1. Introduction

Semi-arid natural grasslands are distributed from central Mexico to the southern United States of America, in the Chihuahuan desert region [

1] (Huenneke et al., 2001). The grasslands are mainly covered by various species of grasses and some shrubs in low density [

2] (Rzedowski, 2021). In recent years, grasslands have faced multiple threats, such as the alteration of natural fire cycles, the increase in CO

2, conversion to agriculture, overuse by extensive livestock, the introduction of exotic grasses, and the increase in herbaceous and less desirable shrubs [

3] (Barger et al., 2011). The presence of shrubs in the pastures is a normal state; however, these factors have triggered colonization processes of the native shrub and semi-shrub species, causing the displacement of grasses species and the consequent changes in species diversity, availability of forage for cattle, alteration in the cycle of nutrients, etc. [

4] (Van Auken, 2000).

The woody species that are increasing their density in the Mexican central highlands are those of the genera

Vachellia,

Prosopis,

Opuntia,

Larrea,

Brickellia and

Isocoma. The increase in the density of shrub species has shown to reduce the availability of soil water for the dominant plant species [

5] (Caldeira et al., 2015). In addition, these species have a high capacity for adaptation to degraded areas [

6] (Kidron, 2013). It has been reported that the reduction of herbivores is a driver of the increase of shrubs [

7] (Mata-González et al., 2007) and that excessive grazing has the same adverse effects; mainly due to the reduction in the amount of biomass (fuel) available to propitiate a natural fire with sufficient intensity to affect shrub species [

8] (Munson et al., 2013). Therefore, the balance of herbaceous-woody species must be analyzed in the context of interactions of cattle grazing with other factors such as climate, topography, fire frequency, nurse plants, soil type, among others [

9] (Sepp et al., 2021).

The colonization of shrubs is a process that is difficult to reverse. The decrease in the intensity of grazing does not necessarily reduce or even reverse the colonization of shrubs, but it is necessary to invest in different techniques that range from the application of mechanical, chemical, pyric, and sometimes also biological treatments [

10] (Ibarra et al., 2014). On the other hand, fire, which naturally limited the growth and development of shrubs and shrub species centuries ago [

11] (Osborn et al., 2002), has decreased in frequency and in many cases has been completely eradicated due to the reduction of above ground biomass or fuel in grassland ecosystems. Historically, grasslands have been subjected to periods of fire, which has led them to adapt and maintain themselves as fire-dependent species since their meristems are close to the ground surface and are less susceptible to fire [

12] (Rego et al., 2021). When the natural fire frequency was modified, the shrub species increased their growth and density, becoming an ecological and economic problem in the region and displacing key species in the pastures [

13] (Wright and Bayley, 1982). In this sense, prescribed burning programs have recently been applied in grassland ecosystems in order to eliminate shrub species and recover ecosystem productivity. However, some studies report that fire frequency every 3 to 4 years do not guarantee the control of the expansion of woody plants [

14] (Nippert et al., 2021), since the intensity of regularly prescribed fires is less than natural fires in non-fragmented landscapes. By increasing fire intensity and frequency, short- and long-term post-fire soil responses could be improved, which favors a prompt restoration of natural pastures [

15] (Hahn et al., 2021).

Shrub colonization in grassland ecosystems occurs gradually at first, until a point is reached where woody species spread rapidly [

16] (Ratajczak et al., 2014). Once woody species reach considerable size and density, the resilience of grasslands deteriorates, resulting in a rapid increase in the abundance of woody plants [

17] (Ratajczak et al., 2017). Taking into account that fire (prescribed burning) can be used as a tool to reverse the colonization and prevent the recruitment of new shrub seedlings, and that its effectiveness depends on the intensity to achieve greater mortality of woody plants, the objective of this study was to evaluate the effect of fire (by prescribed burnings) on shrub species in different growth stages in the Llanos de Ojuelos, Jalisco, as well as identify the main dasometric variables that influence the degree of fire damage caused by fire.

2. Materials and Methods

The Materials and Methods should be described with sufficient details to allow others to replicate and build on the published results. Please note that the publication of your manuscript implicates that you must make all materials, data, computer code, and protocols associated with the publication available to readers. Please disclose at the submission stage any restrictions on the availability of materials or information. New methods and protocols should be described in detail while well-established methods can be briefly described and appropriately cited.

2.1. Study Area

The study area is located in the arid and semi-arid region of the Central Plateau of Mexico, at the south of the Chihuahuan desert, in Santo Domingo ranch. Is an area dedicated to livestock production for 36 years. The production system is cattle, with grazing intensities ranging between 3 and 7 ha per animal unit and a forage consumption of less than 40% of the available aerial biomass. The study area is managed in a rotational grazing system with 8 paddocks of 60 ha.

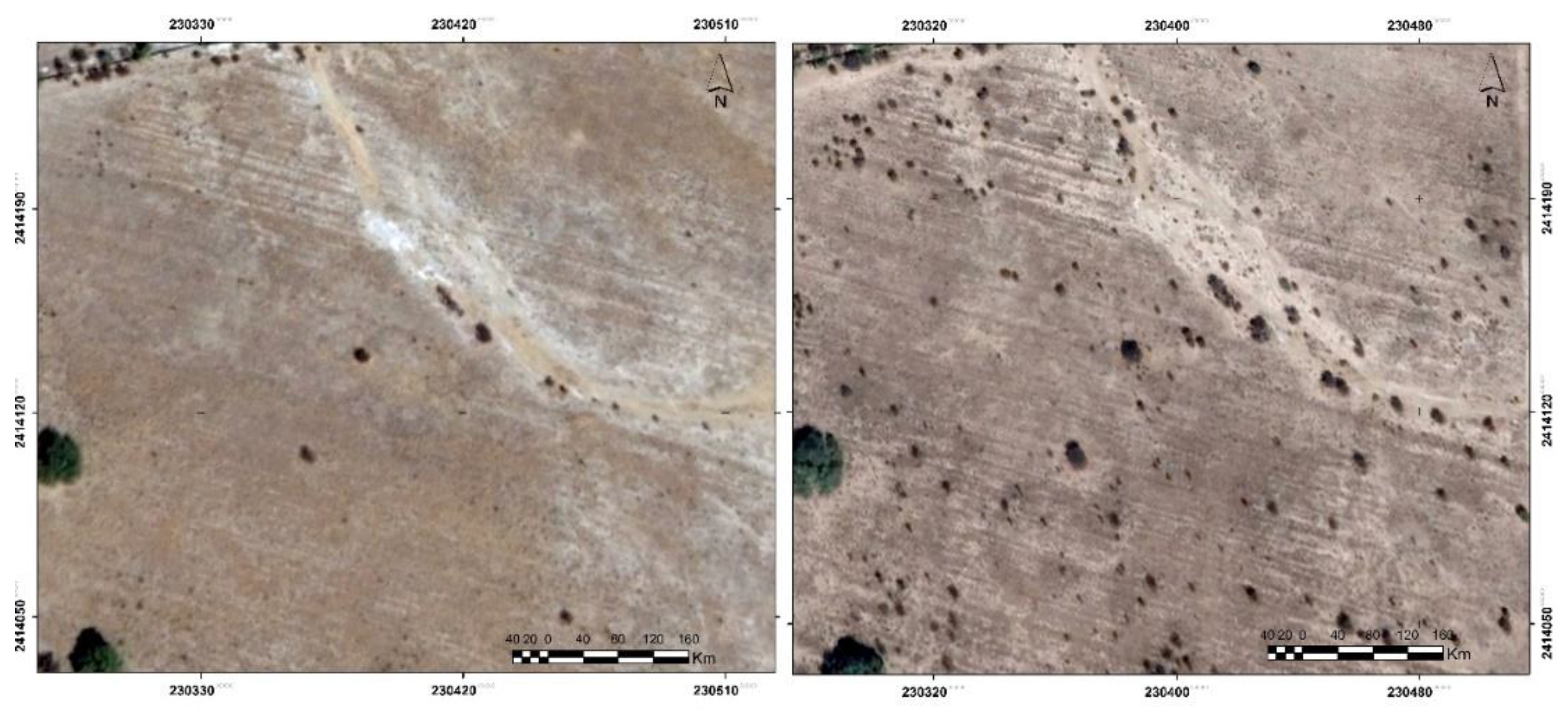

Figure 1.

Changes in shrub abundance into the experimental site. Images correspond to years 2011 (left) and 2022 (right; Google, s.f.).

Figure 1.

Changes in shrub abundance into the experimental site. Images correspond to years 2011 (left) and 2022 (right; Google, s.f.).

2.2. Vegetation Cover

The predominant vegetation type in the Llanos de Ojuelos consists of scrub and grasslands. The grasslands are mainly composed of blue grama grass (Bouteloua gracilis), wolfstail (Lycurus phleoides), scorpion grama (Bouteloua scorpioides), three-bearded grass (Aristida divaricata), buffalo grass (Bouteloua dactyloides), silvery strawweed (Bothriochloa barbinodis), zacatón (Muhlenbergia rigida), and hairy grama (Bouteloua hirsuta). These grasslands are interspersed with shrubs such as huizache (Vachellia schaffneri), cat's claw (Mimosa biuncifera), and mesquite (Prosopis leaviagata), which, while native to scrublands, are considered invasive. The herbaceous vegetation includes species like foxtail (Brickellia spinulosa), sawtooth candyleaf (Stevia serrata), toad grass (Eryngium carlinae F. Delaroche), and trompillo (Solanum elaeagnifolium), among others.

2.3. Climate

The climate of the study area is characterized as dry and semi-dry, with precipitation levels consistently lower than potential evapotranspiration. Rainfall is highly variable, ranging between 300 and 500 mm annually, with a mean annual precipitation of 424 mm. Precipitation typically occurs from June to September. The average annual temperature varies between 16 and 18 °C. The soils are shallow, less than 50 cm deep, with minimal organic matter and a cemented layer (caliche, tepetate). Dominant soil types include durisols and phaeozem [

18,

19] (INEGI, 2007; WRB, 2014).

2.4. History and Grazing Management

The study site is a paddock planted with weeping lovegrass (Eragrostis curvula). Rainfed agriculture was practiced here until the early 1980s, after which the land was abandoned. For the past 15 years prior to burning, the pasture was primarily used for producing weeping lovegrass seed, with minimal cattle grazing. The production system on the Santo Domingo Ranch involves cattle grazing with intensities ranging from 3 to 7 hectares per animal unit and a forage consumption rate of less than 40% of the available aerial biomass. The area is managed using a rotational grazing system with 8 paddocks of 60 hectares each.

2.5. Experimental Design

To evaluate the effect of prescribed burning in grasslands invaded by Vachellia schaffneri and Mimosa biuncifera, four different sites were selected for the study. At Sites 1 and 3, four plots of 20 x 100 meters (2000 m²) each were established, while at Sites 2 and 4, three plots of the same dimensions were set up. Prescribed burns were applied to the plots at these sites. To prevent the spread of fire to neighboring areas, the plots were delimited with mineral lines and black lines. All plots had approximately 20% shrub cover with varying heights. Measurements of all shrubs within the plots were taken before the burn and three months afterward. Data collected included diameter at 30 cm above ground (base diameter), total height, crown height, crown diameter, number of branches, and the shrub’s condition (alive or dead). Additionally, the presence of regrowth and the percentage of damage, such as black burn marks on dead stems or the absence of aerial biomass, were recorded.

Each individual shrub was marked with a metal plate containing the plot number and the shrub number. It was assumed that individuals not located, or whose identification plates were missing, were consumed by the fire after the prescribed burn.

2.6. Vegetation Sampling

Aboveground biomass and species diversity were assessed using 1 m² plots, with a total of 20 plots sampled. To measure aboveground biomass, herbaceous vegetation was clipped, dried, and then weighed. The biomass was separated into two categories: living biomass, representing current year growth, and dead biomass, consisting of residual plant material from the previous year. Additionally, the percentage of grasses and herbaceous plants present in the plots was identified and quantified, providing a detailed assessment of plant composition.

Species diversity was evaluated by recording the number of species present in each plot, allowing for the calculation of diversity indices. These data were collected after the prescribed burn treatments. To compare the available biomass before the burn treatment, contiguous plots were sampled prior to the prescribed burn, which allowed for the assessment of pre-existing biomass in the area.

2.7. Application of Prescribed Burns

The prescribed burns were conducted on different dates to effectively control and manage the fire, minimizing risks and ensuring that the most favorable weather conditions were selected. The first prescribed burn was conducted on March 29, 2021, over an area of 10 hectares with a slope of less than 3%. A head-fire burn was applied with a fuel load of 11,160 t/ha, relative humidity exceeding 30%, and wind speeds below 10 km/h from the south-southeast. The second prescribed burn was performed on April 26, 2021, in another 10-hectare area. This burn had a fuel load of 12,220 t/ha, with relative humidity again exceeding 30% and wind speeds under 7 km/h from the south. The higher fuel load resulted in flame heights reaching approximately 10 meters.

The third prescribed burn was executed on April 19, 2022, over an area of 9 hectares. This site had grass cover and biomass accumulation similar to the previous sites. The recorded environmental conditions included a relative humidity of 69%, wind speeds of 3.7 km/h, and a temperature of 54°F (12°C). The fourth prescribed burn was conducted on April 22, 2022, over an area of 10 hectares with measurements showing a relative humidity of 47%, a temperature of 60°F (16°C), and wind speeds of 9 km/h.

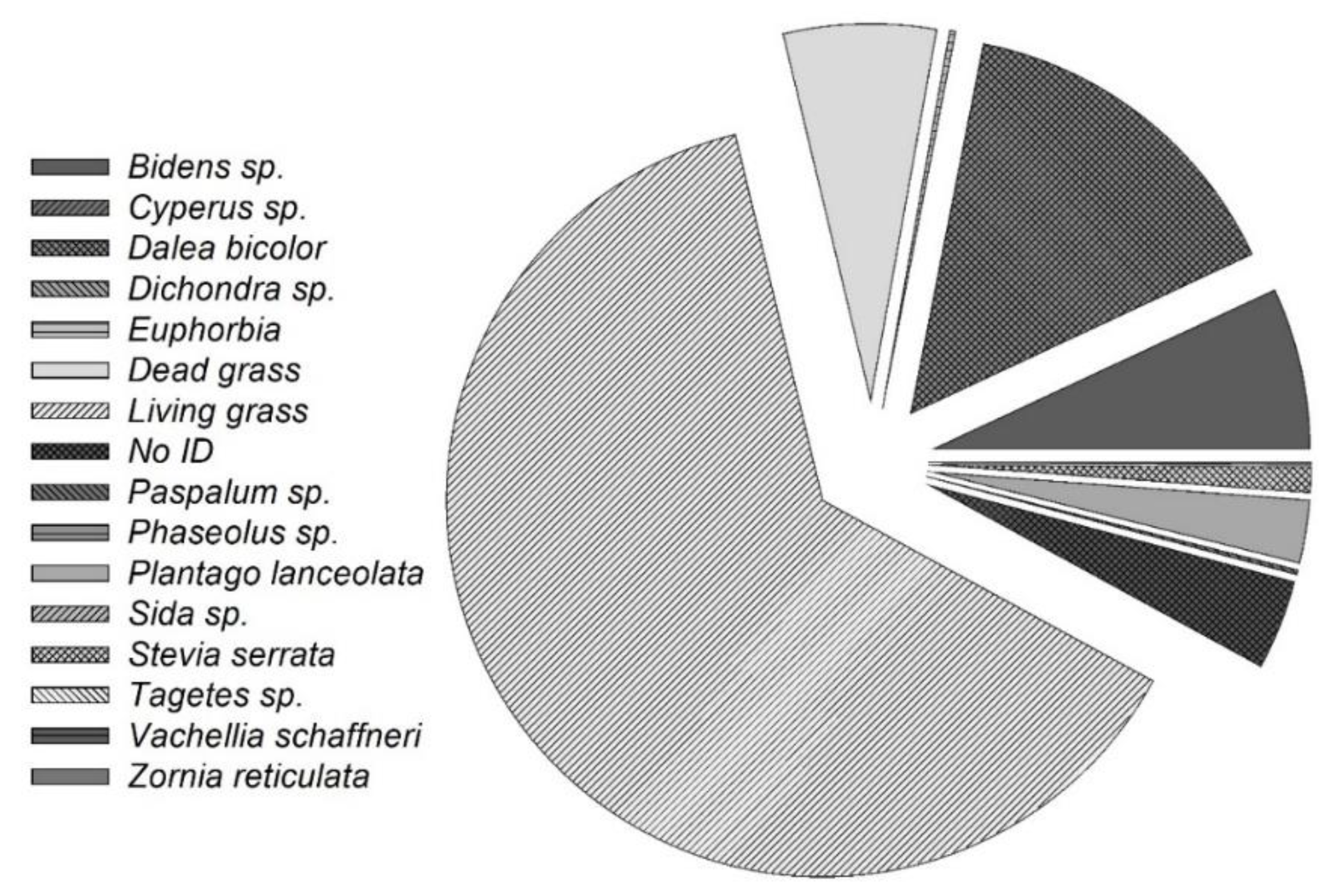

Figure 2.

Aereal view of one of the four sites before (left) and after (right) the burning treatment. The black contour in the left image is the protection line which was made one week before the prescribed burning.

Figure 2.

Aereal view of one of the four sites before (left) and after (right) the burning treatment. The black contour in the left image is the protection line which was made one week before the prescribed burning.

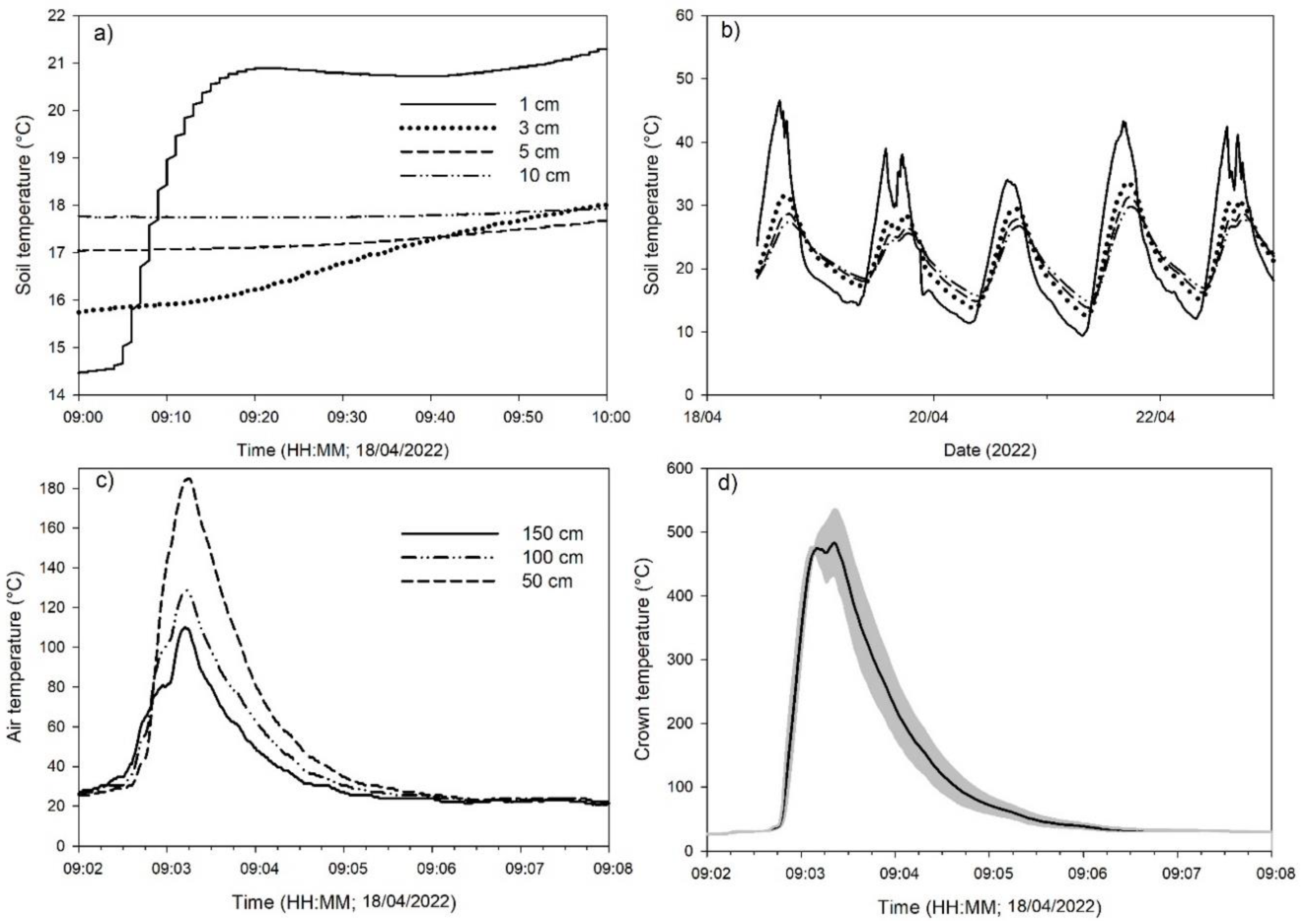

2.8. Environmental Variables

Environmental variables were recorded to characterize aboveground and soil temperatures during the prescribed burn at site 4. This site had grass cover and biomass accumulation similar to the other treatment sites. Soil temperature was measured every second using four temperature sensors (TMC20-HD, Onset, Bourne, MA) connected to a data logger (U12-006, Onset, Bourne, MA). The sensors were placed at depths of 1, 3, 5, and 10 cm in the soil. Air temperature was monitored using three type K thermocouples positioned at heights of 50, 100, and 150 cm above the ground, while an additional three thermocouples were placed directly over tussocks to monitor air temperature at the crown level.

2.9. Analysis of Data

Species composition was evaluated by measuring the proportion of dry biomass of each species within the cutting plots. For shrub composition, we quantified the number of individual shrubs per species in the fire plots to assess changes in species abundance and diversity due to the burns.

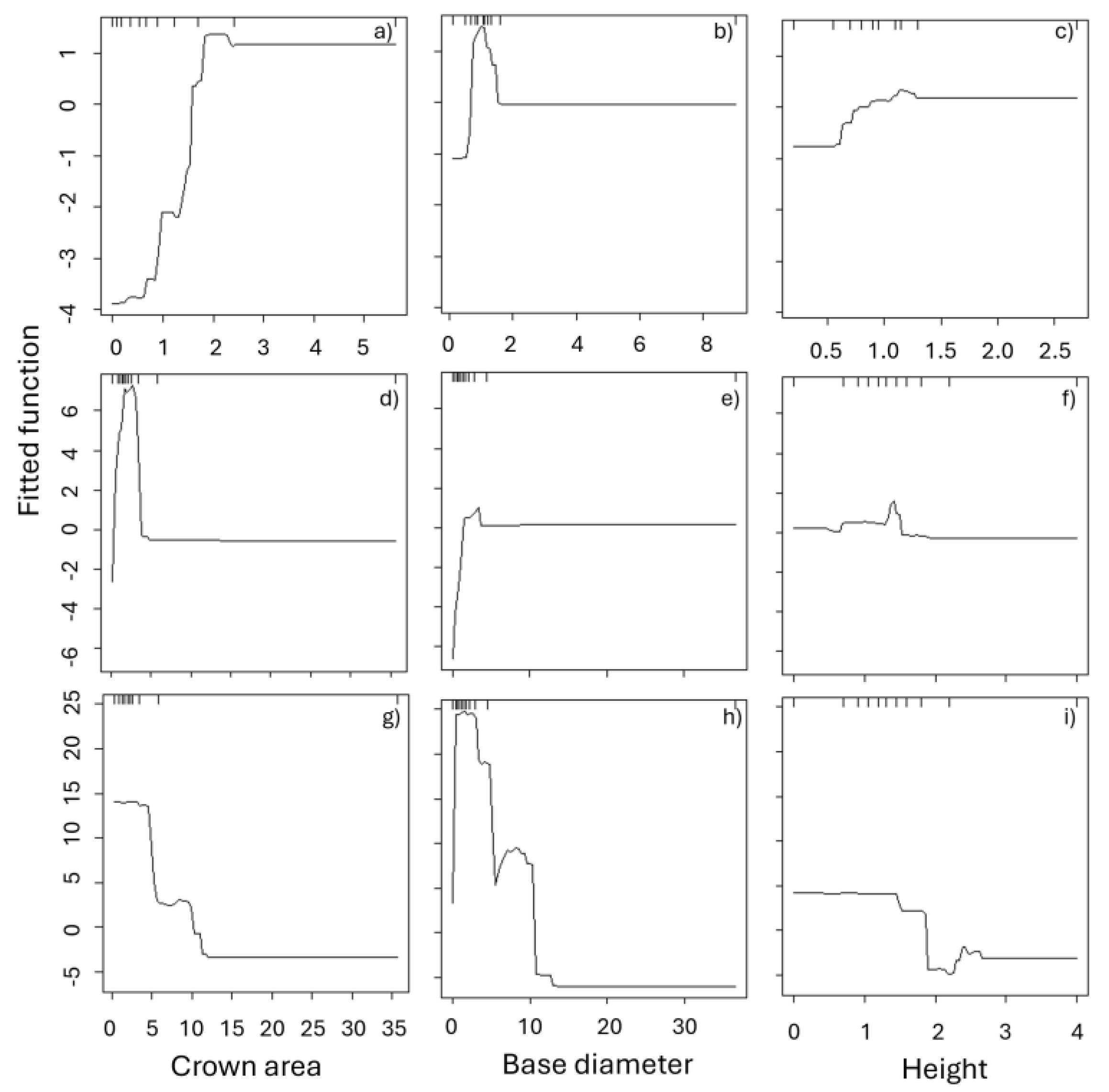

To determine the variables that most significantly affected shrub species and to identify the thresholds for vegetation response to fire, we employed boosted regression trees (BRTs). This analytical method helps to uncover complex relationships between environmental variables and vegetation response. The "GBM" (Generalized Boosted Regression Models) library in R software [

20] (R Core Team, 2020) was used for this analysis. BRTs were particularly useful for handling nonlinear and interactive effects of multiple variables on shrub response, providing insights into how different factors such as fire dasometric variables influence fire damage and shrub recovery and survival.

By using BRTs, we aimed to capture the most influential factors affecting shrub species and to identify critical thresholds for vegetation resilience to fire. This approach allows for a more nuanced understanding of fire’s impacts on different shrub species.

4. Discussion

Our results showed that the burning affected 97% (

Vachellia) and 100% (

Mimosa) of the shrubs; however, on average, 85% of the affected shrubs recovered after the first rains. The taller individuals with larger base diameters and with wide crowns did not suffer any effects from the burning. This indicates that as height and crown width increase, fire causes little or no damage to the shrubs. This quick recovery and low fire damage to large shrubs are likely explained by thicker bark at the base of the shrubs, lower grass biomass (fuel) at the base, and taller growth structures that lessen the effect of fire on adult plants. It also suggests that shrubs become less vulnerable to the effects of fire as they grow [

21] (Archer et al., 2017). A larger crown area reduces grass cover due to shading just below the shrub crown, which lowers fire intensity by decreasing the availability of fuel. On the other hand, greater height allows the growth structures to escape from the fire [

22,

23] (Ludwig et al., 2001; Harrington and Kathol, 2009). This indicates that fire causes total damage to low-growing shrubs with small crowns.

Available biomass is a factor to consider during burning. In our plots, there was an average biomass of 12 tons per hectare, and although the fire reached flame heights of around 10 meters, its duration in certain areas was only a few seconds due to the speed of the fire’s movement (

Figure 3). Our results showed that a single burn reduces shrub cover by 15%, primarily affecting young plants while having minimal impact on other herbaceous species that are senescent or found in the soil seed bank. One year after the burn, net primary productivity recovered 100%, and other studies in semi-arid grasslands suggest that full biomass recovery after burning takes about 3-5 years [

24,

25] (Bennett et al., 2003; Wells et al., 2021). Our study site is not the typical grassland in Mexico; overgrazing by cattle maintain very low standing biomass levels (<1 t ha

-1), which prevents of severe wildfires, but that could not represent a threat for shrub survival.

In the early stage of shrub colonization, grasses can suppress shrub dominance through competition for near-surface soil resources, slowing shrub growth. However, when grasses are inactive, shrubs use these resources to accelerate growth [

26] (Holdo and Brocato, 2015). In the later stages of the transition from grassland to shrubland, shrub-shrub competition does not slow the expansion rate of shrubs [

27] (Pierce et al., 2019). An adult-stage shrub can reach heights of 3 to 4 meters and develop better roots, allowing for greater nutrient reserves [

28] (Bond and Midgley, 2003), which could translate into greater fire resistance and the ability to regrow even after 100% damage. Woody plants benefit from disturbance regimes as they are capable of resprouting, though these sprouts tend to produce fewer seeds than older branches [

28,

29] (Bond and Midgley, 2003; Li et al., 2022). This has implications for management and conservation programs that use fire to control shrubs.

Our results reveal that the diameter at 30 cm is an important factor for lowering fire damage and for favoring resprouting. This finding can be explained by several ecological and morphological factors. First, the diameter at 30 cm from the ground serves as an indicator of the shrub’s age and vigor. Shrubs with a larger diameter, which are typically older and more vigorous, have a greater capacity to generate biomass and support a more extensive branching structure [

29] (Bond and Midgley, 2003). This is because a larger diameter provides a more robust base capable of supporting a greater number of branches. On the other hand, the crown area is closely related to the shrub's photosynthetic capacity, which influences branch formation. A shrub with a larger crown can capture more sunlight and produce more energy, facilitating the development of a greater number of branches [

30] (Weber-Grullon et al., 2022). In contrast, total height is not necessarily linked to branching, as some species can grow in height without proportionally increasing the number of branches [

31] (Yang et al., 2024).

Vachellia and

Mimosa showed similar responses; even though

Mimosa are lower in stature than

Vachellia, burned plants resprouted and only a minimum percentage of plants died. Fire and grazing have modeled plant communities for millennia, and environmental conditions have selected species with morphological characteristics for deep water exploration and root reserves. This suggests that shrub morphology and branching capacity have been determined by environmental conditions and disturbances, with high capacity of resistance and survival [

32] (Scholtz et al., 2017). Post-fire resilience of shrubs may be associated with their branching capacity; shrubs with a larger diameter and bigger crown have more resources to recover after a disturbance such as fire [

33] (Capozzelli et al., 2020). Base diameter and crown area are an indicative of recovery capacity, as more robust shrubs with a larger crown seem better equipped to withstand damage and regenerate branches more easily [

34] (Jordan, 2024).

As brush encroachment increases, grasses and other flammable fuels decrease, so reintroducing fire after prolonged suppression may not necessarily be beneficial [

35] (Wright, 1974). It is critical to determine the frequency of fire needed to prevent shrubs from reaching a crown height or width at which fire is no longer an effective control tool. Other factors, such as fire frequency and intensity's effects on biodiversity, also need consideration [

36] (Jones and Tingley, 2021).

Interestingly, the relationship between the percentage of damage and crown diameter and height is not linear, indicating that prolonged periods without fire pressure or more favorable climatic events for shrub growth (e.g., winter rains; [

37] Biederman et al., 2018) could lead to "no return" colonization stages that are not controllable with fire. The woody species that resprout are the most difficult to control with fire alone and require additional management strategies to reduce their abundance and eventually remove them from the ecosystem. In agreement with some studies, combining prescribed burns with the browsing of ruminant species can reduce shrub density by up to 90% and promote grass cover by improving the light environment for herbaceous species [

38,

39,

40] (Ascoli et al., 2013; Pausas et al., 2016; O'Connor et al., 2020). Although controlled grazing can be a valuable supplementary technique, it cannot replace fire for controlling brush in these systems [

23,

40] (Harrington and Kathol, 2009; O'Connor et al., 2020). Properly timed prescribed burns can be a key ally in controlling shrubs before they become a serious problem.

Our study shows some weaknesses and limitations, such as the lack of spatial and temporal variability, which limits its general applicability. On the other hand, the observed recovery in 85% of the shrubs after the first rains suggests that post-fire climatic conditions, such as the amount and frequency of rainfall, were favorable for regeneration. In scenarios with lower water availability or more extreme climatic conditions, the results could be different. Although primary productivity recovery is mentioned within a year, longer-term effects, such as changes in species composition or ecosystem dynamics, are not fully explored. These effects could have more significant implications for long-term management.

Author Contributions

T. Alfaro-Reyna: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing; J. de la Cruz Domínguez: Methodology, Data curation, Writing – original draft; C.A. Aguirre-Gutierrez: Investigation; Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing; M. Luna-Luna: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – review & editing; D. Flores-Rentería: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing; J. Delgado-Balbuena: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.