2.1. TH301-Induced Reduction of Cell Viability And Growth Of Pancreatic Cancer Cells In A Mutational Signature-Dependent Fashion

To demonstrate that circadian clock proteins can be, indeed, modulated in PDAC, we, first, analyzed the mutational frequencies of core circadian clock genes compared to key PDAC mutations in a cohort of 185 PDAC patients (

Suppl. Figure S1). This analysis highlighted the low probability of mutations in core clock genes, thus indicating that circadian clock functionality can be effectively targeted with specific modulators in PDAC settings. Hence, to explore the effects of TH301, a bona fide CRY2 stabilizer, on PDAC “modelled” pathology, we, herein, examined the human pancreatic cancer cell lines AsPC-1, BxPC-3 and PANC-1, with each one of them being characterized by a distinct mutational signature detailed in

Table S2 (

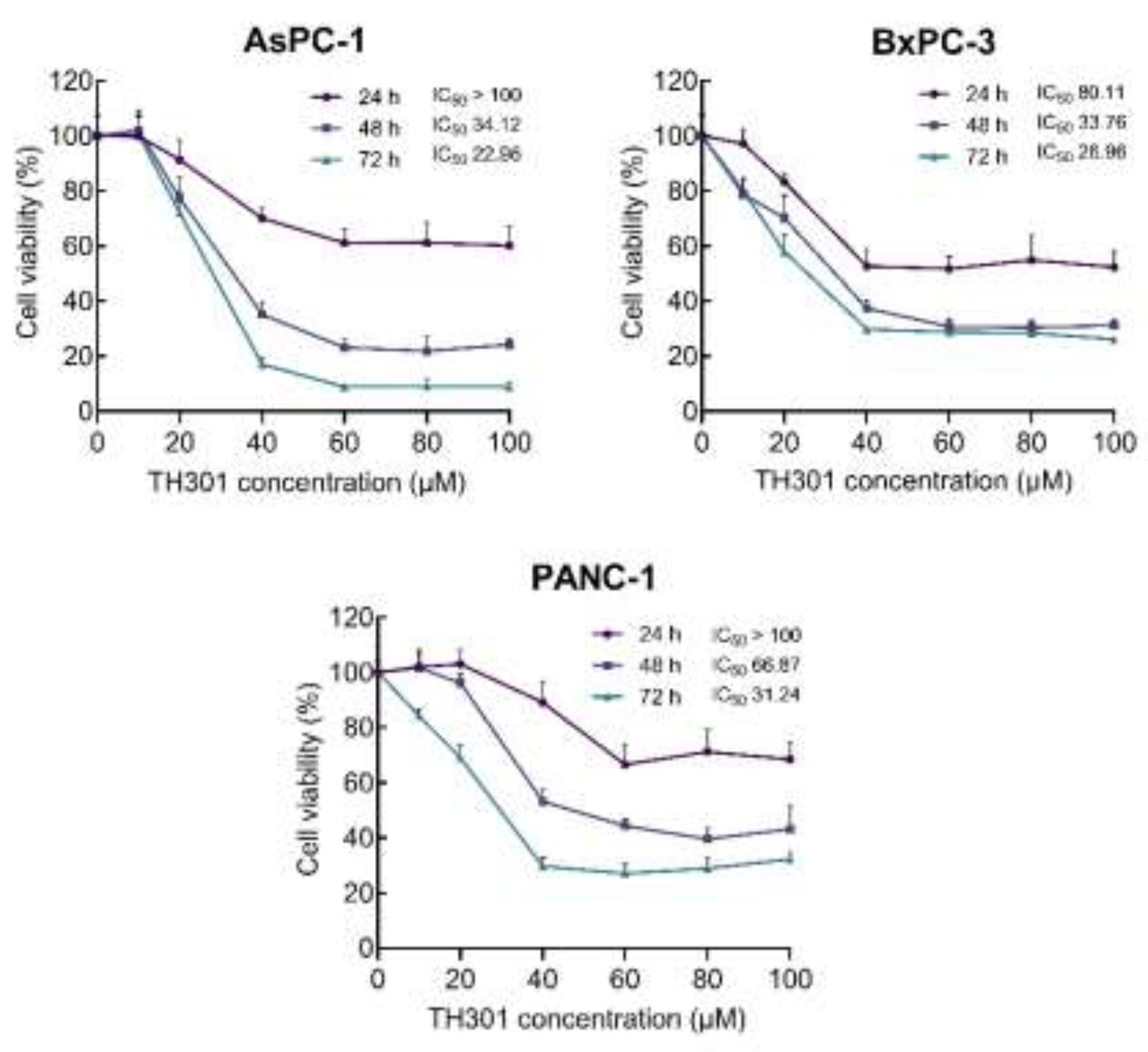

https://depmap.org). To determine the pathogenic responses of TH301 regarding cell viability and growth, the 3 PDAC cell lines were treated with increasing concentrations (0 - 100 μΜ) of TH301, for 24, 48, and 72 h. Cell survival was assessed and quantified by MTT assays. As shown in

Figure 1, TH301 administration resulted in a dose- and time-dependent significant decrease in the viability of all 3 cell lines, herein, examined. Both AsPC-1 and BxPC-3 cell lines presented a notable reduction in cell viability after 48 h of treatment with 40 μM TH301. In contrast, PANC-1 cells showed comparatively lower sensitivity, requiring 72 h, or 60 μM, to achieve a similar decrease rate of cell viability (~60% reduction). Most importantly, AsPC-1 cells were presented with severe pathologies after their exposure to TH301 for 72 h, having the observed viabilities almost eliminated at the 60, 80 and 100 μM of TH301 concentration (

Figure 1).

These results prove that TH301 can cause strong cytotoxic effects in human pancreatic cancer cells, following dose-, time- and cell type-dependent patterns. To the same direction, we, next, performed MTT assays to evaluate and quantify the pathogenic effects of KL001, a CRY1/2 stabilizer [

23,

24], and KS15, a CRY1/2 inhibitor [

25,

26], on AsPC-1, BxPC-3 and PANC-1 cell viabilities. Treatment with KL001 was less effective than TH301 in reducing cell viability, whereas KS15 showed absence of significant reduction in cell viabilities (

Suppl. Figure S2). However, AsPC-1 cells were characterized by a prominent decline in their viability and growth at the highest dose (e.g., 100 μM) and longest time (e.g., 72 h) of each agent (e.g., KL001, or KS15) administration. Taken together, the CRY stabilizer, TH301, demonstrates a superior efficacy in reducing (human) pancreatic cancer cell viability and growth, compared to other CRY modulators, herein, tested (KL001 and KS15).

Figure 1.

TH301 reduces (human) pancreatic cancer cell viability in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Cell viability (%) graphs of AsPC-1, BxPC-3 and PANC-1 cells after treatment with increasing concentrations (0, 20, 40, 60, 80 and 100 μM) of TH301, for 24, 48 and 72 h (post-administration). Data from 6 replicates are presented as Mean ± SD values. IC50 values were measured through employment of a non-linear regression model.

Figure 1.

TH301 reduces (human) pancreatic cancer cell viability in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Cell viability (%) graphs of AsPC-1, BxPC-3 and PANC-1 cells after treatment with increasing concentrations (0, 20, 40, 60, 80 and 100 μM) of TH301, for 24, 48 and 72 h (post-administration). Data from 6 replicates are presented as Mean ± SD values. IC50 values were measured through employment of a non-linear regression model.

2.2. TH301 Causes Cell Cycle Arrest at the G1-Phase and Alters Protein Expression Profiles Of Critical Regulators In Pancreatic Cancer Cells: Mutational Load-Dependent Responses

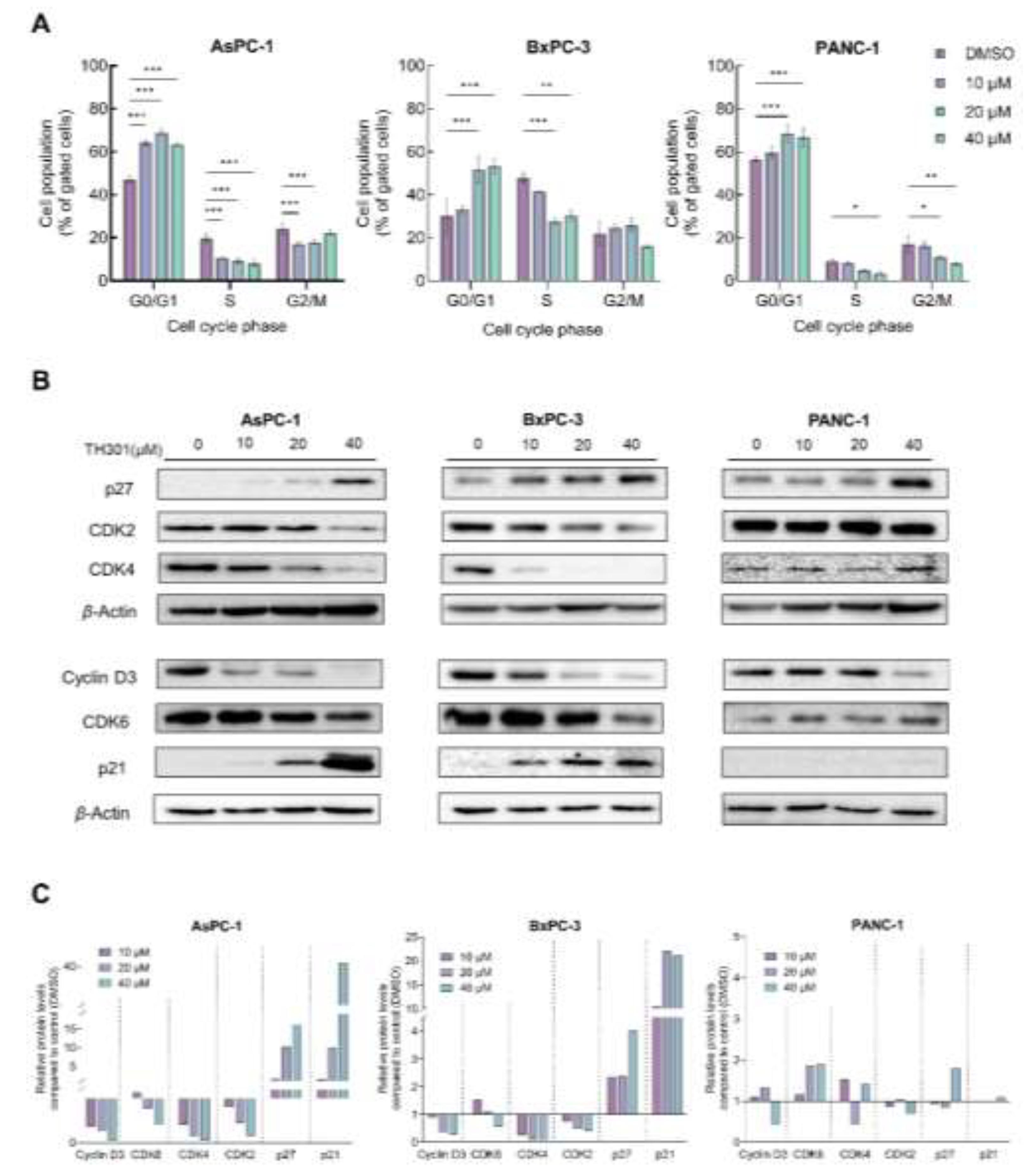

To investigate the underlying mechanism(s) of TH301-induced cell growth inhibition and survival compromise of PDAC cells, we, first, analyzed cell cycle phases after incubation of the cells with low to moderate TH301 doses (0 - 40 μΜ), for 24 h. As presented in Figure 2A, TH301 caused a dose-dependent arrest of cells at the G1-phase of the cell cycle. The increase in proportion of cells at the G1-phase was accompanied by a corresponding decrease in the proportion of cells at the S-phase. To independently validate the results obtained from Flow Cytometry (FACS) analysis, we, next, examined the expression levels of proteins that critically control cell cycle progression, with major determinants being the Cyclin D3, CDK6 (kinase), CDK4 (kinase), CDK2 (kinase), and the CDK inhibitors p21WAF1/CIP1 (p21) and p27KIP1 (p27). After 24 h incubation with TH301, protein levels of cell cycle activators (e.g., Cyclin D3, CDK2, CDK4 and CDK6) decreased, whereas expression levels of CDK inhibitors (p21 and p27) increased significantly, in a dose-dependent manner for all 3 cell lines, with the exception of p21 protein in PANC-1 cells, which remained undetected (Figs. 2B and 2C). These findings strongly suggest that TH301 can induce G1-arrest by severely altering the expression patterns of cell cycle regulatory proteins (e.g., p21 induction in AsPC-1 cells {40 μM TH301}; Figs. 2B and 2C) in all 3 pancreatic cancer cell lines, howbeit following mutational signature-specific profiles. In addition to cell cycle regulators, we also investigated the expression of genes coding for the major stemness factors SOX2, NANOG and OCT4. Expression of stemness genes, particularly NANOG, was significantly reduced after pancreatic cancer cell exposure to TH301 (40 μM; 24 h) (Suppl. Figure S3). Altogether, in a pancreatic cancer cell environment, TH301 is able to induce cell cycle arrest at the G1-phase, and, simultaneously, attenuate stemness network activity, via its transcription factor-program downregulation, thus highlighting TH301 potential and promise to act as an anti-proliferative and anti-survival, novel, agent, for pancreatic cancer management and therapy.

Figure 2.

TH301 induces cell cycle arrest at the G1-phase and causes major expression alterations in cell cycle control proteins. A. Flow Cytometry (FACS) analysis of PI-stained PDAC cells, after treatment with increasing concentrations (0, 10, 20 and 40 μM) of TH301, for 24 h (post-administration). Data from 3 replicates (N = 3) are presented as Mean ± SD values. Statistical significance was defined with One-way ANOVA, and comparisons were being made in between control (0.1% DMSO) and (TH301) treated cells (% of control). Asterisks indicate comparisons in between control and treated cells, at significance levels of 0.05 and below (*: < 0.05; **: < 0.01; ***: < 0.001). B. Western blotting-mediated expression profiling of main G1-phase-specific cell cycle regulators (Cyclin D3, CDK6, CDK4, CDK2, p21 and p27), after treatment of PDAC cells with increasing concentrations (0, 10, 20 and 40 μM) of TH301, for 24 h (post-administration). β-Actin was used as loading control (reference) protein. C. Quantification of protein expression, as it is being normalized to β-Actin (protein of reference), of G1-specific, cell cycle-phase proteins (Cyclin D3, CDK6, CDK4, CDK2, p21 and p27), of (human) pancreatic cancer cells, as compared to control cells (control cell values were set to “1").

Figure 2.

TH301 induces cell cycle arrest at the G1-phase and causes major expression alterations in cell cycle control proteins. A. Flow Cytometry (FACS) analysis of PI-stained PDAC cells, after treatment with increasing concentrations (0, 10, 20 and 40 μM) of TH301, for 24 h (post-administration). Data from 3 replicates (N = 3) are presented as Mean ± SD values. Statistical significance was defined with One-way ANOVA, and comparisons were being made in between control (0.1% DMSO) and (TH301) treated cells (% of control). Asterisks indicate comparisons in between control and treated cells, at significance levels of 0.05 and below (*: < 0.05; **: < 0.01; ***: < 0.001). B. Western blotting-mediated expression profiling of main G1-phase-specific cell cycle regulators (Cyclin D3, CDK6, CDK4, CDK2, p21 and p27), after treatment of PDAC cells with increasing concentrations (0, 10, 20 and 40 μM) of TH301, for 24 h (post-administration). β-Actin was used as loading control (reference) protein. C. Quantification of protein expression, as it is being normalized to β-Actin (protein of reference), of G1-specific, cell cycle-phase proteins (Cyclin D3, CDK6, CDK4, CDK2, p21 and p27), of (human) pancreatic cancer cells, as compared to control cells (control cell values were set to “1").

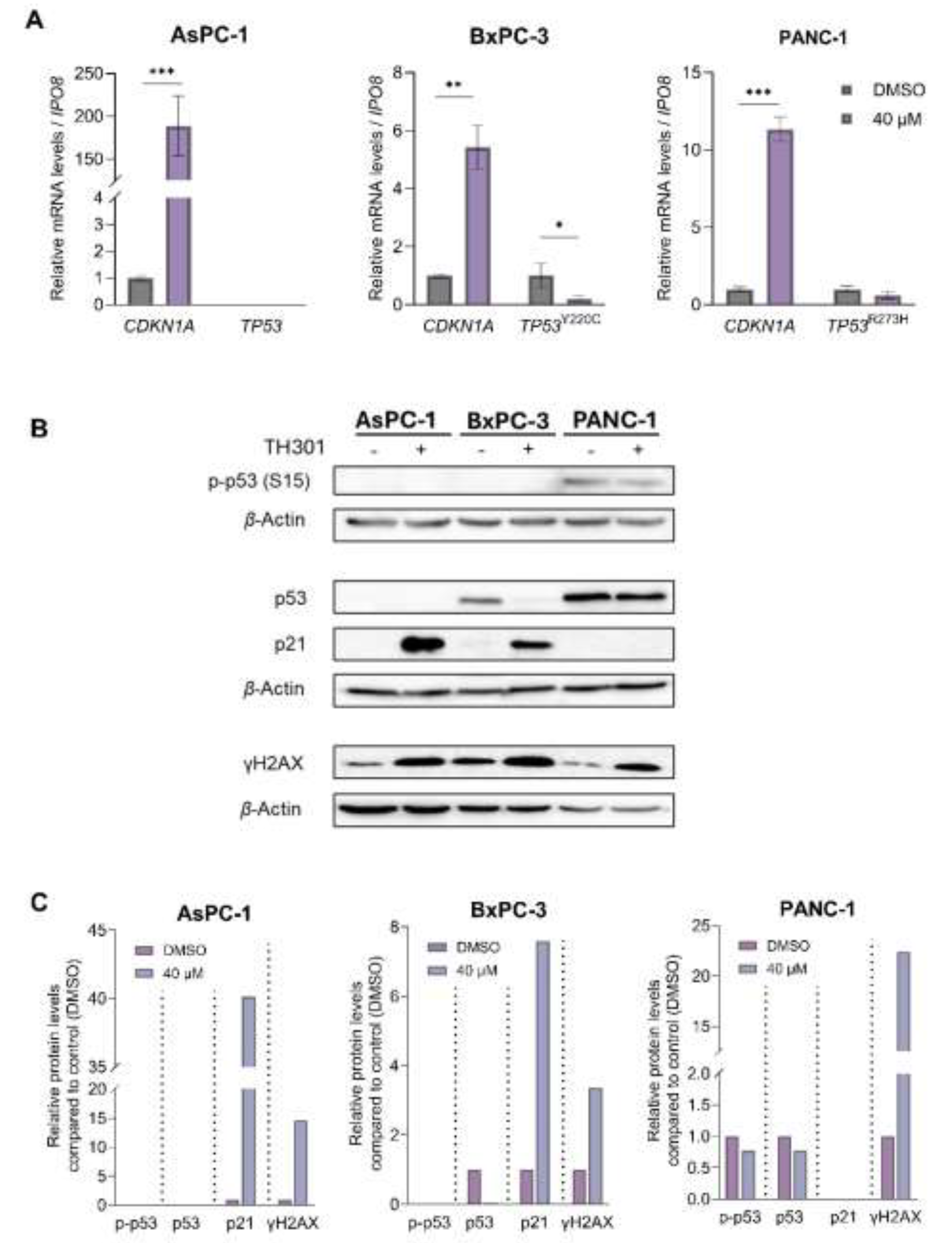

2.3. TH301 Causes a Strong p53-Independent Induction of the CDKN1A/p21 Cell Cycle Inhibitor, in Pancreatic Cancer Cell Environments, Following Mutational Load-Specific Patterns

Given that p53 induces

CDKN1A gene transcription [

32], we, next, reasoned to explore whether TH301 impacts the expression of

TP53/p53 levels in BxPC-3 and PANC-1 cells, considering that the BxPC-3 and PANC-1 cell lines carry point mutations in the

TP53 locus (

Table S2), whereas the AsPC-1 cells completely lack both p53 protein expression and

TP53 gene activity (

Figure 3). As depicted in

Figure 3A, PDAC cell exposure to TH301, for 24 h, significantly increased

CDKN1A levels (> 150x) and reduced mutant

TP53 (

TP53Y220C) contents in BxPC-3 cells, without, however, affecting mutant

TP53 (

TP53R273H) levels in the PANC-1 cellular setting. Importantly, we also examined p53 protein levels and its phosphorylation status at the critical amino-acid residue of Serine 15 (Ser

15), alongside with the induction of p21 protein, following a 24 h of TH301 treatment (40 μM). As shown in

Figures 3B and

3C, the remarkable induction of p21 protein, in response to TH301 administration, proved to operate independently of both total and phosphorylated (p-Ser

15) p53 protein forms in BxPC-3. PANC-1 cells showed transcriptional-level induction only (

Figure 3A). Furthermore, in AsPC-1 cells, p53 (both total and p-Ser

15) forms are missing, despite the strong transcriptional increase in

CDKN1A gene activity, after TH301 treatment, thereby indicating the p53-independent proficiency of TH301 to strikingly upregulate

CDKN1A/p21 levels in PDAC environments of diverse mutational loads.

Our findings strongly suggest that TH301 significantly induces

CDKN1A gene expression, with p21 induction occurring independently of the p53 phosphorylation/activation status, in (human) pancreatic cancer cells. We, next, evaluated the potential genotoxic effects of TH301, by investigating the phosphorylation levels of Histone H2AX, a well-established marker of DNA damage [

33,

34,

35]. As shown in

Figures 3B and

3C, a notable increase in gamma-H2AX (γH2AX) levels was observed across all 3 cell lines, following a 24 h exposure to TH301, thereby indicating its (TH301) capacity to exert genotoxic effects in pancreatic cancer cells, in p53-independent manners.

Figure 3.

TH301-induced upregulation of CDKN1A/p21 follows p53-independent patterns. A. The mRNA levels of CDKN1A gene in AsPC-1, BxPC-3 and PANC-1 cells, and of mutant TP53 gene in BxPC-3 and PANC-1 cells, following treatment with 40 μΜ TH301, for 24 h, were examined by RT-qPCR protocols. mRNA values were normalized to IPO8 gene of reference and control (0.1% DMSO) was set to value “1”. Data (Ν = 3) are presented as Mean ± SD values. Statistical significance was assessed with Welch’s t-test. Asterisks indicate comparisons in between control (0.1% DMSO) and TH301-treated cells, at statistical significance levels of 0.05 and below (*: < 0.05; **: < 0.01; ***: < 0.001). B. γH2AX (p-H2AX-Ser139), p21, total p53 and p-p53-Ser15 (p53 phosphorylated form at Ser15) protein levels in PDAC cells, following treatment with 40 μΜ TH301, for 24 h, being examined by Western blotting. C. Relative protein level quantification (γH2AX {p-H2AX-Ser139}, p21, p53 and p-p53-Ser15), after normalizing densitometry values to β-Actin protein of reference, in all 3 PDAC cell lines.

Figure 3.

TH301-induced upregulation of CDKN1A/p21 follows p53-independent patterns. A. The mRNA levels of CDKN1A gene in AsPC-1, BxPC-3 and PANC-1 cells, and of mutant TP53 gene in BxPC-3 and PANC-1 cells, following treatment with 40 μΜ TH301, for 24 h, were examined by RT-qPCR protocols. mRNA values were normalized to IPO8 gene of reference and control (0.1% DMSO) was set to value “1”. Data (Ν = 3) are presented as Mean ± SD values. Statistical significance was assessed with Welch’s t-test. Asterisks indicate comparisons in between control (0.1% DMSO) and TH301-treated cells, at statistical significance levels of 0.05 and below (*: < 0.05; **: < 0.01; ***: < 0.001). B. γH2AX (p-H2AX-Ser139), p21, total p53 and p-p53-Ser15 (p53 phosphorylated form at Ser15) protein levels in PDAC cells, following treatment with 40 μΜ TH301, for 24 h, being examined by Western blotting. C. Relative protein level quantification (γH2AX {p-H2AX-Ser139}, p21, p53 and p-p53-Ser15), after normalizing densitometry values to β-Actin protein of reference, in all 3 PDAC cell lines.

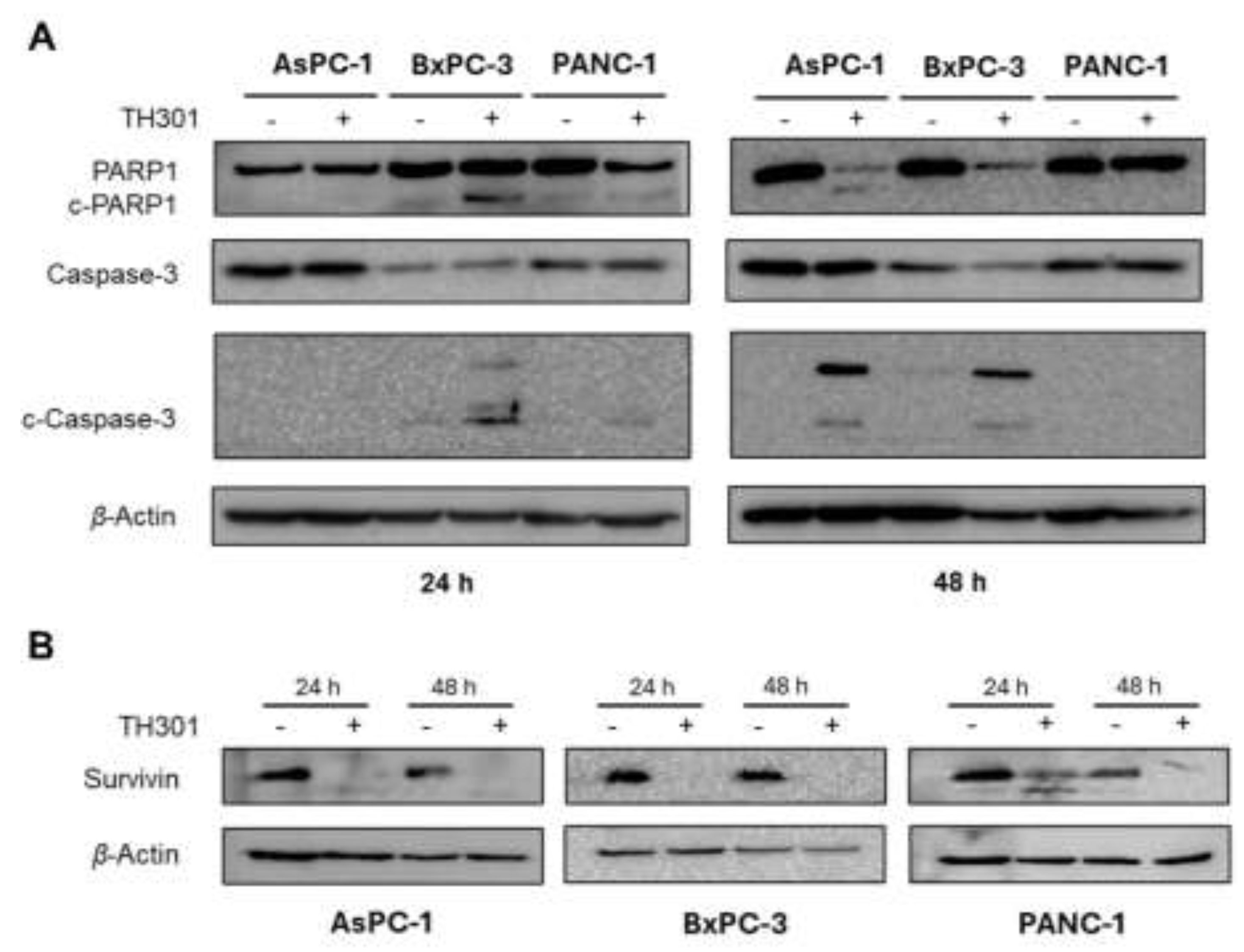

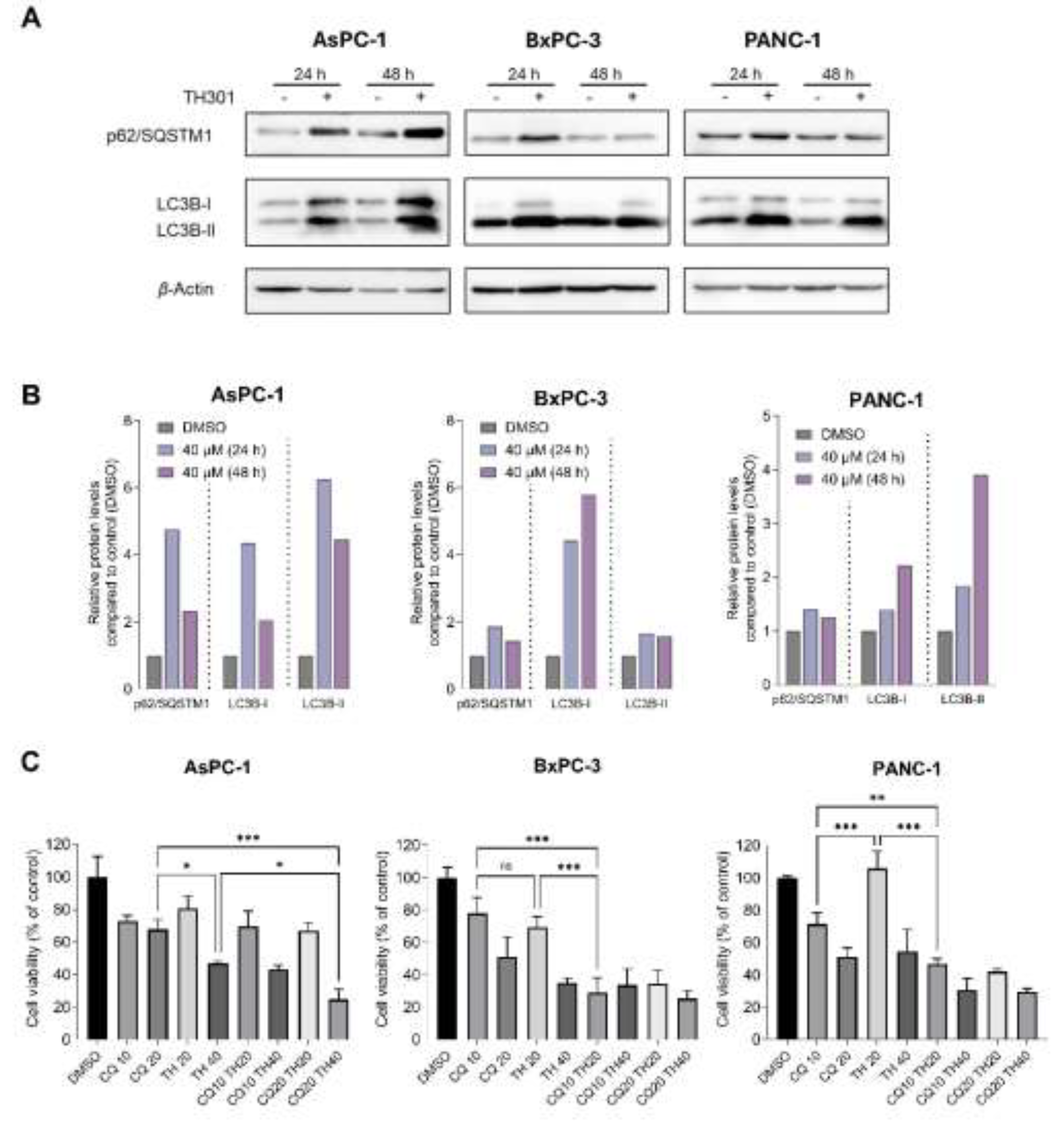

2.5. TH301 Upregulates LC3B-II-Depenent Autophagy in Pancreatic Cancer Cells, Following a Mutational Signature-Independent Pattern

Autophagy serves as a double-sword process that can play essential roles either in the survival or in the elimination of cancer cells [

38,

39,

40]. To investigate the effects of TH301 on autophagy in pancreatic cancer cell contexts, we treated the AsPC-1, BxPC-3 and PANC-1 cell lines with 40 μΜ TH301, for 24 and 48 h, and we, next, analyzed the protein expression levels of the key autophagy markers p62/SQSTM1 and LC3B-II. As described in

Figure 5A, in the presence of TH301, there is a significant induction of the LC3B-II protein isoform (and the LC3B-I), in all the 3 pancreatic cancer cell lines, herein, examined, with a simultaneous elevation of p62/SQSTM1 protein contents being also detected, albeit in a time- and cell type-dependent manners (

Figs. 5A and

5B), which may indicate either induction of autophagy or impairment of autophagic flux. To, further, clarify whether the obtained findings reflect an activation of autophagy response, we, next, co-treated cells with TH301 and Chloroquine (CQ), a known autophagy inhibitor [

41,

42], and examined cell viability. Of note, the pathogenic effect of CQ alone was evaluated via treatment of cells with CQ increasing concentrations, for 48 h, resulting in an IC

50 range of ~46 - 18 μM, for the 3 cell lines, herein, tested (

Suppl. Figure S4). Strikingly, our results unveil that TH301 can synergize productively with CQ, in BxPC-3 and PANC-1 cells, when non-toxic concentrations of both agents are administered together, whereas, in AsPC-1 cells, only the 40 μΜ dose of the TH301 clock modulator proves able to synergize with CQ in an effective manner (

Figure 5C). Altogether, our results indicate that TH301 can activate an LC3B-II-dependent autophagic program in PDAC cells of diverse mutational loads, and its (TH301) combination with CQ can enhance pancreatic cancer cell pathology, and elimination efficiency, in a dose-dependent manner. It seems that a novel therapeutic scheme of CQ-sensitizing pancreatic cancer cells to TH301-driven death opens a new window for the simultaneous modulation of autophagy and circadian clock functionalities in the clinical management of the disease.

Figure 5.

TH301 upregulates autophagy in (human) pancreatic cancer cells of diverse mutational loads. A. Western blotting profiles of the major autophagic markers p62/SQSTM1 and LC3B-II, in the presence (+) or absence (-) of 40 μΜ TH301, for 24 and 48 h (post-administration). B. Quantification of “A” conducted via measurements of densitometry values that were being normalized to β-Actin. Normalized values derived from non-treated cells were set to “1”. Presentation of relative expression of each examined protein, compared to control (0.1% DMSO, showed once), after normalizing densitometry values to β-Actin. C. Cell viability profiles (bar-charts) of PDAC cell lines after treatment with CQ (only), TH301 (only), or CQ and TH301 (together), for 48 h (post-administration). Data (N = 3) are presented as Mean ± SD values. Statistical significance was assessed with One-way ANOVA and Tuckey's multiple comparison correction.

Figure 5.

TH301 upregulates autophagy in (human) pancreatic cancer cells of diverse mutational loads. A. Western blotting profiles of the major autophagic markers p62/SQSTM1 and LC3B-II, in the presence (+) or absence (-) of 40 μΜ TH301, for 24 and 48 h (post-administration). B. Quantification of “A” conducted via measurements of densitometry values that were being normalized to β-Actin. Normalized values derived from non-treated cells were set to “1”. Presentation of relative expression of each examined protein, compared to control (0.1% DMSO, showed once), after normalizing densitometry values to β-Actin. C. Cell viability profiles (bar-charts) of PDAC cell lines after treatment with CQ (only), TH301 (only), or CQ and TH301 (together), for 48 h (post-administration). Data (N = 3) are presented as Mean ± SD values. Statistical significance was assessed with One-way ANOVA and Tuckey's multiple comparison correction.

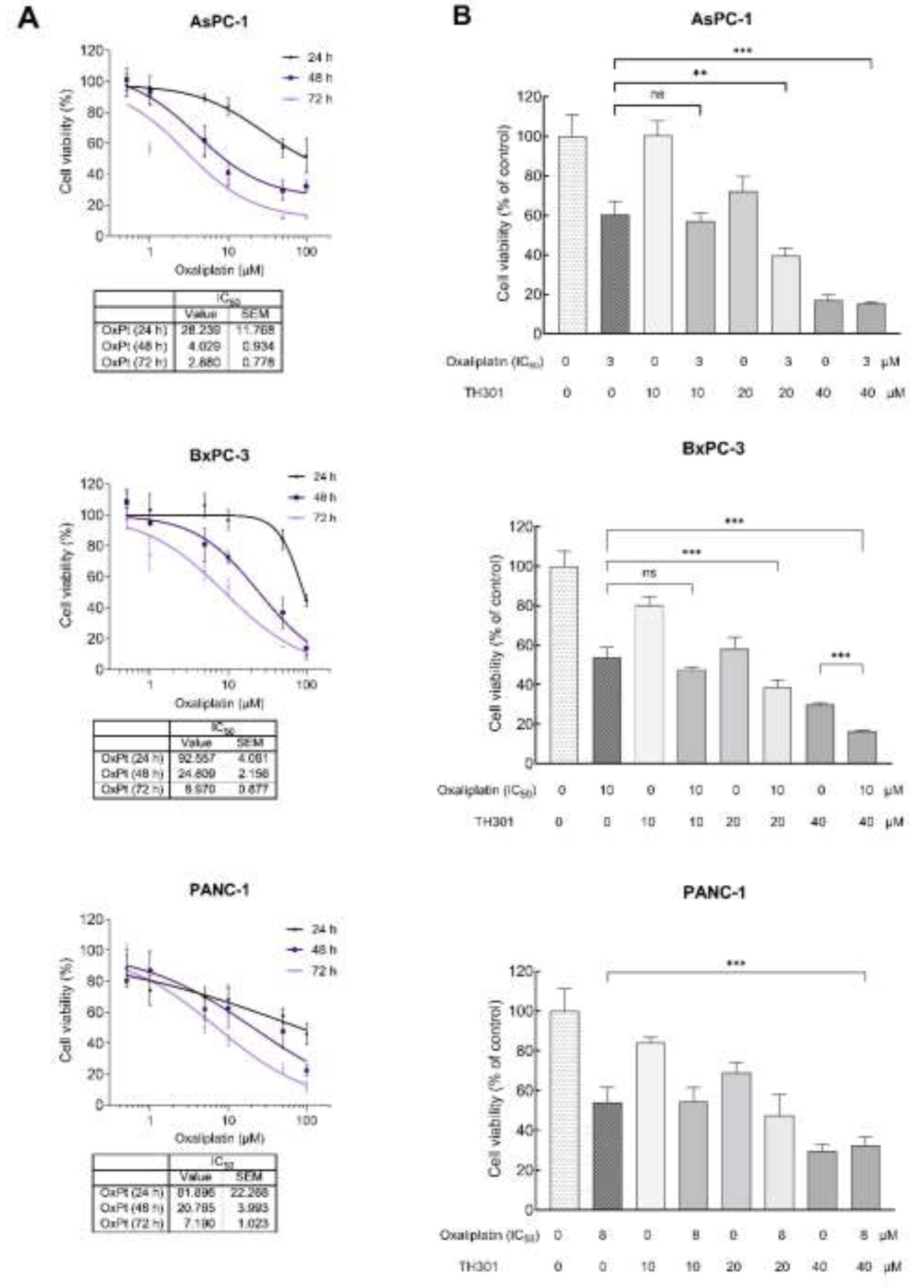

2.6. TH301 Potentiates the Cytopathic Effects of Oxaliplatin, by Reducing Pancreatic Cancer Cell Viability

Oxaliplatin is utilized in the treatment of PDAC, as critical component of combination chemotherapy regimens, such as the FolFIrinOx (Folinic Acid, Fluorouracil, Irinotecan and Oxaliplatin) drug cocktail. Given that Oxaliplatin inhibits cell proliferation, growth and survival, by inducing DNA damage, we, herein, aimed to investigate whether TH301 could synergize with Oxaliplatin to further reduce cell viability of PDAC cells. After identifying the IC50 value, for each one of the 3 cell lines (Figure 6A), we, respectively, combined this Oxaliplatin concentration with 10, 20 and 40 μM of TH301, to treat PDAC cells, for 72 h (post-administration), and cell viability was, next, quantified though MTT assay engagement. As illustrated in Figure 6B, co-treatment with TH301 and Oxaliplatin led to their significant synergism, in reducing cell viability, particularly for the AsPC-1 and BxPC-3 cell lines. However, the synergistic effect was missing from PANC-1 cells, likely due to their -specific- mutational content that can render them comparatively “semi-tolerant” to the TH301 - Oxaliplatin cocktail scheme, herein, applied. Altogether, a novel regimen, containing non-toxic doses of the TH301 and Oxaliplatin agents, seems to hold strong therapeutic promise for pancreatic cancer, in the clinic.

Figure 6.

Synergistic cytopathic effects of TH301 and Oxaliplatin agents on (human) pancreatic cancer cell survival and growth. A. Cell viability curves, after exposure of PDAC (AsPC-1, BxPC-3 and PANC-1) cells to increasing concentrations of Oxaliplatin (OxPt) (0, 1, 10 and 100 μM), for 24, 48 and 72 h, with the obtained IC50 values being, respectively, indicated. Data (N = 4) are presented as Mean ± SEM values. IC50 values were calculated with a non-linear model platform. B. Cell viability quantification was performed through MTT assay engagement, after treatment of PDAC (AsPC-1, BxPC-3 and PANC-1) cells with increasing concentrations of TH301 (0, 10, 20 and 40 μΜ), in the presence (+) or absence (-) of OxPt (IC50 concentration), for 72 h. Data (N = 4) are presented as Mean ± SEM values. Statistical significance was assessed with One-way ANOVA and Tuckey’s multiple comparison correction. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (ns: non-significant; ** < 0.01; *** < 0.001).

Figure 6.

Synergistic cytopathic effects of TH301 and Oxaliplatin agents on (human) pancreatic cancer cell survival and growth. A. Cell viability curves, after exposure of PDAC (AsPC-1, BxPC-3 and PANC-1) cells to increasing concentrations of Oxaliplatin (OxPt) (0, 1, 10 and 100 μM), for 24, 48 and 72 h, with the obtained IC50 values being, respectively, indicated. Data (N = 4) are presented as Mean ± SEM values. IC50 values were calculated with a non-linear model platform. B. Cell viability quantification was performed through MTT assay engagement, after treatment of PDAC (AsPC-1, BxPC-3 and PANC-1) cells with increasing concentrations of TH301 (0, 10, 20 and 40 μΜ), in the presence (+) or absence (-) of OxPt (IC50 concentration), for 72 h. Data (N = 4) are presented as Mean ± SEM values. Statistical significance was assessed with One-way ANOVA and Tuckey’s multiple comparison correction. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (ns: non-significant; ** < 0.01; *** < 0.001).

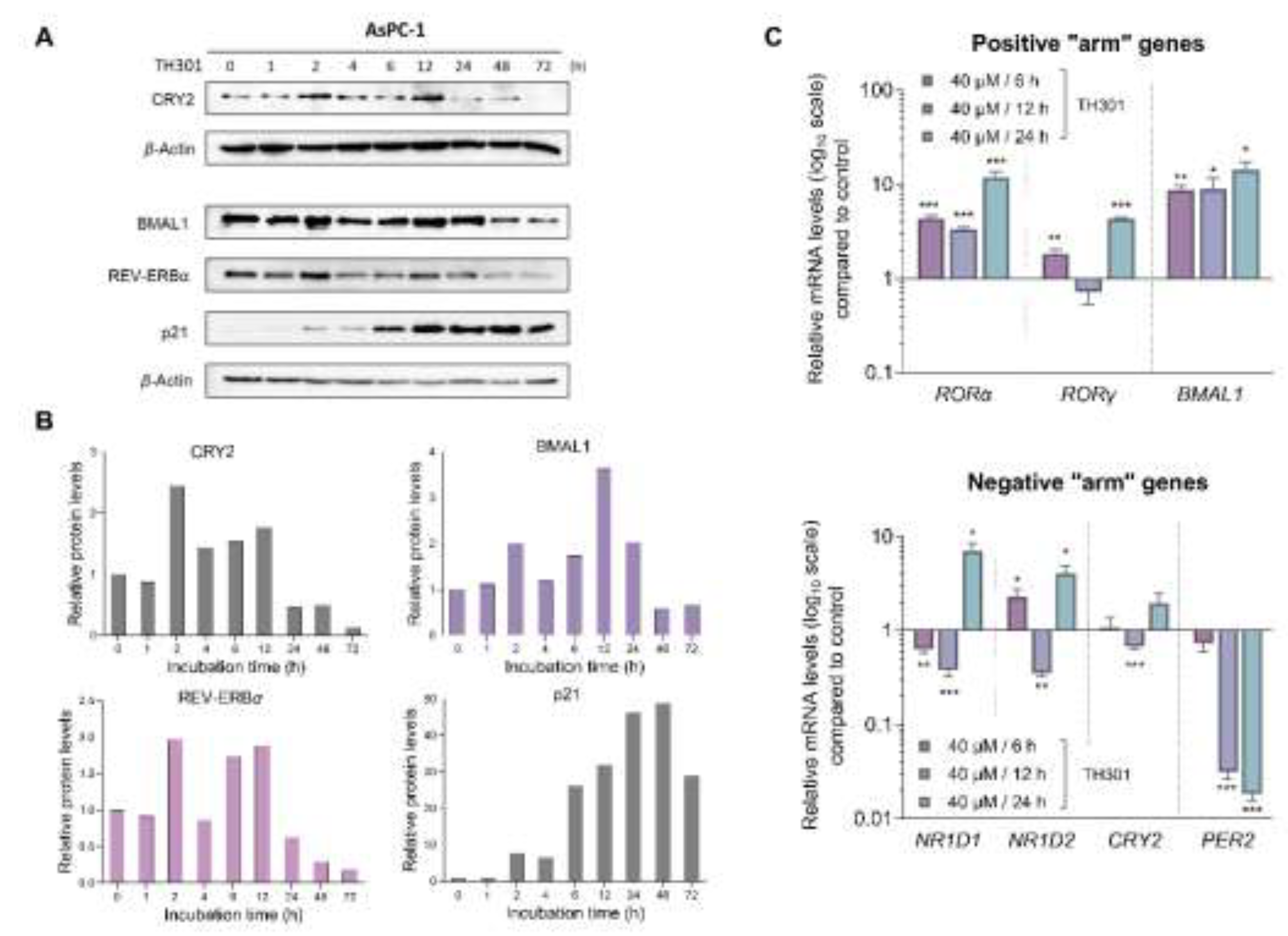

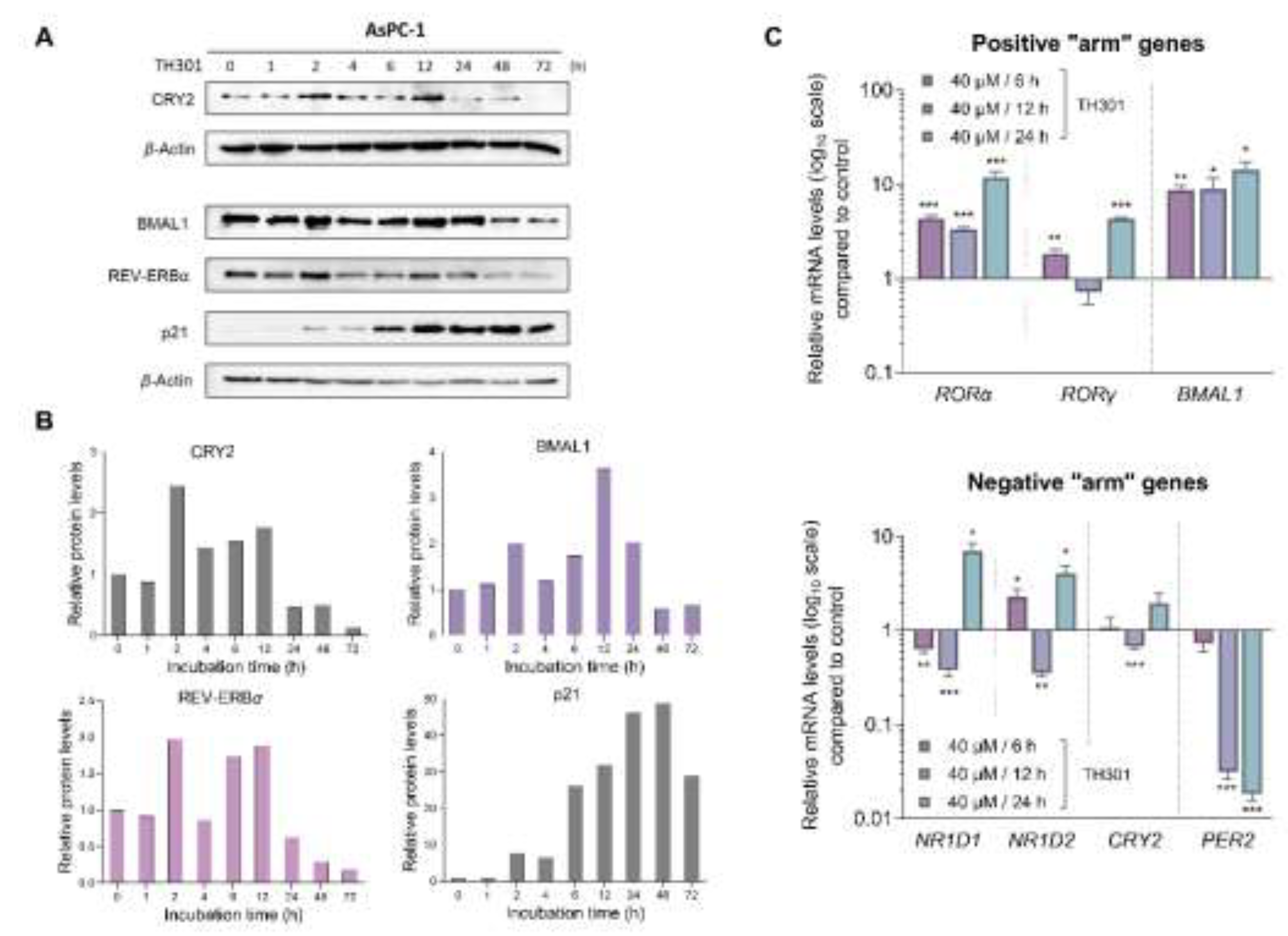

2.7. CRY2 and BMAL1 Are Not Required for the TH301-Driven Induction of p21 Cell Cycle Inhibitor in Pancreatic Cancer cells

Since TH301 is known to stabilize CRY2, we, next, sought to investigate its (TH301) effects on the expression of circadian-clock key components, which are integral determinants to both the “positive” and the “negative” arm of the circadian-clock feedback loop (

Figure 7). Hence, we utilized AsPC-1 cells, since they presented the most pronounced cytopathic responses to TH301 treatment, as compared to the other 2 cell lines, herein, analyzed (see

Figs. 1 and

2). Most importantly, AsPC-1 cells completely lack

TP53/p53 expression and activity (see

Figure 3), allowing us to minimize confounding factors, such as p53, which have been previously reported to influence, and be influenced, by the circadian clock components [

43,

44]. We, first, examined the expression levels of

RORα,

RORγ,

BMAL1 (positive “arm”),

NR1D1,

NR1D2,

CRY2 and

PER2 (negative “arm”) genes, with

RORα and

BMAL1 of the positive “arm” being presented with a notable upregulation, in response to TH301 administration (

Figure 7C; top bar-chart). To the contrary, the

PER2 gene that belongs to the negative “arm” of the clock exhibited drastic reduction in its transcriptional activity, following a time-dependent pattern, in the presence of TH301 (

Figure 7C; bottom bar-chart). Likewise,

PER2 was subjected to a strong transcriptional downregulation, after TH301 administration, in BxPC-3 and PANC-1 cells (

Suppl. Figure S5), thus indicating their (

PER2 and TH301) mutational load-independent association in PDAC settings. Furthermore, to explore the potential correlation of TH301-mediated modulation of the circadian clock with the induction of p21 cell cycle inhibitor, we analyzed and quantified the expression levels of CRY2, BMAL1, REV-ERBα and p21 proteins, after treating AsPC-1 cells with 40 μM TH301, for various time-periods (0 - 72 h).

Figures 7A and

7B describe the ability of TH301 to cause detectable elevations of CRY2, BMAL1 and REV-ERBα protein contents, albeit at different time-points of the treatment period. Although the levels of circadian clock proteins are significantly decreased after 48 and 72 h of treatment, the p21 protein expression was presented with a striking increase, in response to TH301, at the same time-points and, even, earlier (12 - 72 h), thus dictating the mechanistic uncoupling of CRY2 and BMAL1 activities from p21 protein induction. Altogether, our findings prove the TH301 proficiency (a) to perturb circadian clock integrity (e.g., via

PER2 transcriptional suppression) and (b) to induce cell cycle arrest, via a striking increase in p21 protein (and gene) levels, in (human) pancreatic cancer cells of specific mutational signatures.

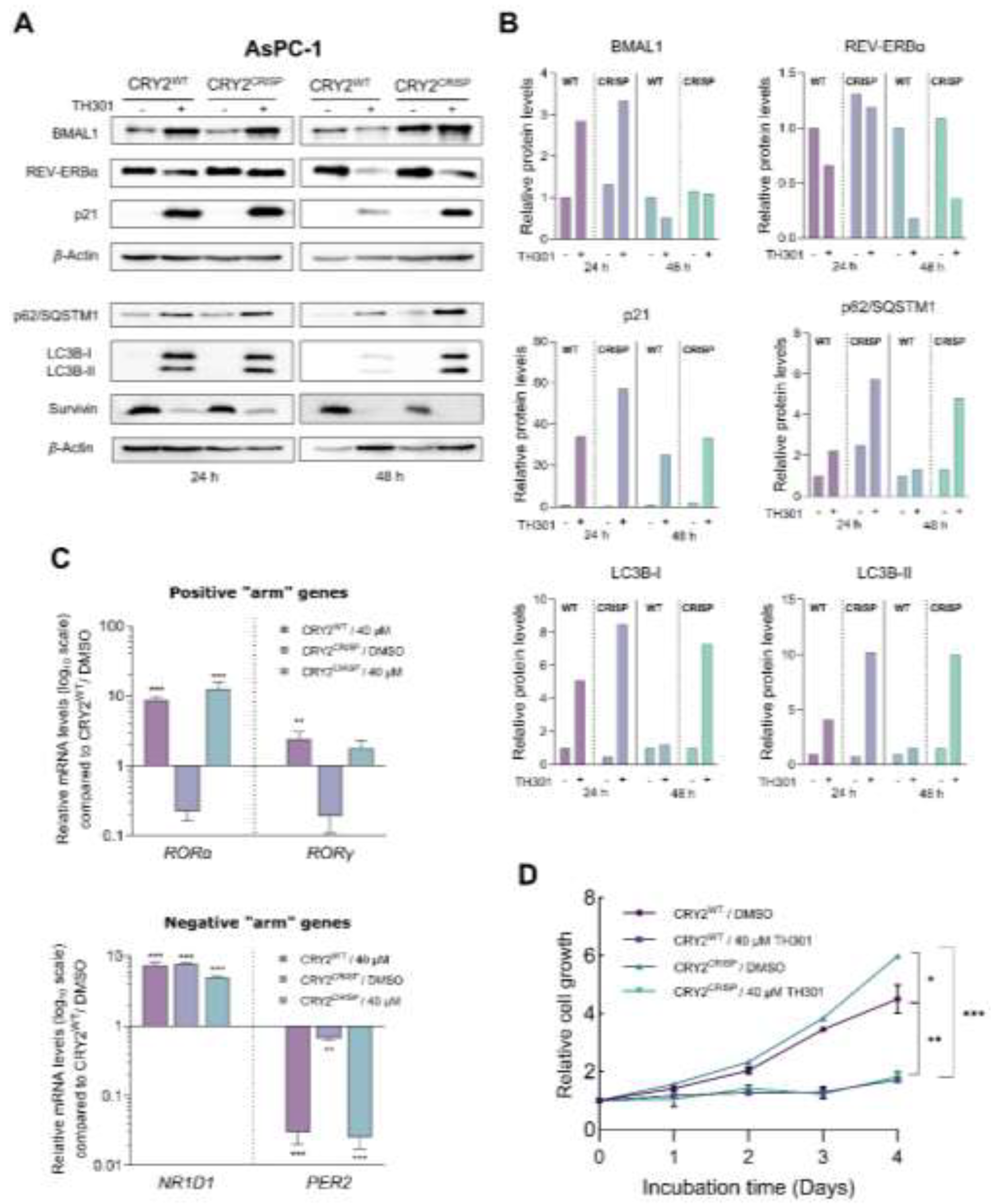

Given that TH301 can cause time-dependent alterations in CRY2 and BMAL1 expression, together with concurrent p21 induction, we, next, sought to further investigate the potential relationship between the modulation in protein levels of CRY2 or BMAL1 clock components, and the increase of p21 contents, in the presence of TH301. To explore this, we, herein, attempted to knock-out CRY2 or knock-down BMAL1 in AsPC-1 cells. Following these gene-targeting protocols, we treated cells with TH301 and analyzed p21 protein levels, for all experimental conditions applied in AsPC-1 cells (e.g., CRY2WT and CRY2CRISP, in the absence and presence of TH301). For the -partial- loss of CRY2, we employed a dual gRNA - CRISPR/Cas9 Lentiviral system, which resulted in a ~3.4 Kb deletion, encompassing Exons 3-5 of the CRY2 gene locus (Suppl. Figure S6). Of note, we were unable to isolate homozygous clones for the deletion, likely due to the essential role(s) of CRY protein in pancreatic cancer cell survival and growth, and, thus, we proceeded with the heterozygous AsPC-1 cells, for further analysis. As described in Figure 8A, -partial- loss of CRY2 (CRY2CRISP) could not affect the TH301-driven induction of p21 protein, as compared to control (CRY2WT) cells. Likewise, CRY2CRISP (AsPC-1) cells were not presented with major perturbations in the expression profiles of BMAL1 and REV-ERBα proteins, and of the circadian clock genes RORα, RORγ, NR1D1 and PER2 (Figs. 8A and 8C). Our findings strongly suggest that the, TH301-induced, modulation of the circadian clock components and the induction of p21 protein are two independent phenomena.

Figure 7.

TH301 modulates core clock proteins, while it induces p21 expression in PDAC cell settings. A. Western blotting profiles of the major circadian clock proteins CRY2, BMAL1 and REV-ERBα, and the cardinal cell cycle regulator p21, after treatment of AsPC-1 cells with 40 μΜ TH301, for 0 - 72 h. B. Quantification of relative protein levels, after normalizing densitometry values to β-Actin. Normalized treated-cell values, for the time-point t = 0 h, were set to value “1”. C. mRNA levels of the clock genes RORα, RORγ, BMAL1 (top bar-chart), NR1D1, NR1D2, CRY2 and PER2 (bottom bar-chart) in AsPC-1 cells, following treatment with 40 μΜ TH301, for 6, 12 and 24 h, being detected and quantified by RT-qPCR protocols. mRNA values were normalized to the IPO8 respective one, while control (0.1% DMSO) was set to value “1”. Data (Ν = 3) are presented as Mean ± SD values. Statistical significance was assessed with Welch’s t-test, as each time-point was considered an independent experiment. Asterisks indicate comparisons in between control (0.1% DMSO, not shown) and (TH301) treated cells, at significance levels of 0.05 and below (*: < 0.05; **: < 0.01; ***: < 0.001).

Figure 7.

TH301 modulates core clock proteins, while it induces p21 expression in PDAC cell settings. A. Western blotting profiles of the major circadian clock proteins CRY2, BMAL1 and REV-ERBα, and the cardinal cell cycle regulator p21, after treatment of AsPC-1 cells with 40 μΜ TH301, for 0 - 72 h. B. Quantification of relative protein levels, after normalizing densitometry values to β-Actin. Normalized treated-cell values, for the time-point t = 0 h, were set to value “1”. C. mRNA levels of the clock genes RORα, RORγ, BMAL1 (top bar-chart), NR1D1, NR1D2, CRY2 and PER2 (bottom bar-chart) in AsPC-1 cells, following treatment with 40 μΜ TH301, for 6, 12 and 24 h, being detected and quantified by RT-qPCR protocols. mRNA values were normalized to the IPO8 respective one, while control (0.1% DMSO) was set to value “1”. Data (Ν = 3) are presented as Mean ± SD values. Statistical significance was assessed with Welch’s t-test, as each time-point was considered an independent experiment. Asterisks indicate comparisons in between control (0.1% DMSO, not shown) and (TH301) treated cells, at significance levels of 0.05 and below (*: < 0.05; **: < 0.01; ***: < 0.001).

Next, we questioned whether the -partial- loss of CRY2 could affect the TH301-induced activation of autophagy components and reduction of Survivin contents. It seems that, in contrast to Survivin’s profile (decreased levels, in response to TH301) that remained unaffected, for both control (CRY2WT) and targeted (CRY2CRISP) cells, the two key markers of autophagy, p62/SQSTM1 and LC3B-II (and LC3B-I), were shown with similarly increased protein contents both in CRY2CRISP and in CRY2WT (AsPC-1) cells, after their exposure (24 and 48 h) to the TH301 agent (Figs. 8A and 8Β). Interestingly, treatment of CRY2WT and CRY2CRISP (AsPC-1) cells with TH301, for 4 consecutive days, resulted in significantly reduced cell growth rates, for both cell types (Figure 8D), although (TH301) untreated CRY2CRISP cells showed a slightly increased growth rate compared to their CRY2WT counterparts.

Figure 8.

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeting of CRY2 does not affect p21 induction by TH301, in pancreatic cancer cells. A. Western blotting of (a) the clock proteins BMAL1 and REV-ERBα, (b) the autophagy markers p62/SQSTM1 and LC3B-II (and LC3B-I), (c) the cell cycle regulator p21 and (d) the apoptosis inhibitor Survivin, after treating wild-type (CRY2WT) and targeted -heterozygous- (CRY2CRISP) AsPC-1 cells with 40 μΜ TH301, for 24 and 48 h. B. Relative protein levels, after normalization of densitometry values to β-Actin. Normalized CRY2WT values, for 24 and 48 h, were set to value “1”. C. Quantification of mRNA transcript levels of the clock genes RORα and RORγ (positive “arm”), and NR1D1 and PER2 (negative “arm”), in CRY2WT and CRY2CRISP AsPC-1 cells, following treatment with 40 μΜ TH301, for 24 h, being conducted by RT-qPCR protocol. GAPDH served as gene of reference, and the CRY2WT control (0.1% DMSO) was set to value “1”. Data (Ν = 3) are presented as Mean ± SD values. Statistical significance was assessed via One-Way ANOVA, with Dunnet’s multiple comparison correction. Asterisks indicate comparisons of control (CRY2WT, 0.1% DMSO; not shown) to treated CRY2WT, non-treated and treated -heterozygous- CRY2CRISP, AsPC-1, cells, at significance levels of “0.05” and below values (*: < 0.05; **: < 0.01; ***: < 0.001). D. Relative cell growth rates of CRY2WT and CRY2CRISP AsPC-1 cells, in the absence or presence of 40 μΜ TH301, for 0 - 4 days. Data (N = 4) are presented as Mean ± SD values. Statistical significance was assessed with One-way ANOVA, via Tuckey’s multiple comparison correction. Asterisks indicate comparisons in between paired groups, after 0 - 4 days of TH301 exposure (*: < 0.05; **: < 0.01; ***: < 0.001).

Figure 8.

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeting of CRY2 does not affect p21 induction by TH301, in pancreatic cancer cells. A. Western blotting of (a) the clock proteins BMAL1 and REV-ERBα, (b) the autophagy markers p62/SQSTM1 and LC3B-II (and LC3B-I), (c) the cell cycle regulator p21 and (d) the apoptosis inhibitor Survivin, after treating wild-type (CRY2WT) and targeted -heterozygous- (CRY2CRISP) AsPC-1 cells with 40 μΜ TH301, for 24 and 48 h. B. Relative protein levels, after normalization of densitometry values to β-Actin. Normalized CRY2WT values, for 24 and 48 h, were set to value “1”. C. Quantification of mRNA transcript levels of the clock genes RORα and RORγ (positive “arm”), and NR1D1 and PER2 (negative “arm”), in CRY2WT and CRY2CRISP AsPC-1 cells, following treatment with 40 μΜ TH301, for 24 h, being conducted by RT-qPCR protocol. GAPDH served as gene of reference, and the CRY2WT control (0.1% DMSO) was set to value “1”. Data (Ν = 3) are presented as Mean ± SD values. Statistical significance was assessed via One-Way ANOVA, with Dunnet’s multiple comparison correction. Asterisks indicate comparisons of control (CRY2WT, 0.1% DMSO; not shown) to treated CRY2WT, non-treated and treated -heterozygous- CRY2CRISP, AsPC-1, cells, at significance levels of “0.05” and below values (*: < 0.05; **: < 0.01; ***: < 0.001). D. Relative cell growth rates of CRY2WT and CRY2CRISP AsPC-1 cells, in the absence or presence of 40 μΜ TH301, for 0 - 4 days. Data (N = 4) are presented as Mean ± SD values. Statistical significance was assessed with One-way ANOVA, via Tuckey’s multiple comparison correction. Asterisks indicate comparisons in between paired groups, after 0 - 4 days of TH301 exposure (*: < 0.05; **: < 0.01; ***: < 0.001).

Taken together, our results strongly suggest that TH301 exerts opposite actions on p21 (remarkable induction) and Survivin (notable reduction) protein expression patterns that occur independently of CRY2 modulation in (human) pancreatic cancer cell settings. Nevertheless, a “gene dose-specific effect”, with the CRY2-gene knock-out homozygosity, but not heterozygosity, being likely indispensable for presumable development of severe impairments in gene transcription activities, upon PDAC cell exposure to TH301, cannot be excluded, and, thus, requires further exploration.

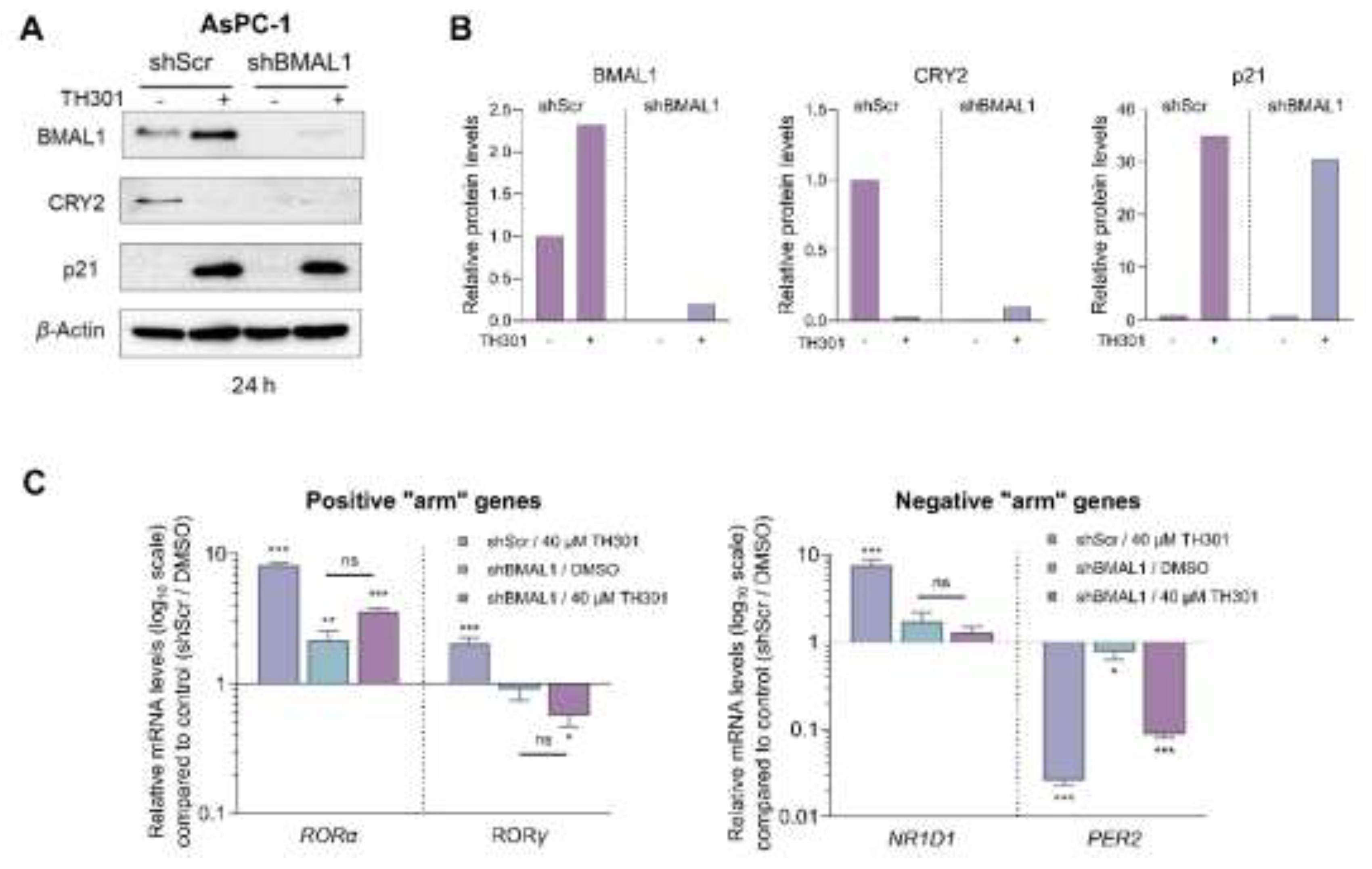

Since we observed a notable, TH301-induced, increase of its protein contents, 24 h post-administration, BMAL1 was, next, examined for a presumable functional association with the p21 cell cycle inhibitor (Figure 9). Hence, we specifically knocked-down BMAL1 in AsPC-1 cells, through employment of the shRNA-based technology (Suppl. Figure S7), and, subsequently, determined p21 protein levels. As shown in Figures 9A and 9B, knock-down of BMAL1 (shBMAL1) proved unable to affect the TH301-mediated induction of p21 protein contents. Interestingly, CRY2 levels were significantly reduced in untreated BMAL1 knock-down (shBMAL1) cells, and did not increase after (TH301) treatment, thereby suggesting the lack of any mechanistic correlation in between BMAL1 or CRY2 with p21 induction, in response to TH301 clock modulator. Of note, transcriptional activities of other critical clock genes, herein, examined, such as the RORα, RORγ, NR1D1 and PER2 ones, in BMAL1 knock-down (shBMAL1) cells, were not significantly affected by TH301 administration, compared to Scramble (control) (shScr) cells. Taken together, our findings reveal, for the first time, the BMAL1-independent induction of p21 protein, in response to TH301, and demonstrate that modulation of the circadian clock components cannot influence p21 upregulation by TH301, in human pancreatic cancer cell environments.

Figure 9.

shRNA-mediated BMAL1 knock-down does not affect p21 induction by TH301, in pancreatic cancer cells. A. Western blotting of (a) the clock proteins BMAL1 and CRY2, and (b) the cell cycle regulator p21, after treating control (shScr) and BMAL1 knock-down (shBMAL1), AsPC-1, cells, with 40 μΜ TH301, for 24 h. B. Relative protein levels, after normalizing densitometry values to β-Actin. Normalized shScr values were set to value “1”. C. Quantification of mRNA transcript levels of the clock genes RORα, RORγ, NR1D1, and PER2, in shScr and shBMAL1 AsPC-1 cells, following treatment with 40 μΜ TH301, for 24 h, being performed by RT-qPCR protocols. mRNA values were normalized to GAPDH, while control (shScr, 0.1% DMSO) was set to value “1”. Data (Ν = 3) are presented as Mean ± SD values. Statistical significance was assessed via One-Way ANOVA, with Dunnet’s multiple comparison correction. Asterisks indicate paired comparisons between control shScr (0.1% DMSO; not shown), (TH301) treated shScr, non-treated and (TH301) treated shBMAL1, AsPC-1, cells, at significance levels of “0.05” and below values (ns: non-significant; *: < 0.05; **: < 0.01; ***: < 0.001).

Figure 9.

shRNA-mediated BMAL1 knock-down does not affect p21 induction by TH301, in pancreatic cancer cells. A. Western blotting of (a) the clock proteins BMAL1 and CRY2, and (b) the cell cycle regulator p21, after treating control (shScr) and BMAL1 knock-down (shBMAL1), AsPC-1, cells, with 40 μΜ TH301, for 24 h. B. Relative protein levels, after normalizing densitometry values to β-Actin. Normalized shScr values were set to value “1”. C. Quantification of mRNA transcript levels of the clock genes RORα, RORγ, NR1D1, and PER2, in shScr and shBMAL1 AsPC-1 cells, following treatment with 40 μΜ TH301, for 24 h, being performed by RT-qPCR protocols. mRNA values were normalized to GAPDH, while control (shScr, 0.1% DMSO) was set to value “1”. Data (Ν = 3) are presented as Mean ± SD values. Statistical significance was assessed via One-Way ANOVA, with Dunnet’s multiple comparison correction. Asterisks indicate paired comparisons between control shScr (0.1% DMSO; not shown), (TH301) treated shScr, non-treated and (TH301) treated shBMAL1, AsPC-1, cells, at significance levels of “0.05” and below values (ns: non-significant; *: < 0.05; **: < 0.01; ***: < 0.001).