1. Introduction

Congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT) comprise a heterogeneous spectrum of malformations and are among the most frequently detected anomalies during pregnancy—accounting for approximately 20–30% of all prenatal diagnoses [

1]. They occur in an estimated 3–7 per 1,000 live births and are responsible for 40–50% of pediatric nephropathies. These conditions arise from disruptions in the normal embryonic development of the renal system.

CAKUT includes a wide variety of anatomical defects, each with differing severity and clinical implications [

2]. Early prenatal suspicion and diagnosis are critical, as they allow clinicians to prepare individualized postnatal management plans that take into account the fetus or newborn’s condition and the balance between risks and benefits of potential interventions. This tailored approach can improve long-term outcomes and reduce complications.

A clear and comprehensive classification of CAKUT is essential to guide both research and clinical care. Malformations may result from defects in renal parenchymal development, abnormalities in embryonic migration or fusion, and anomalies of the collecting system, bladder, or ureters [

3]. While no single diagnostic tool can identify every type of renal malformation and its sequelae, prenatal ultrasonography—especially from the second trimester onward—remains the cornerstone of early detection. Prompt identification enables the appropriate use of complementary tests, such as Doppler ultrasonography, voiding cystourethrography, or fetal MRI, and facilitates the design of individualized postnatal follow-up protocols, which may include repeated imaging, prophylactic antibiotics, or surgical intervention [

4].

The risk profile for CAKUT is influenced by maternal, genetic, and environmental factors [

5]. These include maternal comorbidities, family history of renal or other congenital anomalies, advanced maternal age, environmental toxin exposure, certain medications, genitourinary infections, and chronic conditions such as pregestational or gestational diabetes [

6]. Such factors highlight the importance of comprehensive prenatal screening strategies.

Early identification of CAKUT not only allows clinicians to anticipate potential complications at birth or during infancy, but also enables timely planning for specialized neonatal care. Structured postnatal management—including optimal imaging schedules, tailored monitoring, and timely interventions—can significantly improve patient outcomes [

7,

8].

Objective

The aim of this study was to describe prenatal ultrasound findings in fetal renal malformations and to evaluate their correlation with postnatal confirmation [

9]. We also sought to assess the diagnostic value of prenatal ultrasonography and to emphasize its role in optimizing neonatal care and long-term health outcomes for patients with CAKUT [

10,

11]. The results are particularly relevant to healthcare systems in Mexico and other regions with similar infrastructure and resource limitations, as they demonstrate the feasibility and effectiveness of routine prenatal ultrasound in such settings.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Population

This case series was conducted between January 2022 and December 2024 at the Hospital de Gineco-Pediatría No. 7, in Cancún, Quintana Roo, Mexico. Eligible participants were neonates with prenatal suspicion of renal or urinary tract anomalies detected on fetal ultrasound and postnatally confirmed through renal imaging and evaluation by pediatric nephrology or urology teams.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion Criteria:

Neonates born at the study hospital during the study period.

Documented prenatal ultrasound diagnosis of CAKUT.

Complete clinical records, including postnatal imaging and follow-up.

Exclusion Criteria:

Births outside the study hospital.

Absence of prenatal CAKUT diagnosis.

Lack of postnatal confirmatory imaging.

Missing follow-up data.

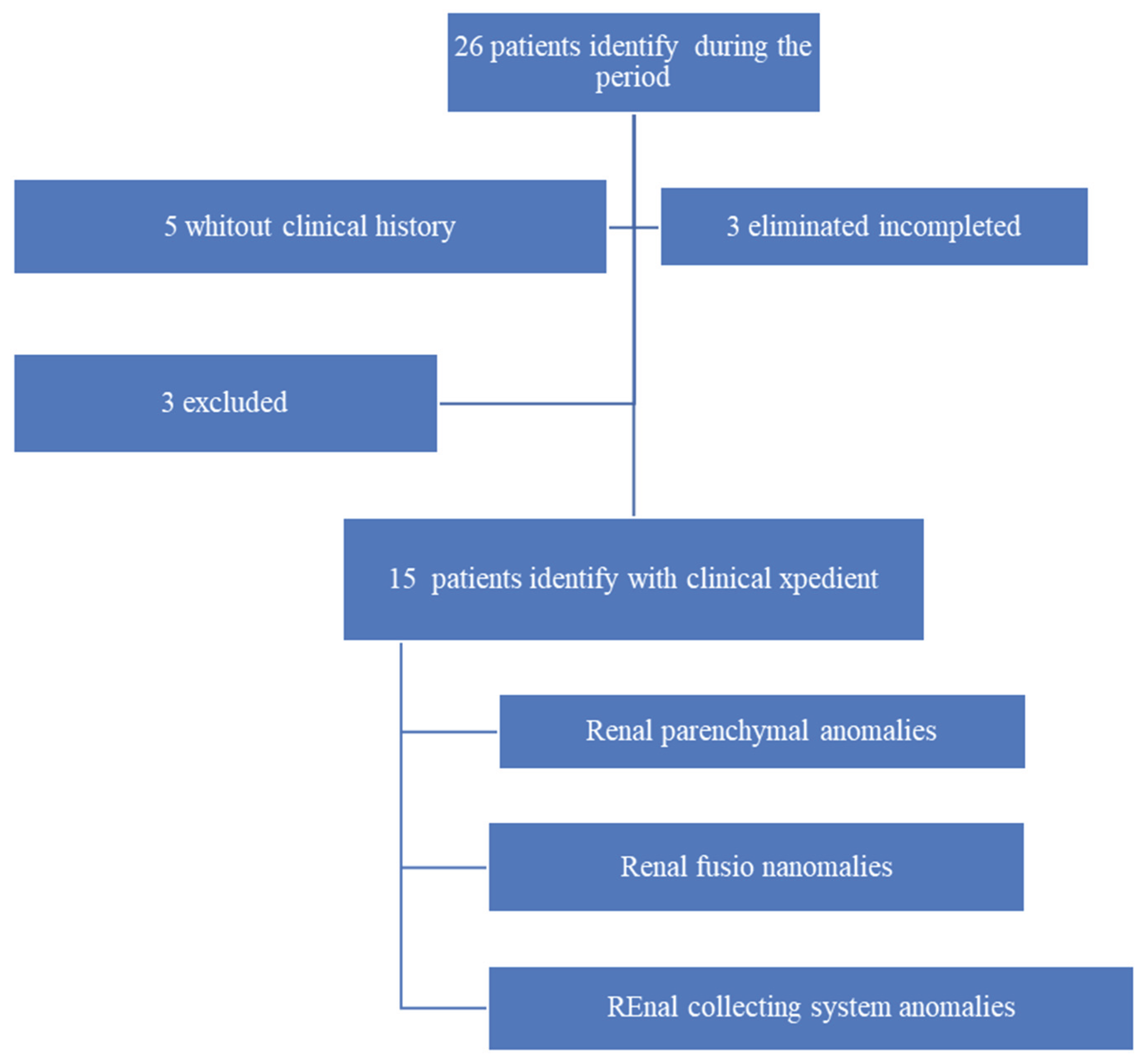

From the initial 26 neonates identified with renal malformations during the study period, 21 had complete medical records. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, three patients without a documented prenatal diagnosis and three lacking postnatal follow-up at the study center were excluded. This left a final study cohort of 15 patients for analysis (

Figure 1).

Study flow diagram illustrating excluded and eliminated patients due to missing medical records, and the composition of the different groups of renal malformations.

Main Variables and Data Collection

The primary dependent variable was the presence of renal malformations, classified into six diagnostic categories:

Renal parenchymal anomalies.

Abnormalities of embryonic migration.

Renal fusion anomalies.

Collecting system anomalies.

Bladder malformations.

Urethral malformations.

The main independent variable was the prenatal suspicion of any of these anomalies based on ultrasonographic findings, recorded dichotomously as present or absent.

Additional maternal variables included age, obesity, and preexisting or gestational diabetes. Fetal variables included sex, gestational age at birth, and amniotic fluid characteristics.

Data were collected through a comprehensive review of both paper-based and electronic medical records, including admission notes, imaging reports, and specialist evaluations. All extracted information was entered into a Microsoft Excel® database, with variables recoded for statistical processing. Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics®.

To ensure accuracy, a rigorous data quality process was implemented, involving cross-verification of entries to identify and correct potential transcription or interpretation errors. All records were anonymized to protect patient confidentiality, and ethical standards were upheld throughout the study. Descriptive statistical methods were applied for analysis.

Ethical Considerations

This study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee and the Health Research Committee of the Federal Commission for the Protection against Sanitary Risk (COFEPRIS) under registration number R-2025-2301-007. All procedures adhered to the ethical principles set forth in the 75th World Medical Assembly (Helsinki, Finland, October 2024) and complied with the standards of the Reglamento de la Ley General de Salud en Materia de Investigación en Salud, Title II, Chapter I, Articles 16 and 17, Section I (research without risk).

No clinical interventions or modifications to patient management were made, and there was no direct interaction with study participants.

Ultrasound Protocol and Diagnostic Criteria

Prenatal ultrasound examinations followed standardized protocols outlined by the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology (ISUOG) guidelines. Each patient underwent at least two scans—between 17–20 weeks and 30–32 weeks of gestation—to optimize anomaly detection.

The Fetal Renal System Was Systematically Assessed for:

Diagnostic Criteria Included:

Renal pelvis dilation >4 mm in the second trimester or >7 mm in the third trimester.

Detection of cystic formations.

Non-visualization or hypoplasia of renal structures consistent with agenesis or dysplasia.

3. Results

A retrospective review identified 26 patients with prenatal suspicion of renal malformations between January 2022 and December 2024. Complete medical records were available for 21 cases (80.76%).

Following application of the data collection protocol, three patients without documented prenatal diagnosis and three lacking postnatal follow-up at the study center were excluded. The final study cohort comprised 15 neonates with renal malformations suspected prenatally and confirmed postnatally.

The demographic and clinical characteristics of these patients are summarized in

Table 1.

Among maternal risk factors, age is considered high-risk when below 16 or above 35 years. In our cohort of 15 cases, no mother was younger than 16 years; six mothers (40%) were over 35 years of age, while the remaining nine (60%) were between 20 and 34 years. Chronic diabetes and gestational diabetes were also assessed, but no cases were identified in this population. Regarding nutritional status, six mothers (40%) had grade I obesity and two (13%) had grade II obesity (see

Table 2).

To meet the inclusion criteria, patients with a prenatal ultrasound diagnosis of renal malformations were identified. Most cases were detected after 24 weeks of gestational age. Amniotic fluid volume was reported as normal in 73.3% of cases (n = 11), while 26.7% (n = 4) presented with oligohydramnios (see

Table 3).

The group of renal anomalies most frequently diagnosed were anomalies of the renal collecting system, with 10 cases, followed by renal fusion anomalies, with 1 case. Among the renal malformations most commonly identified were hydronephrosis and renal ectasia, each with a total of 4 cases. Less frequently observed were two pathologies: renal dysplasia and horseshoe kidneys, with 1 case each.

The study identified 7 possible types of renal malformations: 4 cases (25.2%) of hydronephrosis, 4 cases (25.2%) of renal ectasia, 2 cases (12.6%) of renal agenesis, 2 cases (12.6%) of polycystic kidney disease, 2 cases (12.6%) of duplicated collecting system, and the remaining 12.6% comprised renal dysplasia and horseshoe kidneys, with 1 case each (6.3% each). (

Table 4)

All mothers of patients diagnosed with CAKUT had adequate prenatal care, which allowed for timely identification of the anomalies. Patients with confirmed renal malformations are currently under follow-up and management by both pediatrics and pediatric surgery, according to their individual needs.

4. Discussion

Prenatal ultrasound is a fundamental, non-invasive diagnostic tool for identifying congenital urinary tract anomalies. It offers multiple advantages, including early anomaly detection, timely planning of medical interventions, specialized pregnancy monitoring, and informed postnatal management decisions. Numerous studies have shown that prenatal diagnosis improves neonatal outcomes, reduces morbidity, and supports better long-term prognoses. These findings underscore the importance of comprehensive prenatal care and routine ultrasound screening for optimal fetal development monitoring.

In this study, 15 cases of prenatally diagnosed renal anomalies were analyzed. Hydronephrosis and renal ectasia were the most prevalent findings, each accounting for 25.2% of cases. These results are consistent with international literature, which reports that approximately half of all prenatal renal anomalies correspond to fetal hydronephrosis. Similarly, a Mexican study identified hydronephrosis as the most commonly detected anomaly on prenatal ultrasound, highlighting the value of advanced prenatal imaging. Early detection has a significant impact on postnatal management; for example, one study reported that 60% of prenatally diagnosed cases required prolonged hospitalization, and 27% necessitated surgical intervention, emphasizing the need for careful prenatal and postnatal monitoring.

Prenatal ultrasound is critical for detecting complex congenital renal malformations, including bilateral renal agenesis, multicystic dysplastic kidney (MCDK), and associated syndromes that often present with complex phenotypes. Accurate prenatal imaging allows timely interventions and informed parental counseling regarding prognosis and potential risks. Large population studies have demonstrated a high prevalence of renal anomalies identified via routine prenatal ultrasound. For example, among 709,030 births, 1,130 cases of prenatal renal malformations were detected, with an 81.8% detection rate and pregnancy termination occurring in 29% of affected cases. Additionally, 55–60% of fetuses presenting with hyperechoic kidneys have identifiable genetic conditions, underscoring the importance of integrating genetic counseling and testing into clinical practice.

The intersection of prenatal imaging and renal anomaly diagnosis highlights the critical role of early detection in maternal-fetal medicine. Advances in prenatal imaging continue to enhance the identification and understanding of congenital anomalies, improve genetic counseling, and support parental decision-making. Comprehensive care for fetuses with renal malformations requires the integration of imaging, genetic investigations, and multidisciplinary management to optimize outcomes.

Congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT) remain a leading cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality and are frequently associated with non-renal congenital disorders in up to 30% of cases. CAKUT is also a primary contributor to pediatric chronic kidney disease (CKD), particularly in severe malformations. Early diagnosis is therefore crucial. Fetal ultrasound is considered the primary diagnostic modality, with at least two scans recommended at 17–20 and 30–32 weeks of gestation to detect both overt and subtle anomalies. While ultrasound is safe, non-invasive, and widely accessible, its limitations in detecting certain pathologies highlight the complementary role of fetal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), especially for complex morphologic anomalies or suspected chromosomal disorders.

Renal pelvis dilatation is a common prenatal finding and may indicate obstructive uropathy; however, most cases are mild and do not require aggressive intervention. More complex diagnostic scenarios, such as hyperechogenic or cystic kidneys, require careful assessment of family history and amniotic fluid volume. Accurate evaluation often necessitates a multidisciplinary approach, involving fetal medicine specialists, neonatologists, and genetic counselors, particularly in syndromic cases. Early surgical intervention is planned according to clinical severity and associated complications. This collaborative approach, combined with advanced imaging, optimizes outcomes for infants with CAKUT.

This study’s main limitation is its small sample size, which may affect the generalizability of results. Additionally, certain maternal and fetal risk factor data were unavailable, limiting the analysis of their influence on fetal renal malformations. Importantly, there are no prior studies in Quintana Roo, Mexico, specifically addressing prenatal ultrasound detection of renal anomalies, making these findings particularly valuable for regional epidemiology.

Prenatal ultrasound examinations followed ISUOG guidelines, including at least two scans between 17–20 and 30–32 weeks of gestation. The fetal renal system was systematically evaluated for size, echogenicity, pelvic dilation, and associated abnormalities. Diagnostic criteria included renal pelvis dilatation greater than 4 mm in the second trimester or 7 mm in the third trimester, presence of cystic structures, and absent or hypoplastic kidneys consistent with agenesis or dysplasia. All confirmed cases were referred for multidisciplinary postnatal follow-up, including pediatric nephrology and surgery teams, with imaging confirmation and renal function assessment.

The findings of this study are representative of conditions in many public hospitals in Mexico and other low- and middle-income countries, where resource availability and clinical workflows are similar. The successful implementation of routine prenatal ultrasound for CAKUT detection demonstrates the feasibility and effectiveness of such programs in resource-constrained settings. These results support expanding access to ultrasound services, training qualified personnel, and integrating prenatal imaging into national maternal health guidelines to ensure early diagnosis and improve outcomes.

5. Conclusions

Prenatal ultrasound is a highly effective, non-invasive tool for the early detection of fetal renal malformations, enabling timely postnatal management and multidisciplinary care. This study reinforces findings from prior Mexican and international research, highlighting hydronephrosis and renal ectasia as the most prevalent anomalies and identifying male sex as a notable risk factor for CAKUT.

Advances in imaging, combined with structured prenatal care and postnatal follow-up, significantly improve the prognosis for infants with renal anomalies. Multidisciplinary collaboration and regional implementation of prenatal screening protocols are essential for optimizing outcomes. Future studies with larger prospective cohorts are needed to further elucidate risk factors, improve early detection, and guide interventions. This research provides a foundation for enhancing prenatal diagnostic capabilities, shaping healthcare policies, and improving neonatal outcomes in Mexico and comparable global contexts.

Acknowledgments

We thank all those who allowed access to clinical records, both physical and electronic, as well as translation websites that aided in English-Spanish interpretation.

Author Contributions

Rodolfo Bárcenas-Contreras: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Writing—original draft. Perla Abriyalib Cleto-García: Methodology, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing—review & editing. Grecia Ruiz-Coronel: Data curation, Investigation, Validation. Omar Ernesto Rojas-Pacheco: Supervision, Project administration, Resources. María Valeria Jiménez-Baez: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—review & editing, Corresponding author. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board Mexican Institute Social Security in Quintana Roo.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Koenigbauer, J.T. , et al., Spectrum of congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT) including renal parenchymal malformations during fetal life and the implementation of prenatal exome sequencing (WES). Arch Gynecol Obstet, 2024. 309(6): p. 2613-2622. [CrossRef]

- Karim JN, Di Mascio D, Roberts N, Papageorghiou AT; ACCEPTS study. Detection of non-cardiac fetal abnormalities on ultrasound at 11-14 weeks: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2024 Jul;64(1):15-27. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li C, Ma Y. A meta-analysis of pregnancy outcomes in the diagnosis of isolated foetal renal parenchyma by prenatal ultrasonography. Technol Health Care. 2023;31(4):1393-1405. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiesel, A. , et al., Prenatal detection of congenital renal malformations by fetal ultrasonographic examination: an analysis of 709,030 births in 12 European countries. Eur J Med Genet, 2005. 48(2): p. 131-44. [CrossRef]

- Deng L, Liu Y, Yuan M, Meng M, Yang Y, Sun L. Prenatal diagnosis and outcome of fetal hyperechogenic kidneys in the era of antenatal next-generationsequencing. Clin Chim Acta. 2022 Mar 1;528:16-28. https://doi/. Epub 2022 Jan 20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabezalí Barbancho D, Gómez Fraile A. Anomalías congénitas del riñón y del tracto urinario. An Pediatr Contin [Internet]. 2013 [Consultado 22 Sept 2024];11(6):325–32. Disponible en:. [CrossRef]

- Liu L, Li J, Li Y, Li H, Yang B, Fan H, Wang J, Gu Y, Yu H, Bai M, Yu T, Cui S, Cheng G, Ren C. Genetic diagnosis of common fetal renal abnormalities detected on prenatal ultrasound. Prenat Diagn. 2022 Jun;42(7):894-900. Epub 2022 May 5. PMID: 35478332. [CrossRef]

- Basabe Ochoa AM, Troche Hermosilla AV, Martínez Pico M. Epidemiología de las anomalías congénitas del riñón y tracto urinario en pacientes pediátricos en un Hospital de Referencia. DEL NAC [Internet]. 2020 [Consultado 22 Sept 2024];12(2):28–37. Disponible en:. [CrossRef]

- Su J, Qin Z, Fu H, Luo J, Huang Y, Huang P, Zhang S, Liu T, Lu W, Li W, Jiang T, Wei S, Yang S, Shen Y. Association of prenatal renal ultrasound abnormalities with pathogenic copy number variants in a large Chinese cohort. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2022 Feb;59(2):226-233. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bascietto F, Khalil A, Rizzo G, Makatsariya A, Buca D, Silvi C, Ucci M, Liberati M, Familiari A, D’Antonio F. Prenatal imaging features and postnatal outcomes of isolated fetal duplex renal collecting system: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prenat Diagn. 2020 Mar;40(4):424-431. Epub 2020 Jan 28. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Olmedo JL, Gómez-Rodríguez G, Flores-Amador TM, Cano-Rodríguez MT, León-Verdín MG. Diagnóstico prenatal de malformaciones del tracto urinario: evaluación posnatal y resultado clínico. Revista Perinatología y Reproducción Humana [Internet]. 2023 [Consultado 22 Sept 2024]; 37(2). Disponible en:. [CrossRef]

- Murugapoopathy V, Gupta IR. A primer on congenital anomalies of the kidneys and urinary tracts (CAKUT). Clin J Am Soc Nephrol [Internet]. 2020 [Consultado 22 Sept 2024];15(5):723–31. Disponible en:. [CrossRef]

- Segura-Grau A, Herzog R, Díaz-Rodriguez N, Segura-Cabral JM. Ecografía del aparato urinario. Semergen [Internet]. 2016 [Consultado 19 Sept 2024]; 42(6):388–94. Disponible en:. [CrossRef]

- Romero Sala, FJ. Anomalías congénitas del riñón y del tracto urinario (CAKUT: Congenital Anomalies of the Kidney and Urinary Tract). Revisión. Vox Paediatr. 2019 [Consultado 21 Oct 2024]; 26(1):97–109. Disponible en: https://spaoyex.es/sites/default/files/vp_26_1_18.pdf.

- Atehortúa Baena P, Mejia Mesa S, Arango Gutierrez L, et al. Frecuencia de malformaciones congénitas renales y del tracto urinario y su asociación con factores maternos y del neonato. Pediatría [Internet]. 2021 [Consultado 22 Sept 2024]; 54(2):46–53. Disponible en:. [CrossRef]

- Sanna-Cherchi S, Westland R, Ghiggeri GM, et al. Genetic basis of human congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. J Clin Invest [Internet]. 2018 [Consultado 23 Sept 2024]; 128(1):4–15. Disponible en:. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Pérez M, Ochoa Gibert Y, Vela Caravia I, et al. Tratamiento de la duplicidad ureteral y otros defectos congénitos urinarios asociados. Rev Cub Urol. 2015; 4(2): e152b. Disponible en: https://files.sld.cu/urologia/files/2016/04/rcu152b.pdf.

- Mallik M, Watson AR. Antenatally detected urinary tract abnormalities: more detection but less action. Pediatr Nephrol [Internet]. 2008; 23(6):897–904. Disponible en:. [CrossRef]

- Nicolaou N, Renkema KY, Bongers EMHF, et al. Genetic, environmental, and epigenetic factors involved in CAKUT. Nat Rev Nephrol [Internet]. 2015;11(12):720–31. Disponible en:. [CrossRef]

- Salomon LJ, Alfirevic Z, Berghella V, et al. Practice guidelines for performance of the routine mid-trimester fetal ultrasound scan. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol [Internet]. 2011;37(1):116–26. Disponible en:. [CrossRef]

- Lee RS, Cendron M, Kinnamon DD, Nguyen HT. Antenatal hydronephrosis as a predictor of postnatal outcome: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics [Internet]. 2006;118(2):586–93. Disponible en:. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen HT, Herndon CDA, Cooper C, et al. The Society for Fetal Urology consensus statement on the evaluation and management of antenatal hydronephrosis. J Pediatr Urol [Internet]. 2010;6(3):212–31. Disponible en:. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience: Summary. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2018. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.

- Secretaría de Salud (México). NORMA Oficial Mexicana NOM-007-SSA2-2016, Para la atención de la mujer durante el embarazo, parto y puerperio, y de la persona recién nacida. Diario Oficial de la Federación. 2016 abr 7. Disponible en: https://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5432289&fecha=07/04/2016#gsc.tab=0.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).