Submitted:

05 December 2024

Posted:

05 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

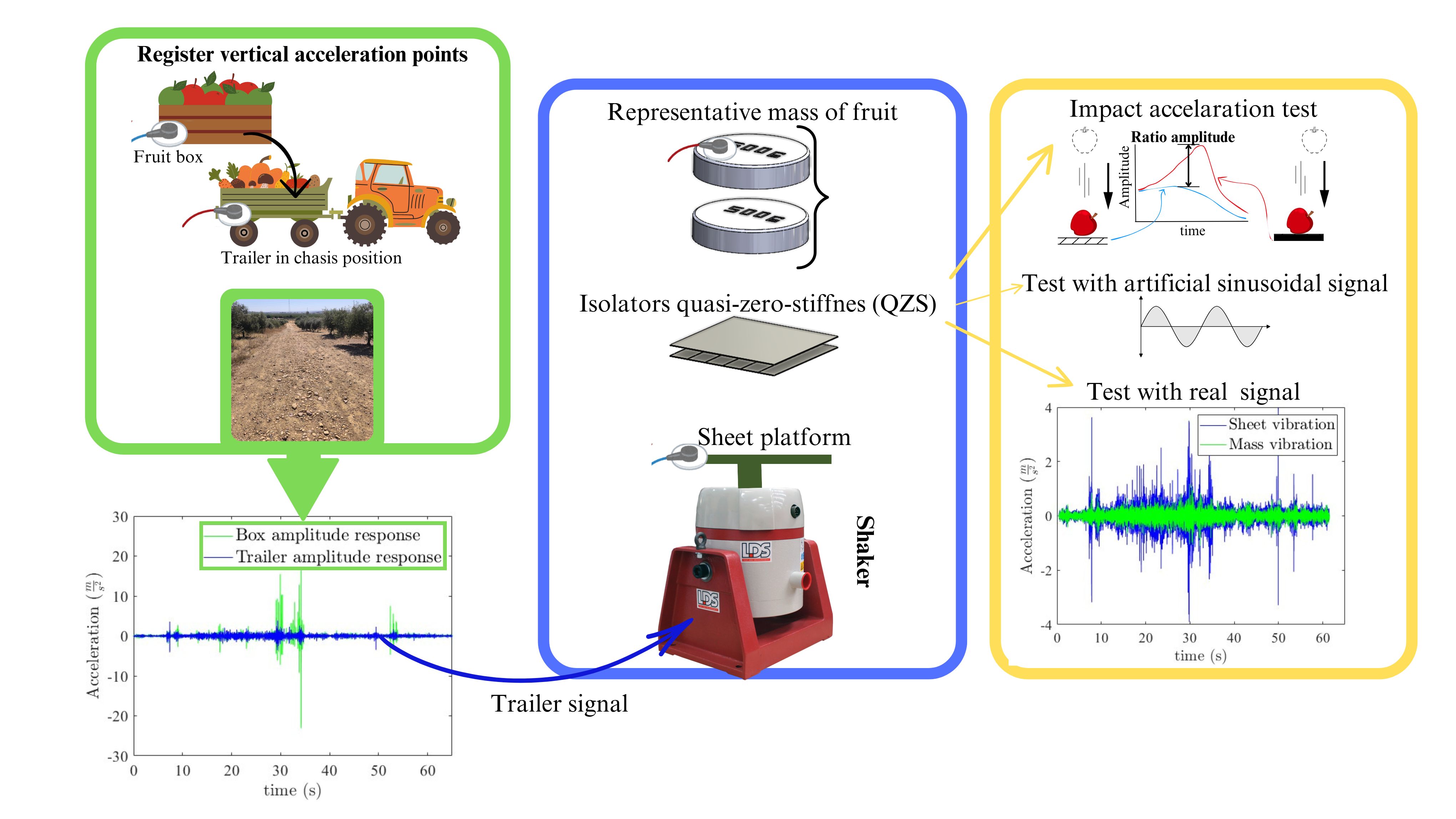

2. Materials and Methods

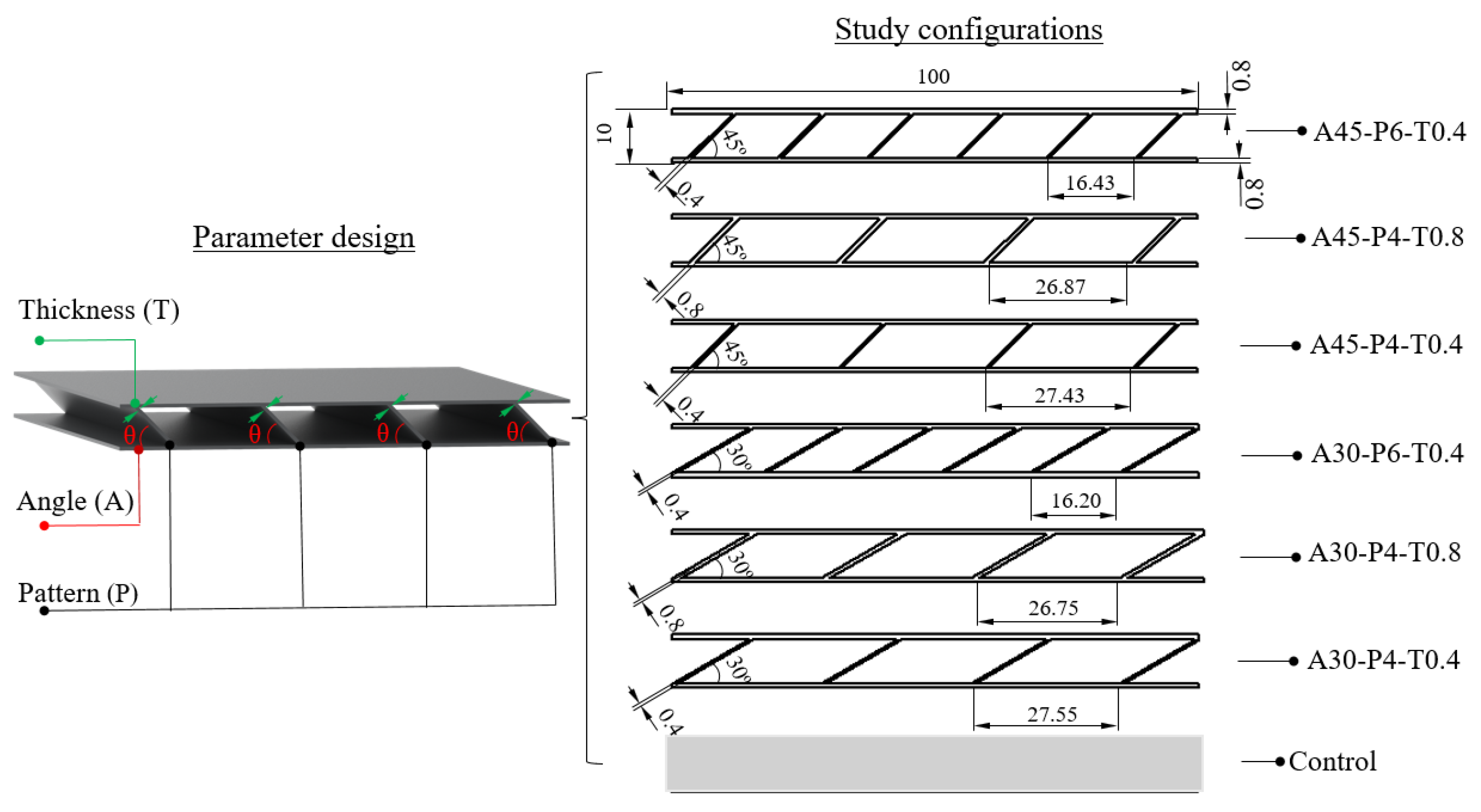

2.1. Design of Isolator Test Specimens Manufactured with 3D Printing

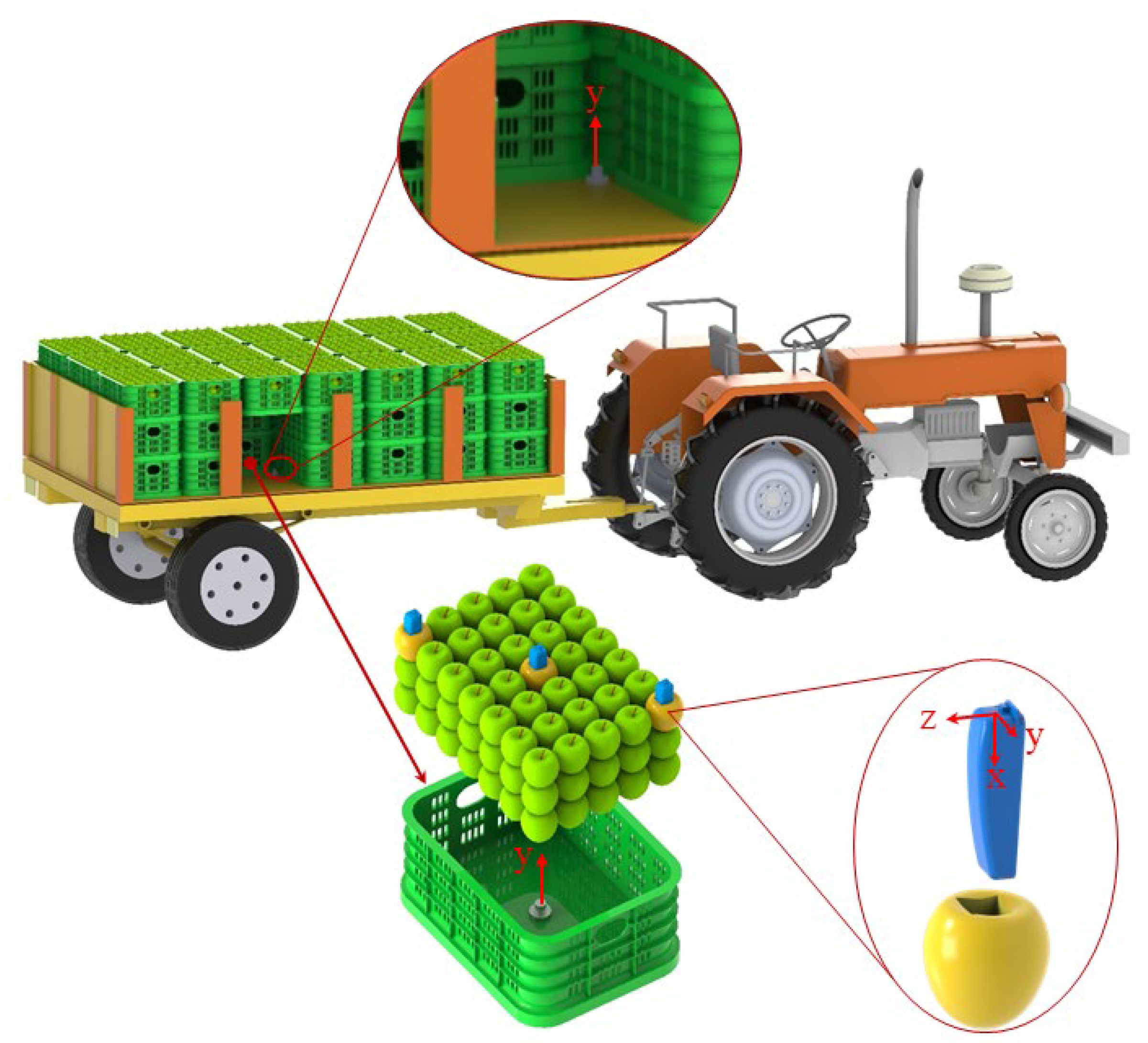

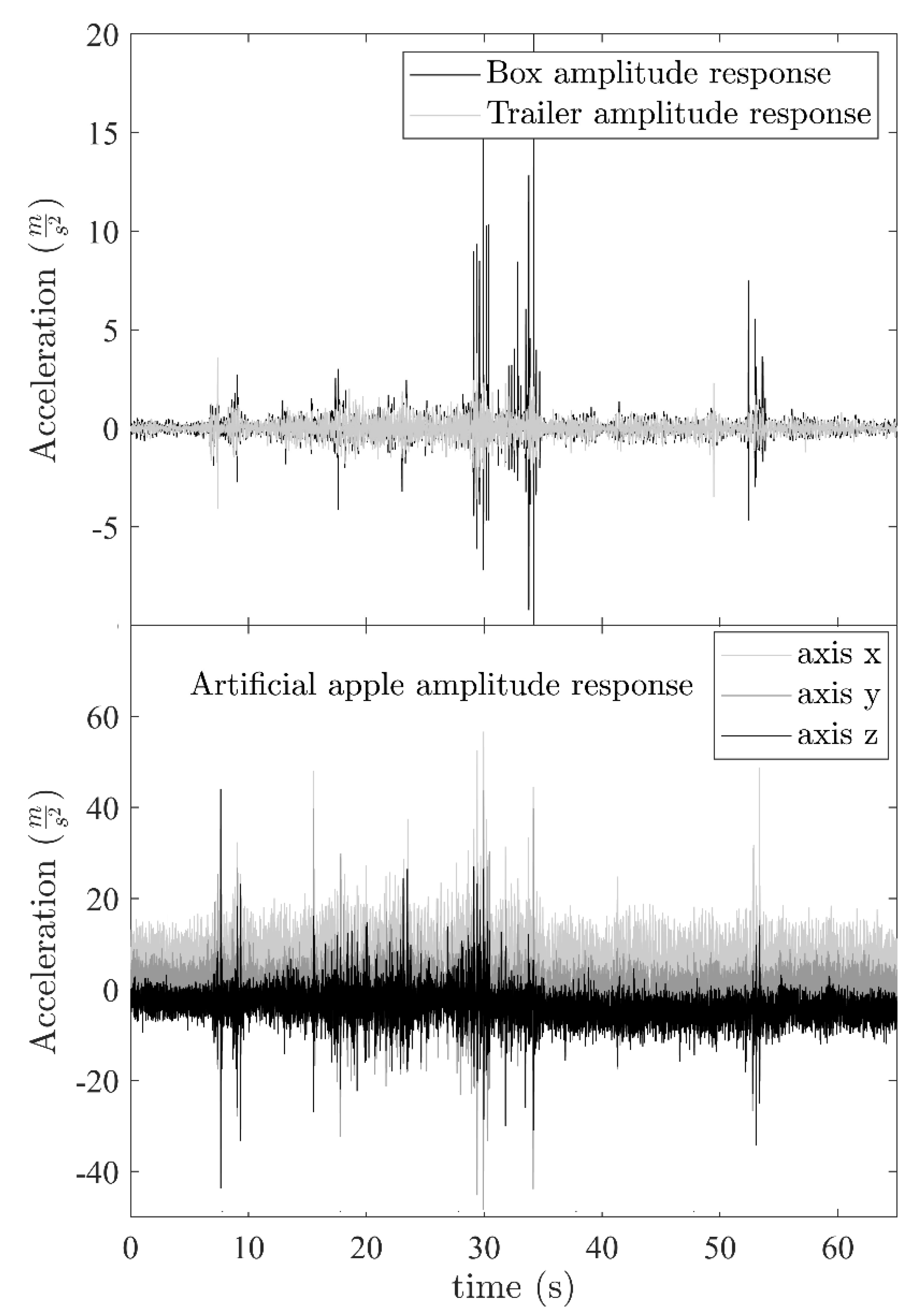

2.2. Accelerations Produced in Trailers, Boxes and Fruit in the Field

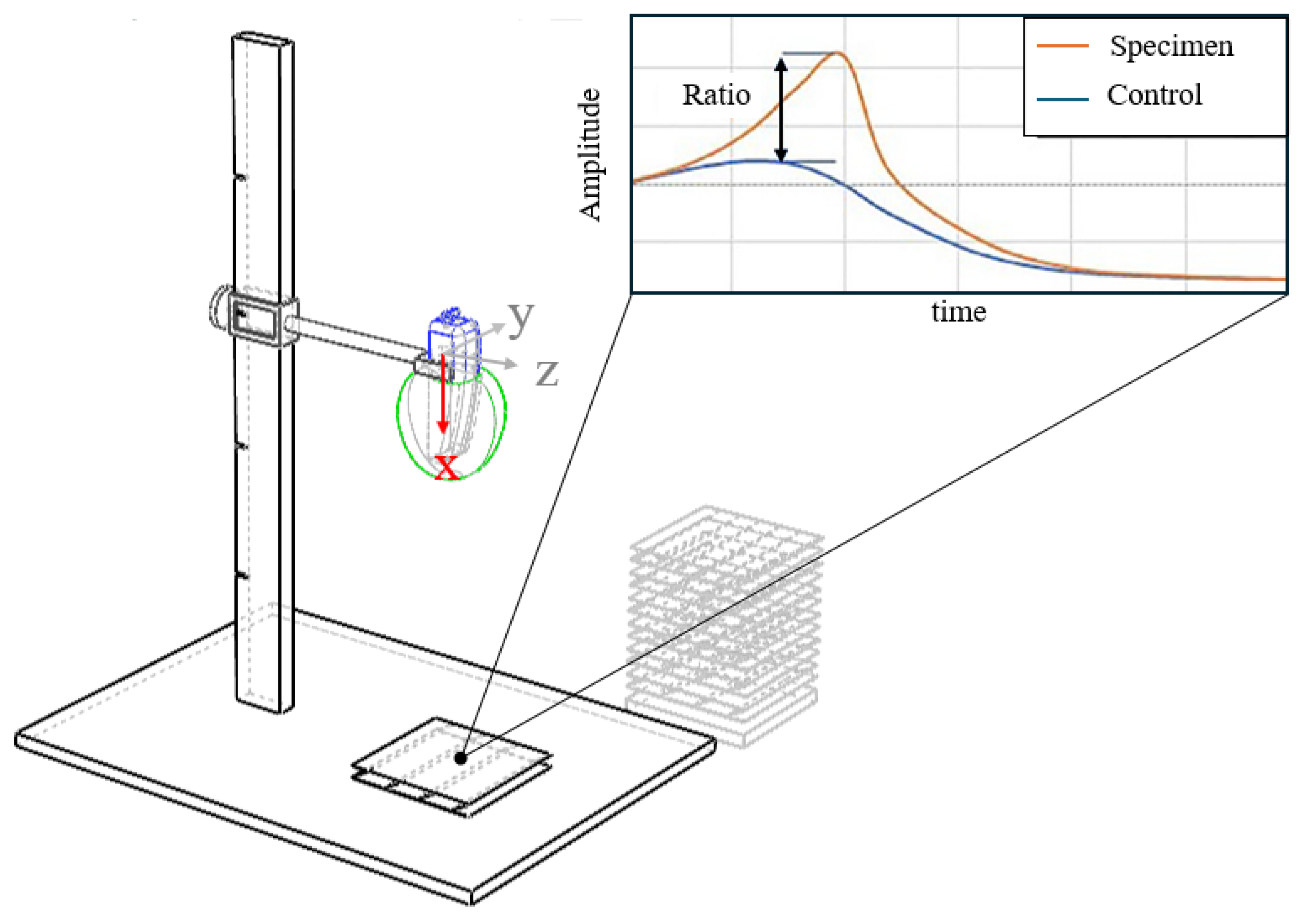

2.3. Test Specimen Impact Test

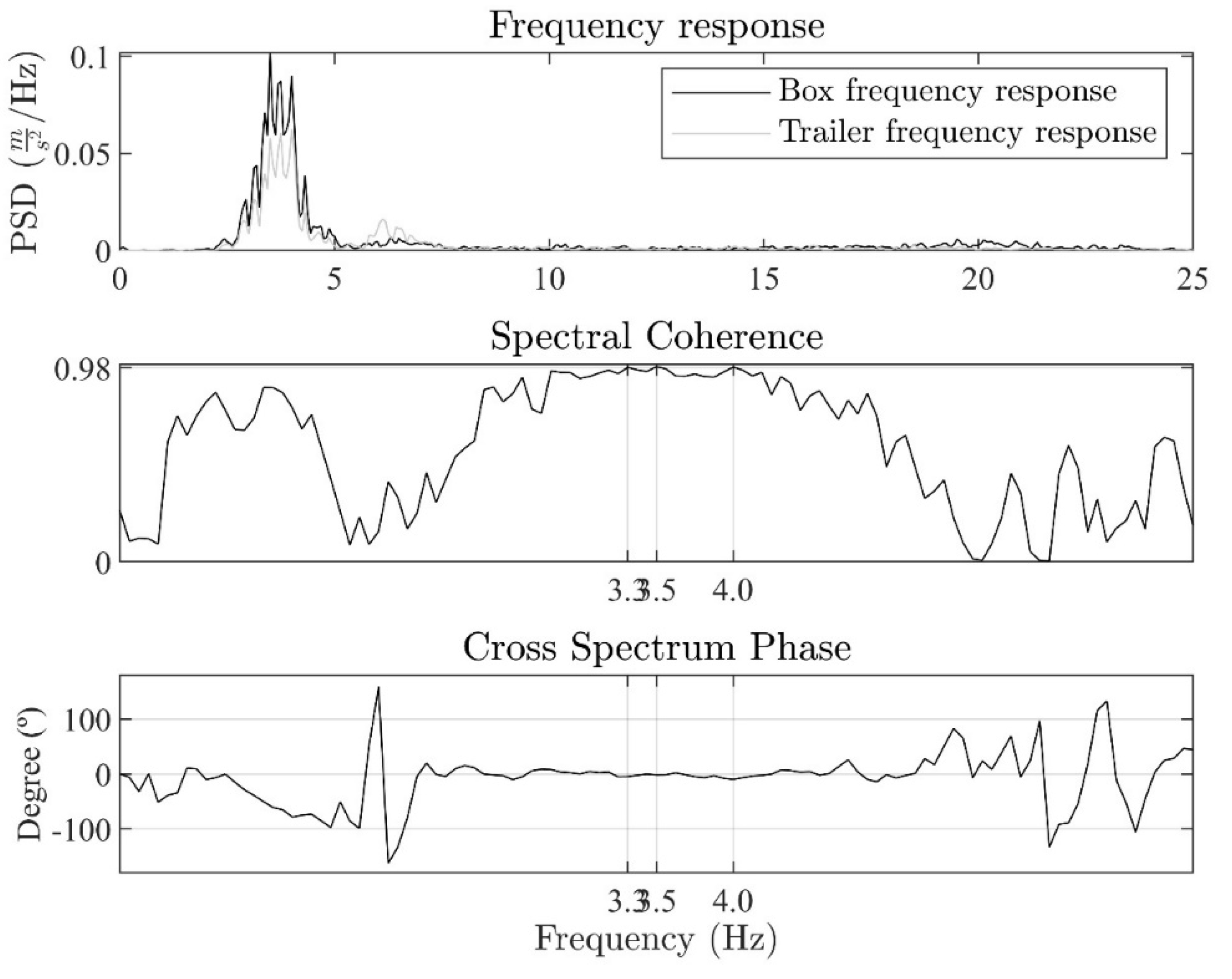

2.4. Dynamic Response Test Against a Continuous Signal

2.4.1. Artificial Sinusoidal Signal

2.4.2. Twin Traffic Signal in the Field

2.5. Statistical Analysis

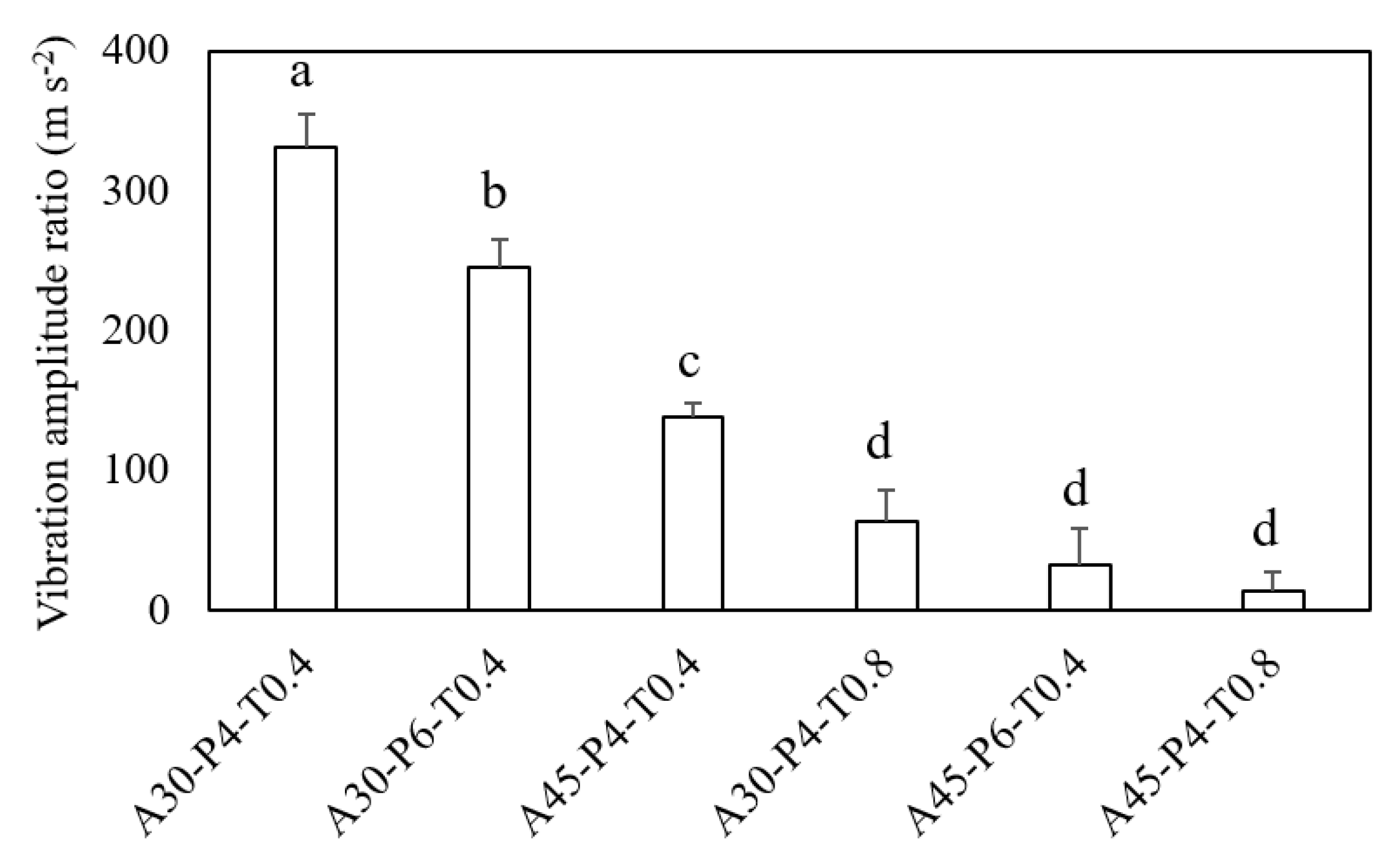

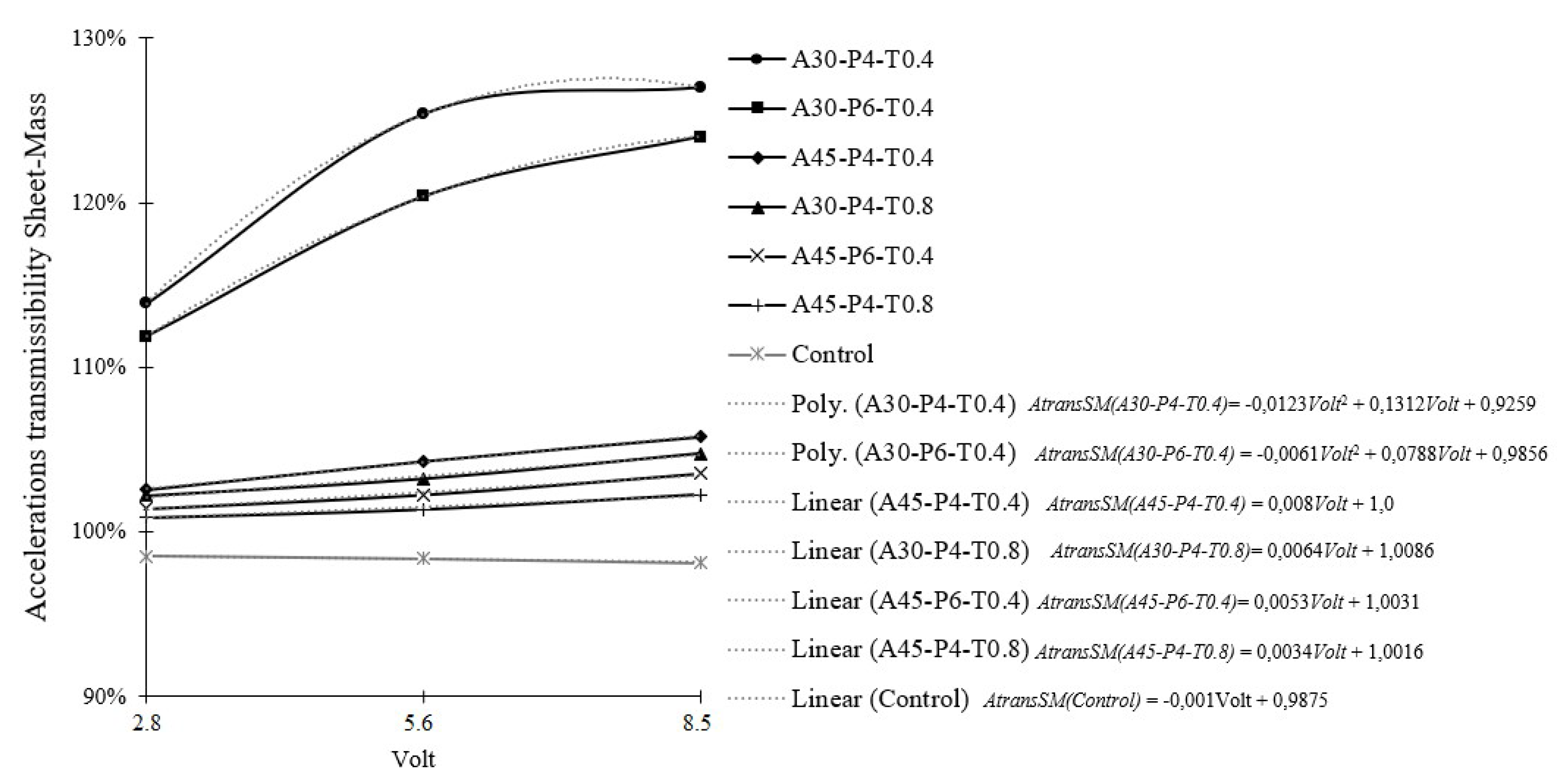

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jung, H. M et al., Effect of vibration stress on quality of packaged grapes during transportation. Engineering in Agriculture, Environment and Food. 2018, 11, 79–83. [CrossRef]

- Lu, F., Ishikawa, Y., Kitazawa, H., & Satake, T. Effect of vehicle speed on shock and vibration levels in truck transport. Packaging Technology and Science. 2018, 23, 101–109. [CrossRef]

- Xu, F., Liu, S., Liu, Y., & Wang, S. Effect of mechanical vibration on postharvest quality and volatile compounds of blueberry fruit. Food Chemistry. 2021, 349. [CrossRef]

- Walkowiak-Tomczak, D. , Idaszewska, N., Łysiak, G. P., & Bieńczak, K. The effect of mechanical vibration during transport under model conditions on the shelf-life, quality and physico-chemical parameters of four apple cultivars. Agronomy. 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Mahanti, N. K et al., Emerging non-destructive imaging techniques for fruit damage detection: Image processing and analysis. In Trends in Food Science and Technology. 2022, 120, 418–438. Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Ali, A., Xia et al., Economic and environmental consequences of postharvest loss across food supply Chain in the developing countries. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2021, 323. [CrossRef]

- Al-Dairi, M., Pathare, P. B., Al-Yahyai, R., & Opara, U. L. Mechanical damage of fresh produce in postharvest transportation: Current status and future prospects. In Trends in Food Science and Technology. 2022, 124, 195–207. Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, B., & Ahmadi, E. Evaluation and analysis of vibration during fruit transport as a function of road conditions, suspension system and travel speeds. Engineering in Agriculture, Environment and Food. 2015, 8, 26–32. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y et al., Research on damping performance of orchard fruit three-stage damping trailer based on adams. INMATEH - Agricultural Engineering. 2023, 71, 583–598. [CrossRef]

- Wasala, W. M. C. B., Dharmasena, D. A. N., Dissanayake, T. M. R., & Thilakarathne, B. M. K. S. Vibration Simulation Testing of Banana Bulk Transport Packaging Systems. In Tropical Agricultural Research. 2015, 26.

- Fernando, I., Fei, J., Stanley, R., & Rouillard, V. Evaluating packaging performance for bananas under simulated vibration. Food Packaging and Shelf Life. 2020, 23. [CrossRef]

- Peter Aba, I., Mohammed Gana, Y., Ogbonnaya, C., & O, M. O. Simulated transport damage study on fresh tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) fruits. 2012, 14. http://www.cigrjournal.org.

- Fernando, I. , Fei, J., & Stanley, R. Measurement and analysis of vibration and mechanical damage to bananas during long-distance interstate transport by multi-trailer road trains. Postharvest Biology and Technology. 2019, 158. [CrossRef]

- Dhital, R et al., Integrity of edible nano-coatings and its effects on quality of strawberries subjected to simulated in-transit vibrations. LWT. 2017, 80, 257–264. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C et al., Quasi-zero-stiffness vibration isolation: Designs, improvements and applications. In Engineering Structures. 2024, 301. Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Al Rifaie, M. , Abdulhadi, H., & Mian, A. Advances in mechanical metamaterials for vibration isolation: A review. In Advances in Mechanical Engineering. 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Augello, R. , & Carrera, E. Nonlinear dynamics and band gap evolution of thin-walled metamaterial-like structures. Journal of Sound and Vibration. 2024, 578. [CrossRef]

- Zolfagharian, A et al., 3D-Printed Programmable Mechanical Metamaterials for Vibration Isolation and Buckling Control. Sustainability (Switzerland). 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Singh, G et al., Effect of unit cell shape and structure volume fraction on the mechanical and vibration properties of 3D printed lattice structures. Journal of Thermoplastic Composite Materials. 2023, 37, 1841–1858. [CrossRef]

- Herkal, S et al., 3D printed metamaterials for damping enhancement and vibration isolation: Schwarzites. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing. 2023, 185. [CrossRef]

- Boulvert et al., Perfect, broadband, and sub-wavelength absorption with asymmetric absorbers: Realization for duct acoustics with 3D printed porous resonators. Journal of Sound and Vibration. 2022, 523. [CrossRef]

- Astrauskas, T., Grubliauskas, R., & Januševičius, T. Optimization of sound-absorbing and insulating structures with 3D printed recycled plastic and tyre rubber using the TOPSIS approach. JVC/Journal of Vibration and Control. 2024, 30, 1772–1782. [CrossRef]

- Cai, C et al., Design and numerical validation of quasi-zero-stiffness metamaterials for very low-frequency band gaps. Composite Structures 2020, 236. [CrossRef]

- Cai, C. , Zhou, J., Wang, K., Xu, D., & Wen, G. Metamaterial plate with compliant quasi-zero-stiffness resonators for ultra-low-frequency band gap. Journal of Sound and Vibration. 2022, 540. [CrossRef]

- Dalela, S et al., Nonlinear static and dynamic response of a metastructure exhibiting quasi-zero-stiffness characteristics for vibration control: an experimental validation. Scientific Reports. 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Hamzehei, R. , Bodaghi, M., & Wu, N. Mastering the art of designing mechanical metamaterials with quasi-zero stiffness for passive vibration isolation: a review. In Smart Materials and Structures. 2024, 33. Institute of Physics. [CrossRef]

- Abejón, R.; et al. , When plastic packaging should be preferred: Life cycle analysis of packages for fruit and vegetable distribution in the Spanish peninsular market. Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 2020, 155. [CrossRef]

- Hamzehei, R. , Zolfagharian, A., Dariushi, S., & Bodaghi, M. 3D-printed bio-inspired zero Poisson’s ratio graded metamaterials with high energy absorption performance. Smart Materials and Structures. 2022, 31. [CrossRef]

- Hamzehei, R. et al., Parrot Beak-Inspired Metamaterials with Friction and Interlocking Mechanisms 3D/4D Printed in Micro and Macro Scales for Supreme Energy Absorption/Dissipation. Advanced Engineering Materials. 2023, 25. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. , Tawfick, S. H., & King, W. P. Modeling and Design of Zero-Stiffness Elastomer Springs Using Machine Learning. Advanced Intelligent Systems. 2022, 4. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L., Sun, X., Cheng, L., & Yu, X. A 3D-printed quasi-zero-stiffness isolator for low-frequency vibration isolation: Modelling and experiments. Journal of Sound and Vibration. 2024, 577. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez C., K. L., Lagos C., R. F., & Aizpun, M. Investigating the influence of infill percentage on the mechanical properties of fused deposition modelled ABS parts. Ingenieria e Investigacion. 2016, 36, 110–116. [CrossRef]

- Dizon, J. R. C. , Espera, A. H., Chen, Q., & Advincula, R. C. Mechanical characterization of 3D-printed polymers. In Additive Manufacturing. 2018, 20, 44–67. Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Jiménez, F et al., Table olive cultivar susceptibility to impact bruising. Postharvest Biology and Technology. 2013, 86, 100–106. [CrossRef]

- Wu et al., Design of semi-active dry friction dampers for steady-state vibration: sensitivity analysis and experimental studies. Journal of Sound and Vibration. 2019, 459. [CrossRef]

- Zheng et al., Analytical study of a quasi-zero stiffness coupling using a torsion magnetic spring with negative stiffness. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing. 2018, 100, 135–151. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y. , Li, F., & Wang, Y. A nonlinear quasi-zero-stiffness vibration isolation system with additional X-shaped structure: Theory and experiment. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing. 2022, 177. [CrossRef]

- Gatti, G. An adjustable device to adaptively realise diverse nonlinear force-displacement characteristics. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing. 2022, 180. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y. , Shangguan, W. Bin, Yin, Z., & Liu, X. A. Design and modeling of a quasi-zero stiffness isolator for different loads. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing. 2023, 188. [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y., & Li, Q. M. Evaluation of the mechanical shock testing standards for electric vehicle batteries. International Journal of Impact Engineering. 2024, 194. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R et al., Reduction in Hami melon (Cucumis melo var. saccharinus) softening caused by transport vibration by using hot water and shellac coating. Postharvest Biology and Technology. 2015, 110, 214–223. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., & Thomas, C. Quantitative evaluation of mechanical damage to fresh fruits. In Trends in Food Science and Technology. 2014, 35, 138–150. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D et al., A simple and fast guideline for generating enhanced/squared envelope spectra from spectral coherence for bearing fault diagnosis. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing. 2019, 122, 754–768. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P., Wen, H., Liu, X., & Niu, L. A new time-delay estimation: phase difference-reassigned transform. International Journal of Dynamics and Control. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y et al., Targeted energy transfer of a parallel nonlinear energy sink. Applied Mathematics and Mechanics. 2019, 40, 621–630. [CrossRef]

- Elmadih, W. , Syam, W. P., Maskery, I., Chronopoulos, D., & Leach, R. Multidimensional phononic bandgaps in three-dimensional lattices for additive manufacturing. Materials. 2019, 12. [CrossRef]

- Fernando, I et al., Developing an accelerated vibration simulation test for packaged bananas. Postharvest Biology and Technology. 2021, 173. [CrossRef]

- Yu, M et al., A self-sensing soft pneumatic actuator with closed-Loop control for haptic feedback wearable devices. Materials and Design. 2023, 223. [CrossRef]

- Paternoster, A., Vanlanduit, S., Springael, J., & Braet, J. Vibration and shock analysis of specific events during truck and train transport of food products. Food Packaging and Shelf Life. 2018, 15, 95–104. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A., Ramini, A., & Towfighian, S. Experimental and theoretical investigation of an impact vibration harvester with triboelectric transduction. Journal of Sound and Vibration. 2018, 416, 111–124. [CrossRef]

| Gain (V) | ARMS base (ms-2) | ATRANS base-mass (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 2.8 | 0.228(0.022) a | 98.54(0.010) a |

| 5.6 | 0.481(0.002) a | 98.38(0.050) a | |

| 8.5 | 0.697(0.009) a | 98.13(0.030) a | |

| A45-P4-T0.8 | 2.8 | 0.243(0.001) a | 100.90(0.110) b |

| 5.6 | 0.508(0.001) a | 101.38(0.001) b | |

| 8.5 | 0.711(0.003) a | 102.25(0.010) b | |

| A45-P6-T0.4 | 2.8 | 0.253(0.004) a | 101.44(0.060) bc |

| 5.6 | 0.505(0.002) a | 102.27(0.130) bc | |

| 8.5 | 0.717(0.009) a | 103.55(0.250) bc | |

| A30-P4-T0.8 | 2.8 | 0.243(0.002) a | 102.22(0.030) cd |

| 5.6 | 0.493(0.009) a | 103.24(0.220) cd | |

| 8.5 | 0.691(0.002) a | 104.78(0.020) cd | |

| A45-P4-T0.4 | 2.8 | 0.255(0.008) a | 102.56(0.050) d |

| 5.6 | 0.500(0.001) a | 104.30(0.140) d | |

| 8.5 | 0.701(0.004) a | 105.78(0.070) d | |

| A30-P6-T0.4 | 2.8 | 0.251(0.006) a | 111.90(0.280) e |

| 5.6 | 0.490(0.001) a | 120.39(0.30) e | |

| 8.5 | 0.676(0.002) a | 124.02(0.003) e | |

| A30-P4-T0.4 | 2.8 | 0.239(0.007) a | 113.91(0.430) f |

| 5.6 | 0.494(0.003) a | 125.38(0.040) f | |

| 8.5 | 0.696(0.007) a | 126.99(0.030) f |

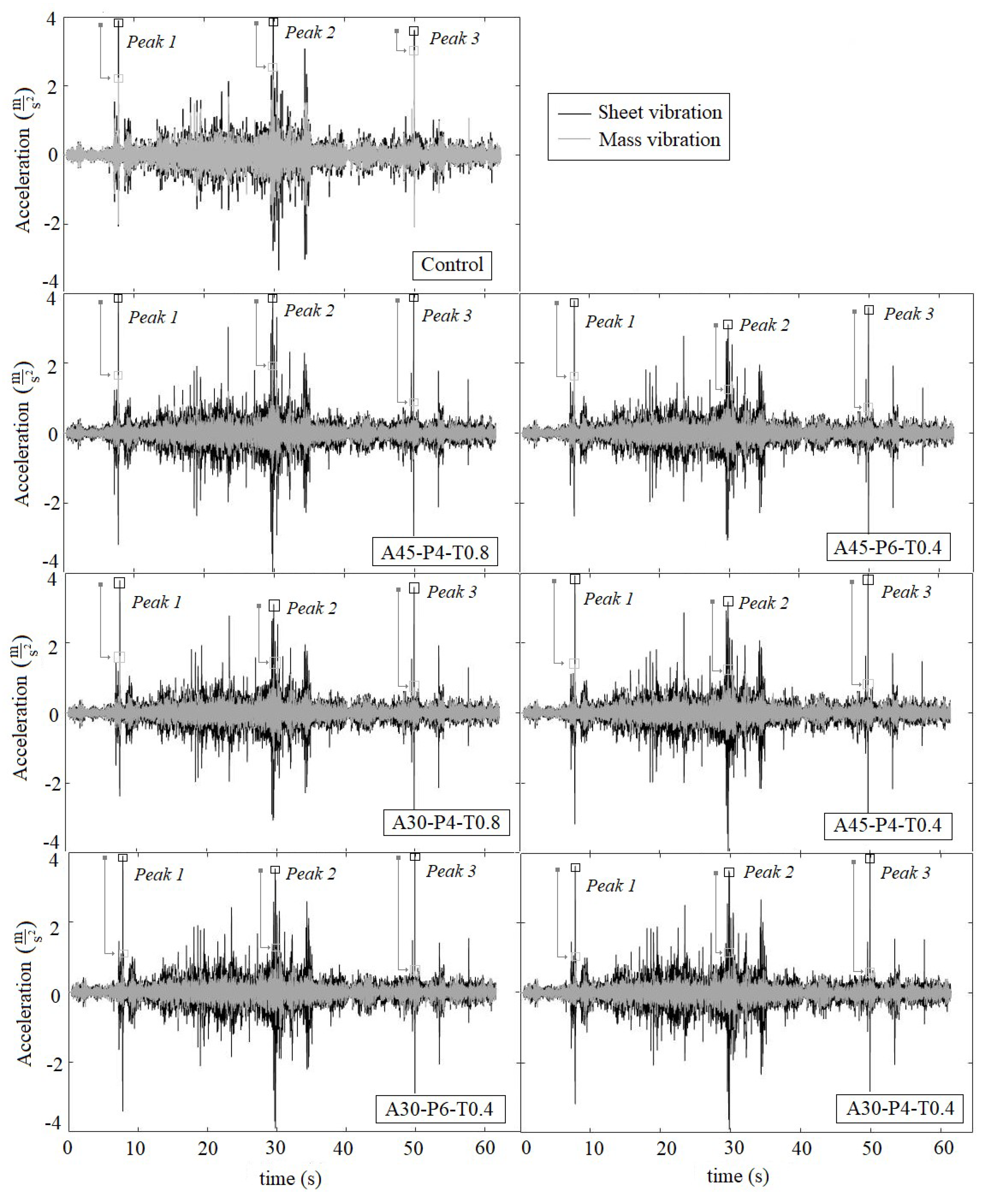

| Peak 1 | Peak 2 | Peak 3 | ||||

| ARMS (ms-2) | ATRANS base-masa (%) * | ARMS (ms-2) | ATRANS base-masa (%) * | ARMS (ms-2) | ATRANS base-masa (%) * | |

| Control | 3.897(0.187) | 57.40(1.210) a | 3.949(0.058) | 63.69(0.630) a | 3.619(0.024) | 83.70(0.160) a |

| A45-P4-T0.8 | 4.167(0.033) | 41.47(2.77) b | 4.179(0.057) | 47.40(0.330) b | 4.01(0.056) | 22.96(0.590) b |

| A45-P6-T0.4 | 3.791(0.001) | 43.08(0.130) bc | 3.119(0.016) | 44.41(0.160) c | 3.598(0.000) | 20.38(0.030) c |

| A30-P4-T0.8 | 3.922(0.031) | 37.00(0.33) cd | 3.484(0.003) | 42.45(0.080) d | 4.031(0.002) | 22.34(0.360) b |

| A45-P4-T0.4 | 3.903(0.036) | 35.93(0.490) d | 3.07(0.042) | 40.78(0.380) e | 3.867(0.010) | 20.62(0.030) c |

| A30-P6-T0.4 | 3.868(0.041) | 19.13(0.090) e | 3.529(0.002) | 34.67(0.140) f | 4.099(0.015) | 14.36(0.600) d |

| A30-P4-T0.4 | 3.709(0.028) | 19.68(0.140) e | 3.523(0.012) | 33.36(0.140) g | 4.071(0.001) | 13.27(0.020) d |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).