Submitted:

09 December 2024

Posted:

09 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Model

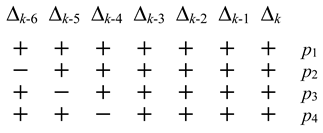

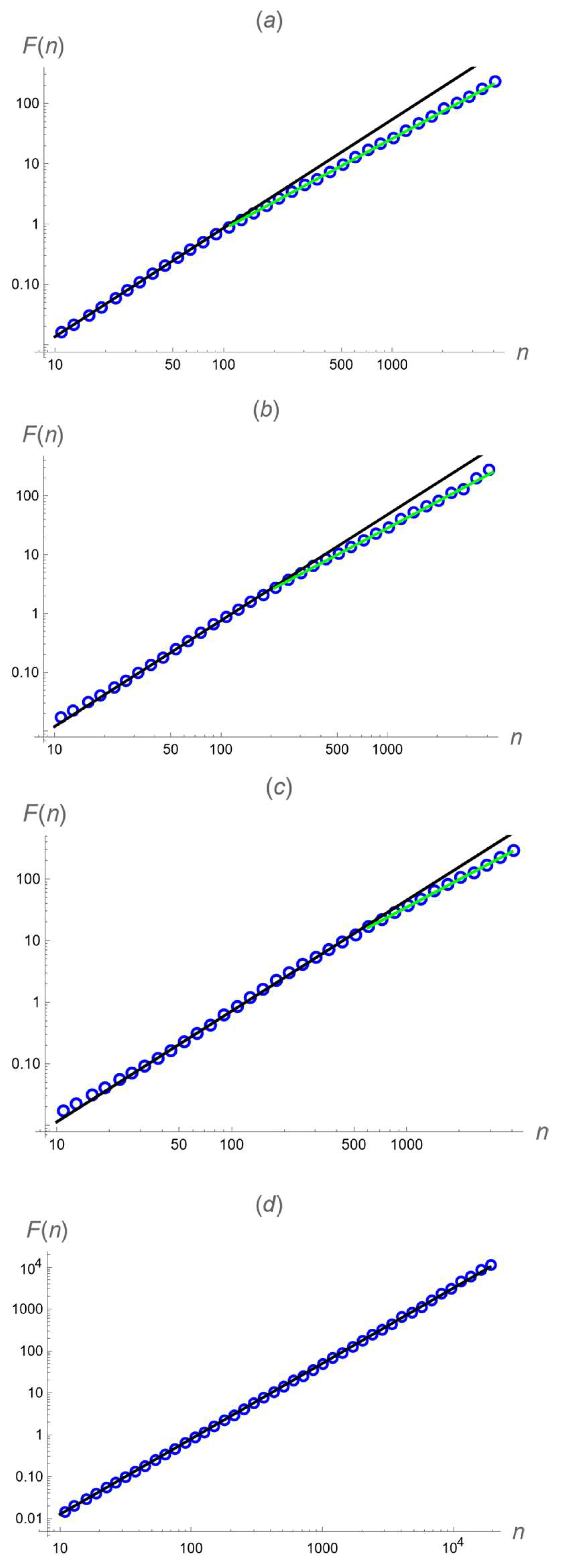

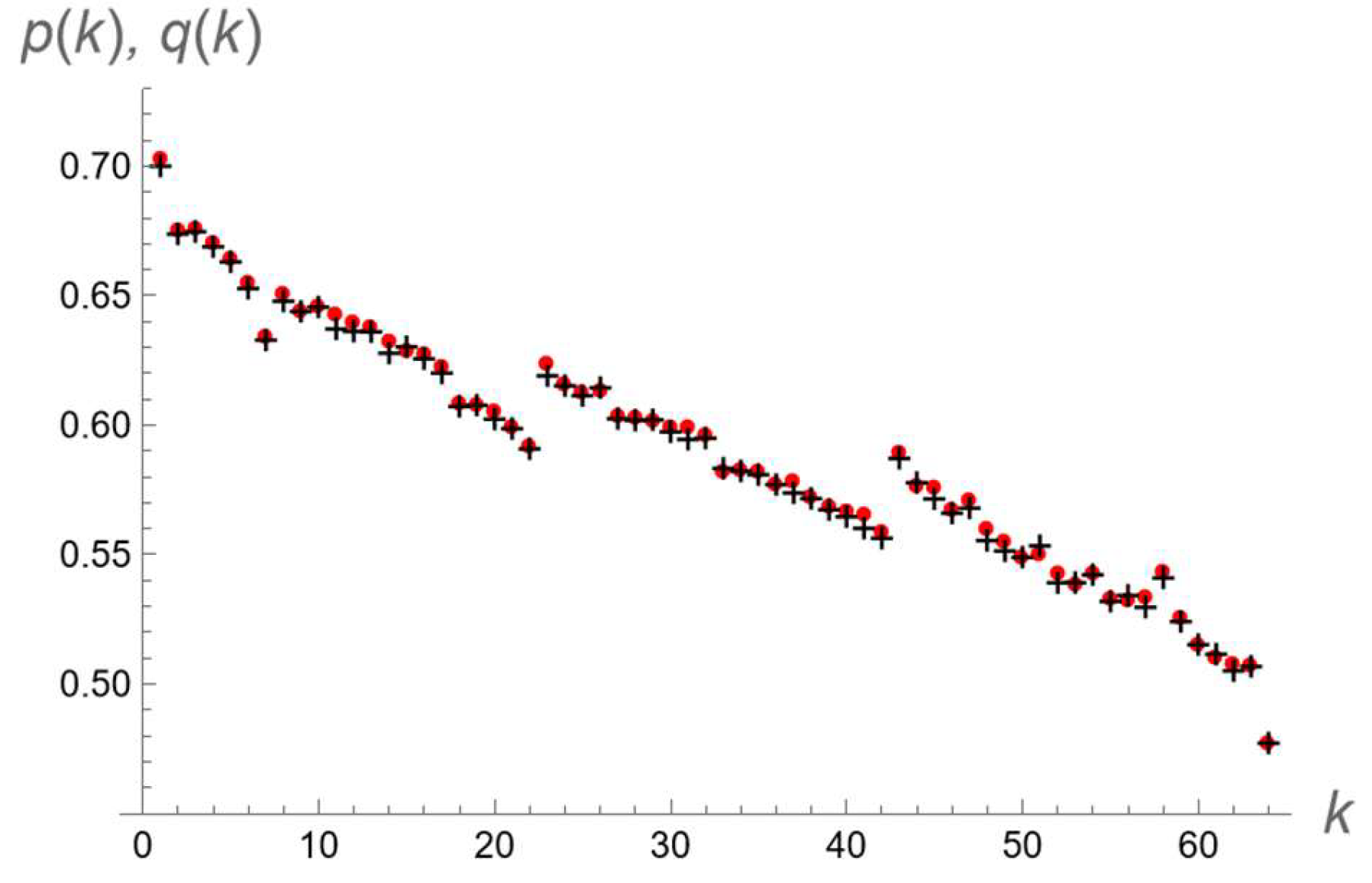

2.1. Persistence

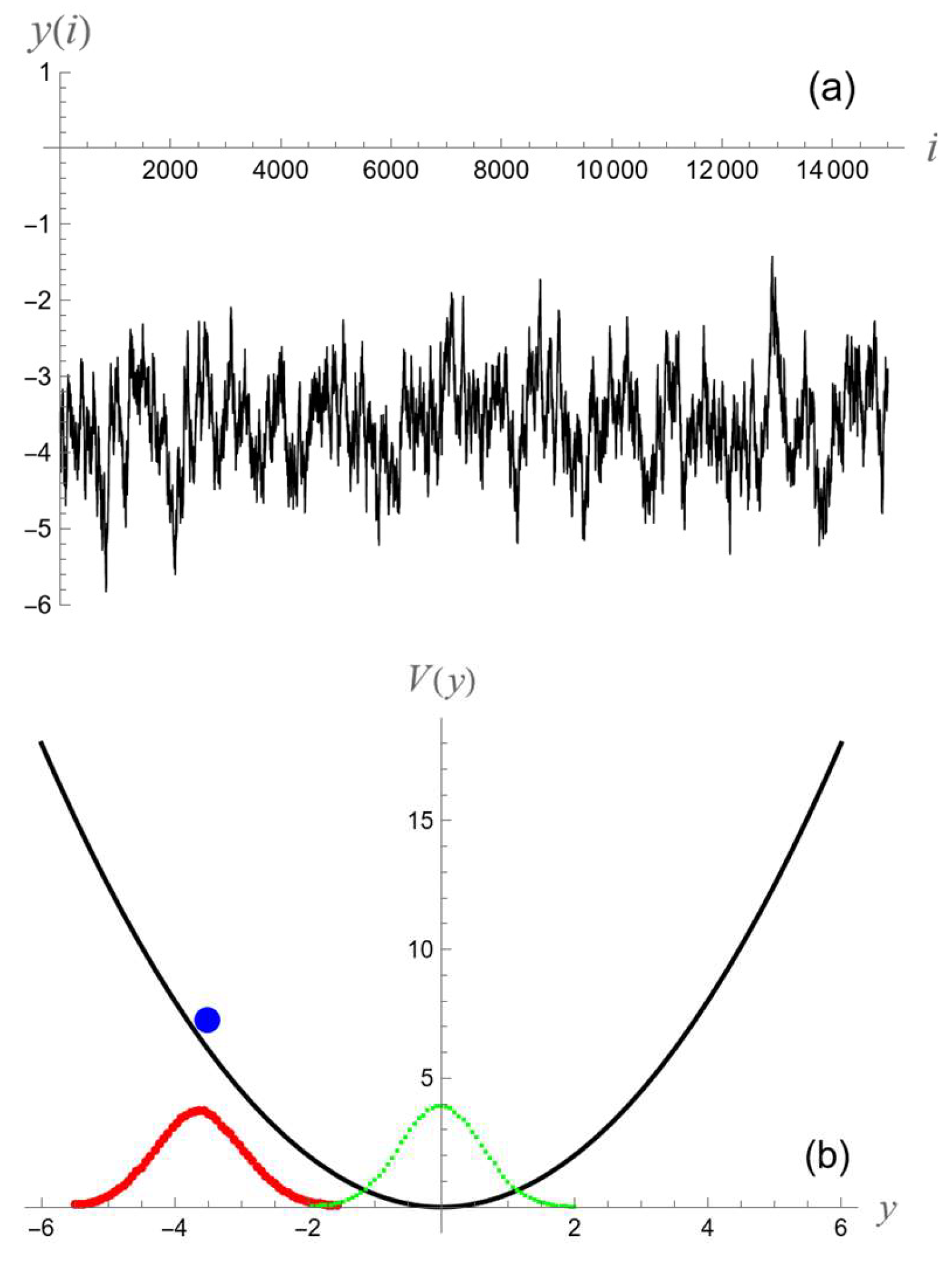

2.2. Modified Discrete Langevin Model

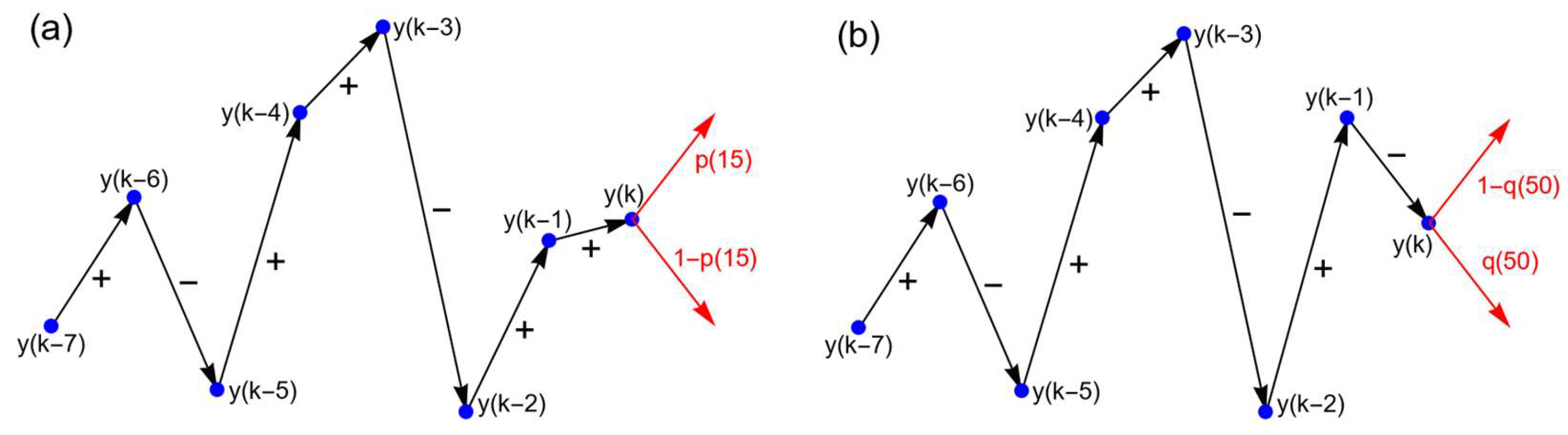

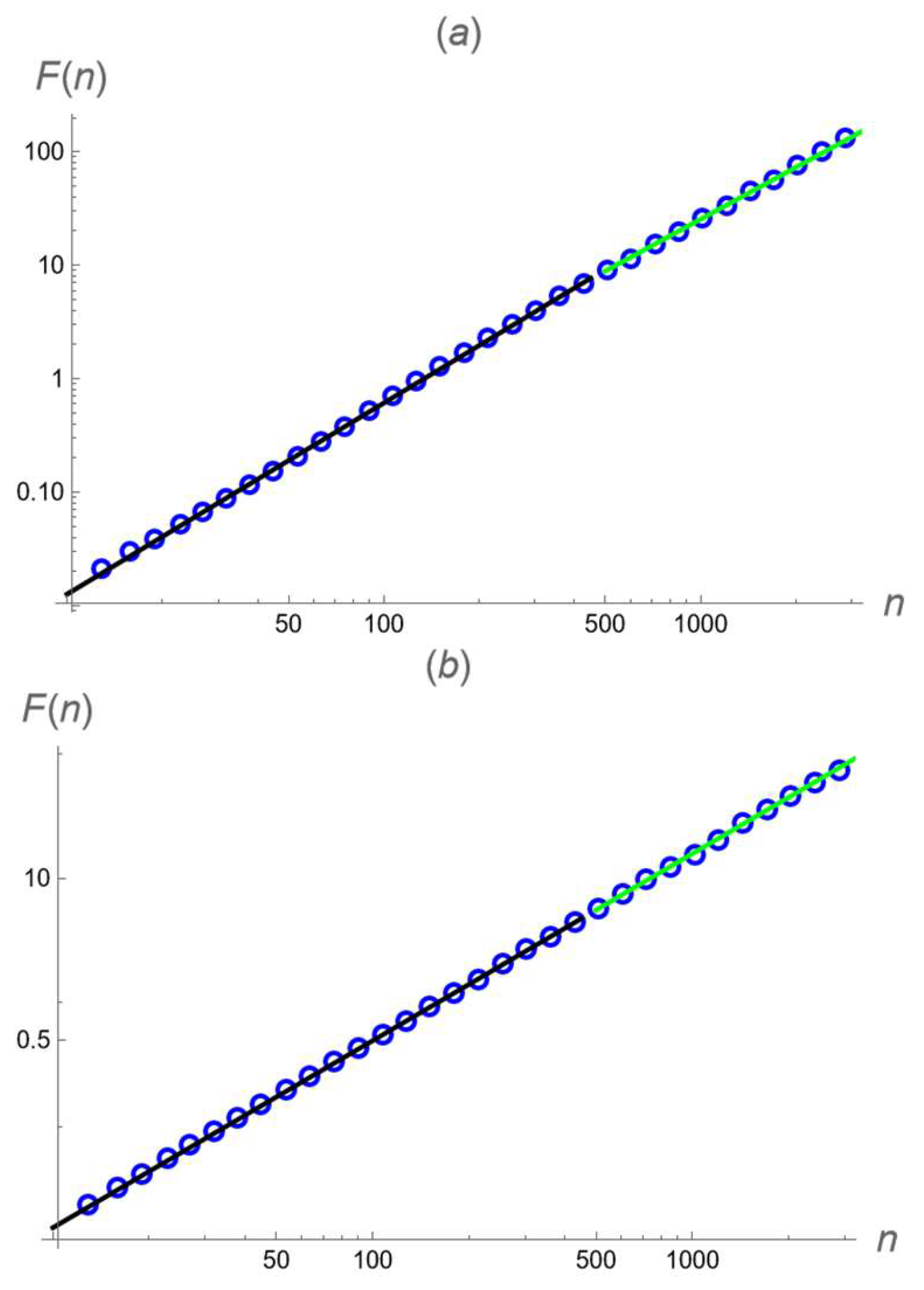

2.3. The Hurst Exponent

2.4. Comparison with Fractional Brownian Motion

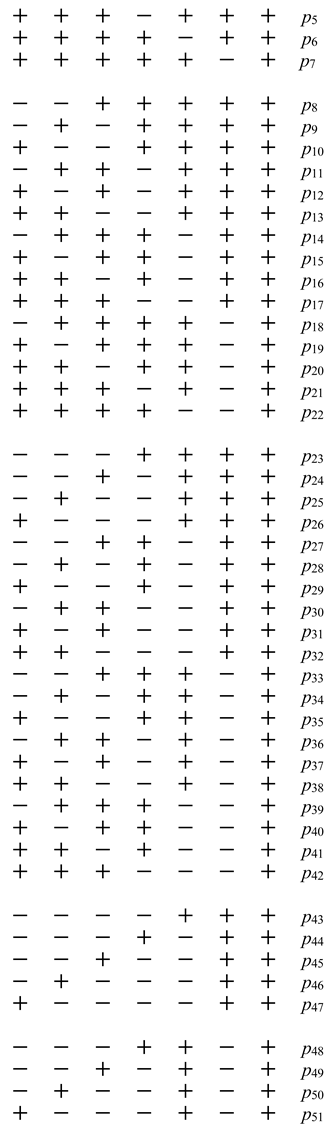

3. Asymmetric Persistence

4. Reconstruction of the Drift and Diffusion Functions from Time Series

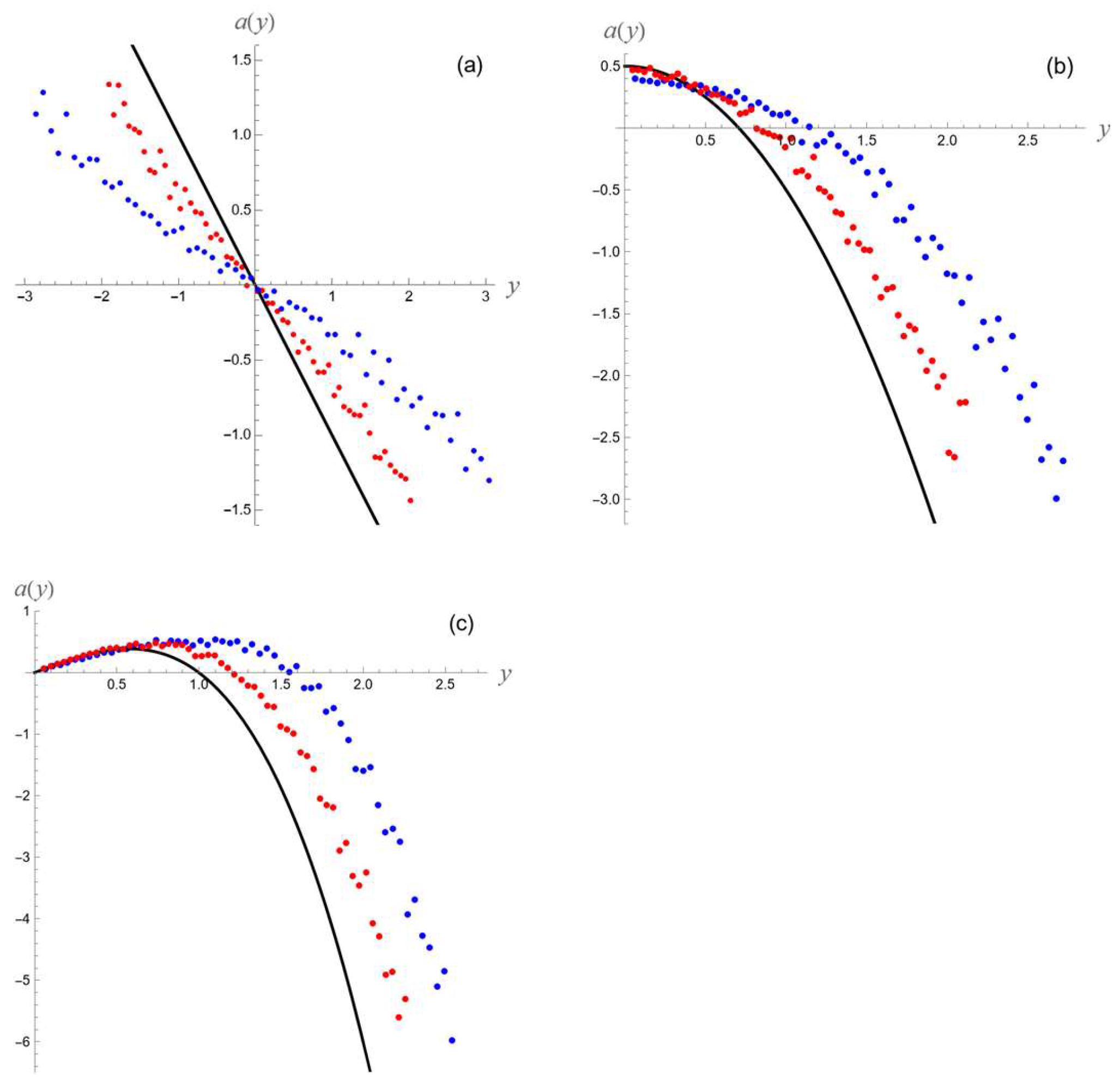

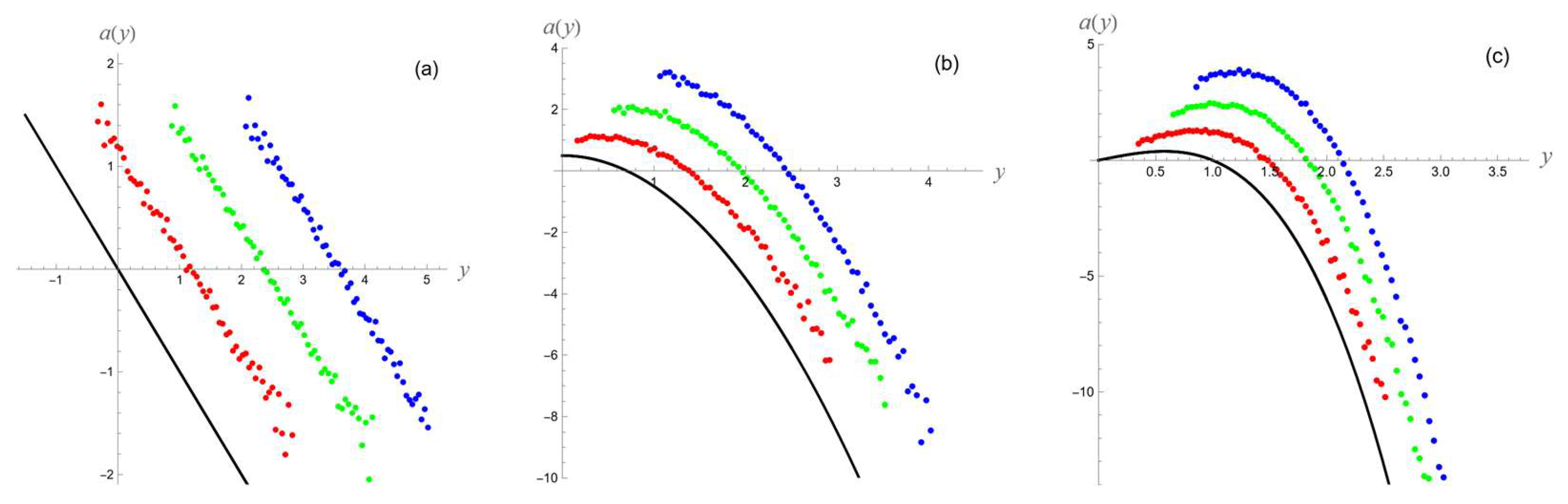

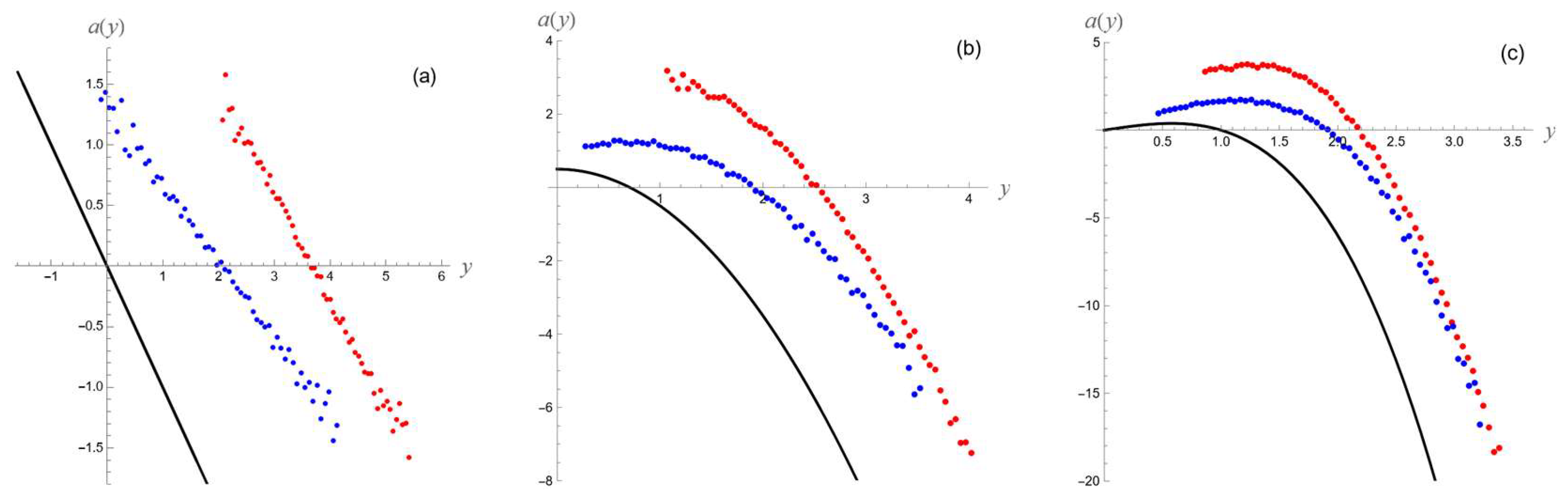

4.1. Symmetric Persistence

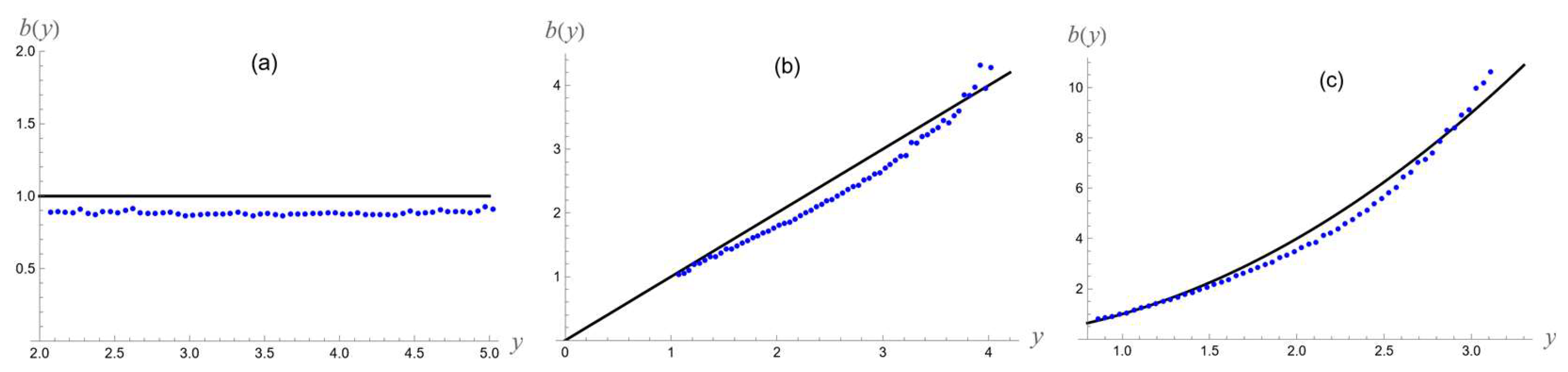

4.2. Antisymmetric Persistence

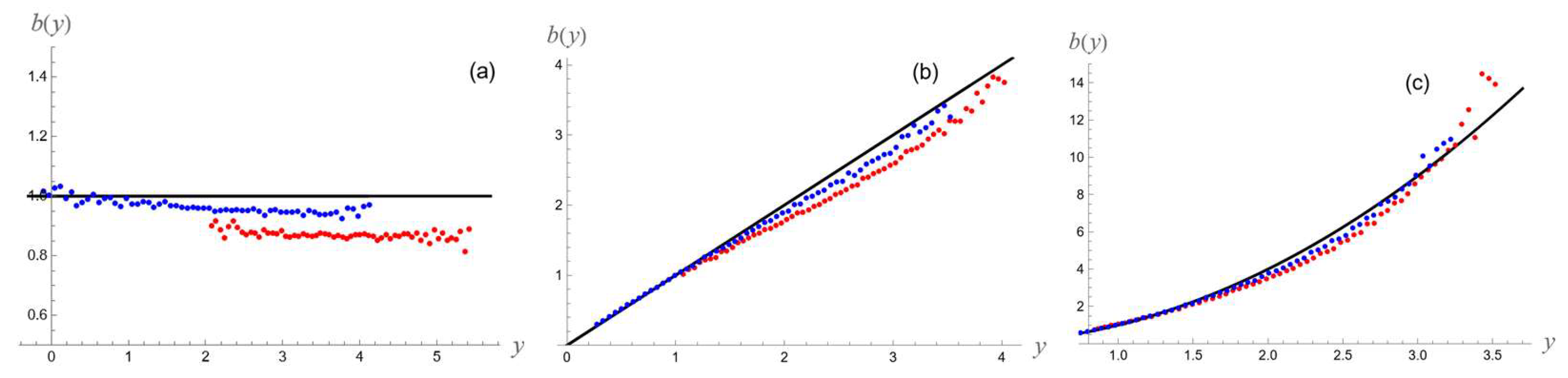

4.3. Asymmetric Persistence

5. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Franses, P.H.; Paap, R. Modelling asymmetric persistence over the business cycle, Econometric Institute Research Papers, 1998, (No. EI 9852). Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/1765/1525.

- Rossetto, V. The one-dimensional asymmetric persistent random walk, J. Stat. Mech., 2018, 043204. [CrossRef]

- Czechowski, Z.; Telesca, L. Construction of A Langevin model from time series with a periodical correlation function: Application to wind speed data, Phys. A 2013, 392, 5592-5603. [CrossRef]

- Czechowski, Z. Reconstruction of the modified discrete Langevin equation from persistent time series. Chaos 2016, 26, 053109. [CrossRef]

- Czechowski, Z. Discrete Langevin-type equation for p-order persistent time series and procedure of its reconstruction. Chaos, 2021, 31, 063102. [CrossRef]

- Kubo, R. The Fluctuation-Dissipation Theorem. Rep. Prog. Phys. 1966, 29, 255-284. [CrossRef]

- Mainardi, F.; Mura, A.; Tampieri, F. Brownian motion and anomalous diffusion revisited via a fractional Langevin Equation. Mod. Probl. State Phys. 2009, 8, 3 (2009); E-print http://arxiv.org/abs/1004.3505.

- Kantelhardt, J.W; Koscielny-Bunde, E.; Rego, H.H.A.; Havlin, S.; Bunde, A. Detecting long-range correlations with detrended fluctuation analysis. Physica A 2001, 295, 441- 454.

- Kantelhardt, J.W. Fractal and multifractal time series. arXiv: 2008, 0804.0747v1, 1-59. [CrossRef]

- Siegert, S; Friedrich, R.; Peinke, J. Analysis of data sets of stochastic systems. Phys. Lett. A 1998, 243, 275-280. [CrossRef]

- Grasman, J.; van Herwaarden; O. A. Asymptotic Methods for the Fokker-Planck Equation and the Exit Problem in Applications. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany, 1999.

- Oksendal, B. Stochastic differential equations: an introduction with applications; Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany, 1998.

- Mandelbrot, B.B.; Van Ness, J.W. Fractional Brownian Motions, Fractional Noises and Applications. SIAM Rev. 1968, 10, 422-437. [CrossRef]

- Sura, P.; Barsugli, A note on estimating drift and diffusion parameters from timeseries. J. Phys. Lett. A 2002, 305, 304-311. [CrossRef]

- Gottschal, J.; Peinke, J. On the definition and handling of different drift and diffusion estimates. New J. Phys. 2008, 10, 083034. [CrossRef]

- Anteneodo, C.; Riera, R. Arbitrary order corrections for finite-time drift and diffusion coefficients. Phys. Rev. E 2009, 80, 031103. [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, R.; Peinke, J.; Sahimi, M.; Reza Rahimi Tabar, M. Approaching complexity by stochastic methods: From biological systems to turbulence. Physics Reports 2011, 506(5), 87–162. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).