1. Introduction

Bee viruses represent a significant threat to honeybee colonies and honey production worldwide (Grozinger & Flenniken, 2019). Under optimal nutritional and health conditions, honeybees exhibit both individual and population-level resistance mechanisms that help maintain these viruses at sublethal levels (Brutscher & Flenniken, 2015). However, factors such as stress, immunosuppression or nutritional deficiencies, can disrupt this balance, leading to viral infections that manifest as clinical signs of disease and ultimately weaken the colony (Gauthier et al., 2007). The procedural stress and frequent handling inherent in queen-rearing production expose honeybees to conditions that may enhance virus circulation within the colony (Gregorc & Bakonyi, 2012). In queen rearing, overt infections can severely impact commercialization and supply of queens to beekeepers, thereby jeopardizing the entire apiary economy.

Ravoet et al. (2015) provided further evidence of vertical virus transmission by detecting the presence of viruses in queen eggs during a sanitary control of a breeding program (Ravoet et al., 2015). Additionally, viral genomes of five viruses, namely Iflavirus aladeformis (DWV), Aparavirus apisacutum (ABPV), Triatovirus nigereginacellulae (BQCV), Iflavirus sacbroodi (SBV), and A. mellifera filamentous virus (AmFV) were detected in 91% of semen samples from apparently healthy drones used for artificial insemination. This finding suggests that the commercialization of drones may facilitate viruses transmission (Prodělalová et al., 2019). Moreover, occurrences of ABPV, BQCV, and DWV have been reported in various colony materials (such as tissue and adult feces), workers, nurses, and queens during the breeding process (Žvokelj et al., 2020). In an experiment conducted during the queen development stages, viruses were occasionally detected: BQCV was found in all worker samples and in queens from mating nuclei, while DWV was only detected in queen samples (Žvokelj et al., 2020). In Argentina, we previously reported the presence and impact of ABPV and BQCV, in queen-rearing apiaries (Ferrufino et al., 2020), underscoring the importance of controlling these viruses in honeybee queens’ production.

Considering the harmful effect of viral infections on honeybee health and survival, the development of effective control technologies is of utmost importance. Gene silencing, mediated by RNA interference (RNAi), is one of the most important defense mechanisms that bees have against pathogens (Brutscher & Flenniken, 2015). Focusing on this immune pathway, several authors have conducted gene silencing experiments mediated by double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) to control viral infections. For instance, in 2009, Maori et al. demonstrated a reduction in bee mortality caused by IAPV through dsRNA ingestion (Maori et al., 2009). Similarly, in 2012, Desai and colleagues controlled DWV infection in first-stage larvae and in adult bees via oral administration of dsRNA specific to DWV (Desai et al., 2012). Moreover, a large-scale field study applying specific dsRNA against IAPV showed that this treatment effectively protected the bee population from viral infection and improved overall colony health (Hunter et al., 2010). However, to date, no studies have been conducted to assess the effect of RNAi on ABPV infection in adult honeybees.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of RNAi technology, mediated by dsRNA, in reducing ABPV infection and improving the survival of adult honeybees.

2. Materials and Methods

Production and stability of dsRNA

VP1 and replicase gene fragments were amplified by PCR following the methodologies described by Texeira et al. (2008) and Gauthier et al. (2007) respectively. (Gauthier et al., 2007; Teixeira et al., 2008). The resulting amplicons were cloned into the pGEM T-easy vector (Promega) according to the manufacturer's recommendations, and their identities were verified by sequencing. The gene fragments were then individually subcloned into the pL4440 vector using classical cloning techniques (Sambrook et al., 1989).

ABPV gene fragments were used as templates for dsRNA synthesis via in vitro transcription, utilizing the MEGAscript™ RNAi Invitrogen Commercial Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. The synthesized dsRNA products were analyzed by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gels and quantified using a Nanodrop2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher). A positive control dsRNA synthesis provided by the kit manufacturer was included. A total of 200 µg of dsRNA was produced for each target.

A stability assay of the synthesized dsRNA was conducted under various conditions over a period of 19 days. For this purpose, 1 µg of dsRNA was aliquoted into 39 tubes (1μg/tube), with 13 tubes assigned to each condition: diluted in water and stored at 4°C, diluted in water and stored at 32°C, diluted in sucrose and stored at 32°C. On each of the designated days, one sample from each condition was frozen at -80°C and stored until the end of the assay. The products were subsequently analyzed by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel (

supplementary figure 1).

Amplification and purification of viral stock

To prepare the infective virus stock, a macerate from ABPV positive samples from Entre Rios province, Argentina (Ferrufino et al., 2020), was obtained and quantified by RT-qPCR (Locke et al., 2012). 1-5 μL of macerate (containing 10

3 gc/μL) were inoculated into 44 bee pupae (

supplementary figure 2). After 3 days, the pupae were processed in 5 ml of NET buffer (0.1 M NaCl, 0.004 M EDTA, 0.05 M Tris, pH 8.0) and centrifuged at 3645 x g for 45 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was collected, and subsequent 3 washes with chloroform were performed by centrifuging at 405 x g for 5 min and collecting the supernatant in each wash. The recovered material was disintegrated by adding 0.5 ml of 6% Sarkosyl for each 2 ml of supernatant, and the mixture was incubated at 4°C for 15 minutes. Purification was achieved through continuous sucrose gradients (15 to 41.25%) and ultracentrifuged at 28,000 rpm for 3 hours at 4°C in a Beckman 28.38 rotor (Pega et al., 2013). The gradient containing the viral suspension was fractionated into 96-well microplates using a peristaltic pump with a flow rate of 1.12 ml/min. The eluates were collected in order of increasing density and absorbance readings were taken at 260 and 280 nm using a microvolume spectrophotometer (Nanodrop 2000, Thermo Fisher) (

supplementary figure 3). The purified viruses were quantified and stored at -80°C. The absence of DWV, BQCV, IAPV, KBV, CBPV, and SBV was confirmed by RT-qPCR (Locke et al., 2012)

ABPV quantification

The presence and quantification of ABPV were assessed by RT-qPCR following the protocol described by (Locke et al., 2012). Briefly, one-step RT-qPCR was performed using iTaq Universal SYBR Green one-step kit (Bio-Rad). The reaction mixture contained 1 µL of each primer (10 µM), 0.25 µL iScript RT, 3.75 µL H2O and 5 µL of RNA template, in a final volume prepared in white tubes. The thermal cycling profile was as follows: 10 min at 50°C, 3 minutes at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 seconds at 95°C, 1 minute at 60°C and a melting curve from 65°C to 95°C increasing 0.5°C every 5 seconds. All assays were performed on a CFX96 thermocycler (Biorad).

For quantification, a five-points standard curve was generated with Ct values obtained from known concentrations of a plasmid containing the target sequence. These concentrations prepared as 10-fold dilutions ranging from 10

2 to 10

6 genome copies/µL. Each point on the standard curve was assayed in triplicate. Viral loads (VLs) were expressed as genome copies/µL reaction. Efficiency of the reactions ranged from 95-105% (

Supplementary Table 1).

Bioassays

Adult bees used in the following experiments were obtained from healthy colonies maintained at the research apiary at the Instituto de Genética Ewald A. Favret INTA-CONICET. 30 randonmly selected bees from each colony were collected to determine background virus VLs before the assay.

Frames of emerging brood were removed and placed in an observational colony that was kept for 1-2 days in an incubator at 32 °C and 60% relative humidity. Newly emerged bees from these frames were mixed together and pooled according to the experimental design.

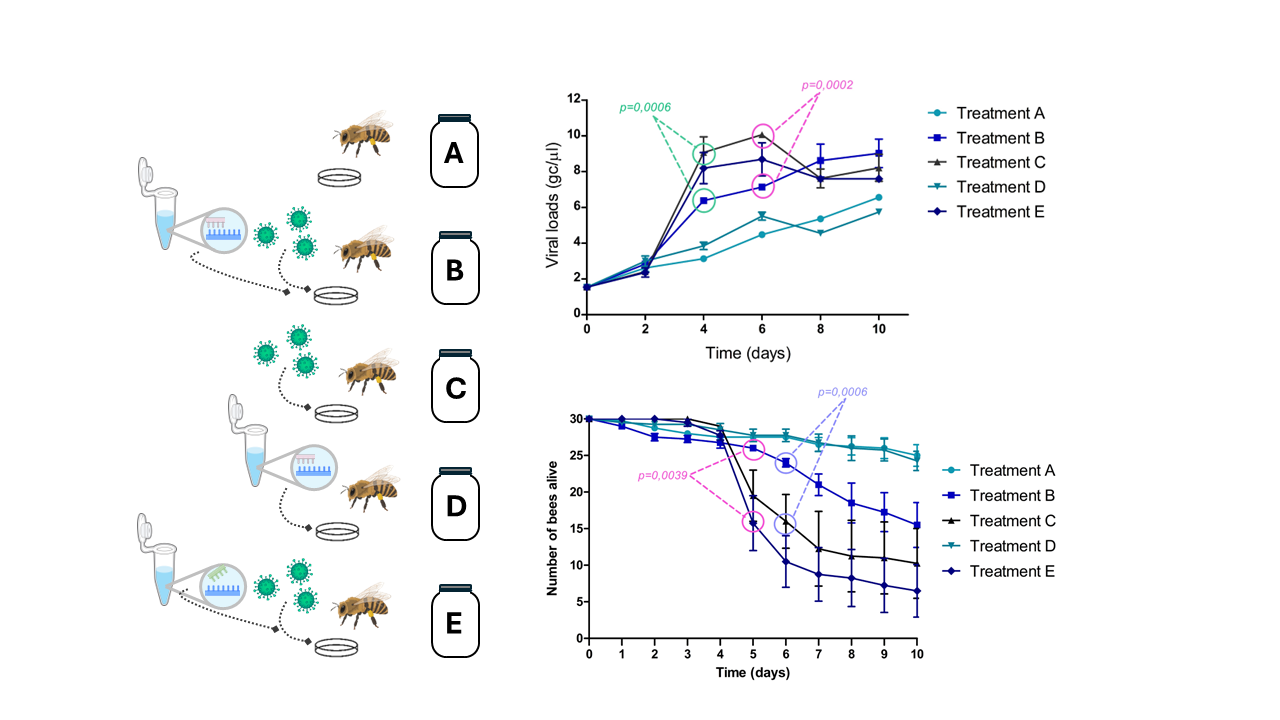

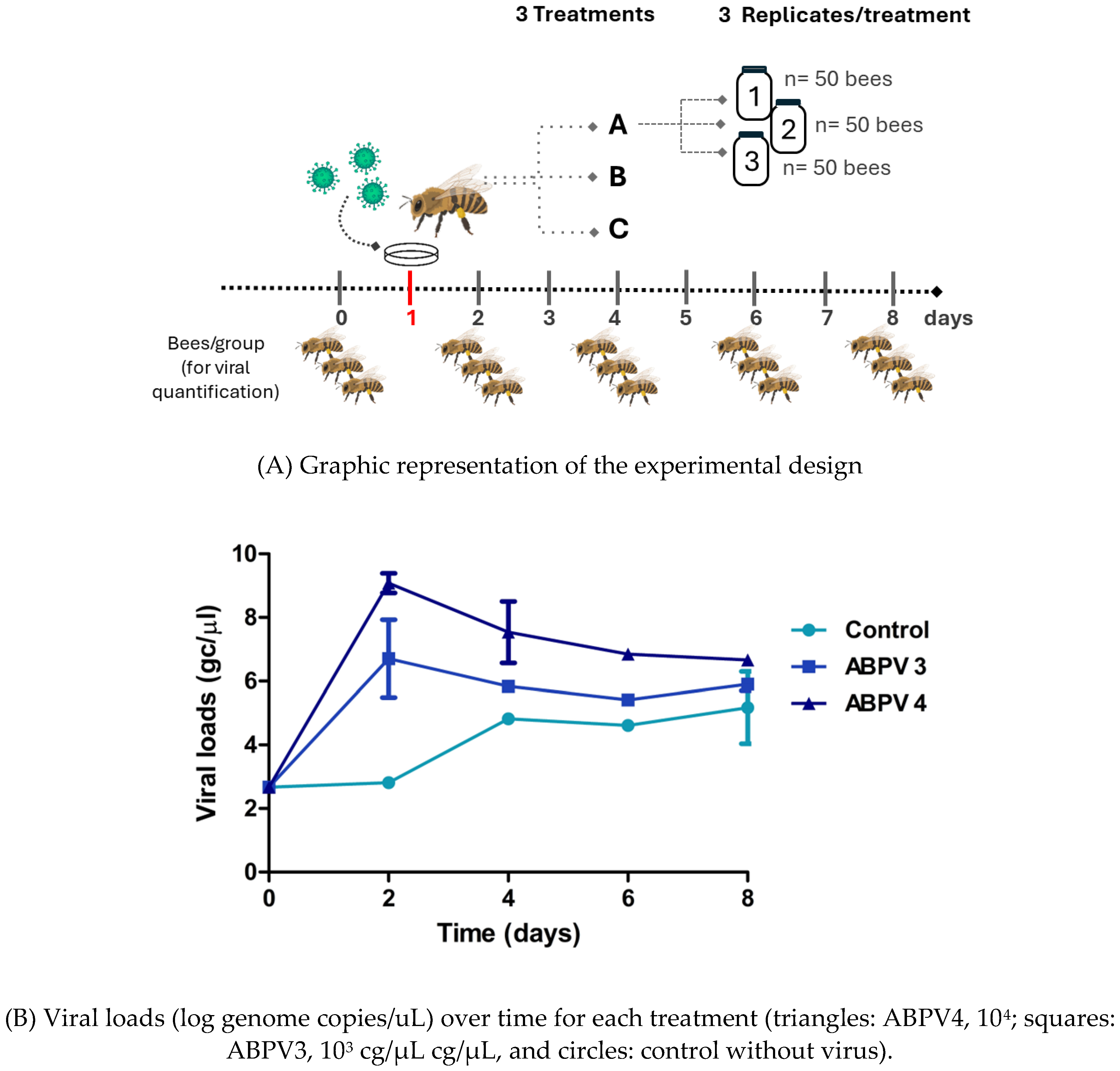

Assay 1 - ABPV infection.

To determine the optimal amount of virus dose for subsequent silencing assays, a repeated measures experiment was conducted on adult bees. The experiment involved three treatments, which included two different doses of ABPV (10

3gc/µl and 10

4gc/µl) and a control group. Each treatment was replicated three times, with each replicate consisting of 50 bees placed in a 3 L glass jar. The bees in each jar were fed according to their assigned treatment (

supplementary figure 4), as described below.

Newly emerged

A. mellifera workers were individually marked on the thorax with different colors using a queen bee marker to distinguish bees for survival evaluation (N= 30 in each jar) from those intended for viral load quantification (N= 20 in each jar) (

supplementary figure 4). The jars were placed in a breeding chamber (SANYO, Versatile Environmental Test Chamber MLR-350) under controlled conditions of 34 ± 1°C and 65 ± 5% relative humidity.

On day 1, bees assigned to treatments B and C were orally administered honey containing 1 ml of ABPV at concentration of 10

3 gc/μL and 10

4 gc/μL, respectively. Bees in treatment A (the control group), received only honey (

table 1). Three bees from each group were sampled on days 0, 2, 4, 6 and 8, and frozen at -80°C for subsequent VLs quantification (

figure 1A). From day 2 onwards, all bees were fed with 1 ml of honey and 1 ml of water every 24 h. The number of live bees was recorded daily for 10 days.

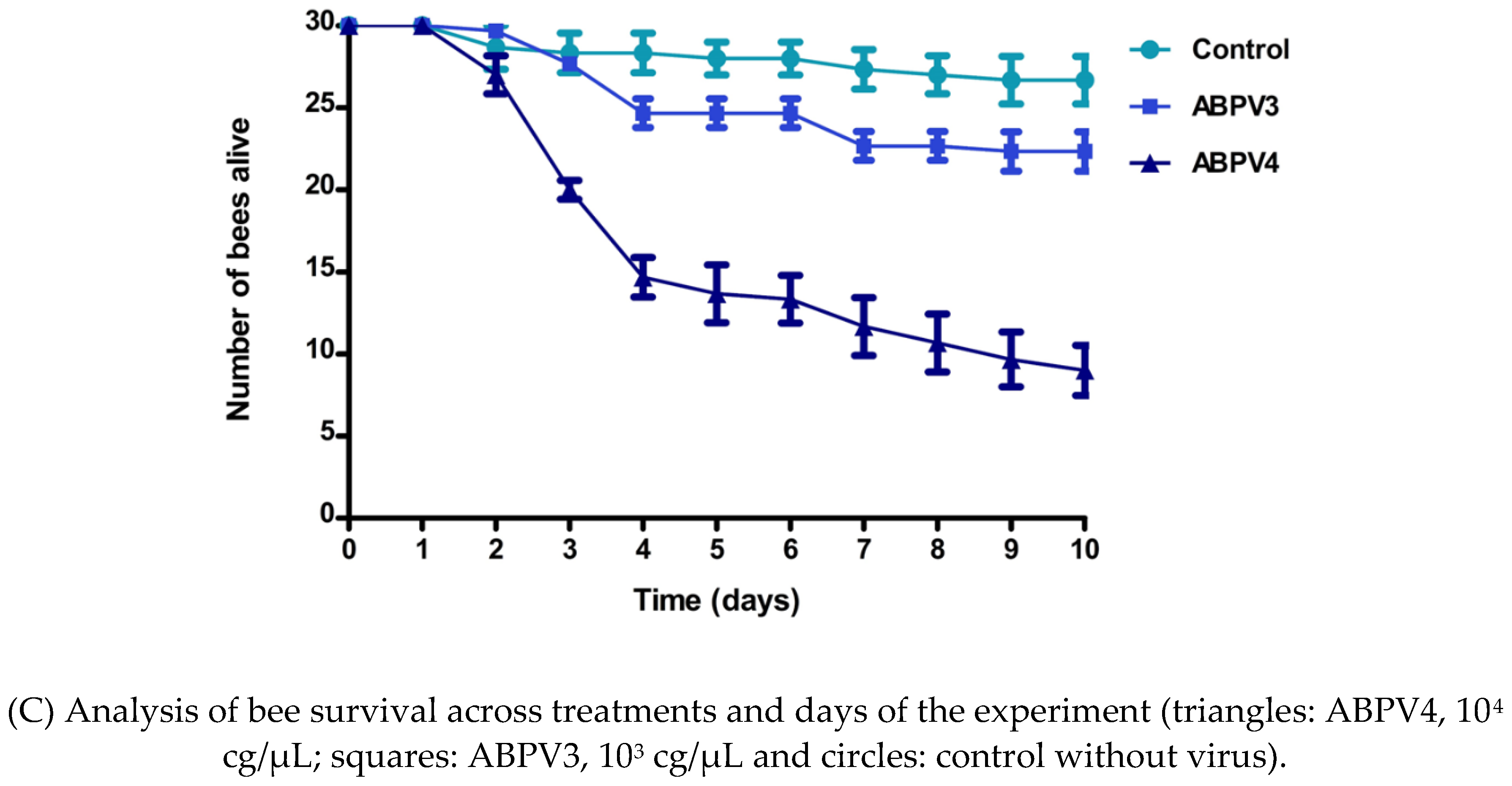

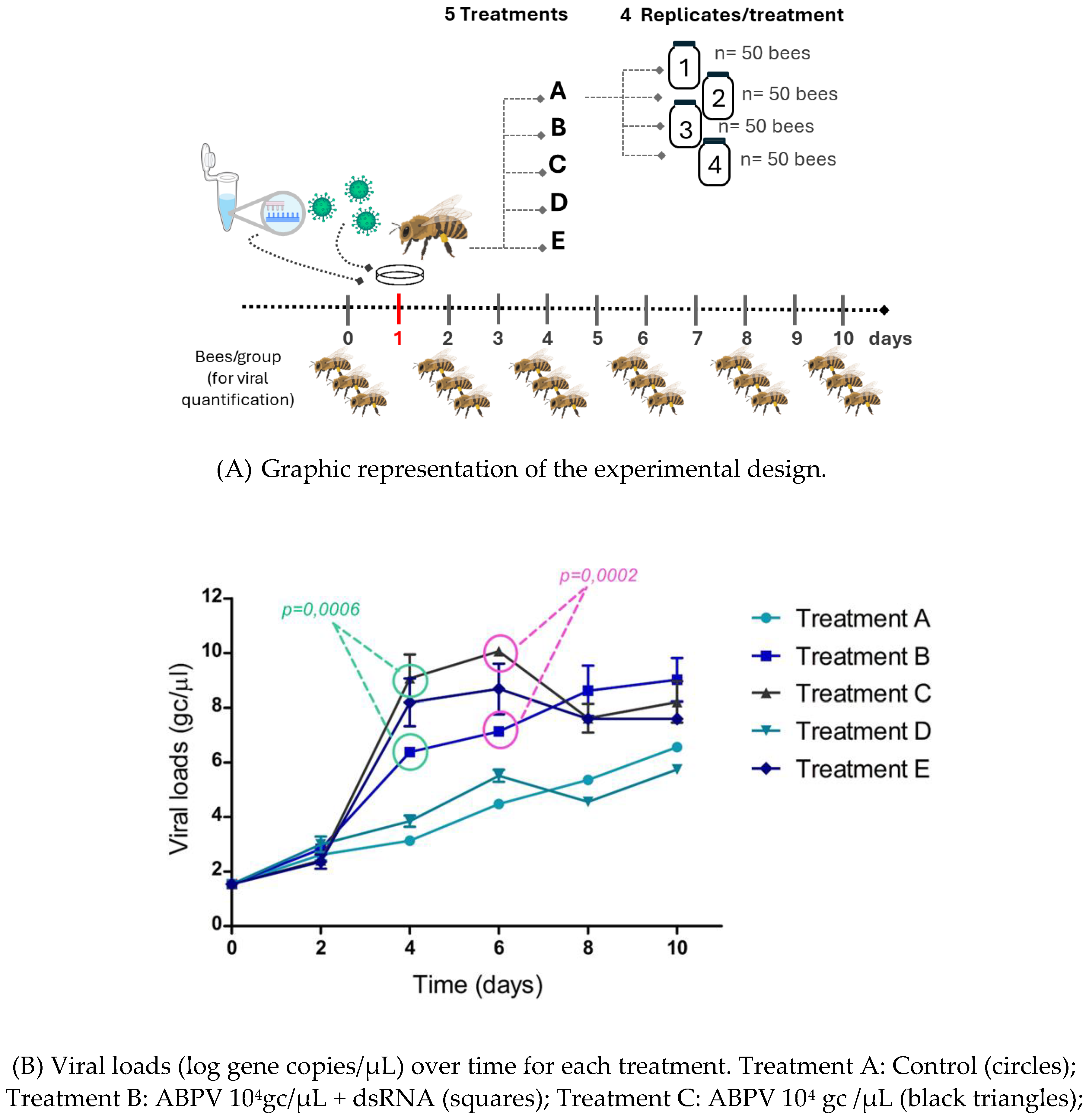

Assay 2 - Viral silencing.

A second experiment was conducted to evaluate the effect of oral dsRNA administration on VLs and bee survival.

The experiment included five treatments, each with four replicates. In each replicate, 50 bees were placed in a 3 L glass jar and fed according to their assigned treatment. Bees were marked with different colors, and the jars were placed in the breeding chamber as described in assay 1.

On day 1, bees in treatment A received only honey (control group). Bees in treatment B received specific dsRNA + virus, treatment C received virus only, treatment D received specific dsRNA only, and treatment E received non-specific dsRNA + virus (

table 2).

Each replicate received 1 ml of virus suspension containing 10

4 genomic copies/μl (2x10

5 gc/bee), and the dsRNA dosage per bee was 1 μg. The experiment lasted 10 days. Three bees from each group were removed on days 0, 2, 4, 6 and 8, and frozen at -80°C to subsequent viral load quantification (

figure 2A). Starting from day 2, all bees were fed with honey and water every 24 h. The number of live bees was recorded daily.

Statistical analyses

The data on VLs were analyzed using a General Linear Model (GLM). The response variable was the logarithm of the virus concentration, while the explanatory variables were time and treatments, both considered as fixed factors. The Shapiro-Wilks test was used to assess the assumption of Normality. Since viral load measurements from the same groups of bees were taken at six different time points, there was a lack of independence between observation. To account for this, a correlation structure (composite symmetry matrix) was applied to the group variable. Additionally, due to the lack of homogeneity of variances across treatments, the variance structure was modeled, incorporating the Identity function (varIdent) into the model.

Survival data was analyzed using a Generalized Linear Model (GLM) to assess differences between treatments and over time treated as fixed factors. The response variable was the number of live bees over total bees in each glass jar (N=50).

Orthogonal contrasts were performed to determine if there were significant differences between treatments at each time point. All analyzes were conducted using Infostat Software (Di Rienzo et al., 2020)

3. Results

3.1. ABPV infection kinetics and bee survival

The aim of this experiment was to determine the virus dose required to observe clinical manifestation of ABPV infection and to study the kinetics of viral load (VL) in adult bees. To achieve this, bees were orally infected with two different doses of ABPV, and both VLs and mortality were monitored. On the third day post infection (dpi), an exponential increase in VLs was observed in both ABPV-treated groups (day 2 in

figure 1B). The group that received 104 gc/μL reached a viral load level of 10

9 gc/µL, while the group treated with 10

3 gc/μL peaked at 10

5,8 gc/µL (

figure 1B). In the control group, which started with a basal VL, the viral load increased to 10

4,8 gc/µL by day 4. VLs remained constant across all treatments from day 4 until the end of the experiment. Regarding survival, a significant decrease was observed on the fourth day post-infection in the group treated with ABPV at 10

4 gc/µL (

figure 1C). In contrast, the control group maintained a survival rate greater than 85%. Additionally, clinical signs of ABPV infection were observed in the virus treated groups, including hair loss on the thorax and abdomen, gradual darkening, tremors and an inability to fly (

supplementary figure 5).

3.2. Viral silencing experiment

The effect of oral administration of specific dsRNA to inhibit ABPV infection was evaluated in an in vivo experiment using adult bees. dsRNAs targeting the VP1 and replicase genes were generated as a viral silencing tool.

First, the stability of the dsRNA was assessed in vitro under different conditions over a period of 19 days. It was observed that the dsRNA remains stable in water at 4°C throughout the experiment. At 32°C, both in water and sucrose, the dsRNA remained stable until day 18, after which slight signs of degradation were detected (

Supplementary figure 1).

The experimental design is shown in

figure 2A. On day 4 (1-day post-infection), an exponential increase in average VLs was observed in treatments C (ABPV 10

4 gc/μL) and E (ABPV 10

4 gc/μL + non-specific dsRNA). In treatment B, which included the administration of specific dsRNA (ABPV 10

4 gc/μL + dsRNA), VLs were significantly lower than those in treatments C (p=0.0006) and E (p=0.0306). Significant differences were also observed on day 6 between treatments B and C (p=0.0002) (

figure 2B).

VLs in the control treatments (A and D) slightly increased but remained significantly lower than those in the virus treated groups (treatments C and E) from day 4 until the end of the experiment.

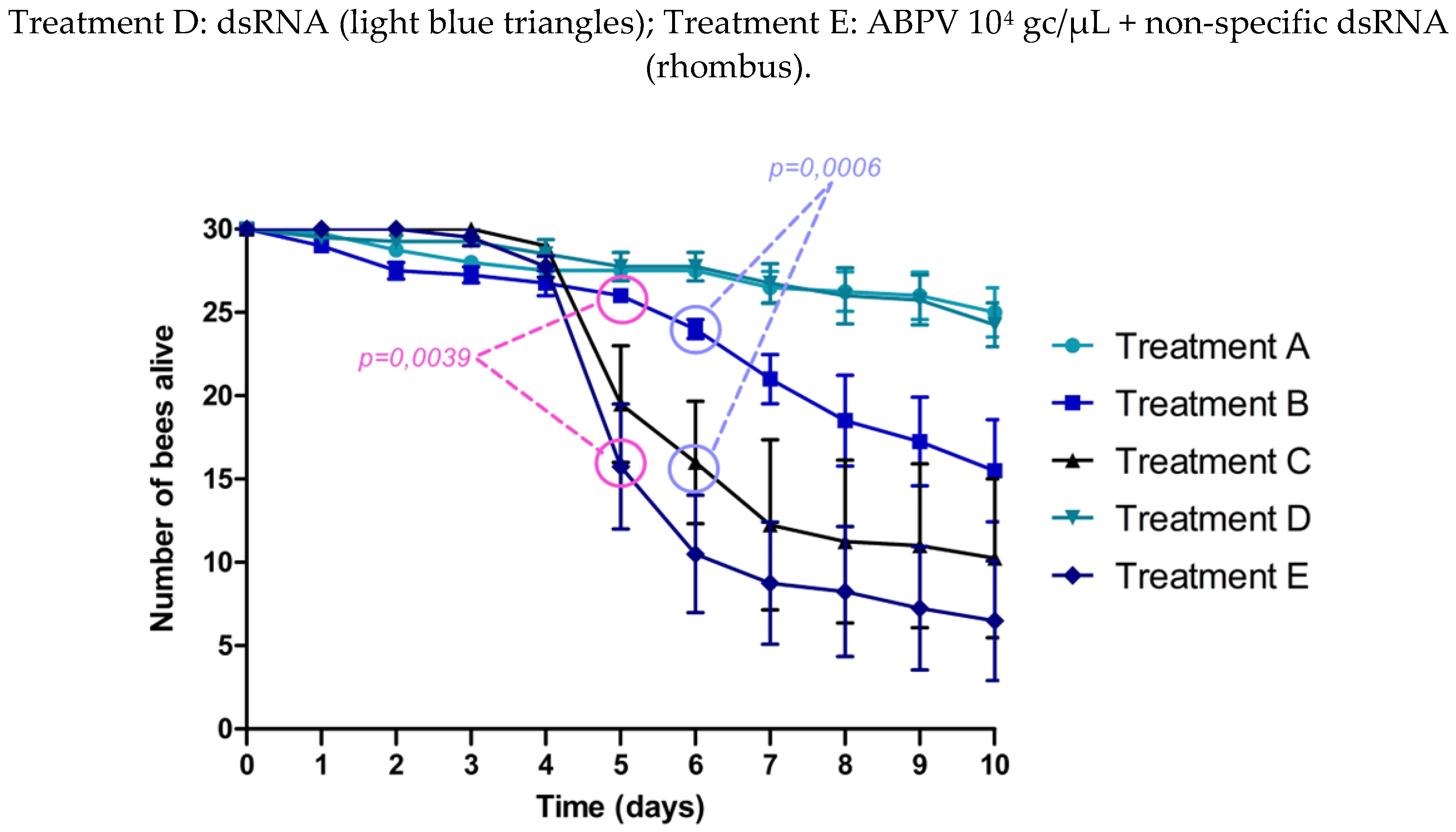

A significant decline in bee survival was observed in treatments C (ABPV 10⁴ gc/μL) and E (ABPV 10⁴ gc/μL + non-specific dsRNA), starting on day 5 (2 dpi). In treatment B (ABPV 10⁴ gc/μL + specific dsRNA), a slight reduction in survival was noted on day 6. On day 5, survival rates in treatment B were significantly higher compared to treatment E (p= 0.0039). By day 6, survival in treatment B was significantly greater than in treatment C and E (p = 0.0006 and p < 0.0001, respectively). Up to day 7, no significant differences in survival were observed between treatment B and the control treatments (A and D). In the control group (treatment A), 25 to 30 bees remained alive by the end of the experiment, representing a survival rate of 83.3% to 100% (

figure 2C).

The impact of dsRNA administration was quantified, showing an average reduction in VLs of 2.31 to 3.06 log gc/μL (95% CI) at time point 4 (1 dpi), and a reduction of 2.48 to 3.48 log gc/μL (95% CI) at time point 6 (3 dpi).

1.3. Figures, Tables and Schemes

Table 1.

Description of the treatments and groups used in the infection experiment.

Table 1.

Description of the treatments and groups used in the infection experiment.

| Groups |

Treatment |

Description |

| 1-2-3 |

A |

Control |

| 4-5-6 |

B |

ABPV 103 gc/µl |

| 7-8-9 |

C |

ABPV 104 gc/µl |

Table 2.

Description of the treatments and groups used in the silencing experiment.

Table 2.

Description of the treatments and groups used in the silencing experiment.

| Groups |

Treatment |

Description |

| 1-2-3-4 |

A |

Control |

| 5-6-7-8 |

B |

ABPV 104 gc/µl + dsRNA |

| 9-10-11-12 |

C |

ABPV 104 gc/µl |

| 13-14-15-16 |

D |

dsRNA |

| 17-18-19-20 |

E |

ABPV 104 gc/µl + dsRNA non-specific |

Table 3.

Contrasts between treatments from day 5 onwards, along with corresponding p-values, were obtained by fitting a generalized linear mixed model and comparing treatments using orthogonal contrasts.

Table 3.

Contrasts between treatments from day 5 onwards, along with corresponding p-values, were obtained by fitting a generalized linear mixed model and comparing treatments using orthogonal contrasts.

| Time (day) |

Contrasts |

p-value |

| 5 |

Treatment B – Treatment A |

0.712 |

| Treatment B – Treatment C |

0.0757 |

| Treatment B – Treatment D |

0.6693 |

| Treatment B – Treatment E |

0.0039 |

| 6 |

Treatment B – Treatment A |

0.3841 |

| Treatment B – Treatment C |

0.0195 |

| Treatment B – Treatment D |

0.3532 |

| Treatment B – Treatment E |

<0.0001 |

| 7 |

Treatment B – Treatment A |

0.1527 |

| Treatment B – Treatment C |

0.0048 |

| Treatment B – Treatment D |

0.1365 |

| Treatment B – Treatment E |

<0.0001 |

| 8 |

Treatment B – Treatment A |

0.0373 |

| Treatment B – Treatment C |

0.0126 |

| Treatment B – Treatment D |

0.0432 |

| Treatment B – Treatment E |

0.0002 |

| 9 |

Treatment B – Treatment A |

0.0166 |

| Treatment B – Treatment C |

0.0263 |

| Treatment B – Treatment D |

0.0195 |

| Treatment B – Treatment E |

0.0002 |

| 10 |

Treatment B – Treatment A |

0.0069 |

| Treatment B – Treatment C |

0.0487 |

| Treatment B – Treatment D |

0.0119 |

| Treatment B – Treatment E |

0.0003 |

Figure 1.

ABPV infection in adult bees.

Figure 1.

ABPV infection in adult bees.

Figure 2.

ABPV silencing experiment.

Figure 2.

ABPV silencing experiment.

4. Discussion

Some studies have demonstrated the feasibility of controlling viral infections in bees through the oral administration of dsRNA. Maori et al. (2009) reported a reduction in bee mortality caused by IAPV and another large-scale study against that virus confirmed that specific dsRNA treatments were effective in protecting bee population from IAPV infection. Moreover, Li et al. (2010) reported successful blocking of CSBV infection using specific dsRNA sequences. DWV infection effects have been also reduced by feeding bees with DWV-specific dsRNA. (Desai et al., 2012; Hunter et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2010; Maori et al., 2009). Recently, SBV was silenced in A. Cerana by the application of exogenous dsRNA produced in Bacillus thurigiensis (Park et al., 2020)

In our study, we initially performed a viral kinetics study to select the optimal viral dose and assess the progression of VLs over time. While we did not conduct a specific dose-response study for the dsRNA, our selection of the dsRNA dose was informed by previous research in the field. Based on this, the dsRNA dose used in the viral silencing experiment was set at 1 μg per bee (Desai et al., 2012; Maori et al., 2009).

At the beginning of the ABPV silencing experiment and up to day 2, all treatments exhibited similar behavior, with no noticeable increase in VLs. A slight increase in basal VLs was observed across all treatments, consistent with findings by Dalmon et al. (2019), who reported similar patterns of DWV VLs under varying temperature conditions (Dalmon et al., 2019). This increase may be attributed to stress factors, such as handling bees outside their hive, isolation from the colony, or the absence of the queen, which could act individually or synergistically to influence viral replication. Significant differences were observed on days 4 (p= 0.0006) and 6 (p= 0.0002), with treatments C (ABPV 10

4 gc/μL) and E (ABPV 10

4 gc/μL + non-specific dsRNA) showing a peak in viral replication. Notably, treatment B (ABPV 10

4 gc/μL + dsRNA), exhibited a significant reduction in average VLs compared to treatments C and E. On day 6, significant differences in average VLs were observed between treatments B and C. Thus, the administration of specific dsRNA reduced the viral replication curve, leading to higher bee survival in treatment B. By day 5 (2 days post-infection) significant differences in the number of live bees were noted between treatment B and treatment E, and by day 6 (3 dpi), between treatment B and treatments C and E (

Table 3). These findings are consistent with Desai et al. (2012), who demonstrated that feeding DWV-specific dsRNA reduced the adverse effects of DWV infections.

Additionally, in this study, we estimated that each μg of dsRNA administered resulted in a decrease in average VLs from 2.48 to 3.48 log gc/μL by day 6 (3 dpi).

One of the most promising results was that treatment D (dsRNA) showed no toxic effects and performed similarly to controls. By day 8, it is likely that depletion or degradation of specific dsRNA contributed to the observed increase in viral load. To ensure continued efficacy, a second dsRNA administration on day 5 could be considered. Additionally, evaluating higher concentration of dsRNA or targeting additional genes could further prolong the antiviral effect.

Overall, the data indicates that specific dsRNA treatment (Treatment B) provided significant protective effects against ABPV infection, resulting in higher survival rates compared to the virus-only and non-specific dsRNA groups. This suggests that RNA interference mediated by specific dsRNA effectively reduces viral load and improves bee survival. The decreased survival observed in treatments C and E highlights the virulence of ABPV and the ineffectiveness of non-specific dsRNA.

These findings underscore the potential of targeted dsRNA treatments as a viable strategy for mitigating viral infections in honeybee populations. Further research is needed to optimize dsRNA delivery methods and to assess the long-term impacts on colony health and productivity.

5. Conclusions

For the first time, ABPV-dsRNA targeting just two genes significantly reduces the mortality caused by ABPV infection. These dsRNA can be used to prevent viral infections during the critical periods of queen production. Additionally, administrating dsRNA prior to queen transport for export, typically a stressful process associated with increasing mortality, could help mitigate this risk by reducing baseline virus level. Furthermore, dsRNA could be employed to produce virus-free hives for laboratory experiments or to inhibit viral replication in vitro cultures where controlling baseline virus presence is a major challenge. Continued research into virus prevention techniques is essential to minimize losses in queen-rearing production and ensure the highest health standards for marketable products.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

Preprints.org, Figure S1: Supplementary figure 1. Agarose gel electrophoresis of dsRNA conserved in different conditions; Figure S2: Supplementary figure 2.

In vivo virus amplification; Figure S3: Supplementary figure 3. Sucrose density gradient profile of ABPV particles produced in infected bee pupae. Figure S4: Supplementary figure 4. Collection procedure and painting of recently emerged worker bees. Figure S5: Supplementary figure 5. Signs of ABPV infection. Table S1: Efficiency of the RT-qPCR for ABPV quantification.

Author Contributions

CF, AS and MJDS conceived and designed experiments. CF and MJDS wrote the main manuscript text. CF carried out the experiments and performed the statistical analysis. RR collaborated with bioassays. FG collaborated with viral purification and quantification. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by 2023-PE-L01-I069 Aportes a la sostenibilidad de la apicultura Argentina, Programa Nacional de Apicultura.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank to Maximiliano Jordan for his technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Brutscher, L. M., & Flenniken, M. L. RNAi and Antiviral Defense in the Honey Bee. Journal of Immunology Research 2015, 941897. [CrossRef]

- Desai, S. D., Eu, Y.-J., Whyard, S., & Currie, R. W. (2012). Reduction in deformed wing virus infection in larval and adult honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) by double-stranded RNA ingestion: Reduction in DWV in honey bees using RNAi. Insect Molecular Biology, 21(4), Article 4. [CrossRef]

- Di Rienzo, J. A., Casanoves, F., Balzarini, M. G., Gonzalez, L., Tablada, M., & Robledo, C. W. (2020). InfoStat versión 2018. Centro de Transferencia InfoStat, FCA, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina. URL http://www.infostat.com.ar.

- Ferrufino, C., Figini, E., Gonzalez, F., Dus Santos, M. J., & Salvador, R. (2020). Detection of Honeybee Viruses in a Queen-Rearing Apiary from Argentina. Modern Concepts & Developments in Agronomy, 6(1). [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, L., Tentcheva, D., Tournaire, M., Dainat, B., Cousserans, F., Colin, M. E., & Bergoin, M. (2007). Viral load estimation in asymptomatic honey bee colonies using the quantitative RT-PCR technique. Apidologie, 38(5), Article 5. [CrossRef]

- Gregorc, A., & Bakonyi, T. (2012). Viral infections in queen bees (Apis mellifera carnica) from rearing apiaries. Acta Veterinaria Brno, 81(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Grozinger, C. M., & Flenniken, M. L. (2019). Bee Viruses: Ecology, Pathogenicity, and Impacts. En Annual Review of Entomology (Vol. 64, Número Volume 64, 2019, pp. 205-226). Annual Reviews. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, W., Ellis, J., vanEngelsdorp, D., Hayes, J., Westervelt, D., Glick, E., Williams, M., Sela, I., Maori, E., Pettis, J., Cox-Foster, D., & Paldi, N. (2010). Large-Scale Field Application of RNAi Technology Reducing Israeli Acute Paralysis Virus Disease in Honey Bees (Apis mellifera, Hymenoptera: Apidae). PLoS Pathogens, 6(12), Article 12. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Zhang, Y., Yan, X., & Han, R. (2010). Prevention of Chinese Sacbrood Virus Infection in Apis cerana using RNA Interference. Current Microbiology, 61(5), Article 5. [CrossRef]

- Locke, B., Forsgren, E., Fries, I., & de Miranda, J. R. (2012). Acaricide Treatment Affects Viral Dynamics in Varroa destructor-Infested Honey Bee Colonies via both Host Physiology and Mite Control. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 78(1), 227-235. [CrossRef]

- Maori, E., Paldi, N., Shafir, S., Kalev, H., Tsur, E., Glick, E., & Sela, I. (2009). IAPV, a bee-affecting virus associated with Colony Collapse Disorder can be silenced by dsRNA ingestion. Insect Molecular Biology, 18(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Park, M. G., Kim, W. J., Choi, J. Y., Kim, Jong H, Park, D. H., Kim, Jun Y, Wang, M., & Je, Y. H. (2020, may). Development of a Bacillus thuringiensis based dsRNA production platform to control sacbrood virus in Apis cerana. Pest Management Science, Volume76(Issue5), 1699-1704. [CrossRef]

- Prodělalová, J., Moutelíková, R., & Titěra, D. (2019). Multiple Virus Infections in Western Honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) Ejaculate Used for Instrumental Insemination. Viruses, 11(4), Article 4. [CrossRef]

- Ravoet, J., De Smet, L., Wenseleers, T., & de Graaf, D. C. (2015). Vertical transmission of honey bee viruses in a Belgian queen breeding program. BMC Veterinary Research, 11(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Sambrook, J., Fritsch, E. F., & Maniatis, T. (1989). Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual (Número libro 1). Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=8WViPwAACAAJ.

- Teixeira, E. W., Chen, Y., Message, D., Pettis, J., & Evans, J. D. (2008). Virus infections in Brazilian honey bees. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 99(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Žvokelj, L., Bakonyi, T., Korošec, T., & Gregorc, A. Appearance of acute bee paralysis virus, black queen cell virus and deformed wing virus in Carnolian honey bee ( Apis mellifera carnica ) queen rearing. Journal of Apicultural Research 2020, 59(1), 53–58. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).