Submitted:

09 December 2024

Posted:

10 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

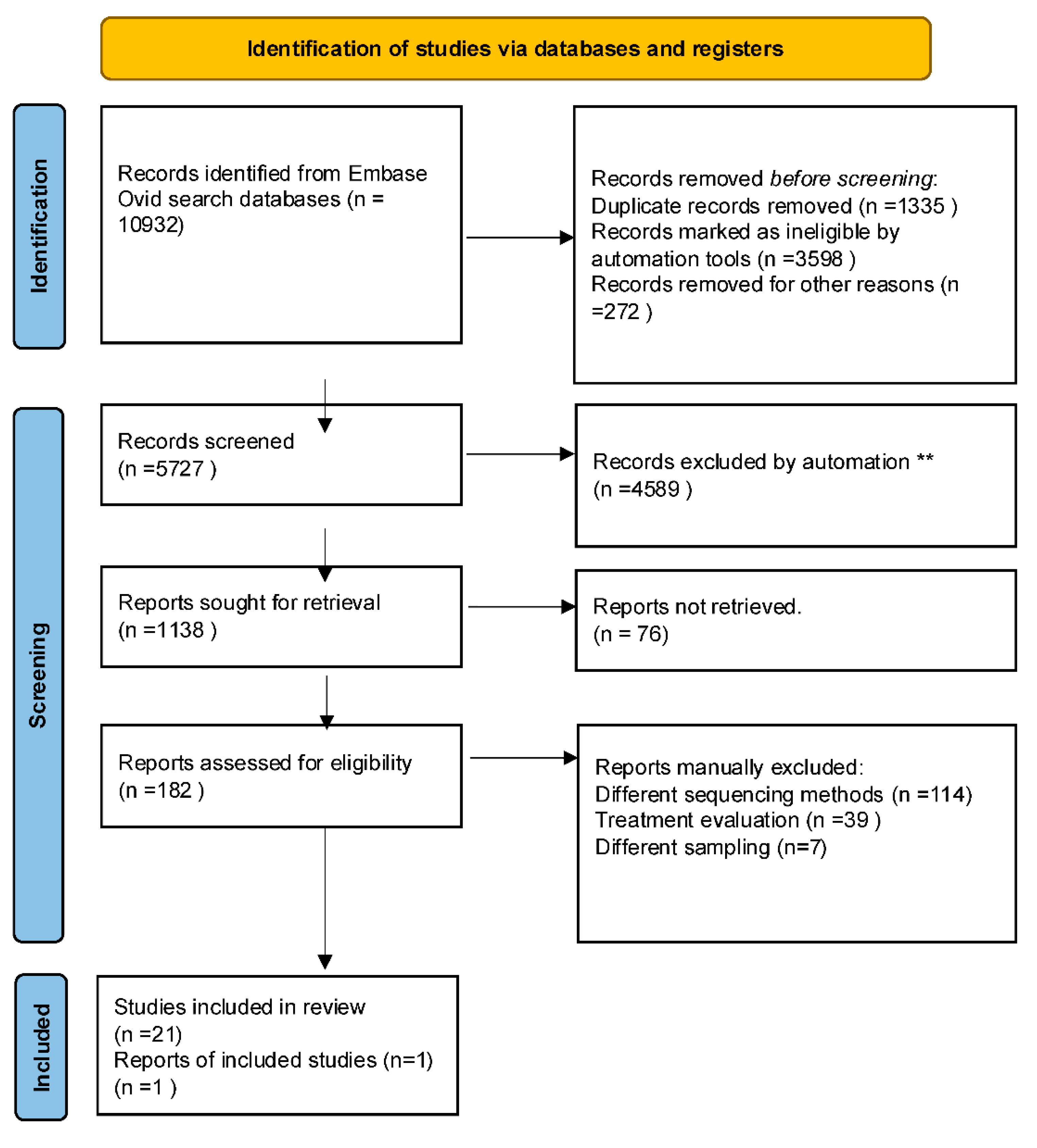

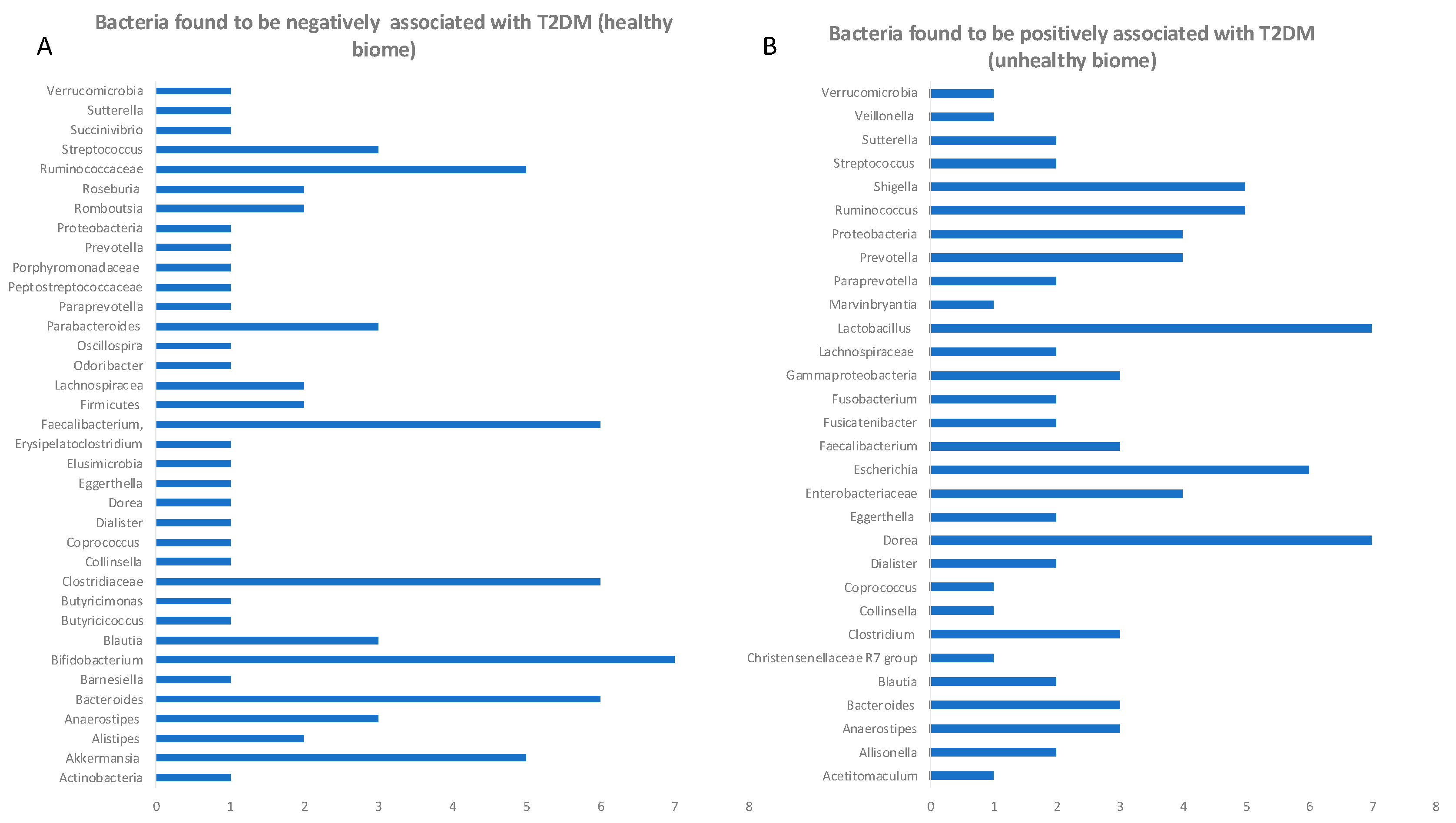

The rising burden of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a growing global public health problem, particularly prominent in developing countries. Early detection of T2DM and prediabetes is vital for reversing the outcome of disease, allowing early intervention. In the past decade various mi-crobiome-metabolome studies attempted to address the question whether there are any common microbial patterns which would indicate either prediabetic or diabetic gut microbial signatures. Because current studies have a high methodological heterogeneity and risk of bias, we have se-lected studies which adhered to similar design and methodology. We have performed a system-atic review to assess if there are any common changes in microbiome belonging to diabetic, pre-diabetic and healthy individuals. The presented here cross-sectional studies collectively covered a population of 65754 people, with 1800 in 2TD group, 2770 in prediabetic group and 61184 in control group. The overall microbial diversity scores were lower in T2D and prediabetes cohort in 86% of analysed herein studies. Re-programming microbiome is potentially one of the safest and long-lasting ways to eliminate diabetes in its early stages. The differences in abundance of certain microbial species could serve as an early warning for a dysbiotic gut environment and could be easily modified before the onset of disease by changes in lifestyle, through taking probi-otics, introducing diet modifications, or stimulating vagal nerve. This review shows how meta-genomic studies already had and will continue uncovering novel therapeutic targets (probiotics, prebiotics or targets for elimination from flora). This work clearly shows that gut microbiome intervention studies, if performed according to standard operating protocols using predefined analytic framework (e.g. STORMS), could be combined with other similar studies allowing broader conclusions from collating all global cohort studies efforts and eliminating the effect-size statistical insufficiency of a single study.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Gut Microbiome and Hyperglycaemia

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khan, M.A.B.; Hashim, M.J.; King, J.K.; Govender, R.D.; Mustafa, H.; Al Kaabi, J. Epidemiology of Type 2 Diabetes - Global Burden of Disease and Forecasted Trends. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2020, 10, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rooney, M.R.; Fang, M.; Ogurtsova, K.; Ozkan, B.; Echouffo-Tcheugui, J.B.; Boyko, E.J.; Magliano, D.J.; Selvin, E. Global Prevalence of Prediabetes. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, 1388–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Ghani, M.; DeFronzo, R.A. Is It Time to Change the Type 2 Diabetes Treatment Paradigm? Yes! GLP-1 RAs Should Replace Metformin in the Type 2 Diabetes Algorithm. Diabetes Care 2017, 40, 1121–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bednarska, N.G. Critical Assessment of Current Health Policies Used for Managing Diabetes in the United Kingdom. J Community Med Public Heal. 2022, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allin, K.H.; Tremaroli, V.; Caesar, R.; Jensen, B.A.H.; Damgaard, M.T.F.; Bahl, M.I.; Licht, T.R.; Hansen, T.H.; Nielsen, T.; Dantoft, T.M.; et al. Aberrant intestinal microbiota in individuals with prediabetes. Diabetologia 2018, 61, 810–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomasello, G.; Mazzola, M.; Jurjus, A.; Cappello, F.; Carini, F.; Damiani, P.; Gerges Geagea, A.; Zeenny, M.N.; Leone, A. The fingerprint of the human gastrointestinal tract microbiota: a hypothesis of molecular mapping. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2017, 31, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Iebba, V.; Totino, V.; Gagliardi, A.; Santangelo, F.; Cacciotti, F.; Trancassini, M.; Mancini, C.; Cicerone, C.; Corazziari, E.; Pantanella, F.; et al. Eubiosis and dysbiosis: the two sides of the microbiota. New Microbiol. 2016, 39, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Visconti, A.; Le Roy, C.I.; Rosa, F.; Rossi, N.; Martin, T.C.; Mohney, R.P.; Li, W.; de Rinaldis, E.; Bell, J.T.; Venter, J.C.; et al. Interplay between the human gut microbiome and host metabolism. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, Y.P.; Bernardi, A.; Frozza, R.L. The Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids From Gut Microbiota in Gut-Brain Communication. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2020, 11, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmnäs-Bédard, M.S.A.; Costabile, G.; Vetrani, C.; Åberg, S.; Hjalmarsson, Y.; Dicksved, J.; Riccardi, G.; Landberg, R. The human gut microbiota and glucose metabolism: a scoping review of key bacteria and the potential role of SCFAs. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 116, 862–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, K.; Wu, Z.-X.; Chen, X.-Y.; Wang, J.-Q.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, C.; Zhu, D.; Koya, J.B.; Wei, L.; Li, J.; et al. Microbiota in health and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barra, N.G.; Anhê, F.F.; Cavallari, J.F.; Singh, A.M.; Chan, D.Y.; Schertzer, J.D. Micronutrients impact the gut microbiota and blood glucose. J. Endocrinol. 2021, 250, R1–R21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, W.-L.; Chen, Y.-E.; Tseng, H.-T.; Cheng, C.-F.; Wu, J.-H.; Hou, Y.-C. Gut Microbiota in Patients with Prediabetes. Nutrients 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiefer, M.M.; Silverman, J.B.; Young, B.A.; Nelson, K.M. National patterns in diabetes screening: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2005-2012. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2015, 30, 612–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Ren, H.; Lu, Y.; Fang, C.; Hou, G.; Yang, Z.; Chen, B.; Yang, F.; Zhao, Y.; Shi, Z.; et al. Distinct gut metagenomics and metaproteomics signatures in prediabetics and treatment-naïve type 2 diabetics. EBioMedicine 2019, 47, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, J.; Ramesh, G.; Wu, M.; Jensen, E.T.; Crago, O.; Bertoni, A.G.; Gao, C.; Hoffman, K.L.; Sheridan, P.A.; Wong, K.E.; et al. Butyrate-Producing Bacteria and Insulin Homeostasis: The Microbiome and Insulin Longitudinal Evaluation Study (MILES). Diabetes 2022, 71, 2438–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canani, R.B.; Costanzo, M. Di; Leone, L.; Pedata, M.; Meli, R.; Calignano, A. Potential beneficial effects of butyrate in intestinal and extraintestinal diseases. World J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 17, 1519–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, C.-Y.; Khachatryan, L.G.; Younis, N.K.; Mustafa, M.A.; Ahmad, N.; Athab, Z.H.; Polyanskaya, A. V; Kasanave, E.V.; Mirzaei, R.; Karampoor, S. Microbiota-derived short chain fatty acids in pediatric health and diseases: from gut development to neuroprotection. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1456793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunzelmann, K.; Mall, M. Electrolyte transport in the mammalian colon: mechanisms and implications for disease. Physiol. Rev. 2002, 82, 245–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangipurapu, J.; Stancáková, A.; Smith, U.; Kuusisto, J.; Laakso, M. Nine Amino Acids Are Associated With Decreased Insulin Secretion and Elevated Glucose Levels in a 7.4-Year Follow-up Study of 5,181 Finnish Men. Diabetes 2019, 68, 1353–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Q.; Li, J.; Yu, B.; Moon, J.-Y.; Chai, J.C.; Merino, J.; Hu, J.; Ruiz-Canela, M.; Rebholz, C.; Wang, Z.; et al. Host and gut microbial tryptophan metabolism and type 2 diabetes: an integrative analysis of host genetics, diet, gut microbiome and circulating metabolites in cohort studies. Gut 2022, 71, 1095–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, C.; Reyes-Escogido, M. de L.; Jimenez-Ceja, L.M.; Matus, M.; Gomez-Navarro, C.M.; Chu, N.D.; Zhong, V.; Tejero, M.E.; Alm, E.; Resendis-Antonio, O.; et al. Progressive Shifts in the Gut Microbiome Reflect Prediabetes and Diabetes Development in a Treatment-Naive Mexican Cohort. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruuskanen, M.O.; Erawijantari, P.P.; Havulinna, A.S.; Liu, Y.; Méric, G.; Tuomilehto, J.; Inouye, M.; Jousilahti, P.; Salomaa, V.; Jain, M.; et al. Gut Microbiome Composition Is Predictive of Incident Type 2 Diabetes in a Population Cohort of 5,572 Finnish Adults. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, N.; Dimitrova, N.; Ho, C.H.; Torres, P.J.; Camacho, F.R.; Cai, Y.; Vuyisich, M.; Tanton, D.; Banavar, G. Gut microbiome activity predicts risk of type 2 diabetes and metformin control in a large human cohort. medRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, F.H.; Tremaroli, V.; Nookaew, I.; Bergström, G.; Behre, C.J.; Fagerberg, B.; Nielsen, J.; Bäckhed, F. Gut metagenome in European women with normal, impaired and diabetic glucose control. Nature 2013, 498, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokol, H.; Pigneur, B.; Watterlot, L.; Lakhdari, O.; Bermúdez-Humarán, L.G.; Gratadoux, J.-J.; Blugeon, S.; Bridonneau, C.; Furet, J.-P.; Corthier, G.; et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of Crohn disease patientsfile:///Users/natalia/Downloads/PMC8677946.nbib. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008, 105, 16731–16736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakamoto, M.; Sakurai, N.; Tanno, H.; Iino, T.; Ohkuma, M.; Endo, A. Genome-based, phenotypic and chemotaxonomic classification of Faecalibacterium strains: proposal of three novel species Faecalibacterium duncaniae sp. nov., Faecalibacterium hattorii sp. nov. and Faecalibacterium gallinarum sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2022, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maioli, T.U.; Borras-Nogues, E.; Torres, L.; Barbosa, S.C.; Martins, V.D.; Langella, P.; Azevedo, V.A.; Chatel, J.-M. Possible Benefits of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii for Obesity-Associated Gut Disorders. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 740636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, M.; Li, Z.; You, H.; Rodrigues, R.; Jump, D.B.; Morgun, A.; Shulzhenko, N. Role of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes pathophysiology. EBioMedicine 2020, 51, 102590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vos, W.M.; Tilg, H.; Van Hul, M.; Cani, P.D. Gut microbiome and health: mechanistic insights. Gut 2022, 71, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louis, P.; Flint, H.J. Formation of propionate and butyrate by the human colonic microbiota. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 19, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremaroli, V.; Bäckhed, F. Functional interactions between the gut microbiota and host metabolism. Nature 2012, 489, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Zhu, Y.; Hyun, N.; Zeng, D.; Uppal, K.; Tran, V.T.; Yu, T.; Jones, D.; He, J.; Lee, E.T.; et al. Novel Metabolic Markers for the Risk of Diabetes Development in American Indians. Diabetes Care 2014, 38, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Chang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Chen, H.; Tao, S.; Zhang, Z. Implication of the gut microbiome composition of type 2 diabetic patients from northern China. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, N.-R.; Lee, J.-C.; Lee, H.-Y.; Kim, M.-S.; Whon, T.W.; Lee, M.-S.; Bae, J.-W. An increase in the Akkermansia spp. population induced by metformin treatment improves glucose homeostasis in diet-induced obese mice. Gut 2014, 63, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everard, A.; Belzer, C.; Geurts, L.; Ouwerkerk, J.P.; Druart, C.; Bindels, L.B.; Guiot, Y.; Derrien, M.; Muccioli, G.G.; Delzenne, N.M.; et al. Cross-talk between Akkermansia muciniphila and intestinal epithelium controls diet-induced obesity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110, 9066–9071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohr, A.E.; Jäger, R.; Carpenter, K.C.; Kerksick, C.M.; Purpura, M.; Townsend, J.R.; West, N.P.; Black, K.; Gleeson, M.; Pyne, D.B.; et al. The athletic gut microbiota. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2020, 17, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raftar, S.K.A.; Ashrafian, F.; Abdollahiyan, S.; Yadegar, A.; Moradi, H.R.; Masoumi, M.; Vaziri, F.; Moshiri, A.; Siadat, S.D.; Zali, M.R. The anti-inflammatory effects of Akkermansia muciniphila and its derivates in HFD/CCL4-induced murine model of liver injury. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, S.F.; Murphy, E.F.; O’Sullivan, O.; Lucey, A.J.; Humphreys, M.; Hogan, A.; Hayes, P.; O’Reilly, M.; Jeffery, I.B.; Wood-Martin, R.; et al. Exercise and associated dietary extremes impact on gut microbial diversity. Gut 2014, 63, 1913–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Q.; Gao, Z.; Zhao, L.; Wang, H.; Luo, Z.; Vandeputte, D.; He, L.; Li, M.; Di, S.; Liu, Y.; et al. Multiomics Analyses With Stool-Type Stratification in Patient Cohorts and Blautia Identification as a Potential Bacterial Modulator in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes 2024, 73, 511–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, J.; Wu, F.; Li, X.; Wu, D.; Zhang, M.; Ou, Z.; Jie, Z.; Yan, Q.; et al. Genome sequencing of 39 Akkermansia muciniphila isolates reveals its population structure, genomic and functional diverisity, and global distribution in mammalian gut microbiotas. BMC Genomics 2017, 18, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Genome-Phenome Archive. Available online: https://ega-archive.org/studies/EGAS50000000198) (accessed on Dec 8, 2024).

- Vals-Delgado, C.; Alcala-Diaz, J.F.; Molina-Abril, H.; Roncero-Ramos, I.; Caspers, M.P.M.; Schuren, F.H.J.; Van den Broek, T.J.; Luque, R.; Perez-Martinez, P.; Katsiki, N.; et al. An altered microbiota pattern precedes Type 2 diabetes mellitus development: From the CORDIOPREV study. J. Adv. Res. 2022, 35, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, A.; Yang, W.; Chen, G.; Shafiq, M.; Javed, S.; Ali Zaidi, S.S.; Shahid, R.; Liu, C.; Bokhari, H. Analysis of gut microbiota of obese individuals with type 2 diabetes and healthy individuals. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0226372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Luo, X.; Mao, X.; Tao, Y.; Ran, X.; Zhao, H.; Xiong, J.; Li, L. Gut microbiome analysis of type 2 diabetic patients from the Chinese minority ethnic groups the Uygurs and Kazaks. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0172774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrizales-Sánchez, A.K.; Tamez-Rivera, O.; Rodríguez-Gutiérrez, N.A.; Elizondo-Montemayor, L.; Gradilla-Hernández, M.S.; García-Rivas, G.; Pacheco, A.; Senés-Guerrero, C. Characterization of gut microbiota associated with metabolic syndrome and type-2 diabetes mellitus in Mexican pediatric subjects. BMC Pediatr. 2023, 23, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwan, S.-Y.; Sabotta, C.M.; Joon, A.; Wei, P.; Petty, L.E.; Below, J.E.; Wu, X.; Zhang, J.; Jenq, R.R.; Hawk, E.T.; et al. Gut Microbiome Alterations Associated with Diabetes in Mexican Americans in South Texas. mSystems 2022, 7, e0003322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, N.; Vogensen, F.K.; van den Berg, F.W.J.; Nielsen, D.S.; Andreasen, A.S.; Pedersen, B.K.; Al-Soud, W.A.; Sørensen, S.J.; Hansen, L.H.; Jakobsen, M. Gut microbiota in human adults with type 2 diabetes differs from non-diabetic adults. PLoS One 2010, 5, e9085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitten, A.K.; Ryan, L.; Lee, G.C.; Flores, B.E.; Reveles, K.R. Gut microbiome differences among Mexican Americans with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0251245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri-Rosario, D.; Martínez-López, Y.E.; Esquivel-Hernández, D.A.; Sánchez-Castañeda, J.P.; Padron-Manrique, C.; Vázquez-Jiménez, A.; Giron-Villalobos, D.; Resendis-Antonio, O. Dysbiosis signatures of gut microbiota and the progression of type 2 diabetes: a machine learning approach in a Mexican cohort. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2023, 14, 1170459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Esteve, E.; Tremaroli, V.; Khan, M.T.; Caesar, R.; Mannerås-Holm, L.; Ståhlman, M.; Olsson, L.M.; Serino, M.; Planas-Fèlix, M.; et al. Metformin alters the gut microbiome of individuals with treatment-naive type 2 diabetes, contributing to the therapeutic effects of the drug. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 850–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).