1. Introduction

Anthocyanins are a class of flavonoids that are responsible for the red, purple, and blue colors of many fruits and vegetables [

1]. These naturally occurring pigments have drawn considerable attention in recent years due to their powerful antioxidant properties and potential health benefits. Specifically, anthocyanins have been associated to the prevention of various chronic diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and neurodegenerative disorders [

2,

3,

4]. Despite their beneficial properties, anthocyanins are highly susceptible to degradation when exposed to environmental factors such as light, temperature, and pH, which can significantly affect their stability and bioavailability [

5,

6].

To address these challenges, microencapsulation has emerged as a promising technique for protecting anthocyanins from environmental degradation and to control their release in the body [

7]. Microencapsulation involves the entrapment of the anthocyanins within a protective matrix, which can enhance their stability and bioavailability. In this study, we focus on the microencapsulation of anthocyanins extracted from

Vaccinium floribundum (Andean blueberry) and

Rubus glaucus (Andean blackberry), two fruits native to Ecuador that are known for their high anthocyanin content and potential health benefits.

The primary objectives of this research were to extract and characterize anthocyanins from V. floribundum and R. glaucus, microencapsulate the extracts using maltodextrin as a carrier agent, and to evaluate the biological activities of the microencapsulated products. Specifically, we aim to assess the antibacterial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic effects of the microencapsulated anthocyanins to determine their potential applications in the development in functional foods and pharmaceutical development.

The microencapsulation process was carried out using a spray-drying method with maltodextrin as the encapsulating agent. The resulting microcapsules were characterized using FTIR and SEM to determine their chemical and morphological properties. The biological activities of the microencapsulated anthocyanins were assessed through a series of assays evaluating their antibacterial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory effects.

This study provides valuable insights into the effectiveness of microencapsulation in preserving the functional properties of anthocyanins and emphasizes the potential health benefits of these bioactive compounds. By demonstrating the enhanced the bioactivity of microencapsulated anthocyanins, this research highlights their applicability in the development of novel pharmaceutical and nutraceutical products.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Chemical Characterization and Antioxidant Activity

The phytochemical composition and antioxidant potential of V. floribundum and R. glaucus fruits were assessed by quantifying their total polyphenol content (TPC), anthocyanin levels, and antioxidant activity via the DPPH assay.

The comparative analysis of

V. floribundum and

R. glaucus in

Table 1 reveals significant differences in their bioactive compounds and antioxidant capacities. Specifically,

V. floribundum exhibited a total polyphenol content of 354 ± 25.16 mg/g fresh weight, substantially higher than

R. glaucus’s 294 ± 24.03 mg/g. Similarly, the anthocyanin content in

V. floribundum was 79.67 mg/100g, surpassing

R. glaucus’s 53.3 mg/100g. These differences are reflected in their antioxidant activities, with

V. floribundum demonstrating a stronger capacity (83.5 ± 19.40 µg/mL) compared to

R. glaucus (167.92 ± 39.57 µg/mL).

In comparison with existing literature, studies have reported high polyphenol and anthocyanin contents in

V. floribundum, which supports its classification as a "superfruit" due to its potent antioxidant properties [

8]. For instance, similar studies on

V. floribundum have found total polyphenol contents ranging from 150 to 300 mg/100g and anthocyanin levels between 35 to 300 mg/100g, aligning closely with the present data [

9]. These compounds contribute significantly to its high antioxidant activity, which is essential for its health-promoting properties.

Although previous literature has reported polyphenol contents of approximately 400 mg/100 g for some

Rubus species, we found that the polyphenol content was 294 ± 24.03 mg/100 g. This indicates a lower value, which is also reflected in the low anthocyanin content (53.3 mg/100 g) [

10,

11]. Such differences can be explained by variations in cultivation conditions, altitude, maturation, and other factors, as previously described by some authors [

12,

13].

Given their high concentration of polyphenols and anthocyanins, berries hold potential for pharmacological applications, in the treatment of diseases associated with oxidative stress and inflammation, which have demonstrated potential cancer chemopreventive activity, as confirmed by human clinical trials [

14,

15]

In terms of antioxidant potential, both berries showed up to 43.7-fold less DPPH scavenging activity than the ascorbic acid control (IC

50 3.84±0.92 µg/mL), however,

V. floribundum exhibited a 2-fold higher anthocyanin content than

R. glaucus. The higher polyphenol and anthocyanin contents in

V. floribundum correlate with the enhanced antioxidant activity determined by the DPPH assay. The superior antioxidant activity of

V. floribundum was also observed in our previous study of non-microencapsulated berries [

16]; however, in that study the IC

50 values for the two fruits were very similar and at least 3.8-fold lower than in the current study. This suggests that the microencapsulation process or the removal of the maltodextrin prior to the DPPH scavenging determination affected the overall antioxidant potential [

17,

18]. Interestingly, the literature often highlights the benefits of microencapsulation to preserve the antioxidant activity of natural extracts [

19,

20,

21]. Therefore, additional antioxidant studies using other methods that are compatible with the maltodextrin matrix should be explored to confirm these findings.

2.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) Analysis

The FTIR spectra analysis of non-microencapsulated and microencapsulated anthocyanins extracted from

Vaccinium floribundum (Andean blueberry) and

Rubus glaucus (Andean blackberry) provides significant insights into the structural and functional properties of these compounds. The presence of characteristic peaks indicative of various functional groups offers a comprehensive understanding of the anthocyanins’ chemical composition and the impact of microencapsulation, as summarized in

Table 2 and

Table 3, and illustrated in

Supplementary Material Figures S1 and S2.

The analysis confirmed successful microencapsulation of anthocyanins from both berry species, with the presence and modification of key functional group peaks in the FTIR spectra verifying the encapsulation process. As shown in

Figure S1 and

Table 2 and

Table 3, the FTIR spectra of anthocyanins in panel A depict the non-microencapsulated extracts, while panel B represents the microencapsulated microspheres for both

V. floribundum and

R. glaucus. Notably, distinct bands were observed around 1637 cm⁻

1 and 1635 cm⁻

1 in the extracts, corresponding to the O-H stretching of polyphenols. In the microencapsulated anthocyanins, these bands were significantly reduced or absent, indicating an efficient encapsulation process that likely reduces the exposure of reactive groups, thus enhancing stability against environmental stressors such as pH, temperature, and light exposure [24].

The O-H stretching region, commonly associated with hydroxyl groups in phenolic compounds, showed significant changes upon encapsulation (

Table 2 and

Table 3). In the non-microencapsulated samples of

V. floribundum and

R. glaucus, the O-H stretching peaks were pronounced and of high intensity, reflecting the presence of free hydroxyl groups. In contrast, the microencapsulated samples exhibited reduced peak intensities, suggesting that these groups were less exposed due to their interaction with the maltodextrin matrix. This retention of key functional groups, including hydroxyl, alkyl, and phenolic groups, indicates that the encapsulation process does not significantly alter the chemical structure of the anthocyanins, which is critical for maintaining their antioxidant properties and potential applications [

22,

23]. The protective effect is crucial for enhancing the stability and longevity of anthocyanins in functional applications, such as food and nutraceutical products.

Distinct differences were observed in the C-H stretching region between the non-microencapsulated and microencapsulated forms of both berries, as detailed in

Table 2 and

Table 3. In the non-microencapsulated samples, the C-H peaks were either absent or of low intensity, indicating minimal presence in the anthocyanins. However, medium-intensity peaks were observed in the microencapsulated samples, attributed to maltodextrin. This confirms the presence of the encapsulating agent and supports the successful incorporation of maltodextrin into the anthocyanin structure, reinforcing the effectiveness of the encapsulation process.

Carbonyl stretching peaks, associated with C=O groups in anthocyanins, showed high intensity in the non-microencapsulated forms of both berries, as seen in

Table 2 and

Table 3. These peaks were notably reduced in the microencapsulated samples, suggesting interactions between the carbonyl groups and the maltodextrin matrix, likely through hydrogen bonding. This interaction partially shields the carbonyl groups, contributing to enhanced stability by reducing the reactivity of these groups and preventing degradation [25]. The reduction in exposure of these reactive groups supports the protective role of encapsulation, which may prevent degradation processes common in non-encapsulated anthocyanins.

The aromatic C=C stretching peaks, indicative of the aromatic rings in anthocyanins, were medium in intensity in the non-microencapsulated samples (

Table 2 and

Table 3). Encapsulation led to a reduction in the intensity of these peaks, indicating that the aromatic rings are partially protected by the maltodextrin matrix. This decreased exposure suggests that encapsulation decreases the exposure of these structurally significant components, thereby preserving the integrity of the anthocyanins during storage and use, which is essential for maintaining their antioxidant properties.

Both non-microencapsulated and microencapsulated samples exhibited C-O and C-O-C stretching peaks, with the microencapsulated samples showing lower intensities (

Table 2 and

Table 3). These differences suggest interactions between the anthocyanins and the encapsulating maltodextrin matrix, affecting the ether and glycosidic bonds and enhancing the stabilization of these functional groups. The introduction of new peaks in the microencapsulated spectra, corresponding to the encapsulating materials, suggests effective protection and stabilization of anthocyanins. This encapsulation likely enhances the stability of anthocyanins, protecting them from degradation due to environmental stressors such as pH, temperature, and light exposure [

24].

A distinct C-O-C stretching peak, associated with polysaccharides and maltodextrin, was absent in the non-microencapsulated samples but appeared prominently in the microencapsulated forms of both berry extracts (

Table 2 and

Table 3). This peak serves as direct evidence of successful encapsulation, highlighting the presence and incorporation of maltodextrin within the anthocyanin microspheres.

The combined FTIR analysis, as detailed in

Table 2 and

Table 3 and

Supplementary Figures S1 and S2, demonstrates that maltodextrin encapsulation significantly alters the structural environment of anthocyanins in both

R. glaucus and

V. floribundum. The reduction in the intensity of key anthocyanin peaks and the appearance of new peaks related to maltodextrin confirm the successful encapsulation process. Scientific literature corroborates these findings, highlighting that encapsulation can introduce new vibrational modes and mask or shift original anthocyanin peaks. The observed shifts in O-H stretching and masking of aromatic C=C stretching further indicate interactions between anthocyanins and encapsulating materials, potentially leading to improved stability and controlled release [

25]. Encapsulation effectively shields anthocyanins from environmental degradation, supporting their functional properties and making it a valuable technique for improving the bioactive potential of berry extracts in food and nutraceutical applications. Future studies, including stability tests and release profiles, will further validate the benefits and applications of microencapsulated anthocyanins in various industries.

2.3. Morphological Analysis by Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

Morphological analysis using SEM is a well-established technique widely used to characterize microencapsulated spheres, such as those prepared with maltodextrin using spray drying methods. SEM imaging provides valuable insights into particle size, shape, and surface morphology, which are essential for evaluating encapsulation efficiency, stability, and potential applications in food and pharmaceutical formulations [

26,

27].

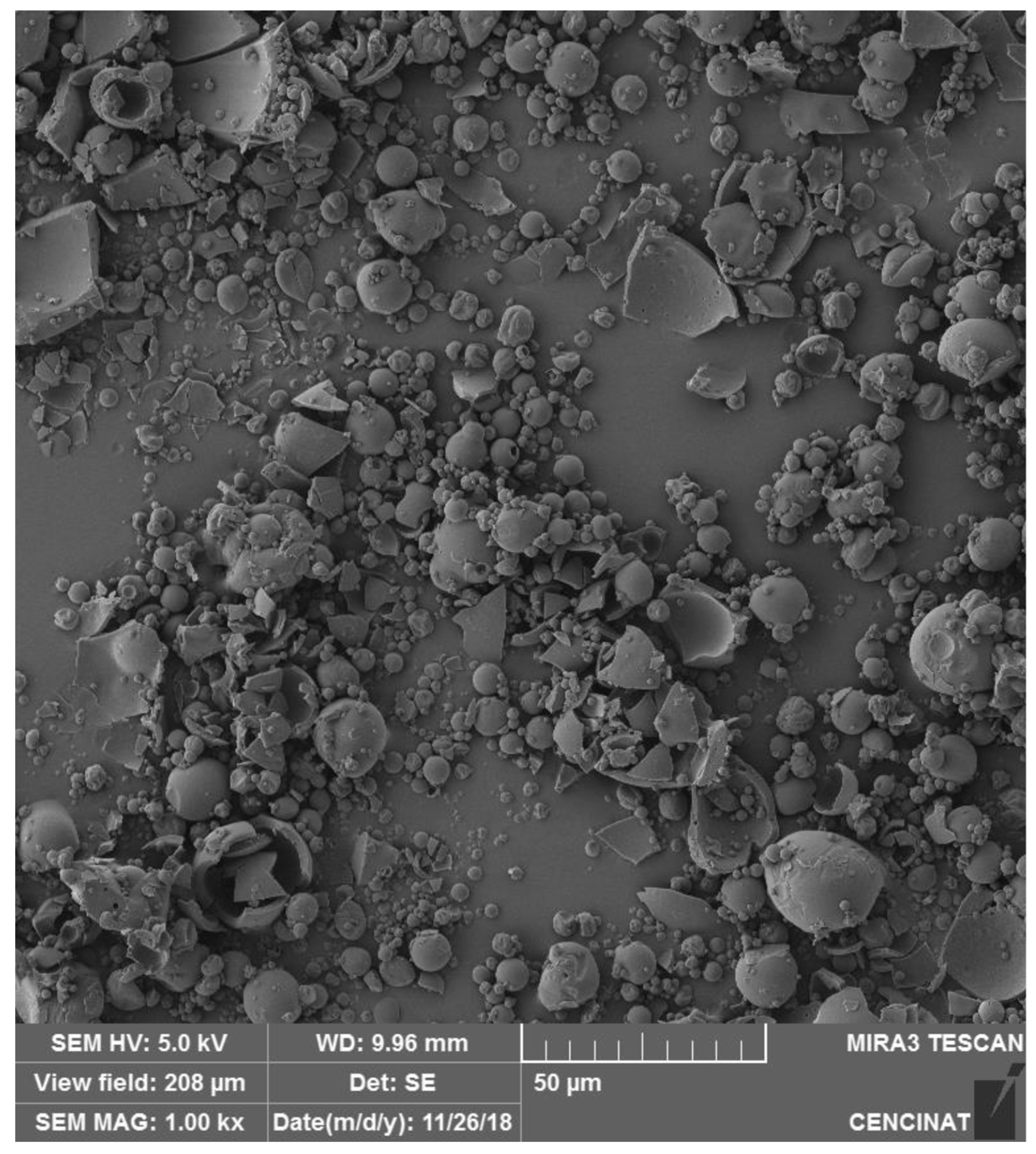

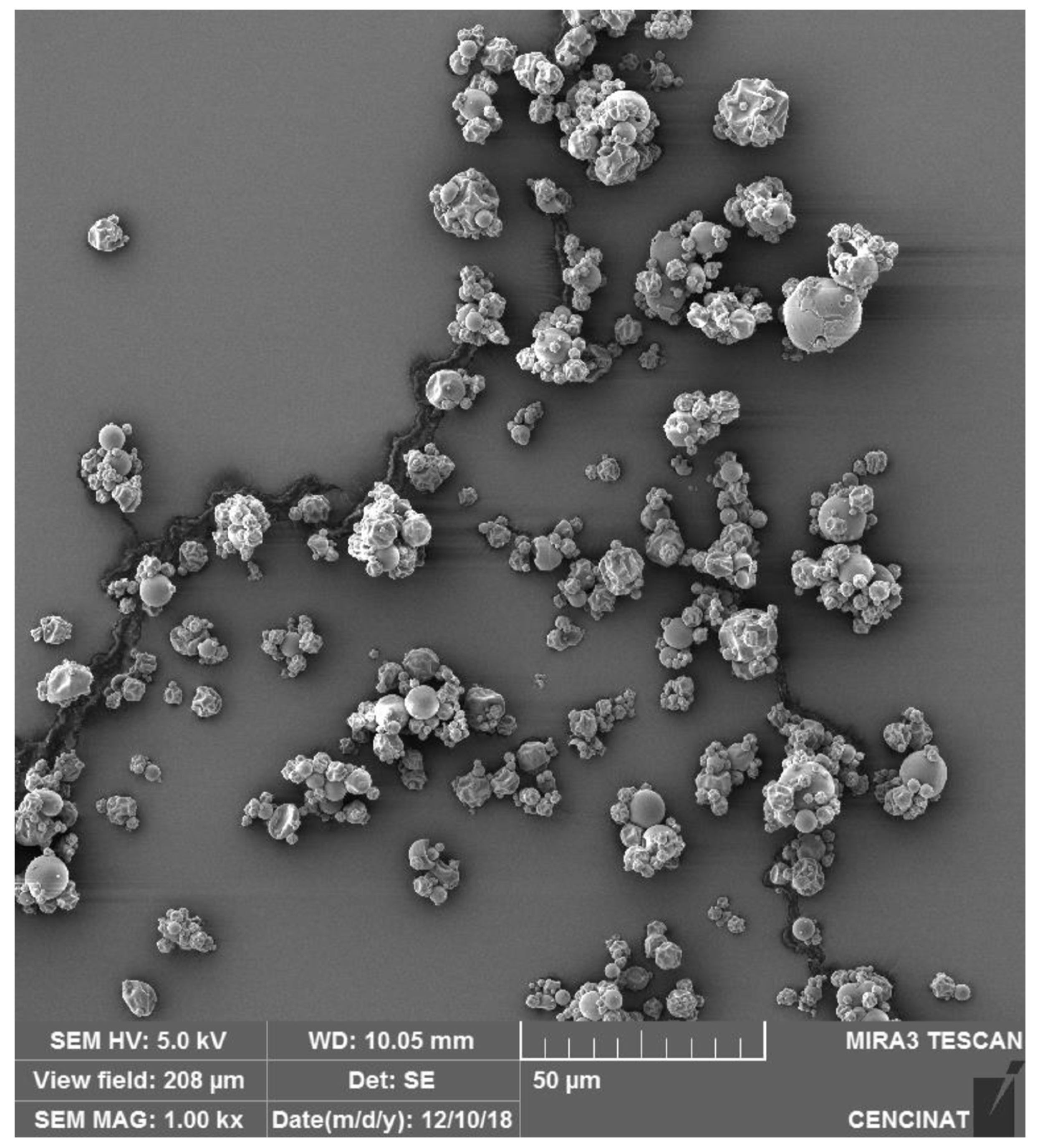

SEM analysis of microencapsulated spheres, as seen in the studies of both

V. floribundum and

Rubus glaucus, reveals that the spray drying process produces predominantly spherical particles with varying degrees of uniformity and occasional agglomeration. In the case of

R. glaucus, the SEM images (

Figure 1) captured at 1.00 kx magnification (with a scale bar of 50 µm) showed mostly aggregated spherical particles with smooth surfaces, indicative of successful encapsulation. However, some particles appear clustered or fused, likely reflecting the influence of suboptimal drying conditions. Similarly, the SEM analysis of

V. floribundum spheres (

Figure 2) also highlights a heterogeneous distribution of particle sizes and shapes. Predominantly spherical particles are observed, but some irregular fragments and broken or agglomerated particles suggest variations in droplet sizes or drying rates.

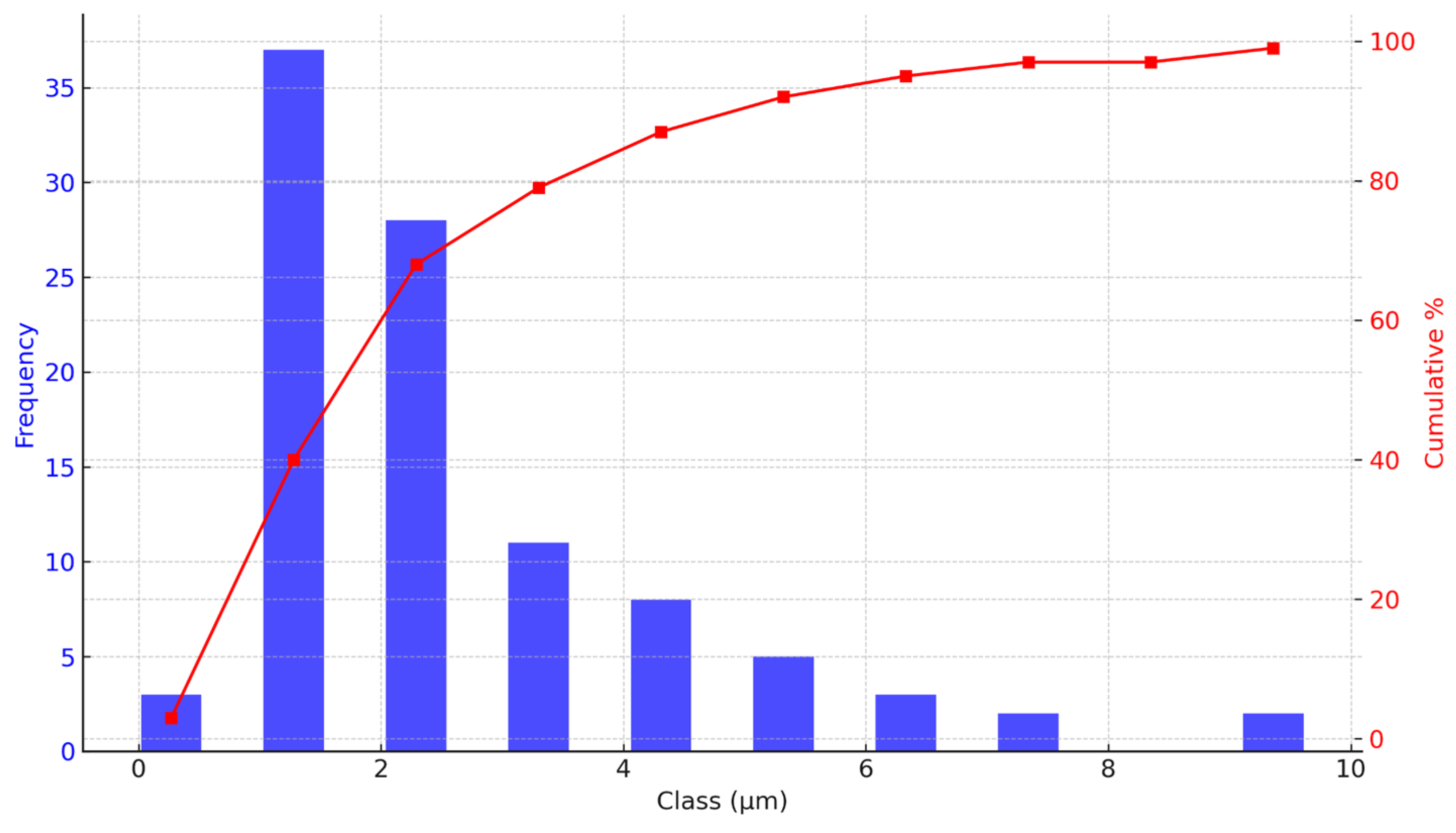

Quantitative analysis using FIJI software for particle size distribution of both samples confirmed a positively skewed histogram. For

V. floribundum, the histogram (

Figure 3) shows a peak at 1.28 µm, indicating the most frequent particle size, while the mean particle size is 2.65 µm with a standard deviation of 1.82 µm. The particle sizes range from as small as 0.27 µm to over 9 µm, but larger particles are less frequent. The cumulative size distribution curve indicates that approximately 40% of the particles are smaller than 1.28 µm, with a steep rise between 1.28 and 3.30 µm, confirming that a majority fall within this range. These results suggest that the encapsulation process predominantly produces small to medium-sized particles with moderate variability in sizes.

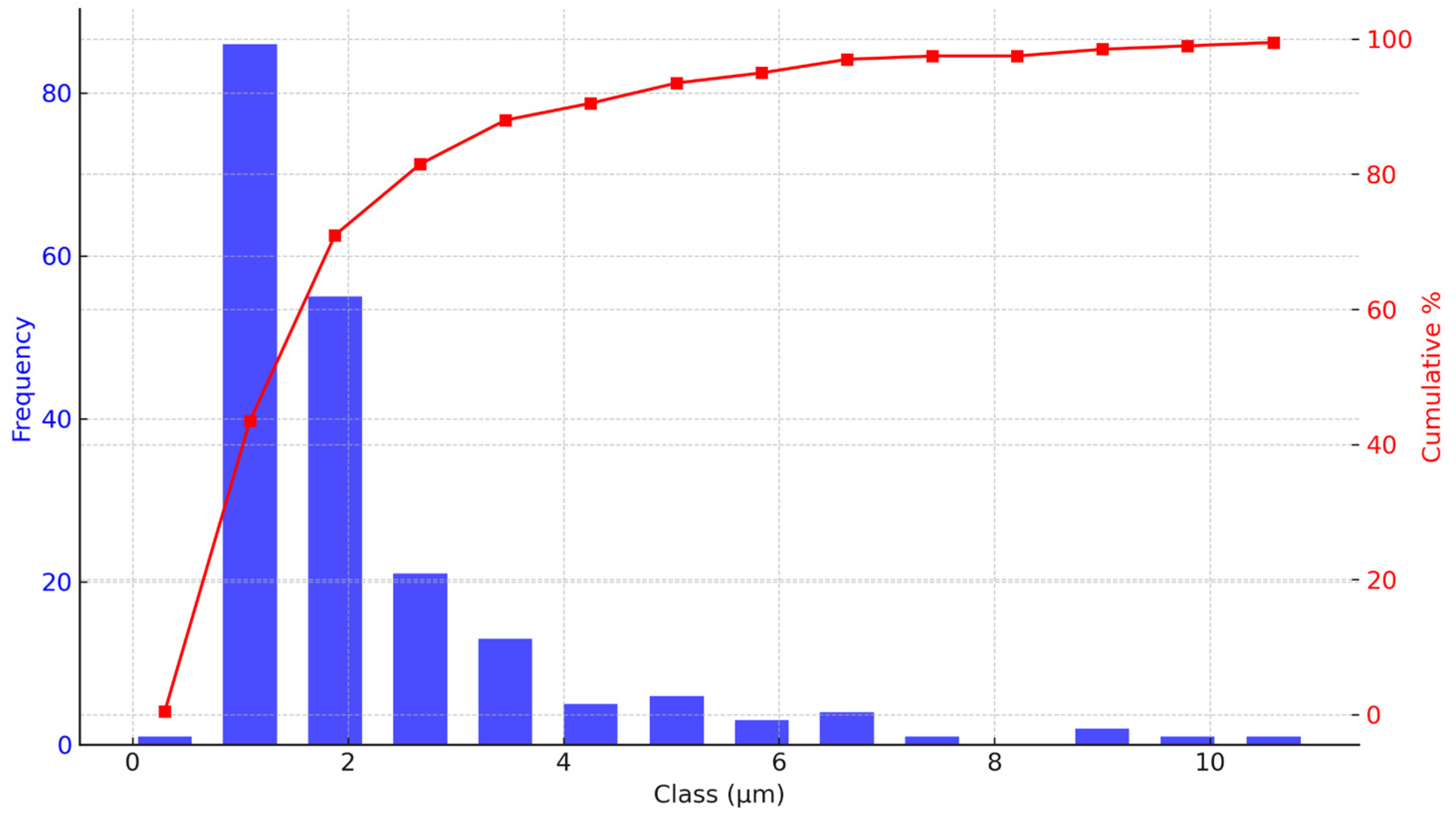

Similarly, the particle size distribution of

R. glaucus (

Figure 4) shows a mode at 1.09 µm, with a mean size of 2.21 µm and a standard deviation of 1.70 µm. The range extends from 0.3 µm to over 10 µm, with most particles below 2 µm. The cumulative size distribution indicates that about 80% of the particles are smaller than 3 µm, consistent with the presence of fine particles, while a plateau beyond 5 µm suggests minimal larger particles. This trend parallels that of

V. floribundum, demonstrating that both encapsulation processes yield predominantly fine particles, though with slight differences in the size ranges and distributions.

Factors like feed concentration, drying temperature, and atomization rate can be optimized to minimize aggregation and improve the uniformity of the encapsulated product [

28]. Achieving a more consistent particle size distribution would enhance product quality, particularly for applications requiring rapid dissolution or high surface area [

29,

30].

Overall, SEM analysis proves invaluable for understanding the morphology and size distribution of microencapsulated particles. These findings are essential for evaluating the encapsulation efficiency and stability of the microencapsulated product. Smaller particle sizes are generally advantageous for applications requiring rapid dissolution or dispersion, such as in food or pharmaceutical formulations [

31,

32]. The relatively narrow size distribution and predominance of fine particles indicate effective spray drying parameters, though there remains potential for process optimization. Reducing the presence of larger or fragmented particles could enhance product uniformity. Adjustments to feed concentration, drying temperature, or atomization rate might be necessary to improve overall encapsulation quality and particle size consistency [

33,

34].

2.4. Antibacterial Activity

The antibacterial activity of microencapsulated anthocyanin extracts from

R. glaucus and

V. floribundum, prepared via spray drying with maltodextrin, was evaluated against a panel of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial strains using the agar-well diffusion method. The results, shown in

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, demonstrated a concentration-dependent antibacterial effect for both extracts, with variations depending on the bacterial strain tested. Notable, maltodextrin at the maximum concentration tested (550 mg/mL) did not show any antibacterial effect which is consistent with previous reports [

35], highlighting that the growth inhibition seen for the microencapsulated extracts is derived from the extract itself.

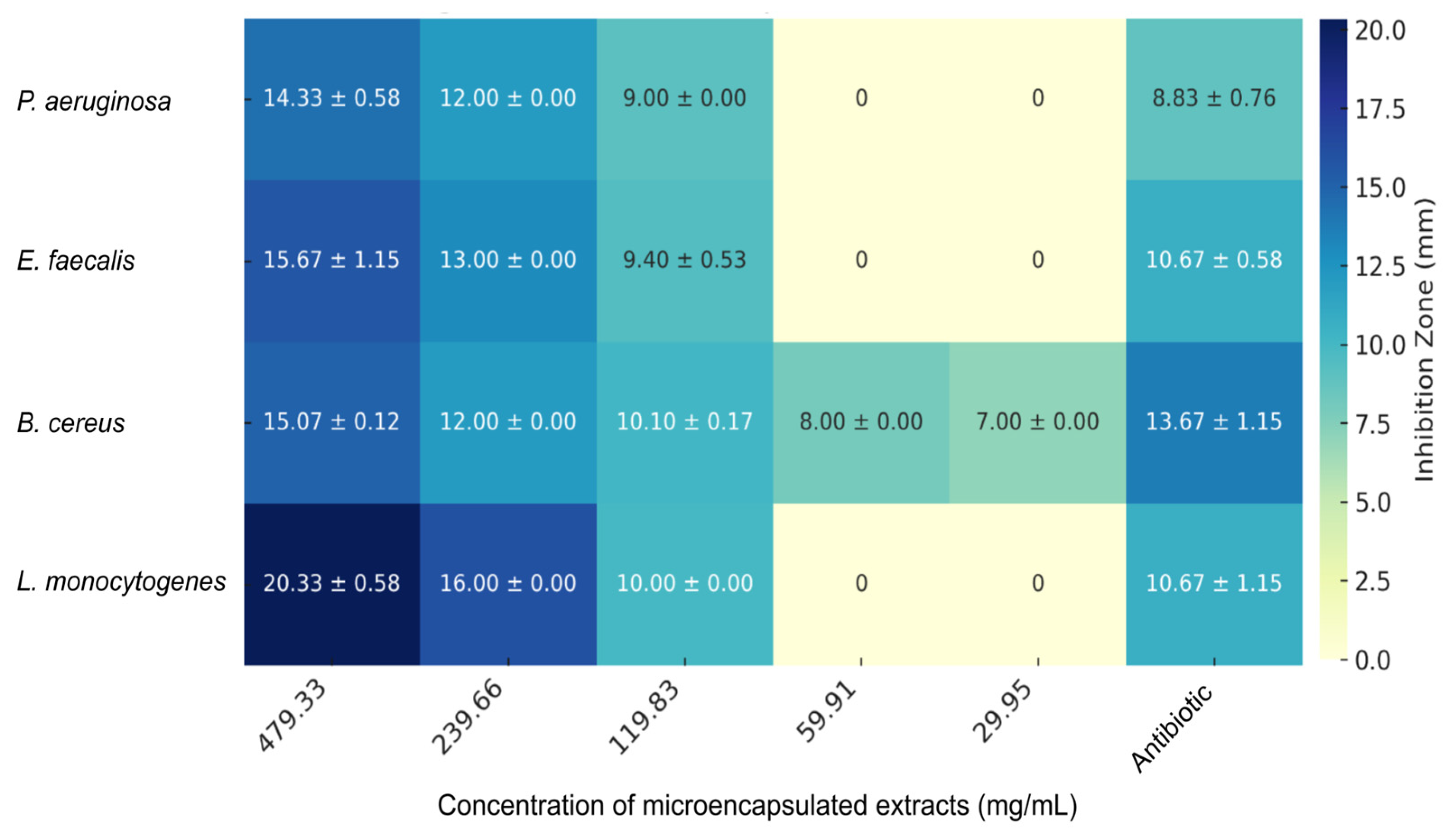

Figure 5 shows the antimicrobial efficacy of the microencapsulated

R. glaucus extract against various bacterial strains, with inhibition zones (in mm) and their corresponding standard deviations displayed as a heatmap. At the highest concentration tested (479.33 mg/mL), the extract exhibits significant inhibitory effects against

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (14.33 ± 0.58 mm),

Enterococcus faecalis (15.67 ± 1.15 mm),

Bacillus cereus (15.07 ± 0.12 mm), and

Listeria monocytogenes (20.33 ± 0.58 mm).

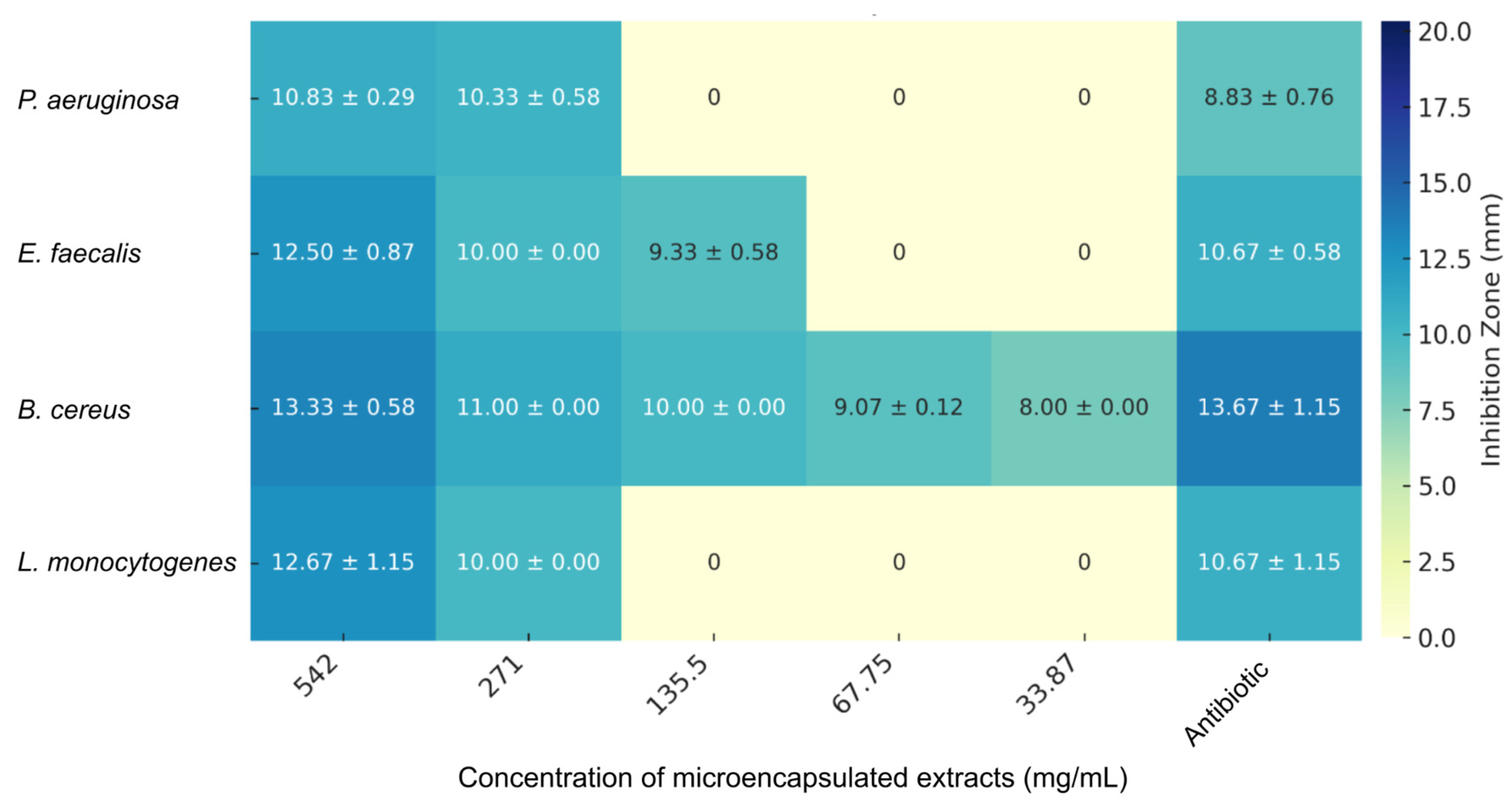

Figure 6 presents the antimicrobial activity of the microencapsulated

V. floribundum extract, showing inhibition zones across different concentrations and bacterial strains, along with their standard deviations. At the highest concentration tested (542 mg/mL), the

V. floribundum extract exhibits inhibitory effects against

P. aeruginosa (10.83 ± 0.29 mm),

E. faecalis (12.50 ± 0.87 mm),

B. cereus (13.33 ± 0.58 mm), and

L. monocytogenes (12.67 ± 1.15 mm). Although the inhibition zones for

P. aeruginosa (10.83 ± 0.29 mm) and

E. faecalis (12.50 ± 0.87 mm) are greater than those produced by the corresponding antibiotics (8.83 ± 0.76 mm and 10.67 ± 0.58 mm, respectively), these results must be considered in the context of the much higher concentration of the extract. The

V. floribundum extract demonstrates moderate activity against

L. monocytogenes (12.67 ± 1.15 mm), which, while less effective than the

R. glaucus extract, still exceeds the inhibition of carbenicillin.

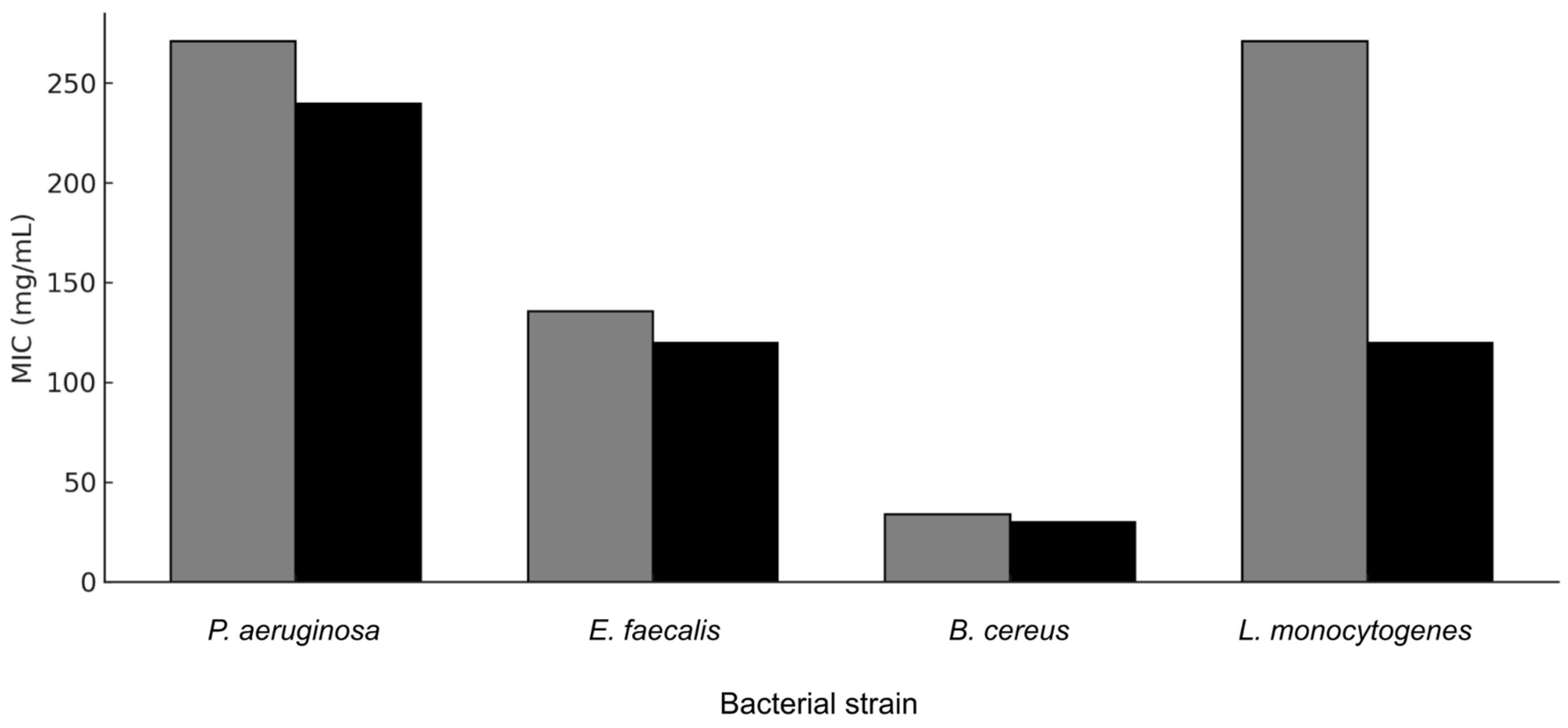

Figure 7 provides a clustered bar chart comparing the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) values of both microencapsulated extracts against the tested bacterial strains. The MIC data indicate that the

R. glaucus extract generally has lower MIC values across all tested bacteria, suggesting higher antimicrobial potency compared to

V. floribundum. For example, the MIC of

R. glaucus against

E. faecalis is 119.83 mg/mL, compared to 135.5 mg/mL for

V. floribundum. Similarly, the MIC against

P. aeruginosa is 239.66 mg/mL for

R. glaucus versus 271 mg/mL for

V. floribundum. The lowest MIC values are observed for

B. cereus, with MICs below 29.95 mg/mL for

R. glaucus and below 33.87 mg/mL for

V. floribundum, highlighting their strong inhibitory effect against this Gram-positive bacterium which is aligned to previous research [

36].

The comparison in

Figure 7 also shows that both extracts have relatively high MIC values against

P. aeruginosa (239.66 mg/mL for

R. glaucus and 271 mg/mL for

V. floribundum), indicating that this strain is less susceptible to the microencapsulated anthocyanins. However, the

R. glaucus extract consistently demonstrates a more effective inhibitory effect, with lower MIC values overall, reinforcing its potential as a more potent antimicrobial agent of the two extracts studied. In prior evaluations of the extracts without microencapsulation, consistently lower MIC values were also observed for

R. glaucus compared to

V. floribundum [16].

These findings suggest that while both microencapsulated extracts exhibit promising antimicrobial activity, particularly at high concentrations, their efficacy compared to antibiotics is limited by the much higher concentrations required to achieve similar effects. Tetracycline and carbenicillin, as pure antibiotics, achieve bacterial inhibition at significantly lower concentrations due to its high purity and specific mode of action; these findings are also consistent with previous literature. For example, anthocyanins generally require higher concentrations to achieve comparable effects to antibiotics like ciprofloxacin, as their mode of action is less targeted and involves multiple biochemical pathways [

37]. The data in

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 emphasize the need to optimize the bioactive components in these extracts, potentially through purification or synergistic combinations with other antimicrobials, to enhance their potency and reduce the required concentrations for effective use.

The antimicrobial mechanisms of anthocyanins often involve interactions with bacterial cell membranes, increasing permeability and causing structural damage. This mechanism is more effective against Gram-positive bacteria due to the absence of an outer membrane, which contrasts with Gram-negative bacteria that have a protective lipopolysaccharide layer. Such differences in membrane structure partly explains the higher MICs observed against Gram-negative strains in our study and similar findings previously reported [

38].

Overall, these results underscore the potential of R. glaucus and V. floribundum extracts as alternative or complementary antimicrobial agents, particularly in settings where natural products are preferred or where antibiotic resistance is a concern. Future studies should focus on refining the extraction and encapsulation processes, increasing the concentration of active compounds, and investigating synergistic effects with conventional antibiotics to maximize therapeutic efficacy.

2.5. Antitumoral Activity

R. glaucus and

V. floribundum are important sources of bioactive compounds, including anthocyanins and polyphenols, which are known for their ability to eliminate free radicals that can damage cells, strengthen the immune system, and potentially reduce the risk or incidence of cancer [

39]. Dose-response curves were employed to calculate the inhibitory concentration values (IC

50), which indicate the concentration of a substance required to inhibit cell proliferation by 50% (

Table 4).

These values serve as a key indicator of the efficacy of the microencapsulated extracts, with lower IC

50 values indicating higher potency against specific cell lines. The results show a clear difference in the antitumor efficacy between

R. glaucus and

V. floribundum. The IC

50 values for the microencapsulated

R. glaucus extract range from 3.07 to 5.03 mg/mL, suggesting a higher potency in inhibiting tumor cell proliferation compared to

V. floribundum, which has IC

50 values ranging from 8.15 to 15.59 mg/mL. Corresponding concentrations of anthocyanins are indicated for the IC

50 of each microencapsulation (

Table S1), highlighting the role of these bioactive compounds in contributing to the observed cytotoxic effects. Despite

V. floribundum’s higher antioxidant potential (

Table 1),

R. glaucus proves more potent at lower concentrations. This disparity implies that antioxidant activity alone does not correlate with antitumoral potency; factors such as bioavailability or specific molecular interactions in

R. glaucus likely enhance its tumor inhibition. In prior evaluations of the extracts without microencapsulation, consistently lower IC

50 values were also observed for

R. glaucus compared to

V. floribundum, except in MDA-MB-231 cells [

16]. Additionally, maltodextrin alone reflected negligible toxic effects on cells (

Table S2). This confirms that maltodextrin had no significant impact on cell viability, ensuring the observed effects are due to the active compounds and not the encapsulation material. Conversely, for non-tumor cells (NIH3T3),

R. glaucus exhibited an IC

50 of 4.32 mg/mL, while

V. floribundum showed a significantly higher IC

50 of 10.44 mg/mL, potentially leading to better therapeutic outcomes.

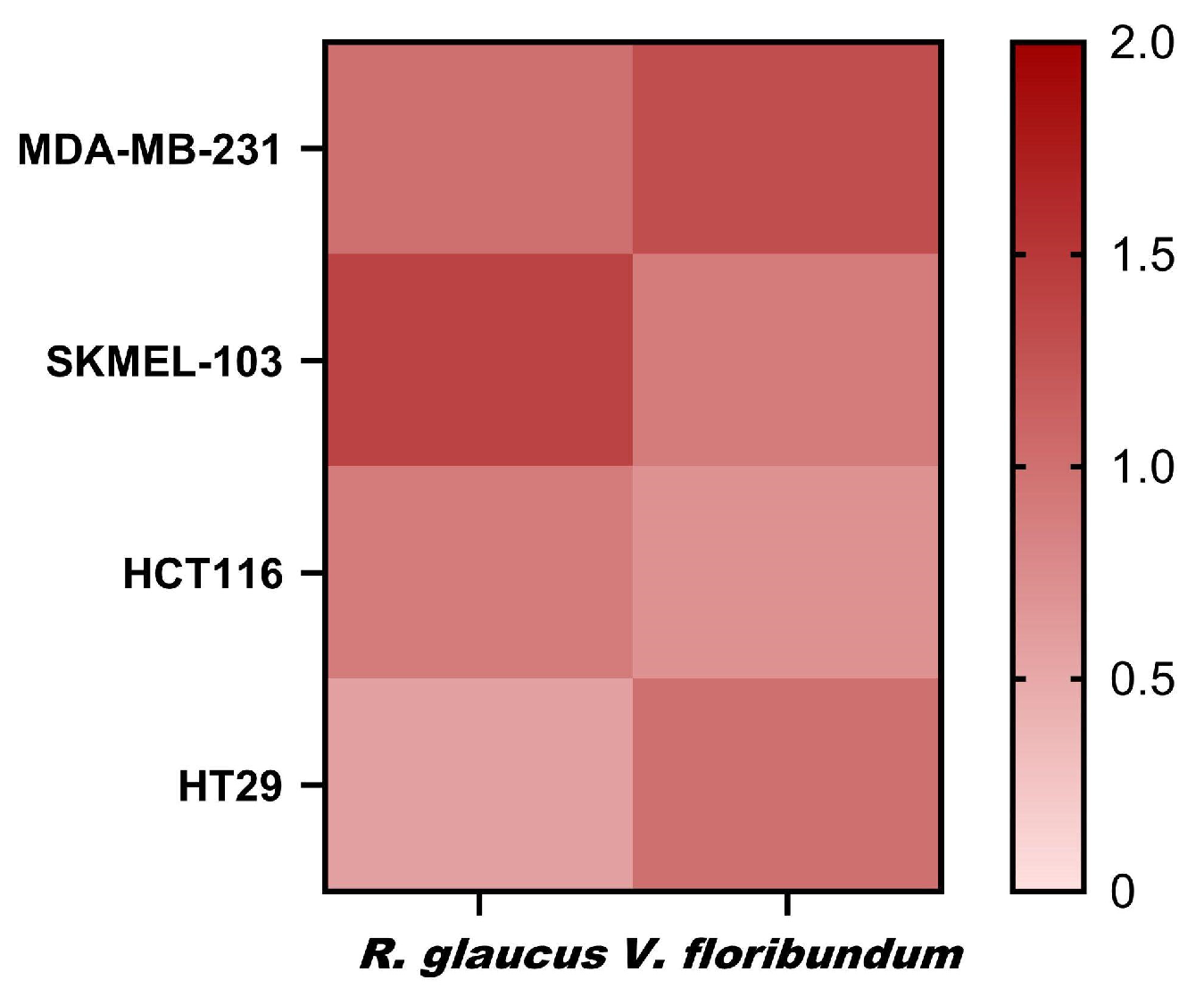

Based on the IC

50 values for non-tumor cells compared to those for tumor cells, the therapeutic indexes (TI) were calculated (

Figure 8). A higher TI reflects a more favorable therapeutic profile, characterized by effective inhibition of tumor cells with minimal impact on healthy cells. The TI values for

R. glaucus (0.57–1.40) and

V. floribundum (0.70–1.30) reveal that both microencapsulations exhibit similar profiles, suggesting a comparable therapeutic window. The highest TI for

V. floribundum is observed in breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231), while

R. glaucus shows promising TI values in melanoma (SKMEL-103). However, both microencapsulations exhibit relatively low TI values across the tested cell lines. This suggests a narrow therapeutic window and raises concerns about the potential cytotoxicity to healthy cells alongside their anti-tumor effects. In summary, while the TI values indicate that further optimization is necessary to enhance the therapeutic potential,

R. glaucus shows lower IC

50 values for tumor cells, indicating higher potency.

Microencapsulation has proven to be a promising strategy to enhance the stability and efficacy of bioactive compounds, protecting them from degradation by controlling their reactivity, photosensitivity, and durability before they reach the tumor site while allowing for controlled release to ensure sustained therapeutic effects over time [

40]. Importantly, this strategy not only preserves the compound’s potency but also enhances bioavailability by improving absorption and cellular uptake, as demonstrated in studies on anthocyanins, which are crucial for the antitumor effects of berries [

41,

42]. For instance, A. Kazan et al. reported that encapsulation of

V. floribundum extracts with chitosan resulted in lower IC

50 values in an osteosarcoma cell line, although similar benefits were not observed in other tumor cell lines tested [

43]. Microencapsulation of different fruit extracts, such as tamarillo, has shown dose-dependent cytotoxic effects on various cancer cell lines, with encapsulation conditions significantly influencing IC

50 values and thereby impacting anticancer efficacy due to variability in phytochemical retention [

44]. Additionally, the microencapsulation of a

Gratiola officinalis extract has been shown to significantly reduce viability in breast cancer cells without inducing the formation of autophagosomes, which are indicators of antitumor resistance [

45]. While microencapsulation can enhance cellular uptake, its effects are more pronounced with longer incubation times and in vivo settings. The choice of matrix and encapsulation techniques may significantly influence the antitumor efficacy of the extracts [

46,

47].

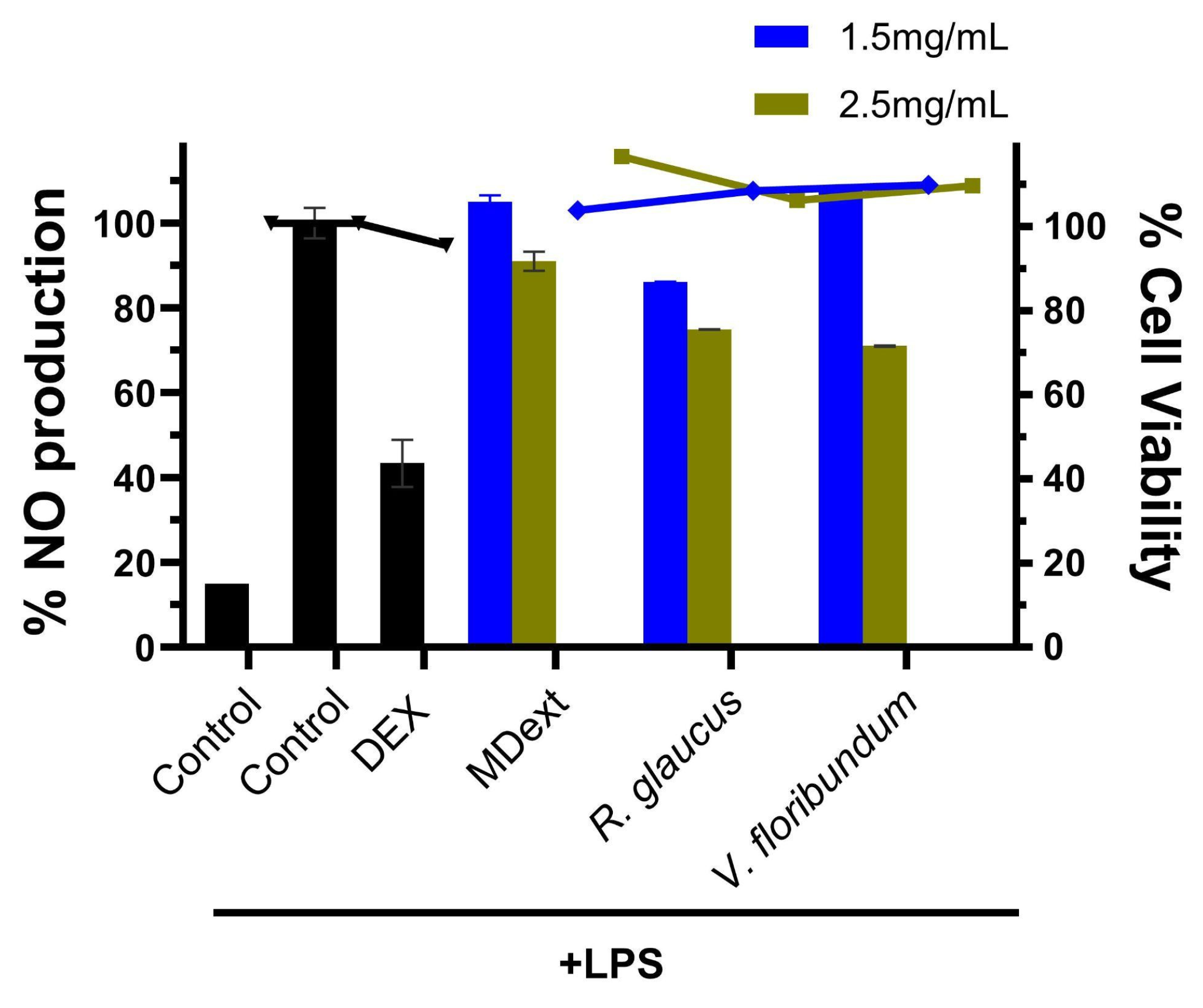

2.6. Antiinflammatory Activity

Inflammation is a primary defense response to harmful stimuli, and plant extracts have been shown to inhibit pro-inflammatory mediators involved in this process [

48]. The anti-inflammatory potential of microencapsulated

R. glaucus and

V. floribundum extracts was assessed by measuring nitric oxide (NO) production in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells (

Figure 9). Pretreatment with 2.5 mg/mL of microencapsulated extracts for 4 hours before LPS stimulation reduced NO production to 74.9% for

V. floribundum and 71% for

R. glaucus compared to the LPS-only control. This reduction indicates the anti-inflammatory properties of these extracts, as excessive NO production is a recognized marker of inflammation [

49]. Importantly, cell viability assays confirmed that microencapsulation did not compromise cell health, with viability exceeding 90% in all treated groups, thereby ensuring that the reduction in NO was due to anti-inflammatory activity rather than cell death. Furthermore, the effectiveness of the extracts was demonstrated when compared to dexamethasone, a standard anti-inflammatory drug. At lower concentrations, microencapsulated R. glaucus showed a NO reduction of up to 86.1%, while

V. floribundum did not show positive results. Higher concentrations could not be tested due to cell growth inhibition. Additionally, maltodextrin alone reduced NO production to 91% of the control.

The anti-inflammatory effects are attributed to bioactive compounds such as anthocyanins and polyphenols, which are known to scavenge free radicals and inhibit inflammatory pathways [

50]. Microencapsulation likely preserved and enhanced the bioactivity and stability of these compounds, consistent with existing research on their benefits in reducing inflammation and oxidative stress [

51]. The significant reduction in NO production observed in this study aligns with the documented anti-inflammatory effects of these bioactive molecules and extracts [

52]. Overall, our results suggest that microencapsulation enhances the anti-inflammatory effects of the extracts [

16].

3. Methods

3.1. Plant Material

Berries were acquired from a local market in Ambato, Ecuador and transported immediately to laboratory, where the fruits were visually selected for uniformity in size, maturity degree and without defects. Then the fruits were washed with tap water, disinfected with a 100-ppm chlorine solution, and then freeze-dried and grinded. The samples were stored at −20 °C and utilized for the experiments in this study.

3.2. Anthocyanin Extraction

Ethanolic extracts were prepared according to Perez et al., 2021 with some modifications: the ground material was mixed with twenty times its volume of a solution consisting of 96% ethanol and 1.5 M HCl in an 85:15

v/v ratio. This mixture was added to a stirrer tank and subjected to extraction at 70°C for 60 minutes. The solid components were separated from the mixture using a Rotine 380 centrifuge (Germany). The extract was then transferred to a 500 ml flask, continuously stirred, and subsequently subjected to rotary evaporation in a water bath at 70°C for 2 hours under vacuum to remove the solvent [

53].

3.3. Quantification of Total Anthocyanins and Phenolic Compounds

The total anthocyanin content in the lyophilized extract was determined using the differential pH method described by Lee et al. 2005 [

54]. This method employs two buffer systems: potassium chloride at pH 1.0 and 0.025 mol/L, and sodium acetate at pH 4.5 and 0.4 mol/L. The absorbance of the fruit extract was measured at 515 nm and 700 nm in both buffer solutions. The absorbance difference was calculated using the formulas:

Where: A = absorbance, MW = molecular weight, DF = dilution factor, ε = extinction coefficient. Data were calculated using the MW (449.20) and the extinction coefficient for cyanidin-3-glucoside (29,600) and expressed as mg cyanidin/100 g lyophilized Rubus robustus C. Presl.

The total phenolic content (TPC) was determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent with catechin as the standard [

55]. Briefly, 1 ml of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (FCR) and 0.8 ml of 7.5% sodium carbonate were combined with 0.2 ml of the sample extract. The mixture was shaken and incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes. The absorbance was then measured at 765 nm. A calibration curve with gallic acid standards ranging from 50 to 250 μg/ml was used to quantify the TPC, expressed as micrograms of gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per gram of sample. Each measurement was performed in triplicate.

3.4. Microencapsulation

Carrier agents for spray drying, specifically maltodextrin (10-20 DE), were obtained from Roig Farma, Spain. The carrier agent (maltodextrin 10-20 DE) was mixed with the pigment concentrate (27% solid content) in a ratio of 20:80 anthocyanins to maltodextrin, equating to 20 g of anthocyanins. To this mixture, 280 ml of distilled water was added, and it was stirred to homogeneity using an Ika mixer (RH Digital, Germany).

The feed mixtures were spray-dried using a Büchi mini spray dryer (B 290, Switzerland) at air inlet/outlet temperatures of 150°C/90°C. The resulting powder was collected in a collection flask. The pigment powders were stored in HDPE-aluminum bags at 15-25°C.

3.5. Characterization by FTIR

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was used to analyze the functional groups present in the microcapsules. The FTIR spectra were recorded on a JASCO FTIR 4100 spectrometer (Japan) using the ATR method, covering the wave number range of 4000–500 cm⁻1 with a resolution of 4 cm⁻1 over 36 scans.

3.6. Morphological Analysis by Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

Each sample was mounted on a stub for electron microscopy using conductive double-sided carbon tape. The samples were then coated with approximately 20 nm of conductive gold (99.99% purity) for 60 seconds using a Quorum Q150R ES sputtering evaporator. The micrographs were taken with a TESCAN MIRA 3 Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) using the Secondary Electron (SE) detector.

Images were analyzed using the biological-image analysis platform Fiji [

56]. Area data was obtained from the images using Fiji. Diameter of each sphere was calculated using the formula:

where D is the diameter and A is the area obtained from Fiji.

3.7. Antibacterial Activity

The microencapsulated extract’s antibacterial activity was evaluated against the Gram-positive bacteria Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923, Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212, Bacillus cereus; Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 13932, and the Gram-negative bacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853, Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Salmonella enterica ATCC 14028, Klebsiella ozaenae, and Enterobacter gergoviae.

Stock solutions of the microencapsulated anthocyanins were prepared by independently dissolving 479 mg of microencapsulated

R. glaucus extract powder and 542 mg of microencapsulated

V. floribundum extract powder in 1 mL of sterile distilled water. These values correspond to the maximum solubility of the microencapsulated samples. Importantly, the stock concentrations of both microencapsulated samples equate to 0.667 mg of anthocyanins alone. Maltodextrin alone was used as negative control at a final concentration of 550 mg/mL. Tetracycline (10 µg/mL) was used as a control to inhibit

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, while carbenicillin (100 µg/mL) served as a control against

Enterococcus faecalis,

Bacillus cereus, and

Listeria monocytogenes. These antibiotics were chosen due to their known effectiveness against the corresponding bacterial strains [

57].

Antibacterial activity assessment was conducted using the agar-well diffusion method [

58]. For this purpose, the bacterial inoculum was spread on Mueller Hinton agar, and wells of 6 mm diameter were punched. Then, each well was filled with either 80 µl of the microencapsulated extract stock or the controls. The plates were incubated overnight at 37 °C. Lastly, the antibacterial potential was determined by measuring the diameter (in mm) of the inhibition area and compared to the diameter of the antibiotic at the standard concentration. Each assay was performed in triplicate.

Once the bacterial strains that were inhibited by the microencapsulated extracts at their maximum concentrations (542 mg/mL and 479 mg/mL) were determined, a second round of analysis by well-agar diffusion was conducted to narrow down the inhibitory concentration. Each well was filled with 80 µl of a microencapsulated extract dilution. For this purpose, the berries stock solutions were serially diluted up to four times to yield concentrations ranging from 33.88 to 542 mg/mL and 29.95 to 479 mg/mL, respectively. The plates were incubated overnight at 37 °C, after which the inhibition area was measured and reported in millimeters. Each assay consisted of three technical and three biological replicates.

3.8. Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

The Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) for each bacterial strain was determined through a series of dilutions of the microencapsulated extracts from Rubus glaucus and Vaccinium floribundum. Stock solutions were prepared at the maximum solubility levels, 479 mg/mL for R. glaucus and 542 mg/mL for V. floribundum. These solutions were then serially diluted four times, resulting in concentrations ranging from 29.95 to 479 mg/mL for R. glaucus and from 33.88 to 542 mg/mL for V. floribundum. The diluted samples were tested against bacterial strains using the agar-well diffusion method, and the MIC was defined as the lowest concentration at which no visible bacterial growth was observed after overnight incubation at 37°C.

3.9. Antitumoral Activity

Four tumoral cell lines, MDA-MB-231 (human breast adenocarcinoma, ATCC No. HTB-26), SK-MEL-3 (human melanoma ATCC No. HTB-69), HCT116 (human breast adenocarcinoma, ATCC No. CCL-247), and HT29 (human colorectal adenocarcinoma, ATCC No. HTB-38), and one non-tumoral cell line, NIH3T3 (mouse NIH/Swiss embryo fibroblasts), were obtained from ATCC and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM/F12) (Corning, Corning in Manassas, VA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Eurobio, Les Ulis, France) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Gibco, Miami, FL, USA). All cell lines were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere at 5% CO2. To analyze the effect of the extracts on cell proliferation, cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well in 100 μL in 96-well plates. Cells were incubated for 72 hours with 100 μL of the microencapsulated extracts of R. glaucus and V. floribundum at 0.6 - 42 mg/mL of microencapsulation (0.78 - 50 μg/mL final concentrations of anthocyanins). The effect of maltodextrin, the encapsulating agent, was also evaluated using the same method utilizing 100 μL of the compound at 0.6 - 167 mg/mL final concentrations. Following the specified incubation period, the thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay was performed as previously described [60,61]. In summary, 10 μL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL) was added to each well. After allowing 1-2 hours for incubation in a humidified environment, the media was aspirated, and 50 μL of DMSO was added to each well to dissolve the formazan crystals. The mixture was agitated for 5 minutes before measuring the absorbance at 570 nm using a Cytation5 multi-mode detection system (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA). Each data point was obtained from quadruplicate samples, and the experiment was replicated at least four times. Cells only with media were used as negative controls and chemotherapeutic agent cisplatin (50 μg/mL) was used as a positive control in all experimental designs. To determine the concentration of the compound required to inhibit 50% of cell proliferation (IC50), dose-response curves were generated in GraphPad Prism 10.2 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) using the control group of untreated cells as 100% cell proliferation.

3.10. Antiinflammatory Activity

RAW264.7 murine macrophage cells were obtained from ATCC and cultured in RPMI (Corning, Corning in Manassas, VA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Eurobio, Les Ulis, France) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Gibco, Miami, FL, USA). Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. To analyze the anti-inflammatory effects of R. glaucus and V. floribundum, RAW264.7 cells were cultured in 24 well plates at a concentration of 4 × 105 cells per well. The macrophage cells were first exposed for 4 h to the microencapsulated extracts at concentrations 1.5-2.5 mg/ml before being stimulated for 18 h with 1 μg/mL of lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Also, dexamethasone (DEX) (0.5 μg/mL) and maltodextrin (1.5-2.5 mg/ml) were included in the assay. After the treatment, supernatants were collected to assess nitric oxide (NO) production using the Griess reagent system as previously described [62]. Specifically, 50 µL of Griess reagent was added to 50 µL of each supernatant, and the mixture was incubated for 10 minutes at room temperature in the dark. NO production is indicated by the intensity of color produced from the reaction between the culture medium and the Griess reagent. Absorbance was measured at 540 nm using a Cytation5 multimode detection system (BioTek). Cells stimulated only with LPS were used as positive control for inflammation (NO production), LPS+dexamethasone was used as the positive control for anti-inflammatory activity, and cells incubated only with media were used as negative control. The concentrations of the compounds used for the assay were chosen based on their IC50 values and did not significantly affect cell growth. The assay was performed at least in triplicate.

3.11. Antioxidant Activity

To determine the antioxidant activity of microencapsulated extracts, maltodextrin was first removed from the samples. From each microencapsulated extract, 1.5 g was dissolved in 12.5 mL of sterile distilled water (stock solution). Then, 1 mL of the stock was mixed with 9 mL of 100% methanol and incubated with rotation for 30 min at RT. The samples were centrifuged at 2800 rcf for 10 min. The supernatant was collected, and the process was repeated twice with the pellet. The final concentration of the extract without maltodextrin was adjusted to 6 mg/mL with 100% methanol and then used to assess antioxidant activity.

Antioxidant activity was then assessed by the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay according to Barba-Ostria et al. (2024) [

16]. The following formula was used to calculate the %DPPH scavenging activity:

IC50 values were calculated using the GraphPad Prism version 10.2 (GraphPad Software, Corp). All the results are given as a mean ± standard deviation (SD) of experiments done at least in triplicate.

4. Conclusion

This study provides comprehensive insights into the bioactive properties of microencapsulated anthocyanins derived from V. floribundum (Andean blueberry) and R. glaucus (Andean blackberry). The use of microencapsulation, a technique involving the entrapment of bioactive compounds within a protective matrix, has proven effective in enhancing the stability, bioavailability, and biological activity of these anthocyanin-rich extracts.

The microencapsulated extracts exhibited significant antioxidant activity, as demonstrated by their ability to scavenge free radicals in the DPPH assay. Notably, V. floribundum showed higher polyphenol and anthocyanin contents, which correlate with its superior antioxidant activity seen.

The antibacterial properties of the microencapsulated extracts were evaluated against a panel of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial strains. Both extracts demonstrated a concentration-dependent antimicrobial effect, with R. glaucus generally showing higher potency, as indicated by lower MIC values across several bacterial strains. These results suggest that these microencapsulated extracts could serve as potential natural alternatives or complements to conventional antibiotics, particularly in contexts where resistance to standard treatments is a concern. However, the need for higher concentrations compared to pure antibiotics highlights the necessity for further optimization to enhance their efficacy.

The study also explored the cytotoxic and antitumor activities of the microencapsulated extracts. The microencapsulated R. glaucus extract demonstrated greater potency in inhibiting tumor cell proliferation, as evidenced by lower IC50 values across various cancer cell lines, compared to V. floribundum. However, V. floribundum exhibited a more favorable therapeutic index (TI), indicating a safer profile due to its selective toxicity towards cancer cells while sparing normal cells. These findings suggest that while both extracts hold promise for anticancer applications, V. floribundum may offer a safer therapeutic option, particularly when minimizing cytotoxicity to healthy cells is a priority.

In addition to their antioxidant, antibacterial, and antitumor activities, the microencapsulated extracts demonstrated notable anti-inflammatory effects. The reduction of nitric oxide (NO) production in LPS-stimulated macrophages indicates that both extracts possess significant anti-inflammatory properties. R. glaucus showed a greater reduction in NO levels, further reinforcing its potential as a potent anti-inflammatory agent. Importantly, the preservation of cell viability throughout these assays confirmed that the observed anti-inflammatory effects were due to the bioactive compounds themselves rather than cytotoxicity.

Overall, this study highlights the effectiveness of microencapsulation in preserving and enhancing the functional properties of anthocyanins, which are critical for their health-promoting effects. The microencapsulated extracts of V. floribundum and R. glaucus exhibit a broad spectrum of biological activities, including antioxidant, antibacterial, anticancer, and anti-inflammatory effects, underscoring their potential applications in developing functional foods and pharmaceuticals. Future research should focus on optimizing encapsulation conditions, exploring synergistic combinations with other bioactives, and conducting in vivo studies to fully realize the therapeutic potential of these natural compounds.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: FTIR Spectral Curves of Anthocyanins from Vaccinium floribundum.; Figure S2: FTIR Spectral Curves of Anthocyanins from Rubus glaucus; Table S1: Corresponding anthocyanin concentrations (µg/mL) in microencapsulated extracts at the IC50 values for tumor and non-tumor cell lines after 72 hours; Table S2: Inhibitory concentration values (IC20) of maltodextrin against tumor and non-tumor cell lines at 72 h.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used Conceptualization, L.G.B. and C.B.-O.; methodology, L.G.B., C.B.-O., R.G.-P., F.C.-S., S.E.C.-P., O.L., J.Z.-M., A.D.; formal analysis, L.G.B., C.B.-O., R.G.-P., F.C.-S., S.E.C.-P., O.L., J.Z.-M., A.D; data curation, L.G.B., C.B.-O., R.G.-P., F.C.-S., S.E.C.-P., O.L., J.Z.-M., A.D; writing—original draft preparation, L.G.B., C.B.-O., R.G.-P., F.C.-S., S.E.C.-P., O.L., J.Z.-M., A.D; writing—review and editing, L.G.B., C.B.-O., R.G.-P., F.C.-S., S.E.C.-P., O.L., J.Z.-M., A.D; supervision, L.G.B. and C.B.-O.; project administration, L.G.B. and C.B.-O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All tables were created by the authors. All sources of information were adequately referenced. There was no need to obtain copyright permission.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nandane, A.S.; Ranveer, R.C. Antioxidative effects of subtropical fruits rich in anthocyanins. In Anthocyanins in subtropical fruits: chemical properties, processing, and health benefits; CRC Press: New York, 2023; pp. 149–159. ISBN 9781003242598. [Google Scholar]

- Câmara, J.S.; Locatelli, M.; Pereira, J.A.M.; Oliveira, H.; Arlorio, M.; Fernandes, I.; Perestrelo, R.; Freitas, V.; Bordiga, M. Behind the Scenes of Anthocyanins-From the Health Benefits to Potential Applications in Food, Pharmaceutical and Cosmetic Fields. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aniket Chikane; Payal Rakshe; Jagruti Kumbhar; Aniket Gadge; Sandesh More A review on anthocyanins: coloured pigments as food, pharmaceutical ingredients and the potential health benefits. IJSRST 2022, 547–550. [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, S.; Mani, S.; Chaturvedi, N. Anthocyanin extraction, purification and therapeutic properties on human health - a review. jptcp 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, Z.; Tang, S.; Li, Z.; Chou, S.; Shu, C.; Chen, Y.; Chen, W.; Yang, S.; Yang, Y.; Tian, J.; Li, B. An updated review on the stability of anthocyanins regarding the interaction with food proteins and polysaccharides. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Safety 2022, 21, 4378–4401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Balandrano, D.D.; Chai, Z.; Beta, T.; Feng, J.; Huang, W. Blueberry anthocyanins: An updated review on approaches to enhancing their bioavailability. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 118, 808–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Lee, S.G.; Shin, J.H. Effects of encapsulation methods on bioaccessibility of anthocyanins: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 639–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llivisaca-Contreras, S.A.; León-Tamariz, F.; Manzano-Santana, P.; Ruales, J.; Naranjo-Morán, J.; Serrano-Mena, L.; Chica-Martínez, E.; Cevallos-Cevallos, J.M. Mortiño (Vaccinium floribundum Kunth): An Underutilized Superplant from the Andes. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golovinskaia, O.; Wang, C.-K. Review of functional and pharmacological activities of berries. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellappan, S.; Akoh, C.C.; Krewer, G. Phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity of Georgia-grown blueberries and blackberries. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 2432–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer, R.A.; Hummer, K.E.; Finn, C.E.; Frei, B.; Wrolstad, R.E. Anthocyanins, phenolics, and antioxidant capacity in diverse small fruits: vaccinium, rubus, and ribes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzulker, R.; Glazer, I.; Bar-Ilan, I.; Holland, D.; Aviram, M.; Amir, R. Antioxidant activity, polyphenol content, and related compounds in different fruit juices and homogenates prepared from 29 different pomegranate accessions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 9559–9570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiguro, K.; Kuranouchi, T.; Kai, Y.; Katayama, K. Comparison of anthocyanin and polyphenolics in purple sweetpotato ( Ipomoea batatas Lam.) grown in different locations in Japan. Plant Prod. Sci. 2022, 25, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, P.; Skaer, C.W.; Stirdivant, S.M.; Young, M.R.; Stoner, G.D.; Lechner, J.F.; Huang, Y.-W.; Wang, L.-S. Beneficial regulation of metabolic profiles by black raspberries in human colorectal cancer patients. Cancer Prev Res (Phila Pa) 2015, 8, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-S.; Burke, C.A.; Hasson, H.; Kuo, C.-T.; Molmenti, C.L.S.; Seguin, C.; Liu, P.; Huang, T.H.-M.; Frankel, W.L.; Stoner, G.D. A phase Ib study of the effects of black raspberries on rectal polyps in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Cancer Prev Res (Phila Pa) 2014, 7, 666–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba-Ostria, C.; Carrera-Pacheco, S.E.; Gonzalez-Pastor, R.; Zuñiga, J.; Mayorga-Ramos, A.; Tejera, E.; Guamán, L. Exploring the Multifaceted Biological Activities of Anthocyanins Isolated from Two Andean Berries. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otálora, M.C.; Wilches-Torres, A.; Gómez Castaño, J.A. Spray-Drying Microencapsulation of Andean Blueberry (Vaccinium meridionale Sw.) Anthocyanins Using Prickly Pear (Opuntia ficus indica L.) Peel Mucilage or Gum Arabic: A Comparative Study. Foods 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingua, M.S.; Salomón, V.; Baroni, M.V.; Blajman, J.E.; Maldonado, L.M.; Páez, R. Effect of spray drying on the microencapsulation of blueberry natural antioxidants. In The 1st International Electronic Conference on Food Science and Functional Foods; MDPI: Basel Switzerland, 2020; p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, W.; Chen, W.; Tian, L.; Sun, J.; Lai, C.; Bai, W. Microencapsulation with fructooligosaccharides and whey protein enhances the antioxidant activity of anthocyanins and their ability to modulate gut microbiota in vitro. Food Res. Int. 2024, 181, 114082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, L.; Ji, Q.; Jin, Z.; Guo, T.; Yu, K.; Ding, W.; Liu, C.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, N. Nano-microencapsulation of tea seed oil via modified complex coacervation with propolis and phosphatidylcholine for improving antioxidant activity. LWT 2022, 163, 113550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkowska, A.; Ambroziak, W.; Adamiec, J.; Czyżowska, A. Preservation of Antioxidant Activity and Polyphenols in Chokeberry Juice and Wine with the Use of Microencapsulation. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2017, 41, e12924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.; Koh, E. Effect of encapsulation on stability of anthocyanins and chlorogenic acid isomers in aronia during in vitro digestion and their transformation in a model system. Food Chem. 2024, 434, 137443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millinia, B.L.; Mashithah, D.; Nawatila, R.; Kartini, K. Microencapsulation of roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) anthocyanins: Effects of maltodextrin and trehalose matrix on selected physicochemical properties and antioxidant activities of spray-dried powder. Future Foods 2024, 9, 100300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Cássia Gomes da Rocha, J.; Caroline Buttow Rigolon, T.; Lorrane Rodrigues Borges, L.; Laís Alves Almeida Nascimento, A.; de Andrade Neves, N.; tuler Perrone, Í.; Stephani, R.; César Stringheta, P. Anthocyanin stability in a mix of phenolic extracts microencapsulated by maltodextrine, whey protein and gum arabic. JFNR 2023, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula da Silva Dos Passos, A.; Madrona, G.S.; Marcolino, V.A.; Baesso, M.L.; Matioli, G. The Use of Thermal Analysis and Photoacoustic Spectroscopy in the Evaluation of Maltodextrin Microencapsulation of Anthocyanins from Juçara Palm Fruit (Euterpe edulis Mart.) and Their Application in Food. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2015, 53, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottenmuller, A.; Théodon, L.; Debayle, J.; Vélez, D.T.; Tourbin, M.; Frances, C.; Gavet, Y. Granulometric analysis of maltodextrin particles observed by scanning electron microscopy. In 2023 IEEE 13th International Conference on Pattern Recognition Systems (ICPRS); IEEE, 2023; pp. 1–7.

- Li, Z.; Sun, B.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, L.; Huang, Y.; Lu, M.; Zhu, X.; Gao, Y. Effect of maltodextrin on the oxidative stability of ultrasonically induced soybean oil bodies microcapsules. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1071462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perković, G.; Planinić, M.; Šelo, G.; Martinović, J.; Nedić, R.; Puš, M.; Bucić-Kojić, A. Optimisation of the encapsulation of grape pomace extract by spray drying using goat whey protein as coating material. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhuritha Rokkam; Anil Kumar Vadaga A brief review on the current trends in microencapsulation. JOPIR 2024, 2, 108–114. [CrossRef]

- Aslam, S.; Khan, R.S.; Maqsood, S.; Khalid, N. Application of nano/microencapsulated ingredients in drinks and beverages. In Application of nano/microencapsulated ingredients in food products; Elsevier, 2021; pp. 105–169 ISBN 9780128157268.

- Kalkumbe, A. MICROENCAPSULATION: A REVIEW. IRJMETS 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Kim, S.-R. Microencapsulation for pharmaceutical applications: A review. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2024, 7, 692–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.Q.; Nguyen, T.H.; Mounir, S.; Allaf, K. Effect of feed concentration and inlet air temperature on the properties of soymilk powder obtained by spray drying. Drying Technology 2017, 36, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Halling Laier, C.; Sonne Alstrøm, T.; Travers Bargholz, M.; Bjerg Sjøltov, P.; Rades, T.; Boisen, A.; Nielsen, L.H. Evaluation of the effects of spray drying parameters for producing cubosome powder precursors. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2019, 135, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, B.; Cruces, R.; Perez, A.; Fernandez-Cruz, A.; Guembe, M. Activity of maltodextrin and vancomycin against staphylococcus aureus biofilm. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2018, 10, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande-Tovar, C.; Araujo Pabón, L.; Flórez López, E.; Aranaga Arias, C. Determinación de la actividad antioxidante y antimicrobiana de residuos de mora (Rubus glaucus Benth). Inf. Téc. 2020, 85, 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzón, G.A.; Soto, C.Y.; López-R, M.; Riedl, K.M.; Browmiller, C.R.; Howard, L. Phenolic profile, in vitro antimicrobial activity and antioxidant capacity of Vaccinium meridionale swartz pomace. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llivisaca, S.; Manzano, P.; Ruales, J.; Flores, J.; Mendoza, J.; Peralta, E.; Cevallos-Cevallos, J.M. Chemical, antimicrobial, and molecular characterization of mortiño (Vaccinium floribundum Kunth) fruits and leaves. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 6, 934–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paczkowska-Walendowska, M.; Gościniak, A.; Szymanowska, D.; Szwajgier, D.; Baranowska-Wójcik, E.; Szulc, P.; Dreczka, D.; Simon, M.; Cielecka-Piontek, J. Blackberry Leaves as New Functional Food? Screening Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory and Microbiological Activities in Correlation with Phytochemical Analysis. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudrić, J.; Ibrić, S.; Đuriš, J. Microencapsulation methods for plants biologically active compounds: A review. Lek. sirovine 2018, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaiee, S.; Assadpour, E.; Faridi Esfanjani, A.; Silva, A.S.; Jafari, S.M. Application of nano/microencapsulated phenolic compounds against cancer. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 279, 102153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, F.; Ebrahimi, S.N.; Pereira, D.M.; Estevinho, B.N.; Rocha, F. Preliminary studies of microencapsulation and anticancer activity of polyphenols extract from peels. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2022, 100, 3240–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazan, A.; Sevimli-Gur, C.; Yesil-Celiktas, O.; Dunford, N.T. In vitro tumor suppression properties of blueberry extracts in liquid and encapsulated forms. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2017, 243, 1057–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Hamid, N.; Liu, Y.; Kam, R.; Kantono, K.; Wang, K.; Lu, J. Bioactive Components and Anticancer Activities of Spray-Dried New Zealand Tamarillo Powder. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navolokin, N.; Lomova, M.; Bucharskaya, A.; Godage, O.; Polukonova, N.; Shirokov, A.; Grinev, V.; Maslyakova, G. Antitumor Effects of Microencapsulated Gratiola officinalis Extract on Breast Carcinoma and Human Cervical Cancer Cells In Vitro. Materials (Basel) 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, N.; Khoshnoudi-Nia, S.; Jafari, S.M. Nano/microencapsulation of anthocyanins; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Food Res. Int. 2020, 132, 109077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aftab, A.; Ahmad, B.; Bashir, S.; Rafique, S.; Bashir, M.; Ghani, T.; Gul, A.; Shah, A.U.; Khan, R.; Sajini, A.A. Comparative study of microscale and macroscale technique for encapsulation of Calotropis gigantea extract in metal-conjugated nanomatrices for invasive ductal carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondua, M.; Njoya, E.M.; Abdalla, M.A.; McGaw, L.J. Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of leaf extracts of eleven South African medicinal plants used traditionally to treat inflammation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 234, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J.N.; Al-Omran, A.; Parvathy, S.S. Role of nitric oxide in inflammatory diseases. Inflammopharmacology 2007, 15, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathod, N.B.; Elabed, N.; Punia, S.; Ozogul, F.; Kim, S.-K.; Rocha, J.M. Recent Developments in Polyphenol Applications on Human Health: A Review with Current Knowledge. Plants 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachuau, L.; Laldinchhana; Roy, P.K.; Zothantluanga, J.H.; Ray, S.; Das, S. Encapsulation of bioactive compound and its therapeutic potential. In Bioactive natural products for pharmaceutical applications; Pal, D., Nayak, A. K., Eds.; Advanced Structured Materials; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; Vol. 140, pp. 687–714. ISBN 978-3-030-54026-5.

- Bhatt, S.C.; Naik, B.; Kumar, V.; Gupta, A.K.; Kumar, S.; Preet, M.S.; Sharma, N.; Rustagi, S. Untapped potential of non-conventional rubus species: bioactivity, nutrition, and livelihood opportunities. Plant Methods 2023, 19, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, B.P.; Endara, A.B.; Garrido, J.A.; Ramírez Cárdenas, L. de los Á. Extraction of anthocyanins from Mortiño (Vaccinium floribundum) and determination of their antioxidant capacity. Rev. Fac. Nac. Agron. Medellín 2021, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrolstad, R.E.; Durst, R.W.; Lee, J. Tracking color and pigment changes in anthocyanin products. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2005, 16, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. [14] Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of folin-ciocalteu reagent. In Oxidants and Antioxidants Part A; Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier, 1999; Vol. 299, pp. 152–178 ISBN 9780121822002.

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; Tinevez, J.-Y.; White, D.J.; Hartenstein, V.; Eliceiri, K.; Tomancak, P.; Cardona, A. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teran, R.; Guevara, R.; Mora, J.; Dobronski, L.; Barreiro-Costa, O.; Beske, T.; Pérez-Barrera, J.; Araya-Maturana, R.; Rojas-Silva, P.; Poveda, A.; Heredia-Moya, J. Characterization of Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, and Leishmanicidal Activities of Schiff Base Derivatives of 4-Aminoantipyrine. Molecules 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, R.R.; Wilson, P. Antibacterial activity of a new, stable, aqueous extract of allicin against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 2004, 61, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI Inoculum Preparation for Dilution Tests. In Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically: Approved standard; CLSI document M07-A9; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, 2012.

- Wang, Y.-C.; Ku, W.-C.; Liu, C.-Y.; Cheng, Y.-C.; Chien, C.-C.; Chang, K.-W.; Huang, C.-J. Supplementation of Probiotic Butyricicoccus pullicaecorum Mediates Anticancer Effect on Bladder Urothelial Cells by Regulating Butyrate-Responsive Molecular Signatures. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Liufang, H.; Shah, S.M.; Ali, F.; Khan, S.A.; Shah, F.A.; Li, J.B.; Li, S. Cytotoxic effects of extracts and isolated compounds from Ifloga spicata (forssk.) sch. bip against HepG-2 cancer cell line: Supported by ADMET analysis and molecular docking. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 986456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eo, H.J.; Jang, J.H.; Park, G.H. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Berchemia floribunda in LPS-Stimulated RAW264.7 Cells through Regulation of NF-κB and MAPKs Signaling Pathway. Plants 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Morphological characterization of R. glaucus anthocyanins microencapsulated particles. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) image of R. glaucus microencapsulated particles produced by spray drying. The image captured using a TESCAN MIRA 3 SEM at 1.00 kx magnification with a 50 µm scale bar.

Figure 1.

Morphological characterization of R. glaucus anthocyanins microencapsulated particles. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) image of R. glaucus microencapsulated particles produced by spray drying. The image captured using a TESCAN MIRA 3 SEM at 1.00 kx magnification with a 50 µm scale bar.

Figure 2.

SEM image of V. floribundum microencapsulated particles prepared by spray drying, captured with a TESCAN MIRA 3 SEM at 1.00 kx magnification and a 50 µm scale bar.

Figure 2.

SEM image of V. floribundum microencapsulated particles prepared by spray drying, captured with a TESCAN MIRA 3 SEM at 1.00 kx magnification and a 50 µm scale bar.

Figure 3.

Particle size distribution analysis of V. floribundum microencapsulated spheres. Particle size distribution and cumulative distribution curve of V. floribundum microencapsulated spheres, measured using FIJI software. The histogram exhibits a positively skewed distribution with a peak at 1.28 µm. The cumulative curve shows that about 79% of the particles are smaller than 3.30 µm, indicating a concentration of small to medium-sized particles in the sample.

Figure 3.

Particle size distribution analysis of V. floribundum microencapsulated spheres. Particle size distribution and cumulative distribution curve of V. floribundum microencapsulated spheres, measured using FIJI software. The histogram exhibits a positively skewed distribution with a peak at 1.28 µm. The cumulative curve shows that about 79% of the particles are smaller than 3.30 µm, indicating a concentration of small to medium-sized particles in the sample.

Figure 4.

Particle size distribution analysis of R. glaucus microencapsulated spheres. Particle size distribution and cumulative distribution curve of R. glaucus microencapsulated spheres, analyzed using FIJI software. The histogram shows a positively skewed distribution with a mode of 1.09 µm. The cumulative curve indicates that approximately 80% of the particles are smaller than 3 µm, highlighting a predominance of fine particles in the sample.

Figure 4.

Particle size distribution analysis of R. glaucus microencapsulated spheres. Particle size distribution and cumulative distribution curve of R. glaucus microencapsulated spheres, analyzed using FIJI software. The histogram shows a positively skewed distribution with a mode of 1.09 µm. The cumulative curve indicates that approximately 80% of the particles are smaller than 3 µm, highlighting a predominance of fine particles in the sample.

Figure 5.

Antimicrobial activity of microencapsulated R. glaucus anthocyanin extract against different bacterial strains.Heatmap showing the inhibition zones (in mm) with standard deviations for P.s aeruginosa, E. faecalis, B. cereus, and L. monocytogenes at various concentrations (479.33 to 29.95 mg/mL) of the microencapsulated R. glaucus extract. The heatmap illustrates a concentration-dependent inhibition, with notable effectiveness against L. monocytogenes and B. cereus at higher concentrations. Antibiotics were used at the standard concentration.

Figure 5.

Antimicrobial activity of microencapsulated R. glaucus anthocyanin extract against different bacterial strains.Heatmap showing the inhibition zones (in mm) with standard deviations for P.s aeruginosa, E. faecalis, B. cereus, and L. monocytogenes at various concentrations (479.33 to 29.95 mg/mL) of the microencapsulated R. glaucus extract. The heatmap illustrates a concentration-dependent inhibition, with notable effectiveness against L. monocytogenes and B. cereus at higher concentrations. Antibiotics were used at the standard concentration.

Figure 6.

Antimicrobial Activity of Microencapsulated V. floribundum Anthocyanin Extract Against Various Bacterial Strains. The heatmap illustrates the inhibition zones (in mm) with standard deviations for P. aeruginosa, E. faecalis, B. cereus, and L. monocytogenes at different concentrations (ranging from 542 to 33.87 mg/mL) of the microencapsulated V. floribundum extract. The data reveal a concentration-dependent inhibitory effect, with significant antimicrobial activity observed mainly at higher concentrations, particularly against B. cereus. Antibiotics were used at the standard concentration.

Figure 6.

Antimicrobial Activity of Microencapsulated V. floribundum Anthocyanin Extract Against Various Bacterial Strains. The heatmap illustrates the inhibition zones (in mm) with standard deviations for P. aeruginosa, E. faecalis, B. cereus, and L. monocytogenes at different concentrations (ranging from 542 to 33.87 mg/mL) of the microencapsulated V. floribundum extract. The data reveal a concentration-dependent inhibitory effect, with significant antimicrobial activity observed mainly at higher concentrations, particularly against B. cereus. Antibiotics were used at the standard concentration.

Figure 7.

MIC of Microencapsulated R. glaucus and V. floribundum Extracts Against Various Bacterial Strains. The clustered bar chart shows the MIC values (in mg/mL) for each extract against four bacterial strains: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterococcus faecalis, Bacillus cereus, and Listeria monocytogenes. Black bars represent the MIC of the R. glaucus extract, while gray bars correspond to the V. floribundum extract. The results indicate that the R. glaucus extract generally has lower MIC values, suggesting it possesses higher antimicrobial potency compared to the V. floribundum extract.

Figure 7.

MIC of Microencapsulated R. glaucus and V. floribundum Extracts Against Various Bacterial Strains. The clustered bar chart shows the MIC values (in mg/mL) for each extract against four bacterial strains: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterococcus faecalis, Bacillus cereus, and Listeria monocytogenes. Black bars represent the MIC of the R. glaucus extract, while gray bars correspond to the V. floribundum extract. The results indicate that the R. glaucus extract generally has lower MIC values, suggesting it possesses higher antimicrobial potency compared to the V. floribundum extract.

Figure 8.

Therapeutic index (TI) values calculated as the ratio of IC50 of non-tumor cells to the IC50 in tumor cells.

Figure 8.

Therapeutic index (TI) values calculated as the ratio of IC50 of non-tumor cells to the IC50 in tumor cells.

Figure 9.

Anti-inflammatory activity of microencapsulated R. glaucus and V. floribundum extracts. RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with the sample compounds and then stimulated with LPS. The percentage of NO production was calculated using cells treated with LPS only (control + LPS) as 100% NO production (right Y axis). Dexamethasone (DEX) was used as positive control, and cells were incubated only with cell media as negative controls (control). Maltodextrin (MDext) was also included. Bars represent the percentage of NO production (left Y axis). Dots and lines represent the % cell viability for each corresponding data set (right Y axis).

Figure 9.

Anti-inflammatory activity of microencapsulated R. glaucus and V. floribundum extracts. RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with the sample compounds and then stimulated with LPS. The percentage of NO production was calculated using cells treated with LPS only (control + LPS) as 100% NO production (right Y axis). Dexamethasone (DEX) was used as positive control, and cells were incubated only with cell media as negative controls (control). Maltodextrin (MDext) was also included. Bars represent the percentage of NO production (left Y axis). Dots and lines represent the % cell viability for each corresponding data set (right Y axis).

Table 1.

The results of analyses of total polyphenols content (TPC) (gallic acid mg/g fresh weight of fruit), anthocyanins concentrations expressed as cyanidin 3-glucoside, and antioxidant activity (IC50 values corresponding to the DPPH assay expressed in µg/mL anthocyanins) of V. floribundum and R. glaucus.

Table 1.

The results of analyses of total polyphenols content (TPC) (gallic acid mg/g fresh weight of fruit), anthocyanins concentrations expressed as cyanidin 3-glucoside, and antioxidant activity (IC50 values corresponding to the DPPH assay expressed in µg/mL anthocyanins) of V. floribundum and R. glaucus.

| Parameter |

V. floribundum |

R. glaucus |

| Total polyphenols content (TPC) (gallic acid mg/100g fresh weight) |

354 ± 25.16 |

294 ± 24.03 |

| Anthocyanin content (mg/100g) |

79,67 |

53.3 |

| Antioxidant activity of fruit extract (IC50 DPPH assay expressed in µg/mL anthocyanins) |

83.5±19.40 |

167.92±39.57 |

Table 2.

Summary of FTIR Comparative Visual Analysis of Vaccinium floribundum. Table summarizes the comparative visual analysis of FTIR spectra of non-microencapsulated and microencapsulated anthocyanins from Vaccinium floribundum. The table lists key wavenumbers corresponding to functional groups identified in the spectra, along with the qualitative intensity observed in non-microencapsulated and microencapsulated samples.

Table 2.

Summary of FTIR Comparative Visual Analysis of Vaccinium floribundum. Table summarizes the comparative visual analysis of FTIR spectra of non-microencapsulated and microencapsulated anthocyanins from Vaccinium floribundum. The table lists key wavenumbers corresponding to functional groups identified in the spectra, along with the qualitative intensity observed in non-microencapsulated and microencapsulated samples.

| Wavenumber (cm⁻1) |

Functional Group |

Non-Microencapsulated (Qualitative Intensity) |

Microencapsulated

(Qualitative Intensity) |

| 3200–3600 |

O-H stretching (hydroxyl) |

High |

Medium |

| 2800–3000 |

C-H stretching (alkanes) |

- |

Medium |

| 1700–1750 |

C=O stretching (carbonyl) |

High |

Low |

| 1500–1600 |

C=C stretching (aromatic rings) |

Medium |

Low |

| 1000–1300 |

C-O, C-O-C stretching (ethers, glycosidic bonds) |

Medium |

Low |

| 1027 |

C-O-C stretching (polysaccharides) |

- |

Medium |

Table 3.

Summary of FTIR Comparative Visual Analysis of Rubus glaucus. Table presents the results of the comparative visual analysis of FTIR spectra of non-microencapsulated and microencapsulated anthocyanins from Rubus glaucus. The table includes wavenumbers associated with major functional groups and the qualitative intensity of these groups in both non-microencapsulated and microencapsulated samples.

Table 3.

Summary of FTIR Comparative Visual Analysis of Rubus glaucus. Table presents the results of the comparative visual analysis of FTIR spectra of non-microencapsulated and microencapsulated anthocyanins from Rubus glaucus. The table includes wavenumbers associated with major functional groups and the qualitative intensity of these groups in both non-microencapsulated and microencapsulated samples.

| Wavenumber (cm⁻1) |

Functional Group |

Non-Microencapsulated (Qualitative Intensity) |

Microencapsulated (Qualitative Intensity) |

| 3200–3600 |

O-H stretching (hydroxyl) |

High |

Medium |

| 2800–3000 |

C-H stretching (alkanes) |

Low |

Medium |

| 1700–1750 |

C=O stretching (carbonyl) |

Medium |

Low |

| 1500–1600 |

C=C stretching (aromatic rings) |

Medium |

Low |

| 1000–1300 |

C-O, C-O-C stretching (ethers, glycosidic bonds) |

Medium |

Low to Medium |

| 1027 |

C-O-C stretching (polysaccharides) |

- |

Medium |

Table 4.

Inhibitory concentration values (IC50) (mg/mL) of microencapsulated extracts against tumor and non-tumor cell lines at 72 h.

Table 4.

Inhibitory concentration values (IC50) (mg/mL) of microencapsulated extracts against tumor and non-tumor cell lines at 72 h.

| |

MDAMB231 |

SKMEL103 |

HCT116 |

HT29 |

NIH3T3 |

| R. glaucus |

4.16 ± 0.25 |

3.07 ± 0.60 |

5.03 ± 0.09 |

4.76 ± 0.20 |

4.32 ± 0.37 |

| V. floribundum |

8.15 ± 1.67 |

15.46 ± 1.01 |

15.59 ± 3.55 |

10.53 ± 0.22 |

10.44 ± 1.57 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).