1. Introduction

In contemporary China, urbanization not only represents a significant phenomenon but also a pervasive trend. The rapid expansion of urban areas has been well-documented, with an unprecedented increase in constructed environments within urban clusters notably highlighted in recent studies [

1]. This expansion often comes at the expense of historical and culturally significant architecture, creating a tangible disconnection between modern urban development and local historical traditions [

2]. The survival of these ancient structures is increasingly threatened by the relentless push of urbanization, compounded by the effects of climate. In particular, the humid and hot climate prevalent in regions like Hainan is known to accelerate the degradation of building materials [

3], placing these edifices at greater risk.

Amidst these challenges, the preservation of such architectural heritage necessitates innovative strategies. Research has shown that epiphytic plant communities, thriving on these ancient structures, can play a beneficial role. These plants have the potential to regulate the microenvironment through their physiological and biochemical processes, thus mitigating material degradation induced by harsh environmental conditions [

4]. Epiphytic plants primarily vascular plants, bryophytes, and lichens traditionally defined as organisms spending most of their lifecycle attached to hosts without parasitizing them, are reconsidered in this study. We propose a refined definition where epiphytes specifically refer to vascular plants colonizing the three-dimensional surfaces of ancient buildings.

This study further explores the dual perspectives on the factors influencing epiphytic growth: abiotic and biotic. The Schimper hypothesis posits that epiphytes flourish in moist, shady forest environments and adapt their habitats in response to light availability [

5,

6]. In contrast, the Tietze-Pittendrigh hypothesis argues that epiphytes are more prevalent in dry, nutrient-poor settings, which are more hospitable to these organisms [

6,

7]. The "Stress Gradient Hypothesis" (SGH) introduces a biotic perspective, suggesting that positive interactions between organisms are more likely in environments with high external stress and limited resources [

8,

9,

10].

Moreover, while epiphytes can enhance urban biodiversity and contribute to the aesthetic value of urban landscapes [

11], they may also pose risks to the structural integrity of heritage sites. Certain species, especially larger trees, can cause biological damage to buildings [

12], with a distinct difference observed between the impacts of annuals and perennials [

13]. The discourse on native versus non-native species further enriches our understanding, challenging the conventional view of non-natives solely as threats [

14].

Given this complex interplay of factors, our study on Hainan Island aims to dissect the distribution patterns, species composition, and underlying mechanisms influencing epiphytes on ancient structures. By analyzing data from 44 ancient sites on the island, this research will not only fill a significant gap in existing literature by providing a comprehensive overview of these interactions but also contribute to the development of informed conservation strategies that balance cultural heritage preservation with urban ecological needs. Through statistical analysis and regression modeling, we seek to illuminate the driving forces behind the richness and diversity of epiphytic plants in these historical contexts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

Hainan Island, China's second-largest island, is situated at the southernmost part of the country. Its geography is distinctly shaped like an elliptical pear, aligned along a northeast-southwest axis, and spans an area of approximately 33,900 square kilometers. Geographically, it is bounded by latitudes 18°10'N to 20°10'N and longitudes 108°37'E to 111°03'E, positioning it directly south of the Tropic of Cancer. The island's climate is predominantly tropical monsoon maritime, characterized by minimal seasonal variation, consistently high temperatures, and copious rainfall throughout the year. These climatic conditions are conducive to the proliferation of tropical vegetation and support a rich biodiversity, earning Hainan the accolades of a "genetic resource bank" and a "natural museum." Such environmental richness forms an excellent basis for the study of epiphytic plant biodiversity.

Culturally, Hainan Island is a mosaic of diverse heritages, reflecting influences from the indigenous Han, Li, and Miao ethnic groups, as well as from overseas Chinese communities and Western cultures. The island's cultural landscapes exhibit a complex, altitude-relative distribution, enriching its historical and cultural depth. Noteworthy cultural and historical sites include the Dongpo Academy, the ancient city of Yazhou, and modern landmarks such as Sanya Phoenix International Airport, Yangpu Port, numerous recreational resorts, and Hainan University. This diverse array of sites provides a rich tapestry of resources for research into ancient architecture and its interplay with local flora, particularly epiphytic plants.

2.2. Data Sources and Basis for Epiphytic Plant Species

In this research, the richness and abundance of epiphytic plant species colonizing ancient architectural sites on Hainan Island were quantitatively assessed through meticulous field investigations. Detailed information regarding these plants, encompassing various biological and ecological traits, was meticulously gathered. These traits included life forms (herbs, shrubs, trees), life cycles (annuals, perennials), native status (native species, introduced species), cultivation methods (cultivated species, wild species), and utilitarian attributes (edible and ornamental values). This comprehensive data was primarily extracted from authoritative sources, specifically the "Flora of China," which provides an extensive catalog of the region's botanical diversity. This methodological approach not only facilitated a thorough analysis of epiphytic species associated with historical structures but also enabled an exploration of their ecological roles and conservation importance in the context of cultural heritage sites.

2.3. Data Sources and Basis for Ancient Architecture

The selection of ancient architectures for this study encompassed a diverse range of sites across Hainan Island, segmented geographically into Northern, Eastern, Western, and Southern regions. A total of 44 representative ancient buildings were surveyed, with the Northern Hainan Island region contributing the highest number of sampling points. Data collection was rigorously conducted through field research and consultations with the relevant management departments, focusing on multiple parameters such as area, height, building age, geographic coordinates (longitude and latitude), annual maintenance frequency, and daily tourist visitation numbers.

Utilizing the "National Key Cultural Relics Protection Units" list issued by the National Cultural Heritage Administration of China, the buildings were categorized based on their functional roles, including residential structures, defensive buildings, religious edifices, memorial sites, garden architectures, and other miscellaneous types. A comprehensive summary table of these historical architectures was compiled (

Table S1), revealing detailed insights into the epiphytic flora associated with these structures across the four geographic subdivisions: Qiongbai, Qiongnan, Qiongdong, and Qiongxi. The Qiongbai region, in particular, was noted for its frequent selection, exhibiting a richer diversity and greater number of epiphytic specimens.

The sampled buildings predominantly date back to the 15th and 16th centuries, with an average footprint of 8,072 square meters. A breakdown of the surveyed sites revealed 25 residential buildings, 8 defensive structures, 5 religious sites, 1 commemorative edifice, and one each classified under garden architecture and other categories. This distribution reflects Hainan's historical role as a cultural crossroads, assimilating influences from mainland Chinese settlers, British and French colonials, and overseas Chinese from Southeast Asia, which is particularly evident in the predominance of residential architectures [

15].

Moreover, an analysis of the distribution patterns of these ancient buildings indicated that a majority are located in suburban and rural areas, with only 10 situated in urban settings, representing 22.72% of the total. This distribution is indicative of the broader impacts of urbanization and its influence on the preservation and utilization of historical sites. The findings from this comprehensive survey provide a foundational understanding for further exploring the ecological and cultural significance of epiphytic plants in relation to ancient architectural heritage on Hainan Island.

2.4. Driving Variables

For the investigation of driving mechanisms, a comprehensive set of twelve potentially relevant factors was meticulously selected. This selection comprises seven architectural-related variables recorded during the survey: area, height, construction year, longitude, latitude, annual maintenance frequency, and daily tourist numbers. In addition to these, socio-economic variables were also considered. These include surrounding population density, growth rate of government general public budget revenue, number of commercial outlets nearby, regional passenger traffic, and extent of greening coverage, all of which were assessed at the township level. The data pertaining to these socio-economic factors were extracted from the "General Gazetteer of the People's Republic of China - Hainan Volume." Notably, the revenue growth rate data was sourced directly from township government websites. This robust analytical framework integrates both architectural characteristics and socio-economic contexts, providing a holistic approach to understanding the factors that influence the distribution and diversity of epiphytic plants on ancient architectures in Hainan.

2.5. Data Analysis of Driving Mechanisms

This study concentrates on the epiphytic vascular plants associated with ancient architecture, investigating the relationship between plant richness, abundance, and various spatial and socio-economic driving factors. A Generalized Linear Model (GLM) was employed to assess the correlations between epiphytic plant species richness and abundance and the associated environmental and socio-economic variables [

16,

17]. Data normalization was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 23.1, applying z-score normalization to all response and predictor variables. Outlier values, identified as those greater than 3 or less than -3, were excluded to ensure the integrity of linear regression model predictions.

Two linear regression models were developed, utilizing epiphytic plant species richness and abundance as predictor variables and incorporating the twelve driving factors as response variables. Model selection was guided by the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), favoring models with an AIC less than zero, and the Adjusted R-squared values, with a preference for models exhibiting Adjusted R-squared values greater than 0.3 [

18]. Significant predictor variables were identified based on their β-coefficients and P-values, with a threshold of less than 0.01 for significance.

Further, the variables were categorized into distinct groups—herbs, shrubs, trees, annuals, perennials, native species, introduced species, cultivated species, wild species, ornamental values, and edible values. Separate linear regression models were then constructed for the richness and abundance of epiphytic plant species on ancient architecture, using only predictor variables that demonstrated significant P-values greater than 0.01. This rigorous analytical process yielded robust results, adhering to consistent evaluative standards. All statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.3.2 and IBM SPSS Statistics 25.0.0, ensuring comprehensive and reliable findings.

3. Results

3.1. The Spatial Distribution of Epiphytic Flora

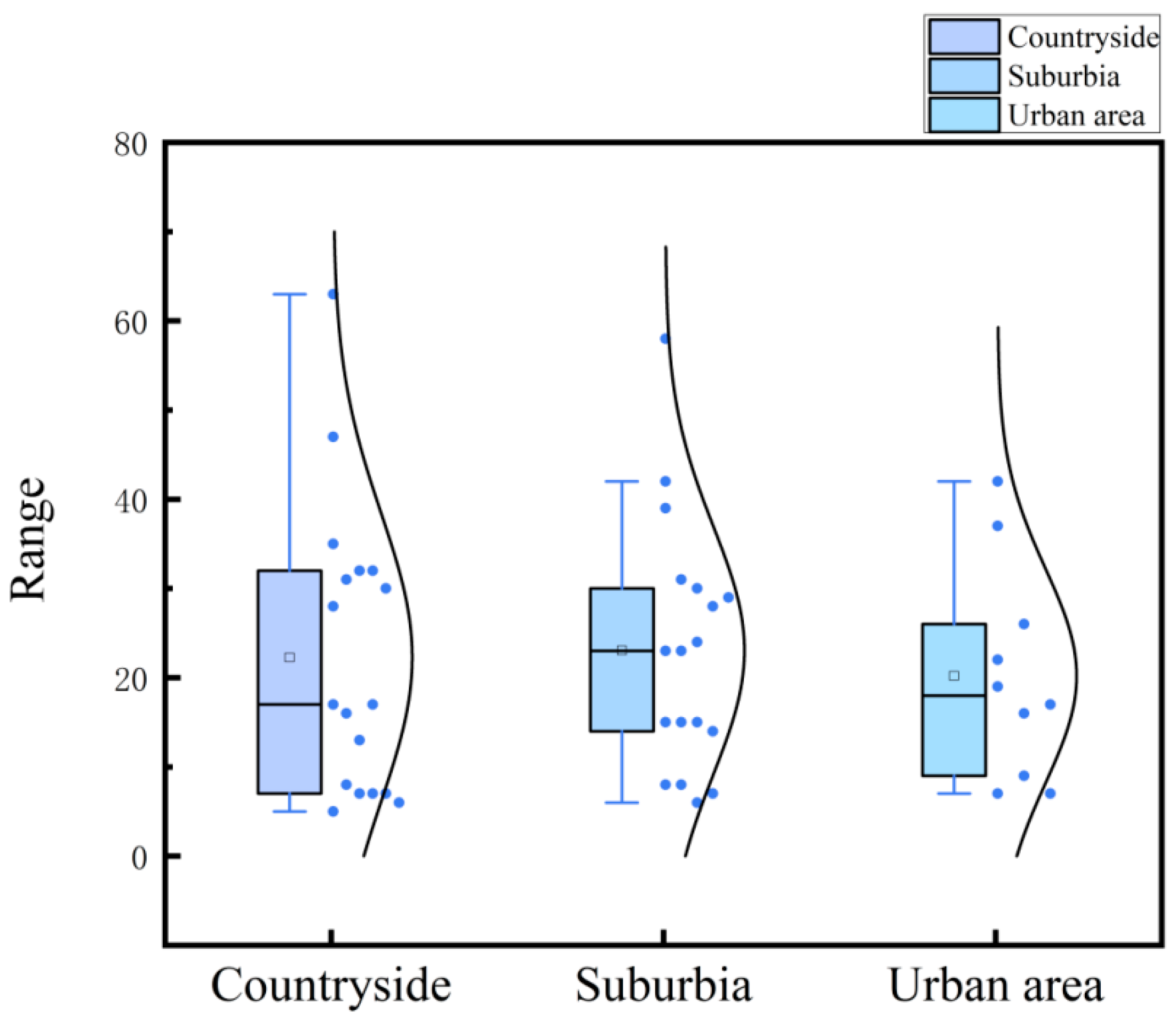

To delve deeper into the spatial distribution of epiphytic flora associated with ancient buildings, I examined whether species richness correlates with the locations of these structures. The findings, as visualized in a boxplot of species richness across different regional ancient architectures (

Figure 2), reveal that the highest levels of species richness are observed in suburban regions, followed by urban and rural areas. This suggests that, relative to urban settings, suburban and rural areas tend to harbor a more diverse assemblage of epiphytic flora on ancient architecture.

However, the results of the ANOVA test (

Table 1) indicate no statistically significant differences in species richness across these regions, with P-values exceeding 0.05. Consequently, we must conclude that there is no significant variation in the species richness of epiphytes on ancient buildings across urban, suburban, and rural areas. Nonetheless, the validity of this conclusion may be subject to debate, potentially influenced by the choices made during the sampling process. This caveat highlights the need for cautious interpretation of the data and suggests that further research, possibly with different sampling strategies or larger sample sizes, might be required to draw definitive conclusions about the spatial distribution of epiphytic species on ancient architecture.

Figure 1.

Ancient buildings of different functional types in Hainan) A:Five Ancestral Hall (Garden building) B:Meilang Twin Pagodas (Religious building) C:Fuxing Building (Defensive building) D:Haikou Old Arcade Street (House building) E:Lin Hong Gao Wai Lou (Monumental building) F:Ding'an Ancient City Wall (Defensive building).

Figure 1.

Ancient buildings of different functional types in Hainan) A:Five Ancestral Hall (Garden building) B:Meilang Twin Pagodas (Religious building) C:Fuxing Building (Defensive building) D:Haikou Old Arcade Street (House building) E:Lin Hong Gao Wai Lou (Monumental building) F:Ding'an Ancient City Wall (Defensive building).

Figure 2.

Box plots of species richness of ancient buildings in different regions.

Figure 2.

Box plots of species richness of ancient buildings in different regions.

3.2. The Characteristics of Epiphytes

The comprehensive survey of epiphytic plants associated with ancient architecture yielded significant findings regarding their diversity and distribution. A total of 25,614 epiphytic plants were identified, classified into 80 families, 196 genera, and 255 species. This diversity underscores the rich botanical resources present on ancient structures in Hainan Province. Detailed statistical analysis (

Table 2) highlighted several dominant families, including Moraceae, Urticaceae, Polypodiaceae, Nephrolepidaceae, Adiantaceae, and Compositae, which collectively constitute the core of the epiphytic flora in the region.

Notably, the Moraceae family emerged as the most prevalent, with 5,849 individuals accounting for 22.84% of the entire sample. At the species level, Ficus pumila was the most abundant, with 4,879 individuals representing 19.05% of the total epiphytic population. Other significant species included Pilea microphylla (14.82%), Phymatosorus scolopendria (8.79%), Nephrolepis auriculata (7.44%), and Adiantum caudatum (5.68%). These species are predominantly native to Hainan and are primarily found in their natural habitats, exhibiting both edible and ornamental values.

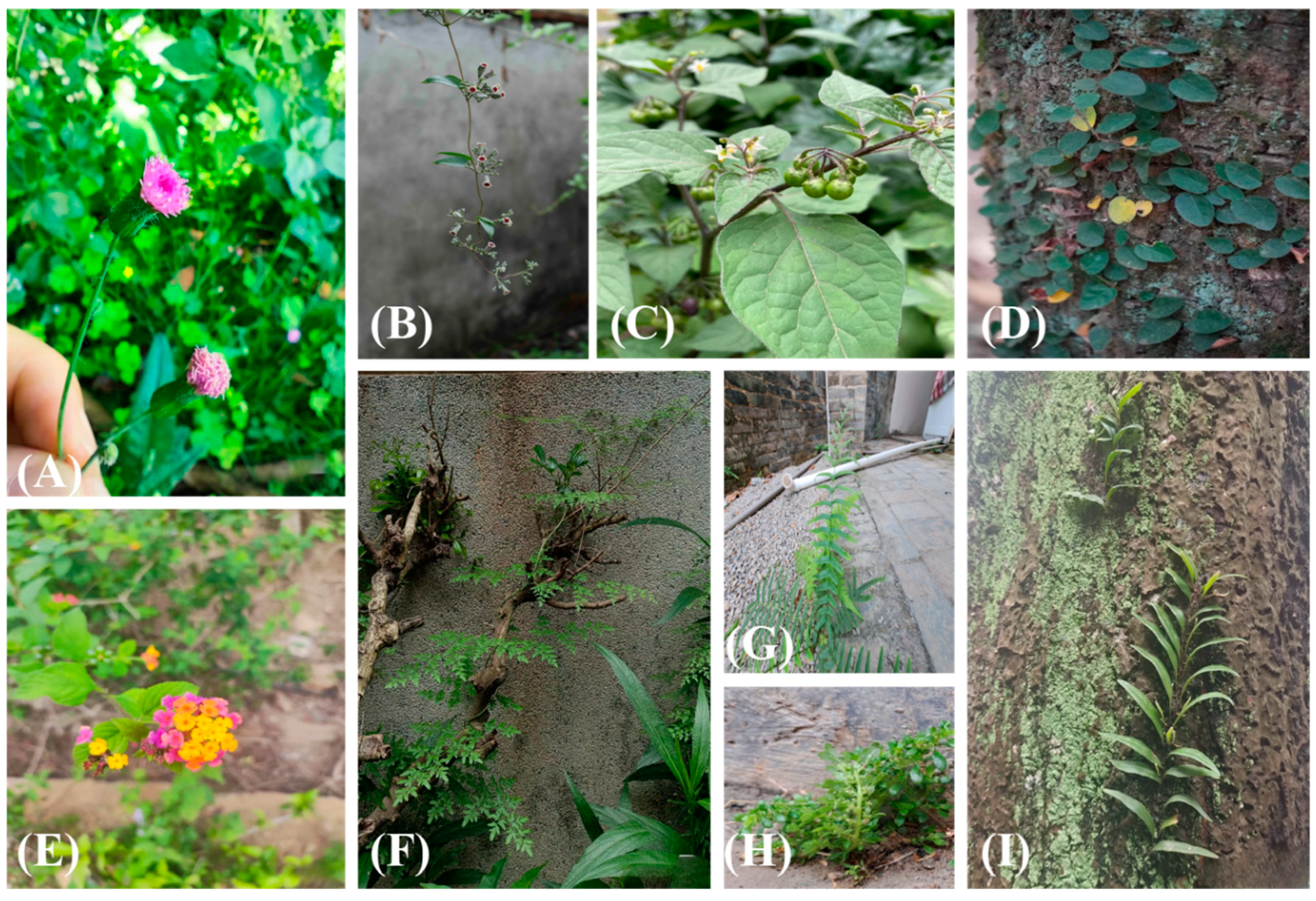

Figure 3.

Represent species of Hainan ancient epiphytes of ancient buildings. A: Emilia sonchifolia, B: Paederia scandens, C: Ficus hispida, D: Ficus pumila, E: Lantana camara, F: Lygodium japonicum, G: Eremochloa ciliaris, H: Pilea microphylla, I: Pyrrosia adnascens.

Figure 3.

Represent species of Hainan ancient epiphytes of ancient buildings. A: Emilia sonchifolia, B: Paederia scandens, C: Ficus hispida, D: Ficus pumila, E: Lantana camara, F: Lygodium japonicum, G: Eremochloa ciliaris, H: Pilea microphylla, I: Pyrrosia adnascens.

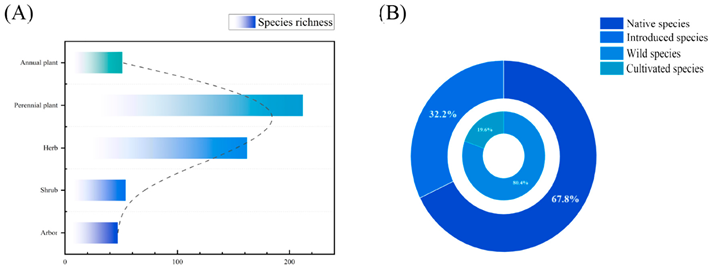

The epiphytic flora on Hainan Island's ancient structures is both diverse and abundant, demonstrating a wide range of ecological adaptations. According to the analysis presented in the bar chart (

Figure S1, A), herbaceous species significantly dominate the flora, comprising 162 species or 63.53% of the total. Prominent among these are

Pilea microphylla,

Phymatosorus scolopendria,

Nephrolepis auriculata, and

Adiantum caudatum, which typically inhabit the crevices and joints of the epiphytic foliage found on these ancient buildings.

Further analysis of life cycles shows a distinct predominance of perennial over annual species. The perennial species, which include Ficus pumila, Phymatosorus scolopendria, Nephrolepis auriculata, Adiantum caudatum, Eupatorium odoratum, and Ficus hispida, account for 212 species or 83.14% of the epiphytic plants surveyed. This indicates that the majority of epiphytic species thriving on ancient architecture are perennial herbaceous varieties, adapted to the microhabitats offered by these historic structures.

The pie chart (

Figure S1, B) detailing the species richness of epiphytic plants categorizes them into cultivated and wild types, revealing that wild species dominate, constituting 80% of the total or 205 species. In contrast, cultivated species comprise 20%, totaling 50 species. Prominent wild species include

Pilea microphylla,

Adiantum caudatum,

Eupatorium odoratum, and

Ficus hispida, while cultivated species are primarily represented by

Nephrolepis auriculata,

Ficus pumila,

Ficus concinna, and

Alocasia macrorrhiza.

Further categorization by origin shows that native species account for 68% (173 species) including Nephrolepis auriculata and Adiantum caudatum, while non-native species represent 32% or 82 species, with notable examples such as Pilea microphylla and Eupatorium odoratum. This highlights a significant presence of native flora within the epiphytic community on ancient structures.

The species are also differentiated by their ornamental and edible values. Ornamental species, which include Nephrolepis auriculata, Cissus repens, and Pteris ensiformis, are more prevalent. Conversely, edible species like Cleome rutidosperma, Acalypha indica, Coccinia grandis, and Solanum photeinocarpum are less common. Some species, such as Ficus pumila and Portulaca pilosa, offer dual benefits, being both ornamental and edible.

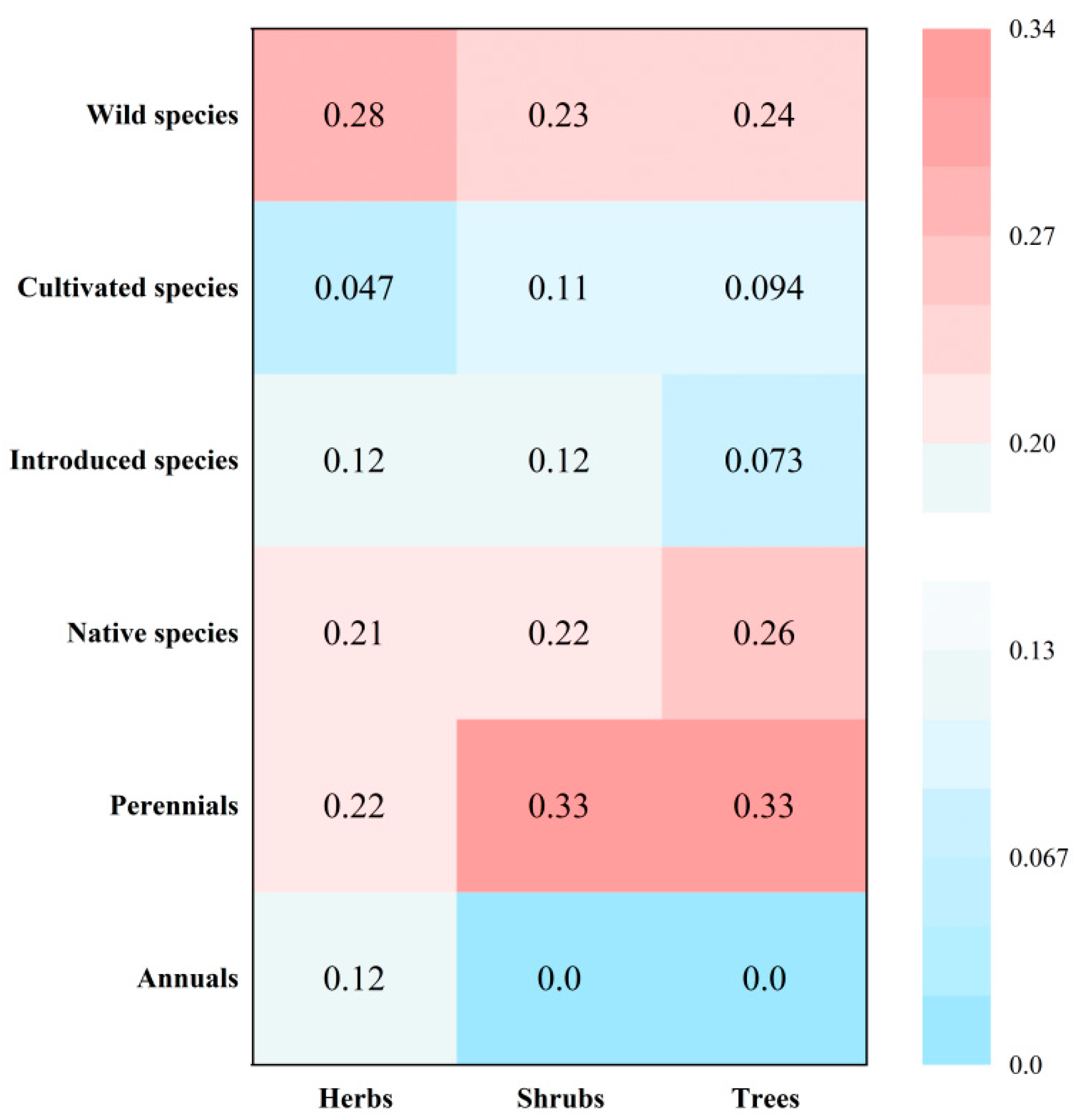

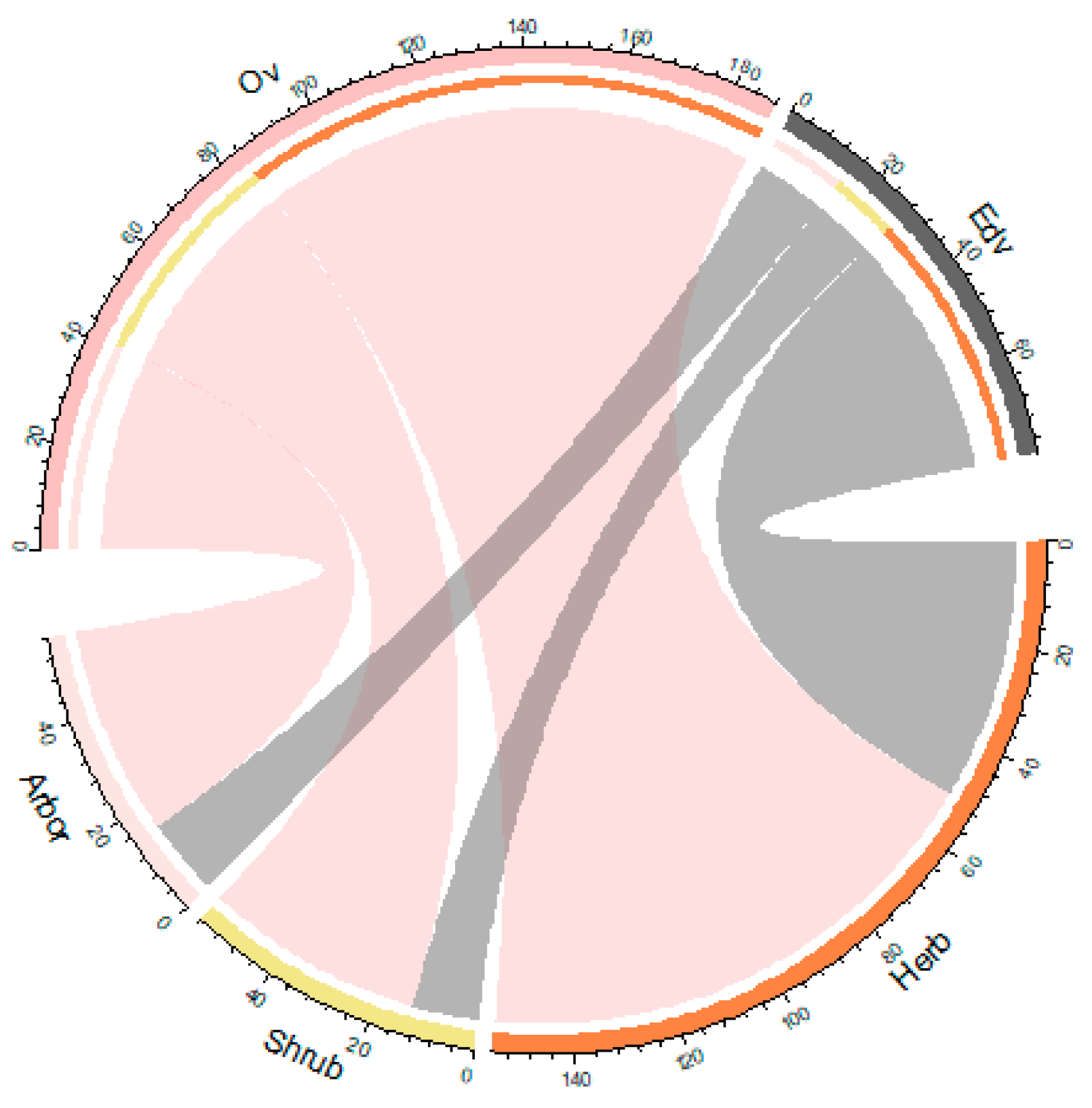

The heat map (

Figure 4) shows that wild species form a larger proportion of the herbs category (0.28), while native species are more prevalent among trees (0.26). Additionally, the chord diagram (

Figure 5) reveals that the primary utility value of these species is ornamental, with respective counts of 104, 43, and 41 species making up 67.10%, 76.79%, and 73.21% of each plant category. Notably, 57 species possess both ornamental and edible values, while 51 species lack both, underscoring the diverse functional roles of these epiphytes.

3.3. Drivers of Epiphyte Species Richness and Abundance in Ancient Buildings (Overall)

The initial linear regression model, which analyzed the species richness of epiphytic plants associated with ancient architecture (

Table 3), demonstrated a strong adherence to linearity, with highly significant P-values (P < 0.001). The model exhibited robust goodness of fit, evidenced by an Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) of -506.31 and an Adjusted R-squared (R²) of 0.44, which aligns well with the predictive requirements of this study.

Among the twelve response variables analyzed, several showed highly significant correlations with species richness. Notably, the longitude and latitude of the ancient structures were strongly associated with species richness. Similarly, the land area occupied by the structure (β coefficient ***) and the building age (β coefficient ***) were significantly linked to species richness, suggesting that larger and older structures tend to support more diverse epiphytic plant communities.

Economic factors also played a critical role, as indicated by the significant correlations with the growth rate of general public budget revenue (β coefficient ***) and the number of commercial outlets in proximity (β coefficient ***). The average annual passenger traffic in the area showed a strong negative correlation (β coefficient ***), suggesting that higher human traffic might negatively impact species richness.

Other architectural and environmental factors such as the height of the ancient architecture (β coefficient **), the daily average passenger count (β coefficient **), and green coverage in the surrounding area (β coefficient **) also demonstrated significant correlations, albeit with smaller effect sizes. However, no significant correlation was observed with the surrounding population density or the frequency of annual repairs to the structure.

The linear regression model that employs plant abundance as the predictor variable also exhibits a good fit and applicability, outperforming the previous model focused on species richness. This is evidenced by an Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) of -710.11 and an Adjusted R-squared (R²) of 0.59, with highly significant P-values (P < 0.001), indicating a robust model performance.

Cross-referencing with the overall driving factors of epiphytic plants as listed in

Table 3, several variables show highly significant correlations with plant abundance. Specifically, the longitude of the ancient architecture demonstrates a strong negative correlation (β coefficient ***), suggesting that geographical positioning significantly influences plant abundance. Similarly, the land area (β coefficient ***) and the building age (β coefficient ***) are significantly associated with the abundance of epiphytic plants, indicating that larger and older structures tend to support a greater abundance of these plants.

Socio-economic factors such as surrounding population density (β coefficient ***), growth rate of general public budget revenue (β coefficient ***), and the number of commercial outlets (β coefficient ***) also show strong correlations. These factors may reflect the impact of human activity and economic development on the ecological environment of epiphytic plants. Furthermore, the average daily passenger count (β coefficient ***) and the annual passenger traffic in the region (β coefficient ***) indicate that higher human traffic negatively affects plant abundance.

Notably, no significant correlations are observed with the height of the ancient architecture, latitude, frequency of annual repairs, or the green coverage in the vicinity. This suggests that these variables may not play a crucial role in determining the abundance of epiphytic plants on these ancient structures.

The analysis of two linear regression models has elucidated the significant factors influencing both the species richness and plant abundance of epiphytic flora associated with ancient architecture. The longitude of the ancient architecture and the growth rate of the general public budget revenue are identified as the most significant positively correlated factors affecting both dependent variables. These findings suggest that geographic location and local economic conditions play crucial roles in supporting the ecological diversity and abundance of epiphytic plants.

Conversely, the average annual passenger traffic in the area exhibits the most notable negative correlation with both species richness and plant abundance. This negative impact highlights the potential disturbances caused by high human traffic, which may interfere with the ecological balance necessary for the growth of epiphytic plants.

In the subsequent analyses, I will select response variables that exhibit significant influences on the predictive variables, specifically those with significant correlations (P-values < 0.01), while discarding driving factors that lack sufficient associations with the predictive variables.

3.4. Analysis of Species Richness and Plant Population Drivers of Ancient Architectural Epiphytes (Taxonomic)

The analysis of driving factors for epiphytic plant richness (

Table 4) and abundance (

Table 5) provides predictive models that meet the expected usage criteria (AIC < 0, Adjusted R² > 0.3). These models can be leveraged to investigate the variations in biological richness and the mechanisms influencing plant abundance, offering broader applications.

For species richness (

Table 4), categorized by herbaceous plants, shrubs, and trees, the results indicate that the growth rate of public budget revenue and the number of surrounding commercial outlets exhibit a highly significant positive correlation across all plant categories. However, the annual average passenger volume in the region shows a strong positive correlation with herbaceous plants, while it is significantly negatively correlated with shrubs and trees. Notably, the area occupied by ancient buildings is positively correlated with herbaceous plants but does not significantly impact shrubs or trees. Building age shows a positive correlation with herbaceous plants and a negative correlation with trees, with no significant relationship to shrubs.

When distinguishing between annual and perennial plants, the longitude of ancient buildings and the growth rate of public budget revenue are strongly positively correlated with the richness of both categories. In contrast, the annual average passenger volume is highly negatively correlated with both. The area occupied by ancient buildings is negatively correlated only with annual plants, while perennial plants remain unaffected. Additionally, the number of surrounding commercial outlets significantly correlates with perennial plants alone.

For native and non-native species, the growth rate of public budget revenue maintains a strong positive correlation for both, whereas the annual average passenger volume is negatively correlated. The height, area, and construction year of ancient buildings are all negatively correlated with native species.

In the case of cultivated versus wild species, the latitude of ancient buildings and the growth rate of public budget revenue exhibit highly significant positive correlations, while the annual average passenger volume shows a significant negative correlation for both categories. The area and construction year of ancient buildings are negatively correlated only with wild species.

Finally, in the analysis by value classification, there are no significant overall differences between the two plant categories. Both exhibit positive correlations with the longitude of ancient buildings, the growth rate of public budget revenue, and the number of surrounding commercial outlets, while showing negative correlations with the annual average passenger volume.

The analysis of epiphytic plant abundance (

Table 5) reveals the following key findings: For herbaceous, shrub, and tree categories, only the number of surrounding commercial outlets shows a highly significant positive correlation with the abundance of all three plant types. The longitude of ancient buildings is positively correlated with herbaceous and tree species, while surrounding population density and the growth rate of public budget revenue exhibit highly significant positive correlations with herbaceous plants alone. Conversely, significant negative correlations are observed between herbaceous plant abundance and both the area occupied by ancient buildings and the annual average passenger volume.

When considering annual and perennial plants, the longitude of ancient buildings, surrounding population density, and the growth rate of public budget revenue all show highly significant positive correlations with both categories. However, the annual average passenger volume is negatively correlated with both categories. Notably, the daily passenger quantity of ancient buildings shows a highly significant negative correlation with perennial plants but no evident correlation with annual plants.

For native and non-native species, the correlations with driving factors are consistent across both categories. Both exhibit highly significant positive correlations with the longitude of ancient buildings, the growth rate of public budget revenue, and the number of surrounding commercial outlets. Meanwhile, significant negative correlations are found with the area occupied by ancient buildings and the annual average passenger volume.

In the classification of cultivated versus wild species, the longitude of ancient buildings, the growth rate of public budget revenue, and the number of surrounding commercial outlets exhibit highly significant positive correlations for both plant types. Both categories also show significant negative correlations with the annual average passenger volume. However, the area occupied by ancient buildings and the daily average passenger quantity are negatively correlated only with wild species, while surrounding population density is positively correlated solely with wild species.

For value-based classification, the longitude of ancient buildings, surrounding population density, the growth rate of public budget revenue, and the number of surrounding commercial outlets all show highly significant positive correlations. The annual average passenger volume, however, exhibits a highly significant negative correlation.

Throughout all analyses, only factors with P-values < 0.001, indicating highly significant differences, were considered. Marginally significant factors were intentionally excluded to minimize errors and increase the accuracy of the findings, ensuring that the results are more representative.

4. Discussion

4.1. Species Composition of Epiphytes of Ancient Buildings on Hainan Island

The preservation of a diverse and abundant assemblage of epiphytic plants in ancient architecture can be attributed to several factors. First, over centuries of plant cultivation, humans have imbued various plants with cultural and spiritual significance based on their growth habits and aesthetic preferences. This historical tradition led ancient peoples to cultivate a variety of plants within residences and gardens, enhancing aesthetic appeal and contributing to the presence of epiphytic plants in ancient buildings [

19].

Second, the proliferation of epiphytic plants has paralleled the development of human civilization, particularly through cultural exchanges and economic globalization. For example, the ancient Romans adopted plant cultivation techniques involving tree miniaturization, likely introduced through trade with China, which significantly contributed to the diversity of epiphytic plants [

20].

Third, a significant portion of the epiphytic flora found on ancient architecture consists of naturally occurring wild species from surrounding areas. These species often possess adaptations that enable them to survive in harsh environments, such as cracks and crevices, further contributing to the richness of epiphytes in these historical structures [

21].

The results of the current study reveal that the dominant epiphytic plants in ancient architecture predominantly belong to the families Polypodiaceae, Aspleniaceae, and Pteridaceae, which comprise 6,232 specimens or 24.33% of the total plant community. This finding contrasts with the epiphytic plant diversity in the tropical coniferous forests of Hainan Island, where the Orchidaceae family dominates [

22]. Similarly, the epiphytic species composition in subtropical and temperate forests is dominated by ferns [

23]. These disparities underscore the distinct assemblages between epiphytic species in ancient architecture and those in natural environments, which may be related to the predominance of rock-dwelling ferns in urban habitats. These ferns, better suited to the ecological niches provided by ancient architectural surfaces, align more closely with urban environments [

24].

This phenomenon can be further explained by the urban cliff hypothesis [

25,

26,

27], which posits that the vertical surfaces of man-made structures create new ecological niches for lithophytic ferns. These ferns, compared to other epiphytic plants, derive greater benefits from such niches, establishing them as dominant species in these environments.

A point of interest is the prevalence of Ficus pumila as the most dominant species within this epiphytic community. According to the literature, Ficus pumila is widely distributed in southeastern China, particularly in Guangdong and Hainan, thriving at elevations between 50 and 800 meters. Its climbing nature allows it to spread across village structures and trees, providing extensive living space. As a drought-tolerant and sun-adapted species, Ficus pumila can endure higher light levels and drier environments, giving it a competitive advantage over other climbing plants. This adaptability allows Ficus pumila to thrive on ancient architecture exposed to direct sunlight, making it a dominant species among the vascular plants in these epiphytic communities on Hainan Island.

4.2. Composition of Epiphyte Classes for Ancient Buildings on Hainan Island

Herbaceous and perennial species demonstrate significant advantages as plant types, while wild and native species possess notable benefits over cultivated and introduced species. This pattern is consistent with findings regarding wall plants in Chongqing [

28], which may suggest a broader geographic consistency in the composition of architectural epiphytes. The dominance of native species over introduced ones within epiphytic plant communities in ancient architecture has been explored in several studies. One primary explanation is that ancient structures often integrate horticultural design, with gardens acting as important conduits for the introduction of non-native species [

29]. Simultaneously, these gardens provide refuges for native and endangered species [

30], thereby contributing to the conservation of native flora. This aligns with the findings in this paper, which suggest that ancient architecture plays a key role in preserving native species, thus reducing their risk of endangerment.

Further research indicates that in urban floras, the species-area relationship for introduced species is significantly higher than that for native species. This suggests that as urban areas expand, the proportion of introduced species in the flora increases [

31]. The diversity of introduced species is closely tied to human activities, with species richness often increasing in correlation with human influence [

32,

33]. In the context of this study, the average land area of ancient structures is relatively small (8072.14 m²), and most are located in suburban or rural areas with limited human activity. As a result, introduced species are relatively rare, allowing native species to dominate.

Regarding the distinction between cultivated and wild species, a study conducted in Zhanjiang—a tropical city with a climate similar to that of Hainan Island—revealed that both the number of cultivated species and their phylogenetic diversity are significantly correlated with urban population density [

34]. Given that the population density around ancient structures is much lower compared to urban centers, the abundance and richness of cultivated species are substantially lower, allowing wild species to dominate. Additionally, wild species often exhibit greater adaptability than native species in urban floras [

35,

36], further reinforcing their prevalence in these settings.

4.3. Analysis of Epiphyte Driving Mechanisms in Ancient Buildings on Hainan Island

Longitude serves as a crucial indicator of climate on Hainan Island, and the analysis reveals a clear trend: as longitude increases, species richness and the abundance of epiphytic plants associated with ancient architecture also rise. This trend can be linked to the longitudinal zonality of Hainan Island, which drives variations in precipitation from east to west. Higher longitudes correlate with increased precipitation [

37]. Additionally, the richness and abundance of epiphytic plants around ancient structures show a strong positive correlation with indicators of regional economic development, such as the growth rate of general public budget income and the number of surrounding commercial outlets. Thus, a clear conclusion emerges: the higher the level of economic development around ancient architecture, the greater the species richness and abundance of epiphytic plants [

38].

However, it is worth noting that our findings did not distinguish the differential impacts of economic development on specific plant categories, such as herbs, arbors, and shrubs. Another noteworthy finding is the highly significant negative correlation between the annual average passenger volume in the region and both the species richness and abundance of epiphytic plants associated with ancient architecture. Upon closer examination, only the species richness of herbaceous plants showed a positive relationship with this variable, while other categories exhibited negative correlations. This finding contrasts sharply with previous research, which suggested that transportation infrastructure, such as road and rail networks, enhances species richness, particularly for non-native species in adjacent areas [

39,

40,

41]. These studies support the city-to-city transfer hypothesis [

42], which posits that certain species disperse through intercity transportation corridors.

We attribute this discrepancy to the fact that earlier studies primarily surveyed areas adjacent to major transportation routes, whereas ancient structures may not be located near such corridors. Instead, the overall transport connectivity in the region could contribute to habitat fragmentation, leading to reduced species richness and abundance of epiphytic plants around ancient architecture. This fragmentation may disrupt plant communities, explaining the negative correlation observed in our findings.

Additionally, we observed a highly significant negative correlation between the land area occupied by ancient buildings and the richness of epiphytic plants. This contrasts sharply with findings from urban green spaces, where increased green space area is typically associated with higher species richness [

43,

44]. We propose that this discrepancy arises from the unique characteristics of ancient architecture compared to other urban green spaces like parks, cemeteries, or forests. Ancient structures are often dominated by large edifices; as the green space area increases, so does the footprint of the buildings, while the space available for epiphytic plants remains relatively limited. This dynamic likely explains the observed negative correlation.

Regarding population density, we found a strong positive correlation specifically with herbaceous plants, but no significant correlation with arbors and shrubs. Studies have shown that population density can directly contribute to local plant species extinction, primarily due to the degradation of community structure [

45] and reduced green spaces [

46]. However, ancient structures often act as "sanctuaries," protected and maintained by relevant authorities, insulating the epiphytic plant communities from the typical impacts of urban density. This protective effect likely explains why population density does not appear to degrade the epiphytic plant communities on ancient buildings, suggesting that these structures may serve as refuges for diverse plant species.

We also discovered a highly significant negative correlation between the construction age of ancient buildings and the abundance of edible plant species, while the correlation with ornamental plants was less pronounced. This finding suggests that older structures tend to host a greater presence of edible epiphytes. We hypothesize that this may be related to the traditional consumption of such plants by indigenous groups, like the Li ethnic group on Hainan Island [

47]. Over time, as Hainan Island developed, the range of activities associated with these minority groups and consequently, the epiphytic plants they utilized diminished. This may be one factor among many that influence this phenomenon, hinting at a complex interplay between cultural practices and plant ecology.

Importantly, the epiphytic plants on ancient architecture may serve as reflections of historical shifts, almost like living fossils of their time. This opens up an intriguing avenue for further research, exploring how these plants serve as biological markers of past eras. Ancient structures function as distinct urban green spaces, differing from other environments in terms of species composition and the factors influencing their communities. This study highlights the need for further exploration into the unique biological communities associated with ancient architecture, shedding light on their ecological and historical significance.

4.4. Suggestions for Conservation of Ancient Buildings on Hainan Island

The conservation of ancient architecture is deeply intertwined with the understanding and management of epiphytic plants that grow on these structures. Species like

Ficus pumila play a significant role in enhancing urban microclimates by increasing humidity, releasing oxygen, and adsorbing atmospheric particulates [

48]. They also contribute to the aesthetic value of landscapes, greatly enhancing their visual appeal [

49]. However, epiphytic plants can also have negative impacts on the materials of ancient buildings. They may cause biological degradation through physical damage from root growth or chemical damage from secreted substances [

50].

This analysis suggests that while it is important to enhance the species diversity of epiphytic plants on ancient buildings, controlling their numbers is equally critical to maintaining ecological balance and ensuring the structural integrity of these buildings. Increasing greenery around ancient sites can promote the diversity of epiphytic plant communities and integrate them with surrounding biological ecosystems, such as bird populations, thereby fostering ecological stability. Regular assessments of epiphytic plant growth by relevant authorities are essential. If a plant species poses a risk to the structural integrity of a building, timely removal and repair are necessary to prevent further damage.

Different categories of plants exhibit unique attributes. Native species, for instance, help counteract the homogenization caused by exotic cultivated species in urban landscaping, potentially reducing maintenance costs [

51]. Large, historic trees often serve as living witnesses to the past, preserving the cultural heritage associated with ancient buildings. Therefore, it is recommended that for older structures, a catalog of native epiphytic plants should be created to guide conservation efforts. For newer structures, assessments should be conducted to introduce appropriate native species that align with local environmental conditions. The analysis also reveals a strong positive correlation between tree abundance near ancient structures and geographical longitude, suggesting that the growing conditions and climates suitable for trees near historic sites should be carefully studied to ensure proper preservation.

Moreover, contemporary technologies such as big data and cloud computing can significantly contribute to the protection of ancient architecture. These tools allow for the collection of comprehensive information from a macro perspective, enabling preemptive action against potential threats and the development of targeted conservation strategies. Public awareness should also be raised through promotional campaigns to enhance tourists' commitment to the preservation of these structures. The protection of ancient architecture is a multifaceted challenge that requires the collective efforts of scientists, conservationists, and the public. By integrating ecological management with technological advancements and public engagement, we can ensure that these historical edifices continue to endure.

5. Conclusions

Our research reveals that the dominant taxa of epiphytic plants associated with ancient architecture, ranked in descending order, are Moraceae, Urticaceae, Polypodiaceae, Dennstaedtiaceae, and Aspleniaceae. The most prominent species include Ficus pumila, Pilea microphylla, Phymatosorus scolopendria, Nephrolepis auriculata, and Adiantum caudatum. The diversity of epiphytic plants on ancient structures in Hainan Island is considerable, with herbaceous plants, perennial species, wild varieties, indigenous flora, and edible species dominating. Edible species are notably prevalent across herbaceous, shrub, and tree categories. Additionally, our analysis of 44 ancient buildings shows that species richness of epiphytic plants is significantly higher in suburban and rural areas compared to urban settings. In terms of driving factors, variables such as the longitude of ancient architecture and the growth rate of government general public budget revenue show a strong positive correlation with species richness and plant abundance, while the annual average passenger volume exhibits a significant negative correlation. When analyzing driving factors by category, it becomes clear that different categories are influenced by distinct variables, emphasizing the need for context-specific analysis. This study employs field survey data from ancient buildings, combined with computational data processing, to systematically analyze the diversity and composition of epiphytic plant communities. We examined the driving mechanisms behind species richness and abundance from both a holistic and categorical perspective. Based on our findings, we recommend enhancing the diversity of epiphytic plant communities through controlled management of driving factors, such as expanding green spaces and improving artificial management, while regulating plant numbers to avoid overgrowth. A coordinated, comprehensive approach should be adopted to ensure the holistic protection of ancient architecture, balancing conservation with ecological health.