1. Introduction

Nanotechnology has influenced every facet of human life with applications in areas including material science and technology, medicine, agriculture, and food [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Nanotechnology provides great promise in improving agricultural productivity and reducing environmental impact. Agriculture is a highly chemical intensive area, as the chemical inputs are applied multiple times in the form of fertilizers, agrochemicals, pesticides, fungicides and herbicides, as well as various growth regulators. It is estimated that a significant portion (50-90%) of these chemical inputs are lost in the environment leading to pollution, affecting human and animal life negatively. Developing efficient means of delivering nutrients through nanotechnology will positively benefit productivity, economy, food security and health. Nanoparticle mediated delivery of therapeutic agents is an area of immense interest, because of its novelty and increased efficiency due to targeted delivery of therapeutic materials. The influence of nanomaterials on human health is also increasingly being scrutinized, as the use of engineered nanomaterials is increasing worldwide [

7]. Engineered nanomaterials can escape into the environment as airborne nanostructured agglomerates (eg. silver nanoparticles, TiO

2) or SWNT (eg. Single walled Carbon nanotubes) which enter the body through inhalation, ingestion, and penetration through skin, subsequently get mobilized into other organs. Engineered nanomaterials from biological components are also being explored for several type of applications, including drug delivery, cosmetics, food ingredients, coatings, food packaging materials etc. [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Nanomaterials can also enter the body through food chain, especially through the consumption of plant derived food that has accumulated such materials from soil, water and air [

13].

As an omnipresent biological macromolecule in plants, and especially abundant in fruits and vegetables, the physicochemical properties of pectin have been well studied. Potential utility of pectin in medicine for drug encapsulation, targeted delivery and development of hydrogels for applications as skin protectants, either alone, or in combination with proteins, or synthetic molecules such as polyvinyl pyrrolidone, and polylactic acid has been well-explored [

14]. Pectin-based materials have been consumed as food, and its ability as a food matrix for transporting encapsulated bioactives into the colon help protect the microbiome. Pectin-based nanostructures have been explored for drug delivery through multiple roots [

15,

16].

Three-dimensional structure of pectin matrices is influenced by the free carboxylic acid groups (homogalacturonans and rhamnogalacturonans). Pectin chains can exist as anionic chains stabilized by divalent ions such as calcium adopting various forms, based on pH of the embedded solution. Pectin formulations such as films, hydrogels, nanoparticles etc., have been explored for multiple medical applications. However, pectin-based matrices have some disadvantages such as low mechanical strength, low shear stability, low drug loading efficacy, and premature drug release. For this reason, chemical and physical alterations of pectin by blending or co-polymerization with biodegradable polymers such as chitosan, polylactic acid, starch, gelatin, soy protein, β-lactoglobulin, human serum albumin etc., to provide a higher charge density (positive primary amine and negative carboxyl group), have been explored. Production of ZnO-pectin nanoparticles ranging in size between 70–200 nm in diameter has been achieved to explore the possibility of enhancing Zn uptake in Zn-deficient population [

17]. Such molecules have been observed to penetrate into the tissue deeper and able to provide better drug delivery. Thiolated nanoparticles of pectin have been prepared for better ocular drug delivery. SPIONs (superparamagnetic iron-based nanoparticles) and oxaliplatin were encapsulated in Pectin-Ca

2+ to form pectin based spherical nanoparticles, 100–200 nm in diameter with magnetic function. The cancer drug paclitaxel was conjugated with pectin nanoparticles, and the process has been suggested to be influenced by the hydrophilicity of pectin (-OH and -COOH groups) as well as positively charged amide groups of asparagines [

18,

19]. Attempts have also been made to deliver several classes of drugs such as thiazoles with low solubility, cancer drugs, neuro-and mood controlling drugs, and insulin through pectin based nanoparticles [

20]. Similar studies are advancing in plants, where, the charge, as well as shape of nanoparticles, determines their foliar bioavailability [

21].

Formation of amorphous carbon nanoparticles have been observed to exist in caramelized food [

22]. The occurrence of nanovesicular type components in grape juice [

23] suggests that similar structures could be formed during processing where cell disruption occurs providing an environment for molecular interactions and self-assembly, resulting in the formation of well-defined biological nanostructures. The present study describes the physico-chemical characterization, properties, and potential functional uses of nanoparticles from sour cherry and its applications. As well, designer functional foods fortified with such nanocomponents can enhance bioavailability of nutrients that may help prevent chronic diseases.

3. Materials and Methods

Materials. Sour cherry (Prunus cerasus) fruit were obtained from the Vineland Research Station, Vineland, Ontario. Fruit were stored frozen at –40°C until use. Chemicals were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, USA, ThermoFisher Canada, Invitrogen, Molecular Probes etc.

Isolation and Purification of nanoparticles. Pitted fruit were homogenized using a polytron homogenizer with a PTA 10 probe in a medium (preferably water, may use absolute or diluted ethanol or methanol), in 1:1 proportion (w/w, 1 g tissue to 1 mL water or alcohol), at an intermediate setting (4–5) until the tissue is completely homogenized. The homogenate was filtered through 4 layers of cheese cloth. The filtrate was centrifuged (18,000x g) in a Sorvall RC6 Plus centrifuge for 20 min. The supernatant (5 mL) was dialyzed (Spectra-Por, 6–8 kDa cut off) against water (1 L) for 12 h at 4⁰C. The dialyzed extract was lyophilized to obtain nanoparticles as a powder. In some cases, the homogenate was passed through a PD-10 exclusion column packed with Sephadex G-25 (exclusion limit 5 kDa, 7.5 mL bed volume, Amersham Biosciences), and the void volume fractions were collected. The fractions containing nanoparticles were pooled and subjected to transmission electron microscopy. For the preparation of nanofibers, the pitted cherry fruit was immersed in equal volume of 50 % ethanol (3×) to remove anthocyanins. The bleached cherry was homogenized and subjected to filtration and centrifugation as described earlier. The homogenate was dialyzed against water, and the dialyzed extract was lyophilized to a fluffy powder of nanofibers which was observed under SEM and TEM.

Polyphenol estimation and analysis. Polyphenols were estimated by Folin-Ciocalteau method [

23] Samples were diluted to a final volume of 100

μL with 50 % (v/v) of ethanol in water. The polyphenol concentrations are expressed as gallic acid equivalent per gram fresh weight of fruit. Polyphenols were purified and concentrated using Sep-Pak C18 chromatography. Usually, 1–2 mg polyphenol equivalent of extract was loaded onto a 1 mL cartridge, washed with 1–2 mL water, and polyphenols were eluted with 100 % methanol. Methanol was removed in a stream of nitrogen at 45⁰C and the resulting dry polyphenols were dissolved in methanol (for HPLC-MS analysis).

Electron Microscopy. Transmission electron microscopy of nanoparticles and nanofibers was conducted according to standard methods [

23]. Carbon coated nickel grid was floated on a 50

μL drop of the respective sample solution for 30s. After blot-drying, the grid was stained with 1 % Uranyl acetate for 30s. The grid was blotted dry and examined under a Leo 912 B transmission electron microscope. For scanning electron microscopy, about 500

µg of lyophilized nanoparticles or nanofibers was dusted uniformly onto adhesive carbon conducting tape mounted on a 12 mm diameter aluminum stub and examined under a Scanning Electron Microscope (FEI Quanta 250, FEG).

Polygalacturonase, cellulase and trypsin treatment. One mL of dialyzed extract containing nanoparticles (0.8–1 mg polyphenol equivalent/mL) was treated with pectinase (1 unit /mL of extract), cellulase (β-1,4-glucanase, 1 unit/mL) or 1 unit of trypsin for 15 min. The nanoparticles were examined by TEM as described earlier.

Detergent treatment. Nanoparticles were incubated in the presence of increasing concentrations of lipid-destabilizing detergents such as Triton-X 100 and sodium deoxycholate in 6–8 kDa cut off dialysis bags and dialyzed against water adjusted to a pH of 4.0, for 12 h. The absorbance of polyphenols inside the dialysis bag was measured at 520 nm (benzopyran) and 260 nm (phenolic ring).

Analysis of protein. Protein was extracted using TRIzol

® (Invitrogen, ThermoFisher Scientific) following standard methods (

Supporting information for the detailed protocol). Protein was isolated from nanoparticles or nanofibers by homogenizing in 300 mM potassium citrate (pH 6.0). Protein samples (15

µg) were separated on 10 % polyacrylamide gels under denaturing and reducing conditions. The gel was fixed in 10 % acetic acid and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R250.

Association of pectin in nanoparticles. Apple pectin and polygalacturonic acid were dissolved in 0.1 N NaOH and used as standards. The nanoparticles and pectin samples were resolved on 10 % polyacrylamide gels under denaturing/reducing condition. After electrophoresis, the gel was stained with propidium iodide (10 µM in water) for 1 h and photographed. The same gel was again stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R250.

Western and spot blot analysis. To identify the nature of major carbohydrate structural components of the nanoparticles and nanofibers, western and spot blot analysis of the polypeptides isolated from nanoparticles and nanofibers were performed using four monoclonal antibodies (

www.Plantprobes.net) raised against homogalacturonan (LM20), extensin (LM1), arabinogalactan-protein (LM14), and LM15, specific to an epitope of xyloglucan having a sequence x-x-x-G

Supporting information for the detailed protocols).

Sequence analysis of major peptide bands in nanofibers and nanoparticles. Two distinct bands that were characteristically observed during SDS-PAGE of nanofiber proteins (labelled 1 and 2 with relative molecular masses of 40 kDa and 20 kDa, respectively,

Figure S3, Supporting information) were sliced out. A region from the SDS-PAGE gel of nanoparticle proteins corresponding to band 1 of nanofibers (

Figure S3, Supporting information, Panels A and B) was also sliced out. The sequences of these peptides were analyzed by Edman sequencing and HPLC/MS/MS at the SPARC BioCentre, Hospital for SickKids, Toronto.

GCMS analysis of organic acids and sugars. Organic acids present in nanoparticles and nanofibers were identified by non-hydrolyzing trimethylsilylation. Nanoparticles and nanofiber solution was purified through size exclusion column (PD 10) and lyophilized into powder. Lyophilized powder (400 µg) was dissolved in 100 µL of pyridine, and 100 µL of BSTFA: TMCS mixture (99:1) and incubated at 80°C for 1 h. One µL was directly injected for GC-MS analysis using a Saturn GC-MS system. Trimethylsilyl derivatives of sugars in the nanoparticles and nanofibers, and sugar standards, were prepared using procedures described by the manufacturer (Pierce Chemicals CO). Nanoparticles and nanofibers were subjected to digestion using trifluoroacetic acid, before derivatization with BSTFA. Derivatized sugars were extracted with hexane and analyzed using a Saturn GC-MS system.

FT-IR analysis. FT-IR analysis of nanoparticles and nanofibers were conducted using a Bruker Tensor 27 InfraRed spectrometer. Equal amounts of nanoparticle and nanofiber powders (1 %) were mixed with potassium bromide and made into a transparent disc which was scanned for acquiring the spectra.

HPLC-MS analysis. Anthocyanins in the crude extracts, dialyzed extracts and the dialyzate fractions was performed using an Agilent 1100 series HPLC-MS. Separation was conducted using an X-Terra® MS C-18 column (5 μm, 150 x 3.0 mm, Waters Corporation, MA, USA). Anthocyanins were eluted with a gradient of methanol (solvent A) and 2.0 % (v/ v) formic acid (solvent B) at a flow rate of 0.8 ml/min. The gradient used was as follows: 0 – 2 min, 93 % B; 2 – 30 min, 80 % B; 30 – 45 min, 70 % B; 45 – 50 min; 65 % B, 50 – 60 min, 50 % B; 60 – 65 min, 20 % B; 65 – 70 min, 93 % B. Detection was carried out at 520 nm for anthocyanins and at 260 nm for phenolic acids. Electrospray ionization (ESI) was performed with an API-ES mass spectrometer. Nitrogen was used as the nebulizing and drying gas, at a flow rate of 12 L/min at 350

o C; an ion spray voltage of 4000 V and a fragmentor voltage of 80 V. Ions generated were scanned from m/z 100 to 700. Spectra were acquired in the positive and negative ion mode. A sample injection volume of 20

μL (20

µg) was used for all the samples. Structure identification of the compounds was achieved by matching their molecular ions (m/z) obtained by LC-ESI-MS with literature (

www.metabolomics.jp). Three independent samples were analyzed and the quantity of ingredients expressed as mean ± SEM per g fresh weight of tissue equivalent.

Cell culture. Three cell lines (ATCC): CRL 1790 (normal colon), HT 29 (colorectal cancer), and CRL 2158 (a multidrug resistant colorectal cancer) were used to evaluate the cytotoxicity of nanoparticles and nanofibers. Cells were grown in their specific media (HT 29 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium, CRL 2158 in RPMI, and CRL 1790 in Eagle’s minimum essential medium, Cedarlane Labs, Burlington, ON, Canada) supplemented with fetal bovine serum, Penicillin / streptomycin, and L-glutamine. At confluency (~80 %), cells were washed with 1× PBS twice and stained using a live-dead staining kit.

Confocal Microscopy. Cells (2 × 105) were grown (35 mm×10mm dish) until confluency and examined under a confocal microscope after staining with appropriate reagents. Dylight 650 (Excitation 650 nm, Emission 700 nm, Thermo Scientific Pierce Biology Products) was found to provide superior performance and stability during uptake experiments. Lyophilized powder of the dialyzed extract containing nanocomplexes (4 mg) was mixed with a 10 μM solution of Dylight 650 ester dissolved in dimethylformamide and incubated for 1 h at 25⁰C for conjugation. After the reaction, the mixture was dialyzed against water (3×) using a 6-8 kDa dialysis membrane until the free reagents were completely removed. The binding of Dylight to the nanoparticles and nanofibers was evaluated by monitoring the fluorescence using confocal microscopy.

Statistical analysis. Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism version 4. Results having two means were compared using a Student’s t test. Results with multiple means were compared using one way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test to evaluate the level of significance. Significantly different means (p<0.05) are denoted by different superscripts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.P. and J.S..; methodology, K.R.T, R.C., N.N, P.P.; validation, K.R.T and G.P.; formal analysis, K.R.T., R.C., N.N., K.S.S.; investigation, K.R.T, R.C., K.S.S.; resources, G.P., J.S.,K.S.S.,; data curation, K.R.T., and R.C.,; writing—original draft preparation, G.P., K.R.T..; writing—review and editing, G.P., K.R.T and J.S.; visualization, K.S.S., N.N., K.R.T.,; supervision, G.P.,; project administration, G.P.,; funding acquisition, G.P., and J.S.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

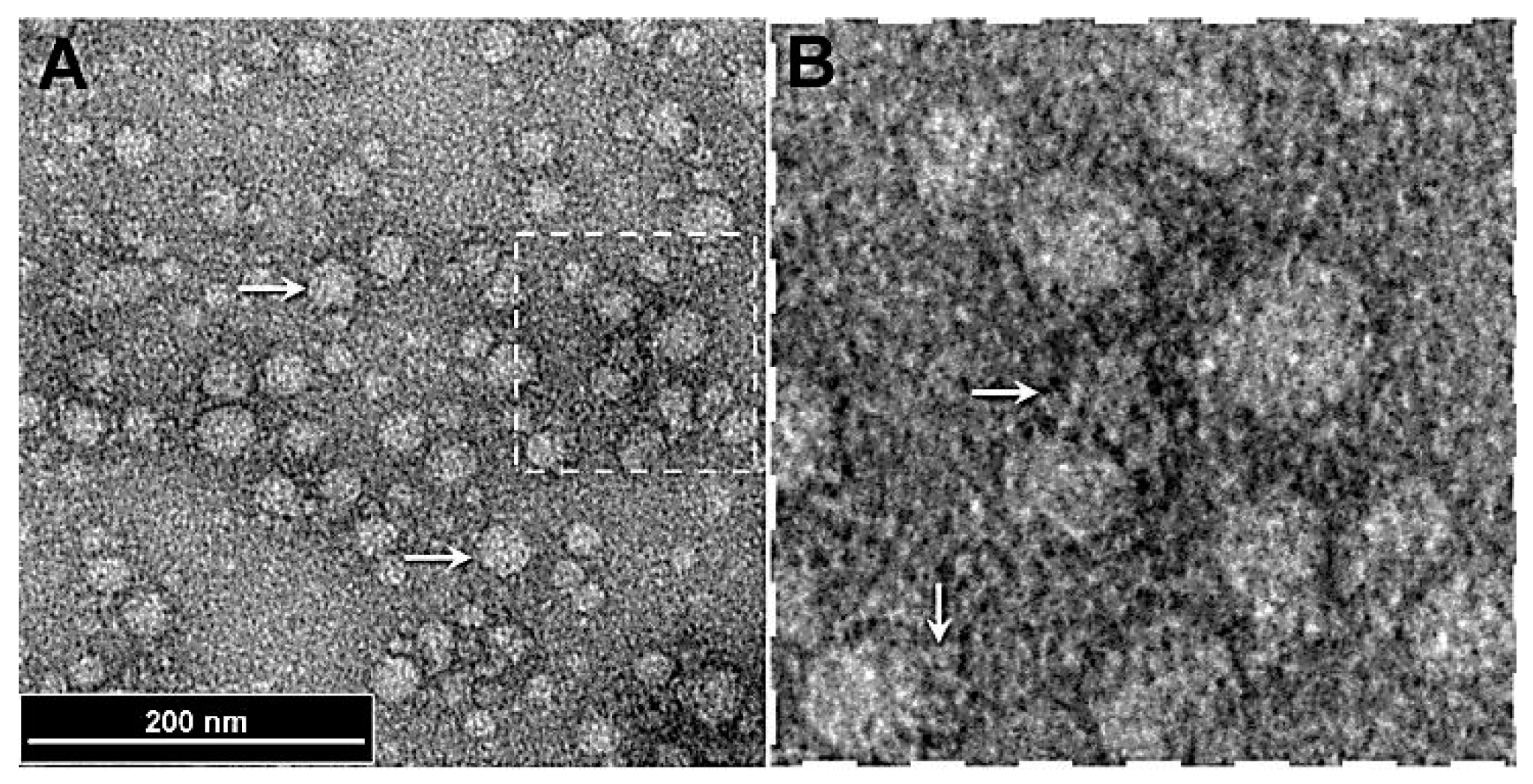

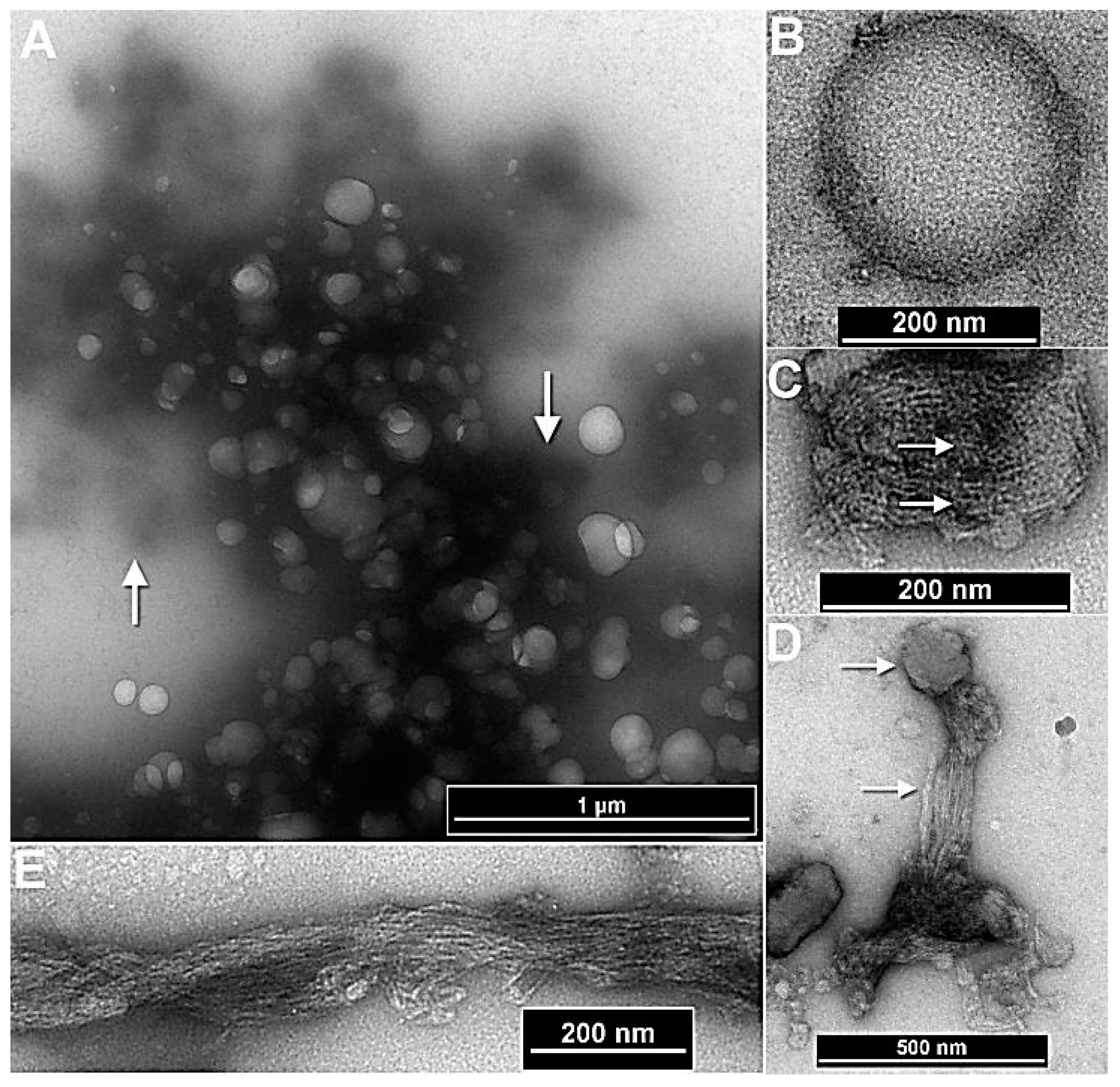

Figure 1.

(A) Transmission electron micrograph of nanoparticles. (B) A magnified view of the nanoparticles. The arrows indicate fibril like structures emanating from the nanoparticles.

Figure 1.

(A) Transmission electron micrograph of nanoparticles. (B) A magnified view of the nanoparticles. The arrows indicate fibril like structures emanating from the nanoparticles.

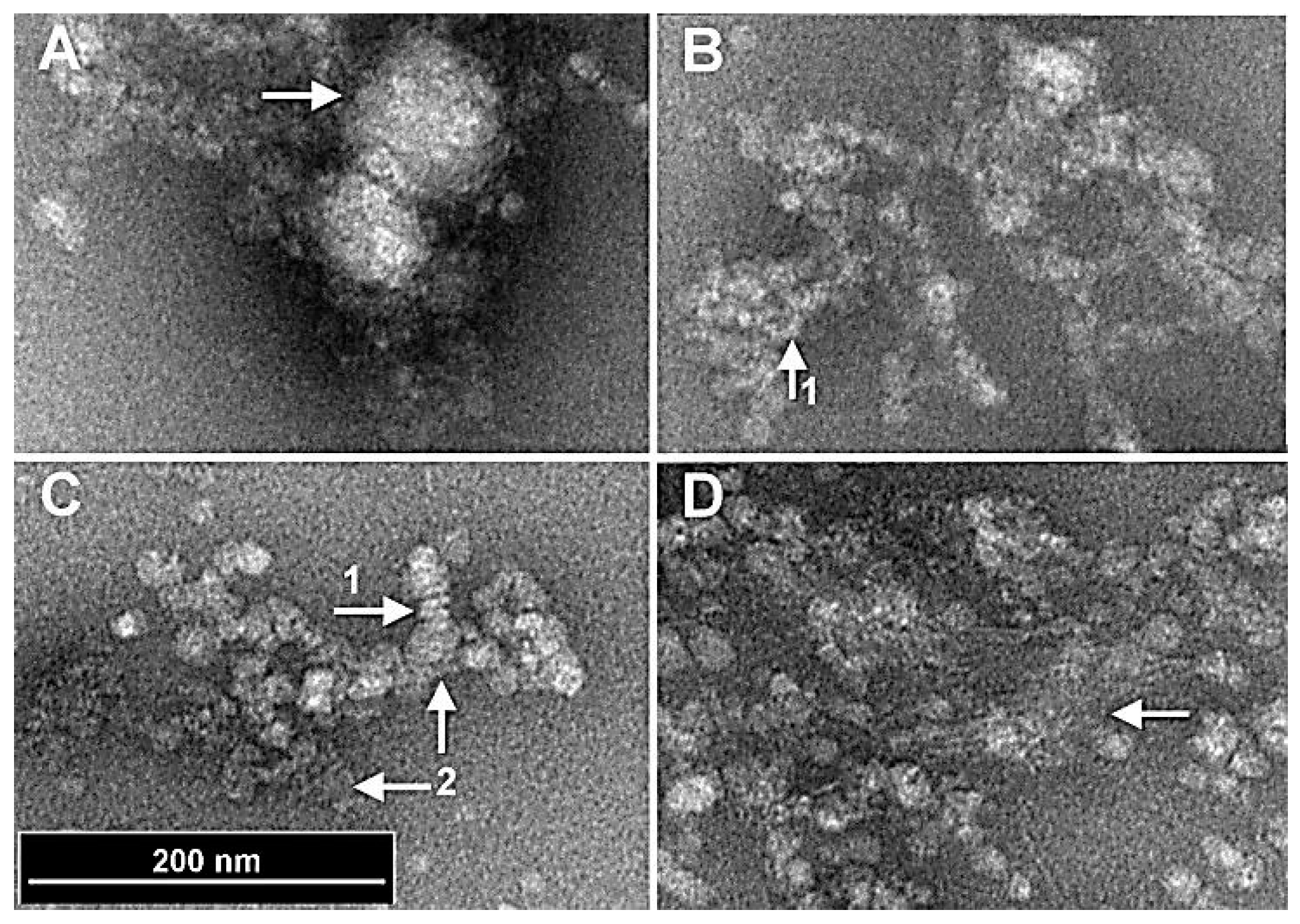

Figure 2.

Magnified views of nanoparticles as observed under the TEM. (A) Two nanoparticles that have been stripped of the outer structures exposing a much smoother interior shell (arrow). (B, C) Detailed morphology of the outer coating comprising fibrils. (Arrow 1) shows regions of the fibrils having a spiral fibrous structure. (Arrow 2) The spiral fibrous structures are coated with fibrils. (D) A region with simple fibril structure stripped from the spiral fibers. (Arrow) A mat of fibrils, that occurs during potential natural disassociation of the nanoparticles.

Figure 2.

Magnified views of nanoparticles as observed under the TEM. (A) Two nanoparticles that have been stripped of the outer structures exposing a much smoother interior shell (arrow). (B, C) Detailed morphology of the outer coating comprising fibrils. (Arrow 1) shows regions of the fibrils having a spiral fibrous structure. (Arrow 2) The spiral fibrous structures are coated with fibrils. (D) A region with simple fibril structure stripped from the spiral fibers. (Arrow) A mat of fibrils, that occurs during potential natural disassociation of the nanoparticles.

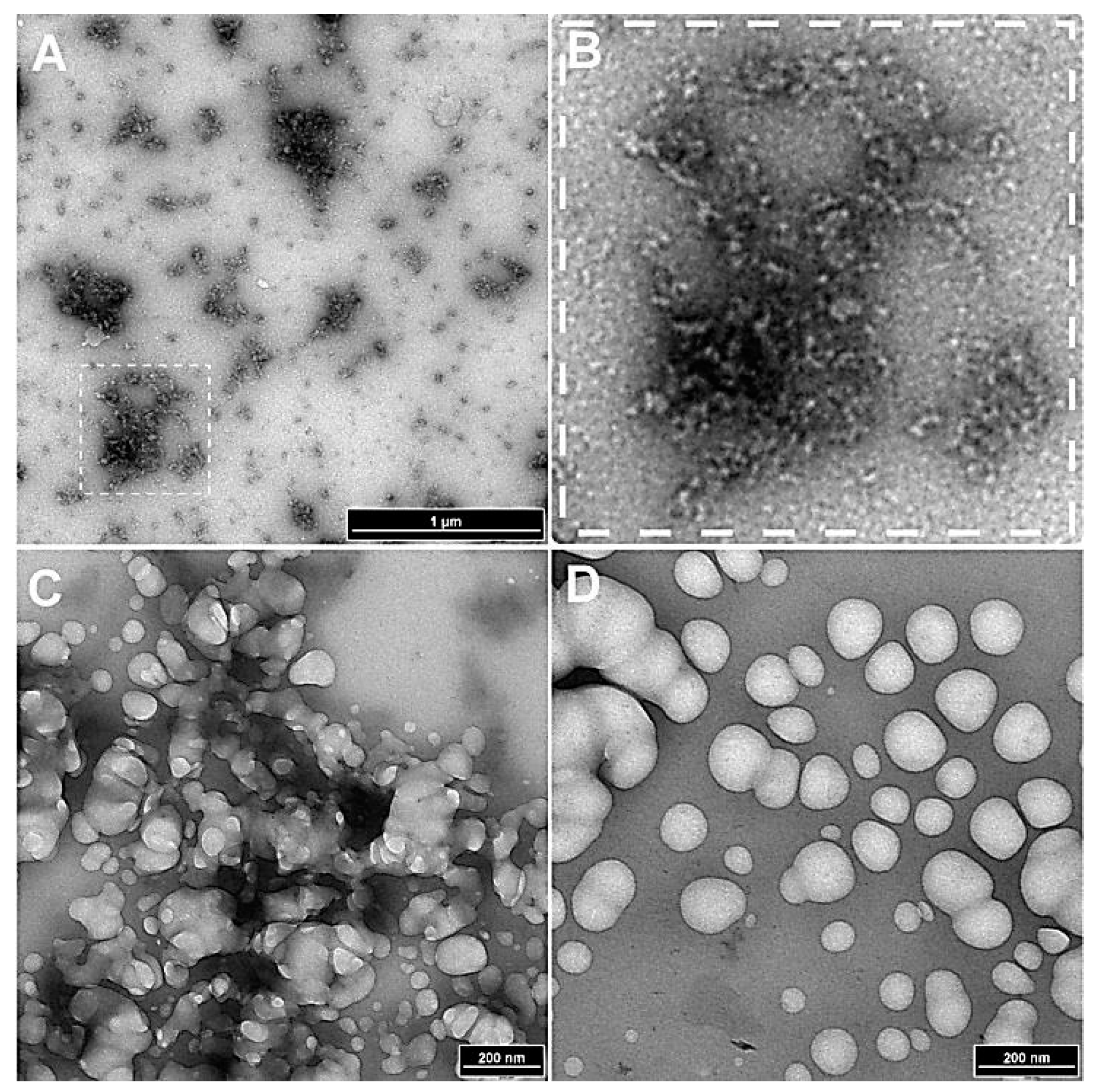

Figure 3.

Effect of polygalacturonase and cellulase treatments on the stability of nanoparticles. (A) Dissolution of spherical complexes into smaller vesicular and filamentous structures following α 1-4-glycosidase treatment (boxed region). (B) A magnified version of the boxed region. (C & D) The effect of treatment of the nanoparticles with β-1,4-glucanase, that stripped the complexes of the filamentous coat leaving an inner core indicating the presence of β-1,4-glucan type components in the filaments.

Figure 3.

Effect of polygalacturonase and cellulase treatments on the stability of nanoparticles. (A) Dissolution of spherical complexes into smaller vesicular and filamentous structures following α 1-4-glycosidase treatment (boxed region). (B) A magnified version of the boxed region. (C & D) The effect of treatment of the nanoparticles with β-1,4-glucanase, that stripped the complexes of the filamentous coat leaving an inner core indicating the presence of β-1,4-glucan type components in the filaments.

Figure 4.

Effect of trypsin treatment on the structure of nanoparticles. (A) Trypsin treatment resulted in the dissolution of the outer filamentous structure (stained with Ruthenium Red which binds pectin) seen as dark stained areas (Arrows) around the globular interior pectin shell of the nanoparticles. The shell like structures tend to fuse together as also observed after cellulase treatment (

Figure 3 C & D). (B) A magnified view of a shell like structure. (C) Partially digested nanoparticle showing the fibrous coating dispersing into fibrillar structures (arrows). (D) A nanoparticle that has been stripped off the fibrous structures. The top arrow shows the globular shell left after dissolution of the fibers, and the bottom arrow shows the fibrous structure liberated from the core. (E) A magnified view of the fibrils showing an intertwined assembly of the fibres.

Figure 4.

Effect of trypsin treatment on the structure of nanoparticles. (A) Trypsin treatment resulted in the dissolution of the outer filamentous structure (stained with Ruthenium Red which binds pectin) seen as dark stained areas (Arrows) around the globular interior pectin shell of the nanoparticles. The shell like structures tend to fuse together as also observed after cellulase treatment (

Figure 3 C & D). (B) A magnified view of a shell like structure. (C) Partially digested nanoparticle showing the fibrous coating dispersing into fibrillar structures (arrows). (D) A nanoparticle that has been stripped off the fibrous structures. The top arrow shows the globular shell left after dissolution of the fibers, and the bottom arrow shows the fibrous structure liberated from the core. (E) A magnified view of the fibrils showing an intertwined assembly of the fibres.

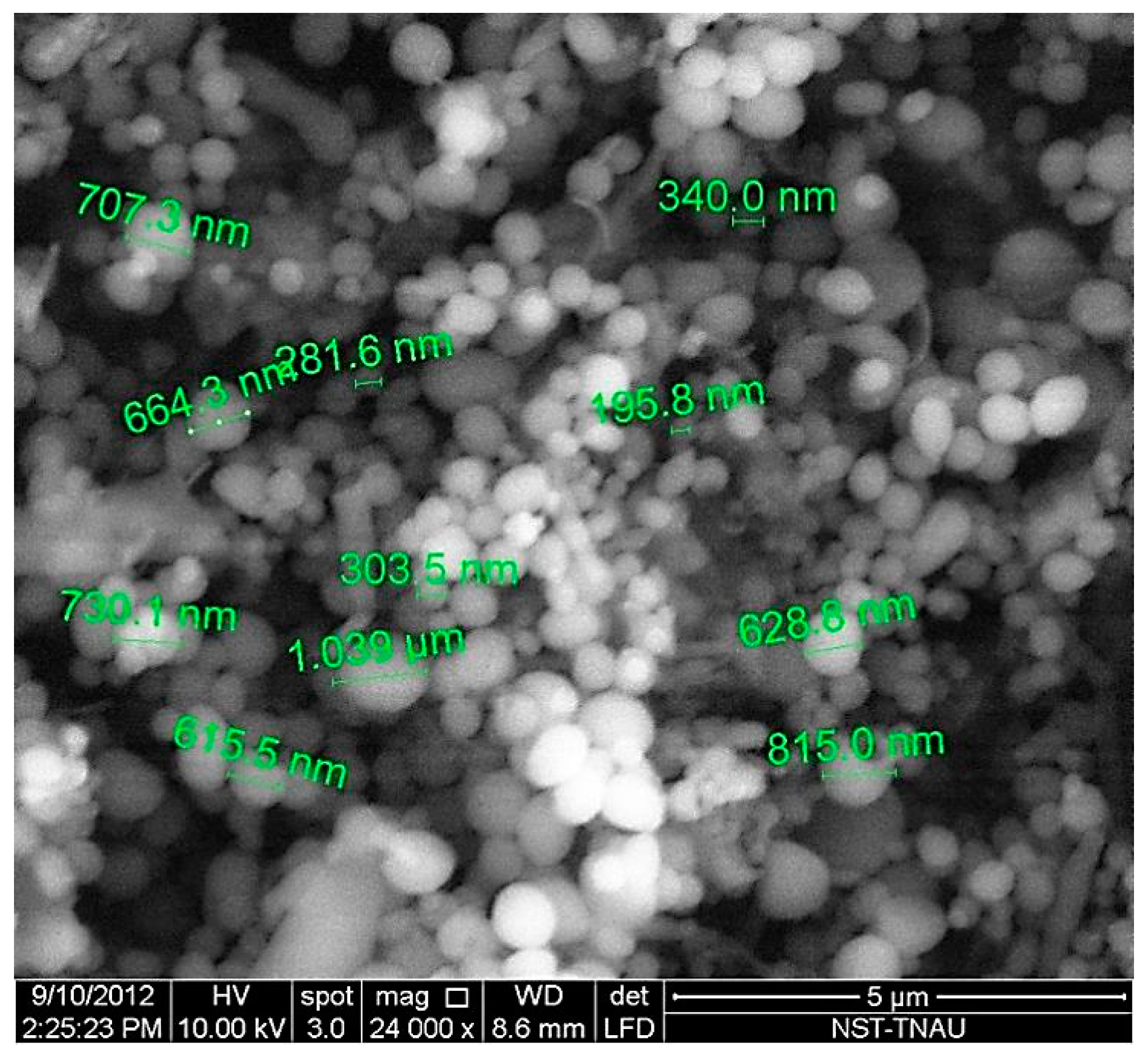

Figure 5.

Scanning electron micrograph of lyophilized nanoparticles showing a size distribution ranging from 200–800 nm in diameter.

Figure 5.

Scanning electron micrograph of lyophilized nanoparticles showing a size distribution ranging from 200–800 nm in diameter.

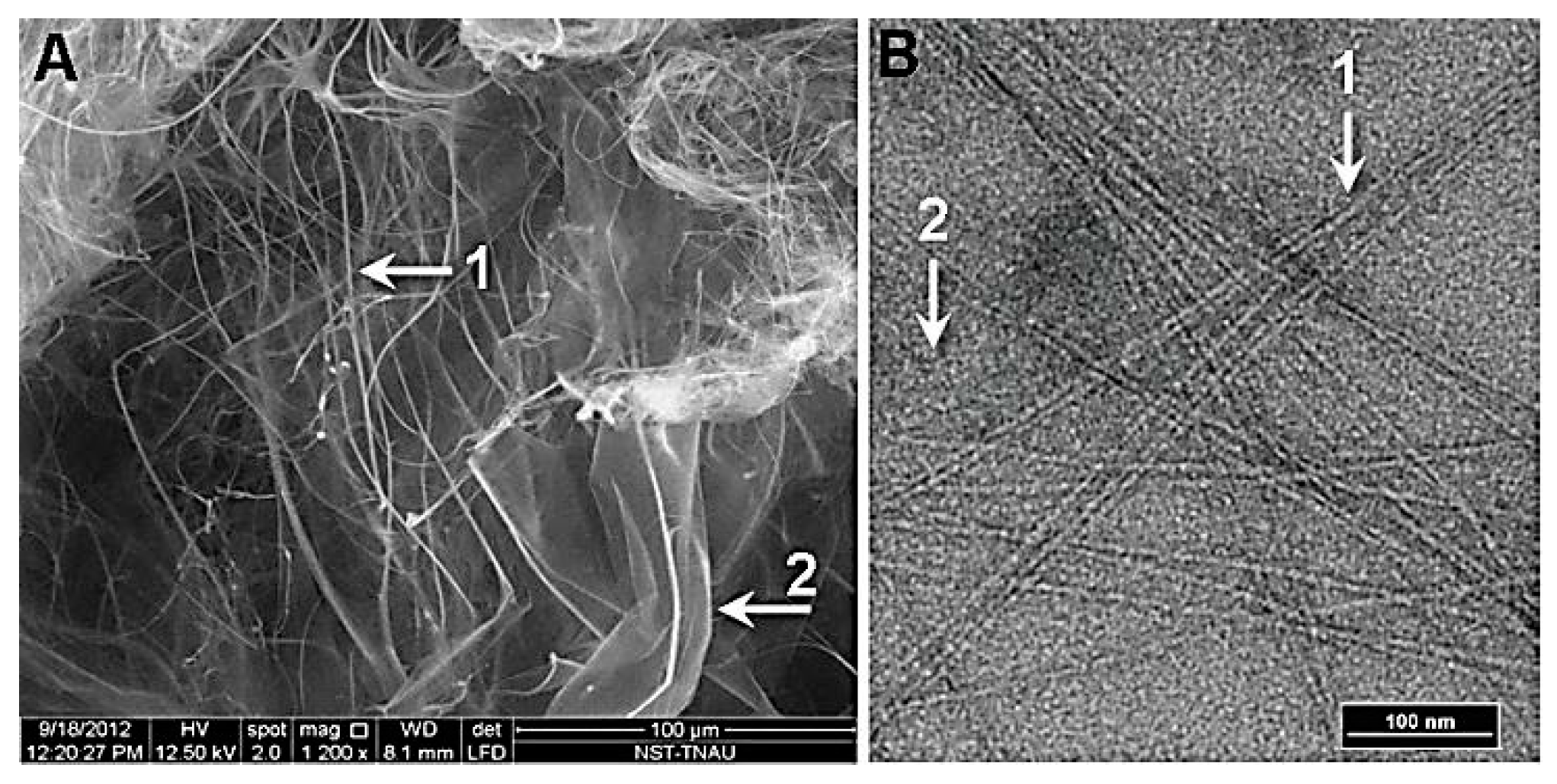

Figure 6.

Lyophilized nanofibers isolated from ethanol bleached sour cherry. (A) SEM of nanofibers (Arrows 1, 2). (B) TEM of nanofibers which appear micrometers in length 4–5 nm in diameter (Arrow 1). These filaments still retain the ability to form spiral structures (arrow 2) in solution.

Figure 6.

Lyophilized nanofibers isolated from ethanol bleached sour cherry. (A) SEM of nanofibers (Arrows 1, 2). (B) TEM of nanofibers which appear micrometers in length 4–5 nm in diameter (Arrow 1). These filaments still retain the ability to form spiral structures (arrow 2) in solution.

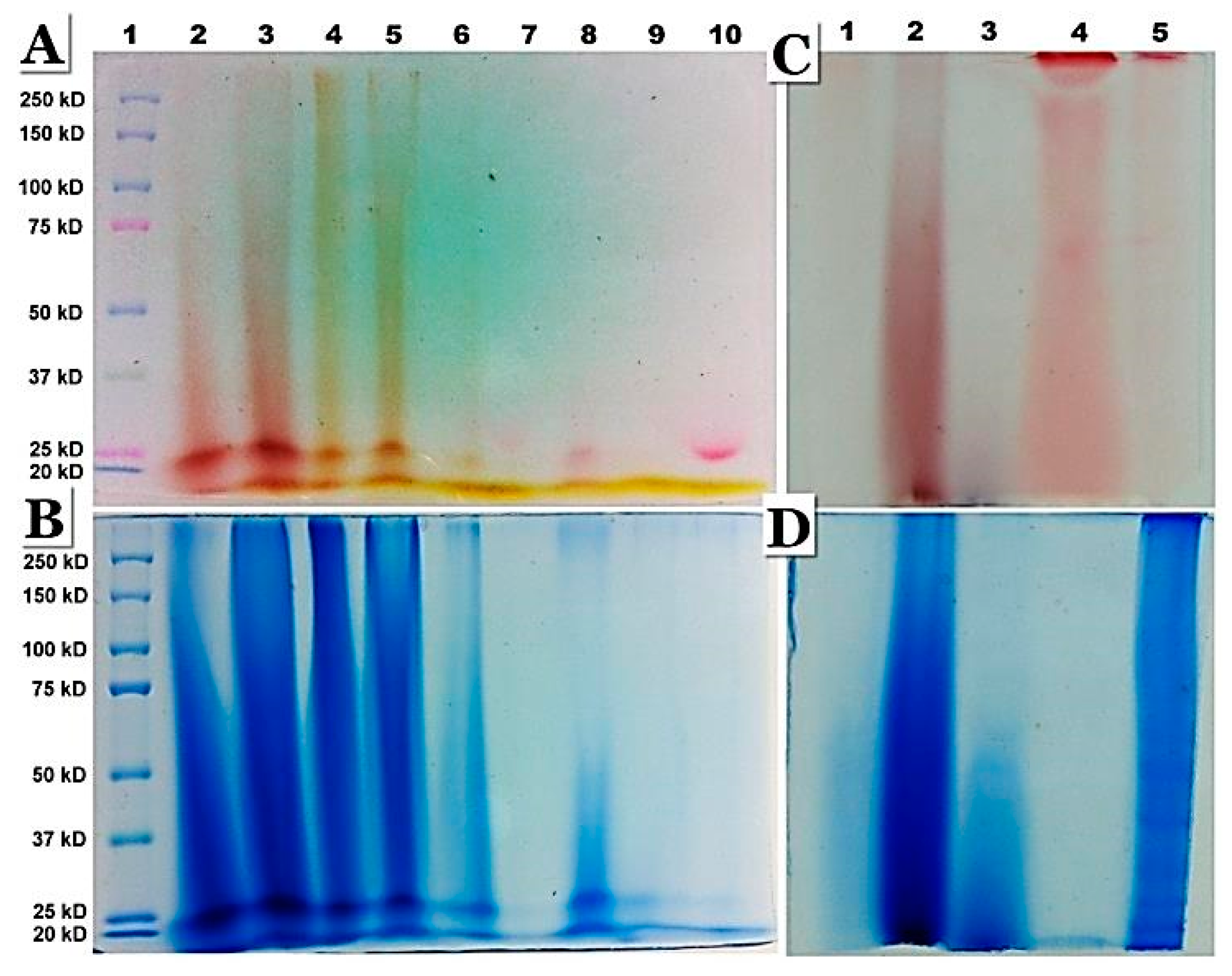

Figure 7.

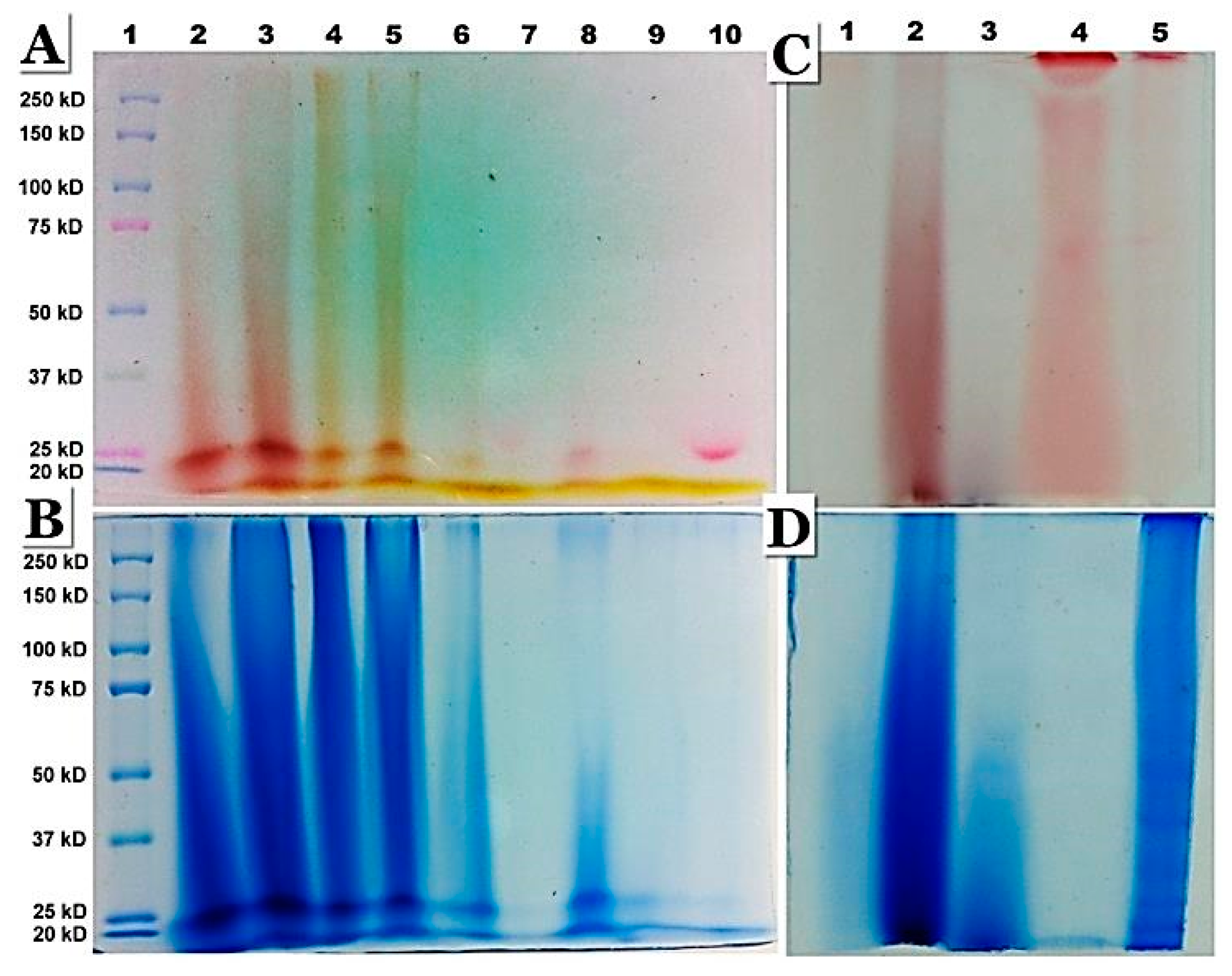

SDS-PAGE analysis of peptides in nanoparticles and nanofibers. (A) The gel before staining (incubated in 10 % acetic acid v/v) to reveal the pink colour of anthocyanins. (B) The same gel stained with Coomassie brilliant blue to reveal peptides. Lane 1 – Molecular markers, Lane 2 - Anthocyanins with polypeptides in nanoparticles resuspended in 15 % glycerol; Lane 3 – Supernatant (aqueous phase) after Trizol extraction of nanoparticles shows peptides associated with anthocyanins; Lane 4 – Nanoparticles in 15 % glycerol; Lanes 5, 6 and 7– Correspond to the supernatant, interphase and organic phase (no anthocyanin or peptide staining in Lane 7) of nanoparticles subjected to Trizol extraction; Note that the bulk of peptides and anthocyanins are in the aqueous (hydrophilic) phase of Trizol extract (Lane 5); Lanes 8, 9 and 10 – Correspond to the supernatant, interphase and the organic phase obtained after Trizol extraction of nanofibers from ethanol bleached cherries, where most of the anthocyanins have been removed, as observed in 7 A. Lanes 8, 9 and 10 of 7 B shows staining of nanofibers with Coomassie blue. Lane 8 (aqueous phase) showed the presence of peptides, while the interphase and the organic phase of nanofibers showed minimal staining for peptides (Lanes 9 & 10 of 7 B). (C & D) Association of pectin and polypeptides in the nanoparticles as revealed by the similarity in staining with propidium iodide and Coomassie brilliant blue after SDS-PAGE of nanoparticles. Lane 1 - Pectin; Lane 2 – Peptides in nanoparticles; Lane 3 – Peptides excluded during dialysis (6-8 kDa). Lane 4 – Polygalacturonic acid which shows staining with propidium iodide, and not for polypeptides (D). Lane 5 – Pellet of sour cherry homogenate (post 12000 ×g) also shows the presence of pectin and polypeptides.

Figure 7.

SDS-PAGE analysis of peptides in nanoparticles and nanofibers. (A) The gel before staining (incubated in 10 % acetic acid v/v) to reveal the pink colour of anthocyanins. (B) The same gel stained with Coomassie brilliant blue to reveal peptides. Lane 1 – Molecular markers, Lane 2 - Anthocyanins with polypeptides in nanoparticles resuspended in 15 % glycerol; Lane 3 – Supernatant (aqueous phase) after Trizol extraction of nanoparticles shows peptides associated with anthocyanins; Lane 4 – Nanoparticles in 15 % glycerol; Lanes 5, 6 and 7– Correspond to the supernatant, interphase and organic phase (no anthocyanin or peptide staining in Lane 7) of nanoparticles subjected to Trizol extraction; Note that the bulk of peptides and anthocyanins are in the aqueous (hydrophilic) phase of Trizol extract (Lane 5); Lanes 8, 9 and 10 – Correspond to the supernatant, interphase and the organic phase obtained after Trizol extraction of nanofibers from ethanol bleached cherries, where most of the anthocyanins have been removed, as observed in 7 A. Lanes 8, 9 and 10 of 7 B shows staining of nanofibers with Coomassie blue. Lane 8 (aqueous phase) showed the presence of peptides, while the interphase and the organic phase of nanofibers showed minimal staining for peptides (Lanes 9 & 10 of 7 B). (C & D) Association of pectin and polypeptides in the nanoparticles as revealed by the similarity in staining with propidium iodide and Coomassie brilliant blue after SDS-PAGE of nanoparticles. Lane 1 - Pectin; Lane 2 – Peptides in nanoparticles; Lane 3 – Peptides excluded during dialysis (6-8 kDa). Lane 4 – Polygalacturonic acid which shows staining with propidium iodide, and not for polypeptides (D). Lane 5 – Pellet of sour cherry homogenate (post 12000 ×g) also shows the presence of pectin and polypeptides.

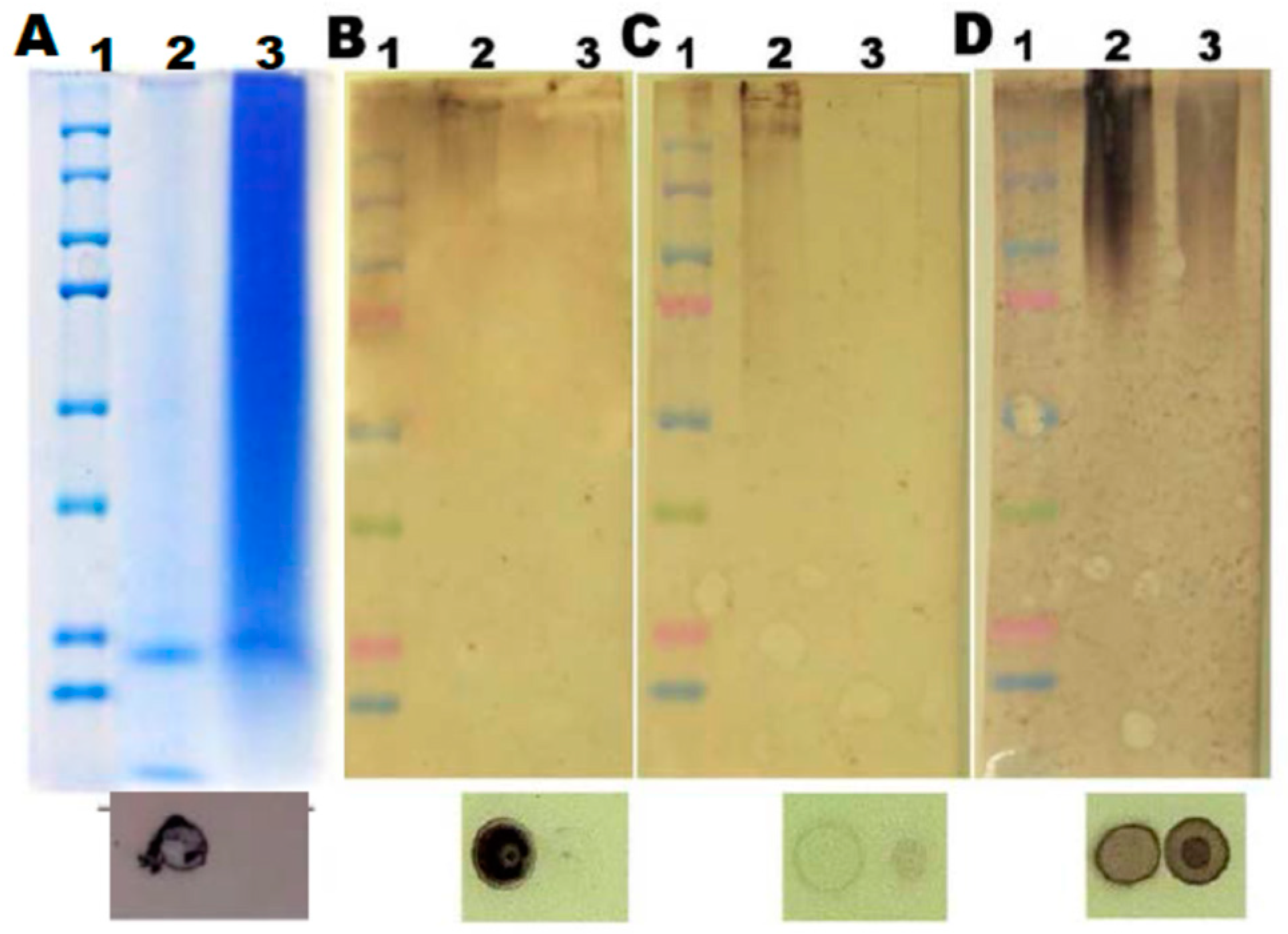

Figure 8.

Nanoparticles and nanofibers were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunolocalization with structure specific monoclonal antibodies (rat IgM). The bound antibodies were detected with alkaline phosphatase conjugated goat-anti rat IgG. (A) Coomassie brilliant blue staining of polypeptides in nanofibers (Lane 2) and nanoparticles (Lane 3). (B) shows the reactivity of nanoparticles (Lane 2) and nanofibers (Lane 3) against homogalacturonan (oligo 1,4-linked galacturonic acid methyl esters) antibody. Dot blots against the same antibody are shown below (B). (C) Reaction to anti-extensin antibodies. (D) Very strong reaction was observed against anti-arabinogalactan-protein (hemicellulose-protein) by both nanoparticles and nanofibers (Lanes 2 & 3). This was also demonstrated by dot blots (bottom). Dot blot below A indicates reactivity of nanofibers and nanoparticles to anti-xyloglucan (LM15).

Figure 8.

Nanoparticles and nanofibers were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunolocalization with structure specific monoclonal antibodies (rat IgM). The bound antibodies were detected with alkaline phosphatase conjugated goat-anti rat IgG. (A) Coomassie brilliant blue staining of polypeptides in nanofibers (Lane 2) and nanoparticles (Lane 3). (B) shows the reactivity of nanoparticles (Lane 2) and nanofibers (Lane 3) against homogalacturonan (oligo 1,4-linked galacturonic acid methyl esters) antibody. Dot blots against the same antibody are shown below (B). (C) Reaction to anti-extensin antibodies. (D) Very strong reaction was observed against anti-arabinogalactan-protein (hemicellulose-protein) by both nanoparticles and nanofibers (Lanes 2 & 3). This was also demonstrated by dot blots (bottom). Dot blot below A indicates reactivity of nanofibers and nanoparticles to anti-xyloglucan (LM15).

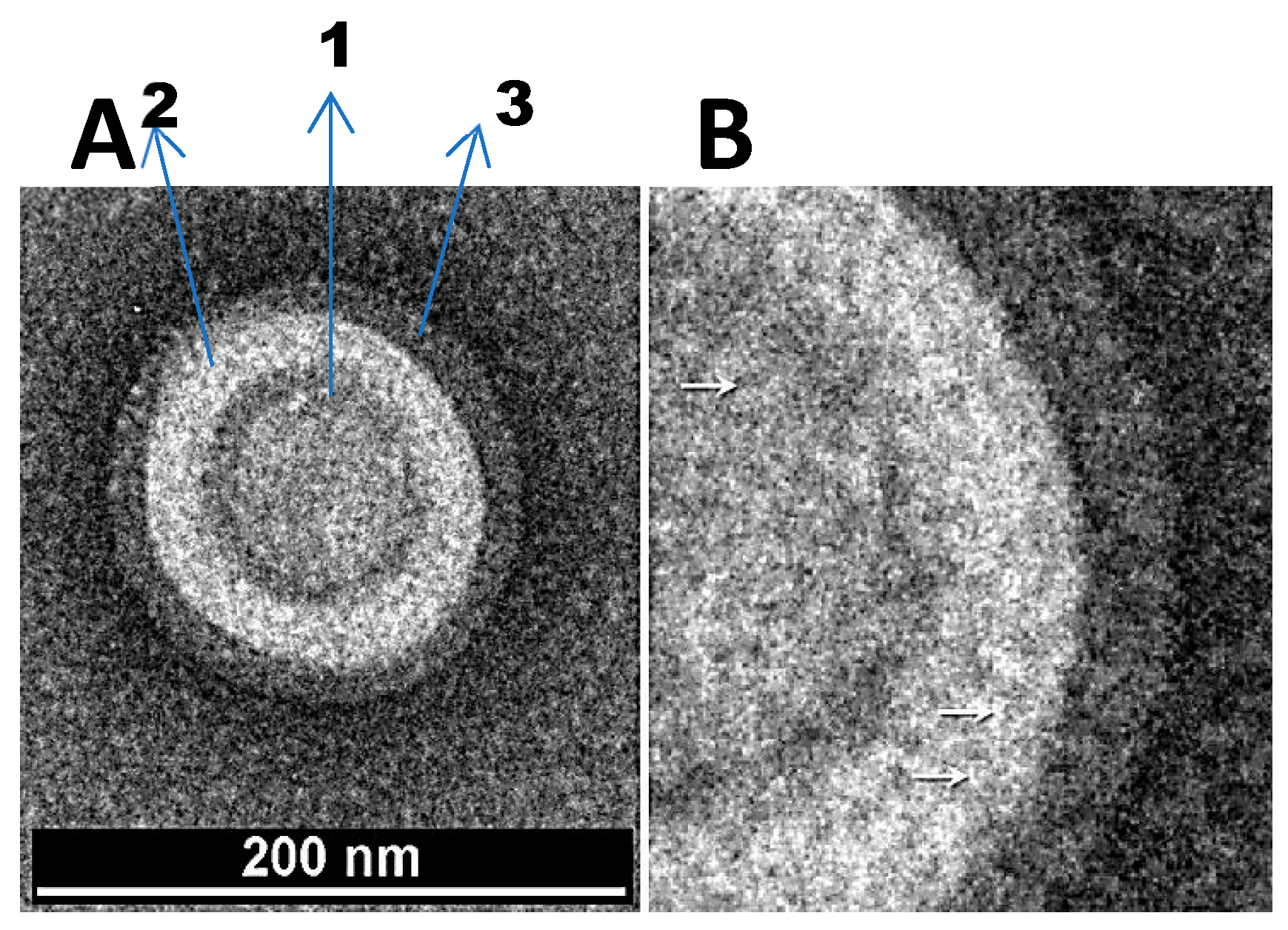

Figure 9.

A proposed model for the nanoparticle from a magnified view of a nanoparticle as observed by TEM. (A) arrow 1 – shows a collapsed region around the inner core showing a ring shaped structure, surrounded by a less electron dense region comprised of helical fibrous structures potentially containing pectin, peptides and anthocyanins (arrow 2). Surrounding this layer, there is a slightly more electron dense fibrillary region forming the outer part of the nanoparticle (arrow 3) potentially comprising arabinogalacan-protein containing fibrils. (B) – An enlarged view of the nanoparticle. The helical elements are indicated by arrows.

Figure 9.

A proposed model for the nanoparticle from a magnified view of a nanoparticle as observed by TEM. (A) arrow 1 – shows a collapsed region around the inner core showing a ring shaped structure, surrounded by a less electron dense region comprised of helical fibrous structures potentially containing pectin, peptides and anthocyanins (arrow 2). Surrounding this layer, there is a slightly more electron dense fibrillary region forming the outer part of the nanoparticle (arrow 3) potentially comprising arabinogalacan-protein containing fibrils. (B) – An enlarged view of the nanoparticle. The helical elements are indicated by arrows.

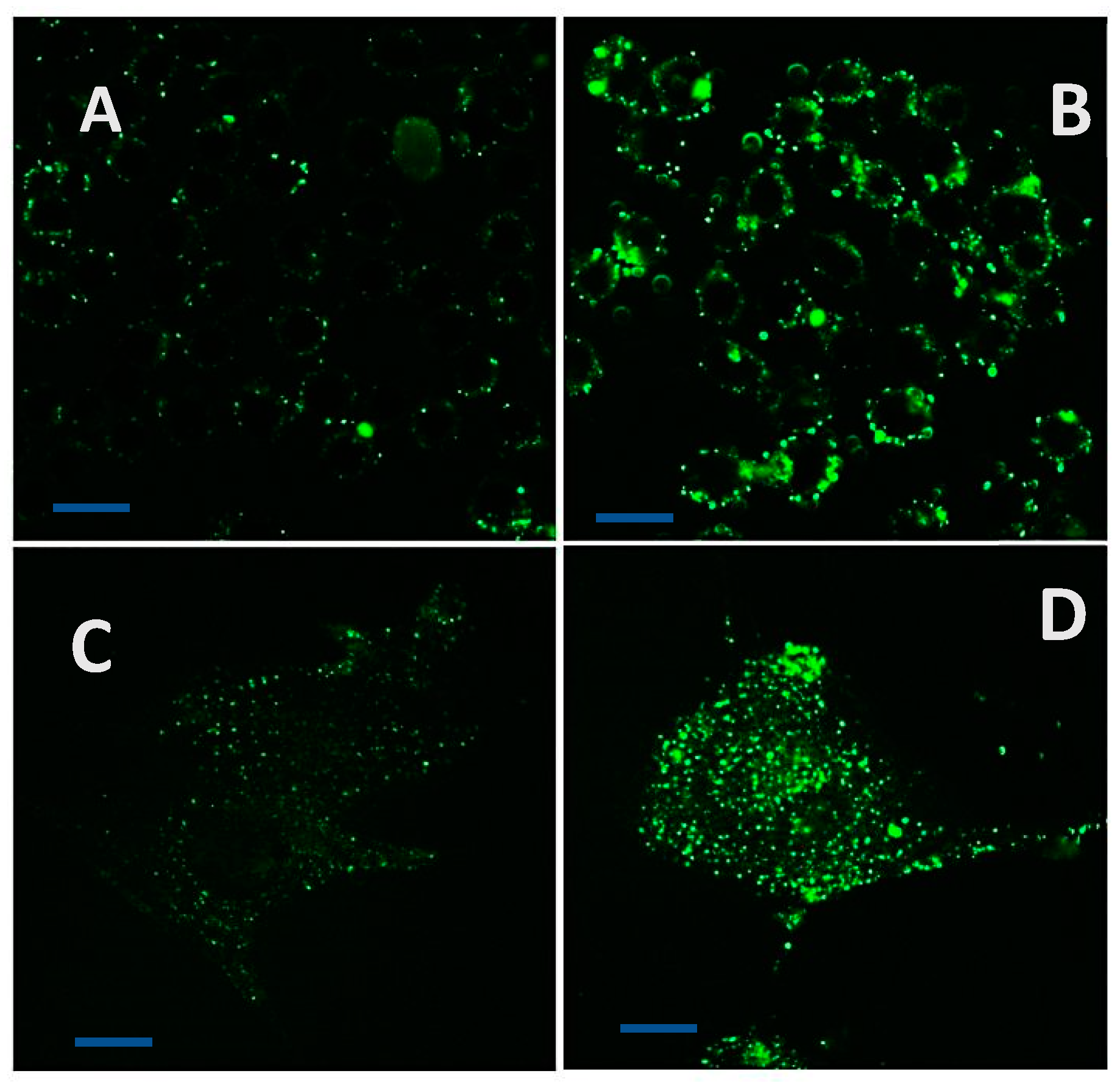

Figure 10.

Uptake of calcein-nanofiber adducts into HT 29 and CRL 1790 cells. (A, C) – Uptake of free calcein (Ex 494 nm/ Em 517 nm) by HT29 (top) and CRL 1790 (bottom) respectively; (B, D) – Uptake of nanofiber-calcein adducts into HT 29 (top) and CRL 1790 (bottom), respectively. The increased uptake is visible by the accumulation of nanofiber-calcein adducts in organelles showing enhanced fluorescence (bar= 25 µm).

Figure 10.

Uptake of calcein-nanofiber adducts into HT 29 and CRL 1790 cells. (A, C) – Uptake of free calcein (Ex 494 nm/ Em 517 nm) by HT29 (top) and CRL 1790 (bottom) respectively; (B, D) – Uptake of nanofiber-calcein adducts into HT 29 (top) and CRL 1790 (bottom), respectively. The increased uptake is visible by the accumulation of nanofiber-calcein adducts in organelles showing enhanced fluorescence (bar= 25 µm).

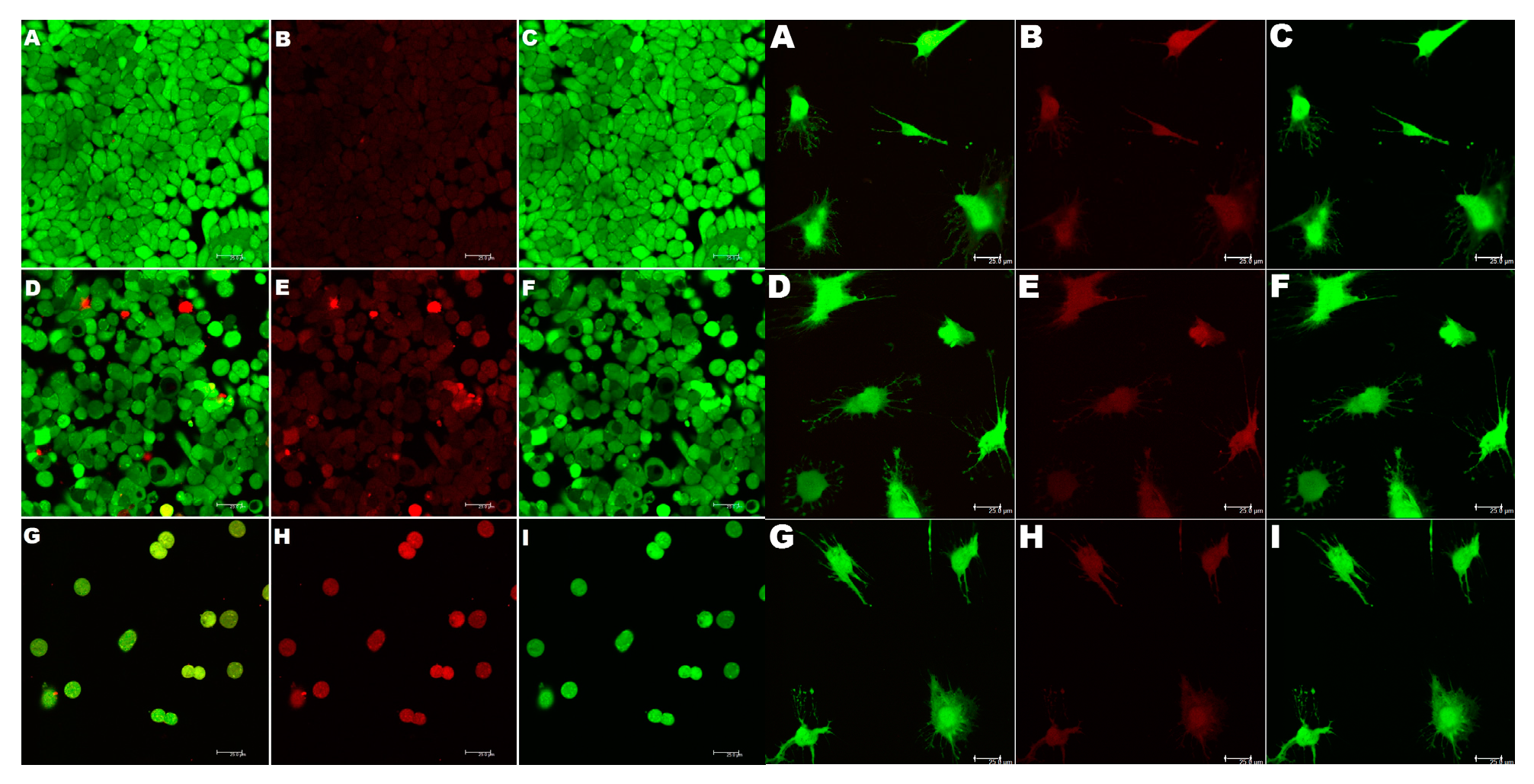

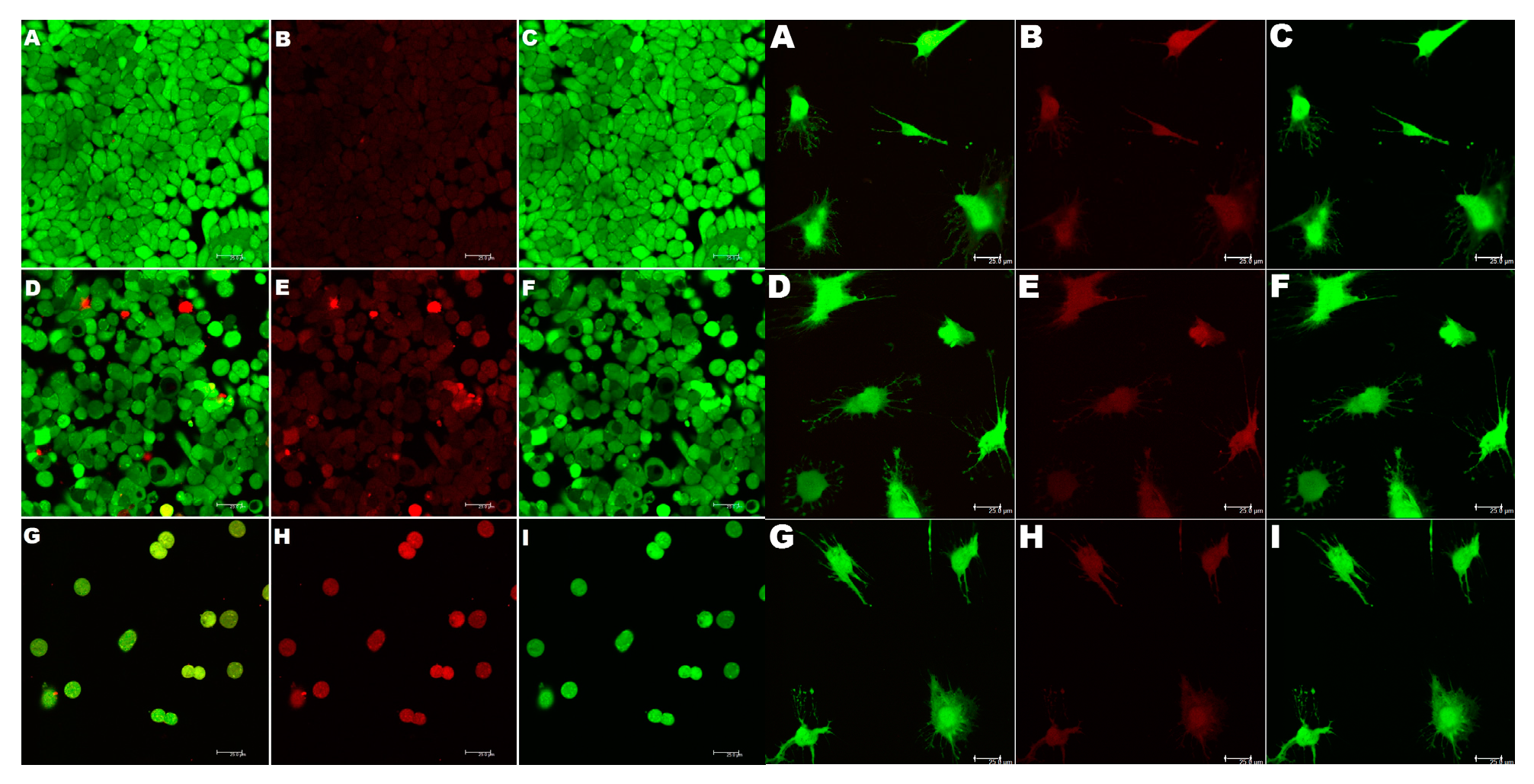

Figure 11.

(Left). Induction of cytotoxicity in CRL 2158 multidrug resistant cancer cells by paclitaxel in combination with nanofibers. The assay kit contains, calcein AM ester (Ex 494 nm, Em 517 nm) which specifically enters live cells, and stains the live cells green and ethidium homodimer (Ex 517 nm/ Em 617). The dying cells as well as dead cells are membrane compromised, and allows the entry of ethidium homodimer, which stains the nucleus red. The cells were observed at 517 nm to visualize live cells (green channel) and at 617 nm which enabled visualization of dead cells. The composite image from the two channels shows the cells in transition to loss of cell viability. (B, C) Control cells visualized at 617 nm (red, dead cells) and at 517 nm (green, live cells), respectively. (A) Composite image of untreated cells. (E, F) Cells treated with paclitaxel (32 nM) recorded at the two wavelengths 617 and 517 nm respectively. (D) Composite image. (H, I) Cells treated with 32 nM Paclitaxel + 4 μg/mL nanofiber. (G) A composite of the red and green images. Size bar = 25 µm.

Figure 11.

(Left). Induction of cytotoxicity in CRL 2158 multidrug resistant cancer cells by paclitaxel in combination with nanofibers. The assay kit contains, calcein AM ester (Ex 494 nm, Em 517 nm) which specifically enters live cells, and stains the live cells green and ethidium homodimer (Ex 517 nm/ Em 617). The dying cells as well as dead cells are membrane compromised, and allows the entry of ethidium homodimer, which stains the nucleus red. The cells were observed at 517 nm to visualize live cells (green channel) and at 617 nm which enabled visualization of dead cells. The composite image from the two channels shows the cells in transition to loss of cell viability. (B, C) Control cells visualized at 617 nm (red, dead cells) and at 517 nm (green, live cells), respectively. (A) Composite image of untreated cells. (E, F) Cells treated with paclitaxel (32 nM) recorded at the two wavelengths 617 and 517 nm respectively. (D) Composite image. (H, I) Cells treated with 32 nM Paclitaxel + 4 μg/mL nanofiber. (G) A composite of the red and green images. Size bar = 25 µm.