1. Introduction

CRISPR/Cas9 (Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR-associated 9) is the most widely used gene editing tool. CRISPR/Cas system was found in archaea, functions to defend against viral invasion by editing invading foreign genes [

1]. Harnessed as a gene editing tool, the Cas9 protein binds with sgRNA (small-guide RNA) sequence, which guides the Cas9/sgRNA to the target site of the genome [

2]. The HNH and RuvC endonuclease domain can conduct DNA cleavage, including the complementary and non-complementary strands of the DNA helix [

3]. Then lead to deletion and insertion of bases at the target site through DNA repair, thereby achieving the editing of the target genes. The CRISPR/Cas9 system has been used in genome design breeding across various livestock species, including sheep (

Ovis aries) [

4]. Molecular breeding techniques have been increasingly applied in sheep farming by using of target genes associated with economic traits. The Cas9 can perform precise editing in animals by microinjection of zygotes, followed by embryo transfer to produce genetically edited sheep [

5]. Targeted major gene is usually related to economic performance, such as growth rate and disease resistance [

6]. Achieving high-efficiency editing in zygotes is crucial for increasing the success rate of generating edited sheep and reducing costs. However, various conditions and factors can influence the efficiency of Cas9 editing in sheep via microinjection, it is necessary to optimize these conditions.

Previous studies have attempted to generate gene-edited sheep through microinjection, but the editing efficiency has not been satisfactory. How to elevate the efficiency of microinjection in sheep is rarely reported.

SOCS2 (suppressor of cytokine signaling 2) is associated with animals’ growth performance by regulating the GH/IGF1 (growth hormone/insulin-like growth factor 1) axis [

7,

8].

DYA (MHC class II antigen DY alpha) contribute to adaptive immunity of sheep and may related to resistance of nematodosis [

9,

10].

TBXT (T-box transcription factor T) is associated with tail length among sheep populations and vertebrae variation in mammals [

11,

12]. These genes have been previously utilized as target genes for generating gene-edited sheep models in our group. In this study, we optimized the efficiency of zygote editing via microinjection, specifically targeting the

SOCS2,

DYA, and

TBXT genes.

To identify optimal conditions for high editing efficiency, we performed in vitro maturation of sheep oocytes and used these mature oocytes as a model for zygote editing via microinjection. We developed and implemented an optimized microinjection system, which demonstrated significantly enhanced efficiency in sheep gene editing. This system provides a promising approach for generating gene-edited sheep with greatly improved editing success.

2. Results

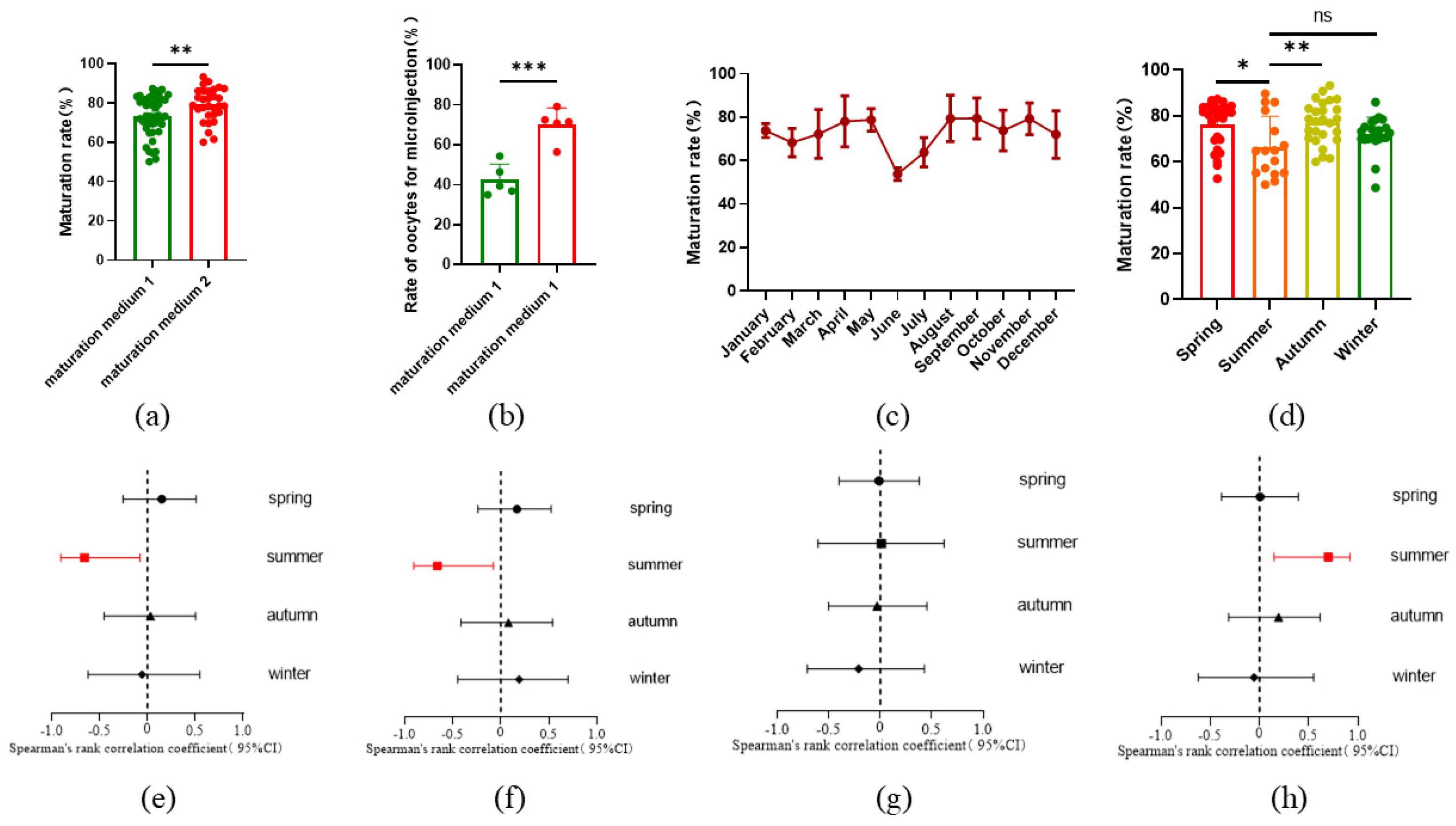

2.1. In vitro maturation rate of sheep oocytes influenced by seasonal variations

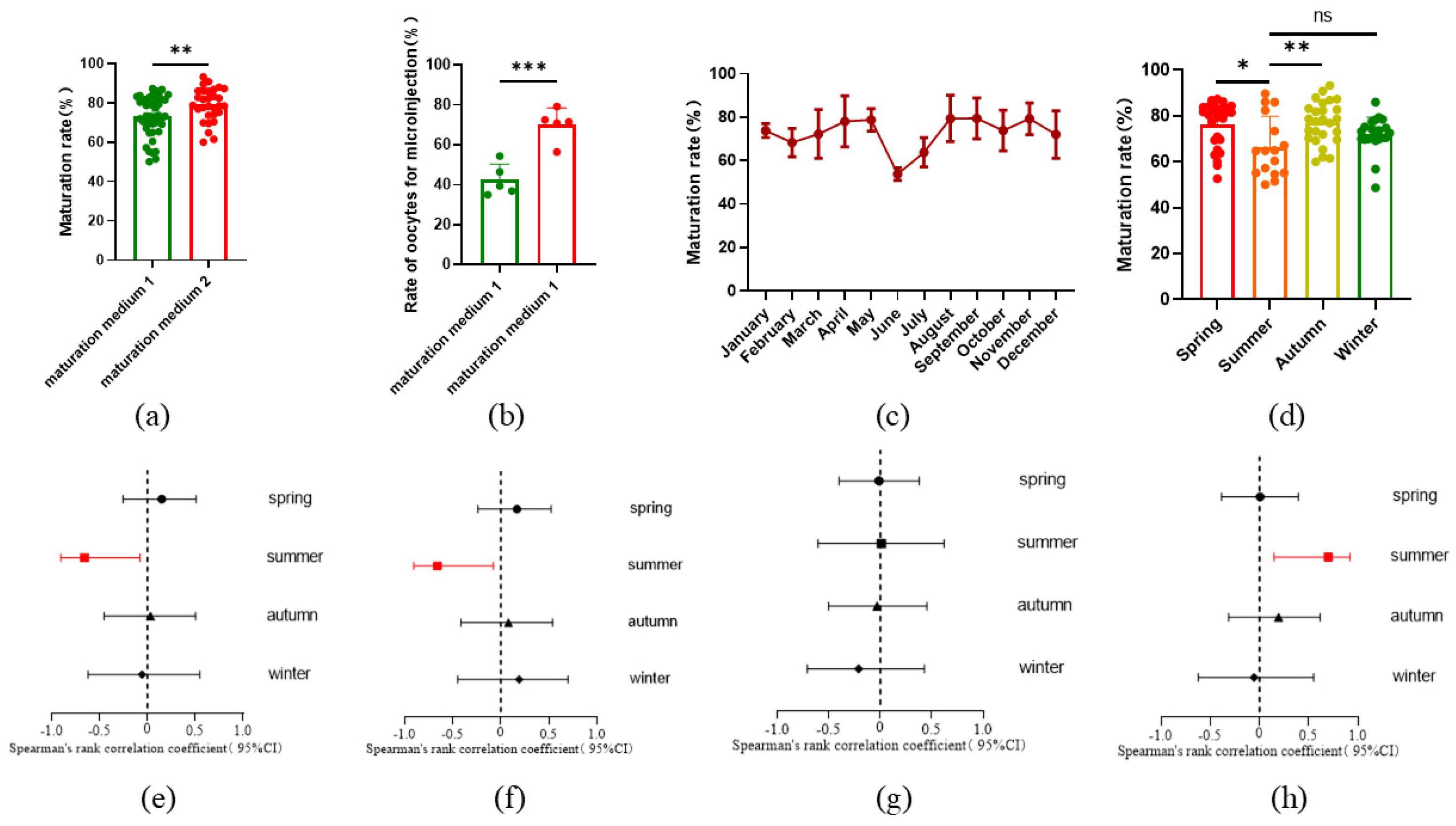

In this study, sheep oocytes matured in vitro were collected for microinjection. In order to increase the number of oocytes available for microinjection, we raised the concentration of LH and FSH in the in vitro maturation (IVM) medium from 0.05 IU to 0.1 IU. Additionally, fetal bovine serum (FBS) was replaced with estrus ovine serum (EOS) in the IVM process. As a result, the oocyte maturation rate increased from 73.19%±10.03% to 79.10%±8.45% (

Figure 1a), and the number of oocytes suitable for microinjection significantly rose from 42.44%±7.93% to 70.14%±8.31% (

Figure 1b). Further analysis revealed that the oocyte maturation rate varied across different months and seasons, with higher rates observed in spring and autumn, and lower rates in summer (

Figure 1c and 1d). Our experiments were conducted in Beijing, located at a latitude of 41°N in northern China, a region characterized by four distinct seasons. We reviewed the climate data for Beijing, which included monthly averages for sunlight duration, air temperature, relative humidity, and atmospheric pressure. These climate variables also exhibited seasonal fluctuations (

Figure S1). A Spearman correlation analysis between oocyte maturation rate and these climate parameters revealed a negative association between maturation rate and both sunlight duration and air temperature, while relative humidity showed a positive correlation. No significant correlation was found between oocyte maturation rate and atmospheric pressure (

Figure 1e-h,

Table S1). The climate conditions in summer were identified as the primary factors influencing maturation.

2.2. Optimization of CRISPR/Cas9 editing microinjection system in oocytes

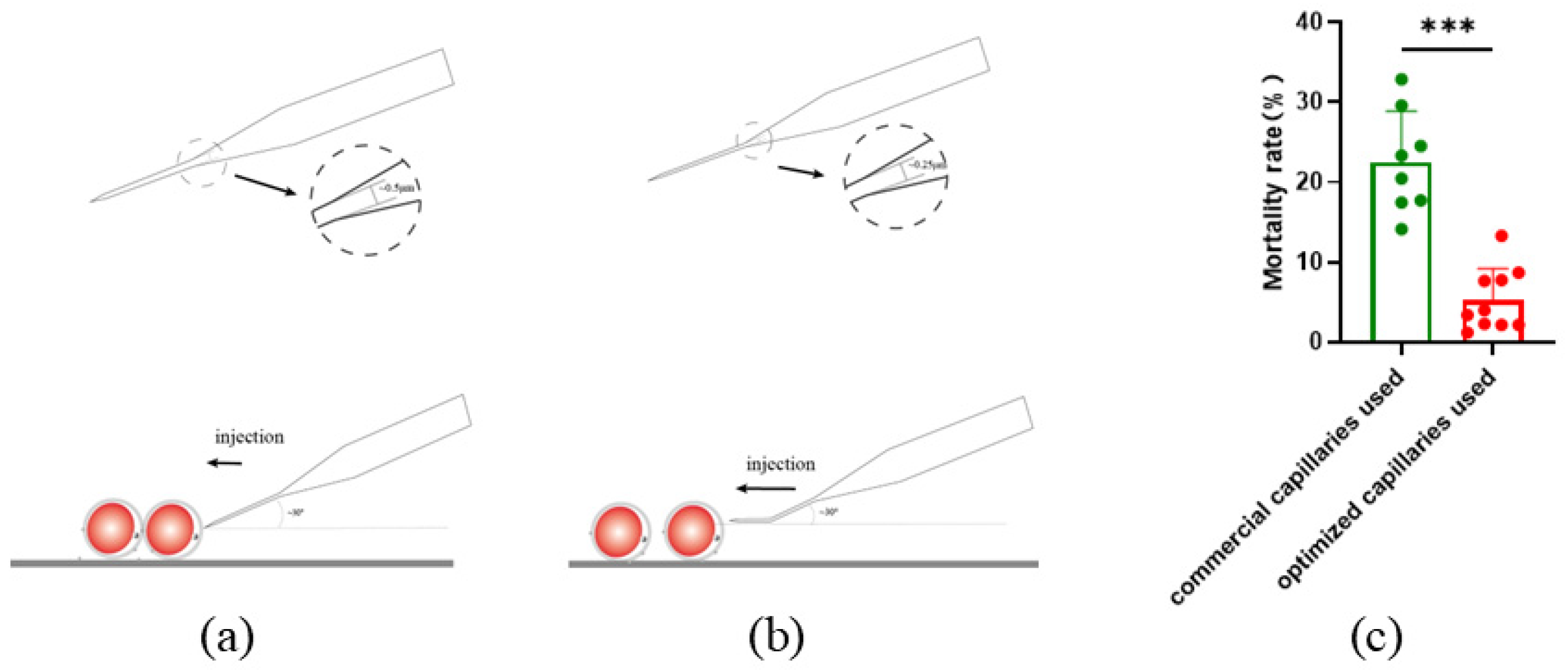

In this study, commercial microinjection capillaries were used for microinjection (

Figure 2a). With a diameter of 0.5 μm capillary and sloping injection during microinjection. The mortality rate of oocytes in 24 hours after injection was as high as 22.53%±6.38%. To lower the mortality rate, new microinjection capillaries with a 0.25 μm diameter and a 20–30° bend were developed. (

Figure 2b), the capillaries could be horizontally stabbed into the oocyte during injection. After using the new capillaries, the mortality rate decreased to 5.28% ± 3.92% (

Figure 2c).

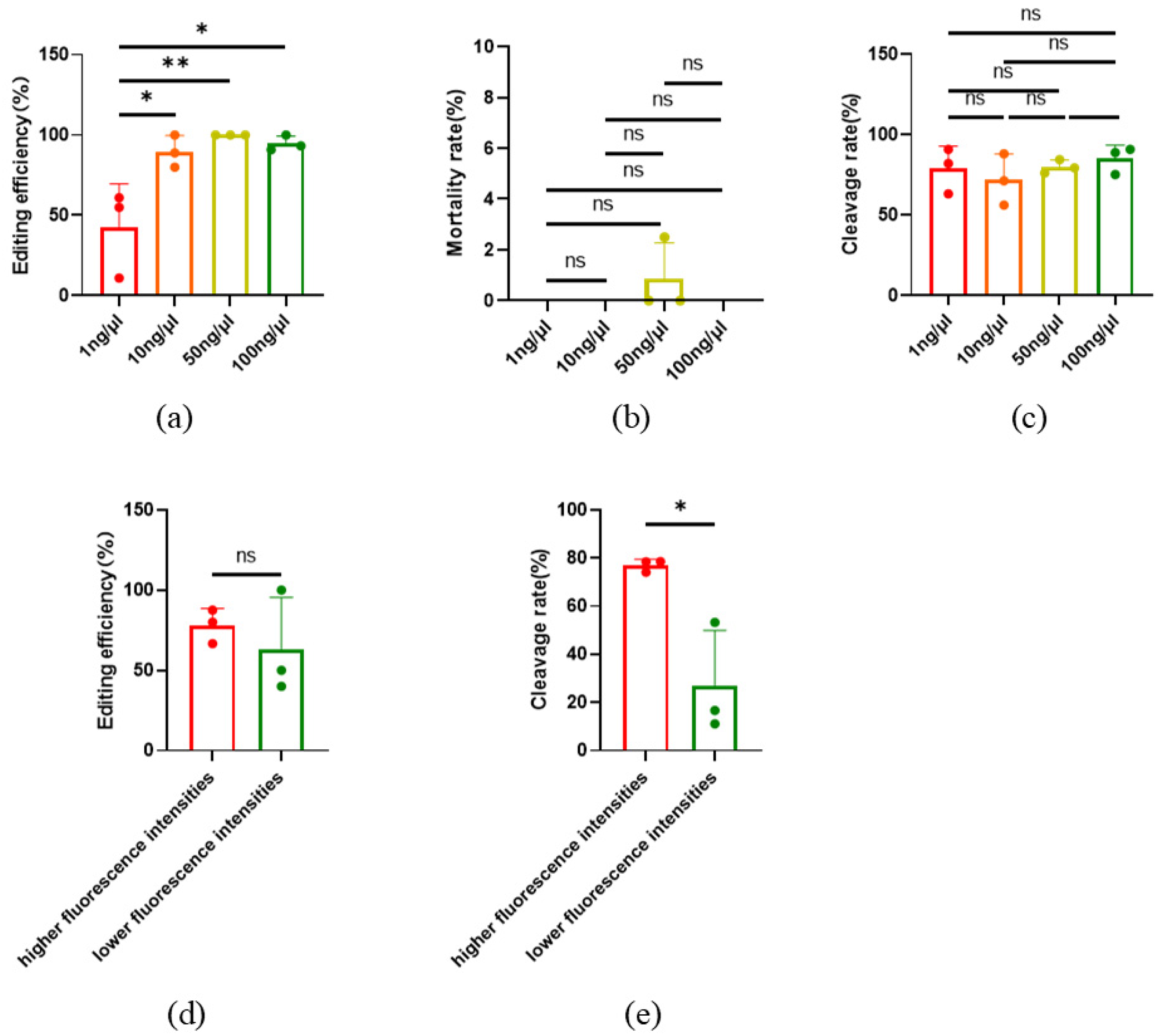

The concentration of sgRNA and Cas9 protein in the injection mixture may affect the efficiency of gene editing. In order to obtain the optimal concentration of sgRNA or Cas9 for gene editing efficiency, a concentration gradient was designed for gene editing. In additon, GFP mRNA was used as an indicator for co-injection. After injection, oocytes without GFP fluorescence were removed, and the gene editing efficiency targeted to SOCS2 was detected after the embryos developed to the morula stage. The results showed that SOCS2 was edited by 1ng/μl sgRNA and Cas9 protein successfully, but the gene editing efficiency was low (42.41%±27.28%). When the concentrations of sgRNA and Cas9 protein were 10ng/μl or higher, the SOCS2 gene editing efficiency could reach nearly 100% (Fig. 3a). At the same time, there was no significant difference in the mortality rate and cleavage rate between the injected and non-injected oocytes (Fig. 3b-c). Furthermore, we found that after injection of GFP mRNA, the oocytes displayed different fluorescence intensities. By detecting the gene editing efficiency (targeted to TBXT) of oocytes with significantly different fluorescence intensities, the result showed that the oocytes with higher fluorescence intensity had higher gene editing efficiency (

Figure 3d), while the cleavage rate also significantly increased (

Figure 3e).

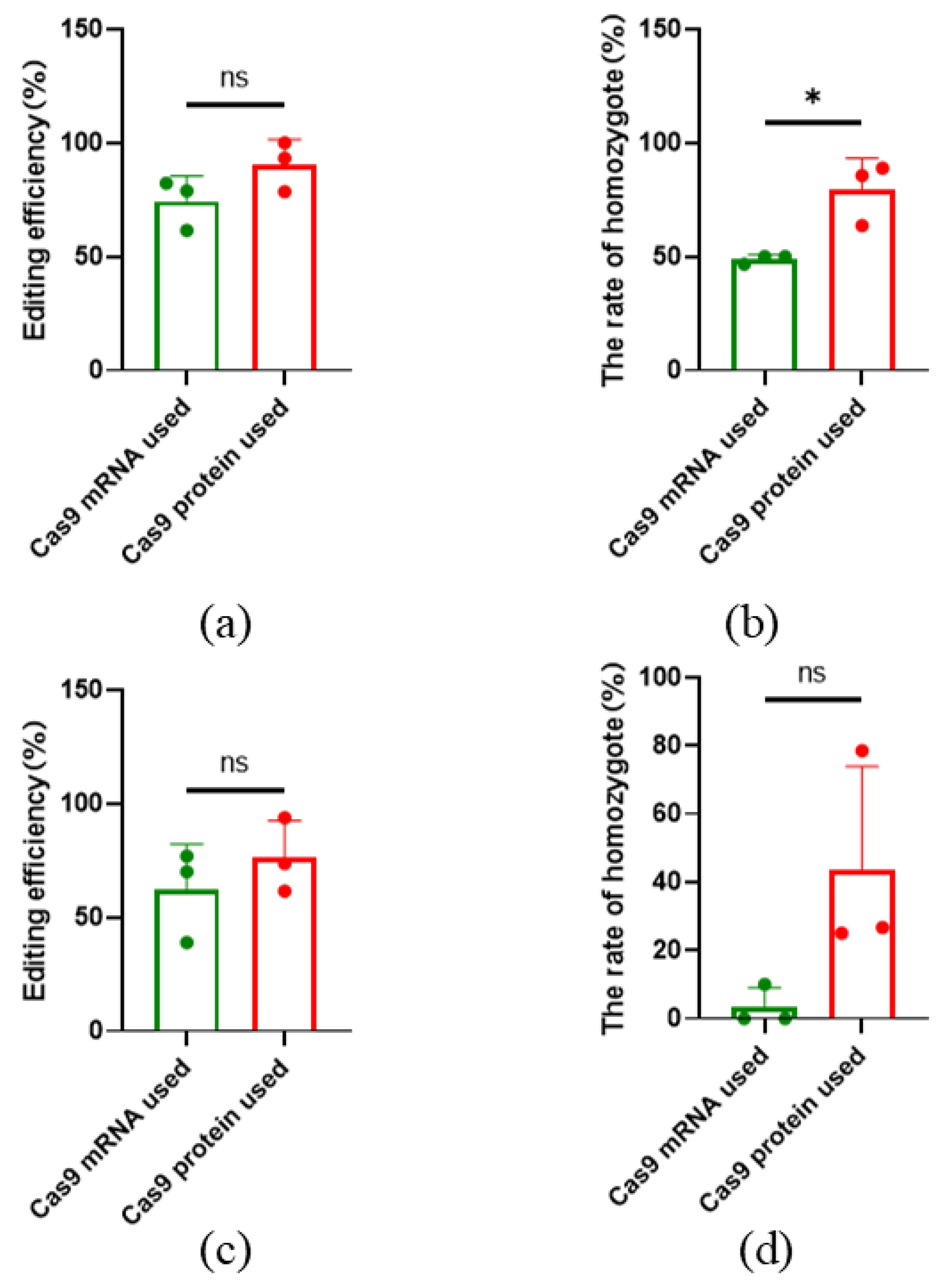

Cas9 mRNA, combined with sgRNA, can also be used for gene editing. This study compared the gene editing efficiency of commercial Cas9 protein and mRNA. When targeting SOCS2, the average editing efficiency was 74.28%±11.16% with mRNA, and the homozygous editing efficiency was 48.89%±1.92%. In contrast, the use of Cas9 protein resulted in an average editing efficiency of 90.63%±10.97% and a homozygous efficiency of 79.41%±13.75% (

Figure 4a-b). For the TBXT gene, the average editing efficiency with mRNA was 62%±20.26%, with a homozygous efficiency of 3.33%±5.77%. When using Cas9 protein, the average editing efficiency was 76%±16.27%, and the homozygous efficiency was 43.41%±30.46% (

Figure 4c-d) (

Table S2). While the overall editing efficiency did not show significant differences between the two methods, there was a notable difference in homozygous editing rates for SOCS2.

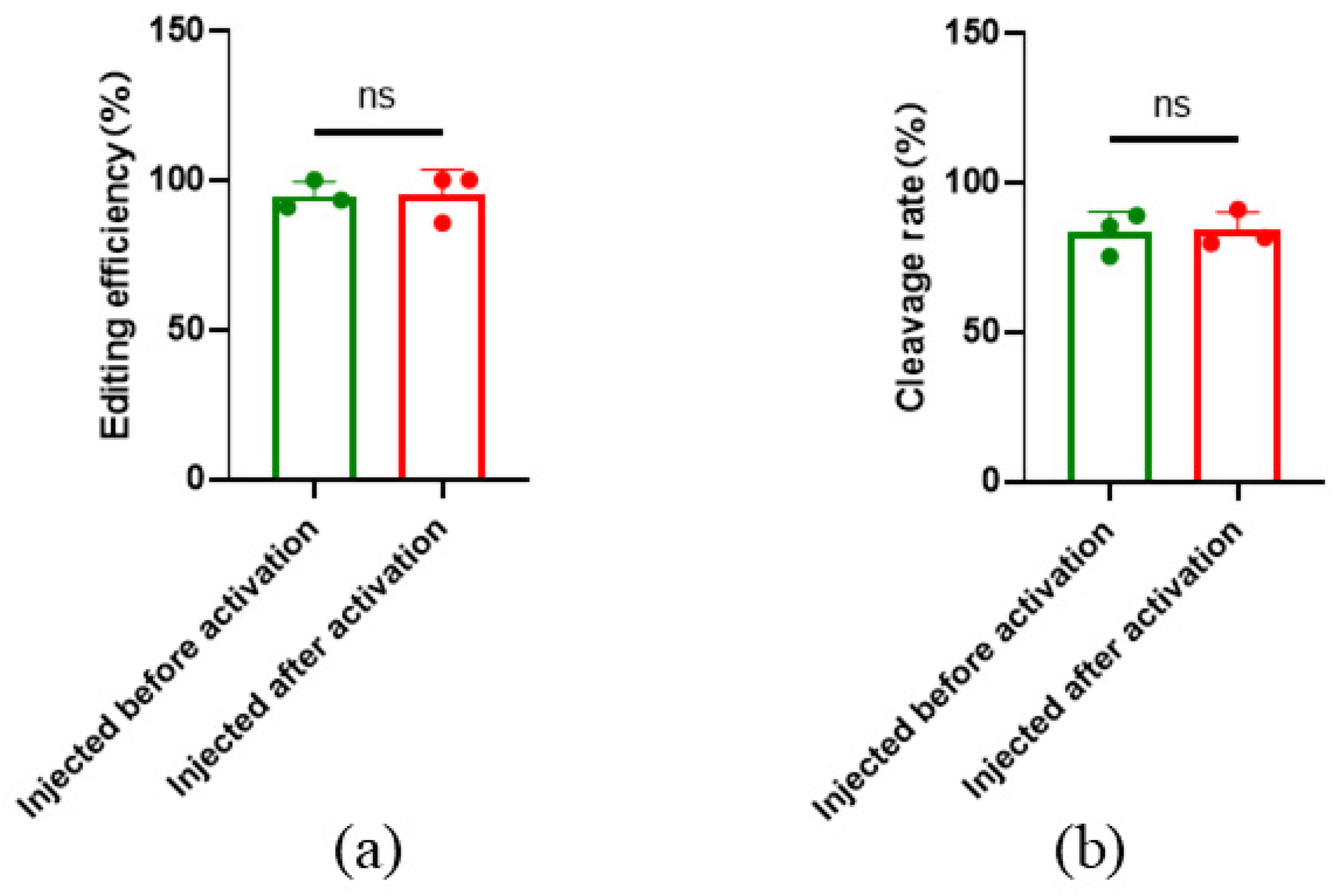

To investigate the influence of parthenogenetic activation on the gene editing efficiency of oocytes, microinjection before and after parthenogenetic activation was performed, and editing efficiency was calculated. The results showed that the overall efficiency targeted to SOCS2 was 94.74%±4.71% with microinjection before parthenogenetic activation, and the gene editing efficiency was 95.24%±8.25% with microinjection after parthenogenesis activation. There was no significant difference between editing efficiencies of microinjection before or after parthenogenetic activation (

Figure 5a), indicating that gene editing efficiency is not affected by parthenogenetic activation. In addition, the cleavage rate and blastocyst rate after parthenogenetic activation were also not significantly different from those before activation (

Figure 5b).

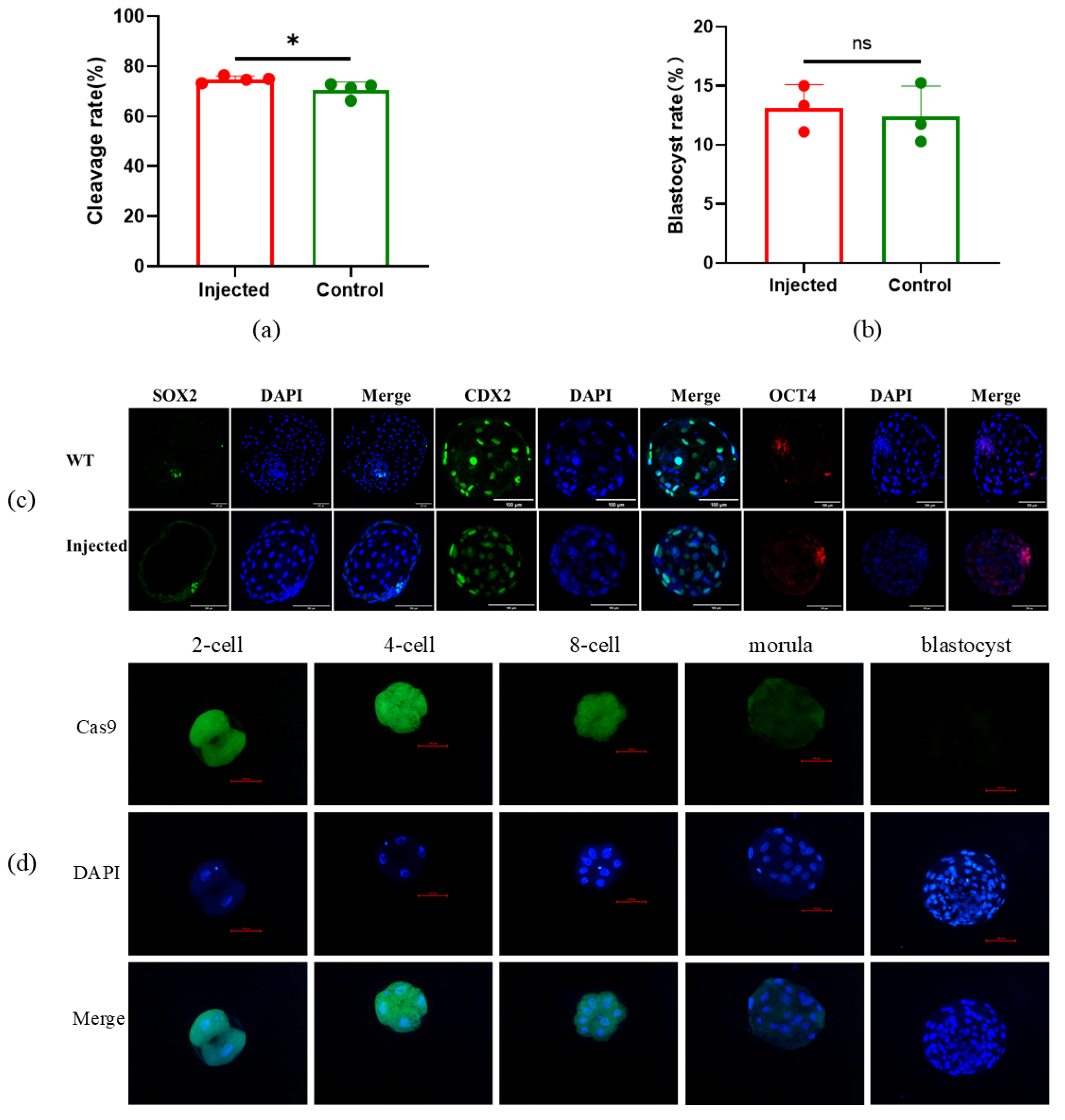

2.3. The development of early embryos was not influenced by microinjection

To detect the effect of microinjection on embryo development in this experiment, the development rate and blastocyst rate after injection were analyzed. The results showed that the 48h cleavage rate of the injected embryos was 74.87%±1.31%, while the 48h cleavage rate of the non-injected embryos was 70.73%±3.02% (

Figure 6a-b). The marker genes OCT4, SOX2, and CDX2 in the blastocyst stage were detected by immunofluorescence, and the expression of the marker genes was not influenced by injection (

Figure 6c). In addition, Cas9 proteins were also detected in early embryos after injection by immunofluorescence; Cas9 can keep activity to the morula stage of embryo, but not in the blastocyst stage (

Figure 6d).

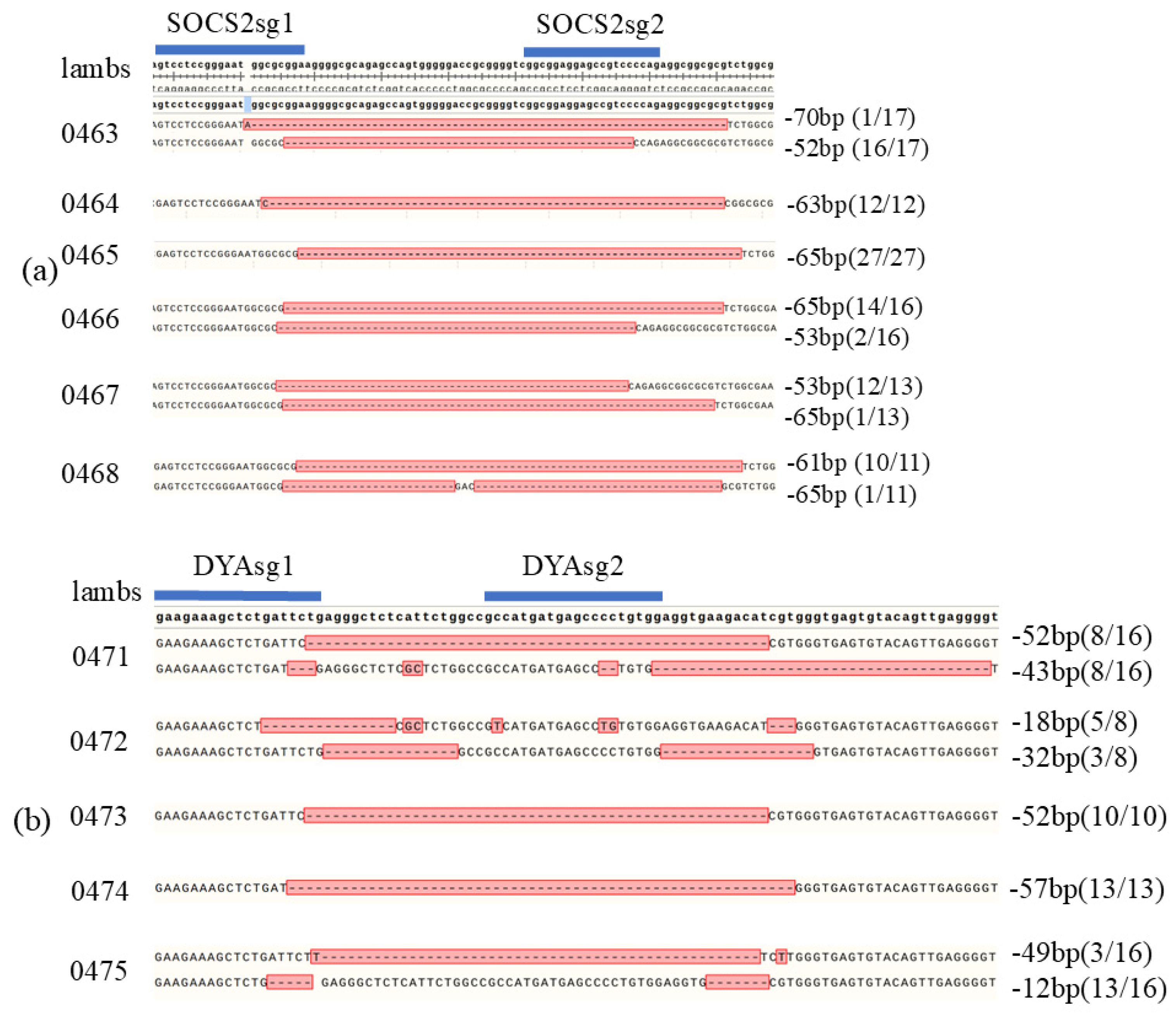

2.4. High-efficiency of CRISPR/Cas9 editing in sheep by microinjection

To access the efficiency of this editing system developed in this study in sheep, SOCS2 and DYA were targeted using co-injected sgRNA and Cas9 protein in zygotes obtained from ewes by superovulation. Gene-edited sheep were generated by embryo transfer. A total of 193 sheep zygotes were obtained from the donors. 47 zygotes injected with SOCS2 sgRNA were transferred to 7 recipient ewes, resulting in the natural delivery of 6 live lambs after 150 days of pregnancy. Editing of SOCS2 was confirmed in all 6 lambs. (

Figure 7a) (

Table 1). Additionally, 90 zygotes injected with DYA sgRNA were transplanted to 15 recipients. leading to the natural delivery of 5 live lambs, with editing of DYA detected in all 5 lambs. (

Figure 7b) (

Table 1). These results demonstrate that the gene-editing system established in this study enables efficient gene editing in sheep.

3. Discussion

Zygotes microinjection involves injecting nucleic acids and Cas9 protein or mRNA into zygotes by the transplantation of the edited zygotes into surrogates to generate offspring. Compared to somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT), microinjection is faster, more cost-effective, simpler in execution [

13], and results in higher surrogate pregnancy rates and higher offspring survival rate. However, since gene editing occurs directly in the zygotes, it is necessary to identify the offspring's genotype after birth. The success of generating edited animals is highly dependent on the efficiency of editing in zygotes, meaning that improving the gene-editing process in zygotes will result in more gene-edited offspring. In this study, through exploration of component concentration in injection mixture, optimization of injection capillary, comparison of injection before and after parthenogenetic, and comparison of Cas9 protein or mRNA, an optimized system of CRISPR/Cas9 editing in sheep oocytes via microinjection was constructed, the editing efficiency targeted to

SOCS2 and

DYA in sheep by microinjection of zygotes is 100%, which is higher compared to previous studies (5.7-97%) (

Table 2). Our study provides a method for improving gene editing efficiency when generating gene-edited sheep by microinjection.

This study found that using at least 10ng/μl Cas9 protein and sgRNA during microinjection can lead to high-efficiency editing in oocytes. For zygote microinjection, the concentration of Cas9 protein and sgRNA can be adjusted to exceed 10 ng/μl in the injection mixture. In gene editing of somatic cells or oocytes, vectors expressing both Cas9 protein and sgRNA can be used for liposome transfection or electroporation. Then the Cas9 protein and sgRNA were expressed to edited target gene. However, compared to plasmid transfection, transfection or injection of Cas9 protein and sgRNA can directly target to gene of interest without the possibility of integrating into the genome, making it faster and safer. The original Cas9 system relied on Cas9 protein, CRISPR-derived RNA (crRNA) and trans-activating RNA (tracrRNA). Jinek et al. simplified the system by linking crRNA and tracrRNA [

2], till now, the injection mixture only comprised Cas9 protein and sgRNA without any other components. Therefore, the concentration of the injection components is one of the critical factors that can affect gene editing efficiency. Currently, many commercialized Cas9 proteins can be used for microinjection, including Cas9 and cpf1 with different elements such as nuclear localization signals, tag proteins, and modifications to enhance its stability and safety [

26]. Those companies developed these Cas proteins declared that all products have been laboratory-verified with high editing efficiency and stability. However, when applicated in different species or target genes, the editing efficiency of these proteins still need to be detected, it is necessary to select appropriate commercial proteins according to different species and genes.

We optimized gene-editing efficiency using

in vitro matured embryos. Through parthenogenetic activation,

in vitro matured oocytes can develop to the blastocyst stage without fertilization [

27]. Therefore, the editing efficiency of mature oocytes can reflect that of early embryos. For target genes, multiple sgRNAs were designed, and high-efficiency sgRNAs were selected to generate edited animals. Assessing gene-editing efficiency in oocytes serves as a reference for selecting optimal sgRNAs for producing gene-edited animals. Our study found that oocyte maturation is influenced by seasonal climate conditions. Most sheep breeds exhibit seasonal estrus, largely due to variations in daylight duration. The climate at our experimental location (about 40°N, 116°E) is highly seasonal, and the oocyte maturation rate varied accordingly. This suggests that

in vitro maturation may be affected by factors like daylight duration, temperature, and humidity, which align with reports in other species [

28]. This result demonstrated that shorter sunlight duration, lower air temperature and higher relative humidity of environment are beneficial for increasing oocyte maturation rate, especially for the relative humidity.

We also observed that using Cas9 protein or mRNA led to different gene-editing outcomes for the TBXT gene but not for SOCS2. This discrepancy might be due to differences in mRNA translation after injection, as well as the unique characteristics of each target gene and its sgRNAs. Commercialized Cas9 proteins were more stable compared to mRNA, which requires translation after injection.

Additionally, we also investigated the influence of parthenogenetic activation on gene editing efficiency. Only unfertilized mature oocytes require parthenogenetic activation for development. This process involves elevating the Ca2+ levels in MⅡ oocytes through physical or chemical stimulation (in this study, ionomycin was used for chemical activation), which leads to the decline or inactivation of factors such as metaphase-promoting factor (MPF) and cytostatic factor (CSF), enabling the oocytes to enter the meiosis II period and further cleavage [

29]. During microinjection, the injection mixture is consisted by purified Cas9 protein, sgRNA, and nuclease-free water. In our study, the results also showed injections performed before or after activation do not impact development rates or editing efficiency. The result implied that the injection mixture did not affect Ca2+ level of oocytes and parthenogenetic activation, and activation also do not affect editing process. However, in zygotes microinjection,

in vivo or

in vitro fertilized oocytes were used, parthenogenetic activation is not a concern. Nevertheless, injections should be performed as soon as possible after fertilization to avoid editing after cleavage, which could result in genetic chimerism.

The generation of edited animals is influenced by multiple factors. Not only the design of sgRNAs or Cas9 editing efficiency but also improving the quality of donor embryos and optimizing the estrous cycle of recipient ewes are all significant. Reducing mortality post-microinjection improves zygote utilization rates can reduce the number of donors needed for recipients. While our high-efficiency editing system significantly advance the generation of gene-edited sheep, it does not guarantee 100% editing efficiency across all genes. Nevertheless, it provides a valuable framework for optimizing gene-edited animal production via zygote microinjection.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals and ethical statement

All sheep used in this study were bred by the Institute of Animal Sciences and Veterinary, Tianjin Academy of Agriculture Sciences in Tianjin. All experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Advisory Committee at the Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. All experiments were conducted according to the guidelines of the proposal (approval No. AP2023021).

4.2. sgRNA and Cas9 mRNA or protein

sgRNA template sequence was designed according to the conference sequence of

SOCS2 (Oar v4.0, NC019460.2),

DYA (Oar v4.0, NC019477.2), and

TBXT (Oar v4.0, NC 019465.2). SgRNAs were listed in

Table S2 and synthesized by Genescript, and sgRNAs were diluted with RNase-free water to 1μg/μl. Cas9 mRNA (eSpCas9 mRNA, MA13810) and GFP mRNA (eGFP mRNA, SC2325) were purchased from Genscript, and Cas9 protein was purchased from Invitrogen (TrueCut Cas9 v2 A36497).

4.3. Manufacture of capillaries for microinjection

Capillary glass (Sutter Instrument Company, BF-100-78-10) is pulled by a micropipette puller P-2000 under the condition of Ramp 469, Heat 465, Pull 130, Voltage 25 Time 140, Pressure 500 to produce a micropipette. The micropipette capillary was bended 20-30° by microforge MF-2 under a procedure of 65℃ and 2s duration.

4.4. In vitro maturation of sheep oocytes

Cumulus-oocyte complexes (COCs) were separated from purchased ovaries and transferred into in vitro mature medium including 0.2 mM Na-Pyvate (Sigma P3662), 1 mM L-Glutamine (Sigma G3126), 0.1 IU FSH (NSHF), 0.1 IU LH (NSHF), 20 ng/mL EGF (Sigma E9644), 100μM Cys (Sigma, C7352), 1μg/mL β-E2 (Sigma, E8875), 10% FBS or estrus ovine serum, and M199 (Gibco, 11150-059). The oocytes were cultured under 38.5°C, 5% CO2 for 20 h, then the mature oocytes were incubated in 1% hyaluronidase for 5 min to remove cumulus cells. Oocytes with the first polar body were selected for microinjection.

4.4. Microinjection

The injection mixture was consisted of sgRNA (1-100 ng/μl), Cas9 protein or mRNA (1-100 ng/μl), GFP mRNA (100 ng/l), RNAse-free water, 10μl in total. GFP mRNA was removed from the mixtures for zygotes microinjection. The mixture was put into the front end of the capillary (Eppendorf, 22290012 or developed artificially) and injected into the cytoplasm of mature oocytes or zygotes under pressure of 20–50 hPa and 1s duration controlled by eppendorf FemtoJet 4i. Injected oocytes or zygotes were recovered in IVM for 30 min.

4.5. Parthenogenetic activation and in vitro development

After injection, oocytes were incubated in 5μM ionomycin for 5 min (Merck 407951). Then the oocytes were transferred into 2 mM 6-DAMP (Sigma-D2629) for 2.5-4 h. Activated oocytes were transferred into G1 (Vitrolife, 10128) for 48 h and into G2 (Vitrolife, 10132) for 3-5 days under 38.5°C, 5% CO2, 5% O2, 90% N2.

4.6. Immunofluorescence

Early embryos were incubated in acid Tyrode’ solution (LEAGENE, CZ0060) for 3 min and fixed for 15 min in 4% paraformaldehyde. After permeabilizing samples by treating for 10 min with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS and blocking with 1% BSA in PBS. Samples were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C and secondary antibodies for 1 h at 37°C. Anti-OCT4 antibody (11263) was purchased from Proteintech, anti-SOX2 antibody (365823) was purchased from Santa Cruz, and anti-CDX2 antibody (MU392A-5UC) was purchased from BioGenex. Anti-Cas9 antibody (14697S) is purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Secondary antibody marked with CY3 (GB21301) was purchased from Servicebio. Secondary antibody marked with Alexa Fluor 488 (A11008) was purchased from Invitrogen. Finally, samples were stained with DAPI in fluoromount-G (Beyotime P0131) for 10 minutes and covered with mineral oil. Antibody binding was viewed with a laser-scanned Leica SP8 confocal microscope.

4.7. Statistical analysis

The meteorological data used in this study was downloaded from the National Meteorological Science Data Center, China Meteorological Administration (

https://data.cma.cn/). For quantitative data, if the distribution of different groups meets the normal distribution, a one-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) is used, the LSD (Least Significant Difference) LSD test is used when the variance is homogeneous, and the Games-Howell test is used when the variance is not homogeneous. If the distribution does not meet the normal distribution, the Kruskal-Wallis H test is used for multiple comparisons. For the correlation analysis between two groups of quantitative data, if both groups meet the normal distribution, the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient is used, otherwise, the Spearman rank correlation coefficient is used.

4.8. Generation of gene-edited sheep

Sheep zygotes were performed microinjected as follows. The injection mixture was consisted of sgRNA (1-100 ng/μl), Cas9 protein, RNAse-free water, 10μl in total. The mixture was injected into the cytoplasm of zygotes under pressure of 20–50 hPa and 1s duration controlled by eppendorf FemtoJet 4i. After injection, zygotes were transferred into the oviduct of synchronized estrous recipient sheep. We monitored the pregnancy status of the recipient for 142-155 days until delivery. All lambs were delivered naturally.

4.9. Genotyping of edited sheep

For early embryos, morula and blastocysts were selected and lysed according to the protocol of EZ-editor Lysis Buffer (YK-MV-1000) to obtain genomic DNA (gDNA). For lambs, venous blood or ear skin of the newborn lambs was collected, and gDNA was isolated according to protocols of the TIANGEN blood/cells/tissue DNA extraction kit (DP304-03) for genotyping. gDNA of embryos or lambs was used as a template for amplification of target genes. Primers of the target gene were shown in the

supplement Table S3. The PCR procedure is as follows: 95℃ for 1 minute, followed by 35 cycles of 95℃ for 10 seconds, 59℃ for 15 seconds, and 72℃ for 15 seconds, 72℃ for 5 minutes. PCR products were performed TA cloning by Hieff Clone Zero TOPO-TA Cloning Kit (10907ES) and genotypes of clones were sequenced by Sango Biotech.

5. Conclusions

In this study, in vitro maturation sheep oocytes were used for zygote editing via microinjection and the in vitro maturation efficiency of oocytes is influenced by environmental factors. An optimized microinjection system was developed and highly editing efficiency of target genes were detected in oocytes and sheep.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Figure S1: Seasonal variations in climate of Beijing; Figure S2: Editing efficiency in oocytes post-microinjection based on fluorescent intensity; Figure S3: Genotype analysis of edited oocytes using Cas9 protein or mRNA; Table S1: Spearman's rank correlation coefficient of climate parameter in seasons; Table S2: sg sequences targeted to genes in this study; Table S3: primers of targeting genes in this study; Table S4: Editing efficiency of different target gene by using of Cas9 protein or mRNA; Table S5: Commercial recombinant CRISPR/Cas proteins.

Author Contributions

Author Contributions: writing—original draft preparation, validation, investigation, data curation, H. W. and H.Y.; investigation, formal analysis, T. L. and Y. C.; validation, investigation, J. C. and N. Z.; resources, methodology, investigation, X. Z. and J. Z.; software, validation Y. Z.; supervision, writing—review and editing, R. M.; project administration, funding acquisition X. H.; conceptualization, project administration, funding acquisition, writing—review and editing Q. L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. XDA24030205, XDA26040303), Biological Breeding- National Science and Technology Major Project (2023ZD0406805, 2023ZD0407106) and Open Project of Tianjin Key Laboratory of Animal Molecular Breeding and Biotechnology (XM202402).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Advisory Committee at the Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. All experiments were conducted according to the guidelines of the proposal (approval No. AP2022014; Approval Date: 2022-03-09), in strict adherence to China’s regulatory framework for experimental animals.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate Limin Wang from Xinjiang Academy of Agricultural and Reclamation Science for providing method of microinjection and Jianlin Han from Yazhouwan National Laboratory for providing sheep ovaries. We also appreciate Miss Yingying Zhu from Xinjiang Academy of Agricultural and Reclamation Science for microinjection and Master Zhonghui Ma from Beijing Fangshan District Center for Disease Control and Prevention for analyzing the meteorological data. We also thank Gansu Qinghuan Sheep Breeder Co., LTD for guiding zygotes transfer.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cong, L.; Ran, F.A.; Cox, D.; Lin, S.; Barretto, R.; Habib, N.; Hsu, P.D.; Wu, X.; Jiang, W.; Marraffini, L.A.; et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science 2013, 339, 819–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jinek, M.; Chylinski, K.; Fonfara, I.; Hauer, M.; Doudna, J.A.; Charpentier, E. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 2012, 337, 816–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonin, E.V.; Makarova, K.S.; Zhang, F. Diversity, classification and evolution of CRISPR-Cas systems. Curr Opin Microbiol 2017, 37, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbar, A.; Zulfiqar, F.; Mahnoor, M.; Mushtaq, N.; Zaman, M.H.; Din, A.S.U.; Khan, M.A.; Ahmad, H.I. Advances and Perspectives in the Application of CRISPR-Cas9 in Livestock. Mol Biotechnol 2021, 63, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menchaca, A.; Dos Santos-Neto, P.C.; Mulet, A.P.; Crispo, M. CRISPR in livestock: From editing to printing. Theriogenology 2020, 150, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Li, P.; Yin, Y.; Du, X.; Cao, G.; Wu, S.; Zhao, Y. Molecular breeding of livestock for disease resistance. Virology 2023, 587, 109862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnley, A.M. Role of SOCS2 in growth hormone actions. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2005, 16, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Cai, B.; He, C.; Wang, Y.; Ding, Q.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Ding, Y.; Zhao, X.; Li, G.; et al. Programmable Base Editing of the Sheep Genome Revealed No Genome-Wide Off-Target Mutations. Front Genet 2019, 10, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dukkipati, V.S.; Blair, H.T.; Garrick, D.J.; Murray, A. 'Ovar-Mhc' - ovine major histocompatibility complex: structure and gene polymorphisms. Genet Mol Res 2006, 5, 581–608. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-de Gives, P.; López-Arellano, M.E.; Olmedo-Juárez, A.; Higuera-Pierdrahita, R.I.; von Son-de Fernex, E. Recent Advances in the Control of Endoparasites in Ruminants from a Sustainable Perspective. Pathogens 2023, 12, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; He, S.G.; Li, W.R.; Luo, L.Y.; Yan, Z.; Mo, D.X.; Wan, X.; Lv, F.H.; Yang, J.; Xu, Y.X.; et al. Genomic analyses of wild argali, domestic sheep, and their hybrids provide insights into chromosome evolution, phenotypic variation, and germplasm innovation. Genome Res 2022, 32, 1669–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, B.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, G.; Zhang, X.; Bai, J.; Brosh, R.; Wudzinska, A.; Huang, E.; Ashe, H.; Ellis, G.; et al. On the genetic basis of tail-loss evolution in humans and apes. Nature 2024, 626, 1042–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Weng, Y.; Bai, D.; Jia, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Kou, X.; Zhao, Y.; Ruan, J.; Chen, J.; et al. Precise allele-specific genome editing by spatiotemporal control of CRISPR-Cas9 via pronuclear transplantation. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 4593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Ma, Y.; Wang, T.; Lian, L.; Tian, X.; Rui, H.; Deng, S.; Li, K.; Wang, F.; Li, N.; et al. One-step generation of myostatin gene knockout sheep via the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Front Agr Sci & Eng 2014, 1, 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Niu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Yu, H.; Kou, Q.; Lei, A.; Zhao, X.; Yan, H.; Cai, B.; Shen, Q.; et al. Multiplex gene editing via CRISPR/Cas9 exhibits desirable muscle hypertrophy without detectable off-target effects in sheep. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 32271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, R.; Fan, Z.Y.; Wang, B.Y.; Deng, S.L.; Zhang, X.S.; Zhang, J.L.; Han, H.B.; Lian, Z.X. RAPID COMMUNICATION: Generation of FGF5 knockout sheep via the CRISPR/Cas9 system. J Anim Sci 2017, 95, 2019–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Li, W.; Liu, C.; Peng, X.; Lin, J.; He, S.; Li, X.; Han, B.; Zhang, N.; Wu, Y.; et al. Alteration of sheep coat color pattern by disruption of ASIP gene via CRISPR Cas9. Sci Rep 2016, 7, 8149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Yu, H.; Zhao, X.; Cai, B.; Ding, Q.; Huang, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Niu, Y.; Lei, A.; et al. Generation of gene-edited sheep with a defined Booroola fecundity gene (FecBB) mutation in bone morphogenetic protein receptor type 1B (BMPR1B) via clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated (Cas) 9. Reprod Fertil Dev 2018, 30, 1616–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Cai, B.; He, C.; Wang, Y.; Ding, Q.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Ding, Y.; Zhao, X.; Li, G.; et al. Programmable Base Editing of the Sheep Genome Revealed No Genome-Wide Off-Target Mutations. Front Genet 2019, 10, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Ding, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Li, G.; Zhang, C.; Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Kalds, P.; et al. Highly efficient generation of sheep with a defined FecBB mutation via adenine base editing. Genet Sel Evol 2020, 52, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Kalds, P.; Luo, Q.; Sun, K.; Zhao, X.; Gao, Y.; Cai, B.; Huang, S.; Kou, Q.; Petersen, B.; et al. Optimized Cas9: sgRNA delivery efficiently generates biallelic MSTN knockout sheep without affecting meat quality. BMC genomics 2022, 23, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; He, S.G.; Li, W.R.; Luo, L.Y.; Yan, Z.; Mo, D.X.; Wan, X.; Lv, F.H.; Yang, J.; Xu, Y.X.; et al. Genomic analyses of wild argali, domestic sheep, and their hybrids provide insights into chromosome evolution, phenotypic variation, and germplasm innovation. Genome Res 2022, 32, 1669–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Lenk, L.J.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Pan, M.; Huang, S.; Sun, K.; Kalds, P.; Luo, Q.; et al. Generation of sheep with defined FecBB and TBXT mutations and porcine blastocysts with KCNJ5G151R/+ mutation using prime editing. BMC genomics 2023, 24, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Wang, H.; Meng, C.; Gui, H.; Li, Y.; Chen, F.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, H.; Ding, Q.; Zhang, J.; et al. Efficient and Specific Generation of MSTN-Edited Hu Sheep Using C-CRISPR. Genes 2023, 14, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.M.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, K.; Xu, X.L.; Zhang, X.S.; Zhang, J.L.; Wu, S.J.; Liu, Z.M.; Yuan, Y.M.; Guo, X.F.; et al. A MSTNDel73C mutation with FGF5 knockout sheep by CRISPR/Cas9 promotes skeletal muscle myofiber hyperplasia. eLife 2024, 12, RP86827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Shen, J.; Li, D.; Cheng, Y. Strategies in the delivery of Cas9 ribonucleoprotein for CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing. Theranostics 2021, 11, 614–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paffoni, A.; Brevini, T.A.; Somigliana, E.; Restelli, L.; Gandolfi, F.; Ragni, G. In vitro development of human oocytes after parthenogenetic activation or intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Fertil Steril 2007, 87, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, J.C.B.; Alves, M.B.R.; Bridi, A.; Bohrer, R.C.; Escobar, G.S.L.; de Carvalho, J.A.B.A.; Binotti, W.A.B.; Pugliesi, G.; Lemes, K.M.; Chello, D.; et al. Reproductive seasonality influences oocyte retrieval and embryonic competence but not uterine receptivity in buffaloes. Theriogenology 2021, 170, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorca, T.; Cruzalegui, F.H.; Fesquet, D.; Cavadore, J.C.; Méry, J.; Means, A.; Dorée, M. Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II mediates inactivation of MPF and CSF upon fertilization of Xenopus eggs. Nature 1993, 366, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

IVM rates of sheep oocytes. (a) IVM rates of oocytes with increased hormone concentration and serum EOS (Before: n=46; After: n=30); (b) Proportion of available oocytes with increased hormone concentration and serum EOS (Before: n=5; After: n=5); (c) IV rate of oocytes varied different months (Jan: n=9; Feb: n=5; Mar: n=9; Apr: n = 9; May: n = 9; June: n = 5; July: n = 5; Aug: n = 6; Sep: n = 11; Oct: n = 11; Nov: n = 4; Dec: n = 8); (d) IVM rate of oocytes varied with different seasons (Spring: n = 27; Summer: n = 16; Autumn: n = 26; Winter: n = 22); (e) Forest plot of air temperature on the maturation rate of oocytes in different seasons; (f) Forest plot of sunlight duration on the maturation rate of oocytes in different seasons; (g) Forest plot of atmospheric pressure on the maturation rate of oocytes in different seasons; (h) Forest plot of relative humidity on the maturation rate of oocytes in different seasons. All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001.

Figure 1.

IVM rates of sheep oocytes. (a) IVM rates of oocytes with increased hormone concentration and serum EOS (Before: n=46; After: n=30); (b) Proportion of available oocytes with increased hormone concentration and serum EOS (Before: n=5; After: n=5); (c) IV rate of oocytes varied different months (Jan: n=9; Feb: n=5; Mar: n=9; Apr: n = 9; May: n = 9; June: n = 5; July: n = 5; Aug: n = 6; Sep: n = 11; Oct: n = 11; Nov: n = 4; Dec: n = 8); (d) IVM rate of oocytes varied with different seasons (Spring: n = 27; Summer: n = 16; Autumn: n = 26; Winter: n = 22); (e) Forest plot of air temperature on the maturation rate of oocytes in different seasons; (f) Forest plot of sunlight duration on the maturation rate of oocytes in different seasons; (g) Forest plot of atmospheric pressure on the maturation rate of oocytes in different seasons; (h) Forest plot of relative humidity on the maturation rate of oocytes in different seasons. All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001.

Figure 2.

Reduced mortality with horizontal injection by optimized capillary. (a) Commercial microinjection capillary with a diameter of 0.5 μm, stabbing into the oocyte slantly; (b) optimized microinjection capillary with a diameter of 0.25μm, stabbing into the oocyte horizontally; (c) reduced mortality by using different injection capillaries. All data are presented as the mean±SD. Before: n=8; After: n=10. *** P<0.001.

Figure 2.

Reduced mortality with horizontal injection by optimized capillary. (a) Commercial microinjection capillary with a diameter of 0.5 μm, stabbing into the oocyte slantly; (b) optimized microinjection capillary with a diameter of 0.25μm, stabbing into the oocyte horizontally; (c) reduced mortality by using different injection capillaries. All data are presented as the mean±SD. Before: n=8; After: n=10. *** P<0.001.

Figure 3.

Gene editing efficiency under different concentrations of injection mixture. (a) Editing efficiency at different injection concentrations, n=3. (b) death rate of oocytes at different injection concentrations. n=3. (c) Cleavage rate at different injection concentrations, n=3. (d) Editing efficiency at different fluorescence intensities, Higher: n=3, lower, n=3. (e) Cleavage rate at different fluorescence intensities. Higher: n = 3; lower: n = 3. All data are presented as the mean±SD. * P<0.05, ** P<0.01.

Figure 3.

Gene editing efficiency under different concentrations of injection mixture. (a) Editing efficiency at different injection concentrations, n=3. (b) death rate of oocytes at different injection concentrations. n=3. (c) Cleavage rate at different injection concentrations, n=3. (d) Editing efficiency at different fluorescence intensities, Higher: n=3, lower, n=3. (e) Cleavage rate at different fluorescence intensities. Higher: n = 3; lower: n = 3. All data are presented as the mean±SD. * P<0.05, ** P<0.01.

Figure 4.

Effect of using Cas9 mRNA and protein on gene editing results. (a) Gene editing efficiency for SOCS2; (b) Homozygous editing efficiency for SOCS2; (c) Gene editing efficiency for TBXT; (d) Homozygous editing efficiency for TBXT. All data are presented as the mean±SD. n = 3. * P<0.05.

Figure 4.

Effect of using Cas9 mRNA and protein on gene editing results. (a) Gene editing efficiency for SOCS2; (b) Homozygous editing efficiency for SOCS2; (c) Gene editing efficiency for TBXT; (d) Homozygous editing efficiency for TBXT. All data are presented as the mean±SD. n = 3. * P<0.05.

Figure 5.

SOCS2 editing efficiency before and after parthenogenetic activation. (a) Gene editing efficiency before and after parthenogenesis activation; (b) Cleavage rate before and after parthenogenesis activation. Before: Injected before parthenogenetic activation, after: Injected after parthenogenetic activation. All data are presented as the mean±SD, n=3.

Figure 5.

SOCS2 editing efficiency before and after parthenogenetic activation. (a) Gene editing efficiency before and after parthenogenesis activation; (b) Cleavage rate before and after parthenogenesis activation. Before: Injected before parthenogenetic activation, after: Injected after parthenogenetic activation. All data are presented as the mean±SD, n=3.

Figure 6.

Effect of microinjection on embryo development. (a) 48h cleavage rate injected and non-injected embryos; (b) Blastocyst rate of injected and non-injected embryos; (c) Immunofluorescence of pluripotent gene in injected embryos; (d) Immunofluorescence of Cas9 protein in injected embryos. All data are presented as the mean±SD. * P<0.05.

Figure 6.

Effect of microinjection on embryo development. (a) 48h cleavage rate injected and non-injected embryos; (b) Blastocyst rate of injected and non-injected embryos; (c) Immunofluorescence of pluripotent gene in injected embryos; (d) Immunofluorescence of Cas9 protein in injected embryos. All data are presented as the mean±SD. * P<0.05.

Figure 7.

Genotype of SOCS2 and DYA edited sheep. (a) Genotype of SOCS2 edited sheep by TA cloning and Sanger sequence; (b) Genotype of DYA edited sheep by TA cloning and Sanger sequence. Number of colonies with the genotype were showed in brackets.

Figure 7.

Genotype of SOCS2 and DYA edited sheep. (a) Genotype of SOCS2 edited sheep by TA cloning and Sanger sequence; (b) Genotype of DYA edited sheep by TA cloning and Sanger sequence. Number of colonies with the genotype were showed in brackets.

Table 1.

generation of gene edited sheep by optimized editing system.

Table 1.

generation of gene edited sheep by optimized editing system.

| Target gene |

|

Zygotes |

Transplanted Zygotes |

Recipient |

Pregnant recipients |

Delivered Lambs |

Edited lambs |

Editing efficiency |

| SOCS2 |

|

58 |

47 |

7 |

5 |

6 |

6 |

100% |

| DYA |

|

135 |

90 |

15 |

4 |

5 |

5 |

100% |

Table 2.

efficiency of gene editing by microinjection of sheep zygotes in previous studies.

Table 2.

efficiency of gene editing by microinjection of sheep zygotes in previous studies.

| Target gene |

Transplanted zygotes |

Pregnant recipients /Recipients |

Edited lambs /Delivered Lambs |

Editing efficiency (%) |

Editing tools |

| MSTN[14] |

213 |

31/55 |

2/35 |

5.7 |

Cas9 |

| MSTN, ASIP and BCO2[15] |

578 |

77/82 |

35/36 |

97.2 |

Cas9 |

| FGF5[16] |

100 |

14/53 |

3/18 |

16.7 |

Cas9 |

| ASIP[17] |

92 |

6/60 |

5/6 |

83.3 |

Cas9 |

| BMPR1B[18] |

279 |

16/39 |

7/21 |

33.3 |

Cas9 |

| SOCS2[19] |

53 |

3/8 |

3/4 |

75 |

CBE (Cytosine base editor) |

| FecB[20] |

95 |

6/18 |

6/8 |

75 |

ABE (adenine base editing) |

| MSTN[21] |

345 |

14/58 |

8/16 |

50 |

Cas9 |

| TBXT[22] |

338 |

31/216 |

19/28 |

67.9 |

Cas9&ssODN |

| FecBB [23] |

122 |

15/45 |

5/7 |

71.4 |

PE (prime editing) |

| TBXT[23] |

140 |

3/8 |

37.5 |

| MSTN[24] |

70 |

5/13 |

9/10 |

90 |

Cas9 |

| MSTN/FGF5[25] |

1201 |

78/236 |

12/64 |

18.8 |

Cas9 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).