Introduction

Schistosomiasis, also known as Bilharzia, is an infectious disease caused by trematode flukes of the genus Schistosoma [

1]. Recognized as a neglected tropical disease (NTD), it is estimated that approximately 732 million people worldwide are susceptible to this infection [

2]. In sub-Saharan Africa, schistosomiasis is the second most widespread NTD after malaria [

3]. The African continent is affected by four Schistosoma species: Schistosoma mansoni (intestinal), Schistosoma haematobium (urogenital), Schistosoma intercalatum (intestinal), and Schistosoma guineensis (intestinal) [

4]. Among these, S. mansoni and S. haematobium are the most prevalent and widespread, while S. intercalatum and S. guineensis are rare and confined to central African countries [

5].

Humans contract schistosomiasis through contact with freshwater contaminated with skin-penetrating cercariae [

3]. Acute infections can cause symptoms such as malaise, skin rashes, fever, and abdominal pain, while chronic infections are associated with liver, lung, intestinal, or urogenital diseases, depending on the Schistosoma species involved [

6]. Prolonged exposure to the infection can lead to severe complications, including bladder cancer, pulmonary hypertension, and urinary tract obstructions, potentially resulting in death. In endemic regions, schistosomiasis predominantly affects children aged 5 to 15 years and populations living near water bodies [

6]. Factors contributing to the high risk among school-aged children include poor hygiene, frequent exposure to contaminated water, and low levels of education. The disease is more prevalent in impoverished rural communities, particularly in areas where fishing and agriculture are common. Daily activities such as washing clothes and fetching water from infected rivers expose women and children to the infection, while recreational activities like swimming in contaminated water bodies increase children’s vulnerability [

2]. Schistosomiasis negatively impacts children’s development, pregnancy outcomes, and agricultural productivity, perpetuating poverty among approximately 500 million inhabitants of sub-Saharan Africa [

3].

Diagnosis of schistosomiasis involves microscopic examination of stool and urine samples to detect Schistosoma eggs, which are identifiable by their distinctive size, shape, and lateral spine [

7]. Preventative measures include providing access to clean tap water, preventing sewage contamination of freshwater, and removing intermediate host snails [

1]. Praziquantel is an effective treatment, curing 75%-85% of S. haematobium and 65%-85% of S. mansoni infections [

8].

Currently, there is limited documented literature on the incidence of schistosomiasis in the Eastern Cape province. This gap in knowledge underscores the necessity of conducting a retrospective study to ascertain the incidence of schistosomiasis in three districts of the Eastern Cape from 2019 to 2021. This study aims to evaluate the negative impacts of schistosomiasis on the community and compare its incidence across the three major districts of the Eastern Cape province.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

A cross-sectional retrospective study was conducted using secondary data from patients with microscopically confirmed schistosomiasis collected between 2019 and 2021. The study covered three districts in the Eastern Cape Province: Alfred Nzo, Amatole, and OR Tambo. Both rural and semi-urban areas were included, with rural areas comprising Bizana, Butterworth, Centane, Elliotdale, Flagstaff, Idutywa, Lusikisiki, Libode, Mqanduli, Port St. Johns, and Willowvale, and the semi-urban area being Mthatha.

Population and Sampling

The study population included patients of all ages who submitted urine samples for schistosomiasis testing in the specified districts. After ethical approval (protocol number 129/2021), a simple random sampling method was used to select 337 clinical records from the NHLS of Mthatha. There were no exclusion criteria, and patients of all ages and genders during the study period were included. The data information includes demographic characteristics of the participants, Geographic distribution of the disease, as well as Leucocytes, Erythrocytes, Epithelial cells, Casts, Crystals, Parasite, and bacterial culture results. All these information was transferred on excel sheet for data analysis.

Data Analysis

Hospital records from the National Health Laboratory Services (NHLS) Microbiology Department of Mthatha were analyzed using SPSS version 20. Statistical tests, including Fisher’s exact test, Pearson’s Chi-squared test, and Wilcoxon rank sum test, were employed to compare demographic variables. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess the normality of quantitative data. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data, and results were presented in the form of graphs and tables.

Results

A total of 337 Schistosoma spp. positive patient records were obtained from the National Health Laboratory Service (NHLS) of Mthatha, Microbiology Department. The study encompassed patients of all ages from three districts in the Eastern Cape: Alfred Nzo, Amatole, and OR Tambo. Detailed demographic information is presented in

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics

The demographic characteristics of the study population are summarized in

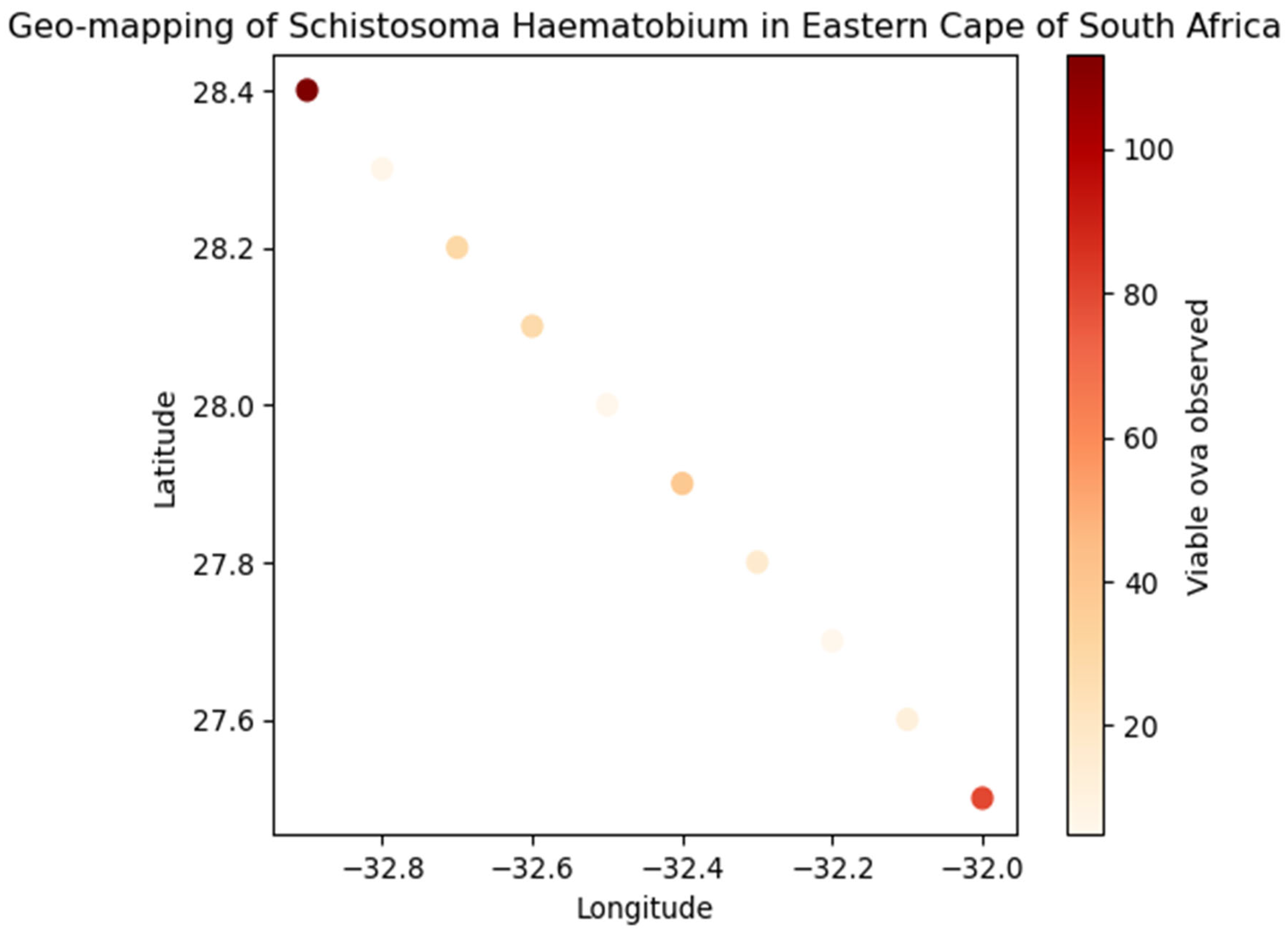

Table 1. Age distribution showed the highest prevalence in the 10-19 age group 61.1%, followed by the 0-9 age group (24%), the age group of 20 and above was 14.8%.

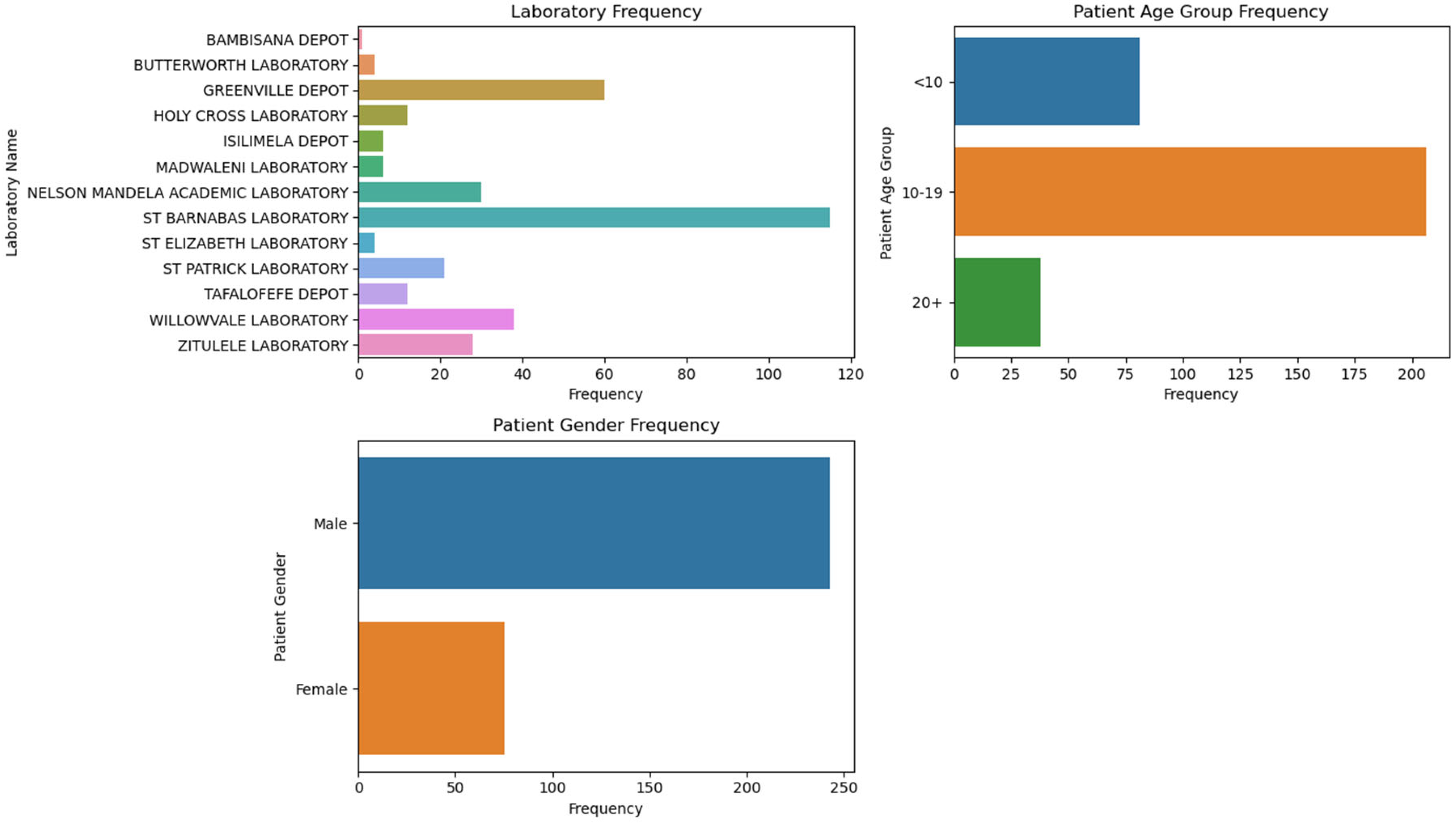

Geographic Distribution

The geographic distribution of schistosomiasis cases revealed that the majority were from OR Tambo district (73.3%, 95% CI: 65.9–80.7), followed by Amatole (20.7%, 95% CI: 13.8–27.5) and Alfred Nzo (6%, 95% CI: 1.9–10.1). Laboratory frequencies show that St Barnabas Laboratory had the highest frequency of cases (34.1%), followed by Greenville Depot (17.8%) and Willowvale Laboratory (11.3%).

Bacterial Culture Results

Bacterial culture results indicated that 33.3% (95% CI: 25.4–41.2) of the patients had a positive bacterial culture, while 20.6% (95% CI: 13.8–27.4) had a negative bacterial culture.

Statistical Analysis

The median age of females was 14 years (IQR: 11.0–19.2), while the median age of males was 12 years (IQR: 10.0–14.0), with a statistically significant difference (p=0.013). Age-specific prevalence rates showed significant differences between genders in the 0-9 (p=0.003) and 20-29 (p=0.003) age groups. Geographic distribution analysis indicated no significant difference in prevalence between genders in OR Tambo (p=0.11) and semi-urban areas (p=0.4).

Table 2.

Summary of Diagnostic and Epidemiological Data for Schistosomiasis in Eastern Cape.

Table 2.

Summary of Diagnostic and Epidemiological Data for Schistosomiasis in Eastern Cape.

| Category |

Subcategory |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Sample Type |

Urine |

333 |

98.8 |

|

|

| |

Blood |

1 |

0.3 |

|

|

| |

Both Blood and Urine |

3 |

0.9 |

|

|

| |

Total |

337 |

100.0 |

|

|

| Leucocytes |

<750000 |

118 |

|

65.9 |

|

| |

750000+ |

61 |

|

34.1 |

|

| |

Total |

179 |

|

100.0 |

|

| Erythrocytes |

<750000 |

58 |

|

31.7 |

|

| |

750000+ |

125 |

|

68.3 |

|

| |

Total |

183 |

|

100.0 |

|

| Epithelial cells |

1+ |

65 |

|

34.6 |

|

| |

2+ (Moderate) |

15 |

|

8.0 |

|

| |

3+ (Numerous) |

9 |

|

4.8 |

|

| |

Not Observed |

99 |

|

52.7 |

|

| |

Total |

188 |

|

100.0 |

|

| Casts |

Casts Present |

45 |

|

23.9 |

|

| |

Not Observed |

143 |

|

76.1 |

|

| |

Total |

188 |

|

100.0 |

|

| Crystals |

Crystals Present |

14 |

4.2 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

| |

Missing |

323 |

95.8 |

|

|

| |

Total |

337 |

100.0 |

|

|

| Parasite |

Parasite Present |

8 |

|

88.9 |

|

| |

Not Observed |

1 |

|

11.1 |

|

| |

Total |

9 |

|

100.0 |

|

| Schistosoma Haematobium ova |

Viable ova observed |

331 |

98.2 |

|

|

| |

No ova observed |

6 |

1.8 |

|

|

| |

Total |

337 |

100.0 |

|

|

| Antimicrobial Substances |

Present |

117 |

|

46.4 |

|

| |

Absent |

135 |

|

53.6 |

|

| |

Total |

252 |

|

100.0 |

|

| Erythrocytes during Ova Exam |

1+ |

12 |

|

5.3 |

|

| |

2+ (Moderate) |

19 |

|

8.4 |

|

| |

3+ (Numerous) |

193 |

|

85.4 |

|

| |

Not Observed |

2 |

|

0.9 |

|

| |

Total |

226 |

|

100.0 |

|

| Sensitivity Status |

Sensitive to one Antibiotics |

40 |

|

87.0 |

|

| |

Sensitive to two Antibiotics |

4 |

|

8.7 |

|

| |

Sensitive to three Antibiotics |

2 |

|

4.3 |

|

| |

Total |

46 |

|

100.0 |

|

Figure 1.

Distribution of samples across different laboratories, the age groups of patients, and the gender distribution.

Figure 1.

Distribution of samples across different laboratories, the age groups of patients, and the gender distribution.

Figure 2.

Geo-mapping of Schistosoma haematobium in Eastern Cape of South Africa.

Figure 2.

Geo-mapping of Schistosoma haematobium in Eastern Cape of South Africa.

Discussion

Schistosomiasis, a parasitic disease caused by blood flukes of the genus

Schistosoma, remains a significant public health challenge in many tropical and subtropical regions. The risk factors associated with schistosomiasis are multifaceted, encompassing environmental, socio-economic, and behavioral elements. The presence of freshwater bodies that harbor the intermediate snail hosts is a primary environmental risk factor for schistosomiasis. These snails release larval forms of the parasite, which can penetrate human skin upon contact with infested water. Regions with abundant lakes, rivers, and irrigation systems, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, are hotspots for transmission [

9]. Seasonal variations and water management practices also influence the prevalence of the disease, with higher transmission rates often observed during the rainy season when water bodies expand and human contact with water increases [

10].

Schistosomiasis, also known as bilharzia, is a parasitic disease that significantly impacts public health, particularly in tropical and subtropical regions. The distribution and prevalence of schistosomiasis are heavily influenced by various socio-demographic factors, including age, gender, socio-economic status, and geographic location. Addressing these factors through targeted interventions, improved access to healthcare, and comprehensive health education programs is crucial for the effective control and eventual elimination of schistosomiasis.

The findings of this study indicate a significant prevalence of schistosomiasis in the Eastern Cape Province, particularly in rural areas. The high prevalence in rural areas may be attributed to limited access to clean water and sanitation facilities, which are critical factors in the transmission of schistosomiasis. Age and gender are critical factors in the epidemiology of schistosomiasis. Studies have shown that school-aged children and young adults are at a higher risk of infection due to their frequent contact with contaminated water sources [

11]. This age group often engages in activities such as swimming, fishing, and playing in water, which increases their exposure to the parasite. Additionally, women, particularly those involved in domestic chores, are also at significant risk. Female genital schistosomiasis is a severe manifestation of the disease that affects many women in endemic regions [

12]. Socio-economic status plays a pivotal role in the prevalence of schistosomiasis. The disease predominantly affects poor and rural communities where access to clean water and adequate sanitation is limited [

13]. In these areas, people are more likely to encounter contaminated water, increasing their risk of infection. Furthermore, lower socio-economic status is often associated with limited access to healthcare services, which can delay diagnosis and treatment, exacerbating the disease burden [

14].

Geographic location is another significant determinant of schistosomiasis prevalence. The disease is most prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa, which accounts for over 85% of the global cases. In these regions, environmental factors such as the presence of freshwater bodies that harbor the intermediate snail hosts contribute to the high transmission rates. Additionally, socio-cultural practices and local water management strategies can influence the spread of the disease.

The knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) of individuals and communities regarding schistosomiasis also influence its prevalence. In many endemic areas, there is a lack of awareness about the disease and its transmission routes. Misconceptions and cultural beliefs can hinder the adoption of preventive measures and the utilization of treatment services. Comprehensive health education programs tailored to the local context are essential to improve KAP and reduce the disease burden.

The socio-demographic variables discussed above significantly influence the population of patients with schistosomiasis. Addressing these factors through targeted interventions, improved access to healthcare, and comprehensive health education programs is crucial for the effective control and eventual elimination of schistosomiasis. The risk of Schistosoma infections transmission increases with varying factors. These risk factors associated with schistosomiasis are diverse and interconnected. Environmental conditions, socio-economic status, occupational exposure, behavioral practices, and demographic characteristics all contribute to the transmission and prevalence of the disease. Addressing these risk factors through comprehensive public health strategies, including improved water and sanitation infrastructure, health education, and targeted treatment programs, is essential for the effective control and eventual elimination of the disease.

Socio-economic status is a critical determinant of schistosomiasis risk. The disease predominantly affects impoverished communities with limited access to clean water and adequate sanitation. In these areas, people are more likely to use contaminated water for drinking, bathing, and other domestic activities, increasing their exposure to the parasite. Additionally, lower socio-economic status often correlates with reduced access to healthcare services, leading to delayed diagnosis and treatment. Occupational exposure, particularly those that involve frequent contact with water are associated with a higher risk of schistosomiasis. Agricultural workers, fishermen, and individuals involved in irrigation projects are particularly vulnerable. These occupations often require prolonged exposure to infested water, facilitating the transmission of the parasite. Women engaged in domestic chores, such as washing clothes in rivers or lakes, are also at significant risk. Behavioral practices play a significant role in the transmission of schistosomiasis. Activities such as swimming, bathing, and playing in contaminated water are common among school-aged children, making them one of the most affected groups. Lack of awareness about the disease and its transmission routes further exacerbates the risk. In many endemic areas, cultural practices and misconceptions about the disease hinder the adoption of preventive measures.

Schistosomiasis, particularly caused by Schistosoma haematobium, presents various diagnostic and epidemiological challenges. The data provided by this study offers insights into the sample types, cellular components, and other diagnostic parameters associated with schistosomiasis. Comparing these findings with other research can highlight similarities and differences in the epidemiology and pathology of the disease. Many samples in the provided data were urine (98.8%), with very few blood samples (0.3%) or both blood and urine samples (0.9%). This aligns with the standard diagnostic practice for S. haematobium, which primarily affects the urinary tract, making urine the most relevant sample type for detecting ova. Other studies also emphasize the use of urine samples for diagnosing urogenital schistosomiasis due to the high concentration of eggs in urine. The presence of leucocytes and erythrocytes in urine is indicative of inflammation and bleeding in the urinary tract, common in schistosomiasis. In the provided data, 65.9% of samples had leucocyte counts below 750,000, while 34.1% had counts above this threshold. For erythrocytes, 68.3% of samples had counts above 750,000. These findings are consistent with other research indicating that schistosomiasis often leads to hematuria (blood in urine) and pyuria (pus in urine) due to the inflammatory response to the eggs.

Epithelial cells and casts in urine are markers of renal and urinary tract pathology. In the provided data, 34.6% of samples had 1+ epithelial cells, while 23.9% had casts present. This is like findings in other studies where epithelial cell shedding and cast formation are observed in patients with schistosomiasis, reflecting damage to the urinary tract lining. The presence of crystals and yeast in urine can indicate secondary infections or metabolic disturbances. In the provided data, 4.2% of samples had crystals, and 80% of yeast-positive samples had yeast present. These findings are less commonly reported in schistosomiasis-specific studies but can occur due to the compromised urinary tract environment.

The presence of parasites and viable S. haematobium ova in most samples (88.9% and 98.2%, respectively) confirms active infection. These high detection rates are consistent with other studies in endemic areas where the prevalence of S. haematobium is high.

Antimicrobial Substances and Sensitivity Status

The presence of antimicrobial substances in 46.4% of samples and varying sensitivity to antibiotics reflect the potential for secondary bacterial infections and the need for appropriate antimicrobial therapy. This is supported by other research indicating that schistosomiasis patients often require treatment for concurrent bacterial infections.

The provided data on schistosomiasis aligns with findings from other research in terms of sample types, cellular components, and diagnostic parameters. The high prevalence of urinary tract involvement, the presence of inflammatory markers, and the need for timely sample processing are consistent themes. These similarities underscore the importance of standardized diagnostic practices and comprehensive management strategies to address the multifaceted impact of schistosomiasis. The study, therefore, highlights the need for targeted public health interventions and continuous monitoring to control and prevent schistosomiasis in the Eastern Cape Province. Efforts should focus on improving access to clean water and sanitation, as well as raising awareness about the disease and its transmission.

Demographic Characteristics of studied population demonstrate interesting trend in the prevalence of schistosomiasis in Eastern Cape, South Africa. The study shows a significantly higher prevalence of schistosomiasis in males (78.7%) compared to females (21.3%). This aligns with other studies, such as one conducted in Ethiopia, which also found higher prevalence rates in males [

15]. However, some studies, like those in urban and peri-urban settings, have reported less pronounced gender differences [

16]. Age plays important role in transmission of schistosomiasis globally. In this study, the highest prevalence was observed in the 10-19 age group (69.3%), followed by the 0-9 age group (22%). This is consistent with global trends where school-aged children are often the most affected due to their increased exposure to contaminated water [

17]. A systematic review in Ethiopia also found higher prevalence among pediatric age groups [

15].

Geographic distribution of schistosomiasis in Eastern Cape of South Africa indicates that most cases were from OR Tambo district (73.3%), followed by Amatole (20.7%) and Alfred Nzo (6%). This regional concentration is like findings in other endemic areas where certain districts or regions report higher prevalence due to environmental and socio-economic factors. For instance, a study in Nigeria found significant regional variations in schistosomiasis prevalence [

18]. The study found that 33.3% of patients had a positive bacterial culture. This is an interesting finding as it suggests a co-infection scenario, which is not uncommon in schistosomiasis-endemic areas. Other studies have also reported bacterial co-infections, which can complicate the clinical management of schistosomiasis [

11]. The findings of this study show that there are statistically significant differences in age-specific prevalence rates between genders in the 0-9 and 20-29 age groups. This is consistent with other research that has shown age and gender-specific variations in schistosomiasis prevalence [

15]. While this study focuses on specific districts, other studies have highlighted the differences between urban and rural prevalence. For example, a systematic review [

16] found that urban areas are increasingly reporting schistosomiasis cases, although traditionally considered a rural disease. Though this study did not consider association between schistosomiasis and anemia, some literature [

15] show that there is strong association of schistosomiasis with anemia particularly in children and pregnant women which calls for concern. This could be an area for further investigation in Eastern Cape of South Africa.

Overall, this study’s findings are largely consistent with existing literature, particularly regarding gender and age distribution. However, the geographic concentration and bacterial co-infection rates provide additional insights that could be valuable for targeted interventions.

The Implications of This Research

The implications of this research on the incidence and partial geo-mapping of schistosomiasis in the Eastern Cape are significant and multifaceted:

Public Health Improvement

By identifying the incidence rates and geographical distribution of schistosomiasis, this study can help public health officials target interventions more effectively. This could lead to better allocation of resources, such as medications and educational programs, to the areas most affected.

Policy Development

The findings can inform policymakers about the severity and spread of schistosomiasis in the Eastern Cape, prompting the development of targeted health policies and strategies to combat the disease. This could include improved sanitation infrastructure, access to clean water, and health education campaigns.

Community Awareness and Education

Increased awareness and understanding of schistosomiasis among local communities can lead to better prevention practices. Educating communities about the risks and prevention methods can reduce the incidence of the disease.

Economic Impact

By reducing the prevalence of schistosomiasis, the study can contribute to improved agricultural productivity and economic stability in affected areas. Healthier populations are more capable of contributing to the local economy, particularly in rural areas where agriculture is a primary livelihood.

Future Research

The study can serve as a foundation for future research on schistosomiasis in the region. It can highlight areas that require further investigation, such as the effectiveness of different intervention strategies or the long-term impacts of the disease on affected populations.

Global Health Contributions

The research adds to the global body of knowledge on neglected tropical diseases, contributing valuable data that can be used by international health organizations to develop broader strategies for combating schistosomiasis worldwide.

Conclusion

The study on schistosomiasis in the Eastern Cape highlights significant diagnostic and epidemiological insights, particularly through geomapping. The data underscores the high prevalence of Schistosoma haematobium, primarily diagnosed via urine samples, reflecting the urinary tract’s involvement. The presence of inflammatory markers like leucocytes and erythrocytes in urine aligns with other studies, indicating common symptoms such as hematuria and pyuria.

Demographically, the study shows a higher prevalence in males (78.7%) and the 10-19 age group (69.3%), consistent with global trends. Geographically, most cases were concentrated in the OR Tambo district (73.3%), suggesting regional environmental and socio-economic factors at play.

The findings emphasize the need for targeted public health interventions, improved sanitation, and community education to control and prevent schistosomiasis. The study’s alignment with existing literature on gender, age distribution, and the presence of bacterial co-infections provides a robust basis for developing effective health policies and strategies in the Eastern Cape.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Postgraduate Education, Training, and Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Walter Sisulu University (protocol code 129/2021, dated 08:11:2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for this study was not obtained from the subjects involved in the study because the research involves no risk to the subjects, the primary data was collected for purposes of patient management and not for research, and was de-identified to reduce the risk to privacy.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions. The data contain sensitive information that could compromise the privacy of research participants. As such, access to these data is restricted and can only be provided upon reasonable request to the corresponding author, subject to approval by the relevant ethics review board.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the contributions made by Prof. Sandeep Vasaikar and Miss and Zizipho Ndlazulwana of Walter Sisulu University South Africa, and Dr Terfa Kene of AVE Health Sense Nigeria towards the development of this manuscript. Prof S Vasaikar provided access to NHLS data base to extract required information for the research while Miss Z Ndlazulwana assisted with capturing of about half of the information on excel sheet to ease the functions of data analysis. Dr T Kene provided useful guideline on how to analyse the data for this publication. The author also acknowledges and appreciate NHLS South Africa for granting Prof S Vasaikar the permission to allow the author access to their database.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest from any quarters. The study was not funded, it was purely the author’s initiative to research an issue that is under-researched within the province.

References

- Colley, D. G., Bustinduy, A. L., Secor, W. E., & King, C. H. (2014). Human schistosomiasis. The Lancet, 383(9936), 2253-2264. [CrossRef]

- Karunamoorthi, K., Almalki, M. J., & Ghailan, K. Y. (2018). Schistosomiasis: A neglected tropical disease of poverty: A call for intersectoral mitigation strategies for better health. Journal of Health Research and Reviews (In Developing Countries), 5(1), 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Adenowo, A. F., Oyinloye, B. E., Ogunyinka, B. I., & Kappo, A. P. (2015). Impact of human schistosomiasis in sub-Saharan Africa. Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases, 19(2), 196-205. [CrossRef]

- Mawa, P. A., Kincaid-Smith, J., Tukahebwa, E. M., Webster, J. P., & Wilson, S. (2021). Schistosomiasis morbidity hotspots: roles of the human host, the parasite and their interface in the development of severe morbidity. Frontiers in immunology, 12, 635869. [CrossRef]

- Adekiya, T. A., Aruleba, R. T., Oyinloye, B. E., Okosun, K. O., & Kappo, A. P. (2020). The effect of climate change and the snail-schistosome cycle in transmission and bio-control of schistosomiasis in Sub-Saharan Africa. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(1), 181. [CrossRef]

- Nelwan, M. L. (2019). Schistosomiasis: life cycle, diagnosis, and control. Current Therapeutic Research, 91, 5-9. [CrossRef]

- Gray, D. J., Ross, A. G., Li, Y. S., & McManus, D. P. (2011). Diagnosis and management of schistosomiasis. Bmj, 342. [CrossRef]

- Magaisa, K., Taylor, M., Kjetland, E. F., & Naidoo, P. J. (2015). A review of the control of schistosomiasis in South Africa. South African Journal of Science, 111(11-12), 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Adewale, B., Mafe, M. A., Mogaji, H. O., Balogun, J. B., Sulyman, M. A., Ajayi, M. B., ... & Balogun, E. O. (2024). Urinary schistosomiasis and anemia among school-aged children from southwestern Nigeria. Pathogens and Global Health, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2022). Schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiases: progress report, 2021. Weekly epidemiological record, 48(97), 621-632.

- Li, Q., Li, Y. L., Guo, S. Y., Li, S. Z., Wang, Q., Lin, W. N., ... & Xu, J. (2024). Schistosomiasis in Humans, 1990-2041: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease 2021 Study and Predictions by Bayesian Age-Period-Cohort Analysis. medRxiv, 2024-06. [CrossRef]

- Sacolo, H., Chimbari, M., & Kalinda, C. (2018). Knowledge, attitudes and practices on Schistosomiasis in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMC infectious diseases, 18, 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Díaz, A. V., Walker, M., & Webster, J. P. (2023). Reaching the World Health Organization elimination targets for schistosomiasis: the importance of a One Health perspective. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 378(1887), 20220274. [CrossRef]

- Aribodor, O. B., Azugo, N. O., Jacob, E. C., Ngenegbo, U. C., Onwusulu, N. D., Obika, I., ... & Nebe, O. J. (2024). Assessing urogenital schistosomiasis and female genital schistosomiasis (FGS) among adolescents in Anaocha, Anambra State, Nigeria: implications for ongoing control efforts. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 952. [CrossRef]

- Gebrehana, D. A., Molla, G. E., Endalew, W., Teshome, D. F., Mekonnen, F. A., & Angaw, D. A. (2024). Prevalence of schistosomiasis and its association with anemia in Ethiopia, 2024: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infectious Diseases, 24(1), 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Klohe, K., Koudou, B. G., Fenwick, A., Fleming, F., Garba, A., Gouvras, A., ... & Rollinson, D. (2021). A systematic literature review of schistosomiasis in urban and peri-urban settings. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 15(2), e0008995. [CrossRef]

- De Boni, L., Msimang, V., De Voux, A., & Frean, J. (2021). Trends in the prevalence of microscopically-confirmed schistosomiasis in the South African public health sector, 2011–2018. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 15(9), e0009669. [CrossRef]

- Shams, M., Khazaei, S., Ghasemi, E., Nazari, N., Javanmardi, E., Majidiani, H., ... & Asghari, A. (2022). Prevalence of urinary schistosomiasis in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis of recently published literature (2016–2020). Tropical Medicine and Health, 50(1), 12. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).