1. Introduction

This article is part of a broader research that addresses the implementation of advanced computational technologies—specifically, those that simulate environments virtually—in conjunction with urban planning interventions. The aim is to contribute to the development and optimization of urban design processes by providing realistic quality analysis and impact assessments of potential spatial interventions without the need for physical execution. More specifically, this article examines and analyzes the potential of applying Virtual Reality (VR) in tactical urbanism implementations. This technology involves using real-time, computer-generated, three-dimensional graphical representations with immersive visualization tools to persuade the user that they are in a completely different environment from the physical one. Thus, VR can assist users in understanding and profoundly analyzing space.

Tactical Urbanism (TU) is an intervention approach characterized by quick execution, temporariness, scalability, and low cost to test and implement changes in design, mobility, land use, and social interaction [

1]. These interventions are often conducted experimentally, involving the local community and allowing urban authorities to evaluate the impacts before making permanent changes. TU is a flexible and adaptable approach to improving city quality, promoting a more participatory and democratic focus on the urban environment.

Understanding how users perceive, interpret, and interact with the environment is essential for creating legible, inclusive, and functional spaces that rely on tactical urbanism approaches. In turn, the recognition and interpretation of spaces involve the human capacity to perceive and analyze sensory information, alongside considering emotional factors, past experiences, and memory in constructing spatial perception. Therefore, this research aims to understand better how VR resources can enhance the development of tactical urbanism proposals while enabling designers to create environments that meet users’ needs and expectations, promoting a higher quality of life and well-being by transforming public spaces.

In this context, a key question emerges: How can virtual reality (VR) in tactical urbanism projects influence perceptions, social interactions, and the appropriate use of urban public spaces, thereby promoting positive and enriching experiences for users? This study aims to explore VR as a tool for visualizing tactical urbanism projects to understand better its potential and limitations regarding users’ spatial perception. The paper is structured as follows: (a) a literature review and analysis of existing theoretical and practical contributions to identify the potentials and challenges of these approaches, their applications, and limitations; (b) a case study examining the cognitive and sensory equivalence between virtual and real environments, conducted using an actual tactical urbanism intervention recreated on a digital platform; (c) an analysis of the exploratory study results; (d) discussion of the intersection between the literature review and the exploratory study; and (e) general conclusions based on the findings.

2. Literature Review

Recognizing spaces involves grasping and understanding the surrounding physical and social context. Perception, in this notion, refers to the human mental ability to perceive, analyze, and understand sensory information from the senses. This perception makes it possible to interpret and engage with space meaningfully.

In technical terms, space can be defined as the delimitation in one, two, or three dimensions. It represents the area, distance, or capacity occupied by specific physical objects or elements. In the urban context, space encompasses organized and delineated areas, such as streets, squares, and buildings, and undetermined areas, such as parks and natural landscapes. The physical dimension plays a fundamental role in human existence, as it is through it that one experiences interaction with the surroundings. Life as we know it would not occur without this extension [

2].

Therefore, spatial apprehension is a subjective and individual variable, subject to variations based on each person’s perspective and experience. Each individual brings unique connections, affections, and stimuli that shape their apprehension of the environment. Additionally, emotional perception plays a significant role, as certain circumstances and locations can evoke specific feelings in each person. Spatial apprehension is influenced by thoughts, emotions, and past experiences, which are stored in memory and shape the interpretation of reality [

3,

4,

5,

6].

Adler and Tanner [

2] emphasize that understanding human experience relies heavily on the apprehension of space, as it is through this spatial interaction that individuals engage with the world. They argue that phenomenology is instrumental in identifying the fundamental elements of reality by analyzing how sensory perceptions emerge. In contrast, Veríssimo [

7] presents a different perspective on phenomenology. According to him, reality is an intrinsic and unchanging aspect of the environment, and perception represents or interprets this pre-existing reality. This view underscores that while perception is a method of engaging with reality, the essence of reality itself remains constant and independent of perceptual processes.

Spatial perception, in turn, is deeply connected to corporeality and the presence of the perceiving subject. According to Merleau-Ponty [

8], objects are experienced in an embodied way, highlighting an intimate relationship between the perceiver and the objects. This means that the apprehension of space is inseparable from one’s existence and physical presence. Perception enables the description and understanding of spatial phenomena and conveys the perceptual impressions they evoke, even when viewed from a distance.

Building on the principles established by Adler and Tanner, Veríssimo, and Merleau-Ponty [

2,

7,

8], perceptual information is captured through specialized sensory tools and processed by human cognition. Spatial perception is critical in describing and understanding spatial phenomena, offering essential insights for planning, projects, and interventions. This approach underscores the significance of the relationship between the perceiving subject and the physical environment. The interaction between the perceiver and their surroundings profoundly influences how space is understood and interpreted, highlighting the intrinsic connection between spatial perception and experiential knowledge. Applying these principles is crucial for designing and understanding perceptible spaces. A perceptible space is one that users can easily perceive and interact with, providing clarity and facilitating orientation. It highlights spatial relationships and incorporates intuitive design decisions, making the environment more accessible and understandable. In contrast, an invisible space impedes the comprehension of the environment and diminishes the interaction between the user and the space, leading to a less effective or engaging experience [

9].

On the other hand, Cullen [

10] highlights the significance of emotional responses in spatial perception, arguing that the urban landscape can be described through individual emotions and interests. He suggests that each person’s unique perceptions and experiences of the built environment play a crucial role in understanding spaces. Designing urban spaces with consideration of users’ emotional responses is essential for creating environments that are pleasant, welcoming, and functional.

Semiotics, in this sense, also contribute to this understanding by analyzing how symbols and signs within environments are interpreted. According to Santaella [

11], human interpretation of the world is deeply rooted in subjective experiences, and semiotics provides insights into how different environments are designed to facilitate interaction and communication with users. For instance, using tools like virtual reality for representation can expand our understanding and exploration of space, allowing for a more nuanced and interactive engagement with the environment.

2.1. Virtual Reality

Virtual reality (VR) is an innovative technology that enhances perception and interaction with simulated environments through advanced computational resources. This technology, based on high-performance graphics processing, allows for complete immersion in three-dimensional virtual environments, extending the limits of conventional reality. Previously, VR systems were limited and primarily used simple visualization devices. However, with current technological advancements, VR headsets and haptic gloves provide highly realistic immersive experiences. These innovations can transform various sectors, including gaming, education, training, and remote professional collaboration. VR is constantly evolving and is mainly driven by companies focused on online social interactions and social networking platforms. These environments can include simulations, games, and applications, offering entertainment and problem-solving opportunities. Through devices like headsets and motion trackers, VR can stimulate users’ senses and create a sense of immersion and presence in the simulation [

12,

13].

VR has a wide range of applications in entertainment, especially in virtual travel, tourism, and electronic games. Additionally, VR can be applied in education, allowing students to visualize and interact with virtual environments that aid in understanding complex concepts [

14].

According to Shi et al. [

15], who used driving simulators to evaluate the drivers’ reactions, the immersive simulation promoted by VR aims to subjectively reproduce reality, allowing users to explore and interpret virtual environments meaningfully. Understanding the relationship between humans and the environment is crucial in the discussion, considering perceptual and cognitive aspects. Simulating perceptual experiences can be a valuable tool for urban and landscape projects, providing users with an experience close to reality.

Thus, it is understood that VR is characterized by the fusion of the real and the virtual, creating environments that can be explored in potential ways, regardless of time and space. Although these virtual environments do not have defined locations or times, they have the potential to materialize in specific moments and places, offering multiple possibilities [

12]. However, it is crucial to emphasize that VR simulation simplifies the real environment and cannot reproduce all sensory aspects without external devices. The simulated experience depends on the user’s perception, who receives, interprets, selects, and organizes sensory information [

16].

The application of VR in urban planning offers various opportunities, such as enhancing communication and understanding of urban projects, both for professionals and the general public. The ability to explore virtual environments in an immersive and interactive way establishes a deeper emotional connection with the environment, facilitating the understanding of the impacts and benefits of a project. Additionally, VR enables public participation in urban planning, allowing citizens to explore project proposals, express their opinions, and contribute to decision-making [

17].

Although VR is a valuable tool in urban planning, it is crucial to recognize that it cannot completely replace the need for real-world experiences. However, VR plays a complementary and enriching role in the design and decision-making process, allowing for a more detailed exploration and a broader understanding of the complexities of the urban environment. As VR technology evolves, new applications and possibilities emerge, providing a solid foundation for developing more sustainable, inclusive, and livable cities. Combining the real world with the virtual experiences provided by VR can open pathways for a more informed and participatory approach to urban planning, resulting in more effective and satisfying solutions for community needs [

17].

2.2. Advancing the Right to the City: Addressing Inequities through Inclusive Planning, Digital Participation, and Tactical Urbanism

There is an urgent need to rethink urban planning by adopting more participatory and collaborative approaches. It is essential to involve citizens as active agents in the planning process, valuing their experiences and local knowledge. Sensitive urban planning should consider diversity and inclusion, promoting the co-creation of public spaces that meet the needs and aspirations of the community. Additionally, it is crucial to preserve collective memory and heritage elements, creating a connection between the city’s past and future [

18].

By adopting a more holistic and multidisciplinary approach, urban planning can promote urban vitality, quality of life, and sustainability. This involves an integrated vision, considering not only physical and functional aspects but also the urban fabric’s social, cultural, and environmental dimensions. With a more inclusive and community-oriented planning approach, building more humane, vibrant, and resilient cities where the urban fabric reflects its inhabitants’ identity and shared values is possible.

Harvey [

19] emphasizes that, although human rights ideals are promoted for building a better world, they are often suppressed by liberal hegemony, neoliberal market logic, and the importance of private property rights and profit. In this context, the concept of the right to the city arises, challenging dominant structures and seeking a more inclusive and democratic approach to urban space.

The right to the city recognizes that urban space should not be exclusively for profit but rather a place for coexistence and citizen participation. Harvey [

19] highlights the importance of ensuring equitable access to urban resources for all city inhabitants, such as adequate housing, public services, green spaces, and infrastructure. Furthermore, the right to the city emphasizes the active participation of citizens in decision-making about urban planning, promoting democratic and transparent processes.

This approach challenges socio-spatial inequalities and seeks to overcome the segregation and exclusions in contemporary cities. By prioritizing social justice, inclusion, and sustainability, the right to the city proposes a new urban paradigm that values collective well-being and citizens’ quality of life.

However, achieving the right to the city faces significant challenges, such as resistance from hegemonic forces and the need for structural changes. To achieve a more just and democratic city, continuous engagement from citizens, social movements, and governments committed to promoting equity and popular participation is essential.

Pursuing the right to the city involves confronting the dominant logic based on real estate speculation, gentrification, and socio-spatial exclusion. It is necessary to ensure that the city is an accessible and inclusive space for all people, regardless of their origin, income, or social condition. This involves promoting adequate housing, quality public services, efficient transportation, green spaces, and infrastructure that meets collective needs. In this context, digital resources have been widely utilized to support these objectives, facilitating a more participatory decision-making process [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31].

Additionally, according to the work of Hovik [

32], it is fundamental to establish democratic mechanisms that allow for effective citizen participation in decisions affecting urban space. This includes transparent urban planning processes, public consultations, and involving residents in defining policies and projects that shape their communities. Popular participation is a crucial element to ensure that the voices and perspectives of citizens are considered in urban policy formulation.

In summary, overcoming the challenges to achieving the right to the city requires a profound transformation in the political, economic, and social structures that sustain urban inequalities. This requires a critical approach committed to social justice, seeking equitable redistribution of resources and opportunities. In this context, in response to the limitations of state urban planning, the concept of tactical urbanism emerges, aiming to find quick and low-cost solutions to challenges related to public spaces. These interventions arise from the need to address specific issues in citizens’ daily lives. According to Silva [

33], tactical urbanism is a broad expression that describes many different kinds of city interventions. TU aims to raise public awareness, often through artistic expression in public spaces. These interventions are considered strategies for building and revitalizing communities, adopting short-term approaches with low costs and potential for replication [

1].

Some commonly employed tactics in tactical urbanism include street closures, the creation of plazas, redesigning roadways, creating bike lanes, planting community gardens, and installing parklets. Street closures aim to shift the focus from vehicles and transform a street into a space for pedestrians and active transportation while maintaining, if necessary, access to local vehicles or services. The creation of plazas seeks to increase green areas in urban regions, often utilizing underused public spaces or vacant lots. These plazas can be combined with lightweight and movable furniture and cultural activities.

Therefore, tactical urbanism actions are not limited to physical changes in space but also promote a shift in people’s mindset, encouraging attitudes of solidarity, respect, and love for the city. Through simple urban kindness practices, such as caring for trees, celebrating local events, and picking up litter, tactical urbanism aims to create habits that positively transform the urban environment.

2.3. Literature Review Main findings

The selected references directly addressed the themes explored in this research and provided valuable insights for its analysis. Some works reviewed during the research process did not stem from foundational or novel studies on virtual reality as a tool for understanding tactical urbanism projects and were excluded from this analysis.

Priority was given to works that included research conducted by the authors on the subject. The findings from this investigation reflect the content highlighted by these authors, whose works helped shape the argumentation of this paper.

Out of over 80 sources reviewed on the highlighted topic, 20 were selected, including books, academic papers, and scientific articles.

A consistent mention of “virtual reality” across the selected sources indicates that this theme is recurrent in the literature. Consequently, all chosen references revolve around this concept.

From all the findings, four key sources were selected for their relevance to the theme and focus of this article. These sources were sufficient for a comprehensive understanding of the subject and strongly supported the paper’s proposition. In other words, they form the foundation for the argument that virtual reality can be a crucial tool for understanding tactical urbanism projects even before they are physically realized. However, some works require careful and interpretative reading to grasp this implication fully.

The primary works that served as the foundation for this paper, along with other references included in the bibliography, are detailed below in

Table 1, listing the sources, titles, authors, and year of publication:

3. Case Study

Our case study involved a tactical urbanism intervention paired with a digital recreation of the scenario using 360° images and VR headsets. This approach enabled a comparative analysis of perceptions between the real and virtual environments. The experiment was conducted during a workshop titled “Virtual Reality vs. Tactical Urbanism,” held on May 10 and 12, 2022, as part of the XI Architecture and Urbanism Week at UniAcademia, in the city of Juiz de Fora, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Participants, including students and professors who regularly frequent the institution, were invited to participate in interviews using a semi-structured questionnaire. This selection was designed to capture the perceptions of a specific target audience, offering valuable insights for urban design. We employed the AR4CUP (Augmented Reality for Collaborative Urban Planning) methodology, developed by a multidisciplinary team at the Polytechnic University of Milan [

15,

26,

27]. This approach emphasizes the integration of technology in urban studies. It involves using questionnaires to collect data on participants’ sensations, which is crucial for describing and interpreting the lived experience.

The initial step of the experiment involved selecting the location and type of intervention. Considering the available time and resources, we decided to create a parklet in one of the parking spaces at UniAcademia’s campus. This spot was strategically chosen due to its proximity to the cafeteria, a high-traffic area. The intervention aimed to foster more significant social interaction in the surrounding area, particularly near the cafeteria, which lacked a variety of comfortable seating options for extended use. The structure featured a sofa constructed from pallets, cushioned outdoor pillows, and intertwined sisal ropes on a wooden framework. These ropes not only supported decorative lighting but also allowed users to modify it in the future. Volunteer students actively assembled the intervention, as depicted in

Figure 1.

The experiment adopted two methodological measures to ensure consistency and minimize bias and variables that could affect participants’ perceptions. The first measure involved establishing fixed viewpoints or POVs, which meant setting fixed perspectives for all participants, both in the physical reality and the virtual simulation. This approach ensured that all participants were exposed to the same initial conditions, reducing potential variations between observation points and allowing for a more accurate and objective comparison of their perceptions.

Figure 2 shows the different POVs used in the case study.

The second implemented measure was a screening protocol to control participants’ entry to the selected viewpoints, directing them to the designated observation points and preventing deviations or external interferences during observation. This procedure aimed to maintain the integrity of the experimental conditions, ensuring that participants’ perceptions were obtained consistently and comparable. This protocol established groups A and B, each following different viewpoints in real and virtual “visits.” This approach was intended to preserve randomness, minimize the influence of one image on another in the results, and facilitate the logistics of the experiment when multiple participants were present simultaneously. Participants were instructed to observe their surroundings and complete a questionnaire regarding their emotions related to each viewpoint. Afterward, they were directed to the next POV.

Figure 3 illustrates the screening logic.

A VR Box was used to view the virtual environment. This affordable virtual reality headset allows users to explore and interact with 360° content, whether photos or videos, using a smartphone.

Figure 4 depicts the distinct modes of visit in the case study: real and virtual.

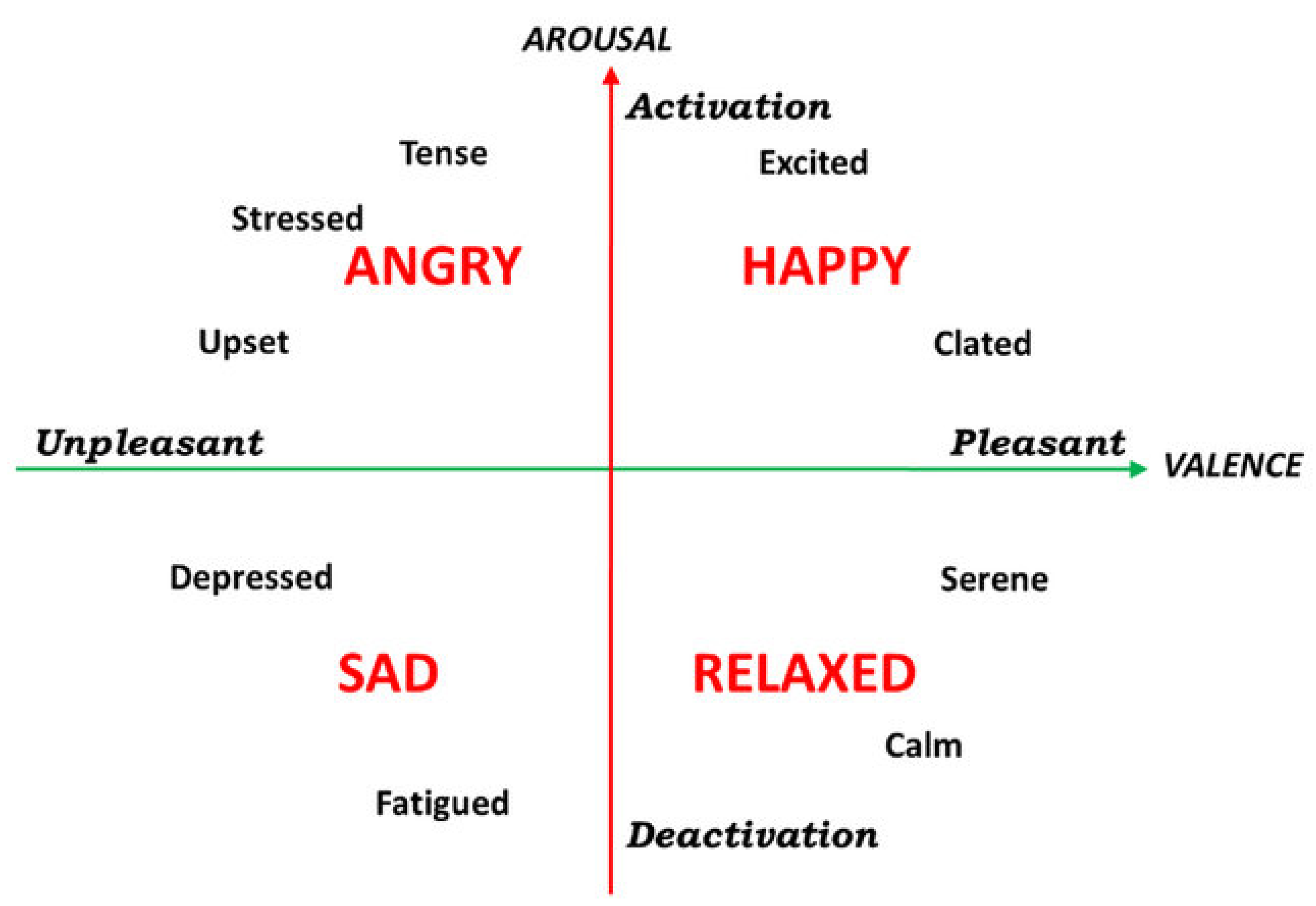

The objective of the administered questionnaire was to gather data on participants’ receptiveness to the urban intervention and to assess whether the virtual reality (VR) effectively represented the graphic representation. This questionnaire, which can be found in the appendix, received 65 valid responses and consists of two sections. The first section focuses on the user profile. In contrast, the second section evaluates the perception of the space, including aspects such as pleasure, activity, and usage related to each viewpoint (both real and virtual). This latter section is repeated after each viewpoint the user observes to allow for a comparative analysis. It employs Russell’s circumplex model of affection [

34], which helps interpret emotions based on participants’ responses. In addition to feelings, this section addresses questions related to spatial understanding and cognitive relationships, such as legibility and meaning. The aim is to collect information on visual variety and understanding of the intervention. The final part of this section seeks to identify perceived uses for the specific location.

Figure 5.

Russell’s circumplex model of affect [

34] features a horizontal axis representing valence (pleasure) and a vertical axis representing arousal. The artwork is referenced from Valenza et al. [

35].

Figure 5.

Russell’s circumplex model of affect [

34] features a horizontal axis representing valence (pleasure) and a vertical axis representing arousal. The artwork is referenced from Valenza et al. [

35].

4. Analysis of Case Study Results

This analysis of the Case Study results compares participants’ perceptions of the tactical urbanism intervention in real and virtual environments. Data was collected through questionnaires that captured participants’ sensations and experiences. By evaluating these perceptions, the study provides valuable insights into the effectiveness of integrating urban planning with digital technologies, offering a comprehensive understanding of such interventions’ impact on physical and virtual spaces.

The following results were observed regarding user demographics: more than two-thirds were between 18 and 24 years old, nearly 77% had completed only high school, and over two-thirds were students enrolled in the course where the experiment was conducted (Architecture and Urbanism). These results were consistent with expectations, given that the experiment was part of a specific academic event at a higher education institution.

The analysis of participants’ responses regarding their perception of the environment revealed a general trend of acceptance and satisfaction with the created intervention. Given that the study focuses on emotions and affect, Russell’s circumplex model of affect was adapted to suit the objectives of the work. In both the real and virtual environments, most participants positioned themselves on the happiness spectrum, indicating that the intervention was perceived positively, creating an atmosphere conducive to social interaction and leisure.

Figure 6 shows the participants’ responses regarding their perception of the environment in Russell’s circumflexes for real and virtual spaces.

The part of the questionnaire aimed at understanding spatial coherence, complexity, legibility, and imaginability provided by the intervention yielded overwhelmingly favorable results. Participants found that the virtual environment effectively simulated these aspects compared to the real environment.

Figure 7.

Comparing spatial coherence, complexity, legibility, and imaginability of both real and virtual spaces according to participants’ responses.

Figure 7.

Comparing spatial coherence, complexity, legibility, and imaginability of both real and virtual spaces according to participants’ responses.

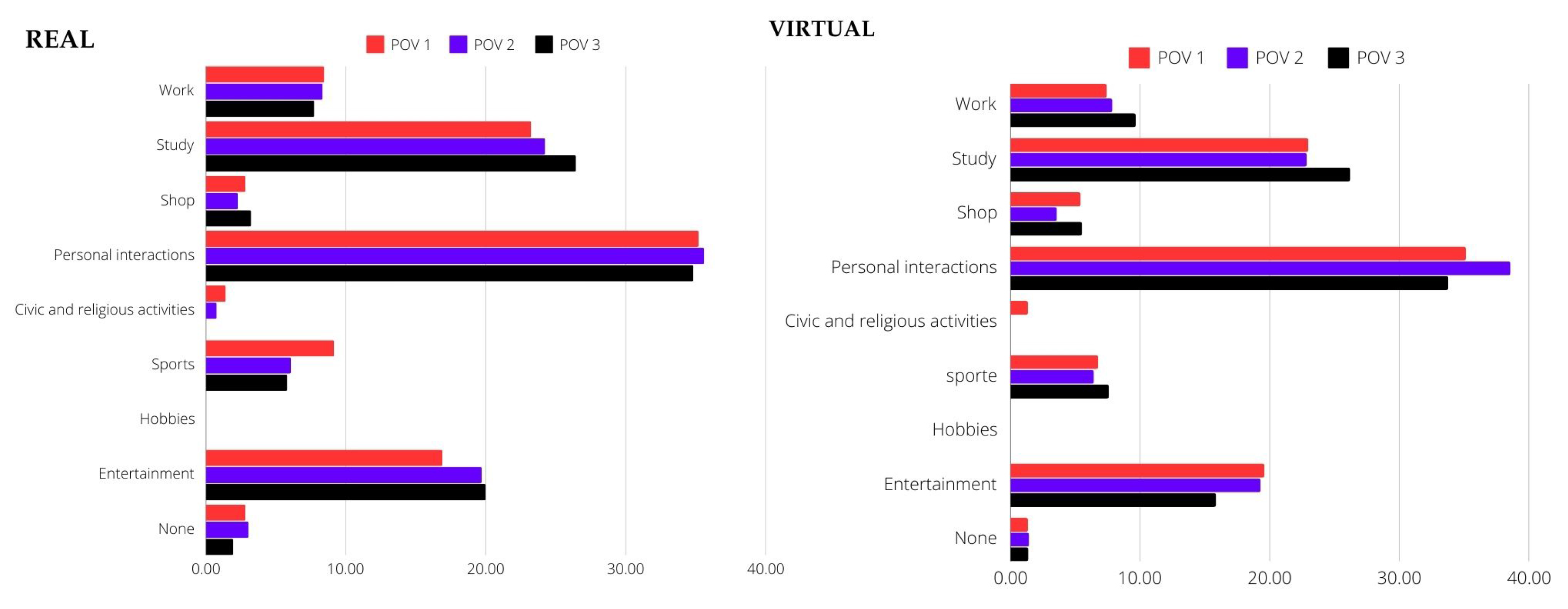

Regarding preferred activities in the space, participants mentioned social interaction and studying the most frequently in real and virtual environments. This aligns with the intervention’s goal of fostering interpersonal interaction and fits the academic context of the event. Work-related activities were mentioned less often, suggesting that the space was perceived more as a venue for socializing and entertainment rather than a work environment.

Figure 8 depicts the participants’ preferred activities for both real and virtual spaces.

Table 2 below provides a more straightforward illustration of the results related to preferred activities in the space. Considering the adopted margin of error of 10%, the data from the case study results shows that, out of 60 participants, between 30 and 35 preferred social interaction activities in the real environment, while 20 to 25 preferred studying. In the virtual environment, the proportion of responses indicating a preference for social interaction was between 35 and 40, whereas for studying, it was between 25 and 30.

The analysis of the highlights mentioned by participants revealed the significance of the social dimension in the perception and experience of urban space. The term “interaction” emerged as the most frequent and representative in responses, underscoring the importance of social interactions for user experience. These results provide a foundation for future interventions and urban design projects to promote social interaction and recreational activities in public spaces.

Therefore, the results of this study offer valuable insights into users’ perceptions and experiences regarding the investigated urban space. The findings contribute to a deeper understanding of the impact of urban interventions on social interaction and the effective use of public spaces. These discoveries are pertinent to urban design and can guide the development of projects that foster positive and enriching experiences for urban space users.

5. Discussion

The analysis of the obtained results provides a robust understanding of users’ perceptions and experiences regarding the use of virtual reality as a tool to support the comprehension of tactical urbanism projects. The findings reveal critical aspects of spatial perception, social interaction, and the appropriate use of urban public spaces. Among the authors referenced in the theoretical foundation, Adler and Tanner [

2] are particularly notable for their insights into spatial perception as a complex human process shaped by sensory input, emotions, and past experiences. Their perspective underscores the importance of considering users’ subjective perceptions when designing and transforming urban spaces.

The application of virtual reality as a representation and simulation tool is discussed extensively by several authors, including Rodrigues and Porto [

16], who highlight VR’s immersive and interactive possibilities in exploring and understanding urban spaces. This technology has the potential to create realistic virtual experiences, allowing users to engage with the environment meaningfully before its physical realization.

We also emphasize the relevance of tactical urbanism as an innovative approach to revitalizing and transforming public spaces since quick and low-cost interventions in the urban environment can raise public awareness, promote civic participation, and create spaces better suited to community needs.

Regarding the specific results of this study, participant responses indicated a general trend of acceptance and satisfaction with the tactical urbanism interventions, both in real and virtual environments. Participants reported a favorable atmosphere for social interaction and leisure, identifying activities such as studying and socializing as their most preferred. These results align with the intervention’s goal of fostering interaction among people and within the academic context of the event.

Participants’ feedback emphasized the importance of the social dimension in the perception and experience of urban spaces, reinforcing the need to design public areas that promote positive social interactions and leisure activities. This finding echoes the ideas of authors like Merleau-Ponty [

8] and Cullen [

36].

Based on the results, we can infer that the application of virtual reality to support the understanding of tactical urbanism projects positively influences perception, social interaction, and the appropriate use of urban public spaces. VR facilitates positive and enriching user experiences by allowing professionals and citizens to explore and interact with virtual environments realistically, contributing to participatory urban planning and creating more attractive, inclusive, and functional spaces.

The research corroborates the theoretical and practical contributions of the authors cited in the theoretical foundation, providing valuable insights for improving urban planning practices and public space design. By understanding how virtual reality and tactical urbanism influence the perception and experience of urban spaces, more effective and satisfying interventions can be developed to meet community needs and expectations.

However, it is essential to acknowledge that the application of virtual reality in urbanism still presents challenges and limitations. VR simulation simplifies the real environment, relies heavily on the user’s perception, and cannot fully replace real-world experiences. Still, it is a complementary and enriching tool in the design and decision-making process. In summary, we advocate that VR can complement tactical urbanism interventions or, in specific contexts, offer a cost-effective and quicker alternative before physical implementation.

Given these considerations, future research opportunities exist to refine and deepen our understanding of virtual reality’s effects in the context of tactical urbanism. Further studies could explore the impact of immersion and interactivity on spatial perception, compare perceptions of tactical urbanism projects in virtual and real environments, and assess the effects of these interventions on user behavior and well-being.

6. Conclusions

This study explored virtual reality as a tool to enhance the understanding of tactical urbanism projects. The investigation focused on analyzing how VR impacts perception, social interaction, and the use of urban public spaces. The theoretical framework for this study incorporated concepts of spatial perception, tactical urbanism, and virtual reality, offering a comprehensive perspective on how VR can support and improve the analysis and design of urban spaces.

The literature review revealed/confirmed that (i) as an immersive and interactive technology, VR offers a highly realistic way to explore and experience spaces. It enhances the understanding and visualization of urban projects, introducing new dimensions for spatial analysis and design. This capability can positively impact the tactical urbanism approach by complementing it or, in certain contexts, providing an alternative; (ii) Spatial perception is a complex human skill that integrates sensory information with emotional responses, past experiences, and memory. It shapes how individuals interpret and make sense of spatial environments and should be carefully considered when planning to use virtual reality, and (iii) tactical urbanism advocates for rapid, low-cost interventions in urban spaces to rejuvenate and transform public areas. It emphasizes citizen involvement and aims to create environments that better meet community needs. Besides empowering non-trained community stakeholders who cannot foresee the impacts of design implementation, it can be combined with VR to enhance and refine interventions’ analysis and design before implementation.

The results obtained from the participant intervention strongly support the central argument of the research, validating the proposed research problem. The analysis of participant responses indicated a positive perception of the intervention, underscoring the significance of the social dimension in experiencing and interacting with urban spaces. Social interaction and study were the most frequently mentioned activities, suggesting that the environment was perceived as conducive to social gatherings and leisure. Furthermore, the analysis of participant feedback emphasized the critical role of social interactions in shaping user experience, offering valuable insights for future urban design projects aimed at promoting social interaction and leisure activities in public spaces.

Based on the theoretical framework and the results of the intervention, it can be concluded that the application of virtual reality in tactical urbanism projects positively influences the perception, social interaction, and appropriate use of urban public spaces. Virtual reality is a valuable tool for understanding and visualizing urban projects before implementation, offering critical insights into urban design. By creating immersive and interactive virtual environments, users can explore and experience spaces in greater detail, enhancing their comprehension of urban interventions’ potential impacts and benefits.

However, it is essential to note that virtual reality complements and enriches the urban planning process, offering a more comprehensive and immersive view of space. Additionally, the application of virtual reality in the context of tactical urbanism requires active citizen participation, ensuring that their voices and perspectives are considered in the decision-making process.

References

- Lydon, M.; Garcia, A. Tactical Urbanism: Short-Term Action for Long-Term Change; Island Press, 2015; ISBN 978-1-61091-526-7.

- Adler, F.R.; Tanner, C.J. Urban Ecosystems: Ecological Principles for the Built Environment; Cambridge University Press, 2013; ISBN 978-0-521-76984-6.

- Deleted for peer review.

- Fiori, I.M.; Schmid, A.L. Espaços emocionais: Atmosfera e percepção espacial na arquitetura. Cad. Pós-grad. Em Arquitetura E Urban. 2020, 20, 121–132. [CrossRef]

- Deleted for peer review.

- Deleted for peer review.

- Verissimo, D.S. Escritos Sobre Fenomenologia Da Percepção: Espacialidade, Corpo, Intersubjetividade e Cultura Contemporânea. 2021.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. Phenomenology of Perception; 1st edition.; Routledge: London New York, 2013; ISBN 978-0-415-83433-9.

- Peters, G. A caminho da cidade: momentos decisivos na teorização do espaço geográfico em Bourdieu. Soc. E Estado 2022, 37, 1003–1025. [CrossRef]

- Cullen, G. Concise Townscape; Routledge, 2012;

- Santaella, L. Semiótica Aplicada; 2a edição.; Cengage Learning, 2018; ISBN 978-85-221-2642-2.

- Sherman, W.R.; Craig, A.B. Understanding Virtual Reality: Interface, Application, and Design; 1st edition.; Morgan Kaufmann: Amsterdam ; Boston, 2002; ISBN 978-1-55860-353-0.

- Anthes, C.; García-Hernández, R.J.; Wiedemann, M.; Kranzlmüller, D. State of the Art of Virtual Reality Technology. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Aerospace Conference; March 2016; pp. 1–19.

- Jerald, J. The Vr Book: Human-Centered Design for Virtual Reality; Illustrated edition.; ACM Books: New York San Rafael, California, 2015; ISBN 978-1-970001-12-9.

- Shi, Y.; Boffi, M.; Piga, B.E.A.; Mussone, L.; Caruso, G. Perception of Driving Simulations: Can the Level of Detail of Virtual Scenarios Affect the Driver’s Behavior and Emotions? IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2022, 71, 3429–3442. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, G.P.; Porto, C. de M. Realidade Virtual: conceitos, evolução, dispositivos e aplicações. Interfaces Científicas - Educ. 2013, 1, 97–109. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, V.C. A realidade virtual e aumentada como ferramenta auxiliar no ensino de projeto arquitetônico : um estudo de caso em disciplinas de projeto de arquitetura e urbanismo.

- de Macêdo, A.F.; de Almeida, A.M. O espaço público frente ao urbanismo tático: o caso das Praias do Capibaribe.

- Harvey, D. The Right to the City. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2003, 27, 939–941. [CrossRef]

- Duarte, J.P.; Beirão, J. Towards a Methodology for Flexible Urban Design: Designing with Urban Patterns and Shape Grammars. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Duarte, J.P.; Beirão, J.N.; Montenegro, N.; Gil, J. City Induction: A Model for Formulating, Generating, and Evaluating Urban Designs. In Digital Urban Modeling and Simulation; Arisona, S.M., Aschwanden, G., Halatsch, J., Wonka, P., Eds.; Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2012; pp. 73–98 ISBN 978-3-642-29758-8.

- Gil, J.; Beirão, J.N.; Montenegro, N.; Duarte, J.P. On the Discovery of Urban Typologies: Data Mining the Many Dimensions of Urban Form. Urban Morphol. 2012, 16, 27.

- Deleted for peer review.

- Eloy, S. How Present Am I - Three Virtual Reality Facilities Testing the Fear of Falling. In Proceedings of the Kepczynska-Walczak, A, Bialkowski, S (eds.), Computing for a better tomorrow - Proceedings of the 36th eCAADe Conference - Volume 2, Lodz University of Technology, Lodz, Poland, 19-21 September 2018, pp. 717-726; CUMINCAD, 2018.

-

Experiential Walks for Urban Design: Revealing, Representing, and Activating the Sensory Environment; Piga, B.E.A., Siret, D., Thibaud, J.-P., Eds.; Springer Tracts in Civil Engineering; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-76693-1.

- Piga, B.E.A. Experiential-Walk: Experiencing and Representing the City for Urban Design Purposes. In Experiential Walks for Urban Design: Revealing, Representing, and Activating the Sensory Environment; Piga, B.E.A., Siret, D., Thibaud, J.-P., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 187–206 ISBN 978-3-030-76694-8.

- Salerno, R. From “La Dérive” to Virtual Reality: Representing the Urban Walk Between Reality, Senses and Imagination. In Experiential Walks for Urban Design: Revealing, Representing, and Activating the Sensory Environment; Piga, B.E.A., Siret, D., Thibaud, J.-P., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 163–174 ISBN 978-3-030-76694-8.

- Deleted for peer review.

- Deleted for peer review.

- Deleted for peer review.

- Pereira, R.H.M. Introduction to Urban Accessibility: A Practical Guide with R Available online: https://www.ipea.gov.br/acessooportunidades/en/publication/2022_book_intro_acessibilidade_r/ (accessed on 8 August 2024).

-

Citizen Participation in the Information Society: Comparing Participatory Channels in Urban Development; Hovik, S., Giannoumis, G.A., Reichborn-Kjennerud, K., Ruano, J.M., McShane, I., Legard, S., Eds.; Springer Nature, 2022.

- Silva, P. Tactical Urbanism: Towards an Evolutionary Cities’ Approach? Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2016, 43, 1040–1051. [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A. A Circumplex Model of Affect. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 1161–1178. [CrossRef]

- Valenza, G.; Citi, L.; Lanatá, A.; Scilingo, E.P.; Barbieri, R. Revealing Real-Time Emotional Responses: A Personalized Assessment Based on Heartbeat Dynamics. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4998. [CrossRef]

- Cullen, G. The Concise Townscape; Reprint edition.; Architectural Press: Oxford ; Boston, 1961; ISBN 978-0-7506-2018-5.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).