Submitted:

09 December 2024

Posted:

11 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Case Report

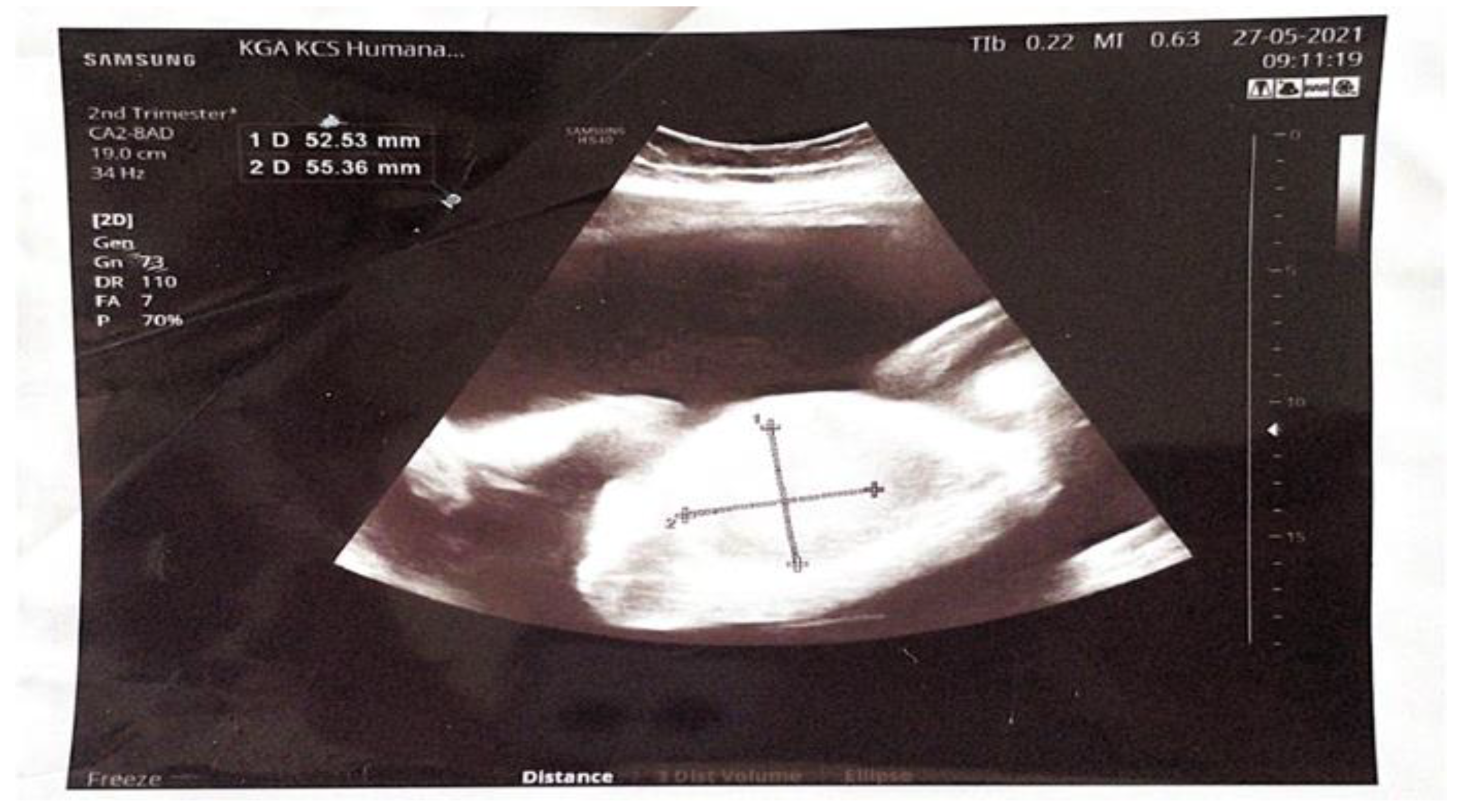

2.1. Clinical Presentation

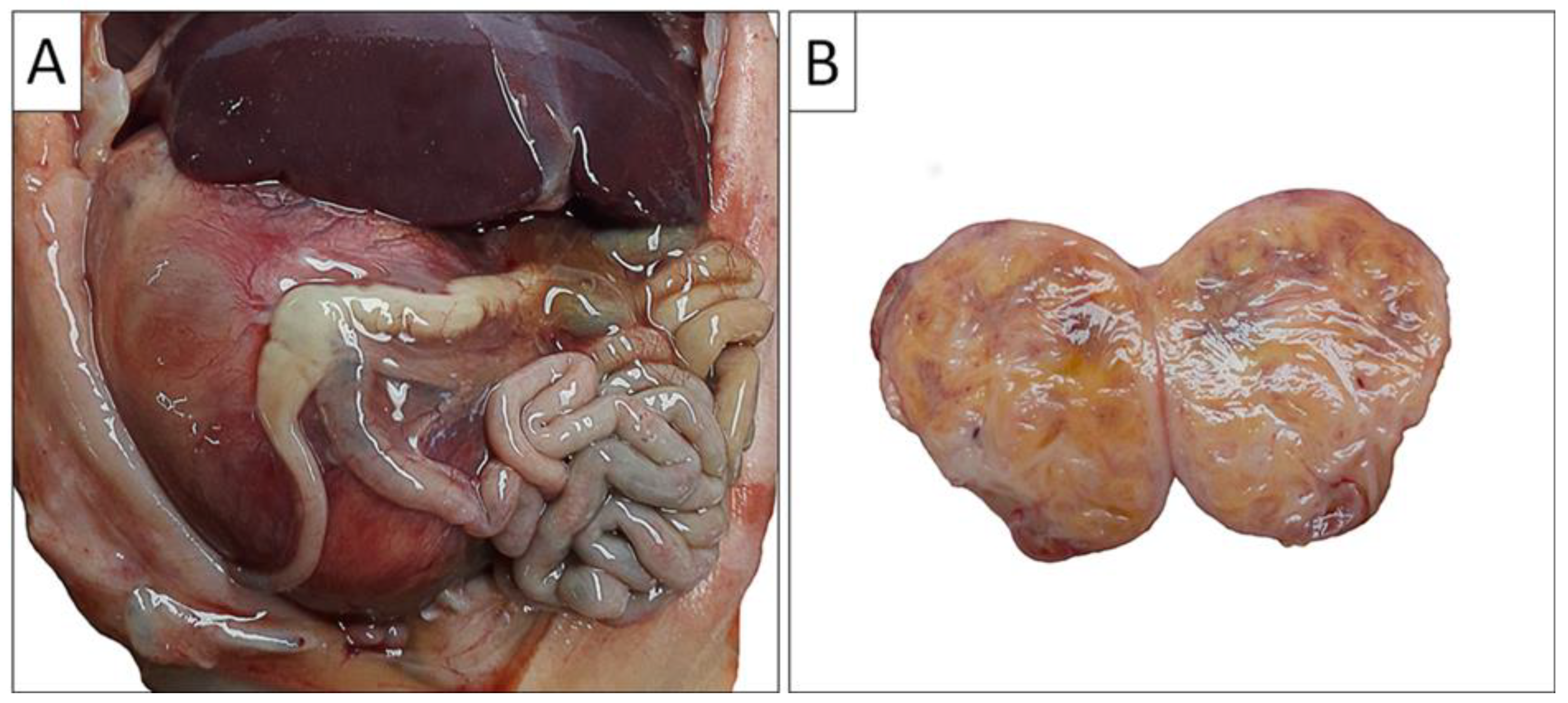

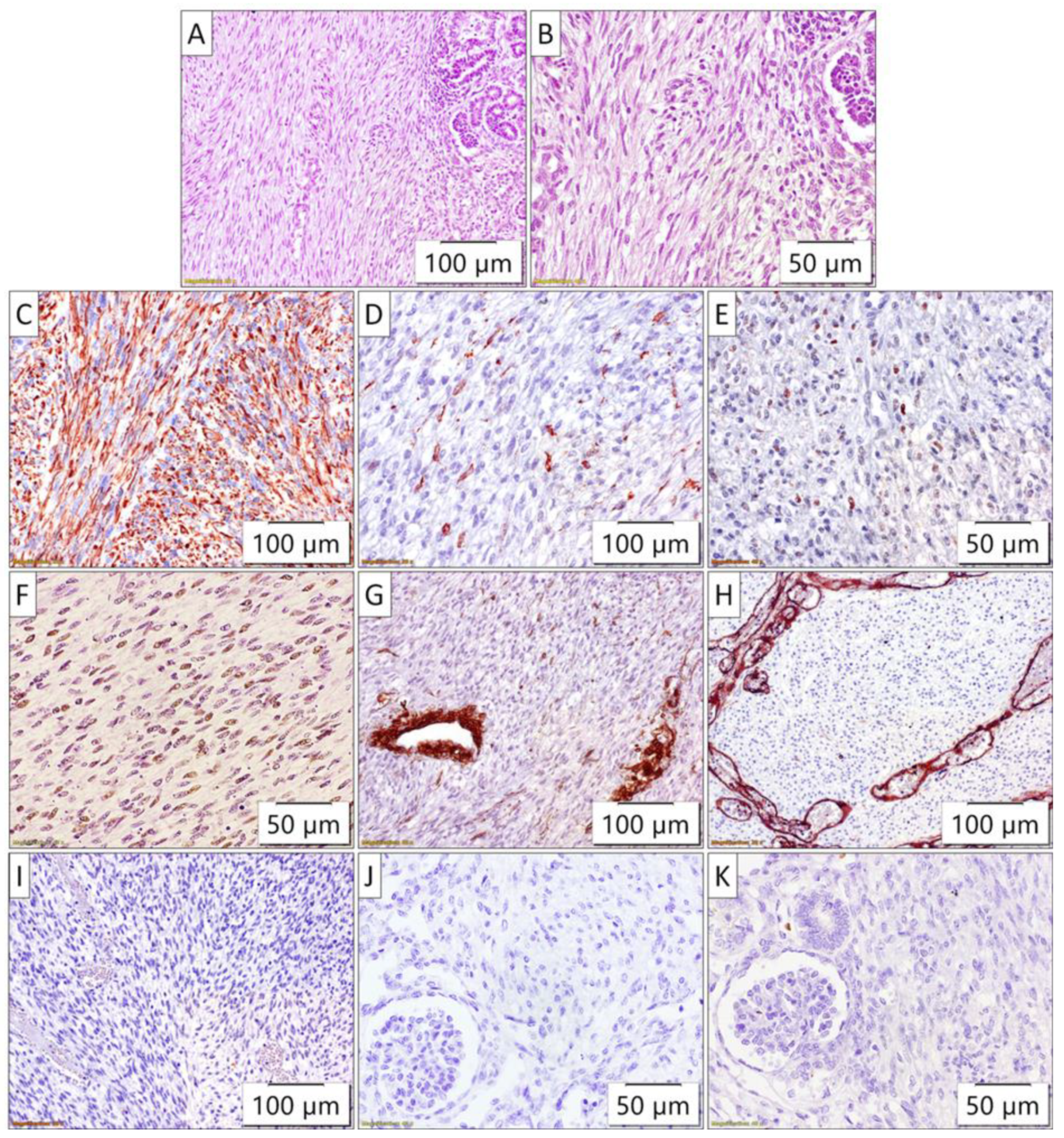

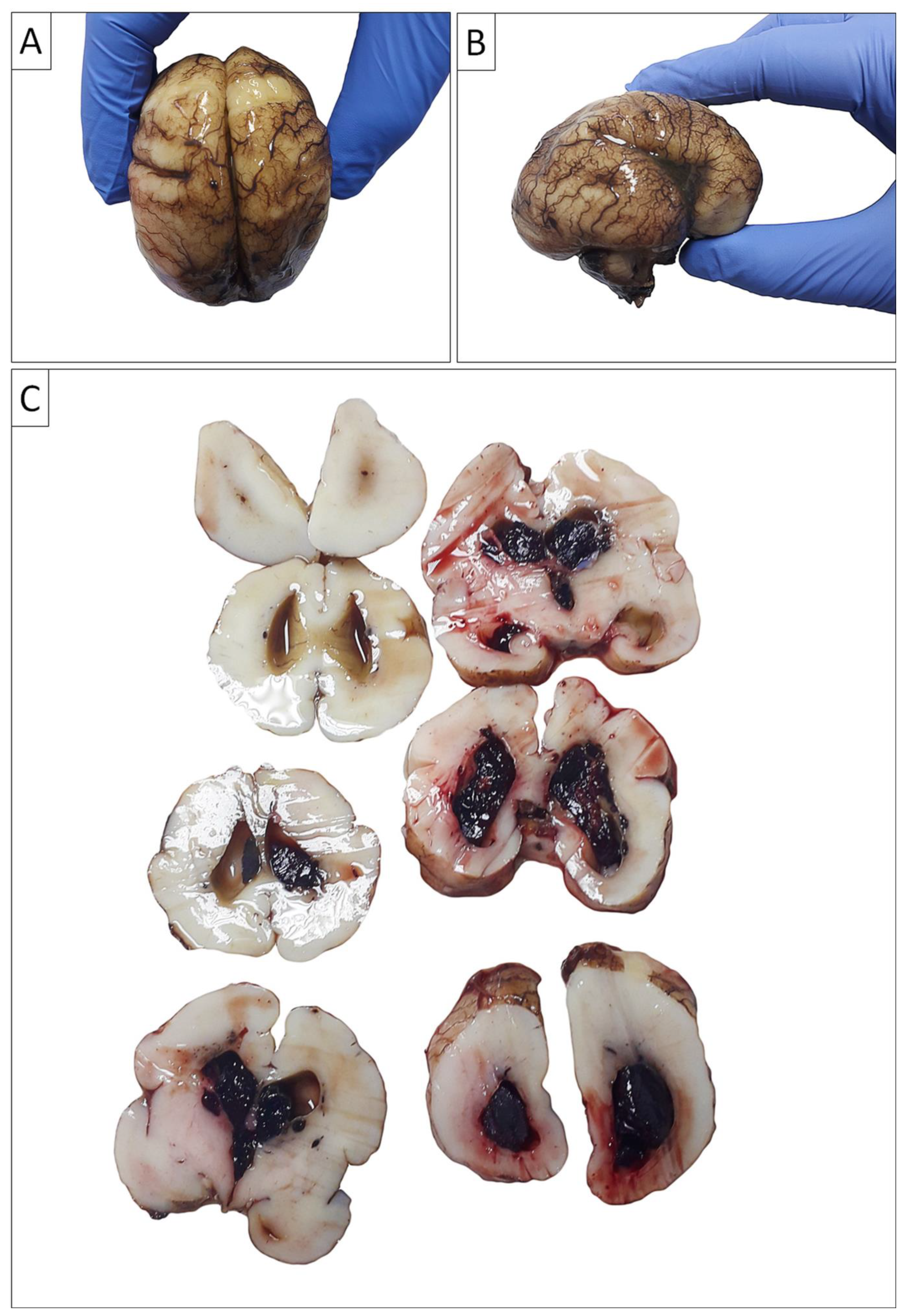

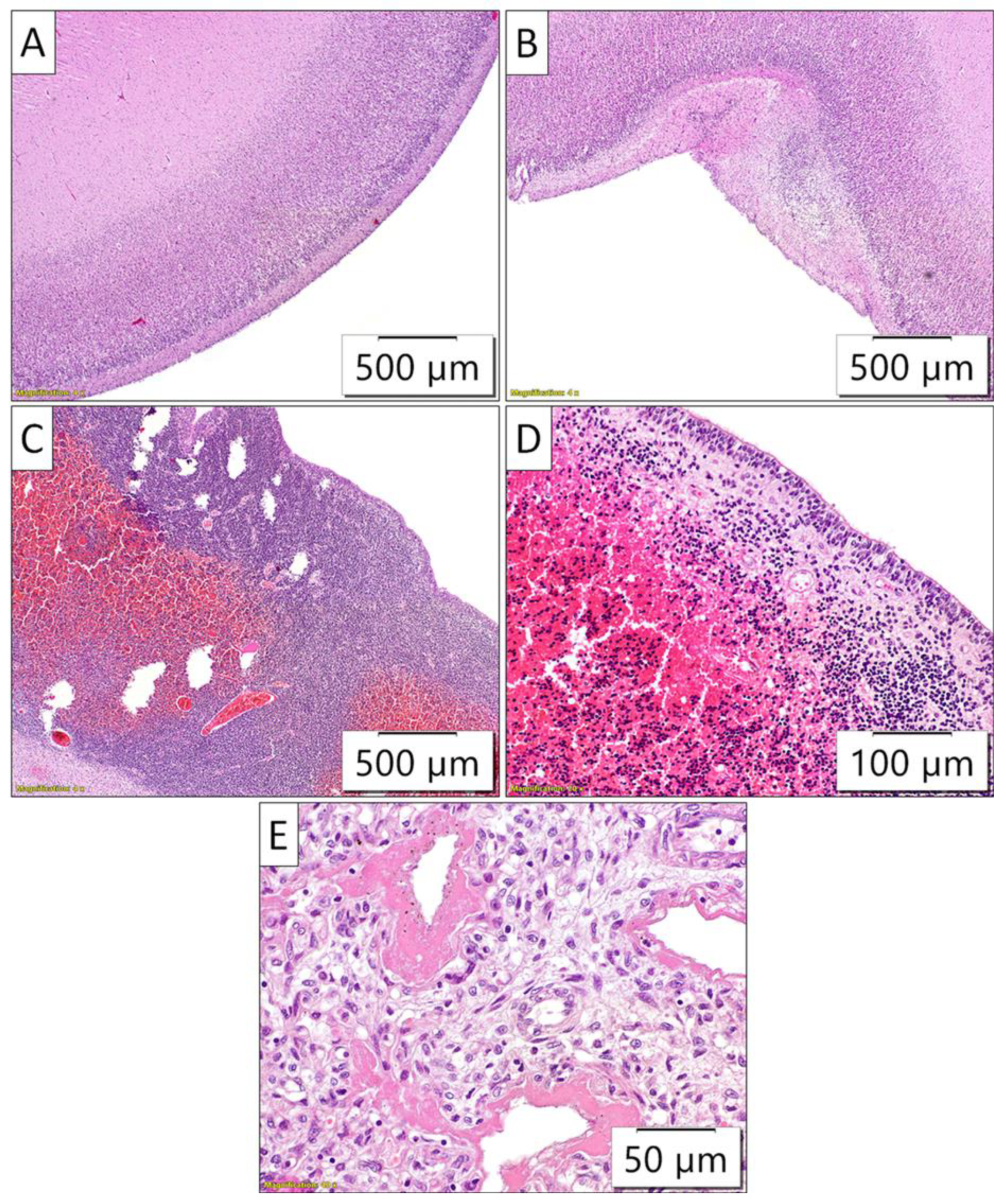

2.2. Autopsy Findings

2.3. Genetic Testing

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Z.P.; LI, K.; Dong, K.R.; Xiao, X.M.; Zheng, S. Congenital Mesoblastic Nephroma: Clinical Analysis of Eight Cases and a Review of the Literature. Oncol Lett 2014, 8, 2007–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooskens, S.L.; Houwing, M.E.; Vujanic, G.M.; Dome, J.S.; Diertens, T.; Coulomb-l’Herminé, A.; Godzinski, J.; Pritchard-Jones, K.; Graf, N.; van den Heuvel-Eibrink, M.M. Congenital Mesoblastic Nephroma 50 Years after Its Recognition: A Narrative Review. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2017, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittle, S.; Gosain, A.; Scott Brown, P.Y.; Debelenko, L.; Raimondi, S.; Wilimas, J.A.; Jenkins, J.J.; Davidoff, A.M. Regression of a Congenital Mesoblastic Nephroma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2010, 55, 364–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyaltın, E.; Alaygut, D.; Alparslan, C.; Özdemir, T.; Çamlar, S.A.-; Mutlubaş, F.; Kasap-Demir, B.; Yavaşcan, Ö. A Rare Cause of Neonatal Hypertension: Congenital Mesoblastic Nephroma. Turk J Pediatr 2018, 60, 198–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, H.S.; Jung, E.; Lee, P.R.; Lee, I.S.; Kim, A.; Kim, J.K.; Cho, K.S.; Nam, J.H. Prenatal Detection of Mesoblastic Nephroma by Sonography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2002, 19, 197–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongsong, T.; Palangmonthip, W.; Chankhunaphas, W.; Luewan, S. Prenatal Course and Sonographic Features of Congenital Mesoblastic Nephroma. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022, 12, 1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, I.; Shoshani, G.; Ben-Harus, E.; Sujov, P. Prenatal Diagnosis of Congenital Mesoblastic Nephroma. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2002, 19, 209–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalice, A.; Parisi, P.; Nicita, F.; Pizzardi, G.; Del Balzo, F.; Iannetti, P. Neuronal Migration Disorders: Clinical, Neuroradiologic and Genetics Aspects. Acta Paediatr 2009, 98, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friocourt, G.; Marcorelles, P.; Saugier-Veber, P.; Quille, M.-L.; Marret, S.; Laquerrière, A. Role of Cytoskeletal Abnormalities in the Neuropathology and Pathophysiology of Type I Lissencephaly. Acta Neuropathol 2011, 121, 149–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonni, G.; Pattacini, P.; Bonasoni, M.P.; Araujo Júnior, E. Prenatal Diagnosis of Lissencephaly Type 2 Using Three-Dimensional Ultrasound and Fetal MRI: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet 2016, 38, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolande, R.P.; Brough, A.J.; Izant, R.J. Congenital Mesoblastic Nephroma of Infancy. A Report of Eight Cases and the Relationship to Wilms’ Tumor. Pediatrics 1967, 40, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furtwaengler, R.; Reinhard, H.; Leuschner, I.; Schenk, J.P.; Goebel, U.; Claviez, A.; Kulozik, A.; Zoubek, A.; von Schweinitz, D.; Graf, N.; et al. Mesoblastic Nephroma--a Report from the Gesellschaft Fur Pädiatrische Onkologie Und Hämatologie (GPOH). Cancer 2006, 106, 2275–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mata, R.P.; Alves, T.; Figueiredo, A.; Santos, A. Prenatal Diagnosis of Congenital Mesoblastic Nephroma: A Case with Poor Prognosis. BMJ Case Rep 2019, 12, e230297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, M.; Yang, F.; Huang, H.; Zhang, H.; Han, C.; Sun, N. Prenatal Diagnosis of Fetal Congenital Mesoblastic Nephroma by Ultrasonography Combined with MR Imaging. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021, 100, e24034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.; Kim, M.-J.; Im, Y.-J.; Park, K.-I.; Lee, M.-J. Cellular Mesoblastic Nephroma with Liver Metastasis in a Neonate: Prenatal and Postnatal Diffusion-Weighted MR Imaging. Korean J Radiol 2013, 14, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schild, R.L.; Plath, H.; Hofstaetter, C.; Hansmann, M. Diagnosis of a Fetal Mesoblastic Nephroma by 3D-Ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2000, 15, 533–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.H.; Kim, Y.H.; Cho, M.K.; Kim, K.M.; Ha, J.A.; Joo, E.H.; Kim, S.M.; Song, T.-B. A Case of Fetal Congenital Mesoblastic Nephroma with Oligohydramnios. J Korean Med Sci 2007, 22, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.G. dos; Carvalho, J. de S.R. de; Reis, M.A.; Sales, R.L.J.B. Cellular Congenital Mesoblastic Nephroma: Case Report. J Bras Nefrol 2011, 33, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson-Bell, T.; Newberry, D.M.; Jnah, A.J.; DeMeo, S.D. Congenital Mesoblastic Nephroma Presenting With Refractory Hypertension in a Premature Neonate: A Case Study. Neonatal Netw 2017, 36, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anakievski, D.; Ivanova, P.; Kitanova, M. Laparoscopic Management of Congenital Mesoblastic Nephroma- Case Report. Urol Case Rep 2019, 26, 100979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, A.Y.; Kim, J.-S.; Choi, S.-J.; Oh, S.-Y.; Roh, C.-R.; Kim, J.-H. Prenatal Diagnosis of Congenital Mesoblastic Nephroma. Obstet Gynecol Sci 2015, 58, 405–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simkhada, A.; Paudel, R.; Sharma, N. Congenital Mesoblastic Nephroma: A Case Report. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc 2023, 61, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Al-Kzayer, L.F.Y.; Sarsam, S.N.; Chen, L.; Saeed, R.M.; Ali, K.H.; Nakazawa, Y. Cellular Congenital Mesoblastic Nephroma Detected by Prenatal MRI: A Case Report and Literature Review. Transl Pediatr 2022, 11, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, S.; Gao, Y.; Liang, L.; Yang, H. Prenatal Diagnosis and Postnatal Management of Congenital Mesoblastic Nephroma: A Case Report and Literature Review. Front Pediatr 2022, 10, 1040304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei L, Stohr BA, Berry S, Lockwood CM, Davis JL, Rudzinski ER, Kunder CA. Recurrent EGFR alterations in NTRK3 fusion negative congenital mesoblastic nephroma. Pract Lab Med. 2020 May 16;21:e00164. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Amatu, A.; Sartore-Bianchi, A.; Bencardino, K.; Pizzutilo, E.G.; Tosi, F.; Siena, S. Tropomyosin Receptor Kinase (TRK) Biology and the Role of NTRK Gene Fusions in Cancer. Ann Oncol 2019, 30, viii5–viii15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tognon, C.; Knezevich, S.R.; Huntsman, D.; Roskelley, C.D.; Melnyk, N.; Mathers, J.A.; Becker, L.; Carneiro, F.; MacPherson, N.; Horsman, D.; et al. Expression of the ETV6-NTRK3 Gene Fusion as a Primary Event in Human Secretory Breast Carcinoma. Cancer Cell 2002, 2, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majewska, H.; Skálová, A.; Stodulski, D.; Klimková, A.; Steiner, P.; Stankiewicz, C.; Biernat, W. Mammary Analogue Secretory Carcinoma of Salivary Glands: A New Entity Associated with ETV6 Gene Rearrangement. Virchows Arch 2015, 466, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeman-Neill, R.J.; Kelly, L.M.; Liu, P.; Brenner, A.V.; Little, M.P.; Bogdanova, T.I.; Evdokimova, V.N.; Hatch, M.; Zurnadzy, L.Y.; Nikiforova, M.N.; et al. ETV6-NTRK3 Is a Common Chromosomal Rearrangement in Radiation-Associated Thyroid Cancer. Cancer 2014, 120, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachl, M.; Arul, G.S.; Jester, I.; Bowen, C.; Hobin, D.; Morland, B. Congenital Mesoblastic Nephroma: A Single-Centre Series. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2020, 102, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, F.; Griffiths, P.D. In Utero MR Imaging in Fetuses at High Risk of Lissencephaly. Br J Radiol 2017, 90, 20160902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).