1. Introduction

Lubricants consist of a base oil mixed with variable amounts of additives, the type and concentration of which depend on the specific application. Thus, in terms of the sustainability relevance, i.e., renewability, biodegradability, or recyclability, the base oil component is the main critical consideration factor [

1]. Nowadays, hydrocarbon-based polyalphaolefins (PAOs) are used as high-performing synthetic lubricant base oils due to their excellent properties such as thermo-oxidative and hydrolytic stability in a wide range of viscosity classes. Since they are commonly derived from petroleum or natural gas by oligomerization of linear alphaolefins, they are not classified as renewable and do not generally perform as “readily biodegradable” [2, 3, 4]. The lower viscosity of PAO 2 and PAO 4 are the most easily biodegradable ones in aquatic environments and although they are readily biodegradable, they have an inherent ability to undergo primary biodegradation [5, 6].

There is a developmental shift toward lower-viscosity oils, especially in the automotive market. New fuel economy targets low viscosity grades, as higher viscosity lubricants tend to cause fluid friction buildup contributing to a higher fuel consumption [

7]. Development focuses on viscosity 5W-30 (9-13 mm²/s at 100 °C) down to low viscosity 0W-20 (7-9 mm²/s at 100 °C) and even to grades such as 0W-16 (6-8 mm²/s at 100 °C) [8, 9]. For electric vehicles, synthetic PAO or sustainable esters (1-7 mm²/s at 100 °C) are in focus due to higher efficiency in the electric drive unit. These oils should have pour points below -30 °C and neutralization numbers of less than 0.3 mg KOH/g oil [10, 11]. Consequently, the use of high-performance additives is crucial to maintain consistent performance in lower-viscosity oils such as PAO 4 and squalane (~4 mm²/s at 100 °C). The structure of PAO 4 is inherently branched with long side chains and it is a low-viscosity oil type applied in demanding automotive and industrial lubricant applications [

12]; while squalane prepared by hydrogenation of squalene is more branched with methyl side chains, shows good lubricating properties, is commonly used in the cosmetics industry as a skincare product [2, 13].

A sustainable lubricant must minimize its environmental impact on soil, water, air, and biodiversity while guaranteeing a performance equal to or better than that of conventional fossil-based lubricants. Furthermore, to demonstrate renewability, bio-lubricants must contain min. 25 % biobased carbon content in the final product in accordance with EN 16807 [

14], as stipulated in the EU Ecolabel criteria [

15]. The Ecolabel criteria were introduced to streamline the objective certification process for sustainable and environmentally benign lubricants. The related LuSC (Lubricant Substance Classification) list [

16] was introduced to streamline the EU Ecolabel certification process for lubricants, provides a regularly updated inventory of lubricant components that comply with the Ecolabel criteria [

17]. The strategy is that environmentally acceptable lubricants (EALs), such as those defined in the Vessel General Permit (VGP), replace non-sustainable, harmful mineral oils [

18]. The first biobased lubricant components that entered the market were made of triglycerides from vegetables [

19]. These plant-based oils come with multiple benefits concerning their sustainability and biodegradability. Still, they also have the significant drawback of causing a food-chain conflict, directly using edible oils or indirectly using land for non-edible crop production [1, 20]. There is a legislation push towards sustainable lubricant formulations that do not interfere with the food chain; for example, RED III (Renewable Energy Directive recast) highlights the need for limited production of biofuels from cereal, starch-rich crops, oil crops, and sugar sources, referred to as advanced biofuels, to mitigate land-use change and its impacts. By 2020, a cap of a maximum of 7 % of the total energy consumed in the transport sector in a Member State was applied for biofuels and bioliquids produced from food and feed crops, and it shall phase out via a gradual decrease to 0 % by 2030. Additionally, the share of advanced biofuels in the transport sector shall surpass 5.5 %, with at least 1 % being from Renewable Fuels of Non-Biological Origin (RFNBOs) by 2030, e.g., by using renewable electricity to convert carbon dioxide (CO

2) and water (H

2O) into hydrocarbons through chemical reactions like the Fisher-Tropsch synthesis [21, 22].

A seamless transition from non-bio-derived lubricants to more sustainable options is crucial for resource conversation and can be achieved by incorporating drop-in replacement components into existing formulations. The terminus “drop-in” originates in the field of fuels, referring to bio-derived materials blended into the conventional, mineral-based processing pathway at an early stage, given their functional and chemical equivalence and using the benefit of well-established markets [

23]. The bio-derived squalane has the potential to be a drop-in replacement for low-viscosity synthetic PAO 4 substitution.

Squalane is a saturated, acyclic, branched C30 hydrocarbon, a more stable version of the naturally occurring unsaturated squalene. Squalene, a triterpene traditionally sourced from shark livers, can also be found in plant-based sources, including olives, amaranth seed, rice bran, palm, soy, or sunflower oil. Squalane can be processed from squalene hydrogenation, e.g., after collecting it from acid oil, being olive oil’s processing residue (phytosqualane), or from the biotechnological process of fermentation with Saccharomyces cerevisiae into farnesene (C15H24), followed by its dimerization into squalene and hydrogenation to give saturated squalane [24, 25].

Squalane was used previously as a model compound for the simulation of nonpolar lubricant oil systems with well-defined density and viscosity [

26]. Recent studies include, e.g., polarity-dependent viscosity behavior combining experimental and computational methods [

27], thermophysical properties (viscosity, density, self-diffusion coefficient) prediction at extreme conditions of 1-decene trimer (such as PAO 4) and squalane using different force fields [

28], elastohydrodynamic lubrication (EHL) comparing measured traction curves or using predictive simulation models in rolling/sliding tribometer rigs discussing the complex rheological behavior of lubricants under extreme conditions [29, 30, 31, 32], etc.

To evaluate the stability of lubricant base oils and fully formulated lubricants, a large number of standardized methods are available, especially to determine the resistance against oxidation. Therefore, the sample is brought into contact with oxygen by passing gas through it, such as in the turbine oil oxidation stability test (TOST) prescribed in ASTM D943 [

33], or in a closed reactor at elevated pressure, such as the rotary pressurized vessel oxidation test (RPVOT) described in ASTM D2272 [

34]. Oxidation stability is assessed by the quantity of oxidation products (typically change in acidity), oxygen absorption (pressure curve over time), viscosity changes, or formation of sludge (weight of deposits or filtered residues). However, advanced analytical methods are required to understand the degradation behavior of lubricants when exposed to oxygen to improve base oil stabilities and predict the consequences on base oil properties and performance. Gas chromatography coupled with mass spectroscopy (GC-MS) allows the separation of complex mixtures such as lubricants and the identification of degradation products, e.g., [

35]. While data on oxidation stability of conventional base oils is well available from oil manufacturers, only a few studies are known about squalane. Besides the development of a kinetic model of squalane oxidation, GC-MS analyses revealed light hydrocarbons, alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, acids, and esters as degradation products [

36]. The effect of biodiesel on the autoxidation of engine oil base fluids was mimicked by a model system of methyl linoleate and squalane using GC-MS to determine the main degradation mechanisms [

37].

This publication reports on a study on the characterization of squalane product streams for their usability as high-performing, well-defined, sustainable base oil benchmarked against the established synthetic PAO 4. For this purpose, artificial oil alteration was performed to examine the oxidative stability of both base oils and to determine the impact of raw materials and production processes on the performance and properties. In addition, major degradation products from artificially altered oil samples were identified using mass spectrometry techniques to understand their impact on the conventional physicochemical properties.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Base Oils

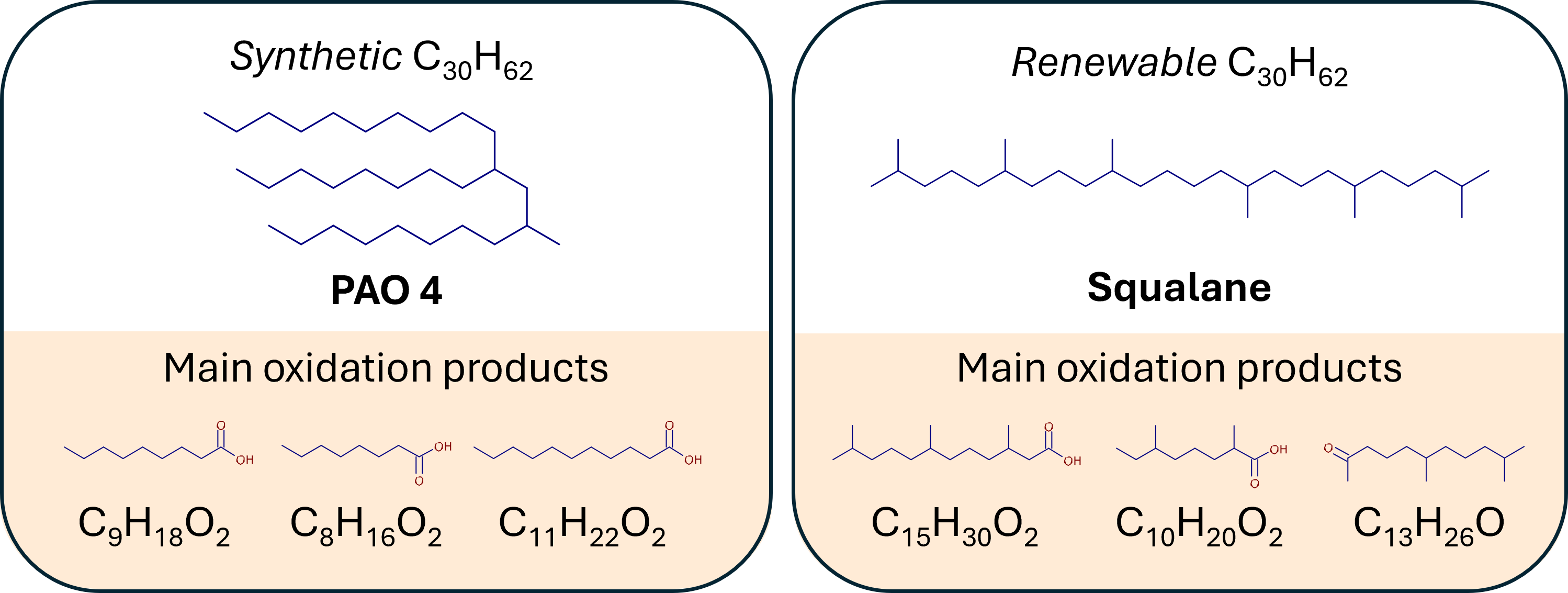

A selection of three squalanes (two from biotechnological origin and one from olive oil waste processing) and one PAO 4 (derived from crude oil) was investigated. As shown in

Figure 1 and discussed in

Table 1, PAO 4 is mainly a 1-decene trimer that results from the oligomerization of a 1-decene linear alphaolefin and is then subjected to hydrogenation. Squalane is a natural structural isomer to PAO 4 with similar viscosity and a larger number of tertiary carbons due to a higher branching degree. Both structures have a sum formula of C

30H

62 and are composed of saturated hydrocarbon-based molecules imposing higher thermo-oxidative stability, leading to the suitability of PAO base oils for demanding high-temperature applications.

2.2. Oxidation Stability by Artificial Oil Alteration

To benchmark the selected squalanes against PAO 4, accelerated simulation of lubricants’ thermo-oxidative degradation was conducted at the laboratory scale. This process referred to as artificial alteration or artificial aging is distinct from real-world aging in the application, where additional factors beyond constant temperature come into play. In this study, oxidation stability tests of the base oils were performed based on the method described in detail in [

40]. This method is adapted from the rotary pressurized vessel oxidation test (RPVOT) standard ASTM D2272 – 14a Method B [

34], utilizing a TANNAS QUANTUM® Oxidation Tester (Tannas Co. & King Refrigeration Inc., Michigan, USA). The modified reaction cell and parameters enable clear differentiation between the samples and facilitate intermediate sampling. The magnetic cup assembly and sample beaker were replaced with a custom-made polytetrafluorethylene (PTFE) sample holder, which fits into the pressure chamber of the device with minimal dead volume. The sample is stirred with a magnetic stirrer to assist oxidation by utilizing the device’s original drive and magnetic coupling. The sampling kit, also supplied by TANNAS, was further modified to reduce dead volume and to enable sampling even when the amount of liquid in the reaction cell is small.

A weighted base oil sample was inserted into the PTFE sample holder and, subsequently, the pressure chamber. The system was closed and flushed with the reaction gas three times to remove all residual air, and then the oxygen pressure was set to 2 bar over the atmospheric pressure. The pressure was monitored at room temperature for 15 min to verify the leak proofness, then the reaction temperature was set by rapid heating up to 120 °C. During the alteration procedure, small sample aliquots (approx. 1 g) were extracted via the sampling kit every hour (starting from the second hour) for further. Pressure and temperature were continuously monitored and recorded at a 5 s resolution.

Table 2 summarizes the corresponding test parameters.

Several standards utilize the monitored pressure decrease to determine oxidation stability, such as ASTM D2272 [

34] and DIN EN 16091 [

41]. Generally, once oxygen undergoes a chemical reaction with the oil sample, it ceases to exert pressure in the gas phase, resulting in a lower overall pressure recorded. Accordingly, the following related parameters were evaluated:

The alteration procedures were stopped at TOT, and the reaction cell was cooled to room temperature to prevent further degradation reactions and to enable the recondensation of any volatiles formed. Subsequently, the final samples were collected and documented for analysis.

2.3. Conventional Lubricant Physicochemical Analyses

Conventional physicochemical parameters of fresh, intermediate, and final samples were determined to generate a basic understanding of thermo-oxidative degradation evolution during artificial alteration. The following information was obtained for conventional characterization of degradation extent and its impact on physicochemical properties:

-

Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra of fresh, intermediate and final oil samples were recorded and compared to the original samples (on the difference spectra approach) within a spectral range of 4000-500 cm-1 (Tensor 27, Bruker Optik GmbH, Germany),

Neutralization number (NN) of the fresh and final oil samples (double determination) according to DIN 51558 [

43] by titration with color-indication with p-naphtholbenzein using a 0.05 M potassium hydroxide (≥ 85.0%, Supelco, Germany) solution in 2-propanol.

Water content by indirect Karl-Fisher (KF) titration using a KF Coulometer and an Oven Sample Processor (Metrohm AG, Herisau, Switzerland) according to DIN 51777 [

44] (double determination) of the fresh and final oil samples.

Kinematic viscosity and density of the fresh and final oil samples were determined by an SVM 3000 Stabinger viscometer (Anton Paar GmbH, Graz, Austria). The applied method is based on ASTM D7042-21 [

45], but the temperature range was extended from -40 °C to +100 °C to give a better overview of the potential applicability. The viscosity index (VI) was calculated based on the kinematic viscosity data according to ASTM D2270 [

46].

Pour point (PP) according to DIN ISO 3016 [

47] determined for the fresh and altered oil samples using a mini pour point analyzer (PAC ISL MPP 5Gs, Texas, USA).

Simulated distillation was used for analyzing the boiling range distribution of fresh and final altered oil samples by gas chromatography (GC) coupled to a flame ionization detector (FID) according to ASTM 6352 [

48] using a TG1MS (15 m x 0.25 mm x 0.25 µm, Thermo Fisher Scientific; Waltham, MA, USA) separation column.

2.4. Advanced Chemical Analyses for in-Depth Characterization

2.4.1. Gas Chromatography Coupled with Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS)

Oil samples were examined by a Thermo Trace GC Ultra (Thermo Fisher, Bremen, Germany) gas chromatograph coupled in parallel to an FID and a Quantum XLS triple quadrupole mass spectrometer. Two different methods were conducted: Boiling range distribution by simulated distillation (GC-FID, see chapter 2.3) and the identification of degradation products (GC-MS, see next paragraphs).

For compound identification, fresh, intermediate, and final oil samples were analyzed by GC-MS using a TG5MS fused silica column (30 m x 0.25 mm x 0.25 µm, Thermo Fisher Scientific; Waltham, MA, USA). Dichloromethane solvent (DCM; ≥ 99.9 %; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was used for sample dilution and N,O-Bis-(trimethylsilyl)trifluoro-acetamide with trimethylchlorosilane (BSTFA + TMCS; 99 %; Sigma-Aldrich, Switzerland) was used as the derivatization agent.

Samples were diluted to 4 wt% in DCM and BSTFA at 18 wt% was added as a silylation agent. The sample was silylated for one hour at 70 °C and subsequently, 1 µL of the sample was injected at 300 °C with 25:1 split ratio. Constant flow mode was used at 2 ml/min of helium carrier gas. The initial oven temperature was kept for 1 min at 60 °C, followed by a 10 °C/min ramp to 300 °C, and held for 25 minutes, resulting in a total run time of 50 min. The temperature of the transfer line from the GC to MS was kept at 250 °C. The MS was equipped with an electron impact (EI) ionization source (70 eV) with a source temperature set to 200 °C, operated in a positive ionization mode. Positive ions were generated by an electron emission current of 60 µA, and analytes were detected after a solvent cutoff time of 4.5 min within a mass-to-charge (m/z) range of m/z 40 to 650 and a scan time of 0.2 s. Data was acquired with Thermo Xcalibur 4.4.16.14 (Thermo Fisher) and evaluated with FreeStyle™ 1.8 SP2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Compounds were identified based on a similarity search against the NIST20 library.

2.4.2. High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HR-MS)

The applied method is described in detail in [

49] and briefly summarized below. The equipment used was an LTQ Orbitrap XL hybrid tandem high-resolution mass spectrometer (Orbitrap-MS) (ThermoFisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany). Sample solutions were prepared in chloroform:methanol (7:3) (chloroform: ≥ 99.9%, Supelco, MA, USA; methanol: ≥ 99.9%; Supelco, Darmstadt, Germany) solvent with a dilution factor of 1:1000. The sample solutions were injected via automatized direct infusion into the IonMax API ion source, applying electrospray ionization (ESI) technique in positive and negative ionization mode and using nitrogen as sheath gas. Fragmentation of the resulting single-charge ions was performed via low-energy collision-induced dissociation (CID) in the linear ion trap of the instrument via helium as both buffer and collision gas. The resulting mass spectra were obtained within a range of m/z 50-800 by the high-resolution orbitrap mass analyzer (R = 30,000 FWHM at m/z 400).

Xcalibur version 2.0.7 and Mass Frontier version 6.0 software were used for the evaluation (both ThermoFisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany). The presented m/z refers to single-charged species. Hence, m/z is equivalent to the respective molecular mass. The reported relative abundances are based on the total ion current (TIC) acquisition, where the highest ion signal in a mass spectrum corresponds to 100 % of relative abundance.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 Fresh Sample Compound Characterization

Table 3 shows the summary of the determined conventional lubricant properties. All samples show a very low comparable acid level (NN) and water content, corresponding to the neat (additive-free) hydrocarbons used as lubricant base oils. Olive-SQ shows a higher pour point compared to all other base oils and has a significantly higher viscosity at negative temperatures.

Due to strong similarities of Sugar-SQa and Sugar-SQb in physicochemical properties and structural characterization (data not shown), a reduction of the matrix was conducted, and degradation behavior was studied on Sugar-SQa only.

3.2. Thermo-Oxidative Stability and Conventional Oil Analyses

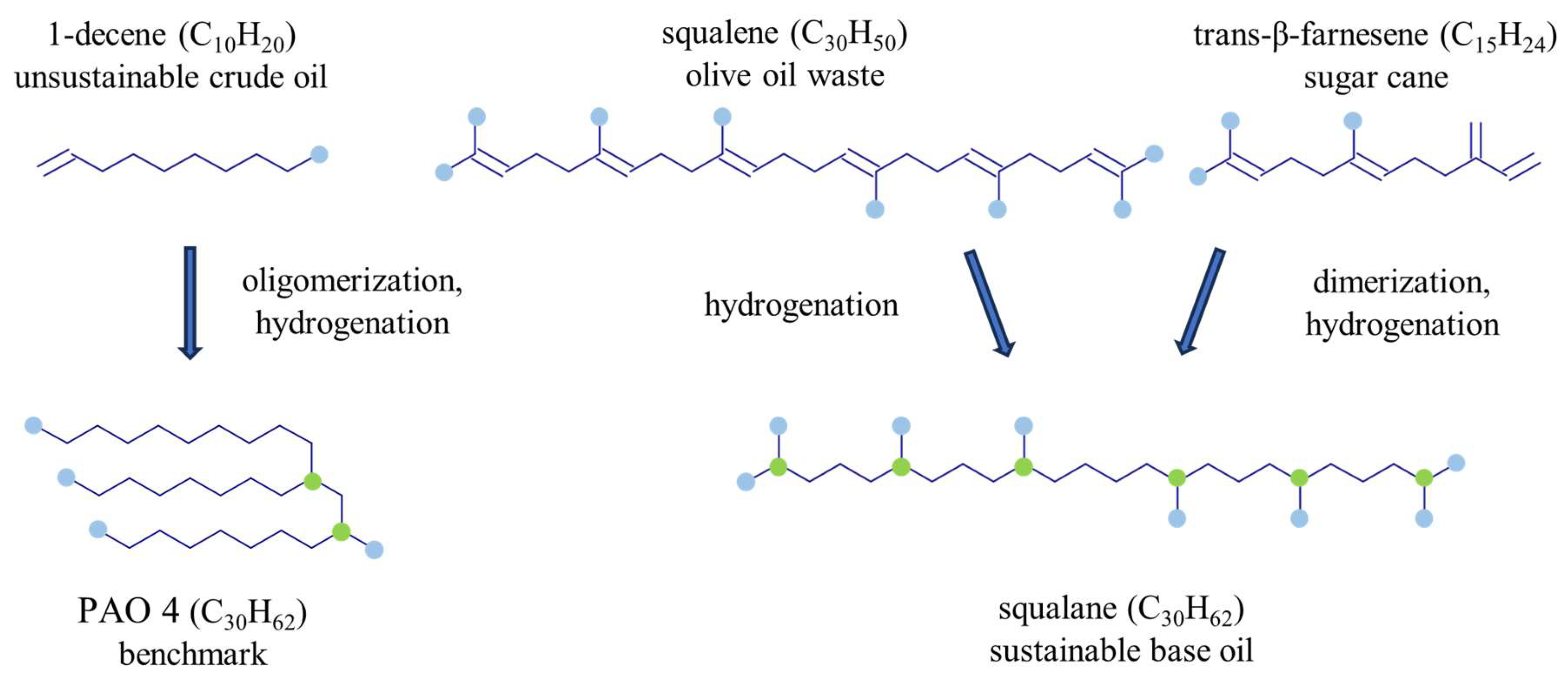

Figure 2 (a) shows the FT-IR absorbance spectra of the fresh base oils. The wavelength range from 3000-2800 cm

-1 shows the presence of C-H groups (stretching) aligning with the vibrations around ~1450 cm

-1 (scissoring), ~1380 cm

-1 (methyl rocking), and ~730 cm

-1 (rocking; long-chain alkanes), well visible in all base oil types. The FT-IR difference spectra of the final altered samples are depicted in

Figure 2 (b). An appearance of C = O carbonylic stretching vibrations in the range of 1670-1770 cm

-1 is visible, indicating oxidation-derived carboxylic acids and ketones, and is in alignment with the higher neutralization number (see discussion to Figure 4). The increase in the range of 3600-3150 cm

-1 for O-H stretching can be determined, which is slightly higher for the squalane base oils than for PAO 4, correlating to the increase in the quantified water content (displayed in Figure 4 (f)).

The trend of degradation product buildup is shown in

Figure S1-S3 for PAO 4, Sugar-SQa, and Olive-SQ, respectively, taken from the intermediate and final oil samples and their FT-IR difference spectra to the fresh oil spectra.

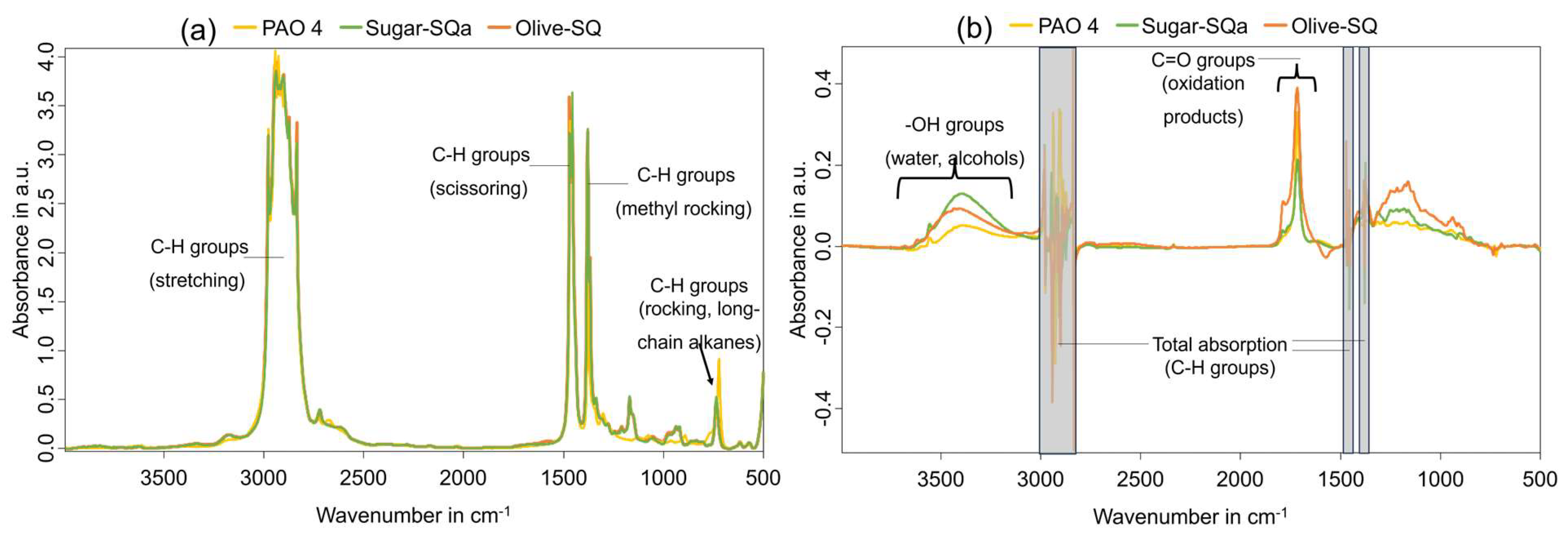

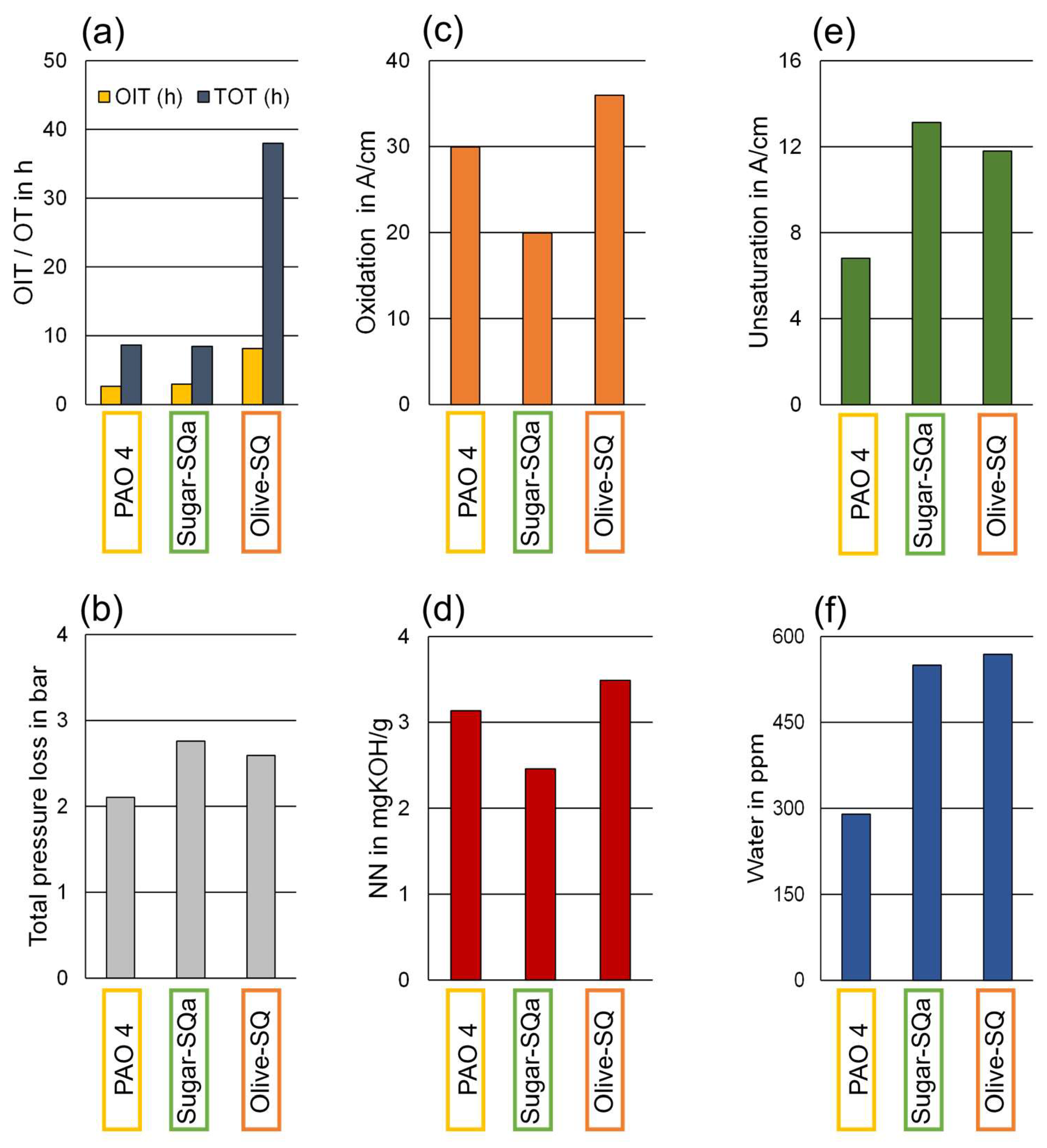

Figure 3 (a) illustrates the pressure curves of the three base oils. The Sugar-SQa showed a similar TOT to the PAO 4. However, the total decrease in pressure was more pronounced in the case of the Sugar-SQa. Comparatively, the Olive-SQ displayed superior oxidation stability, characterized by a long initial phase of relatively constant pressure, where PAO 4 and Sugar-SQa suffered already considerable oxidation, and a slow decrease of pressure resulting in a total alteration duration of 38 hours compared to about 8.5 h in the case of PAO 4 and Sugar-SQa. As the sampling intervals were kept consistent during the alterations of the three base oils, sampling of Olive-SQ was not optimal due to the unexpectedly slow oxidation progress.

The resulting oxidation corresponding to C=O bonds abundance and to unsaturated hydrocarbons presence based on the obtained FT-IR spectra are displayed in

Figure 3 (b) and (c), for the Sugar-SQa and the PAO 4, respectively. Oxidation of hydrocarbons generally yields alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, carboxylic acids, ethers, esters, unsaturated hydrocarbons, carbon dioxide, and water through various radical reactions. The PAO 4 base oil is characterized by a higher abundance of oxygen-containing products than the Sugar-SQa, despite the lower pressure decrease (lower oxygen consumption). At first glance, this seems contradictory but can be explained by the different abundance of unsaturated hydrocarbons (FT-IR) in

Figure 3 (c), which are higher in the Sugar-SQa compared to the PAO 4. The wavenumber selected for evaluation represents isobutylene and polyisobutylene compounds, i.e., tertiary unsaturated carbon atoms. The bond dissociation energy (BDE) for carbon-hydrogen is in the order of C(tertiary)-H < C(secondary)-H < C(primary)-H. Therefore, tertiary carbons are more prone to hydrogen release compared to secondary and primary carbons, hence, to form free radicals during the autoxidation process [50, 51]. Consequently, an alpha-hydrogen elimination from a tertiary-carbon radical takes place, which yields an alkene and water. Obviously, in the case of the Sugar-SQa, this reaction pathway is more prominent than the one leading to the oxygen-containing species, at least compared to the PAO 4. This interpretation is supported by the fact that squalane generally contains more tertiary carbons than PAO.

Since the intermediary samples of the Olive-SQ were taken at an early stage with minimal oxygen pressure loss, no pronounced oxidation or accumulation of unsaturated hydrocarbons was detected. Consequently, the properties of Olive-SQ samples are not displayed in

Figure 3 (b) and (c) (see

Figure 4 for the comparison to the final oil samples).

Figure 3 (d) displays the photographic documentation of the final oil samples at the end of the alteration procedures, still in the reaction cell. Sugar-SQa and PAO 4 show only minimal discoloration and are clear; whereas Olive-SQ has prominent yellow color. None of the final oil samples contained sludge or deposit. The findings regarding pressure decline, oxidation, unsaturation, and discoloration demonstrate that PAO and squalanes form different degradation products during oxidation.

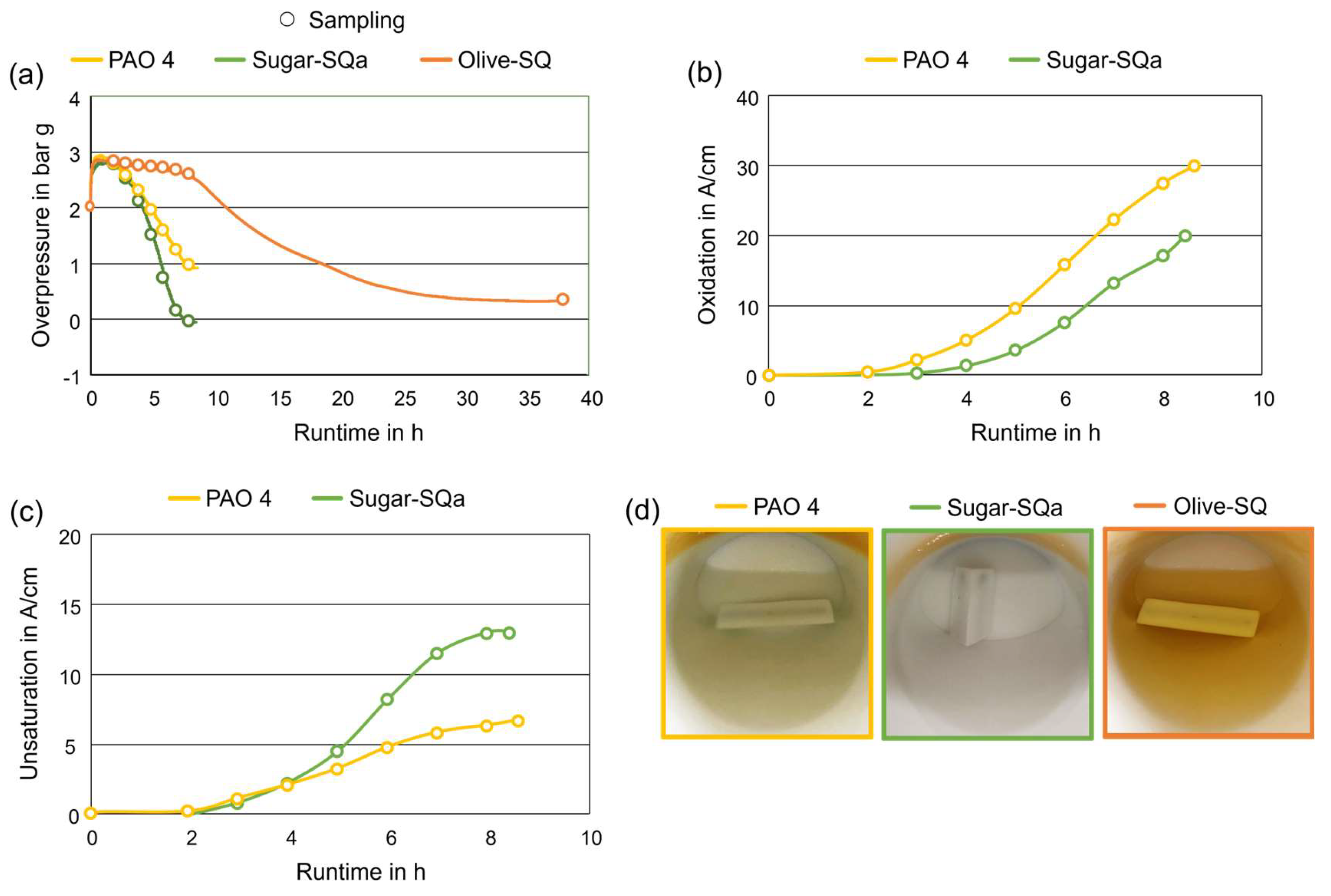

Figure 4 gives an overview of the oxidation stability results and the relevant parameters determined in the final oil samples. All fresh samples displayed a negligible NN (< 0.05 mgKOH/g) and water content (< 20 ppm) and are not displayed (see

Table 3). As mentioned, Sugar-SQa and PAO 4 display similar oxidation stability, while Olive-SQ greatly exceeds those base oil samples in OIT and TOT.

Figure 4 (b) shows the total pressure loss during the oxidation stability tests. The two squalane samples display a similar pressure loss, while the PAO 4 seems to consume less oxygen in general. Oxidation and NN are displayed in

Figure 4 (c) and (d). Here, NN is a measure for organic acids as typical oxidation products [

52]. Accordingly, there is a clear correlation between the two parameters. Sugar-SQa displays the lowest oxidation and NN in the final sample, while both parameters are higher in the PAO 4 and are more elevated in Olive-SQ. Levels of unsaturated hydrocarbons and water are shown in

Figure 4 (e) and (f). As discussed earlier, the variation of these parameters might be interpreted by differences in oxidation reaction pathways related to the tertiary carbon atoms, the abundance of which is very ordinary in squalane samples. The final samples of the oxidation stability tests show a correlation between these two parameters: unsaturated hydrocarbons are more abundant in the final Sugar-SQa and Olive-SQ samples and the water content has approximately double amount compared to PAO 4. These findings suggest that squalanes are more susceptible to the degradation mechanism leading to unsaturation than polyalphaolefins.

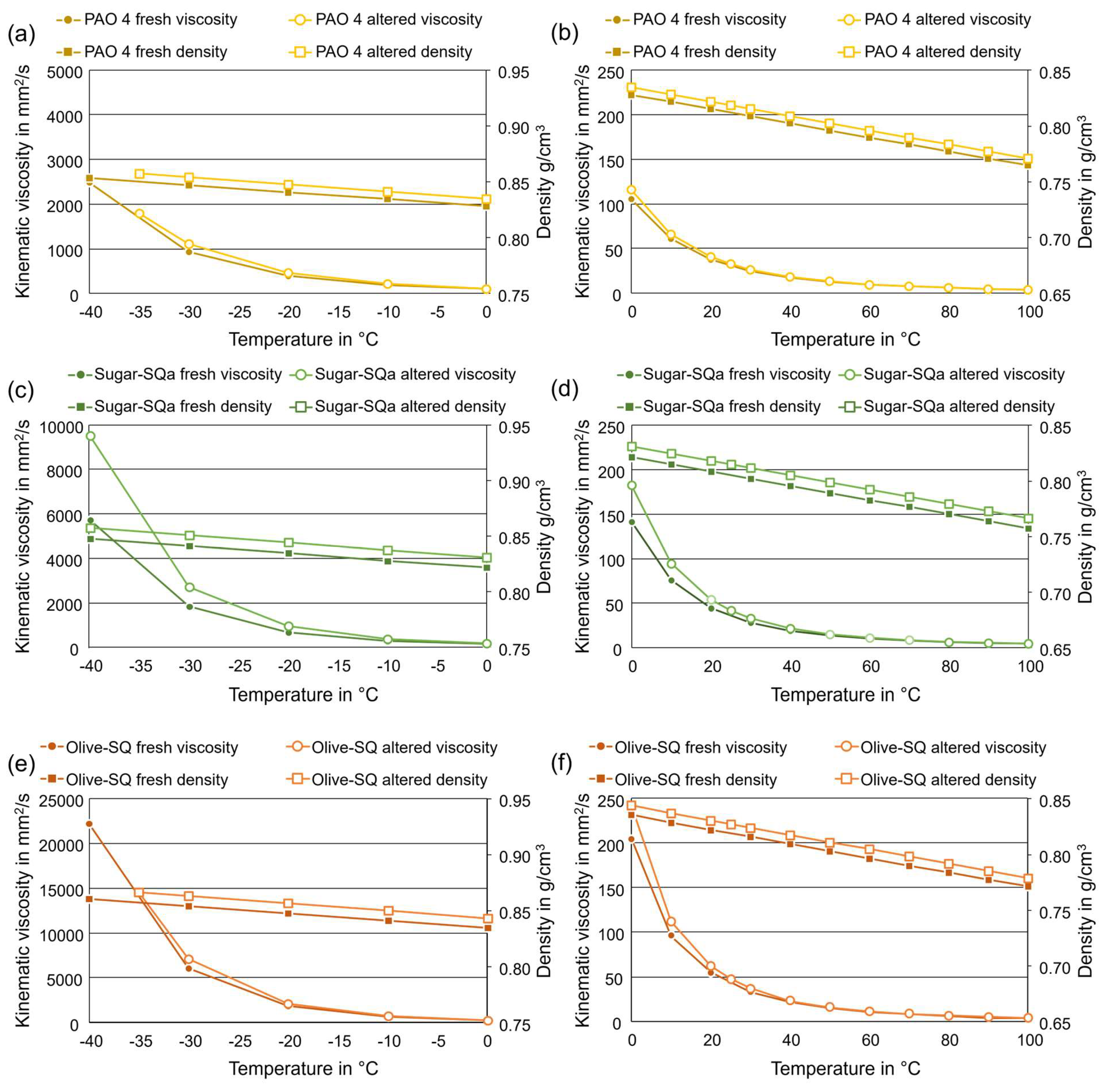

Figure 5 gives an overview of kinematic viscosity and density changes over a temperature range of -40 °C to +100 °C. The low and high-temperature data are presented in separate figures to account for very high viscosities sometimes measured close to -40 °C. PAO 4 in

Figure 5 (a) and (b) generally shows comparable viscosity and density before and after artificial alteration (except below -30 °C). Other than some minor increase in density and viscosity at low temperatures, degradation does not seem to affect these properties significantly. The measurement of the PAO 4 altered sample at -40 °C was not possible because the value was outside of the measuring range of the instrument.

Sugar-SQa in

Figure 5 (c) and (d) exhibits elevated viscosity and density after artificial alteration. The differences in viscosity to the fresh oil sample are mostly present in the temperature range below –30 °C but also measurable up to +30 °C. Meanwhile, the high-temperature viscosity is mostly similar. Comparatively, the density shows a constant offset, which is not dependent on the temperature.

Olive-SQ in

Figure 5 (e) and (f) shows some increase in viscosity or density due to artificial alteration. An accurate measurement of the viscosity of the altered oil sample was also not possible at -40 °C. Overall, kinematic viscosity shows significant deviations between fresh and altered oil samples at temperatures below -30 °C.

3.3. GC Characterization of Fresh and Altered Base Oil Samples

3.3.1. Simulated Distillation

The simulated distillation via GC-FID shows the boiling range distribution of the selected base oil samples, see

Table 4 and

Figure S4. The main fraction is detected in the range from 425-450 °C, characterized by a steep increase in weight fraction. In fresh condition, the main fraction is smallest for PAO 4 (35 wt%), followed by Olive-SQ (43 wt%) and Sugar-SQa (54 wt%). PAO 4 shows a fraction of about 19 wt% at lower molecular weight (MW) and 46 wt% at higher MW (related to the C40 distillation fraction [

53]). The low MW fractions of the squalane base oils range from 19 to 25 wt%; higher molecular MW compounds sum up from 27 to 32 wt% for these samples.

During artificial alteration of PAO 4, no pronounced change in the distillation starting point (330 vs. 333 °C) is noticed. Also, the low MW fraction remains constant regardless of the compounds that disappeared or formed during alteration. A lower end point is detected (594 vs. 576 °C) pointing to the removal of high-boiling compounds during the oxidation process. However, the high MW fraction (46 vs. 50 wt%) is increased at the expense of the main fraction (35 vs. 30 wt%).

The oxidation behavior of the squalane base oils differs significantly from PAO 4. While the starting points of the distillation curves do not show a clear trend, the end point is significantly reduced after artificial alteration by 28 °C for Sugar-SQa and 48 °C for Olive-SQ, respectively. The low and high MW fractions are decreased by 1 to 10 wt%. In turn, the main fractions are significantly increased by 9 and 16 wt%.

It is noted that a direct comparison of results from simulated distillation by GC-FID with findings from GC-MS (next chapter) is not possible for several reasons: Base oil samples for simulated distillation were directly diluted in solvent without prior preparation, signal intensity is related to the amount of carbon. For GC-MS and structure identification, the oil samples were silylated to capture carboxylic acids and alcohols. Peak intensities heavily depend on the ionization properties of the individual compounds hence do not clearly indicate quantitative abundances without calibration.

3.3.2. GC-MS and Identification of Degradation Products

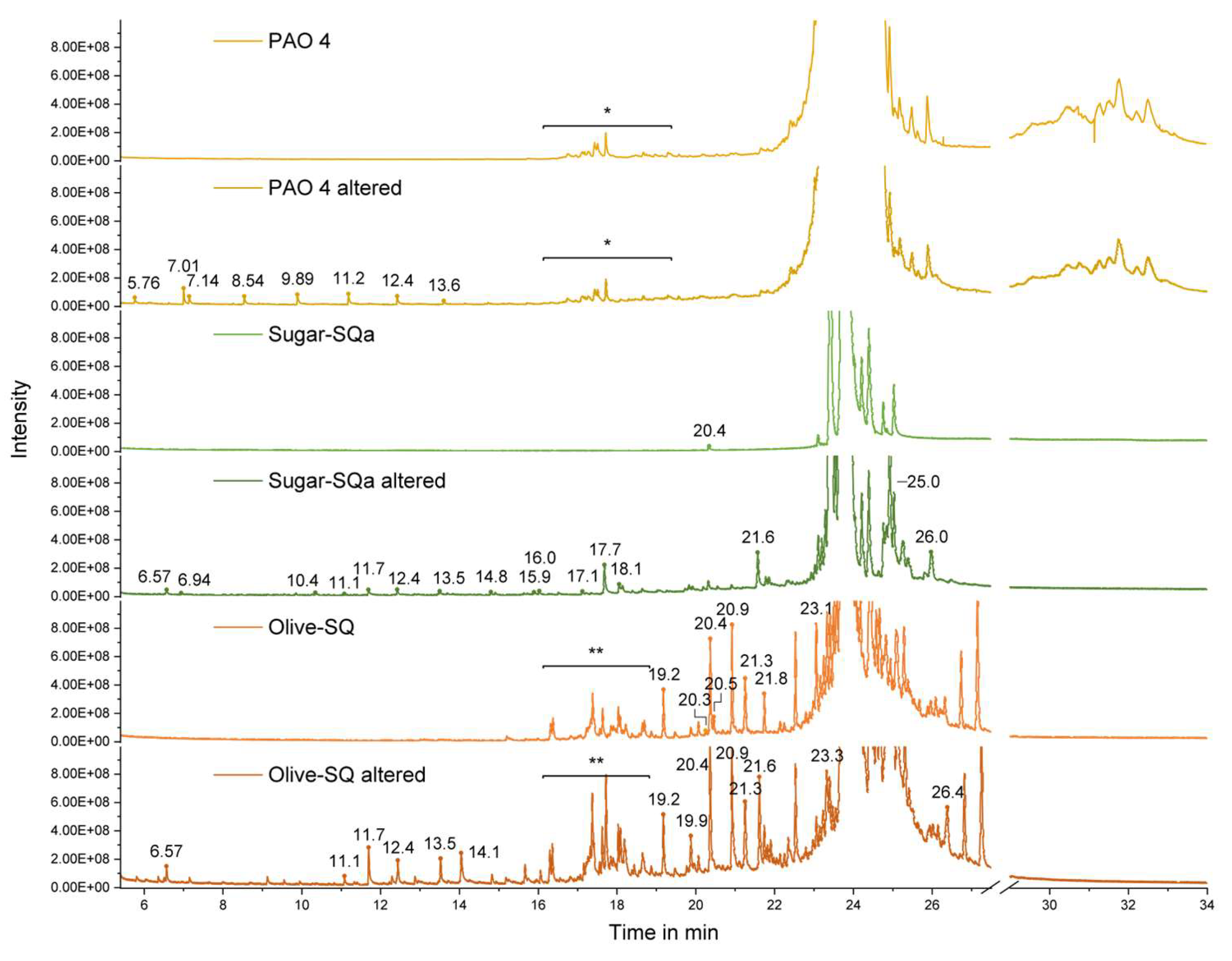

As shown in

Figure 7 for all base oil samples, some changes in the original C

30H

62 hydrocarbon peak (RT = 22-27 min) could be detected after 8.6, 8.5, and 38 h of alteration duration for PAO 4, Sugar-SQa and Olive-SQ, most pronounced for Sugar-SQa. Detailed GC-MS analyses of fresh, intermediate and final altered oil samples are displayed in

Figure S5-S8. The C30 peak, dominant in all samples, might mask other components or degradation products (e.g., ones with higher unsaturation) due to its broad peak width and intensity. Als already indicated by data from simulated distillation, peaks are visible for PAO 4 at higher retention time ranges corresponding to higher MW compounds related to the C40 distillation fraction [

53]. For Olive-SQ, more peaks appear in the lower retention time ranges (lower MW compounds). The chromatograms of fresh Sugar-SQa and Olive-SQ underpin differences in purity, the effects of which have already been revealed in different physicochemical properties and degradation behaviors.

The chromatograms of PAO 4 and squalanes show that the degradation products found in the final oil samples are different. In detail, oxidation of PAO 4 results in shorter-chain degradation products, whereas oxidative degradation of the squalanes leads to longer-chain degradation products. PAO 4 and Sugar-SQa have comparable thermo-oxidative stability, characterized by the formation of smaller amounts of degradation products. The extraordinary oxidation stability of Olive-SQ compared to Sugar-SQa is apparently due its larger amounts of impurities found beside the C30H62 main component.

In

Table 5, the newly present or significantly changing peaks with their corresponding retention times were identified by NIST library use. For the squalane base oils, branched monocarboxylic acids with the given number of carbon atoms can be expected instead of the proposed NIST assignments that target mostly linear structures. The buildup or decrease of components in intermediate samples throughout thermo-oxidative alteration is shown in

Figures S6-S8 for PAO 4, Sugar-SQa and Olive-SQ, respectively.

As already shown in

Figure 7, the main degradation products of PAO 4 are shorter-chain carboxylic acids, meaning its degradation is more pronounced, whereas longer carboxylic acids (supported by [

36]), ketones, and alcohols (also confirmed by FT-IR) were primarily found in the degradation products of Sugar-SQa and Olive-SQ due to the structural differences related to more tertiary carbon atoms and CH

3 groups. Especially C5 to C11 monocarboxylic acids formed during degradation of PAO 4. The degradation of squalane showed fewer short-chain carboxylic acids, but C6, C10 to C12, and C15 to C18 monocarboxylic acids formed. The acidic content of Olive-SQ is as high as in PAO 4 (see NN) but reached over 3 times higher OIT and over 4 times higher TOT compared to PAO 4, and this correlates to GC-MS data of higher acidic contents of Olive-SQ and PAO 4 compared to Sugar-SQa. Ketones and a significant peak of unsaturated C

35H

70 hydrocarbon are also more pronounced degradation products in Olive-SQ. Compared to PAO 4, the squalane base oils show a tendency towards dehydrogenation and an increase in unsaturation as part of their degradation mechanism.

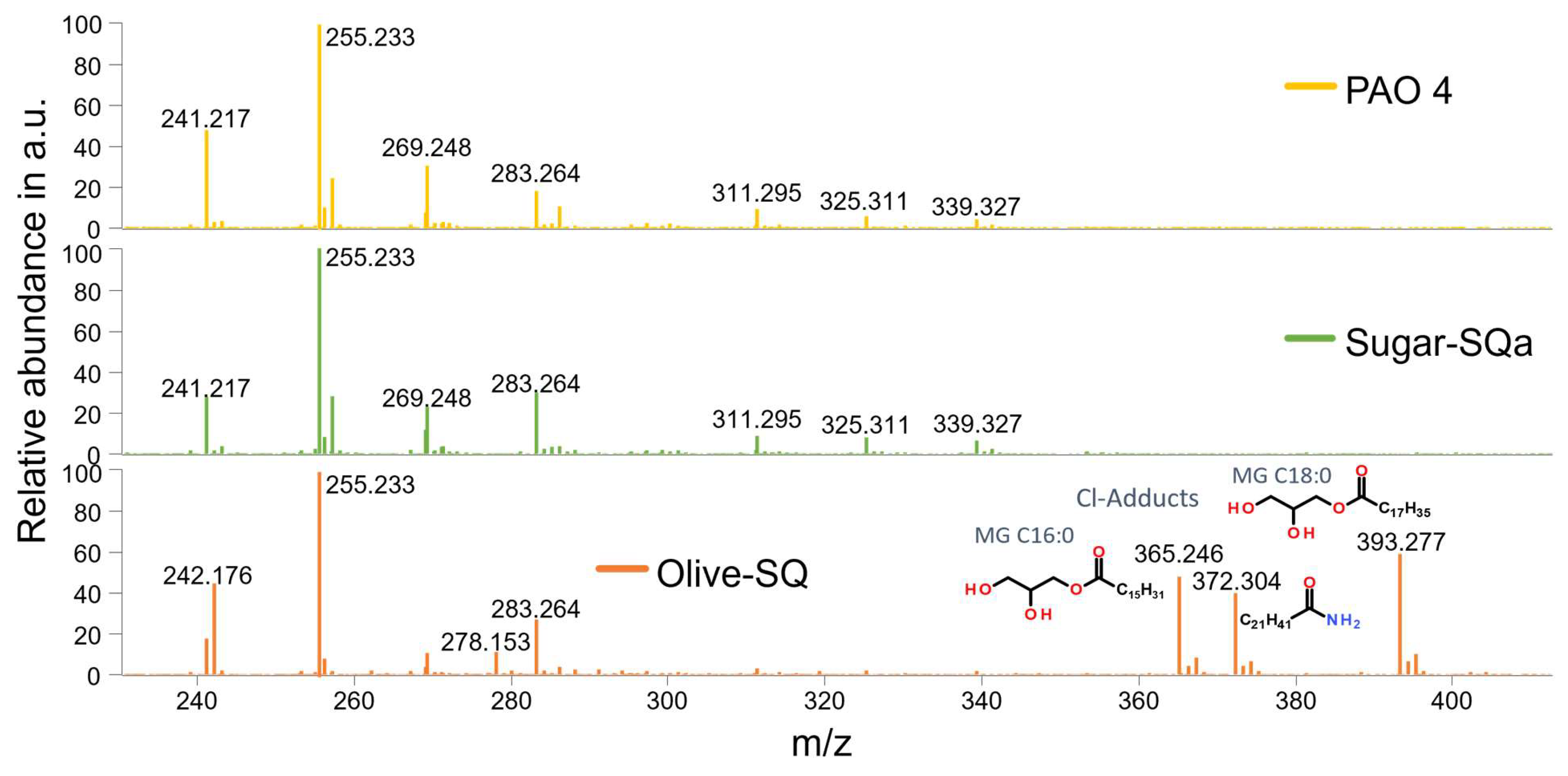

3.4. High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry

Figure 8 gives an overview of the identified heteroatom-containing hydrocarbon structures in the fresh base oil samples in ESI negative ion mode. Most notably, the Olive-SQ sample contains amidic structures that are not present in the other two base oils, namely m/z 242.176 and m/z 372.304, the latter being a chlorine adduct due to the solvent applied. Next to the amides, monoglycerides (MGs) are present in the Olive-SQ sample only (m/z 365.246 and m/z 393.277), also in the form of chlorine adducts. Both amides and MGs could be attributed to the raw materials of the Olive-SQ, which is olive waste, as amides generally can be found in olives [

54] and MGs are generally expected to be present since they are components of olive oil. Furthermore, these structures are completely depleted during artificial alteration, see

Figure S9. The amidic structures might be responsible for the elevated oxidation stability of the Olive-SQ sample compared to the other base oils, as amides generally exhibit a high free radical scavenging/antioxidative activity [

54]. The MGs in Olive-SQ most probably lead to the high pour point which makes it less suitable for applications with temperatures below 0 °C

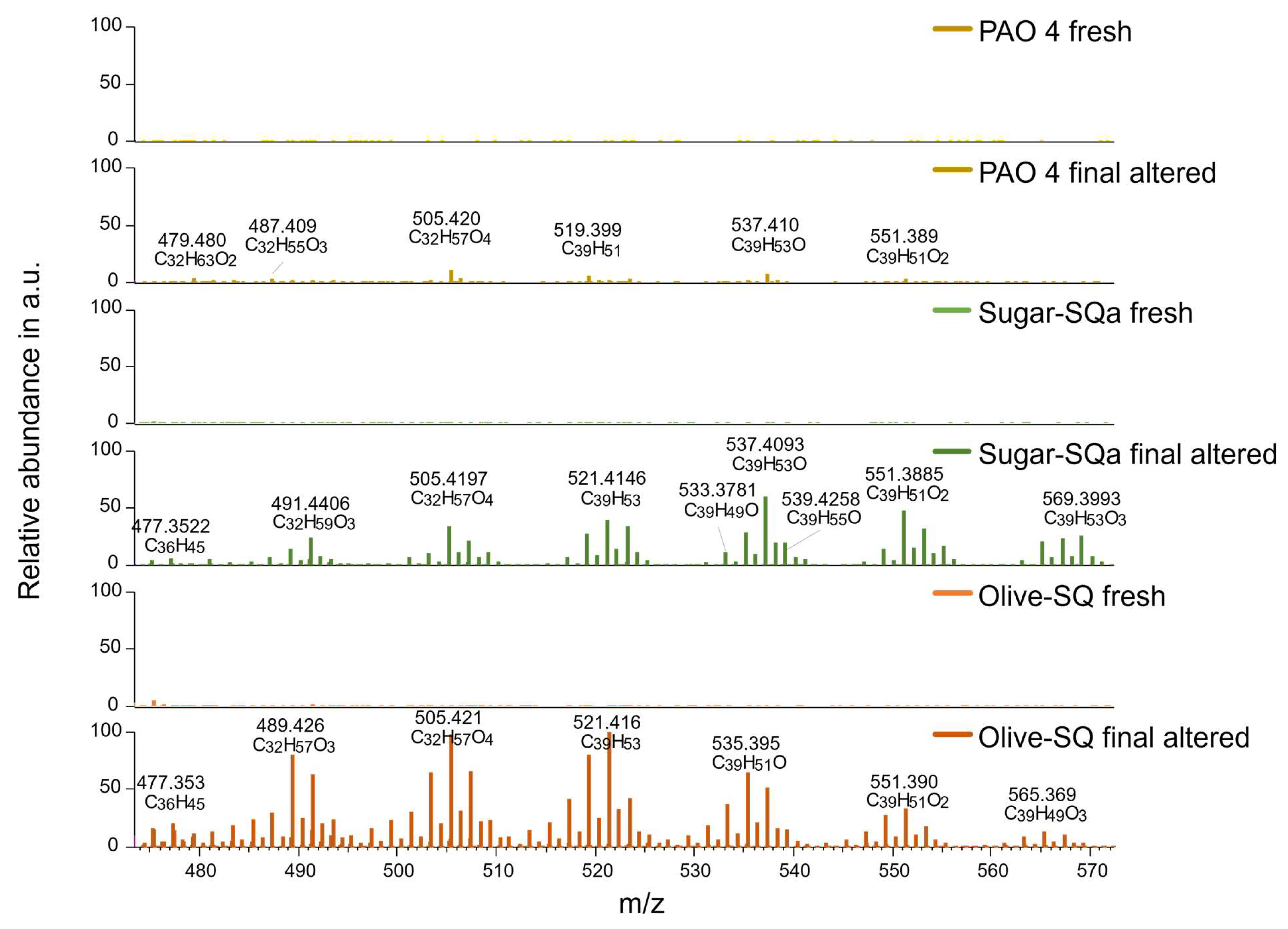

Figure 9 depicting TIC mass spectra acquired in positive ESI ion mode, gives an overview of the identified dehydrogenization products in the fresh and final oil samples. Dehydrogenation products refer to oxidized and non-oxidized hydrocarbon structures featuring unsaturated bonds. Dehydrogenation products are largely absent from all 3 fresh base oils samples. Comparatively, both final altered squalane samples contain a high number of dehydrogenation products with higher abundance, which are mostly absent in altered PAO 4. These findings correspond very well with the FT-IR results in

Figure 4 (e), where a higher abundance of unsaturated hydrocarbons in the squalane samples was already highlighted.

Summarizing, both Olive-SQ and Sugar-SQa are more susceptible to degradation pathways resulting in unsaturated hydrocarbon species in contrast to PAO 4. This might be explained by the differences in the chemical structures of the involved hydrocarbons: The squalane contains more tertiary carbon atoms (chapter 2.1), which are more prone to hydrogen abstraction [

50].

5. Conclusions

Squalane and PAO base oils were oxidatively altered at elevated temperature of 120 °C; intermediate oil samples were taken regularly in intervals of 1 h (starting after the second hour of alteration procedure) to determine the thermo-oxidative degradation process and terminate at the maximum oxygen consumption. The intermediate and final oil samples were subjected to conventional analysis, including viscosity, density, water content, neutralization number, oxidation and unsaturation, and boiling range distribution. Furthermore, the advanced chemical analyses applying GC-MS and HR-MS enabled the identification of relationships between evolved degradation products and the conventional physicochemical properties’ change as well as the correlation of thermo-oxidative stability results to differences in the composition.

Analysis via FT-IR, GC-MS, and HR-MS revealed that PAO 4 primary degradation products were shorter-chain carboxylic acids, whereas squalane base oils formed more ketones, alcohols, water, and longer-chain carboxylic acids. These differences result from structural variations, such as the number of methyl groups and tertiary carbons, rather than impurities. The presence of acids in PAO 4 indicates a more advanced hydrocarbon degradation than the ketones and water in squalane base oils. Additionally, dehydrogenation leading to unsaturated degradation products was detected as well via HR-MS for both squalane base oil samples.

Squalane base oils were evaluated against PAO 4 as a benchmark and demonstrated comparable and even enhanced thermo-oxidative stability, depending on product origin and impurities. While Sugar-SQa matched the stability of PAO 4, Olive-SQ outperformed it, indicating a prolonged lubricant lifetime, which is related to the presence of beneficial impurities, as it was the most heterogeneous base oil sample. HR-MS indicated amides in the fresh sample for both squalanes which are depleted over during artificial alteration. The amides might be responsible for the matched and elevated oxidation stability compared to PAO 4, as they exhibit a high free radical scavenging activity providing antioxidant function. The heterogeneity of the Olive-SQ containing monoglycerides may lead to a high pour point which makes it less suitable for the application with temperatures below 0 °C. Sugar-SQa exhibits a higher water content after thermo-oxidative stability test (PAO 4 < Sugar-SQa < Olive-SQ), but a lower neutralization number (Sugar-SQa < PAO 4 < Olive-SQ) compared to PAO 4, while both fresh oils have very similar properties.

Based on the conducted investigations, it appears that the sustainable Sugar-SQa could serve as a one-to-one replacement for crude oil-derived PAO 4, due to its uniform distribution, matching thermo-oxidative stability and closer rheological properties especially in the low temperature region compared to Olive-SQ. The Olive-SQ could also be utilized as even more thermo-oxidative stable base oil, if the high viscosity and pour point are addressed with proper lubricant additives during the lubricant formulation process.

However, further investigation of rheological (i.e., shear and pressure viscosity dependency), material and tribological base oil properties (i.e., corrosion, friction, and wear characteristics), among others, is needed along with considerations of plant-derived base oil’s composition uniformity, due to positive and negative attributes of the present impurities for comprehensive suitability assessment.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: FT-IR difference spectra of altered PAO 4; Figure S2: FT-IR difference spectra of altered Sugar-SQa; Figure S3: FT-IR difference spectra of altered Olive-SQ; Figure S4: Boiling range distribution of fresh and altered oils by simulated distillation; Figure S5: GC-MS full chromatograms of fresh and altered base oils with absolute intensities; Figure S6: GC-MS chromatograms for the comparison of the buildup of degradation products of fresh and altered PAO 4. The x-axis is cut, where no interesting products appear; Figure S7: GC-MS chromatograms for the comparison of the buildup of degradation products of fresh and altered Sugar-SQa. The x-axis is cut, where no interesting products appear; Figure S8: GC-MS chromatograms for the comparison of the buildup of degradation products of fresh and altered Olive-SQ. The x-axis is cut, where no interesting products appear; Figure S9: Amides and monoglycerides in the fresh and final altered Olive-SQ samples via HR-MS. Intensities are scaled according to the highest intensity in each individual spectrum.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P., A.A., L.P., I.M., F.M., N.D.; data curation, J.P., L.P., I.M.; investigation, J.P., A.A., L.P.; visualization, J.P., A.A.; writing – original draft preparation, J.P., A.A.; writing – review & editing, J.P., A.A., L.P., I.M., F.M., N.D.; funding acquisition, F.M., N.D.; project administration, F.M., L.P., N.D.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This work was carried out as part of the COMET Centre InTribology (FFG no. 906860), a project of the “Excellence Centre for Tribology” (AC2T research GmbH). InTribology is funded within the COMET – Competence Centres for Excellent Technologies Programme by the federal ministries BMK and BMAW as well as the federal states of Niederösterreich and Vorarlberg based on financial support from the project partners involved. COMET is managed by The Austrian Research Promotion Agency (FFG).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our colleagues from AC2T research GmbH for their consultations and supporting analyses carried out within the scope of the presented work.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Jessica Pichler, Adam Agocs, Lucia Pisarova, Marcella Frauscher, and Nicole Dörr were employed by the company AC2T research GmbH.

References

- M. A. Ijaz Malik, M. A. Kalam, M. A. Mujtaba and F. Almomani, "A review of recent advances in the synthesis of environmentally friendly, sustainable, and nontoxic bio-lubricants: Recommendations for the future implementations", Environmental Technology & Innovation, vol. 32, p. 103366, November 2023. [CrossRef]

- INEOS Oligomers, "Durasyn Polyalphaolefin", [Online]. Available: https://www.ineos.com/businesses/ineos-oligomers/products/durasyn-polyalphaolefin-pao/. [Accessed 21 11 2024].

- J. V. Rensselar, "The bright future for PAOs", February 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.stle.org/files/TLTArchives/2021/02_February/Cover_Story.aspx. [Accessed 22 11 2024].

- C. o. t. E. U. European Parliament, "Commission Decision (EU) 2018/1702 of 8 November 2018 establishing the EU Ecolabel criteria for lubricants (notified under document C(2018) 7125)", Official Journal of the European Union, vol. OJ L 285, p. 82–96, 2018.

- INEOS Oligomers, "Durasyn® Polyalphaolefins: Summary of Environmental Data", 2009. [Online]. Available: https://www.ineos.com/globalassets/ineos-group/businesses/ineos-oligomers/she/durasyn-environmental-summary-202009.pdf. [Accessed 21 11 2024].

- E. Beran, "Experience with evaluating biodegradability of lubricating base oils", Tribology International, vol. 41, p. 1212–1218, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Infineum Insight, "Moving to even lower viscosities", June 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.infineuminsight.com/en-gb/articles/moving-to-even-lower-viscosities/. [Accessed 21 11 2024].

- Eurol BV, "Thin, thinner, thinnest: The trend towards low-viscosity engine oils", March 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.eurol.com/en/updates/knowledge-articles/thin-thinner-thinnest-the-trend-towards-low-viscosity-engine-oils. [Accessed 22 11 2024].

- WECTOL Oil & Carcare Products, "Motoröl nach Viskosität", [Online]. Available: https://www.addinol-shop.de/pkw-oel/viskositat.html. [Accessed 21 11 2024].

- Emery Oleochemicals, "Base Stocks and Components for Electric Vehicle - Oils and Thermal Fluids", 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.emeryoleo.com/sites/default/files/2024-04/Emery-Oleochemicals-Base-Stocks-Components-Electric-Vehicles.pdf. [Accessed 22 11 2024].

- R. Veluri, "Electric Vehicle Lubricants", February 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.tribonet.org/industry-news/electric-vehicle-lubricants/. [Accessed 22 11 2024].

- INEOS Oligomers, "Durasyn® 164 - Technical Data Sheet", [Online]. Available: https://www.ineos.com/show-document/?grade=Durasyn+164&bu=INEOS+Oligomers&documentType=Technical+Data+Sheet&docLanguage=EN&version=d0d59cc79b3ea2924fb74faf79f6d5dd. [Accessed 22 11 2024].

- Ç. Yarkent and S. S. Oncel, "Recent Progress in Microalgal Squalene Production and Its Cosmetic Application", Biotechnology and Bioprocess Engineering, vol. 27, p. 295–305, June 2022. [CrossRef]

- OENORM EN 16807: Liquid petroleum products - Bio-lubricants - Criteria and requirements of bio-lubricants and bio-based lubricants. Austrian Standards International. Wien, Austria, 2016.

- Vidal-Abarca Garrido Candela, K. Kaps Renata, Oyeshola, W. Oliver, R. M. Rosa, H. Carme, F. Natalia, E. Marta, J. Gemma, J. Jaume and B. Elisabet, "Revision of the European Ecolabel Criteria forLubricants", 2018. [Online]. Available: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/ecolabel/documents/Final Report EU Ecolabel Lubricants.pdf. [Accessed 04 12 2024].

- CIRCABC, "Lubricant Substance Classification list (LuSC-list) 01/10/2024", November 2024. [Online]. Available: https://circabc.europa.eu/ui/group/0e3024d9-38be-415b-b141-c05d5d31dd92/library/997552dd-7098-4ffb-87db-3590fc2ff32e/details. [Accessed 04 12 2024].

- European Commission, "EU Ecolabel - Lubricants", [Online]. Available: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/circular-economy/eu-ecolabel/product-groups-and-criteria/lubricants_en. [Accessed 22 11 2024].

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), "VESSEL GENERAL PERMIT FOR DISCHARGES INCIDENTAL TO THE NORMALOPERATION OF VESSELS (VGP)", 2013. [Online]. Available: https://www3.epa.gov/npdes/pubs/vgp_permit2013.pdf. [Accessed 04 12 2024].

- Valvoline Global Operations, "What Are Environmentally-Friendly Lubricants?", [Online]. Available: https://www.valvolineglobal.com/en-eur/what-are-environmentally-friendly-lubricants/. [Accessed 22 11 2024].

- D. J. Tenenbaum, "Food vs. Fuel: Diversion of Crops Could Cause More Hunger", Environmental Health Perspectives, vol. 116, June 2008. [CrossRef]

- European Parliament, Council of the European Union, "Directive (EU) 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 on the promotion of the use of energy from renewable sources (recast) (Text with EEA relevance.)", Official Journal of the European Union, vol. OJ L 328, p. 82–209, 2018.

- European Court Of Auditors, "The EU’s support for sustainable biofuels in transport - An unclear route ahead", 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.eca.europa.eu/ECAPublications/SR-2023-29/SR-2023-29_EN.pdf. [Accessed 21 11 2024].

- M. Carus, L. Dammer, Á. Puente, A. Raschka and O. Arend, "Bio-based drop-in, smart drop-in and dedicated chemicals", 2017. [Online]. Available: https://bioplasticsnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/RoadToBio_Drop-in_paper.pdf. [Accessed 21 11 2024].

- "Squalane: benefits for skin and usage in cosmetic", SOPHIM, [Online]. Available: https://www.sophim.com/en/squalane/. [Accessed 11 25 2024].

- D. McPhee, A. Pin, L. Kizer and L. Perelman, "Deriving Renewable - Squalane from Sugarcane", Cosmetics & Toiletries magazine, vol. 129, no. 6, 2014.

- P. Havaej, J. Degroote and D. Fauconnier, "Sensitivity of TEHL Simulations to the Use of Different Models for the Constitutive Behaviour of Lubricants", Lubricants, vol. 11, p. 151, March 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. H. C. Lee, S. K. Poornachary, X. Y. Tee, L. Guo, C. K. Liu, L. Zhang, T. Sun, Q. Chen, J. Zheng and P. S. Chow, "Effect of Base Oil Polarity on the Functional Mechanism of a Viscosity Modifier: Unraveling the Conundrum of Coil Expansion Model", Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, vol. 62, p. 20567–20578, November 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Schmitt, F. Fleckenstein, H. Hasse and S. Stephan, "Comparison of Force Fields for the Prediction of Thermophysical Properties of Long Linear and Branched Alkanes", The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, vol. 127, p. 1789–1802, February 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. C. Liu, B. B. Zhang, N. Bader, C. H. Venner and G. Poll, "Scale and contact geometry effects on friction in thermal EHL: twin-disc versus ball-on-disc", Tribology International, vol. 154, p. 106694, February 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. C. Liu, B. B. Zhang, N. Bader, C. H. Venner and G. Poll, "Simplified traction prediction for highly loaded rolling/sliding EHL contacts", Tribology International, vol. 148, p. 106335, August 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Tošić, R. Larsson, J. Jovanović, T. Lohner, M. Björling and K. Stahl, "A Computational Fluid Dynamics Study on Shearing Mechanisms in Thermal Elastohydrodynamic Line Contacts", Lubricants, vol. 7, p. 69, August 2019. [CrossRef]

- W. Li and V. Jadhao, "Comparing Phenomenological Models of Shear Thinning of Alkanes at Low and High Newtonian Viscosities", Tribology Letters, vol. 72, September 2024. [CrossRef]

- ASTM D943-20: Standard Test Method for Oxidation Characteristics of Inhibited Mineral Oils, ASTM International. [CrossRef]

- ASTM D2272-22: Standard Test Method for Oxidation Stability of Steam Turbine Oils by Rotating Pressure Vessel, West Conshohocken, PA, USA. [CrossRef]

- M. Frauscher, C. Besser, G. Allmaier and N. Dörr, "Oxidation Products of Ester-Based Oils with and without Antioxidants Identified by Stable Isotope Labelling and Mass Spectrometry", Applied Sciences, vol. 7, p. 396, April 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Diaby, M. Sablier, A. Le Negrate and M. El Fassi, "Kinetic Study of the Thermo-Oxidative Degradation of Squalane (C30H62) Modeling the Base Oil of Engine Lubricants", Journal of Engineering for Gas Turbines and Power, vol. 132, November 2009. [CrossRef]

- T. I. J. Dugmore and M. S. Stark, "Effect of biodiesel on the autoxidation of lubricant base fluids", Fuel, vol. 124, p. 91–96, May 2014. [CrossRef]

- European Chemicals Agency (ECHA), "2,6,10,15,19,23-hexamethyltetracosane", 2023. [Online]. Available: https://echa.europa.eu/de/registration-dossier/-/registered-dossier/14412/5/3/2. [Accessed 04 12 2024].

- Chevron Phillips Chemical Company LP, "Product Stewardship Summary - PAO 4-10 cSt", 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.cpchem.com/sites/default/files/2020-09/PAO 4-10 PSS 2020 update Rev 2.pdf. [Accessed 04 12 2024].

- M. Frauscher, A. Agocs, C. Besser, A. Rögner, G. Allmaier and N. Dörr, "Time-Resolved Quantification of Phenolic Antioxidants and Oxidation Products in a Model Fuel by GC-EI-MS/MS", Energy & Fuels, vol. 34, p. 2674–2682, January 2020. [CrossRef]

- DIN EN 16091: Liquid petroleum products - Middle distillates and fatty acid methyl ester (FAME) fuels and blends - Determination of oxidation stability by rapid small scale oxidation test (RSSOT), Berlin, Germany. [CrossRef]

- DIN 51453:2024-08: Testing of lubricants - Determination of oxidation and nitration of used motor oils - Infrared spectrometric method, Berlin, Germany, 2024.

- DIN 51558-2: Testing of mineral oils - Determination of neutralization number - Part 2: Color-indicator titration, insulating oils, Berlin, Germany, 2017.

- DIN 51777: Petroleum products - Determination of water content using titration according to Karl Fischer, Berlin, Germany, 2020. [CrossRef]

- ASTM D7042: Standard Test Method for Dynamic Viscosity and Density of Liquids by Stabinger Viscometer (and the Calculation of Kinematic Viscosity, West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021. [CrossRef]

- ASTM D2270: Standard Practice for Calculating Viscosity Index from Kinematic Viscosity at 40 °C and 100 °C, West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024. [CrossRef]

- DIN EN ISO 3016: Petroleum and related products from natural or synthetic sources - Determination of pour point, Berlin, Germany, 2019. [CrossRef]

- ASTM D6352: Standard Test Method for Boiling Range Distribution of Petroleum Distillates in Boiling Range from 174 °C to 700 °C by Gas Chromatography, ASTM International, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Agocs, A. L. Nagy, A. Ristic, Z. M. Tabakov, P. Raffai, C. Besser and M. Frauscher, "Oil Degradation Patterns in Diesel and Petrol Engines Observed in the Field—An Approach Applying Mass Spectrometry", Lubricants, vol. 11, p. 404, September 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Frauscher, "Capillary GC-EI-MS and low energy tandem MS of base oils and additives in lubricants and fuels", TU Wien, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Stark, J. J. Wilkinson, J. R. L. Smith, A. Alfadhl and B. A. Pochopien, "Autoxidation of Branched Alkanes in the Liquid Phase", Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, vol. 50, p. 817–823, January 2011. [CrossRef]

- Agocs, A. L. Nagy, Z. Tabakov, J. Perger, J. Rohde-Brandenburger, M. Schandl, C. Besser and N. Dörr, "Comprehensive assessment of oil degradation patterns in petrol and diesel engines observed in a field test with passenger cars – Conventional oil analysis and fuel dilution", Tribology International, vol. 161, p. 107079, September 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Wu, S. C. Ho and T. R. Forbus, "Practical Advances in Petroleum Processing", in Practical Advances in Petroleum Processing, C. S. Hsu and P. R. Robinson, Eds., Springer New York, 2006, p. 553–577. [CrossRef]

- S. Son and B. A. Lewis, "Free Radical Scavenging and Antioxidative Activity of Caffeic Acid Amide and Ester Analogues: Structure−Activity Relationship", Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, vol. 50, p. 468–472, December 2001. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Main processing steps of C30H62 base oils sourced from different raw materials. Methyl groups are depicted by blue circles, and tertiary carbon atoms are marked with green circles.

Figure 1.

Main processing steps of C30H62 base oils sourced from different raw materials. Methyl groups are depicted by blue circles, and tertiary carbon atoms are marked with green circles.

Figure 2.

(a) FT-IR absorbance spectra of fresh base oils; (b) FT-IR difference spectra of final altered base oils.

Figure 2.

(a) FT-IR absorbance spectra of fresh base oils; (b) FT-IR difference spectra of final altered base oils.

Figure 3.

(a) Pressure curves of the base oils, (b) Oxidation during the artificial alterations (Sugar-SQa and PAO 4 only), (c) Unsaturated hydrocarbons during the artificial alteration (Sugar-SQa and PAO 4 only) (d) Photographic documentation at the end of the artificial alterations.

Figure 3.

(a) Pressure curves of the base oils, (b) Oxidation during the artificial alterations (Sugar-SQa and PAO 4 only), (c) Unsaturated hydrocarbons during the artificial alteration (Sugar-SQa and PAO 4 only) (d) Photographic documentation at the end of the artificial alterations.

Figure 4.

Characterization of the final oil samples: (a) OIT and TOT, (b) Total pressure loss, (c) Oxidation, (d) Neutralization number, (e) Unsaturation (unsaturated hydrocarbons), (f) Water content.

Figure 4.

Characterization of the final oil samples: (a) OIT and TOT, (b) Total pressure loss, (c) Oxidation, (d) Neutralization number, (e) Unsaturation (unsaturated hydrocarbons), (f) Water content.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the kinematic viscosity and density of the fresh and final altered oil samples. (a) PAO 4, low temperature, (b) PAO 4, high temperature, (c) Sugar-SQa, low temperature, (d) Sugar-SQa, high temperature, (e) Olive-SQ, low temperature, (f) Olive-SQ, high temperature.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the kinematic viscosity and density of the fresh and final altered oil samples. (a) PAO 4, low temperature, (b) PAO 4, high temperature, (c) Sugar-SQa, low temperature, (d) Sugar-SQa, high temperature, (e) Olive-SQ, low temperature, (f) Olive-SQ, high temperature.

Figure 7.

GC-MS chromatogram zoom of components found in fresh and altered oils (final samples), displayed in relative intensities. Peaks changing throughout artificial alteration of base oil samples are highlighted with their retention times. The compounds found within the ranges of * and ** are described in

Table 5.

Figure 7.

GC-MS chromatogram zoom of components found in fresh and altered oils (final samples), displayed in relative intensities. Peaks changing throughout artificial alteration of base oil samples are highlighted with their retention times. The compounds found within the ranges of * and ** are described in

Table 5.

Figure 8.

Identified amides and monoglycerides (MGs) in fresh base oil samples at comparable intensities in ESI negative ion mode.

Figure 8.

Identified amides and monoglycerides (MGs) in fresh base oil samples at comparable intensities in ESI negative ion mode.

Figure 9.

Dehydrogenation products identified in the final altered oil samples at comparable intensities in ESI positive ion mode.

Figure 9.

Dehydrogenation products identified in the final altered oil samples at comparable intensities in ESI positive ion mode.

Table 1.

Overview of the selected base oils, including their feedstock, processing method, biodegradation, and renewability characteristics. According to OECD 301B [38, 39].

Table 1.

Overview of the selected base oils, including their feedstock, processing method, biodegradation, and renewability characteristics. According to OECD 301B [38, 39].

| Sample ID |

Origin |

Processing method |

Biodegrad-ability* |

Renew-ability |

| PAO 4 |

Crude oil, ethylene, 1-decene |

Fully synthesized, distilled, and hydrogenated hydrocarbon base fluid produced from linear alpha olefin feedstocks [12] |

Not ready |

0 % |

| Sugar-SQa |

Sugarcane |

Production of β-farnesene (precursor of squalene) through fermentation of sugar using the yeast S. cerevisiae, removal of yeast, hydrogenation, and purification to high-purity squalane [25] |

Ready |

100 % |

| Sugar-SQb |

Sugarcane |

n.a. |

Ready |

100 % |

| Olive-SQ |

Olive oil waste |

Extracted as squalene from an unsaponifiable fraction of olive oil (acid oil) and hydrogenated to squalane [24] |

Ready |

100 % |

Table 2.

RPVOT test parameters

Table 2.

RPVOT test parameters

| Parameter |

Value |

| Temperature |

120 °C |

| Reaction gas |

Oxygen 5.0 |

| Overpressure at start |

2 bar |

| Sample amount |

50 g |

| Stirring |

100 rpm |

Table 3.

Comparison of fresh base oils by conventional lubricant parameters.

Table 3.

Comparison of fresh base oils by conventional lubricant parameters.

| Oil sample |

PP (°C) |

NN

(mg KOH/g) |

Water (ppm) |

Kinematic viscosity

(mm²/s) |

VI

(-) |

| -20 °C |

0 °C |

40 °C |

100 °C |

| PAO 4 |

-75 |

<0.05 |

<10 |

407 |

106 |

17.5 |

4.0 |

128 |

| Olive-SQ |

-3 |

<0.05 |

<10 |

1798 |

204 |

22.2 |

4.5 |

116 |

| Sugar-SQa |

-72 |

<0.05 |

<20 |

687 |

142 |

19.0 |

4.1 |

117 |

| Sugar-SQb |

-72 |

<0.05 |

<20 |

689 |

142 |

19.1 |

4.1 |

115 |

Table 4.

Boiling behavior of fresh and altered base oils determined by simulated distillation.

Table 4.

Boiling behavior of fresh and altered base oils determined by simulated distillation.

| Oil sample |

Starting point (°C) |

End point (°C) |

Low MW fraction (wt %) |

Main fraction (wt%) |

High MW fraction (wt%) |

| PAO 4 fresh |

330 |

594 |

19 |

35 |

46 |

| PAO 4 altered |

333 |

576 |

20 |

30 |

50 |

| Sugar-SQa fresh |

344 |

538 |

19 |

54 |

27 |

| Sugar-SQa altered |

335 |

510 |

18 |

63 |

19 |

| Olive-SQ fresh |

306 |

556 |

25 |

43 |

32 |

| Olive-SQ altered |

317 |

508 |

19 |

59 |

22 |

Table 5.

GC-MS compound identification in fresh and altered base oils according to NIST library evaluation.

Table 5.

GC-MS compound identification in fresh and altered base oils according to NIST library evaluation.

| Type |

Retention time in min |

Substance |

|

| PAO 4 |

5.76 |

Pentanoic acid, TMS |

|

| 7.01 |

Derivatization agent |

|

| 7.14 |

Hexanoic acid, TMS |

|

| 8.54 |

Heptanoic acid, TMS |

|

| 9.89 |

Octanoic acid, TMS |

|

| 11.2 |

Nonanoic acid, TMS |

|

| 12.4 |

Decanoic acid, TMS |

|

| 13.6 |

Undecanoic acid, TMS |

|

| * |

Alkanes |

|

| Squalanes |

6.57 |

4-Methylvaleric acid (C6), TMS |

|

| 6.94 |

Derivatization agent |

|

| 10.4 |

Alcoholic compound |

|

| 11.1 |

3,7-Dimethyldecanoic acid (C10), TMS |

|

| 11.7 |

2-Undecanone, 6,10-dimethyl- (C13) |

|

| 12.4 |

7-Methyldecanoic acid (C11), TMS |

|

| 13.5 |

Alkane |

|

| 14.1 |

Alkane |

|

| 14.8 |

2-Methylundecanoic acid (C12), TMS |

|

| 15.9 |

Alcoholic compound |

|

| 16.0 |

n-Pentadecanoic acid (C15), TMS |

|

| ** |

Alcohols/esters/hydrocarbons |

|

| 17.1 |

Hexadecanoic acid (C16), TMS |

|

| 17.7 |

Ketonic compound (C18) |

|

| 18.1 |

Heptadecanoic acid (C17), TMS |

|

| 19.2 |

Alkane |

|

| 19.9 |

Alkane |

|

| 20.3 |

Octadecenoic acid (C18), TMS |

|

| 20.4 |

Alkane |

|

| 20.5 |

Octadecanoic acid (C18), TMS |

|

| 20.9 |

Alkane |

|

| 21.3 |

Alkene |

|

| 21.6 |

Ketonic compound |

|

| 21.8 |

Alkane |

|

| 23.1-24.1 |

Squalane |

|

| 25.0 |

Alkene |

|

| 26.0 |

unidentified |

|

| 26.4 |

unidentified |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).