Submitted:

11 July 2024

Posted:

12 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Collision Avoidance System General Architecture

2.1. Collision Problem Description

2.2. Collision System Framework

3. Path Planning for Autonomous Obstacle Avoidance Based on an Improved APF algorithm

3.1. Road Potential Field Model

3.1.1. Hazardous Potential Fields at Road Boundaries

3.1.2. Safe Distance Protection Model

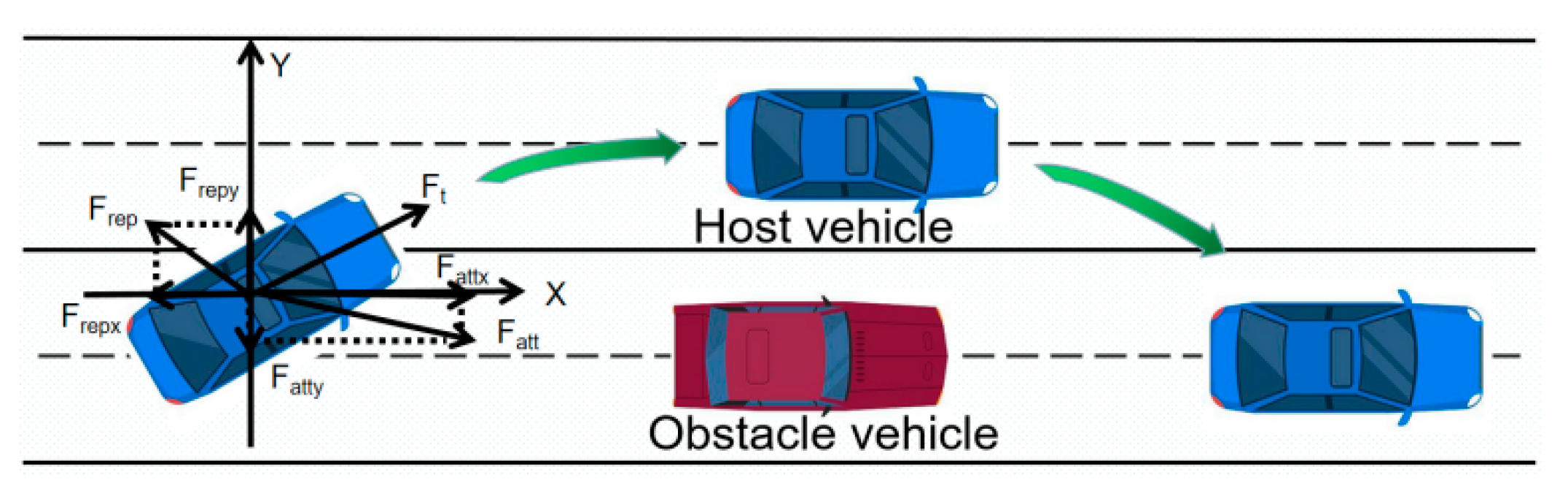

3.2. Traditional Artificial Potential Field Method

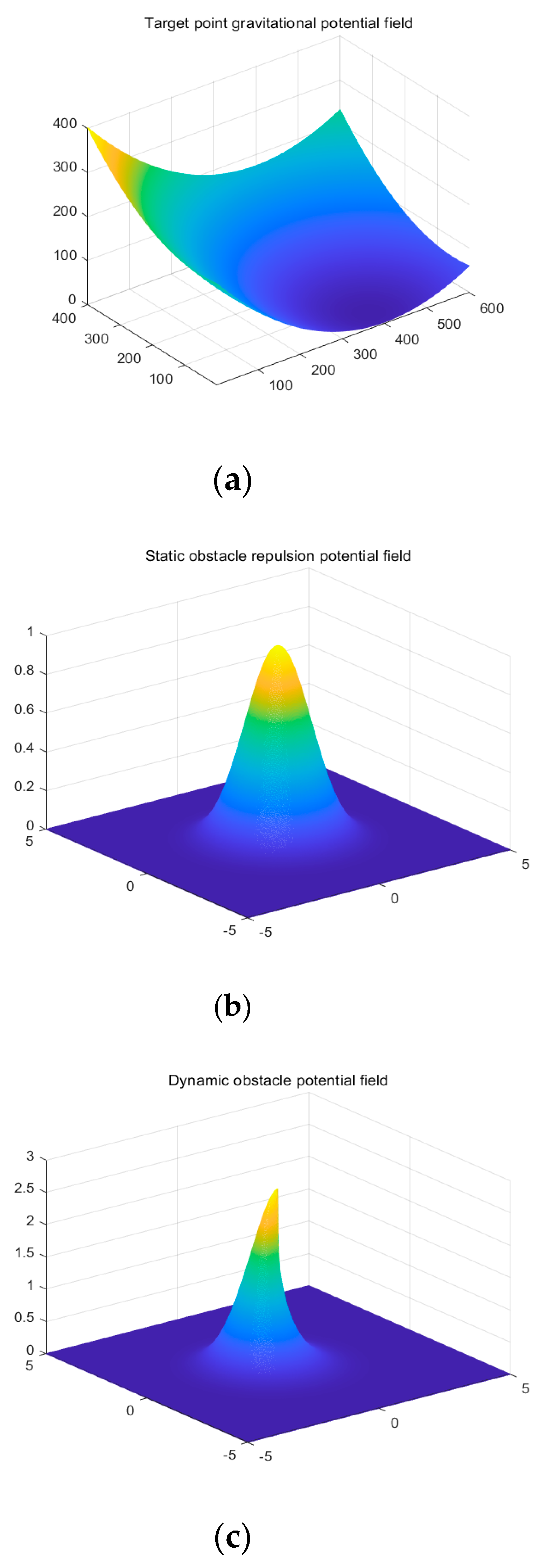

3.2.1. Target Point Gravitational Field

3.2.2. Obstacle Vehicle Repulsion Field

3.3. Optimization of the Artificial Potential Field Method

3.3.1. Repulsive Potential Field Function with Increased Distance Adjustment Factor

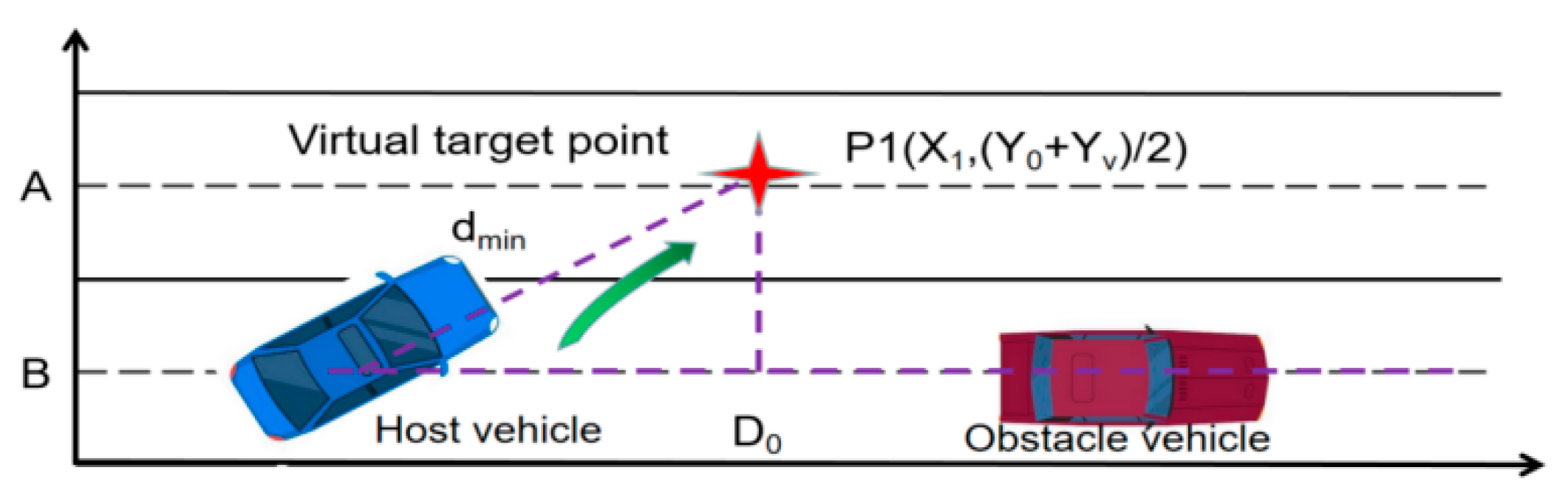

3.3.2. Subtarget Virtual Point Intervention

3.3.3. Subtarget Virtual Potential Field Attraction Function

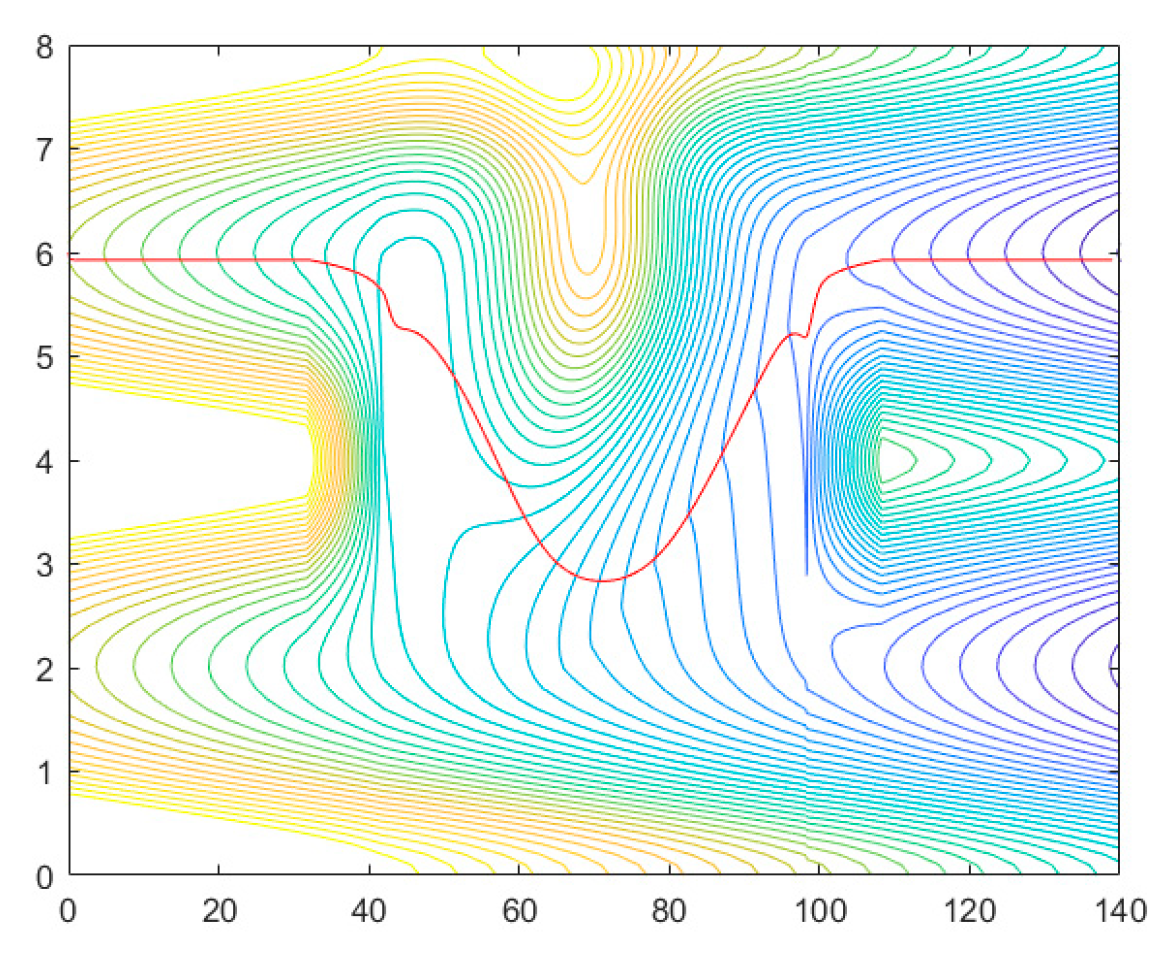

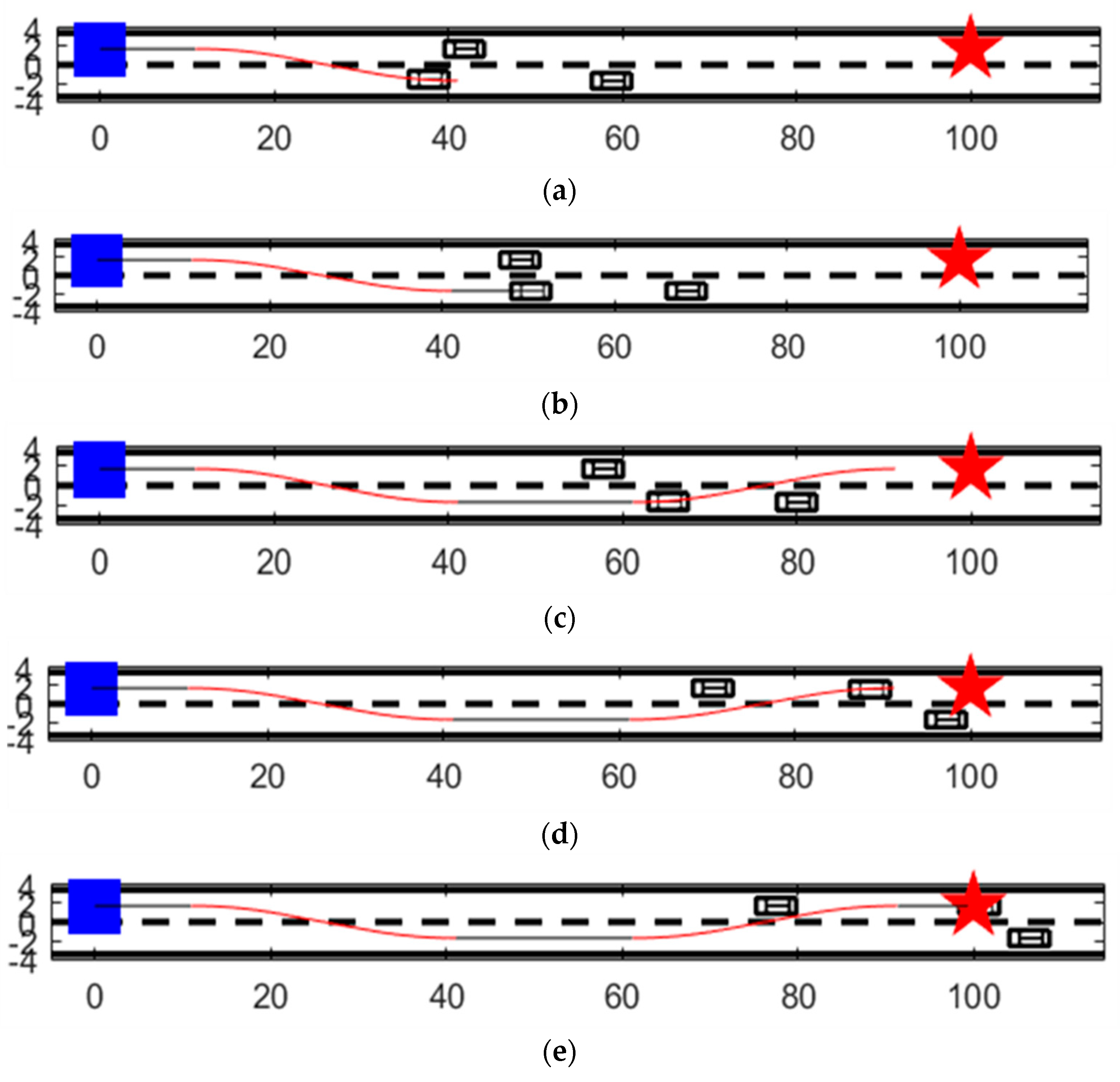

4. Autonomous Obstacle Avoidance Path Planning for Autonomous Driving Vehicles Based on Optimized APF Algorithm

4.1. Experimental Parameter Presetting

4.2. Simulation Experiment Analysis

4.3. Conclusion of the Simulation Experiment

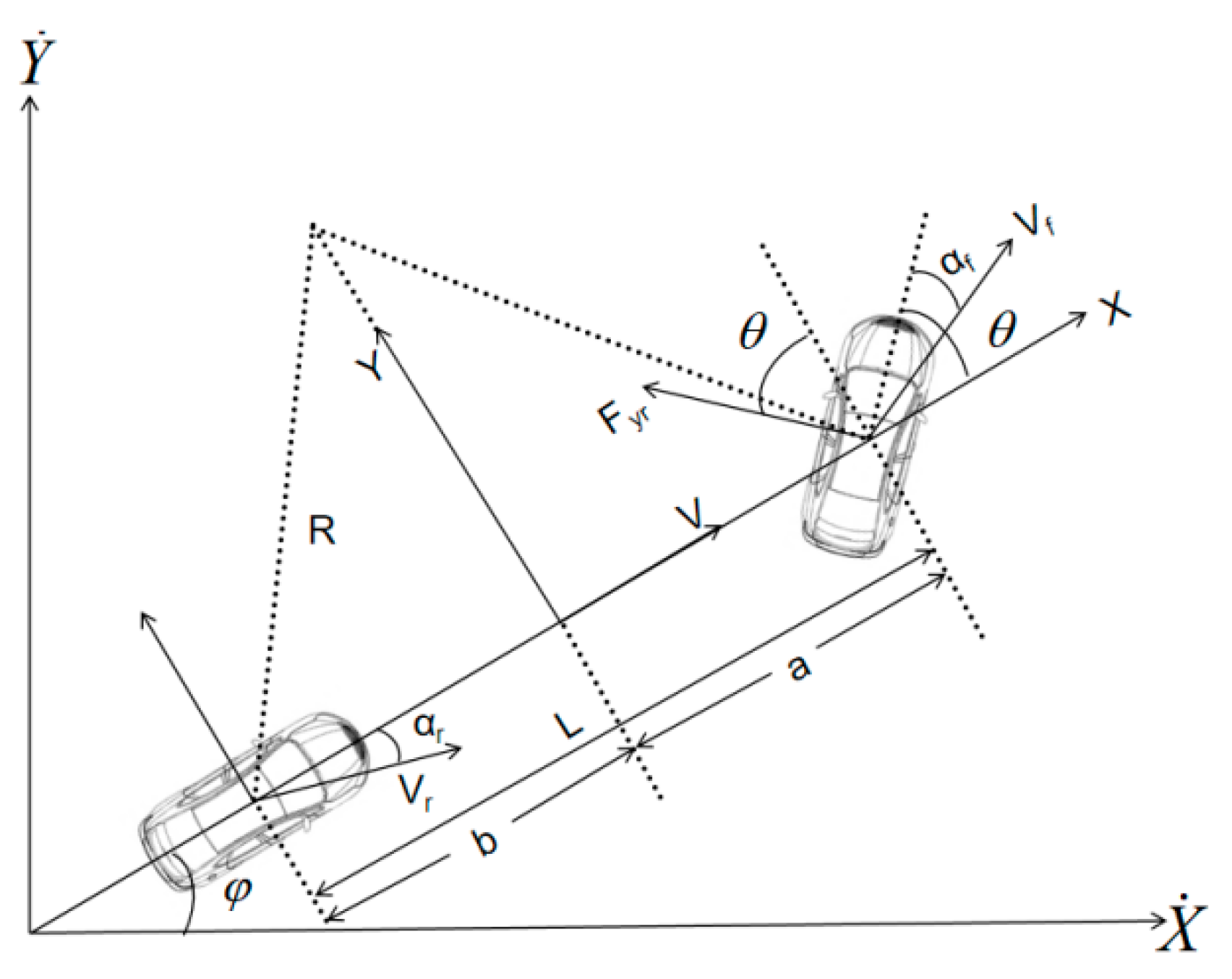

5. Vehicle Dynamics Modeling

5.1. Conditional Assumptions

- The vehicle only performs planar, two-dimensional motion parallel to the road surface due to the excellent road surface travel conditions.

- Because of the vehicle’s rigidity, the effect of the suspension system is not taken into account.

- The left and right wheels’ angles do not alter when the vehicle rotates with the front wheels;

- Not taking into account how the vehicle tires are coupled longitudinally and laterally;

- Disregards the impact of aerodynamics;

- Disregards the transfer of vehicle load;

- In order to streamline the study, the bicycle model is created while taking into account the characteristics of the reference path, as illustrated in Figure 6.

5.2. Vehicle Kinematics Modeling

5.3. Simplified Model of Vehicle Dynamics

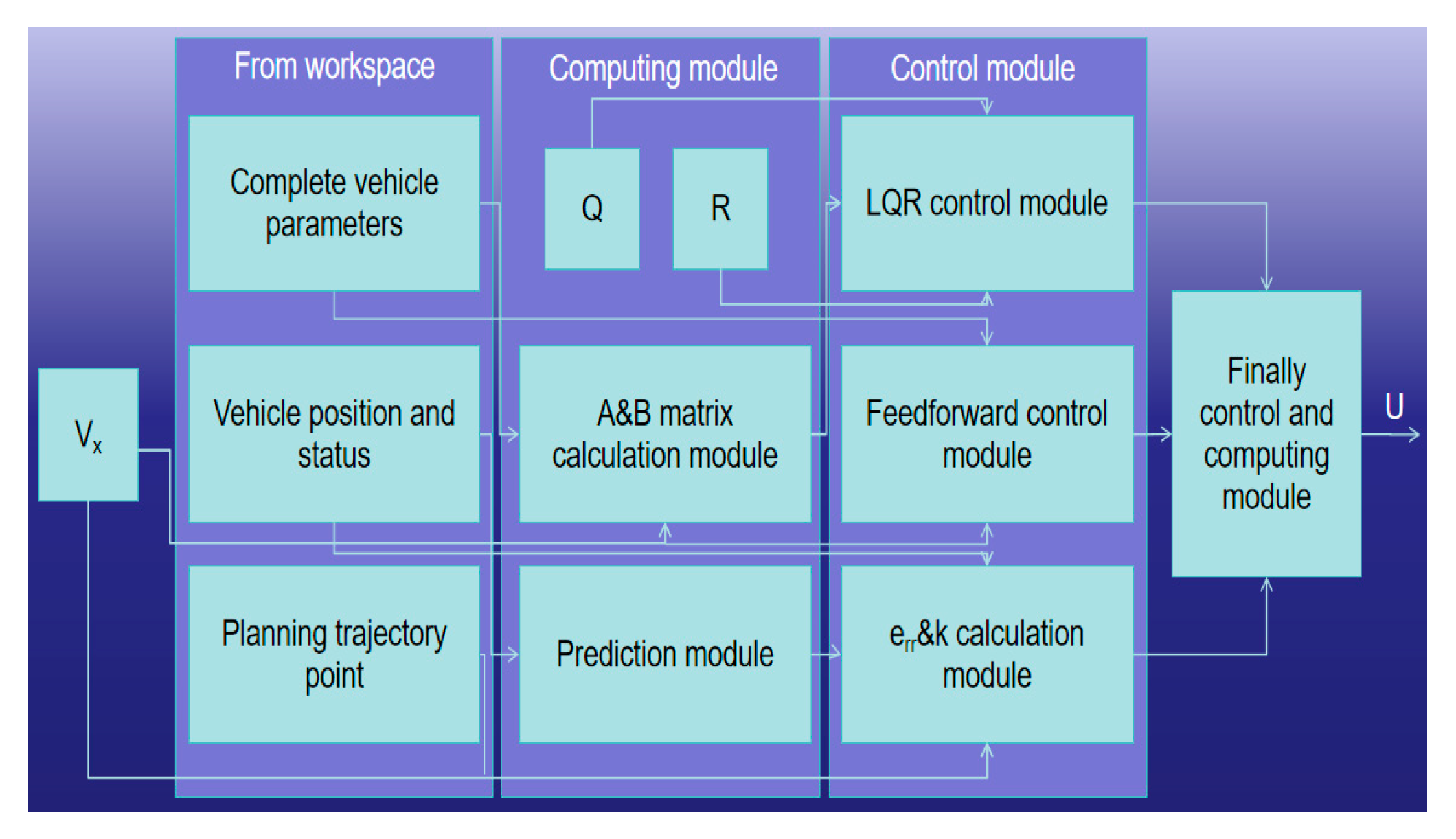

6. Path Tracking for Autonomous Vehicles Based on DLQR Control Algorithm

6.1. Path Tracking Control Architecture

6.2. Calculation of Error Parameters

6.3. Feed forward Control

6.4. Forecasting System

6.5. Optimal DLQR Control

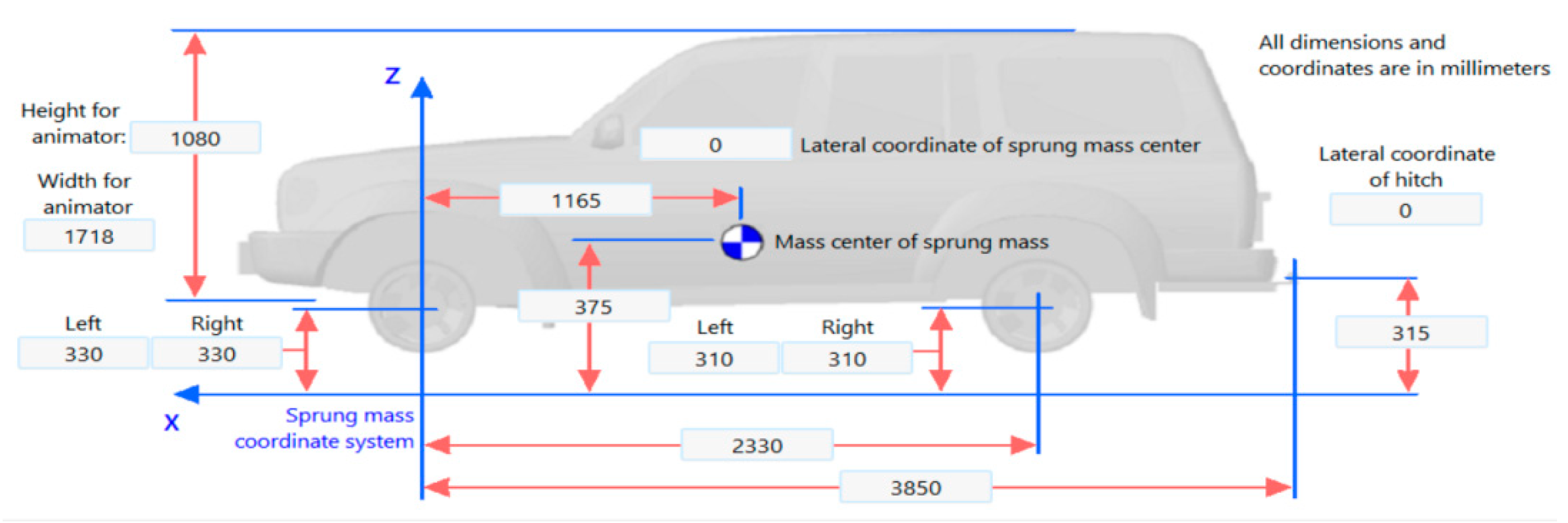

7. Joint Carsim and Simulink for Path Tracking Experiment Simulation

7.1. Joint Simulation Platform

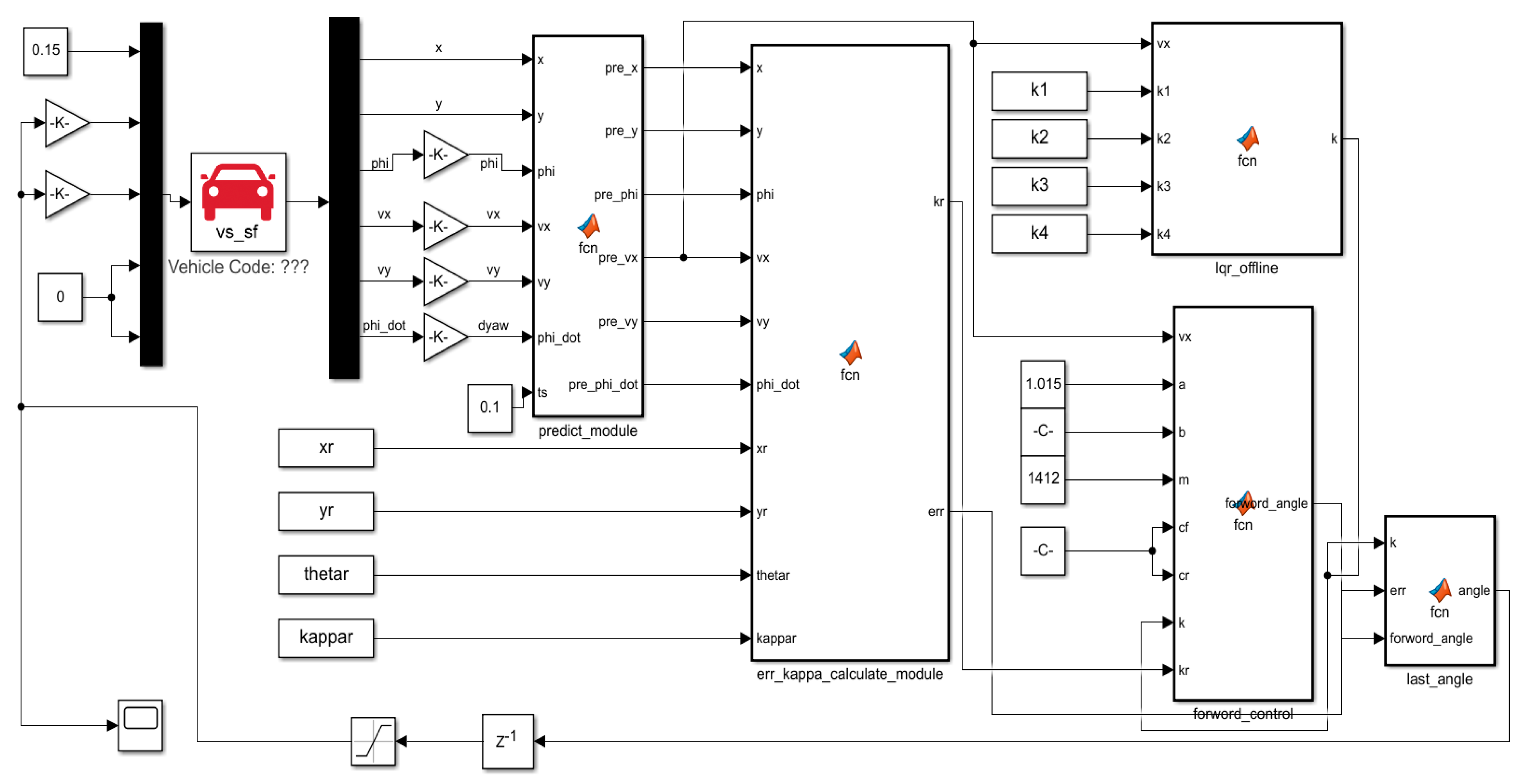

7.2. Tracking Control Algorithm Architecture

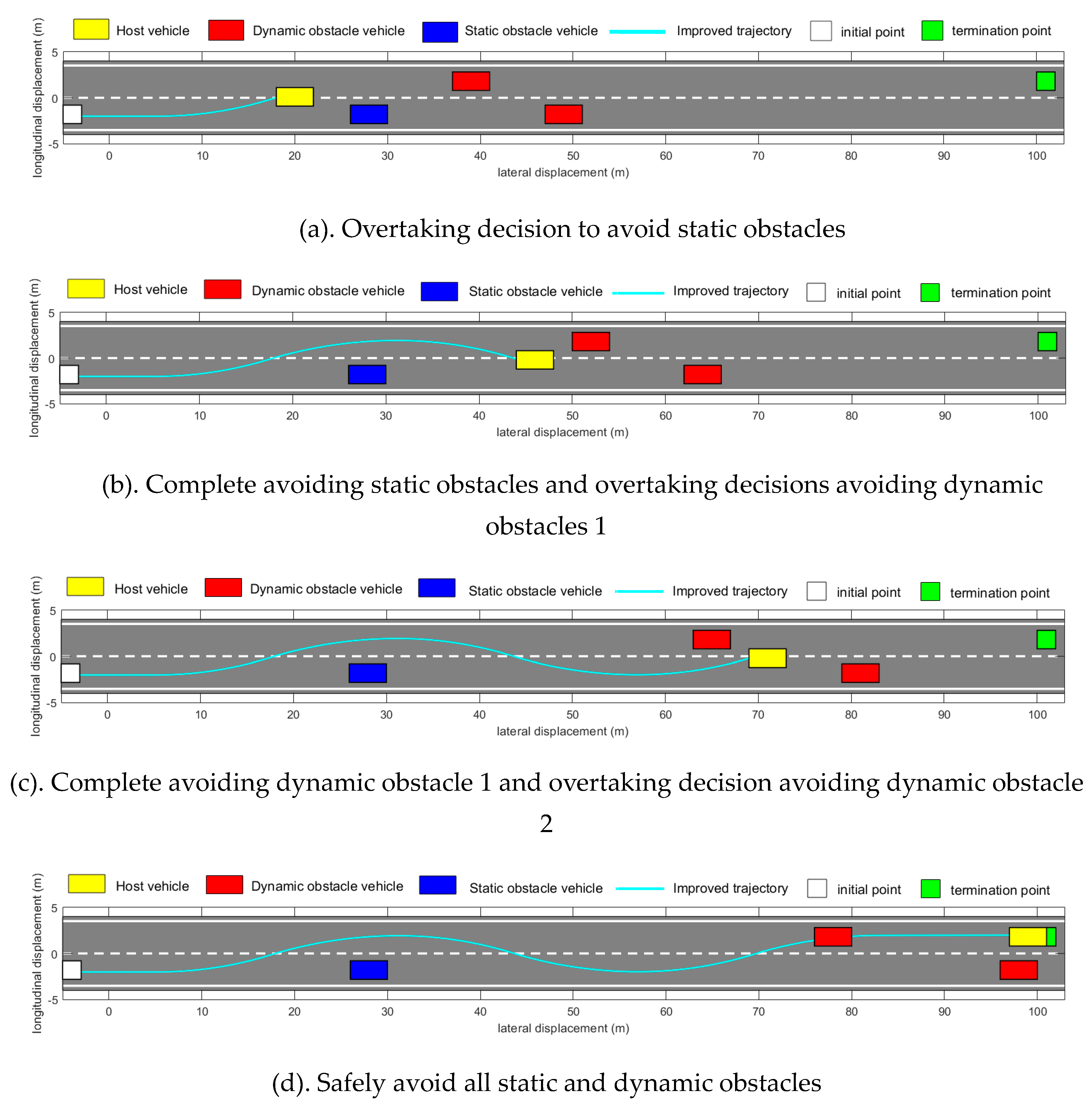

7.3. Simulation Analysis of Obstacle Avoidance in Different Obstacle Scenarios

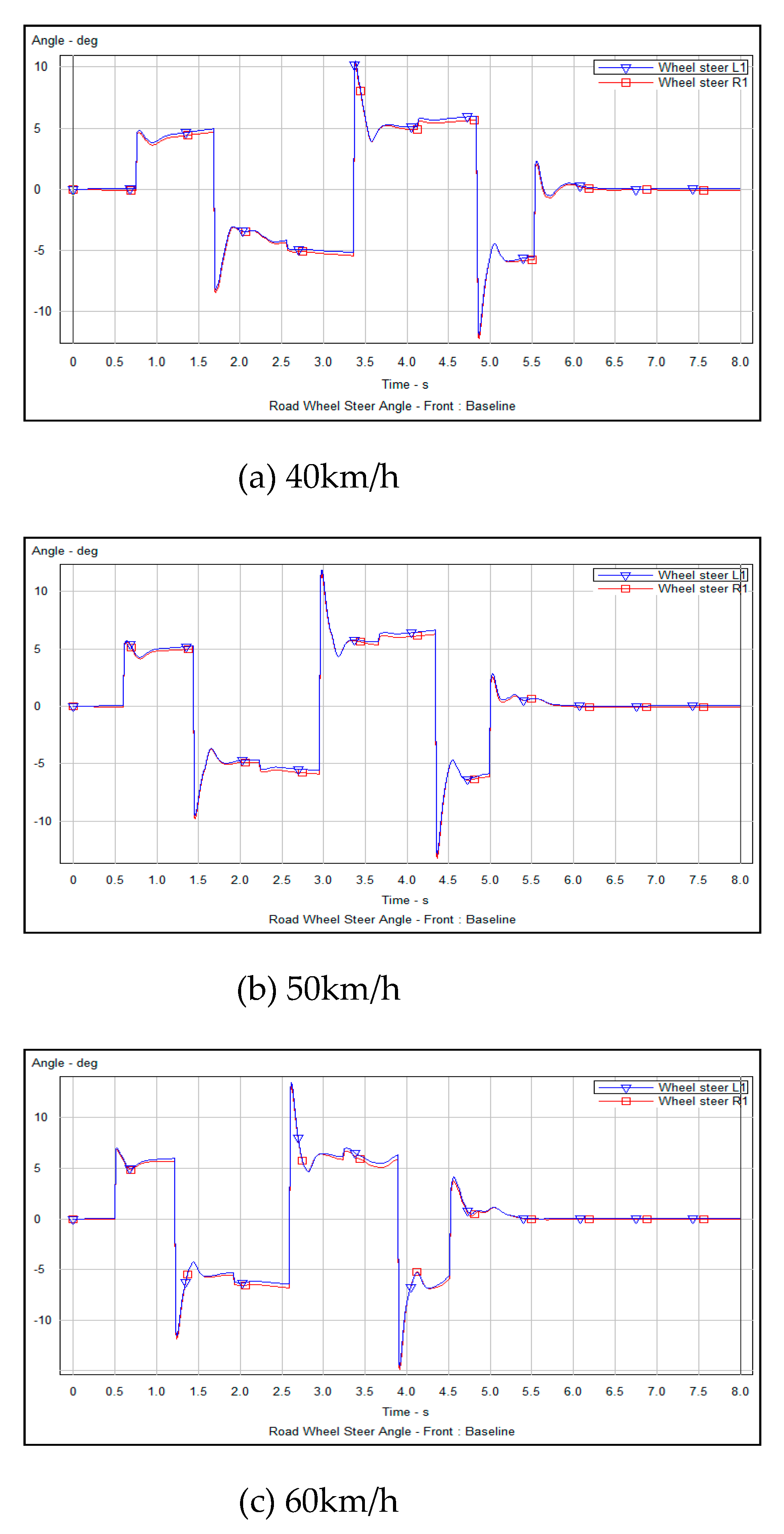

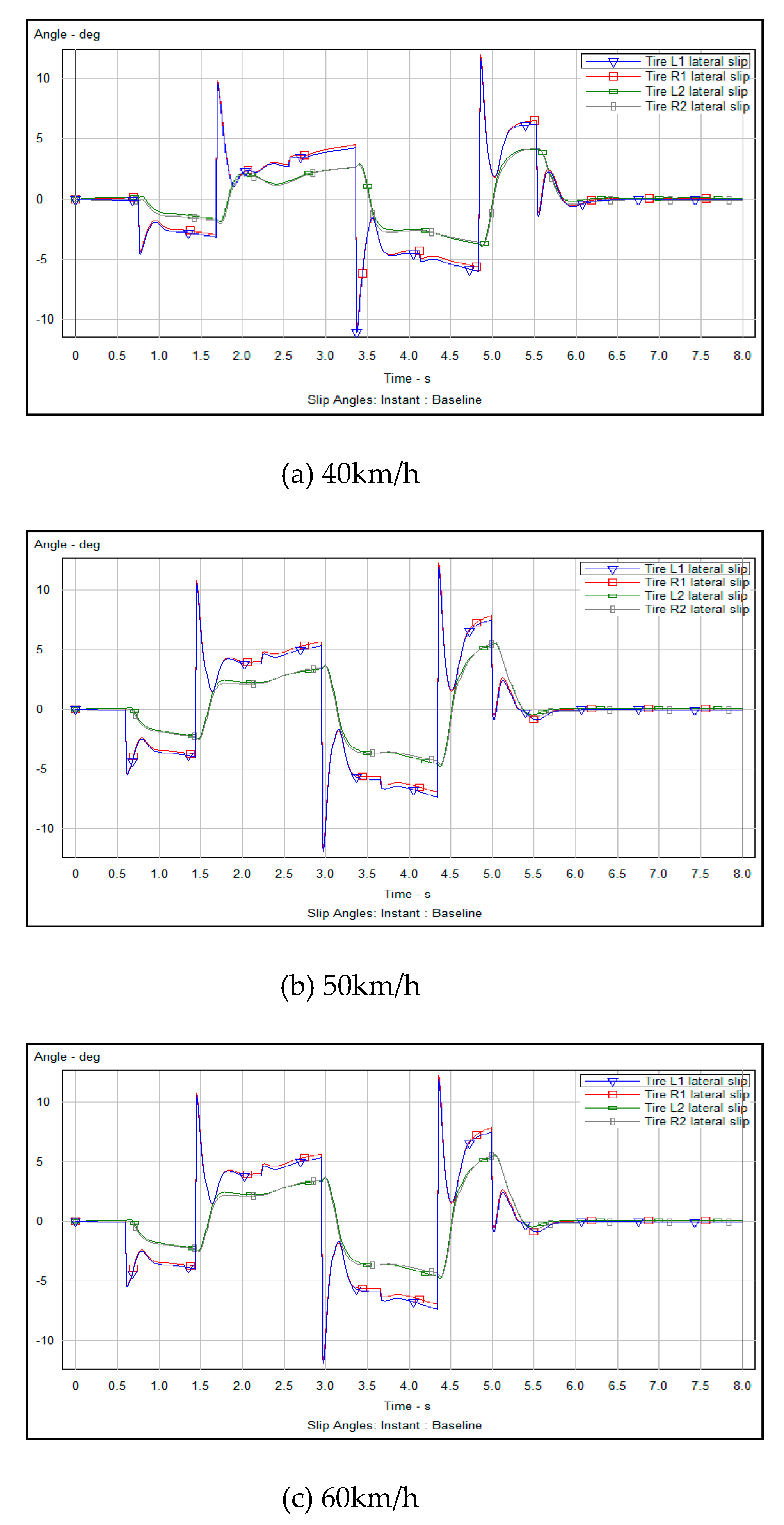

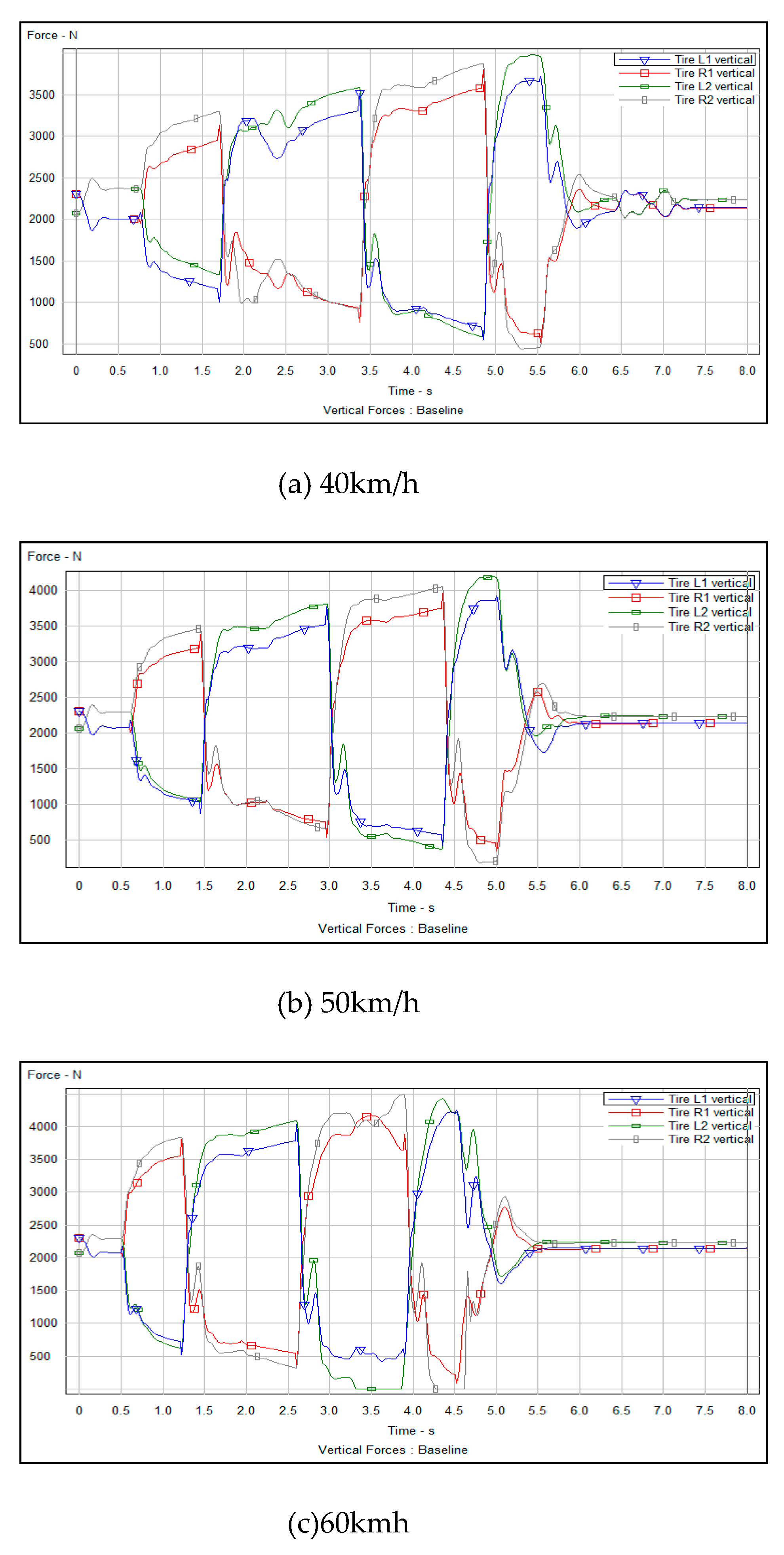

7.4. Simulation Analysis of Tracking Motion under Different Speed Parameters

8. Conclusion

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, X.; Hu, W.; Dong, H. Review of Key Technologies for Autonomous Vehicle Test Scenario Construction. Automot. Eng. 2021, 43, 610–619. [Google Scholar]

- Man,J.Research on Intelligent Vehicle Path Tracking Control,.Ph.D.Thesis,Zhejiang University Hangzhou. China, 2021.

- Le Vine,S.Zolfaghari,A.,Polak, J.Autonomous cars: the tension between occupant experience and intersection capacity. Transp. Res.C,Emerg. Technol,2015, 52,pp. 1-14.

- Chen L,Liu C,Shi H,etal.New robot planning algorithm based on improved artificial potential field.In: 2013 Third international conference on instrumentation,measurement computer,communication and control,Shenyang,China,21-23 September 2013, pp. 228-232.15.

- Tang, Z.; Ji, J.; Wu, M. Vehicles Path Planning and Tracking Based on an Improved Artificial Potential Field Method. j. Southwest Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.). 2018, 6, 180–188. [Google Scholar]

- An, L.; Chen, T.; Cheng, A. A Simulation on the Path Planning of Intelligent V ehicles Based on Artificial Potential Field Algorithm. qiche gongcheng/ Automot. Eng. 2017, 39, 1451–1456. [Google Scholar]

- Xiu, C.; Chen, H. A Research on Local Path Planning for Autonomous V ehicles Based on Improved APF Method Automotive engineering. automot. eng. 2013, 35 Automot. Eng. 2013, 35 , 808-811.

- Lee, J.; Nam, Y.; Hong, S. Random force based algorithm for local minima escape of potential field method. In Proceedings of the 2010 11th International Conference on Control Automation Robotics & Vision, Singapore, 7-10 December 2010; pp. 827–832. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.; Pan, L.; Cao, H. Local path planning for vehicle obstacle avoidance based on improved intelligent water drops algorithm. automot. eng. 2016, . 38, 185–191. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Liu, M.; Ci, Y . Wang, X.; Liu, M.; Ci, Y . Effectiveness of driver's bounded rationality and speed guidance on fuel-saving and emissions-reducing at a signalized intersection. j Clean. Prod. 2021,325, 129343.

- Liu, J.; Yang, Y. Liu, H.; Di, P. ; Gao, M. Robot global path planning based on ant colony optimization with artificial potential field.Nongye Jixie Xuebao/T rans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach.. 2015, 46.

- Liu, Y . ; Zhang, W.G.; Li, G.W. Study on path planning based on improved PRM method. Jisuanji Yingyong Yanjiu 2012, 29.

- Zheng Y, Shao X, Chen Z, et al. Improvements on the virtual obstacle method. Int J Adv Robot Syst 2020; 17: 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Matoui F, Boussaid B, and Abdelkrim MN. Distributed path planning of a multi-robot system based on the neighborhood artificial potential field approach. simulation 2019; 95(7):637-657. [CrossRef]

- Yue M, Ning Y, Guo L, et al. A WIP vehicle control method based on improved artificial potential field subject to multi- obstacle environment. inf Technol Control 2020; 49(3):320-334. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.X.; Wu, G.Q.; Guo, X.X. Path tracking using linear time-varying model predictive control for autonomous vehicle. j. Tongji Univ. Nat. Sci. 2016, 44, 1595–1603. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.X.; Wu, G.Q.; Guo, X.X. Path tracking using linear time-varying model predictive control for autonomous vehicle. j. Tongji Univ. Nat. Sci. 2016, 44, 1595–1603. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Hu, J.; Gao, L.; Liu, X.; Bai, X. Agricultural machine path tracking method based on fuzzy adaptive pure pursuit model. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2013, 44, 205–210. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, S. The Intelligent V ehicle Motion Research Based on LinearActive Disturbance Rejection Control. ph.D. Thesis, Xiamen University, Xiamen,. China, 2019.

- Lee, S.H.; Lee, Y .O.; Kim, B.A.; Chung, C.C. Proximate model predictive control strategy for autonomous vehicle lateral control.In Proceedings of the American Control Conference (ACC), Montreal, QC, Canada, 27-29 June 2012; pp. 3605-3610.

- Zhou, L.H.; Shi, P .L.; Jiang, J.X.; Zhang, L.; Liang, M.L.; Hou, J.W. Simulation research on vehicle stability control based on collision avoiding trajectory tracking. J. Shandong Univ. Technol.(Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 35, 75-81.

- Wu, L.; Ci, Y . ; Sun, Y . ; Qi, W. Research on Joint Control of On-ramp Metering and Mainline Speed Guidance in the Urban Expressway based on MPC and Connected V ehicles. j. Adv. Transp. 2020, 2020, 7518087.

- Morales, S.; Magallanes, J.; Delgado, C.; Canahuire, R. LQR trajectory tracking control of an omnidirectional wheeled mobile robot. in Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 2nd Colombian Conference on Robotics and Automation (CCRA), Barranquilla, Colombia,1-3 November 2018;pp. 1 -5.

- Chen, J.; Li, L.; Song, J. A study on vehicle stability control based on LTV-MPC. Automot. Eng. 2016, 38, 308–316. [Google Scholar]

- Tingbin C,Peng Z,Shuang G, et al. Research on the Dynamic Target Distribution Path Planning in Logistics System Based on Improved Artificial Potential Field Method-Fish Swarm Algorithm[C]//Northeastern University, Chinese Society of Automation, Information physical System Control and decision Committee. Proceedings of the 30th Conference on Control and Decision-making in China2018:4.

- Xu, R.; Guo, Y .; Han, X.; Xia, X.; Xiang, H.; Ma, J. OpenCDA: An open cooperative driving automation framework integrated with co-simulation. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Intelligent Transportation Systems Conference (ITSC), Indianapolis,IN, USA, 19–22September 2021.

| Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Sprung mass | 1020 | kg |

| Width for animator | 1718 | mm |

| Yaw inertia | 1020 | Kg*m2 |

| Axle base | 2330 | mm |

| Height of wheel center | 310 | mm |

| Height of the center of mass | 375 | mm |

| Speed (km/h) |

Maximum fluctuation range of steering Angle (deg) | Maximum fluctuation range of side deflection Angle(deg) | Maximum tire steering vertical support (N) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | 4.0°- 6.0° | 0°- 6.0° | 4000 |

| 50 | 4.1°- 6.2° | 0°- 7.0° | 4250 |

| 60 | 4.3°- 6.3° | 0°- 8.0° | 4500 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).