Submitted:

09 December 2024

Posted:

10 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

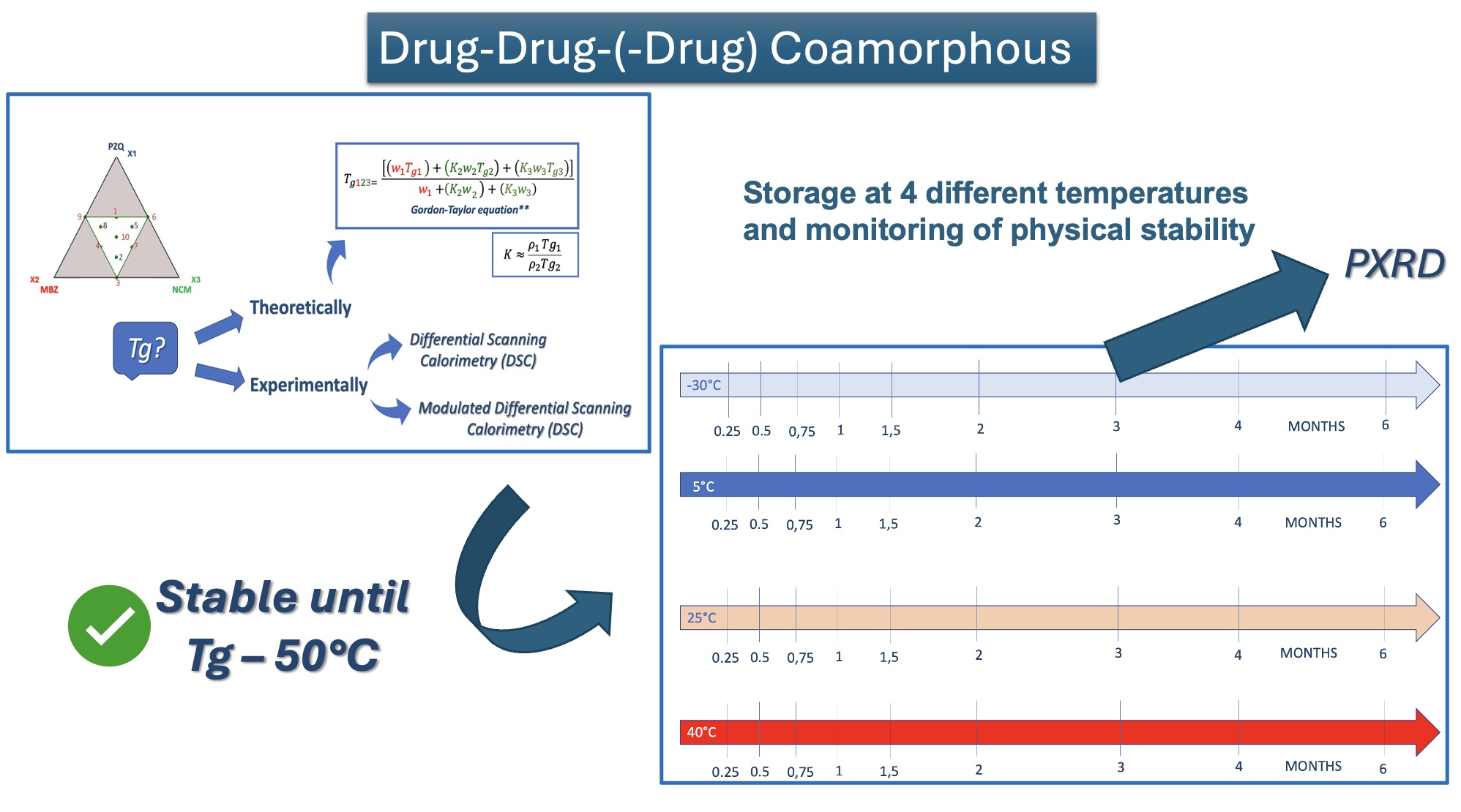

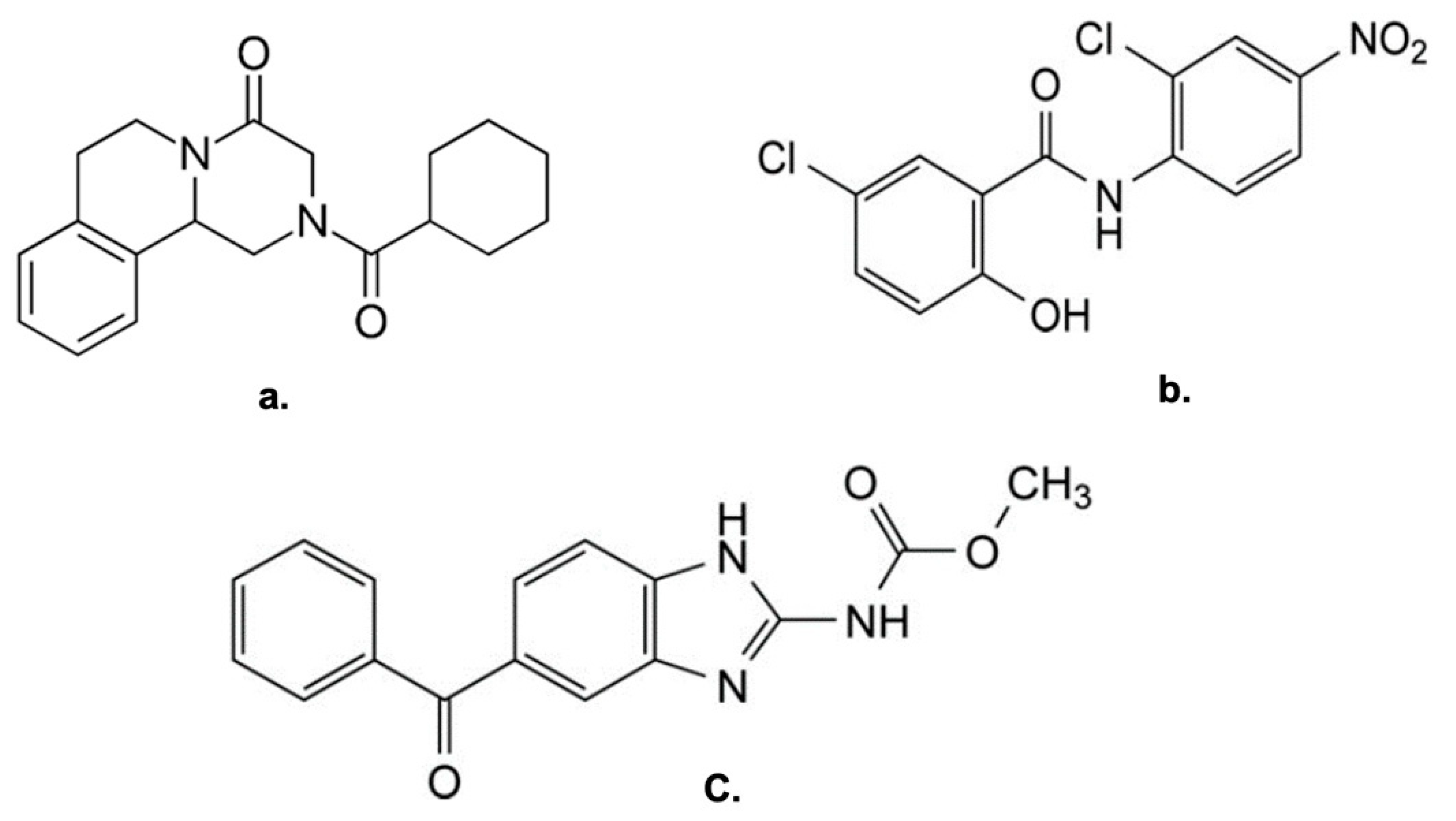

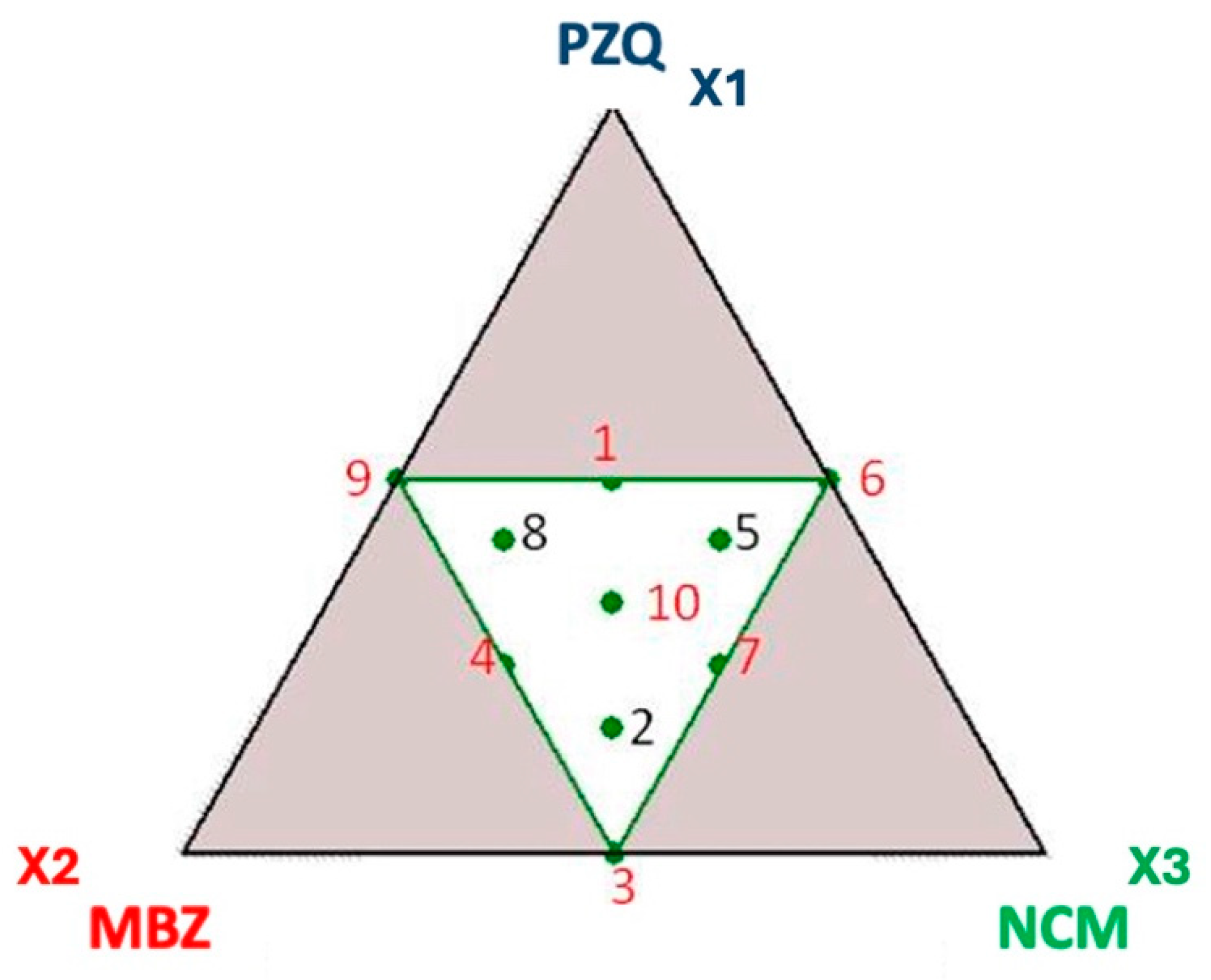

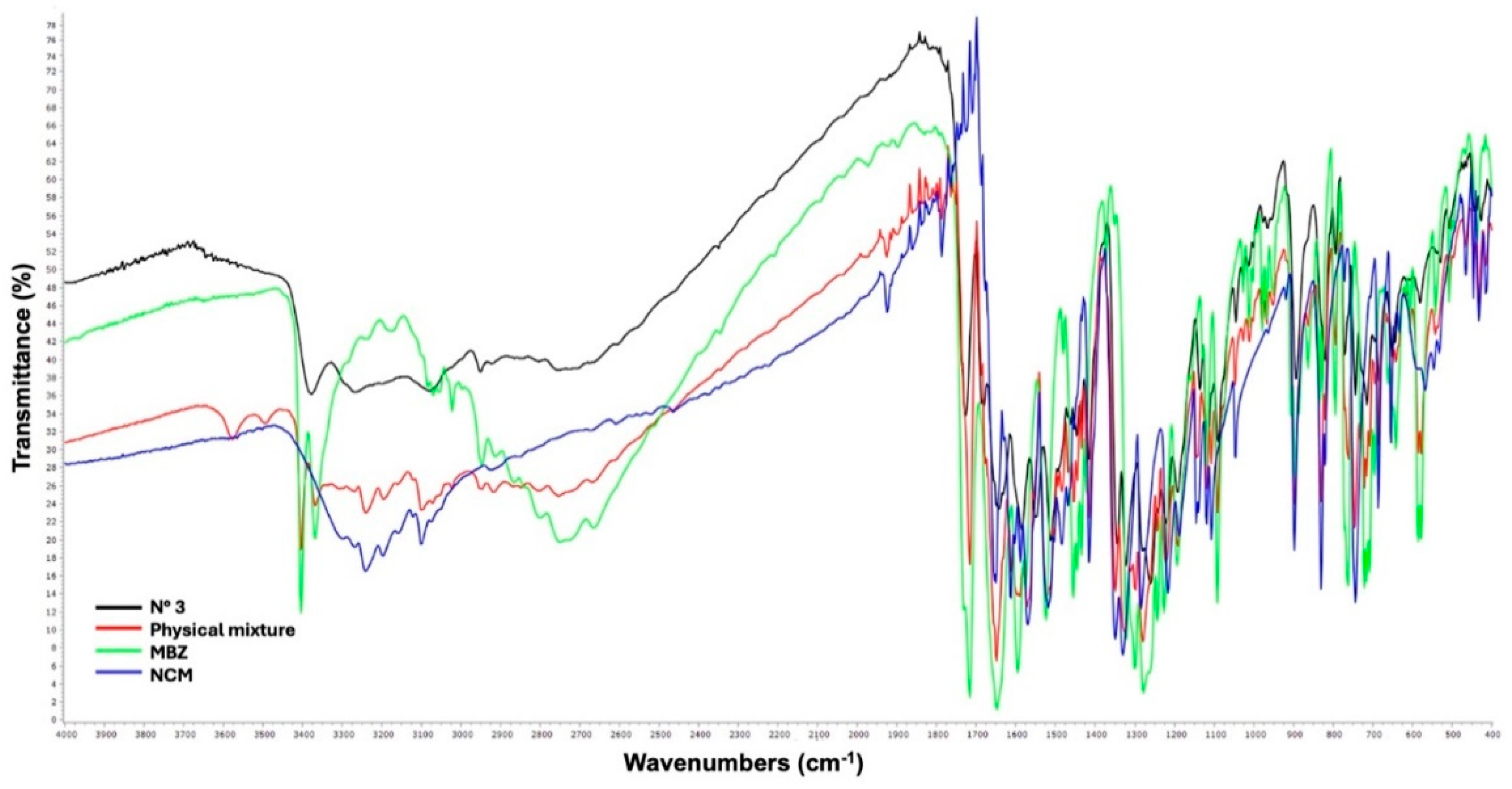

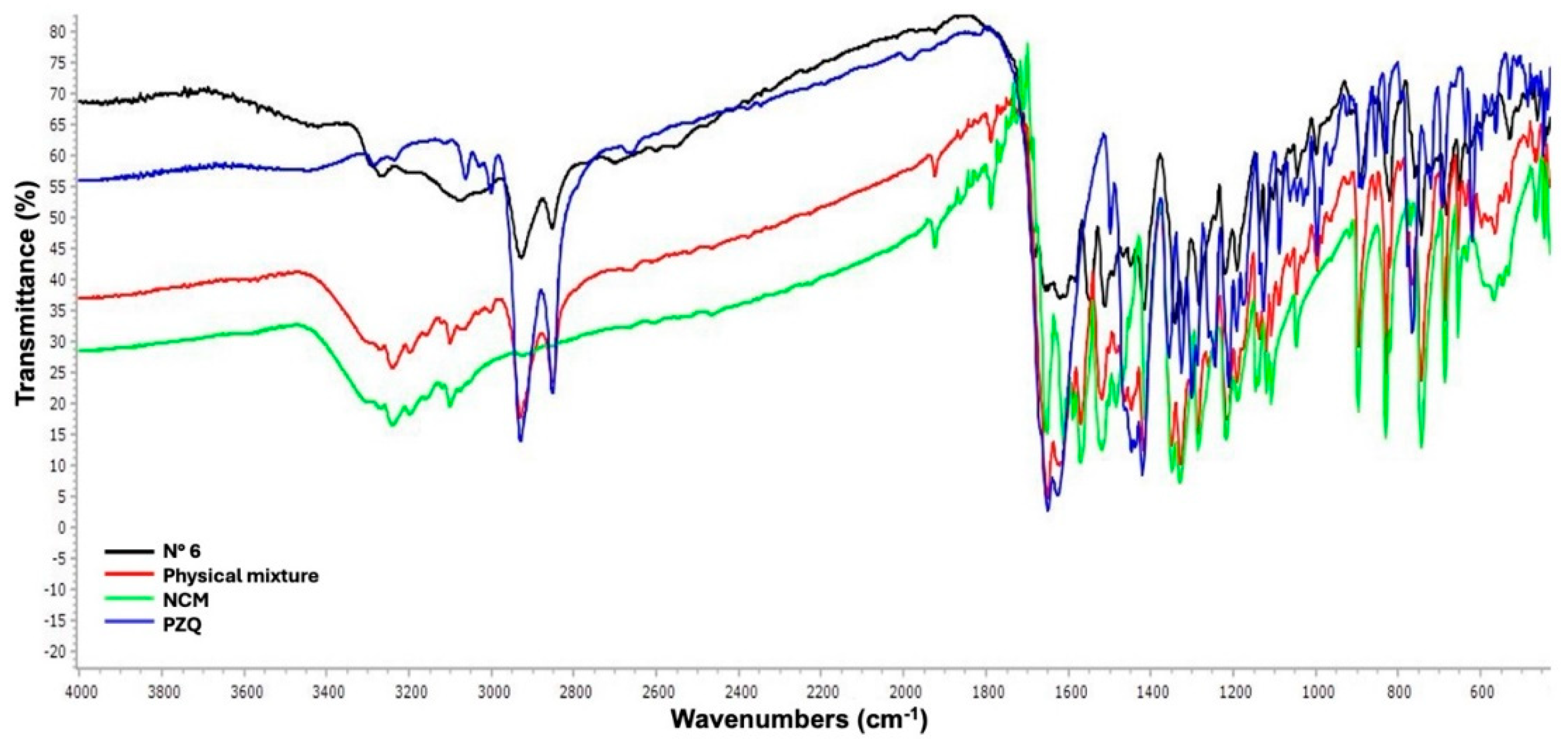

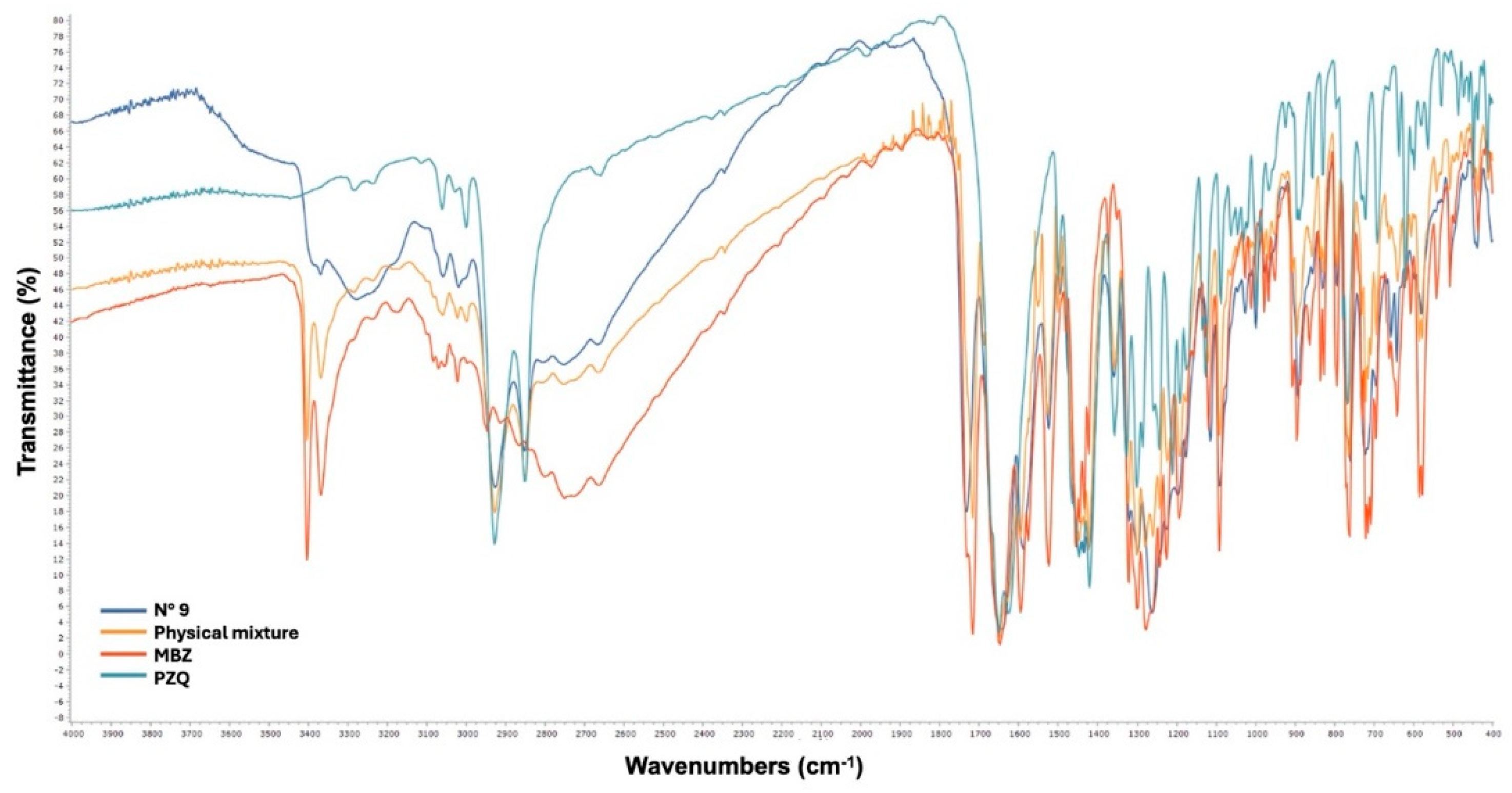

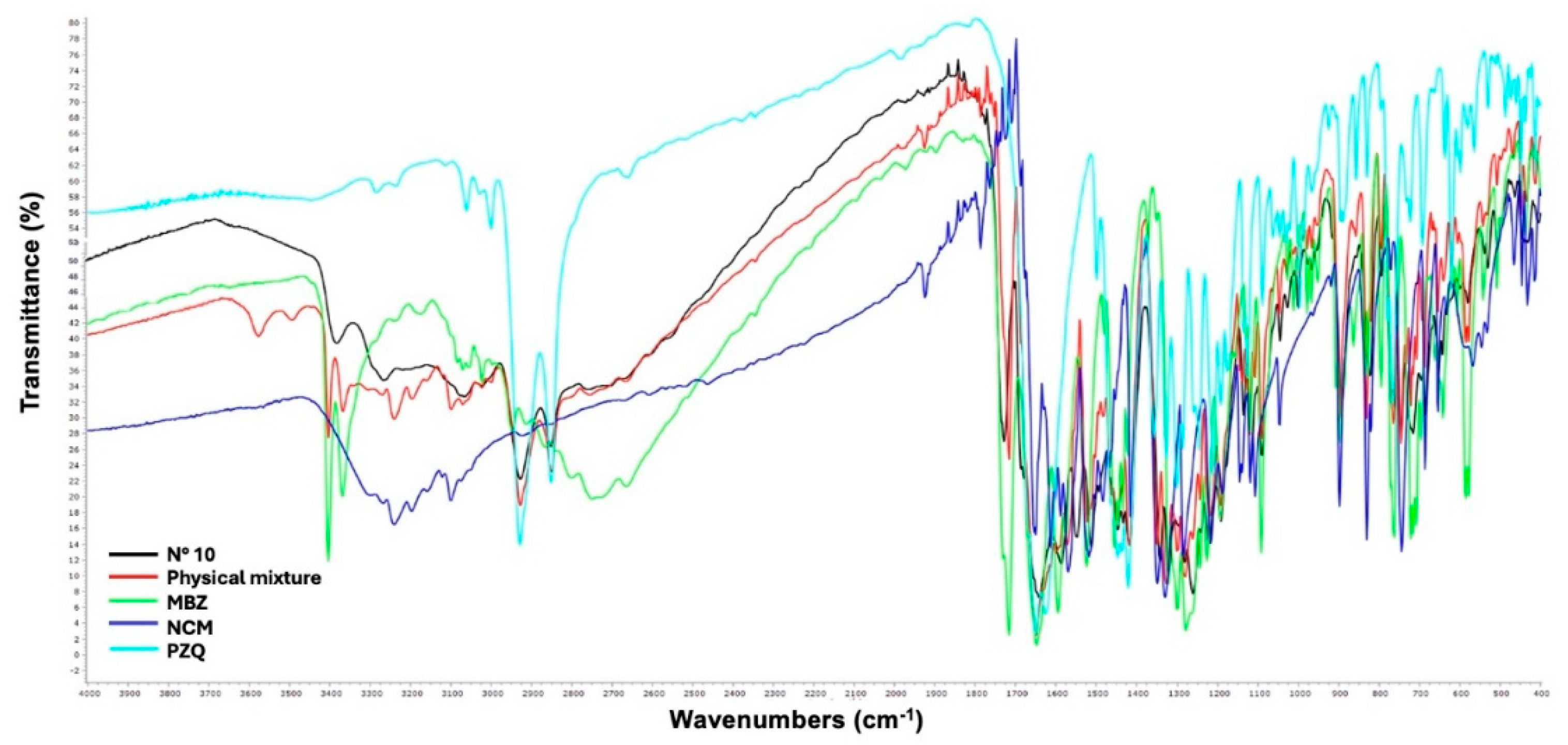

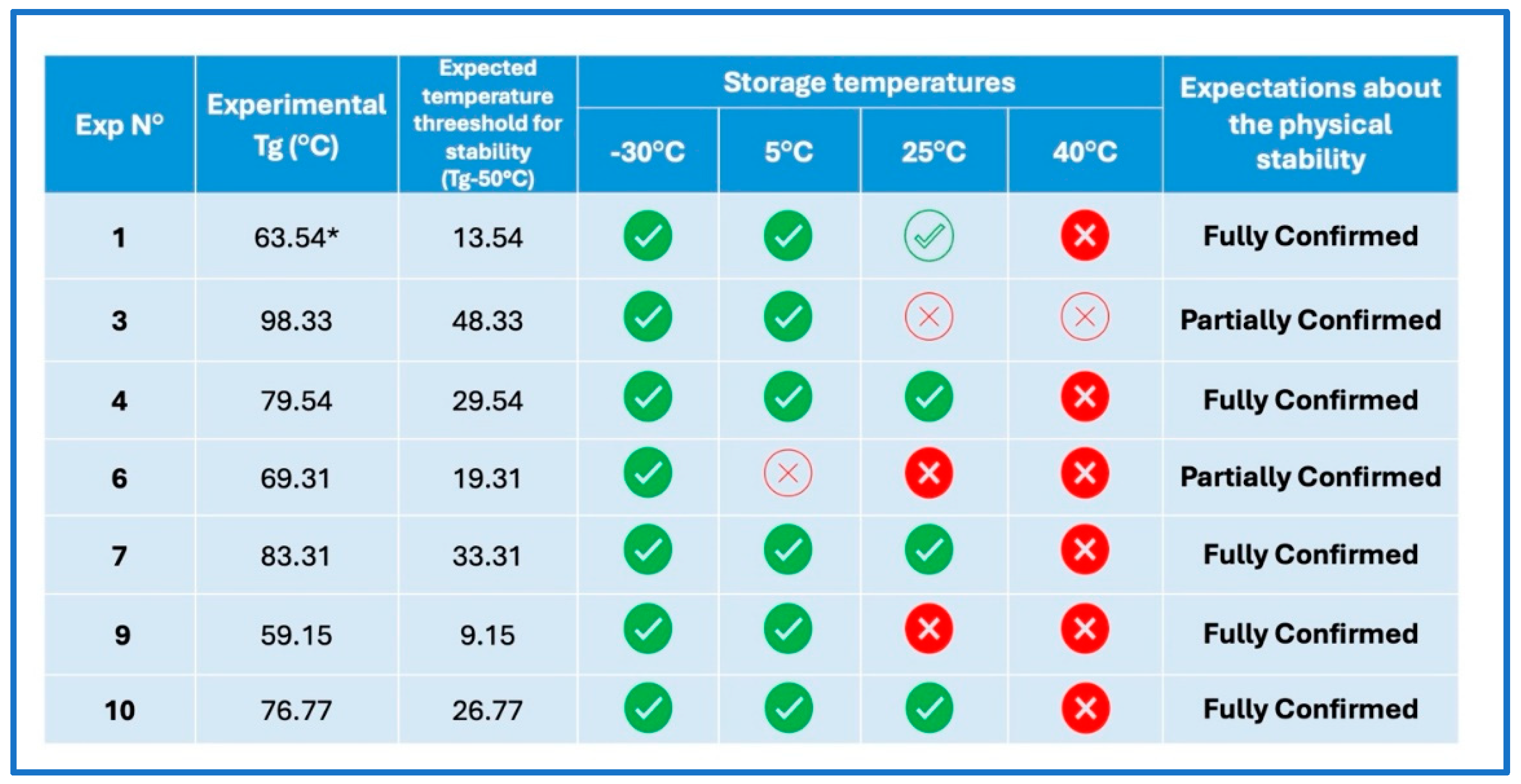

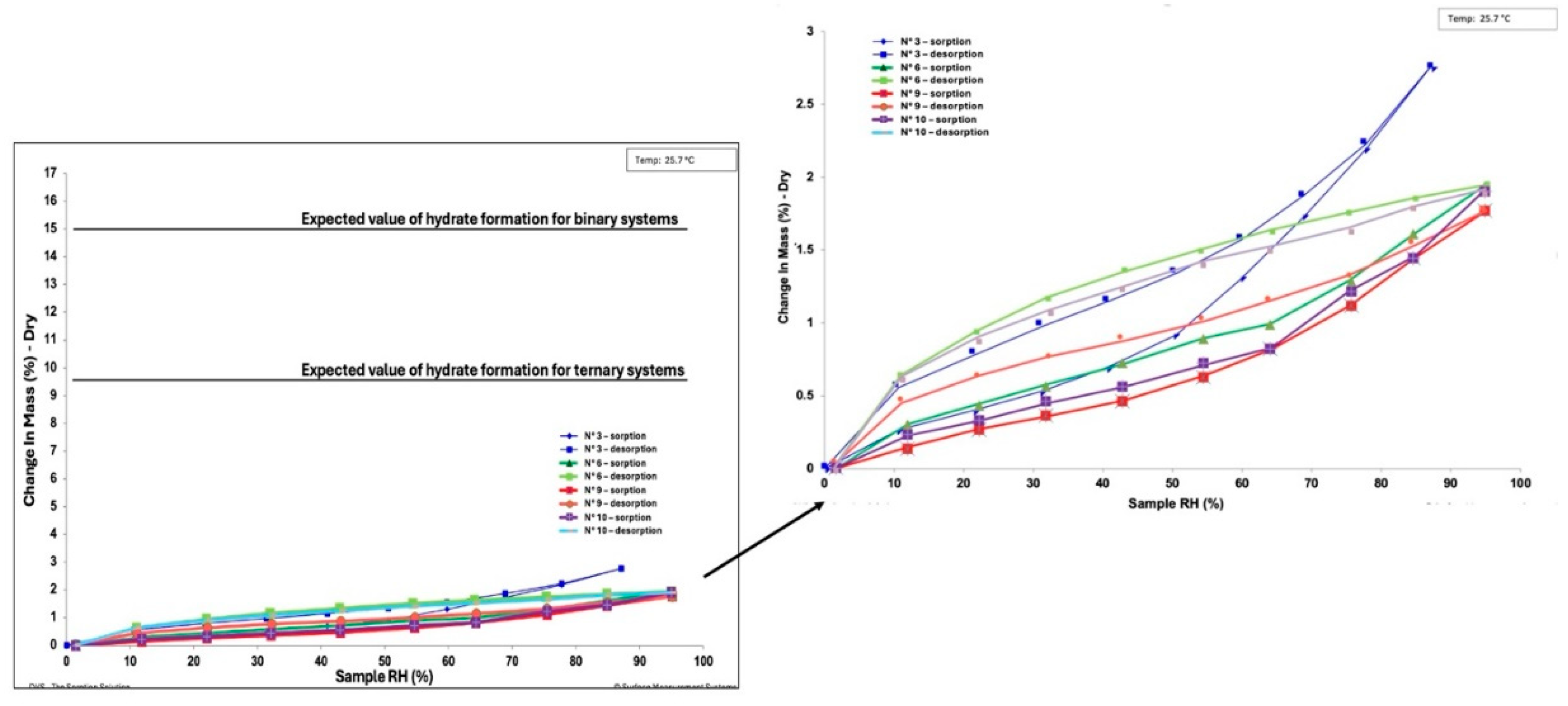

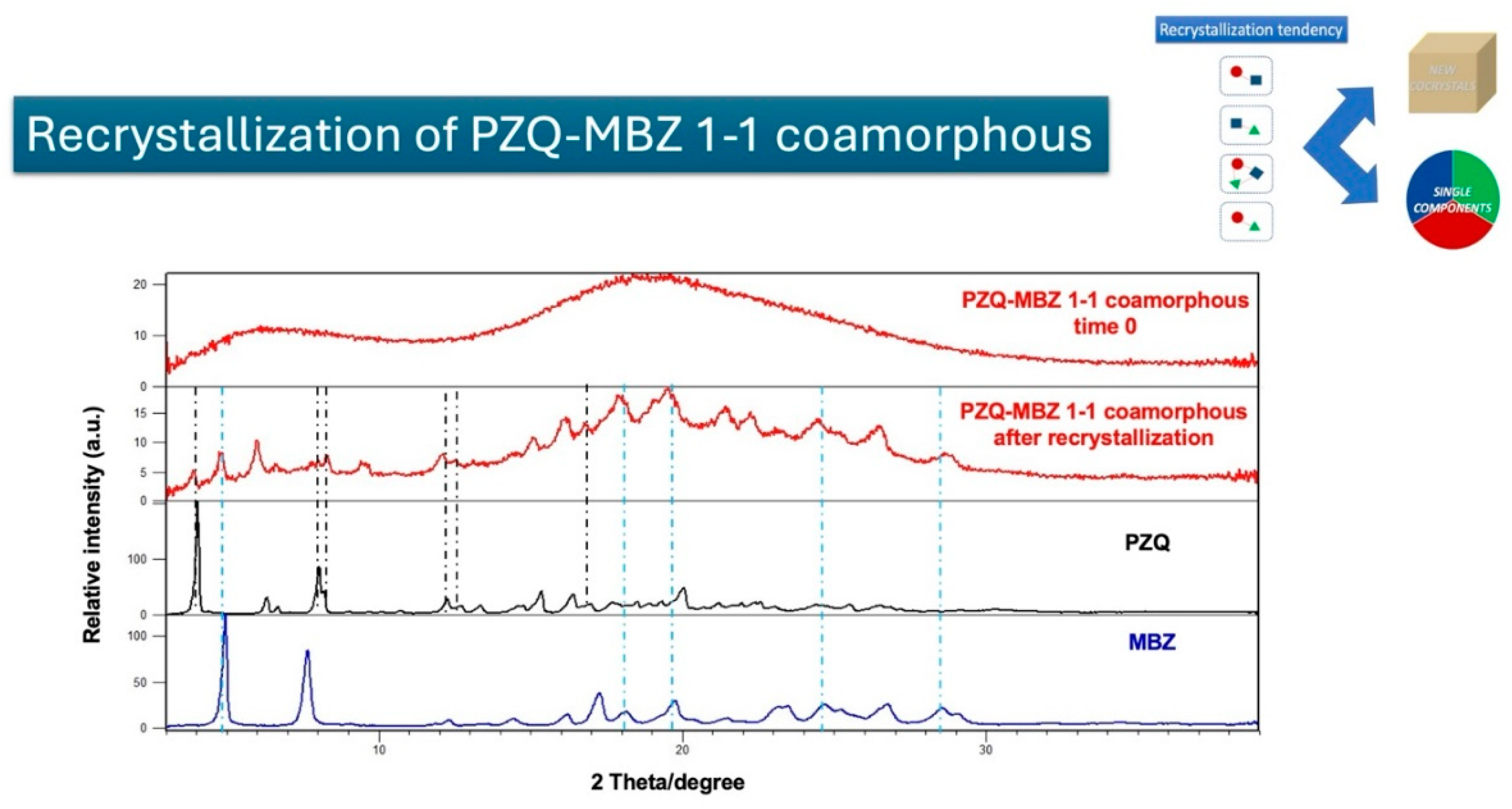

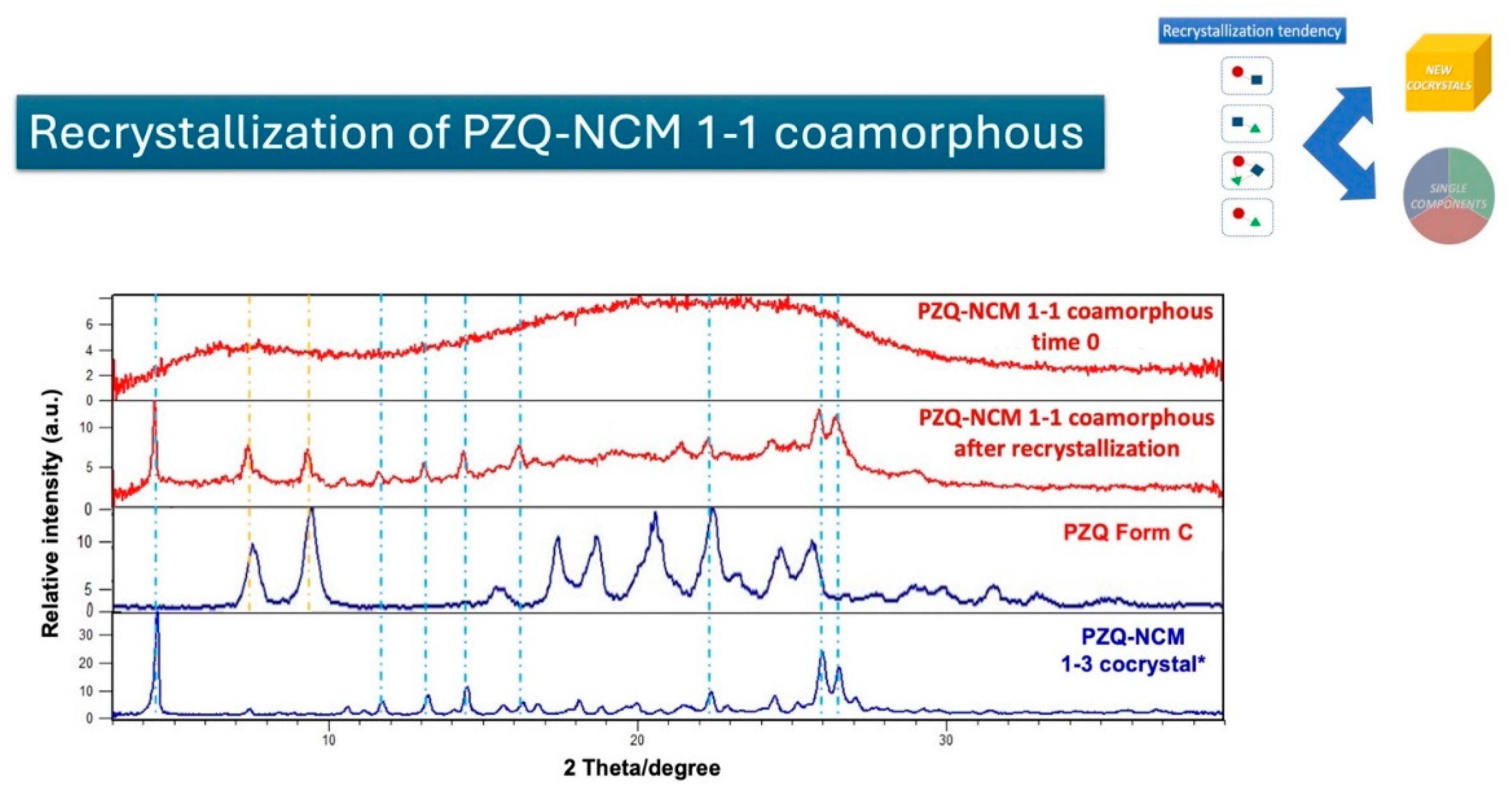

This study explores the successful preparation of coamorphous systems composed entirely of ac-tive pharmaceutical ingredients, namely praziquantel, niclosamide, and mebendazole. Using a mixture design approach, ten different (binary and ternary) mixtures were formulated and pre-pared by neat grinding in a lab-scale vibrational mill. The solvent-free one-step process was re-producible, requiring only 4 hours to generate the coamorphous systems in the whole experi-mental domain. Structural analysis by PXRD and FTIR confirmed the absence of crystalline do-mains and presence of molecular interactions. The glass transition (Tg) temperature was calcu-lated theoretically according to Gordon-Taylor equation for a three-component system and then determined by DSC. In most cases a single Tg was seen, indicating the formation of homogene-ous multicomponent systems. Stability studies on seven systems, stored for six months under different temperature conditions (-30 °C, 5 °C, 25 °C, and 40 °C), demonstrated that all systems were physically stable according to the "Tg – 50 °C" stability rule, with only two exceptions out of seven. Humidity effects were minimal, as shown by DVS data, which revealed only superfi-cial water sorption and no recrystallization. Additionally, the investigation of recrystallization pathways revealed that, depending on the system's interactions, some coamorphous systems separated into their original crystalline phases and others formed new entities such cocrystals.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Samples Preparation

Mixture Composition and Experimental Design

Neat Grinding (NG) Experiments

Physical Mixtures Preparation

2.2.2. Samples Characterization

Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD)

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

True Density Determinations

- pedix 1, 2 and 3 refer to PZQ, NCM and MBZ, respectively.

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

Stability Studies

Drug Recovery

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Babu, N.J.; Nangia, A. Solubility Advantage of Amorphous Drugs and Pharmaceutical Cocrystals. Cryst Growth Des 2011, 11, 2662–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Moinuddin, S.M.; Cai, T. Advances in Coamorphous Drug Delivery Systems. Acta Pharm Sin B 2019, 9, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Knipp, G.; Zografi, G. Assessing the Performance of Amorphous Solid Dispersions. J Pharm Sci 2012, 101, 1355–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitinen, R.; Löbmann, K.; Strachan, C.J.; Grohganz, H.; Rades, T. Emerging Trends in the Stabilization of Amorphous Drugs. Int J Pharm 2013, 453, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminska, E.; Adrjanowicz, K.; Zakowiecki, D.; Milanowski, B.; Tarnacka, M.; Hawelek, L.; Dulski, M.; Pilch, J.; Smolka, W.; Kaczmarczyk-Sedlak, I.; et al. Enhancement of the Physical Stability of Amorphous Indomethacin by Mixing It with Octaacetylmaltose. Inter and Intra Molecular Studies. Pharm Res 2014, 31, 2887–2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Duggirala, N.K.; Kumar, N.S.K.; Su, Y.; Suryanarayanan, R. Design of Ternary Amorphous Solid Dispersions for Enhanced Dissolution of Drug Combinations. Mol Pharm 2022, 19, 2950–2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chieng, N.; Aaltonen, J.; Saville, D.; Rades, T. Physical Characterization and Stability of Amorphous Indomethacin and Ranitidine Hydrochloride Binary Systems Prepared by Mechanical Activation. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2009, 71, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, W.; Song, Y.; Luo, M.; Hu, E.; Wei, Y.; Gao, Y.; Pang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Qian, S. Mechanistic Insights into the Crystallization of Coamorphous Drug Systems. J. Control. Release 2023, 354, 489–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodagekar, A.; Chavan, R.B.; Mannava, M.K.C.; Yadav, B.; Chella, N.; Nangia, A.K.; Shastri, N.R. Co Amorphous Valsartan Nifedipine System: Preparation, Characterization, in Vitro and in Vivo Evaluation. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 139, 105048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Huang, Q.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Yin, L.; Zhao, Y.; Liang, G.; Wu, W. Dissolution Changes in Drug-Amino Acid/Biotin Co-Amorphous Systems: Decreased/Increased Dissolution during Storage without Recrystallization. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 188, 106526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’angelo, A.; Edgar, B.; Hurt, A.P.; Antonijević, M.D. Physico-Chemical Characterisation of Three-Component Co-Amorphous Systems Generated by a Melt-Quench Method. J Therm Anal Calorim 2018, 134, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narala, S.; Nyavanandi, D.; Srinivasan, P.; Mandati, P.; Bandari, S.; Repka, M.A. Pharmaceutical Co-Crystals, Salts, and Co-Amorphous Systems: A Novel Opportunity of Hot-Melt Extrusion. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 2021, 61, 102209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitinen, R.; Priemel, P.A.; Surwase, S.; Graeser, K.; Strachan, C.J.; Grohganz, H.; Rades, T. Theoretical Considerations in Developing Amorphous Solid Dispersions. In; 2014; 35–90. [Google Scholar]

- Chavan, R.B.; Thipparaboina, R.; Kumar, D.; Shastri, N.R. Co Amorphous Systems: A Product Development Perspective. Int J Pharm 2016, 515, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L. Amorphous Pharmaceutical Solids: Preparation, Characterization and Stabilization. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2001, 48, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.F.C.; Rosado, M.T.S.; Maria, T.M.R.; Pereira Silva, P.S.; Silva, M.R.; Eusébio, M.E.S. Introduction to Pharmaceutical Co-Amorphous Systems Using a Green Co-Milling Technique. J Chem Educ 2023, 100, 1627–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, P.F.M.; Willart, J.-F.; Siepmann, J.; Siepmann, F.; Descamps, M. Using Milling To Explore Physical States: The Amorphous and Polymorphic Forms of Dexamethasone. Cryst Growth Des 2018, 18, 1748–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasa, D.; Jones, W. Screening for New Pharmaceutical Solid Forms Using Mechanochemistry: A Practical Guide. 2017, 117,147–161. [CrossRef]

- PRALEN Gocce per Gatti, Cani Cuccioli e Di Piccola Taglia | UPD. Available online: https://medicines.health.europa.eu/veterinary/it/600000094039 (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- Lindenberg, M.; Kopp, S.; Dressman, J.B. Classification of Orally Administered Drugs on the World Health Organization Model List of Essential Medicines According to the Biopharmaceutics Classification System. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2004, 58, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groom, C.R.; Bruno, I.J.; Lightfoot, M.P.; Ward, S.C. The Cambridge Structural Database. Acta Crystallogr B Struct Sci Cryst Eng Mater 2016, 72, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perissutti, B.; Passerini, N.; Trastullo, R.; Keiser, J.; Zanolla, D.; Zingone, G.; Voinovich, D.; Albertini, B. An Explorative Analysis of Process and Formulation Variables Affecting Comilling in a Vibrational Mill: The Case of Praziquantel. Int J Pharm 2017, 533, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, E.J.; Andrade, M.A.B.; Gubitoso, M.R.; Bezzon, V.D.N.; Smith, P.A.; Byrn, S.R.; Bou-Chacra, N.A.; Carvalho, F.M.S.; de Araujo, G.L.B. Acoustic Levitation and High-Resolution Synchrotron X-Ray Powder Diffraction: A Fast Screening Approach of Niclosamide Amorphous Solid Dispersions. Int J Pharm 2021, 602, 120611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Abbrunzo, I.; Bianco, E.; Gigli, L.; Demitri, N.; Birolo, R.; Chierotti, M.R.; Škoríc, I.; Keiser, J.; Häberli, C.; Voinovich, D.; et al. Praziquantel Meets Niclosamide: A Dual-Drug Antiparasitic Cocrystal. Int J Pharm 2023, 644, 123315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-M.; Wang, Z.-Z.; Wu, C.-B.; Li, S.; Lu, T.-B. Crystal Engineering Approach to Improve the Solubility of Mebendazole. CrystEngComm 2012, 14, 6221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voinovich, D.; Campisi, B.; Phan-Tan-Luu, R. Experimental Design for Mixture Studies. Comprehensive Chemometrics 2020, 1, 391–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qui Sommes-Nous ? | NemrodW. Available online: https://www.nemrodw.com/fr/whoweare#intro%20(accessed%20on%2030%20August%202024 (accessed on 21 September 2024).

- Zanolla, D.; Perissutti, B.; Passerini, N.; Chierotti, M.R.; Hasa, D.; Voinovich, D.; Gigli, L.; Demitri, N.; Geremia, S.; Keiser, J.; et al. A New Soluble and Bioactive Polymorph of Praziquantel. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2018, 127, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanolla, D.; Perissutti, B.; Vioglio, P.C.; Chierotti, M.R.; Gigli, L.; Demitri, N.; Passerini, N.; Albertini, B.; Franceschinis, E.; Keiser, J.; et al. Exploring Mechanochemical Parameters Using a DoE Approach: Crystal Structure Solution from Synchrotron XRPD and Characterization of a New Praziquantel Polymorph. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, B.J.; Ponichtera, K. Physiology, Boyle’s Law; in: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan. 2022 Oct. 10.

- Hsu, W.-P.; Yeh, C.-F. Phase Behavior of Ternary Blends of Tactic Poly(Methyl Methacrylate)s and Poly(Styrene-Co-Acrylonitrile). Polym J 1999, 31, 574–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobyn, M.; Brown, J.; Dennis, A.B.; Fakes, M.; gao, Q.; Gamble, J.; Khimyak, Y.Z.; Mcgeorge, G.; Patel, C.; Sinclair, W.; et al. Amorphous Drug-PVP Dispersions: Application of Theoretical, Thermal and Spectroscopic Analytical Techniques to the Study of a Molecule With Intermolecular Bonds in Both the Crystalline and Pure Amorphous State. J Pharm Sci 2009, 98, 3456–3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrdla, P.J.; Floyd, P.D.; Dell’Orco, P.C. Predicting the Solubility Enhancement of Amorphous Drugs and Related Phenomena Using Basic Thermodynamic Principles and Semi-Empirical Kinetic Models. Int J Pharm 2019, 567, 118465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.; Taylor, L.S. Effect of Temperature and Moisture on the Physical Stability of Binary and Ternary Amorphous Solid Dispersions of Celecoxib. J Pharm Sci 2017, 106, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, N.S.; Minor, H. General Procedure for Evaluating Amorphous Scattering and Crystallinity from X-Ray Diffraction Scans of Semicrystalline Polymers. Polymer (Guildf) 1990, 31, 996–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatema, K.; Sajeeb, B.; Sikdar, K.Y.K.; Hossain, A.M. Al; Bachar, S.C. Evaluation of the Formulation of Combined Dosage Form of Albendazole and Mebendazole through In Vitro Physicochemical and Anthelmintic Study. Dhaka Univ. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 21, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhushan, B.; Dubey, P.; Kumar, S.U.; Sachdev, A.; Matai, I.; Gopinath, P. Bionanotherapeutics: Niclosamide Encapsulated Albumin Nanoparticles as a Novel Drug Delivery System for Cancer Therapy. RSC Adv 2015, 5, 12078–12086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Yao, Y. Octenylsuccinate Hydroxypropyl Phytoglycogen Enhances the Solubility and In-Vitro Antitumor Efficacy of Niclosamide. Int J Pharm 2018, 535, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrego-Sánchez, A.; Hernández-Laguna, A.; Sainz-Díaz, C.I. Molecular Modeling and Infrared and Raman Spectroscopy of the Crystal Structure of the Chiral Antiparasitic Drug Praziquantel. J Mol Model 2017, 23, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinosa-Lara, J.C.; Guzman-Villanueva, D.; Arenas-García, J.I.; Herrera-Ruiz, D.; Rivera-Islas, J.; Román-Bravo, P.; Morales-Rojas, H.; Höpfl, H. Cocrystals of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients - Praziquantel in Combination with Oxalic, Malonic, Succinic, Maleic, Fumaric, Glutaric, Adipic, and Pimelic Acids. Cryst Growth Des 2013, 13, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Q. P. Garbuio; T. Hanashiro; B. Markman; F. Fonseca; F. Perazzo; P. Rosa Evaluation and Study of Mebendazole Polymorphs Present in Raw Materials and Tablets Available in the Brazilian Pharmaceutical Market. J Appl Pharm Sci. [CrossRef]

- Skrdla, P.J.; Floyd, P.D.; Dell’Orco, P.C. The Amorphous State: First-Principles Derivation of the Gordon–Taylor Equation for Direct Prediction of the Glass Transition Temperature of Mixtures; Estimation of the Crossover Temperature of Fragile Glass Formers; Physical Basis of the “Rule of 2/3.” Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 20523–20532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzghoul, A.; Alhalaweh, A.; Mahlin, D.; Bergström, C.A.S. Experimental and Computational Prediction of Glass Transition Temperature of Drugs. J Chem Inf Model 2014, 54, 3396–3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasten, G.; Löbmann, K.; Grohganz, H.; Rades, T. Co-Former Selection for Co-Amorphous Drug-Amino Acid Formulations. Int J Pharm 2018. [CrossRef]

- Zanolla, D.; Perissutti, B.; Passerini, N.; Invernizzi, S.; Voinovich, D.; Bertoni, S.; Melegari, C.; Millotti, G.; Albertini, B. Milling and Comilling Praziquantel at Cryogenic and Room Temperatures: Assessment of the Process-Induced Effects on Drug Properties. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2018, 153, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Zografi, G. Phase Behavior of Binary and Ternary Amorphous Mixtures Containing Indomethacin, Citric Acid and PVP. Pharm Res 1998, 15, 1202–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajber, L.; Corrigan, O.I.; Healy, A.M. Physicochemical Evaluation of PVP–Thiazide Diuretic Interactions in Co-Spray-Dried Composites—Analysis of Glass Transition Composition Relationships. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2005, 24, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, T.; Bates, S.; Carvajal, M.T. Toward Understanding the Evolution of Griseofulvin Crystal Structure to a Mesophase after Cryogenic Milling. Int J Pharm 2009, 367, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hancock, B.C.; Shamblin, S.L.; Zografi, G. Molecular Mobility of Amorphous Pharmaceutical Solids Below Their Glass Transition Temperatures. Pharm Res 1995, 12, 799–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Mooter, G. The Use of Amorphous Solid Dispersions: A Formulation Strategy to Overcome Poor Solubility and Dissolution Rate. Drug Discov Today Technol 2012, 9, e79–e85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, M.; Hancock, B.C.; Zografi, G. Crystallization of Indomethacin from the Amorphous State below and above Its Glass Transition Temperature. J Pharm Sci 1994, 83, 1700–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheokand, S.; Modi, S.R.; Bansal, A.K. Dynamic Vapor Sorption as a Tool for Characterization and Quantification of Amorphous Content in Predominantly Crystalline Materials. J Pharm Sci 2014, 103, 3364–3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šagud, I.; Zanolla, D.; Perissutti, B.; Passerini, N.; Škorić, I. Identification of Degradation Products of Praziquantel during the Mechanochemical Activation. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2018, 159, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Wang, Y.; Löbmann, K.; Grohganz, H.; Rades, T. Transformations between Co-Amorphous and Co-Crystal Systems and Their Influence on the Formation and Physical Stability of Co-Amorphous Systems. Mol Pharm 2019, 16, 1294–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovago, I.; Wang, W.; Qiu, D.; Raijada, D.; Rantanen, J.; Grohganz, H.; Rades, T.; Bond, A.; Löbmann, K. Properties of the Sodium Naproxen-Lactose-Tetrahydrate Co-Crystal upon Processing and Storage. Molecules 2016, 21, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilpeläinen, T.; Pajula, K.; Ervasti, T.; Uurasjärvi, E.; Koistinen, A.; Korhonen, O. Raman Imaging of Amorphous-Amorphous Phase Separation in Small Molecule Co-Amorphous Systems. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2020, 155, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Exp. N° | Molar ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| PZQ X1 |

MBZ X2 |

NCM X3 |

|

| 1 | 0.500 | 0.250 | 0.250 |

| 2 | 0.167 | 0.417 | 0.417 |

| 3 | 0 | 0.500 | 0.500 |

| 4 | 0.250 | 0.500 | 0.250 |

| 5 | 0.417 | 0.167 | 0.417 |

| 6 | 0.500 | 0 | 0.500 |

| 7 | 0.250 | 0.250 | 0.500 |

| 8 | 0.417 | 0.417 | 0.167 |

| 9 | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0 |

| 10 | 0.333 | 0.333 | 0.333 |

| Sample / Exp. N° | Molar ratio | Experimental Tg (°C) ± S.D. |

Theoretical Tg according to G-T equation (°C) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PZQ | NCM | MBZ | |||

| PZQ | 1 | 0 | 0 | 40.94* ± 0.90 | 28.56§ |

| NCM | 0 | 1 | 0 | 82.90* ± 0.64 | 85.47§ |

| MBZ | 0 | 0 | 1 | 111.98 ± 0.73 | 142.95§ |

| 1 | 0.500 | 0.250 | 0.250 | / | 63.54 |

| 2 | 0.167 | 0.417 | 0.417 | / | 84.17 |

| 3 | 0 | 0.500 | 0.500 | 98.33 ± 0.34 | 96.95 |

| 4 | 0.250 | 0.500 | 0.250 | 79.54 ± 0.59 | 75.40 |

| 5 | 0.417 | 0.167 | 0.417 | 74.02 ± 0.59 | 71.02 |

| 6 | 0.500 | 0 | 0.500 | 69.31 ± 0.87 | 68.67 |

| 7 | 0.250 | 0.250 | 0.500 | 83.31 ± 0.76 | 81.58 |

| 8 | 0.417 | 0.417 | 0.167 | 60.40 ± 0.13 | 65.40 |

| 9 | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0 | 59.15 ± 0.95 | 57.87 |

| 10 | 0.333 | 0.333 | 0.333 | 76.77 ± 0.09 | 73.15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).