1. Introduction

1.1. Overview of Schistosomiasis

Schistosomiasis, caused by parasitic flatworms of the genus Schistosoma, remains a persistent global health concern, affecting millions of people in tropical and subtropical regions [

1]. The disease is characterized by its unique life cycle, involving freshwater snails as intermediate hosts and humans as definitive hosts. While schistosomiasis is traditionally associated with its impact on the digestive and urinary systems, recent research has highlighted its lesser-known neurological manifestations [

2].

Schistosomiasis has a deep-rooted history, with evidence suggesting its presence in ancient Egyptian mummies [

3]. Over the centuries, it has been recognized as a significant public health challenge, particularly in regions with inadequate sanitation and limited access to clean water. The three main species of Schistosoma responsible for human infections are S. mansoni, S. japonicum, and S. haematobium [

4]. Each species exhibits a specific geographic distribution and affects a preferred organ system, with S. mansoni and S. japonicum primarily affecting the digestive system, while S. haematobium targets the urinary system [

5].

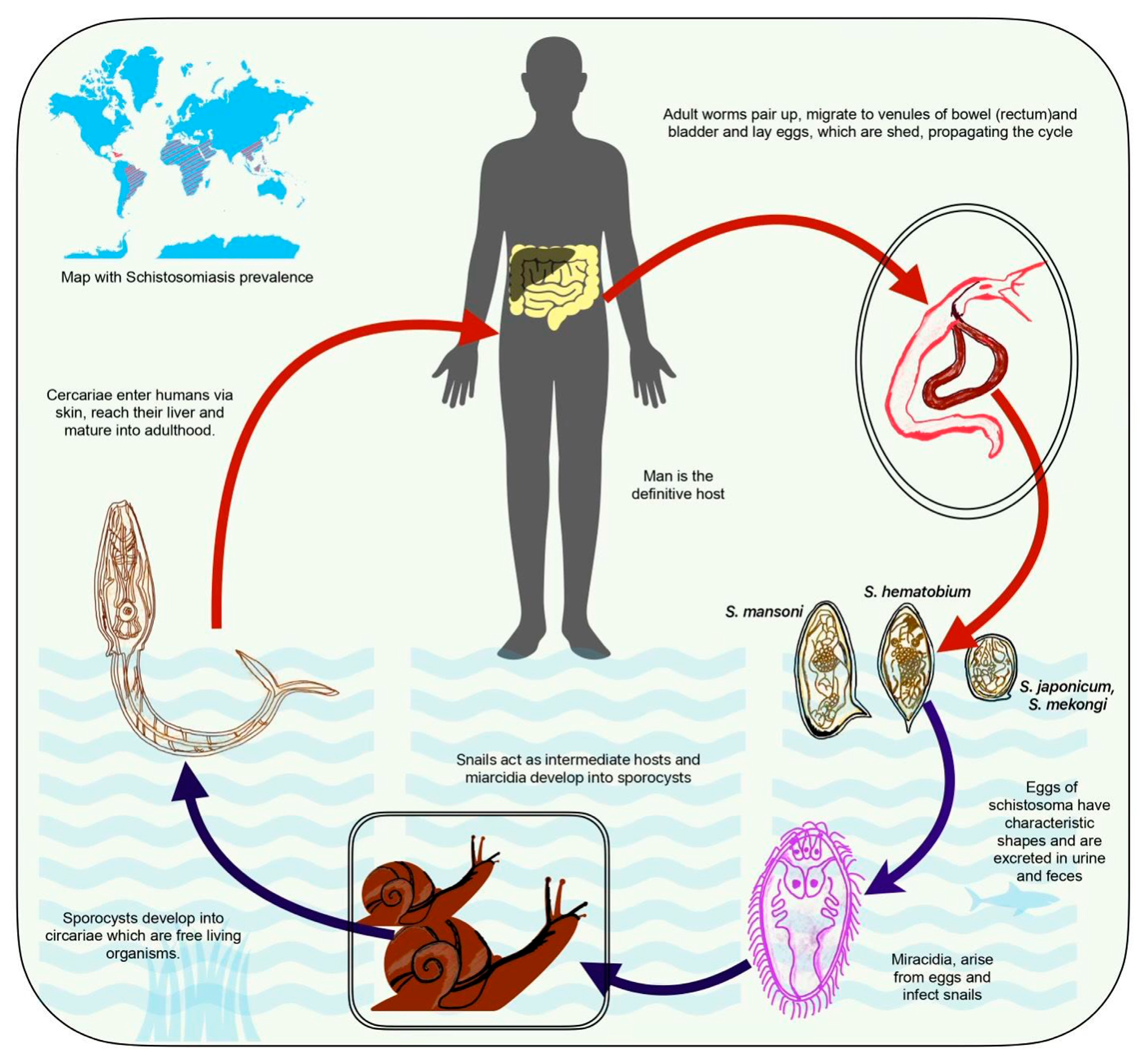

Understanding the schistosome life cycle is crucial for comprehending the disease's transmission (

Figure 1). Eggs laid by adult worms in human veins pass into freshwater through urine and feces, hatching into larvae that infect snails. The larvae develop further inside the snails, releasing infectious cercariae into the water. Cercariae penetrate and migrate to the bloodstream upon contact with human skin and reach the liver, where they mature into adult worms [

6].

S. mansoni and S. japonicum are species that predominantly infect the mesenteric veins of the intestines and liver [

7]. The presence of adult worms leads to the deposition of eggs in the intestinal wall, causing inflammation and tissue damage. Individuals infected with S. mansoni or S. japonicum may experience abdominal pain, diarrhea, and reticuloendothelial system. In severe cases, chronic infection can result in portal hypertension and liver fibrosis. S. haematobium primarily targets the veins around the bladder and pelvic organs [

8]. Eggs deposited in the urinary tract can lead to inflammation, ulceration, and scarring. Hematuria, dysuria, and urinary tract infections are common symptoms of urogenital schistosomiasis. Chronic infection may contribute to bladder dysfunction, hydronephrosis, and an increased risk of bladder cancer [

9].

The prevalence of schistosomiasis is closely linked to environmental factors, socioeconomic conditions, and access to clean water. Endemic in sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and parts of South America, the disease disproportionately affects communities with limited resources and inadequate sanitation infrastructure [

10]. Schistosomiasis has far-reaching consequences on individuals and communities. Beyond its direct effects on health, the disease contributes to poverty and hinders economic development. The chronic nature of infections can lead to long-term disabilities, impacting productivity and quality of life. Efforts to control and prevent schistosomiasis have primarily focused on mass drug administration of praziquantel, improved water and sanitation, and snail control programs [

11]. However, challenges such as drug resistance, limited access to treatment, and ongoing transmission persist, necessitating a multifaceted and sustained approach [

12].

While the traditional focus of schistosomiasis has centered on its impact on the digestive and urinary systems, emerging research has broadened our understanding to include neurological manifestations. Neuroschistosomiasis, characterized by its effects on the central nervous system, presents new challenges in diagnosis, treatment, and prevention [

13]. In conclusion, the historical significance of schistosomiasis, its causative agents, and its life cycle provide a foundation for understanding its traditional impact on the digestive and urinary systems [

14]. However, with the recognition of neurological manifestations, the landscape of schistosomiasis is evolving, demanding a comprehensive approach to address the multifaceted challenges posed by this neglected tropical disease.

1.2. Emergence of Neuroschistosomiasis

Neuroschistosomiasis is characterized by the infiltration of Schistosoma parasites into the central nervous system (CNS). This encompasses a spectrum of neurological disorders, from acute symptoms, including headaches and seizures, to chronic and subtle manifestations, such as cognitive impairment and motor dysfunction [

15]. The recognition of neuroschistosomiasis represents a critical step in acknowledging the comprehensive impact of the disease beyond its traditional boundaries. Understanding the epidemiology of neuroschistosomiasis is paramount for effective prevention and intervention. While the geographical distribution of Schistosoma species remains a crucial factor, neurological involvement is not uniform across all endemic regions [

16]. This variability underscores the need for targeted surveillance and research to elucidate the intricate interplay of environmental, host, and parasite factors contributing to neuroschistosomiasis.

2. Neuroschistosomiasis: An Overview

2.1. Definition and Classification

Neuroschistosomiasis represents a distinctive and evolving facet of the broader schistosomiasis spectrum, characterized by the involvement of the central nervous system (CNS) in Schistosoma infections. As our understanding of this parasitic disease advances, recognizing neuroschistosomiasis as a distinct entity has gained prominence, emphasizing its multifaceted clinical presentations [

17]. The term “neuroschistosomiasis” encompasses a spectrum of neurological disorders induced by the invasion of Schistosoma parasites into the CNS. This invasion initiates a cascade of immune responses, inflammatory reactions, and tissue damage within neural tissues, leading to diverse clinical manifestations. Understanding the different clinical forms of neuroschistosomiasis is paramount for accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and informed public health strategies [

18].

The acute form of neuroschistosomiasis is characterized by the sudden onset of neurological symptoms, often occurring during the initial stages of infection. Individuals experiencing acute neuroschistosomiasis may present with severe headaches, reflecting the inflammatory response to schistosome larvae in the CNS [

19]. Seizures are another hallmark of this phase, emphasizing the dynamic interaction between the parasites and the host's nervous system [

20]. Diagnosis during the acute stage can be challenging due to the nonspecific nature of symptoms, and misdiagnosis or delayed recognition may occur.

In the subacute form, patients may exhibit a combination of headaches, cognitive impairments, and subtle motor dysfunction. Subacute neuroschistosomiasis poses diagnostic challenges as symptoms can overlap with various neurological conditions, necessitating a thorough clinical evaluation and the utilization of specific diagnostic tools [

21]. Early recognition of the subacute form is crucial to prevent neurological deficits' progression and promptly initiate intervention.

Chronic neuroschistosomiasis represents the long-term consequences of sustained CNS involvement by Schistosoma parasites [

22]. This form is associated with persistent cognitive impairments affecting memory, attention, and other higher-order cognitive functions. Motor dysfunction, including weakness, tremors, and gait disturbances, may become more pronounced over time. Psychiatric manifestations, such as depression and anxiety, further contribute to the complexity of chronic neuroschistosomiasis [

23]. The chronic form demands comprehensive, multidisciplinary management, recognizing the enduring impact on patients’ daily lives and functioning.

A distinct clinical manifestation of neuroschistosomiasis involves the spinal cord, where Schistosoma parasites invade the spinal canal and compromise the integrity of the spinal cord [

24]. This form often presents symptoms such as back pain, lower limb weakness, and sensory disturbances. Another rare presentation is transverse myelitis associated with schistosomiasis [

25].

Cerebral neuroschistosomiasis primarily targets the brain parenchyma and the meninges, leading to a distinct set of neurological symptoms. Imaging studies, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), play a crucial role in identifying lesions within the brain. Cerebral neuroschistosomiasis highlights the diversity of neurological complications, emphasizing the need for specialized diagnostic approaches tailored to the affected regions of the CNS [

26].

Individuals experiencing cognitive neuroschistosomiasis may show memory loss, attention deficits, and difficulties in executive functioning [

27]. The subtle nature of cognitive deficits in this form may lead to underrecognition and delayed diagnosis. Evaluating global function becomes pivotal, requiring neuropsychological assessments and cognitive testing to gauge the extent of cognitive involvement accurately [

28].

Sometimes, patients may present with a combination of clinical forms, making the diagnostic landscape even more complex. Overlapping syndromes, where neurological manifestations coexist with traditional gastrointestinal or urogenital symptoms, challenge clinicians to consider the interconnectedness of various organ systems affected by schistosomiasis [

29]. A holistic approach must address the diverse clinical scenarios and tailor interventions accordingly.

2.2. Epidemiology

The incidence, prevalence, and geographical distribution of neuroschistosomiasis are complex and multifaceted aspects that are still evolving as research in this field progresses. Neuroschistosomiasis poses unique challenges in diagnosis, epidemiology, and understanding its geographic spread [

30].

Accurate incidence data for neuroschistosomiasis remain challenging to obtain due to the underreporting and misdiagnosis of cases, particularly in regions with limited healthcare infrastructure. The acute phase of neuroschistosomiasis is often characterized by severe symptoms such as headaches and seizures, leading individuals to seek medical attention [

31]. However, the subtle and chronic forms are underrecognized, contributing to underestimations of true incidence. Research efforts are continually working towards refining diagnostic criteria and surveillance methods to capture a more accurate picture of the incidence of neuroschistosomiasis [

32].

Determining the prevalence of neuroschistosomiasis is complex due to the varying clinical presentations and the challenges associated with an accurate diagnosis. In regions where schistosomiasis is endemic, prevalence studies traditionally focus on gastrointestinal and urogenital forms. However, as awareness of neuroschistosomiasis grows, researchers increasingly incorporate neurological assessments into broader prevalence studies. The chronic nature of some neurological manifestations further complicates prevalence estimates, as individuals may only seek medical attention once symptoms become more pronounced [

33].

The geographical distribution of neuroschistosomiasis is closely tied to the distribution of Schistosoma species [

34]. While Schistosoma mansoni and Schistosoma japonicum are traditionally associated with intestinal schistosomiasis, they have shown a propensity for causing neurologic manifestations. Schistosoma haematobium, primarily responsible for urogenital schistosomiasis, has also been linked to neurological complications [

35].

Regions with a high prevalence of schistosomiasis, such as sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and parts of South America, are likely to have a significant burden of neuroschistosomiasis [

36]. Environmental factors further influence the distribution, the presence of suitable snail hosts, and the behavior of the human population in interacting with infested water sources. Localized studies and case reports have emerged from endemic regions, providing insights into the occurrence of neuroschistosomiasis in specific areas. However, the lack of systematic surveillance and standardized diagnostic approaches hinders a comprehensive understanding of its global distribution [

37].

2.3. Risk Factors

The likelihood of neurological involvement in schistosomiasis is influenced by a combination of factors related to the parasite, the host, and the environment. Identifying these factors is crucial for understanding the mechanisms of neuroschistosomiasis and developing targeted interventions. S. mansoni and S. japonicum are primarily associated with intestinal schistosomiasis but have demonstrated a propensity for causing neurologic complications [

9]. The ability of these parasites to invade the central nervous system may contribute to the increased likelihood of neurological involvement.

Higher parasite loads, measured by the number of Schistosoma larvae (cercariae) entering the host, have been linked to an increased risk of neurological complications. A heavy burden of parasites may lead to more widespread tissue damage and immune responses in the central nervous system [

38]. The host’s immune response plays a crucial role in developing neuroschistosomiasis. Individuals with heightened immune reactivity may experience more pronounced inflammation in response to Schistosoma invasion, contributing to neurological symptoms [

39].

Schistosomes employ various immune evasion strategies, including the release of immunomodulatory molecules [

40]. These strategies may influence the host's immune response and potentially contribute to the ability of the parasites to invade neural tissues. Host genetic factors can affect the susceptibility to schistosomiasis and its complications. Genetic variations in the host's immune response or neural tissue susceptibility may contribute to the likelihood of neurological involvement [

41].

Children and adolescents may be more susceptible to neurological involvement due to the immaturity of their immune systems [

42]. Additionally, older individuals with age-related changes in immune function may be at increased risk. Co-infections with other pathogens, such as malaria or other parasitic diseases, can modulate the host's immune response and potentially raise the risk of neurological complications in schistosomiasis [

43].

Some studies suggest that gender may influence the likelihood of neurological involvement. For instance, gender-specific hormonal and immunological factors may contribute to variations in disease outcomes. Malnutrition, particularly deficiencies in certain micronutrients, can compromise the immune response and increase susceptibility to severe manifestations, including neurological complications [

44].

Activities involving prolonged contact with infested freshwater, such as swimming, bathing, or agricultural work, increase the risk of exposure to schistosome larvae and subsequent neurological complications [

45]. The presence of snail intermediate hosts, which facilitate the life cycle of schistosomes, contributes to the environmental risk of infection. Regions with abundant snails may see a higher prevalence of schistosomiasis and associated neurological involvement [

46].

3. Pathophysiology

3.1. Mechanisms of Neural Invasion

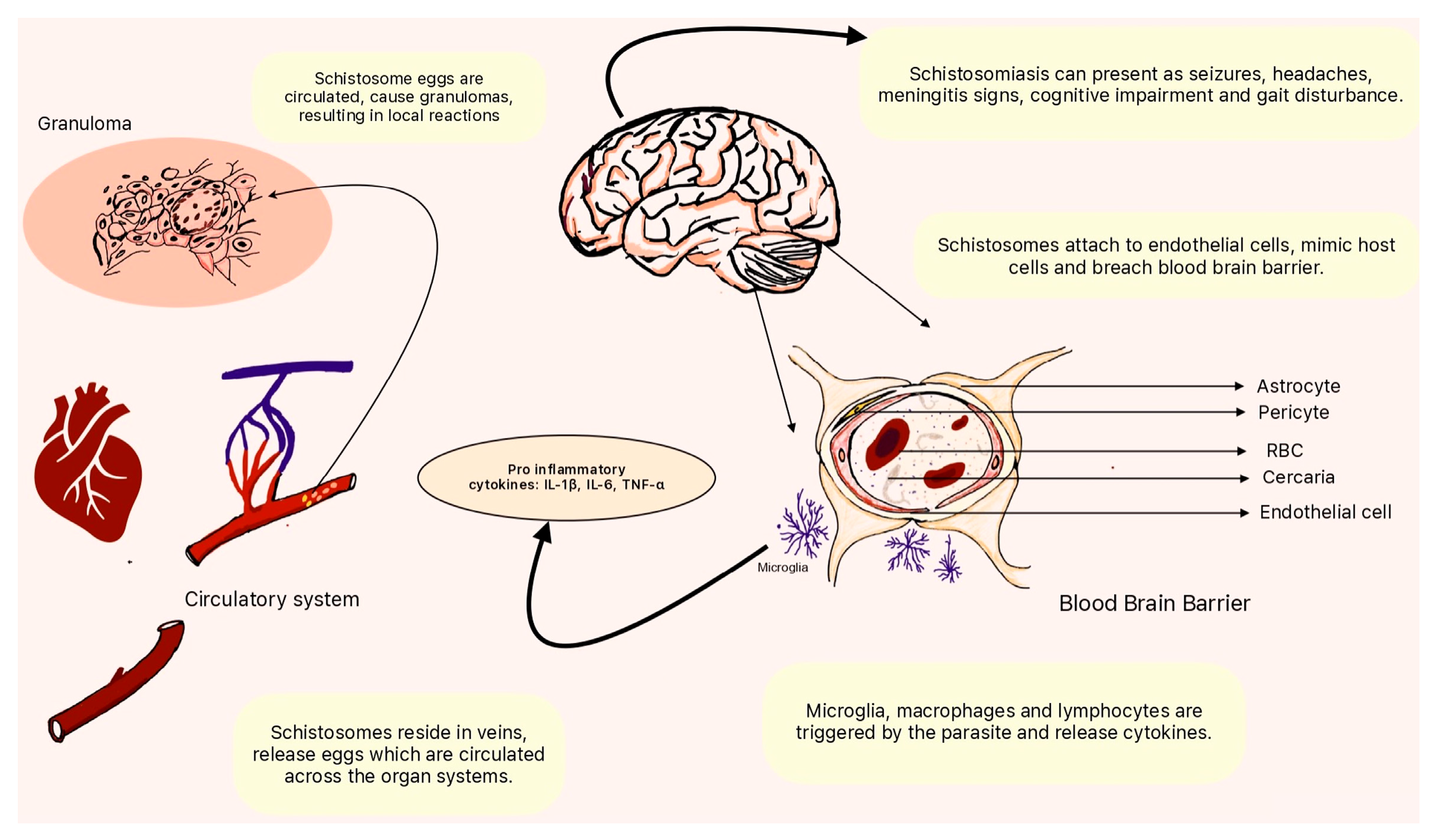

The invasion of the central nervous system (CNS) by schistosome parasites involves a complex interplay between the parasites, the host's immune system, and the blood-brain barrier (BBB) (Figure 2). The mechanisms through which schistosome parasites breach the BBB and invade the CNS are still the subject of ongoing research, but several hypotheses have been proposed [

47]. Schistosomes initially infect humans through the skin, where cercariae penetrate and enter the bloodstream. Once in the bloodstream, they travel throughout the body, eventually reaching the veins surrounding the intestines or bladder, depending on the Schistosoma species [

48]. During this systemic circulation, schistosomes may gain access to the CNS.

Figure 1.

Pathophysiology of neuroschistosomiasis. Schistosoma species use the circulatory system to seed the neurovascular unit. Through interactions with the host immune system and the release of cytokines by microglial cells, they weaken the blood-brain barrier and enter the brain, resulting in effects of varying acuity and severity. Schistosoma species can seed vessels and cause local inflammatory reactions by forming granulomas.

Figure 1.

Pathophysiology of neuroschistosomiasis. Schistosoma species use the circulatory system to seed the neurovascular unit. Through interactions with the host immune system and the release of cytokines by microglial cells, they weaken the blood-brain barrier and enter the brain, resulting in effects of varying acuity and severity. Schistosoma species can seed vessels and cause local inflammatory reactions by forming granulomas.

Adult schistosomes reside in the veins, releasing eggs that pass into the bloodstream [

49]. Some eggs may become trapped in the microvasculature, leading to granuloma formation and localized inflammation. The inflammatory response can compromise the integrity of the vascular endothelium, potentially allowing schistosome larvae or antigens to cross into the CNS [

50]. Also, the host's immune response to schistosome infections plays a pivotal role in the invasion of the CNS. The release of excretory-secretory products by schistosomes can induce an inflammatory response, activating immune cells. In turn, this immune response may contribute to the breakdown of the BBB, allowing the parasites to breach the barrier and invade neural tissues [

51].

Schistosomes are known to produce molecules that mimic host proteins [

52]. These mimicry mechanisms allow the parasites to evade the host's immune system and potentially exploit host pathways involved in BBB regulation. By mimicking host molecules, schistosomes could modulate the function of endothelial cells forming the BBB, facilitating their entry into the CNS. Moreover, schistosomes may exhibit chemotactic responses, following chemical gradients to navigate host tissues [

53]. Once in the vicinity of the CNS, the parasites may use adhesive molecules to interact with and adhere to endothelial cells of the blood vessels in the CNS. This adhesion is a crucial step in the invasion process.

Schistosomes employ various strategies to evade the host’s immune system. The ability of the parasites to modulate the host’s immune response may contribute to their successful invasion of the CNS. By subverting immune detection and response, schistosomes may exploit vulnerabilities in the BBB [

54]. It is important to note that the precise mechanisms of how schistosome parasites breach the BBB and invade the CNS remain an area of active research. The complexity of host-parasite interactions, the diversity of Schistosoma species, and the dynamic nature of the immune response contribute to the challenges in fully elucidating these mechanisms [

55].

3.2. Immune Response

The interplay between the host's immune response and schistosome-induced neuroinflammation is a dynamic and complex process that plays a central role in the pathogenesis of neuroschistosomiasis [

56]. As Schistosoma parasites invade the central nervous system (CNS), they interact with the host's immune system, triggering inflammatory responses that contribute to the development of neurological manifestations. Understanding this interplay is crucial for elucidating the mechanisms underlying neuroschistosomiasis and developing targeted therapeutic interventions [

57].

Schistosomes release various excretory-secretory products, including proteins and glycoproteins, into the host tissues. These products serve as immunomodulatory molecules that can influence the host's immune response [

58]. Some of these molecules may directly affect immune cells, altering their functions and contributing to the initiation of neuroinflammation. Also, schistosomes in the CNS activate various immune cells, including macrophages, microglia, and lymphocytes [

59]. These cells play pivotal roles in the immune response against the parasites but can also contribute to neuroinflammation. The activation of microglia is particularly relevant in schistosome-induced neuroinflammation.

The immune response to schistosomes involves the release of cytokines, signaling molecules that orchestrate and regulate immune reactions. In neuroschistosomiasis, an imbalance in cytokine production can lead to an exaggerated inflammatory response. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), contribute to neuroinflammation and tissue damage [

60]. Moreover, the chemotactic properties of schistosome antigens may attract immune cells to the site of infection in the CNS. Leukocyte infiltration contributes to the inflammatory milieu within neural tissues. This infiltration is a crucial component of neuroinflammation in response to schistosome invasion [

61].

The interaction between the host’s immune response and schistosomes can lead to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS). Oxidative stress, resulting from an imbalance between the production of these reactive species and antioxidant defenses, contributes to tissue damage and neuroinflammation in the CNS [

62]. Also, toll-like receptors (TLRs) are innate immune receptors that recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). Schistosome-derived molecules can activate TLRs, leading to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and amplification of the immune response [

63]. TLR activation in the CNS contributes to neuroinflammation in response to schistosome infection.

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) are a subset of T cells with immunosuppressive properties. The balance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses, including the induction of Tregs, influences the outcome of neuroschistosomiasis [

64]. Tregs may act to limit excessive inflammation and prevent immunopathology. As mentioned above, the inflammatory response initiated by the host’s immune system can contribute to the disruption of the BBB. The compromised integrity of the BBB allows immune cells, antibodies, and potentially even schistosome parasites or antigens to enter the CNS, exacerbating neuroinflammation.

4. Clinical Presentation

4.1. Acute Neuroschistosomiasis

During the acute phase of neuroschistosomiasis, individuals may experience symptoms that reflect the invasion of the central nervous system (CNS) by Schistosoma parasites [

65]. This phase typically occurs shortly after the initial infection and is characterized by an inflammatory response to the presence of schistosome larvae in neural tissues [

66].

Intense headaches are a hallmark symptom of acute neuroschistosomiasis [

67]. The inflammatory response triggered by schistosome larvae in the CNS can increase intracranial pressure, resulting in severe and persistent headaches. These headaches are often described as throbbing and may be exacerbated by position or physical activity changes. Seizures are another prominent manifestation of acute neuroschistosomiasis [

68]. Seizures may vary in intensity and presentation, ranging from focal seizures to generalized tonic-clonic seizures involving loss of consciousness.

Fever is a common systemic symptom during the acute phase of neuroschistosomiasis, which is related to the inflammatory response and the host’s immune reaction to schistosome larvae [

69]. Neurological deficits may manifest due to the inflammatory processes affecting the CNS. Individuals with acute neuroschistosomiasis may experience focal neurological deficits [

70]. The nature and severity of neurological deficits can vary among affected individuals.

Nausea and vomiting may occur in the systemic response to acute neuroschistosomiasis. Photophobia and a stiff neck can be indicative of meningeal irritation during acute neuroschistosomiasis [

71]. These symptoms suggest meningeal irritation and may contribute to the severity of headaches. In severe cases, acute neuroschistosomiasis may lead to altered consciousness. This can range from confusion and disorientation to more profound states of impairment. Altered consciousness may be associated with the severity of neurological involvement and the extent of inflammation in the CNS. It’s important to note that the symptoms of acute neuroschistosomiasis can overlap with those of other neurological conditions, making accurate diagnosis challenging [

72].

4.2. Chronic Neuroschistosomiasis

Chronic neuroschistosomiasis manifests with a spectrum of clinical presentations. The chronic phase may follow the acute phase of neuroschistosomiasis or, in some cases, present insidiously without an apparent acute episode. The clinical manifestations of chronic neuroschistosomiasis are diverse and can affect various aspects of neurological and cognitive functioning [

73].

Chronic neuroschistosomiasis can lead to cognitive deficits affecting memory, attention, and executive functions. Individuals may experience difficulties in learning, recalling information, and maintaining focus. The mental impairment can vary in severity, impacting daily functioning and quality of life. Also, motor dysfunction is a common manifestation of chronic neuroschistosomiasis. Individuals may exhibit weakness, tremors, and difficulties with coordination and balance. Gait disturbances are also observed, contributing to mobility challenges [

74].

In some cases, chronic neuroschistosomiasis may present with urinary and bowel incontinence. Individuals may experience numbness, tingling sensations, or heightened sensitivity in various body parts. In addition, neuropsychiatric symptoms, including depression and anxiety, are associated with chronic neuroschistosomiasis [

75]. The enduring impact of neurological deficits, coupled with the chronic nature of the disease, can contribute to emotional and psychological distress. While seizures are more commonly associated with the acute phase, some individuals with chronic neuroschistosomiasis may continue to experience recurrent seizures. Seizures can further contribute to cognitive impairment and functional limitations [

76].

Chronic neuroschistosomiasis may affect cranial nerves, leading to facial weakness, double vision, and difficulty swallowing. Psychomotor retardation refers to a slowing of physical and mental processes. Individuals with chronic neuroschistosomiasis may exhibit delayed movements, reduced reaction times, and a general slowing of cognitive and motor functions [

77].

Moreover, behavioral changes may be observed, including irritability, apathy, and social withdrawal. These changes can be secondary to the cognitive and emotional impact of chronic neuroschistosomiasis. In some cases, chronic neuroschistosomiasis may lead to the development of hydrocephalus, which can exacerbate neurological symptoms [

78].

5. Diagnosis

5.1. Neuroimaging

Neuroimaging is crucial in diagnosing neuroschistosomiasis by providing detailed images of the CNS structures. These imaging modalities contribute to identifying characteristic lesions, assessing disease severity, and differentiating from other neurological conditions. MRI and CT are valuable tools for detecting brain and spinal cord lesions associated with neuroschistosomiasis. These lesions may manifest as inflammation, granulomas, or focal abnormalities [

19].

Schistosoma-induced granulomas are a characteristic feature of neuroschistosomiasis [

79]. Neuroimaging can identify these granulomas, which are inflammatory nodules formed in response to the presence of schistosome eggs or antigens. The granulomas may appear as hyperintense or hypointense regions on MRI, depending on the stage and composition of the lesions. Also, the extent and severity of neuroschistosomiasis can be assessed through neuroimaging [

80]. The number, size, and location of lesions observed on MRI or CT scans can help gauge the severity of CNS involvement. Neuroimaging is essential for evaluating potential complications of neuroschistosomiasis, such as hydrocephalus or cerebral edema. These complications may require specific interventions, and neuroimaging provides crucial information for treatment planning.

5.2. Cerebrospinal Fluid Analysis

Examining cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for schistosome antigens and inflammatory markers is a valuable diagnostic approach in evaluating neuroschistosomiasis. This analysis provides crucial information about the presence of Schistosoma parasites in the CNS and the inflammatory response induced by their invasion [

81].

The presence of schistosome antigens in CSF can be detected using specific laboratory assays. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and other immunological methods are employed to identify schistosome-derived molecules, providing evidence of active infection within the CNS [

82]. Detection of schistosome antigens in CSF directly indicates the presence of parasites in the CNS. Pleocytosis and an increased concentration of proteins, particularly immunoglobulins, can indicate an ongoing inflammatory reaction. Serial analysis of CSF during treatment allows monitoring of the response to anti-schistosomal therapy [

83]. A decrease in schistosome antigens, a reduction in pleocytosis, and normalization of inflammatory markers in CSF may indicate a positive response to treatment.

6. Differential Diagnosis

Diagnosing neuroschistosomiasis presents significant challenges, primarily due to overlapping symptoms with other neurological diseases. The similarities in clinical presentations make distinguishing neuroschistosomiasis from various neurological conditions challenging, leading to delayed or misdiagnosed cases. The symptoms of neuroschistosomiasis, especially during the acute phase, are often nonspecific. Headaches, seizures, and fever, common in neuroschistosomiasis, are also seen in other neurological infections, migraines, and inflammatory conditions, making it challenging to pinpoint the specific cause based solely on clinical presentation.

Neuroschistosomiasis shares clinical features with other parasitic infections affecting the central nervous system, such as neurocysticercosis or cerebral malaria [

84]. Also, while neuroimaging is crucial in diagnosing neuroschistosomiasis, the lack of specific imaging findings poses challenges. Lesions and granulomas may resemble those seen in other neuroinflammatory or infectious diseases, making considering other diagnostic modalities and comprehensive clinical information necessary. Moreover, access to advanced diagnostic tools such as neuroimaging and specific laboratory tests may be limited in regions with endemic schistosomiasis. Lack of awareness about the disease, especially in non-endemic areas, leads to insufficient consideration of neuroschistosomiasis in the differential diagnosis.

In chronic cases, neuroschistosomiasis may present with subtle, insidious symptoms, making it challenging to associate them with a parasitic infection. Cognitive deficits and motor dysfunction may be attributed to other chronic neurological conditions, delaying the identification of neuroschistosomiasis. A comprehensive travel history is crucial in suspecting neuroschistosomiasis, as individuals may acquire the infection in endemic regions [

85]. However, reliance solely on travel history may be challenging if patients have lived in or visited multiple areas with different infectious risks. Individuals in endemic regions may experience concurrent infections, making it difficult to attribute symptoms solely to neuroschistosomiasis. The coexistence of other infectious diseases complicates the diagnostic process and necessitates a thorough investigation.

6.1. Distinguishing Neuroschistosomiasis from Other Neurological Conditions

The diagnosis of neuroschistosomiasis can be challenging due to the overlap of symptoms with various neurological conditions. Considering a broad range of potential differential diagnoses is crucial to ensure accurate identification and appropriate management.

The larvae of the pork tapeworm, Taenia solium, cause neurocysticercosis [

86]. It can present with seizures, headaches, and neurological deficits. Imaging studies, such as MRI, may reveal cystic lesions in the brain. In addition, toxoplasmosis, caused by the protozoan Toxoplasma gondii, can affect the CNS and present with neurological symptoms. Imaging studies may reveal ring-enhancing lesions [

87].

Bacterial, viral, or fungal meningitis can present symptoms similar to neuroschistosomiasis, including headaches, fever, and altered consciousness. CSF analysis is crucial for differentiating infectious causes. Also, cerebral malaria, caused by Plasmodium falciparum, can result in neurological symptoms such as seizures and altered mental status. It is prevalent in regions where schistosomiasis is also endemic [

88]. Moreover, TB meningitis can cause chronic meningitis with symptoms such as headache, fever, and altered mental status [

89]. CSF analysis is crucial for detecting Mycobacterium tuberculosis and assessing the inflammatory response.

MS is an autoimmune demyelinating disorder that can present with a variety of neurological symptoms, including cognitive deficits, motor dysfunction, and visual disturbances. Neuroimaging helps distinguish MS from neuroschistosomiasis [

90]. Vascular conditions leading to ischemic or hemorrhagic strokes may manifest with neurological symptoms similar to those seen in acute neuroschistosomiasis. Various types of epilepsy can present with seizures, which is a common symptom in neuroschistosomiasis. Differentiating the etiology of seizures requires a comprehensive clinical and diagnostic evaluation.

Conditions like autoimmune encephalitis can present with psychiatric symptoms, seizures, and altered consciousness [

91]. Serological and CSF studies help in identifying specific autoimmune antibodies.

Cryptococcal meningitis, caused by Cryptococcus neoformans, can result in chronic meningitis with symptoms overlapping with neuroschistosomiasis [

92]. CSF analysis is essential for diagnosis. Primary CNS lymphoma is a rare form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, which can present with neurological symptoms that require brain biopsy for definitive diagnosis. Also, certain metabolic disorders, such as urea cycle disorders or mitochondrial diseases, may present with neurological symptoms [

93]. Detailed metabolic and genetic testing may be necessary for diagnosis.

7. Treatment Strategies

7.1. Antiparasitic Drugs

Praziquantel is the most widely used drug for treating schistosomiasis, including neuroschistosomiasis [

94]. It is effective against adult schistosomes and is crucial in reducing the parasite burden, alleviating symptoms, and preventing further complications. Praziquantel disrupts the integrity of the schistosome's tegument, the outer surface of the parasite. This leads to increased permeability and calcium influx, ultimately causing paralysis and death of the adult worms.

Praziquantel is effective against adult schistosomes, including those that may have migrated to the CNS. Treatment with praziquantel aims to eliminate the parasites and halt the progression of the disease. Also, praziquantel kills adult schistosomes and reduces the production of eggs by the remaining worms, which is crucial in preventing further tissue damage, inflammation, and granuloma formation in the CNS.

The efficacy of praziquantel in neuroschistosomiasis depends on the dosage and treatment regimen. A standard oral dose of praziquantel is usually administered based on the patient’s weight. The treatment may involve a single dose or multiple doses over a short period, depending on the severity of the infection and the Schistosoma species involved. Early initiation of praziquantel treatment is associated with better outcomes in neuroschistosomiasis. Early intervention can prevent the progression of neurological complications and may improve the chances of neurological recovery.

One potential limitation is that praziquantel has limited blood-brain barrier (BBB) penetration. However, studies suggest that even with this limitation, praziquantel remains effective in treating neuroschistosomiasis, likely due to the disruption of parasites outside the CNS that indirectly affect the central nervous system. Also, the neuroschistosomiasis may lead to disruption of the BBB, facilitating the penetration of praziquantel in the CNS.

7.2. Symptomatic Management

In addition to antiparasitic treatment, supportive therapies play a crucial role in alleviating neurological symptoms associated with neuroschistosomiasis. These supportive measures aim to manage complications, improve overall neurological function, and enhance the quality of life for affected individuals.

For individuals experiencing seizures associated with neuroschistosomiasis, anticonvulsant medications may be prescribed. These medications help control and prevent seizures, contributing to improved neurological outcomes. Severe headaches are a common symptom of neuroschistosomiasis. Analgesic medications, such as acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), can be used to manage pain and alleviate headache symptoms.

Physical and occupational therapy are vital in addressing motor dysfunction and improving functional abilities. Rehabilitation programs enhance muscle strength, coordination, and overall mobility, improving daily functioning. Also, individuals with cognitive deficits resulting from neuroschistosomiasis may benefit from speech and cognitive rehabilitation. These therapies address memory impairment, attention deficits, and other cognitive challenges, promoting cognitive function and communication skills. Given the potential impact of neuroschistosomiasis on mental health, psychological and psychiatric support is essential. Counseling, psychotherapy, and psychiatric medications may be recommended to address anxiety, depression, or other psychological symptoms.

Individuals experiencing urinary or bowel dysfunction may benefit from symptomatic treatment. This may include medications to address incontinence or other bladder and bowel management strategies to improve overall quality of life. Neuropathic pain, which can be a consequence of neurological damage, may require specific medications such as gabapentin or pregabalin. Pain management strategies aim to reduce discomfort and improve the overall well-being of affected individuals. Chronic pain, which can be associated with neurological complications, may require comprehensive pain management strategies. This may involve a combination of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions tailored to the patient’s needs.

8. Prognosis and Long-Term Outcomes

8.1. Impact on Quality of Life

Neuroschistosomiasis can have profound and long-term consequences on patients’ daily lives, impacting various aspects of their physical, cognitive, and psychosocial well-being. The consequences may persist even after successful antiparasitic treatment, emphasizing the importance of comprehensive and ongoing care. Neuroschistosomiasis can lead to persistent neurological deficits, including motor dysfunction, sensory disturbances, and cognitive impairment. These deficits may affect daily activities such as walking, using fine motor skills, and performing routine tasks.

Chronic pain, often associated with nerve damage or granuloma formation, can significantly impact patients’ daily lives. Pain may affect mobility, sleep, and overall quality of life, requiring ongoing pain management strategies. Moreover, persistent neurological symptoms may result in functional limitations, affecting activities of daily living (ADLs) such as dressing, bathing, and eating. Rehabilitation strategies and assistive devices may be necessary to improve independence in daily tasks.

Cognitive deficits, including memory impairment and attention difficulties, can pose challenges in work, education, and social interactions. Patients may require support and accommodations to manage cognitive challenges effectively. The psychosocial impact of neuroschistosomiasis can be substantial. Stigmatization, social isolation, and changes in self-esteem may occur due to visible symptoms or functional limitations. Psychosocial support and counseling are essential components of comprehensive care.

Cognitive deficits and physical limitations may impact educational and occupational pursuits. Individuals may face challenges completing education, maintaining employment, or pursuing specific careers. Vocational rehabilitation and adaptive strategies may be beneficial. The impact on social relationships can be multifaceted. Changes in physical appearance, communication difficulties, or the need for additional support may influence interpersonal dynamics. Encouraging open communication and educating families and communities can mitigate social challenges.

The financial burden of managing chronic health conditions, including neuroschistosomiasis, can be substantial [

95]. Medical expenses, rehabilitation costs, and potential loss of income due to disability may contribute to financial strain for affected individuals and their families. Patients often develop adaptive strategies and coping mechanisms to navigate daily challenges. This may involve assistive devices, modified living environments, and the development of resilience to cope with the long-term consequences of neuroschistosomiasis.

8.2. Rehabilitation and Follow-Up Care

Managing persistent neurological deficits resulting from neuroschistosomiasis requires a multidisciplinary approach that addresses the physical, cognitive, and psychosocial aspects [

96]. Strategies aim to improve function, enhance quality of life, and promote independence. Implementing rehabilitation programs tailored to the individual's needs can significantly improve functional outcomes. Physical, occupational, and speech therapy may be recommended to address motor deficits, enhance fine motor skills, and improve communication abilities.

Using assistive devices and adaptive technologies can facilitate independence in daily activities. Mobility aids, orthotic devices, and adaptive personal care and communication tools can help individuals with persistent neurological deficits. Cognitive deficits associated with neuroschistosomiasis may benefit from cognitive rehabilitation [

97]. This includes structured exercises and interventions to improve memory, attention, and executive functions.

Chronic pain, a common consequence of neuroschistosomiasis, requires ongoing pain management strategies [

98]. This may involve medications, physical therapy, and complementary approaches such as acupuncture or relaxation techniques. Individualized pain management plans should be developed in collaboration with healthcare providers.

Psychosocial support is essential for individuals coping with persistent neurological deficits [

99]. Counseling and psychotherapy can address emotional challenges, provide coping strategies, and enhance resilience. Modifying the home environment to improve accessibility and safety is crucial. Occupational therapists can guide home modifications tailored to the specific needs of individuals with persistent neurological deficits. Encouraging regular physical activity, adapted to individual capabilities, is essential for maintaining mobility and preventing secondary complications. Physical exercise can also contribute to improved mood and overall well-being. Educating patients and their caregivers about the nature of persistent neurological deficits, available support services, and self-management strategies is crucial. Empowering individuals with knowledge enhances their ability to participate in their care actively.

9. Prevention and Public Health Implications

9.1. Integrating Neuroschistosomiasis into Control Programs

Integrating neuroschistosomiasis into broader control programs for schistosomiasis is essential for achieving comprehensive and sustainable disease management. This integration ensures that efforts to prevent, diagnose, and treat neuroschistosomiasis are aligned with existing strategies for controlling the overall burden of schistosomiasis.

Enhance surveillance systems to monitor the prevalence and distribution of neuroschistosomiasis. Surveillance tools should include clinical, laboratory, and neuroimaging data to identify and track cases accurately. Including neurological assessments as part of routine evaluations in schistosomiasis-endemic areas can help identify individuals with neurological symptoms early on, facilitating prompt diagnosis and intervention [

100]. Implement educational campaigns that raise awareness about the neurological complications of schistosomiasis. Community education programs can empower individuals to recognize symptoms, seek timely medical care, and understand the importance of preventive measures.

Integrate vector control strategies like snail control into existing schistosomiasis control programs. Reducing the intermediate host snail population helps minimize the transmission of schistosome larvae, including those that can cause neuroschistosomiasis. Include praziquantel, the primary drug for treating schistosomiasis, in mass drug administration campaigns. MDA should target intestinal and urinary schistosomiasis and consider the potential impact on neuroschistosomiasis by reducing the overall schistosome burden. Identify and prioritize high-risk areas for neuroschistosomiasis based on epidemiological data and implement targeted treatment interventions [

101]. Specific Schistosoma species, environmental factors, or other risk factors for neurological involvement may characterize high-risk areas.

Advocate for the inclusion of neuroschistosomiasis in national health policies and guidelines. This ensures that the condition receives appropriate attention and resources for its prevention, diagnosis, and treatment within the broader healthcare system. Strengthen healthcare infrastructure to facilitate the diagnosis and management of neuroschistosomiasis. This includes training healthcare professionals in endemic regions to recognize neurological symptoms and providing access to neuroimaging facilities. Foster interdisciplinary collaboration among healthcare professionals, researchers, policymakers, and community stakeholders. A collaborative approach ensures that expertise from various fields contributes to the design and implementation of integrated control programs. Conduct regular evaluations of schistosomiasis control programs to assess their effectiveness in addressing neuroschistosomiasis. Evaluate the impact of interventions on reducing the overall burden of the disease, including neurological complications [

102].

9.2. Challenges and Future Directions

Preventing neuroschistosomiasis presents various challenges, ranging from limited resources and awareness to the complex lifecycle of the schistosome parasites. Addressing these obstacles requires a multifaceted approach encompassing preventive measures, community engagement, and strengthening of the health system.

Lack of access to clean water and proper sanitation facilities in endemic regions contributes to increased exposure to contaminated water sources, favoring schistosome transmission [

103]. Many affected communities may lack awareness about the transmission and consequences of neuroschistosomiasis. This leads to delayed healthcare-seeking behavior and hinders the adoption of preventive measures. Also, snail control, a crucial aspect of schistosomiasis prevention, is challenging due to the diverse habitats of intermediate host snails. Implementing effective vector control strategies requires sustained efforts and resources. Moreover, the complex life cycle of schistosomes involving specific snail hosts and environmental factors makes it challenging to control transmission [

104]. Environmental modifications, such as irrigation projects, can create favorable conditions for snail proliferation.

Mass drug administration with praziquantel is a cornerstone of schistosomiasis control [

105]. However, achieving high coverage rates in endemic areas can be hindered by logistical challenges, including community participation, drug distribution, and monitoring. The complex life cycle of schistosomes involving specific snail hosts and environmental factors makes it challenging to control transmission. Environmental modifications, such as irrigation projects, can create favorable conditions for snail proliferation. Diagnostic methods for identifying neuroschistosomiasis may be limited, especially in resource-limited settings [

106]. The lack of sensitive and specific diagnostic tools can result in underdiagnosis and delayed treatment.

A potential strategy for improving the neuroschistosomiasis burden is to invest in water and sanitation infrastructure, which is fundamental to reducing schistosome transmission [

107]. Access to clean water and improved sanitation facilities help minimize contact with contaminated water sources. Also, implement community-based health education programs to increase awareness about schistosomiasis and its neurological complications [

108]. Education should emphasize preventive behaviors, early symptom recognition, and seeking timely medical care.

Another possible strategy for snail control is through environmentally friendly methods [

109]. Research and implement innovative approaches for snail population reduction, targeting specific ecological niches. Integrate neuroschistosomiasis prevention into existing mass drug administration campaigns for schistosomiasis. Ensure high coverage rates, particularly in areas where both intestinal and urinary schistosomiasis coexist.

10. Conclusion

Neuroschistosomiasis represents a significant yet often overlooked public health challenge in endemic regions. Recognizing and addressing neuroschistosomiasis is paramount due to its devastating neurological consequences and the potential for long-term disability. While the primary focus of schistosomiasis control has traditionally been on intestinal and urinary manifestations, neglecting neuroschistosomiasis can lead to missed prevention and timely intervention opportunities. Therefore, raising awareness among healthcare professionals, policymakers, and affected communities about the neurological complications of schistosomiasis is critical for early detection and intervention. Further research is needed to address gaps in our understanding of neuroschistosomiasis, including its epidemiology, pathophysiology, and optimal management strategies. Improved diagnostic tools, such as sensitive and specific tests for detecting neurological involvement, are essential for accurate diagnosis and timely treatment.

Supplementary Materials

None.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P.R., V.V.B., and A.L.F.C.; methodology, A.L.F.C.; software, A.L.F.C.; validation, A.L.F.C., J.P.R. and V.V.B.; formal analysis, A.L.F.C.; investigation, A.L.F.C.; resources, A.L.F.C.; data curation, J.P.R.; writing—original draft preparation, J.P.R.; writing—review and editing, J.P.R.; visualization, V.V.B.; supervision, V.V.B.; project administration, V.V.B.; funding acquisition, J.P.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data created.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lee, J. Planarians to Schistosomes: An Overview of Flatworm Cell-Types and Regulators. Journal of Helminthology 2023, 97, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keshri, A.K.; Sharma, S.; Rawat, S.S.; Chaudhry, A.; Mehra, P.; Arora, N.; Prasad, A. An Overview on Helminthic Infections of Central Nervous System in Humans. A Review on Diverse Neurological Disorders 2024, 43–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenwick, A.; Norris, W.; McCall, B. A Tale of a Man, a Worm and a Snail: The Schistosomiasis Control Initiative; CABI, 2021; ISBN 1-78639-255-0.

- Cando, L.F.T.; Perias, G.A.S.; Tantengco, O.A.G.; Dispo, M.D.; Ceriales, J.A.; Girasol, M.J.G.; Leonardo, L.R.; Tabios, I.K.B. The Global Prevalence of Schistosoma Mansoni, S. Japonicum, and S. Haematobium in Pregnant Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 2022, 7, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padi, N. Biophysicochemical Properties of the 28-kDa Schistosoma Haematobium and Pseudo-26-kDa Schistosoma Haematobium/Bovis Glutathione Transferase. 2022.

- Milgroom, M.G. Helminths. In Biology of Infectious Disease: From Molecules to Ecosystems; Springer, 2023; pp. 89–108.

- ElShewy, K. Liver Parasites. In Medical Parasitology: A Body System Approach; Springer, 2024; pp. 99–121.

- Rombaoa, C.; Hu, K.-Q. The Treatment of Bacterial and Parasitic Diseases of the Liver. Liver Immunology: Principles and Practice 2020, 211–225. [CrossRef]

- Llanwarne, F.; Helmby, H. Granuloma Formation and Tissue Pathology in Schistosoma Japonicum versus Schistosoma Mansoni Infections. Parasite immunology 2021, 43, e12778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omondi, I.; Odiere, M.R.; Rawago, F.; Mwinzi, P.N.; Campbell, C.; Musuva, R. Socioeconomic Determinants of Schistosoma Mansoni Infection Using Multiple Correspondence Analysis among Rural Western Kenyan Communities: Evidence from a Household-Based Study. Plos one 2021, 16, e0253041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, C.M.; Timson, D.J. The Mechanism of Action of Praziquantel: Can New Drugs Exploit Similar Mechanisms? Current Medicinal Chemistry 2020, 27, 676–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutapi, F.; Garba, A.; Woolhouse, M.; Kazyoba, P. Paediatric Schistosomiasis: Last Mile Preparations for Deploying Paediatric Praziquantel. Trends in Parasitology 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, I.; Abdallah, A.; Khalid, M.; Musa, A.; Elzouki, A.N. Diagnosis of Neuroschistosomiasis: How to Overcome This Challenge. Libyan Journal of Medical Sciences 2020, 4, 35–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, A.L.C.; Barbosa, C.S.; Agt, T.F.A.; Mota, A.B.; Franco, C.M.R.; Lopes, E.P.; Loyo, R.; Gomes, E.C.S. Spinal Neuroschistosomiasis Caused by Schistoma Mansoni: Cases Reported in Two Brothers. BMC Infectious Diseases 2020, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Anjos Gomes, H.; de Oliveira Macedo, A.G.; Moraes, E.N.O.; Menezes, M.R.; Milhor, M.V.L.; de Oliveira Santos, J.E.; da Silva Barbosa, C.; da Silva Guerreiro, M.L. Immunopathological Changes in Spinal Neuroschistosomiasis. 17o Simpósio Internacional sobre Esquistossomose 2024.

- Yankey, K.P.; Awoonor-William, R.; Owusu, D.N.; Sackeyfio, A.; Nyarko, V.; Gross-Fenandez, L.; Addai, F.; Wulff, I.; Boachie-Adjei, O. Neuroschistosomiasis: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Journal of West African College of Surgeons 2024, 14, 450–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Neuroschistosomiasis and the Central Nervous System. Highlights in Science, Engineering and Technology 2022, 19, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, P.; Wu, G. Spectrum of Imaging Findings in Oriental Cerebral Schistosomiasis and Their Categorization by MRI. Nepalese Journal of Radiology 2020, 10, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelwan, M. Clinical Manifestation of Schistosomiasis. Human schistosomiasis, a comprehensive overview 2020.

- Ferrari, T.C.A.; Oliveira, A.E.M.; Logato, M.J.S.; Ganzella, C.G.; Melo, R.F.Q.; Rocha, A.P.C.; Barbosa, F.A.; Cunha, P.F.S.; Silva, R.A.P.; Faria, L.C. Are Seizures Associated with Neuroschistosomiasis Mansoni? An Exploratory Survey in an Endemic Area of Brazil. Transactions of The Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2022, 116, 704–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbonell, C.; Rodríguez-Alonso, B.; López-Bernús, A.; Almeida, H.; Galindo-Pérez, I.; Velasco-Tirado, V.; Marcos, M.; Pardo-Lledías, J.; Belhassen-García, M. Clinical Spectrum of Schistosomiasis: An Update. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2021, 10, 5521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobbi, F.; Tamarozzi, F.; Buonfrate, D.; van Lieshout, L.; Bisoffi, Z.; Bottieau, E. New Insights on Acute and Chronic Schistosomiasis: Do We Need a Redefinition? Trends in parasitology 2020, 36, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittella, J.E. Neuroschistosomiasis. Brain Pathology 1997, 7, 649–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, A.G.; McManus, D.P.; Farrar, J.; Hunstman, R.J.; Gray, D.J.; Li, Y.-S. Neuroschistosomiasis. Journal of neurology 2012, 259, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carod-Artal, F.J. Neuroschistosomiasis. Expert review of anti-infective therapy 2010, 8, 1307–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carod Artal, F.J. Cerebral and Spinal Schistosomiasis. Current neurology and neuroscience reports 2012, 12, 666–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmshurst, J.M. Threats to the Child’s Brain in Resource-Poor Countries. Journal of the International Child Neurology Association 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparotto, J.; Senger, M.R.; de Sá Moreira, E.T.; Brum, P.O.; Kessler, F.G.C.; Peixoto, D.O.; Panzenhagen, A.C.; Ong, L.K.; Soares, M.C.; Reis, P.A. Neurological Impairment Caused by Schistosoma Mansoni Systemic Infection Exhibits Early Features of Idiopathic Neurodegenerative Disease. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2021, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, C.H. Schistosomiasis: Challenges and Opportunities. The causes and impacts of neglected tropical and zoonotic diseases: Opportunities for integrated intervention strategies 2011.

- Silvestri, V. Vascular Damage in Neglected Tropical Diseases: A Surgical Perspective; Springer Nature, 2024; ISBN 3-031-53353-4.

- Ferrari, T.C.A.; Moreira, P.R.R. Neuroschistosomiasis: Clinical Symptoms and Pathogenesis. The Lancet Neurology 2011, 10, 853–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenwick, A.; Rollinson, D.; Southgate, V. Implementation of Human Schistosomiasis Control: Challenges and Prospects. Adv Parasitol 2006, 61, 567–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vale, T.C.; de Sousa-Pereira, S.R.; Ribas, J.G.; Lambertucci, J.R. Neuroschistosomiasis Mansoni: Literature Review and Guidelines. The Neurologist 2012, 18, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bill, P. Schistosomiasis and the Nervous System. Practical Neurology 2003, 3, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Zhu, H.; Geng, J.; Hu, X.; Li, Y.; Shi, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, D.; Wang, H.; Xie, L.; et al. Recognition of Parasitic Helminth Eggs via a Deep Learning-Based Platform. Front Microbiol 2024, 15, 1485001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelwan, M. Global Epidemiology of Schistosomiasis. Available at SSRN 3722378 2020.

- Aula, O.P.; McManus, D.P.; Jones, M.K.; Gordon, C.A. Schistosomiasis with a Focus on Africa. Trop Med Infect Dis 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thieltges, D.W.; Reise, K.; Prinz, K.; Jensen, K.T. Invaders Interfere with Native Parasite–Host Interactions. Biological Invasions 2009, 11, 1421–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannister, B.; Gillespie, S.H.; Jones, J. Infection: Microbiology and Management; John Wiley & Sons, 2009; ISBN 1-4443-2393-8.

- Li, J.; Liu, H.; Jiang, J.; She, X.; Niu, Y.; Ming, Y. The Potential Role of Schistosome-Associated Factors as Therapeutic Modulators of the Immune System. Infect Immun 2020, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Montor, J.; Hall, C.A. The Host-Parasite Neuroimmunoendocrine Network in Schistosomiasis: Consequences to the Host and the Parasite. Parasite Immunol 2007, 29, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coyle, C.M. Schistosomiasis of the Nervous System. Handb Clin Neurol 2013, 114, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Román, G.C. The Neurology of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2011, 17, 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papier, K.; Williams, G.M.; Luceres-Catubig, R.; Ahmed, F.; Olveda, R.M.; McManus, D.P.; Chy, D.; Chau, T.N.P.; Gray, D.J.; Ross, A.G.P. Childhood Malnutrition and Parasitic Helminth Interactions. Clin Infect Dis 2014, 59, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bispo, M.T.; Calado, M.; Maurício, I.L.; Ferreira, P.M.; Belo, S. Zoonotic Threats: The (Re)Emergence of Cercarial Dermatitis, Its Dynamics, and Impact in Europe. Pathogens 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabone, M.; Wiethase, J.H.; Allan, F.; Gouvras, A.N.; Pennance, T.; Hamidou, A.A.; Webster, B.L.; Labbo, R.; Emery, A.M.; Garba, A.D.; et al. Freshwater Snails of Biomedical Importance in the Niger River Valley: Evidence of Temporal and Spatial Patterns in Abundance, Distribution and Infection with Schistosoma Spp. Parasit Vectors 2019, 12, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adalid-Peralta, L.; Sáenz, B.; Fragoso, G.; Cárdenas, G. Understanding Host-Parasite Relationship: The Immune Central Nervous System Microenvironment and Its Effect on Brain Infections. Parasitology 2018, 145, 988–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LoVerde, P.T. Check for Schistosomiasis Philip T. LoVerde. Digenetic Trematodes 2024, 1454, 75. [Google Scholar]

- Nation, C.S.; Da’dara, A.A.; Marchant, J.K.; Skelly, P.J. Schistosome Migration in the Definitive Host. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2020, 14, e0007951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costain, A.H.; MacDonald, A.S.; Smits, H.H. Schistosome Egg Migration: Mechanisms, Pathogenesis and Host Immune Responses. Frontiers in immunology 2018, 9, 3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshino, T.P.; Lodes, M.J.; Rege, A.A.; Chappell, C.L. Proteinase Activity in Miracidia, Transformation Excretory-Secretory Products, and Primary Sporocysts of Schistosoma Mansoni. J Parasitol 1993, 79, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrook, J.R.; Hanington, P.C. Immune Evasion Strategies of Schistosomes. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 624178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabe, K.; Haas, W. Navigation within Host Tissues: Schistosoma Mansoni and Trichobilharzia Ocellata Schistosomula Respond to Chemical Gradients. Int J Parasitol 2004, 34, 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, S.J.; Hewitson, J.P.; Jenkins, G.R.; Mountford, A.P. Modulation of the Host’s Immune Response by Schistosome Larvae. Parasite Immunol 2005, 27, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Z.-G.; Brindley, P.J.; Wang, S.-Y.; Chen, Z. Schistosoma Genomics: New Perspectives on Schistosome Biology and Host-Parasite Interaction. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 2009, 10, 211–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento-Carvalho, C.M.; Moreno-Carvalho, O.A. Neuroschistosomiasis Due to Schistosoma Mansoni: A Review of Pathogenesis, Clinical Syndromes and Diagnostic Approaches. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 2005, 47, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadeer, A.; Ullah, H.; Sohail, M.; Safi, S.Z.; Rahim, A.; Saleh, T.A.; Arbab, S.; Slama, P.; Horky, P. Potential Application of Nanotechnology in the Treatment, Diagnosis, and Prevention of Schistosomiasis. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2022, 10, 1013354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acharya, S.; Da’dara, A.A.; Skelly, P.J. Schistosome Immunomodulators. PLoS Pathog 2021, 17, e1010064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majer, M. The Immune Response of Mice against Avian Schistosomes: From Local to Systemic Perspective. 2023.

- Masamba, P.; Kappo, A.P. Immunological and Biochemical Interplay between Cytokines, Oxidative Stress and Schistosomiasis. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macháček, T. The Immune Response of Naïve Mice Infected with the Neuropathogenic Schistosome Trichobilharzia Regenti. 2020.

- Moné, Y.; Ribou, A.-C.; Cosseau, C.; Duval, D.; Théron, A.; Mitta, G.; Gourbal, B. An Example of Molecular Co-Evolution: Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and ROS Scavenger Levels in Schistosoma Mansoni/Biomphalaria Glabrata Interactions. International journal for parasitology 2011, 41, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, Y.; McManus, D.P.; Hou, N.; Cai, P. Schistosome Infection and Schistosome-Derived Products as Modulators for the Prevention and Alleviation of Immunological Disorders. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 619776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Zhu, F.; Zheng, W.; Jacques, M.L.; Huang, J.; Guan, F.; Lei, J. Protective Effect of Schistosoma Japonicum Eggs on TNBS-Induced Colitis Is Associated with Regulating Treg/Th17 Balance and Reprogramming Glycolipid Metabolism in Mice. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12, 1028899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jauréguiberry, S.; Paris, L.; Caumes, E. Acute Schistosomiasis, a Diagnostic and Therapeutic Challenge. Clin Microbiol Infect 2010, 16, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macháček, T.; Panská, L.; Dvořáková, H.; Horák, P. Nitric Oxide and Cytokine Production by Glial Cells Exposed in Vitro to Neuropathogenic Schistosome Trichobilharzia Regenti. Parasit Vectors 2016, 9, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finsterer, J.; Auer, H. Parasitoses of the Human Central Nervous System. J Helminthol 2013, 87, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Hussein, H.N.; Alomari, D.; Al Nakhalah, S.; Alfitori, G. Neuroschistosomiasis in Young Filipino Patient Presenting with Seizure. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med 2024, 11, 004854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, T.C. Spinal Cord Schistosomiasis. A Report of 2 Cases and Review Emphasizing Clinical Aspects. Medicine (Baltimore) 1999, 78, 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, A.L.; Raibagkar, P.; Pritt, B.S.; Mateen, F.J. Neurologic Manifestations of the Neglected Tropical Diseases. J Neurol Sci 2015, 349, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Román, G.C. Tropical Myelopathies. Handb Clin Neurol 2014, 121, 1521–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caumes, E.; Vidailhet, M. Acute Neuroschistosomiasis: A Cerebral Vasculitis to Treat with Corticosteroids Not Praziquantel. J Travel Med 2010, 17, 359, author reply 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, C.H.; Dangerfield-Cha, M. The Unacknowledged Impact of Chronic Schistosomiasis. Chronic Illn 2008, 4, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, V.K.; Wang, L.; Min, X.; Rizal, R.; Feng, Z.; Ke, Z.; Deng, M.; Li, L.; Li, H. Human Schistosomiasis: A Diagnostic Imaging Focused Review of a Neglected Disease. Radiology of Infectious Diseases 2015, 2, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olveda, D.U.; Olveda, R.M.; McManus, D.P.; Cai, P.; Chau, T.N.P.; Lam, A.K.; Li, Y.; Harn, D.A.; Vinluan, M.L.; Ross, A.G.P. The Chronic Enteropathogenic Disease Schistosomiasis. Int J Infect Dis 2014, 28, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpio, A.; Romo, M.L.; Parkhouse, R.; Short, B.; Dua, T. Parasitic Diseases of the Central Nervous System: Lessons for Clinicians and Policy Makers. Expert review of neurotherapeutics 2016, 16, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastoli, P.A.; Leite, A.L.; da Costa, M.D.S.; Nicácio, J.M.; Pinho, R.S.; Ferrarini, M.A.G.; Cavalheiro, S. Medullary Neuroschistosomiasis in Adolescence: Case Report and Literature Review. Childs Nerv Syst 2021, 37, 2735–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, D.J.; Ross, A.G.; Li, Y.-S.; McManus, D.P. Diagnosis and Management of Schistosomiasis. BMJ 2011, 342, d2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Brutto, O.H. Infections and Stroke. Handb Clin Neurol 2009, 93, 851–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruscky, I.S.; Bruscky, D.M.V.; de Melo, F.L.; Medeiros, Z.M.; Correia, C. da C. Cerebral Mansoni Schistosomiasis: A Systematic Review of 33 Cases Published from 1989 to 2019. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2021, 115, 1410–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadekar, S.; Solanki, P.; Tiwari, A.; Rai, H.; Pandey, A.; Khan, M.N.A.; Commander, S.L.; Gupta, H. Understanding Fever: A Practical Approach for Clinicians; Professional Publication Services, 2024; ISBN 93-341-4391-6.

- Hamilton, J.V.; Klinkert, M.; Doenhoff, M.J. Diagnosis of Schistosomiasis: Antibody Detection, with Notes on Parasitological and Antigen Detection Methods. Parasitology 1998, 117 Suppl, S41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, T.C.A.; Moreira, P.R.R.; Cunha, A.S. Clinical Characterization of Neuroschistosomiasis Due to Schistosoma Mansoni and Its Treatment. Acta Trop 2008, 108, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tunali, V.; Korkmaz, M. Emerging and Re-Emerging Parasitic Infections of the Central Nervous System (CNS) in Europe. Infect Dis Rep 2023, 15, 679–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baert, A. Imaging of Parasitic Diseases; Springer Science & Business Media, 2007; ISBN 3-540-49354-9.

- Smith, J.L. Taenia Solium Neurocysticercosis (1). J Food Prot 1994, 57, 831–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attias, M.; Teixeira, D.E.; Benchimol, M.; Vommaro, R.C.; Crepaldi, P.H.; De Souza, W. The Life-Cycle of Toxoplasma Gondii Reviewed Using Animations. Parasit Vectors 2020, 13, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Wei, W.; Cheng, W.; Zhu, H.; Wang, W.; Dong, H.; Li, J. Cerebral Malaria Induced by Plasmodium Falciparum: Clinical Features, Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12, 939532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, A.; Dayal, S.; Gadhe, R.; Mawley, A.; Shin, K.; Tellez, D.; Phan, P.; Venketaraman, V. Analysis of Tuberculosis Meningitis Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment. J Clin Med 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos Miranda, T.A.; Tsuchiya, K.; Lucato, L.T. Imaging of Central Nervous System Parasitic Infections. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 2023, 33, 125–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, H.; Griffith, S.; Warren, N.; Swayne, A.; Blum, S.; Butzkueven, H.; O’Brien, T.J.; Velakoulis, D.; Kulkarni, J.; Monif, M. Psychiatric Manifestations of Autoimmune Encephalitis. Autoimmun Rev 2022, 21, 103145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Babikir, H.; Singh, P. Neuroinfections and Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTD). Clinical Child Neurology 2020, 529–628.

- Sen, K.; Whitehead, M.; Castillo Pinto, C.; Caldovic, L.; Gropman, A. Fifteen Years of Urea Cycle Disorders Brain Research: Looking Back, Looking Forward. Anal Biochem 2022, 636, 114343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Condeng, Y.H.; Katu, S.; Aman, A.M.; Rasyid, H.; Bakri, S.; Iskandar, H. Praziquantel as the Preferred Treatment for Schistosomiasis. Int Marit Health 2024, 75, 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Vitolas, C.A.; Trienekens, S.C.M.; Zaadnoordijk, W.; Gouvras, A.N. Behaviour Change Interventions for the Control and Elimination of Schistosomiasis: A Systematic Review of Evidence from Low- and Middle-Income Countries. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2023, 17, e0011315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opoku, T. The Brain Impact of Schistosomiasis and 13 Potential Treatments. 2023.

- Goyal, G.; Kaur, U.; Sharma, M.; Sehgal, R. Neuropsychiatric Aspects of Parasitic Infections-A Review. Neurol India 2023, 71, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, J.; Bonifácio, G.V.; Vieira, R.; Militão, A.; Guerreiro, R. Long-Lasting Latent Neuroschistosomiasis in a Nonendemic Country: A Case Report. Cureus 2024, 16, e63007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koschorke, M.; Al-Haboubi, Y.H.; Tseng, P.-C.; Semrau, M.; Eaton, J. Mental Health, Stigma, and Neglected Tropical Diseases: A Review and Systematic Mapping of the Evidence. Frontiers in Tropical Diseases 2022, 3, 808955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belizario Jr, V.Y.; de Cadiz, A.E.; Navarro, R.C.; Flores, M.J.C.; Molina, V.B.; Dalisay, S.N.M.; Medina, J.R.C.; Lumangaya, C.R. The Status of Schistosomiasis Japonica Control in the Philippines: The Need for an Integrated Approach to Address a Multidimensional Problem. 2022.

- Ofori, E.K.; Forson, A.O. Schistosomiasis: Recent Clinical Reports and Management. Rising Contagious Diseases: Basics, Management, and Treatments 2024, 368–377.

- Berkowitz, A.L. Approach to Neurologic Infections. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2021, 27, 818–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulkadir, A.; Darma, Y.A.; Dahiru, S. Analysis On The Prevalence And Risk Factors Of Urinary Schistosomiasis Among Secondary School Students In Katsina Local Government Area, Katsina State. 2024.

- Rizwan, H.M.; Naz, S.; Raza, M.; Iqbal, A.; Iftakhar, T.; Abbas, H.; Akhtar, T. Biology and Ecology of Parasites. In Parasitism and Parasitic Control in Animals: Strategies for the Developing World; CABI GB, 2023; pp. 1–20.

- Probst, A.C. Investigations on New and Forgotten Antischistosomal Drugs and Praziquantel Pharmacokinetics in Opisthorchiasis Patients. 2023.

- Hoekstra, P.T.; van Dam, G.J.; van Lieshout, L. Context-Specific Procedures for the Diagnosis of Human Schistosomiasis–a Mini Review. Frontiers in Tropical Diseases 2021, 2, 722438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegand, R.E. Improving the Monitoring and Evaluation of Schistosomiasis by Determining Appropriate Targets and Utilizing New Technologies. 2022.

- Nyangi, C.J. Development and Rapid Assessment of Community-Based Health Education Package for the Control of Taenia Solium Taeniasis/Cysticercosis in Tanzania. Tanzania Journal of Health Research 2024, 25, 1066–1084. [Google Scholar]

- Barua, A.; Williams, C.D.; Ross, J.L. A Literature Review of Biological and Bio-Rational Control Strategies for Slugs: Current Research and Future Prospects. Insects 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).