Submitted:

31 August 2025

Posted:

03 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Cocrystals with Solvent Evaporation (SEV) Method

2.3. Preparation of Cocrystals with Solvent/Anti−Solvent (SAS) Method

2.4. Preparation of Single Crystal

2.5. Morphology Evaluation

2.6. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

2.7. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

2.8. Powder X−Ray Diffraction (PXRD) and Single-Crystal X-Ray Diffraction (SCXRD)

2.9. Bioanalytical Method Development

2.10. Saturation Solubility

2.11. In Vitro Dissolution

2.12. In Vivo Pharmacokinetics

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

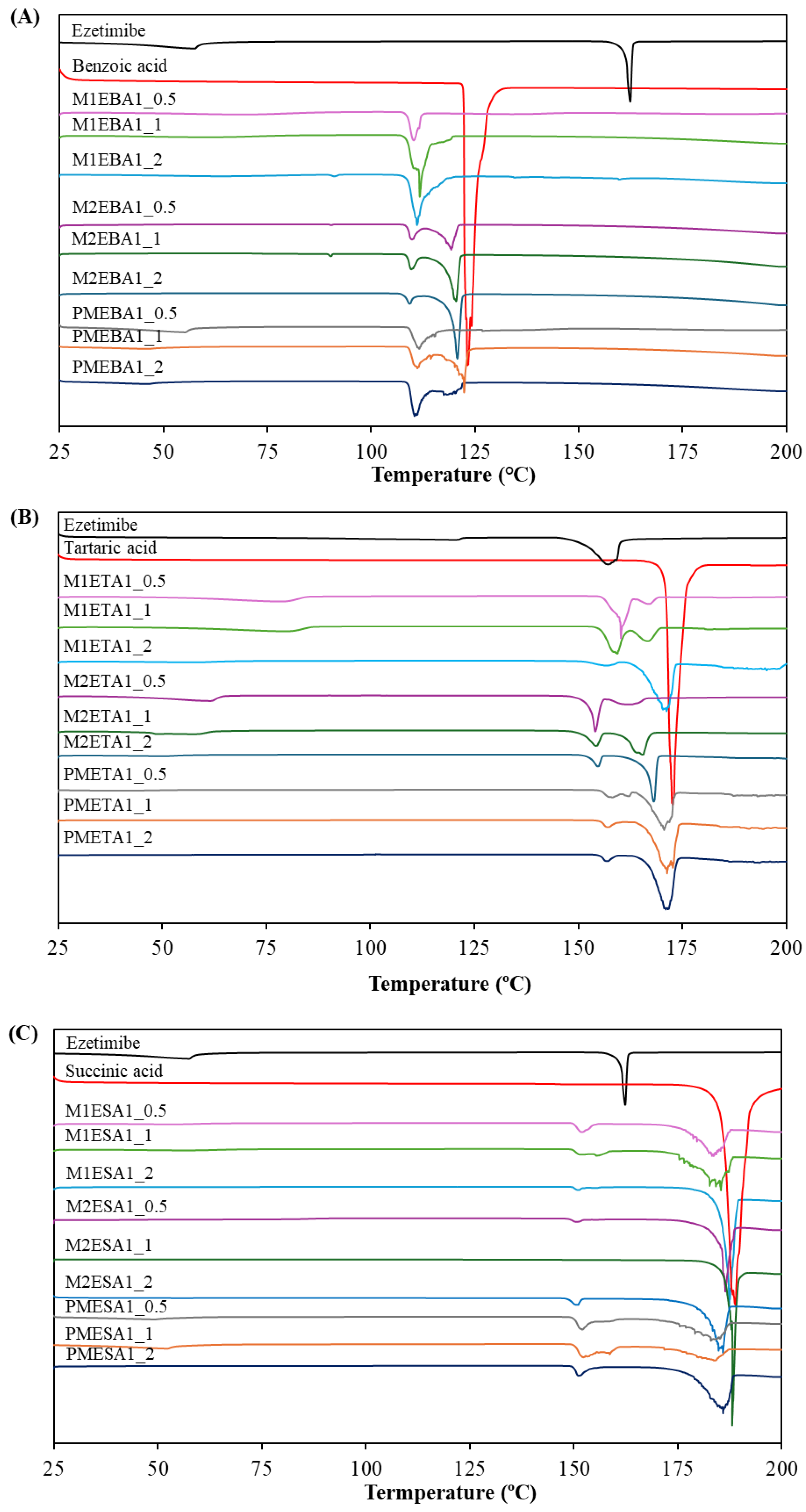

3.1. Thermodynamic Properties

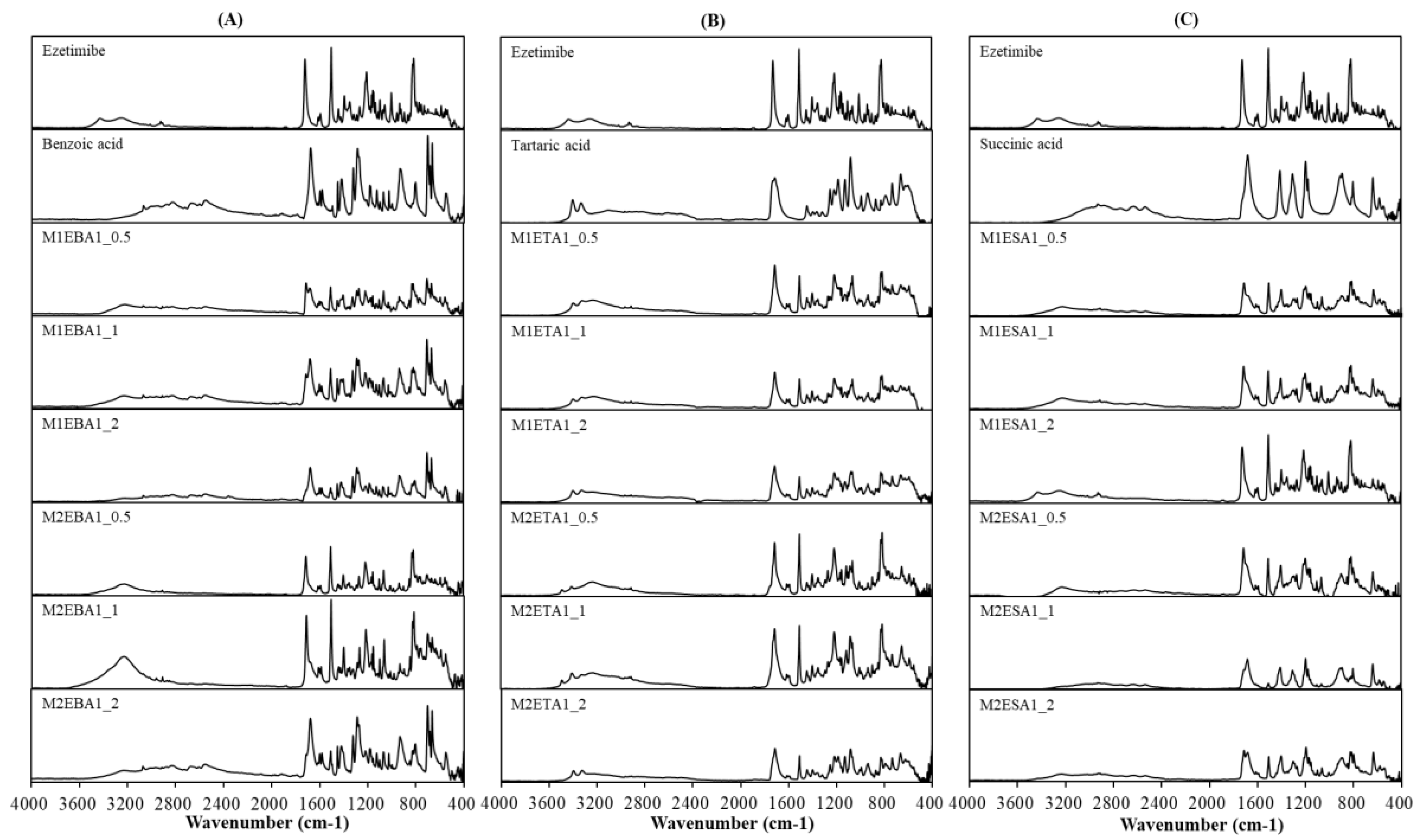

3.2. Physicochemical Interactions

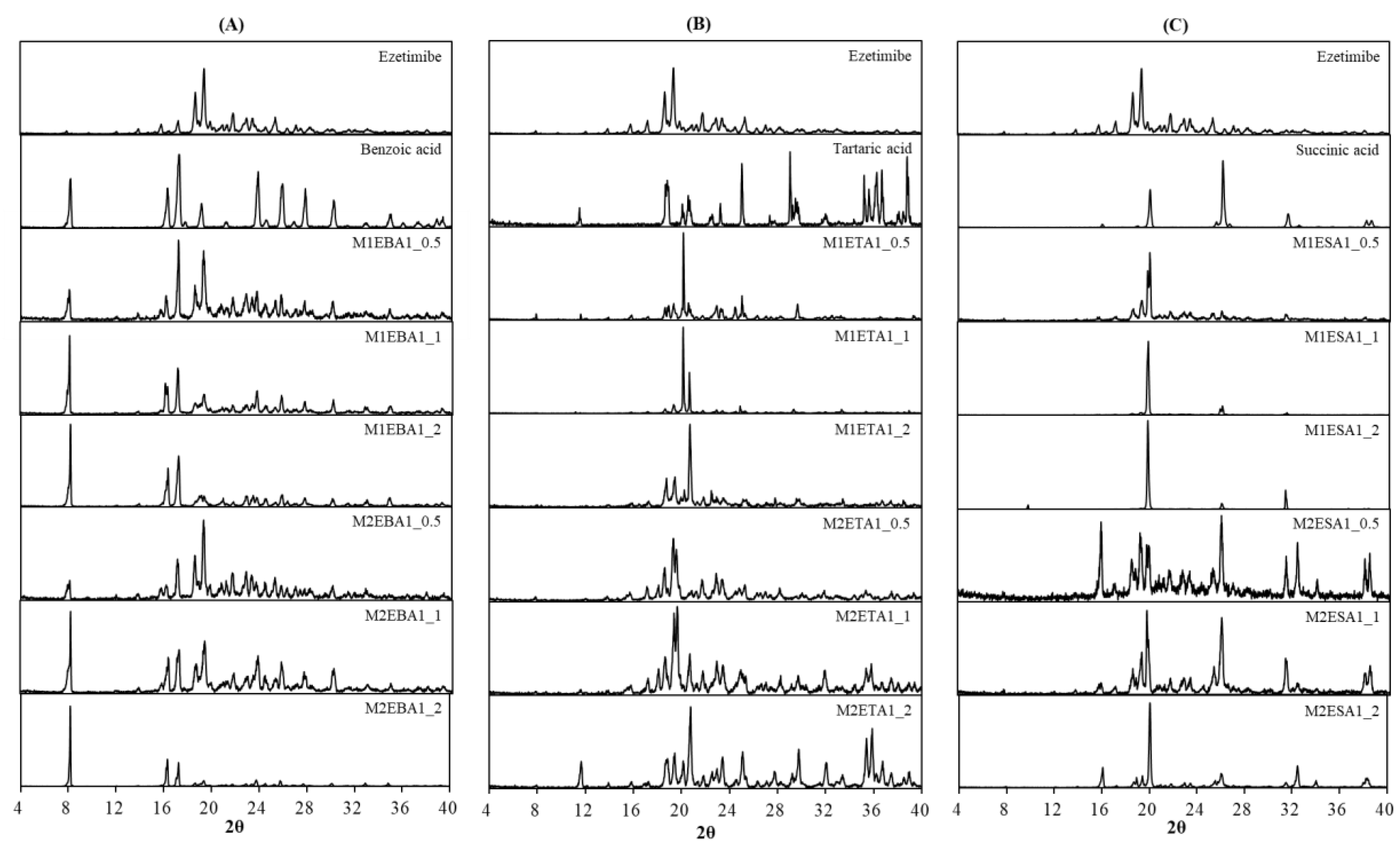

3.3. Crystallinity

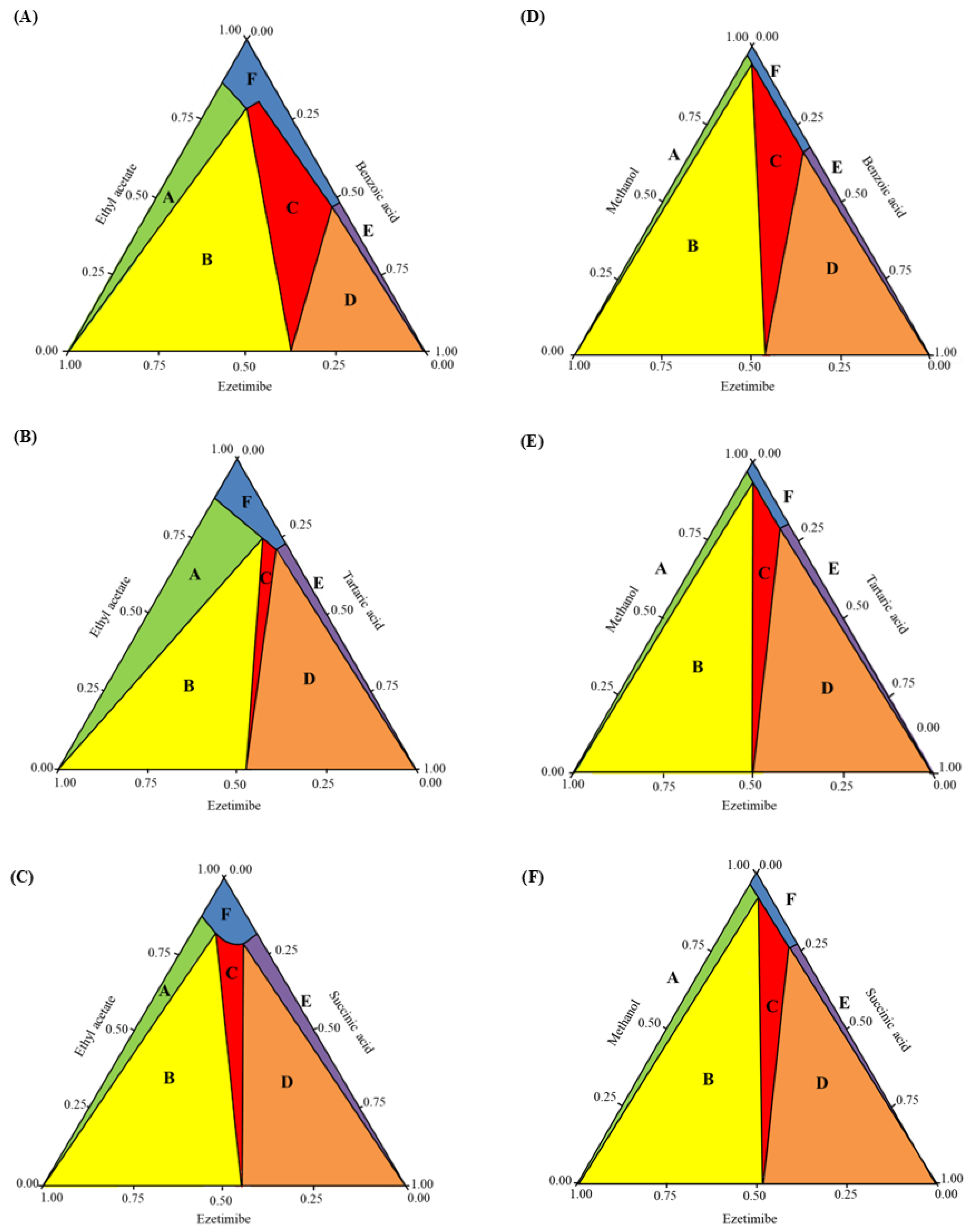

3.4. Phase Diagram

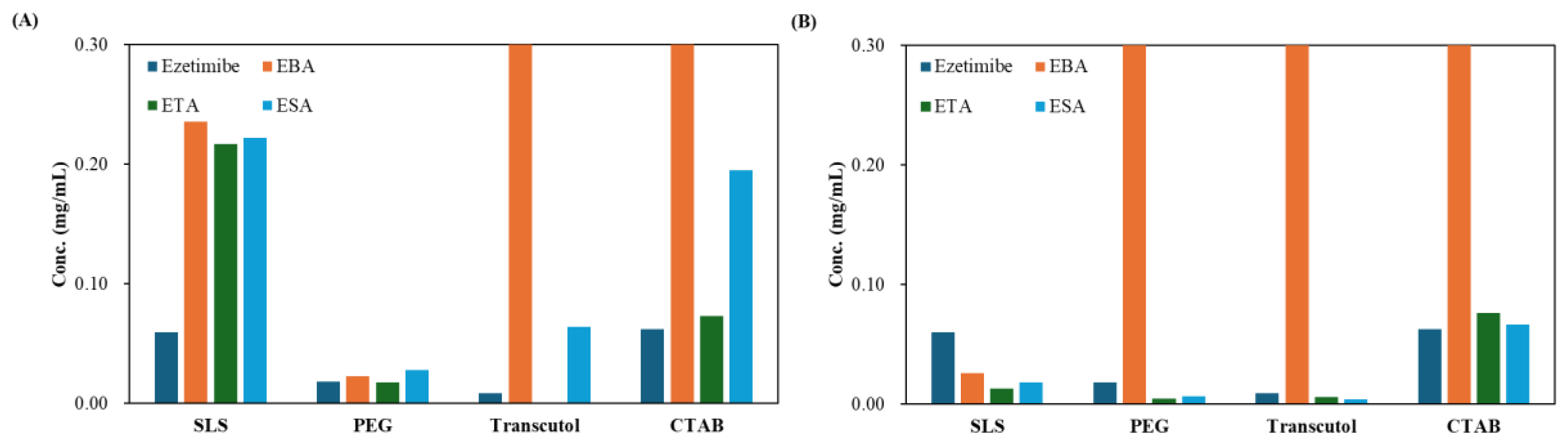

3.5. Solubility

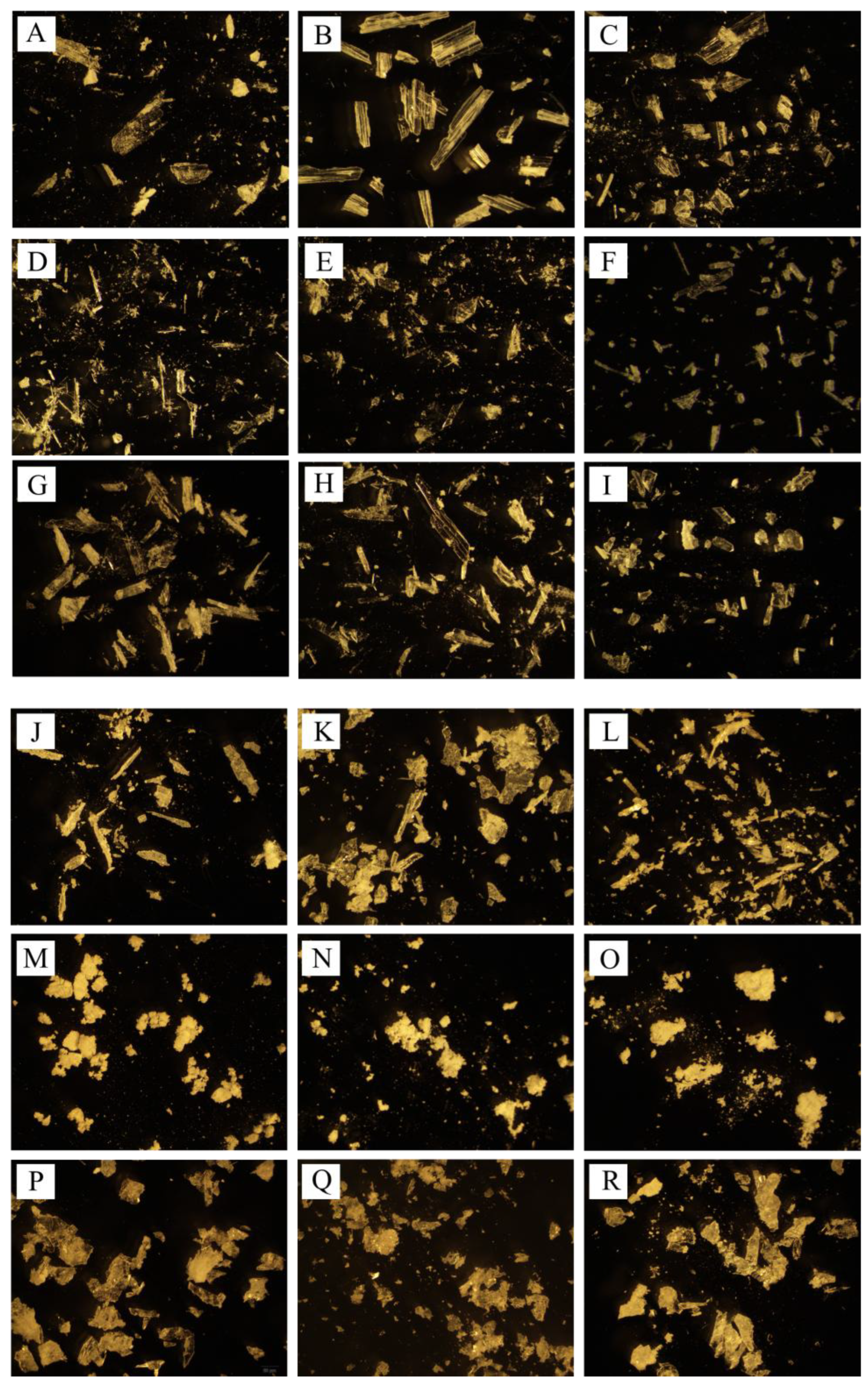

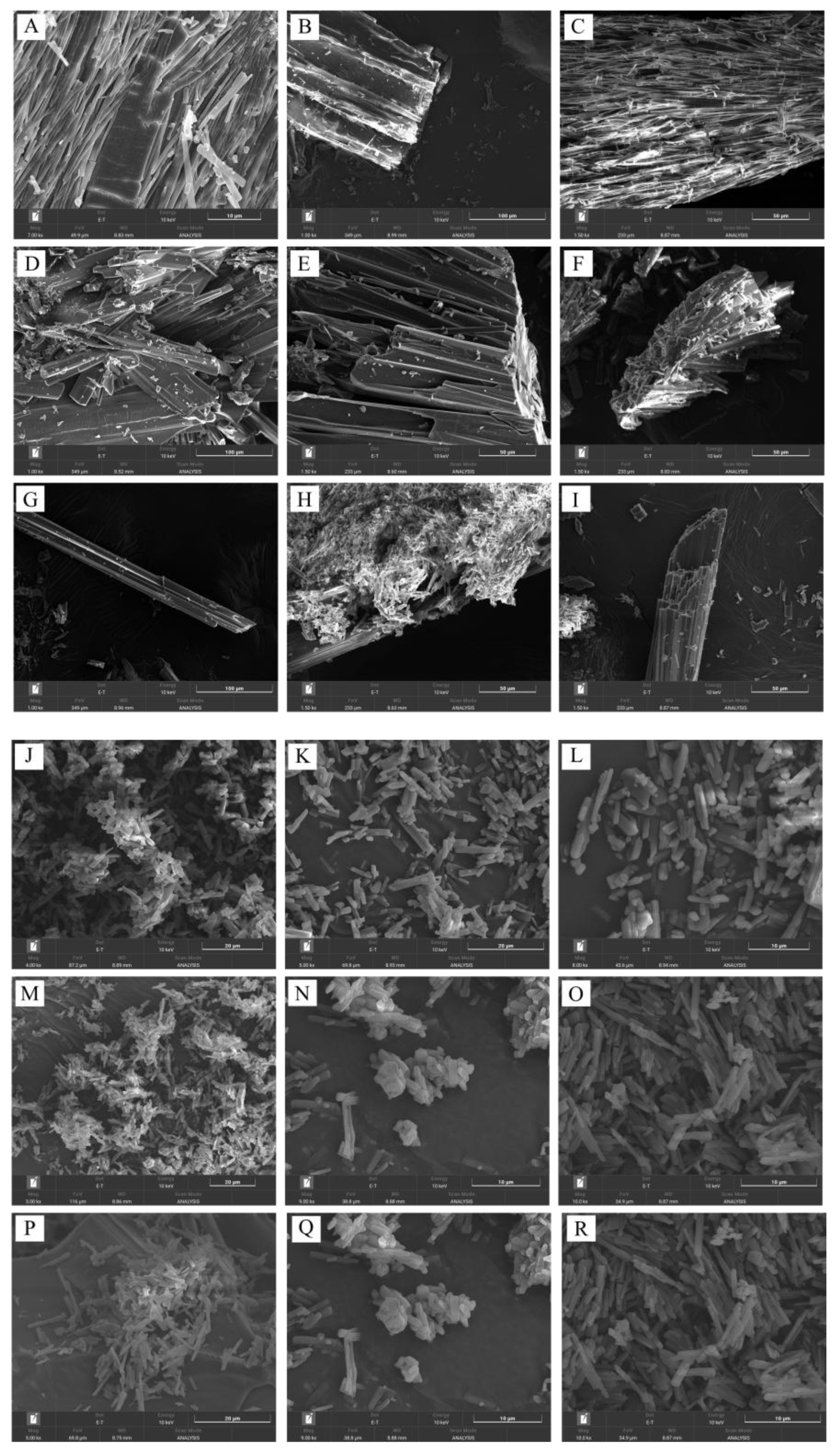

3.6. Morphology

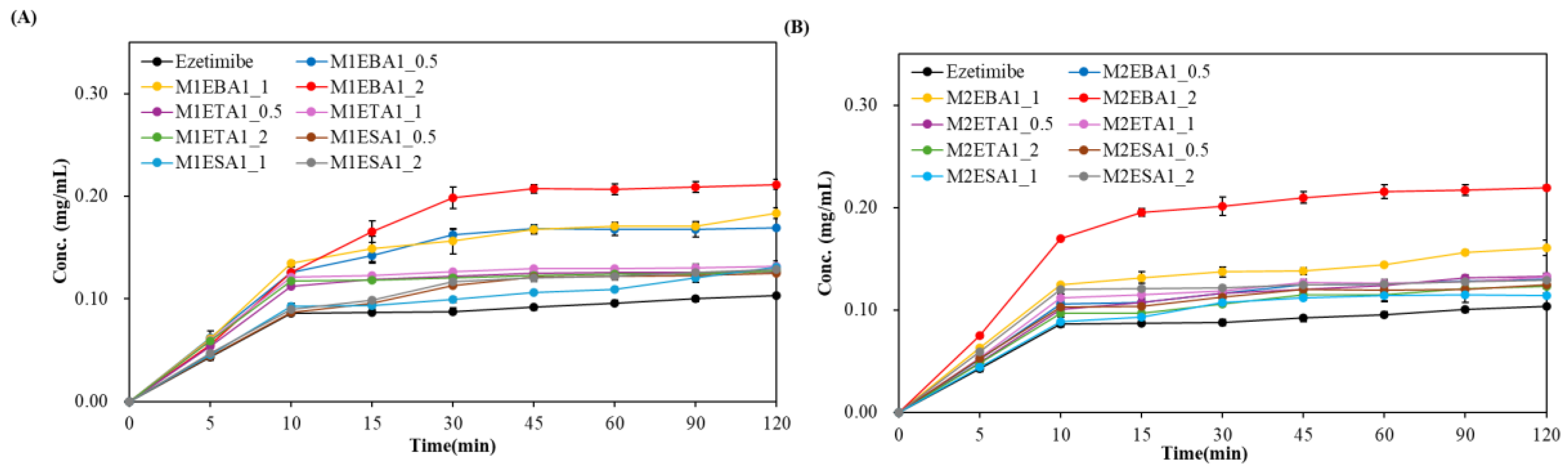

3.7. Effects of SEV and SAS Methods on Cocrystals

3.8. Impact of the Drying Rate on Cocrystals

3.9. In Vivo Pharmacokinetic Evaluation

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kavanagh, O.N. An analysis of multidrug multicomponent crystals as tools for drug development. J. Control. Release 2024, 369, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalani, D.V.; Nutan, B.; Kumar, A.; Singh Chandel, A.K. Bioavailability enhancement techniques for poorly aqueous soluble drugs and therapeutics. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aakeröy, C.B.; Fasulo, M.E.; Desper, J. Cocrystal or salt: does it really matter? Mol. Pharmaceutics 2007, 4, 317–322. [Google Scholar]

- Haneef, J.; Amir, M.; Sheikh, N.A.; Chadha, R. Mitigating drug stability challenges through cocrystallization. AAPS PharmSciTech 2023, 24, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, N.; Zaworotko, M.J. The role of cocrystals in pharmaceutical science. Drug Discov. Today 2008, 13, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Abbrunzo, I.; Gigli, L.; Demitri, N.; Sabena, C.; Nervi, C.; Chierotti, M.R.; Bertoni, S.; Škorić, I.; Häberli, C.; Keiser, J. Higher-order multicomponent crystals as a strategy to decrease the IC50 parameter: the case of praziquantel, niclosamide and acetic acid. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2025, 109, 106974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggirala, N.K.; Perry, M.L.; Almarsson, Ö.; Zaworotko, M.J. Pharmaceutical cocrystals: along the path to improved medicines. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 640–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, O.N.; Croker, D.M.; Walker, G.M.; Zaworotko, M.J. Pharmaceutical cocrystals: from serendipity to design to application. Drug Discov. Today 2019, 24, 796–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimpi, M.R.; Childs, S.L.; Boström, D.; Velaga, S.P. New cocrystals of ezetimibe with L-proline and imidazole. CrystEngComm 2014, 16, 8984–8993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, P.; Pandey, J.; Tandon, P.; Sinha, K.; Shimpi, M.R. Molecular Structural, Hydrogen Bonding Interactions, and Chemical Reactivity Studies of Ezetimibe-L-Proline Cocrystal Using Spectroscopic and Quantum Chemical Approach. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 848014. [Google Scholar]

- Childs, S.L.; Chyall, L.J.; Dunlap, J.T.; Smolenskaya, V.N.; Stahly, B.C.; Stahly, G.P. Crystal engineering approach to forming cocrystals of amine hydrochlorides with organic acids. Molecular complexes of fluoxetine hydrochloride with benzoic, succinic, and fumaric acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 13335–13342. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grecu, T.; Hunter, C.A.; Gardiner, E.J.; McCabe, J.F. Validation of a computational cocrystal prediction tool: comparison of virtual and experimental cocrystal screening results. Cryst. Growth Des. 2014, 14, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramov, Y.A.; Shah, H.S.; Michelle, C.; Wan, Z.; Xie, T.; Kuang, S.; Wang, J. Computational and Experimental Cocrystal Screening of Tiopronin and Dapagliflozin APIs: Development and Validation of a New Virtual Screening Model. Cryst. Growth Des. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, F.G.; Roberts-Skilton, K.; Kennedy-Gabb, S.A. A solid-state NMR study of amorphous ezetimibe dispersions in mesoporous silica. Pharm. Res. 2013, 30, 2315–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indrayanto, G.; Syahrani, A.; Rahman, A.; Tanudjojo, W.; Susanti, S.; Yuwono, M.; Ebel, S. Benzoic acid. In Analytical profiles of drug substances and excipients; Elsevier: 1999; Volume 26, pp. 1-46.

- Shen, J.; Zheng, J.; Che, Y.; Xi, B. Growth and properties of organic nonlinear optical crystals: l-tartaric acid–nicotinamide and d-tartaric acid–nicotinamide. J. Cryst. Growth 2003, 257, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wu, L.; Wang, J.; Huang, C.; Leng, Y. Determination and molecular simulation of ternary solid–liquid phase equilibrium of succinic acid+ maleic acid+ water from 283. 15 K to 333.15 K. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2024, 191, 107228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, N.; Yu, H.; Wang, Y.; Xing, C.; Hu, K.; Du, G.; Lu, Y. Crystal structures, stability, and solubility evaluation of a 2: 1 diosgenin–piperazine cocrystal. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2020, 10, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, R.; Nanda, A. Formulation and Evaluation of Cocry-stals of a Bcs Class Ii Drug Using Glycine As Coformer. Int. J. Appl. Pharm. 2022, 14, 68–76. [Google Scholar]

- Schultheiss, N.; Newman, A. Pharmaceutical cocrystals and their physicochemical properties. Cryst. Growth Des. 2009, 9, 2950–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugandha, K.; Kaity, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Isaac, J.; Ghosh, A. Solubility enhancement of ezetimibe by a cocrystal engineering technique. Cryst. Growth Des. 2014, 14, 4475–4486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulye, S.P.; Jamadar, S.A.; Karekar, P.S.; Pore, Y.V.; Dhawale, S.C. Improvement in physicochemical properties of ezetimibe using a crystal engineering technique. Powder Technol. 2012, 222, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainouz, A.; Authelin, J.-R.; Billot, P.; Lieberman, H. Modeling and prediction of cocrystal phase diagrams. Int. J. Pharm. 2009, 374, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surov, A.O.; Ramazanova, A.G.; Voronin, A.P.; Drozd, K.V.; Churakov, A.V.; Perlovich, G.L. Virtual Screening, Structural Analysis, and Formation Thermodynamics of Carbamazepine Cocrystals. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjandrawinata, R.R.; Hiendrawan, S.; Veriansyah, B. Processing paracetamol-5-nitroisophthalic acid cocrystal using supercritical CO2 as an anti-solvent. Int. J. Appl. Pharm 2019, 11, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Siril, P.F.; Soni, P. Preparation of Nano-RDX by Evaporation Assisted Solvent? Antisolvent Interaction. Propell. Explos. Pyrotech. 2014, 39, 383–389. [Google Scholar]

- Gadhiya, D.T.; Patel, J.K.; Bagada, A.A. An impact of nanocrystals on dissolution rate of Lercanidipine: Supersaturation and crystallization by addition of solvent to antisolvent. Future J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 7, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Henry, R.F.; Zhang, G.G. Cocrystal screening in minutes by solution-mediated phase transformation (SMPT): Preparation and characterization of ketoconazole cocrystals with nine aliphatic dicarboxylic acids. J. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 114, 592–598. [Google Scholar]

- Nernst, W. Theorie der Reaktionsgeschwindigkeit in heterogenen Systemen. Z. Phys. Chem. 1904, 47, 52–55. [Google Scholar]

- Shahidzadeh, N.; Schut, M.F.; Desarnaud, J.; Prat, M.; Bonn, D. Salt stains from evaporating droplets. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, D.P.; Holm, R.; De Diego, H.L. Use of pharmaceutical salts and cocrystals to address the issue of poor solubility. Int. J. Pharm. 2013, 453, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serajuddin, A.T. Salt formation to improve drug solubility. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2007, 59, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, D.; Mak, A.T.; Lakerveld, R. Intensified solid-state transformation during anti-solvent cocrystallization in flow. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2025, 208, 110108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, A.K.; Liu, D.; Peukert, S.; Ge, H.; Gai, Y.; Chang, X. Naphthyridinone derivatives for the treatment of a disease or disorder. 2025.

| 1st Tm | 2nd Tm | ||||

| ºC | J/g | ºC | J/g | ||

| API | Ezetimibe | 162.36 | 87.04 | - | - |

| Coformer | Benzoic acid | 123.19 | 148.9 | - | - |

| SEV method | M1EBA1_0.5 | 110.24 | 50.05 | - | - |

| M1EBA1_1 | 111.68 | 120.5 | - | - | |

| M1EBA1_2 | 111.06 | 107.8 | - | - | |

| SAS method | M21EBA1_0.5 | 109.76 | 26.89 | 119.27 | 70.56 |

| M2EBA1_1 | 109.65 | 18.04 | 120.44 | 96.95 | |

| M2EBA1_2 | 109.22 | 10.18 | 120.76 | 109.5 | |

| Physical mixture | PMEBA1_0.5 | 110.24 | 8.277 | 162.44 | 68.03 |

| PMEBA1_1 | 111.14 | 33.87 | 122.38 | 56.96 | |

| PMEBA1_2 | 110.43 | 56.01 | 119.55 | 22.84 | |

| Coformer | Tartaric acid | 172.67 | 251.2 | - | - |

| SEV method | M1ETA1_0.5 | 160.24 | 82.41 | 167.25 | 13.83 |

| M1ETA1_1 | 159.32 | 68.19 | 166.70 | 35.06 | |

| M1ETA1_2 | 156.38 | 13.31 | 171.18 | 182.4 | |

| SAS method | M21ETA1_0.5 | 154.14 | 61.87 | 162.58 | 33.18 |

| M2ETA1_1 | 154.22 | 39.60 | 165.35 | 89.38 | |

| M2ETA1_2 | 154.67 | 29.09 | 168.12 | 144.3 | |

| Physical mixture | PMETA1_0.5 | 158.11 | 11.478 | 170.59 | 143.8 |

| PMETA1_1 | 157.01 | 12.39 | 171.33 | 183.4 | |

| PMETA1_2 | 156.84 | 12.09 | 171.01 | 188.9 | |

| Coformer | Succinic acid | 188.91 | 299.6 | - | - |

| SEV method | M1ESA1_0.5 | 151.82 | 17.62 | 183.22 | 111.1 |

| M1ESA1_1 | 155.57 | 24.83 | 185.36 | 154.0 | |

| M1ESA1_2 | 150.92 | 2.79 | 187.38 | 231.8 | |

| SAS method | M21ESA1_0.5 | 150.39 | 4.55 | 186.44 | 174.8 |

| M2ESA1_1 | - | - | 188.08 | 245.4 | |

| M2ESA1_2 | 149.55 | 1.78 | 187.06 | 223.3 | |

| Physical mixture | PMESA1_0.5 | 152.03 | 21.01 | 182.97 | 118.8 |

| PMESA1_1 | 152.25 | 52.72 | 183.65 | 70.14 | |

| PMESA1_2 | 151.16 | 22.04 | 185.89 | 177.1 | |

| Cocrystal I (benzoic acid) |

Cocrystal II (tartaric acid) |

Cocrystal III (succinic acid) |

Ezetimibe | Functional group | ||||

| SEV | SAS | SEV | SAS | SEV | SAS | |||

| 1: 0.5 | 3224.89 | 3228.57 | - | - | 3230.96 | 3228.57 | 3264.09 | O-H |

| 2912.29 | 2912.94 | - | - | 2912.90 | 2912.94 | 2928.09 | C-H | |

| - | 1714.46 | 1713.08 | 1715.16 | 1714.11 | 1714.46 | 1726.06 | C=O | |

| 1507.88 | 1507.70 | 1507.63 | 1507.92 | 1507.89 | 1507.70 | 1507.08 | C=C | |

| 1218.85 | 1218.67 | 1218.64 | 1219.11 | 1200.53 | 1218.67 | 1212.71 | C-F | |

| 1: 1 | - | 3234.65 | - | 3406.25 | 3220.01 | - | 3264.09 | O-H |

| - | 2912.69 | - | - | 2912.97 | 2930.36 | 2928.09 | C-H | |

| 1713.53 | 1713.42 | 1713.46 | 1715.19 | 1713.14 | - | 1726.06 | C=O | |

| 1507.94 | 1507.58 | 1507.53 | 1507.99 | 1507.81 | 1506.62 | 1507.08 | C=C | |

| 1219.04 | 1218.49 | 1217.82 | 1218.20 | 1200.78 | 1196.61 | 1212.71 | C-F | |

| 1: 2 | - | - | 3324.29 | 3396.99 | 3230.96 | - | 3264.09 | O-H |

| - | 2828.22 | - | - | 2928.02 | 2912.70 | 2928.09 | C-H | |

| 1712.60 | 1678.48 | 1714.94 | 1713.99 | 1724.75 | 1713.97 | 1726.06 | C=O | |

| 1507.76 | 1508.94 | 1507.93 | 1508.27 | 1506.87 | 1507.74 | 1507.08 | C=C | |

| 1219.82 | 1220.23 | 1217.57 | 1217.08 | 1212.61 | 1197.52 | 1212.71 | C-F | |

| Property |

Cocrystal I (benzoic acid) |

Cocrystal II (tartaric acid) |

Cocrystal III (succinic acid) |

| Mol. Wt. | Ezetimibe: 404.45 g/mol | Ezetimibe: 404.45 g/mol | Ezetimibe: 404.45 g/mol |

| Benzoic acid: 122.12 g/mol | Tartaric acid: 150.09 g/mol | Succinic acid: 118.09 g/mol | |

| Space group | P2₁/n | P212121 | P212121 |

| Monoclinic | Orthorhombic | Orthorhombic | |

| a = 5.42 Å | a = 6.18 Å | a = 6.19 Å | |

| b = 5.05 Å | b = 15.45 Å | b = 15.47 Å | |

| c = 21.61 Å | c = 21.91 Å | c = 21.96 Å | |

| α = 90.00° | α = 89.98° | α = 90.00° | |

| β = 95.95° | β = 90.03° | β = 90.00° | |

| γ = 90.00° | γ = 90.00° | γ = 90.00° | |

| Z (Units/cell) | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Parameters | Mean ± SD |

| Slope | 44.58 ± 0.02 |

| Intercept | 0.01 |

| Correlation coefficient (R2) | 0.9994 |

| Limit of quantification (LOQ) | 0.04 µg/mL |

| Limit of detection (LOD) | 0.01 µg/mL |

| Formulation | Dose (mg/kg) | Cmax (ng/mL) | Tmax (h) | AUClast (ng·h/mL) | AUCinf (ng·h/mL) |

| CRYS101 | 10 | 6.73 ± 4.29 | 1.33 ± 0.76 | 11.03 ± 8.63 | 41.83# |

| CRYS102 | 30 | 5.50 ± 4.23 | 1.13 ± 0.48 | 15.26 ± 7.08 | 31.08# |

| CRYS103 | 30 | 18.38 ± 9.52 | 2.83 ± 2.75 | 40.36 ± 30.94 | 17.75# |

| CRYS104 | 30 | 4.30 ± 3.25 | 1.00# | 9.62 ± 8.82 | ND |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).