1. Introduction

In the past decades, thermal annealing has progressed toward shorter cycles with higher temperatures. Crystallization by furnace requires high-temperature heat treatment, which causes long diffusion length and fails the small channel electron devices. To improve the impurity diffusion, Rapid Thermal Annealing (RTA) was used to replace the furnace annealing. Current spike RTA has a temperature ramp up at 400 °C/s to decrease the thermal diffusion effect. One major limitation of spike RTA is that the irradiation energy must be larger than the energy bandgap (EG) of the materials. However, the UV-visible light irradiation energy of RTA is lower than the wide EG dielectrics in the backend of Integrated Circuits (ICs). Although indirect heating is available by Si substrate, the annealing effect on backend devices is insufficient. Besides, the maximum temperature for backend IC process is limited to 400 °C to prevent damage to frontend CMOS transistors.

In this study, we propose a new annealing method to improve the device quality for backend devices on isolation oxide. To further improve the impurity diffusion, a nanosecond (ns) pulsed laser is used. The proposed idea was verified by the large enhancement of 75 fF/μm

2 capacitance density and high dielectric constant (high-κ) of 67.8 by using 15 ns laser annealing, in the ZrO

2 metal-insulator-metal (MIM) device. These are the highest κ value and capacitance density reported in literature [

1,

2,

3]. It is important to notice that the laser light energy significantly lower than energy bandgap of material, where the mechanism is due to the surface plasma effect [

4] to create high-temperature on metal surface and heat up the ZrO

2 dielectric. The temperature profile under various laser annealing density is calculated using Matrix Laboratory (MATLAB). The peak temperature at TiN metal surface can be as high as 870°C, which can anneal above ZrO

2 dielectric efficiently. On the other hand, the temperature is largely decreased below the 400°C within a TiN thickness of 30 nm, which meets the requirement with little effect on frontend CMOS transistors. This technology can improve the devices performance for Monolithic Three-Dimensional (M3D) integration on the backend of advanced Integrated Circuit (IC). Such M3D integration is crucible to improve the circuit speed and switching power consumption beyond the most advanced microprocessors [

5,

6,

7].

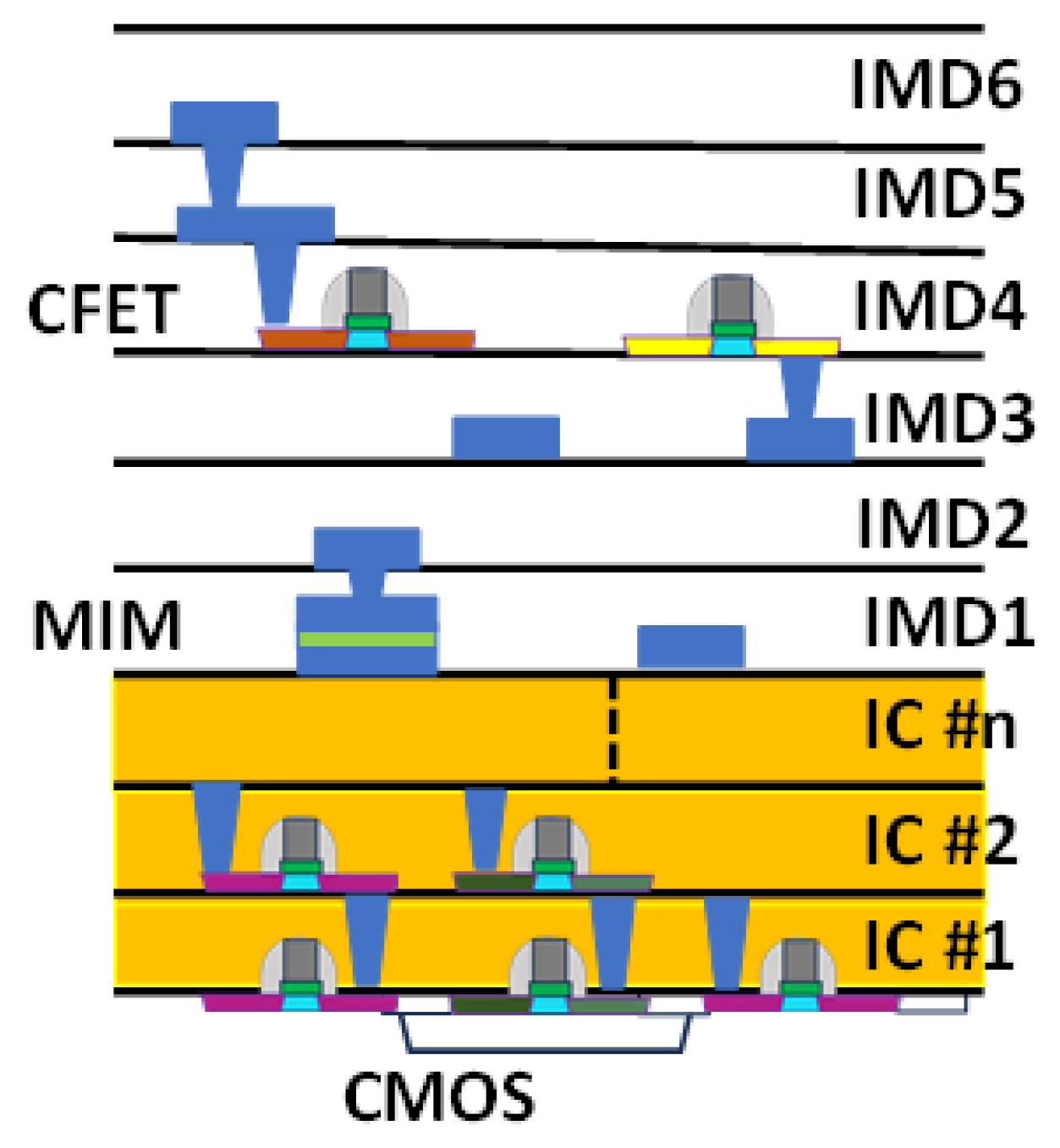

Figure 1.

Monolithic Three-Dimensional (M3D) Integrated Circuit (IC).

Figure 1.

Monolithic Three-Dimensional (M3D) Integrated Circuit (IC).

3. Results

The heat diffusion equation governing the temperature evolution in both the TiN and ZrO

2 layers is given by:

Where α is the thermal diffusivity, ∇

2T is the Laplacian of the temperature (describing the spatial derivatives of temperature in both radial and axial directions), k is thermal conductivity,

ρ is material density, c

p is specific heat capacity, Q is the heat source term (which is zero for ZrO

2, but non-zero in TiN due to laser absorption). The heat is in a Gaussian profile in the radial direction because the laser beam typically has a Gaussian intensity profile. In the radial direction, the heat source term is expressed as:

Where A

TiN is absorbance of TiN layer, T

ZrO2 is transmittance of ZrO

2, E is laser energy, A is spot size, t is laser irradiation time and σ is related to the focal radius, representing the width of the Gaussian beam profile, n

1 is the refractive index of ZrO

2 and n

2 is the refractive index of air. The ZrO

2 dielectric exhibited negligible absorption of laser energy, as its bandgap (5 to 5.8 eV) [

8,

9] significantly surpasses the photon energy of 2.33 eV. The increase in temperature can be attributed to the heat converted from the photon energy absorbed by TiN layer.

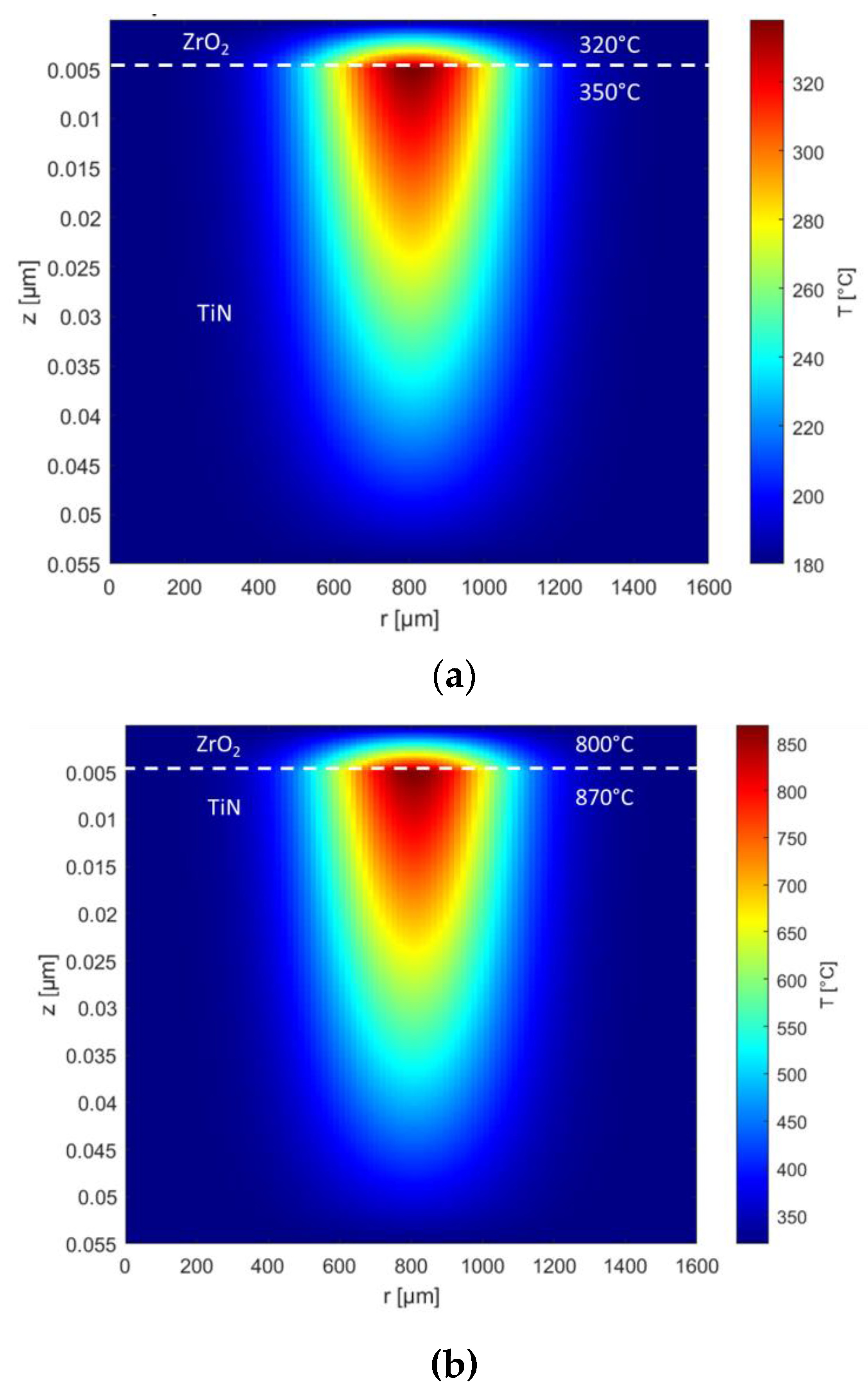

Figure 2 (a)-(c) present the simulation results of the temperature increase when laser irradiation with an energy density fluence of 5.4, 16.2 and 21.6 J/cm

2. TiN, a good plasmonic media is used as a metal layer to enhance the absorption of the irradiated pulse laser and diffuse the heat to ZrO

2 insulator layer above it [

10,

11]. The calculation displayed that the average temperature increases to 350 °C, 870 °C and 1450 °C at TiN surface and as heat diffuses, the temperature at ZrO

2 is 320 °C, 800 °C and 1300 °C, as the laser annealed energy density fluences are 5.4 J/cm

2, 16.2 J/cm

2 and 21.6 J/cm

2, respectively.

Further, Lu et al. reported that ammonia (NH

3) plasma pre-treatment is crucial before the deposition of high-κ materials, as it significantly enhances interface properties [

12]. Edwards et al. reported that NH

3 plasma treatment prior to SiN deposition significantly improves the degradation characteristics of AlGaN–GaN high-electron-mobility transistor (HEMTs) by reducing current collapse and eliminating gate lag after extended direct current bias [

13]. This process strengthens bonds, making the structure more resistant to hot electron damage and passivating defects caused by it.

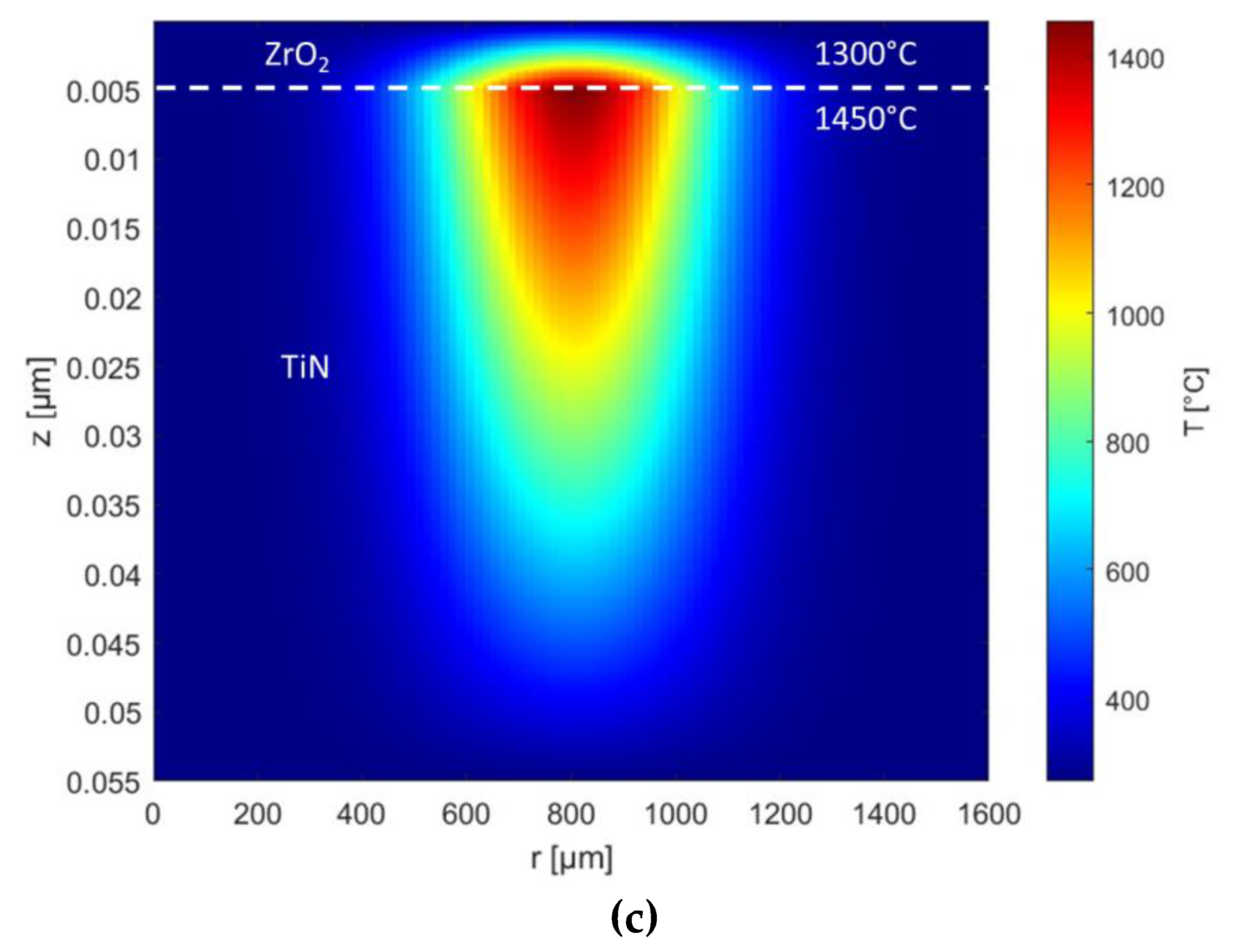

Figure 3 (a)-(d) shows the C–V characteristics of Ni/ZrO

2/TiN MIM capacitors before and after laser annealing under NH

3+ plasma treatment conditions at 2000 W (60 s and 120 s), 2400 W (60 s) and 2800 W (60 s) respectively. The merits of using Ni electrode are the high work-function and reactive-ion-etching-friendly process [

14]. For a 532 nm laser annealing with 2400 W 60s NH

3+ plasma treatment in

Figure 3 (c), the capacitance density increases monotonically with increasing laser-power that is 51.9 fF/um

2 for 5.4 J/cm

2 and 75 fF/um

2 for 16.2 J/cm

2 much better than the control devices before laser annealing, with a capacitance density of 41.7 fF/um

2 at -0.2 V. Therefore, the 2400 W 60s NH

3+ surface treatment can make better formation and density of nitridation layer. Such nitridation layer can effectively prevent the ZrO

2 and TiN reaction at high temperature to form TiON. Under this condition, the plasma treatment significantly improves the TiN

x surface for laser annealing. Other conditions, such as lower power (2000 W) or excessive power (2800 W), did not reach such high capacitance density due to either insufficient or excessive modification of the TiN

x surface. Prolonged treatment times are less effective than the increased NH

3+ plasma density. Thus, the 2400 W 60s NH

3+ plasma condition represents an optimal balance on TiN surface nitridation, resulting in the best capacitance performance. Further when ZrO

2/TiN is laser annealed at 532 nm using 21.6 J/cm

2 energy density, it raises the temperature at TiN surface to 1450 °C and heat diffusion to ZrO

2 cause the temperature to raise to 1300 °C.

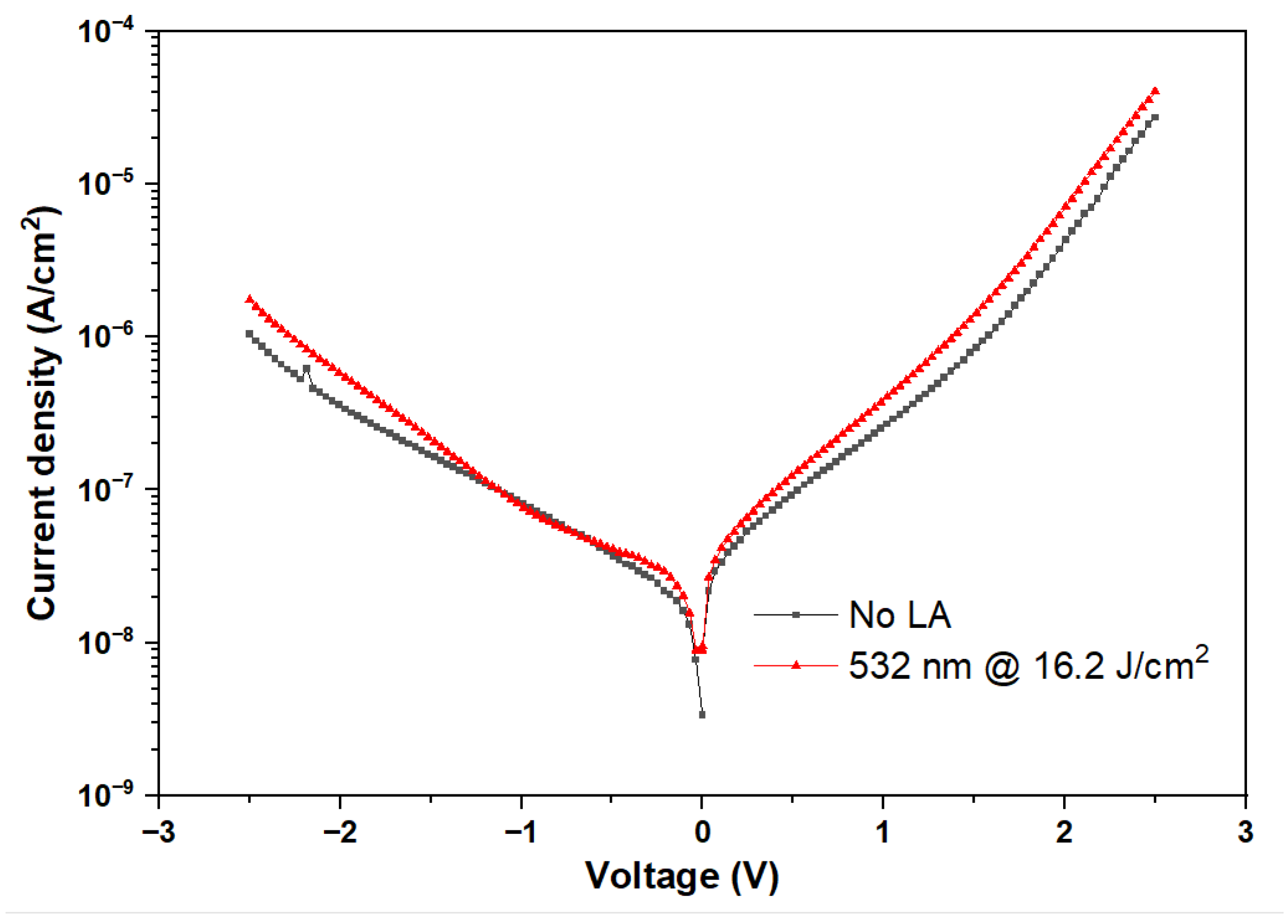

Figure 4 highlights the J–V plot of Ni/ZrO

2/TiN capacitor before and after laser annealing at 532 nm 16.2 J/cm

2. The leakage current increases slightly by 2.67 × 10

-8 A/cm

2 at -0.2 V than the control devices before laser annealing, with leakage current of 2.17 × 10

-8 A/cm

2 at -0.2 V.

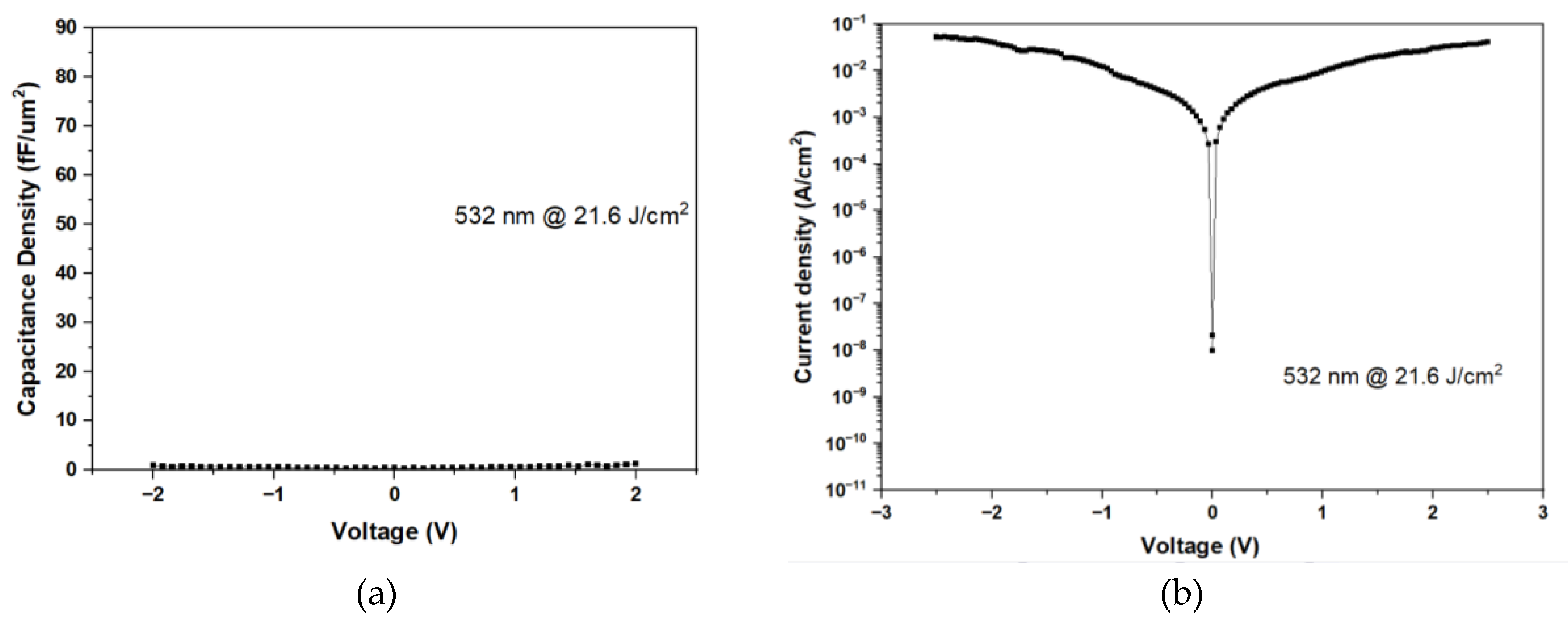

Figure 5 (a) and (b) shows the C-V and (b) J-V analysis for Ni/ZrO

2/TiN MIM capacitors at higher 21.6 J/cm

2 laser annealing. No capacitance can be measured and the Ni/ZrO

2/TiN MIM device behaves like a small resistor. As shown in

Figure 2(c), the temperature at TiN surface can raise to 1450 °C and heat diffusion to ZrO

2 cause the temperature to raise to 1300 °C. The laser energy is large enough and can cause thermal stress by local temperature rise exceeding the fracture strength of the film, the film will be wrinkled, cracked or even shed leading to failure of device [

15]. Although these temperatures are still less than the melting temperature of ZrO

2 and TiN, such high temperature may cause ZrO

2 and TiN reaction, bond breaking, free Zr and Ti metals and shorting the capacitor.

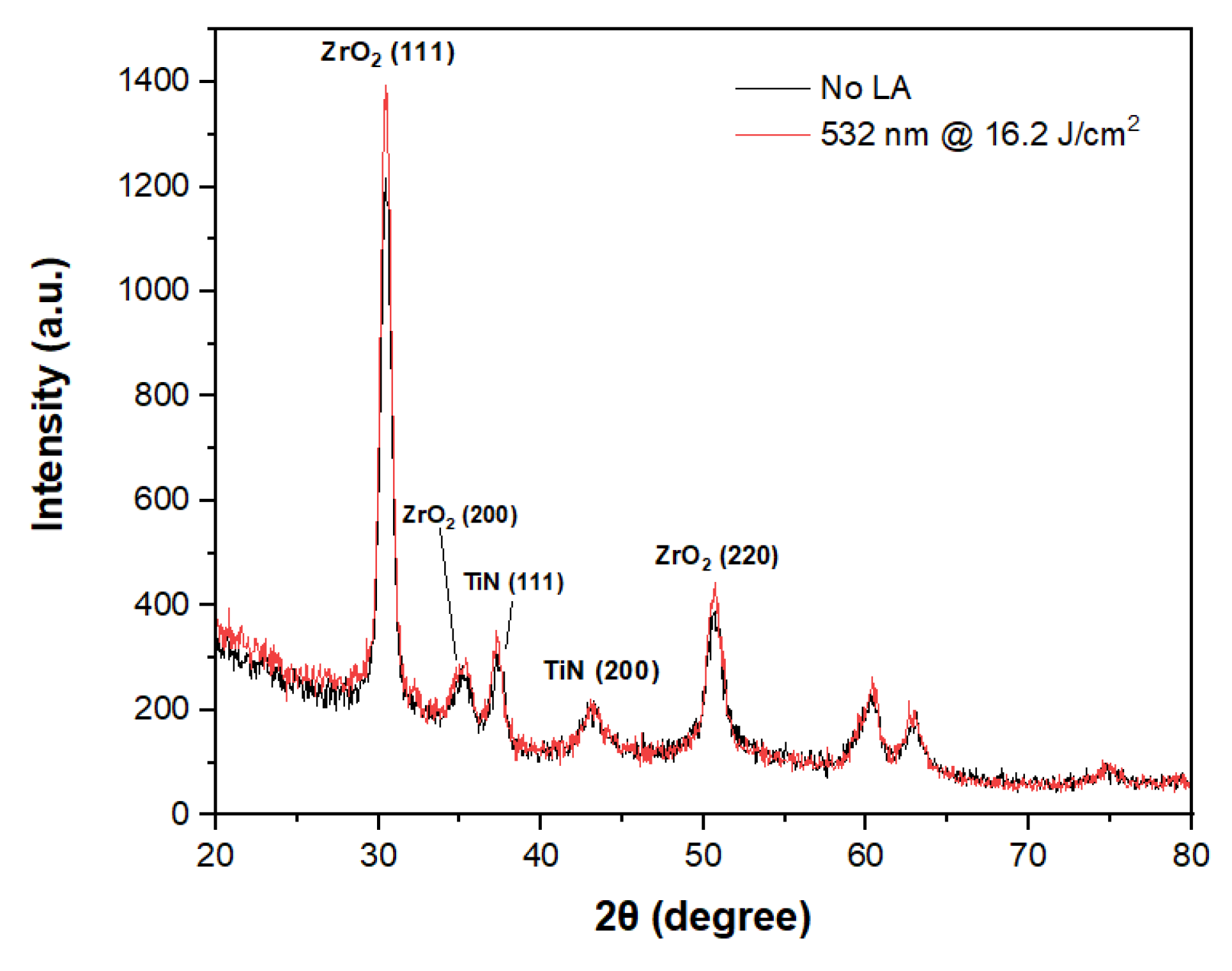

The slight increase in leakage current after laser annealing is attributed to larger grain size, as seen in XRD (

Figure 6). The grain size of the ZrO

2 can be calculated by using Scherrer formula as

where D is the grain size, λ is the X-ray wavelength, k =0.9 is a dimensionless shape factor, β is the line broadening at half the maximum intensity (FWHM), and θ is the Bragg angle. The calculated grain sizes of ZrO

2, before and after laser annealing at 532 nm, 16.2 J/cm

2 is 6.85 nm and 8.21 nm respectively. This is similar to findings in TiO

2 MIM capacitors [

16]. The annealing enhances ZrO

2 crystallinity, particularly in the high-κ cubic phase, evident from stronger XRD peaks. This improved crystallinity explains the higher capacitance density.

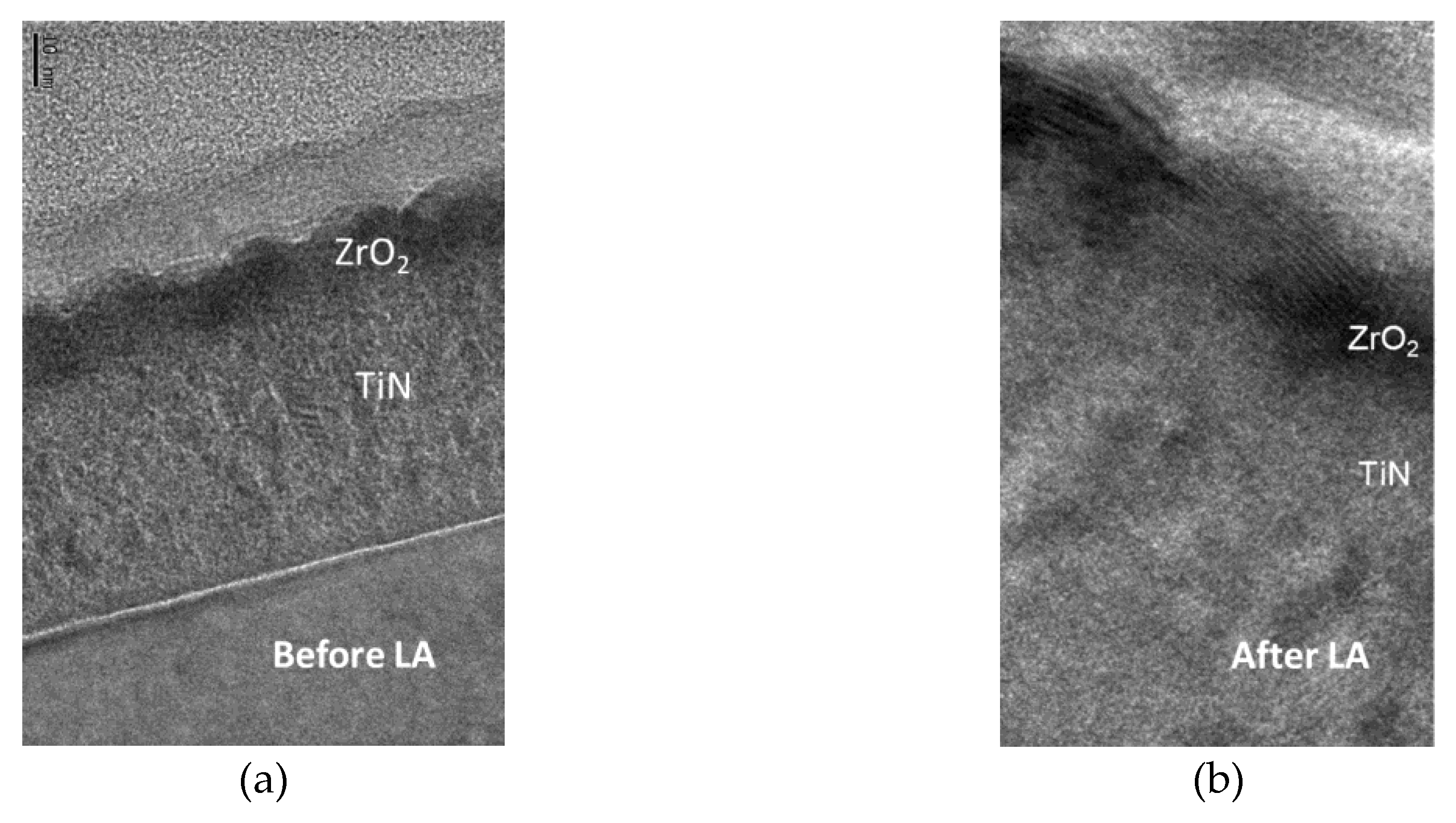

The TEM analysis is used to study the laser annealing condition.

Figure 7 (a) and (b) further shows the cross-sectional TEM image of Al/ZrO

2/TiN structures before and after laser annealing. Clear better crystallization of ZrO

2 is observed after laser annealing, which is consistent with the XRD results. In the TEM image, the relatively rough top interface is Al rather than Ni. The samples analysed by TEM cannot contain magnetic substances such as iron/cobalt/nickel and other materials.

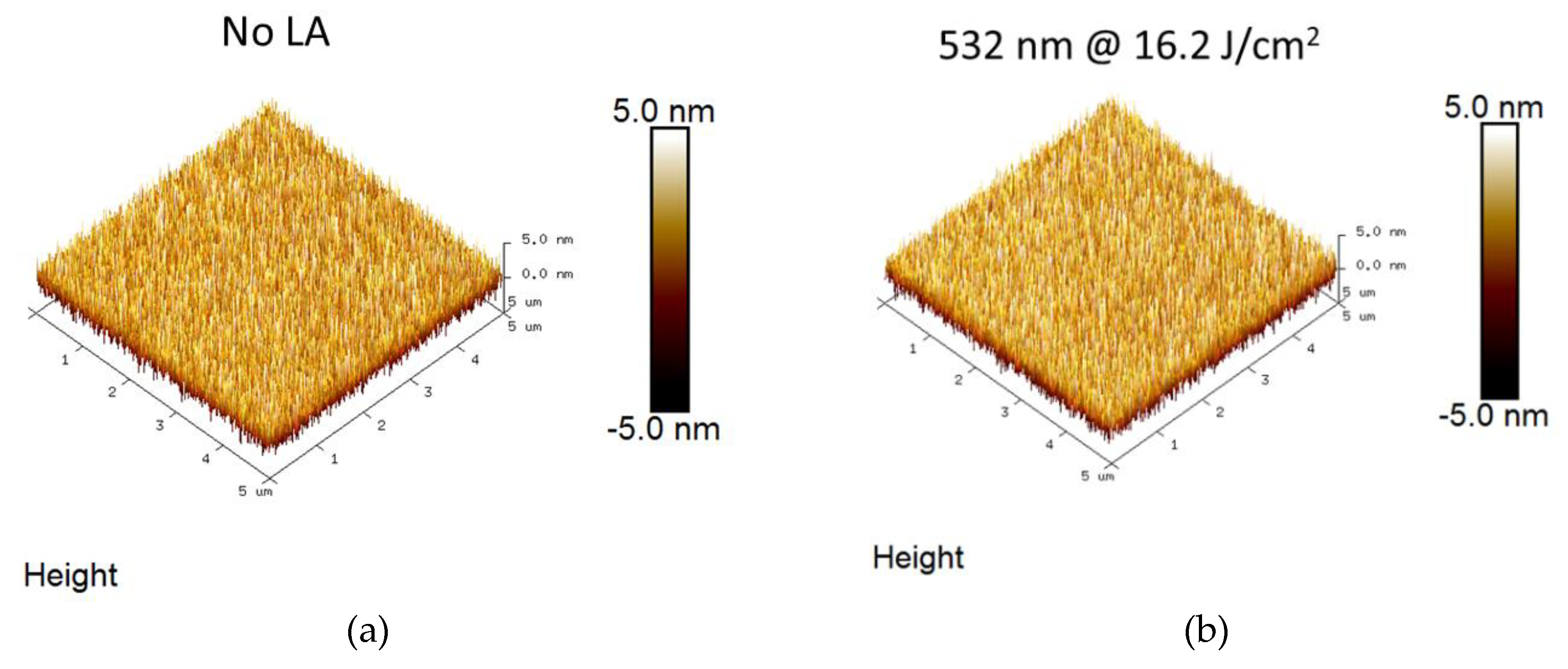

The surface morphology of ZrO

2 before and after laser annealing samples is studied by AFM images, as shown in

Figure 8 (a) and (b) using 5 µm × 5 µm scans. The root-mean-square roughness of ZrO

2 before laser annealing was found to be around 1.14 nm, whereas the roughness of the ZrO

2 after 532 nm laser annealing using 16.2 J/cm

2 was 1.25 nm. In the process of laser annealing, the raise in temperature enables the grain boundaries migration and causes more grains coalescence. More energy is available for the atoms to diffuse and lower surface energy grains get enlarge at high temperatures. The major growth in grain as observed from XRD analysis highlights the enhanced surface roughness for the laser annealed of ZrO

2 samples.