Submitted:

06 December 2024

Posted:

06 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Neurological Disorders – Morbidity and Mortality

1.2. AI in CAD

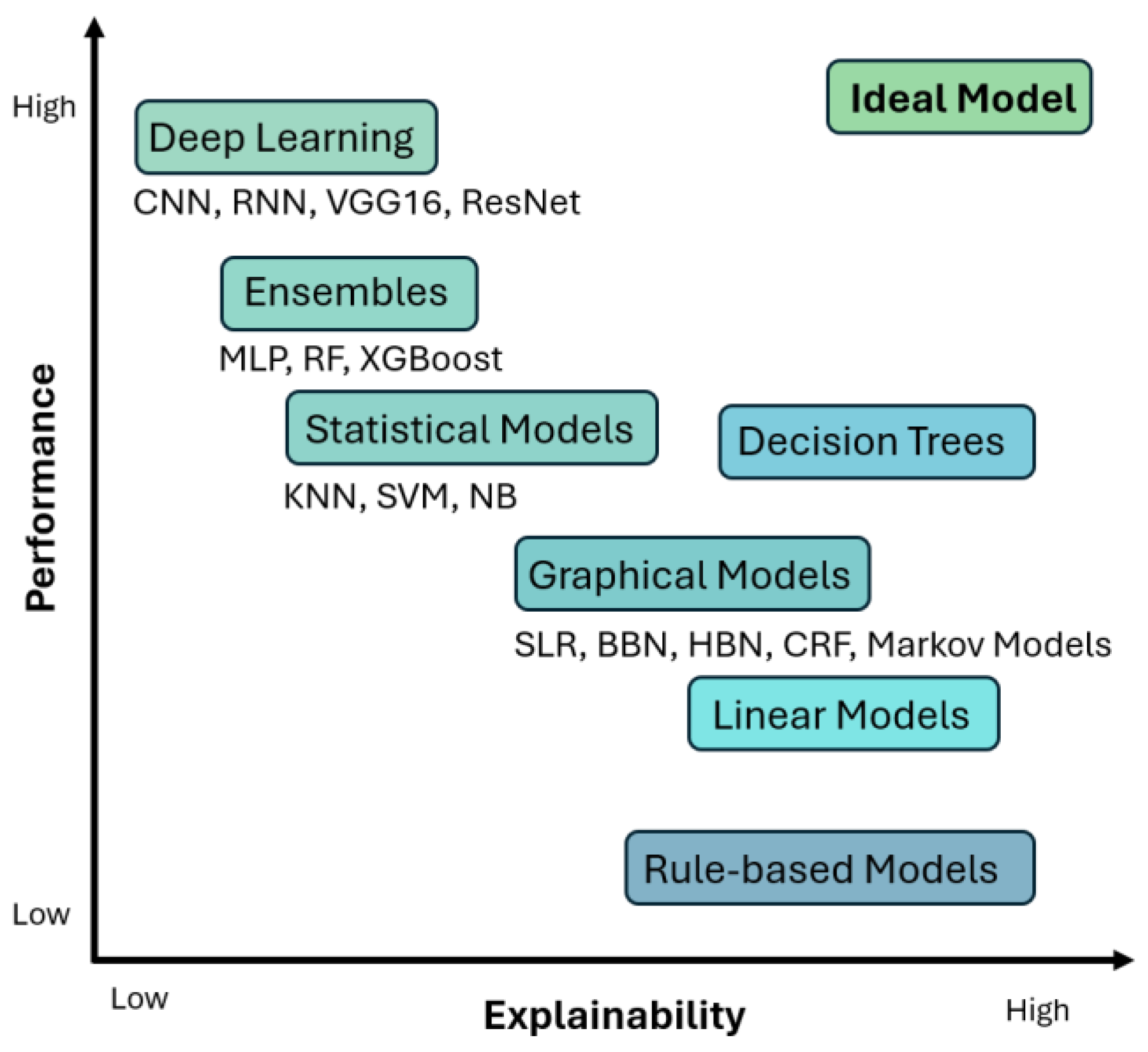

- Interpretability: Interpretability refers to the ability to understand the decision-making process of an AI model. The operation of an interpretable model is transparent and provides details about the relationships between inputs and outputs.

- Explainability: Explainability refers to the ability of an AI model to provide clear and intuitive explanations of the decisions made to the end user. In other words, an explainable AI model provides justification of the decisions made.

- Transparency: Transparency refers to the ability of an AI model to provide a view into the inner workings of the system, from inputs to inferences.

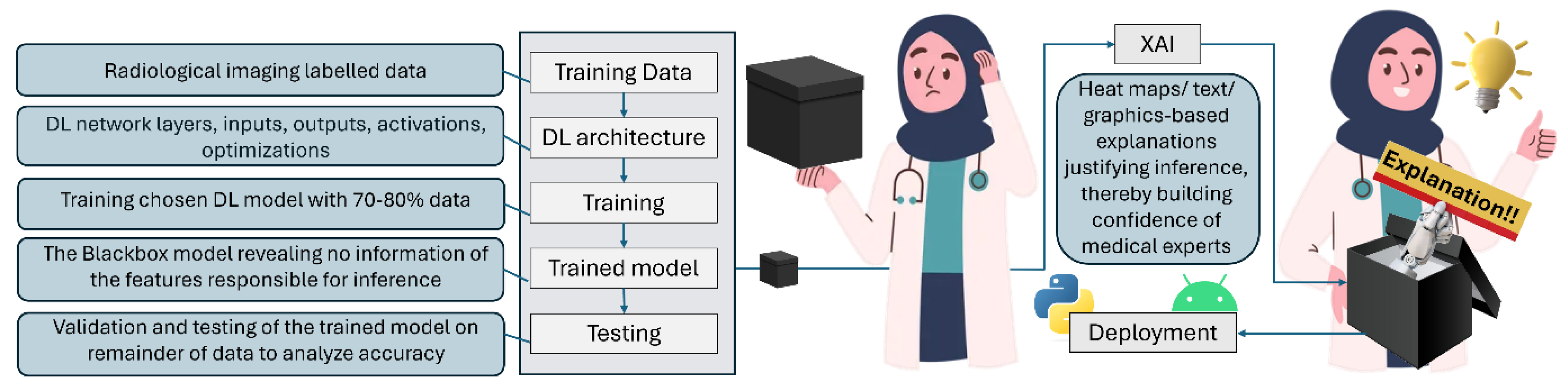

- Black box: Block box model in AI is one whose operations are not visible to the user. Such models arrive at decisions without providing any explanation as to how they were reached. Such models lack transparency, and therefore are frowned upon, and not trusted in applications like diagnostic medicine, where precious human lives are on the line.

1.3. Unravelling the Mystery!

1.4. XAI Methods and Frameworks

1.5. Would XAI Be the Matchmaker~

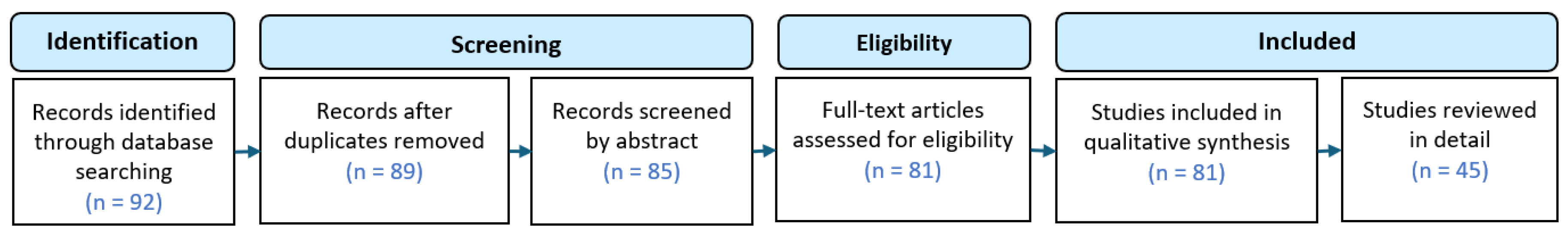

1.6. Study Selection

- Year of study

- Diseases researched

- Modalities employed

- AI techniques used

- Accuracy of developed systems

- Algorithms used for Explainability

- Datasets used

2. AI and XAI in CAD of Neurological Disorders

3. The Challenges Ahead

3.1. Limited Training Datasets and Generalizability Issues

3.2. Current Focus Mostly on Optimizing Performance of CAD Tools

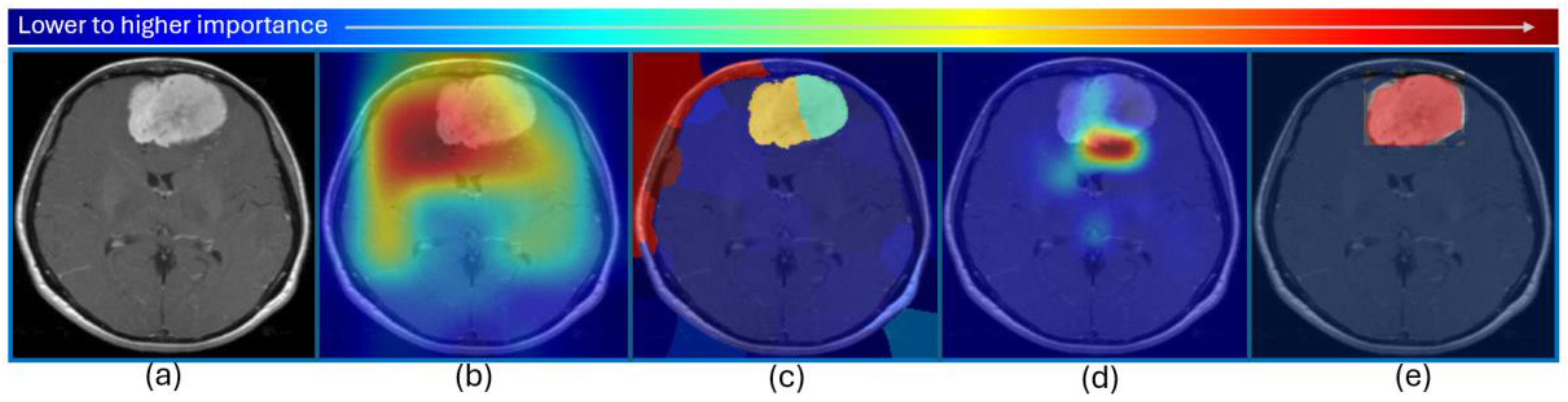

3.3. Absence of Ground Truth Data for Explainability

3.4. Focus on Single Modality

3.5. Only Visual Explanations Sufficient~

3.6. How to Judge XAI Performance~

3.7. More Doctors Onboard, Please!

3.8. User Awareness

3.9. Security, Safety, Legal, and Ethical Challenges

3.10. Let There Be Symbiosis!

4. Conclusions

- The integration of explainability in such CAD tools will surely increase the confidence of medical experts, but the current modes of explanations might not be enough. More thorough and human professor-like explanations are what the healthcare professionals are looking for.

- The quantitative and qualitative evaluation of such XAI schemes requires a lot of attention. The absence of ground truth data for explainability is also one of the major concerns at the moment which needs special attention, along with legal, ethical, safety, and security issues.

- Nothing of this can be materialized without getting both medical professionals and scientists onboard in an absolute symbiosis for working towards this cause.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. WHO - The top 10 causes of death. 24 Maggio, 2018. Available online: http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death (accessed on 4 November 2023).

- M. Camacho et al.. Explainable classification of Parkinson’s disease using deep learning trained on a large multi-center database of T1-weighted MRI datasets. NeuroImage Clin. 2023, 38, 103405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- L. M. Duamwan and J. J. Bird. Explainable AI for Medical Image Processing: A Study on MRI in Alzheimer’s Disease. <i>ACM Int. Conf. Proceeding Ser.</i>, pp. L. M. Duamwan and J. J. Bird. Explainable AI for Medical Image Processing: A Study on MRI in Alzheimer’s Disease. ACM Int. Conf. Proceeding Ser. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih, I. B. Galazzo, F. Cruciani, L. Brusini, and P. Radeva. Investigating Explainable Artificial Intelligence for Mri-Based Classification of Dementia: a New Stability Criterion for Explainable Methods. Proc. - Int. Conf. Image Process. ICIP, pp. 4003– 4007, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Sidulova, N. M. Sidulova, N. Nehme, and C. H. Park. Towards Explainable Image Analysis for Alzheimer’s Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment Diagnosis. Proc. - Appl. Imag. Pattern Recognit. Work. 2021; 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Tjoa and C. Guan. A Survey on Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): Toward Medical XAI. IEEE Trans. Neural Networks Learn. Syst. 2021, 32, 4793–4813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- T. Tomson. Excess mortality in epilepsy in developing countries. Lancet Neurol. 2006, 5, 804–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. Avants, C. L. Epstein, M. Grossman, and J. C. Gee. Symmetric diffeomorphic image registration with cross-correlation: Evaluating automated labeling of elderly and neurodegenerative brain. Med. Image Anal. 2008, 12, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Nemoto et al.. Differentiating Dementia with Lewy Bodies and Alzheimer’s Disease by Deep Learning to Structural MRI. J. Neuroimaging 2021, 31, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. V. Farahani, K. Fiok, B. Lahijanian, W. Karwowski, and P. K. Douglas. Explainable AI: A review of applications to neuroimaging data. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Yang, Q. Ye, and J. Xia. Unbox the black-box for the medical explainable AI via multi-modal and multi-centre data fusion: A mini-review, two showcases and beyond. Inf. Fusion 2022, 77, 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. A. Zeineldin et al.. Explainability of deep neural networks for MRI analysis of brain tumors. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2022, 17, 1673–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Odusami, R. Maskeliūnas, R. Damaševičius, and S. Misra. Explainable Deep-Learning-Based Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease Using Multimodal Input Fusion of PET and MRI Images. J. Med. Biol. Eng. 2023, 43, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. M. Fellous, G. Sapiro, A. Rossi, H. Mayberg, and M. Ferrante. Explainable Artificial Intelligence for Neuroscience: Behavioral Neurostimulation. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Herent, S. Jegou, G. Wainrib, and T. Clozel. Brain age prediction of healthy subjects on anatomic MRI with deep learning : going beyond with an ‘explainable AI’ mindset. bioRxiv, p. 41 3302, 2018, [Online] Available: https://wwwbiorxivorg/content/101101/413302v1%0Ahttps://wwwbiorxivorg/content/101101/413302v1abstract. [Google Scholar]

- N. Bibi, J. N. Bibi, J. Courtney, and K. M. Curran. Explainable Deep Learning for Neuroimaging : A Generalizable Approach for Differential Diagnosis of Brain Diseases. pp. 1–12, 2024.

- J. Qian, H. Li, J. Wang, and L. He. Recent Advances in Explainable Artificial Intelligence for Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Diagnostics 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Nazari et al.. Explainable AI to improve acceptance of convolutional neural networks for automatic classification of dopamine transporter SPECT in the diagnosis of clinically uncertain parkinsonian syndromes. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2022, 49, 1176–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Shojaei, M. Saniee Abadeh, and Z. Momeni. An evolutionary explainable deep learning approach for Alzheimer’s MRI classification. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 220, 119709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Nazir, D. M. Dickson, and M. U. Akram. Survey of explainable artificial intelligence techniques for biomedical imaging with deep neural networks. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 156, 106668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. M. Górriz et al.. Computational approaches to Explainable Artificial Intelligence: Advances in theory, applications and trends. Inf. Fusion 2023, 100, 101945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taşcı. Attention Deep Feature Extraction from Brain MRIs in Explainable Mode: DGXAINet. Diagnostics 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boscolo, Galazzo; et al. . Explainable Artificial Intelligence for Magnetic Resonance Imaging Aging Brainprints: Grounds and challenges. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2022, 39, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. A. Zeineldin et al.. Explainable hybrid vision transformers and convolutional network for multimodal glioma segmentation in brain MRI. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Champendal, H. Müller, J. O. Prior, and C. S. dos Reis. A scoping review of interpretability and explainability concerning artificial intelligence methods in medical imaging. Eur. J. Radiol. 2023, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Borys et al.. Explainable AI in medical imaging: An overview for clinical practitioners – Beyond saliency-based XAI approaches. Eur. J. Radiol. 2023, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Jin, X. Li, M. Fatehi, and G. Hamarneh. Guidelines and evaluation of clinical explainable AI in medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 2023, 84, 102684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. H. M. van der Velden, H. J. Kuijf, K. G. A. Gilhuijs, and M. A. Viergever. Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) in deep learning-based medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 2022, 79, 102470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V. Viswan, N. V. Viswan, N. Shaffi, M. Mahmud, K. Subramanian, and F. Hajamohideen, Explainable Artificial Intelligence in Alzheimer’s Disease Classification: A Systematic Review, vol. 16, no. 1. Springer US, 2024.

- K. Borys et al.. Explainable AI in medical imaging: An overview for clinical practitioners - Saliency-based XAI approaches. Eur. J. Radiol. 2023, 162, 110787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Jin, X. Li, and G. Hamarneh. Evaluating Explainable AI on a Multi-Modal Medical Imaging Task: Can Existing Algorithms Fulfill Clinical Requirements~. Proc. 36th AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. AAAI 2022 2022, 36, 11945–11953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzinger, C. Biemann, C. S. Pattichis, and D. B. Kell. What do we need to build explainable AI systems for the medical domain~. no. Ml, pp. 1–28, 2017, [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/1712. 0992. [Google Scholar]

- S. Jahan et al.. Explainable AI-based Alzheimer’s prediction and management using multimodal data. PLoS One 2023, 18, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navoneel Chakrabarty. Brain MRI Images for Brain Tumor Detection. 2018. https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/navoneel/brain-mri-images-for-brain-tumor-detection (accessed Nov. 17, 2024).

- M. Esmaeili, R. Vettukattil, H. Banitalebi, N. R. Krogh, and J. T. Geitung. Explainable artificial intelligence for human-machine interaction in brain tumor localization. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Liang et al.. Magnetic resonance imaging sequence identification using a metadata learning approach. Front. Neuroinform. 2021, 15, 622951. [Google Scholar]

- Hoopes, J. S. Mora, A. V Dalca, B. Fischl, and M. Hoffmann. SynthStrip: skull-stripping for any brain image. Neuroimage 2022, 260, 119474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Hashemi, M. Akhbari, and C. Jutten. Delve into multiple sclerosis (MS) lesion exploration: a modified attention U-net for MS lesion segmentation in brain MRI. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 145, 105402. [Google Scholar]

- Z. Liu et al.. Deep learning based brain tumor segmentation: a survey. Complex Intell. Syst. 2023, 9, 1001–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. S. A. Ali, K. S. S. A. Ali, K. Memon, N. Yahya, K. A. Sattar, and S. El Ferik. Deep Learning Framework-Based Automated Multi-class Diagnosis for Neurological Disorders. in 2023 7th International Conference on Automation, Control and Robots (ICACR), 2023, pp. 87–91.

- L. Alzubaidi et al.. Review of deep learning: concepts, CNN architectures, challenges, applications, future directions. J. big Data 2021, 8, 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- R. ElSebely, B. Abdullah, A. A. Salem, and A. H. Yousef. Multiple Sclerosis Lesion Segmentation Using Ensemble Machine Learning. Saudi J Eng Technol 2020, 5, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. S. Vang et al.. SynergyNet: a fusion framework for multiple sclerosis brain MRI segmentation with local refinement. in 2020 IEEE 17th international symposium on biomedical imaging (ISBI), 2020, pp. 131–135.

- Zeng, L. Gu, Z. Liu, and S. Zhao. Review of deep learning approaches for the segmentation of multiple sclerosis lesions on brain MRI. Front. Neuroinform. 2020, 14, 610967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. R. van der Voort, M. Smits, S. Klein, and A. D. N. Initiative. DeepDicomSort: an automatic sorting algorithm for brain magnetic resonance imaging data. Neuroinformatics 2021, 19, 159–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Pizarro et al.. Using Deep Learning Algorithms to Automatically Identify the Brain MRI Contrast: Implications for Managing Large Databases. Neuroinformatics 2019, 17, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Gao, G. Luo, R. Ding, B. Yang, and H. Sun. A Lightweight Deep Learning Framework for Automatic MRI Data Sorting and Artifacts Detection. J. Med. Syst. 2023, 47, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Ranjbar et al.. A Deep Convolutional Neural Network for Annotation of Magnetic Resonance Imaging Sequence Type. J. Digit. Imaging 2020, 33, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. P. V. de Mello et al.. Deep learning-based type identification of volumetric mri sequences. in 2020 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), 2021, pp. 1–8.

- M. Khuhed. NIVE: NeuroImaging Volumetric Extractor, A High-performance Skull-stripping Tool. 2023. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/129574-nive (accessed on 17 January 2024).

- Bruscolini, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. . Diagnosis and management of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders - An update. Autoimmun. Rev. 2018, 17, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. M. Baghbanian, N. Asgari, M. A. Sahraian, and A. N. Moghadasi. A comparison of pediatric and adult neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders: A review of clinical manifestation, diagnosis, and treatment. J. Neurol. Sci. 2018, 388, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thouvenot. Multiple sclerosis biomarkers: helping the diagnosis~. Rev. Neurol. (Paris). 2018, 174, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- B. Xin, L. B. Xin, L. Zhang, J. Huang, J. Lu, and X. Wang. Multi-level Topological Analysis Framework for Multifocal Diseases. 16th IEEE Int. Conf. Control. Autom. Robot. Vision, ICARCV 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. R. Nayak, R. Dash, and B. Majhi. Automated diagnosis of multi-class brain abnormalities using MRI images: a deep convolutional neural network based method. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2020, 138, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. D. Rudie et al.. Subspecialty-level deep gray matter differential diagnoses with deep learning and Bayesian networks on clinical brain MRI: a pilot study. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 2020, 2, e190146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. M. Krishnammal and S. S. Raja. Convolutional neural network based image classification and detection of abnormalities in mri brain images. in 2019 International Conference on Communication and Signal Processing (ICCSP), 2019, pp. 548–553.

- S. S. Raja. Deep learning based image classification and abnormalities analysis of MRI brain images. in 2019 TEQIP III Sponsored International Conference on Microwave Integrated Circuits, Photonics and Wireless Networks (IMICPW), 2019, pp. 427–431.

- Mangeat, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. . Machine learning and multiparametric brain MRI to differentiate hereditary diffuse leukodystrophy with spheroids from multiple sclerosis. J. Neuroimaging 2020, 30, 674–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Khan, W. A. Khan, W. Jue, M. Mushtaq, and M. U. Mushtaq. Brain tumor classification in MRI image using convolutional neural network. Math. Biosci. Eng.

- Singh, M. Vadera, L. Samavedham, and E. C.-H. Lim. Machine learning-based framework for multi-class diagnosis of neurodegenerative diseases: a study on Parkinson’s disease. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2016, 49, 990–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalbkhani, M. G. Shayesteh, and B. Zali-Vargahan. Robust algorithm for brain magnetic resonance image (MRI) classification based on GARCH variances series. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2013, 8, 909–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V. Bordin, D. V. Bordin, D. Coluzzi, M. W. Rivolta, and G. Baselli. Explainable AI Points to White Matter Hyperintensities for Alzheimer’s Disease Identification: a Preliminary Study. Proc. Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. EMBS, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Yu, W. Xiang, J. Fang, Y. P. Phoebe Chen, and R. Zhu. A novel explainable neural network for Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis. Pattern Recognit. 2022, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Sudar, P. M. Sudar, P. Nagaraj, S. Nithisaa, R. Aishwarya, M. Aakash, and S. I. Lakshmi. Alzheimer’s Disease Analysis using Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI). Int. Conf. Sustain. Comput. Data Commun. Syst. ICSCDS 2022 - Proc. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang, L. Han, W. Zhu, L. Sun, and D. Zhang. An Explainable 3D Residual Self-Attention Deep Neural Network for Joint Atrophy Localization and Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnosis Using Structural MRI. IEEE J. Biomed. Heal. Informatics 2022, 26, 5289–5297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Achilleos, S. Leandrou, N. Prentzas, P. A. Kyriacou, A. C. Kakas, and C. S. Pattichis. Extracting Explainable Assessments of Alzheimer’s disease via Machine Learning on brain MRI imaging data. Proc. - IEEE 20th Int. Conf. Bioinforma. Bioeng. BIBE 2020, pp. 1036– 1041, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Nigri, N. E. Nigri, N. Ziviani, F. Cappabianco, A. Antunes, and A. Veloso. Explainable Deep CNNs for MRI-Based Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Proc. Int. Jt. Conf. Neural Networks. [CrossRef]

- Essemlali, E. St-Onge, M. Descoteaux, and P. M. Jodoin. Understanding Alzheimer disease’s structural connectivity through explainable AI. Proc. Mach. Learn. Res. 2020, 121, 217–229. [Google Scholar]

- F. Ahmed, M. Asif, M. Saleem, U. F. Mushtaq, and M. Imran. Identification and Prediction of Brain Tumor Using VGG-16 Empowered with Explainable Artificial Intelligence. Int. J. Comput. Innov. Sci. 2023, 2, 24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Gaur, M. Bhandari, T. Razdan, S. Mallik, and Z. Zhao. Explanation-Driven Deep Learning Model for Prediction of Brain Tumour Status Using MRI Image Data. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eder, E. Moser, A. Holzinger, C. Jean-Quartier, and F. Jeanquartier. Interpretable Machine Learning with Brain Image and Survival Data. BioMedInformatics 2022, 2, 492–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Haque, M. M. Hassan, A. K. Bairagi, and S. M. Shariful Islam. NeuroNet19: an explainable deep neural network model for the classification of brain tumors using magnetic resonance imaging data. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Hossain, A. S. Hossain, A. Chakrabarty, T. R. Gadekallu, M. Alazab, and M. J. Piran. Vision Transformers, Ensemble Model, and Transfer Learning Leveraging Explainable AI for Brain Tumor Detection and Classification. IEEE J. Biomed. Heal. Informatics, 14. [CrossRef]

- H. Benyamina, A. S. H. Benyamina, A. S. Mubarak, and F. Al-Turjman. Explainable Convolutional Neural Network for Brain Tumor Classification via MRI Images. Proc. - 2022 Int. Conf. Artif. Intell. Things Crowdsensing, AIoTCs 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Kamal, A. Northcote, L. Chowdhury, N. Dey, R. G. Crespo, and E. Herrera-Viedma. Alzheimer’s Patient Analysis Using Image and Gene Expression Data and Explainable-AI to Present Associated Genes. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. El-Sappagh, J. M. Alonso, S. M. R. Islam, A. M. Sultan, and K. S. Kwak. A multilayer multimodal detection and prediction model based on explainable artificial intelligence for Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R. Manikandan, U. Kose, D. Gupta, and S. C. Satapathy. Doctor’s dilemma: Evaluating an explainable subtractive spatial lightweight convolutional neural network for brain tumor diagnosis. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. 2021, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- .R. C. Poonia and H. A. Al-Alshaikh. Ensemble approach of transfer learning and vision transformer leveraging explainable AI for disease diagnosis: An advancement towards smart healthcare 5.0. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 179, 108874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Veetil, D. E. Chowdary, P. N. Chowdary, V. Sowmya, and E. A. Gopalakrishnan. An analysis of data leakage and generalizability in MRI based classification of Parkinson’s Disease using explainable 2D Convolutional Neural Networks. Digit. Signal Process. A Rev. J. 2024, 147, 104407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- .G. Lozupone, A. .G. Lozupone, A. Bria, F. Fontanella, and C. De Stefano. AXIAL: Attention-based eXplainability for Interpretable Alzheimer’s Localized Diagnosis using 2D CNNs on 3D MRI brain scans. no. Dl, 2024, [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2407.02418.

- Deshmukh, N. Kallivalappil, K. D’Souza, and C. Kadam. AL-XAI-MERS: Unveiling Alzheimer’s Mysteries with Explainable AI. 2nd Int. Conf. Emerg. Trends Inf. Technol. Eng. ic-ETITE 2024, 2024; 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- .S. Tehsin, I. M. Nasir, R. Damaševičius, and R. Maskeliūnas. DaSAM: Disease and Spatial Attention Module-Based Explainable Model for Brain Tumor Detection. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2024, 8, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. T. Padmapriya and M. S. G. Devi. Computer-Aided Diagnostic System for Brain Tumor Classification using Explainable AI. 2024 IEEE Int. Conf. Interdiscip. Approaches Technol. Manag. Soc. Innov. IATMSI 2024, 2024; 6. [CrossRef]

- K. Thiruvenkadam, V. K. Thiruvenkadam, V. Ravindran, and A. Thiyagarajan. Deep Learning with XAI based Multi-Modal MRI Brain Tumor Image Analysis using Image Fusion Techniques. 2024 Int. Conf. Trends Quantum Comput. Emerg. Bus. Technol. 2024; 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Mahmud, K. Barua, S. U. Habiba, N. Sharmen, M. S. Hossain, and K. Andersson. An Explainable AI Paradigm for Alzheimer’s Diagnosis Using Deep Transfer Learning. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palkar, C. C. Dias, K. Chadaga, and N. Sampathila. Empowering Glioma Prognosis With Transparent Machine Learning and Interpretative Insights Using Explainable AI. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 31697–31718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- .Narayankar and V., P. Baligar. Explainability of Brain Tumor Classification Based on Region. Int. Conf. Emerg. Technol. Comput. Sci. Interdiscip. Appl. ICETCS 2024, 2024; 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Mansouri, A. D. Mansouri, A. Echtioui, R. Khemakhem, and A. Ben Hamida. Explainable AI Framework for Alzheimer’s Diagnosis Using Convolutional Neural Networks. 7th IEEE Int. Conf. Adv. Technol. Signal Image Process. ATSIP 2024, 2024; 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Nhlapho, M. W. Nhlapho, M. Atemkeng, Y. Brima, and J. C. Ndogmo. Bridging the Gap: Exploring Interpretability in Deep Learning Models for Brain Tumor Detection and Diagnosis from MRI Images. Inf. 2024; 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. M. M, M. T. R, V. K. V, and S. Guluwadi. Enhancing brain tumor detection in MRI images through explainable AI using Grad-CAM with Resnet 50. BMC Med. Imaging 2024, 24, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V. Adarsh, G. R. Gangadharan, U. Fiore, and P. Zanetti. Multimodal classification of Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment using custom MKSCDDL kernel over CNN with transparent decision-making for explainable diagnosis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, K. Hasan, and M. S. Hossain. XAI-Empowered MRI Analysis for Consumer Electronic Health. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2024; 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I. Korda et al.. Identification of texture MRI brain abnormalities on first-episode psychosis and clinical high-risk subjects using explainable artificial intelligence. Transl. Psychiatry, 2022; 1. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang, L. X. Zhang, L. Han, W. Zhu, L. Sun, and D. Zhang. An Explainable 3D Residual Self-Attention Deep Neural Network For Joint Atrophy Localization and Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnosis using Structural MRI. IEEE J. Biomed. Heal. Informatics, 2021; 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Nazari et al.. Data-driven identification of diagnostically useful extrastriatal signal in dopamine transporter SPECT using explainable AI. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. . Explainable Deep Learning for Personalized Age Prediction With Brain Morphology. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- .M. S. Kamal, A. .M. S. Kamal, A. Northcote, L. Chowdhury, N. Dey, R. G. Crespo, and E. Herrera-Viedma. Alzheimer’s Patient Analysis Using Image and Gene Expression Data and Explainable-AI to Present Associated Genes. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. . A new scheme for the assessment of the robustness of explainable methods applied to brain age estimation. Proc. - IEEE Symp. Comput. Med. Syst. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- .H. Tatekawa et al.. Imaging differences between neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders and multiple sclerosis: a multi-institutional study in Japan. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2018, 39, 1239–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Miki. Magnetic resonance imaging diagnosis of demyelinating diseases: an update. Clin. Exp. Neuroimmunol. 2019, 10, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiala, D. Rotstein, and M. D. Pasic. Pathobiology, diagnosis, and current biomarkers in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. J. Appl. Lab. Med. 2022, 7, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Etemadifar, M. M. Etemadifar, M. Norouzi, S.-A. Alaei, R. Karimi, and M. Salari. The diagnostic performance of AI-based algorithms to discriminate between NMOSD and MS using MRI features: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 5682. [Google Scholar]

- S. Tatli et al.. Transfer-transfer model with MSNet: An automated accurate multiple sclerosis and myelitis detection system. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 236, 121314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Kuchling and F. Paul. Visualizing the central nervous system: imaging tools for multiple sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 450. [Google Scholar]

- Bruscolini, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. . Diagnosis and management of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders-An update. Autoimmun. Rev. 2018, 17, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. T. Duong et al.. Convolutional neural network for automated FLAIR lesion segmentation on clinical brain MR imaging. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2019, 40, 1282–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. -U. Lee, H.-J. Kim, J.-H. Choi, J.-Y. Choi, and J.-S. Kim. Comparison of ocular motor findings between neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder and multiple sclerosis involving the brainstem and cerebellum. The Cerebellum 2019, 18, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder and C., B. Veilleux. Smart health and cybersecurity in the era of artificial intelligence. Comput. Commun.

- Chakraborty, S. M. Nagarajan, G. G. Devarajan, T. V Ramana, and R. Mohanty. Intelligent ai-based healthcare cyber security system using multi-source transfer learning method. ACM Trans. Sens. Networks.

- J. R. Saura, D. Ribeiro-Soriano, and D. Palacios-Marqués. Setting privacy ‘by default’ in social IoT: Theorizing the challenges and directions in Big Data Research. Big Data Res. 2021, 25, 100245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Chen et al.. Information Security and Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Diagnosis in an Internet of Medical Thing System (IoMTS). IEEE Access 2024, 12, 9757–9775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Damar, A. Özen, and A. Yılmaz. Cybersecurity in The Health Sector in The Reality of Artificial Intelligence, And Information Security Conceptually. J. AI 2024, 8, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Yanase and E. Triantaphyllou. The seven key challenges for the future of computer-aided diagnosis in medicine. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2019, 129, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Biasin, E. E. Biasin, E. Kamenjašević, and K. R. Ludvigsen. Cybersecurity of AI medical devices: risks, legislation, and challenges. Res. Handb. Heal. AI Law, 2024; 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. M. Rai, D. Tsoy, and Y. Daineko. MetaHospital: implementing robust data security measures for an AI-driven medical diagnosis system. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 241, 476–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Pathology | Modality | Technology | Accuracy | XAI | Dataset |

| [79] 2024 | AD | MRI | Transfer Learning (TL), Vision Transformer (ViT) | TL 58%, TL ViT Ensemble 96% |

- | ADNI |

| [80] 2024 | PD | MRI T1w | 12 pre-trained CNN models | VGG19 best performance | Grad-CAM | PPMI (213 PD, 213 Normal Control (NC)), NEUROCRON (27 PD, 16 NC) and Tao Wu (18 PD, 18 NC) |

| [81] 2024 | AD, progressive Mild Cognitive Impairment (pMCI), stable MCI (sMCI) | MRI | 2D-CNN, TL | AD-CN 86.5%, sMCI-pMCI 72.5% |

3D attention map | ADNI (AD 191, pMCI 121, sMCI 110, NC 204 subjects) |

| [82] 2024 | Very mild dementia, moderate dementia, mild dementia, non demented | MRI | DenseNet121, MobileNetV2 | MobileNetV2 93%, DenseNet121 88% | LIME | OASIS |

| [83] 2024 | Brain tumor | MRI | Disease and Spatial Attention Model (DaSAM) | Up to 99% | - | Figshare and Kaggle datasets |

| [84] 2024 | Brain tumor | MRI | VGG16 | 99.4% | Grad-CAM | Kaggle and BraTS 2021 dataset |

| [85] 2024 | Brain tumor | MRI FLAIR, T1, T2w | CNN | 98.97% | - | 3300 images from BraTS dataset |

| [86] 2024 | AD | MRI | Ensemble-1 (VGG16 and VGG19) and Ensemble-2 (DenseNet169 and DenseNet201) | up to 96% | Saliency maps and Grad-CAM | Kaggle and OASIS-2 (896 MRIs for mild dementia, 64 moderate dementia, 3200 non-dementia, and 2240 very mild dementia) |

| [87] 2024 | Glioma | 23 Clinical and Molecular/ mutation factors | RF, decision trees (DT), logistic regression (LR), K-nearest neighbors (KNN), Adaboost, Support Vector Machine (SVM), Catboost, Light Gradient-Boosting Machine (LGBM) classifier, Xgboost, CNN | 88% for Xgboost | SHAP, Eli5, LIME, and QLattice | Glioma Grading Clinical and Mutation Features Dataset – 352 Glioblastoma Multiforme (GBM), 487 LGG patients |

| [88] 2024 | Glioma, Meningioma, Pituitary tumor | MRI | CNN | 80% | LIME, SHAP, Integrated Gradients (IG), and Grad-CAM | 7043 images from Figshare, SARTAJ, Br35H datasets |

| [89] 2024 | AD | MRI | CNN | Real MRI 88.98%, Real + Synthetic MRIs 97.50% | Grad-CAM | Kaggle - 896 MRIs for Mild Impairment, 64 Moderate Impairment, 3200 No Impairment, 2240 Very Mild Impairment. Synthetic images generated using Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Network with Gradient Penalty (WGAN-GP) |

| [90] 2024 | Brain tumor | MRI T1w | 10 TL frameworks | Up to 98% for EfficientNetB0 | Grad-CAM, Grad-CAM++, IG, and Saliency Mapping | Kaggle - 926 MRI images of glioma tumors, 500 with no tumors, 901 pituitary tumors, and 937 meningioma tumors |

| [91] 2024 | Brain tumor | MRI | ResNet50 | 98.52% | Grad-CAM | Kaggle |

| [92] 2024 | AD, MCI | MRI | CNNs with a Multi-feature Kernel Supervised within-class-similar Discriminative Dictionary Learning (MKSCDDL) | 98.27% |

Saliency maps, Grad-CAM, Score-CAM, Grad-CAM++ | ADNI |

| [93] 2024 | Brain tumor | MRI | Physics-informed deep learning (PIDL) | 96% | LIME, Grad-CAM | Kaggle - glioma 1621 images, meningioma 1645, pituitary tumors 1775, and non-tumorous scans 2000 images |

| [73] 2024 | Brain tumors four classes: glioma, meningioma, no tumor, and pituitary tumors | MRI |

VGG19 with Inverted Pyramid Pooling Module (iPPM) | 99.3% | LIME |

Kaggle - 7023 images |

| [24] 2024 | Gliomas segmentation | 3D pre-operative multimodal MRI scans including T1w, T1Gd, T2w, and FLAIR | Hybrid vision Transformers and CNNs | Dice up to 0.88 |

Grad-CAM - TransXAI, post-hoc surgeon understandable heatmaps | BraTS 2019 challenge dataset including 335 training and 125 validation subjects |

| [16] 2024 | Types of brain tumors, MS | MRI | DenseNet121 | 99% |

Grad-CAM | Glioma, Meningioma, Pituitary tumors, from Figshare, the SARTAJ dataset and Br35H: Brain Tumor Detection 2020 The MS dataset from study by the Ozal University Medical Faculty, 72 MS patients and 59 healthy controls (HC) |

| [2] 2023 | PD | MRI T1w | CNN |

79.3% |

Saliency maps | 1,024 PD patients and 1,017 age and sex matched HC from 13 different studies |

| [33] 2023 | AD, cognitively normal, non-Alzheimer’s dementia, uncertain dementia, and others | Clinical, Psychological, and MRI segmentation data | RF, LR, DT, MLP, KNN, GB, AdaB, SVM, and Naïve Bayes (NB) | 98.81% | SHAP | OASIS-3, ADRC clinical data, Number of NC, AD, Other dementia/ Non-AD, Uncertain, and Others are 4476, 1058, 142, 505, and 43, respectively |

| [13] 2023 | AD | PET and MRI | Modified Resnet18 | 73.90% | - | ADNI - 412 MRIs and 412 PETs |

| [70] 2023 | Brain tumor | MRI | VGG16 | 97.33% |

LRP | 1500 normal brain MRI images and 1500 tumor brain MRI images - Kaggle |

| [3] 2023 | Non-dementia, very mild, mild, and moderate | MRI | CNN | 94.96%. | LIME | ADNI |

| [69] 2023 | AD, MCI | DW-MRI | CNN | 78% for NC-MCI (45 test samples), 91% for NC-AD (45 test samples) and 81% MCI-AD (49 test samples) | Saliency map visualization | ADNI2 and ADNI-Go - 152 NC, 181 MCI and 147 AD |

| [22] 2023 | Brain tumor | MRI | DenseNet201, iterative neighborhood component (INCA) feature selector, SVM | 98.65% and 99.97%, for Datasets I and II | Grad-CAM |

Four-class Kaggle brain tumor dataset and the three-class Figshare brain tumor dataset |

| [19] 2023 | AD | MRI | 3D CNN | 87% | Genetic algorithm-based Occlusion Map method with a set of Backpropagation-based explainability methods | ADNI - 145 samples (74 AD and 71 HC) |

| [74] 2023 | Brain tumor | MRI | VGG16, InceptionV3, VGG19, ResNet50, InceptionResNetV2, Xception, and IVX16 | 95.11%, 93.88%, 94.19%, 93.88%, 93.58%, 94.5%, and 96.94% for VGG16, InceptionV3, VGG19, ResNet50, InceptionResNetV2, Xception, and IVX16, respectively | LIME | Kaggle - 3264 images |

| [12] 2022 | Brain tumor (classification and segmentation) | MRI | ResNet50 for classification, encoder–decoder neural network for segmentation | - | Vanilla gradient, guided backpropagation, integrated gradients, guided integrated gradients, SmoothGrad, Grad-CAM, and guided Grad-CAM visualizations | BraTS challenges 2019 (259 cases of HGG and 76 cases of LGG) and 2021 (1251 MRI images with ground truth annotations) |

| [4] 2022 | AD, EMCI, MCI, LMCI | MRI T1w | DT, LGBM, LR, RF and Support Vector Classifier (SVC) | - | SHAP | ADNI3 - 475 subjects, including 300 controls (HC, 254 Cognitively Normal and 46 Significant Memory Concern) and 175 patients with dementia (comprising 70 early MCI, 55 MCI, 34 Late MCI and 16 AD) |

| [71] 2022 | Brain tumors (meningioma, glioma, and pituitary) | MRI | CNN | 94.64% | LIME, SHAP | 2,870 images from Kaggle |

| [63] 2022 | Early-stage AD dementia | MRI | EfficientNet-B0 | AUC: 0.82 | Occlusion Sensitivity | 251 from OASIS-3 |

| [64] 2022 | AD | MRI T1w | MAXNet with Dual Attention Module (DAM) and Multi-resolution Fusion Module (MFM) | 95.4% | High-resolution Activation Mapping (HAM), and a Prediction-basis Creation and Retrieval (PCR) | ADNI - 826 cognitively normal individuals and 422 Alzheimer’s patients |

| [72] 2022 | Brain tumors (survival rate prediction) | MRI T1w, T1ce, T2w, FLAIR | CNN | 71% | SHAP | 235 patients from BraTS 2020 |

| [75] 2022 | Brain tumor | MRI | VGG16 | - | SHAP | Kaggle |

| [65] 2022 | AD: non-demented, very mild demented, mild demented and moderate demented | MRI | VGG16 | 78.12% |

LRP | 6400 images with 4 classes |

| [18] 2022 | PD | Dopamine transporter (DAT) SPECT | CNN | 95.8% | LRP | 1296 clinical DAT-SPECT as “normal” or “reduced” from the PACS of the Department of Nuclear Medicine of the University Medical Center Hamburg Eppendorf |

| [94] 2022 | Psychosis | MRI | Neural network-based classifier | Above 72% | LRP | 77 first-episode psychosis (FEP) patients, 58 clinical high-risk subjects with no later transition to psychosis (CHR_NT), 15 clinical high-risk subjects with later transition (CHR_T), and 44 HC from the early detection of psychosis project (FePsy) at the Department of Psychiatry, University of Basel, Switzerland |

| [95] 2021 | AD vs. NC and pMCI vs. sMCI | MRI | 3D Residual Attention Deep Neural Network (3D ResAttNet) | 91% AD vs NC, 82% pMCI vs sMCI |

Grad-CAM |

1407 subjects from ADNI-1, ADNI-2 and ADNI-3 datasets |

| [96] 2021 | PD | DAT SPECT | 3D CNN | 97.0% | LRP | 1306 123I-FP-CIT-SPECT, PACS of the Department of Nuclear Medicine of the University Medical Center Hamburg Eppendorf |

| [97] 2021 | Age Prediction | MRI T1w | DNN | - | SHAP and LIME | ABIDE I - 378 T1w MRI |

| [5] 2021 | AD, MCI | EEG | SVM, ANN, CNN | Up to 96% | LIME | 284 AD, 56 MCI, 100 HC |

| [98] 2021 | AD | MRI and Gene Expression data | CNN, KNN, SVC, Xboost | 97.6% | LIME | Kaggle - 6400 MRI images, gene from the dataset OASIS −3, NCBI database, which contains 104 gene expression data from patients |

| [99] 2021 | Age estimation | Structural MRI (sMRI), Susceptibility Weighted Imaging (SWI) and diffusion MRI (dMRI) | DNN | - | SHAP and LIME | 16394 subjects (7742 male and 8652 female) from UKB United Kingdom Biobank |

| [35] 2021 | Brain tumor lower-grade gliomas and the most aggressive malignancy, glioblastoma (WHO grade IV) |

MRI T2w |

DenseNet121, GoogLeNet, MobileNet | DenseNet-121, GoogLeNet, MobileNet achieved an accuracy of 92.1, 87.3, and 88.9 | Grad-CAM |

TCGA dataset from The Cancer Imaging Archive repositories - 354 subjects - 19,200 and 14,800 slices of brain images with and without tumor lesions |

| [77] 2021 | AD, MCI | 11 modalities – PET, MRI, Cognitive scores, Genetic, CSF, Lab tests data, etc. | RF | 93.95% for AD detection and 87.08% for progression prediction | SHAP - these explanations are represented in natural language form to help physicians understand the predictions | ADNI - 294 cognitively normal, 254 stable MCI, 232 progressive MCI, and 268 AD |

| [68] 2020 | AD | MRI T1w | Variants of AlexNet, VGG16 |

- | Swap Test / Occlusion Test | ADNI Australian Imaging, Biomarker & Lifestyle Flagship Study of Ageing3 (AIBL) - training, validation, and test sets, each of them containing respectively 1,779, 427, and 575 images |

| [67] 2020 | AD | T1w volumetric 3D sagittal magnetization prepared rapid gradient-echo (MPRAGE) scans | DT and RF | Average 91% | Argumentation-based reasoning frame- work | ADNI – NC 144 and AD 69 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).