Submitted:

09 December 2024

Posted:

10 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

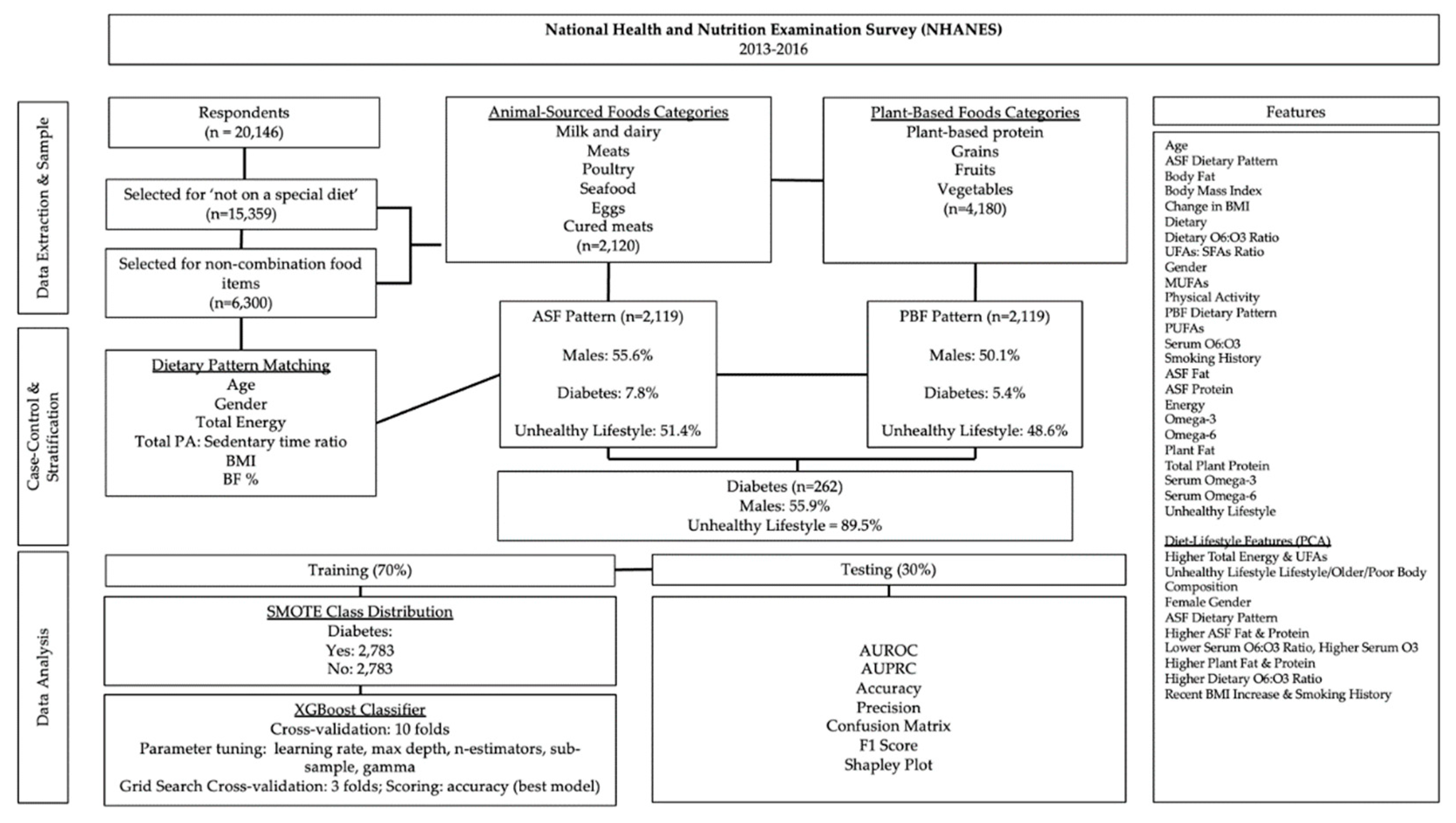

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data and Sample Extraction

2.2. Dietary Group Matching

2.3. Statistical Analyses

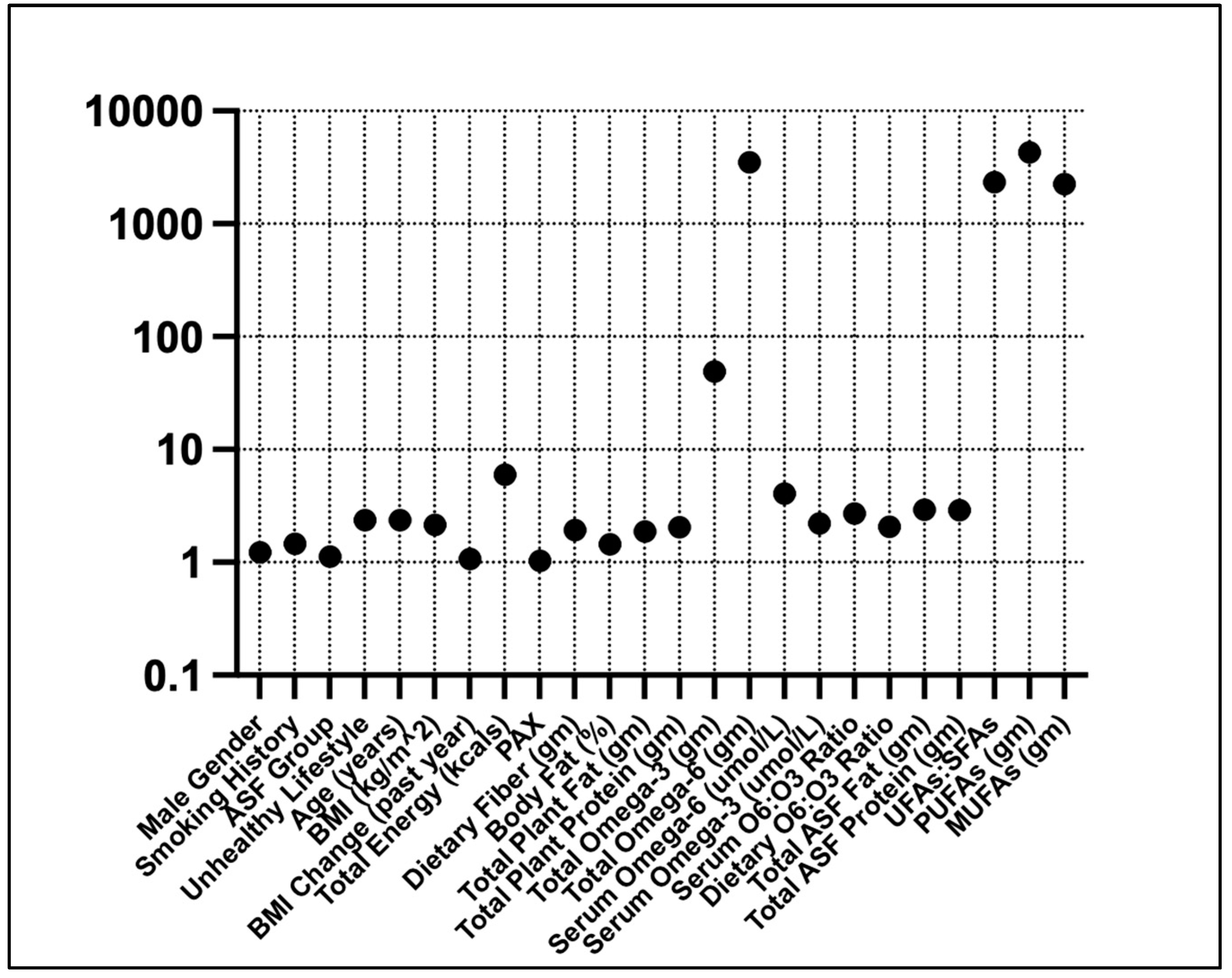

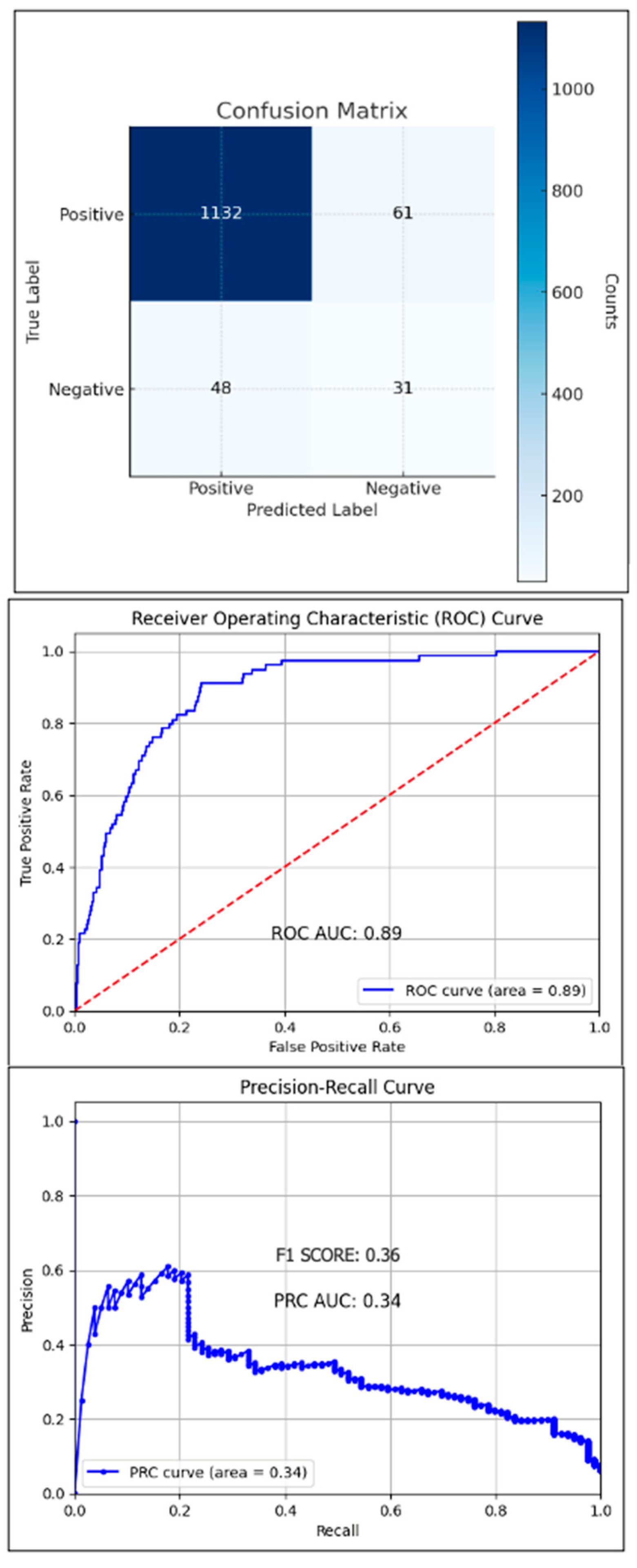

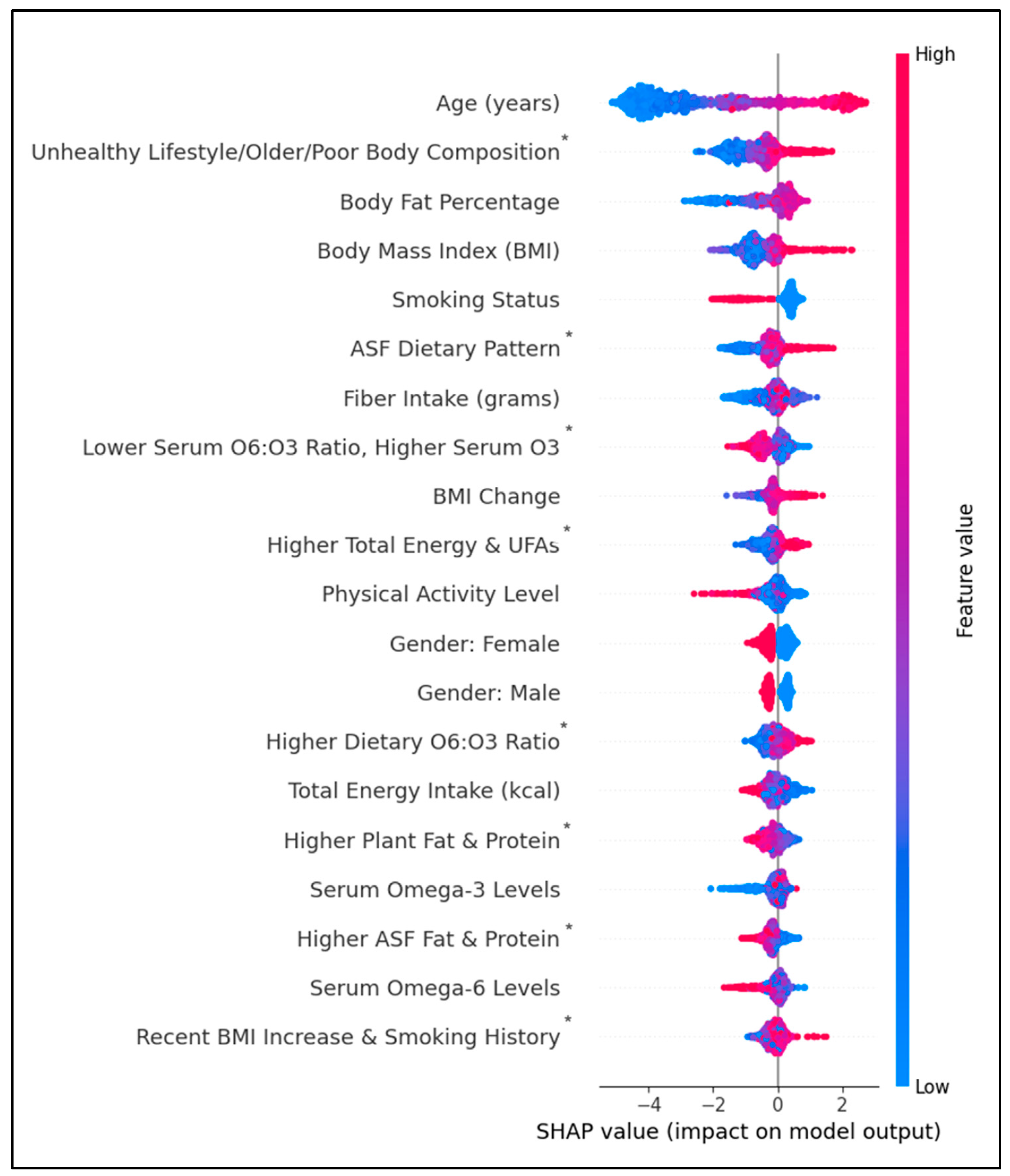

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASFs | animal-sourced foods |

| AUPRC | area under the precision-recall curve |

| AUROC | area under the receiver operating characteristic curve |

| BMI | body mass index |

| CVD | cardiovascular disease |

| FAs | fatty acids |

| HEI | healthy eating index |

| HS-CRP | high-sensitivity c-reactive protein |

| ML | machine learning |

| MUFAs | monounsaturated fatty acids |

| PA | physical activity |

| PAX | ratio of total physical activity to sedentary time |

| PBFs | Plant-based foods |

| PUFAs | polyunsaturated fatty acids |

| RCT | randomized controlled trial |

| SFAs | saturated fatty acids |

| T2D | Type 2 diabetes |

| ω3FAs | dietary omega-3 fatty acids |

| ω6FAs | dietary omega-6 fatty acids |

| ω6FAs | ω3FAs ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids |

| UFAs | unsaturated fatty acids |

References

- Petersen KS, Flock MR, Richter CK, Mukherjea R, Slavin JL, Kris-Etherton PM. Healthy dietary patterns for preventing cardiometabolic disease: the role of plant-based foods and animal products. Current Developments in Nutrition. 2017 Dec 1;1(12):cdn-117.

- Zhao B, Gan L, Graubard BI, Männistö S, Fang F, Weinstein SJ, Liao LM, Sinha R, Chen X, Albanes D, Huang J. Plant and Animal Fat Intake and Overall and Cardiovascular Disease Mortality. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2024 Aug 12.

- Song M, Fung TT, Hu FB, Willett WC, Longo VD, Chan AT, Giovannucci EL. Association of animal and plant protein intake with all-cause and cause-specific mortality. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2016 Oct 1;176(10):1453-63.

- Appel LJ, Sacks FM, Carey VJ, Obarzanek E, Swain JF, Miller ER, Conlin PR, Erlinger TP, Rosner BA, Laranjo NM, Charleston J. Effects of protein, monounsaturated fat, and carbohydrate intake on blood pressure and serum lipids: results of the OmniHeart randomized trial. JAMA. 2005 Nov 16;294(19):2455-64.

- Kelemen LE, Kushi LH, Jacobs Jr DR, Cerhan JR. Associations of dietary protein with disease and mortality in a prospective study of postmenopausal women. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2005 Feb 1;161(3):239-49.

- Shang X, Scott D, Hodge AM, English DR, Giles GG, Ebeling PR, Sanders KM. Dietary protein intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: results from the Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study and a meta-analysis of prospective studies. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2016 Nov 1;104(5):1352-65.

- Tong TY, Appleby PN, Bradbury KE, Perez-Cornago A, Travis RC, Clarke R, Key TJ. Risks of ischaemic heart disease and stroke in meat eaters, fish eaters, and vegetarians over 18 years of follow-up: results from the prospective EPIC-Oxford study. BMJ. 2019 Sep 4;366.

- Satija A, Bhupathiraju SN, Rimm EB, Spiegelman D, Chiuve SE, Borgi L, Willett WC, Manson JE, Sun Q, Hu FB. Plant-based dietary patterns and incidence of type 2 diabetes in US men and women: results from three prospective cohort studies. PLoS Medicine. 2016 Jun 14;13(6):e1002039.

- Eckart AC, Stavitz JA, Bhochhibhoya A, Sharma Ghimire P. Associations of animal source foods, cardiovascular disease history, and health behaviors from the national health and nutrition examination survey: 2013–2016. Global Epidemiology. 2023; 5. [CrossRef]

- Villegas R, Yang G, Gao YT, Cai H, Li H, Zheng W, Shu XO. Dietary patterns are associated with lower incidence of type 2 diabetes in middle-aged women: the Shanghai Women’s Health Study. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2010 Jun 1;39(3):889-99.

- Odegaard AO, Koh WP, Butler LM, Duval S, Gross MD, Yu MC, Yuan JM, Pereira MA. Dietary patterns and incident type 2 diabetes in Chinese men and women: the Singapore Chinese Health Study. Diabetes Care. 2011 Apr 1;34(4):880-5.

- Sinha R, Cross AJ, Graubard BI, Leitzmann MF, Schatzkin A. Meat intake and mortality: a prospective study of over half a million people. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2009 Mar 23;169(6):562-71.

- Fregoso-Aparicio L, Noguez J, Montesinos L, García-García JA. Machine learning and deep learning predictive models for type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome. 2021 Dec 20;13(1):148.

- Tan C, Li B, Xiao L, Zhang Y, Su Y, Ding N. A prediction model of the incidence of type 2 diabetes in individuals with abdominal obesity: insights from the general population. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Therapy. 2022 Jan 1:3555-64.

- Farvahari A, Gozashti MH, Dehesh T. The usage of lasso, ridge, and linear regression to explore the most influential metabolic variables that affect fasting blood sugar in type 2 Diabetes patients. Romanian Journal of Diabetes Nutrition and Metabolic Diseases. 2019;26(4):371-9.

- Qin Y, Wu J, Xiao W, Wang K, Huang A, Liu B, Yu J, Li C, Yu F, Ren Z. Machine learning models for data-driven prediction of diabetes by lifestyle type. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022 Nov 15;19(22):15027.

- Meng XH, Huang YX, Rao DP, Zhang Q, Liu Q. Comparison of three data mining models for predicting diabetes or prediabetes by risk factors. The Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences. 2013 Feb 1;29(2):93-9.

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES Survey Methods and Analytic Guidelines. [Internet]. Available from: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/analyticguidelines.

- National Cancer Institute, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences. Developing the Healthy Eating Index [Internet]. Available from: https://epi.grants.cancer.gov/hei/developing.

- Nanayakkara N, Curtis AJ, Heritier S, Gadowski AM, Pavkov ME, Kenealy T, Owens DR, Thomas RL, Song S, Wong J, Chan JC. Impact of age at type 2 diabetes mellitus diagnosis on mortality and vascular complications: systematic review and meta-analyses. Diabetologia. 2021 Feb;64:275-87.

- Janssen JA. Hyperinsulinemia and its pivotal role in aging, obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021 Jul 21;22(15):7797.

- Campagna D, Alamo A, Di Pino A, Russo C, Calogero AE, Purrello F, Polosa R. Smoking and diabetes: dangerous liaisons and confusing relationships. Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome. 2019 Dec;11:1-2.

- Levine ME, Suarez JA, Brandhorst S, Balasubramanian P, Cheng CW, Madia F, Fontana L, Mirisola MG, Guevara-Aguirre J, Wan J, Passarino G. Low protein intake is associated with a major reduction in IGF-1, cancer, and overall mortality in the 65 and younger but not older population. Cell Metabolism. 2014 Mar 4;19(3):407-17.

- arkova M, Pivovarova O, Hornemann S, Sucher S, Frahnow T, Wegner K, Machann J, Petzke KJ, Hierholzer J, Lichtinghagen R, Herder C. Isocaloric diets high in animal or plant protein reduce liver fat and inflammation in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Gastroenterology. 2017 Feb 1;152(3):571-85.

- Malik VS, Li Y, Tobias DK, Pan A, Hu FB. Dietary protein intake and risk of type 2 diabetes in US men and women. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2016 Apr 15;183(8):715-28.

- Van Nielen M, Feskens EJ, Mensink M, Sluijs I, Molina E, Amiano P, Ardanaz E, Balkau B, Beulens JW, Boeing H, Clavel-Chapelon F. Dietary protein intake and incidence of type 2 diabetes in Europe: the EPIC-InterAct Case-Cohort Study. Diabetes Care. 2014 Jul 1;37(7):1854-62.

- Sluijs I, Beulens JW, Van Der A DL, Spijkerman AM, Grobbee DE, Van Der Schouw YT. Dietary intake of total, animal, and vegetable protein and risk of type 2 diabetes in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-NL study. Diabetes Care. 2010 Jan 1;33(1):43-8.

- Azemati B, Rajaram S, Jaceldo-Siegl K, Sabate J, Shavlik D, Fraser GE, Haddad EH. Animal-protein intake is associated with insulin resistance in Adventist Health Study 2 (AHS-2) calibration substudy participants: a cross-sectional analysis. Current Developments in Nutrition. 2017 Apr 1;1(4):e000299.

- Brochu M, Mathieu ME, Karelis AD, Doucet É, Lavoie ME, Garrel D, Rabasa-Lhoret R. Contribution of the lean body mass to insulin resistance in postmenopausal women with visceral obesity: a Monet study. Obesity. 2008 May;16(5):1085-93.

- Ehrhardt N, Cui J, Dagdeviren S, Saengnipanthkul S, Goodridge HS, Kim JK, Lantier L, Guo X, Chen YD, Raffel LJ, Buchanan TA. Adiposity-independent effects of aging on insulin sensitivity and clearance in mice and humans. Obesity. 2019 Mar;27(3):434-43.

- Matta J, Mayo N, Dionne IJ, Gaudreau P, Fulop T, Tessier D, Gray-Donald K, Shatenstein B, Morais JA. Muscle mass index and animal source of dietary protein are positively associated with insulin resistance in participants of the NuAge study. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging. 2016 Feb;20:90-7.

- Aubertin-Leheudre M, Adlercreutz H. Relationship between animal protein intake and muscle mass index in healthy women. British Journal of Nutrition. 2009 Dec;102(12):1803-10.

- Liu Z, Guo Y, Zheng C. Type 2 diabetes mellitus related sarcopenia: a type of muscle loss distinct from sarcopenia and disuse muscle atrophy. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2024 May 24;15:1375610.

- Bowen KJ, Harris WS, Kris-Etherton PM. Omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease: are there benefits?. Current Treatment Options in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2016 Nov;18:1-6.

- Aung T, Halsey J, Kromhout D, Gerstein HC, Marchioli R, Tavazzi L, Geleijnse JM, Rauch B, Ness A, Galan P, Chew EY. Associations of omega-3 fatty acid supplement use with cardiovascular disease risks: meta-analysis of 10 trials involving 77 917 individuals. JAMA Cardiology. 2018 Mar 1;3(3):225-33.

- Watanabe Y, Tatsuno I. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids for cardiovascular diseases: present, past and future. Expert Review of Clinical Pharmacology. 2017 Aug 3;10(8):865-73.

- Chen YD, Raffel LJ, Buchanan TA. Adiposity-independent effects of aging on insulin sensitivity and clearance in mice and humans. Obesity. 2019 Mar;27(3):434-43.

- Brown TJ, Brainard J, Song F, Wang X, Abdelhamid A, Hooper L. Omega-3, omega-6, and total dietary polyunsaturated fat for prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2019 Aug 21;366.

- Johnston LW, Harris SB, Retnakaran R, Giacca A, Liu Z, Bazinet RP, Hanley AJ. Association of NEFA composition with insulin sensitivity and beta cell function in the Prospective Metabolism and Islet Cell Evaluation (PROMISE) cohort. Diabetologia. 2018 Apr;61:821-30.

- Jiang S, Yang W, Li Y, Feng J, Miao J, Shi H, Xue H. Monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids concerning prediabetes and type 2 diabetes mellitus risk among participants in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) from 2005 to March 2020. Frontiers in Nutrition. 2023 Nov 24;10:1284800.

- Serra MC, Ryan AS, Hafer-Macko CE, Yepes M, Nahab FB, Ziegler TR. Dietary and serum Omega-6/Omega-3 fatty acids are Associated with Physical and metabolic function in stroke survivors. Nutrients. 2020 Mar 6;12(3):701.

- Shetty SS, Shetty PK. ω-6/ω-3 fatty acid ratio as an essential predictive biomarker in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nutrition. 2020 Nov 1;79:110968.

- Sheppard KW, Cheatham CL. Omega-6/omega-3 fatty acid intake of children and older adults in the US: dietary intake in comparison to current dietary recommendations and the Healthy Eating Index. Lipids in Health and Disease. 2018 Dec;17:1-2.

- Egalini F, Guardamagna O, Gaggero G, Varaldo E, Giannone B, Beccuti G, Benso A, Broglio F. The effects of omega 3 and omega 6 fatty acids on glucose metabolism: An updated review. Nutrients. 2023 Jun 8;15(12):2672.

- Simopoulos AP. An increase in the omega-6/omega-3 fatty acid ratio increases the risk for obesity. Nutrients. 2016 Mar 2;8(3):128.

- Albert BB, Derraik JG, Brennan CM, Biggs JB, Smith GC, Garg ML, Cameron-Smith D, Hofman PL, Cutfield WS. Higher omega-3 index is associated with increased insulin sensitivity and more favourable metabolic profile in middle-aged overweight men. Scientific Reports. 2014 Oct 21;4(1):6697.

- Petersen KS, Maki KC, Calder PC, Belury MA, Messina M, Kirkpatrick CF, Harris WS. Perspective on the health effects of unsaturated fatty acids and commonly consumed plant oils high in unsaturated fat. British Journal of Nutrition. 2024 Sep 24:1-2.

- Oh YS, Bae GD, Baek DJ, Park EY, Jun HS. Fatty acid-induced lipotoxicity in pancreatic beta-cells during development of type 2 diabetes. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2018 Jul 16;9:384.

- Keane DC, Takahashi HK, Dhayal S, Morgan NG, Curi R, Newsholme P. Arachidonic acid actions on functional integrity and attenuation of the negative effects of palmitic acid in a clonal pancreatic β-cell line. Clinical Science. 2011 Mar 1;120(5):195-206.

- Qian F, Korat AA, Malik V, Hu FB. Metabolic effects of monounsaturated fatty acid–enriched diets compared with carbohydrate or polyunsaturated fatty acid–enriched diets in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care. 2016 Aug 1;39(8):1448-57.

- Bowden Davies KA, Sprung VS, Norman JA, Thompson A, Mitchell KL, Halford JC, Harrold JA, Wilding JP, Kemp GJ, Cuthbertson DJ. Short-term decreased physical activity with increased sedentary behaviour causes metabolic derangements and altered body composition: effects in individuals with and without a first-degree relative with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2018 Jun;61(6):1282-94.

- Carbone S, Del Buono MG, Ozemek C, Lavie CJ. Obesity, risk of diabetes and role of physical activity, exercise training and cardiorespiratory fitness. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases. 2019 Jul 1;62(4):327-33.

- Ye J, Yin J. Type 2 diabetes: a sacrifice program handling energy surplus. Life Metabolism. 2024 Dec;3(6):loae033.

- Zeng X, Ji QP, Jiang ZZ, Xu Y. The effect of different dietary restriction on weight management and metabolic parameters in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome. 2024 Oct 28;16(1):254.

- Schwingshackl L, Chaimani A, Hoffmann G, Schwedhelm C, Boeing H. A network meta-analysis on the comparative efficacy of different dietary approaches on glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2018 Feb;33:157-70.

| PBF Pattern (n = 2,119) | ASF Pattern (n = 2,119) | ||||

| Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median Diff. (ASF / PBF) |

|

| Age (yrs.) | 45 | 31 | 43 | 30 | 0.96 |

| Alpha-Linolenic acid (18:3n-3) (umol/L) | 64.1 | 38.6 | 69 | 42.9 | 1.08 |

| Arachidonic acid (20:4n-6) (umol/L) | 711 | 298 | 754 | 290 | 1.06 |

| ASF MUFAs (gm) | . | . | 8.04 | 9.46 | . |

| ASF PUFAs (gm) | . | . | 3.52 | 4.74 | . |

| BMI Change (past year) | -0.68 | 2.56 | -0.94 | -0.936 | 1.38 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 27.3 | 7.7 | 28 | 8.4 | 1.03 |

| Carbohydrate (gm) | 244.94 | 136.45 | 227.07 | 145.38 | 0.93 |

| Cholesterol (mg) | 205 | 189 | 444 | 371 | 2.17 |

| Dietary fiber (gm) | 16 | 11 | 14.3 | 11.2 | 0.89 |

| Direct HDL-Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 52 | 19 | 51 | 20 | 0.98 |

| Docosahexaenoic acid (22:6n-3) (umol/L) | 117 | 62.9 | 120 | 78 | 1.03 |

| Eicosapentaenoic acid (20:5n-3) (umol/L) | 35.8 | 32.8 | 41.5 | 33.4 | 1.16 |

| Glycohemoglobin (%) | 5.3 | 8.41 | 5.4 | 8.66 | 1.02 |

| UFAs: SFAs Ratio | 22.97 | 17.11 | 27.31 | 20.42 | 1.19 |

| HS C-Reactive Protein (mg/L) | 1.3 | 3.8 | 1.3 | 3.1 | 1 |

| Insulin (uU/mL) | 8.38 | 8.66 | 8.82 | 8.6 | 1.05 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 103 | 48 | 107 | 53 | 1.04 |

| Linoleic acid (18:2n-6) (umol/L) | 3,140.00 | 1,070.00 | 3,210.00 | 980 | 1.02 |

| Plant MUFAs (gm) | 1.65 | 3.58 | 2.16 | 5.194 | 1.31 |

| Plant PUFAs (gm) | 2.09 | 3.5 | 2.18 | 3.902 | 1.05 |

| Plant Total Energy (kcals) | 277 | 158 | 378 | 416 | 1.36 |

| Plant Total Fat (gm) | 6.05 | 11.9 | 7.06 | 14.9 | 1.17 |

| Protein (gm) | 76.52 | 45.54 | 87.69 | 52.32 | 1.15 |

| Ratio of ASF kcals to Total kcals | . | . | 0.2136 | 0.1866 | . |

| Ratio of Dietary O6 to O3 | 9.01 | 3.64 | 9.07 | 3.35 | 1.01 |

| Ratio of Plant kcals to Total kcals | 0.1735 | 0.2211 | 0.1781 | 0.1984 | 1.03 |

| Ratio of Serum O6 to O3 | 14.34 | 5.19 | 13.91 | 4.33 | 0.97 |

| Ratio of Total Physical Activity to Sedentary Time (mins) | 0.048 | 0.218 | 0.05 | 0.2 | 1.04 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 178 | 54 | 187 | 55 | 1.05 |

| Total Energy (kcal) | 2016 | 1087 | 2158 | 1078 | 1.07 |

| Total Fat (gm) | 72.54 | 52.31 | 86.76 | 58.61 | 1.2 |

| Total Monounsaturated Fatty Acids (gm) |

24.34 | 19.41 | 30.492 | 21.124 | 1.25 |

| Total MUFAs (gm) | 2.16 | 5.2 | 7.942 | 9.36 | 3.68 |

| Total Omega-3 (gm) | 1.562 | 1.42 | 1.749 | 1.528 | 1.12 |

| Total Omega-6 (gm) | 14.514 | 12.15 | 16.736 | 13.013 | 1.15 |

| Total Percent Body Fat | 32 | 12.6 | 30.9 | 13.5 | 0.97 |

| Total Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (gm) | 16.422 | 13.63 | 18.656 | 14.732 | 1.14 |

| Total PUFAs (gm) | 2.19 | 3.9 | 3.285 | 4.8 | 1.5 |

| Total Serum Omega 3 (mmol/L) | 304.78 | 164.95 | 308.45 | 151.03 | 1.01 |

| Total Serum Omega 6 (mmol/L) | 4391.6 | 1425.1 | 4302.2 | 1416.6 | 0.98 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 89 | 72 | 88 | 83 | 0.99 |

| No Diabetes (n = 3,976) | Diabetes (n = 262) | Median Diff. | |||

| Median | IQR | Median | IQR | (Diabetes / No Diabetes) | |

| Age (yrs.) | 28 | 41 | 59 | 17 | 2.107 |

| Alpha-Linolenic acid (18:3n-3) (umol/L) | 64.6 | 38.7 | 68.4 | 53.6 | 1.05 |

| Arachidonic acid (20:4n-6) (umol/L) | 722 | 295 | 743 | 364 | 1.03 |

| ASF MUFAs (gm) | 8.036 | 9.746 | 8.558 | 7.192 | 1.06 |

| ASF PUFAs (gm) | 3.489 | 5.103 | 3.955 | 3.399 | 1.13 |

| BMI Change (past year) | -0.84 | 2.75 | -0.07 | 3.93 | 0.083 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 24.5 | 9.7 | 31.3 | 20.3 | 1.278 |

| Carbohydrate (gm) | 239.26 | 142.12 | 201.97 | 117.57 | 0.844 |

| Cholesterol (mg) | 268 | 332 | 319 | 381 | 1.19 |

| Dietary Fiber (gm) | 12.9 | 11.9 | 12.3 | 22.7 | 0.953 |

| Direct HDL-Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 52 | 18 | 49 | 21 | 0.942 |

| Docosahexaenoic acid (22:6n-3) (umol/L) | 118 | 68.6 | 129 | 73.1 | 1.09 |

| Eicosapentaenoic acid (20:5n-3) (umol/L) | 36.5 | 33.1 | 44.3 | 37.2 | 1.21 |

| Energy (kcal) | 1,958.00 | 878 | 2,115.00 | 2,120.00 | 1.08 |

| Glycohemoglobin (%) | 5.3 | 0.5 | 6.6 | 1.9 | 1.245 |

| UFAs: SFAs Ratio | 24.78 | 18.93 | 27.56 | 20.43 | 1.112 |

| HS C-Reactive Protein (mg/L) | 1.1 | 2.9 | 3.3 | 5.8 | 3 |

| Insulin (uU/mL) | 8.3 | 7.8 | 12 | 12.26 | 1.446 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 102 | 49 | 92 | 44 | 0.902 |

| Linoleic acid (18:2n-6) (umol/L) | 3,150.00 | 1,030.00 | 3,210.00 | 1,260.00 | 1.01 |

| Plant MUFAs (gm) | 2.066 | 5.012 | 3.38 | 9.228 | 1.63 |

| Plant PUFAs (gm) | 2.057 | 3.895 | 3.307 | 6.046 | 1.6 |

| Ratio of ASF kcals to Total kcals | 0.2115 | 0.1868 | 0.2283 | 0.1979 | 1.07 |

| Ratio of Dietary O6 to O3 | 9.5 | 3.37 | 9.41 | 1.44 | 0.991 |

| Ratio of Plant kcals to Total kcals | 0.1716 | 0.1965 | 0.2289 | 0.2578 | 1.33 |

| Ratio of Serum O6 to O3 | 14.95 | 5.19 | 13.71 | 2.7 | 0.917 |

| Ratio of Total Physical Activity to Sedentary Time (mins) | 0.071 | 0.25 | 0 | 0.08 | 0 |

| Total ASF Fat (gm) | 24.72 | 22.58 | 19.69 | 5.52 | 0.797 |

| Total ASF Protein (gm) | 28.28 | 32.82 | 36.68 | 33.68 | 1.297 |

| Total fat (gm) | 78.85 | 53.6 | 74.42 | 56.2 | 0.944 |

| Total Monounsaturated Fatty acids (gm) | 26.68 | 18.48 | 32.98 | 34.44 | 1.236 |

| Total Omega-3 (gm) | 1.46 | 1.34 | 1.57 | 1.27 | 1.07 |

| Total Omega-6 (gm) | 13.89 | 11.84 | 14.5 | 12.74 | 1.04 |

| Total Plant Fat (gm) | 8.23 | 11.93 | 16.15 | 21.12 | 1.962 |

| Total Plant Protein (gm) | 8.14 | 8.6 | 8.22 | 20.48 | 1.01 |

| Total Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (gm) | 15.52 | 13.46 | 24.16 | 13.61 | 1.557 |

| Total Serum Omega-3 (mmol/L) | 291.55 | 124.23 | 359.42 | 155.73 | 1.233 |

| Total Serum Omega-6 (mmol/L) | 4,166.40 | 1,081.60 | 4,966.70 | 439.7 | 1.192 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 81 | 68 | 90 | 80 | 1.111 |

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | Factor 5 | Factor 6 | Factor 7 | Factor 8 | Factor 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variance Explained (%) | 23.26 | 10.71 | 8.66 | 7.9 | 6.85 | 6.05 | 5.87 | 4.23 | 4.18 |

| Higher Total Energy & UFAs | Unhealthy Lifestyle, Older, & Poor Body Composition | Female Gender | ASF Dietary Pattern | Higher ASF Fat & Protein | Lower Serum O6:O3 Ratio, Higher O3 | Higher Plant Fat & Protein | Higher Dietary O6:O3 Ratio | Recent BMI Increase & Smoking History | |

| PUFAs (gm) | 0.96 | -0.01 | 0.04 | 0.00 | -0.01 | -0.01 | -0.01 | 0.03 | -0.02 |

| Total Omega-6 (gm) | 0.96 | -0.01 | 0.04 | 0.00 | -0.01 | -0.01 | -0.01 | 0.07 | -0.02 |

| UFAs: SFAs | 0.92 | 0.03 | -0.03 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.01 |

| MUFAs (gm) | 0.91 | 0.02 | -0.03 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.01 |

| Total Energy (kcals) | 0.88 | 0.01 | -0.10 | -0.04 | 0.03 | -0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Total Omega-3 (gm) | 0.86 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | -0.35 | -0.01 |

| Dietary Fiber (gm) | 0.61 | 0.03 | -0.05 | -0.23 | -0.12 | 0.06 | 0.18 | -0.10 | 0.02 |

| Unhealthy Lifestyle | 0.02 | 0.85 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | -0.03 |

| Age (years) | 0.02 | 0.84 | -0.02 | -0.04 | -0.02 | 0.06 | 0.05 | -0.02 | 0.13 |

| Body Mass Index | 0.06 | 0.77 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | -0.02 | -0.32 |

| Smoking History | -0.01 | 0.69 | -0.15 | 0.08 | 0.05 | -0.04 | -0.03 | 0.04 | 0.30 |

| Female | 0.00 | -0.02 | 0.99 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Male | 0.00 | 0.02 | -0.99 | 0.00 | -0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | -0.01 | -0.04 |

| ASF Dietary Pattern | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.99 | -0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | -0.02 | 0.00 |

| PBF Dietary Pattern | -0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | -0.99 | 0.01 | -0.01 | -0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| Total ASF Fat (gm) | 0.03 | -0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.95 | -0.01 | -0.02 | 0.00 | -0.02 |

| Total ASF Protein (gm) | -0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | -0.01 | 0.94 | 0.02 | 0.03 | -0.01 | 0.01 |

| Total Serum Omega-3 (umol/L) | -0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.96 | 0.01 | 0.01 | -0.01 |

| Serum O6:O3 Ratio | -0.02 | -0.02 | -0.01 | 0.07 | 0.01 | -0.76 | 0.07 | 0.11 | -0.14 |

| Total Serum Omega-6 (umol/L) | 0.02 | 0.00 | -0.02 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.64 | 0.06 | 0.15 | -0.20 |

| Total Plant Fat (gm) | 0.03 | -0.03 | 0.02 | 0.04 | -0.09 | -0.01 | 0.91 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Total Plant Protein (gm) | -0.03 | 0.04 | -0.02 | -0.01 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.90 | -0.02 | 0.00 |

| Dietary O6:O3 Ratio | 0.05 | -0.01 | 0.02 | -0.04 | -0.01 | -0.01 | 0.00 | 0.97 | 0.01 |

| Change in BMI (past year) | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.10 | -0.01 | -0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.85 |

| Body Fat (%) | -0.11 | 0.25 | 0.43 | -0.03 | -0.05 | 0.00 | -0.01 | -0.01 | -0.42 |

| PAX | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | -0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | -0.01 | -0.01 | 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).