1. Introduction

Crystallization is of particular importance in the pharmaceutical industry, being involved in about 90 % of the manufacturing processes of drug substances or active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), respectively [

1]. APIs are commonly obtained as crystalline solids at the end of the downstream process. Thereby, APIs are mainly highly specific and, thus, chemically complex, resulting in low bioavailability [

2]. Accordingly, the specific adjustment of particle specifications, such as particle size, is crucial concerning the dissolution behavior of APIs. Crystallization as a separation method highly influences the critical quality attributes (CQAs) of the product particles like particle size distribution (PSD), product purity, and particle morphology [

3,

4,

5]. The crystallization process starts from prepurified solution during workup after drug substance synthesis. In the crystallization step, the target component is isolated as solid phase from a liquid phase. The subsequent solid-liquid separation, washing and drying of the particles completes the crystal process chain (CPC) and aims at preserving the PSD, achieving a high product purity and low residual moisture [

6].

Especially the processes within the CPC during drug substance manufacturing are still predominantly operated in batch mode. However, a paradigm shift towards continuous processes is currently taking place, as these provide numerous benefits. These include the elimination of batch-to-batch variability, increased space-time yield, and simplified scale-up by, for example, numbering-up due to reduced plant volumes. This enables the use of research and development (R&D) equipment for industrial production just by increasing the runtime, resulting in a reduced time-to-market. [

7,

8]

Developing an end-to-end continuous manufacturing process for small-scale API production of 250 - 1000 kg a

-1, from the raw material treatment to the final dosage form [

9], requires, especially for pharmaceutical production, the realization of continuous upstream, crystallization, product isolation, and final formulation processes, ensuring the continuous production of on-spec products [

4]. This study focuses on the continuous CPC from continuous crystallization to continuous product isolation.

A major challenge is the connection of the respective unit operations for continuous crystallization and product isolation [

9,

10]. In our previous study, the successful coupling of continuous crystallization with the slug flow crystallizer (SFC) and continuous product isolation with the continuous vacuum screw filter (CVSF) was already demonstrated [

11]. However, continuous seeding of the SFC was required, which is a bottleneck of the continuous CPC. Accordingly, the decoupling of the nucleation and crystal growth process into separate units eliminates the bottleneck by providing an independent control of both processes, leading to an improved product quality control as well as an increased process efficiency [

10]. With regard to continuous crystal growth, various concepts have already been elaborated, which are classified into two classes: mixed-suspension mixed-product removal (MSMPR) and tubular plug flow crystallizer (PFC) [

4,

5,

8,

9]. In this work, the SFC was used as a continuous crystal growth zone. The SFC belongs to the class of tubular PFCs. The concept of the SFC is based on a segmented flow of two immiscible fluids resulting in a narrow and equal residence time distribution (RTD) of the solid and liquid phases despite laminar flow conditions. Therefore, back-mixing effects can be avoided and a reproducible narrow PSD at the end of the process is achieved [

12]. In this work, synthetic air is used to segment the product stream, enabling an effective separation of the segmenting fluid and a high product purity in the subsequent downstream process. The wall friction is responsible for the generation of internal vortices in the slugs, resulting in an effective and gentle suspension of the particles without the use of external equipment. In terms of specific adjustment of the desired particle size, the SFC offers various degrees of freedom. Based on the kinematically limited crystal growth, the residence time (RT) can be regulated by the tubing length and the volume flow rate. In addition, the driving force for crystal growth in the SFC is realized by cooling via a tube-in-tube system along the SFC, whereby the crystal growth can specifically be influenced by the cooling rate. More detailed information concerning the specific setup of the used SFC can be found in the literature [

9,

10,

13,

14,

15].

Commonly, the apparatuses for continuous crystal growth processes require the supply of seed crystals [

16]. However, the addition of seed crystals in a crystallization process could lead to process contaminations, which has to be avoided, particularly in the pharmaceutical industry [

15]. Moreover, the particle properties of the seed crystals are crucial for the final product quality, resulting in high requirements for the seed crystal preparation process and, thus, a high time effort [

15,

17]. Furthermore, long-term operation cannot be realized due to the continuous supply of seed crystals. Accordingly, the demand for a continuous

in-situ nucleator in the context of an end-to-end continuous CPC is high. In this study, the design of a continuous

in-situ nucleator for coupling to various types of continuous crystallizers is presented.

There are various concepts to realize a continuous nucleation available. These include gassing-induced nucleation [

18], sonocrystallization [

19], impinging jet [

20], and antisolvent nucleation. The selected nucleation method for the designed nucleator in this work is antisolvent nucleation, which is based on lowering the solubility of a solute by the addition of an antisolvent [

17,

21]. This method requires a low energy input and is suitable for thermally sensitive substances [

21]. Additionally, precise adjustment of the degree of supersaturation is possible via the mass of added antisolvent independent of the temperature. Various technical concepts ensuring a continuous, effective, and rapid mixing process of two liquid streams, as fundamental requirements of an

in-situ nucleator based on antisolvent nucleation or precipitation, are presented in the literature. The microporous tube-in-tube microchannel reactor (MTMCR) [

22], the spinning disc reactor (SDR) [

23], and the high-gravity antisolvent precipitation (HGAP) [

24] were investigated for antisolvent precipitation of nanoparticles of poorly water-soluble substances. The membrane-assisted antisolvent crystallization (MAAC) as antisolvent nucleation technology was tested for the substance system erythritol/water with ethanol as antisolvent by

Li et al. [

25].

Engler et al. [

26] investigated convective passive micromixers in a T-shape with respect to mixing quality and mixing time. These T-mixers are considered in the study of

Engler et al. [

26] for application as microreactors for chemical reactions. The aim is to realize an efficient mixing process with short mixing times to ensure that the mixing process is completed before the reaction starts. This objective can also be applied to the process of antisolvent nucleation, where the mixing time should be shorter than the induction time. A T-shaped convective passive mixer offers a rapid and effective diffusive micromixing with the support of convective mixing under laminar conditions [

26]. Moreover, the T-shaped micromixer provides higher mixing efficiency and smaller dead zones compared to conventional Y-shaped micromixers [

27]. Since the concepts for antisolvent precipitation or nucleation presented above are very challenging due to the complex relationships between process and design parameters, the passive T-shaped micromixer was selected as the most promising concept for the design of a continuous

in-situ nucleator in this study. Accordingly, the T-mixer represents a simple, robust, compact, and reliable unit without moving components and external energy input, keeping the investment, operating, and maintenance costs comparatively low. In the context of an end-to-end continuous small-scale drug substance manufacturing process, starting from continuous nucleation in the nucleator to crystal growth in the SFC, continuous product isolation is finally required to obtain free-flowing particles at the end of the process.

The continuous product isolation, including solid-liquid separation, washing and drying, is essential in terms of maintaining CQAs. The patented continuous vacuum screw filter (CVSF) combines the process steps filtration, washing and drying in a modular design [

28]. Due to the modular setup of the CVSF, different configurations of the filtration, washing and drying modules can be realized, resulting in a high flexibility of the apparatus regarding various applications and operating points [

6,

29,

30]. The respective modules are tubular glass bodies, which are connected via flanges. The suspension from the preceding crystallization process is fed into the first module, where the filtration step takes place using an applied vacuum and a filter frit incorporated at the bottom of the glass body. The formed filter cake is transported axially through the apparatus by a rotating screw into subsequent modules for further process steps like washing and drying. Fundamental requirements for the continuous product isolation are the preservation of the CQAs designed in the preceding crystallization process and the production of free-flowing particles at the end of the process [

6]. In previous studies, we demonstrated for bipyramidal

l-alanine particles in aqueous solution and a CVSF configuration consisting of filtration and two-stage washing for suspension volume flow rates of up to 84 mL min

-1 and a solid loading of 6 wt.-% that the targeted residual moisture of less than 1 %, the preservation of PSD, and a narrow RTD of the solid phase are ensured [

6,

30]. Furthermore, the coupling of the SFC as a continuous crystallizer with the CVSF for continuous product isolation was successfully proven [

11].

The coupling of various continuous unit operations requires an extensive characterization of the individual apparatuses in order to meet the high requirements of a reproducible high product quality. The characterization of an apparatus includes the understanding of the relationships between input and output parameters and is essential to ensure the compatibility of different apparatuses (nucleator, crystal growth zone, product isolation) in the context of a continuous integrated process [

5,

8]. The definition of CQAs is decisive for the quality-by-design (QbD) approach in order to evaluate the influence of the critical process parameters (CPPs) on the integrated process performance [

8].

The design of the nucleator needs to meet the requirements for compatibility with the respective crystallizer used. Accordingly, the nucleator must generate a sufficient high number of nuclei to prevent fouling in the growth zone and to achieve the highest possible yield without the occurrence of secondary nucleation. We postulate the following hypotheses:

In the passive T-mixer, a sufficiently rapid micromixing process of feed and antisolvent stream is ensured for equal inlet stream velocities.

As antisolvent for continuous nucleation the same solvent as used for particle washing within the crystal process chain is suitable.

The continuously generated nuclei or the solid loading in the continuous nucleator can be estimated from the mixing point in the ternary solubility diagram.

Our work is divided into the following three parts: (1) design and characterization of the continuous in-situ nucleator for coupling with various continuous crystallizers answering the three above mentioned hypotheses, (2) continuous particle design considering nucleation and crystal growth by coupling the nucleator with the slug flow crystallizer (SFC) as crystal growth zone for particles with different aspect ratios ranging from nearly spherical to needle-shaped particles and (3) the demonstration of a full continuous end-to-end small-scale manufacturing process for crystalline particles consisting of the nucleator, the SFC as crystal growth zone, and the CVSF for product isolation.

6. Conclusions

Production in the pharmaceutical industry for a small-scale production (250 - 100 kg a-1) is undergoing a turnaround in terms of processing methods. Thus, more and more research is performed in the direction of continuous production, which, however, brings challenges on a small scale like this. There are already some concepts for continuous cooling crystallization and very few concepts for downstream, but there is still a lack of suitable methods to provide continuous nucleation and, thus, continuous in-situ seeds for crystallization. This leads to the fact that a long-term operation of a continuous production of crystalline products is not easily possible.

Our study follows this line of thought, introducing a novel continuous nucleator designed based on phase diagrams making use of antisolvent nucleation. The choice of antisolvent used for nucleation should ideally match the solvent used in the washing step. For rapid and precise creation of the nucleator on a small scale, meeting diverse requirements for nucleation and subsequent growth processes it is fabricated through fast 3D printing. The suitability of the nucleator for continuous, long-term operation in combination with various crystallizers was assessed to ensure an adequate number of nuclei for the subsequent growth process and substantial consumption of supersaturation, minimizing the risk of fouling in the crystallizer. The developed nucleator in form of a T-mixer could be implemented in front of various crystallizers. Here its implementation was shown for the slug flow crystallizer (SFC) with the aim of producing high-quality product particles. These results obtained using the coupled continuous nucleator and the SFC as growth zone are qualitatively comparable to the results of a batch cooling crystallization [

11] and the SFC crystallization from the literature [

11,

12], which, however, were carried out with the binary substance system

l-alanine/water. In this context, the concept of continuous

in-situ nucleation compared to seed crystal addition provides both a reduced time effort, since the production of seed crystals with high-quality specifications is not required, and the prevention of potential contamination due to the

in-situ production of nuclei.

Furthermore, with the connection to the continuous vacuum screw filter (CVSF) the fully continuous crystal process chain (CPC) up to free-flowing particles was completed and the experimental results demonstrate that the full-continuous end-to-end small-scale manufacturing of free-flowing particles is possible, achieving reproducibly high relative yields in the crystal growth process in the SFC of approximately 80 %, preserving the critical quality attributes (CQAs) during CVSF operation and ending up with residual moistures of around 3 % with the configuration used, despite a low, non-optimal filling degree of 5 % in the CVSF. The modular setup of the CVSF provides the option to extend the CVSF by a drying module in order to further reduce the residual moisture below 1 % and obtain dry, free-flowing particles at the end of the integrated process. Additionally, the CVSF offers the potential to realize higher filling degrees independent from the suspension volume flow rate and solid loading by increasing the shaft diameter of the screw. This will further improve the flexibility of the CVSF with regard to the compatibility to various types of continuous crystallizers and operation points. A summary of all results for nucleator characterization and coupling experiments are listed in

Table S3.

With respect to long-term operation, the processing time could be extended by implementing a cleaning-in-place (CIP) system when fouling is detected in the SFC. Moreover, the proof of concept experiments were performed with the model substance system l-alanine/water/ethanol, resulting in limited achievable yields and solid loadings in the SFC based on the solubility data. Consequently, the integrated process consisting of the T-mixer with 90° inlets configuration as continuous nucleator, the SFC for continuous crystallization and the CVSF for continuous product isolation must comprehensively investigated with respect to different substance systems and operating windows.

The end-to-end continuous small-scale manufacturing process for free-flowing crystalline particles investigated in this study shows that even at non-optimized conditions the concepts used enable fast production of high-quality crystalline particles, which is of high importance during the drug development phase especially for new drug substances.

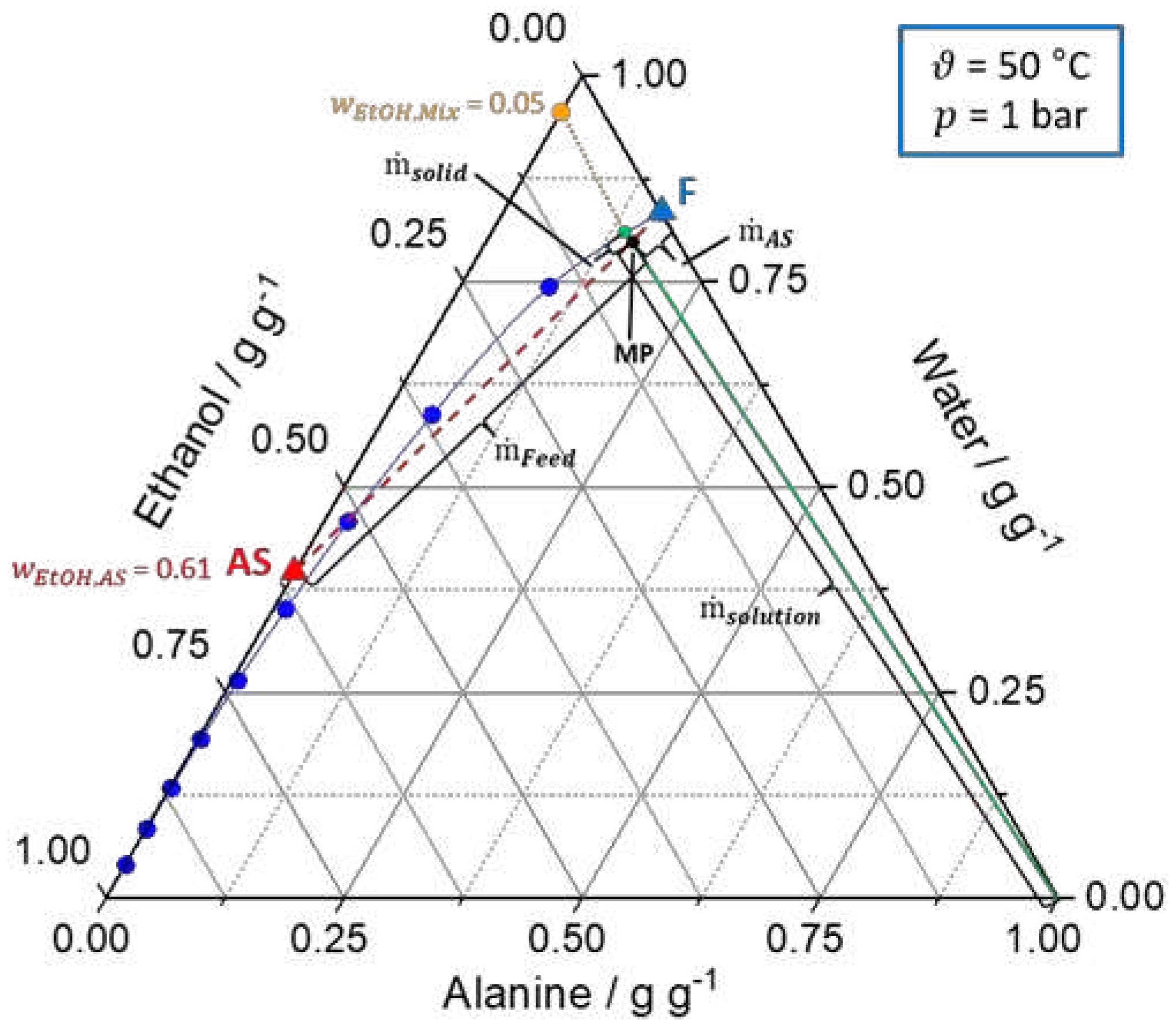

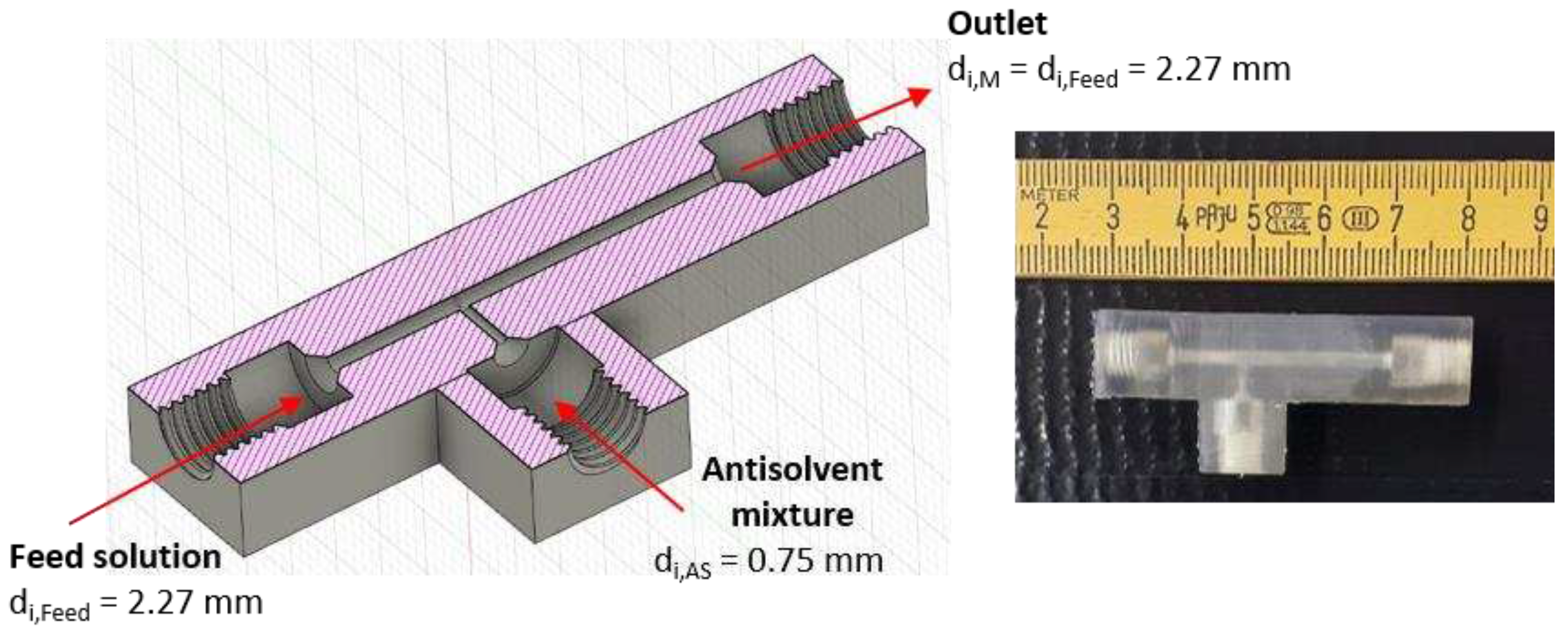

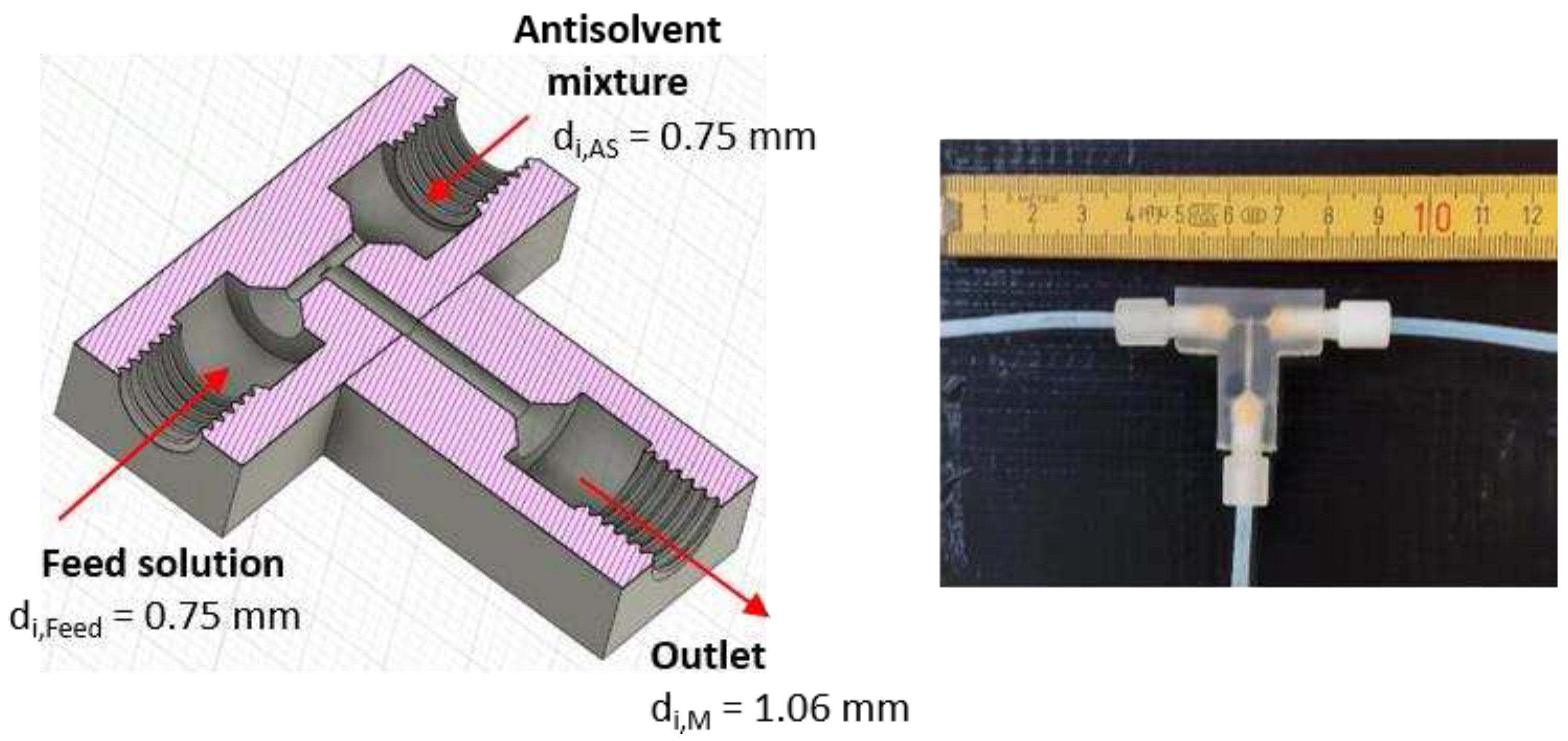

Figure 1.

Design of the T-mixer with 180° inlets as continuous nucleator: (left) Illustration of a cross-section created by the CAD software Fusion 360 with ID dimensions. (right) Photo of the 3D printed T-mixer.

Figure 1.

Design of the T-mixer with 180° inlets as continuous nucleator: (left) Illustration of a cross-section created by the CAD software Fusion 360 with ID dimensions. (right) Photo of the 3D printed T-mixer.

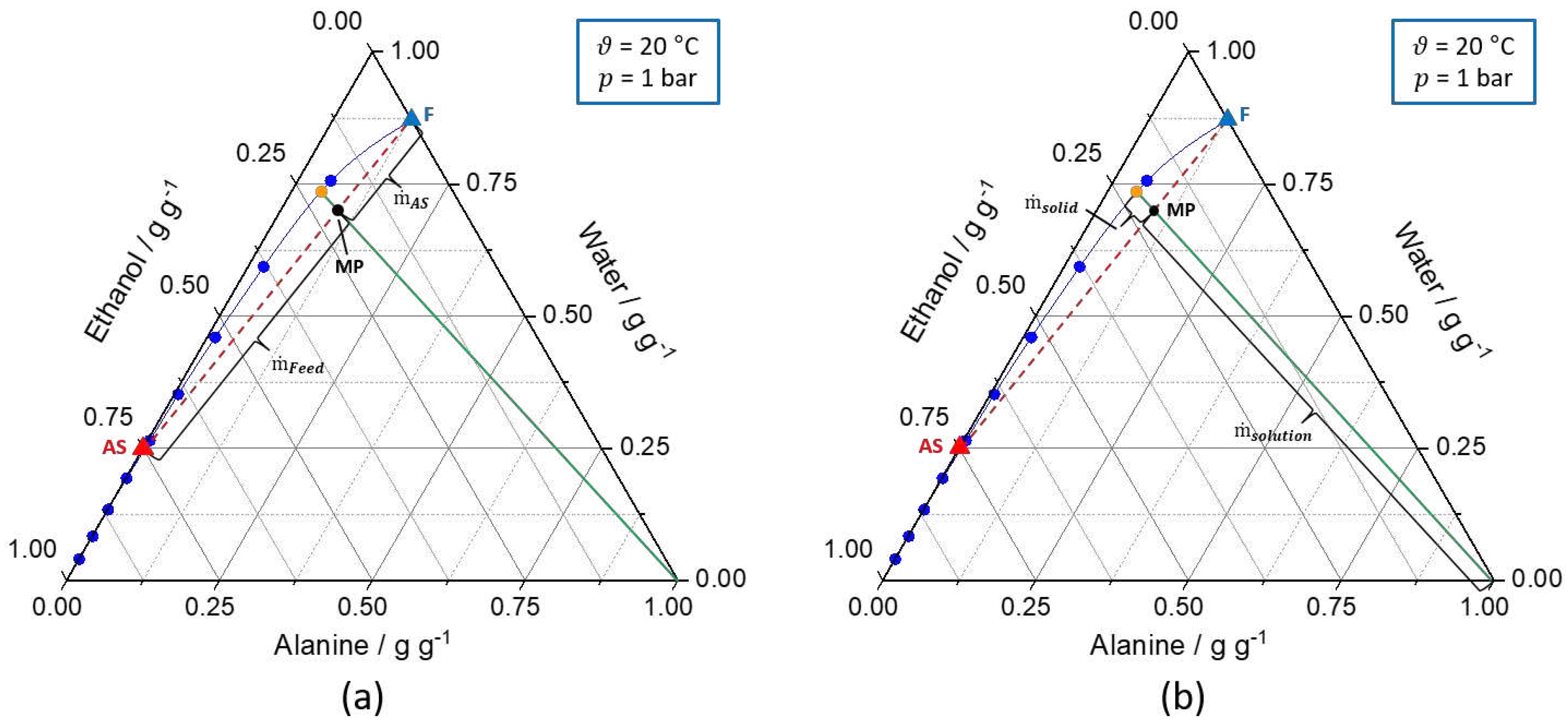

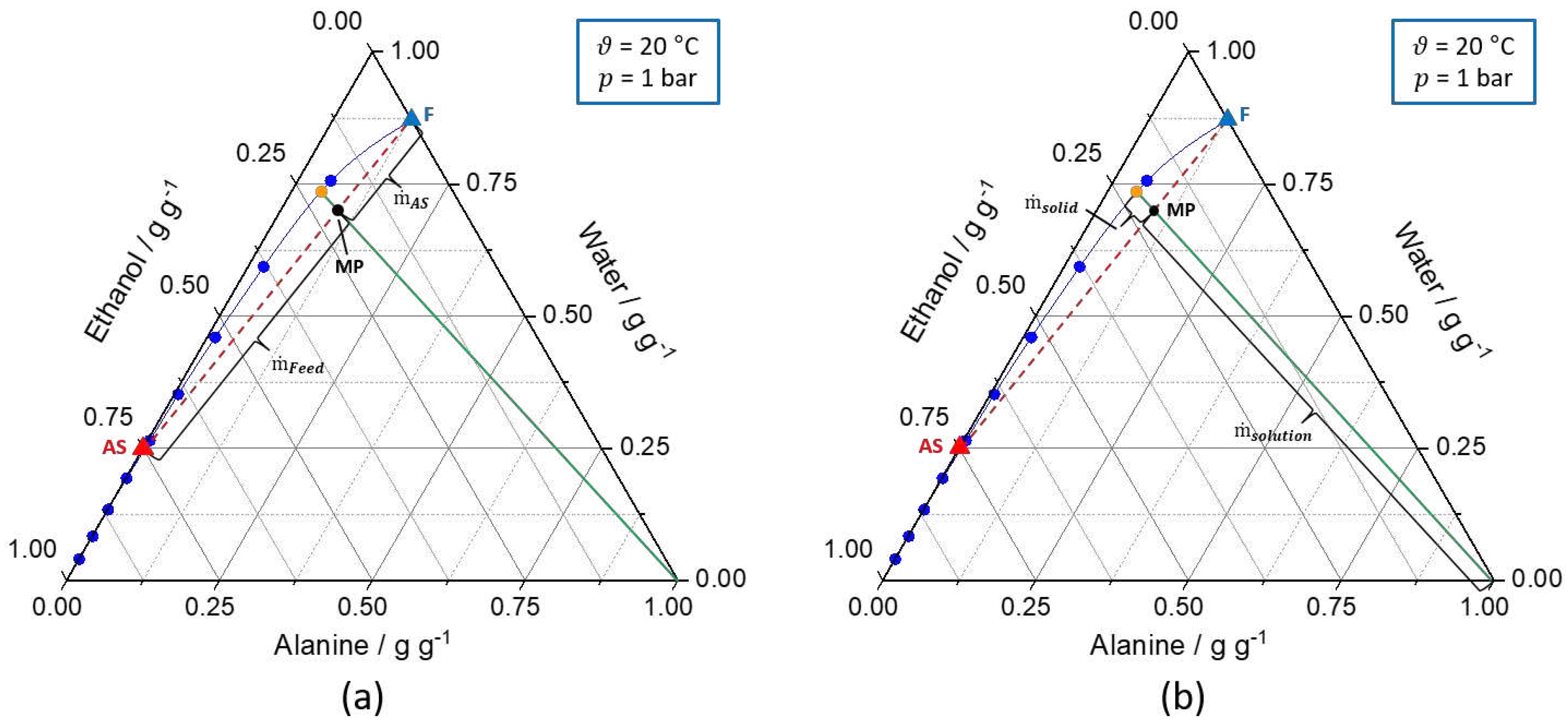

Figure 2.

Ternary solubility diagrams of

l-alanine/water/ethanol at 20 °C and 1 bar. The solid blue line represents the solubility curve based on the experimental data from

An et al. [

39]

. The solid green line describes the underlying conode for nucleation, respectively, crystallization process until thermodynamic equilibrium is reached. Additionally, the orange dot (

) indicates the composition of the liquid phase in the equilibrium state. Furthermore, the dashed red line connects the feed solution (F, blue triangle) and antisolvent mixture (AS, red triangle,

) to be mixed and the intersection between the dashed red line and the green line defines the mixing point (MP, black dot). (a) shows the calculation of the ratio of the feed and antisolvent mass flow rate based on the location of the MP on the conode by applying the lever rule (eq. (7) - (9)). (b) displays the calculation of

based on the location of the MP on the conode by using the lever rule (eq. (10)). Different operating points for the T-mixer with 180° inlets based on graphical construction are shown in

Table S1.

Figure 2.

Ternary solubility diagrams of

l-alanine/water/ethanol at 20 °C and 1 bar. The solid blue line represents the solubility curve based on the experimental data from

An et al. [

39]

. The solid green line describes the underlying conode for nucleation, respectively, crystallization process until thermodynamic equilibrium is reached. Additionally, the orange dot (

) indicates the composition of the liquid phase in the equilibrium state. Furthermore, the dashed red line connects the feed solution (F, blue triangle) and antisolvent mixture (AS, red triangle,

) to be mixed and the intersection between the dashed red line and the green line defines the mixing point (MP, black dot). (a) shows the calculation of the ratio of the feed and antisolvent mass flow rate based on the location of the MP on the conode by applying the lever rule (eq. (7) - (9)). (b) displays the calculation of

based on the location of the MP on the conode by using the lever rule (eq. (10)). Different operating points for the T-mixer with 180° inlets based on graphical construction are shown in

Table S1.

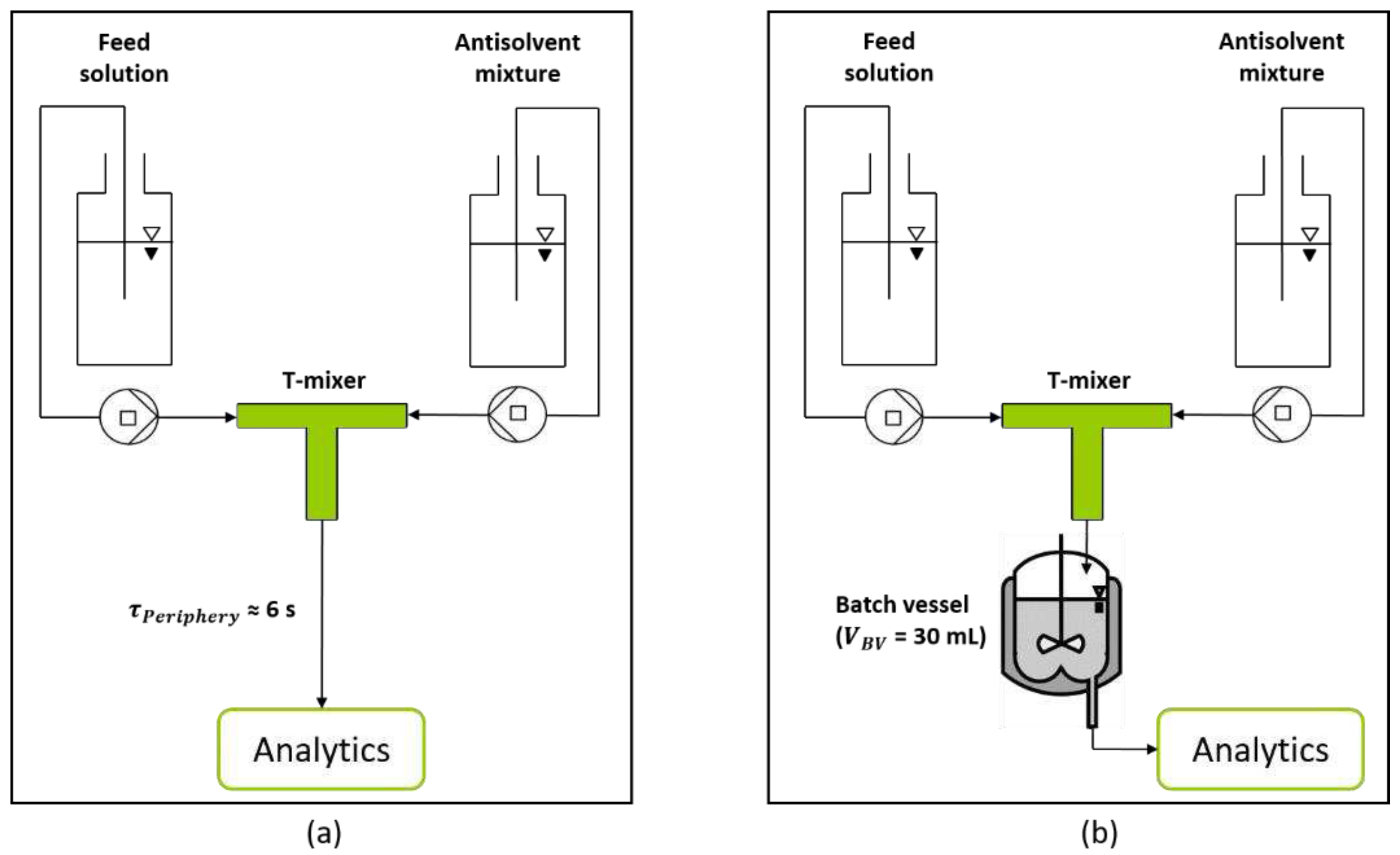

Figure 3.

Schematic experimental setup for the characterization of the T-mixer with 180° inlet configuration as continuous nucleator. (a) Experimental setup for the analysis of generated nuclei after a short RT of 6 s provided by the periphery. (b) Extended setup by a batch vessel, enabling the adjustment of specific RTs (5 min, 10 min, and 15 min).

Figure 3.

Schematic experimental setup for the characterization of the T-mixer with 180° inlet configuration as continuous nucleator. (a) Experimental setup for the analysis of generated nuclei after a short RT of 6 s provided by the periphery. (b) Extended setup by a batch vessel, enabling the adjustment of specific RTs (5 min, 10 min, and 15 min).

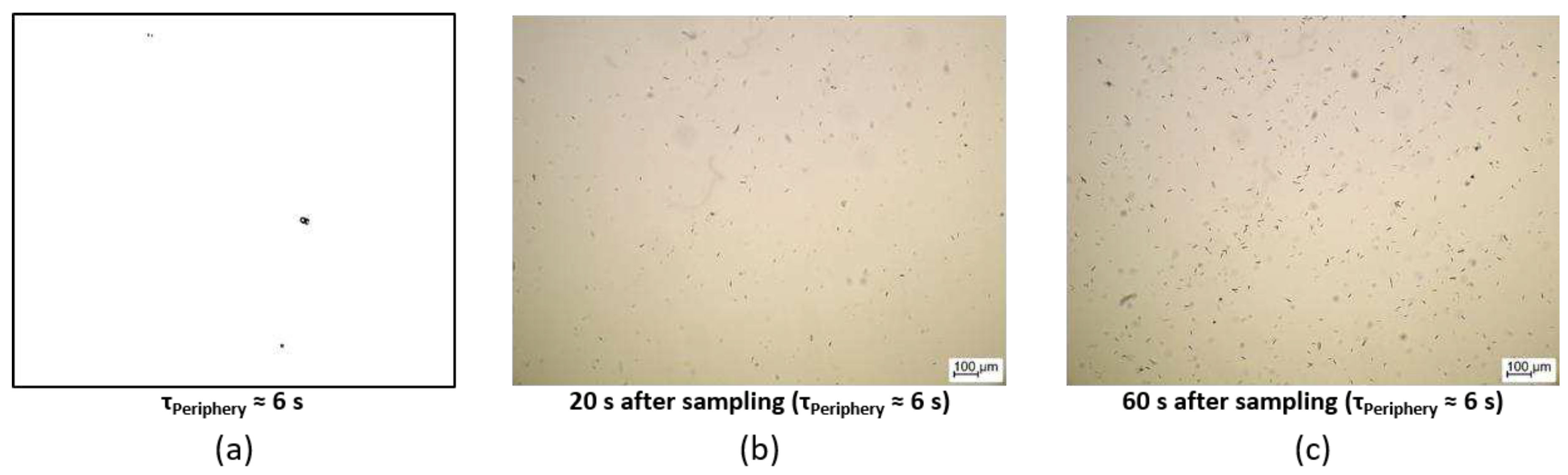

Figure 4.

(a) displays a screenshot from the in-line DIA. Additionally, light microscopic images of the same sample after a RT of approximately 6 s provided by the periphery taken 20 s (b) and 60 s (c) after sampling are shown.

Figure 4.

(a) displays a screenshot from the in-line DIA. Additionally, light microscopic images of the same sample after a RT of approximately 6 s provided by the periphery taken 20 s (b) and 60 s (c) after sampling are shown.

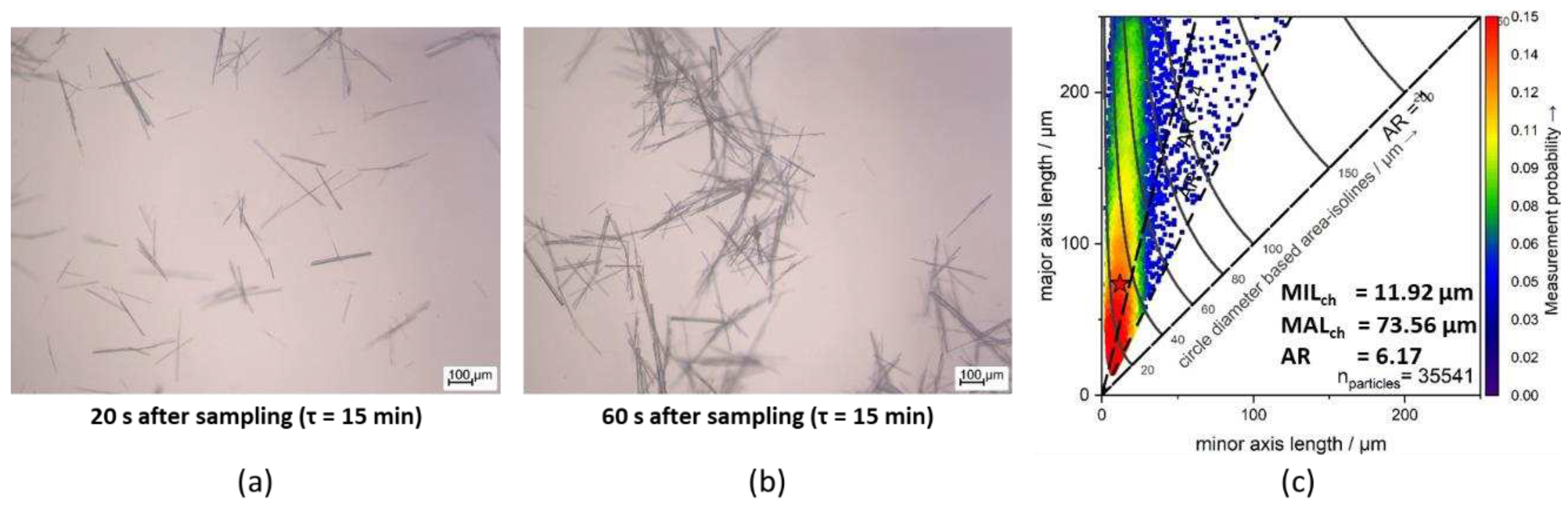

Figure 5.

Light microscopic images of the same sample after a RT of 15 min in the batch vessel 20 s (a) and 60 s (b) after sampling. (c) ALD of anisotropic particles after 15 min inside the batch vessel. The data points are plotted as a function of MIL, MAL, AR, and measurement probability. The red star indicates the centroid of the data points and, thus, the most probable projection area to be measured, characterized by MILch, MALch, and AR.

Figure 5.

Light microscopic images of the same sample after a RT of 15 min in the batch vessel 20 s (a) and 60 s (b) after sampling. (c) ALD of anisotropic particles after 15 min inside the batch vessel. The data points are plotted as a function of MIL, MAL, AR, and measurement probability. The red star indicates the centroid of the data points and, thus, the most probable projection area to be measured, characterized by MILch, MALch, and AR.

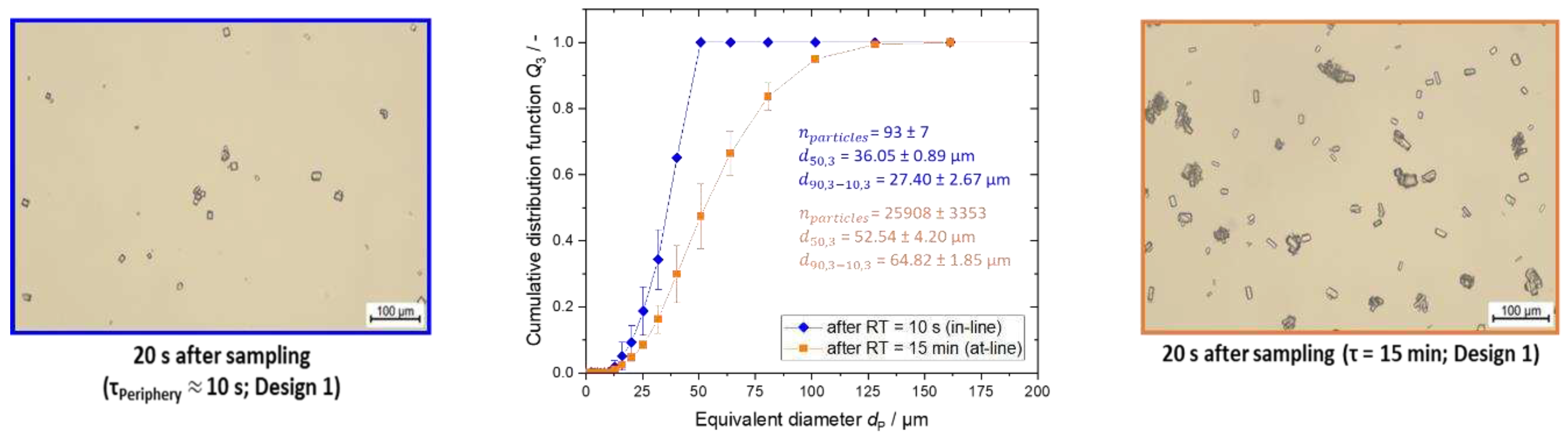

Figure 8.

Microscopic images and the respective PSD for the characterization experiments for the T-mixer with 90° inlets in blue after a RT of approximately 10 s (in-line) and in orange after RT of 15 min (at-line). The PSD measurements were conducted twice.

Figure 8.

Microscopic images and the respective PSD for the characterization experiments for the T-mixer with 90° inlets in blue after a RT of approximately 10 s (in-line) and in orange after RT of 15 min (at-line). The PSD measurements were conducted twice.

Figure 9.

Schematic experimental setup of the nucleator coupled with the SFC.

Figure 9.

Schematic experimental setup of the nucleator coupled with the SFC.

Figure 10.

Microscopic images (top) and pictures of slug flow with suspended particles taken at the end of the SFC (bottom) for inhomogeneous (left, black, OP1) and homogeneous (right, green, OP2) suspension state during the crystallization process inside the SFC.

Figure 10.

Microscopic images (top) and pictures of slug flow with suspended particles taken at the end of the SFC (bottom) for inhomogeneous (left, black, OP1) and homogeneous (right, green, OP2) suspension state during the crystallization process inside the SFC.

Figure 11.

Microscopic image (top) and picture of slug flow taken at the end of the SFC (bottom) at

of 34.75 °C. Addition of

l-glutamic acid for the operation with the process parameters of OP2 (

Table 2).

Figure 11.

Microscopic image (top) and picture of slug flow taken at the end of the SFC (bottom) at

of 34.75 °C. Addition of

l-glutamic acid for the operation with the process parameters of OP2 (

Table 2).

Figure 12.

Schematic experimental setup for end-to-end continuous small-scale manufacturing of free-flowing particles containing a continuous nucleator (T-mixer with 90° inlet configuration) in stage 1, continuous crystallization (SFC) in stage 2 and continuous particle isolation consisting of filtration and two-stage washing (CVSF) as well as a heater between SFC and CVSF in stage 3.

Figure 12.

Schematic experimental setup for end-to-end continuous small-scale manufacturing of free-flowing particles containing a continuous nucleator (T-mixer with 90° inlet configuration) in stage 1, continuous crystallization (SFC) in stage 2 and continuous particle isolation consisting of filtration and two-stage washing (CVSF) as well as a heater between SFC and CVSF in stage 3.

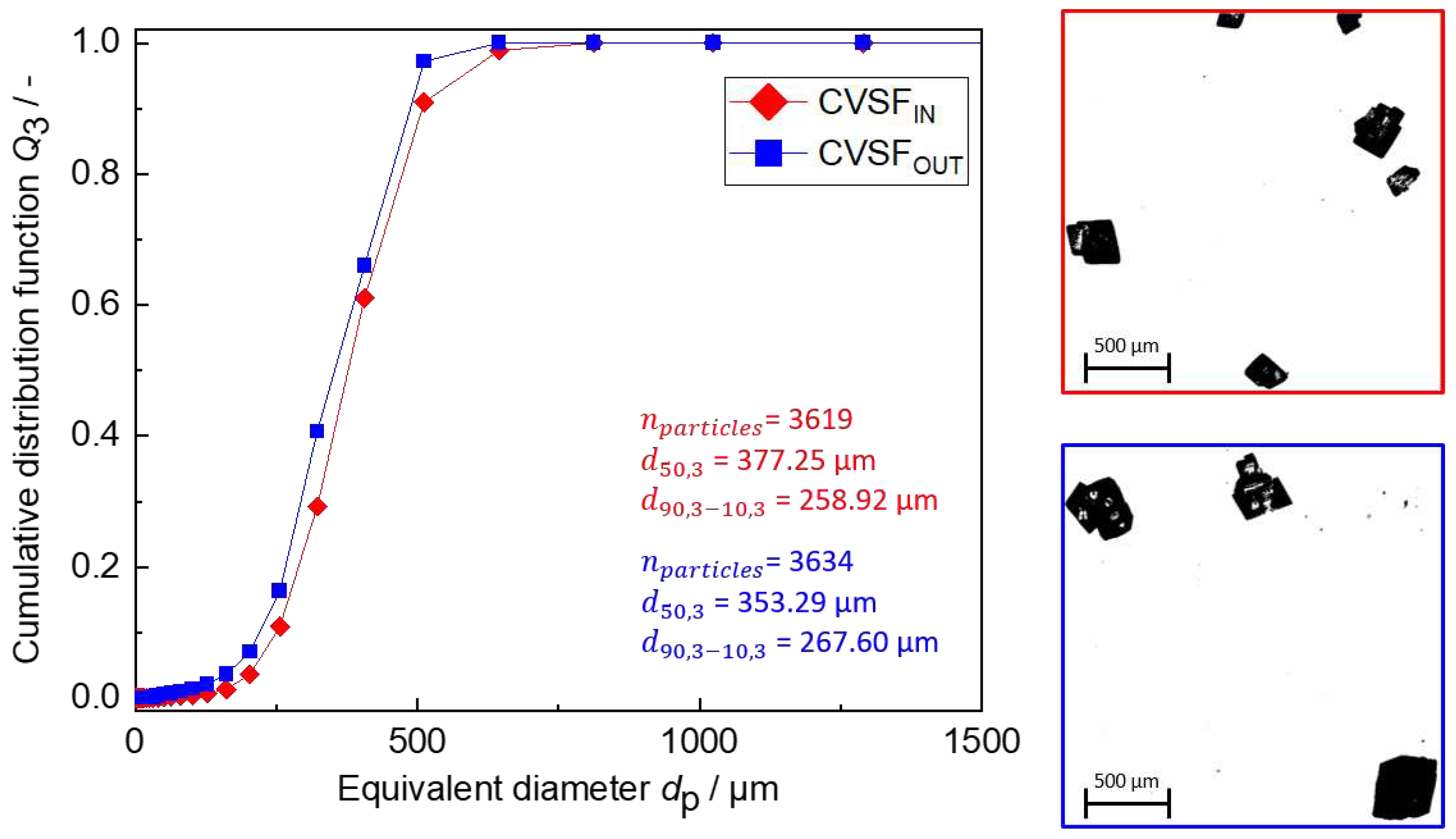

Figure 13.

Results at the inlet and outlet of the CVSF. (left) The PSDs of the product particles at the inlet (CVSFIN, red) and outlet (CVSFOUT, blue) of the CVSF. (right) Exemplary DIA binary images of particles at the inlet (top, red) and outlet (bottom, blue).

Figure 13.

Results at the inlet and outlet of the CVSF. (left) The PSDs of the product particles at the inlet (CVSFIN, red) and outlet (CVSFOUT, blue) of the CVSF. (right) Exemplary DIA binary images of particles at the inlet (top, red) and outlet (bottom, blue).

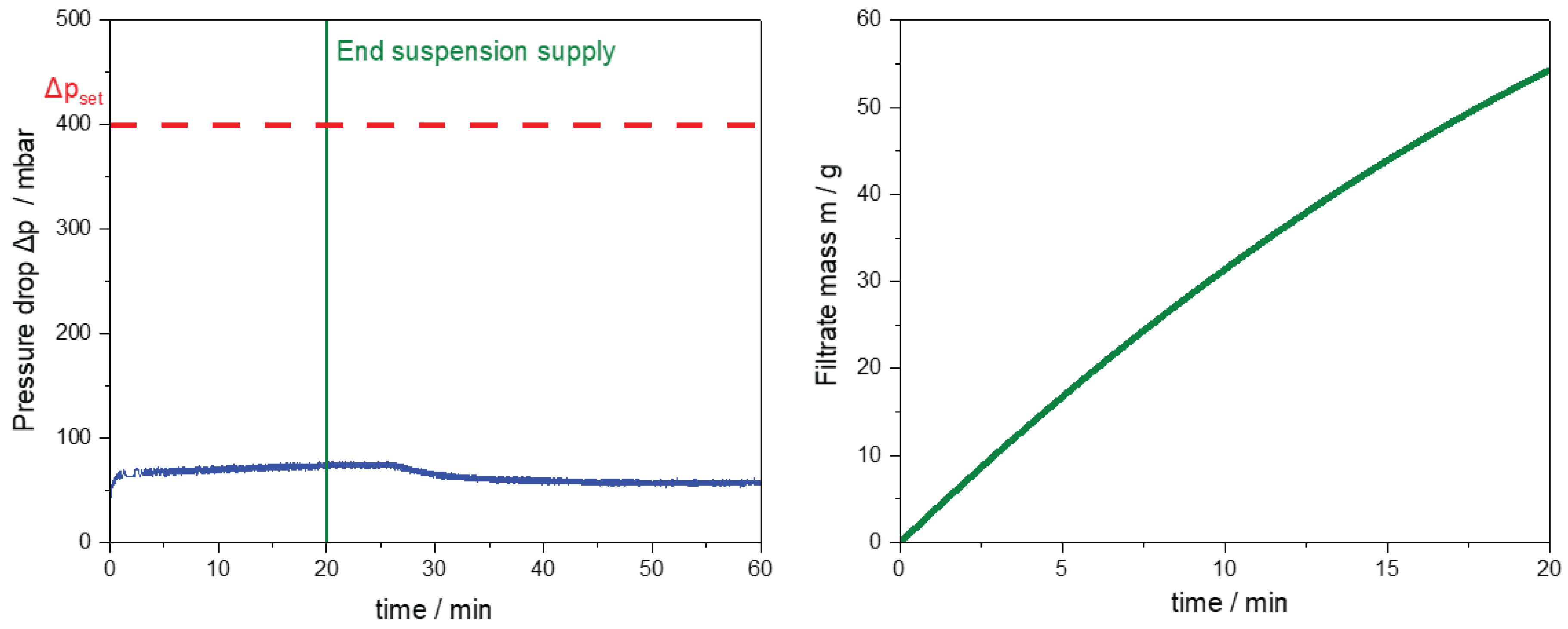

Figure 14.

Results of the filtration module during CVSF operation. (left) Pressure drop of the vacuum pump over the process time (blue line). The vertical green line indicates the end of the suspension supply from the SFC. The horizontal dotted red line represents the set pressure drop . (right) Filtrate mass over the process time until the end of the suspension supply into the CVSF.

Figure 14.

Results of the filtration module during CVSF operation. (left) Pressure drop of the vacuum pump over the process time (blue line). The vertical green line indicates the end of the suspension supply from the SFC. The horizontal dotted red line represents the set pressure drop . (right) Filtrate mass over the process time until the end of the suspension supply into the CVSF.

Table 1.

Graphically determined process parameters and resulting design parameters of T-mixers with 90° inlets and equal velocities at the mixing point, providing of 5 wt.-%.

Table 1.

Graphically determined process parameters and resulting design parameters of T-mixers with 90° inlets and equal velocities at the mixing point, providing of 5 wt.-%.

| Design |

1 |

2 |

| T-mixer configuration |

90° |

90° |

|

/ °C

|

20 |

50 |

|

/ mm |

0.75 |

0.75 |

|

/ mm |

2.61 |

2.27 |

|

/ mm |

2.61 |

2.27 |

|

/ wt.-% |

5 |

5 |

|

/ wt.-% |

1 |

1 |

|

/ mL min-1

|

10 |

10 |

|

/ mL min-1

|

0.83 |

1.10 |

|

/ wt.-% |

72 |

61 |

|

/ - |

88 |

190 |

Table 2.

Experimental and resulting parameters for a T-mixer with 90° inlets ( = 5 wt.-%, Design 2) as continuous nucleator coupled with the SFC ( = 26.54 m) for two different operating points (OP1 and OP2). The experiments for OP1 and OP2 were performed three and two times, respectively.

Table 2.

Experimental and resulting parameters for a T-mixer with 90° inlets ( = 5 wt.-%, Design 2) as continuous nucleator coupled with the SFC ( = 26.54 m) for two different operating points (OP1 and OP2). The experiments for OP1 and OP2 were performed three and two times, respectively.

| Parameters |

OP1 |

OP2 |

|

/ mL min-1

|

5.55 |

11.09 |

|

/ - |

0.43 ± 0.03 |

0.41 ± 0.01 |

|

/ min |

16.44 ± 1.21 |

7.74 ± 0.13 |

|

/ °C |

50.35 ± 0.11 |

49.46 ± 0.01 |

|

/ °C |

25.64 ± 0.41 |

34.75 ± 0.08 |

|

/ K min-1

|

1.51 ± 0.09 |

1.90 ± 0.02 |

Table 3.

Experimental results for the crystallization processes using process parametes given in

Table 2.

Table 3.

Experimental results for the crystallization processes using process parametes given in

Table 2.

| Parameters |

OP1 |

OP2 |

|

/ % |

81.52 ± 3.61 |

65.65 ± 2.07 |

|

/ - |

494 ± 248 |

n.a. * |

|

/ µm |

484.14 ± 54.60 |

n.a. * |

|

/ µm |

530.47 ± 50.21 |

n.a. * |

Table 4.

Experimental process and resulting parameters for the integrated process consisting of coupled nucleator, SFC, heater and CVSF based on triple experiments.

Table 4.

Experimental process and resulting parameters for the integrated process consisting of coupled nucleator, SFC, heater and CVSF based on triple experiments.

| |

Parameters |

Value |

| T-mixer (90° inlets) |

/ mL min-1

|

5.55 |

|

/ mL min-1

|

5 |

|

/ mL min-1

|

0.55 |

|

/ wt.-% |

61 |

|

/ wt.-% |

5 |

| SFC |

/ mL min-1

|

5.55 |

|

/ - |

0.44 ± 0.00 |

|

/ min |

16.72 ± 0.04 |

|

/ °C |

48.89 ± 0.24 |

|

/ °C |

23.63 ± 0.19 |

|

/ K min-1

|

1.51 ± 0.03 |

|

/ wt.-% |

2.73 ± 0.56 |

| Heater |

/ °C |

51 |

|

/ °C |

31 |

| CVSF |

/ rpm |

1 |

|

/ mbar |

400 |

|

/ mL min-1

|

15 |

|

/ % |

5 |

|

/ min |

32 |