Submitted:

07 December 2024

Posted:

09 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

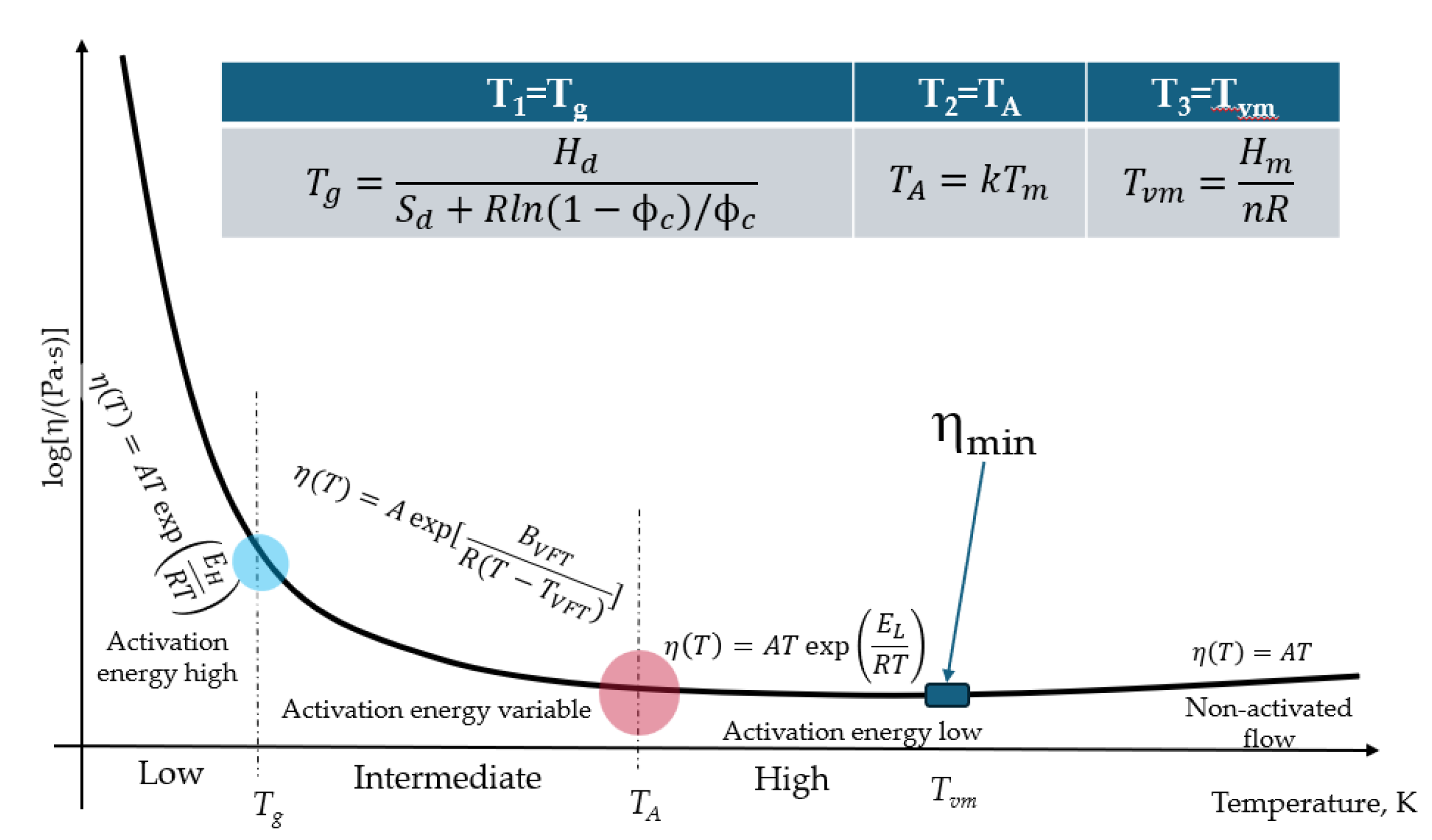

1. Introduction

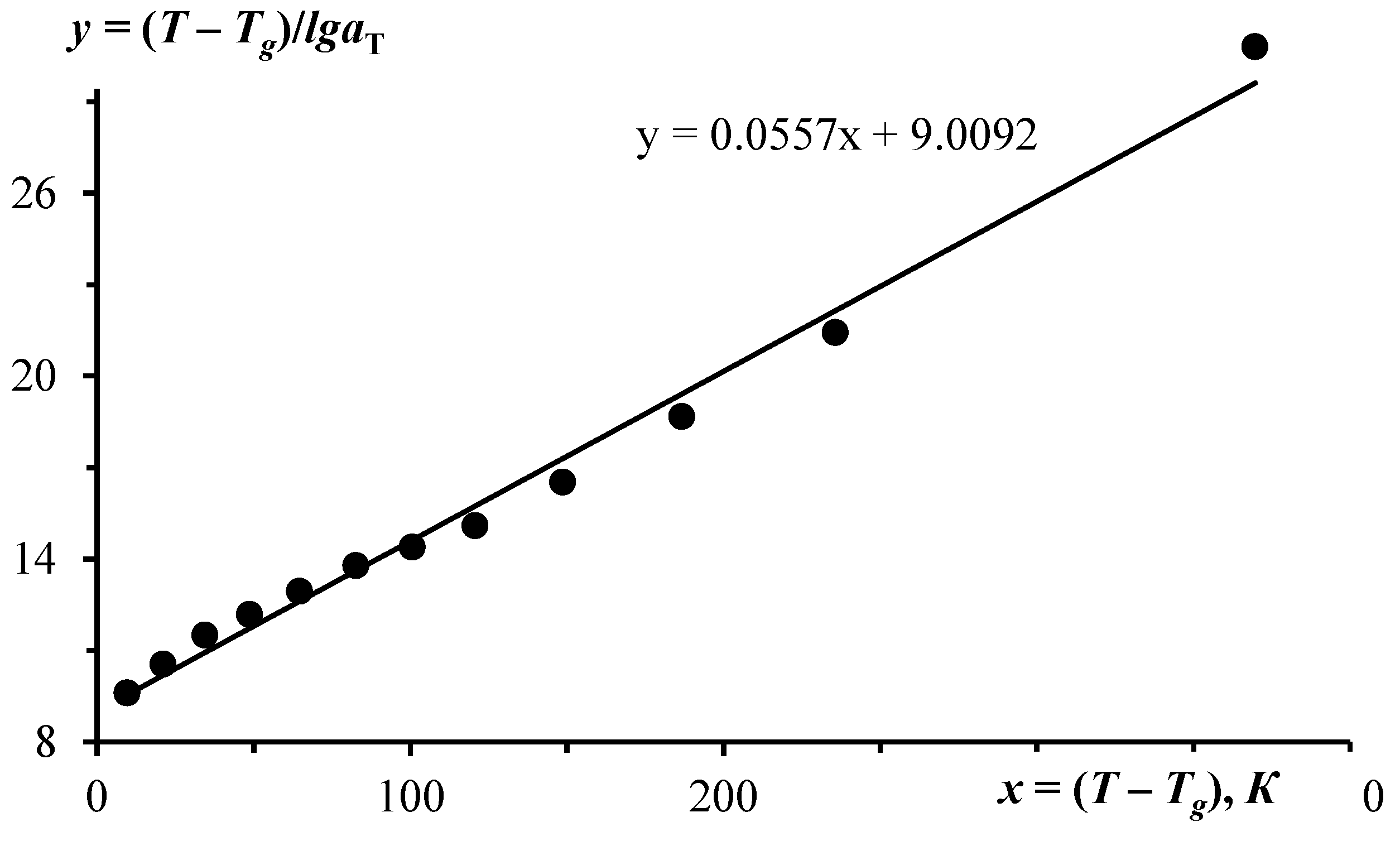

2. Methodology Based on WLF Equation

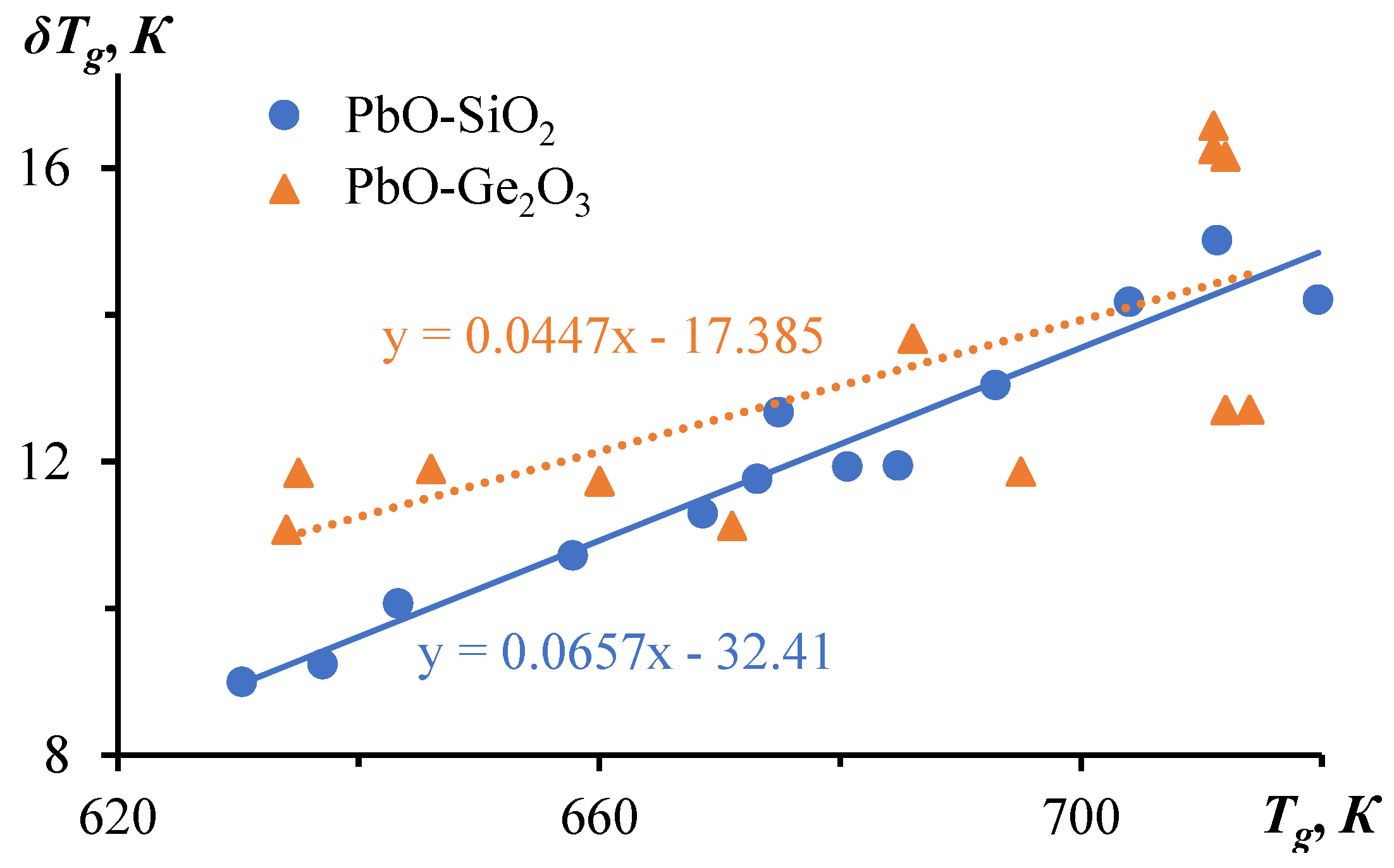

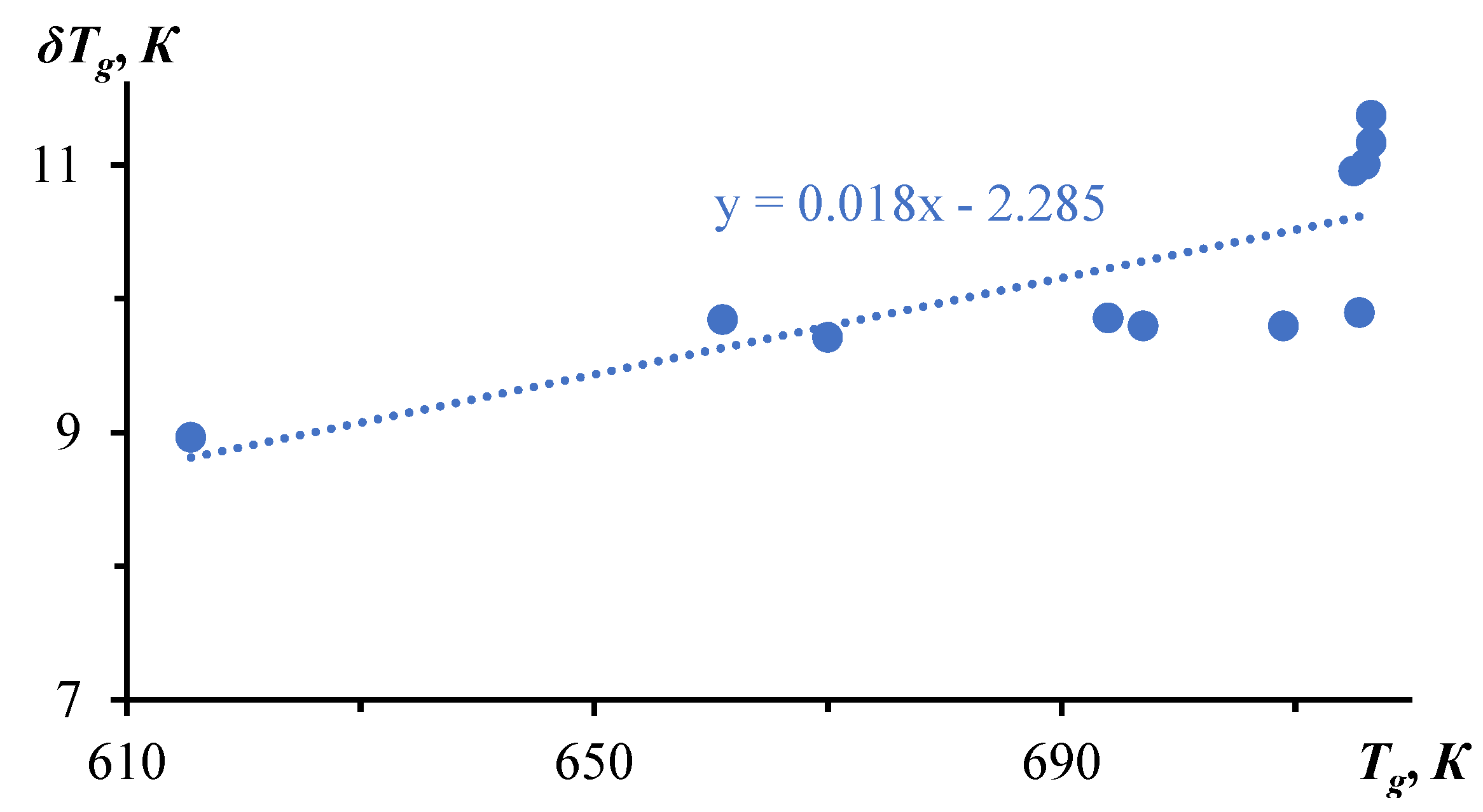

3. Relaxation Character of Glass Transition

4. Generalization of Schmelzer Vitrification Criterion

5. Structural Relaxation Time

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mazurin, O.V.; Gankin, Yu.V. Glass transition temperature: problems of measurement procedures. Glass Technology, 2008, 49, 229-233.

- Zheng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Montazerian, M.; Gulbiten, O.; Mauro, J.C.; Zanotto, E.D.; Yue, Y. Understanding glass through differential scanning calorimetry. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 7848–7939.

- Encyclopedia of Glass Science, Technology, History, and Culture. Richet, P., Conradt, R., Takada, A., Dyon, J. Eds., Wiley, Hoboken, NJ, 2021. 1568 p., e.g. [CrossRef]

- Ojovan, M.I.; Lee, W.E. Topologically disordered systems at the glass transition. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2006, 18, 11507–11520.

- Ojovan, M.I., Tournier R.F. On structural rearrangements near the glass transition temperature in amorphous silica. Materials 2021, 14, 5235, 19 pp.

- Kantor, Y.; Webman, I. Elastic properties of random percolating systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1984, 52, 1891–1894.

- Ojovan, M.I.; Louzguine-Luzgin, D.V. Revealing Structural Changes at Glass Transition via Radial Distribution Functions. J. Phys. Chem. B, 2020, 124 , 3186-3194 . [CrossRef]

- Glova, A.; Karttunen M. Learning glass transition temperatures via dimensionality reduction with data from computer simulations: Polymers as the pilot case. J. Chem. Phys. 2024, 161, 184902 . [CrossRef]

- Sanditov, D.S.; Ojovan, M.I. ; Darmaev, M.V. Glass transition criterion and plastic deformation of glass. Physica B, 2020, 411914. [CrossRef]

- Douglas, R.W. The flow of glass. J. Soc. Glass Tech. 1949, 33, 138–162.

- Doremus, R.H. Viscosity of silica. J. Appl. Phys. 2002, 92, 7619.

- Ojovan, M. Viscous flow and the viscosity of melts and glasses. Phys. Chem. Glas. 2012, 53, 143–150.

- Zheng, Q.; Mauro, J.C. Viscosity of glass-forming systems. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2017, 100, 1551–2916.

- Hrma, P.; Ferkl, P.; Kruger, A.A. Arrhenian to non-Arrhenian crossover in glass melt viscosity. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2023, 619, 122556. [CrossRef]

- Ojovan, M.I.; Louzguine-Luzgin, D.V. On Crossover Temperatures of Viscous Flow Related to Structural Rearrangements in Liquids. Materials 2024, 17, 1261. [CrossRef]

- Zarzycki, J. Glasses and the Vitreous State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1982.

- Sanditov, D.S.; Bartenev, G.M. Physical Properties of Disordered Structures, Nauka: Novosibirsk, Russia, 1982.

- Angel, C.A. Perspective on the glass transition. J. Phys. Chem. Solids, 1988, 49, 863-871.

- Volf, M.B. Mathematical approach to glass; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 1988.

- Angel, C.A.; Ngai, K.L.; McKenna, G.B.; McMillan, P.F.; Martin, S.W. Relaxation in glass forming liquids and amorphous solids. J. Appl. Phys. 2000, 88, 3113-3157.

- Varshneya, A.K. (2006). Fundamentals of Inorganic Glasses. Sheffield: Society of Glass Technology, 2006.

- Sanditov, D.S.; Ojovan, M.I. Relaxation aspects of the liquid—glass transition. Physics Uspekhi 2019, 62 111 - 130. [CrossRef]

- Mazurin, O.V. Problems of compatibility of the values of glass transition temperatures published in the world literature. Glass Phys Chem 2007, 33, 22–36. [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.L.; Landel, R.F.; Ferry, J.D. The Temperature Dependence of Relaxation Mechanisms in Amorphous Polymers and Other Glass-forming Liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1955, 77, 3701–3707.

- Ferry, J.D. Viscoelastic Properties of Polymers; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1970.

- Sanditov, D.S. Model of delocalized atoms in the physics of the vitreous state. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 2012, 115 112–124.

- Sanditov, D.S.; Razumovskaya, I.V. New Approach to Justification of the Williams–Landel–Ferry Equation. Polym. Sci. Ser. A, 2018, 60, 156–161.

- Nemilov, S.V.; Petrovskii, G.T. A Study of the Viscosity of Glasses in the As–Se System. Zh. Prikl. Khim. 1963, 36, 977–981.

- Sanditov, D.S.; Mashanov, A.A.; Razumovskaya, I.V. On the temperature dependence of the glass transition activation energy. Polym. Sci. Ser. A 2020, 62, 588–596.

- Sanditov, D. S.; Mashanov, A. A. Some General Aspects of the Liquid–Glass Transition in Sodium Germanate Glasses. Inorganic Materials, 2022, 58, 630. [CrossRef]

- Darmaev, M.V.; Ojovan, M.I.; Mashanov, A.A.; Chimytov, T.A. The Temperature Interval of the Liquid–Glass Transition of Amorphous Polymers and Low Molecular Weight Amorphous Substances. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2742. [CrossRef]

- Mashanov A.A., Ojovan M.I., Darmaev M.V., Razumovskaya I.V. The Activation Energy Temperature Dependence for Viscous Flow of Chalcogenides. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4319. [CrossRef]

- Sanditov, D.S.; Darmaev, M.V.; Sanditov, B.D. Application of the model of delocalized atoms to metallic glasses. Tech. Phys. 2017, 62, 53–57.

- Nemilov S.V., Ignatiev A.I. Viscosity of melts of the PbO–SiO2 system in the region of softened and liquid states. Glass Phys. Chem. (RUS), 1990, 16, 85-93.

- Nemilov, S.V., Viscosity and Structure of Binary Germanate Glasses in the Range of Softening Temperatures, Zh. Prikl. Khim. (Leningrad), 1970, 43, 2602-2610.

- Nemilov, S.V., Burunova, O.N., and Gilev, I.S., Viscosity and Elasticity of Glasses in the Bi2O3–B2O3 System, Zh. Prikl. Khim. (Leningrad), 1972, 45, 1193–1198.

- Volkova, N.E. and Nemilov, S.V., The Influence of Heat Treatment on the Low-Temperature Viscosity of Glasses in the Li2O–B2O3 System, Fiz. Khim. Stekla, 1990, 16, 207–212.

- Romanova, N.V. and Nemilov, S.V., A Study of the Viscosity of Glasses in the BaO–B2O3, BaO–B2O3–La2O3, and CdO–B2O3–La2O3 Systems in the Softening Range, Izv. Akad. Nauk SSSR, Neorg. Mater., 1970, 6,1322–1326.

- Nemilov, S.V., Structural Investigation of Glasses in the B2O3–Na2O System by Viscometry, Izv. Akad. Nauk SSSR, Neorg. Mater., 1966, 2, 349–356.

- Ojovan, M.I. Configurons: thermodynamic parameters and symmetry changes at glass transition. Entropy 2008, 10, 334-364.

- Trachenko, K.; Brazhkin, V.V. Minimal quantum viscosity from fundamental physical constants. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaba3747.

- Ojovan, M.I.; Louzguine-Luzgin, D.V. The Minima of Viscosities. Materials 2024, 17, 1822. [CrossRef]

- Sanditov, D.S. On the nature of the liquid-to-glass transition equation. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 2016, 123, 429–442. [CrossRef]

- Sanditov D.S., Mashanov A.A. Some regularities of the transition of sodium germanate glasses from the liquid to the glassy state. Inorganic materials. 2022, 58, 630-636. [CrossRef]

- Bartenev, G.M. On the relation between the glass transition temperature of silicate glass and rate of coolingor heating. Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR 1951, 76, 227–230. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322890519_Glass_Transition_Crystallization_of_Glass-Forming_Melts_and_Entropy [accessed Nov 13 2024].

- Schmelzer, J.W.P.; Tropin, T.V. Glass Transition, Crystallization of Glass-Forming Melts, and Entropy. Entropy 2018, 20, 103. [CrossRef]

- Volkenshtein M. V., Ptitsyn O. B. Relaxation theory of glass transition. J. Tech. Physics. 1956, 10, 2204–2222.

- Nemilov, S.V. Maxwell equation and classical theories of glass transition as a basis for direct calculation of viscosity at glass transition temperture. Glass Phys Chem 2013, 39, 609–623. [CrossRef]

- Sanditov, D.S., Mantatov, V.V., Sangadiev, S.S. Generalized Kinetic Criterion of the Liquid–Glass Transition. Phys. Solid State 2020, 62, 1924–1927. [CrossRef]

- Benigni, P. CALPHAD modeling of the glass transition for a pure substance, coupling thermodynamics and relaxation kinetics. Calphad 2021, 72, 102238.

- Schmelzer J.W.P. Kinetic Criteria of Glass Formation and the Pressure Dependence of the Glass Transition Temperature. J. Chem. Phys. 2012, 36, 074512. [CrossRef]

- Tropin T.V., Shmeltzer Yu.V.P., Aksenov V.L. Modern aspects of the kinetic theory of glass transition. Physics-Uspekhi 2016, 186, 47-73. [CrossRef]

- Mauro, J.C.; Yue, Y.; Ellison, A.J.; Gupta, P.K.; Allan, D.C. Viscosity of glass-forming liquids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 19780–19784.

- Bartenev, G.M., Luk’yanov, I.A., Dependence of the Glass Transition Temperature on the Heating Rate for Amorphous Materials and the Relation of the Glass Transition Temperature to the Activation Energy, Zh. Fiz. Khim., 1955, 29, 1486–1498.

| № | Glass | С1 | С2, К | Tg, К | δTg, К | fg | Cg ∙ 103 | τg, s | |

| mol.% | |||||||||

| PbO | SiO2 | ||||||||

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 |

40.27 42.07 44.64 47.25 48.73 49.54 50.24 51.19 52.25 55.02 57.53 60.16 62.29 |

59.73 57.93 55.36 52.75 51.27 50.46 49.76 48.81 47.75 44.98 42.47 39.84 37.71 |

34.3 35.7 36.8 36.6 36.5 36.5 37.8 37.2 37.2 38.5 38.4 39.1 41.2 |

211.8 233.3 226.6 207.7 189.3 189.2 208.0 190.4 182.8 179.3 168.1 157.0 161.2 |

720 711 704 693 685 681 675 673 669 658 643 637 630 |

14.2 15.0 14.2 13.0 11.9 11.9 12.7 11.8 11.3 10.7 10.1 9.2 9.0 |

0.029 0.028 0.027 0.027 0.027 0.027 0.026 0.027 0.027 0.026 0.026 0.026 0.024 |

8.3 7.8 7.5 7.6 7.6 7.6 7.3 7.4 7.4 7.1 7.1 7.0 6.5 |

284.1 300.3 283.5 260.8 238.8 238.6 253.4 235.3 225.8 214.4 201.2 184.7 179.9 |

| PbO | GeO2 | ||||||||

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 |

15 18 20 25 27 33 35 40 42 45 48 50 |

85 82 80 75 73 67 65 60 58 55 52 50 |

32.2 38.2 34.6 33.0 35.9 34.9 54.9 28.9 41.2 46.1 56.6 73.7 |

520.8 633.2 561.9 418.8 455.9 413.6 751.0 321.9 483.0 549.0 627.0 873.6 |

712 711 711 714 712 695 686 671 660 646 634 635 |

16.2 16.6 16.3 12.7 12.7 11.9 13.7 11.1 11.7 11.9 11.1 11.8 |

0.013 0.011 0.013 0.013 0.012 0.012 0.008 0.015 0.011 0.009 0.008 0.006 |

3.1 2.5 2.9 3.0 2.7 2.8 1.6 3.6 2.3 2.0 1.6 1.1 |

323.2 331.5 325.2 254.1 254.0 237.2 273.5 222.5 234.6 238.0 221.4 237.0 |

| № | Glass | С1 | С2, К | Tg, К | δTg, К | fg | Cg ∙ 103 | τg, s | |

| mol.% | |||||||||

| B2O3 | Bi2O3 | ||||||||

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 |

79 78.2 77.21 76.95 72 69 64.03 62.2 57.98 56.91 43.19 |

21 21.8 22.79 23.05 28 31 35.97 37.8 42.02 43.09 56.81 |

46.4 33.9 44.2 64.9 40.1 63.4 63.4 99.7 27.5 59.0 85.4 |

517.9 385.7 437.4 713.8 439.2 620.6 620.6 982.5 266.6 580.9 765.5 |

717 717 716 716 715 709 697 694 670 661 616 |

11.2 11.4 9.9 11.0 11.0 9.8 9.8 9.9 9.7 9.8 9.0 |

0.009 0.013 0.010 0.007 0.011 0.007 0.007 0.004 0.016 0.007 0.005 |

2.0 2.9 2.1 1.3 2.4 1.4 1.4 0.8 3.8 1.5 1.0 |

223.3 227.4 197.9 220.1 219.0 195.9 195.9 197.1 194.2 196.9 179.3 |

| B2O3 | Li2O | ||||||||

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 |

98 94.9 93 89.6 87.8 84.8 |

2 5.1 7 10.4 12.2 15.2 |

25.3 27.6 29.4 31.7 29.8 38.2 |

400.5 433.0 492.3 544.6 520.0 601.6 |

286 323 332 364 386 414 |

15.9 15.7 16.7 17.2 17.4 15.8 |

0.017 0.016 0.015 0.014 0.015 0.011 |

4.2 3.8 3.5 3.2 3.4 2.5 |

317.2 313.6 334.5 343.2 348.7 315.0 |

| B2O3 | BaO | ||||||||

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

98.44 98.13 95.52 91.55 90.44 87 85.8 |

1.56 1.87 4.48 8.45 9.56 13 14.2 |

25.5 15.3 17.3 21.6 20.2 45.9 24.6 |

394.3 231.2 259.9 355.4 317.4 855.2 403.6 |

524 530 659 720 732 735 739 |

15.5 15.1 15.0 16.5 15.7 18.6 16.4 |

0.017 0.028 0.025 0.020 0.022 0.009 0.018 |

4.2 8.0 6.8 5.2 5.6 2.0 4.4 |

309.1 302.8 300.2 329.7 314.9 372.7 327.5 |

| B2O3 | Na2O | ||||||||

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 |

94.6 92 89.3 86.5 84.7 78.7 76.8 75.7 75.4 72.6 67.4 61.5 |

5.4 8 10.7 13.5 15.3 21.3 23.2 24.3 24.6 27.4 32.6 38.5 |

21.9 23.1 23.1 19.9 29.2 28.3 21.0 20.8 21.6 22.6 20.4 23.4 |

367.4 377.1 377.1 307.7 457.0 375.7 255.4 253.5 253.6 261.1 215.8 241.5 |

293 319 343 373 391 455 460 460 463 466 467 461 |

16.8 16.3 16.3 15.4 15.7 13.3 12.2 12.2 11.8 11.5 10.6 10.3 |

0.020 0.019 0.019 0.022 0.015 0.015 0.021 0.021 0.020 0.019 0.021 0.019 |

5.1 4.7 4.7 5.7 3.5 3.7 5.3 5.4 5.2 4.9 5.5 4.7 |

336.2 325.9 325.9 308.9 313.2 265.3 243.4 243.3 235.0 230.5 211.5 206.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).