Background

The landscape of cancer treatment has tremendously evolved and improved, but it still is a significant global health challenge [

1,

2]. The cancer cell progression occurs mainly due to genetic mutations and changes in gene activity (epigenetic alterations), leading to the development of “hallmarks of cancer” [

3,

4]. The immune system evasion and long-lasting inflammation are novel hallmarks and facilitating features of cancer [

3,

4]. Traditional treatment approaches like surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or hormone therapy may either be unavailable or associated with significant toxicity for patients, and it enhances the mortality rate. However, the considerable resurgence and potential of cancer immunotherapy by the approval of autologous cellular immunotherapy for prostate cancer treatment in 2010, named Sipuleucel-T, and Ipilimumab for melanoma treatment [

5,

6,

7,

8]. These breakthroughs have opened new avenues for developing novel generations of therapies that harness the immune system's power to combat cancer. Immuno-oncology harnesses the immune system to target and destroy cancer cells, revolutionizing treatment by leveraging the body's natural defenses for more effective cancer management.

Competent immune responses can eliminate cancerous cells or suppress their phenotypes [

9]. The concept of cancer immunosurveillance, introduced by Paul Ehrlich and expanded by Burnet and Thomas in the 1950s, posits that the immune system identifies and suppresses malignant cells. Cancer arises when immune defenses fail, allowing abnormal cells to proliferate uncontrollably, while lymphocytes play a crucial role in recognizing and eliminating these abnormal cells [

10,

11,

12]. Cancer cells evade immune surveillance by impairing antigen presentation, activating inhibitory pathways, and recruiting immunosuppressive cells [

9,

13]. This suppression of anti-tumor immunity facilitates tumor development, expansion, and metastasis. Cancer cells often exhibit mutations, chromosomal rearrangements, and abnormal protein synthesis, leading to neoantigens that aid immune detection [

14].

Schreiber et al. introduced the concept of cancer immune editing in 2002, highlighting the immune system's dual role as a tumor suppressor and promoter through elimination, equilibration, and escape phases. These stages involve dynamic interactions between tumor cells, immune cells, and the tumor microenvironment (TME) [

15,

16]. Despite neoantigen recognition, the evolving and heterogeneous TME poses challenges for immune responses. Understanding immune infiltration in the TME is vital for improving immunotherapy. While T-cell studies dominate, innate and adaptive immune cells, such as dendritic cells (DCs), macrophages, NK cells, and B cells, influence tumor progression and therapy outcomes [

9]. Innate immune cells, including NK cells, basophils, eosinophils, and phagocytic cells like mast cells, monocytes, neutrophils, macrophages, and dendritic cells, play a vital role in inhibiting tumors through direct killing and initiating adaptive immune responses [

9,

17]. The adaptive immune system, comprising B cells and T lymphocytes, works with innate cells to combat tumors. Persistent cellular stress from DNA damage, protein misfolding, instability, or metabolic abnormalities generate stress signals that activate immune cells. Tumor cell death caused by cytotoxic agents or radiation treatments releases antigens and pro-inflammatory mediators, fostering an immunogenic environment and triggering anti-tumor immunity [

4,

18].

Advancements in cancer therapy stem from discovering immune checkpoints, the success of checkpoint inhibitors, and technologies enabling genetic modification of immune cells. Immunotherapy offers durable responses, often attributed to the immune system's memory, translating into prolonged patient survival [

19]. Strategies to enhance immune responses include tumor antigen vaccination, improving antigen presentation, adoptive cellular therapy (ACT), and utilizing oncolytic viruses (OVs). Additionally, antibodies targeting tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily members provide co-stimulatory signals to enhance T cell activity. Chemotherapeutic agents like cyclophosphamide, antibodies against regulatory T cells (e.g., anti-CD25), and checkpoint inhibitors targeting CTLA-4 and PD-1 are employed to counter immunosuppressive mechanisms [

20].

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) and ACT leverage the immune system to combat cancer. ICIs, such as anti-CTLA-4, anti-PD-1, and anti-PD-L1, disrupt inhibitory checkpoint signals that suppress T cell activity, enabling robust anti-tumor responses [

21,

22]. Checkpoint proteins like CTLA-4, PD-1, and their ligands (e.g., PD-L1) naturally regulate immune intensity to protect normal cells. Tumor cells exploit these pathways to evade immunity, but ICIs block these interactions, reactivating T cells to eliminate cancer cells [

21,

23]. Despite their success, ICIs can cause immune-mediated adverse events (irAEs), such as autoimmune thyroiditis or inflammatory bowel disease, particularly when combined therapies are used [

24].

Evaluating ICI efficacy requires metrics beyond traditional measures like response rates. Landmark analyses, which focus on long-term survival or progression-free survival, better capture their benefits. Emerging tools include assessing tumor-infiltrating T cells, PD-L1 expression, and tumor mutational burden (TMB). High TMB, associated with DNA repair deficiencies such as microsatellite instability, correlates with improved responses to anti-PD-1 therapies, leading to approvals for cancers with high mutation rates [

24,

25]. The unintended effects of ICIs, including grade 3–5 adverse events in up to 60% of cases with combined anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 therapy, underscore the challenges of immune activation [

24]. Nonetheless, their impact on cancer treatment is transformative.

This review outlines the evolution of cancer immunotherapy, from initial vaccine efforts to its modern application, emphasizing immune checkpoint modulation and its challenges. It concludes with insights into immunotherapy’s risks, benefits, and future directions.

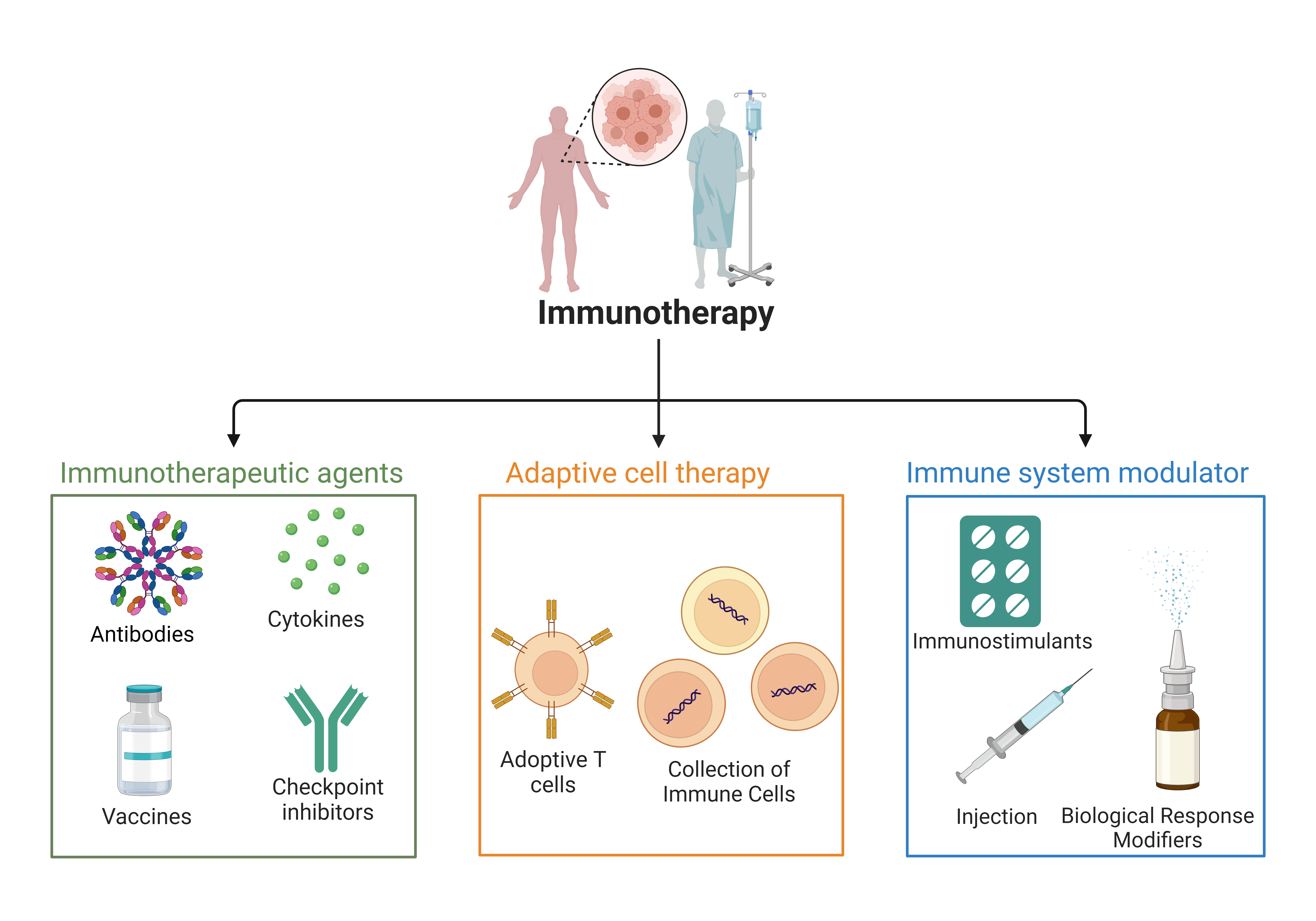

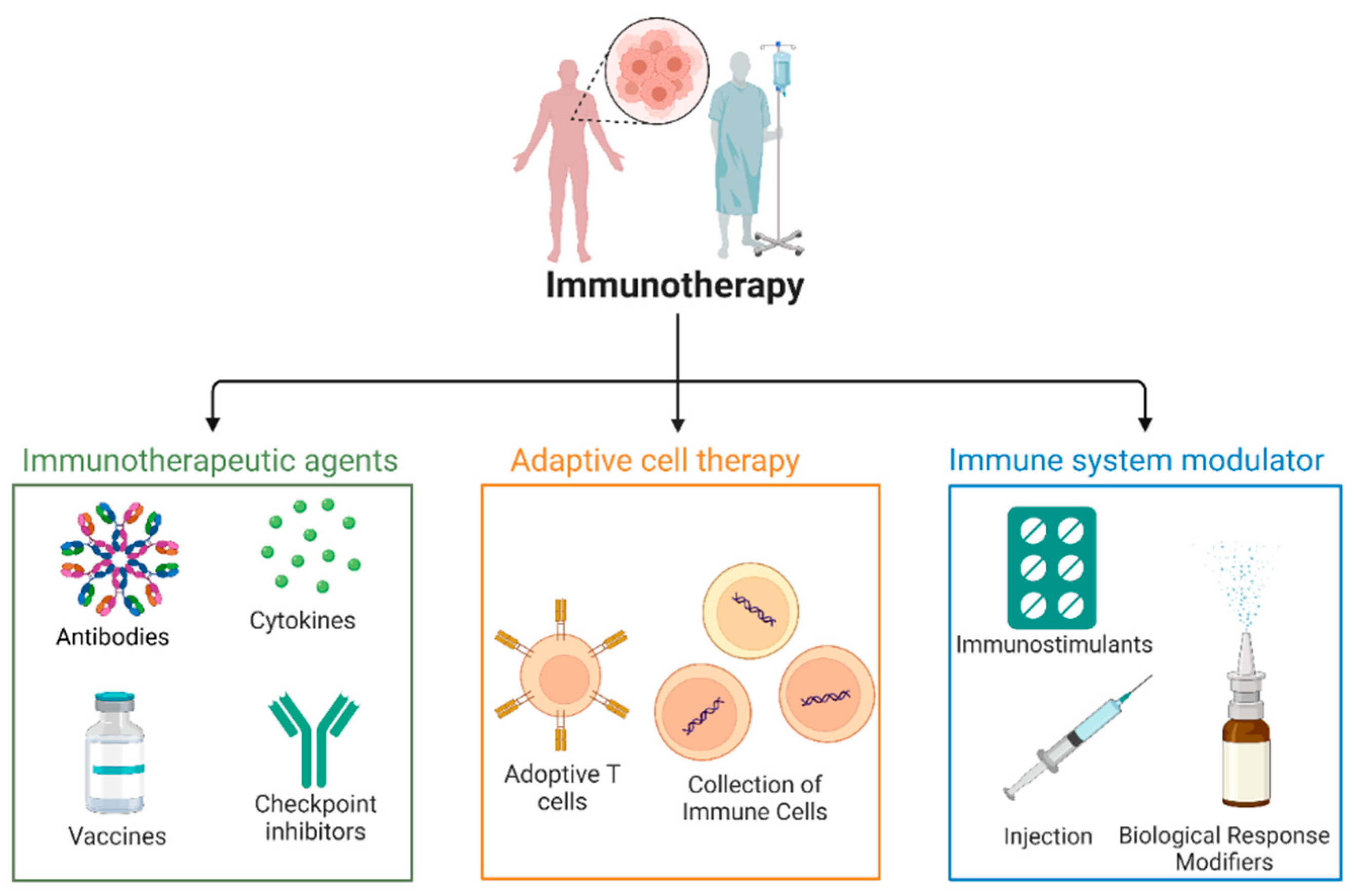

Figure 1.

Classification of Immunotherapy and Therapeutic Agents.Immunotherapy approaches are categorized into three major classes: Cell-Based Therapies, Immune Modulators, and Targeted Immunotherapies, each with distinct subclasses like Adaptive cell therapy involves the collection and modification of immune cells (e.g., T cells) to enhance anti-cancer activity before reinfusing them into the patient. Adoptive T cell expansion and infusion of modified T cells to strengthen their ability to target and eliminate cancer cells. Immune system modulators agents that adjust immune responses to either stimulate or suppress immune activity, optimizing the body's ability to fight cancer. Immunostimulant substances activate the immune system, boosting its capacity to combat cancer or infections. Injection biological response modifiers injections of cytokines or monoclonal antibodies designed to alter immune responses and improve treatment outcomes. Cytokines signaling proteins that enhance immune cell function, promoting an effective immune response against tumors. Monoclonal antibodies that target specific cancer antigens or deliver therapeutic agents directly to the tumor site. Tumor-specific vaccines that stimulate immune responses to recognize and attack cancer cells. Checkpoint Inhibitors are antibodies that block immune checkpoints (e.g., PD-1, CTLA-4), preventing immune evasion by cancer cells and promoting immune activity.

Figure 1.

Classification of Immunotherapy and Therapeutic Agents.Immunotherapy approaches are categorized into three major classes: Cell-Based Therapies, Immune Modulators, and Targeted Immunotherapies, each with distinct subclasses like Adaptive cell therapy involves the collection and modification of immune cells (e.g., T cells) to enhance anti-cancer activity before reinfusing them into the patient. Adoptive T cell expansion and infusion of modified T cells to strengthen their ability to target and eliminate cancer cells. Immune system modulators agents that adjust immune responses to either stimulate or suppress immune activity, optimizing the body's ability to fight cancer. Immunostimulant substances activate the immune system, boosting its capacity to combat cancer or infections. Injection biological response modifiers injections of cytokines or monoclonal antibodies designed to alter immune responses and improve treatment outcomes. Cytokines signaling proteins that enhance immune cell function, promoting an effective immune response against tumors. Monoclonal antibodies that target specific cancer antigens or deliver therapeutic agents directly to the tumor site. Tumor-specific vaccines that stimulate immune responses to recognize and attack cancer cells. Checkpoint Inhibitors are antibodies that block immune checkpoints (e.g., PD-1, CTLA-4), preventing immune evasion by cancer cells and promoting immune activity.

Antitumor Natural Immune Response

The process of antitumor immunity begins with DCs recognizing and sampling cancer antigens. DC maturation requires appropriate activation signals often provided by tumor cells overexpressing endoplasmic reticulum stress proteins like calreticulin (CRT) on their surfaces [

1]. CRT enhances tumor cell uptake by activated DCs, facilitating antigen presentation on major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and II molecules [

1,

31]. Once presented, DCs migrate to lymphoid organs, triggering T-cell responses. These responses depend on co-stimulatory molecule interactions, DC maturation signals, and the antigens presented [

32].

Effective T-cell activation requires interactions between CD28 on T cells and CD80/86 on DCs, leading to T-cell activation, proliferation, and cytokine production. Conversely, CTLA-4 or PD-1 receptor engagement with CD80/86 or PD-L1 suppresses T-cell responses and promotes regulatory T-cell (Treg) generation [

1]. Tumor cells evade immunity by expressing inhibitory molecules (e.g., CTLA-4, PD-L1), reducing MHC-I expression, recruiting Tregs, or producing immunosuppressive compounds like indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) [

33]. Stromal cells can further hinder T-cell activity by impairing adhesion and colonization [

8]. Tumor immune evasion involves static genomic abnormalities and dynamic epigenomic, metabolic, and micro-environmental factors, profoundly influencing antitumor responses and immune checkpoint blockade efficacy [

34].

Development of Checkpoint Inhibitors (CPIs)

The discovery of tumor regression following microbial infections inspired the first immunotherapeutic approaches [

35]. In the 1800s, W.B. Coley observed that inducing fever enhanced the immune system’s ability to combat tumors, laying the foundation for a safe, cost-effective cancer therapy [

36]. ICIs represent a transformative advance in immuno-oncology. Tumor cells evade immune surveillance by activating immune checkpoint pathways, suppressing the immune response. ICIs counteract this by disrupting these inhibitory pathways, revitalizing antitumor immunity [

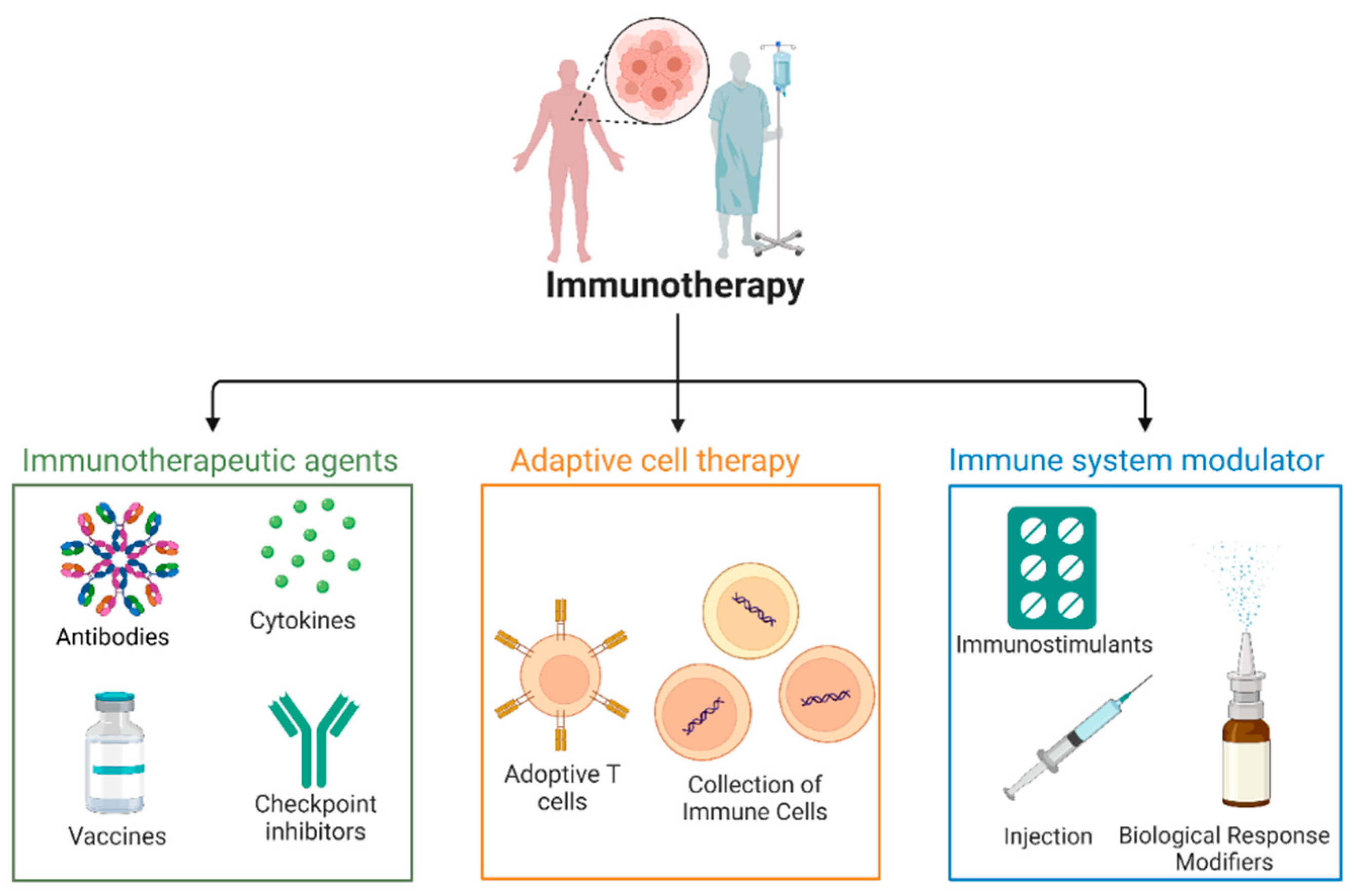

37]. The FDA has approved three ICI classes for cancer treatment: PD-1 inhibitors (e.g., Nivolumab, Pembrolizumab), PD-L1 inhibitors (e.g., Atezolizumab, Avelumab), and the CTLA-4 inhibitor (Ipilimumab) [

17]. Despite the success, only some patients benefit, such as tumor microenvironment (TME) phenotypes, immune desert, immune excluded, and immune inflamed affect immune responses differently [

37]. Severe immune-related adverse events (irAEs) arise from checkpoint inhibition, triggering autoimmune responses. Thus, predictive biomarkers are essential to identify responders and reduce irAEs, improving treatment precision and safety.

Figure 2.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors and their associated cancers. This figure highlights various immune checkpoint inhibitors (PD-1, PD-L1, CTLA-4, and LAG-3) and the cancers they target, including melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, colorectal cancer, and others.

Figure 2.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors and their associated cancers. This figure highlights various immune checkpoint inhibitors (PD-1, PD-L1, CTLA-4, and LAG-3) and the cancers they target, including melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, colorectal cancer, and others.

Mechanisms of Action

According to Zhang et al., cancer immune therapies can be classified into five main categories: immunological checkpoints, cytokine therapies, oncolytic viral treatments, adoptive cell transfer (ACT), and ICIs [

9]. While ACT therapies have advanced significantly, ICIs (a class of mAbs), have emerged as a cornerstone in medical practice. Immune checkpoints are molecules involved in immune tolerance, but cancer cells exploit them to evade immune surveillance [

7,

38]. Critical targets for ICIs include CTLA-4, PD-L1, and PD-1 [

9].

Cancer cells evade immune detection by overexpressing immune checkpoint proteins, which regulate immune responses and self-tolerance. When overexpressed, these proteins prevent the immune system from recognizing and attacking cancer cells. ICIs block co-inhibitory signaling, reviving antitumor immune responses [

39]. T cell activation requires two signals: the interaction between the T cell receptor (TCR) and antigenic peptides presented by MHC molecules and a co-stimulatory signal. Naive T cells need both signals to avoid energy, while the TCR-antigen complex can activate memory T cells. This dual-signaling process, regulated by immune checkpoints, ensures proper T cell activation and immune response control [

40,

41]. Engineered mAbs targeting checkpoints like CTLA-4 and PD-1 are increasingly used in cancer treatment.

Programmed Cell Death Receptor 1

PD-1 (programmed cell death protein 1), also known as CD279, is an immunoglobulin (Ig) class protein expressed on various immune cells, including T cells, B cells, myeloid cells, and natural killer (NK) cells [

1]. It is crucial in regulating immune responses and preventing excessive T-cell activation. PD-1 is commonly expressed in many tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) across different tumor types. The expression pattern of PD-1 varies between CD4

+ and CD8

+ T cells within the TILs; CD4

+ T cells are predominantly regulated by regulatory T cells (Tregs), which often express high levels of PD-1, whereas increased PD-1 expression on CD8

+ T cells indicates T cell dysfunction, characterized by features like exhaustion or energy, with reduced cytokine production and impaired effector functions.

PD-1 has two primary ligands: PD-L1 (B7-H1 or CD274) and PD-L2 (CD273) [

42,

43]. PD-L1 is broadly expressed in various cell types, including antigen-presenting cells (APCs), hematopoietic, and non-hematopoietic cells. It contributes to immune tolerance by inhibiting TCR-mediated lymphocyte proliferation and cytokine secretion when bound by PD-1. PD-L2, on the other hand, is mainly expressed by activated macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs). When either ligand binds to PD-1 on T cells, it transmits inhibitory signals that suppress T cell activation and proliferation, thus acting as a significant immune evasion mechanism in the tumor microenvironment [

28].

APCs expressing PD-L1 help prevent cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) lysis within the tumor environment by promoting mechanisms like apoptosis, anergy, exhaustion, and IL-10 production in T cells. PD-1 ligation also recruits Src homology 2 (SH2) domain-containing phosphatases 1/2, which inhibit T cell proliferation and cytokine release, contributing to immune tolerance and preventing autoimmunity without a specific antigen. However, chronic infections and malignancies can lead to persistent upregulation of PD-1 and PD-L1, impeding immune response and disrupting T cell function [

44,

45].

Tumor cells can aberrantly express PD-L1 as a strategy to evade immune surveillance. High PD-1 expression is commonly found in Tregs, and the interaction between PD-1 and its ligand promotes their proliferation within the tumor microenvironment. Immune checkpoint therapies, such as anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies, aim to enhance antitumor immune responses by reducing Treg activity and increasing effector T cell activity against tumor cells [

29]. These therapies do not directly kill cancer cells but leverage the host's immune system to boost its innate antitumor activity.

The regulation of PD-1 ligands (PD-L1 and PD-L2) in tumors and the tumor microenvironment can be driven by innate immune resistance and adaptive immune resistance. In innate immune resistance, the expression of PD-1 ligands is regulated by intrinsic oncogenic signaling pathways within the tumor cells, such as the PI3K-AKT pathway, which becomes active when tumor suppressor genes like PTEN are deleted or silenced. For example, glioblastomas can upregulate PD-L1 expression through constitutive oncogenic signaling. Conversely, adaptive immune resistance is driven by infiltrating T cells and inflammatory signals like interferon-gamma (IFNγ), which can induce PD-1 ligand expression on tumor cells as a response to immune pressure [

46,

47].

Understanding how PD-1 ligands are regulated in various tumor types is crucial for predicting which patients are more likely to benefit from immune checkpoint blockade therapies. High PD-L1 expression has been observed on tumor cells across several human malignancies, like high PD-1 expression on TILs. Studies in mouse cancer models have shown that forced expression of PD-L1 suppresses local antitumor immune responses, providing a rationale for combining PD-1 pathway-blocking therapies with other treatments to improve antitumor activity [

48,

49]. Biomarkers associated with PD-1 ligand expression can help personalize cancer immunotherapy, allowing clinicians to identify suitable candidates for immune checkpoint blockade. Ongoing research continues to investigate the interplay between oncogenic signaling pathways and immune responses within the tumor microenvironment, deepening our understanding of cancer immunology and identifying potential therapeutic targets [

49,

50].

Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte-Associated Protein 4 (CTLA-4)

CTLA-4 is a receptor on T cells (CD4

+ and CD8

+) that blocks T-cell activation, playing a pivotal role in immune regulation and tolerance mechanisms [

51]. It shares structural similarities with CD28, which co-stimulates T-cell activation, but CTLA-4 transmits inhibitory signals that reduce T-cell activation and proliferation. This balance between co-stimulatory and inhibitory signals is vital for controlling immune responses. The mechanisms of CTLA-4's inhibition are still under investigation, but research suggests that it activates protein phosphatases like SHP2 and PP2A, which counteract the kinase signals from TCR and CD28, dampening the activation signals [

52]. CTLA-4 also interacts with B7 proteins, competing with CD28 to prevent excessive immune responses, thus protecting tissues from autoimmunity [

53]. While CTLA-4 is expressed on activated CD8

+ T cells, its primary function involves suppressing helper CD4

+ T cells and enhancing Treg cells' immunosuppressive activity [

54,

55]. FOXP3, which regulates Treg lineage, controls CTLA-4 expression in these cells. Deletion or inhibition of CTLA-4 in Treg cells impairs their ability to regulate autoimmune and antitumor responses. The precise mechanisms by which CTLA-4 enhances Treg suppression are not fully understood, but inhibitory cytokines like TGF-β, IL-10, and IL-35 are likely involved.

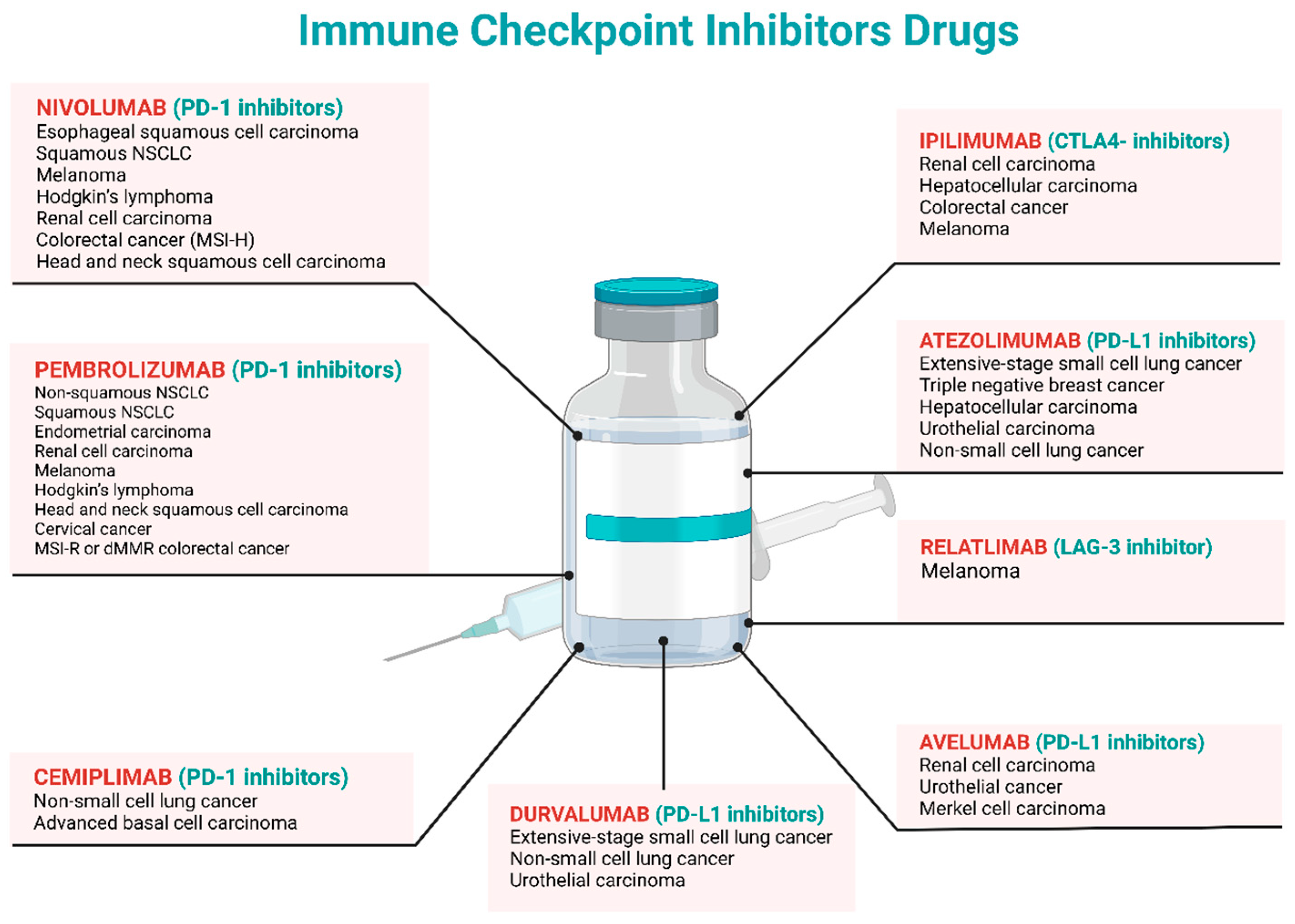

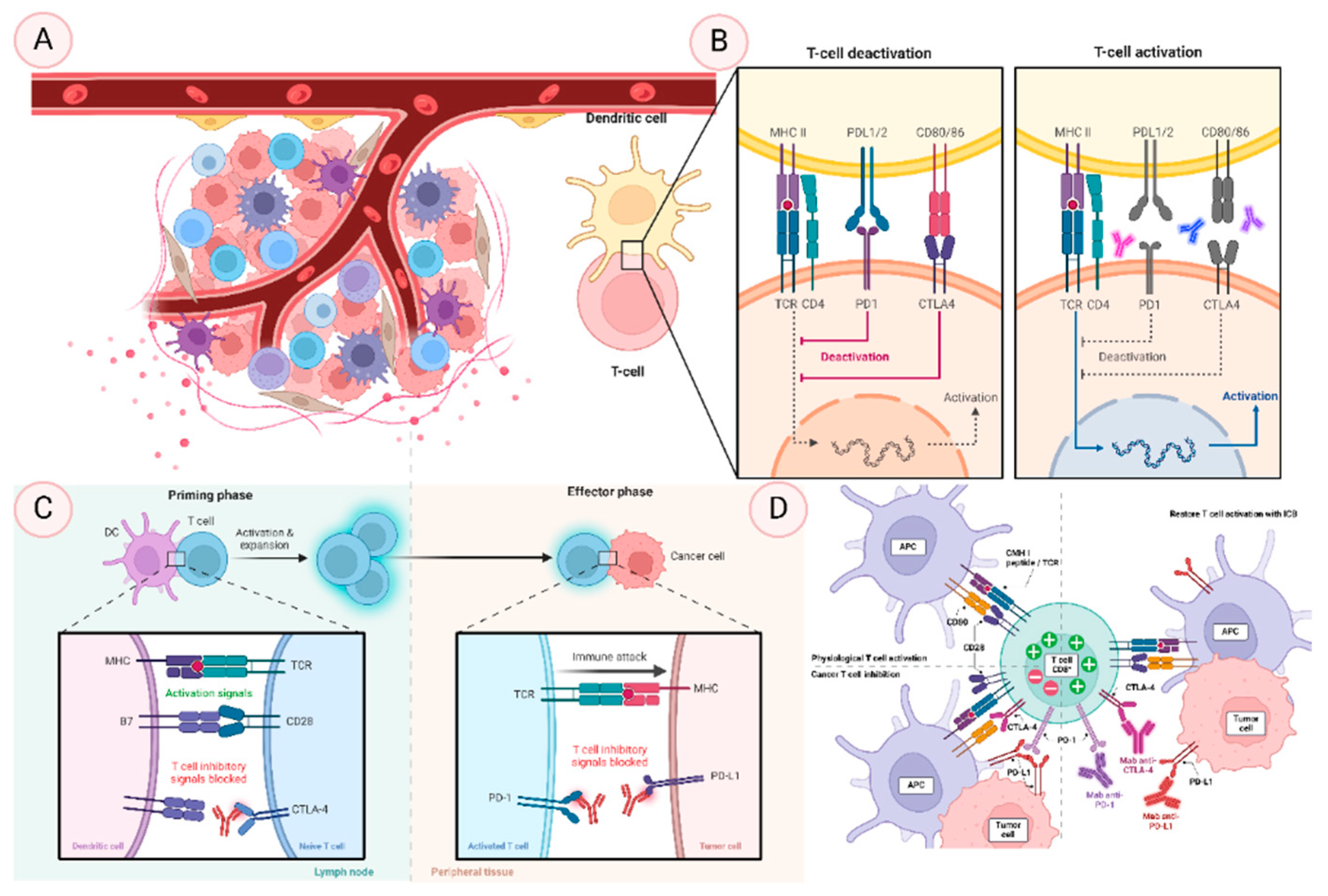

Figure 3.

Illustrates the dynamic mechanisms of immune checkpoint regulation and T cell activity, crucial for understanding cancer immunotherapy. It includes four sections: (A) highlights the circulation and interaction of immune cells like T cells, dendritic cells, macrophages, and antigen-presenting cells as they traverse the lymphatic system, bloodstream, and tissues, playing key roles in immune surveillance. (B) depicts the molecular mechanisms of T cell activation and deactivation, focusing on immune checkpoints like PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4, which balance immune responses by either initiating defense against pathogens or tumors or preventing autoimmunity. (C) contrasts the priming phase, where naive T cells are activated by antigen-presenting cells via MHC molecules, with the effector phase, where activated T cells proliferate and exert cytotoxic effects, regulated by immune checkpoints to ensure response control. (D) demonstrates how tumor cells inhibit T cell activity through checkpoint pathways and how immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapies, such as anti-PD-1 or anti-CTLA-4 antibodies, restore T cell function, enabling the immune system to attack cancer cells effectively.

Figure 3.

Illustrates the dynamic mechanisms of immune checkpoint regulation and T cell activity, crucial for understanding cancer immunotherapy. It includes four sections: (A) highlights the circulation and interaction of immune cells like T cells, dendritic cells, macrophages, and antigen-presenting cells as they traverse the lymphatic system, bloodstream, and tissues, playing key roles in immune surveillance. (B) depicts the molecular mechanisms of T cell activation and deactivation, focusing on immune checkpoints like PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4, which balance immune responses by either initiating defense against pathogens or tumors or preventing autoimmunity. (C) contrasts the priming phase, where naive T cells are activated by antigen-presenting cells via MHC molecules, with the effector phase, where activated T cells proliferate and exert cytotoxic effects, regulated by immune checkpoints to ensure response control. (D) demonstrates how tumor cells inhibit T cell activity through checkpoint pathways and how immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapies, such as anti-PD-1 or anti-CTLA-4 antibodies, restore T cell function, enabling the immune system to attack cancer cells effectively.

Molecular Interactions of ICIs

Immune checkpoint inhibition (ICI) has revolutionized cancer treatment by harnessing the body's immune system to fight cancer cells. The immune system has multiple layers of defense, starting with physical barriers such as the skin and mucous membranes, followed by macrophages and other immune cells. The third line of defense includes specialized organs and cells that trigger immune responses. However, when inhibitory immune checkpoints are overactivated, they weaken the immune system, allowing cancer cells or pathogens to proliferate. ICIs target inhibitory receptors such as PD-1, CTLA-4, LAG3, TIM3, TIGIT, and BTLA, leading to enhanced immune responses against malignancies. These receptors use specific signaling patterns like the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based switch motif (ITSM) and immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif (ITIM) to transmit inhibitory signals, suppressing immune activity. Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy has proven most effective in treating various cancers, including those of the blood, skin, lung, liver, bladder, and kidney [

55].

Surface-Level Regulation of Immune Checkpoints

Immune checkpoints are membrane proteins synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and transported to the cell surface through secretory vesicles and the Golgi apparatus. This process involves protein sorting mechanisms, ensuring only mature and functional checkpoints reach the surface. Glycosylation acts as a quality control system during this process [

8]. Once on the surface, immune checkpoints undergo internalization and recycling, allowing for dynamic regulation of their surface levels and enabling rapid modulation of cell signaling [

56]. Ubiquitination also plays a critical role, marking immune checkpoints for degradation in lysosomes or proteasomes and helping maintain a balance in checkpoint expression. This regulation influences immune cell signaling within the tumor microenvironment.

Regulation of PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA-4 Surface Expression

The core fucosylation pathway, mediated by Fut8, is required for PD-1 surface expression. In liver cancer, PD-1 can be internalized and targeted for proteasomal degradation by FBXO38 or recycled to the surface by TOX. PD-L1's surface retention is supported by N-glycosylation by STT3, but aberrant glycosylation due to phosphorylation at S195 causes degradation via endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD). Once internalized, PD-L1 can either be recycled back to the surface via CMTM6/4 or degraded in lysosomes by HIP1R. E3 ligases such as HRD1 and Cullin3-SPOP mediate PD-L1 ubiquitination, while CNS5 stabilizes it by removing ubiquitin tags. DHHC3 palmitoylates PD-L1 to prevent lysosomal degradation [

56]. For CTLA-4, N-glycosylation by Mgat1 ensures its surface retention, and its trafficking requires the TRIM/LAX/Rab8 complex and PLD/ARF1-dependent exocytosis. Internalization of CTLA-4 is accelerated by AP-2 through interaction with its YVKM motif. After internalization, CTLA-4 can either be recycled to the surface via LRBA or degraded in the lysosome [

56].

PD-1 Signaling and Ligand Engagement

Exosomal PD-L1 levels have been linked to non-responsiveness to anti-PD-1 therapy in melanoma patients. Recent studies suggest that PD-1 and PD-L1 interact in cis to reduce PD-1's inhibitory effect on T cells. PD-1 is phosphorylated at tyrosine residues in its cytoplasmic ITSM domain upon ligand binding, attracting phosphatases like SHP2, which dephosphorylate vital signaling molecules, thereby reducing T-cell activation. While the ITIM domain is optional, emerging research indicates its involvement in SHP2 activation [

57]. PD-1 inhibits T cells' co-stimulatory and antigen signaling pathways, translocating to the immunological synapse upon T cell activation and suppressing downstream signaling molecules like ZAP70. This inhibition extends to CD28 signaling, the PI3K-AKT pathway, and TCR signaling. SHP2 also plays a dual role, inhibiting and promoting TCR signaling under certain conditions. PD-1 signaling has been implicated in promoting immune suppression in hematological neoplasia, as observed in AML, where upregulation of PD-L1 contributes to macrophage polarization, Treg stimulation, and reduced T and NK cell activity [

58].

CTLA-4 Function and Mechanisms

CTLA-4 inhibits T-cell activation by binding to CD80/86 on APCs, blocking the co-stimulatory signals that CD28 provides typically [

58]. CTLA-4 also suppresses IL-2 release, which is crucial for T-cell proliferation [

59]. By capturing CD80/86 through trans-endocytosis, CTLA-4 reduces the availability of these co-stimulatory molecules, further inhibiting T-cell activation. Most CTLA-4 is stored in intracellular vesicles but moves to the surface upon TCR engagement. The internalization of CTLA-4 is regulated by its cytoplasmic tail, which interacts with proteins such as TRIM, AP-2, and AP-1. TCR activation induces CTLA-4 expression, and its increased surface presence prevents T-cell activation [

56]. Upon phosphorylation at Y165 in the immunological synapse, CTLA-4's cytoplasmic tail disrupts its interaction with AP-2, preventing internalization and ensuring that CTLA-4 stays at the synapse, exerting inhibitory signals [

59].

CTLA-4 in Tregs and Tumor Immunity

CTLA-4's role in Tregs is essential for controlling immune responses. Deletion of CTLA-4 in Tregs leads to autoimmune disorders and uncontrolled lymphocyte proliferation. CTLA-4 suppresses APC-mediated T-cell activation in Tregs by reducing CD80/86 expression. In anti-CTLA-4 therapy, Treg depletion enhances anti-tumor immune responses by reducing inhibitory signals from CTLA-4

+ Tregs. CTLA-4 blockade also enhances antigen presentation by APCs and boosts T-cell reactivity by lowering the activation threshold of TCR signaling [

59]. Through these mechanisms, CTLA-4 inhibition contributes to the therapeutic benefits of ICIs in cancer treatment. Understanding the precise role of CTLA-4 is critical for developing new immunotherapies to treat immune-related disorders, including cancer.

TIM3 (T Cell Immunoglobulin Mucin 3)

TIM3 has four ligands: phosphatidylserine (PS), galectin9, CEACAM1, and HMGB1. Galectin9 binds to TIM3's IgV domain, while CEACAM1 interacts in both cis and trans; trans interaction suppresses T cell activity, and cis is essential for TIM3 glycosylation and surface expression. HMGB1, present in tumor-associated DCs, inhibits innate immunity by interacting with TIM3. TIM3 also regulates antigen cross-presentation and efferocytosis in DCs by binding PS. The role of TIM3 in T cell effectors remains to be determined, as studies show conflicting results. TIM3 promotes short-lived effector T cells and enhances AKT/mTOR signaling in viral infection models. It interacts with TCR signaling molecules, and its inhibition improves synapse formation between TIM3 high CD8 T cells and target cells. TIM3's cytoplasmic domain contains phosphorylatable tyrosine residues (Y265 and Y272), which recruit p85 to activate NFAT. Bat3 binding to unphosphorylated TIM3 amplifies TCR signaling, but phosphorylation triggers Bat3 dissociation, altering TIM3's function [

60,

61].

LAG3

LAG3 binds MHC-II more strongly than CD4, potentially inhibiting CD4

+ T cell activation by blocking CD4-MHC-II interaction [

62]. However, its inhibitory function relies on its cytoplasmic domain, not CD4 competition [

63,

64]. LAG3 also limits CD8

+ T cell activity independently of MHC-II, suggesting other ligands like LSECtin, Galectin-3, and FGL1 [

65,

66]. Disrupting the LAG3-FGL1 interaction enhances T cell cancer immunity. LAG3, produced by Tregs, inhibits APC activity by binding MHC-II, contributing to immune regulation. Clinical cancer immunotherapy blocking LAG3 requires further study due to its complex role. LAG3 inhibits T cell proliferation and cytokine production by impairing TCR signaling, with key cytoplasmic motifs (EP repeats, KIEELE, serine phosphorylation) necessary for its function. ADAM10 and ADAM17 cleavage of LAG3 can restore T-cell activity.

TIGIT

TIGIT ligands CD155 (PVR) and CD112 (PVRL2) bind with higher affinity to CD155 [

67]. TIGIT translation inhibits T and NK cells via signaling [

68] and promotes IL-10 production in DCs via reverse CD155 signaling [

67]. While TIGIT and CD226 share ligands, TIGIT’s stronger affinity blocks CD226 co-stimulation [

69] and prevents CD226 homodimerization [

70]. The TIGIT cytoplasmic domain contains ITIM and ITT-like motifs, and tyrosine phosphorylation is required to suppress TIGIT in NK cells [

71]. SHIP1 is recruited by these motifs, with distinct effects on NF-κB, PI3K, and MAPK signaling [

72].

BTLA

BTLA ligands, such as HVEM, inhibit T cell activity by binding with BTLA/CD160 or LIGHT, a TNF superfamily member, providing a co-stimulatory signal [

73,

74]. BTLA/CD160 interacts with HVEM’s cysteine-rich domain 1 (CRD1), while LIGHT binds a separate site [

75]. Soluble LIGHT enhances BTLA-HVEM interaction, whereas membrane-bound LIGHT displaces BTLA [

76]. BTLA’s cytoplasmic domain contains ITIM, ITSM, and Grb2 motifs, which recruit SHP1/SHP2 upon phosphorylation to limit T cell activity [

73,

77]. In Tfh cells, BTLA-HVEM interaction attracts SHP1, blocking TCR signaling and suppressing CD40L to inhibit B cell growth [

78].

TNFR2

Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) binds to TNFR1 and TNFR2, with TNFR2 primarily inducing anti-inflammatory responses and enhancing cell viability [

79]. TNFR2 activates NF-κB through NIK and IKKα upon TNF binding, promoting survival and growth via MAPK and NF-κB/Rel pathways. The TNFR2-TRAF2-cIAP1-cIAP2 complex suppresses apoptosis. TNFR2 also activates VEGFR2 and the PI3K/Akt pathway through Etk, enhancing cell activation. Additionally, TNFR2 promotes STAT5 phosphorylation, suppressing immune responses [

80,

81]. In Tregs, TNFR2 signaling improves function, stability, and TCR response, with inhibition leading to increased Th17 development and STAT3 activity [

80].

Differences and Similarities in the Mechanisms of Action Among Different Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

CTLA-4 and PD-1 are key immune checkpoint molecules that regulate immune responses. CTLA-4 controls the early phases of T cell activation, while PD-1 acts later to prevent excessive immune activity and maintain tolerance. Combining therapies targeting both checkpoints has shown promising anti-cancer effects but also can lead to severe side effects, including autoimmune reactions. Understanding their molecular interactions is crucial for optimizing treatment strategies.

CTLA-4 is present on both regulatory T cells (Tregs) and activated conventional T cells, where it binds to CD80 and CD86 ligands on antigen-presenting cells (APCs). These ligands also interact with CD28 to initiate T cell activation, but CTLA-4’s higher affinity suppresses CD28 function, preventing the co-stimulation of self-reactive T cells. This regulatory role is vital for preventing autoimmune reactions, as loss of CTLA-4 leads to severe autoimmunity in both mice and humans [

82,

83,

84,

85].

PD-1, in contrast, regulates CD4 and CD8 T cells after activation, particularly during chronic infections or self-reactivity, leading to T cell exhaustion. Engagement of PD-1 with its ligands contributes to this exhausted phenotype, but blocking PD-1 can rejuvenate T cells, which has been beneficial in viral infections and cancer treatment [

86,

87,

88]. Despite their distinct functions, the CD28/CTLA-4 and PD-1 pathways are interconnected, as PD-1 signaling can affect TCR and CD28 signaling, highlighting the complexity of immune regulation [

89].

In summary, CTLA-4 controls the initial T cell response, while PD-1 regulates ongoing T cell activity in peripheral tissues to prevent excessive inflammation and tissue damage. Both checkpoints are crucial for maintaining immune balance and preventing immune-related diseases.

Evidence from Clinical Trials Demonstrating the Effectiveness of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors Across Diverse Cancer Types

Objective response rate (ORR) is crucial for evaluating therapeutic efficacy in oncology, and ICIs show varying ORRs across cancer types. For PD-1 inhibitors, Nivolumab shows ORRs of 47% (95% CI: 42-53) in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, 20% (95% CI: 14-28) in squamous non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and 31.7% (95% CI: 23.5-40.8) in melanoma. It has a higher ORR of 65% (95% CI: 55-75) in Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Pembrolizumab achieves an ORR of 47.6% (95% CI: 39.2-56.0) in non-squamous NSCLC and 57.9% (95% CI: 51.9-63.8) when combined with platinum-based therapy for squamous NSCLC. When paired with Axitinib for renal cell carcinoma, it has an ORR of 59% (95% CI: 54-64). Dostarlimab has shown a 41.6% (95% CI: 34.9-48.6) ORR for mismatch repair-deficient (dMMR) solid tumors. Cemiplimab produces a 39% (95% CI: 34-45) ORR in NSCLC and 31% (95% CI: 21-42) in advanced basal cell carcinoma. CTLA-4 inhibitors like Ipilimumab, in combination with Nivolumab, achieve an ORR of 40.4% (95% CI: 26.4-55.7) in renal cell carcinoma. PD-L1 inhibitors, including atezolizumab and Durvalumab, demonstrate strong efficacy in small-cell lung cancer and triple-negative breast cancer, with ORRs of 60.2% (95% CI: 53.1-67.0) and 68% (95% CI: 62-73), respectively. The LAG-3 inhibitor Relatlimab with Nivolumab has an ORR of 43.1% (95% CI: 37.9-48.4) in melanoma, showcasing the potential of multiple checkpoint inhibitors for improving outcomes [

90,

91].

Key Clinical Trials and Outcomes

Before combination trials, oncology medicines underwent extensive monotherapy testing, following traditional development paradigms. This works well for small compounds but may only partially reflect the potential of immunotherapy combinations. New trial designs, like bifurcated, zig-zag, and run-in designs, are increasingly used for combination therapies. Run-in trials evaluate monotherapy safety by sequentially combining patients, while zig-zag trials alternate dosages when clinical activity drivers are unclear. Bifurcated designs streamline combination testing by dividing studies into monotherapy and combination arms. Despite these advances, careful dose, sequence, and timing assessments, along with supportive solid care, are still vital for optimizing combination immunotherapy [

92].

Combination of ICIs and Targeted Therapy

Clinical trials demonstrate the effectiveness of immunotherapy combinations in advanced cancer treatment. In the Phase III KEYNOTE-426 trial for advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC), the combination of Pembrolizumab and Axitinib achieved a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 15.4 months, compared to 11.1 months with Sunitinib. Overall survival (OS) was not reached (NR) in the Pembrolizumab + Axitinib group, while it was 35.7 months for Sunitinib. The Phase II NCT02501096 trial for advanced endometrial cancer showed Pembrolizumab and Lenvatinib resulted in a median PFS of 7.4 months and OS of 16.7 months, with objective response rates (ORR) of 63.6% for microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) patients and 36.2% for microsatellite stable (MSS) patients. The Phase II LUX-Lung IO study in advanced squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the lung showed a median OS of 29.3 weeks with Pembrolizumab and Afatinib and an ORR of 12.5%. The TOPACIO Phase I/II study of Pembrolizumab and Niraparib in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) and ovarian cancer (OC) found that patients with BRCA1/2 mutations had a median PFS of 8.3 months, while those without had 2.1 months. For OC, the median PFS was 3.4 months with an ORR of 18%. In a Phase II trial targeting BRAFV600-mutated melanoma, combining Ipilimumab and Vemurafenib produced an OS of 18.5 months and a PFS of 4.5 months [

93].

The KEYNOTE-006 trial (NCT01866319) compared Pembrolizumab with Ipilimumab for melanoma, showing a median OS of 32.7 months for Pembrolizumab versus 15.9 months for Ipilimumab, with a PFS of 8.4 months versus 3.4 months. The KEYNOTE-042 trial (NCT02220894) for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) showed a median OS of 20 months with Pembrolizumab versus 12.2 months with chemotherapy and a PFS of 7.1 months versus 6.4 months. The KEYNOTE-048 trial (NCT02358031) for head and neck cancer showed a median OS of 14.7 months for Pembrolizumab versus 11 months for Cetuximab in patients with a combined positive score (CPS) of 20%. The Checkmate-067 trial (NCT01844505) showed a 36-month OS of 58% for Nivolumab + Ipilimumab, compared to 52% for Nivolumab alone and 34% for Ipilimumab alone. For NSCLC, the Checkmate-17/57 trials showed an OS of 17% at 36 months for Nivolumab versus 8% for Docetaxel [

94].

In the KEYNOTE-189 trial for non-squamous NSCLC, Pembrolizumab combined with chemotherapy improved OS to 69.2%, compared to 49.4% with chemotherapy alone. The IMpower 130 trial for NSCLC showed an OS of 18.6 months with Atezolizumab versus 13.9 months with chemotherapy. The IMpower133 trial showed an OS of 12.3 months in SCLC with Atezolizumab. For bladder cancer, the JAVELIN Bladder 100 trial showed an OS of 21.1 months with Gemcitabine + Cisplatin or Carboplatin plus Avelumab, compared to 14.3 months without Avelumab [

95].

Factors Influencing Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

Factors influencing the efficacy of ICIs in cancer treatment include the tumor microenvironment (TME), tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), tumor mutational burden (TMB), PD-L1 expression, DNA repair deficiencies, and microsatellite instability (MSI). Researchers are developing gene signatures to identify tumors with features that improve reactivity to ICI therapy, offering potential biomarkers for enhanced therapeutic strategies.

Tumor Microenvironment (TME)

The TME significantly impacts ICI efficacy, with three immune profiles correlating with patient responses to anti-PD1/PD-L1 therapy [

96,

97]. The

immune-desert phenotype lacks immune infiltration and may result from immune tolerance, insufficient T cell activation, or immune suppression. The

inflamed phenotype is characterized by pro-inflammatory cytokines and immune cells like CD8

+ T cells infiltrating the tumor. The

immune-excluded phenotype features CD8

+ T cells around but not inside the tumor, often due to stromal inhibitors or vascular barriers. Tumors with immune-desert or immune-excluded phenotypes are less likely to respond to ICIs, while inflamed phenotypes increase the chances of a response. Immune suppression within the TME, caused by dysfunctional T cells or regulatory T cells (Tregs), can further hinder ICI responses [

96]. Additionally, chemotherapy or radiation can enhance the TME’s immune susceptibility, improving responses to ICIs [

98,

99]. Immunogenomic studies have identified six immune subgroups within the TME that have prognostic and therapeutic significance [

100].

Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes (TILs)

TILs, particularly CD4

+ and CD8

+ T cells, predict response to ICIs across multiple cancer types, including metastatic melanoma and non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). For example, Usó et al. found that CD4

+ and CD8

+ T cell infiltration correlated with better survival outcomes in resected NSCLC patients [

101]. Similarly, Tumeh et al. demonstrated that CD8

+ T cell infiltration at the tumor’s invasive margin predicted better responses to anti-PD1 treatment in metastatic melanoma patients [

102]. Studies also suggest that higher expression of PD1 and CTLA4 on CD8

+ T cells correlates with improved ICI responses in melanoma [

103].

PD-L1 Expression

Tumors express PD-L1 as a mechanism to evade immune detection. When PD-L1 binds to PD1 on T cells, it inhibits immune responses, allowing tumor cells to escape immune surveillance [

104]. While PD-L1 expression can predict response to anti-PD1/PD-L1 therapy, its utility as a sole biomarker is limited due to variability in diagnostic methods and thresholds. Assays measuring PD-L1 expression, like the SP142 Assay, show varying levels of sensitivity and specificity, particularly in NSCLC [

105,

106]. Alternative methods, such as mRNA analysis of PD1 expression, have shown stronger correlations with ICI responses than protein-level PD-L1 expression and could improve predictive accuracy for ICI therapy [

107].

Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB)

High TMB correlates with more neoantigens, making tumors more recognizable to the immune system and enhancing ICI efficacy. Studies like CheckMate 026 and CheckMate 227 have shown that patients with high TMB benefit more from ICI therapy, regardless of PD-L1 status, demonstrating the predictive value of TMB [

108,

109]. Standardizing TMB assessment and analytical procedures remains essential to incorporating it into clinical practice.

Microsatellite Instability (MSI)

Tumors with MSI or deficiencies in mismatch repair (dMMR) tend to accumulate mutations, producing neoantigens that stimulate immune responses. MSI is prevalent in tumors such as endometrial, colorectal, and stomach cancers, where dMMR/MSI tumors often show higher response rates to ICIs [

110]. FDA approval of immunotherapy for MSI-high colorectal cancers underscores the potential of integrating MSI/dMMR status into clinical decision-making. Ongoing trials are exploring the predictive role of MSI in ICI responses across various tumor types, both in monotherapy and combination strategies [

111].

Gene Signatures

Gene expression profiling is used to develop molecular signatures predicting tumor responses to ICIs. These signatures can include factors like TIL infiltration, TMB, PD-L1 expression, and immune activation markers. Ayers et al. identified an 18-gene signature linked to IFN-γ production and T-cell activation, which correlated with clinical benefit from pembrolizumab in melanoma and other cancers [

112]. Further validation of this signature across multiple cancer types, including gastrointestinal and head and neck cancers, strengthens its potential as a predictive biomarker. In NSCLC, the POPLAR study found that a gene profile linked to T-cell activation and IFN-γ expression predicted better overall survival (OS) in patients treated with atezolizumab [

113]. Refining this signature, which now includes three genes-CXCL9, PD-L1, and IFN-γ has improved its ability to identify patients likely to benefit from ICI therapy [

106]. In conclusion, factors such as TME composition, TILs, PD-L1 expression, TMB, and MSI significantly influence the effectiveness of ICIs. Gene signatures incorporating these factors promise to improve patient selection and optimize immunotherapy strategies.

Safety Profiles of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

ICIs have become a cornerstone of immunotherapy for cancer treatment. However, their widespread use has led to an increase in immune-related adverse events (irAEs). Unlike the predictable side effects of traditional therapies such as chemotherapy and radiation, irAEs can manifest months after treatment initiation and persist throughout ICI therapy, often coinciding with changes in tumor size and appearance [

114]. Our research highlights that ICIs are associated with a higher frequency of severe adverse drug reactions (ADRs) compared to other drugs, particularly anticancer treatments. Notable irAEs include thyroid dysfunction, hepatic disorders, and gastrointestinal, respiratory, and skin-related issues.

Additionally, the safety profiles vary across ICI classes. For example, anti-PD-1 is more commonly linked to thyroid dysfunction and pneumonia, whereas anti-CTLA-4 is associated with hypophysitis, dermatologic reactions, and colitis [

115]. Further, ICI-induced cardiotoxicity is a significant concern, with cardiovascular events such as myocarditis and arrhythmias being observed [

116].

Cutaneous irAEs: Cutaneous irAEs, including pruritus, lichenoid dermatitis, and maculopapular rash (MPR), are frequent with ICIs. Severe reactions such as toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome, though rare, can also occur. The incidence is higher with combination therapies (59%-72%) compared to anti-PD-1 (44%-59%) or anti-CTLA-4 alone (34%-42%) [

117]. Anti-PD-1 is mainly linked to vitiligo, while anti-CTLA-4 typically causes rashes and itching. Autoimmune disease patients are more susceptible to these adverse events.

Digestive irAEs: ICIs can lead to severe gastrointestinal (GI) and hepatobiliary side effects. Common GI issues include diarrhea and enteritis, often occurring weeks or months after treatment. Enteritis is mainly linked to fever and abdominal pain, with CTLA-4 inhibitors causing more frequent and severe GI side effects than PD-1 inhibitors, especially in combination therapy [

118]. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can increase the risk of colitis and diarrhea when used with ICIs [

119].

Immune-mediated hepatotoxicity: ICIs can cause liver damage through immune activation, leading to various forms of hepatotoxicity. Hepatotoxicity occurs in 2%-10% of patients on monotherapy and up to 30% in combination therapy, with symptoms typically manifesting 6-12 weeks into treatment [

120]. Severe cases, such as acute liver failure, are rare but may occur, especially with high-dose CTLA-4 inhibitors. The risk is highest with combination therapy and high doses of CTLA-4 inhibitors [

121].

Endocrine Toxicity: Thyroid dysfunction, pituitary problems, and diabetes are common endocrine issues. Hypothyroidism or thyrotoxicosis are frequent thyroid issues, while hypophysitis may present with fatigue and gonadotropin insufficiency, particularly with anti-CTLA-4 therapy [

122]. Though rare, ICI-induced diabetes can cause diabetic ketoacidosis or silent hyperglycemia. Endocrine irAEs often appear 1-2 months after starting therapy, with hypophysitis emerging earlier, within 2-3 months [

123]. Early detection and management are crucial to prevent long-term damage.

Neurotoxicity: Neurotoxic irAEs, though rare (about 1% of cases), can significantly impact a patient’s quality of life and contribute to 11% of secondary fatalities [

124]. These include peripheral neuropathy, ocular lesions, aseptic meningitis, and encephalitis. Combination therapy with PD-1 and CTLA-4 inhibitors has the highest incidence of neurological irAEs (12%), followed by anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy (6.1%) and anti-CTLA-4 alone (3.8%) [

125]. Anti-CTLA-4 therapy is mainly linked to meningitis, while anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy is more commonly associated with myasthenic syndromes and cranial neuropathy [

126].

Cardiotoxicity: ICIs are associated with cardiovascular toxicity, including myocarditis and heart failure [

127]. While less severe than traditional chemotherapy, these effects are concerning, primarily since most clinical trials do not routinely assess cardiac markers such as troponin, making early detection challenging. PD-1/PD-L1 expression in cardiomyocytes may play a role in cardiac inflammation. Reports of myocarditis and heart failure typically appear within the first year of treatment, with the potential for delayed chronic cardiotoxicity [

128,

129].

Renal Toxicity: Renal toxicity, though rare, is an underreported issue with ICIs. Acute kidney injury (AKI), often caused by acute interstitial nephritis, occurs in a small percentage of patients, with PD-1 inhibitors, particularly pembrolizumab, showing higher incidence rates. The risk of nephrotoxicity increases with combination therapy [

130,

131]. Management involves steroids and, if necessary, temporary cessation of ICIs to prevent permanent damage.

Respiratory System Responses: ICIs frequently cause respiratory toxicity, particularly in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients, with 17% of patients reporting at least one respiratory event [

132]. Pneumonia and interstitial lung disease are common, and ICIs have been linked to various other respiratory issues, including lower respiratory tract infections [

133]. These adverse events are more frequent with anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 therapies than with anti-CTLA-4 treatments.

Fatal irAEs: Although rare, fatal irAEs can occur, mainly when severe autoinflammation is not responsive to treatment. Fatality rates from ICIs range from 0.4% to 1.2%, comparable to those of cytotoxic chemotherapy and targeted therapies. Fatal irAEs are often linked to myocarditis, pneumonitis, hepatitis, colitis, and neurological issues. These events tend to occur early in therapy, suggesting that ICIs rapidly trigger pre-existing inflammation. Older patients may be more susceptible. Careful monitoring, especially in combination therapy, is essential to identify early signs of irAEs and mitigate fatal risks

Long-Term Safety Data and Considerations for Patient Selection and Monitoring During Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Treatment

The increasing use of ICIs in cancer treatment has raised concerns about unintentional autoimmune reactions, particularly in patients with pre-existing autoimmune disorders [

141]. Critical aspects of ICI treatment include evaluating long-term safety data and assessing patient selection and monitoring. Long-term safety data analysis is crucial to understanding the persistence of therapeutic benefits and potential side effects. Ongoing assessment of immune-related adverse events (irAEs) aids in evaluating the risk-benefit ratio of ICIs. Research on outcomes following the early stages of treatment provides insights into late-onset side effects and treatment sustainability. Education for patients and caregivers is vital, focusing on the mechanisms of immunotherapies, possible adverse effects, and the distinction from conventional chemotherapy, which may lead to different therapeutic responses and irAEs [

142]. Immunotherapy may affect each patient differently, with irAEs potentially occurring at any stage, even after treatment. Patients must be aware that immunotherapy can have lasting effects on their immune systems and should inform all healthcare providers of their immunotherapy history and report any changes in their health. This proactive approach helps ensure early intervention for irAEs. Education should include information on safe medication handling, infection prevention, and safe sexual behavior [

142]. Patient and caregiver education should start before treatment and continue throughout. Patient selection for ICI therapy involves evaluating tumor type, stage, molecular characteristics, and prior treatment history. Early detection of adverse events is essential, and patients should be encouraged to report even minor symptoms. Standard assessments and questionnaires during visits can help healthcare providers identify potential irAEs. Consistent monitoring allows the clinical team to track changes over time [

143]. Even slight changes in a patient's condition may signal the onset of an adverse event during treatment. Wallet cards with symptoms to watch for and instructions for reporting to healthcare providers can be helpful for patients, caregivers, and other medical professionals who may encounter these patients [

144].

Predictive biomarkers, such as microsatellite instability (MSI), tumor mutational burden (TMB), and PD-L1 expression, help identify patients most likely to benefit from ICIs. Evaluating comorbidities, performance status, and risk factors for irAEs ensures optimal treatment outcomes. In the era of precision medicine, selecting suitable candidates for immune checkpoint blockade therapy is critical [

145]. Research into the tumor immune microenvironment has identified several factors, including intratumoral PD-L1 expression, CTLA-4, FoxP3, and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, as potential predictive biomarkers for immune checkpoint inhibitors [

146,

147]. Technological advances in sequencing also facilitate the identification of neoantigens, which can predict treatment responses, particularly in tumors with a high mutational burden [

148,

149]. Bioinformatics methods can further predict neoantigens from sequencing data, improving patient selection and treatment adaptability. Prompt identification and management of irAEs are crucial to reducing treatment-related morbidity and mortality. The Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) provides a standardized system for assessing irAE severity and guiding treatment decisions.

Current Research on Novel Targets Beyond PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA-4

The treatment for solid tumors has advanced significantly with ICIs, such as anti-CTLA-4, PD-1, and PD-L1. However, challenges like immune-related adverse events and treatment resistance remain. Targeting additional immune checkpoints in the tumor microenvironment could address these limitations. Checkpoints under investigation include LAG-3, TIGIT, TIM-3, VISTA, B7-H3, GITR, OX40, ICOS, and BTLA, with ongoing clinical studies to enhance treatment efficacy and manage ICI-related complications.

-

1.

LAG-3 (Lymphocyte Activation Gene-3) is a type-I transmembrane protein found on activated T cells, NK cells, B cells, and plasmacytoid DCs. It interacts with ligands like MHC-II, LSECtin, galectin-3, and FGL1, leading to immune cell exhaustion and cytokine suppression. LAG-3 inhibitors are being tested alone and in combination with other ICIs.

-

2.

TIM-3 (T Cell Immunoglobulin and Mucin Domain-Containing Protein 3) is expressed on exhausted T cells and regulates immune responses. TIM-3 blockade is under investigation as a potential immunotherapy strategy.

-

3.

TIGIT (T cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains) is expressed in NK and T cells. It inhibits T cell activation and enhances Treg activity by binding to its ligands. TIGIT inhibitors are being studied alone and in combination with other ICIs.

-

4.

VISTA (V-domain Ig suppressor of T cell activation) is expressed in T cells, myeloid cells, and tumor cells. It promotes immune tolerance and suppresses T cell activation, making VISTA a target for ongoing cancer immunotherapy research.

-

5.

B7-H3 (B7 homolog 3) is expressed on tumor cells and vasculature, influencing tumor growth and immune responses. It is being explored as a target for cancer immunotherapy.

-

6.

GITR (Glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor-related protein) is expressed in T cells and NK cells and enhances T cell activation and antitumor immunity. GITR agonists are being tested alone and in combination with other immunotherapies.

-

7.

OX40 and ICOS, expressed on activated T cells, are also being researched for their roles in T cell survival, proliferation, and effector function.

-

8.

BTLA (B and T Lymphocyte Attenuator) regulates T cell activation and immune responses, with blocking strategies being tested to enhance antitumor immunity.

Research into other targets like CD73, IDO, and A2AR, as well as combination therapies, promises to improve cancer immunotherapy outcomes further [

150,

151].

Ongoing Clinical Trials and Preclinical Research on Combination Therapies

Table 1.

Current status of preclinical research on Combination therapies.

Table 1.

Current status of preclinical research on Combination therapies.

| IC Target |

Drug |

Tumor |

Result |

PD-1

PD-L1 |

Vinorelbine

Cyclophosphamide Fluorouracil |

B-cell lymphoma

Breast cancer |

Synergistic effect induction [152] |

| PD-L1 |

Gemcitabine |

Gastrointestinal cancer |

Suppression of tumor growth, decreased numbers of MDSCs and M2 macrophages, and enhanced OS [153] |

| PD-1 |

Gemcitabine |

Mesothelioma |

Regression of tumors and increased OS rate [154] |

| PD-1 |

Paclitaxel |

Triple-negative breast cancer |

Alteration of the tumor immunological milieu to produce a synergistic impact with ICI [155]

|

| PD-L1 |

Cisplatin |

Ovarian cancer |

Extended OS in Treated Mice [156] |

| PD-L1 |

Cisplatin |

Lung cancer |

Reduces the growth of tumors [157] |

PD-1

PD-L1 |

Methotrexate

Vinblastine

Doxorubicin

Cis-platin

Cyclophosphamide |

Colon cancer

Bladder cancer |

Significant and strong anti-tumor response in vivo [158]

|

Ongoing Trials

Several clinical trials listed on ClinicalTrials.gov explore combinations of cancer and non-cancer drugs with ICIs. For example, NCT03970252 investigates Nivolumab with 5-Fluorouracil, Oxaliplatin, Irinotecan, and Leucovorin calcium for borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. NCT03907475 evaluates Durvalumab with Carboplatin, Capecitabine, Nab-paclitaxel, and others for advanced solid tumors. Pembrolizumab is the focus of multiple trials: NCT03719105 studies its combination with chemotherapy and allogeneic stem cell transplant for NK T-cell leukemia/lymphoma, while NCT02638090 explores its use with Vorinostat for Stage IV non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Additionally, NCT03200847 assesses Pembrolizumab and All-Trans Retinoic Acid (ATRA) in advanced melanoma. Finally, the MORPHEUS HR+BC trial (NCT03280563) investigates Atezolizumab with various agents like Entinostat and Tamoxifen for HR-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer. These studies highlight innovative strategies combining ICIs with other therapies to enhance cancer treatment [

159].

Several clinical trials are exploring the efficacy of ICIs in combination with other therapies for various cancers:

NCT03264404: Combines pembrolizumab and azacitidine for pancreatic cancer.

NCT03424005: Part of Morpheus-TNBC, it tests atezolizumab with selicrelumab, cobimetinib, gemcitabine+carboplatin, or eribulin, capecitabine, bevacizumab, and ipatasertib for advanced triple-negative breast cancer.

NCT03886311: Evaluates nivolumab, trabectedin, and talimogene laherparepvec (an oncolytic virus) for sarcoma.

NCT02778685: Studies pembrolizumab with palbociclib and letrozole in postmenopausal patients with metastatic ER-positive breast cancer.

NCT01658878: Tests ipilimumab, nivolumab, and cabozantinib for hepatocellular cancer.

NCT03445858: Examines pembrolizumab with decitabine and radiation in pediatric and young adults.

NCT03516279: Uses pembrolizumab with dasatinib, imatinib mesylate, or nilotinib for chronic myeloid leukemia with minimal residual illness.

NCT03873818: Investigates low-dose ipilimumab with pembrolizumab for brain-metastatic melanoma.

NCT02779751: Combines pembrolizumab, abemaciclib, and anastrozole for advanced lung or breast cancers.

NCT03646461: Tests nivolumab, cetuximab, and ibrutinib for recurrent/metastatic head and neck squamous cell cancer (HNSCC).

These trials highlight diverse strategies to enhance cancer therapy using ICIs and adjunct therapies.

Overview of Promising Ongoing Phase 3 Clinical Studies

Numerous phase 3 trials explore ICIs combined with other therapies for cancer treatment. These studies target checkpoints such as PD-1, PD-L1, LAG-3, TIGIT, and TIM-3.

Colorectal Cancer: NCT05064059 tests Favezelimab + Pembrolizumab vs. Regorafenib or TAS-102 in 432 PD-1-positive patients, concluding November 2024.

Small Cell Lung Cancer (SCLC): NCT04256421 evaluates Tiragolumab + Atezolizumab + chemotherapy (CE) vs. placebo + Atezolizumab + CE in 490 participants, ending March 2024.

Melanoma: NCT05352672 examines Fianlimab + Cemiplimab vs. Pembrolizumab or placebo + Cemiplimab, enrolling 1590 patients, completing April 2031.

Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC): NCT04294810 studies Tiragolumab + Atezolizumab vs. placebo + Atezolizumab in 635 participants, concluding February 2025.

Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma (ESCC): NCT04543617 tests Tiragolumab + Atezolizumab in 750 patients, ending December 2025.

Myelodysplastic Syndromes (MDS) and CMML-2: NCT04266301 evaluates MBG453 + Azacitidine vs. placebo + Azacitidine in 530 patients, concluding January 2027.

NSCLC: NCT04736173 (625 participants) compares Zimberelimab ± Domvanalimab to chemotherapy, completing June 2026, while NCT04866017 (900 participants) evaluates Ociperlimab + Tislelizumab + chemoradiation vs. Tislelizumab or Durvalumab combinations, concluding September 2025.

Additionally, preclinical studies highlight the therapeutic promise of LAG-3-targeting drugs, especially combined with PD-1 inhibitors. At least 13 LAG-3 modulators, including anti-LAG-3 antibodies (e.g., Relatlimab, LAG525), bispecific antibodies (e.g., FS118, MGD013), and others, are under investigation. Trials assess their safety and efficacy in cancer treatment [

64,

160].

Potential Future Directions in the Field of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

Recent advances in CIs have transformed cancer treatment and will shape its future direction. ICIs have demonstrated efficacy in cancers such as Hodgkin's lymphoma, lung cancer, bladder cancer, renal cell carcinoma, and melanoma. Their potential in colorectal, breast, head, and neck cancers are being explored in ongoing trials and through recent drug approvals.

Emerging ICIs and Their Targets

Novel ICIs aim to modulate immune checkpoints and other pathways to enhance immune responses:

TIM-3: Drugs like MBG453, Sym023, and TSR-022 block TIM-3, a checkpoint molecule that restores T cell activation when inhibited.

A2aR: Inhibitors EOS100850 and AB928 promote T cell and antigen-presenting cell (APC) activation.

LAG-3 (CD223): LAG525 and REGN3767 target LAG-3 to activate T cells.

B7-H3/B7-H4: MGC018 and FPA150 block these proteins, which inhibit immune responses.

CD73: CPI-006 inhibits CD73, enhancing T cell and APC activation by reducing adenosine-mediated suppression.

PVRIG/PVRL2: COM701 inhibits PVRIG, promoting T-cell activation.

NKG2A: Monalizumab suppresses NKG2A, improving immune function.

Axl: EnaV targets Axl to activate APCs and inhibit tumor spread.

Ang-2: Trebananib blocks Ang-2, reducing tumor-induced angiogenesis.

CLEVER-1: FP-1305 enhances APC activation by targeting CLEVER-1.

IL-8: BMS-986253 reduces tumor growth by mitigating IL-8-mediated immunosuppression.

Phosphatidylserine: Bavituximab promotes T cell and APC activity.

SEMA4D: Pepinemab inhibits SEMA4D, slowing tumor growth.

FAK: Defactinib targets tumor growth by inhibiting FAK.

LIF: MSC-1 suppresses tumor-promoting cytokines, activating immune cells.

CCL2/CCR2: PF-04136309 recruits T cells to tumors.

CD47/SIRPα: Drugs like Hu5F9-G4 enhance immune activation by overcoming phagocytosis resistance.

CSF-1/CSF-1R: Lacnotuzumab and emactuzumab enhance APC activity.

CEACAM5/6: NEO-201 enables T cell activation while suppressing tumor growth.

CEACAM1: CM24 boosts T and NK cell activation.

Challenges and Limitations

Many emerging ICIs need more robust clinical trial data. Their efficacy as monotherapies is uncertain, and the best combinations and indications are yet to be established. Toxicities, especially in combination therapies, remain a significant concern. Further studies are crucial to optimize their clinical application

Combination Therapy

Patients with malignancies resistant to traditional therapies like radiation and chemotherapy faced poor prognoses in past decades, compounded by damage to healthy cells. Recent advancements in therapies targeting immune cells, aberrant proteins, and the tumor microenvironment have significantly improved outcomes for some patients. While small molecules and immunotherapy have provided transformative treatments, challenges persist, including poor responses, acquired resistance, and severe side effects. Researchers are investigating combinations of ICIs with targeted therapies, chemotherapy, and radiation to address these issues. Immunotherapies targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 axis and CTLA-4, such as nivolumab and ipilimumab, have demonstrated substantial potential in enhancing anti-tumor immunity. This strategy leverages synergistic mechanisms to counteract cancer cell immune evasion. For example, in a 6.5-year follow-up of metastatic melanoma patients, combination therapy showed a 57% overall survival rate compared to 43% with nivolumab alone and 25% with ipilimumab alone. Since then, this combination has been approved for various malignancies, including advanced RCC, HCC, metastatic CRC with dMMR or MSI-H, NSCLC, and MPM. Newer ns, like relatlimab and nivolumab, targeting PD-1 and LAG-3, have also yielded promising outcomes, enhancing anti-tumor responses in advanced melanoma. Ongoing Phase III/IV clinical trials aim to improve the safety and efficacy of dual or multiple checkpoint inhibitor therapies across diverse cancer types.

Combining ICIsotherapy has also gained traction due to chemotherapy's ability to induce immunogenic cell death and disrupt tumor escape pathways. Agents like gemcitabine, cyclophosphamide, and fluorouracil (5-FU) have been shown to stimulate immune cells, increase tumor-infiltrating T cells, and enhance circulating NK cells. Clinical trials combining gemcitabine or cisplatin with PD-L1 inhibitors, such as nivolumab, report higher objective response rates than monotherapies. The FDA has approved PD-L1 inhibitors durvalumab and atezolizumab with chemotherapy as first-line treatments for advanced SCLC, resulting in improved overall survival. These findings underscore combining ICIs with conventional treatments to enhance cancer therapy outcomes and warrant further investigation.

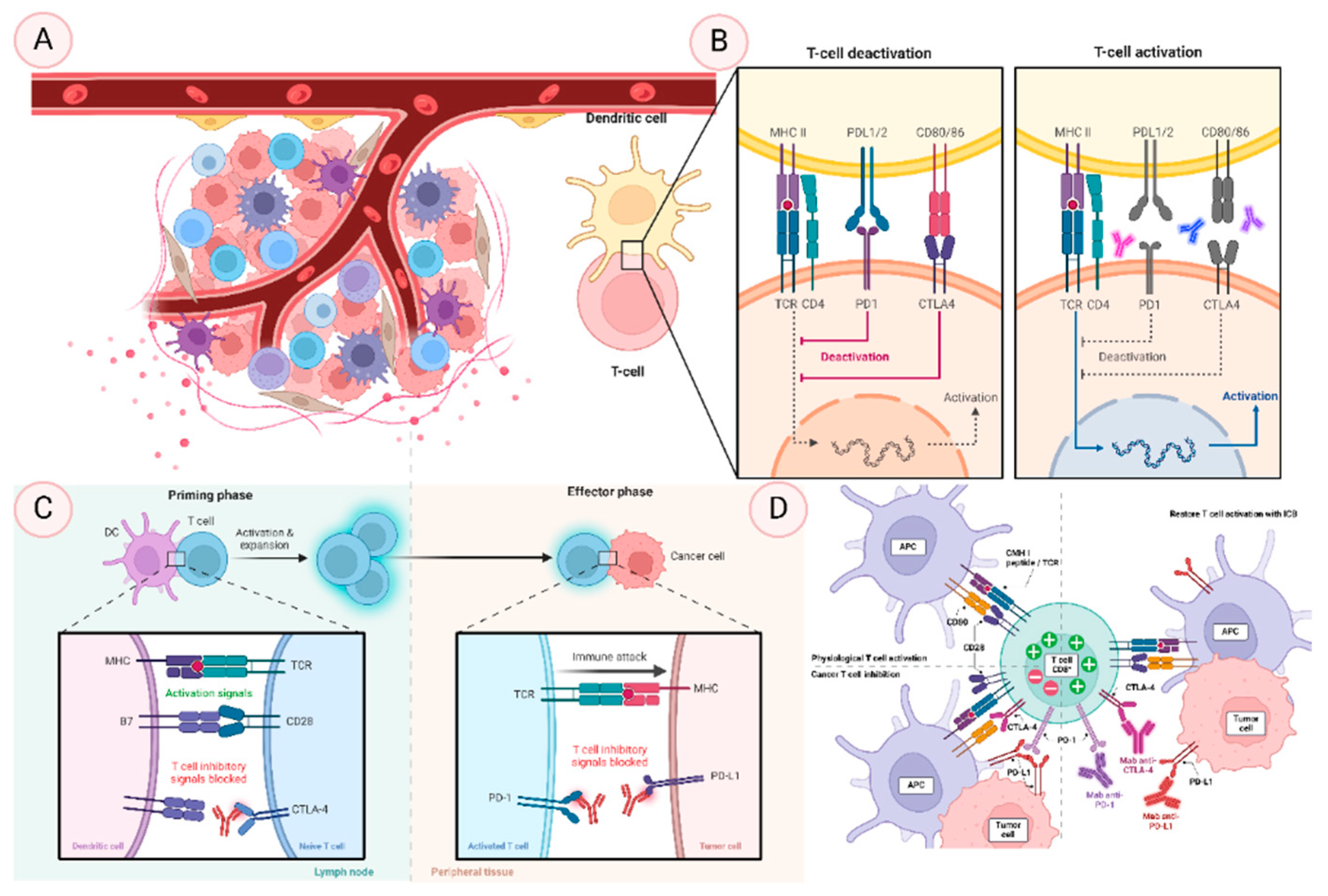

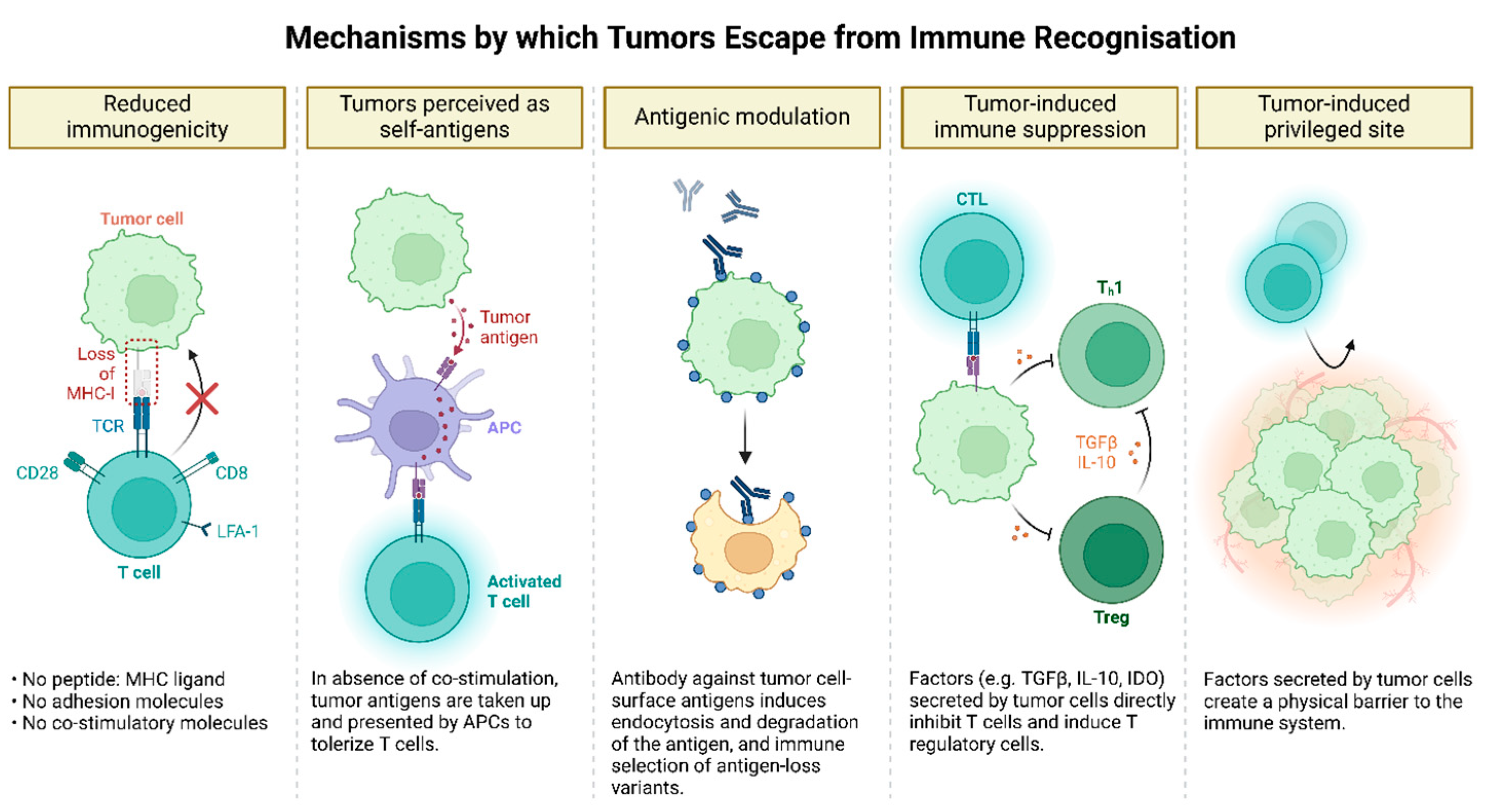

Figure 4.

Mechanisms of Tumor Immune Evasion. Tumors evade immune surveillance through multiple mechanisms. They reduce immunogenicity by downregulating tumor antigens or MHC molecules, limiting recognition by immune cells. Tumor cells can mimic host molecules by expressing altered self-antigens or neoantigens, causing the immune system to tolerate them as "self." They also modulate surface antigen expression through shedding or internalization, further reducing immune detection. Additionally, tumors create an immunosuppressive microenvironment by secreting factors like TGF-β and IL-10 and recruiting suppressive cells such as regulatory T cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells, which dampen immune responses. Moreover, tumors establish immune-privileged sites through physical barriers like the extracellular matrix and biochemical changes, restricting immune cell infiltration and enhancing their ability to evade destruction.

Figure 4.

Mechanisms of Tumor Immune Evasion. Tumors evade immune surveillance through multiple mechanisms. They reduce immunogenicity by downregulating tumor antigens or MHC molecules, limiting recognition by immune cells. Tumor cells can mimic host molecules by expressing altered self-antigens or neoantigens, causing the immune system to tolerate them as "self." They also modulate surface antigen expression through shedding or internalization, further reducing immune detection. Additionally, tumors create an immunosuppressive microenvironment by secreting factors like TGF-β and IL-10 and recruiting suppressive cells such as regulatory T cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells, which dampen immune responses. Moreover, tumors establish immune-privileged sites through physical barriers like the extracellular matrix and biochemical changes, restricting immune cell infiltration and enhancing their ability to evade destruction.

Summary of the Key Findings and Implications of the Review

This review delves into cancer immunotherapy, spotlighting ICIs as transformative agents in cancer treatment. It explains how ICIs stimulate effector immune cells by targeting checkpoint proteins like PD-L1, PD-1, and CTLA-4, triggering robust anti-tumor responses. The distinctions, synergies, and mechanisms of ICIs are explored alongside their molecular interactions and signaling pathways. Clinical data affirm their efficacy across cancers, while discussions address safety, immune-related adverse events, and personalized patient care. Emerging biomarkers, innovative delivery methods, and novel targets beyond traditional checkpoints are highlighted, emphasizing combination therapies. Challenges like immunotherapy resistance are acknowledged, steering future research and applications. This comprehensive assessment underscores ICIs’ role in ushering in personalized cancer treatments, paving the way for improved interventions and outcomes in the fight against cancer.

Challenges and Future Prospects

The application of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies has revolutionized personalized medicine and cancer research. However, translating these advances into clinically effective treatments for various cancers remains challenging due to several factors:

Genomic Data Complexity: Cancer's genetic instability, characterized by ploidy changes, heterogeneity, and normal contamination, complicates the identification of meaningful genomic changes in sequencing data, requiring advanced bioinformatics methods [

161].

Data Interpretation and Integration: NGS generates vast data, including amplifications, deletions, single nucleotide variations (SNVs), and interchromosomal rearrangements [

162]. Integrating and analyzing this data to derive actionable insights remains difficult.

Immunogenic Mutations: While NGS can identify tumor mutations, not all mutations trigger immune responses. Validating these mutations through experimental and bioinformatics methods is essential to determine their immunogenicity.

Predicting Treatment Response: Despite providing insights into tumor biology, NGS alone cannot reliably predict how patients will respond to immunotherapy, as other factors like tumor microenvironment and immune cell infiltration also play critical roles in treatment outcomes [

163].

Therapeutic Resistance: Immunotherapy resistance is a significant issue, with many patients developing resistance over time. Ongoing research focuses on understanding resistance mechanisms and identifying predictive biomarkers.

Cost and Accessibility: Although NGS costs have decreased, it remains financially burdensome for many patients and healthcare systems. Making NGS testing more affordable and accessible is crucial for widespread clinical adoption [

164].

Regulatory and Reimbursement Challenges: Regulatory approval and reimbursement issues hinder the integration of NGS into standard clinical practice. Streamlining these processes is necessary for broader application in cancer treatment.

Biomarker-driven clinical trials utilize genomic analysis to identify therapeutically relevant alterations by examining circulating cancer cells and free DNA. These trials face challenges with tumor heterogeneity and resistance mechanisms, requiring repeated biopsies for insights into treatment strategies [

165]. Key features of these trials include:

Precision Medicine: Matching patients to targeted treatments based on specific genomic abnormalities maximizes efficacy and minimizes side effects.

Real-time Monitoring: Serial analysis of circulating tumor DNA helps track tumor evolution and resistance mechanisms.

Patient Stratification: Patients are grouped based on molecular markers, leading to more precise treatment assignments.

Adaptive Trial Designs: Trial designs evolve based on gathered data, optimizing treatment strategies and outcomes.

Collaboration: Successful biomarker-driven studies require cooperation among researchers, doctors, industry partners, and regulatory authorities.

Combinational immunotherapy has shown promise in improving efficacy across various cancers. While combining immune checkpoint inhibitors like anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 presents challenges, synergy with other treatments, such as radiation or chemotherapy, may enhance overall therapeutic responses [

166]. However, further research is necessary to identify optimal combinations, dosages, and patient populations for these strategies.

Future Research Directions and Clinical Applications

Immunotherapy holds promise for treating infectious diseases, autoimmune conditions, and cancer. Personalized immunotherapies are being developed tailored to a patient's immune profile, tumor features, and genetics, such as genetically modified T or natural killer cells in adoptive cell transfer (ACT). Combining immunotherapy with radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapies may improve outcomes and overcome resistance mechanisms. Research is focused on overcoming immune evasion by tumors, including antigen presentation loss, immunosuppression, and checkpoint molecule overexpression (e.g., PD-1, CTLA-4), with new drugs targeting these processes to enhance immunotherapy. Modifying the tumor microenvironment to promote immune cell infiltration or target immunosuppressive cells (like regulatory T cells) could improve treatment efficacy. Novel immunomodulatory drugs, such as immune agonists and cytokines, are being explored to boost immune responses while minimizing off-target effects. Immunotherapy also shows potential for treating non-cancerous diseases like autoimmune disorders (e.g., multiple sclerosis) and infections (e.g., HIV). Individualized immunotherapy strategies are needed for pediatric patients to balance effectiveness and minimize long-term side effects. Identifying biomarkers, such as gene expression and immune cell subsets, is crucial for patient selection and treatment response prediction. Overcoming resistance mechanisms, improving drug delivery, and advancing immunotherapy are crucial to transforming cancer treatment and providing new therapeutic options for various diseases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and review outline: RKP; Manuscript writing: SD, MD, and ST; Review and edit: RKP and MD; Diagrams: MK; Supervision: RKP.

Acknowledgments

RKP is thankful to BioRender for providing accessible tools to create high-resolution diagrams.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kciuk, M.; Yahya, E.B.; Mohamed Ibrahim Mohamed, M.; Rashid, S.; Iqbal, M.O.; Kontek, R.; Abdulsamad, M.A.; Allaq, A.A. Recent Advances in Molecular Mechanisms of Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allard, B.; Aspeslagh, S.; Garaud, S.; Dupont, F.A.; Solinas, C.; Kok, M.; Routy, B.; Sotiriou, C.; Stagg, J.; Buisseret, L. Immuno-oncology-101: overview of major concepts and translational perspectives. Semin Cancer Biol 2018, 52, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farkona, S.; Diamandis, E.P.; Blasutig, I.M. Cancer immunotherapy: the beginning of the end of cancer? BMC Med 2016, 14, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topalian, S.L.; Weiner, G.J.; Pardoll, D.M. Cancer immunotherapy comes of age. J Clin Oncol 2011, 29, 4828–4836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Allison, J.P. Immune checkpoint targeting in cancer therapy: toward combination strategies with curative potential. Cell 2015, 161, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellman, I.; Coukos, G.; Dranoff, G. Cancer immunotherapy comes of age. Nature 2011, 480, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z. The history and advances in cancer immunotherapy: understanding the characteristics of tumor-infiltrating immune cells and their therapeutic implications. Cell Mol Immunol 2020, 17, 807–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]