Submitted:

09 December 2024

Posted:

10 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Blood Samples

2.2. Hemograms and Free Hemoglobin

2.3. Rheometry

2.3.1. Tests in Simple Shear Flow

2.3.2. Tests in Oscillatory Shear Flow

2.4. Data Processing and Statistics

3. Results

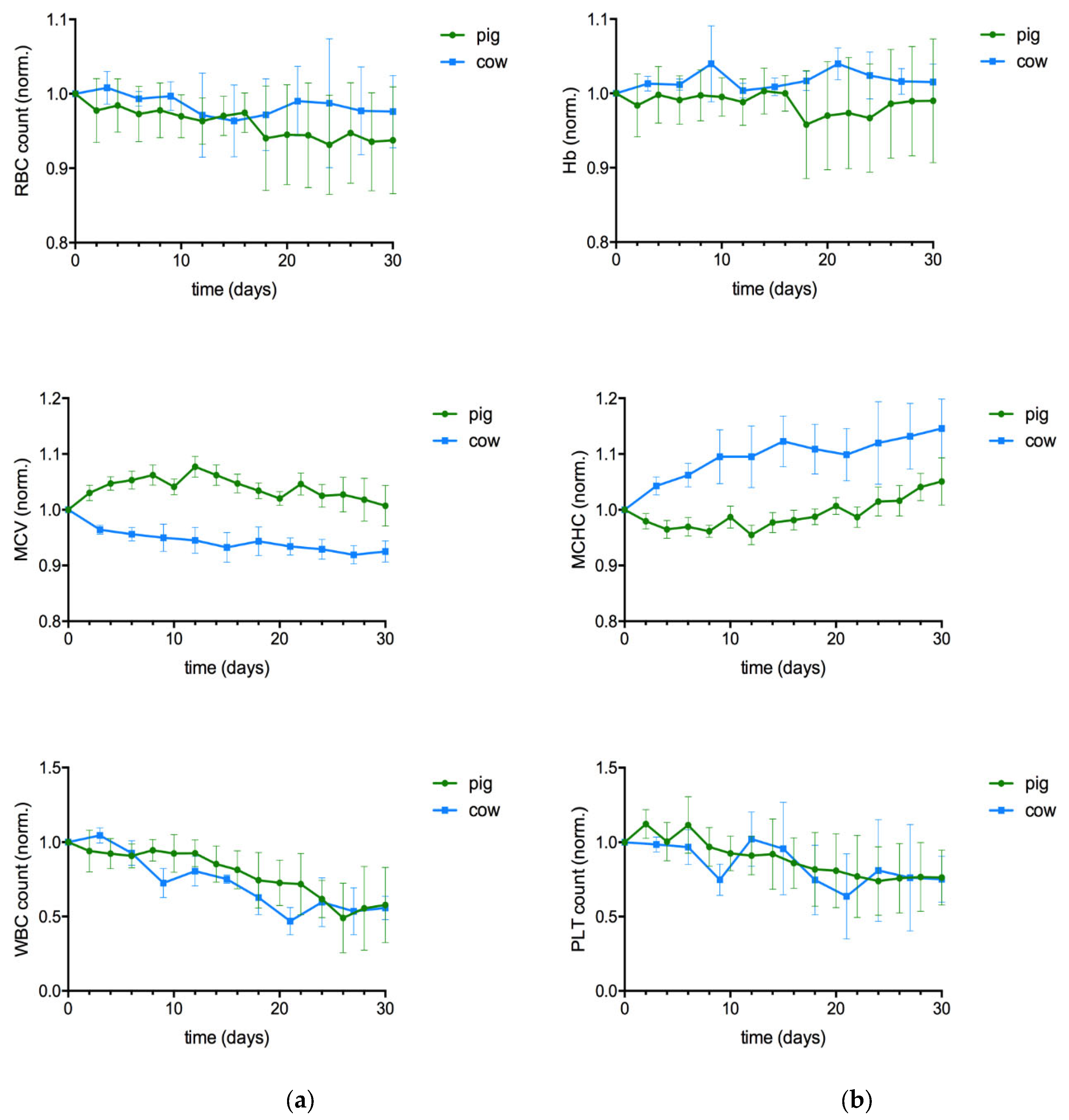

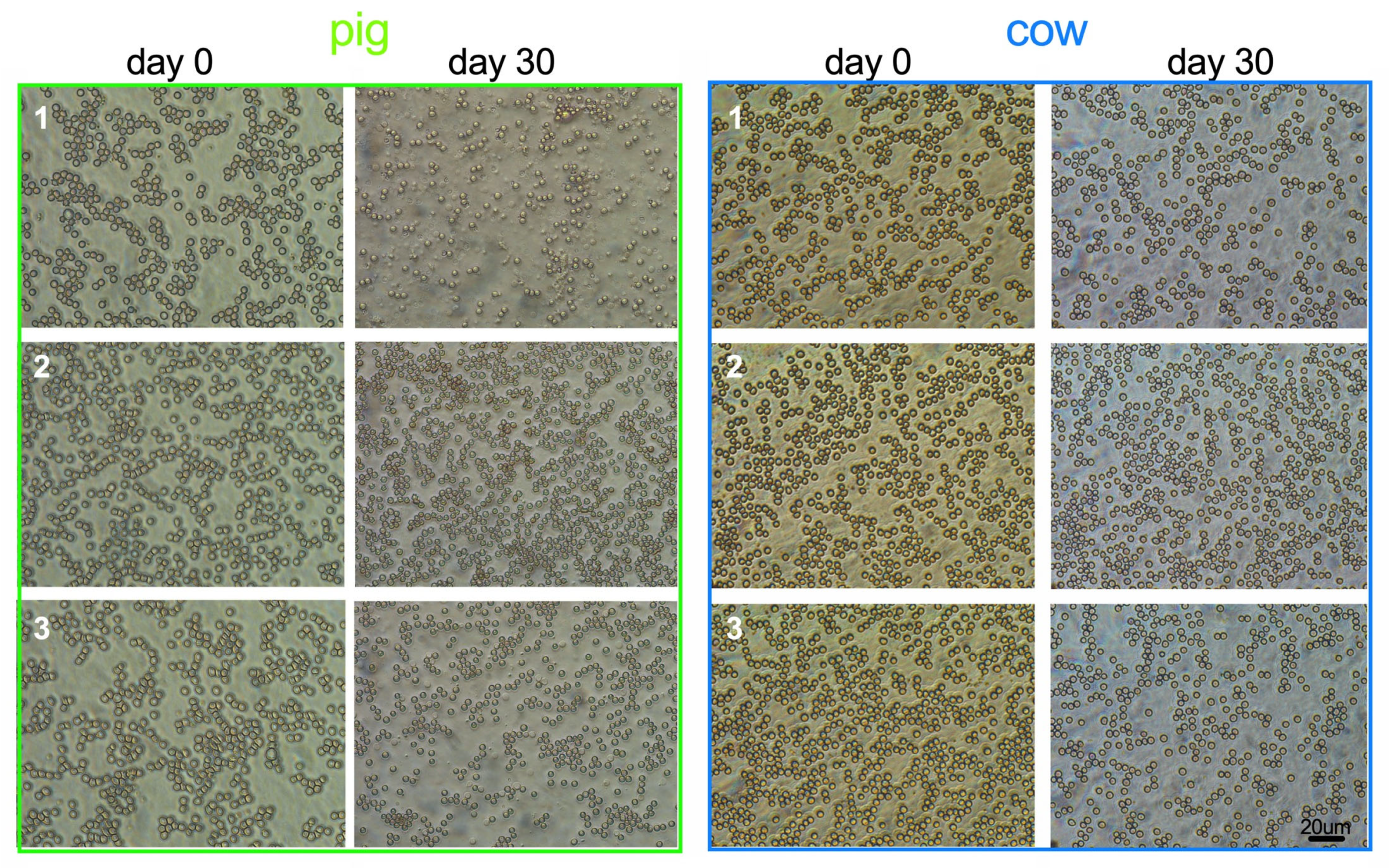

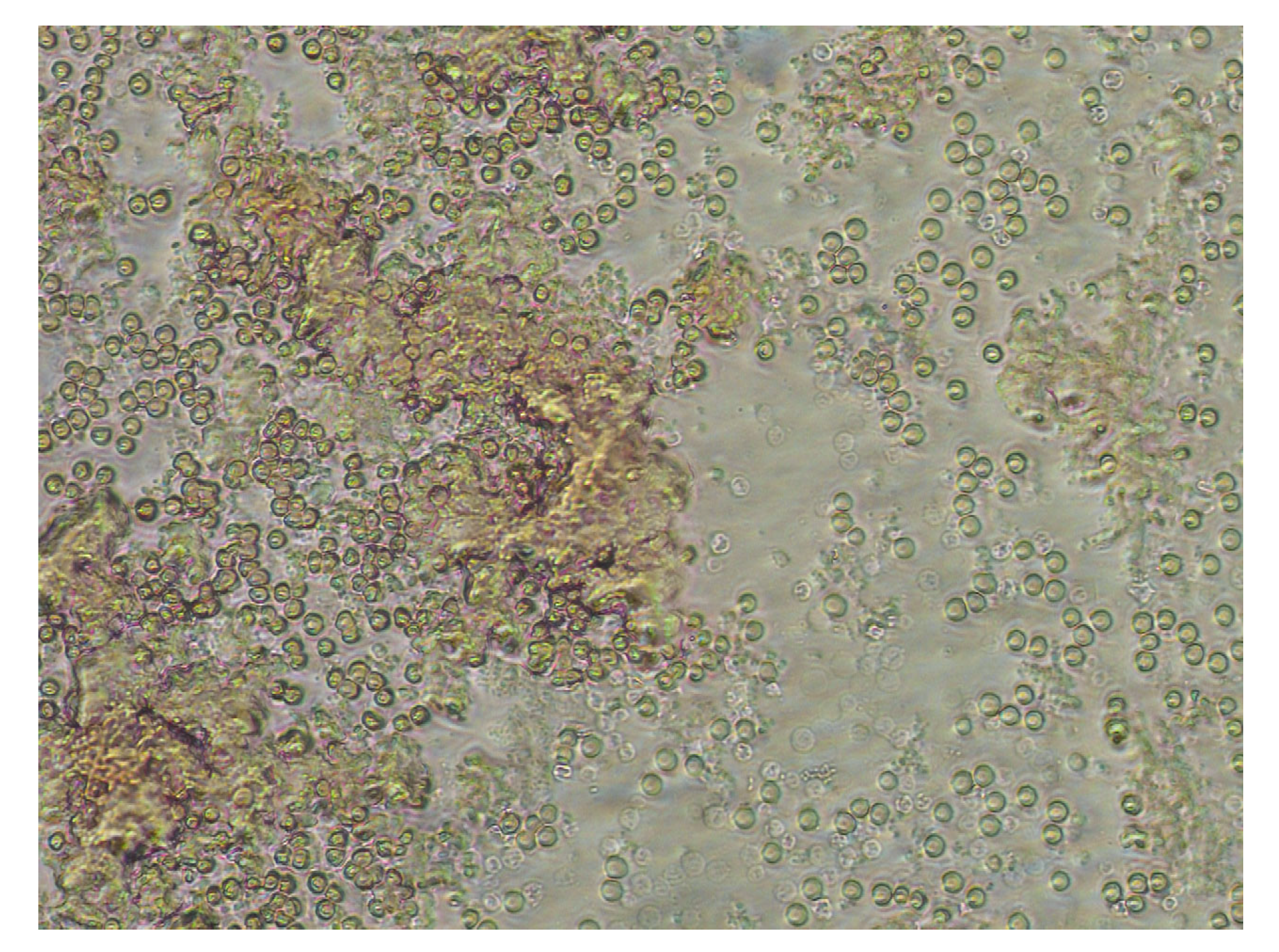

3.1. Hemograms and Hemolysis

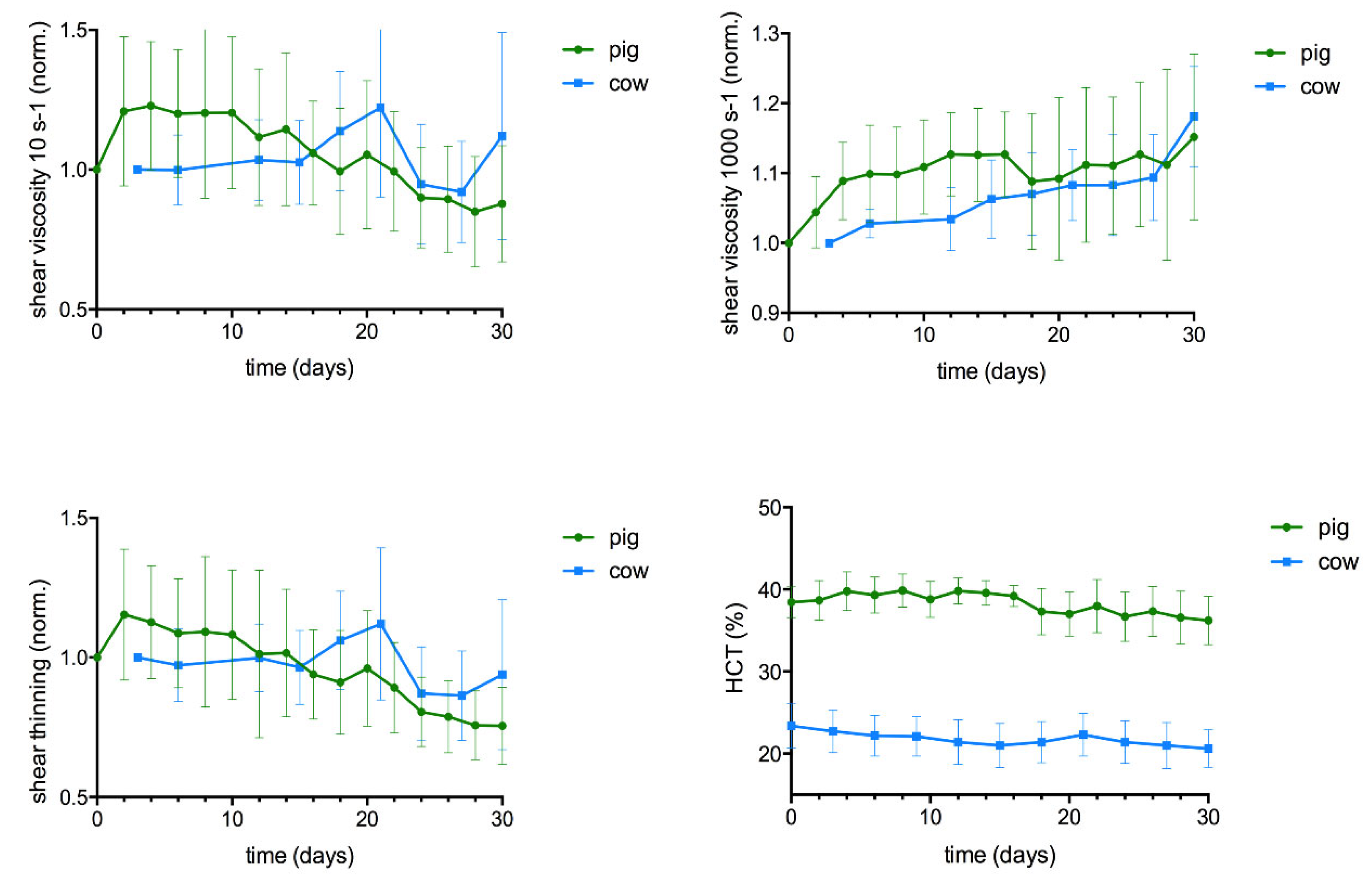

3.2. Rheology

3.2.1. Tests at Simple Shear Flow (Blood Viscosity)

3.2.2. Tests at Oscillating Shear Flow (Shear Moduli)

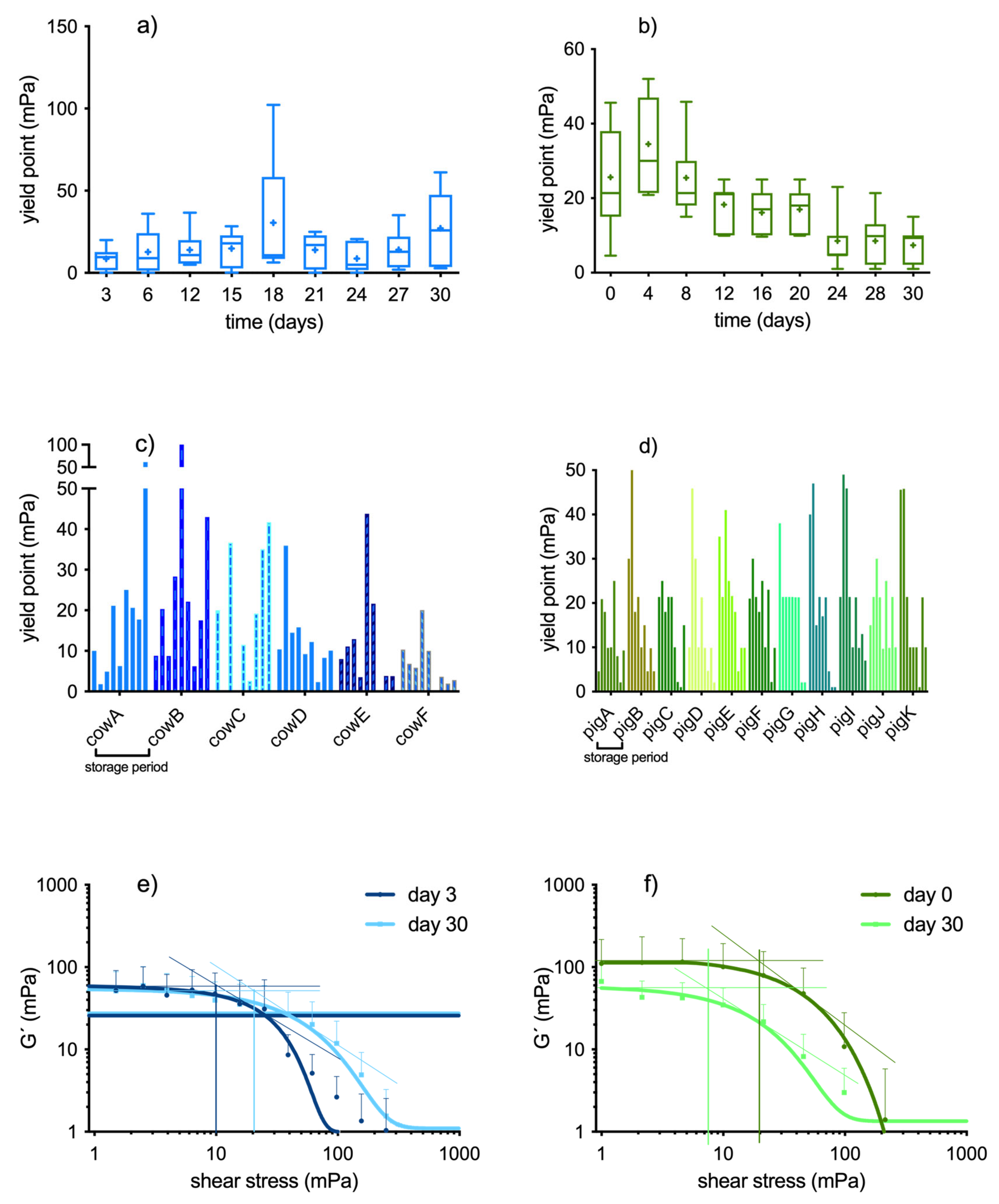

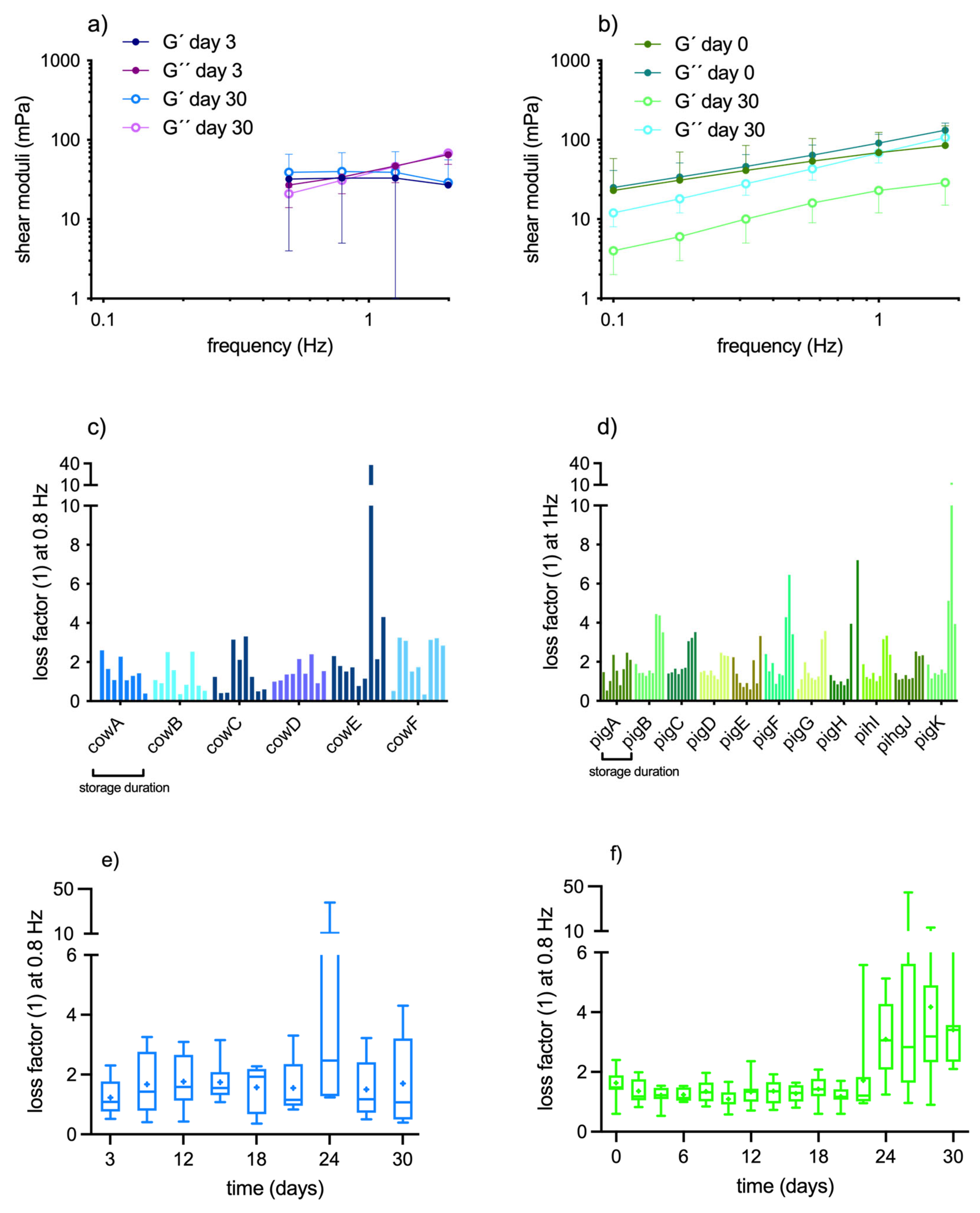

3.2.2.1. Amplitude Sweep Tests

3.2.2.2. Frequency Sweep Tests

3.2.3. Summary of Similarities and Differences Between Pig and Cow Blood During Ageing

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Berndt M, Buttenberg M, Graw JA. Large Animal Models for Simulating Physiology of Transfusion of Red Cell Concentrates—A Scoping Review of The Literature. Vol. 58, Medicina (Lithuania). MDPI; 2022.

- Watts S, Nordmann G, Brohi K, Midwinter M, Woolley T, Gwyther R, et al. Evaluation of prehospital blood products to attenuate acute coagulopathy of trauma in a model of severe injury and shock in anesthetized pigs. Shock. 2015 Aug 1;44:138–48.

- Gourlay T, Simpson C, Robertson CA. Development of a portable blood salvage and autotransfusion technology to enhance survivability of personnel requiring major medical interventions in austere or military environments. J R Army Med Corps. 2018 ;164(2):96–102. 1 May.

- Baskurt OK, Farley RA, Meiselman HJ. Erythrocyte aggregation tendency and cellular properties in horse, human, and rat: A comparative study. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1997;273(6 42-6).

- Sparer A, Serp B, Schwarz L, Windberger U. Storability of porcine blood in forensics: How far should we go? Forensic Sci Int. 2020;311:110268.

- Windberger U, Sparer A, Huber J, Windberger U, Sparer A, Huber J. Cow blood - a superior storage option in forensics? 2022.

- Windberger, U. Blood suspensions in animals. In: Dynamics of Blood Cell Suspensions in Microflows [Internet]. CRC Press; 2019. p. 371–419. [CrossRef]

- Ecker P, Sparer A, Lukitsch B, Elenkov M, Seltenhammer M, Crevenna R, et al. Animal blood in translational research: How to adjust animal blood viscosity to the human standard. Physiol Rep. 2021;9(10):1–10.

- Cooper DKC, Hara H, Yazer M. Genetically Engineered Pigs as a Source for Clinical Red Blood Cell Transfusion. Clin Lab Med. 2010 Jun;30(2):365–80.

- Windberger, U; Sparer, A; Elsayad K. The role of plasma for the yield stress of blood. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2023;1–15.

- Bush JA, Berlin NI, Jensen WN, Brill AB, Cartwright GE, Wintrobe MM. Erythrocyte life span in growing swine as determined by glycine-2-C14. J Exp Med. 1955 ;101(5):451–9. 1 May.

- Blasi B, D’Alessandro A, Ramundo N, Zolla L. Red blood cell storage and cell morphology. Transfusion Medicine. 2012;22(2):90–6.

- Flatt, F. JF, Bawazir M. WM, Bruce LJ. The involvement of cation leaks in the storage lesion of red blood cells. Vol. 5 JUN, Frontiers in Physiology. Frontiers Research Foundation; 2014.

- Leal JKF, Adjobo-Hermans MJW, Bosman GJCGM. Red blood cell homeostasis: Mechanisms and effects of microvesicle generation in health and disease. Vol. 9, Frontiers in Physiology. Frontiers Media S.A.; 2018.

- Buttari B, Profumo E, Riganò R. Crosstalk between Red Blood Cells and the Immune System and Its Impact on Atherosclerosis. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:1–8.

- Rubin O, Canellini G, Delobel J, Lion N, Tissot JD. Red Blood Cell Microparticles: Clinical Relevance. Transfusion Medicine and Hemotherapy. 2012;39(5):342–7.

- Kennedy B, Mirza S, Mandiangu T, Bissinger R, Stotesbury TE, Jones-Taggart H, et al. Examination of Bovine Red Blood Cell Death in Vitro in Response to Pathophysiologic Proapoptotic Stimuli. Frontiers in Bioscience-Landmark. 2023 Dec 6;28(12):331.

- Nakashima, H; Nakagawa, Y; Makino S. Detection of the associated state of membrane proteins by polyacrylamide gradient gel electrophoresis with non-denaturing detergents Application to band 3 protein from erythrocyte membranes. BBA - Biomembranes. 1981;643(3):509–18.

- Burger SP, Fujii T, Hanahan DJ. Stability of the Bovine Erythrocyte Membrane. Release of Enzymes and Lipid Components. Biochemistry. 1968;7(10):3682–700.

- Miglio A, Maslanka M, Di Tommaso M, Rocconi F, Nemkov T, Buehler PW, et al. ZOOMICS : comparative metabolomics of red blood cells from dogs, cows, horses and donkeys during refrigerated storage for up to 42 days. Blood Transfusion. 2023 Jul 1;21(4):314–26.

- Magnani M, Piatti E, Dachà M, Fornaini G. Comparative studies of glucose metabolism on mammals’ red blood cells. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Comparative Biochemistry. 1980 Jan;67(1):139–42.

- Hyun Dju Kim, McManus TJ. Studies on the energy metabolism of pig red cells. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects. 1971 Jan;230(1):1–11.

- Young J, Paterson A, Henderson J. Nucleoside transport and metabolism in erythrocytes from the Yucatan miniature pig. Evidence that inosine functions as an in vivo energy substrate. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects. 1985 Oct 17;842(2–3):214–24.

- Condo SG, Corda M, Sanna MT, Pellegrini MG, Ruitz MP, Castagnola M, et al. Molecular basis of low-temperature sensitivity in pig hemoglobins. Eur J Biochem. 1992;209(2):773–6.

- Tellone E, Russo A, Giardina B, Galtieri A, Ficarra S. Metabolic Effects of Endogenous and Exogenous Heterotropic Hemoglobin Modulators on Anion Transport: The Case of Pig Erythrocytes. OAlib. 2015;02(10):1–11.

- Fink, KD. Microfluidic Analysis of Vertebrate Red Blood Cell Characteristics. [Berkeley]: University of California; 2016.

- Orr A, Gualdieri R, Cossette ML, Shafer ABA, Stotesbury T. Whole bovine blood use in forensic research: Sample preparation and storage considerations. Science and Justice. 2021;61(3):214–20.

- Li G, He H, Yan H, Zhao Q, Yin D. Does carbonyl stress cause increased blood viscosity during storage? Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2010;44(2):145–54.

- Windberger U, Sparer A, Huber J. Cow Blood - A Superior Storage Option in Forensics? Heliyon. 2023;9:e14296.

- Noirez, L. Probing Submillimeter Dynamics to Access Static Shear Elasticity from Polymer Melts to Molecular Fluids. In: Palsule S, editor. Polymers and Polymeric Composites: A Reference Series. Springer, Germany; 2020. p. 1–23.

- Sartorelli P, Paltrinieri S, Agnes F, Baglioni T. Role of inosine in prevention of methaemoglobinaemia in the pig: In vitro studies. Journal of Veterinary Medicine Series A: Physiology Pathology Clinical Medicine. 1996;43(8):489–93.

- Larsson L, Sandgren P, Ohlsson S, Derving J, Friis-Christensen T, Daggert F, et al. Non-phthalate plasticizer DEHT preserves adequate blood component quality during storage in PVC blood bags. Vox Sang. 2021 Jan 1;116(1):60–70.

- Baier D, Müller T, Mohr T, Windberger U. Red Blood Cell Stiffness and Adhesion Are Species-Specific Properties Strongly Affected by Temperature and Medium Changes in Single Cell Force Spectroscopy. Molecules [Internet]. 2021;26:2771. [CrossRef]

- Woźniak MJ, Qureshi S, Sullo N, Dott W, Cardigan R, Wiltshire M, et al. A Comparison of Red Cell Rejuvenation versus Mechanical Washing for the Prevention of Transfusion-Associated Organ Injury in Swine. Anesthesiology. 2018 Feb 1;128(2):375–85.

| Day 0 cow | Day 30 cow | cow | Day 0 pig |

Day 30 pig | pig | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBC count (T/L) | 4.96 ± 0.7 | 4.75 ± 0.7 | -4.2% | 7.33 ± 0.4 | 6.86 ± 0.4** | -6.4% |

| WBC count (G/L) | 6.01 ± 1.1 | 3.4 ± 1.0* | -43% | 15.5 ± 3.3 | 8.3 ± 3.9** | -44% |

| PLT count (G/L) | 266 ± 77 | 198 ± 67 | -25% | 262 ± 43 | 200 ± 63** | -25% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).