1. Introduction

Schizophrenia (SZ), a highly incapacitating mental disorder, is estimated to afflict around 1% of the worldwide populace[

1], being widely acknowledged as the most severe among all mental illnesses[

2]. This complex and multifaceted disorder is typified by significant impairments in language acquisition, working memory, executive function, and processing speed[

3]. SZ is a mental disorder with a significant hereditary component, characterized by a wide range of genetic variations including both common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and rare mutations[

4,

5,

6]. Furthermore, advancements in molecular biology research have led to the identification of numerous risk genes associated with SZ, as well as genetic evidence supporting familial transmission. These findings further substantiate the role of genetics in the development of SZ and provide compelling evidence for comprehending the susceptibility to SZ from a genetic variation perspective[

7,

8]. In summary, SZ is a complex disorder influenced by multiple genes, as supported by genetic variants[

9]. Therefore, exploring the origins of psychiatric disorders or identifying potential therapeutic targets using the framework of genetic variants has substantial practical implications. Remarkably, despite extensive research conducted over several decades, the underlying pathological mechanisms of SZ still lack comprehensive understanding.

The endogenous pool of carnitine consists of Levo-carnitine (LC) and acylcarnitine, wherein LC serves as the active form for carnitine while acylcarnitine is a derivative states derived from LC[

10,

11]. LC plays a crucial role in the β-oxidation of fatty acids within the human body[

12,

13], and its synthesis occurs via biosynthesis, utilizing the amino acids lysine and methionine[

14,

15]. Among the derivative states in the LC pool, acetyl-LC (ALC), propionyl-LC (PLC), and isovaleryl-LC (ILC) are three types that exhibit significant biological activity and have garnered attention. LC is ubiquitously present in the majority of cells within the human body[

16], and assumes a vital role in upholding the integrity of cell membranes and exhibits specific functionalities within mitochondria[

17]. Prior investigations have substantiated that an insufficiency of LC results in the enlargement of astrocytes and the expansion of mitochondria in nerve cells[

18]. The presence of mitochondrial dysfunction in schizophrenia is substantiated by a confluence of evidence derived from genetic and peripheral investigations[

19]. This implies that LC may play a role in the pathological mechanisms underlying SZ, exerting an impact on the structural and energetic metabolism aspects of nerve cells. Furthermore, the study conducted by Kriisa et al. posited that impairment in LC function could potentially give rise to psychiatric disorders, including SZ[

20]. In a prospective cohort study, the efficacy of olanzapine, the primary antipsychotic medication prescribed for individuals with SZ, was observed to significantly diminish the concentrations of LC metabolites in patients with SZ. Additionally, the reduction in LC metabolite levels exhibited a significant correlation with cognitive enhancement subsequent to treatment[

21]. Acyl-LC is an endogenous compound that is prominently present in various bodily tissues, including muscles, the brain, and sperm. The significance and neuroprotective properties of these carnitines have been extensively validated through contemporary scientific investigations. In light of observational research, the collective evidence substantiates the potential involvement of LC and its derivatives in the etiology, progression, and therapeutic intervention of SZ. [

22]Nevertheless, the existence of a definitive causal association between the two remains uncertain.

In recent years, the employment of Mendelian randomization (MR) has facilitated the ability to deduce causal connections between modifiable environmental exposures and outcomes, thus garnering growing attention[

23]. MR leverages genetic variation found in SNPs as instrumental variables (IVs) within observational contexts. By virtue of genetic variations being randomly allocated during gamete formation and being unaffected by environmental and lifestyle factors, the estimates derived from MR exhibit reduced vulnerability to confounding bias. Moreover, it is imperative that the individual’s lineage genotype is established prior to examining the outcome of interest, and the measurement of genetic variants must be conducted with utmost accuracy. This meticulous approach in conducting MR analysis reduces the susceptibility to biases arising from reverse causation and measurement errors. Consequently, we have chosen to investigate the causal association between different subtypes of LC, as determined by genetic factors, and the susceptibility to SZ using a two-sample bidirectional MR analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

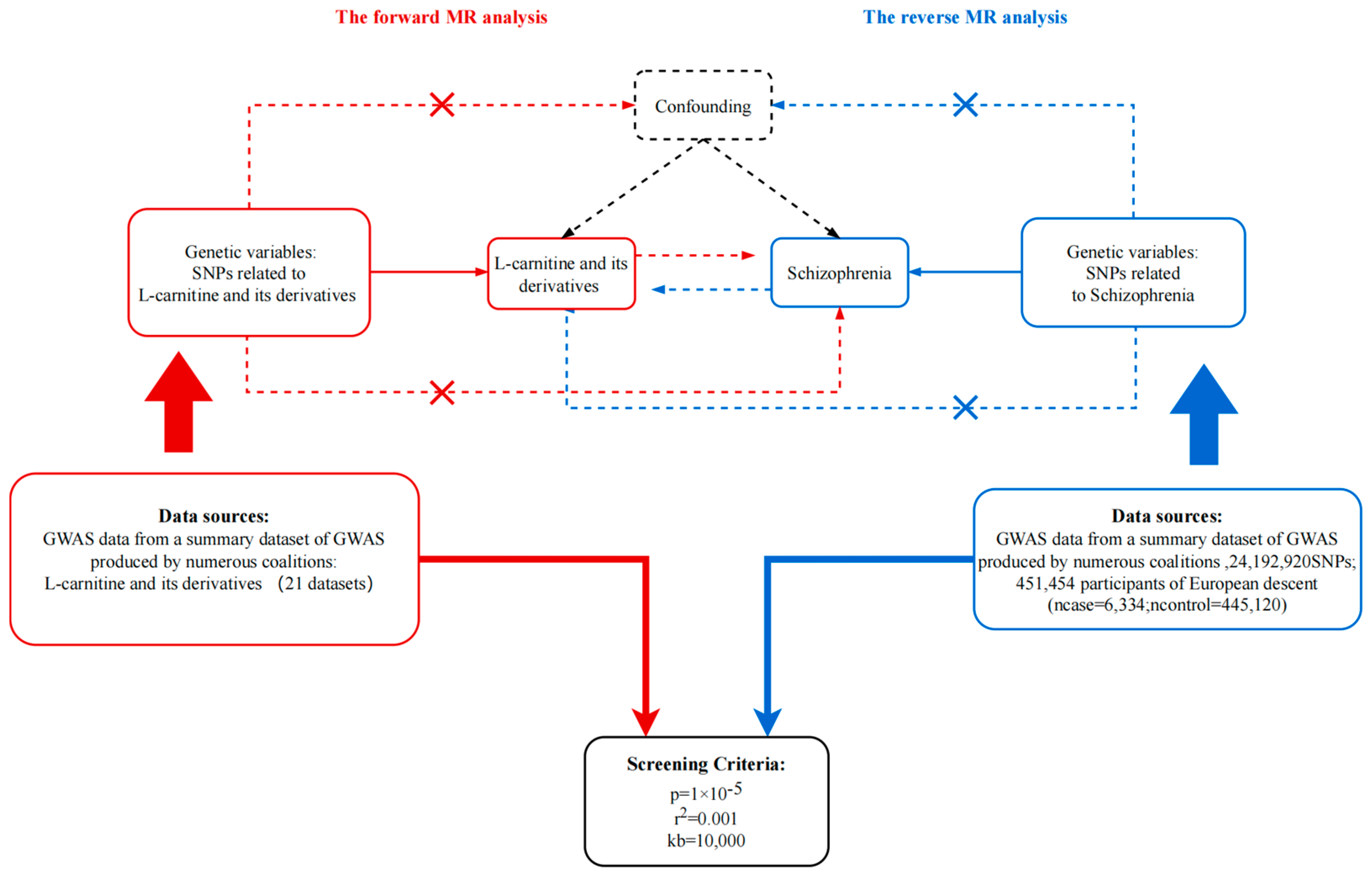

In order to assess the potential causal relationship between different derivatives of LC and SZ, a Two-sample MR analysis was conducted. This analysis was guided by three fundamental principles[

24]: (1) The use of SNPs identified through genome-wide association studies (GWAS) as IVs for the exposure variable; (2) Ensuring that the IVs are not associated with confounding factors; (3) Confirming that the IVs solely influence the risk of the outcome through their association with the exposure, without exerting a direct impact on the outcome itself. The forward MR analysis primarily aimed to examine the correlation between LC and its derivatives as the exposure, and SZ as the primary outcome. Conversely, in reverse analysis, SZ was considered as the exposure variable, while LC and its derivatives were regarded as the outcome variables.

Figure 1.

Principles of bidirectional mendelian randomization study and our study design. MR, Mendelian randomization; GWAS, genome-wide association studies. p, r2, and kb represent the parameters in the “TwoSample” R package.

Figure 1.

Principles of bidirectional mendelian randomization study and our study design. MR, Mendelian randomization; GWAS, genome-wide association studies. p, r2, and kb represent the parameters in the “TwoSample” R package.

2.2. Data Sources

For the purpose of forward MR analysis, the keywords "carnitine" and "schizophrenia" were employed to retrieve data from the OpenGWAS database (

https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/). The research data consisted of the European population with the most substantial sample size or number of cases, where LC and its derivatives data were considered as the exposure, and SZ related data served as the outcome. Finally, a total of[

25] datasets pertaining to LC and its derivative states, along with one data set specifically addressing SZ. The detailed information for each data set can be found in

Table s1 [

26,

27].

2.3. Identified Ivs

Firstly, IVs were selected from the exposure data using a quality control procedure. The “TwoSample” R package in the R software was utilized to extract IVs associated with exposure by setting parameters (P=5e-8, clump=True, r2=0.001, kb=10000)[

28]. Due to the inherent uncertainty regarding the causality of SZ, potential confounding variables related to exposure-associated IVs were not adequately controlled for, and we employed a filtration process to eliminate and exclude confounding variables specifically linked to SZ utilizing "phenoscanner" R package. Hence, the efficacy of IVs was assessed by examining the F statistics, which quantifies the level of association between the SNPs and the exposure. Subsequently, relevant information pertaining to IVs closely aligned with exposure was extracted from the outcome data set. After harmonized the extracted data, a screening process was implemented to exclude IVs that were closely associated with outcomes (P<5e-8) from the data. In order to clarify the potential impact of outliers in IVs on the MR analysis results, the MR-PRSSO package[

29] was utilized to verify the presence of outliers in the harmonized data and subsequently eliminate them.

2.4. MR analysis

After completing the aforementioned procedures, we utilized five distinct methodologies (MR-Egger[

30], weighted median[

31], IVW[

32], simple mode[

33], and weighted mode[

33]) to evaluate the overall effect outcomes during the MR analyses. The IVW approach was prioritized for result interpretation. It is crucial to ensure that the outcomes derived from these five MR analyses demonstrate consistent positive or negative effects, which can be determined by examining the b value. A P value below 0.05 signifies statistical significance within the framework of MR analysis.

2.5. Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analysis incorporates the examination of heterogeneity and pleiotropy, as well as the assessment of the impact of an individual SNP on the overall outcomes of MR analysis. Heterogeneity was evaluated using ME-Egger methods, specifically by implementing the Q-test[

25]. In instances where heterogeneity was detected, a random effects model was utilized to reevaluate the magnitude of the effect. Moreover, the representation of heterogeneity was achieved by employing Scatter plot and Funnel plot techniques. Additionally, the presence of horizontal pleiotropy in the IVs was assessed using the Egger intercept method. Furthermore, the influence of excluding a single SNP on the results of the MR analysis was examined through the application of the leave-one-out method.

2.6. Evaluation of sample overlap bias

In order to further substantiate the influence of sample overlap on the outcomes of MR analysis, we employed the mrmsample overlap R software package to assess the bias and Type I error associated with varying levels of sample overlap rates. If the findings of this examination demonstrate that the bias and Type I error persist at a relatively consistent level despite an increase in the repetition rate of samples, it indicates the relative robustness of the MR analysis results.

3.1. Forward analysis

3.1.1. Forward MR analysis

Based on the findings from the forward MR analysis, it is apparent that LC and its derivatives demonstrate inconsistent causal effects on SZ, as indicated in

Table 1. Among the results from three primary derivatives of LC (ALC, PLC, ILC), only ILC exhibits a negative causal relationship with SZ (

Table 1, OR=0.435, 95% CI: 0.247-0.765, P

IVW=0.004). Conversely, the remaining substances do not exhibit a significant causal relationship with SZ(

Table 1, P

IVW>0.05). Detailed information regarding the IVs employed in the analysis program can be found in the

Supplementary Materials 1.

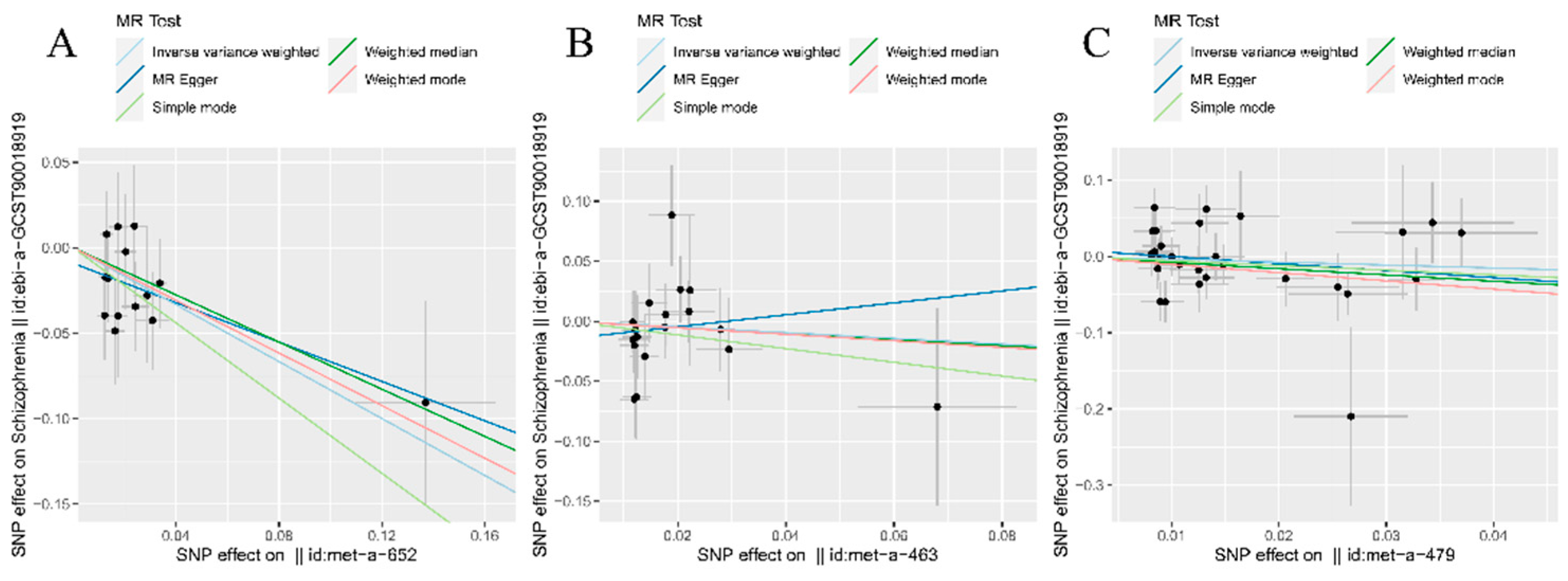

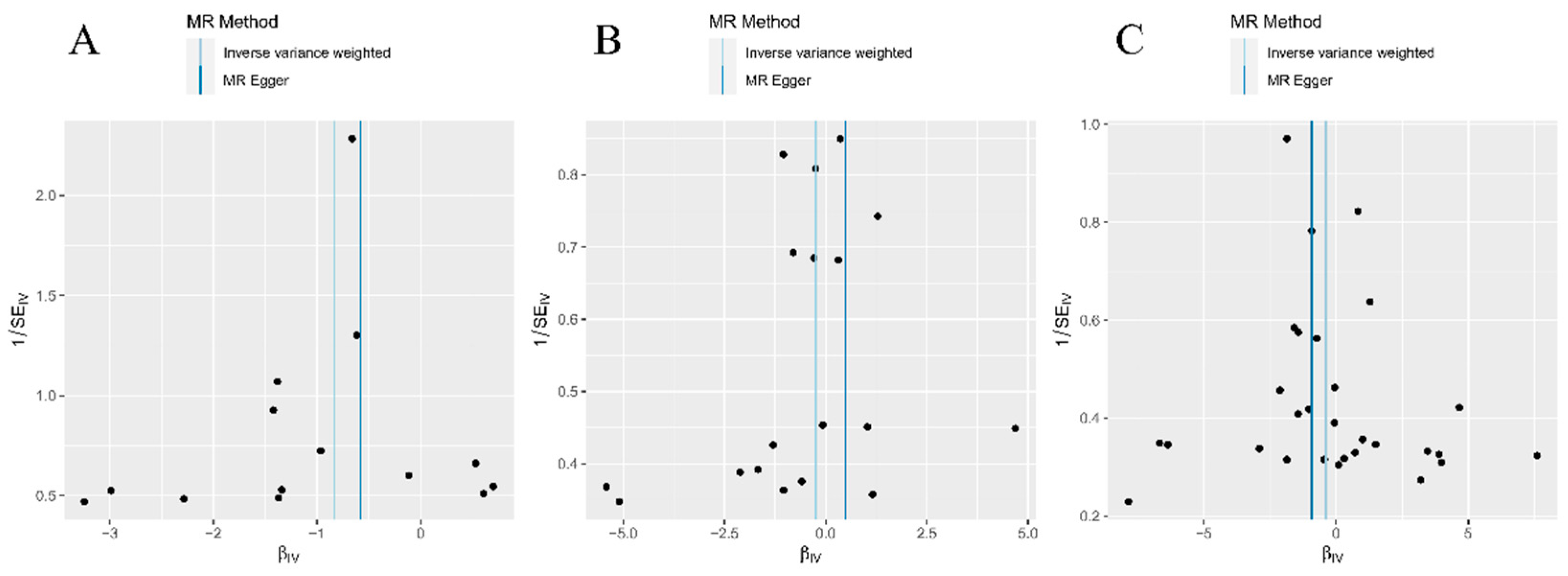

3.1.2. Forward sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity analysis results provided confirmation that there was no statistically significant presence of pleiotropy or heterogeneity in the IVs associated with each groups during the forward MR analysis process (

Table s2, P>0.05). Furthermore, the scatter plot distributions indicated potential linear associations within all three analysis groups (

Figure 2A–C). Moreover, the absence of conspicuous abnormal SNP distributions was also verified through examination of the funnel plot (

Figure 3A–C). The varying impact of individual IVs on SZ is evident across different IVs (

Supplementary Materials 2). However, employing the leave-one-method for evaluation substantiates that the influence of a single IVs on the main findings of MR analysis remains insignificant (

Supplementary Materials 3). These findings collectively affirm the robustness and dependability of the analytical outcomes in the present study.

3.1.3. Sample overlap bias in forward analysis

The results indicated a slight increase in both bias and type Ⅰ error with an increasing rate of sample duplication. However, the overall level remained relatively stable (

Supplementary Materials 4). These findings suggest that there is no significant duplication of samples among the population included in this study, thereby reinforcing the reliability and validity of our MR analysis results.

3.2. Reverse analysis

The findings from the reverse MR analysis suggest that there is no statistically significant causal association between schizophrenia and L-carnitine and its derivatives (Table 2, P>0.05). Furthermore, the sensitivity analysis results support the absence of significant pleiotropy and heterogeneity among the instrumental variables in each groups (

Table s3, P>0.05). The diverse effects of individual IVs on SZ are apparent when considering different IVs (see

Supplementary Materials 2). Nevertheless, employing the leave-one-out method for evaluation confirms that the impact of a single IV on the primary outcomes of MR analysis remains statistically insignificant (see

Supplementary Materials 3). Additionally, the examination of sample overlap’s influence on the results of the MR analysis yielded comparable findings to the forward analysis (see

Supplementary Materials 4).

Table 3.

Reverse MR results of causality of SZ on LC and its derivatives. N.SNP, number of single nucleotide polymorphisms; OR, odds ratio; PIVW, P for inverse-variance weighted method; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Table 3.

Reverse MR results of causality of SZ on LC and its derivatives. N.SNP, number of single nucleotide polymorphisms; OR, odds ratio; PIVW, P for inverse-variance weighted method; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

| Outcome |

N.SNP

|

PIVW

|

OR |

95%CI |

| Carnitine |

10 |

0.74 |

1.01 |

0.99-1.01 |

| Palmitoylcarnitine |

2 |

0.79 |

0.99 |

0.94-1.05 |

| Acetylcarnitine |

8 |

0.32 |

0.99 |

0.97-1.01 |

| Isovalerylcarnitine |

4 |

0.55 |

0.99 |

0.96-1.02 |

| Hexanoylcarnitine |

3 |

0.94 |

1.02 |

0.97-1.03 |

| Butyrylcarnitine |

3 |

0.80 |

0.99 |

0.95-1.04 |

| Propionylcarnitine |

9 |

0.37 |

0.99 |

0.98-1.01 |

| 3-dehydrocarnitine |

5 |

0.79 |

1.01 |

0.98-1.02 |

| Isobutyrylcarnitine |

4 |

0.78 |

0.99 |

0.96-1.03 |

| Octanoylcarnitine |

4 |

0.69 |

1.01 |

0.97-1.04 |

| Decanoylcarnitine |

2 |

0.79 |

1.01 |

0.96-1.05 |

| Stearoylcarnitine |

3 |

0.84 |

1.01 |

0.97-1.04 |

| Laurylcarnitine |

1 |

0.88 |

1.01 |

0.93-1.09 |

| Oleoylcarnitine |

6 |

0.88 |

1.01 |

0.98-1.02 |

| X-13431--nonanoylcarnitine |

3 |

0.89 |

1.01 |

0.96-1.04 |

| 2-methylbutyroylcarnitine |

6 |

0.88 |

0.99 |

0.97-1.02 |

| Hydroxyisovaleroyl carnitine |

7 |

0.98 |

1.00 |

0.97-1.02 |

| Glutaroyl carnitine |

3 |

0.64 |

1.00 |

0.98-1.02 |

| 2-tetradecenoyl carnitine |

4 |

0.83 |

1.00 |

0.97-1.04 |

| Succinylcarnitine |

1 |

0.82 |

0.99 |

0.97-1.03 |

| Cis-4-decenoyl carnitine |

4 |

0.62 |

1.01 |

0.98-1.04 |

4. Discussion

To determine if there is a bidirectional causal relationship between L-carnitine’s subtypes and its related metabolites and schizophrenia, two-sample MR analysis was performed. Our findings provide further depth to prior observations of metabolic disturbances in schizophrenia, as L-carnitine is an essential component of beta-oxidation of fatty acids, essential for the production of cellular energy. The results indicate a strong negative relationship between ILC and schizophrenia, suggesting that higher levels of ILC may protect against schizophrenia onset or severity. We also found no causal link between any L-carnitine and schizophrenia in the reverse two-sample MR analysis, demonstrating the stability of our experiments.

Previous research has predominantly concentrated on the broad concept of carnitine and its relevance to neurological disorders. It has been previously ascertained that individuals with schizophrenia have a predisposition to metabolic irregularities and bioenergetic dysfunction[

34]. Notably, Cao B. et al[

35,

36,

37] have implicated ALC in the cellular bioenergetic abnormalities observed in schizophrenia, suggesting that acyl-carnitines may serve as prospective subjects for future investigations into their involvement in the pathoetiology of schizophrenia.

According to the study conducted by M.A. VIRMANI and R. BiSELLIT et al[

38], it was observed that L-carnitine and ALC possess the ability to impede neurotoxicity resulting from various forms of mitochondrial dysfunction, such as uncoupling or inhibition of oxidative phosphorylation. In a separate investigation by M. Pennisi, G. Lanza et al[

39], the involvement of ALC in dementia was explored, revealing its potential in decelerating cognitive decline. The underlying mechanisms behind this phenomenon may encompass the restoration of cellular membrane and synaptic functionality, promotion of mitochondrial energy metabolism, safeguarding against toxins, and exertion of neurotrophic effects. According to preclinical and laboratory findings, ALC has been investigated in human clinical trials as an adjunctive therapy for patients with dementia or MCI[

40,

41], geriatric depression[

42,

43], and various other prevalent medical conditions. These trials provide support for the notion that certain forms of L-carnitine supplementation may have a mitigating effect. Consequently, these pieces of evidence imply that L-carnitine and its derivatives possess extensive therapeutic possibilities in the management of schizophrenia.

Previous observational studies have demonstrated that the activity of nerve growth factor (NGF) significantly impacts the maturation of neurons and sustains the differentiation status of diverse neurons in the peripheral and central nervous systems. In their experiment, J. W. Pettegrew et al. discovered that aged rats treated with ALC exhibited amelioration of the age-related decline in NGF-binding capacity observed in the hippocampus and basal forebrain regions. This finding implies that specific sublines of L-carnitine may enhance the responsiveness of neurons to neurotrophic factors within the central nervous system in older rats. Furthermore, ALCAR exerts an impact on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis within the brain, thereby potentially mitigating pathological brain deterioration under stressful circumstances[

44]. Certain variants of L-carnitine additionally modulate the activity of nerve growth factor (NGF) and various hormones, while also playing a role in regulating synaptic morphology and transmission of diverse neurotransmitters, including acetylcholine[

45,

46]. These findings suggest that specific sublines of L-carnitine possess the ability to affect multiple targets within the central nervous system. Additionally, scientific evidence substantiates the notion that L-carnitine can influence concentrations of neurotransmitters. Based on the findings reported by various sources[

47], the utilization of ALC in a child injury model has been shown to enhance mitochondrial function, mitigate brain swelling, and prevent tissue loss[

48,

49,

50]. Furthermore, sustained administration of ALC has demonstrated the potential to enhance the cerebral energy state in healthy mice[

51]. Additionally, primary cilia play a crucial role in minimizing oxidative stress and safeguarding neuronal cells41. Building upon the aforementioned studies, our investigation delved into the causal association between select sublines of L-carnitine and schizophrenia. Our findings revealed a consistent and noteworthy inverse correlation between ILC and schizophrenia, thereby bolstering our hypothesis that certain sublines of L-carnitine confer a safeguarding influence against schizophrenia.

The study’s merits encompass the utilization of two-sample MR analysis, which, in contrast to observational studies, can effectively mitigate the influence of confounding variables and reverse causality. Leveraging publicly accessible GWAS summary statistics data, we derived advantages from a substantial sample size, thereby augmenting the accuracy of our estimations and the statistical robustness of our discoveries. This methodological framework guarantees a heightened level of result reliability.

However, it is imperative to acknowledge the constraints inherent in our study. Firstly, our findings predominantly apply to populations of European ancestry. Although this approach may alleviate biases stemming from population stratification, the applicability of our results to other ethnic groups is yet to be ascertained.

Secondly, it is important to acknowledge that our analysis, like any other MR study, is susceptible to potential unobserved pleiotropy, which may introduce biases into our conclusions. Therefore, it is crucial to conduct additional comprehensive research, incorporating various methodological approaches and diverse populations, to validate and enhance the accuracy of our findings.

5. Conclusions

Our study aims to evaluate the causal association between different subtypes of L-carnitine and related metabolites, as determined by genetic factors, and the risk of developing schizophrenia. This analysis utilizes a two-sample Mendelian randomization approach, which reveals a statistically significant inverse correlation between ILC levels and the occurrence of schizophrenia. These results suggest that higher levels of ILC may be associated with a decreased risk of developing schizophrenia. Consequently, our findings suggest that ILC may have potential implications in the prevention and treatment of schizophrenia, thereby providing a novel avenue for future research exploring the relationship between metabolism and this psychiatric disorder.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org. Supplementary Materials 1 Details for all instrumental variables in the study; Supplementary Materials 2 Single SNP forest plot of MR analysis; Supplementary Materials 3 Leave one out plot of MR analysis; Supplementary Materials 4 Sample overlapping bias plot of MR analysis; Table s1 data sources; Table s2 Forward sensitivity analysis results; Table s3 Reserve sensitivity analysis results;

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, HY.Q. and ZJ.F.; methodology, ZC.Z.; software, ZC.Z.; validation, HY.Q.; formal analysis, HY.Q.; investigation, HY.Q.; resources, HY.Q.; data curation, HY.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, HY.Q., ZC.Z., TX.W., HR.R.; writing—review and editing, HY.Q., ZJ.F.; visualization, HY.Q.; supervision, HY.Q.; project administration, ZJ.F.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Candidate data were obtained from the openGWAS server, could find in “

https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/”. All data used in this study are available in the public repository. The code involved in the data analysis process can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the team of OpenGWAS and UK Biobank database for making the summary data publicly available, and we would like to acknowledge the principal investigators of the studies who made their data openly accessible for research.

References

- Saha, S.; Chant, D.; Welham, J.; McGrath, J. A systematic review of the prevalence of schizophrenia. PLoS Med 2005, 2, e141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauhar, S.; Johnstone, M.; McKenna, P.J. Schizophrenia. Lancet 2022, 399, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiu, M.H.; Li, Z.; Chen, D.C.; Chen, S.; Curbo, M.E.; Wu, H.E.; Tong, Y.S.; Tan, S.P.; Zhang, X.Y. Interrelationships Between BDNF, Superoxide Dismutase, and Cognitive Impairment in Drug-Naive First-Episode Patients With Schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2020, 46, 1498–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, T.; McClellan, J.M.; McCarthy, S.E.; Addington, A.M.; Pierce, S.B.; Cooper, G.M.; Nord, A.S.; Kusenda, M.; Malhotra, D.; Bhandari, A.; et al. Rare structural variants disrupt multiple genes in neurodevelopmental pathways in schizophrenia. Science 2008, 320, 539–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purcell, S.M.; Wray, N.R.; Stone, J.L.; Visscher, P.M.; O’Donovan, M.C.; Sullivan, P.F.; Sklar, P. Common polygenic variation contributes to risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Nature 2009, 460, 748–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fromer, M.; Pocklington, A.J.; Kavanagh, D.H.; Williams, H.J.; Dwyer, S.; Gormley, P.; Georgieva, L.; Rees, E.; Palta, P.; Ruderfer, D.M.; et al. De novo mutations in schizophrenia implicate synaptic networks. Nature 2014, 506, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature 2014, 511, 421–427. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, P.J.; Weinberger, D.R. Schizophrenia genes, gene expression, and neuropathology: on the matter of their convergence. Mol Psychiatry 2005, 10, 40–68, image 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Rolls, E.T.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Jiao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Gong, W.; Ma, Z.; Gong, F.; Wan, L. Multi-scale analysis of schizophrenia risk genes, brain structure, and clinical symptoms reveals integrative clues for subtyping schizophrenia patients. J Mol Cell Biol 2019, 11, 678–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, A.F.; Dongier, A.; Colson, C.; Minguet, P.; Defraigne, J.O.; Minguet, G.; Misset, B.; Boemer, F. Serum Acylcarnitines Profile in Critically Ill Survivors According to Illness Severity and ICU Length of Stay: An Observational Study. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Emidio, G.; Rea, F.; Placidi, M.; Rossi, G.; Cocciolone, D.; Virmani, A.; Macchiarelli, G.; Palmerini, M.G.; D’Alessandro, A.M.; Artini, P.G.; et al. Regulatory Functions of L-Carnitine, Acetyl, and Propionyl L-Carnitine in a PCOS Mouse Model: Focus on Antioxidant/Antiglycative Molecular Pathways in the Ovarian Microenvironment. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salic, K.; Gart, E.; Seidel, F.; Verschuren, L.; Caspers, M.; van Duyvenvoorde, W.; Wong, K.E.; Keijer, J.; Bobeldijk-Pastorova, I.; Wielinga, P.Y.; et al. Combined Treatment with L-Carnitine and Nicotinamide Riboside Improves Hepatic Metabolism and Attenuates Obesity and Liver Steatosis. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawicka, A.K.; Renzi, G.; Olek, R.A. The bright and the dark sides of L-carnitine supplementation: a systematic review. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2020, 17, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, N.; Yang, M.; Zhou, M.; Xiao, J.; Guo, J.; He, L. L-carnitine for cognitive enhancement in people without cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017, 3, Cd009374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, P.J.; Wang, H.D.; Tseng, Y.C.; Pan, S.W.; Sampurna, B.P.; Jong, Y.J.; Yuh, C.H. L-Carnitine ameliorates congenital myopathy in a tropomyosin 3 de novo mutation transgenic zebrafish. J Biomed Sci 2021, 28, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flanagan, J.L.; Simmons, P.A.; Vehige, J.; Willcox, M.D.; Garrett, Q. Role of carnitine in disease. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2010, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kępka, A.; Ochocińska, A.; Chojnowska, S.; Borzym-Kluczyk, M.; Skorupa, E.; Knaś, M.; Waszkiewicz, N. Potential Role of L-Carnitine in Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Clin Med 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clay, H.B.; Sillivan, S.; Konradi, C. Mitochondrial dysfunction and pathology in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Int J Dev Neurosci 2011, 29, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasekaran, A.; Venkatasubramanian, G.; Berk, M.; Debnath, M. Mitochondrial dysfunction in schizophrenia: pathways, mechanisms and implications. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2015, 48, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriisa, K.; Leppik, L.; Balõtšev, R.; Ottas, A.; Soomets, U.; Koido, K.; Volke, V.; Innos, J.; Haring, L.; Vasar, E.; et al. Profiling of Acylcarnitines in First Episode Psychosis before and after Antipsychotic Treatment. J Proteome Res 2017, 16, 3558–3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Liu, H.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Xiu, M.; Li, S. Carnitine metabolites and cognitive improvement in patients with schizophrenia treated with olanzapine: a prospective longitudinal study. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14, 1255501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pekala, J.; Patkowska-Sokoła, B.; Bodkowski, R.; Jamroz, D.; Nowakowski, P.; Lochyński, S.; Librowski, T. L-carnitine--metabolic functions and meaning in humans life. Curr Drug Metab 2011, 12, 667–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawlor, D.A.; Harbord, R.M.; Sterne, J.A.; Timpson, N.; Davey Smith, G. Mendelian randomization: using genes as instruments for making causal inferences in epidemiology. Stat Med 2008, 27, 1133–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, K.W.; Chen, C.Y.; Stein, M.B.; Klimentidis, Y.C.; Wang, M.J.; Koenen, K.C.; Smoller, J.W. Assessment of Bidirectional Relationships Between Physical Activity and Depression Among Adults: A 2-Sample Mendelian Randomization Study. JAMA Psychiatry 2019, 76, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemani, G.; Bowden, J.; Davey Smith, G. Evaluating the potential role of pleiotropy in Mendelian randomization studies. Hum Mol Genet 2018, 27, R195–R208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, S.Y.; Fauman, E.B.; Petersen, A.K.; Krumsiek, J.; Santos, R.; Huang, J.; Arnold, M.; Erte, I.; Forgetta, V.; Yang, T.P.; et al. An atlas of genetic influences on human blood metabolites. Nat Genet 2014, 46, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakaue, S.; Kanai, M.; Tanigawa, Y.; Karjalainen, J.; Kurki, M.; Koshiba, S.; Narita, A.; Konuma, T.; Yamamoto, K.; Akiyama, M.; et al. A cross-population atlas of genetic associations for 220 human phenotypes. Nat Genet 2021, 53, 1415–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Lian, P.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, M.; Feng, Z. Causal Associations between Gut Microbiota and Different Types of Dyslipidemia: A Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization Study. 2023, 15, 4445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbanck, M.; Chen, C.Y.; Neale, B.; Do, R. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from Mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Nat Genet 2018, 50, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, J.; Davey Smith, G.; Burgess, S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. Int J Epidemiol 2015, 44, 512–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, J.; Davey Smith, G.; Haycock, P.C.; Burgess, S. Consistent Estimation in Mendelian Randomization with Some Invalid Instruments Using a Weighted Median Estimator. Genet Epidemiol 2016, 40, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davey Smith, G.; Hemani, G. Mendelian randomization: genetic anchors for causal inference in epidemiological studies. Hum Mol Genet 2014, 23, R89–R98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwig, F.P.; Davey Smith, G.; Bowden, J. Robust inference in summary data Mendelian randomization via the zero modal pleiotropy assumption. Int J Epidemiol 2017, 46, 1985–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thaker, G.K.; Carpenter, W.T., Jr. Advances in schizophrenia. Nat Med 2001, 7, 667–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, B.; Jin, M.; Brietzke, E.; McIntyre, R.S.; Wang, D.; Rosenblat, J.D.; Ragguett, R.M.; Zhang, C.; Sun, X.; Rong, C.; et al. Serum metabolic profiling using small molecular water-soluble metabolites in individuals with schizophrenia: A longitudinal study using a pre-post-treatment design. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2019, 73, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, B.; Wang, D.; Pan, Z.; McIntyre, R.S.; Brietzke, E.; Subramanieapillai, M.; Nozari, Y.; Wang, J. Metabolic profiling for water-soluble metabolites in patients with schizophrenia and healthy controls in a Chinese population: A case-control study. World J Biol Psychiatry 2020, 21, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virmani, M.A.; Biselli, R.; Spadoni, A.; Rossi, S.; Corsico, N.; Calvani, M.; Fattorossi, A.; De Simone, C.; Arrigoni-Martelli, E. Protective actions of L-carnitine and acetyl-L-carnitine on the neurotoxicity evoked by mitochondrial uncoupling or inhibitors. Pharmacol Res 1995, 32, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennisi, M.; Lanza, G.; Cantone, M.; D’Amico, E.; Fisicaro, F.; Puglisi, V.; Vinciguerra, L.; Bella, R.; Vicari, E.; Malaguarnera, G. Acetyl-L-Carnitine in Dementia and Other Cognitive Disorders: A Critical Update. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spagnoli, A.; Lucca, U.; Menasce, G.; Bandera, L.; Cizza, G.; Forloni, G.; Tettamanti, M.; Frattura, L.; Tiraboschi, P.; Comelli, M.; et al. Long-term acetyl-L-carnitine treatment in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1991, 41, 1726–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, M.; Bell, K.; Cote, L.; Dooneief, G.; Lawton, A.; Legler, L.; Marder, K.; Naini, A.; Stern, Y.; Mayeux, R. Double-blind Parallel Design Pilot Study of Acetyl Levocarnitine in Patients With Alzheimer’s Disease. Archives of Neurology 1992, 49, 1137–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bella, R.; Biondi, R.; Raffaele, R.; Pennisi, G. Effect of acetyl-L-carnitine on geriatric patients suffering from dysthymic disorders. Int J Clin Pharmacol Res 1990, 10, 355–360. [Google Scholar]

- Garzya, G.; Corallo, D.; Fiore, A.; Lecciso, G.; Petrelli, G.; Zotti, C. Evaluation of the effects of L-acetylcarnitine on senile patients suffering from depression. Drugs Exp Clin Res 1990, 16, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pettegrew, J.W.; Levine, J.; McClure, R.J. Acetyl-L-carnitine physical-chemical, metabolic, and therapeutic properties: relevance for its mode of action in Alzheimer’s disease and geriatric depression. Mol Psychiatry 2000, 5, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoni-Freddari, C.; Fattoretti, P.; Casoli, T.; Spagna, C.; Casell, U. Dynamic morphology of the synaptic junctional areas during aging: the effect of chronic acetyl-L-carnitine administration. Brain research 1994, 656, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoni-Freddari, C.; Fattoretti, P.; Caselli, U.; Paoloni, R. Acetylcarnitine modulation of the morphology of rat hippocampal synapses. Analytical and quantitative cytology and histology 1996, 18, 275–278. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, J.E.; Kim, J.B.; Jo, D.S.; Park, N.Y.; Kim, Y.H.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, S.H.; Son, M.; Kim, P.; et al. Carnitine Protects against MPP(+)-Induced Neurotoxicity and Inflammation by Promoting Primary Ciliogenesis in SH-SY5Y Cells. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, G.C.; McKenna, M.C. l-Carnitine and Acetyl-l-carnitine Roles and Neuroprotection in Developing Brain. Neurochemical Research 2017, 42, 1661–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scafidi, S.; Racz, J.; Hazelton, J.; McKenna, M.C.; Fiskum, G. Neuroprotection by Acetyl-L-Carnitine after Traumatic Injury to the Immature Rat Brain. Developmental Neuroscience 2011, 32, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Waddell, J.; Zhu, W.; Shi, D.; Marshall, A.D.; McKenna, M.C.; Gullapalli, R.P. In vivo longitudinal proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy on neonatal hypoxic-ischemic rat brain injury: Neuroprotective effects of acetyl-L-carnitine. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2015, 74, 1530–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeland, O.B.; Meisingset, T.W.; Borges, K.; Sonnewald, U. Chronic acetyl-L-carnitine alters brain energy metabolism and increases noradrenaline and serotonin content in healthy mice. Neurochem Int 2012, 61, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.-E.; Kang, G.M.; Min, S.H.; Jo, D.S.; Jung, Y.-K.; Kim, K.; Kim, M.-S.; Cho, D.-H. Primary cilia mediate mitochondrial stress responses to promote dopamine neuron survival in a Parkinson’s disease model. Cell Death & Disease 2019, 10, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).