Submitted:

24 October 2023

Posted:

24 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

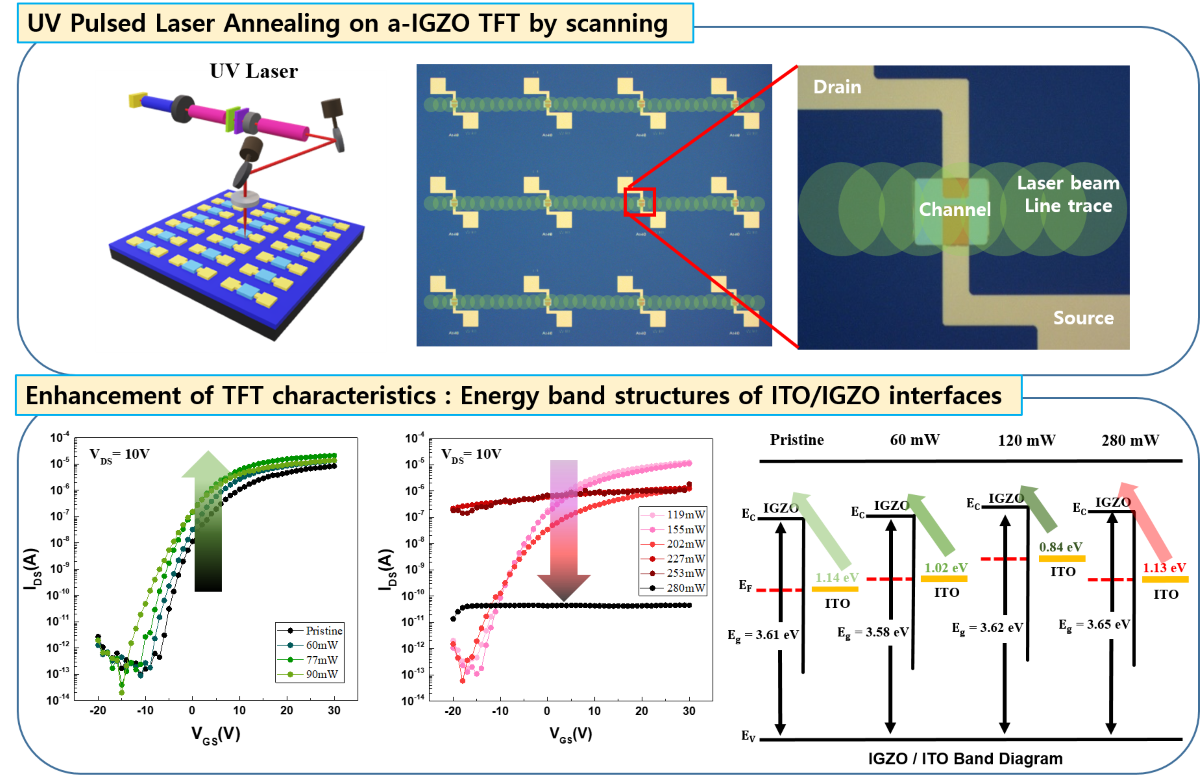

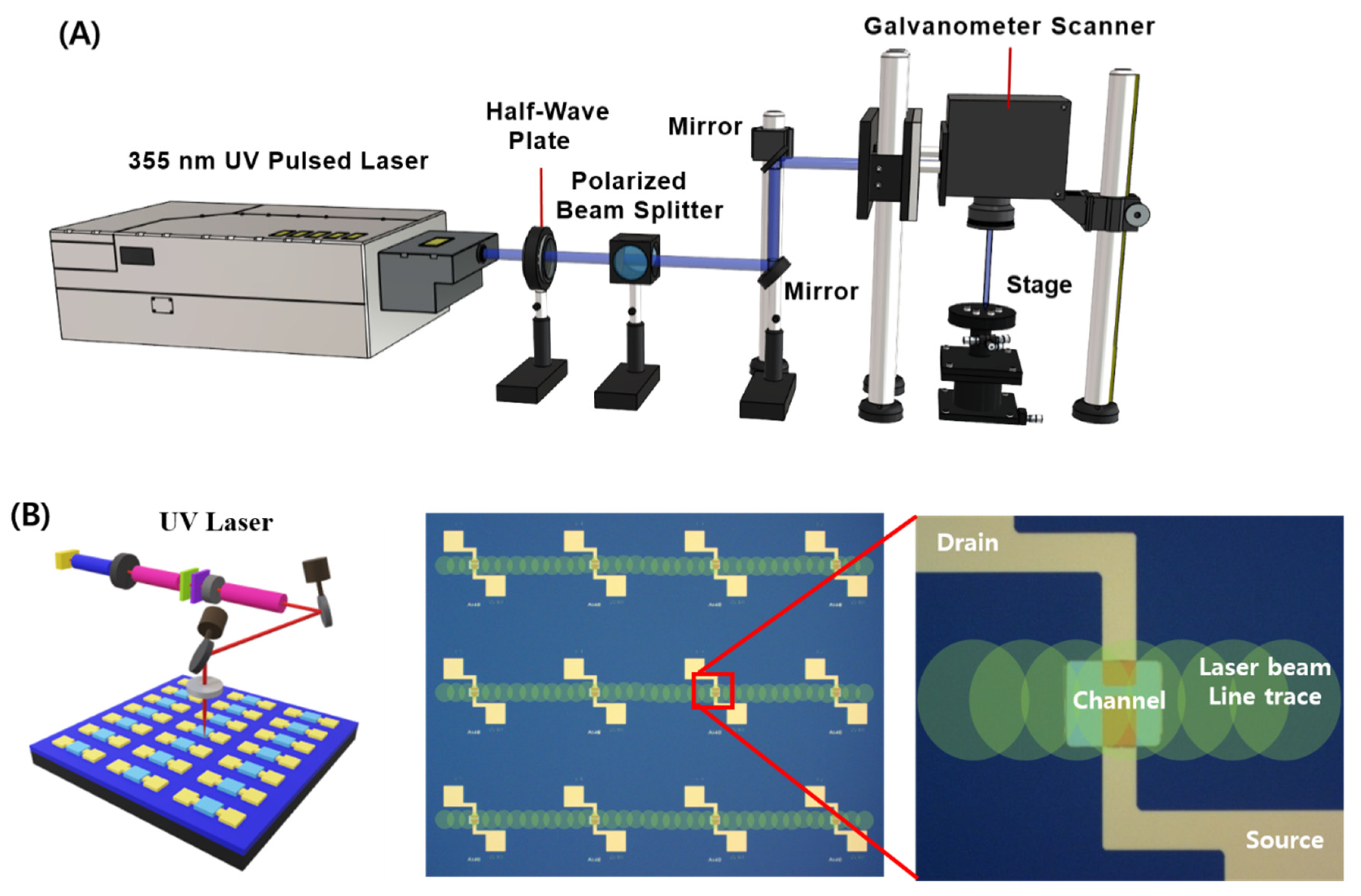

2. Experimental Methods

3. Results and Discussion

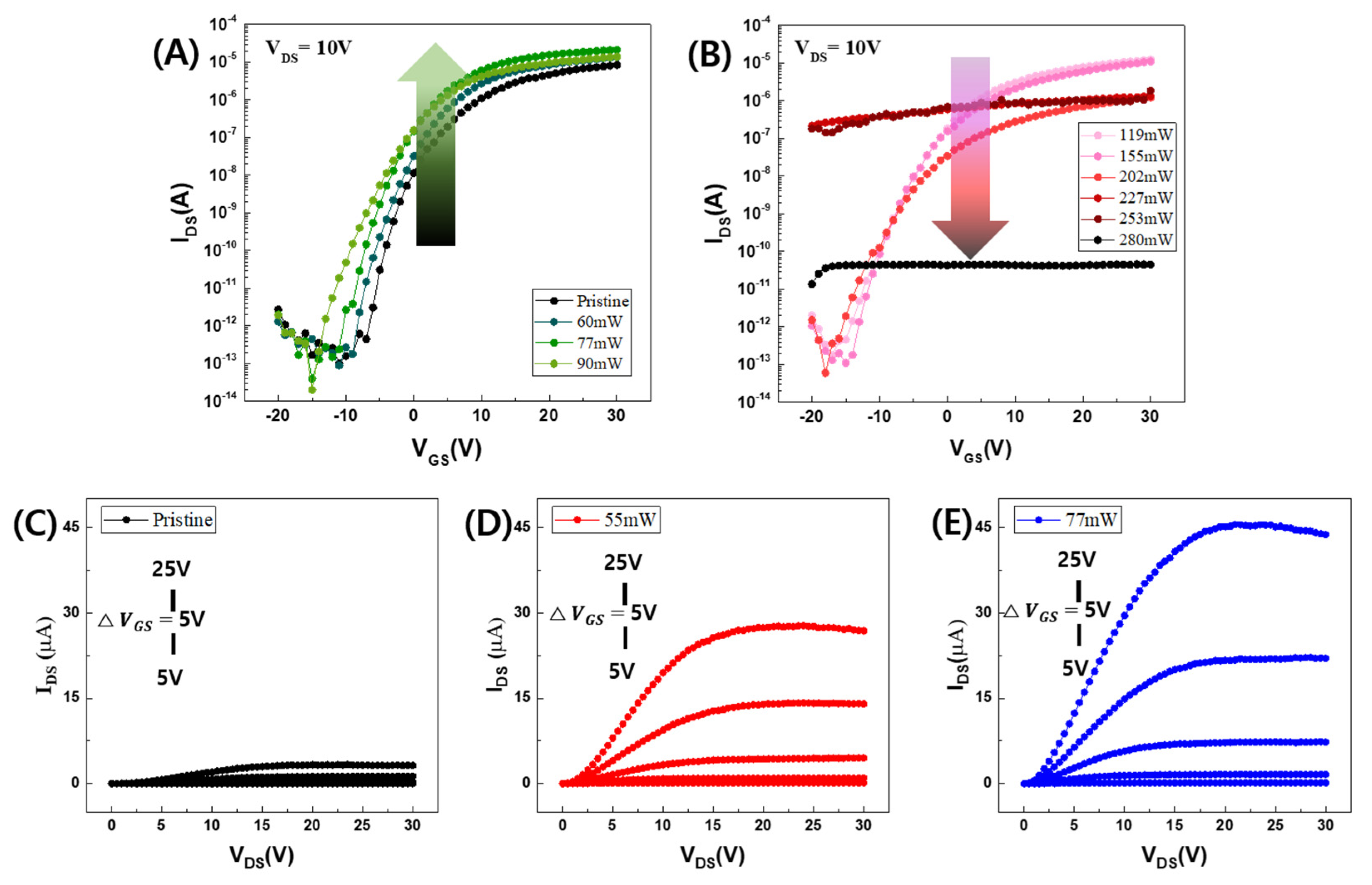

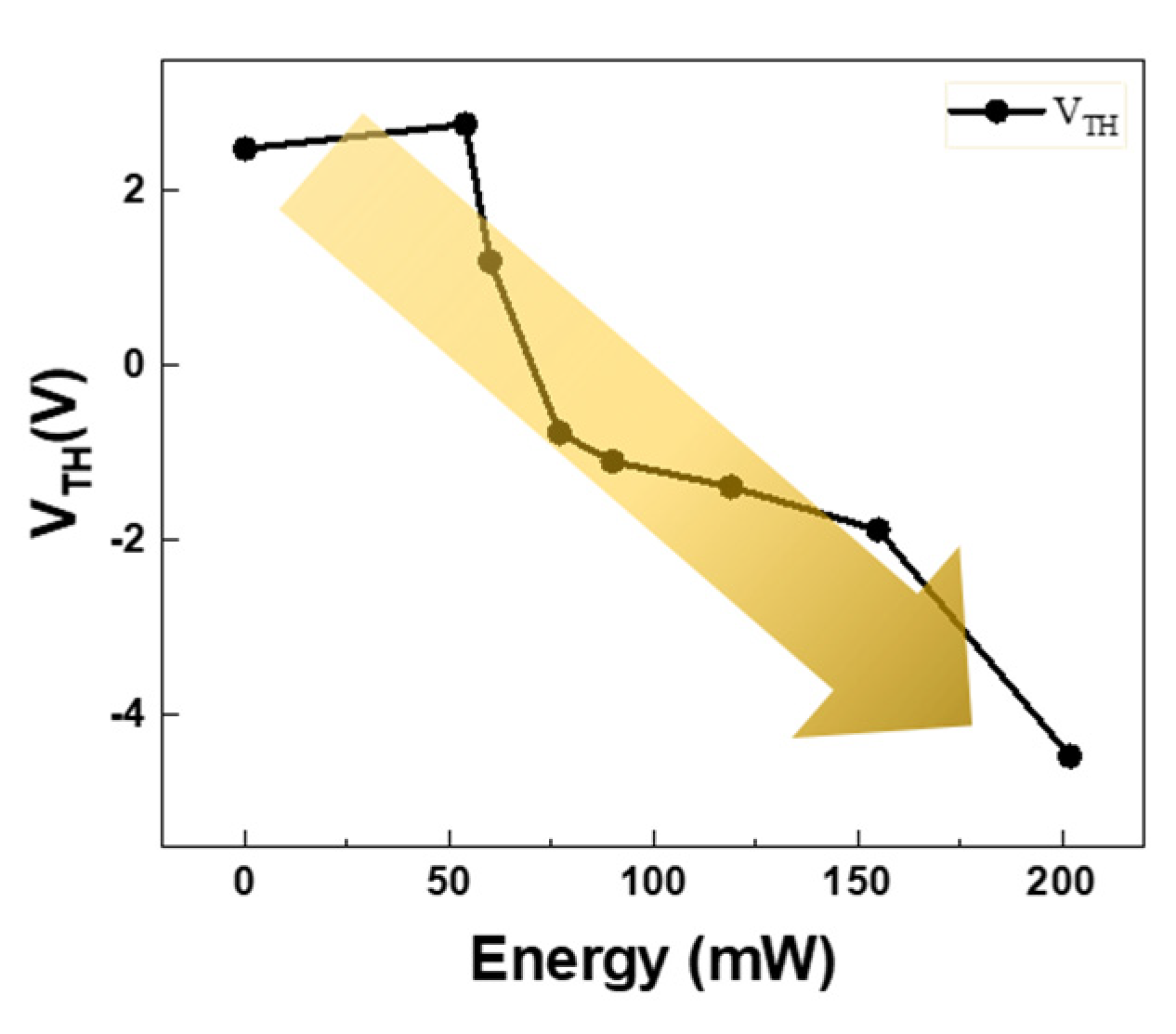

3.1. Current-Voltage Characteristics Depending on the UV Pulsed Laser Beam Energy

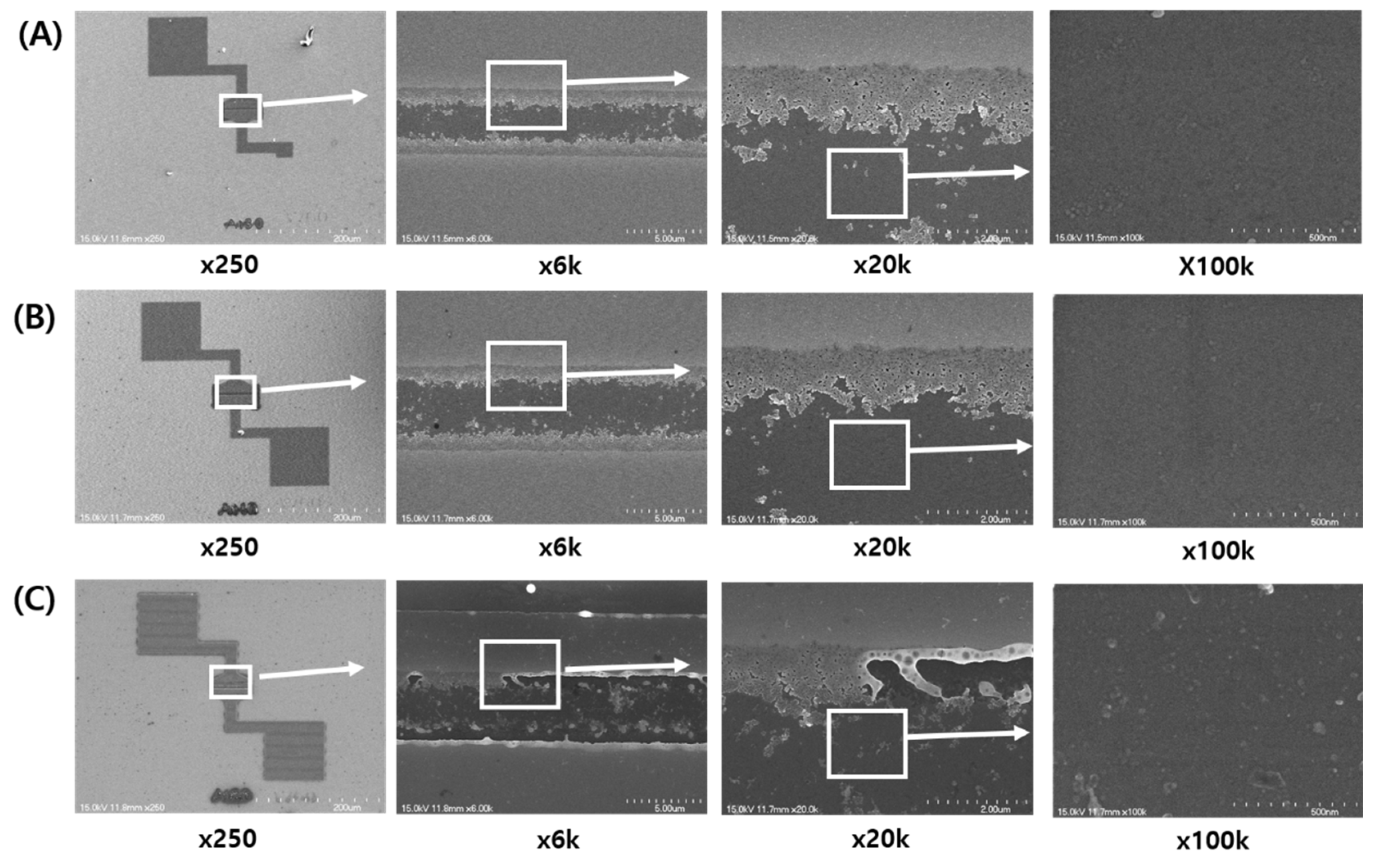

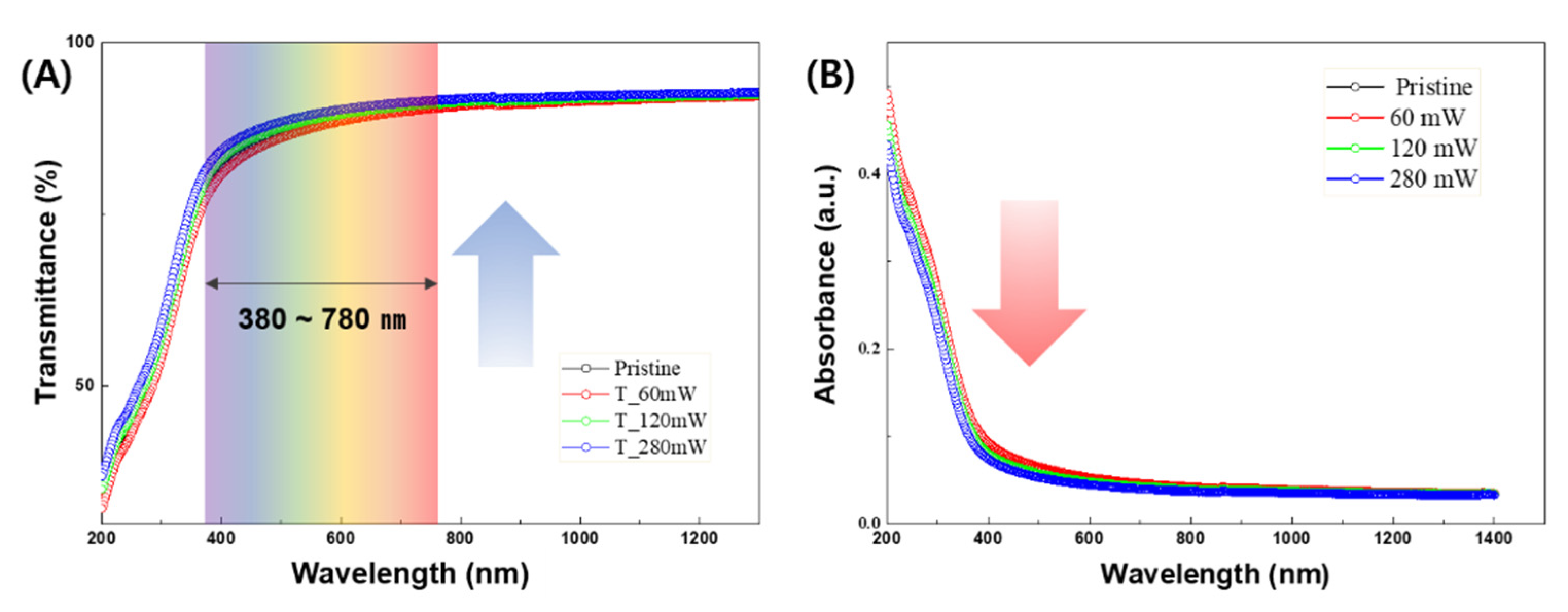

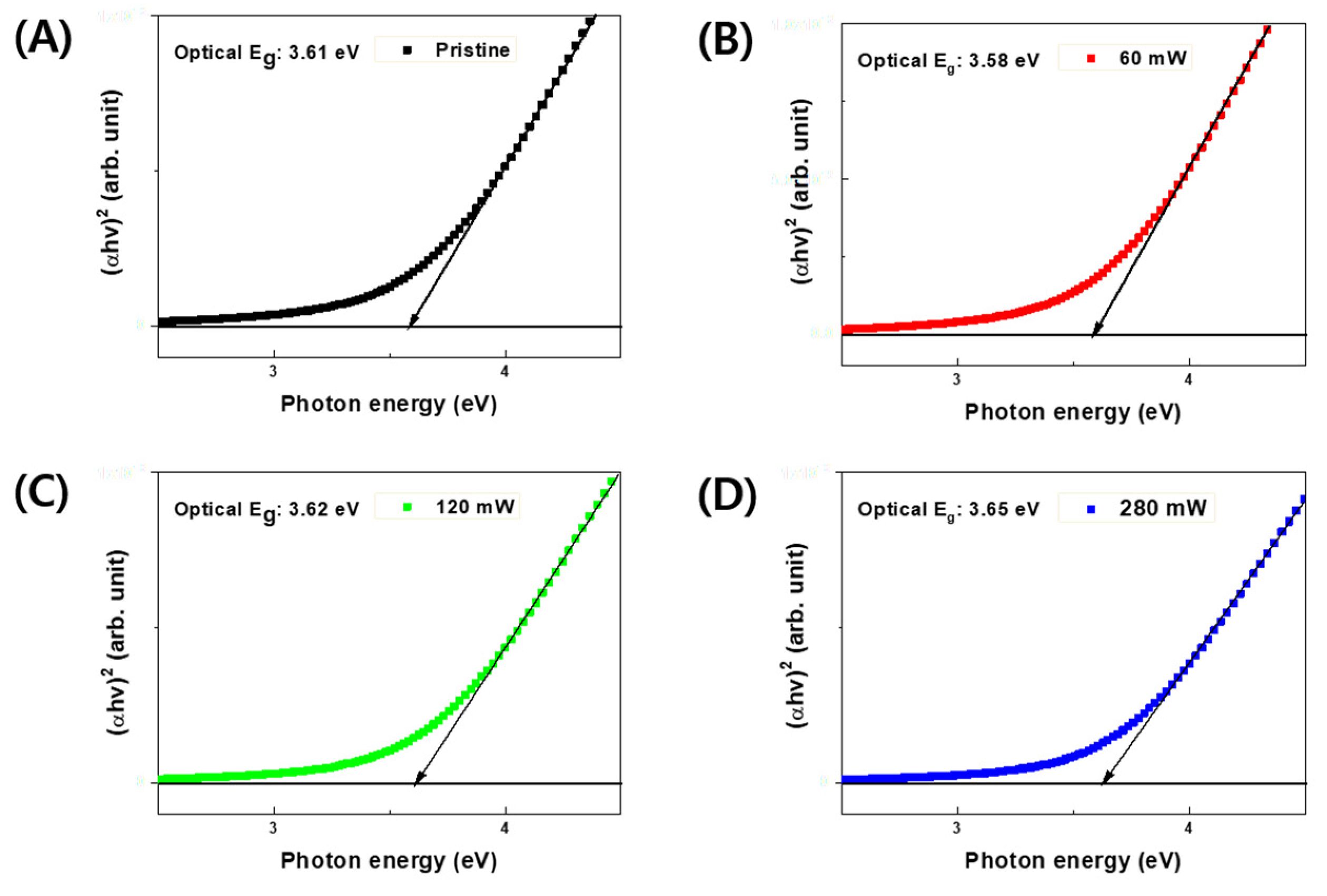

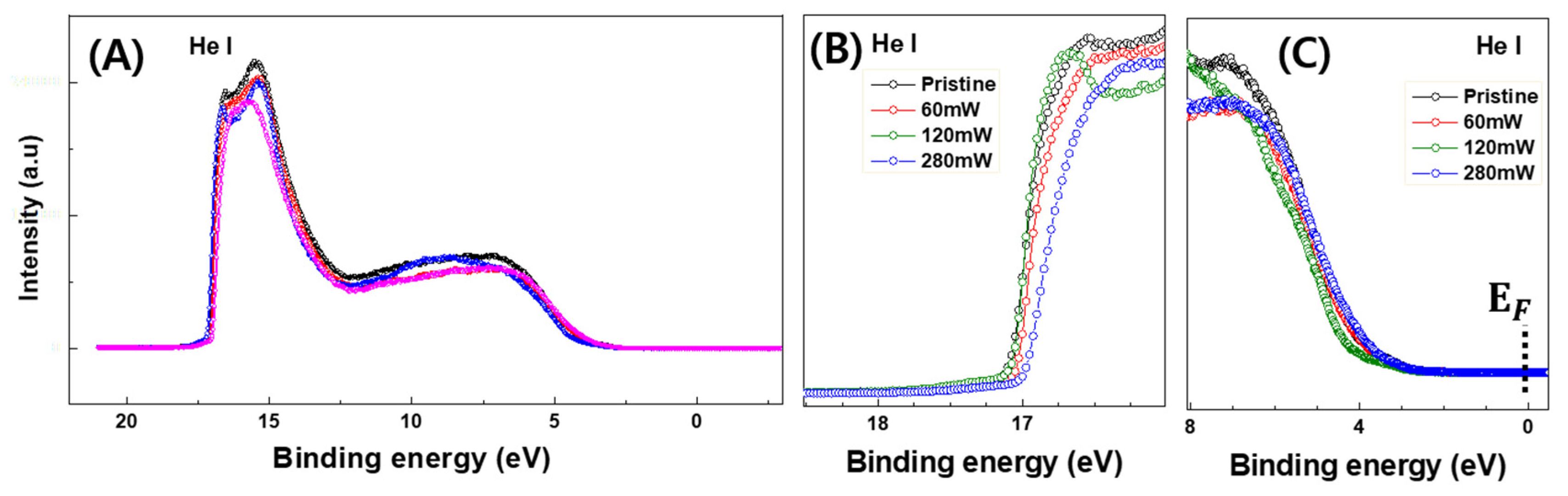

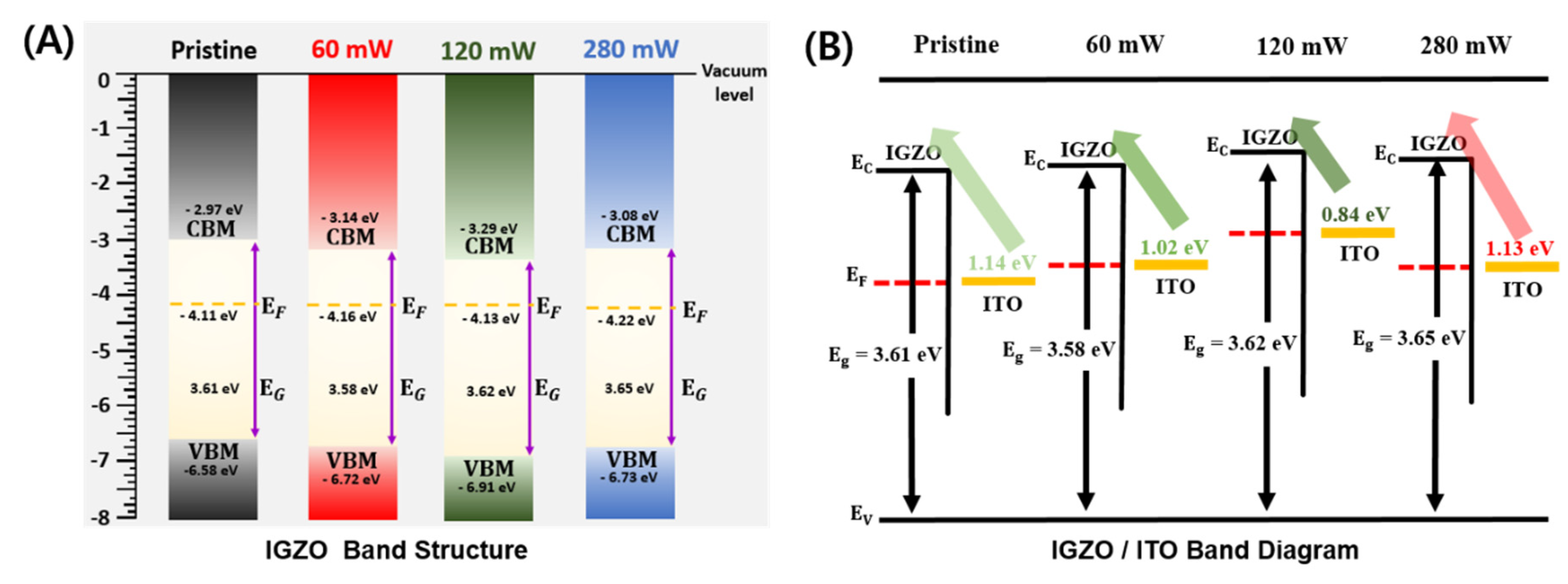

3.2. Structural Characteristics and Energy Band Analysis with Laser Beam Energy

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Naqi, M.; Cho, Y.; Kim, S. High-Speed Current Switching of Inverted-Staggered Bottom-Gate a-IGZO-Based Thin-Film Transistors with Highly Stable Logic Circuit Operations. ACS Applied Electronic Materials 2023, 5, 3378–3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortunato, E.; Barquinha, P.; Martins, R. Oxide Semiconductor Thin-Film Transistors: A Review of Recent Advances. Advanced Materials 2012, 24, 2945–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, X.; Yuan, Y.; Yin, X.; Yan, S.; Xin, Q.; Song, A. High-Performance Thin-Film Transistors With Sputtered IGZO/Ga₂O₃ Heterojunction. IEEE Transactions on Electron Devices 2022, 69, 6783–6788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Striakhilev, D.; Park, B.-K.; Tang, S.-J. Metal oxide semiconductor thin-film transistor backplanes for displays and imaging. MRS Bulletin 2021, 46, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S.; Maeng, W.-J.; Kim, H.-S.; Park, J.-S. Review of recent developments in amorphous oxide semiconductor thin-film transistor devices. Thin Solid Films 2012, 520, 1679–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, K. Recent progress of oxide-TFT-based inverter technology. Journal of Information Display 2021, 22, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosono, H. Ionic amorphous oxide semiconductors: Material design, carrier transport, and device application. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids 2006, 352, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiya, T.; Hosono, H. Material characteristics and applications of transparent amorphous oxide semiconductors. NPG Asia Materials 2010, 2, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.M.; Liu, C.Y.; Sahoo, A.K. RF sputtering deposited a-IGZO films for LCD alignment layer application. Applied Surface Science 2015, 354, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troughton, J.; Atkinson, D. Amorphous InGaZnO and metal oxide semiconductor devices: an overview and current status. Journal of Materials Chemistry C 2019, 7, 12388–12414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiya, T.; Nomura, K.; Hosono, H. Present status of amorphous In–Ga–Zn–O thin-film transistors. Science and Technology of Advanced Materials 2010, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, D.H.; Kang, I.; Ryu, S.H.; Jang, J. Self-Aligned Coplanar a-IGZO TFTs and Application to High-Speed Circuits. IEEE Electron Device Letters 2011, 32, 1385–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jamblinne De Meux, A.; Bhoolokam, A.; Pourtois, G.; Genoe, J.; Heremans, P. Oxygen vacancies effects in a-IGZO: Formation mechanisms, hysteresis, and negative bias stress effects. physica status solidi (a) 2017, 214, 1600889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, K.; Ohta, H.; Takagi, A.; Kamiya, T.; Hirano, M.; Hosono, H. Room-temperature fabrication of transparent flexible thin-film transistors using amorphous oxide semiconductors. Nature 2004, 432, 488–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jianke, Y.; Ningsheng, X.; Shaozhi, D.; Jun, C.; Juncong, S.; Shieh, H.D.; Po-Tsun, L.; Yi-Pai, H. Electrical and Photosensitive Characteristics of a-IGZO TFTs Related to Oxygen Vacancy. IEEE Transactions on Electron Devices 2011, 58, 1121–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, H.; Matsuzaki, T.; Nagatsuka, S.; Okazaki, Y.; Sasaki, T.; Noda, K.; Matsubayashi, D.; Ishizu, T.; Onuki, T.; Isobe, A.; Shionoiri, Y.; Kato, K.; Okuda, T.; Koyama, J.; Yamazaki, S. Nonvolatile Memory With Extremely Low-Leakage Indium-Gallium-Zinc-Oxide Thin Film Transistor. IEEE Solid-State Circuits 2012, 47, 2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-W.; Cho, W.-J. Effects of vacuum rapid thermal annealing on the electrical characteristics of amorphous indium gallium zinc oxide thin films. AIP Advances 2018, 8, 015007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Yang, S.; Pan, C.; Li, X.; Zhang, J. Effect of Two-Step Annealing on High Stability of a-IGZO Thin-Film Transistor. IEEE Transactions on Electron Devices 2020, 67, 4262–4268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.K.; Kim, C.-K.; Park, J.W.; Kim, E.; Seol, M.-L.; Park, J.-Y.; Choi, Y.-K.; Park, S.-H.K.; Choi, K.C. Electro-Thermal Annealing Method for Recovery of Cyclic Bending Stress in Flexible a-IGZO TFTs. IEEE Transactions on Electron Devices 2017, 64, 3189–3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuh, C.-S.; Liu, P.-T.; Chou, Y.-T.; Teng, L.-F.; Sze, S.M. Role of Oxygen in Amorphous In-Ga-Zn-O Thin Film Transistor for Ambient Stability. ECS Journal of Solid State Science and Technology 2013, 2, Q1–Q5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K. H.; Kwon, H.-I.; Kwon, S. J.; Cho, E. S. Effects of the Pulse Repetition Numbers of Xenon Flash Lamp on the Electrical Characteristics of a-IGZO Thin Films Transistor. J Semi Tech Sci 2019, 19, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.-H.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, B.-K.; Jin, W.-B.; Kim, Y.; Chung, H.; Park, S. Scanning multishot irradiations on a large-area glass substrate for Xe-Arc flash lamp crystallization of amorphous silicon thin-film. International Journal of Thermal Sciences 2015, 91, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wager, J.F. TFT Technology: Advancements and Opportunities for Improvement. Information Display 2020, 36, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, T.; Saito, K.; Imaizumi, F.; Hatanaka, M.; Takimoto, M.; Mizumura, M.; Gotoh, J.; Ikenoue, H.; Sugawa, S. LTPS Thin-Film Transistors Fabricated Using New Selective Laser Annealing System. IEEE Transactions on Electron Devices 2018, 65, 3250–3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, F.; Sun, H.-Z.; Lee, J.-Y.; Pyo, S.; Kim, S.-J. Improved High-Performance Solution Processed In₂O₃ Thin Film Transistor Fabricated by Femtosecond Laser Pre-Annealing Process. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 44453–44462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-Y.; Shan, F.; Kim, H.-S.; Kim, S.-J. Effect of Femtosecond Laser Postannealing on a-IGZO Thin-Film Transistors. IEEE Transactions on Electron Devices 2021, 68, 3371–3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, F.; Lee, J.-Y.; Zhao, H.-L.; Choi, S.G.; Koh, J.-H.; Kim, S.-J. Multi-stacking Indium Zinc Oxide Thin-Film Transistors Post-annealed by Femtosecond Laser. Electronic Materials Letters 2021, 17, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, M. H.; Cho, E. S.; Kwon, S. J. Characteristics of the ITO resistive touch panel deposited on the PET substrate using in-line DC magnetron sputtering. Vacuum 2014, 101, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Kwon, S. J.; Jeon, Y.; Cho, E.-S. Rapid Photonic Curing Effects of Xe-Flash Lanp on ITO-Ag-ITO Miultilayer Electrodes : Toward High-throughput Flexible and Transparent Electronics. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakata, M.; Takechi, K.; Azuma, K.; Tokumitsu, E.; Yamaguchi, H.; Kaneko, S. Improvement of InGaZnO4 Thin Film Transistors Characteristics Utilizing Excimer Laser Annealig. Appl. Phys. Exp 2009, 021102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermundo, J. P.; Ishikawa, Y.; Fujii, M. N.; Nonaka, T.; Ishihara, R.; Ikenoue, H.; Uraoka, Y. Effect of eximer laser annealing o a-InGaZnO thin film transistors passivated by solution-processed hybrid passivation layers. J. Phys. D : Appl. Phys 2016, 49, 035102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.-Y.; Zhu. B.; Ast, D. G.; Greene, R. G.; Thompson, M. O. High mobility amorphous InGaZnO4 thin film transistors formed by CO2 laser spiking annelaing. Appl Phys Lett 2015, 106, 123506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, A. U.; Yeh, T. C.; Buchholz, D. B.; Chang, R. P. H.; Mason, T. O. Quasi-reversible point defect relaxation in amorphous In-Ga-Zn-O thin films by in situ electrical measurements. Appl Phys Lett 2013, 102, 122103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. W.; Kim, A. Absolute work function measurement by using photoelectron spectroscopy. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2021, 31, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Laser beam power | VTH [V] | S.S [V/dec] | mn [cm2/V·s] | Ion/Ioff |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22 | 4.06ㄸ+ | |||

| 0.84 | ||||

| Pristine | 2.48 2.76 |

2.00 | 0.84 | 4.06E+7 |

| 54 mW 60 |

2.76 | 1.77 | 1.20 | 6.79E+7 1 |

| 60 mW | 1.19 | 1.81 | 0.77 | 1.88E+7 |

| 77 mW | -0.77 | 1.81 | 0.35 | 2.41E+8 |

| 90 mW | -1.10 | 1.61 | 0.30 | 4.84E+8 |

| 119 mW | -1.39 | 1.86 | 1.13 | 2.91E+7 |

| 155 mW | -1.88 | 2.28 | 0.32 | 5.42E+7 |

| 202 mW | -4.47 | 2.64 | 0.03 | 4.62E+6 |

| 227 mW | - | - | - | 3.45E+0 |

| 253 mW | - | - | - | 4.27E+0 |

| 280 mW | - | - | - | 1.36E+1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).