1. Introduction

Mobile robots are a type of robots capable of perceiving their surroundings and utilizing sensor information to autonomously or semi-autonomously navigate the environment and perform specific tasks, with autonomous motion planning being a key capability for task execution. The motion planning algorithms for mobile robots aim to find a path that satisfies geometric, kinematic, dynamic, and input constraints [

1], encompassing path planning and path tracking. Path planning can be further divided into global path planning and local path planning, also referred to as path searching and trajectory optimization [

2]. Global path planning typically searches for geometrically feasible routes, which are not directly suitable for the robot as robots cannot make sharp turns abruptly and need to decelerate [

3]. Local path planning generates a trajectory with velocity and directional information, taking into account the control inputs along the trajectory to ensure smooth motion.

Local path planning for mobile robots is typically categorized into three types in the field of mobile robotics: artificial intelligence algorithms, bio-inspired algorithms, and classical algorithms. Classical algorithms can be further divided into sampling-based methods, curve interpolation-based methods, and optimization-based methods [

4].

Artificial Intelligence (AI) algorithms use neural networks and reinforcement learning for path planning, such as Q-learning [

5]. Currently, AI algorithms are primarily employed in the preprocessing stage of planning to provide prior knowledge, and are less frequently used as standalone path planners.

Bio-inspired algorithms refer to Intelligent Optimization Algorithms such as the Ant Colony Algorithm (ACO) [

6] and Firefly Algorithm (FA) [

7]. However, their imbalance between global and local search capabilities leads to significant variations in performance across different environments [

8].

Classical path planning algorithms are based on explicit mathematical models and logical rules. Sampling-based methods randomly or semi-randomly sample in the solution space to find paths that satisfy specific conditions. The dynamic window approach (DWA) samples in the robot’s velocity space to generate optimal trajectories [

9], offering fast computation and ease of solving. However, it exhibits unstable planning efficiency across different maps and is unsuitable for car-like robots. Rapidly-exploring Random Tree Star (RRT*) relies on extensive sampling expansions. While it has strong problem-solving capabilities, it demands high computational effort, converges slowly, and generates paths that are not sufficiently smooth [

10].

Curve interpolation-based methods use mathematical functions to generate smooth paths, such as B-spline Curves [

11] and high-order Bezier Curves [

12]. However, these methods suffer from poor real-time performance and are more suitable for robots with simple constraints, showing suboptimal performance in car-like robots.

Optimization-based methods solve paths by defining a cost function to minimize the cost. The cost function typically considers multiple factors such as path length, smoothness, and safety. The Artificial Potential Field (APF) method is simple and efficient in computation but prone to path oscillation and local optima issues [

13].

Achieving path planning with real-time performance, smoothness, and obstacle avoidance remains challenging for car-like mobile robots under non-holonomic constraints. Traditional methods based on sampling, curve interpolation, and optimization each have their advantages and disadvantages but fail to balance path smoothness and computational efficiency in complex environments. The Timed-elastic-band (TEB) method proposed by Rosmann et al. [

14] transforms the path planning problem into a real-time multi-objective optimization problem, effectively integrating kinematic constraints and trajectory planning requirements. It efficiently generates optimal trajectories that conform to the motion characteristics of car-like robots, balancing trajectory smoothness, real-time performance, and obstacle avoidance. Compared to traditional Dubins curves and Reeds-Shepp curves, TEB not only exhibits comparable or equivalent results in trajectory optimization but also achieves superior performance in the time dimension [

15].

Sun et al. improved TEB for a specific kinematic model of a collaborative robot and further developed a motion control function to ensure stability and safety during operation [

16]. Hoang et al. incorporated human socio-temporal characteristics into the TEB algorithm to enable robots to plan trajectories more aligned with human intuition when avoiding people [

17]. Wu et al. incorporated the heuristic function of the A-star algorithm into TEB's objective function to generate trajectories along walls and near the edges of curved paths, reducing planning time [

18]. Zha et al. removed objective terms related to velocity and time information from TEB and added constraints for smoothness and curvature, subsequently applying fifth-order spline curves to smooth the trajectory, thereby improving trajectory smoothness [

19]. Wang et al. introduced a two-step TEB algorithm to filter and optimize rough global paths generated by MH-RRT, reducing the number of homotopy class paths requiring optimization and thereby lowering TEB's computational burden [

20]. Smith et al. addressed the decoupling between TEB's use of factor graphs as an optimization data structure in the G2O framework and the environmental data structures (e.g., costmap) in the navigation stack by proposing an Egocircle method for ego-centered obstacle representation and gap-based topological trajectory search to simplify TEB computations and enhance optimization efficiency [

21]. Liu et al. utilized the Random Sample Consensus (RANSAC) algorithm to simplify the contours of complex obstacles, reducing computational load and enabling more responsive and faster optimization [

22]. Nguyen et al. added potential collision information generated by the Hybrid Reciprocal Velocity Obstacle (HRVO) model as an objective term to TEB's objective function, enabling mobile robots to proactively predict the behavior of dynamic obstacles and enhancing TEB's optimization speed in dynamic scenarios [

23].

Despite its excellent tunability and optimization capabilities, the TEB method, widely applied in local path planning, still has certain limitations in practical applications:

Insufficient adaptability to different scenarios. The algorithm lacks the ability to self-adjust across varying environments, leading to suboptimal performance in dynamic or complex scenarios.

Conflicts in multi-objective optimization. Potential conflicts among multiple optimization objectives may cause the overall optimization result to deviate from the optimal solution, or even break certain soft constraints.

Lack of smooth control inputs. Frequent oscillations in orientation angles, velocity, and acceleration along the trajectory impact the robot's motion stability.

To address these issues, this paper proposes an improved TEB method based on fuzzy logic control (FLC-TEB, Fuzzy Logic Controller TEB), introducing new objective terms for trajectory smoothness and jerkiness in the TEB to reduce oscillations and dynamically adjusting the weights of objective terms based on environmental characteristics to enhance trajectory quality and algorithm robustness. The main contributions of this paper include:

Introducing new objective terms for trajectory smoothness and jerkiness into the classic TEB objective function. These improvements aim to enhance the overall smoothness of the trajectory, reduce drastic changes in velocity control, and thereby improve the robot's motion stability.

Designing fuzzy logic control rules to dynamically adjust the weights of objective terms in the TEB objective function through a fuzzy controller. This enables the improved TEB algorithm to optimize the priorities of different objectives in real time according to environmental changes, thereby significantly improving the quality of the overall trajectory.

The content of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 briefly introduces the classic Timed-Elastic-Band (TEB) method, analyzes the kinematic model of car-like mobile robots, and explains how the TEB algorithm incorporates kinematic constraints into the objective function.

Section 3 focuses on the improvements of adding trajectory smoothness and jerkiness objective terms into the classic TEB, along with the design of a fuzzy logic controller to dynamically adjust the weights of the objective terms to adapt to environmental changes.

Section 4 validates the effectiveness of the proposed FLC-TEB algorithm in local path planning for car-like robots through simulations and real-world experiments. Finally,

Section 5 summarizes the main conclusions of this paper and outlines future research directions.

3. Improved TEB Algorithm with Fuzzy Logic Controller

During local path optimization, the weights of the objective terms in the TEB algorithm significantly influence the actual optimization results. According to the quadratic penalty theory, the optimal solution

for the original nonlinear problem can only be achieved when all the objective term weights approach infinity(

) [

15]. Since excessively large weights can cause the solver to struggle with convergence, TEB employs a weight coefficient of 1 as the standard weight for each objective term. However, in different scenarios, the robot must consider varying priority objectives for the trajectory to reduce energy consumption and improve mobility efficiency.

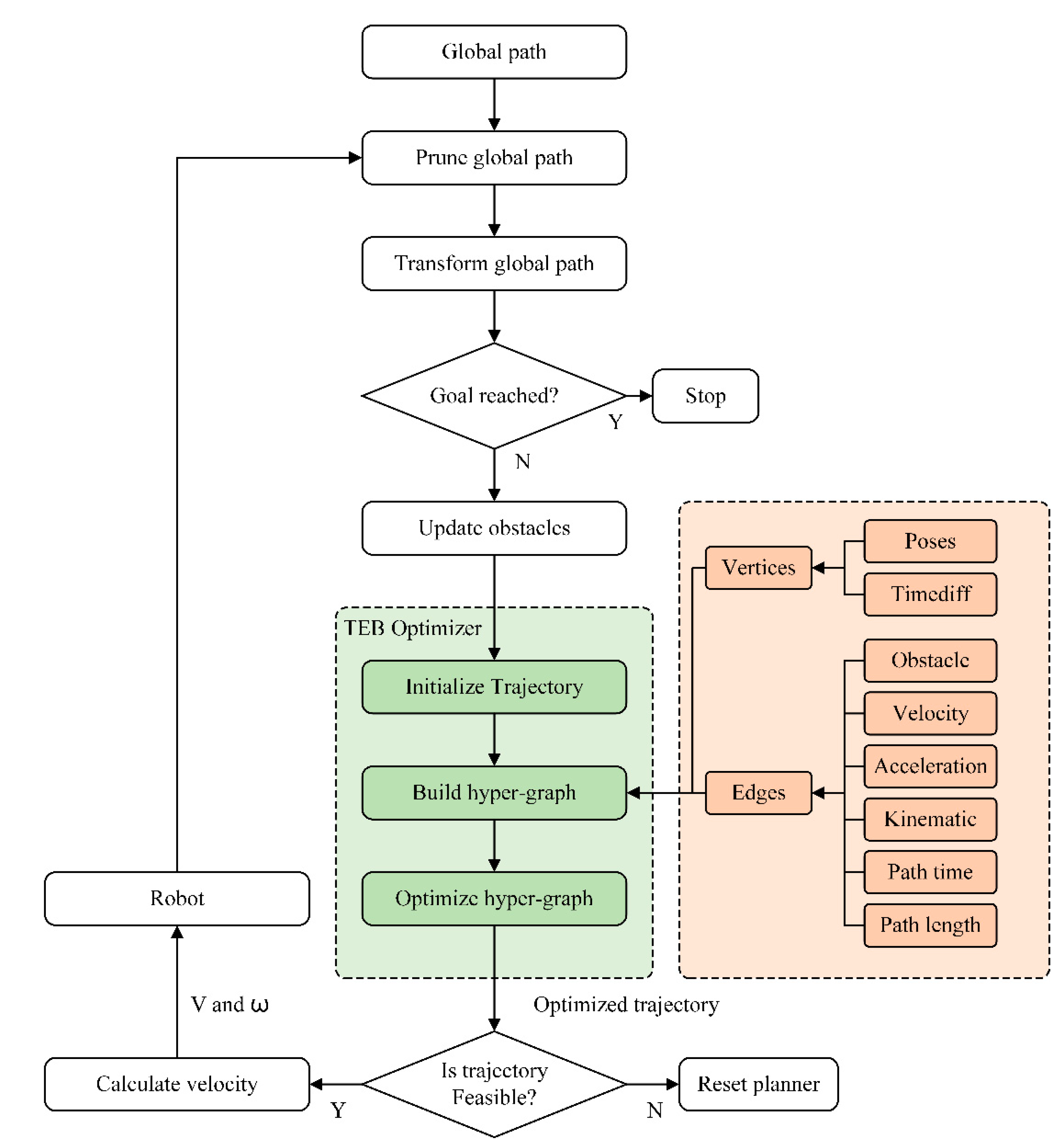

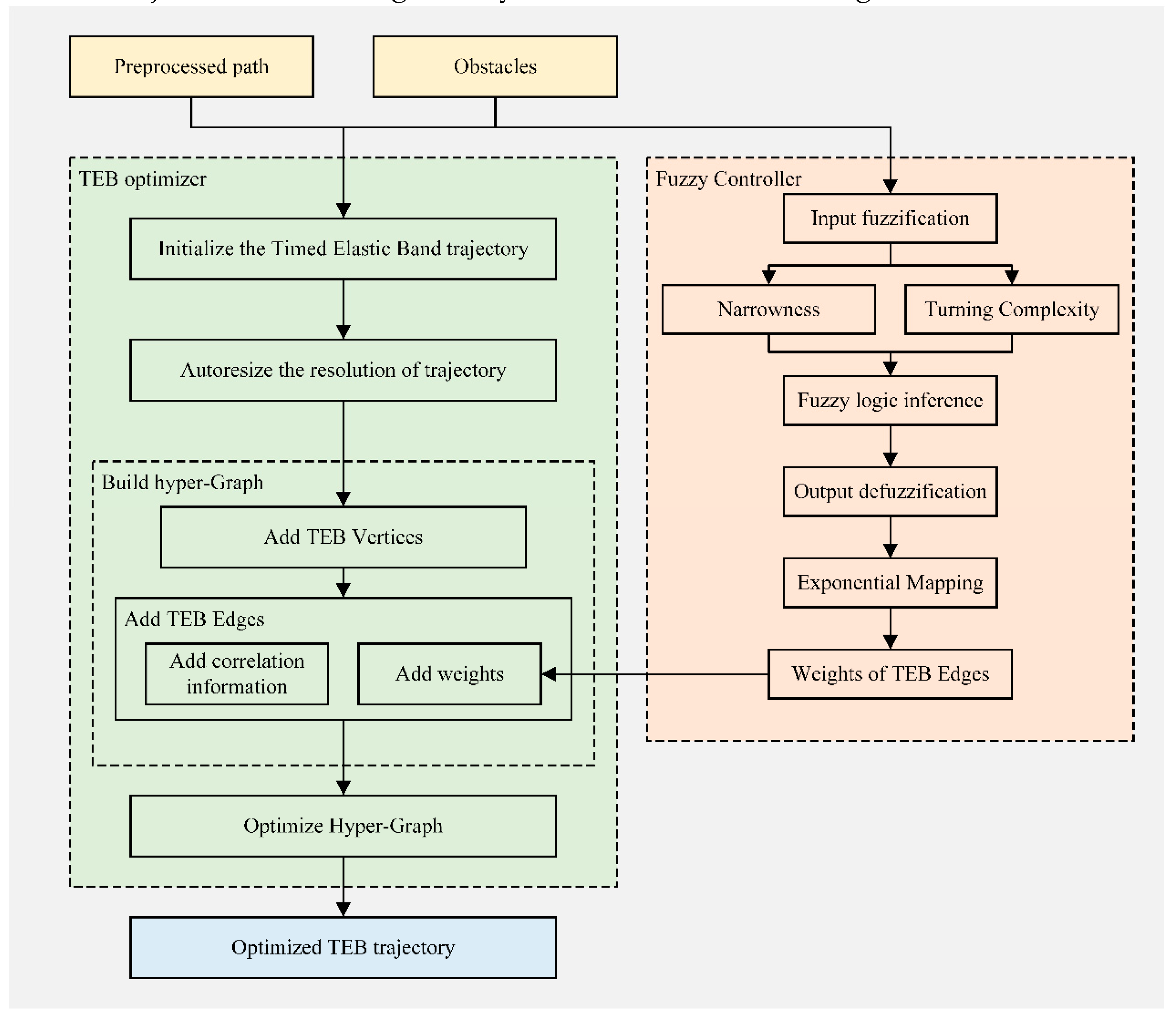

Therefore, new objective for trajectory smoothness and jerkiness are added to the objective function to achieve smoother trajectories and more stable velocity changes, and a fuzzy logic control method is introduced to enhance TEB's adaptability. The flowchart for dynamically adjusting the weights of TEB objective terms using a fuzzy controller is shown in

Figure 5:

3.1. TEB Objective Function Considering Robot Motion Smoothness

To address issues such as oscillations in velocity, angular velocity, and steering angles in TEB-based local path planning, smoothness and jerk [

26,

27] are incorporated into the TEB objective terms to reduce the robot's motion instability.

Trajectory smoothness is represented by the angular changes between adjacent pose points, as shown in Equation (10):

The Jerk is the derivative of acceleration and is calculated using the differences between four consecutive poses, as shown in Equation (11):

Therefore, penalty terms for trajectory smoothness and jerk, along with their corresponding weights, are added to Equation (9). These penalty terms are incorporated as hyperedges into the optimization framework of TEB, forming a new objective function:

3.2. Establishment of Fuzzy Rule Controller

The key to local path planning for car-like robots lies in effectively incorporating the constraints introduced by the kinematic model into the planning process. Non-holonomic constraints require replacing lateral translational motion with curved motion, while the minimum turning radius constraint further reduces the solution space for the path.

To improve the local path planning performance of car-like robots, this paper proposes using "freedom" and "directionality" to evaluate the trajectory characteristics of car-like mobile robots. Under non-holonomic and minimum turning radius constraints, the "freedom" of car-like mobile robot motion refers to the flexibility of pose adjustment, while "directionality" refers to the complexity of curved motion in the trajectory caused by non-holonomic constraints, replacing the need for lateral translation. To evaluate freedom, this paper uses the ratio of the average distance between the trajectory and obstacles to the minimum turning radius to measure the Narrowness () of the passage, which serves as an intuitive indicator of trajectory freedom; To evaluate directionality, this paper uses the proportion of different curvature arcs in the entire trajectory to quantify the turning complexity () of curved motion, which reflects the trajectory's directionality.

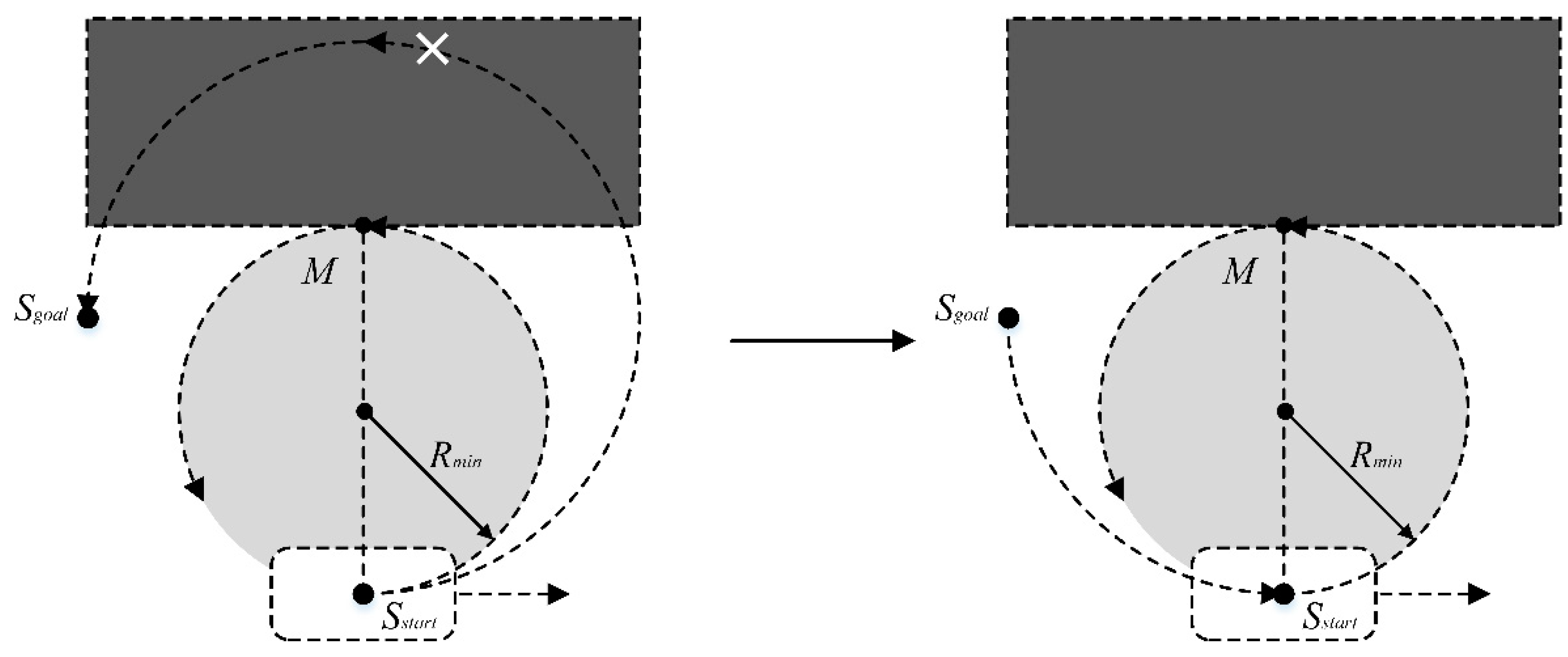

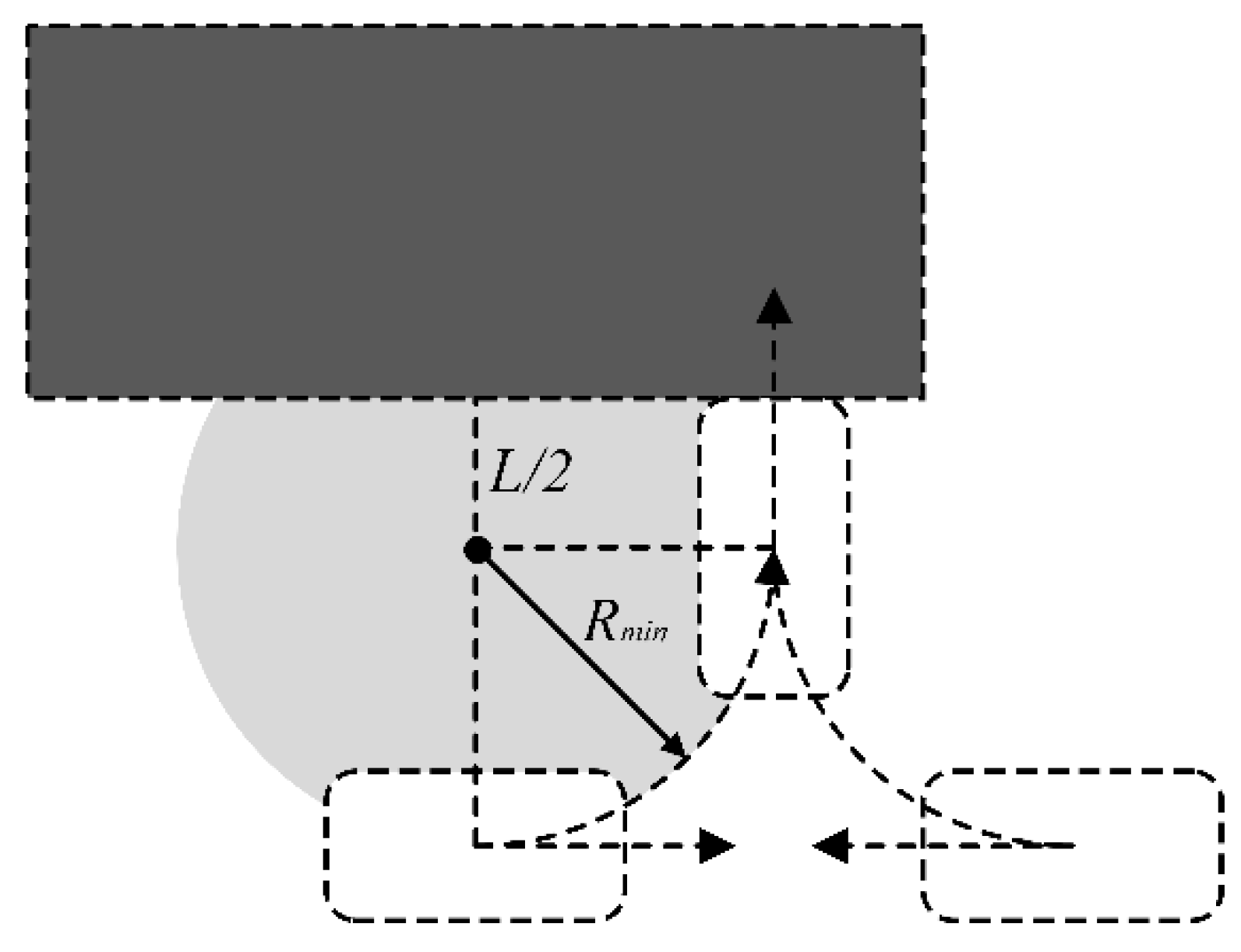

3.2.1. Freedom Evaluation

Due to the minimum turning radius constraint, car-like mobile robots have an inaccessible circular area on the side, and the planned path must circumvent this area. Within this area, the distance from any point to the kinematic center is

, the point furthest from the robot's kinematic center is

, with a distance of

from the kinematic center. As shown in

Figure 6, when there are obstacles outside point

, the robot cannot directly turn around to move toward a target point behind it. In this situation, the robot can only adjust its initial pose and move forward in the other direction before turning to indirectly approach the target point, or adopt a reversing strategy. However, to avoid instability, reversing behavior is usually subject to strict constraints [

28]. Therefore, when the distance on both sides of the robot in the passage is less than

, the solution space for navigable paths is significantly reduced.

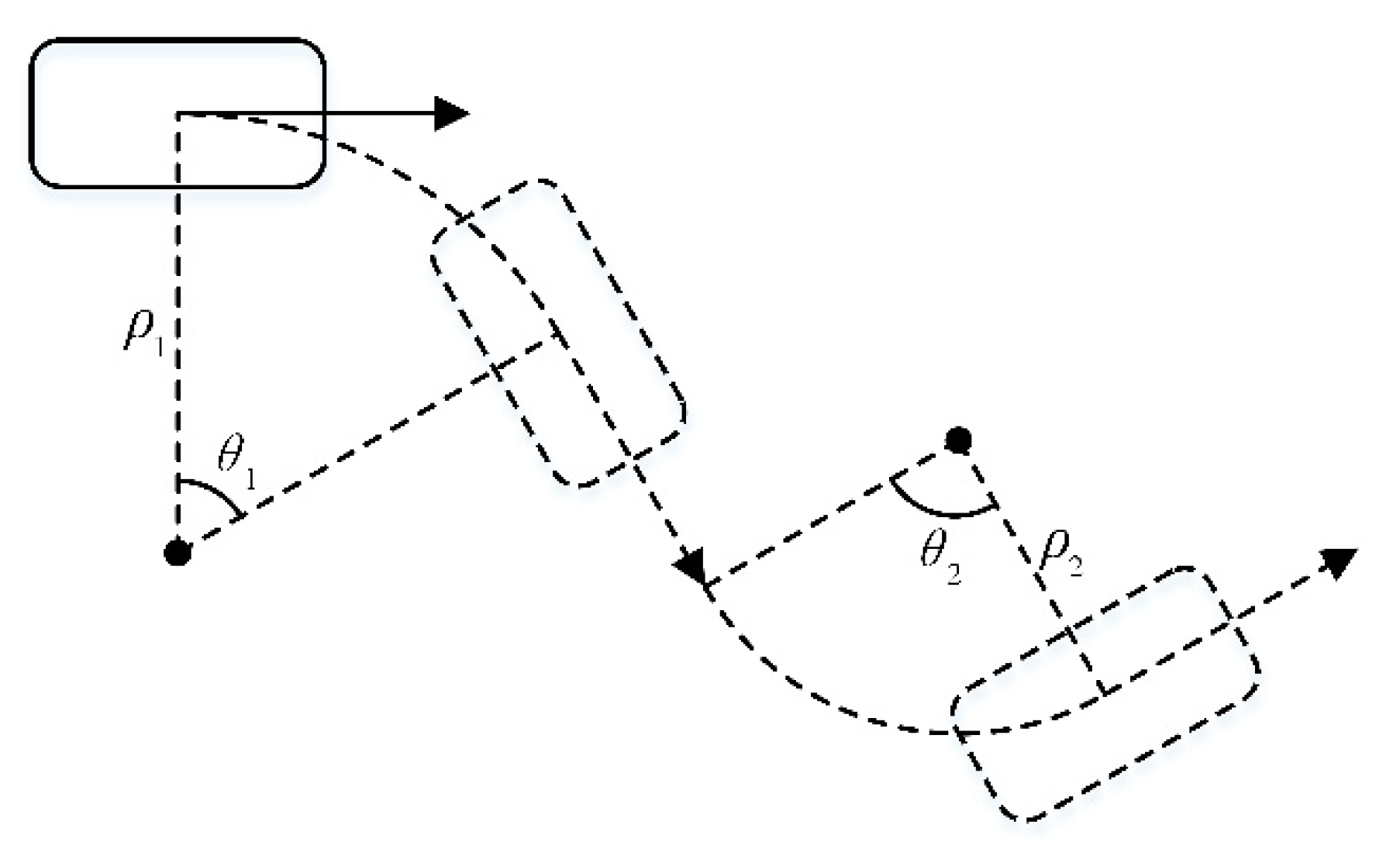

When the orientation of the target point's pose is opposite to the current pose, car-like mobile robots usually use curved motion to adjust the heading angle. As shown in

Figure 7, when the space around the robot is too narrow to plan a single curved trajectory to adjust the heading angle, the robot needs to use a combination of forward and backward movements to achieve heading angle adjustment. When the distance between the obstacle and the robot,

, is less than

, the robot cannot adjust its heading angle by 180° using a single forward and backward combination movement, significantly increasing the complexity of pose adjustment. This limitation further reduces the solution space for path planning, constraining effective motion options.

Therefore, the adjustability of car-like mobile robot poses is evaluated using the narrowness (

) of the passage where the trajectory lies.

is determined by the relationship between the average distance,

, between all robot poses along the trajectory and the nearest obstacle, and the minimum turning radius

. Assuming the semi-axle length of the car-like mobile robot satisfies

, and there are n trajectory points

in the trajectory, with the average distance to the nearest obstacle

,

is calculated as:

3.2.2. Directionality Evaluation

Due to non-holonomic kinematic constraints, the motion trajectory of car-like mobile robots requires curved motion instead of lateral translation, and an increase in curved motion raises the complexity of the trajectory. Additionally, the greater the curvature of the curved trajectory, the higher the demands on the robot's motion control inputs. Therefore, the complexity of curved motion for car-like mobile robots is evaluated using the Turning Complexity (). is derived from the proportion of trajectory segments with different curvatures relative to the total.

For each local trajectory generated by the local planner, the curvature change between each pair of consecutive poses is first calculated, where is the heading angle change between adjacent poses and , and is the length of the corresponding trajectory segment. If the curvature exceeds the turning threshold , the trajectory between and is labeled as a turning segment; otherwise, it is labeled as a non-turning segment.

Next, turning segments are identified as sharp turning segments. If the curvature

of a turning segment exceeds the sharp turning threshold

but is less than

, the segment is classified as a sharp turning segment, where

is the curvature corresponding to the minimum turning radius

of the car-like robot, given by

. In this paper,

and

. Trajectory segments identified as sharp turning segments are not counted again as turning segments. If the trajectory contains n trajectory points

, it consists of n-1 segments. Let the number of turning segments be

and the number of sharp turning segments be

. The turning complexity

is defined as:

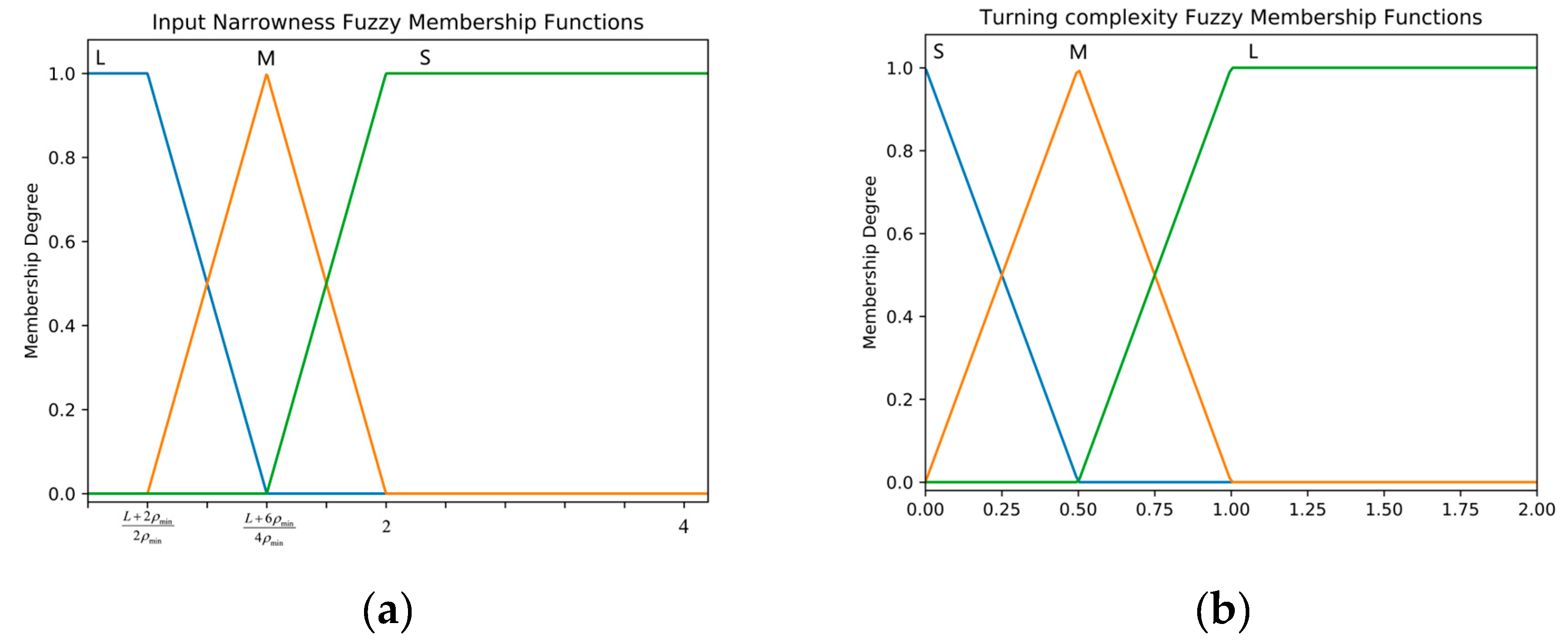

3.2.3. Establishment of Fuzzy Rules

Fuzzy logic control is a rule-based control method. Compared to other control methods, it can simulate human reasoning through linguistic control without requiring a precise mathematical model, offering greater fault tolerance, robustness, and simplicity [

29]. This paper considers the freedom and directionality of robot motion to set corresponding fuzzy logic control rules and establish a fuzzy controller for dynamically adjusting parameters.

The domain of narrowness is [0, 4], with a fuzzy set of [S, M, L]. The membership function of narrowness (

) is shown in

Figure 9(a). The domain of turning complexity is [0, 2], with a fuzzy set of [S, M, L]. The membership function of turning complexity (

) is shown in

Figure 9(b).); (

b) Membership function graph for the complexity of turns (

).

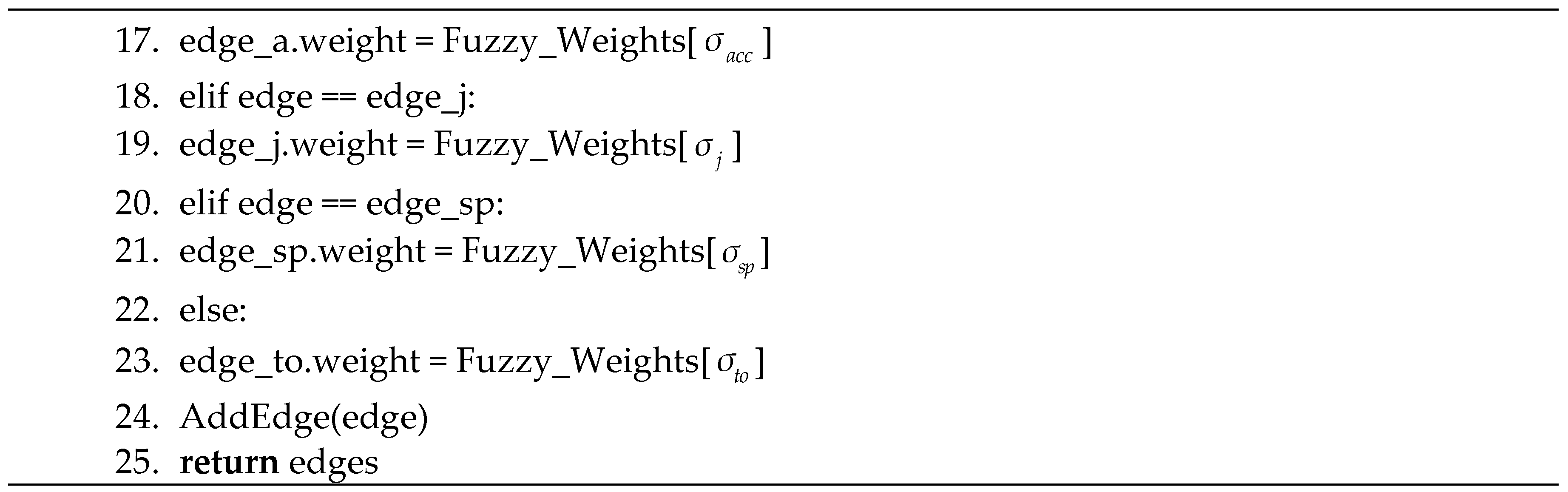

Based on the above fuzzy logic control rules, using fuzzy logic control to build TEB graph edges is as follows:

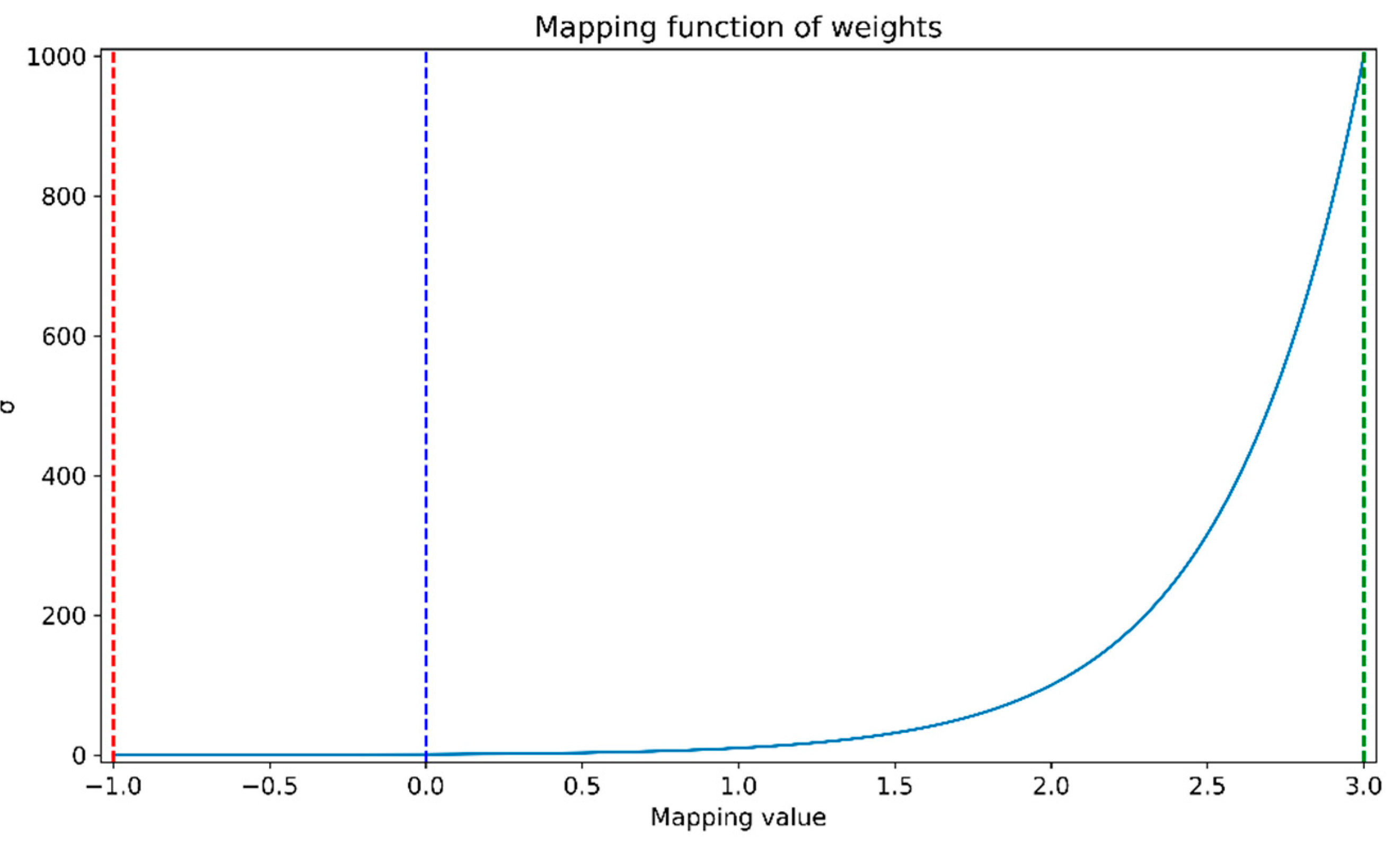

3.3. Nonlinear Mapping Strategy for Output Weight Values

The increase in penalty function weight coefficients has a nonlinear effect on optimization results, typically following a pattern close to logarithmic growth. Therefore, to simplify computation and improve the performance of the fuzzy controller, the inputs to the fuzzy controller are represented as a linear set, and a piecewise function is used to map the inputs to weight values. As shown in

Figure 10, the output range of the fuzzy controller, denoted as

, is [-1,3], and the real weight values, denoted as

, obtained through piecewise function mapping, fall within the range [0, 1000].

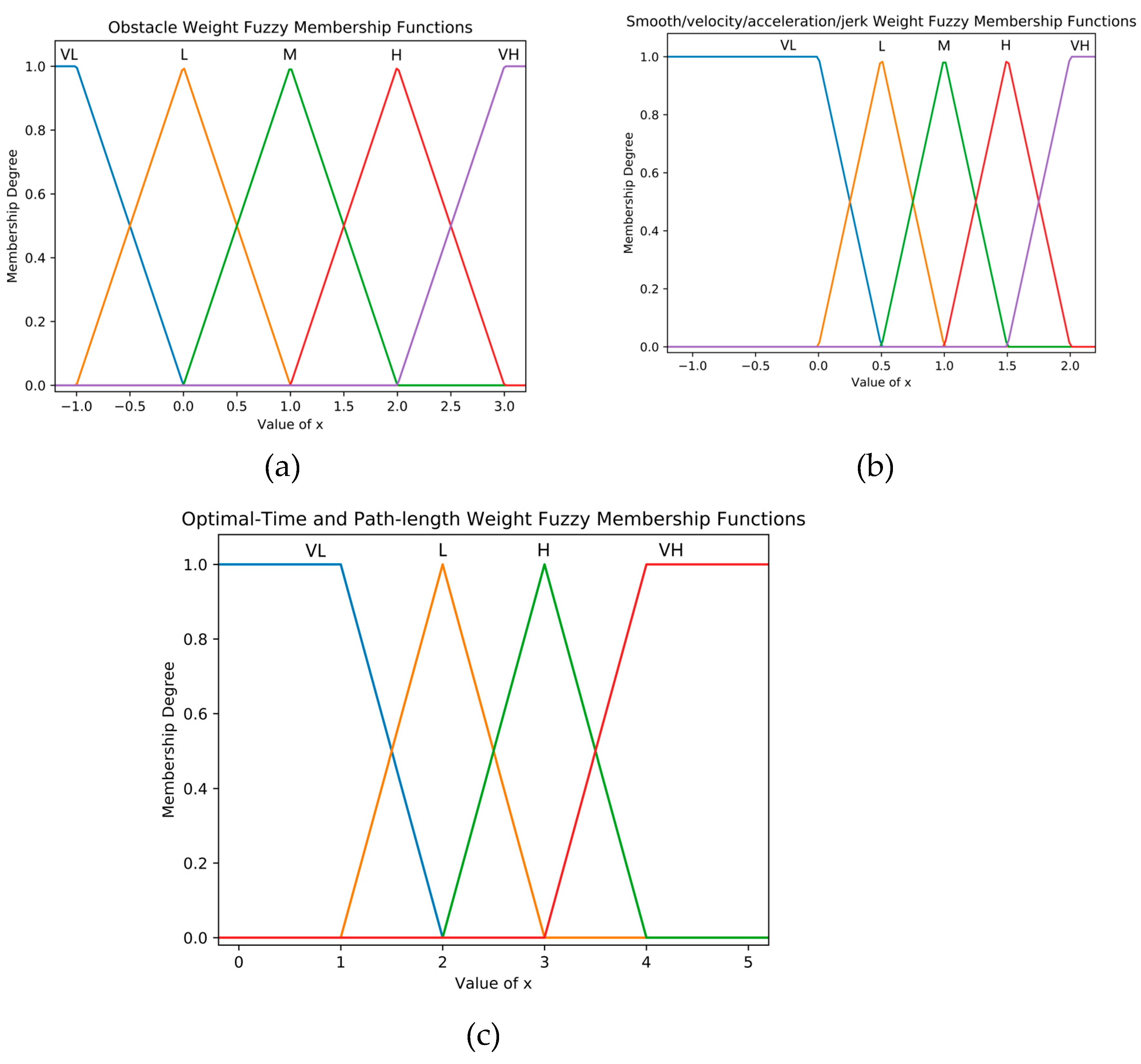

The membership function for the output weights of the fuzzy controller is shown in

Figure 11. The weight ranges for objectives related to obstacle distance, smoothness, velocity, acceleration, and jerk are mapped using piecewise functions. Specifically, the fuzzy output range for obstacle distance is [-1, 3], corresponding to a weight range of

, with a fuzzy set of [VL,L,M,H,VH]. Since the weights for optimal time and shortest path length should not be too large, these objectives are not linearized, and their corresponding weight range is set to

, with a fuzzy set of [VL, L, H, VH].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.C. and R.L.; methodology, R.L., L.C. and D.J.; software, R.L., G.M. and S.X.; validation, D.J., R.L. and S.X.; formal analysis, G.M.; investigation, G.M. and S.X.; resources, G.M. and S.X.; data curation, D.J. and R.L.; writing—original draft preparation, R.L. and L.C.; writing—review and editing, R.L. and L.C.; visualization, G.M. and S.X.; supervision, L.C.; project administration, S.X.; funding acquisition, L.C., G.M. and S.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

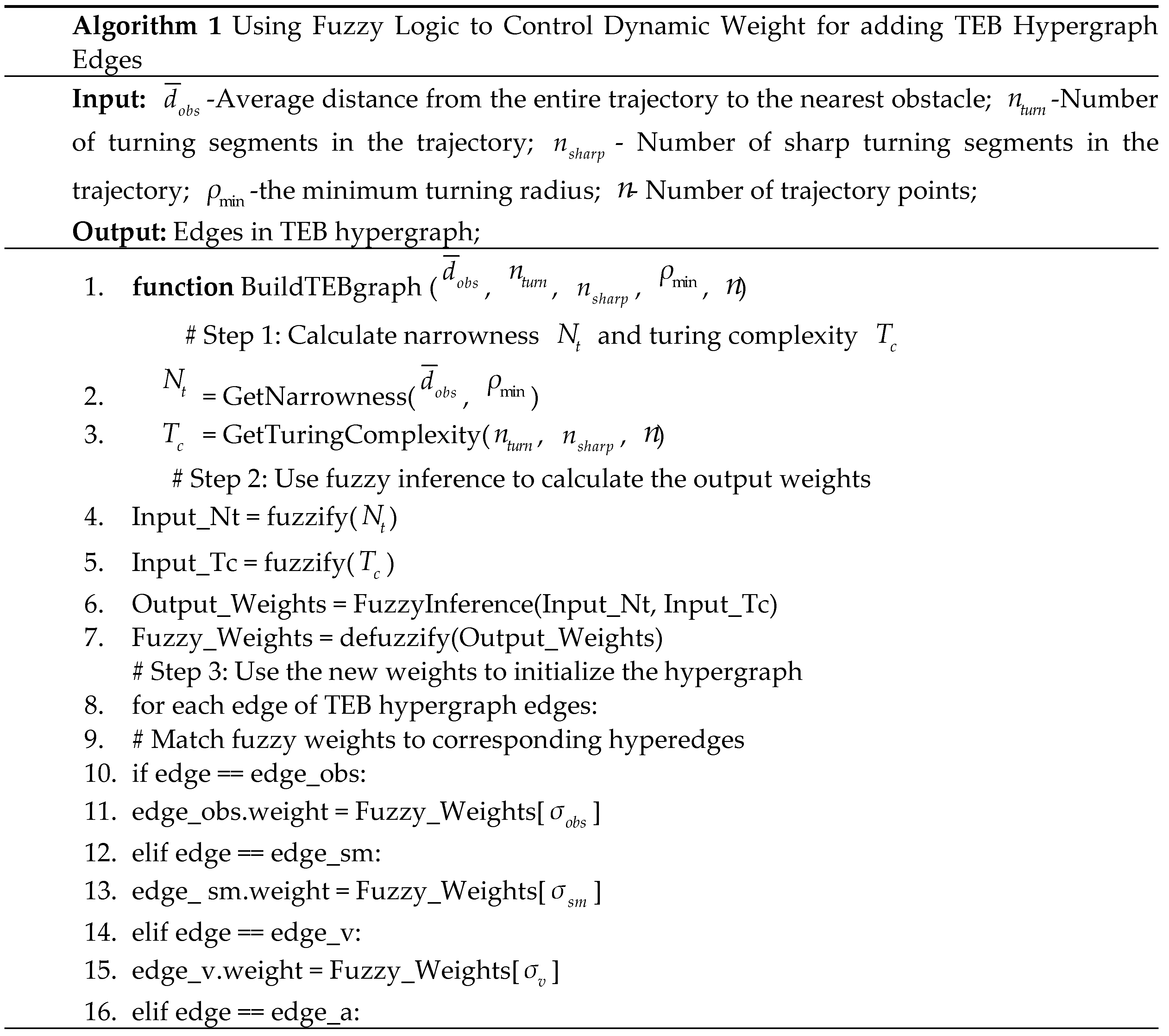

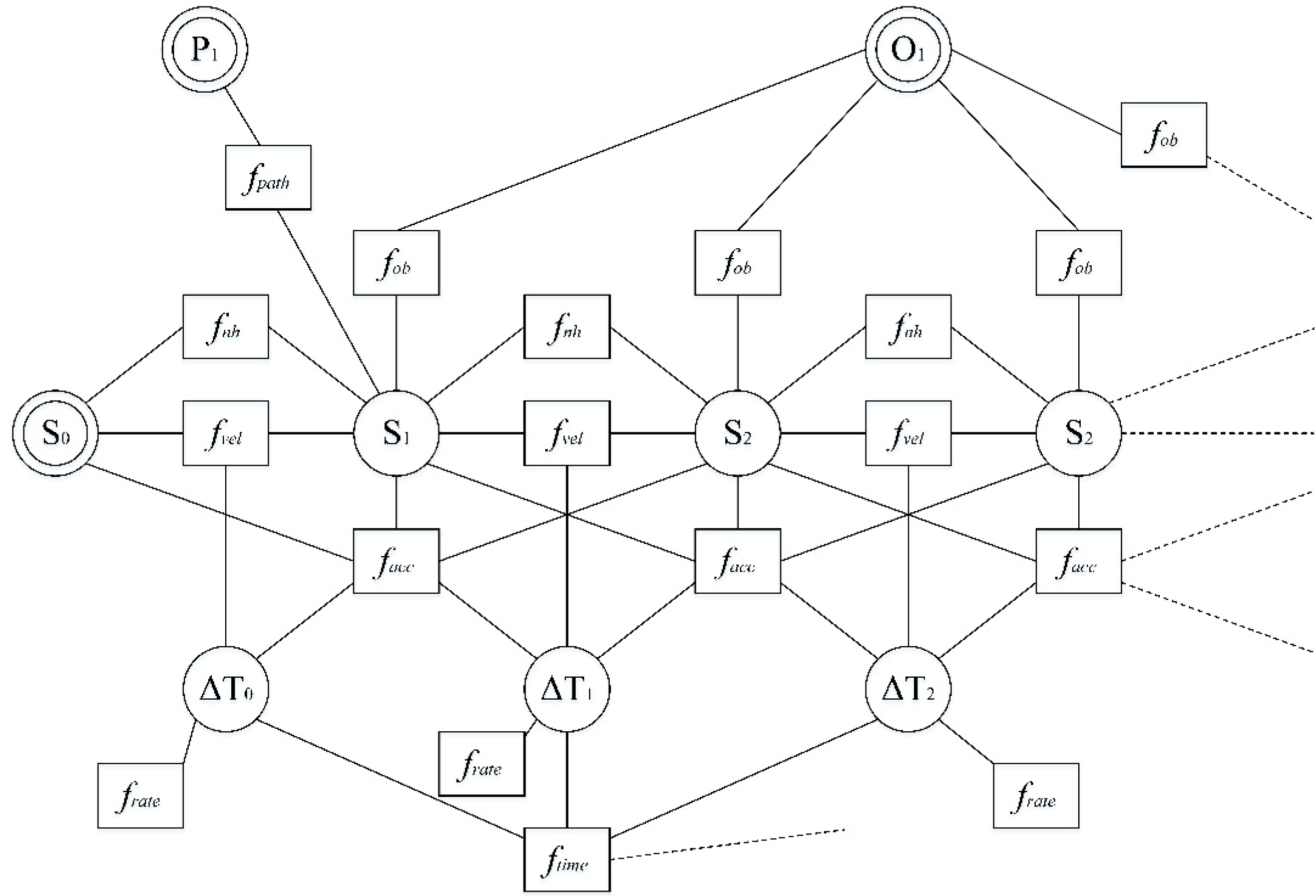

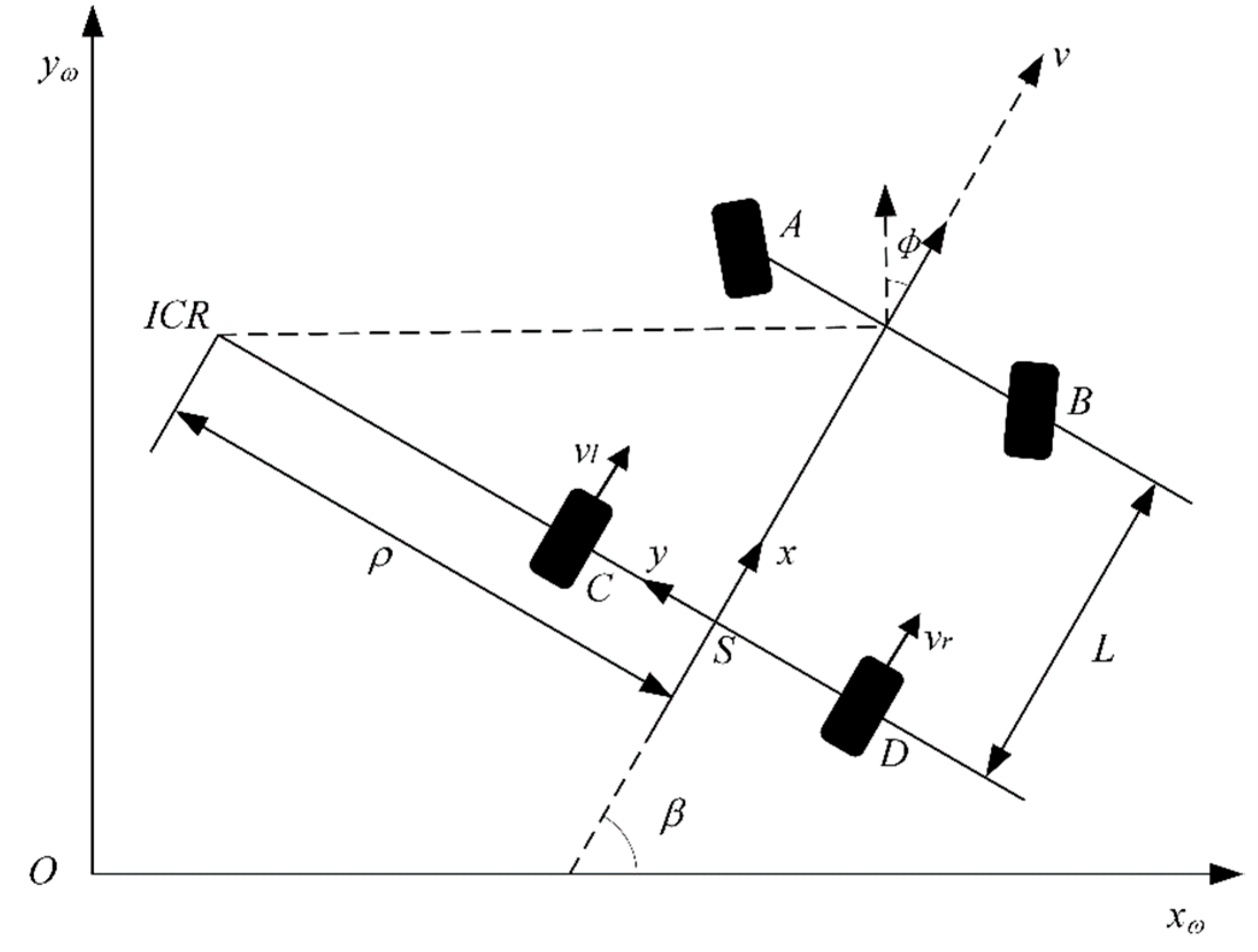

Figure 1.

TEB uses a hypergraph to represent the nonlinear optimization problem.

Figure 1.

TEB uses a hypergraph to represent the nonlinear optimization problem.

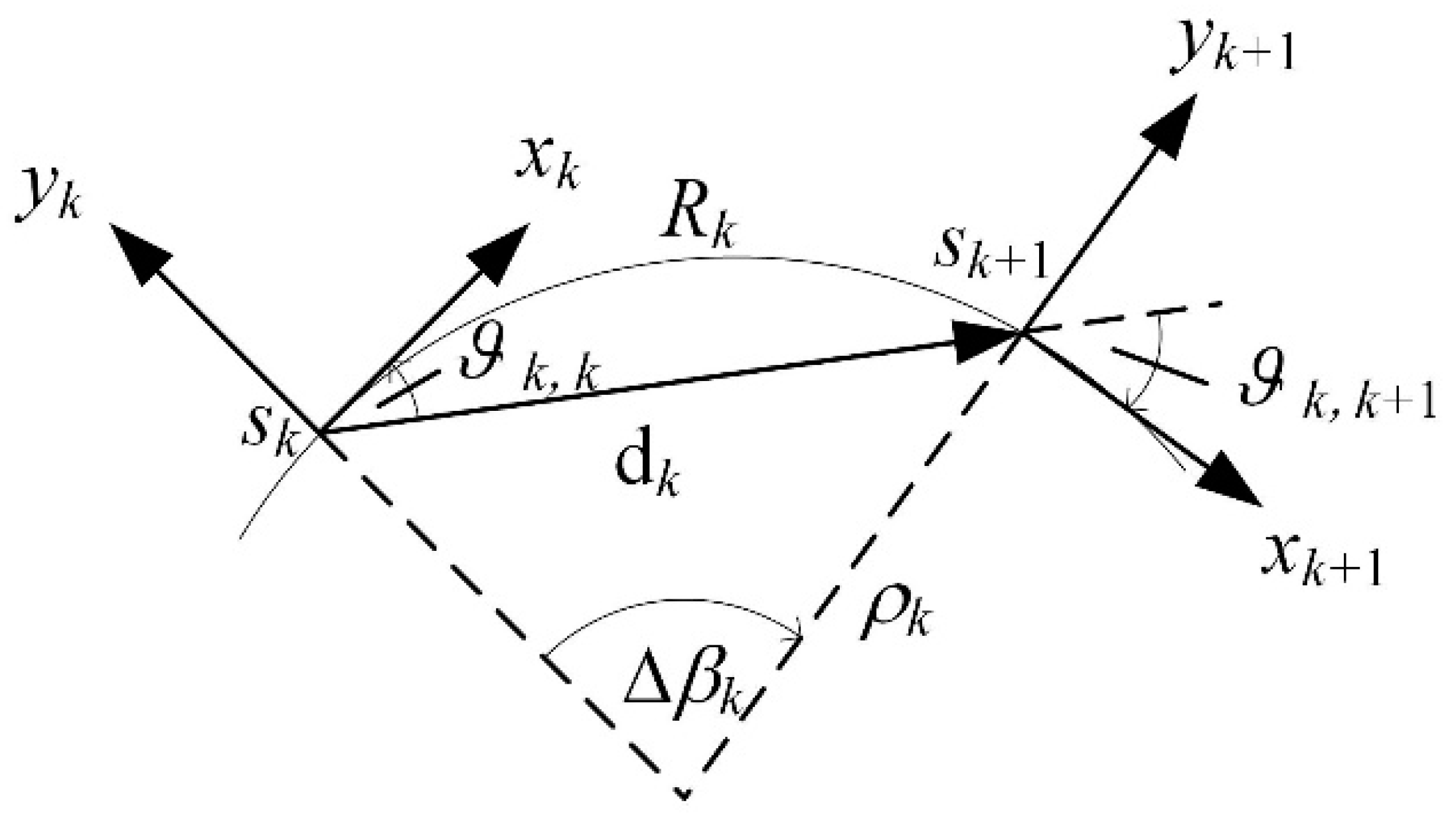

Figure 2.

Timed elastic band local planner.

Figure 2.

Timed elastic band local planner.

Figure 3.

The kinematic model of car-like mobile robots.

Figure 3.

The kinematic model of car-like mobile robots.

Figure 4.

Non-holonomic constraints of car-like mobile robots.

Figure 4.

Non-holonomic constraints of car-like mobile robots.

Figure 5.

TEB Algorithm Using Fuzzy Controller to Dynamically Adjust Objective Term Weights.

Figure 5.

TEB Algorithm Using Fuzzy Controller to Dynamically Adjust Objective Term Weights.

Figure 6.

The minimum turning radius limits the solution space of feasible paths for car-like robots.

Figure 6.

The minimum turning radius limits the solution space of feasible paths for car-like robots.

Figure 7.

The car-like robot uses a combination of backward and forward movements to adjust its orientation.

Figure 7.

The car-like robot uses a combination of backward and forward movements to adjust its orientation.

Figure 8.

A car-like mobile robot performs continuous turning movements along a trajectory.

Figure 8.

A car-like mobile robot performs continuous turning movements along a trajectory.

Figure 9.

(a) Membership function graph for the narrowness (

Figure 9.

(a) Membership function graph for the narrowness (

Figure 10.

Weight coefficients are mapped using piecewise functions.

Figure 10.

Weight coefficients are mapped using piecewise functions.

Figure 11.

Output weight membership functions: (a) Obstacle weight fuzzy membership function; (b) Smooth/velocity/acceleration/jerk weight fuzzy membership function; (c) Optimal time/shortest path weight fuzzy membership function.

Figure 11.

Output weight membership functions: (a) Obstacle weight fuzzy membership function; (b) Smooth/velocity/acceleration/jerk weight fuzzy membership function; (c) Optimal time/shortest path weight fuzzy membership function.

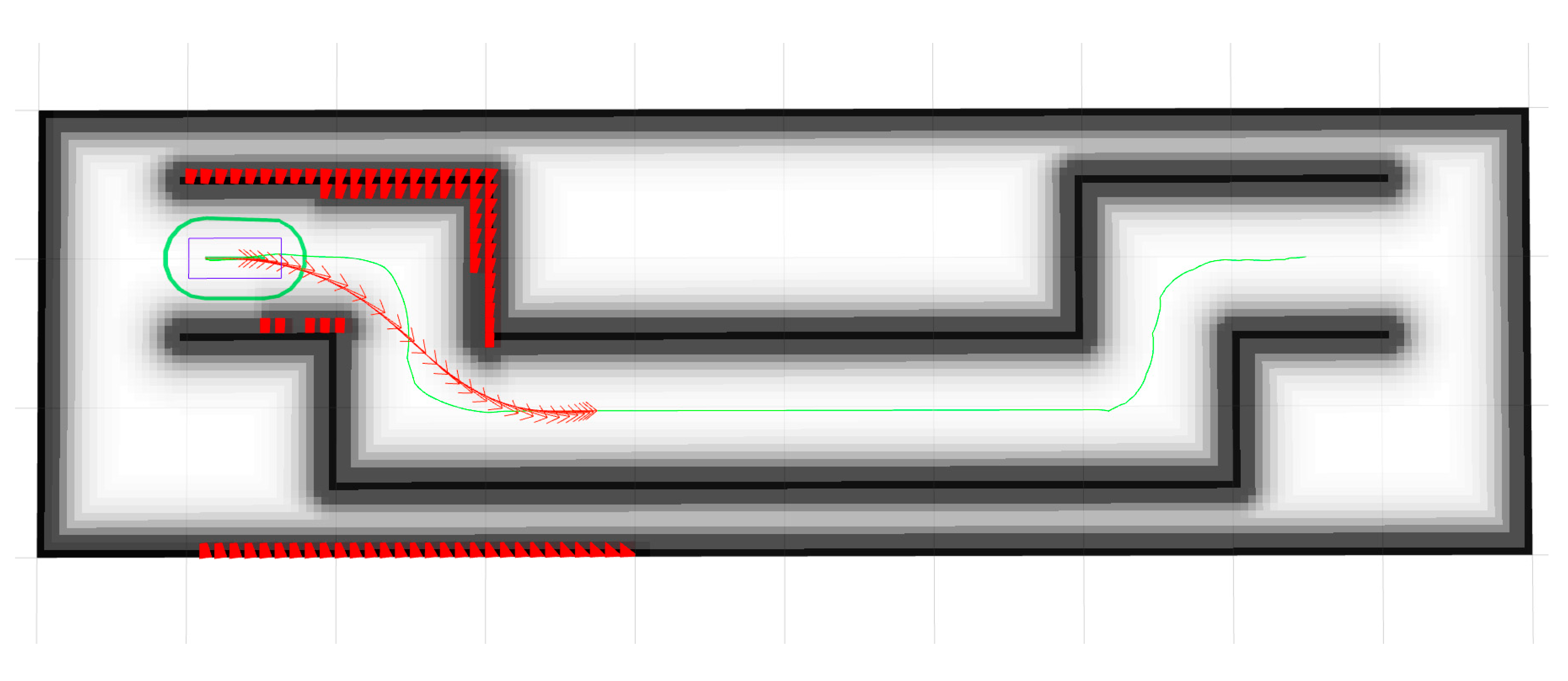

Figure 12.

A car-like robot modeled using a polygonal model moving through a narrow corridor with multiple corners. The green curve represents the global path, the red curve represents the motion trajectory, and the arrows indicate the heading angles at the trajectory points.

Figure 12.

A car-like robot modeled using a polygonal model moving through a narrow corridor with multiple corners. The green curve represents the global path, the red curve represents the motion trajectory, and the arrows indicate the heading angles at the trajectory points.

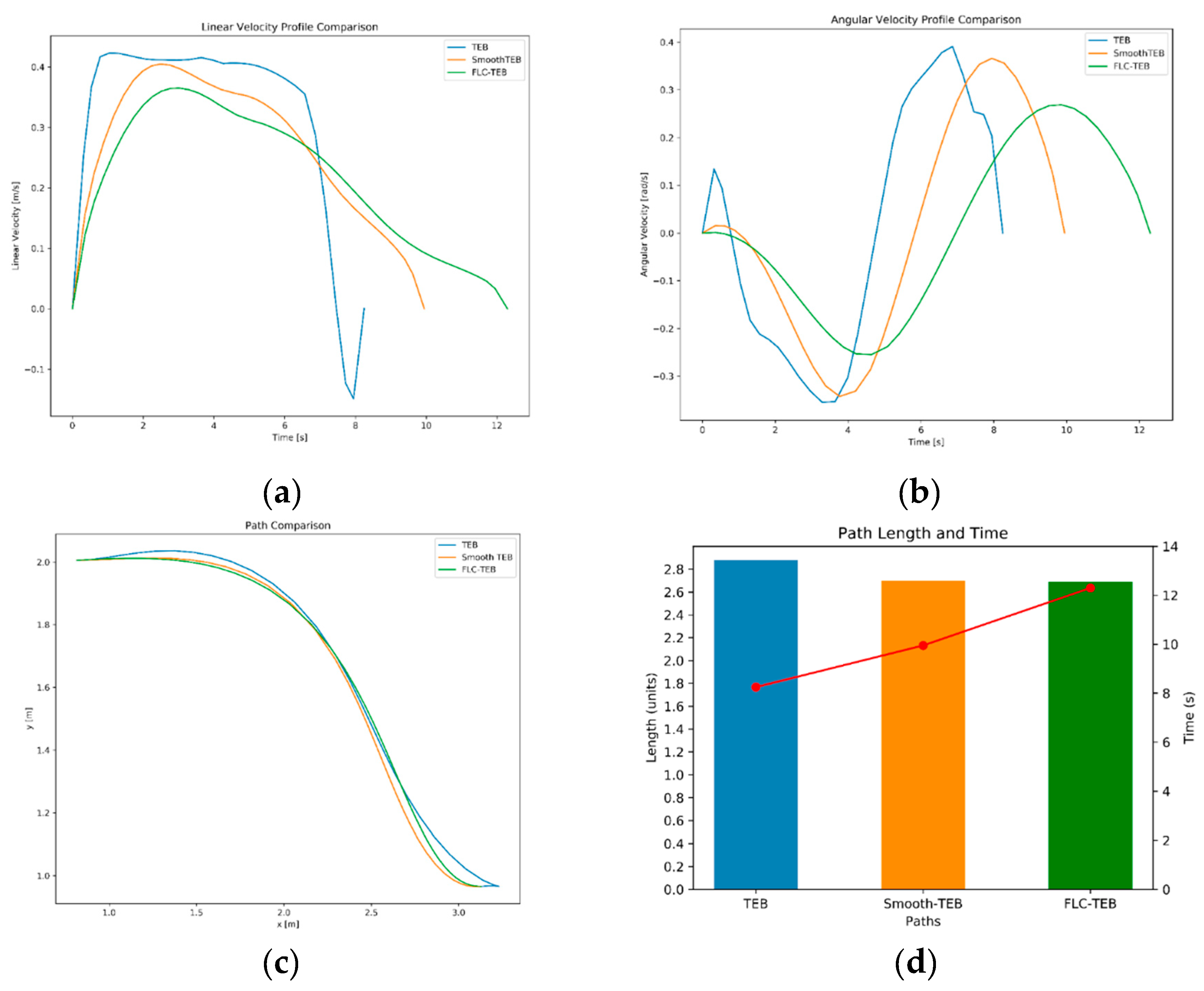

Figure 13.

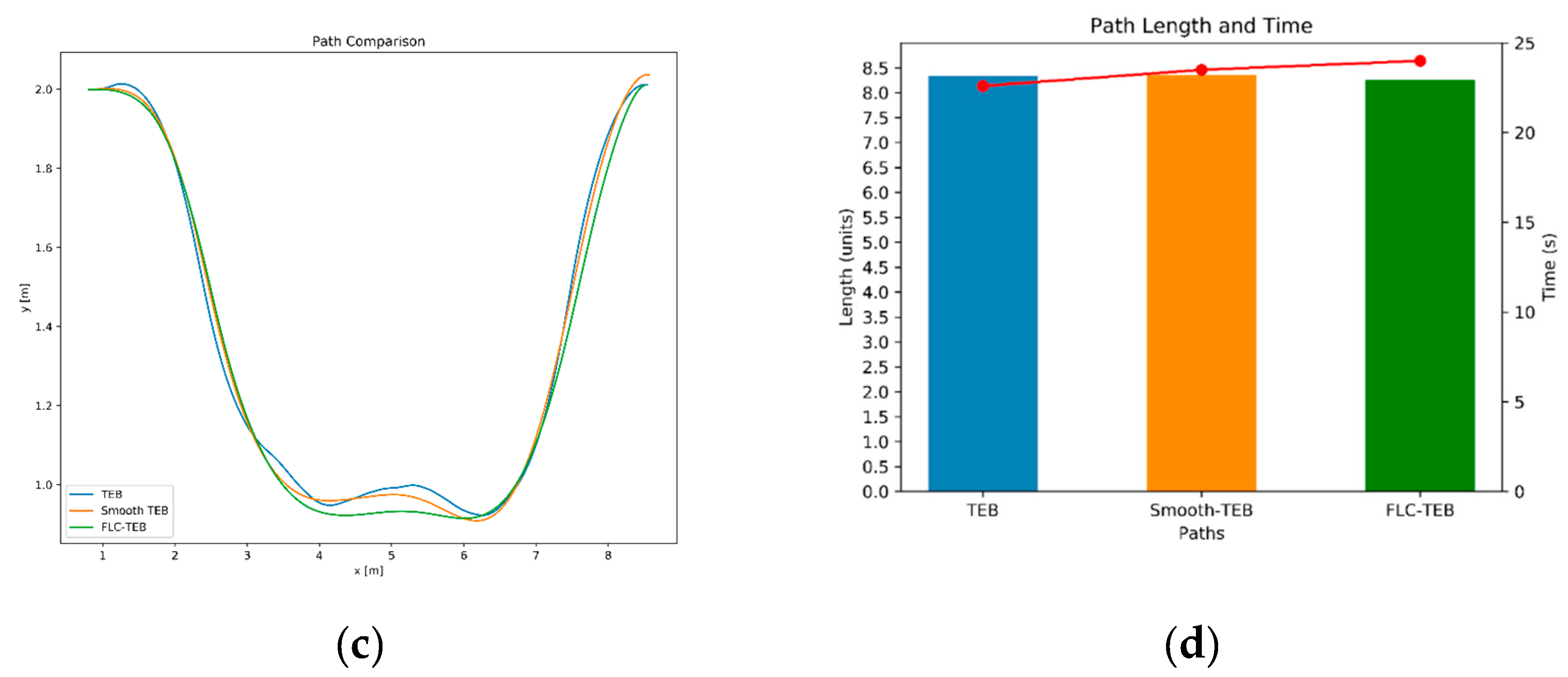

Comparison of TEB, Smooth-TEB, FLC-TEB in Sim Map1:(a) Linear velocity comparison; (b) Angular velocity comparison; (c) Path comparison; (d) Path length and duration comparison.

Figure 13.

Comparison of TEB, Smooth-TEB, FLC-TEB in Sim Map1:(a) Linear velocity comparison; (b) Angular velocity comparison; (c) Path comparison; (d) Path length and duration comparison.

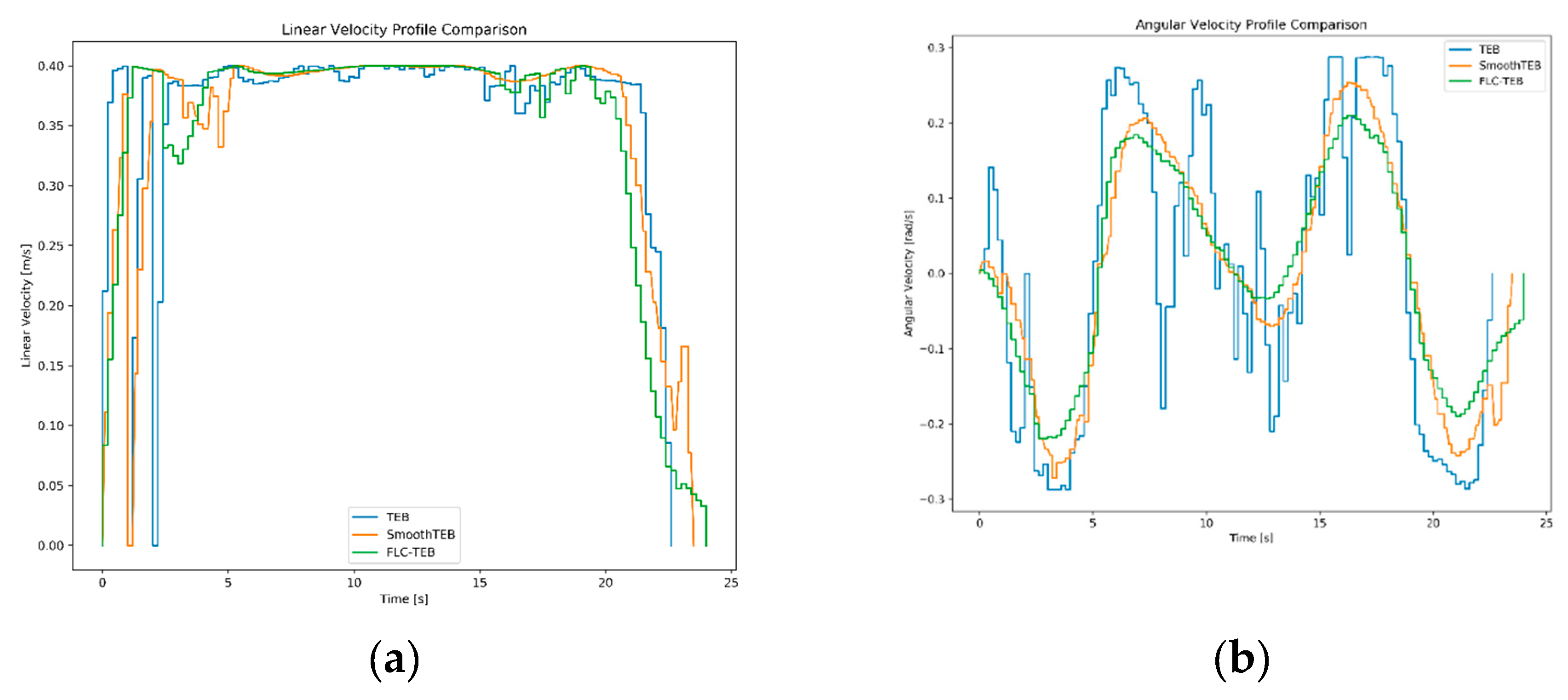

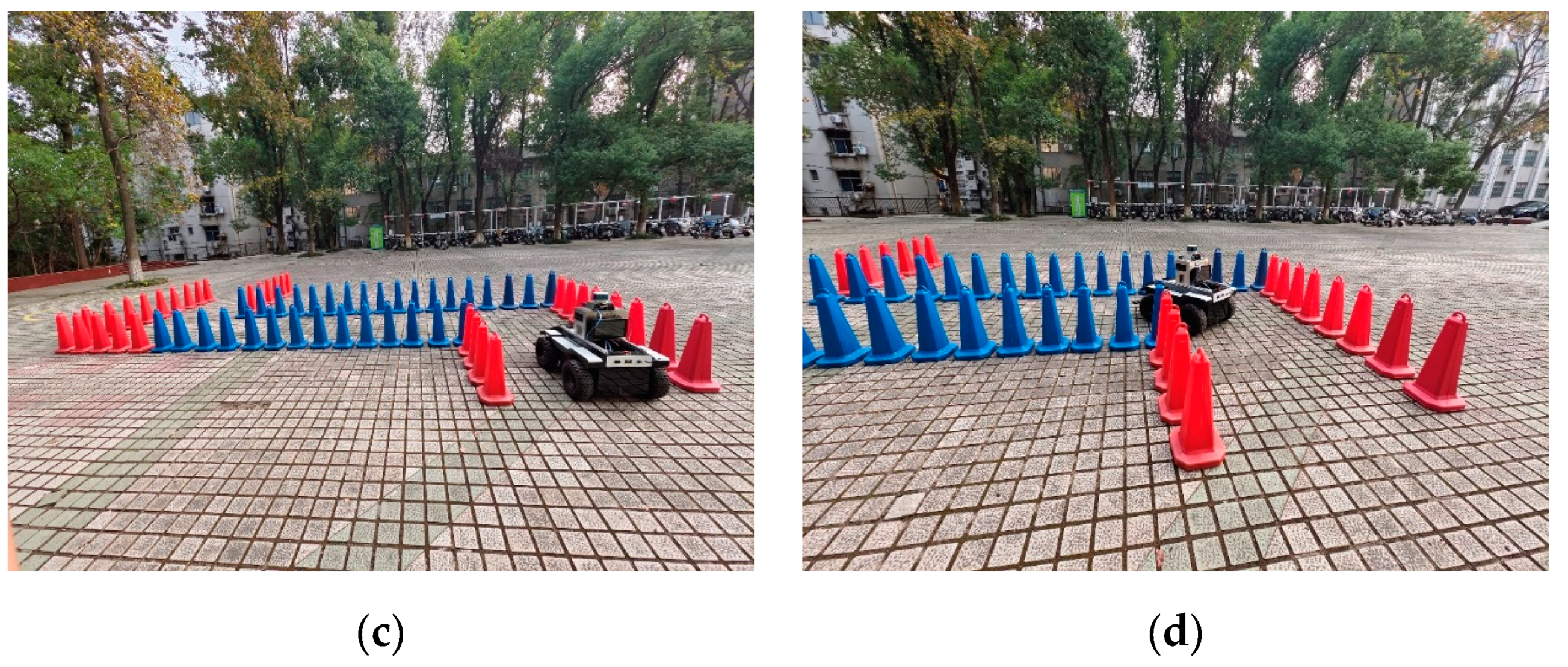

Figure 14.

Comparison of TEB, Smooth TEB, FLC-TEB in Complete Sim Map: (a) Linear velocity comparison. (b) Angular velocity comparison. (c) Path comparison. (d) Path length and duration comparison.

Figure 14.

Comparison of TEB, Smooth TEB, FLC-TEB in Complete Sim Map: (a) Linear velocity comparison. (b) Angular velocity comparison. (c) Path comparison. (d) Path length and duration comparison.

Figure 15.

The Car-like robot used in this paper.

Figure 15.

The Car-like robot used in this paper.

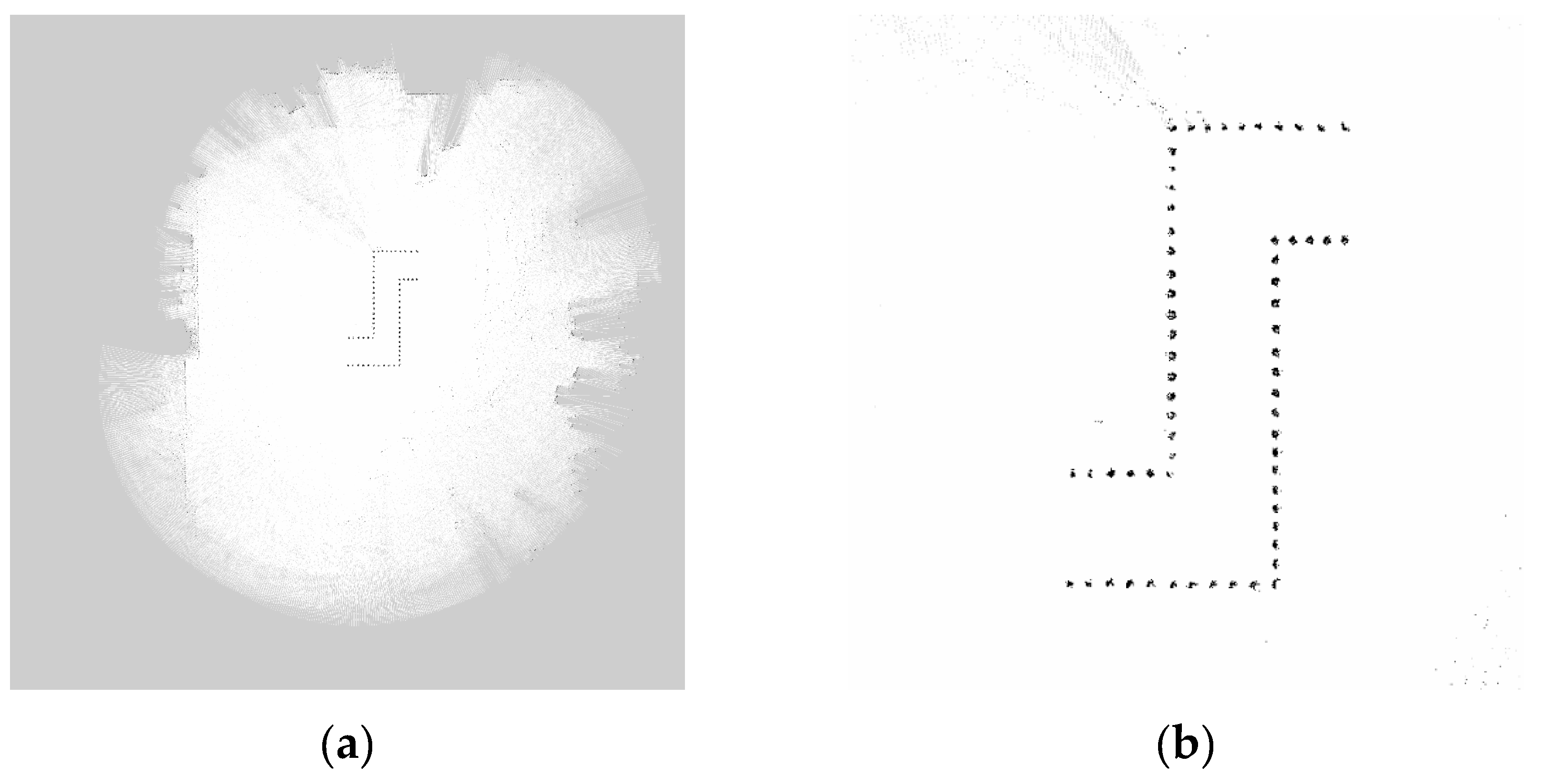

Figure 16.

Map built using SLAM in real car-like robot tests: (a) Map of an open area inside a campus. (b) The actual driving area on the map. (c) (d) Images from the real car-like robot during the test drive.

Figure 16.

Map built using SLAM in real car-like robot tests: (a) Map of an open area inside a campus. (b) The actual driving area on the map. (c) (d) Images from the real car-like robot during the test drive.

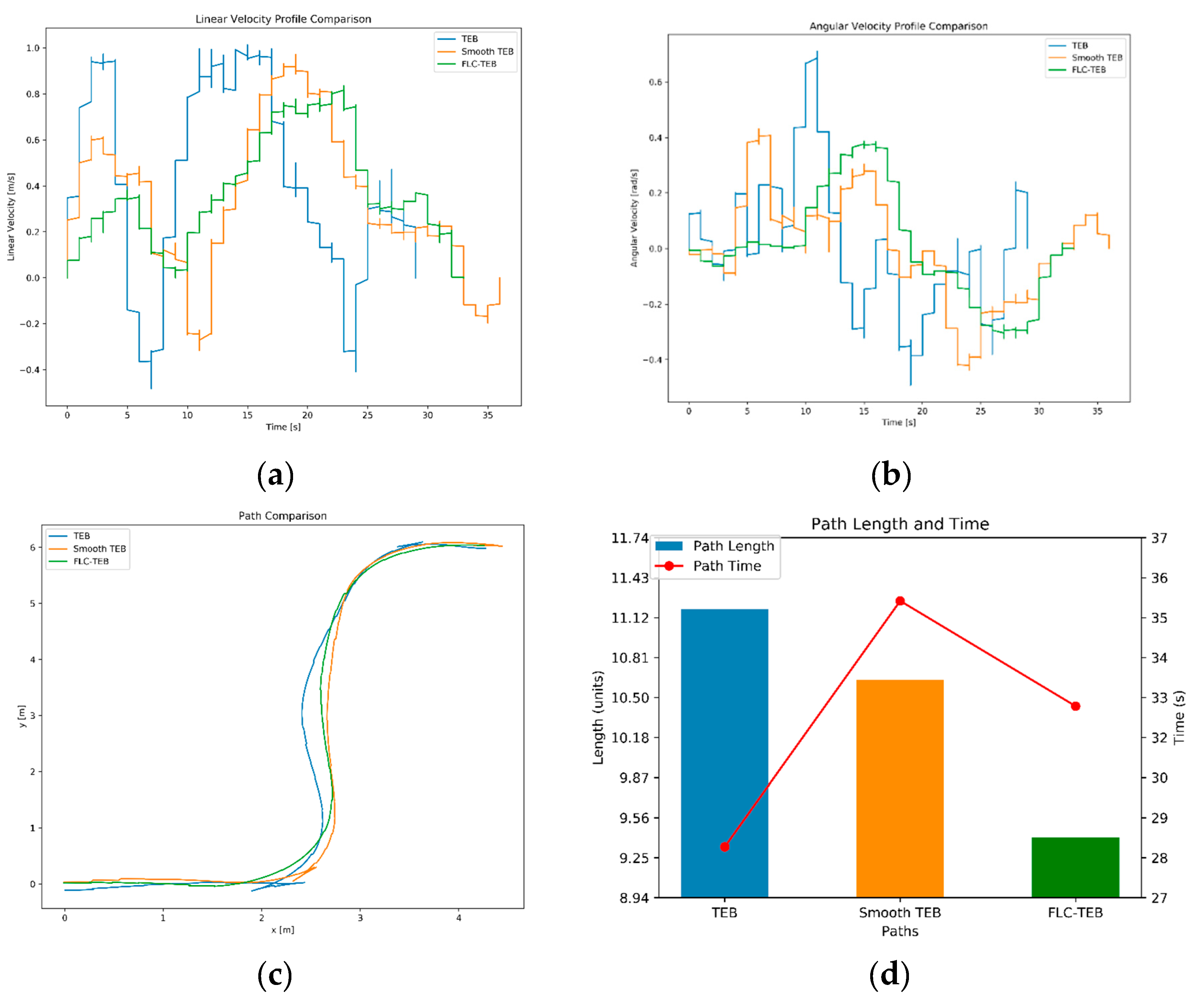

Figure 17.

Comparison of TEB, Smooth TEB, FLC-TEB in Real Car-like robot Test Map : (a) Linear velocity comparison. (b) Angular velocity comparison. (c) Path comparison. (d) Path length and duration comparison.

Figure 17.

Comparison of TEB, Smooth TEB, FLC-TEB in Real Car-like robot Test Map : (a) Linear velocity comparison. (b) Angular velocity comparison. (c) Path comparison. (d) Path length and duration comparison.

Table 1.

Fuzzy Logic Control Rule Table.

Table 1.

Fuzzy Logic Control Rule Table.

| No. |

Input |

|

Output |

| |

|

|

|

|

(linear) |

(angular) |

|

|

| 1 |

S |

S |

L |

L |

L |

VL |

H |

VH |

| 2 |

S |

M |

L |

L |

L |

VL |

L |

H |

| 3 |

S |

L |

M |

M |

L |

L |

VL |

L |

| 4 |

M |

S |

M |

L |

M |

VL |

L |

H |

| 5 |

M |

M |

M |

L |

M |

VL |

L |

L |

| 6 |

M |

L |

H |

M |

M |

L |

VL |

L |

| 7 |

L |

S |

H |

L |

H |

L |

L |

L |

| 8 |

L |

M |

H |

M |

H |

L |

VL |

L |

| 9 |

L |

L |

VH |

H |

H |

M |

VL |

L |

Table 2.

The kinematic parameters used for this car-like robot.

Table 2.

The kinematic parameters used for this car-like robot.

| Parameters |

Values |

| Maximum linear velocity(m/s) |

0.4 |

| Maximum linear backwards velocity(m/s) |

0.2 |

| Maximum angular velocity(m/s) |

0.3 |

| Maximum linear acceleration(m/s2) |

0.5 |

| Maximum angular acceleration(m/s2) |

0.5 |

| Maximum linear jerk(m/s3) |

0.1 |

| Maximum angular jerk(m/s3) |

0.1 |

Table 3.

Default TEB target weights and FLC-TEB calculated weights for the entry corridor section of Simulation Map.

Table 3.

Default TEB target weights and FLC-TEB calculated weights for the entry corridor section of Simulation Map.

| Weights |

TEB |

Smooth-TEB |

FLC-TEB |

| Obstacle |

100.0 |

100.0 |

463.9 |

| Smoothness |

|

1.0 |

31.6 |

| Velocity/Acceleration (Linear) |

2.0 |

2.0 |

31.6 |

| Velocity/Acceleration (Angular) |

1.0 |

1.0 |

10.0 |

| Jerk (Linear) |

|

2.0 |

31.6 |

| Jerk(Angular) |

|

1.0 |

10.0 |

| Shortest path |

1.0 |

1.0 |

0.8 |

Table 4.

Comparison of Planning Results between TEB, Smooth-TEB, and FLC-TEB.

Table 4.

Comparison of Planning Results between TEB, Smooth-TEB, and FLC-TEB.

| Trajectory performance indicators |

TEB |

Smooth-TEB |

FLC-TEB |

| Trajectory length(m) |

2.88 |

2.70 |

2.69 |

| Trajectory duration(s) |

8.25 |

9.90 |

12.30 |

| Trajectory average angle changes (rad) |

0.0880 |

0.0571 |

0.0437 |

| Trajectory average linear velocity(m/s) |

0.33 |

0.26 |

0.22 |

| Trajectory linear velocity smoothness(m2/s2) |

0.0295 |

0.0144 |

0.0128 |

| Trajectory average angular velocity(rad/s) |

0.22 |

0.18 |

0.14 |

| Trajectory angular velocity smoothness(rad2/s2) |

0.0612 |

0.0464 |

0.0272 |

Table 5.

Comparison of Actual Motion Results of TEB, Smooth-TEB, and FLC-TEB in Simulation Map.

Table 5.

Comparison of Actual Motion Results of TEB, Smooth-TEB, and FLC-TEB in Simulation Map.

| Trajectory performance indicators |

TEB |

Smooth-TEB |

FLC-TEB |

| Trajectory length(m) |

8.34 |

8.35 |

8.26 |

| Trajectory duration(s) |

22.60 |

23.50 |

24.00 |

| Trajectory average angle changes (rad) |

0.0037 |

0.0026 |

0.0023 |

| Trajectory average linear velocity(m/s) |

0.37 |

0.36 |

0.34 |

| Trajectory linear velocity smoothness(m2/s2) |

0.0053 |

0.0073 |

0.0110 |

| Trajectory average angular velocity(rad/s) |

0.17 |

0.13 |

0.11 |

| Trajectory angular velocity smoothness(rad2/s2) |

0.0381 |

0.0236 |

0.0173 |

Table 6.

Car-like robot chassis parameters.

Table 6.

Car-like robot chassis parameters.

| Components |

Product Model |

| Industrial Control Computer (IPC) |

NVIDIA Jetson Agx Xavier |

| Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) |

WHEELTEC N100 |

| Laser Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) |

LSLIDAR C32 |

| Camera |

Orbbec Gemini 2 |

Table 7.

Car-like robot chassis parameters.

Table 7.

Car-like robot chassis parameters.

| Parameters |

Values |

| Wheelbase(m) |

0.56 |

| Maximum steering angle (rad) |

0.60 |

| Minimum turning radius (m) |

1.20 |

| Maximum linear velocity(m/s) |

1.00 |

| Maximum linear acceleration(m/s2) |

0.50 |

| Envelope size (m3) |

1.045×0.66×0.425 |

Table 8.

Comparison of Motion Results of TEB, Smooth-TEB, and FLC-TEB in Real Environments.

Table 8.

Comparison of Motion Results of TEB, Smooth-TEB, and FLC-TEB in Real Environments.

| Trajectory performance indicators |

TEB |

Smooth-TEB |

FLC-TEB |

| Trajectory length(m) |

11.19 |

10.63 |

9.41 |

| Trajectory duration(s) |

28.3 |

35.5 |

32.8 |

| Trajectory average angle changes (rad) |

0.0504 |

0.0311 |

0.0358 |

| Trajectory average linear velocity(m/s) |

0.50 |

0.38 |

0.38 |

| Trajectory linear velocity smoothness(m2/s2) |

0.1757 |

0.0987 |

0.0541 |

| Trajectory average angular velocity(rad/s) |

0.19 |

0.15 |

0.15 |

| Trajectory angular velocity smoothness(rad2/s2) |

0.0607 |

0.0352 |

0.0382 |