Submitted:

04 December 2024

Posted:

05 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

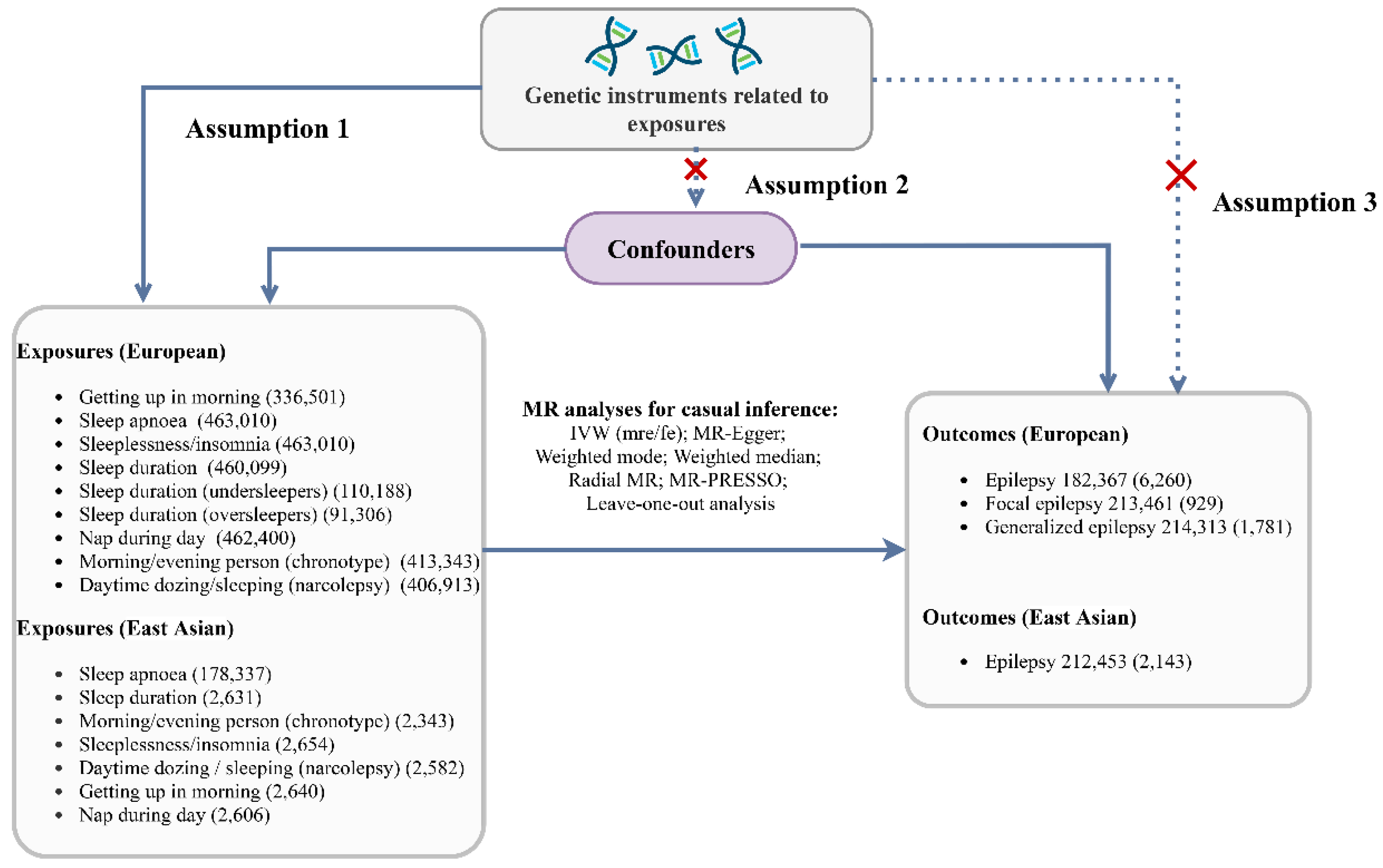

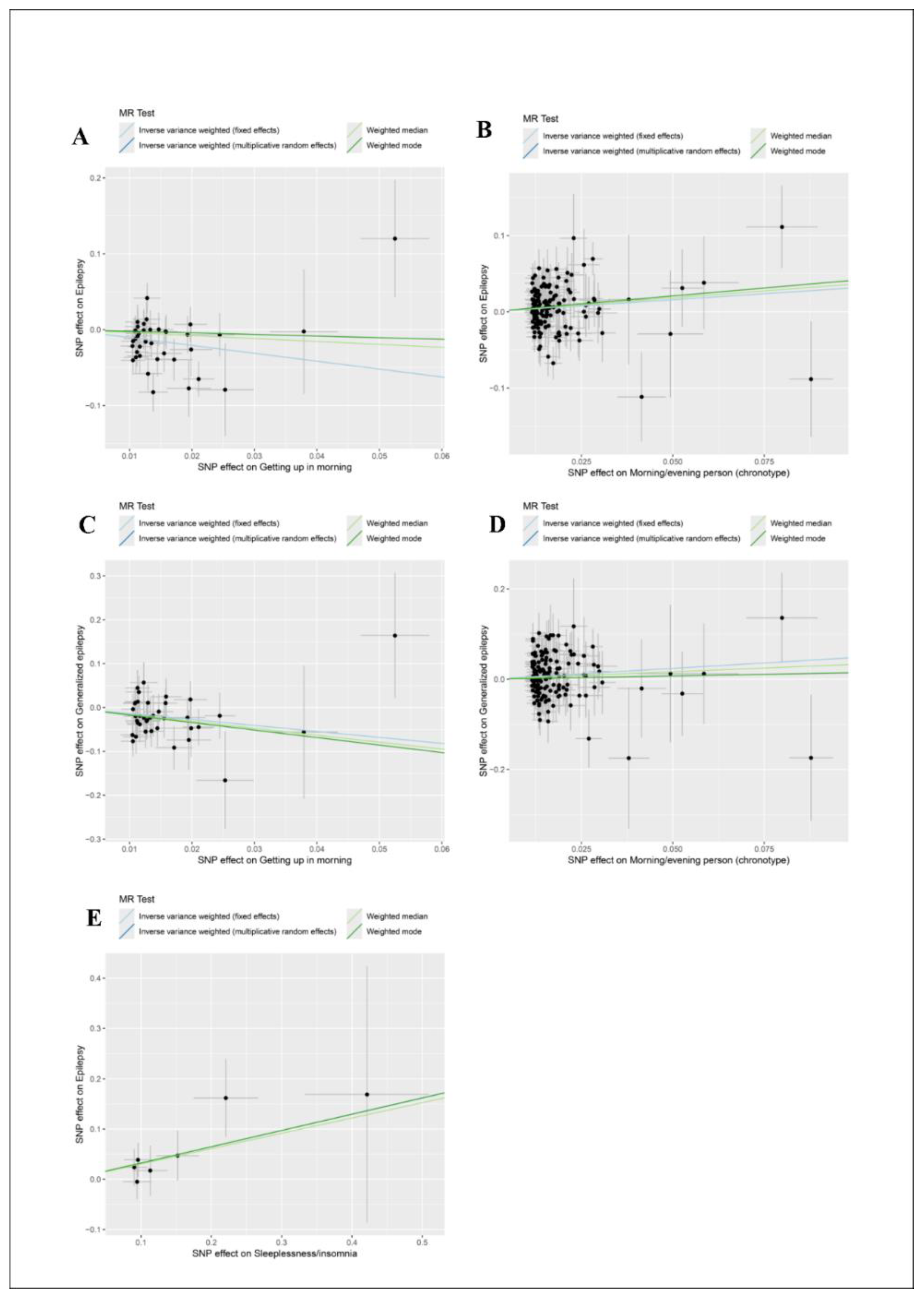

Background: Sleep and epilepsy have been reported to have a possible interaction. This study intended to assess the causal relationship between sleep traits and epilepsy risk through a two-sample Mendelian randomization (MR) study. Methods: Exposure- [sleep traits: getting up in morning, sleeplessness/insomnia, sleep duration, nap during day, morning/evening person (chronotype), daytime dozing/sleeping (narcolepsy).] and outcome- [Europeans: epilepsy, focal epilepsy, generalized epilepsy; East Asians: epilepsy] related single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from publicly available genome-wide association studies (GWAS) databases were used as instrumental variables for analysis. The main analyses used inverse variance weighted (IVW) to derive causality estimates, which were expressed as odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). Sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the reliability of the results. Results: For Europeans, genetically predicted getting up in morning decreased the risk of epilepsy (OR=0.354, 95%CI: 0.212-0.589) and generalized epilepsy (OR=0.256, 95%CI: 0.101-0.651), whereas genetically predicted evening person (chronotype) increased the risk of epilepsy (OR=1.371, 95%CI: 1.082-1.739) and generalized epilepsy (OR=1.618, 95%CI: 1.061-2.467). No significant associations were found between genetically predicted sleeplessness/insomnia, sleep duration, nap during day, and daytime dozing/sleeping (narcolepsy) and the risk of epilepsy, focal epilepsy, and generalized epilepsy in Europeans. For East Asians, only genetically predicted sleeplessness/insomnia was found to increase the risk of epilepsy (OR=1.381, 95%CI: 1.039-1.837). Conclusion: There was a causal relationship between getting up in morning and evening person (chronotype) and epilepsy risk in Europeans, and between sleeplessness/insomnia and epilepsy in East Asians.

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Data Source and Study Design

Genetic Instrumental Variable

Selection of Instrumental Variables

Statistical Analysis

Results

Characteristics of Instrumental Variables

Causal Relationship Between Sleep Traits and Epilepsy Risk

Discussion

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Authors’ contributions

Consent for publication

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Availability of data and materials

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

References

- Thijs RD, Surges R, O'Brien TJ, Sander JW: Epilepsy in adults. Lancet (London, England) 2019, 393(10172):689-701. [CrossRef]

- Perucca P, Gilliam FG: Adverse effects of antiepileptic drugs. The Lancet Neurology 2012, 11(9):792-802. [CrossRef]

- Fishbein AB, Knutson KL, Zee PC: Circadian disruption and human health. The Journal of clinical investigation 2021, 131(19). [CrossRef]

- Abbott SM, Malkani RG, Zee PC: Circadian disruption and human health: A bidirectional relationship. The European journal of neuroscience 2020, 51(1):567-583. [CrossRef]

- Khan S, Nobili L, Khatami R, Loddenkemper T, Cajochen C, Dijk DJ, Eriksson SH: Circadian rhythm and epilepsy. The Lancet Neurology 2018, 17(12):1098-1108. [CrossRef]

- de Bergeyck R, Geoffroy PA: Insomnia in neurological disorders: Prevalence, mechanisms, impact and treatment approaches. Revue neurologique 2023, 179(7):767-781. [CrossRef]

- Bergmann M, Tschiderer L, Stefani A, Heidbreder A, Willeit P, Högl B: Sleep quality and daytime sleepiness in epilepsy: Systematic review and meta-analysis of 25 studies including 8,196 individuals. Sleep medicine reviews 2021, 57:101466. [CrossRef]

- Schurhoff N, Toborek M: Circadian rhythms in the blood-brain barrier: impact on neurological disorders and stress responses. Molecular brain 2023, 16(1):5. [CrossRef]

- Lipton JO, Yuan ED, Boyle LM, Ebrahimi-Fakhari D, Kwiatkowski E, Nathan A, Güttler T, Davis F, Asara JM, Sahin M: The Circadian Protein BMAL1 Regulates Translation in Response to S6K1-Mediated Phosphorylation. Cell 2015, 161(5):1138-1151. [CrossRef]

- Zhao W, Xie C, Zhang X, Liu J, Liu J, Xia Z: Advances in the mTOR signaling pathway and its inhibitor rapamycin in epilepsy. Brain and behavior 2023, 13(6):e2995. [CrossRef]

- Choi SJ, Joo EY, Hong SB: Sleep-wake pattern, chronotype and seizures in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy research 2016, 120:19-24. [CrossRef]

- Najar LL, Santos RP, Foldvary-Schaefer N, da Mota Gomes M: Chronotype variability in epilepsy and clinical significance: scoping review. Epilepsy & behavior : E&B 2024, 157:109872. [CrossRef]

- Brigo F, Igwe SC, Del Felice A: Melatonin as add-on treatment for epilepsy. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2016, 2016(8):Cd006967. [CrossRef]

- Davies NM, Holmes MV, Davey Smith G: Reading Mendelian randomisation studies: a guide, glossary, and checklist for clinicians. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2018, 362:k601. [CrossRef]

- Ben Elsworth, Matthew Lyon, Tessa Alexander, Yi Liu, Peter Matthews, Jon Hallett, Phil Bates, Tom Palmer, Valeriia Haberland, George Davey Smith et al: The MRC IEU OpenGWAS data infrastructure. bioRxiv 2020, 08:244293v244291. [CrossRef]

- Jones SE, Tyrrell J, Wood AR, Beaumont RN, Ruth KS, Tuke MA, Yaghootkar H, Hu Y, Teder-Laving M, Hayward C et al: Genome-Wide Association Analyses in 128,266 Individuals Identifies New Morningness and Sleep Duration Loci. PLoS genetics 2016, 12(8):e1006125. [CrossRef]

- Sun BB, Maranville JC, Peters JE, Stacey D, Staley JR, Blackshaw J, Burgess S, Jiang T, Paige E, Surendran P et al: Genomic atlas of the human plasma proteome. Nature 2018, 558(7708):73-79. [CrossRef]

- Sakaue S, Kanai M, Tanigawa Y, Karjalainen J, Kurki M, Koshiba S, Narita A, Konuma T, Yamamoto K, Akiyama M et al: A cross-population atlas of genetic associations for 220 human phenotypes. Nature genetics 2021, 53(10):1415-1424. [CrossRef]

- Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Haycock PC, Burgess S: Consistent Estimation in Mendelian Randomization with Some Invalid Instruments Using a Weighted Median Estimator. Genetic epidemiology 2016, 40(4):304-314. [CrossRef]

- Burgess S, Thompson SG: Bias in causal estimates from Mendelian randomization studies with weak instruments. Statistics in medicine 2011, 30(11):1312-1323. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Gao L, Lang W, Li H, Cui P, Zhang N, Jiang W: Serum Calcium Levels and Parkinson's Disease: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Frontiers in genetics 2020, 11:824. [CrossRef]

- Staley K: Molecular mechanisms of epilepsy. Nature neuroscience 2015, 18(3):367-372. [CrossRef]

- Patel M: Targeting Oxidative Stress in Central Nervous System Disorders. Trends in pharmacological sciences 2016, 37(9):768-778. [CrossRef]

- Ishii T, Takanashi Y, Sugita K, Miyazawa M, Yanagihara R, Yasuda K, Onouchi H, Kawabe N, Nakata M, Yamamoto Y et al: Endogenous reactive oxygen species cause astrocyte defects and neuronal dysfunctions in the hippocampus: a new model for aging brain. Aging cell 2017, 16(1):39-51. [CrossRef]

- Terrone G, Balosso S, Pauletti A, Ravizza T, Vezzani A: Inflammation and reactive oxygen species as disease modifiers in epilepsy. Neuropharmacology 2020, 167:107742. [CrossRef]

- Fei CJ, Li ZY, Ning J, Yang L, Wu BS, Kang JJ, Liu WS, He XY, You J, Chen SD et al: Exome sequencing identifies genes associated with sleep-related traits. Nature human behaviour 2024, 8(3):576-589. [CrossRef]

- Hu J, Lu J, Lu Q, Weng W, Guan Z, Wang Z: Mendelian randomization and colocalization analyses reveal an association between short sleep duration or morning chronotype and altered leukocyte telomere length. Communications biology 2023, 6(1):1014. [CrossRef]

- Wynchank D, Bijlenga D, Penninx BW, Lamers F, Beekman AT, Kooij JJS, Verhoeven JE: Delayed sleep-onset and biological age: late sleep-onset is associated with shorter telomere length. Sleep 2019, 42(10). [CrossRef]

- Adan A, Archer SN, Hidalgo MP, Di Milia L, Natale V, Randler C: Circadian typology: a comprehensive review. Chronobiology international 2012, 29(9):1153-1175. [CrossRef]

- van der Merwe C, Münch M, Kruger R: Chronotype Differences in Body Composition, Dietary Intake and Eating Behavior Outcomes: A Scoping Systematic Review. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md) 2022, 13(6):2357-2405. [CrossRef]

- Wassenaar M, Kasteleijn-Nolst Trenité DG, de Haan GJ, Carpay JA, Leijten FS: Seizure precipitants in a community-based epilepsy cohort. Journal of neurology 2014, 261(4):717-724. [CrossRef]

- Riemann D, Spiegelhalder K, Feige B, Voderholzer U, Berger M, Perlis M, Nissen C: The hyperarousal model of insomnia: a review of the concept and its evidence. Sleep medicine reviews 2010, 14(1):19-31. [CrossRef]

- Levenson JC, Kay DB, Buysse DJ: The pathophysiology of insomnia. Chest 2015, 147(4):1179-1192. [CrossRef]

- Meyer N, Harvey AG, Lockley SW, Dijk DJ: Circadian rhythms and disorders of the timing of sleep. Lancet (London, England) 2022, 400(10357):1061-1078. [CrossRef]

- Gerstner JR, Smith GG, Lenz O, Perron IJ, Buono RJ, Ferraro TN: BMAL1 controls the diurnal rhythm and set point for electrical seizure threshold in mice. Frontiers in systems neuroscience 2014, 8:121. [CrossRef]

- Li P, Fu X, Smith NA, Ziobro J, Curiel J, Tenga MJ, Martin B, Freedman S, Cea-Del Rio CA, Oboti L et al: Loss of CLOCK Results in Dysfunction of Brain Circuits Underlying Focal Epilepsy. Neuron 2017, 96(2):387-401.e386. [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan C, Kathale ND, Liu D, Lee C, Freeman DA, Hogenesch JB, Cao R, Liu AC: mTOR signaling regulates central and peripheral circadian clock function. PLoS genetics 2018, 14(5):e1007369. [CrossRef]

- Saxton RA, Sabatini DM: mTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease. Cell 2017, 168(6):960-976. [CrossRef]

| Outcome and exposure | Selected SNP (P<5E-08) (n) | Omitted LD SNP (n) | Drop palindromic SNP (n) |

F-value | R2(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epilepsy | |||||

| Getting up in morning | 5953 | 40 | 38 | 40 | 0.47 |

| Sleeplessness/insomnia | 2654 | 42 | 39 | 33 | 0.41 |

| Sleep duration | 5751 | 71 | 69 | 32 | 0.67 |

| Sleep duration (undersleepers) | 1 | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| Sleep duration (oversleepers) | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| Sleep apnoea | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| Nap during day | 8636 | 94 | 86 | 34 | 0.94 |

| Morning/evening person (chronotype) | 13669 | 161 | 150 | 38 | 1.78 |

| Daytime dozing/sleeping (narcolepsy) | 4187 | 31 | 31 | 32 | 0.30 |

| Focal epilepsy | |||||

| Getting up in morning | 5953 | 40 | 38 | 40 | 0.47 |

| Sleeplessness/insomnia | 2654 | 42 | 39 | 33 | 0.41 |

| Sleep duration | 5751 | 71 | 69 | 32 | 0.67 |

| Sleep duration (undersleepers) | 1 | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| Sleep duration (oversleepers) | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| Sleep apnoea | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| Nap during day | 8636 | 94 | 86 | 34 | 0.94 |

| Morning/evening person (chronotype) | 13669 | 161 | 150 | 38 | 1.78 |

| Daytime dozing/sleeping (narcolepsy) | 4187 | 31 | 31 | 32 | 0.30 |

| Generalized epilepsy | |||||

| Getting up in morning | 5953 | 40 | 38 | 40 | 0.47 |

| Sleeplessness/insomnia | 2654 | 42 | 39 | 33 | 0.41 |

| Sleep duration | 5751 | 71 | 69 | 32 | 0.67 |

| Sleep duration (undersleepers) | 1 | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| Sleep duration (oversleepers) | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| Sleep apnoea | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| Nap during day | 8636 | 94 | 86 | 34 | 0.94 |

| Morning/evening person (chronotype) | 13669 | 161 | 150 | 38 | 1.78 |

| Daytime dozing/sleeping (narcolepsy) | 4187 | 31 | 31 | 32 | 0.30 |

| Outcome and exposure | Horizontal pleiotropic test | Casual direction test | Heterogeneity test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egger intercept | P | MR steiger | P | MR Egger Q | P | IVW Q | P | |

| Europeans | ||||||||

| Epilepsy | ||||||||

| Getting up in morning | -0.014 | 0.350 | TRUE | 2.97E-66 | 46.615 | 0.111 | 47.779 | 0.110 |

| Sleeplessness/insomnia | -0.008 | 0.428 | TRUE | 7.89E-81 | 21.302 | 0.982 | 21.945 | 0.983 |

| Sleep duration | -0.017 | 0.123 | TRUE | 8.83E-106 | 76.710 | 0.195 | 79.506 | 0.161 |

| Nap during day | 0.012 | 0.179 | TRUE | 1.42E-157 | 90.510 | 0.294 | 92.486 | 0.271 |

| Morning/evening person (chronotype) | -0.001 | 0.823 | TRUE | 2.91E-283 | 180.538 | 0.035 | 180.599 | 0.040 |

| Daytime dozing/sleeping (narcolepsy) | 0.008 | 0.693 | TRUE | 7.90E-48 | 36.812 | 0.151 | 37.015 | 0.177 |

| Focal epilepsy | ||||||||

| Getting up in morning | 0.007 | 0.833 | TRUE | 7.34E-90 | 30.056 | 0.746 | 30.101 | 0.782 |

| Sleeplessness/insomnia | 0.006 | 0.823 | TRUE | 1.39E-86 | 29.738 | 0.796 | 29.789 | 0.827 |

| Sleep duration | -0.003 | 0.909 | TRUE | 8.00E-132 | 66.665 | 0.489 | 66.678 | 0.523 |

| Nap during day | 0.024 | 0.253 | TRUE | 3.94E-198 | 64.089 | 0.948 | 65.416 | 0.943 |

| Morning/evening person (chronotype) | -0.008 | 0.629 | TRUE | 0 | 182.183 | 0.029 | 182.473 | 0.032 |

| Daytime dozing/sleeping (narcolepsy) | 0.030 | 0.585 | TRUE | 9.87E-52 | 46.276 | 0.022 | 46.763 | 0.026 |

| Generalized epilepsy | ||||||||

| Getting up in morning | -0.024 | 0.338 | TRUE | 1.43E-88 | 28.636 | 0.804 | 29.580 | 0.802 |

| Sleeplessness/insomnia | -0.020 | 0.290 | TRUE | 3.51E-83 | 35.056 | 0.560 | 36.210 | 0.552 |

| Sleep duration | -0.021 | 0.262 | TRUE | 2.27E-135 | 59.197 | 0.740 | 60.475 | 0.730 |

| Nap during day | 0.019 | 0.289 | TRUE | 6.22E-175 | 111.083 | 0.026 | 112.587 | 0.024 |

| Morning/evening person (chronotype) | 0.004 | 0.704 | TRUE | 0 | 170.123 | 0.103 | 170.289 | 0.112 |

| Daytime dozing/sleeping (narcolepsy) | -0.010 | 0.753 | TRUE | 2.02E-59 | 30.470 | 0.391 | 30.576 | 0.436 |

| East Asians | ||||||||

| Epilepsy | ||||||||

| Sleep apnoea | - | - | TRUE | 6.44E-06 | 0.091 | 0.763 | - | - |

| Sleep duration | -0.082 | 0.419 | TRUE | 2.03E-27 | 1.765 | 0.623 | 0.745 | 0.689 |

| Morning/evening person (chronotype) | -0.331 | 0.493 | TRUE | 1.33E-15 | 3.180 | 0.204 | 1.555 | 0.212 |

| Sleeplessness/insomnia | -0.055 | 0.341 | TRUE | 7.72E-36 | 2.668 | 0.849 | 1.561 | 0.906 |

| Daytime dozing/sleeping (narcolepsy) | 0.116 | 0.223 | TRUE | 7.09E-30 | 5.691 | 0.223 | 3.193 | 0.363 |

| Variables | SNPs (n) | Fixed effects | Multiplicative random effects | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | P | OR (95%CI) | P | ||

| Europeans | |||||

| Epilepsy | |||||

| Getting up in morning | 38 | 0.354 (0.212-0.589) | 0.000 | 0.354 (0.198-0.631) | 0.000 |

| Sleeplessness/insomnia | 39 | 1.367 (0.770-2.427) | 0.285 | 1.367 (0.884-2.115) | 0.160 |

| Sleep duration | 69 | 0.950 (0.616-1.464) | 0.815 | 0.950 (0.595-1.516) | 0.829 |

| Nap during day | 86 | 1.152 (0.716-1.852) | 0.559 | 1.152 (0.702-1.891) | 0.576 |

| Morning/evening person (chronotype) | 150 | 1.371 (1.105-1.702) | 0.004 | 1.371 (1.082-1.739) | 0.009 |

| Daytime dozing/sleeping (narcolepsy) | 31 | 1.305 (0.487-3.494) | 0.597 | 1.305 (0.437-3.897) | 0.634 |

| Focal epilepsy | |||||

| Getting up in morning | 38 | 0.304 (0.084-1.102) | 0.070 | 0.304 (0.095-0.971) | 0.045 |

| Sleeplessness/insomnia | 39 | 0.766 (0.179-3.268) | 0.719 | 0.766 (0.212-2.768) | 0.684 |

| Sleep duration | 69 | 0.811 (0.272-2.419) | 0.707 | 0.811 (0.275-2.394) | 0.704 |

| Nap during day | 86 | 0.405 (0.122-1.343) | 0.139 | 0.405 (0.141-1.159) | 0.092 |

| Morning/evening person (chronotype) | 150 | 1.723 (0.999-2.971) | 0.051 | 1.723 (0.942-3.149) | 0.077 |

| Daytime dozing/sleeping (narcolepsy) | 31 | 0.407 (0.034-4.903) | 0.479 | 0.407 (0.018-9.099) | 0.571 |

| Generalized epilepsy | |||||

| Getting up in morning | 38 | 0.256 (0.101-0.651) | 0.004 | 0.256 (0.111-0.590) | 0.001 |

| Sleeplessness/insomnia | 39 | 2.223 (0.777-6.355) | 0.136 | 2.223 (0.797-6.197) | 0.127 |

| Sleep duration | 69 | 1.130 (0.512-2.494) | 0.762 | 1.130 (0.536-2.384) | 0.748 |

| Nap during day | 86 | 0.729 (0.306-1.737) | 0.475 | 0.729 (0.268-1.981) | 0.535 |

| Morning/evening person (chronotype) |

150 | 1.618 (1.090-2.401) | 0.017 | 1.618 (1.061-2.467) | 0.025 |

| Daytime dozing/sleeping (narcolepsy) | 31 | 1.584 (0.261-9.604) | 0.617 | 1.584 (0.257-9.771) | 0.620 |

| East Asians | |||||

| Epilepsy | |||||

| Sleep apnoea | 2 | 0.970 (0.849-1.109) | 0.659 | 0.970 (0.932-1.010) | 0.143 |

| Sleep duration | 4 | 1.111 (0.827-1.492) | 0.485 | 1.111 (0.886-1.393) | 0.363 |

| Morning/evening person (chronotype) | 3 | 1.112 (0.852-1.450) | 0.434 | 1.112 (0.795-1.554) | 0.535 |

| Sleeplessness/insomnia | 7 | 1.381 (1.039-1.837) | 0.026 | 1.381 (1.142-1.671) | 0.001 |

| Daytime dozing/sleeping (narcolepsy) | 5 | 0.899 (0.577-1.402) | 0.639 | 0.899 (0.529-1.527) | 0.694 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).