Submitted:

09 December 2024

Posted:

10 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites

2.2. AFLP Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hamrick, J.L.; Godt, M.J.W. Effects of life history traits on genetic diversity in plant species. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 1996, 351, 1291–1298, . [CrossRef]

- Hamrick, J.L.; Linhart; V.B.; Mitfon, J. Relationships between life history characteristics and electrophoretically detectable genetic variation in plants. Annual Review of Ecology; Evolution; and Systematics, 1979, 10, 173–200.

- Loveless, M.D.; Hamrick, J.L. Ecological Determinants of Genetic Structure in Plant Populations. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1984, 15, 65–95, . [CrossRef]

- Nybom, H.; Bartish, I.V. Effects of life history traits and sampling strategies on genetic diversity estimates obtained with RAPD markers in plants. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2000, 3, 93–114, . [CrossRef]

- Petit, R.J.; Duminil, J.; Fineschi, S.; Hampe, A.; Salvini, D.; Vendramin, G.G. INVITED REVIEW: Comparative organization of chloroplast, mitochondrial and nuclear diversity in plant populations. Mol. Ecol. 2004, 14, 689–701, . [CrossRef]

- Vekemans, X.; Hardy, O.J. New insights from fine-scale spatial genetic structure analyses in plant populations. Mol. Ecol. 2004, 13, 921–935, . [CrossRef]

- Volis, S.; Zaretsky, M.; Shulgina, I. Fine-scale spatial genetic structure in a predominantly selfing plant: role of seed and pollen dispersal. Heredity 2009, 105, 384–393, . [CrossRef]

- Binks, R.M.; Millar, M.A.; Byrne, M. Not all rare species are the same: contrasting patterns of genetic diversity and population structure in two narrow-range endemic sedges. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2015, 114, 873–886, . [CrossRef]

- Mosca, E.; Di Pierro, E.A.; Budde, K.B.; Neale, D.B.; González-Martínez, S.C. Environmental effects on fine-scale spatial genetic structure in four Alpine keystone forest tree species. Mol. Ecol. 2017, 27, 647–658, . [CrossRef]

- Wahlund, S. Zusammensetzung von Population und Korrelationserscheinung vom Standpunkt der Vererbungslehre aus betrachtet. Hereditas, 1928, 11, 65–106.

- Duminil, J.; Hardy, O.J.; Petit, R.J. Plant traits correlated with generation time directly affect inbreeding depression and mating system and indirectly genetic structure. BMC Evol. Biol. 2009, 9, 177–177, . [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, R.L.; Ackerman, J.D.; Zimmerman, J.K.; Calvo, R.N. Variation in sexual reproduction in orchids and its evolutionary consequences: a spasmodic journey to diversification. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2004, 84, 1–54, . [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, S.; Schiestl, F.P.; Müller, A.; De Castro, O.; Nardella, A.M.; Widmer, A. Evidence for pollinator sharing in Mediterranean nectar-mimic orchids: absence of premating barriers?. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2005, 272, 1271–1278, . [CrossRef]

- Neiland, M.R.M.; Wilcock, C.C. Fruit set, nectar reward, and rarity in the Orchidaceae. Am. J. Bot. 1998, 85, 1657–1671, . [CrossRef]

- Jersáková, J.; Johnson, S.D.; Kindlmann, P. Mechanisms and evolution of deceptive pollination in orchids. Biol. Rev. 2006, 81, 219–235, . [CrossRef]

- Juillet, N.; Dunand-Martin, S.; Gigord, L.D.B. Evidence for Inbreeding Depression in the Food-Deceptive Colour-Dimorphic Orchid Dactylorhiza sambucina (L.) Soò. Plant Biology, 2006, 9(1), 147-51.

- Kropf, M.; Renner, S.S. Pollinator-mediated selfing in two deceptive orchids and a review of pollinium tracking studies addressing geitonogamy. Oecologia 2007, 155, 497–508, . [CrossRef]

- Jacquemyn, H.; Brys, R. Lack of strong selection pressures maintains wide variation in floral traits n a food-deceptive orchid. Ann. Bot. 2020, 126, 445–453, . [CrossRef]

- Machon, N.; Bardin, P.; Mazer, S.J.; Moret, J.; Godelle, B.; Austerlitz, F. Relationship between genetic structure and seed and pollen dispersal in the endangered orchidSpiranthes spiralis. New Phytol. 2003, 157, 677–687, . [CrossRef]

- Jersáková, J.; Malinová, T. Spatial aspects of seed dispersal and seedling recruitment in orchids. New Phytol. 2007, 176, 237–241, . [CrossRef]

- Brzosko, E.; Ostrowiecka, B.; Kotowicz, J.; Bolesta, M.; Gromotowicz, A.; Gromotowicz, M.; Orzechowska, A.; Orzołek, J.; Wojdalska, M. Seed dispersal in six species of terrestrial orchids in Biebrza National Park (NE Poland). Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2017, 86, . [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.Y.; Nason, J.D.; Chung, M.G. Spatial genetic structure in populations of the terrestrial orchid Cephalanthera longibracteata (Orchidaceae). American Journal of Botany, 2004, 91, 52–57.

- Nason, J.D.; Chung, M.G. Spatial genetic structure in populations of the terrestrial orchid Orchis cyclochila (Orchidaceae). Plant Syst. Evol. 2005, 254, 209–219, . [CrossRef]

- Trapnell, D.W.; Hamrick, J.L. Mating patterns and geneflow in the Neotropical epiphytic orchid; Laelia rubescens. Molecular Ecology, 2005, 14; 75–84.

- Trapnell, D.W.; Hamrick, J.L.; Nason, J.D. Three-dimensional fine-scale genetic structure of the Neotropicalepiphytic orchid; Laelia rubescens. Molecular Ecology, 2004,13 1111–1118.

- Peakall, R.; Beattie, A.J. Ecological and genetic consequences of pollination by sexual deception in the orchid Calladenia tentaculata. Evolution, 1996, 50, 2207–2220.

- Jacquemyn, H.; Brys, R.; Vandepitte, K.; Honnay, O.; Roldán-Ruiz, I. Fine-scale genetic structure of life history stages in the food-deceptive orchid Orchis purpurea. Molecular Ecology, 2006, 15, 2801–2808.

- Jacquemyn, H.; Wiegand, T.; Vandepitte, K.; Brys, R.; Roldán-Ruiz, I.; Honnay, O. Multigenerational analysis of spatial structure in the terrestrial, food-deceptive orchid Orchis mascula. J. Ecol. 2009, 97, 206–216, . [CrossRef]

- Helsen, K.; Meekers, T.; Vranckx, G.; Roldán-Ruiz, I.; Vandepitte, K.; Honnay, O. A direct assessment of realized seed and pollen flow within and between two isolated populations of the food-deceptive orchidOrchis mascula. Plant Biol. 2015, 18, 139–146, . [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.Y.; Nason, J.D.; Chung, M.G. Significant fine-demographic and scale genetic structure in expanding and senescing populations of the terrestrial orchid Cymbidium goeringii (Orchidaceae). American Journal of Botany, 2011, 98, 2027–2039.

- Sletvold, N.; Grindeland, J.M.; Zu, P.; Ågren, J. Fine-scale genetic structure in the orchid Gymnadenia conopsea is not associated with local density of flowering plants. American Journal of Botany, 2024, 111 (2), e16273.

- Pandey, M.; Sharma, J. Efficiency of microsatellite isolation from orchids via next generation sequencing. Open J. Genet. 2012, 02, 167–172, . [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.Y.; Chung, M.G. Extremely low levels of genetic diversity in the terrestrial orchid Epipactis thunbergii (Orchidaceae) in South Korea, implications for conservation Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 2007, 155, 161–169.

- Diez, J.M. Hierarchical patterns of symbiotic orchid germination linked to adult proximity and environmental gradients. J. Ecol. 2006, 95, 159–170, . [CrossRef]

- Jacquemyn, H.; Wiegand, T.; Vandepitte, K.; Brys, R.; Roldán-Ruiz, I.; Honnay, O. Spatial variation in below-ground seed germination and divergent mycorrhizal associations correlate with spatial segregation of three co-occurring orchid species. Journal of Ecology, 2012, 100 (6), 1328–1337.

- Claessens, J.; Kleynen, J. The flower of the European orchid, form and function. 2011. Voerendaal, Jean Claessens and Jacques Kleynen.

- Mattila, E.; Kuitunen, T.M. Nutrient versus pollination limitation in Platanthera bifolia and Dactylorhiza incarnata (Orchidaceae). OIKOS, 2000, 89, 360–366.

- Sletvold, N.; Grindeland, J.M.; Ågren, J. Pollinator-mediated selection on floral display, spur length and flowering phenology in the deceptive orchid Dactylorhiza lapponica. New Phytol. 2010, 188, 385–392, . [CrossRef]

- Trunschke, J.; Sletvold, N.; Ågren, J. Interaction intensity and pollinator-mediated selection. New Phytol. 2017, 214, 1381–1389, . [CrossRef]

- Ostrowiecka, B.; Tałałaj, I.; Brzosko, E.; Jermakowicz, E.; Mirski, P.; Kostro-Ambroziak, A.; Mielczarek, Ł.; Lasoń, A.; Kupryjanowicz, J.; Kotowicz, J.; Wróblewska, A. Pollinators and visitors of the generalized food-deceptive orchid Dactylorhiza majalis in North-Eastern Poland; Biologia, 2019, 74, 1247–1257.

- Wróblewska, A.; Szczepaniak, L.; Bajguz, A.; Jędrzejczyk, I.; Tałałaj, I.; Ostrowiecka, B.; Brzosko, E.; Jermakowicz, E.; Mirski, P. Deceptive strategy in Dactylorhiza orchids: multidirectional evolution of floral chemistry. Ann. Bot. 2019, 123, 1005–1016, . [CrossRef]

- Wróblewska, A.; Ostrowiecka, B.; Brzosko, E.; Jermakowicz, E.; Tałałaj, I.; Mirski, P. The patterns of inbreeding depression in food-deceptive Dactylorhiza orchids. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1244393, . [CrossRef]

- Wróblewska, A.; Ostrowiecka, B.; Kotowicz, J.; Jermakowicz, E.; Tałałaj, I.; Szefer, P. What are the drivers of female success in food-deceptive orchids? Ecology and Evolution, 2024b, 14 (4); 11233.

- Hedrén, M.; Nordström, S. Polymorphic populations of Dactylorhiza incarnata s.l. (Orchidaceae) on the Baltic island of Gotland, Morphology; habitat preference and genetic differentiation. Annals of Botany, 2009, 104 (3), 527–542.

- Vallius, E.; Salonen, V.; Kull, T. Factors of divergence in co-occurring varieties of Dactylorhiza incarnata (Orchidaceae). Plant Syst. Evol. 2004, 248, 177–189, . [CrossRef]

- Kindlmann, P.; Jersáková, J. Effect of floral display on reproductive success in terrestrial orchids. Folia Geobot. 2006, 41, 47–60, . [CrossRef]

- Tałałaj, I.; Kotowicz, J.; Brzosko, E.; Ostrowiecka, B.; Aleksandrowicz, O.; Wróblewska, A. Spontaneous caudicle reconfiguration in Dactylorhiza fuchsii, A new self-pollination mechanism for Orchideae; Plant Systematics and Evolution, 2019, 305, 269–280.

- Siudek, K. The role of pollinarium reconfiguration as the mechanism of selfing in Dactylorhiza majalis and Dactylorhiza incarnata. 2020. PhD dissertation. University of Bialystok; Faculty of Biology; pp. 68.

- Naczk, A.M.; Chybicki, I.J.; Ziętara, M.S. Genetic diversity of Dactylorhiza incarnata (Orchidaceae) in northern Poland. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2016, 85, . [CrossRef]

- Vos, P.; Hogers, R.; Bleeker, M.; Reijans, M.; Van De Lee, T.; Hornes, M.; Friters, A.; Pot, J.; Paleman, J.; Kuiper, M.; et al. AFLP: A new technique for DNA fingerprinting. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995, 21, 4407–4414, doi:10.1093/nar/23.21.4407.

- Zhivotovsky, L.A. Estimating population structure in diploids with multilocus dominant DNA markers. Mol. Ecol. 1999, 8, 907–913, . [CrossRef]

- Vekemans, X.; Beauwens, T.; Lemaire, M.; Roldán-Ruiz, I. Data from amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) markers show indication of size homoplasy and of a relationship between degree of homoplasy and fragment size. Mol. Ecol. 2002, 11, 139–151, . [CrossRef]

- Excoffier, L.; Laval, G.; Schneider, S. Arlequin (version 3.0): An integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. Evol. Bioinform. 2005, 1, 47–50.

- Hardy, O.J. Estimation of pairwise relatedness between individuals and characterization of isolation-by-distance processes using dominant genetic markers. Mol. Ecol. 2003, 12, 1577–1588, . [CrossRef]

- Manly, B. Randomization; Bootstrap and Monte Carlo Methods in Biology. 2007. Third Edition; Chapman and Hall/CRC; London.

- Chybicki, I.J.; Oleksa, A.; Burczyk, J. Increased inbreeding and strong kinship structure in Taxus baccata estimated from both AFLP and SSR data. Heredity 2011, 107, 589–600, . [CrossRef]

- Baskin, J.M.; Baskin, C.C. Inbreeding depression and the cost of inbreeding on seed germination. Seed Sci. Res. 2015, 25, 355–385, . [CrossRef]

- Hedrén M; Nordström S. High levels of genetic diversity in marginal populations of the marsh orchid Dactylorhiza majalis subsp. majalis. Nordic Journal of Botany, 2018, e01747.

- Filippov, E.G.; Andronova, E.V.; Kazlova, V.M. Genetic structure of the populations of Dactylorhiza ochroleuca and D. incarnata (Orchidaceae) in the area of their joint growth in Russia and Belarus. Russ. J. Genet. 2017, 53, 661–671, . [CrossRef]

- Balao, F.; Tannhäuser, M.; Lorenzo, M.T.; Hedrén, M.; Paun, O. Genetic differentiation and admixture between sibling allopolyploids in the Dactylorhiza majalis complex. Heredity 2015, 116, 351–361, . [CrossRef]

- Naczk, A.M.; Ziętara, M.S. Genetic diversity in Dactylorhiza majalis subsp. majalis populations (Orchidaceae) of northern Poland. Nordic Journal of Botany, 2019, e01989.

- Geremew, A.; Stiers, I.; Sierens, T.; Kefalew, A.; Triest, L. Clonal growth strategy; diversity and structure, A spatiotemporal response to sedimentation in tropical Cyperus papirus swamps. PLoS ONE, 2018, 13(1), e0190810.

- Niiniaho, J. The role of geitonogamy in the reproduction success ofa nectarless Dactylorhiza maculata (Orchidaceae). 2011. Dissertation; University of Jyväskylä.

- Eckert, C.G. Contributions of autogamy and geitonogamy to self-fertilization in a mass-flowering; clonal plant. Ecology, 2000, 81(2), 532–542.

- Hayashi, T.; Ayre, B.M.; Bohman, B.; Brown, G.R.; Reiter, N.; Phillips, R.D. Pollination by multiple species of nectar foraging Hymenoptera in Prasophyllum innubum, a critically endangered orchid of the Australian Alps. Aust. J. Bot. 2024, 72, . [CrossRef]

- Husband, B.C.; Schemske, D.W. Evolution of the magnitude and timing of inbreeding depression in plants. Evolution, 1996, 50, 54–70.

- Johnston, M.O.; Schoen, D.J. Correlated Evolution of Self-Fertilization and Inbreeding Depression: An Experimental Study of Nine Populations of Amsinckia (Boraginaceae). Evolution 1996, 50, 1478, . [CrossRef]

- Angeloni, F.; Ouborg, N.J.; Leimu, R. Meta-analysis on the association of population size and life history with inbreeding depression in plants. Biol. Conserv. 2010, 144, 35–43, . [CrossRef]

- Keller, L.F.; Waller, D.M. Inbreeding effects in wild populations. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 2002, 17(5), 230-241.

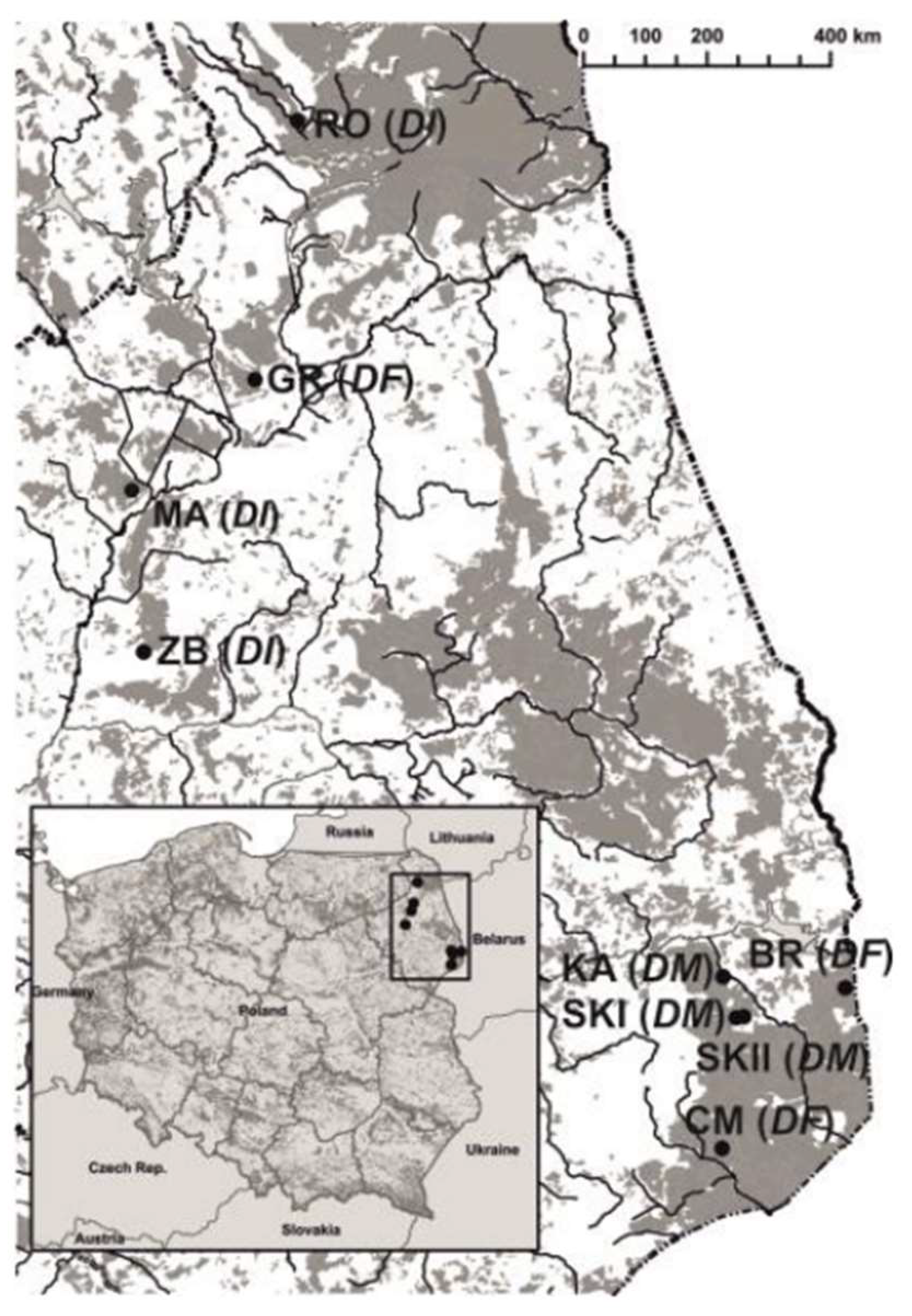

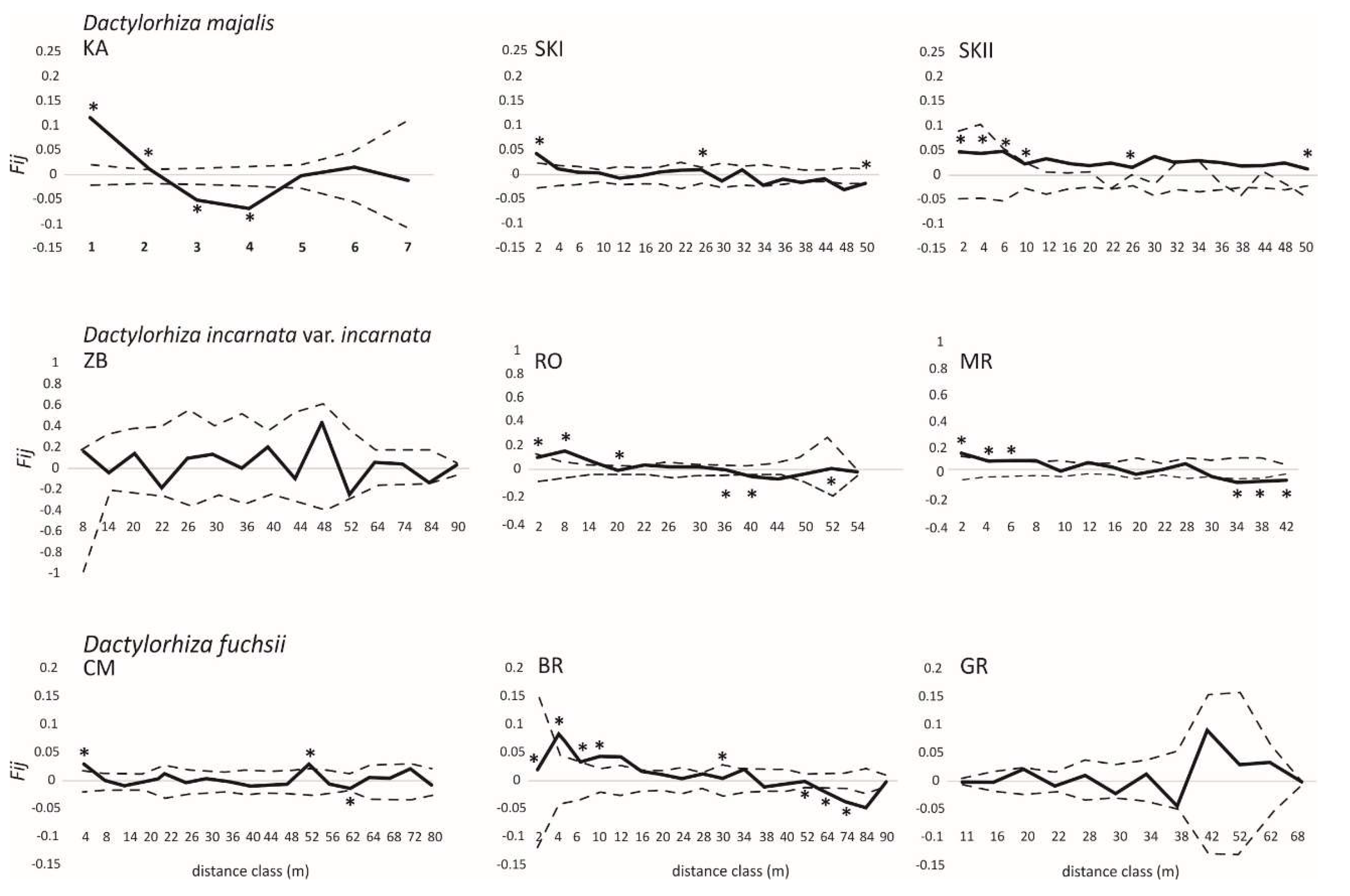

| Taxa | Population | GPS | N | P% | H | FIS (CI) | Fij(1) | b1 | Sp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DM | KA | 52°53’00’’N 23°40’29’’E |

49 | 62.2 | 0.205 | 0.293 (0.000-1.000) | 0.095* | -0.051* | 0.056 |

| SKI | 52°49’50’’N 23°43’10’’E |

59 | 59.6 | 0.205 | 0.312 (0.000-1.000) | 0.038* | -0.009* | 0.001 | |

| SKII | 52°49’50’’N 23°43’10’’E |

54 | 40.4 | 0.140 | 0.192 (0.000-1.000) | 0.071* | -0.021* | 0.022 | |

| DI | ZB | 53°29’02’’N 22°59’28’’E |

48 | 58.6 | 0.217 | 0.179 (0.101-0.284) | 0.008 | -0.002 | 0.0002 |

| RO | 53°54’39’’N 22°56’32’’E |

48 | 58.6 | 0.197 | 0.071 (0.022-0.149) | 0.224* | -0.055* | 0.063 | |

| MR | 53°47’25’’N 22°57’22’’E |

33 | 58.1 | 0.206 | 0.098 (0.032-0.218) | 0.092* | -0.037* | 0.041 | |

| DF | CM | 52°41’03’’N 23°39’07’’E |

58 | 68.4 | 0.234 | 0.113 (0.034-0.244) | 0.078* | -0.021* | 0.019 |

| BR | 52°50’59’’N 23°53’40’’E |

57 | 63.9 | 0.211 | 0.134 (0.068-0.226) | 0.084* | -0.026* | 0.028 | |

| GR | 53°60’68” E 22°84’68”N | 49 | 56.7 | 0.197 | 0.079 (0.024-0.169) | -0.008 | 0.002 | -0.0002 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).