Submitted:

08 December 2024

Posted:

09 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and discussion

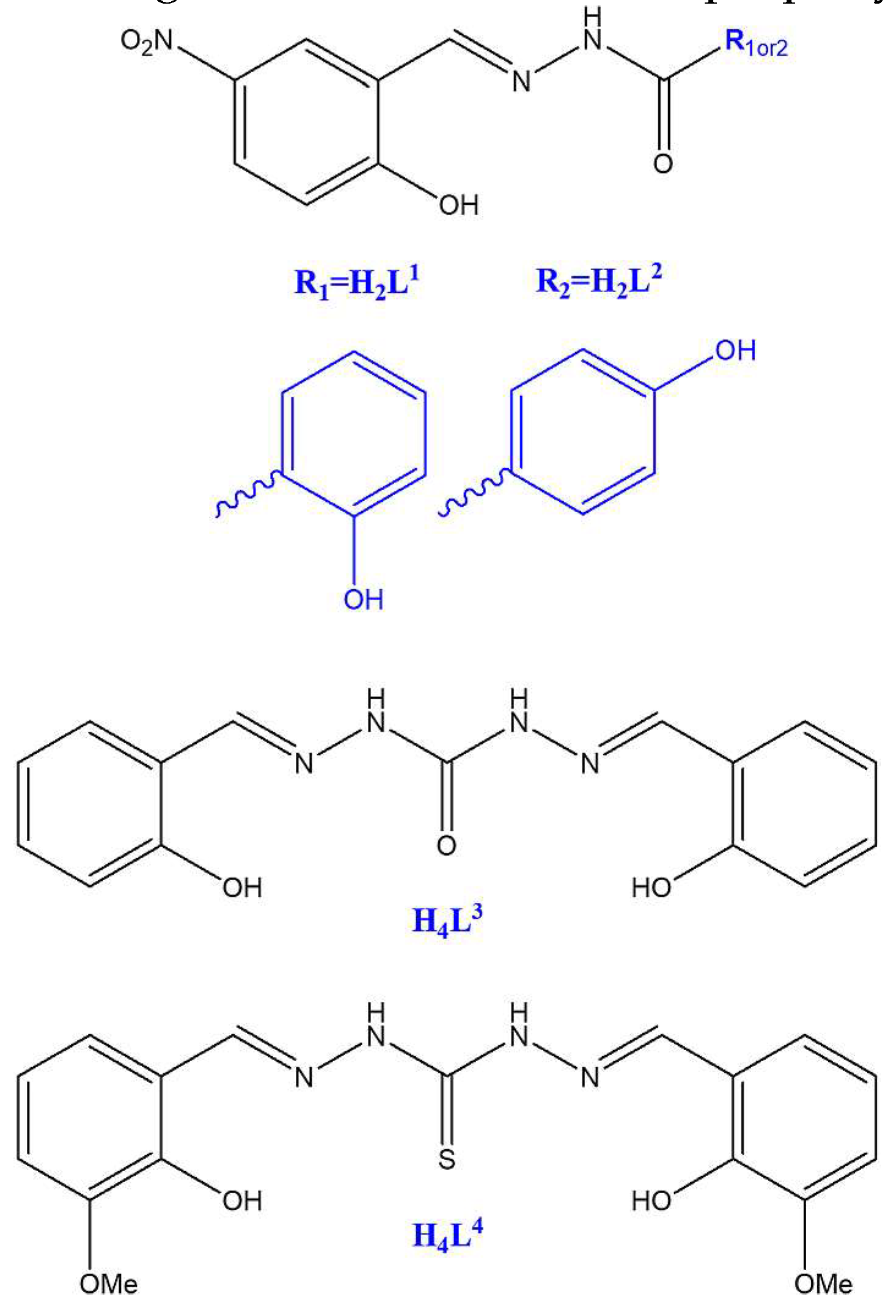

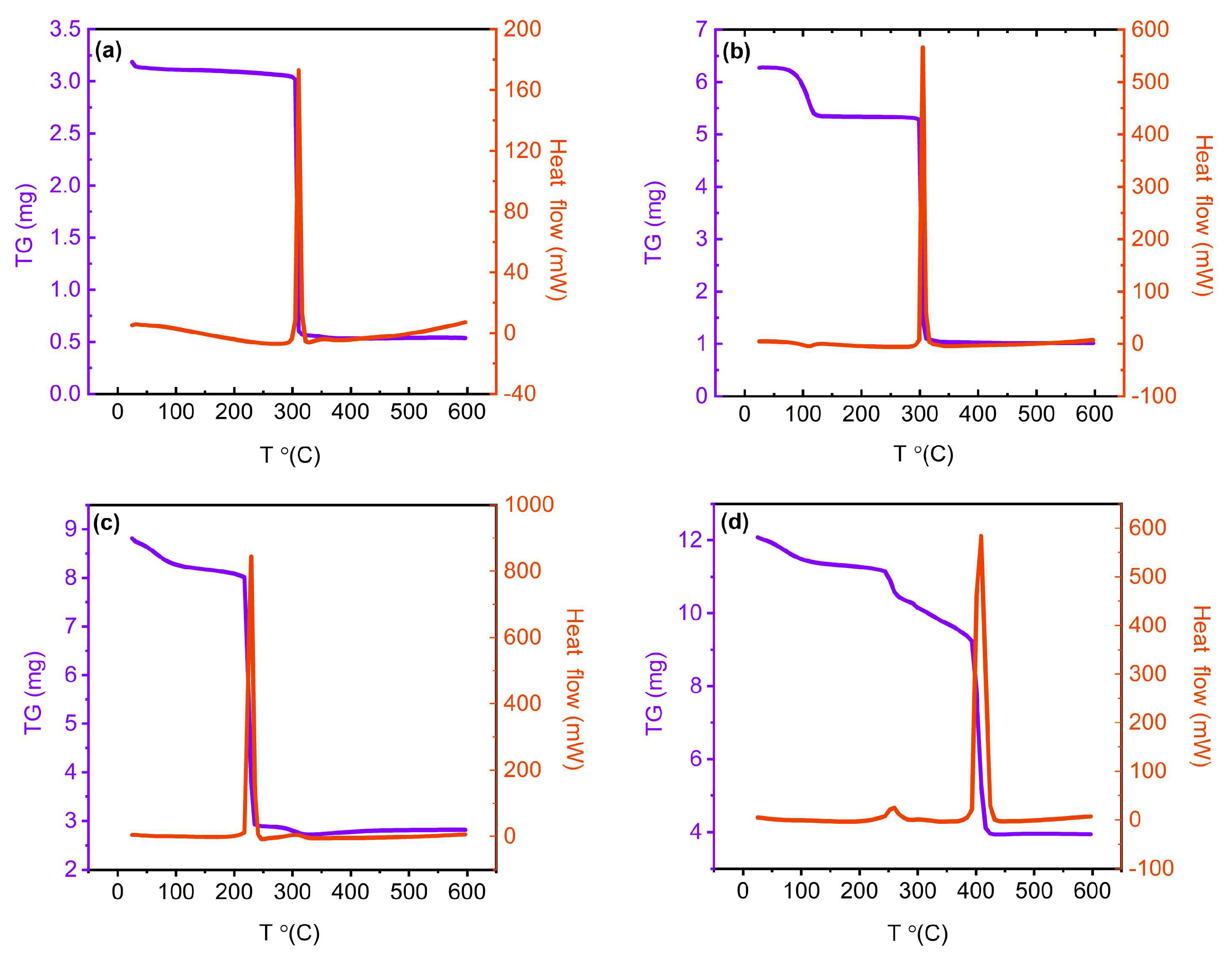

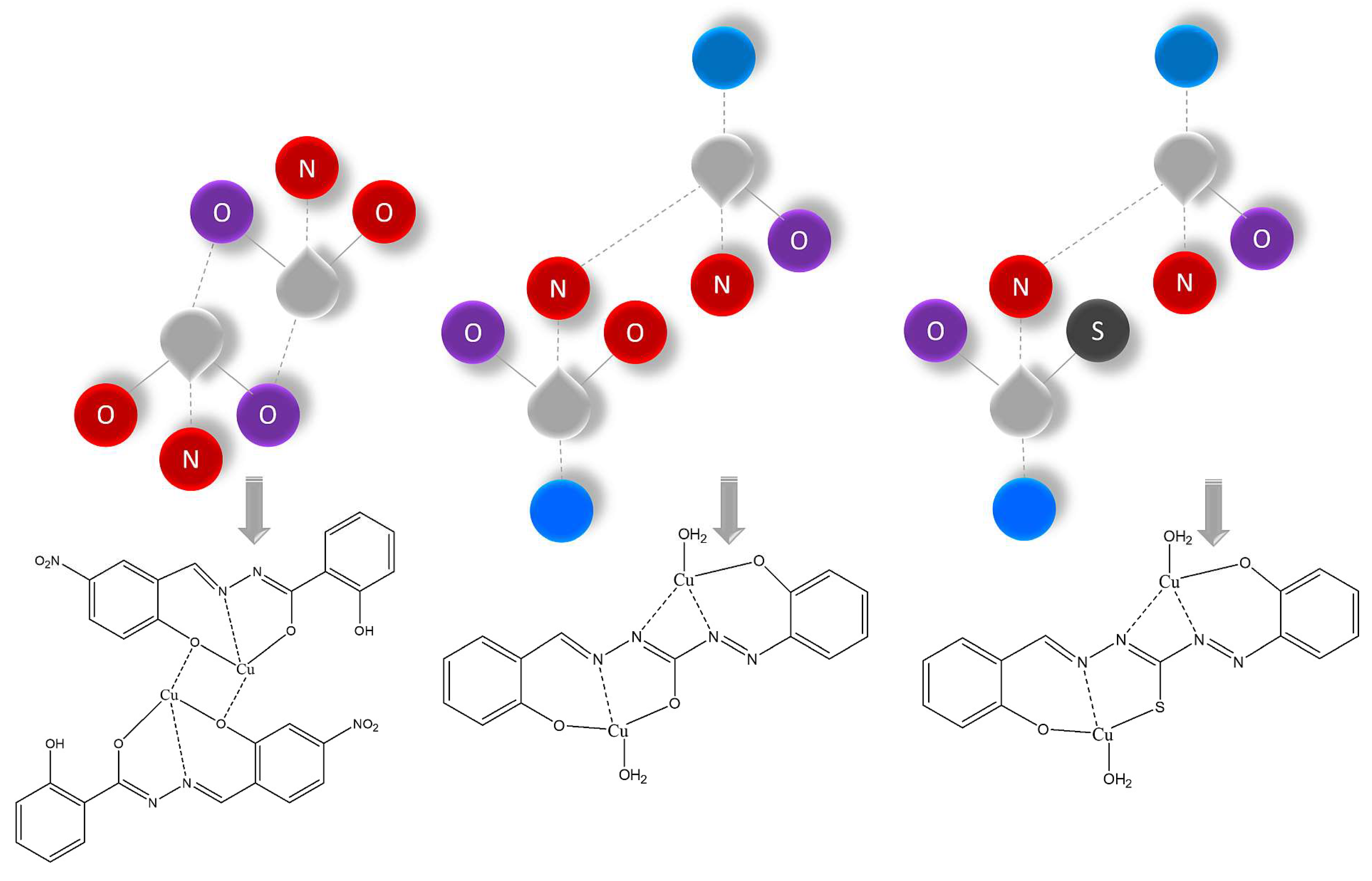

2.1. Preparation, spectroscopic and thermal characterization

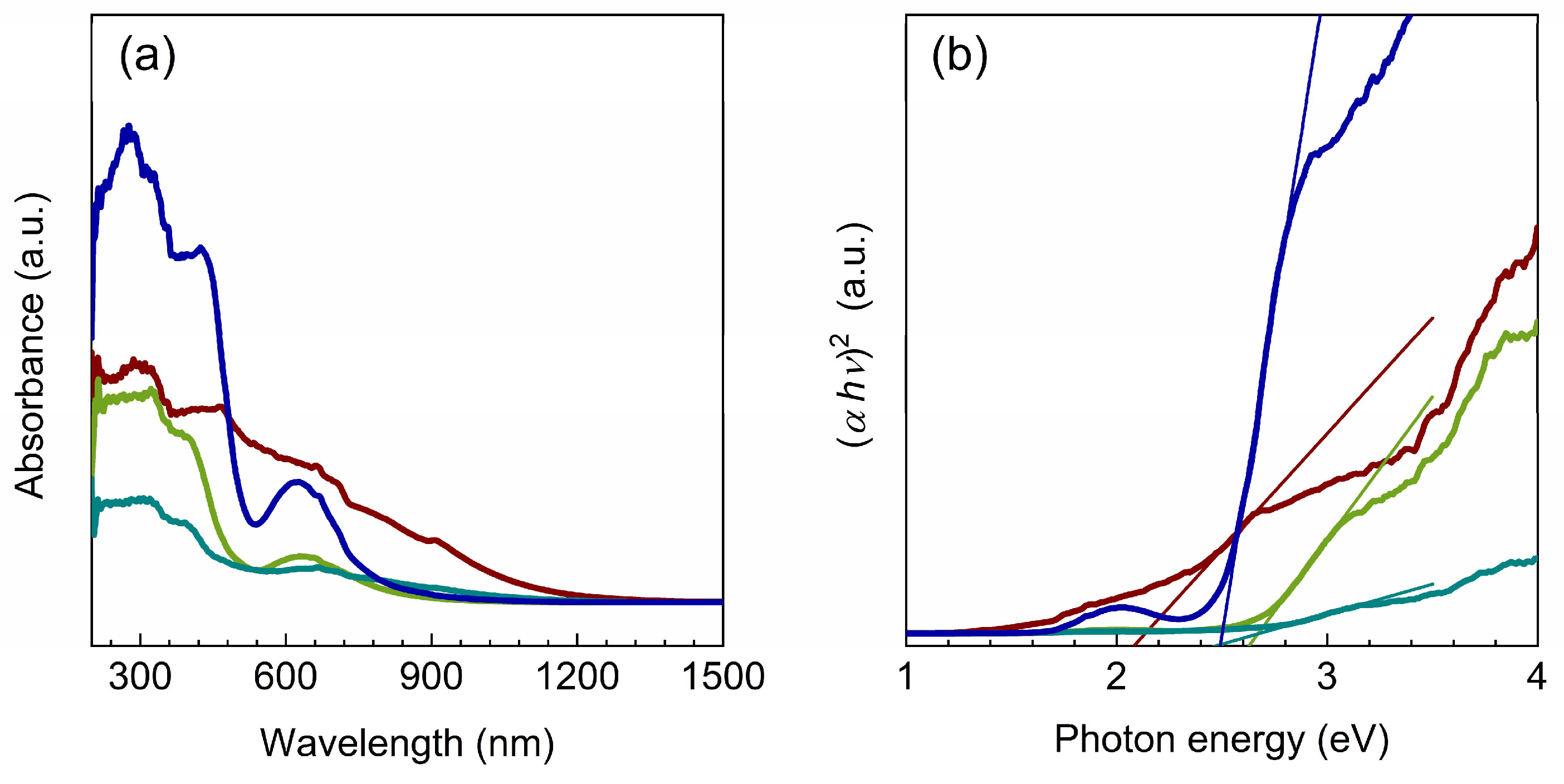

2.2. Optical properties

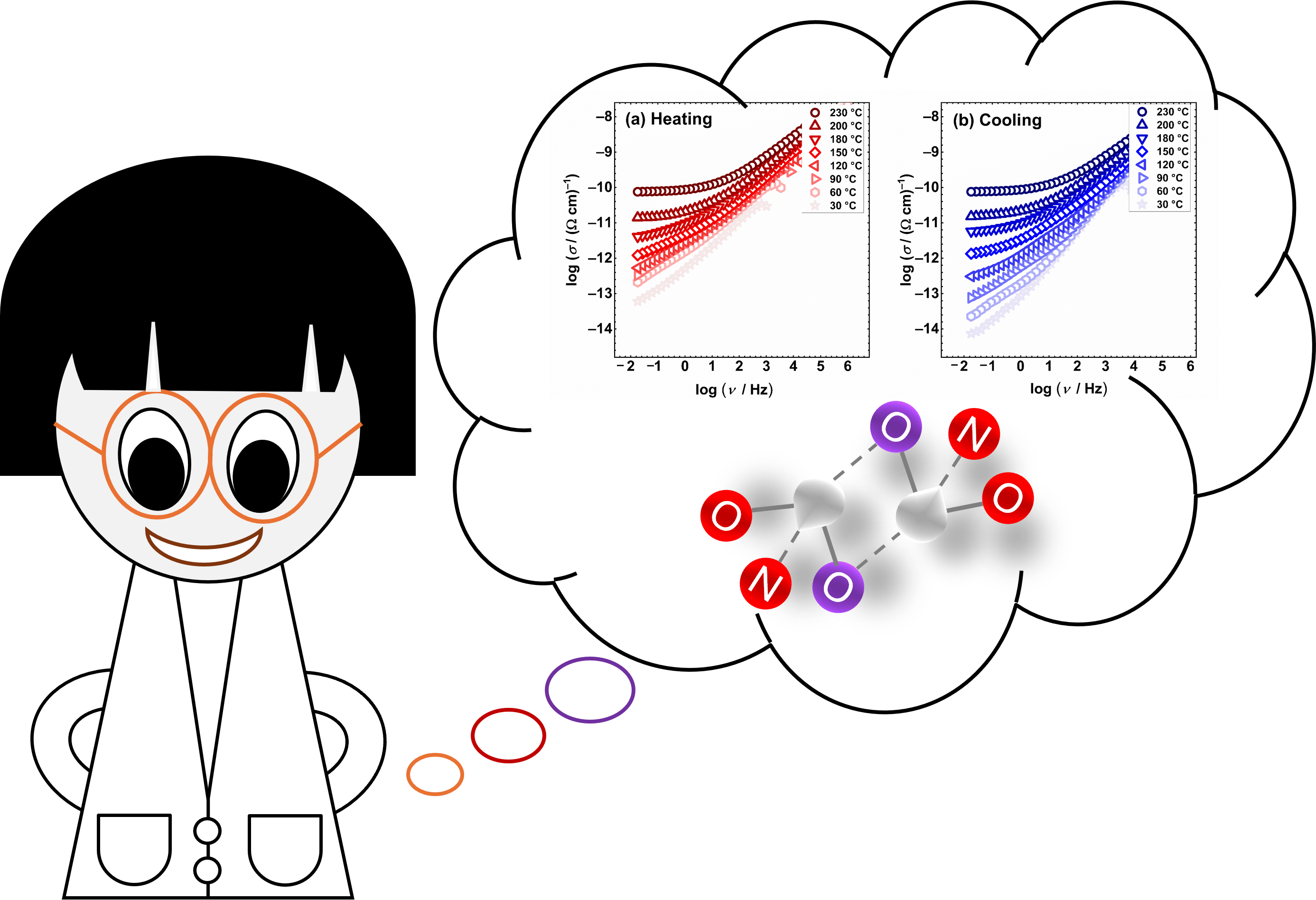

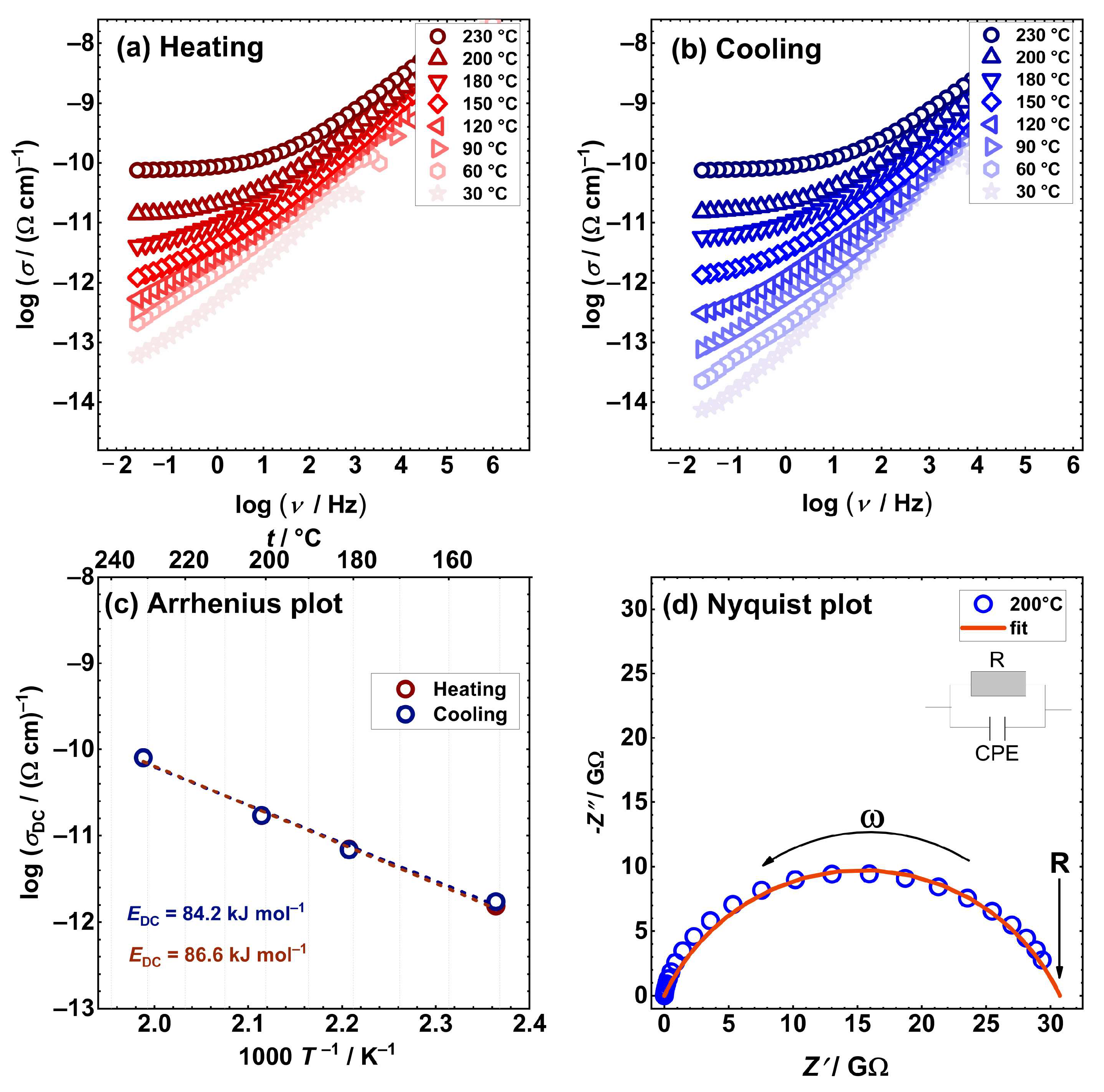

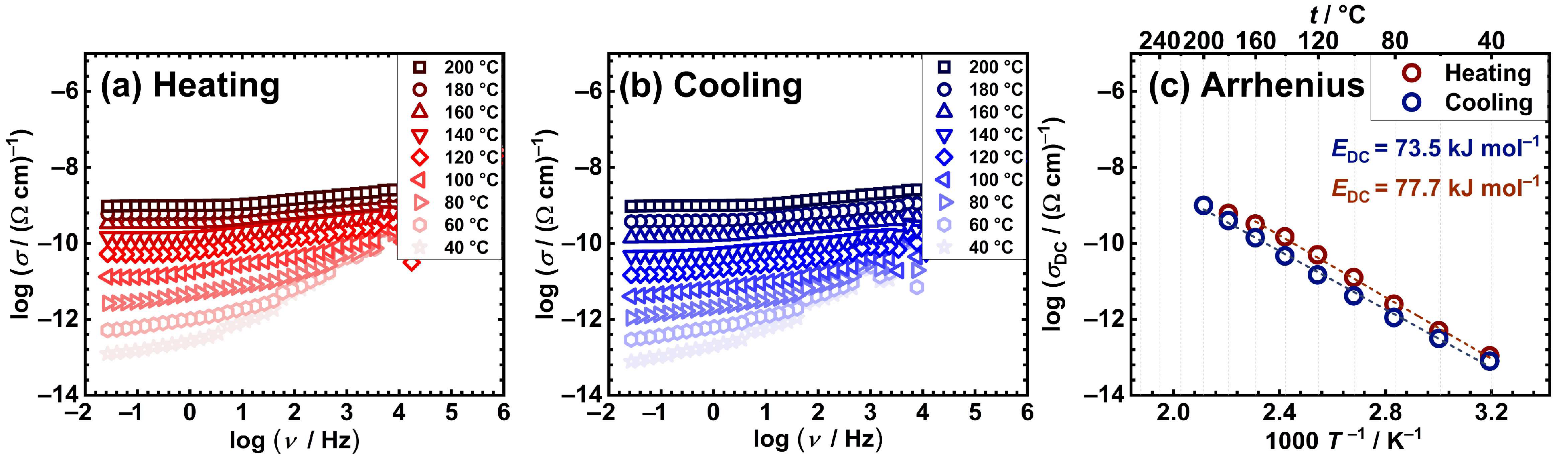

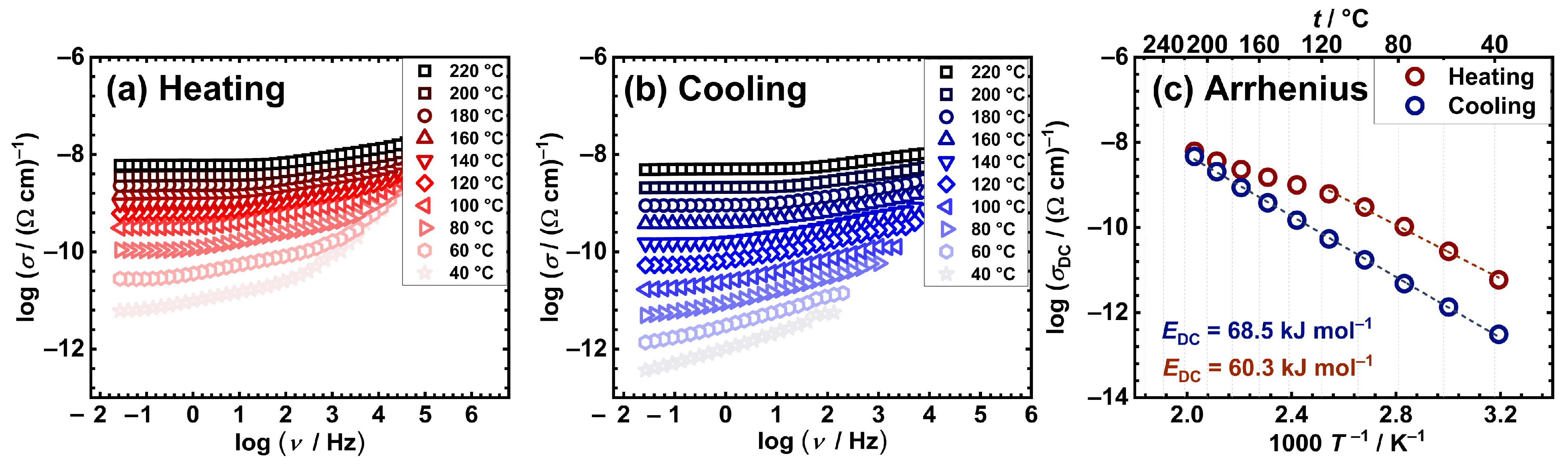

2.3. Electrical properties

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Preparation

3.1.1. Preparation of the complexes

3.2. Impedance Spectroscopy Measurements

3.3. Physical Methods

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Di Bernardo, P.; Zanonato, P.; Tamburini, S.; Tomasin, P.; Vigato, P. Complexation behaviour and stability of Schiff bases in aqueous solution. The case of an acyclic diimino (amino) diphenol and its reduced triamine derivative. Dalton Trans. 2006, 39, 4711–4721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusuf, T.L.; Oladipo, S.D.; Olagboye, S.A.; Zamisa, S.J.; Tolufashe, G.F. Solvent-free synthesis of nitrobenzyl Schiff bases: Characterization, antibacterial studies, density functional theory and molecular docking studies. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1222, 128857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, C.M.; da Silva, D.L.; Modolo, L.V.; Alves, R.B.; de Resende, M.A.; Martins, C.V.B.; de Fátima, Â. Schiff bases: A short review of their antimicrobial activities. J. Adv. Res. 2011, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesley Jeevadason, A.; Kalidasa Murugavel, K.; Neelakantan, M.A. Review on Schiff bases and their metal complexes as organic photovoltaic materials. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2014, 36, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeewoth, T.; Li Kam Wah, H.; Bhowon, M.G.; Ghoorohoo, D.; Babooram, K. Synthesis and anti-bacterial/catalytic prop-erties of Schiff bases and Schiff base metal complexes derived from 2, 3-diaminopyridine. Synth. React. Inorg. Met.-Org. Chem. 2000, 30, 1023–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temel, H.; Ziyadanoğullari, B.; Aydin, I.; Aydin, F. Synthesis, spectroscopic and thermodynamic studies of new transi-tion metal complexes with N,N′-bis(2-hydroxynaphthalin-1-carbaldehydene)-1,2-bis(m-aminophenoxy)ethane and their determination by spectrophotometric methods. J. Coord. Chem. 2005, 58, 1177–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champouret, Y.D.; Fawcett, J.; Nodes, W.J.; Singh, K.; Solan, G.A. Spacially confined M2 centers (M = Fe, Co, Ni, Zn) on a sterically bulky binucleating support: Synthesis, structures and ethylene oligomerization studies. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 45, 9890–9900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Manzur, C.; Novoa, N.; Celedón, S.; Carrillo, D.; Hamon, J.-R. Multidentate unsymmetrically-substituted Schiff bases and their metal complexes: Synthesis, functional materials properties, and applications to catalysis. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 357, 144–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, Y.; Sano, T.; Fujii, H.; Nishio, Y.; Takahashi, H.; Shibata, K. White-light-emitting material for organic electro-luminescent devices. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 1996, 35, L1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamoto, T.; Nishiwaki, M.; Tsunekawa, Y.; Nozaki, K.; Konno, T. Synthesis and characterization of luminescent zinc (II) and cadmium (II) complexes with N, S-chelating Schiff base ligands. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 47, 3095–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Zoubi, W.; Al-Hamdani, A.A.S.; Ahmed, S.D.; Ko, Y.G. Synthesis, characterization, and biological activity of Schiff bases metal complexes. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2018, 31, e3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iftikhar, B.; Javed, K.; Khan, M.S.U.; Akhter, Z.; Mirza, B.; McKee, V. Synthesis, characterization and biological assay of Salicylaldehyde Schiff base Cu(II) complexes and their precursors. J. Mol. Struct. 2018, 1155, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigamonti, L.; Reginato, F.; Ferrari, E.; Pigani, L.; Gigli, L.; Demitri, N.; Kopel, P.; Tesarova, B.; Heger, Z. From solid state to in vitro anticancer activity of copper(ii) compounds with electronically-modulated NNO Schiff base ligands. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 14626–14639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehbe, M.; Leung, A.W.; Abrams, M.J.; Orvig, C.; Bally, M.B. A Perspective–can copper complexes be developed as a novel class of therapeutics? Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 10758–10773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwudiwe, D.C. , Arfin, T., Strydom, C.A., Arfin, T., Strydom, C.A. Fe(II) and Fe(III) complexes of N-ethyl-N-phenyl dithiocarbamate: electrical conductivity studies and thermal properties, Electrochim. Acta 2014, 127, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.H. , Moustafa, M.G. Spectroscopic, morphology and electrical conductivity studies on Co(II), Ni(II), Cu(II) and Mn(II)-oxaloyldihydrazone complexes, J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2020, 24, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, E.M.M., Abdel-Rahman, L.H., Abu-Dief, A.M., Elshafaie, A., Hamdan, S.K., Ahmed, A.M. The electric and thermoelectric properties of Cu(II)-Schiff base nano-complexes. Phys. Scr. 2018, 93, 055801. [CrossRef]

- Sarjanović, J. , Stojić, M., Rubčić, M., Pavić, L., Pisk, J. Impedance Spectroscopy as a Powerful Tool for Researching Mo-lybdenum-Based Materials with Schiff Base Hydrazones. Materials 2023, 16, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisk, J.; Šušković, M.; Topić, E.; Agustin, D.; Judaš, N.; Pavić, L. Molybdenum Complexes Derived from 2-Hydroxy-5-nitrobenzaldehyde and Benzhydrazide as Potential Oxidation Catalysts and Semiconductors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarjanović, J. , Topić, E., Rubčić, M., Androš Dubraja, L., Pavić, L., Pisk, J. Evaluation of vanadium coordination com-pounds derived from simple acetic acid hydrazide as non-conventional semiconductors. J. Mater. Chem. C 2024, 12, 4013–4025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarjanović, J. , Cader, M., Topić, E., Razum, M., Agustin, D., Rubčić, M., Pavić, L., Pisk, J. Bifunctional molybdenum and vanadium materials: semiconductor properties for advanced electronics and catalytic efficiency in linalool oxidation. Mater. Adv. 2024, 5, 9391–9402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topić, E. , Pisk, J., Agustin, D., Jenderlin, M., Cvijanović, D., Vrdoljak, V., Rubčić, M. Discrete and polymeric ensembles based on dinuclear molybdenum(VI) building blocks with adaptive carbohydrazide ligands: from the design to catalytic epoxidation. New J. Chem. 2020, 44, 8085–8097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.-M. , Liu, S. Acta Cryst. 2006, E62, 3026–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubčić, M. , Galić, N., Halasz, I., Jednačak, T., Judaš, N., Plavec, J., Sket, P., Novak, P. Multiple solid forms of 1, 5-bis (salicylidene) carbohydrazide: Polymorph-modulated thermal reactivity. Cryst. Growth Des. 2014, 14, 2900–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanping, R. , Rongbin, D., Liufang, W., Jigui, W. Synthesis, In Vitro Profiling, and In Vivo Evaluation of Ben-zohomoadamantane-Based Ureas for Visceral Pain: A New Indication for Soluble Epoxide Hydrolase Inhibitors. Synth.Commun. 1999, 29, 613–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrdoljak, V. Pavlović, G., Maltar-Strmečki, N., Cindrić, M. Copper(ii) hydrazone complexes with different nuclearities and geometries: synthetic methods and ligand substituent effects. New J. Chem 2016, 40, 9263–9274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.-Y. , Wang, W., Chen, H., Zhang, S.-H., Li, Y. Five novel dinuclear copper (II) complexes: Crystal structures, properties, Hirshfeld surface analysis and vitro antitumor activity study. Inorg.Chim.Acta 2016, 453, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragancea, D. , Shova, S., Enyedy, É.A., Breza, M., Rapta, P., Carrella, L.M., Rentschler, E., Dobrov, A., Arion, V.B. Copper (II) complexes with 1, 5-bis (2-hydroxybenzaldehyde) carbohydrazone. Polyhedron 2014, 80, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragancea, D. , Addison, A.W., Zeller, M., Thompson, L.K., Hoole, D., Revenco, M.D., Hunter, A.D. Dinuclear Copper (II) Complexes with Bis-thiocarbohydrazone Ligands. Eur.J.Inorg.Chem. 2008, 16, 2530–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhrubajyoti, M.; Bouzid, G.; Arka, D.; Sourav, R.; Sahbi, A.; Suman, H.; Sudipta, D. Synthesis, characterization, crystal structure, and fabrication of photosensitive Schottky device of a binuclear Cu(II)-Salen complex: a DFT investigations. RSC Adv., 2024, 14, 14992–15007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, R.; Shaaban, I.A.; Ali, T.E.; Assirib, M.A.; Shenouda, S.S. Co(II), Ni(II), Cu(II) and Cd(II)-thiocarbonohydrazone complexes: spectroscopic, DFT, thermal, and electrical conductivity studies. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 3772–37743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashaly, M.M.; Ismail, T.M.; El-Maraghy, S.H.; Habib, H.A. Heteronuclear complexes of oxorhenium(V) with Fe(III), Co(II), Ni(II), Cu(II), Cd(II) and UO2(VI) and their biological activities. J. Coord. Chem. 2004, 57, 1099–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, D. , Rao, P.C., Aiyappa, H.B., Kurungot, S., Mandal, S., Ramanujam, K., Mandal, S. Multifunctional copper dimer: structure, band gap energy, catalysis, magnetism, oxygen reduction reaction and proton conductivity. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 37515–37521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, L.-Q.; Li, Y.-X.; Chen,L. -C.; Zhang, J.-Y.; Huang, J.-J. Synthesis, X-ray structure, spectroscopic, electrochemical properties and DFT calculation of a bridged dinuclear copper(II) complex. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2016, 444, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, J.R.; Johnson, W.B. Fundamentals of Impedance Spectroscopy. In Impedance Spectroscopy: Theory, Experi-ment, and Applications, 3rd ed.; Eds. Dr. Evgenij Barsoukov, Dr. J. Ross Macdonald, Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanos, N.; Pissis, P.; Macdonald, J.R. Impedance Spectroscopy of Dielectrics and Electronic Conductors. In Mater. Charact. 2012, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, J.R. Impedance Spectroscopy. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 1992, 20, 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojić, V.; Bohač, M.; Bafti, A.; Pavić, L.; Salamon, K.; Čižmar, T.; Gracin, D.; Juraić, K.; Leskovac, M.; Capan, I.; Gajović, A. Formamidinium Lead Iodide Perovskite Films with Polyvinylpyrrolidone Additive for Active Layer in Perovskite Solar Cells, Enhanced Stability and Electrical Conductivity. Materials 2021, 14, 4594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razum, M.; Pavić, L.; Pajić, D.; Pisk, J.; Mošner, P.; Koudelka, L.; Šantić, A. Structure–Polaronic Conductivity Relation-ship in Vanadate–Phosphate Glasses. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2024, 107, 5866–5880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavić, L.; Nikolić, J.; Graça, M.P.F.; Costa, B.F.O.; Valente, M.A.; Skoko, Ž.; Šantić, A.; Moguš-Milanković, A. Effect of Controlled Crystallization on Polaronic Transport in Phosphate-based Glass-ceramics. Int. J. Appl. Glass Sci. 2019, 11, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbarczyk, J.E.; Jozwiak, P.; Wasiucionek, M.; Nowinski, J.L. Nanocrystallization as a Method of Improvement of Electrical Properties and Thermal Stability of V2O5-Rich Glasses. J. Power Sources 2007, 173, 743–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murawski, L.; Chung, C.H.; Mackenzie, J.D. Electrical Properties of Semiconducting Oxide Glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Sol-ids 1979, 32, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzak, T.K.; Pawliszak, Ł.; Michalski, P.P.; Wasiucionek, M.; Garbarczyk, J.E. Highly Conductive 90V2O5·10P2O5 Nanocrystalline Cathode Materials for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Procedia Eng. 2014, 98, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Murugavel, S. Mechanism of Polaronic Conduction in Olivine Phosphates: An Influence of Crystallite Size. J. Phys. Chem. C 2022, 127, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miessler, G.L.; Fischer, P.J.; Tarr, D.A. Inorganic Chemistry. Pearson, 2014.

- Topić, E. , Pisk, J., Agustin, D., Jenderlin, M., Cvijanović, D., Vrdoljak, V., Rubčić, M. Discrete and polymeric ensembles based on dinuclear molybdenum(VI) building blocks with adaptive carbohydrazide ligands: from the design to catalytic epoxidation. New J. Chem. 2020, 44, 8085–8097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.-M. , Liu, S. Acta Cryst. 2006, E62, 3026–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubčić, M. , Galić, N., Halasz, I., Jednačak, T., Judaš, N., Plavec, J., Sket, P., Novak, P. Multiple solid forms of 1, 5-bis (salicylidene) carbohydrazide: Polymorph-modulated thermal reactivity. Cryst. Growth Des. 2014, 14, 2900–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanping, R. , Rongbin, D., Liufang, W., Jigui, W. Synthesis, In Vitro Profiling, and In Vivo Evaluation of Ben-zohomoadamantane-Based Ureas for Visceral Pain: A New Indication for Soluble Epoxide Hydrolase Inhibitors. Synth.Commun. 1999, 29, 613–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WinFIT software, version 3.2, Novocontrol Technologies GmbH & Co. KG, Hundsangen, Germany.

| Sample | aσDC / (Ω cm)–1 |

EDC / kJ mol‒1 (Heating run) |

EDC / kJ mol‒1 (Cooling run) |

|---|---|---|---|

| [Cu2(L1)2] | 7.6×10−11 | 86.6 | 84.2 |

| [Cu2(L2)2]∙3MeOH | 1.7×10−14 | 81.0 | 83.1 |

| [Cu2(L3)(H2O)2] | 6.1×10−10 | 77.7 | 73.5 |

| [Cu2(L4)(H2O)2] | 3.6×10−9 | 60.3 | 68.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).