Submitted:

03 December 2024

Posted:

05 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

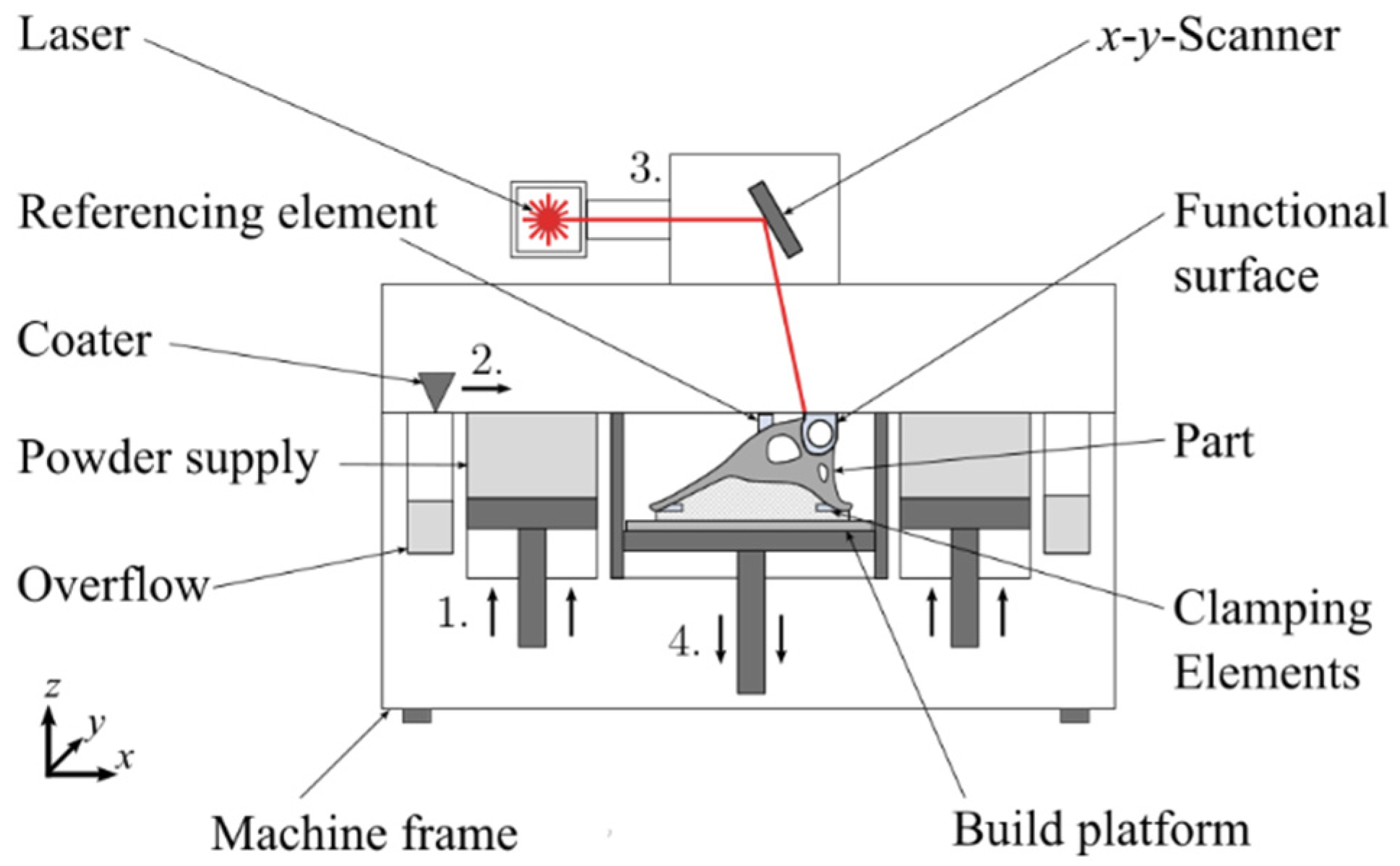

2. Materials and Methods

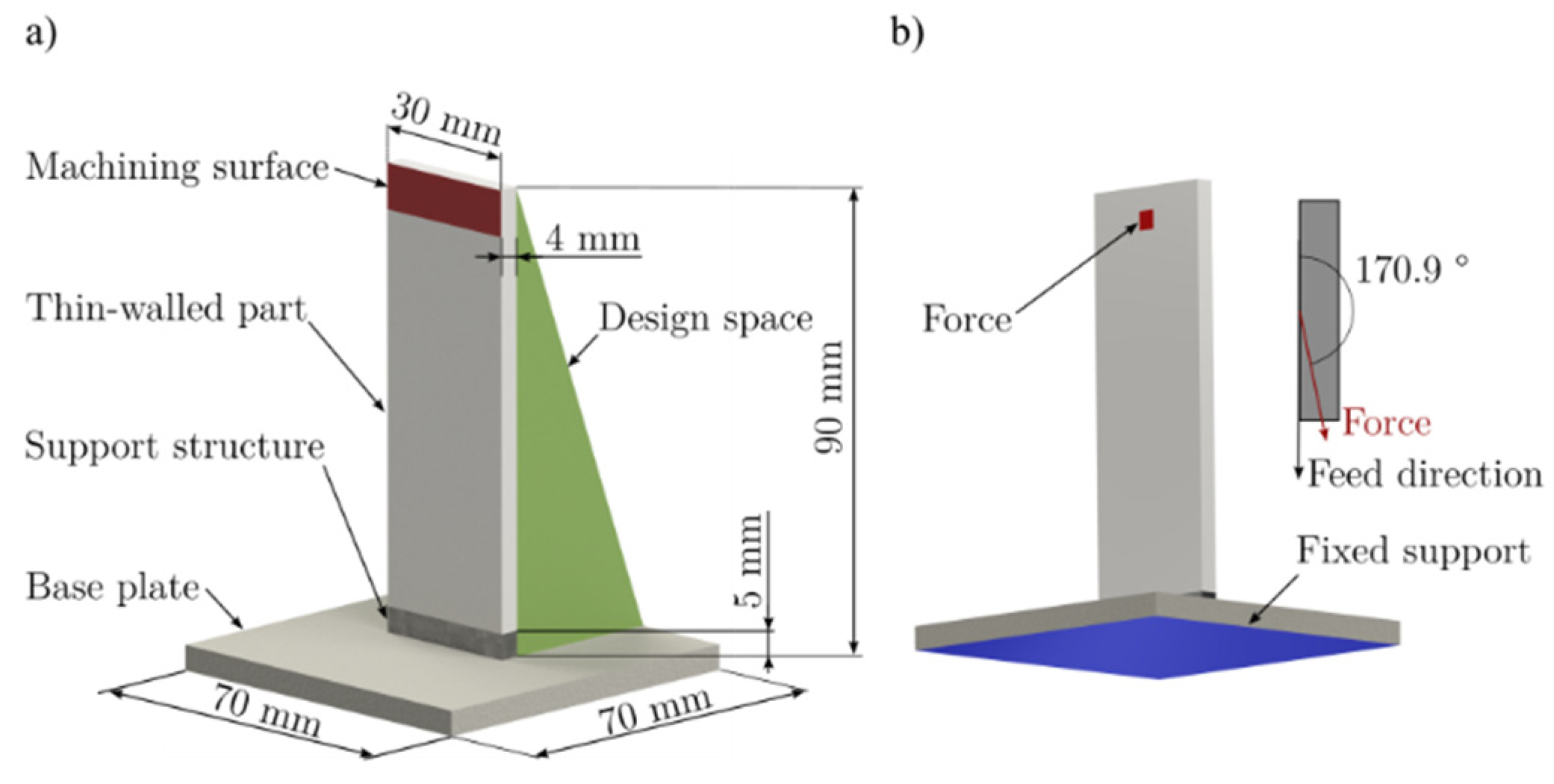

2.1. Probe Geometry and Machining Operation

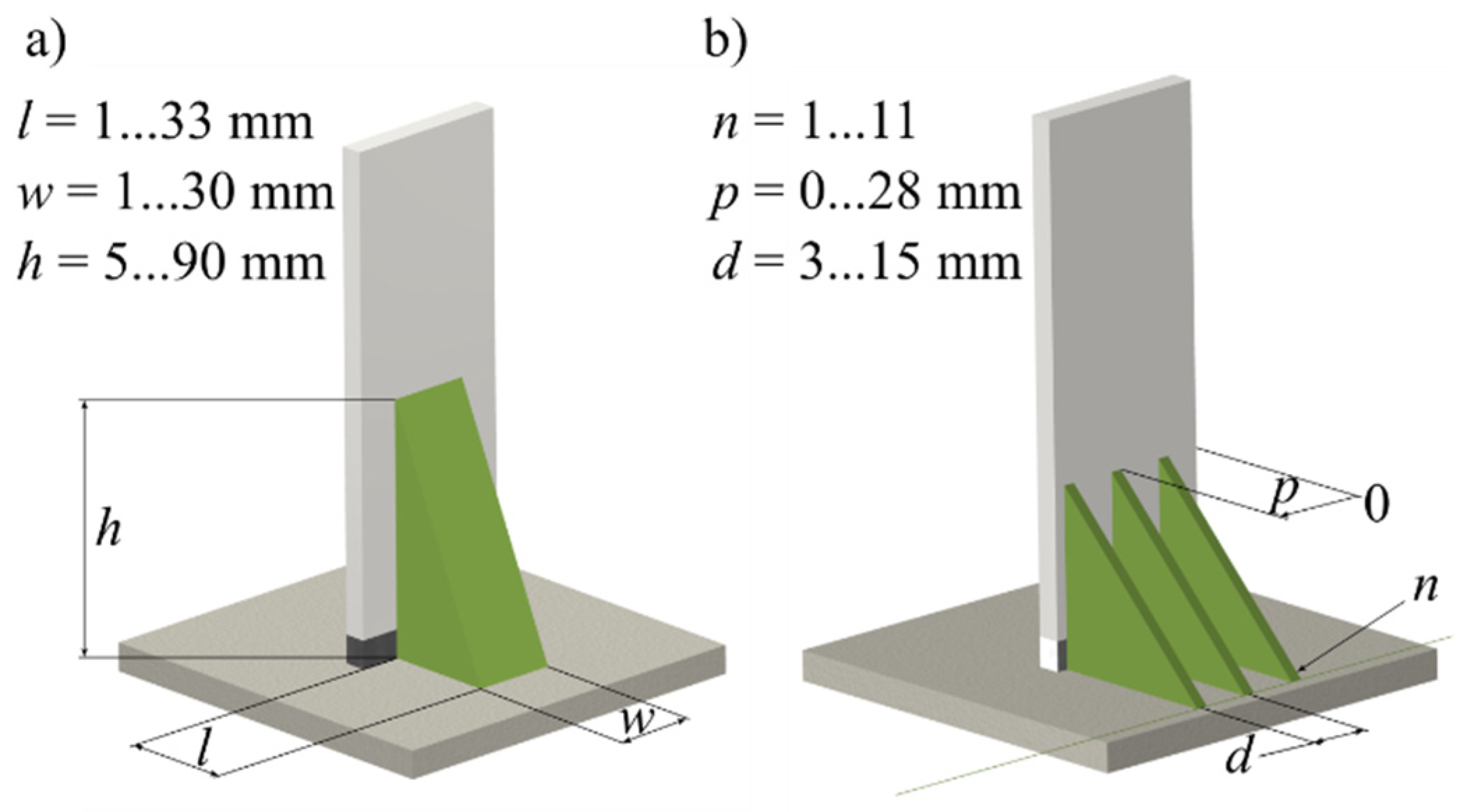

2.2. Design Parameter Study

2.3. Vibration Analysis of a Machined Surface

3. Results

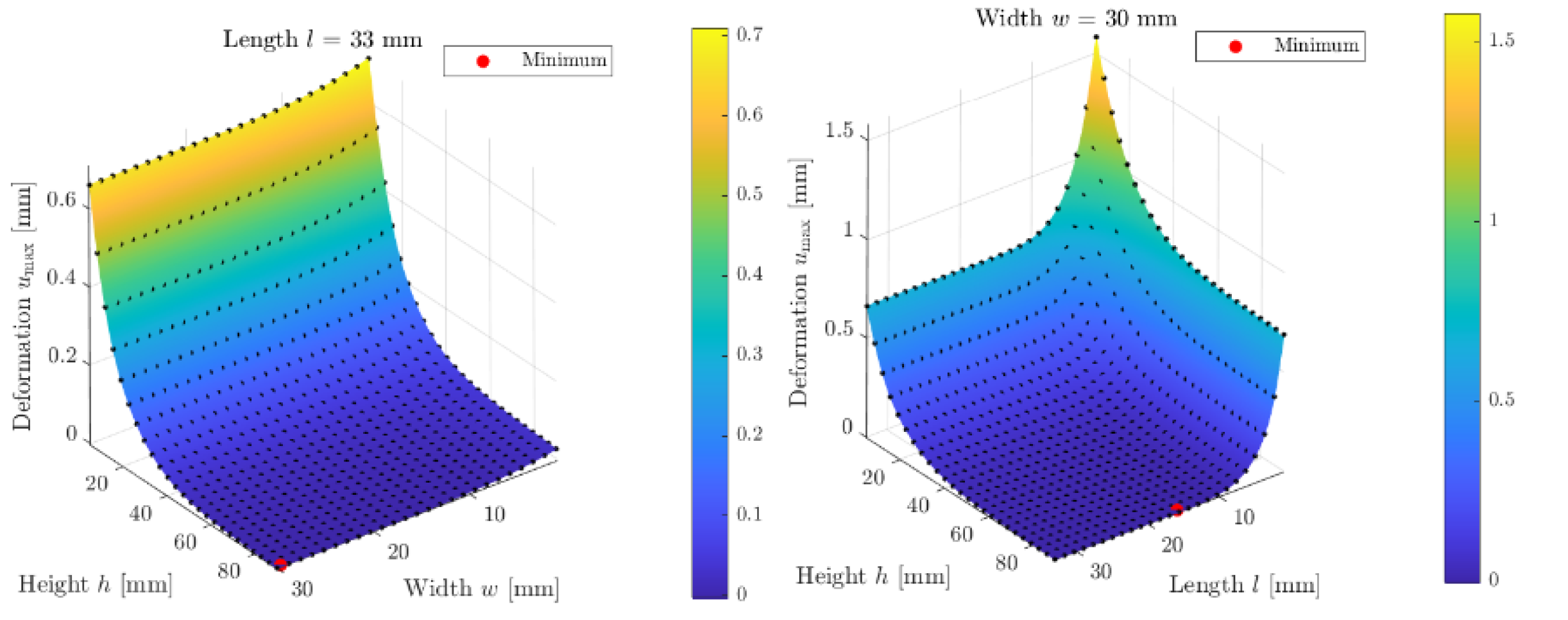

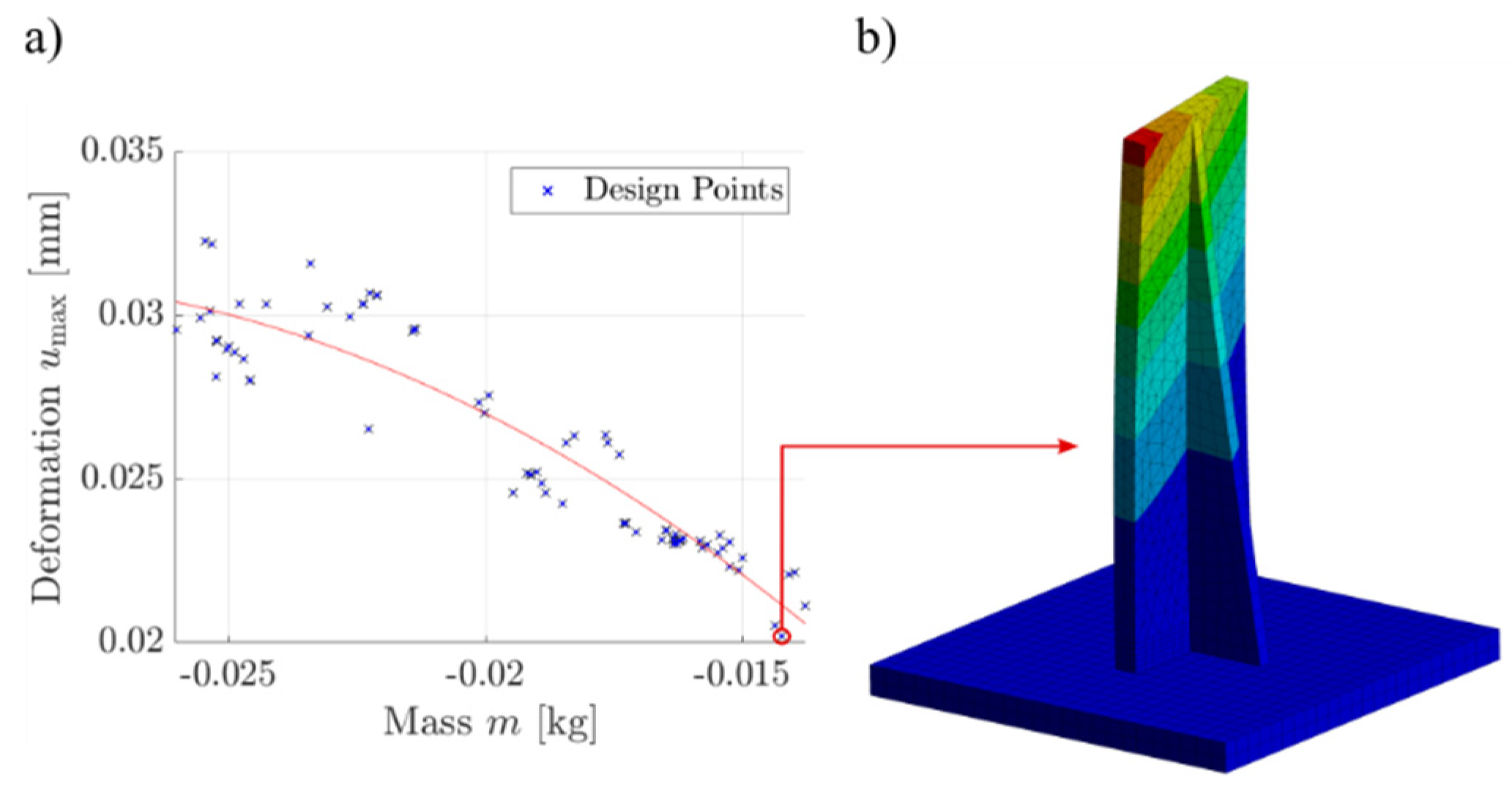

3.1. Length, Width and Height of Stiffening Structures

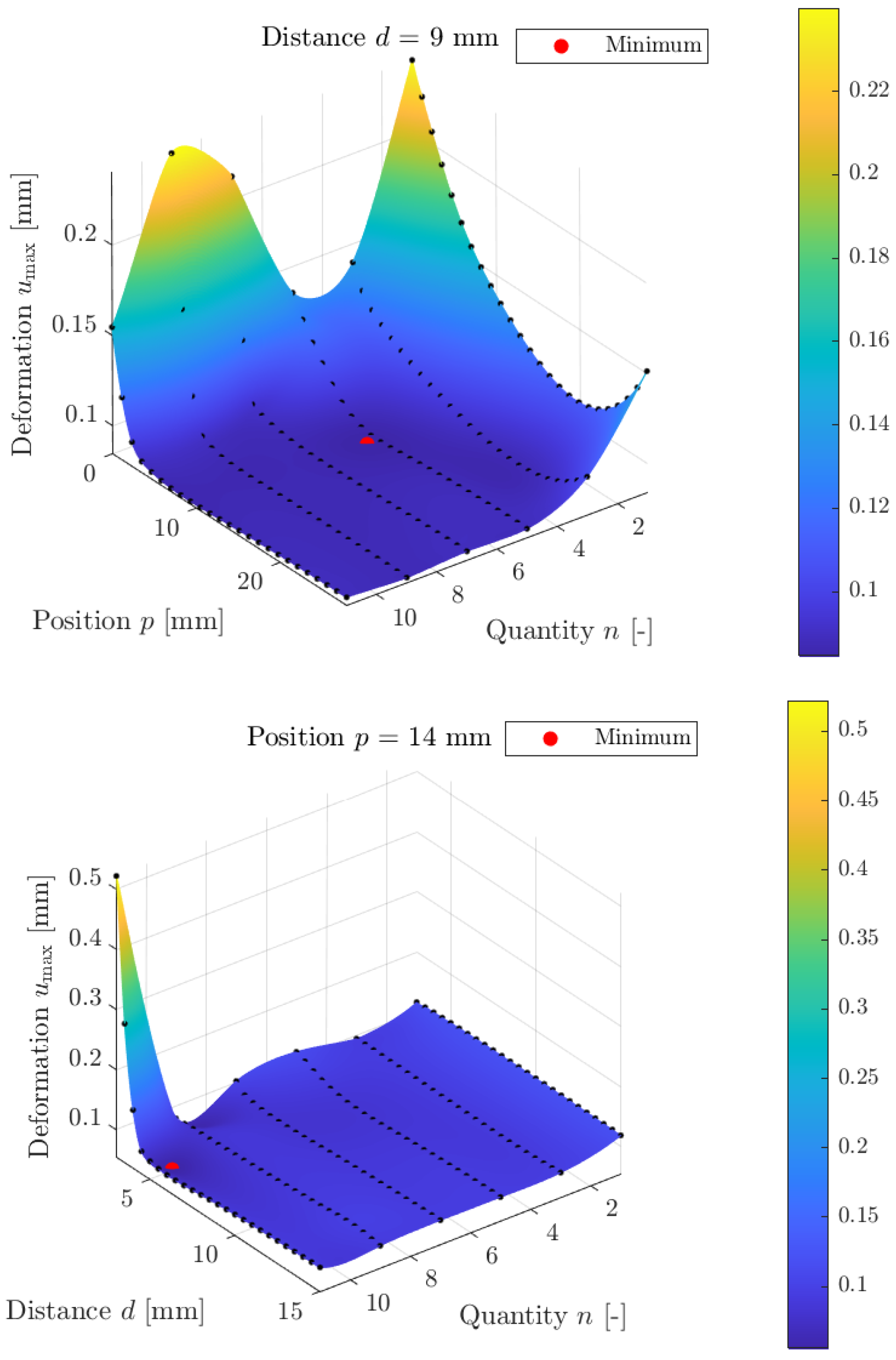

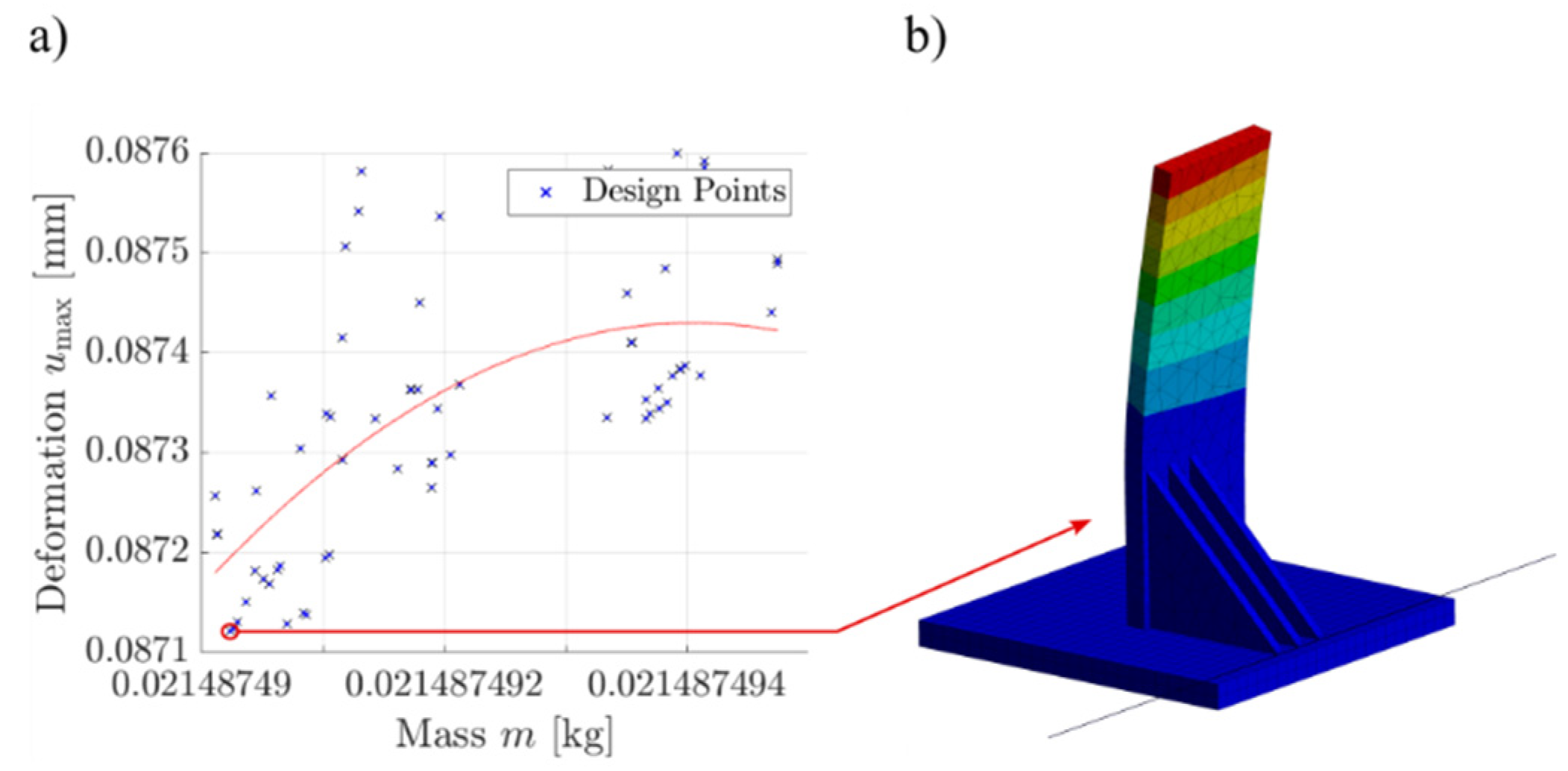

3.2. Position, Distance and Quantity Of Stiffening Structures

4. Discussion—Design Guidelines of Stiffening Structures

4.1. Length, Width and Height Of Stiffening Structures

4.2. Position, Distance and Quantity of Stiffening Structures

5. Conclusions and Outlook

Acknowledgements

References

- Lachmayer, R.; Ehlers, T.; Lippert, R.B. Design for Additive Manufacturing; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, J.P.; Niedermeyer, J.; Bernhard, R.; Hermsdorf, J.; et al. Design of additively manufacturable injection molds with conformal cooling. 2022, 111, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, T.; Meyer, I.; Oel, M.; Bode, B.; et al. Effect-Engineering by Additive Manufacturing. p. 1. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, I.; Bourell, D.; Gibson, I. Additive manufacturing: rapid prototyping comes of age. 2012, 18, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedermeyer, J.; Ehlers, T.; Lachmayer, R. Potential of additively manufactured particle damped compressor blades: A literature review. 2023, 119, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulhameed, O.; Al-Ahmari, A.; Ameen, W.; Mian, S.H. Additive manufacturing: Challenges, trends, and applications. 2019, 11, 168781401882288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugwagwa, L.; Dimitrov, D.; Matope, S.; Yadroitsev, I. Influence of process parameters on residual stress related distortions in selective laser melting. 2018, 21, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonelli, M.; Tse, Y.Y.; Tuck, C. Effect of the build orientation on the mechanical properties and fracture modes of SLM Ti-6Al-4V. 2014, 616, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, M. Surface roughness optimisation for selective laser melting (SLM). In Laser Additive Manufacturing; Elsevier, 2017; p. 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rott, S.; Ladewig, A.; Friedberger, K.; Casper, J.; et al. Surface roughness in laser powder bed fusion – Interdependency of surface orientation and laser incidence. 2020, 36, 101437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinksmeier, E.; Levy, G.; Meyer, D.; Spierings, A.B. Surface integrity of selective-laser-melted components. 2010, 59, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldschmidt, J.; Lindecke, P.; Wichmann, M.; Denkena, B.; et al. Improved Machining of Additive Manufactured Workpieces Using a Systematic Clamping Concept and Automated Process Planning. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Du, W.; Bai, Q.; Zhang, B. A Novel Method for Additive/Subtractive Hybrid Manufacturing of Metallic Parts. 2016, 5, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GRZESIK, W.; Ruszaj, A. Hybrid Manufacturing Processes: Physical Fundamentals, Modelling and Rational Applications, 1st ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.-S.; Lee, S.; Shin, B.; Whang, K.; et al. Development of a direct metal freeform fabrication technique using CO2 laser welding and milling technology. 2001, 113, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Shen, C.; Pan, Z.; Cuiuri, D.; et al. Towards an automated robotic arc-welding-based additive manufacturing system from CAD to finished part. 2016, 73, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, A.; Bidare, P.; Hassanin, H.; Tarlochan, F.; et al. Powder-based laser hybrid additive manufacturing of metals: a review. 2021, 114, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslo, S.; Menezes, B.; Kienast, P.; Ganser, P.; et al. Improving dynamic process stability in milling of thin-walled workpieces by optimization of spindle speed based on a linear parameter-varying model. 2020, 93, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klocke, F. Fertigungsverfahren 1; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalik, P.; Zajac, J.; Hatala, M.; Mital, D.; et al. Monitoring surface roughness of thin-walled components from steel C45 machining down and up milling. 2014, 58, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denkena, B.; Tönshoff, H.K. Spanen: Grundlagen, 3rd ed.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Altintas, Y.; Kersting, P.; Biermann, D.; Budak, E.; et al. Virtual process systems for part machining operations. 2014, 63, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seguy, S.; Dessein, G.; Arnaud, L. Surface roughness variation of thin wall milling, related to modal interactions. 2008, 48, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, G.; Dornfeld, D.; Denkena, B. Advancing Cutting Technology. 2023, 52, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abele, E.; Dohnal, F.; Feulner, M.; Sielaff, T.; et al. Numerical investigation of chatter suppression via parametric anti-resonance in a motorized spindle unit during milling. 2018, 12, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachmayer, R.; Ehlers, T.; Lippert, R.B. Entwicklungsmethodik für die Additive Fertigung; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manogharan, G.; Wysk, R.; Harrysson, O.; Aman, R. AIMS—A Metal Additive-hybrid Manufacturing System: System Architecture and Attributes. 2015, 1, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutler, P.; Ferchow, J.; Schlüssel, M.; Meboldt, M. Semi-Automated Design Workflow for Bolt Clamping Interfaces to Post-Process Additive Manufactured Parts. 2023, 119, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maucher, C.; Kordmann, L.; Möhring, H.-C. Design Rules for the Additive-Subtractive Process Chain. 2023, 119, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didier, P.; Le Coz, G.; Robin, G.; Lohmuller, P.; et al. Consideration of SLM additive manufacturing supports on the stability of flexible structures in finish milling. 2021, 62, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Wilhelm, R.; Dutterer, B.; Cherukuri, H.; et al. Sacrificial structure preforms for thin part machining. 2012, 61, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, T.L.; Smith, K.S. Machining Dynamics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- m4p material solutions GmbH, 2024. m4p 316L: Technical Data Sheet.

- Thevenot, V.; Arnaud, L.; Dessein, G.; Cazenave-Larroche, G. Integration of dynamic behaviour variations in the stability lobes method: 3D lobes construction and application to thin-walled structure milling. 2006, 27, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).