bandari, S.; Repka, M.A. Hot Melt Extrusion Paired Fused Deposition Modeling 3D Printing to Develop Hydroxypropyl Cellulose Based Floating Tablets of Cinnarizine. Carbohydr Polym 2020, 246, 116519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Li, J.; Ashour, E.A.; Chung, S.; Wang, H.; Vemula, S.K.; Repka, M.A. Development of Multiple Structured Extended Release Tablets via Hot Melt Extrusion and Dual-Nozzle Fused Deposition Modeling 3D Printing. Int J Pharm 2024, 653, 123905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandati, P.; Dumpa, N.; Alzahrani, A.; Nyavanandi, D.; Narala, S.; Wang, H.; Bandari, S.; Repka, M.A.; Tiwari, S.; Langley, N. Hot-Melt Extrusion-Based Fused Deposition Modeling 3D Printing of Atorvastatin Calcium Tablets: Impact of Shape and Infill Density on Printability and Performance. AAPS PharmSciTech 2022, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponsar, H.; Wiedey, R.; Quodbach, J. Hot-Melt Extrusion Process Fluctuations and Their Impact on Critical Quality Attributes of Filaments and 3D-Printed Dosage Forms. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Bandari, S.; Repka, M.A. Investigation of Poly(2-Ethyl-2-Oxazoline) as a Novel Extended Release Polymer for Hot-Melt Extrusion Paired with Fused Deposition Modeling 3D Printing. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 2022, 74, 103558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyavanandi, D.; Narala, S.; Repka, M.A. Hot-Melt Extrusion Paired Fused Deposition Modeling 3D Printing: Development of Pharmaceutical Medications. In 3D Printing; Springer, Cham, 2024; pp. 169–194 ISBN 978-3-031-46015-9.

- Thanawuth, K.; Sutthapitaksakul, L.; Konthong, S.; Suttiruengwong, S.; Huanbutta, K.; Dass, C.R.; Sriamornsak, P. Impact of Drug Loading Method on Drug Release from 3D-Printed Tablets Made from Filaments Fabricated by Hot-Melt Extrusion and Impregnation Processes. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Digkas, T.; Porfire, A.; Van Renterghem, J.; Samaro, A.; Borodi, G.; Vervaet, C.; Crișan, A.G.; Iurian, S.; De Beer, T.; Tomuta, I. Development of Diclofenac Sodium 3D Printed Cylindrical and Tubular-Shaped Tablets through Hot Melt Extrusion and Fused Deposition Modelling Techniques. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lu, A.; Thakkar, R.; Zhang, Y.; Maniruzzaman, M. Development and Evaluation of Amorphous Oral Thin Films Using Solvent-Free Processes: Comparison between 3D Printing and Hot-Melt Extrusion Technologies. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavřel, F.; Novák, M.; Kroupová, J.; Beveridge, C.; Štěpánek, F.; Ruphuy, G. Development of Hot-Melt Extrusion Method to Produce Hydroxyapatite/Polycaprolactone Composite Filaments. Adv Eng Mater 2021, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almotairy, A.; Alyahya, M.; Althobaiti, A.; Almutairi, M.; Bandari, S.; Ashour, E.A.; Repka, M.A. Disulfiram 3D Printed Film Produced via Hot-Melt Extrusion Techniques as a Potential Anticervical Cancer Candidate. Int J Pharm 2023, 635, 122709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.; Srinivasan, P.; Zhang, P.; Bandari, S.; Repka, M.A. Development of Ibuprofen Tablet with Polyethylene Oxide Using Fused Deposition Modeling 3D-Printing Coupled with Hot-Melt Extrusion. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 2022, 76, 103716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Yang, W.; Bu, Y.; Yu, M.; Xu, M.; Guo, J.; Ni, W.; Jia, Y.; Zhang, J. Patient-Focused Programable Release Indomethacin Tablets Prepared via Conjugation of Hot Melt Extrusion (HME) and Fused Depositional Modeling (FDM) -3D Printing Technologies. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 2024, 97, 105797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nashed, N.; Chan, S.; Lam, M.; Ghafourian, T.; Nokhodchi, A. Effect of PH, Ionic Strength and Agitation Rate on Dissolution Behaviour of 3D-Printed Tablets, Tablets Prepared from Ground Hot-Melt Extruded Filaments and Physical Mixtures. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabriz, A.G.; Scoutaris, N.; Gong, Y.; Hui, H.W.; Kumar, S.; Douroumis, D. Investigation on Hot Melt Extrusion and Prediction on 3D Printability of Pharmaceutical Grade Polymers. Int J Pharm 2021, 604, 120755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, J.; da Silva, G.S.; Velho, M.C.; Beck, R.C.R. Eudragit®: A Versatile Family of Polymers for Hot Melt Extrusion and 3D Printing Processes in Pharmaceutics. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giri, B.R.; Song, E.S.; Kwon, J.; Lee, J.H.; Park, J.B.; Kim, D.W. Fabrication of Intragastric Floating, Controlled Release 3D Printed Theophylline Tablets Using Hot-Melt Extrusion and Fused Deposition Modeling. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wang, H.; Chung, S.; Li, J.; Vemula, S.K.; Repka, M.A. Fabrication of Suppository Shells via Hot-Melt Extrusion Paired with Fused Deposition Modeling 3D Printing Techniques. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 2024, 94, 105491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Y.H.; Yu, G.; Zhao, X.; Li, S.X.; He, X.L.; Tian, C.X.; Li, Z.Y. Exit Morphology and Mechanical Property of FDM Printed PLA: Influence of Hot Melt Extrusion Process. Adv Manuf 2023, 11, 56–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]