1. Introduction

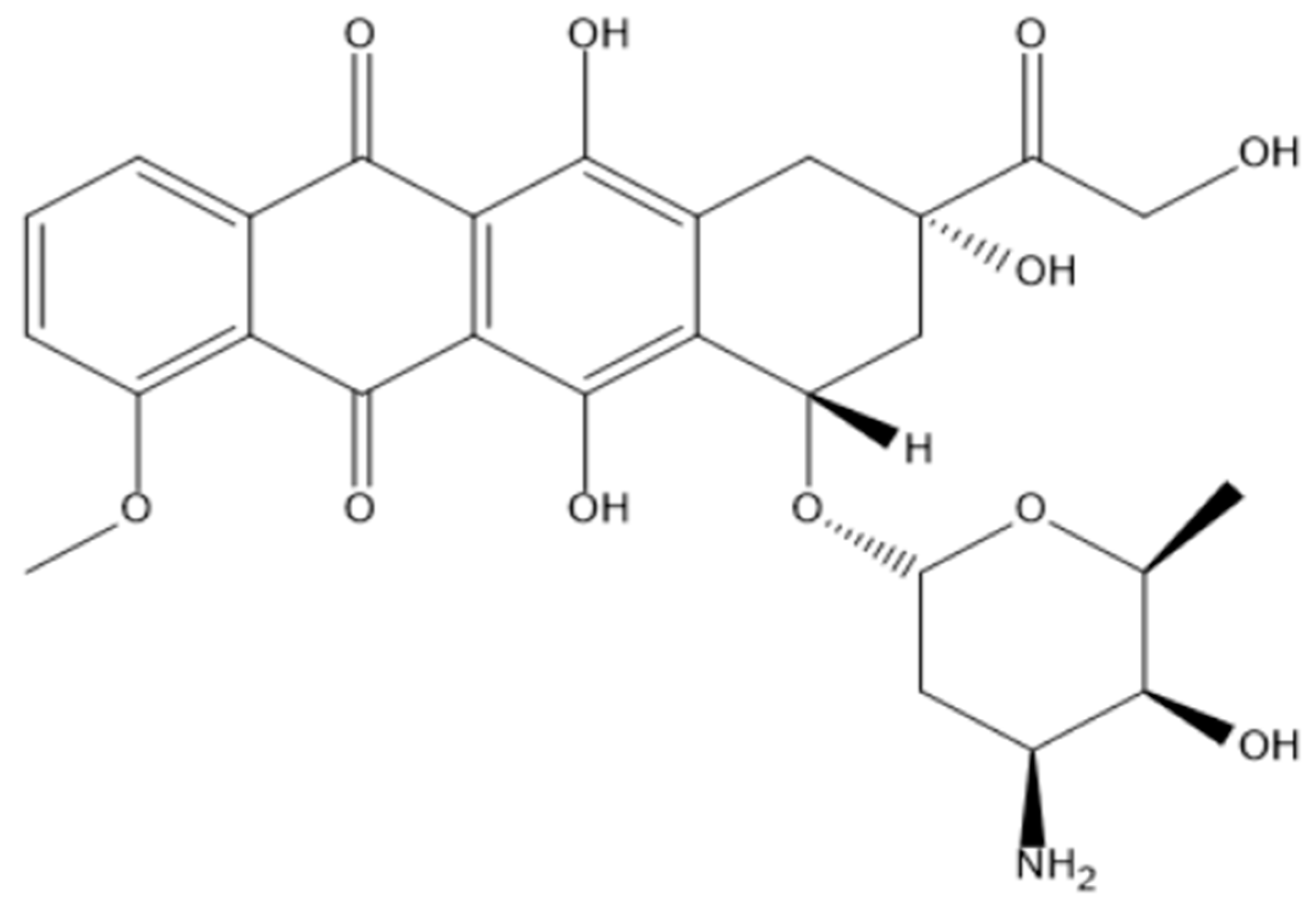

Doxorubicin (DOX,

Figure 1) is one of the most widely used drugs in the treatment of cancer in both adults and children. Initially, a compound called daunorubicin was derived from the

Streptomyces peucetius bacterium [

1]. It has been successfully used in cancer patients for almost 20 years when the drug was found to cause fatal cardiac arrest [

2]. Due to this serious side effect, daunorubicin was structurally modified to reduce its toxicity. The resulting compound was called doxorubicin. Nowadays, DOX is one of the first-line drugs in the treatment of breast, lung, bladder, thyroid, and bone tumours, as well as leukaemias and sarcomas [

3]. The downsides of doxorubicin therapy include fast excretion from the body and a low tumour-reaching rate, forcing the administration of higher doses. Consequently, this leads to a high cardiac toxicity level of the drug. For example, according to the protocol for the treatment of solid tumours, the maximum cumulative dose a patient can receive is 550 mg/m

2 every three weeks [

4]. At this dose, acute cardiac toxicity is recorded in 11% of patients. The cardiac toxicity then leads to the development of doxorubicin cardiomyopathy which frequently results in heart failure. Other serious side effects of DOX include alopecia, vomiting, bone marrow suppression, and constant fatigue [

5]. Due to the hydrophilicity of free doxorubicin, it can be readily absorbed in healthy tissues. As a result, the side effects are inevitable in intravenous administration.

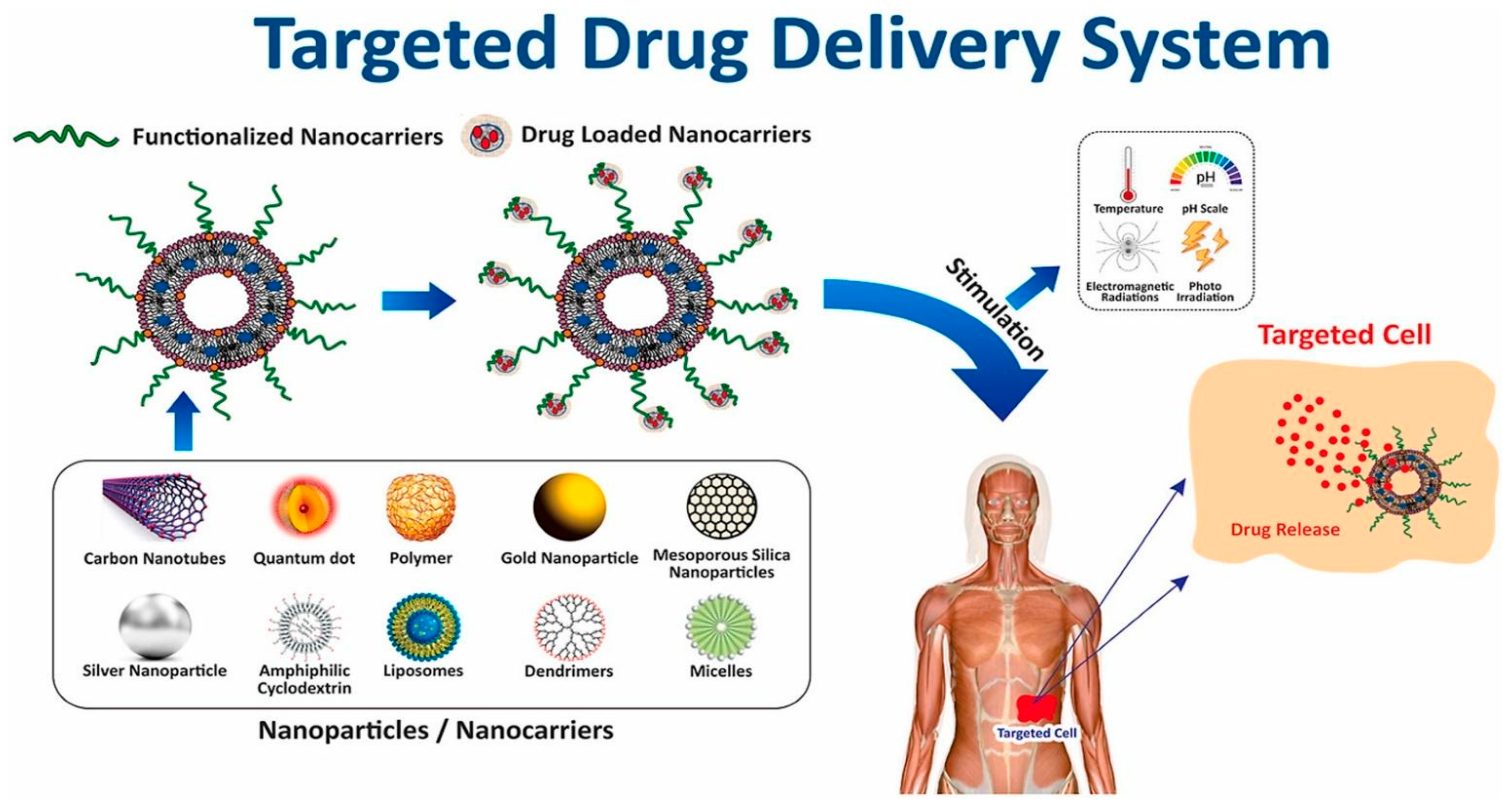

As such, there is a high need for targeted and controlled novel drug delivery systems that would alleviate the side effects of chemotherapy and would increase the treatment efficacy. Nowadays, several different carriers, such as quantum dots, carbon nanotubes, dendrimers, polymers, cyclodextrins, liposomes, micelles, and porous/non-porous nanoparticles (NPs) are available (

Figure 2) [

6]. The latter is of high interest due to several properties: good stability, low toxicity, easy synthesis routes, an ability to control their size, and most importantly – an ability to functionalize their surface with different molecules, including chemotherapy drugs [

7].

Doxorubicin can be conjugated to nanoparticles both covalently and non-covalently. Non-covalent conjugation involves the physical adsorption of the drug via electrostatic forces, van der Waals forces, or hydrogen bonding [

9]. Although non-covalent conjugation has an easier synthesis procedure and requires fewer chemicals, it was reported to have a low drug loading capacity (DLC) and a higher probability of drug leakage during blood circulation. This is due to non-covalent linkages being weaker compared to their covalent counterparts [

10]. Literature shows instances of 50% doxorubicin leaking prematurely in case of electrostatic attachment. This can seriously harm healthy tissues before reaching the target [

11]. A different study showed that 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein conjugated to polymeric NPs was very rapid: around 30% in the first 2 minutes [

12]. Such data shows that conjugated drugs could be possibly released prematurely, before reaching the target tissue. As such, this paper reviews the covalent conjugation of doxorubicin to three different types of nanoparticles - metallic, silica/organosilica, and polymeric, including their corresponding release mechanisms and rates.

2. Metallic Nanoparticles

Metallic nanoparticles are the most prevalent and the most studied type of doxorubicin delivery systems in the literature. The main reason for their popularity is their easy surface functionalization compared to other types of nanoparticles [

13]. Typical metals used for the synthesis of nanoparticles include gold, silver, and iron.

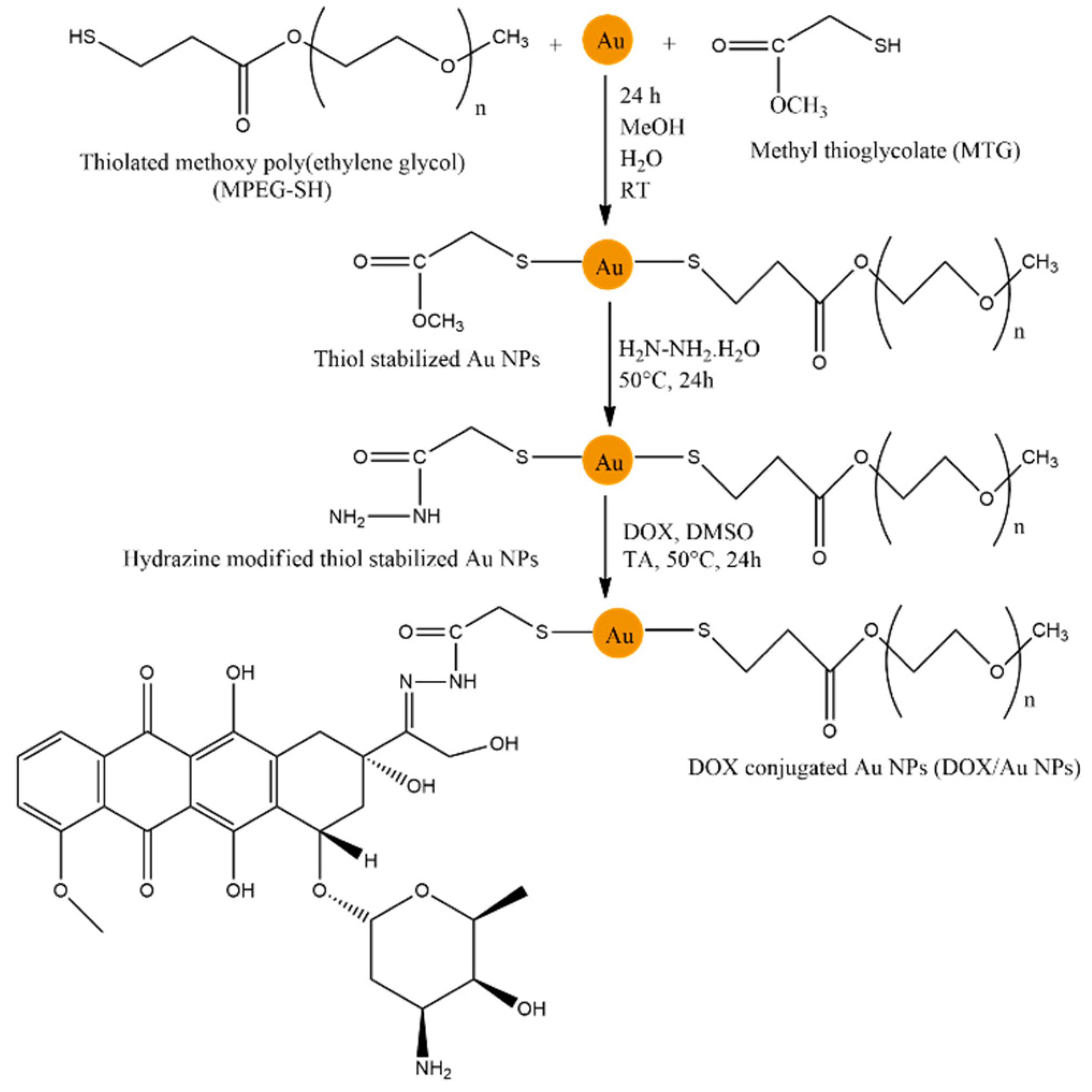

Among them, the covalent conjugation of doxorubicin to gold nanoparticles received significant attention. Successful covalent conjugation of DOX to gold nanoparticles was achieved via the formation of a hydrazone bond (

Figure 3) [

14]. First, the gold nanoparticles were stabilized using thiolated methoxy polyethylene glycol (MPEG-SH) and methyl thioglycolate (MTG). Since gold nanoparticles themselves have low solubility, PEG can increase this parameter due to its hydrophilic nature. After the stabilization of nanoparticles, the reaction with hydrazine was performed to provide sites for DOX conjugation. As a result, DOX was covalently conjugated via a hydrazone bond between MTG moiety and a drug. The average diameter of the nanoparticles was measured to be 6 nm using Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM).

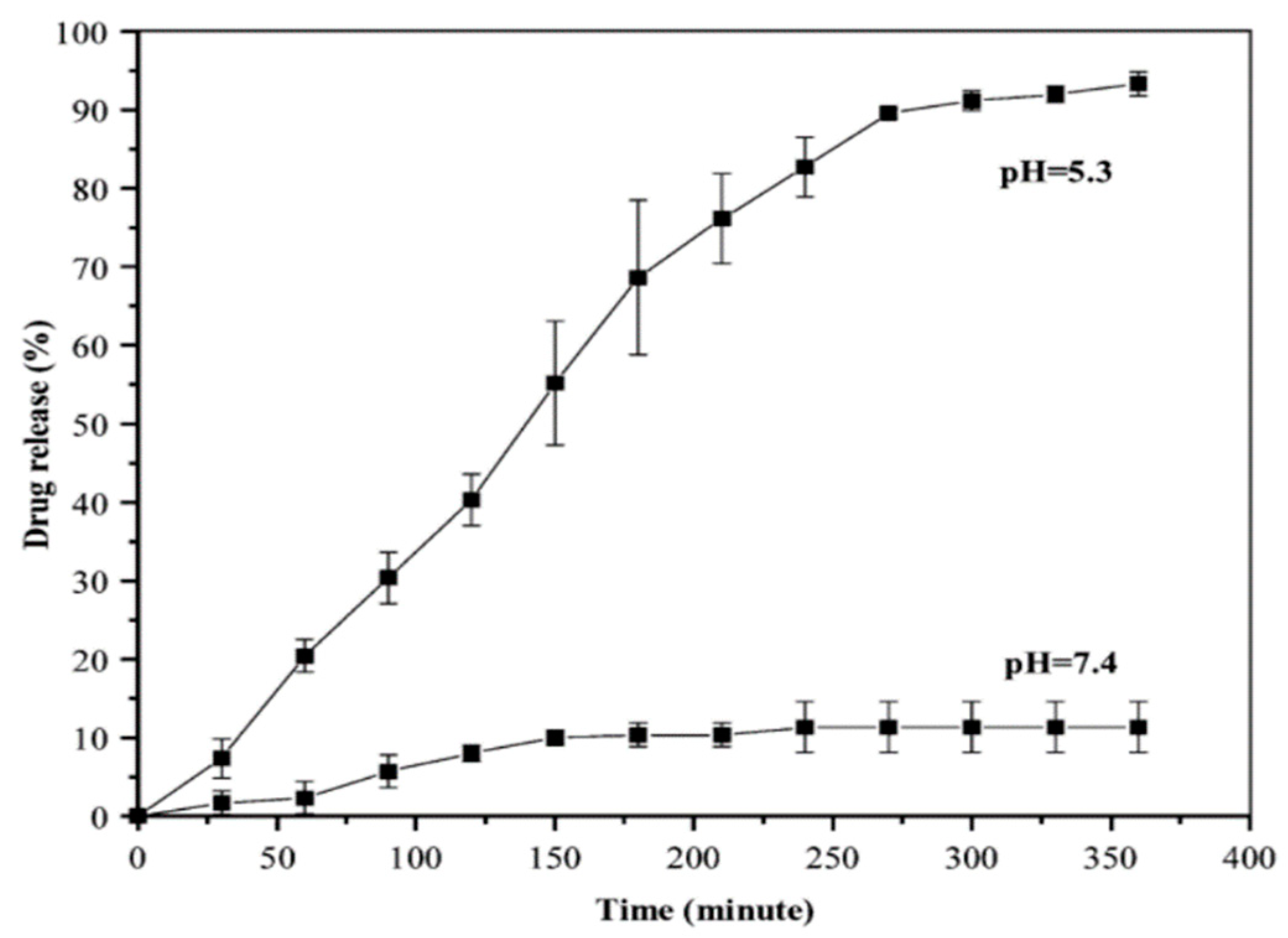

Cancer cells tend to have a lower pH due to the accumulation of lactic acid [

15]. Thus, after the internalization of the nanoparticle-drug conjugate via endocytosis, the drug can be released by the breakage of the hydrazone bond under the acidic environment of tumour cells. As such, the drug release rate was studied

in vivo using two different pH environments: 5.3 and 7.4 (tumour and healthy cells, respectively). At the pH of healthy cells, only 10% of the drug was released, while at pH 5.3 80% of the drug was released after a 5 h period (

Figure 4). The results show that DOX will be successfully released from the nanoparticles after entering the cancer cell and will not be released in physiological pH.

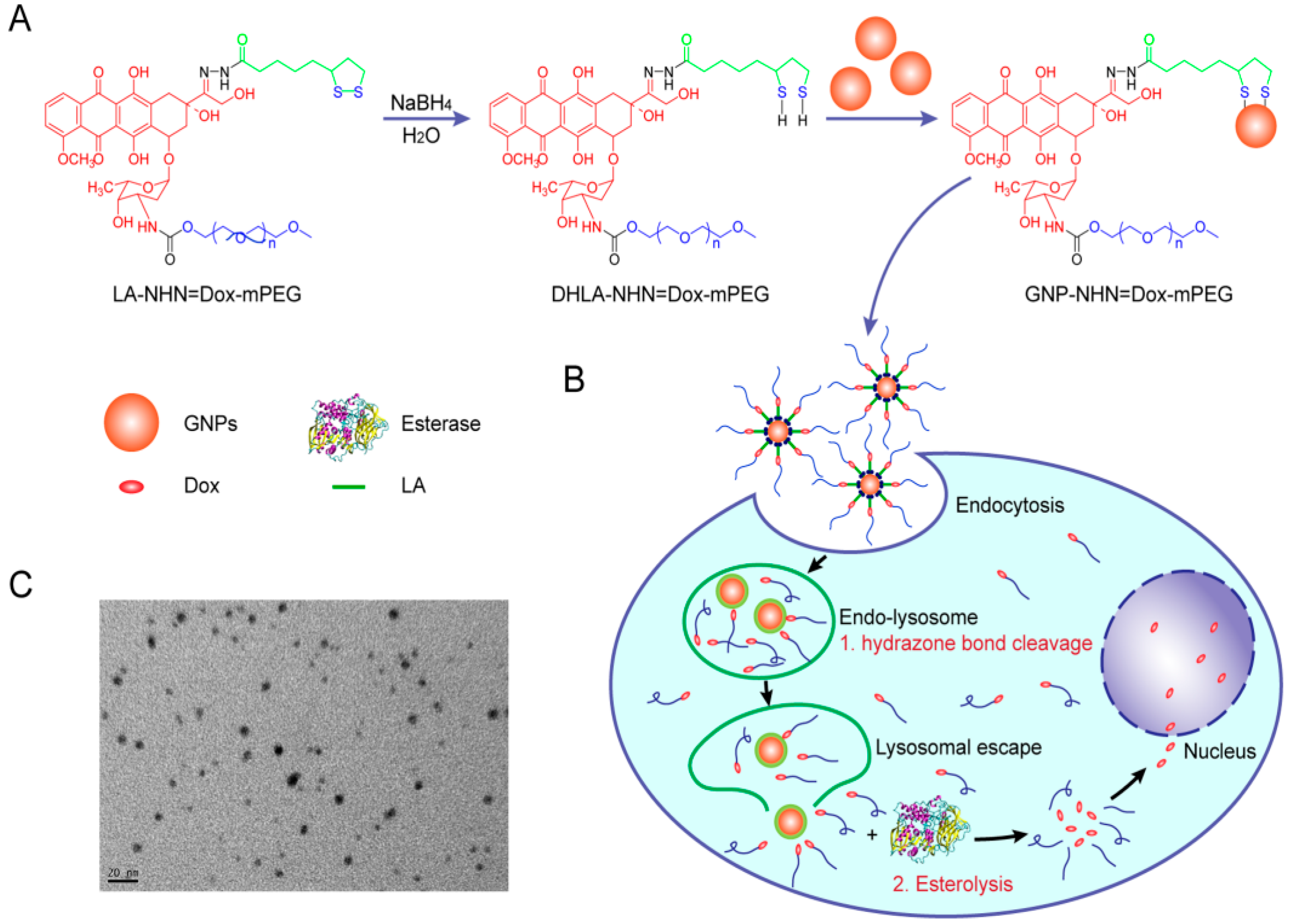

Doxorubicin itself can also be modified before conjugation to nanoparticles to improve the stability and solubility of the complex. DOX was modified with lipoic acid (LA) on the carbonyl group and polyethylene glycol (PEG) on the amino group [

16]. The drug was covalently conjugated to the lipoic acid via the formation of a hydrazone bond resulting in the formation of LA-NHN=DOX-mPEG (

Figure 5). The lipoic acid was then reduced to dihydro lipoate (DHLA) via a ring-opening reaction which resulted in DHLA-NHN=DOX-mPEG containing thiol groups. Gold nanoparticles were then conjugated by disulfide bonding. The NP-drug conjugate was shown to exhibit a small size (179.0 ± 7.5 nm) that is efficient in escaping the reticuloendothelial system. The coating with PEG increased the solubility of the conjugate: by 30 mg/mL compared to the solubility of doxorubicin hydrochloride (10 mg/mL). The drug loading capacity was determined to be 27.3%, which is higher than the values reported for non-covalent drug conjugation (10-15%).

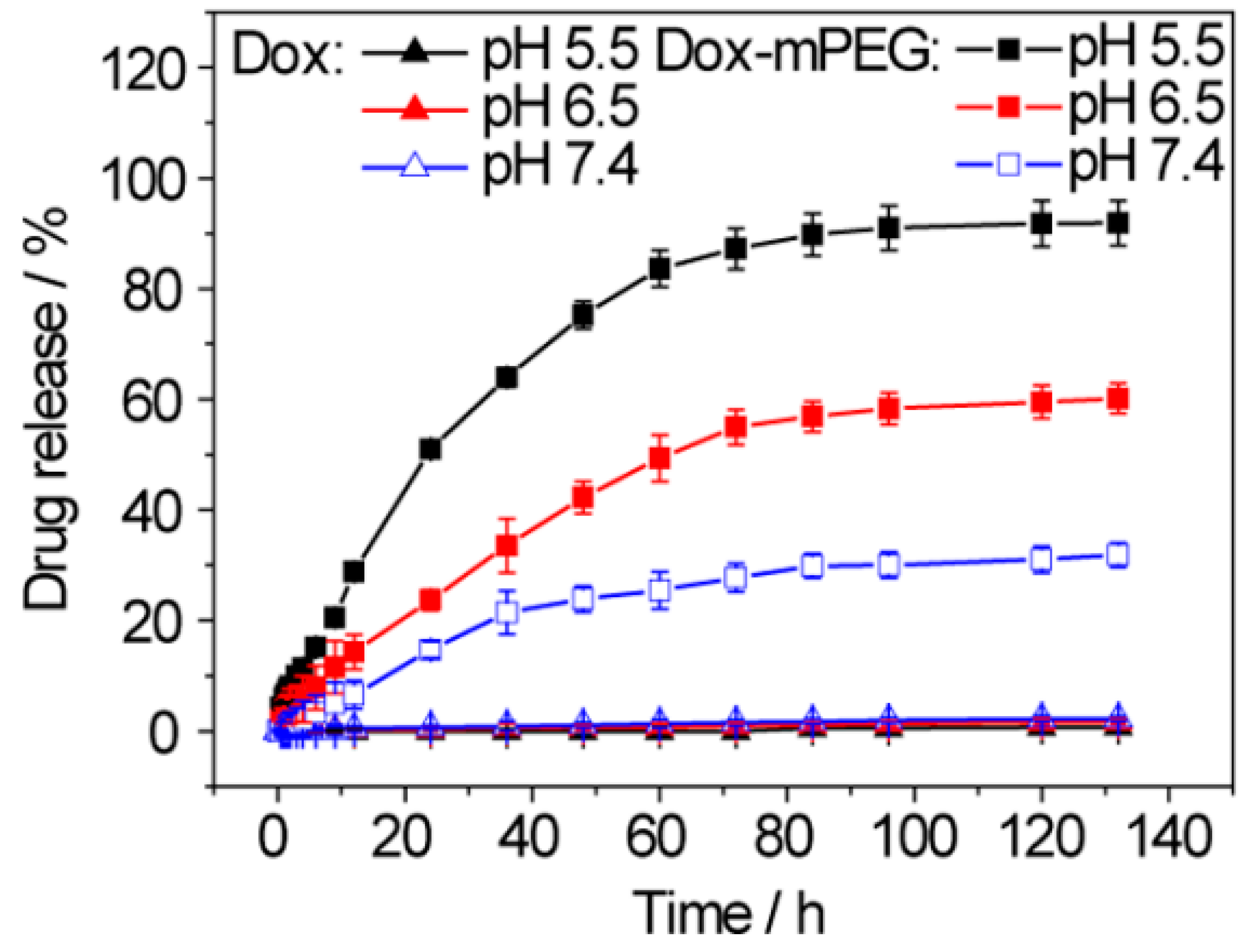

The drug release mechanism was based on the two-step bond breakage. First, the hydrazone bond was broken in the acidic lysosome environment releasing the DOX-mPEG. Then, high esterase concentration in tumour cells leads to the hydrolytic release of free DOX. At pH 5.5, 91.8% of DOX was released, while at pH 7.4 only 31.9% of the DOX was released (

Figure 6). The three-fold difference between the release in tumour and healthy cells indicates that the conjugate will be stable during circulation and rapidly released after entering the cancer environment.

Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (MIONs) are another frequently used type of metallic nanoparticles due to their superparamagnetic properties [

17]. Since they can be affected by magnetic fields, it is possible to guide the drug to the target. Moreover, MIONs are widely used to monitor real-time drug delivery using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). However, due to their high surface energy, they tend to agglomerate rapidly [

18]. In addition to this, they demonstrate high reactivity that usually results in a loss of magnetism [

19]. Coating nanoparticles with biomolecules is one of the possible solutions to the above-mentioned problems associated with MIONs. As such, doxorubicin-covalent conjugation to metallic nanoparticles can be an excellent drug delivery system as well as increase stability by lowering the oxidation rate of naked nanoparticles.

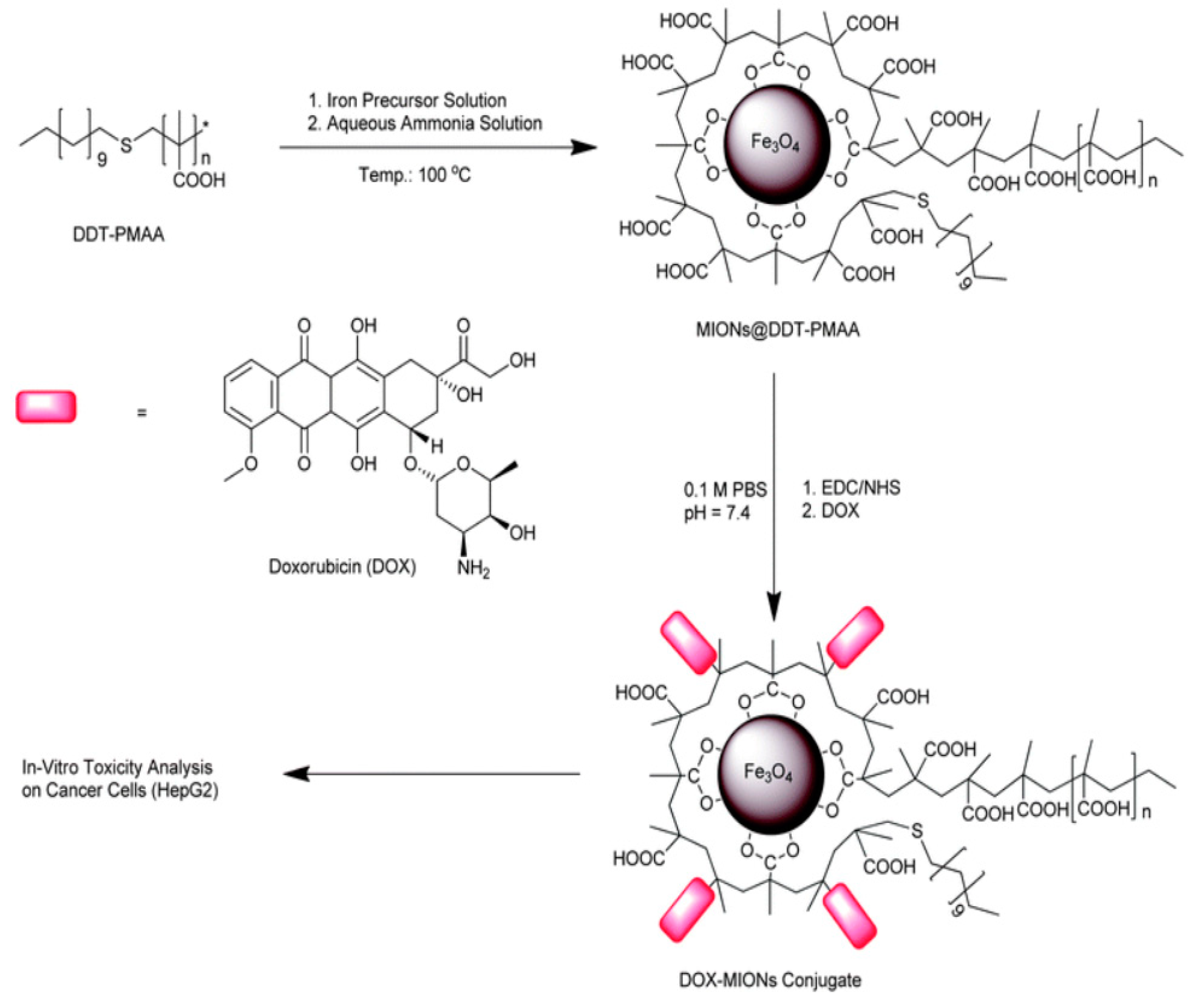

The formation of MIONs via a single-step synthesis method was reported by using thioether end-functionalized polymer ligand dodecanethiol–polymethacrylic acid (DDT–PMAA) [

20]. It was then reacted with an iron precursor that allowed the formation of ultra-small (4.6 ± 0.7 nm) magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles exhibiting a high number of -COOH groups at their surface (

Figure 7). DOX was then covalently conjugated via the formation of an amide bond between those carboxyl groups and amino groups of the drug. The resulting DOX-coated MIONs showed good stability compared to naked MIONs. The drug conjugation efficiency was determined to be 60%; it is higher compared to MIONs non-covalently/electrostatically bound to the magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles. This observation proves that covalent conjugation can allocate more drug capacity due to the stronger nature of covalent bonds.

Despite all the benefits provided by the conjugated complexes of metallic nanoparticles for DOX delivery, there are a few drawbacks of the proposed system, such as cost-effectiveness, toxicity response to inorganic components, and longevity of elimination from the body [

13].

3. Silica/Organosilica Nanoparticles

Silica and organosilica nanoparticles are considered to be relatively novel drug delivery systems. They tend to have excellent stability and low toxicity. As opposed to inorganic NPs, organosilica NPs contain an organic component that potentially could positively affect their degradation and toxicity profiles [

21]. The conjugation of doxorubicin to silica/organosilica NPs mainly happens via physical entrapping in the pores [

22]. However, since the electrostatic forces are weak, there is a high drug leakage. Covalent conjugation was used as an alternative since it is significantly stronger. As a result, premature drug release could be avoided. This type of conjugation arose only recently, therefore there is limited literature on doxorubicin covalent conjugation to organosilica/silica NPs

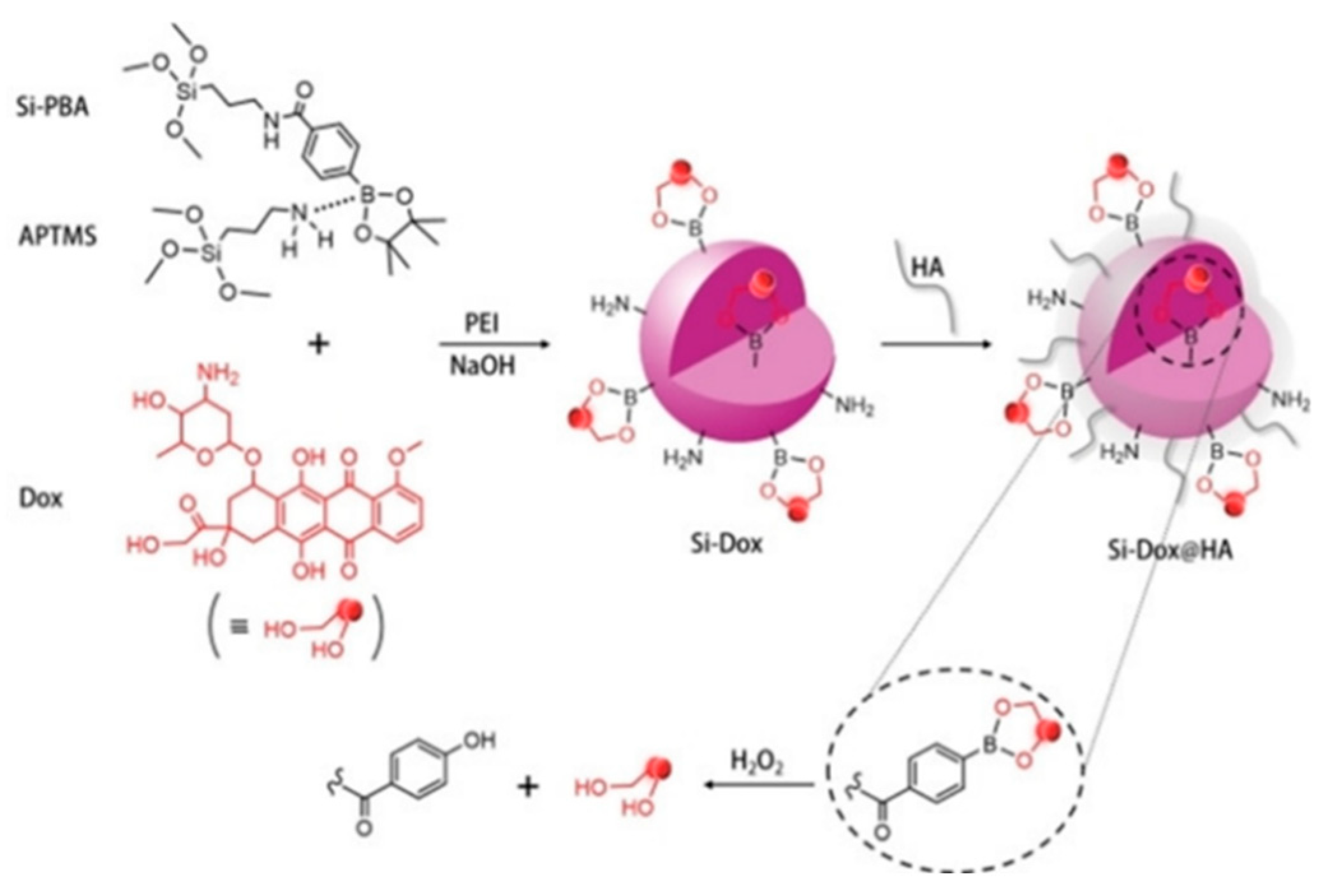

DOX was covalently bound to organosilica nanoparticles via phenylborate ester bonds (

Figure 8) [

23]. Phenylboronic acid (PBA) coupled with 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTMS) was used as a precursor for the synthesis of nanoparticles. DOX was conjugated to a phenylboronic moiety of NPs. However, the obtained conjugate was too large, allowing the immune system to easily detect and excrete it from the body. As such, polyethyleneimine (PEI) was introduced to the synthesis to allow size control.

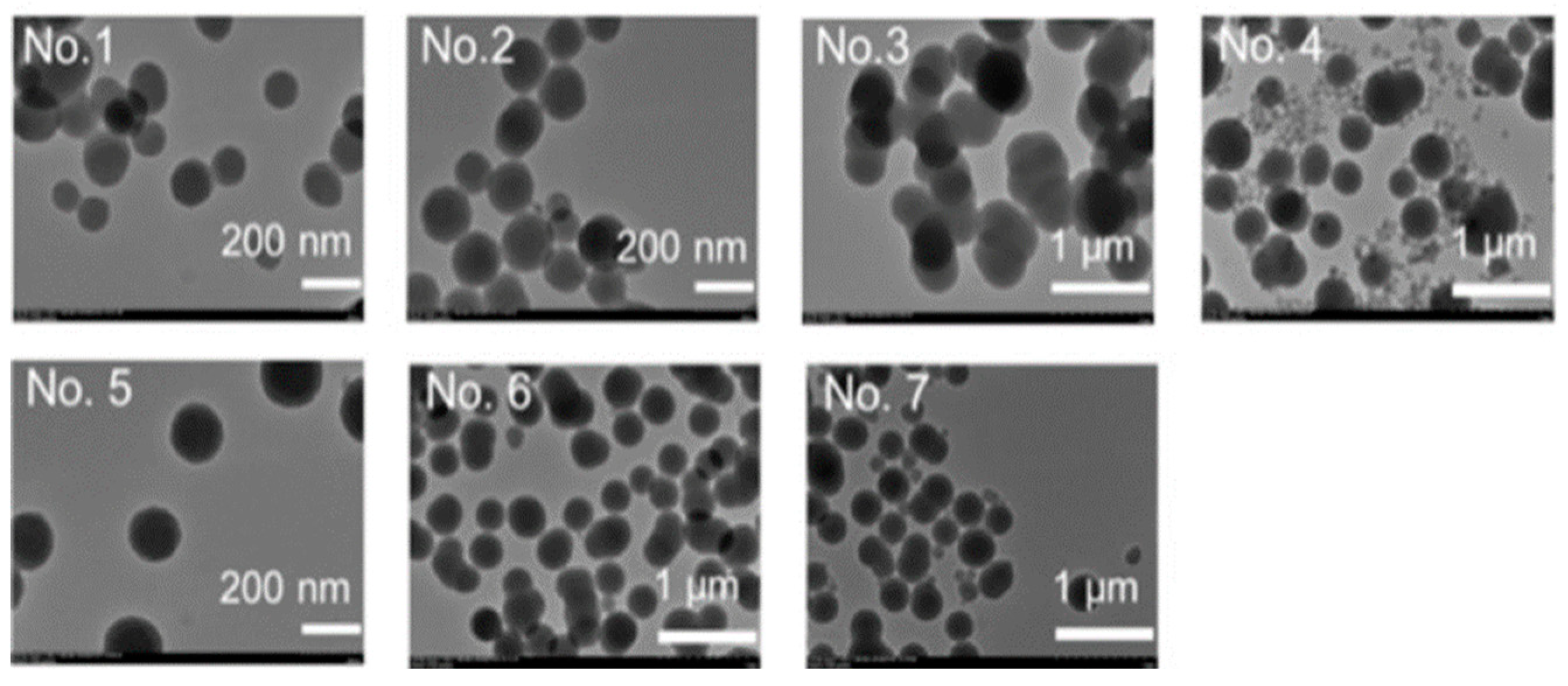

Several different concentrations of the reagents were tried to determine the most suitable reaction conditions (

Table 1).

A high concentration of APTMS resulted in the production of nanoparticles with large diameters, while a high concentration of PEI led to the synthesis of very dispersed NPs (

Figure 9). However, it also resulted in a low loading capacity. Still, the second condition was chosen as the optimal reaction condition. After the successful conjugation, the DOX-NPs conjugate was coated with hyaluronic acid (HA) to allow better targeting since HA has a high affinity to CD-44 glycoproteins that are usually overexpressed in cancer cells.

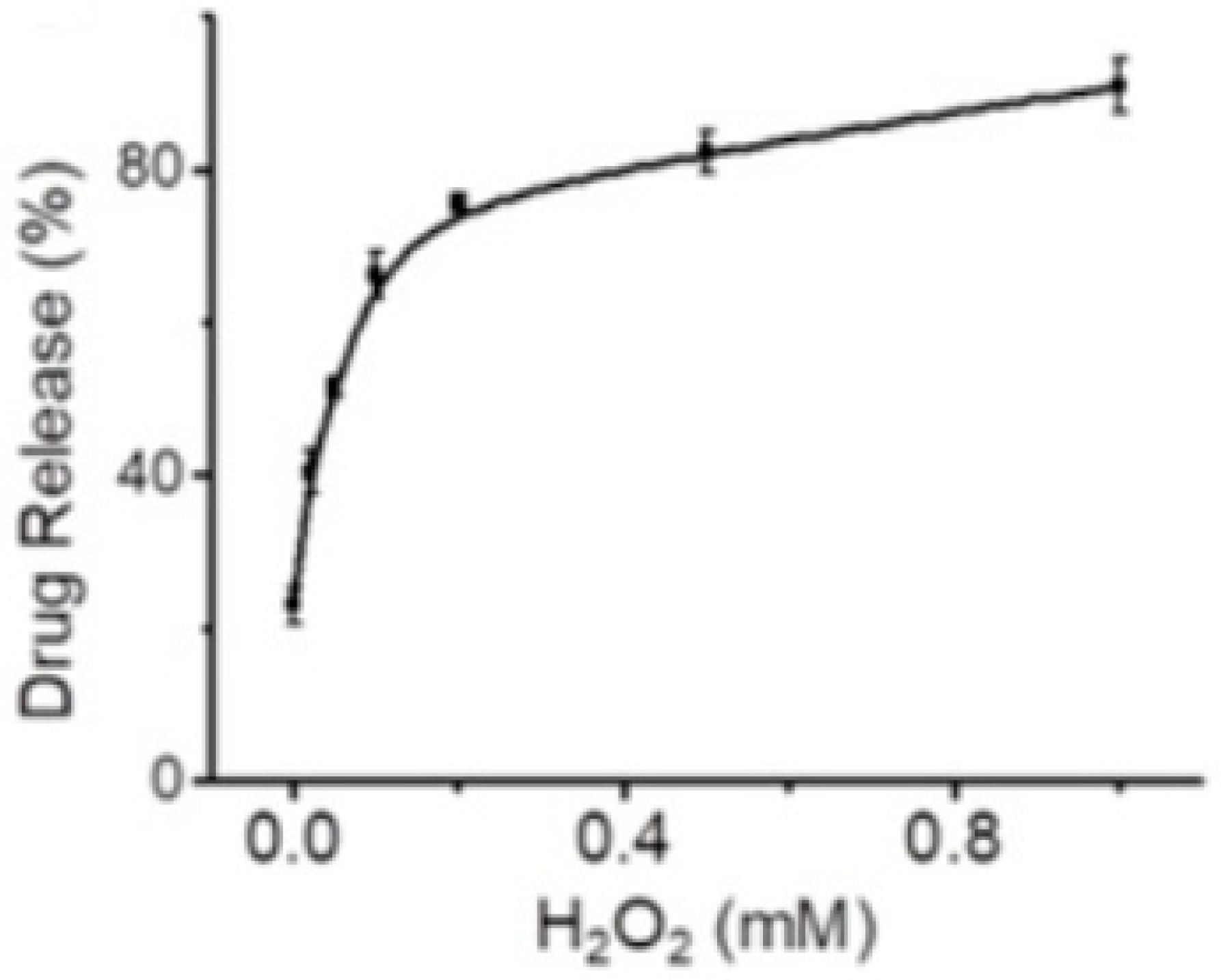

The drug release was studied in an H

2O

2-containing medium since cancer cells tend to have higher concentrations of hydrogen peroxide (up to 1 mM) compared to healthy cells. The phenylborate ester bond between doxorubicin and NP can be easily hydrolyzed by H

2O

2, resulting in successful drug release in the tumour environment. The release rate at 100 μM H

2O

2 and pH 6.5 (a cancer environment tends to be more acidic) was equal to 80% (

Figure 10).

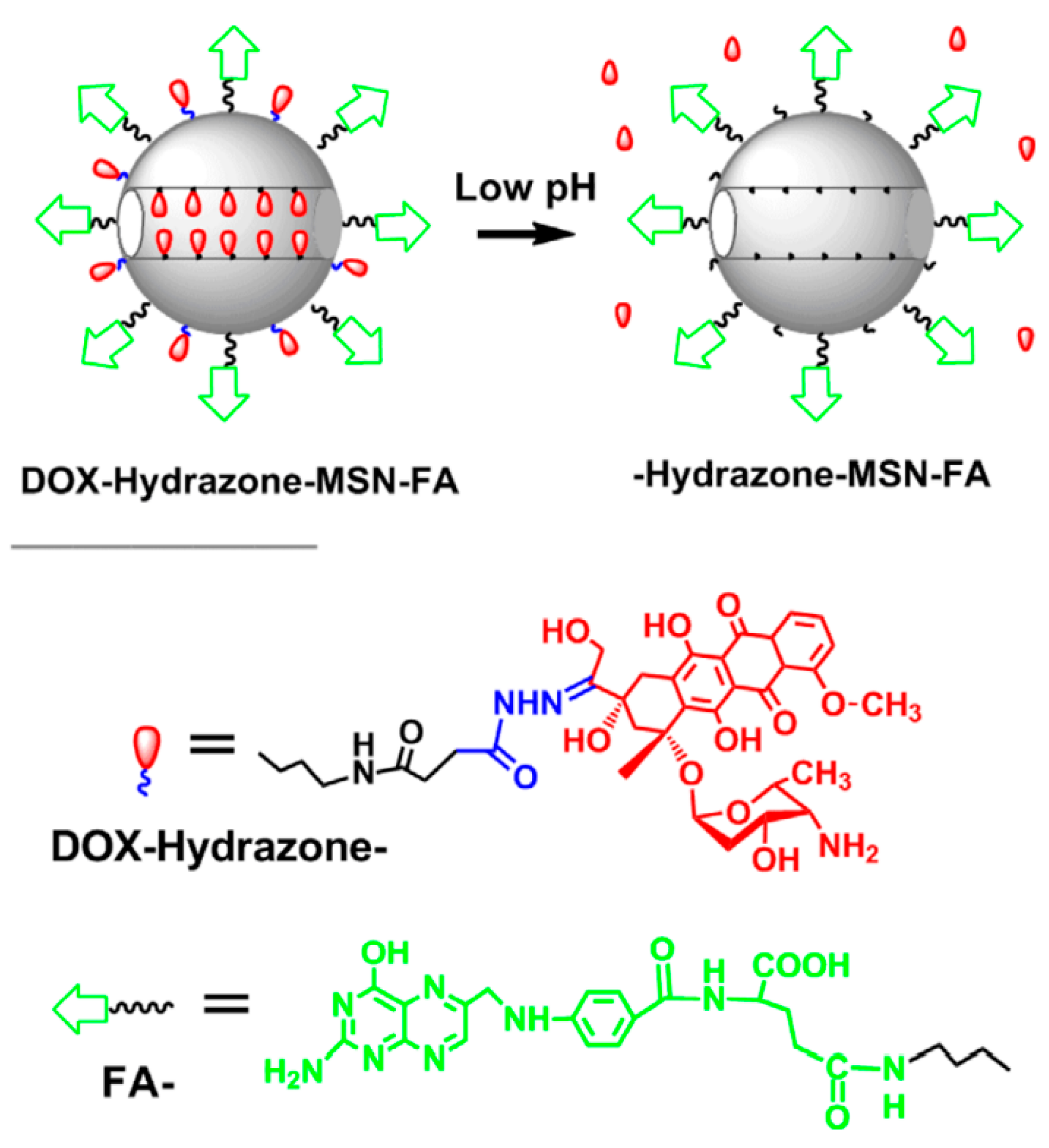

Mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) can also be used for the covalent conjugation of doxorubicin [

24]. DOX was conjugated to MSNs via the formation of hydrazone bonds (

Figure 11). The conjugate was then coated with folic acid (FA) to target folate receptors that are typically overexpressed in tumour cells. The conjugate was found to exhibit a small diameter of 180 nm. It is crucial to keep the size smaller than 300 nm since bigger particles can be easily detected by the immune system, leading to their faster clearance.

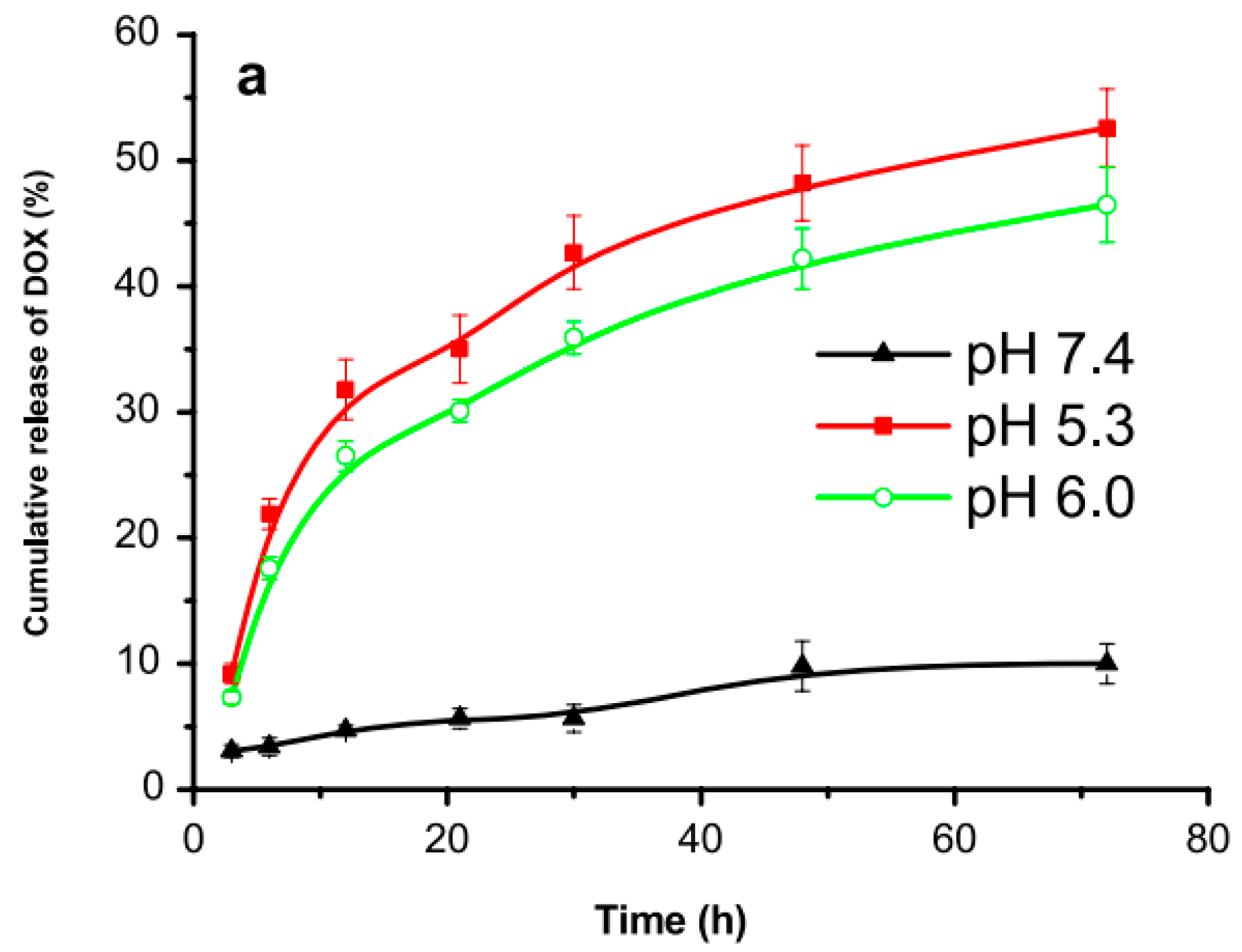

The DOX-MSNs conjugate can enter the cell via endocytosis where the hydrazone bone can be easily cleaved by the acidic environment. As such, the drug release rate was studied at different pH media: 5.3, 6.0, and 7.4. The results after 24 h (

Figure 12) showed 40%, 30%, and 5% release, respectively. The slow release of DOX at physiological pH indicated the higher stability of the nanoparticles during circulation which can significantly decrease the side effects.

4. Polymeric Nanoparticles

Polymeric nanoparticles are another candidate for drug delivery systems used for covalent conjugation of doxorubicin. They provide good stability and easy conjugation [

25].

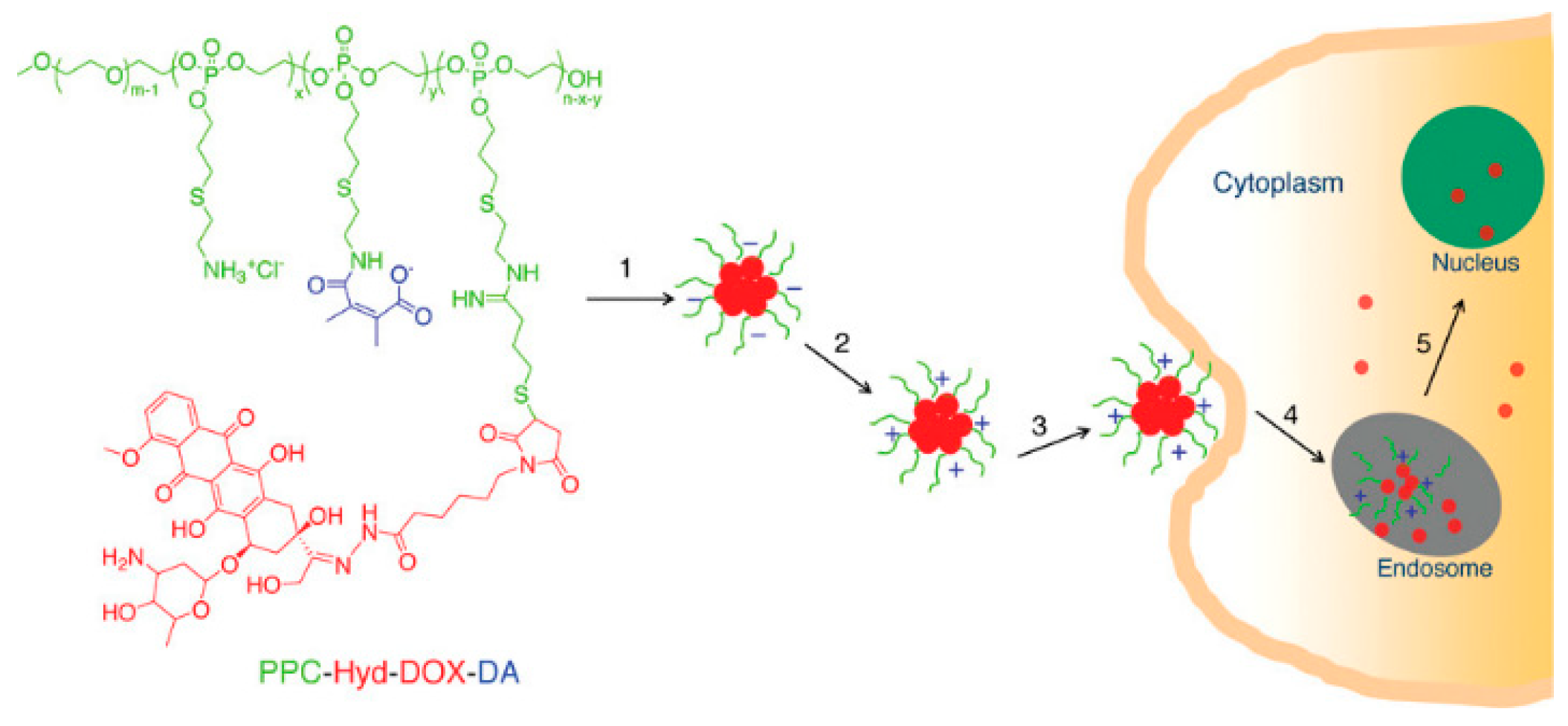

Polymeric nanoparticles were synthesized from cysteamine-modified polyallyl ethylene phosphate (PPC) [

26]. Doxorubicin was then conjugated via the formation of a pH-responsive hydrazone bond. Free amino groups were modified with 3-dimethylmaleic acid (DA) to obtain charge-conversional conjugate (

Figure 13). The resulting nanoparticles, PPC-Hyd-DOX-DA, self-assembled in the water due to the hydrophobic nature of DOX moiety. As a result, drug-NP conjugates with negative surface charge were formed. After entering the extracellular tumour environment, the amide bonds were broken, and the conjugate acquired a positive charge that allowed endocytosis through the negatively charged cell membrane.

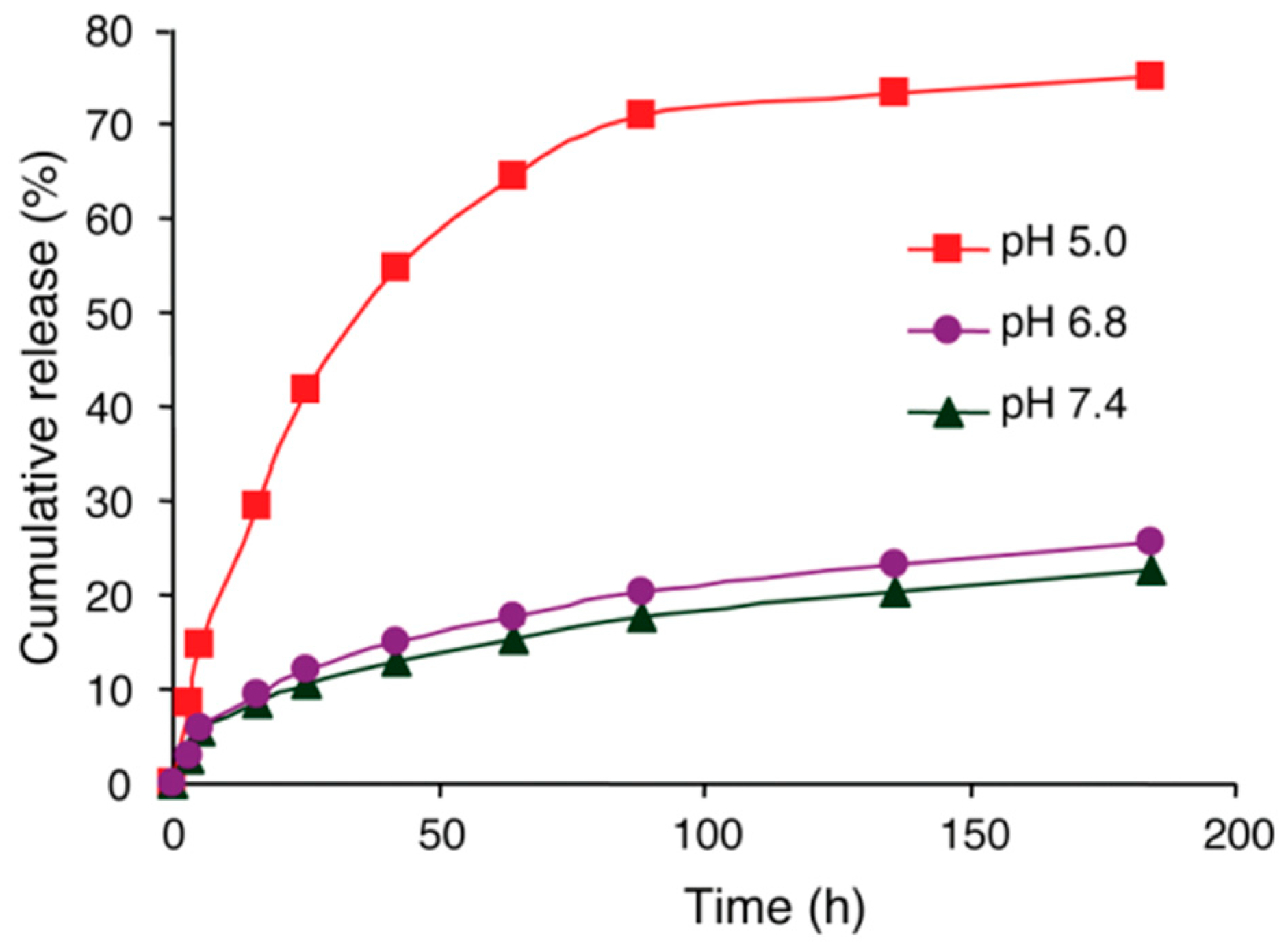

The

in vivo drug release was studied using two media with different pH levels: 5.0 and 7.4, cancer and healthy cells, respectively. At pH 7.4 only 22.6% of DOX was released, whereas at pH 5.0 the value reached approximately 75% (

Figure 14). Thus, the drug release profile shows that the hydrazone bonds attaching the drug to the nanoparticle are expected to be broken at the endosomal acidic pH of cancer cells. Moreover, it also shows that the conjugate is likely to be relatively stable during circulation before reaching the target cancer cells.

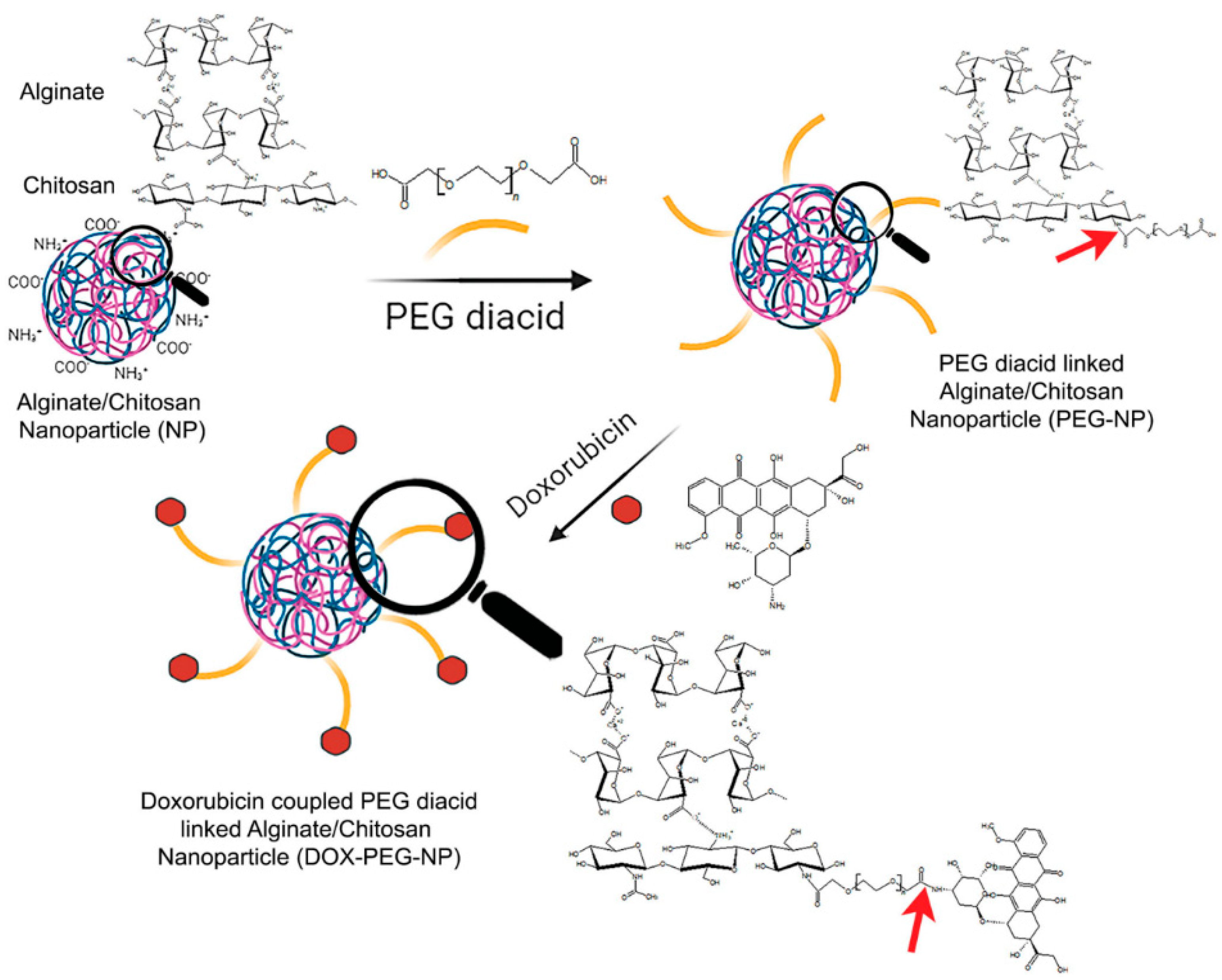

Polymeric nanoparticles can also be synthesized by conjugating alginate and chitosan which can be used in lung cancer treatment [

27]. The main role of chitosan is to stabilize the polymer and allow the synthesis of more dispersed and small nanoparticles. The size distribution was assessed using Dynamic Light Scattering and the average diameter was 60-65 nm, with PDI values of lower than 0.5. Particles of small size can easily enter the tumour cells via enhanced permeation and retention effect (EPR). To remove the steric hindrance of resulting nanoparticles, they were modified with PEG (

Figure 15). Finally, doxorubicin was conjugated via the formation of an amide bond between polyethylene glycol and the drug. The nanoparticles showed excellent drug conjugation efficiency of 49.1 ± 3.1%.

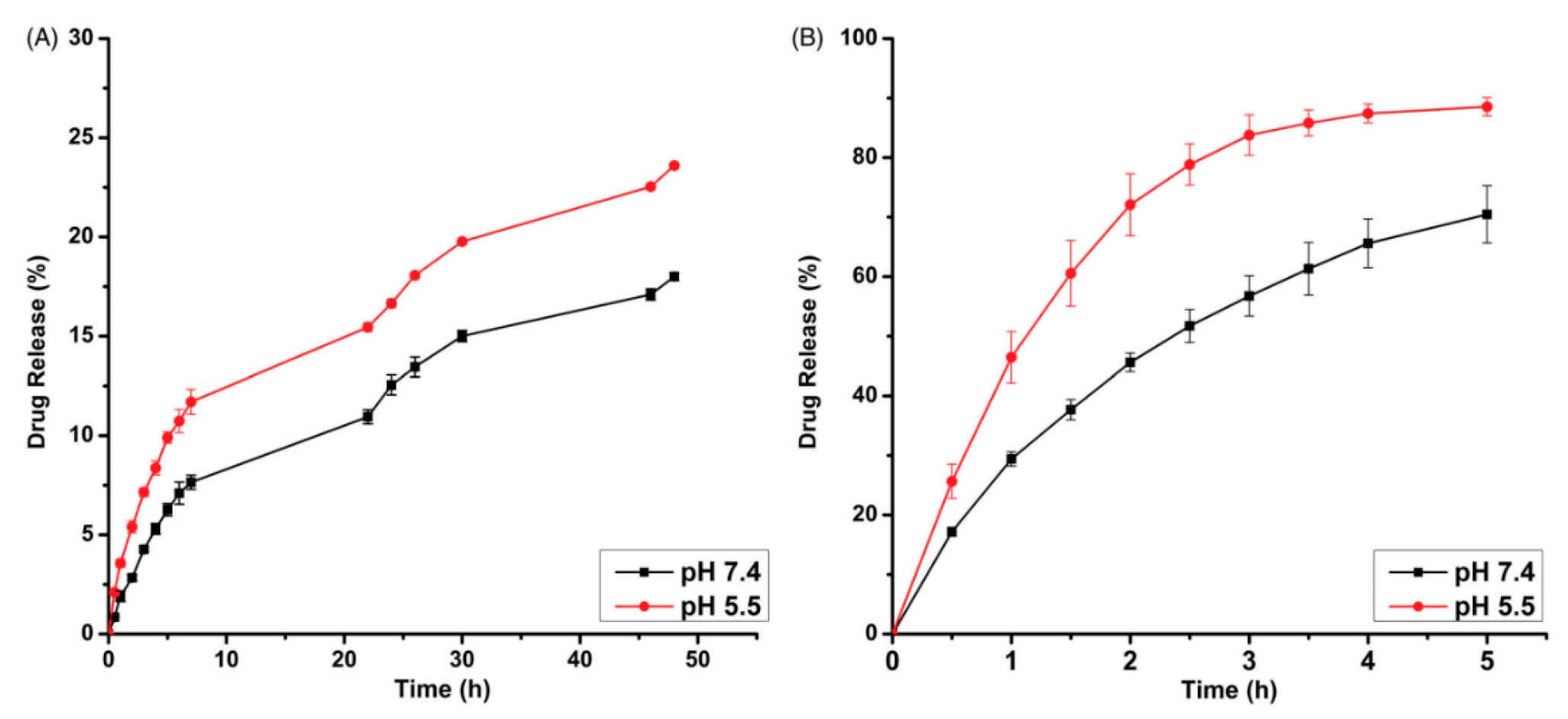

The DOX-NP drug release rate was studied at two different pH levels, 5.5 and 7.4. The results were also compared with the release rate of free doxorubicin (

Figure 16). It was shown that 70-85% of free doxorubicin was released in both healthy and cancer cells. These findings clearly indicated that doxorubicin cannot differentiate between healthy and cancerous cells. The high release rate in healthy cells results in serious side effects associated with chemotherapy. The DOX release from polymeric nanoparticles takes place via the breakage of an amide bond. At pH 5.5 the release reached 23.6%. In comparison, at a physiological pH of 7.4, the maximum release was 18%. The release rate is significantly lower compared to the release of free DOX, which indicates that polymeric nanoparticles can be used as drug delivery systems that can potentially decrease the negative side effects on healthy cells.

Despite the mentioned advantages of polymeric nanoparticles in drug delivery for cancer treatment, some serious drawbacks can limit their applicability. Difficulty in controlling their morphology is one of these; it greatly hinders the reproducibility of results [

28].

5. Conclusions

Covalent conjugation of doxorubicin to nanoparticles is a more efficient design of drug delivery systems than non-covalent conjugation. The latter cannot target delivery, while covalent conjugation results in the breakage of the bond between DOX and nanoparticle in response to different environmental stimuli, such as pH and hydrogen peroxide concentrations of tumour cells.

Moreover, covalent conjugation shows a significantly higher drug release percentage in a tumour environment compared to a healthy one. It proves that the drug will be preferentially released in the tissues affected by cancer due to environmental factors. Despite non-covalent conjugation is more prevalent due to its simplicity, covalent conjugation seems to be a more promising method in drug delivery due to its advantages.

Funding

This work has been funded by the Science Committee of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. AP13068353).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing does not apply to this article.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by funding from the Science Committee of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. AP13068353).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zaid, A. S; Aleissawy, A. E.; Yahia, I. S.; Yassien, M. A.; Hassouna, N. A.; Aboshanab, K. M. Streptomyces griseus KJ623766: A Natural Producer of Two Anthracycline Cytotoxic Metabolites β-and γ-Rhodomycinone. Molecules 2021, 26, 4009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivankar, S. An overview of doxorubicin formulations in cancer therapy. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2014, 10, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M.; Arabi, L.; Alibolandi, M. Doxorubicin-loaded composite nanogels for cancer treatment. J. Control. Release 2020, 328, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, K.; Zhang, J.; Honbo, N.; Karliner J., S. Doxorubicin Cardiomyopathy. Cardiology 2010, 115, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Shim, M. K.; Kim, W. J.; Choi, J.; Nam, G. H.; Kim, J.; Kim, K. Cancer-activated doxorubicin prodrug nanoparticles induce preferential immune response with minimal doxorubicin-related toxicity. Biomater. 2021, 272, 120791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, A.; Zare, M.; Thomas, V.; Kumar, T. S.; Ramakrishna, S. Nano-based drug delivery systems: Conventional drug delivery routes, recent developments and future prospects. Medicine Drug Discov. 2022, 100134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mun, E. A.; Zhaisanbayeva, B. A. Silica Nanoparticles for Biomedical Application: Challenges and Opportunities. EurAsian J. Appl. Biotechnol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.; Aftab, S.; Nisar, J.; Ashiq, M. N.; Iftikhar, F. J. Nanocarriers for targeted drug delivery. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2021, 62, 102426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhikara, B. S.; Rathi, B.; Parang, K. Critical evaluation of pharmaceutical rational design of Nano-Delivery systems for Doxorubicin in Cancer therapy. J. Mater. NanoSci. 2019, 6, 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- Sahu, S.; Sinha, N.; Bhutia, S. K.; Majhi, M.; Mohapatra, S. Luminescent magnetic hollow mesoporous silica nanotheranostics for camptothecin delivery and multimodal imaging. J. Mater. Chem. B 2014, 2, 3799–3808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upadhyay, K. K.; Bhatt, A. N.; Mishra, A. K.; Dwarakanath, B. S.; Jain, S.; Schatz, C.; Lecommandoux, S. The intracellular drug delivery and anti tumor activity of doxorubicin loaded poly (γ-benzyl l-glutamate)-b-hyaluronan polymersomes. Biomater. 2010, 31, 2882–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, F.; Engbers, G. H.; Feijen, J. Biodegradable polymersomes as a basis for artificial cells: encapsulation, release and targeting. J. Control. Release 2005, 101, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrakala, V.; Aruna, V.; Angajala, G. Review on metal nanoparticles as nanocarriers: Current challenges and perspectives in drug delivery systems. Emerg. Mater. 2022, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, S.; Grailer, J. J.; Pilla, S.; Steeber, D. A.; Gong, S. Doxorubicin conjugated gold nanoparticles as water-soluble and pH-responsive anticancer drug nanocarriers. J. Mater. Chem. 2009, 19, 7879–7884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. X.; Choi, S. Y.; Niu, X.; Kang, N.; Xue, H.; Killam, J.; Wang, Y. Lactic acid and an acidic tumor microenvironment suppress anticancer immunity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, T.; Liang, J.-J.; Chen, H.; Geng, D.-D.; Jiao, L.; Yang, J.-Y.; Ding, Y. Performance of Doxorubicin-Conjugated Gold Nanoparticles: Regulation of Drug Location. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 8569–8580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; He, Q.; Jiang, C. Magnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles: Synthesis and Surface Functionalization Strategies. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2008, 3, 397–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Ji, H.; Yu, P.; Niu, J.; Farooq, M.; Akram, M.; Niu, X. Surface Modification of Magnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. Nanomater. 2018, 8, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangijzegem, T.; Stanicki, D.; Laurent, S. Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for drug delivery: applications and characteristics. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2019, 16, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majeed, M. I.; Lu, Q.; Yan, W.; Li, Z.; Hussain, I.; Tahir, M. N.; Tan, B. Highly water-soluble magnetic iron oxide (Fe3O4) nanoparticles for drug delivery: enhanced in vitro therapeutic efficacy of doxorubicin and MION conjugates. J. Mater. Chem. B 2013, 1, 2874–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, R. S.; Rodrigues, C. F.; Moreira, A. F.; Correia, I. J. Overview of stimuli-responsive mesoporous organosilica nanocarriers for drug delivery. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 155, 104742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahiri, M.; Falsafi, M.; Lamei, K.; Abnous, K.; Taghdisi, S. M.; Ramezani, M.; Alibolandi, M. Targeted biomimetic hollow mesoporous organosilica nanoparticles for delivery of doxorubicin to colon adenocarcinoma: In vitro and in vivo evaluation. Micropor. Mesopor. Mat. 2022, 335, 111841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Shi, W.; Li, H.; Li, X.; Ma, H. H2O2-Responsive Organosilica-Doxorubicin Nanoparticles for Targeted Imaging and Killing of Cancer Cells Based on a Synthesized Silane-Borate Precursor. ChemMedChem 2019, 14, 1079–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Fang, G.; Wang, X.; Zeng, F.; Xiang, Y.; Wu, S. Targeted anticancer prodrug with mesoporous silica nanoparticles as vehicles. Nanotechnol. 2011, 22, 455102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begines, B.; Ortiz, T.; Pérez-Aranda, M.; Martínez, G.; Merinero, M.; Argüelles-Arias, F.; Alcudia, A. Polymeric nanoparticles for drug delivery: Recent developments and future prospects. Nanomater. 2020, 10, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J. Z.; Du, X. J.; Mao, C. Q.; Wang, J. Tailor-made dual pH-sensitive polymer–doxorubicin nanoparticles for efficient anticancer drug delivery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 17560–17563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ak, G. Covalently coupling doxorubicin to polymeric nanoparticles as potential inhaler therapy: In vitro studies. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2021, 26, 890–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd Ellah, N. H.; Abouelmagd, S. A. Surface functionalization of polymeric nanoparticles for tumor drug delivery: approaches and challenges. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2017, 14, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).