Submitted:

04 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

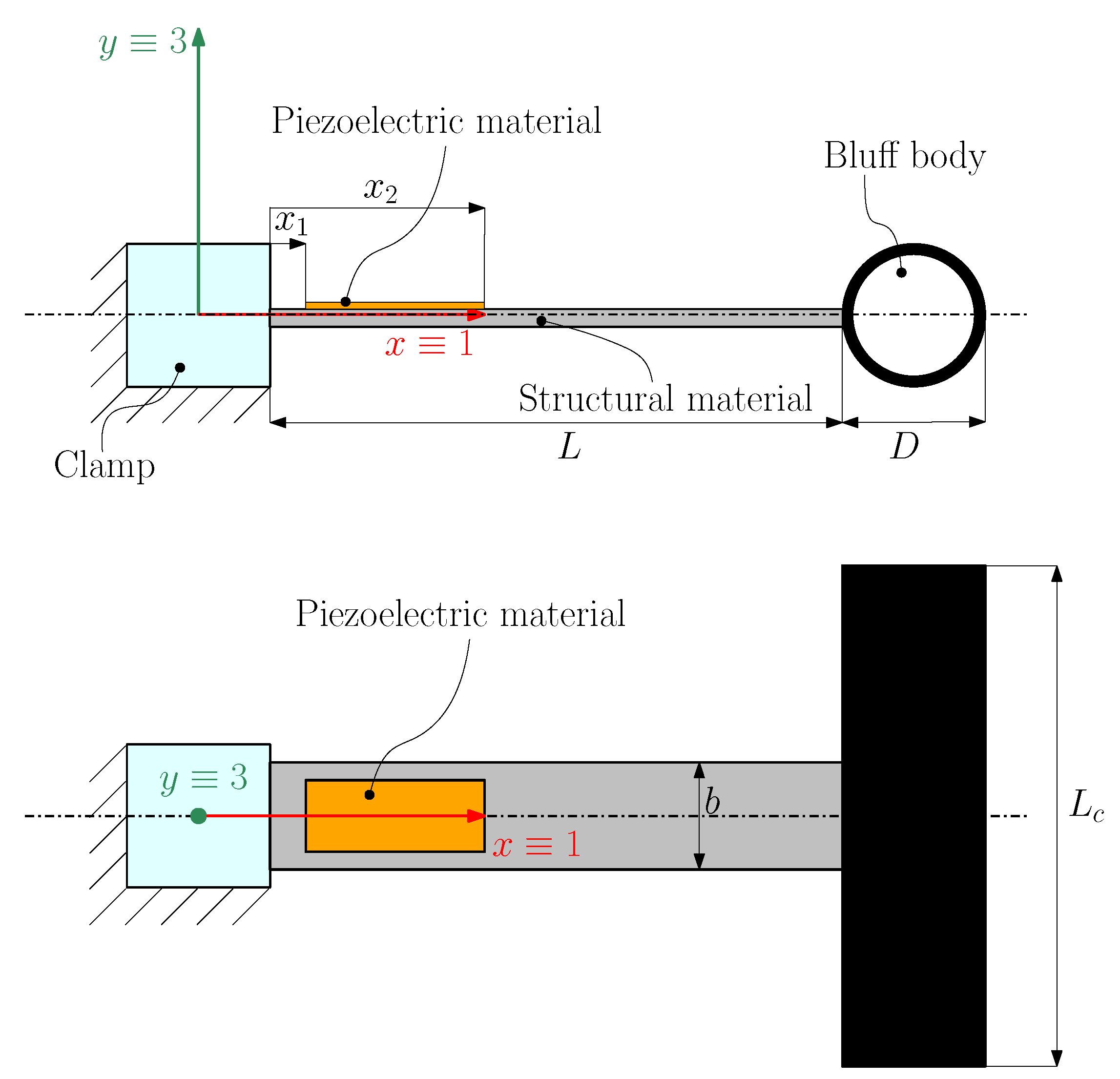

2. Mathematical Model of the VIV Harvester

2.1. Electromechanical Model

2.2. Aerodynamic Force

2.3. Dimensionless Harmonic Solution

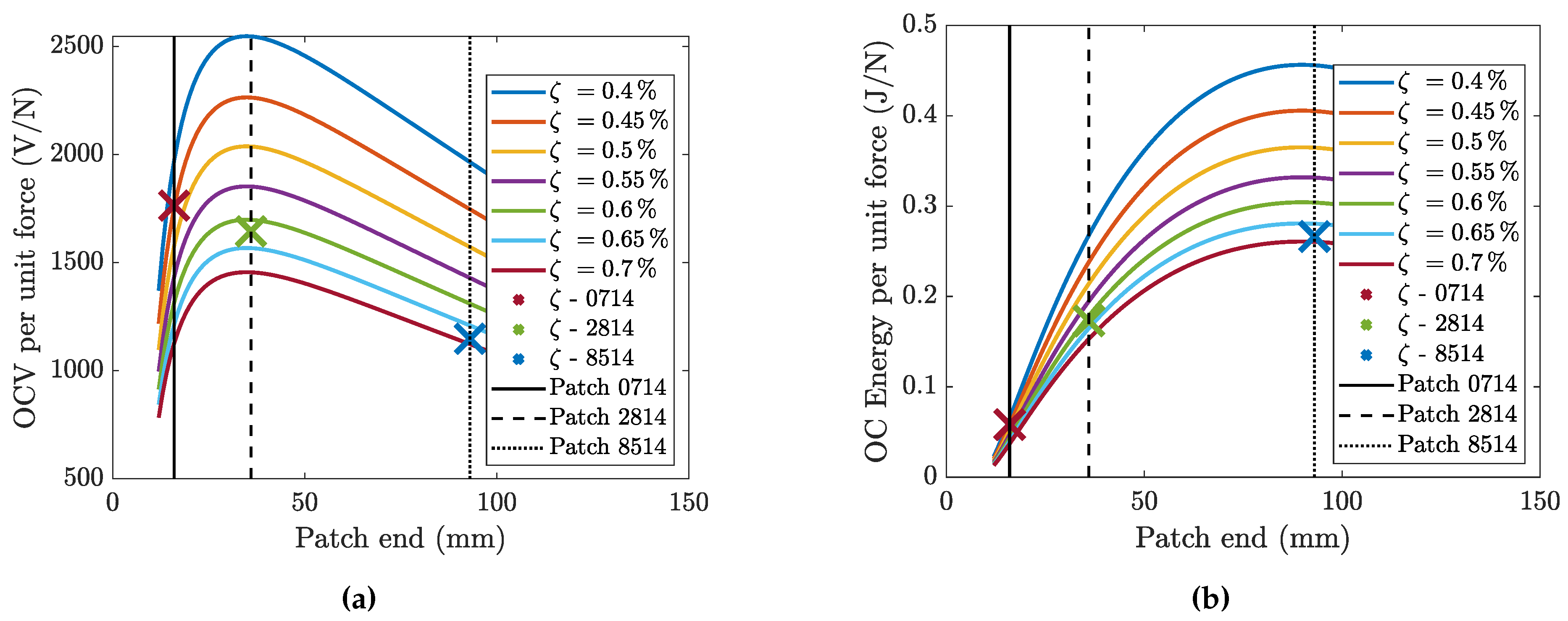

2.4. Calculated Results

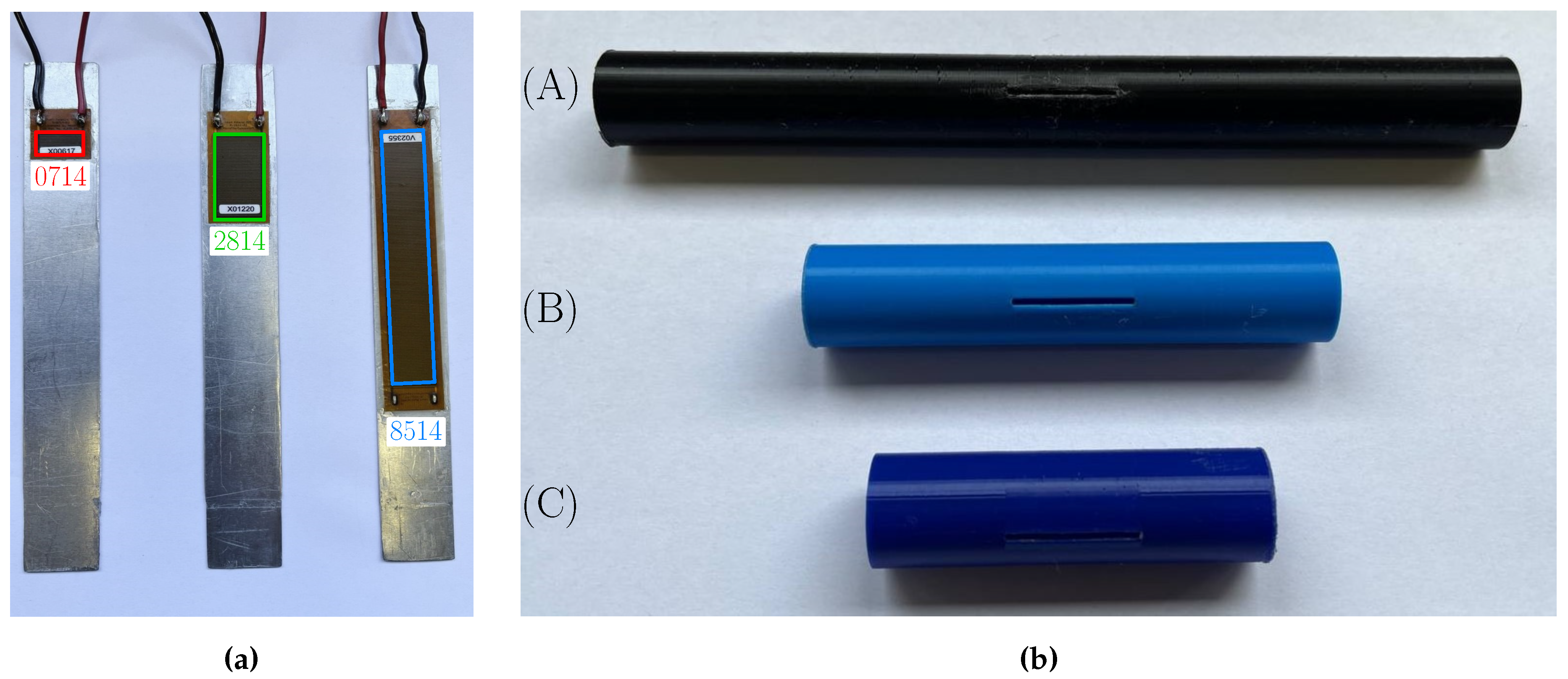

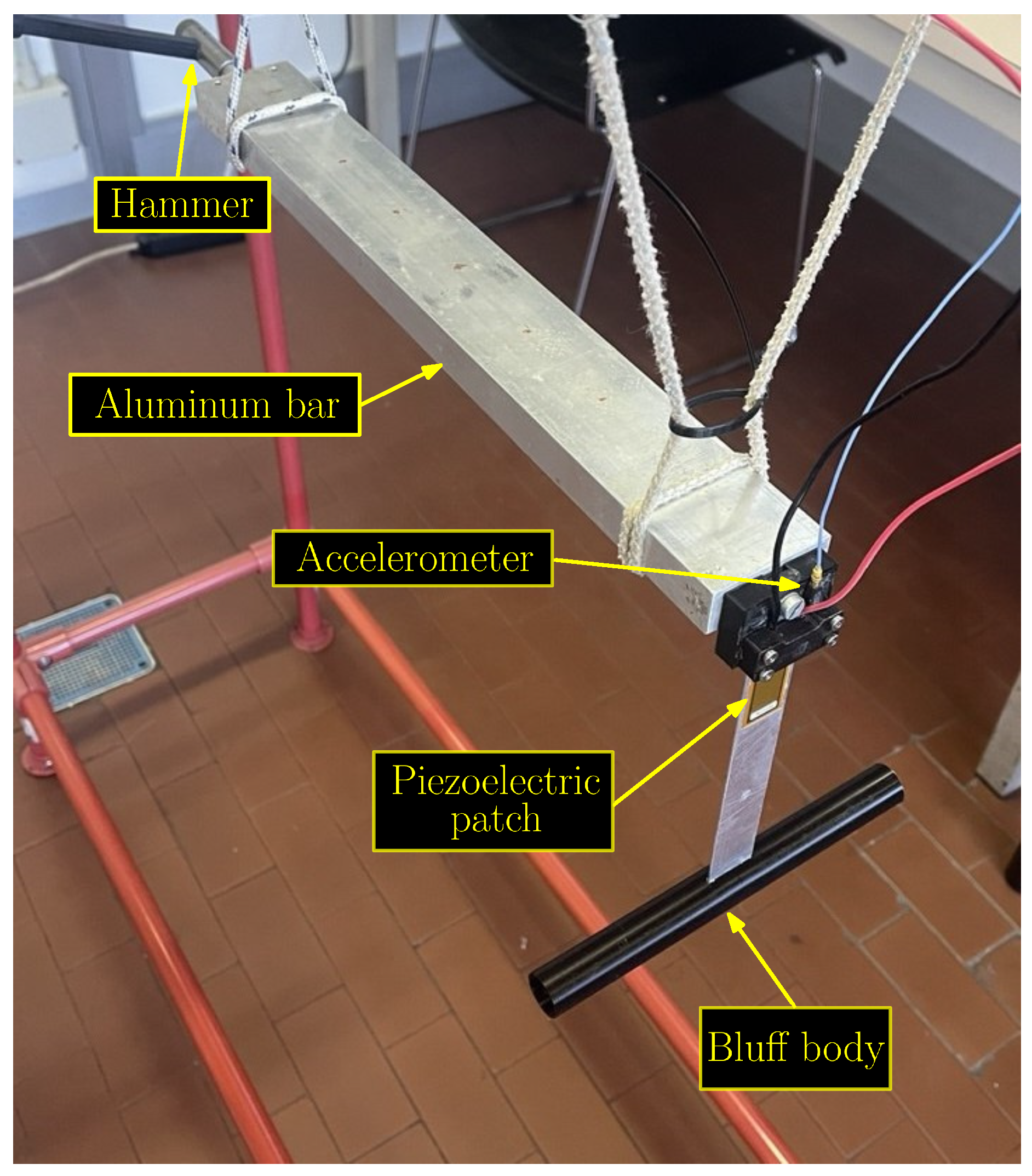

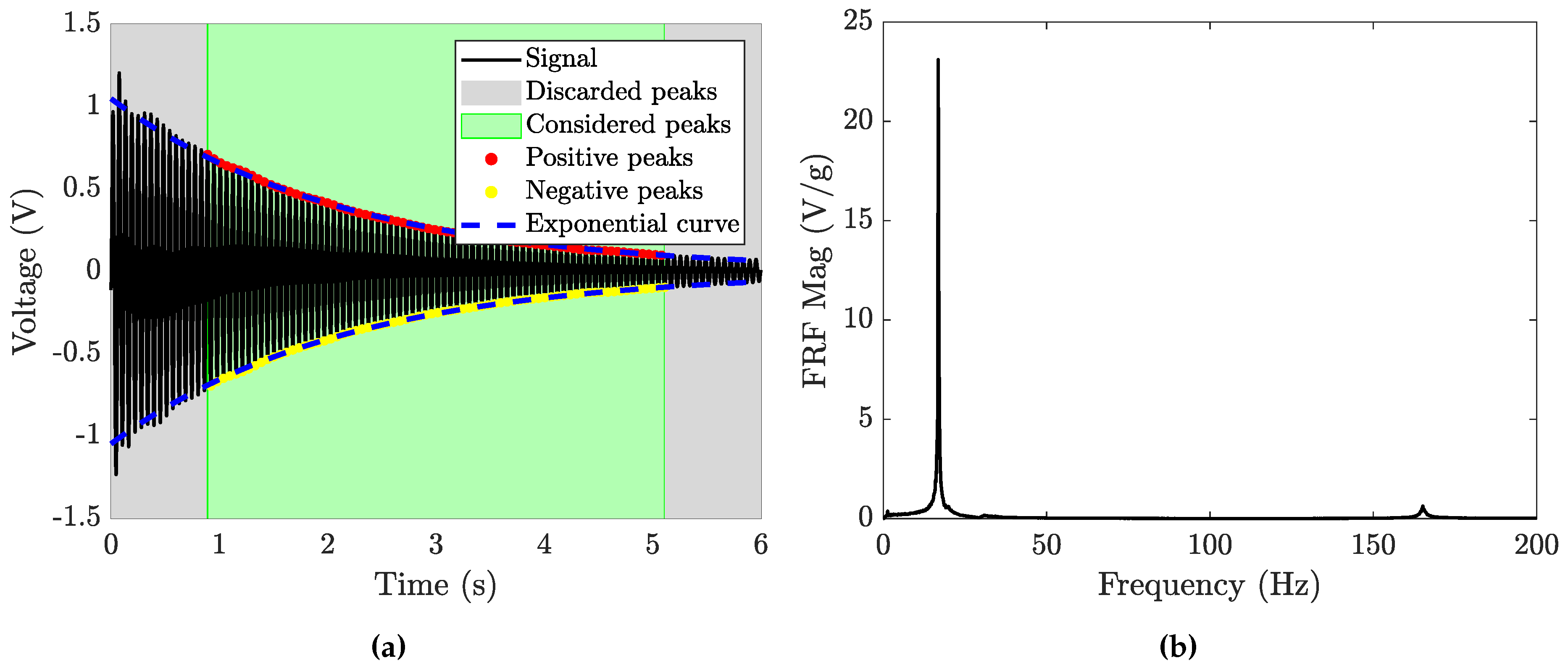

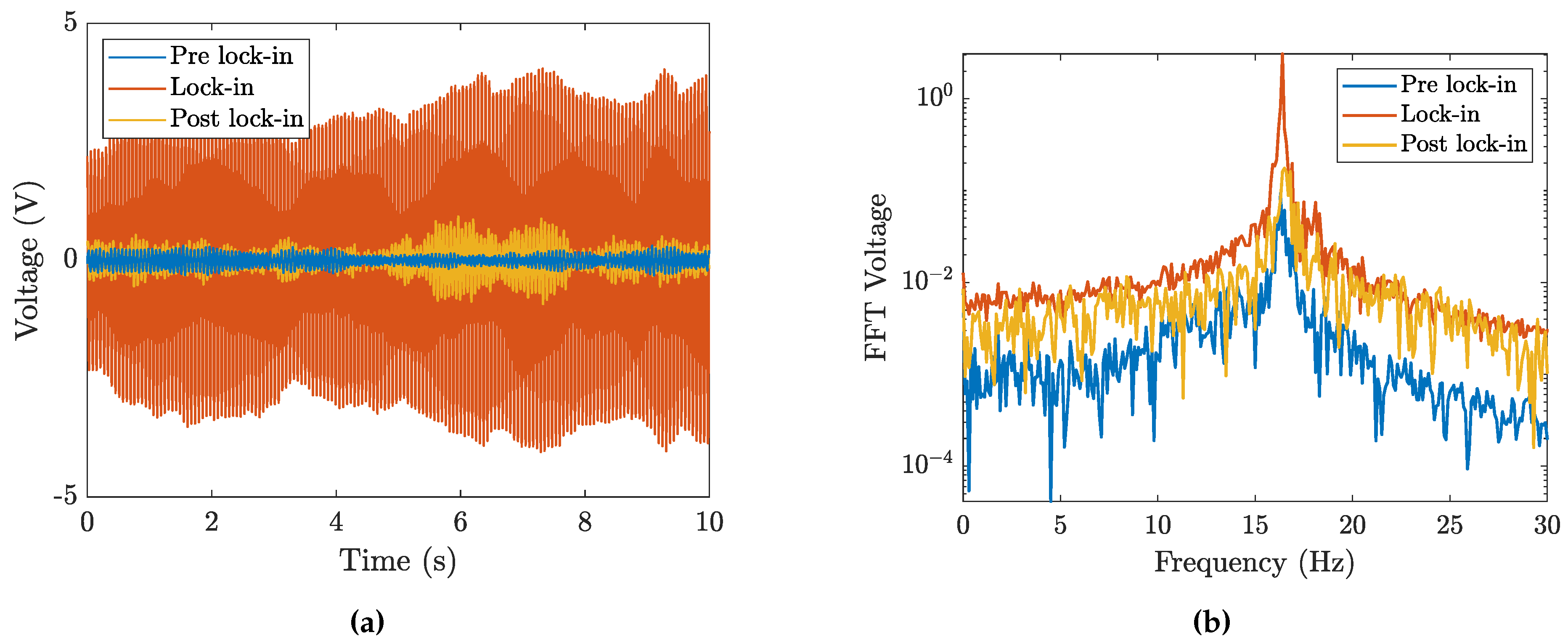

3. Experimental Characterization of the Harvester by Means of Impulsive Tests

4. Effects of Design Parameters of the Harvester in Wind Tunnel Experiments

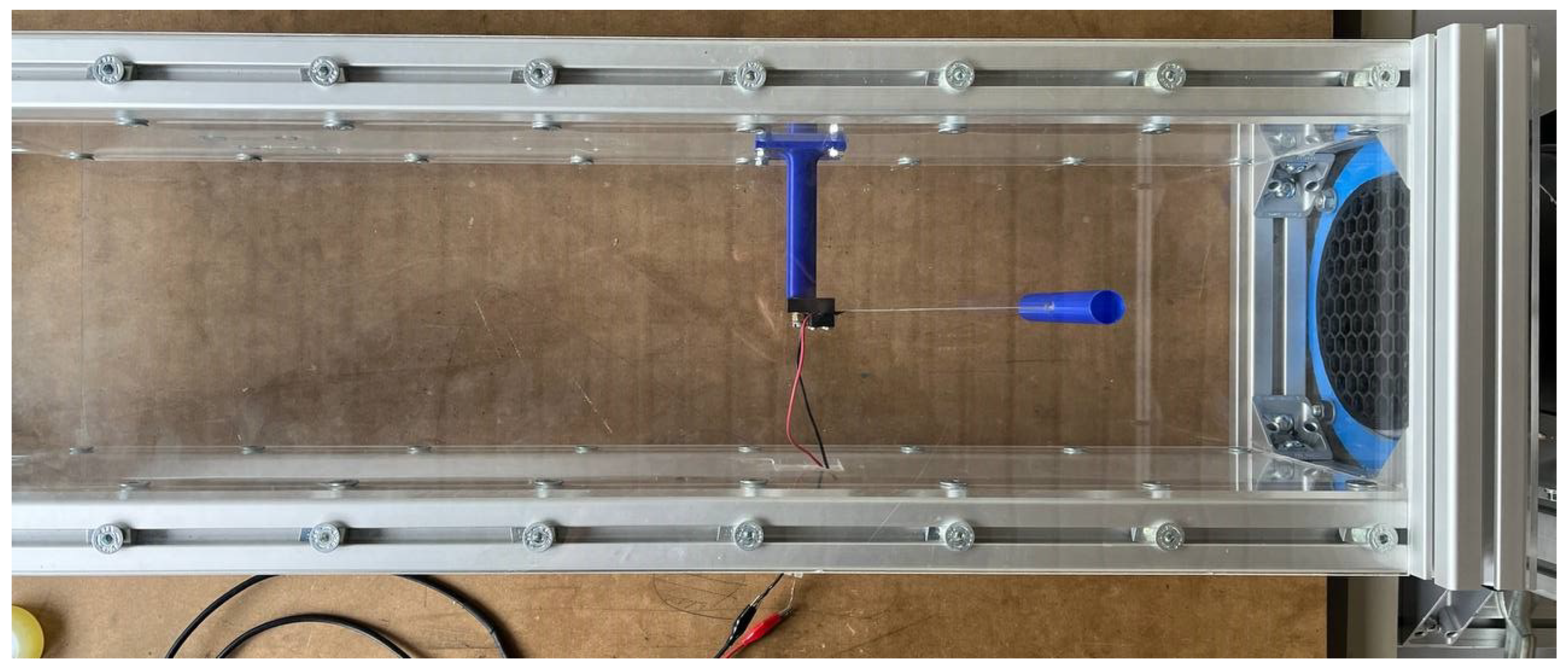

4.1. Experimental Equipment - Wind Tunnel

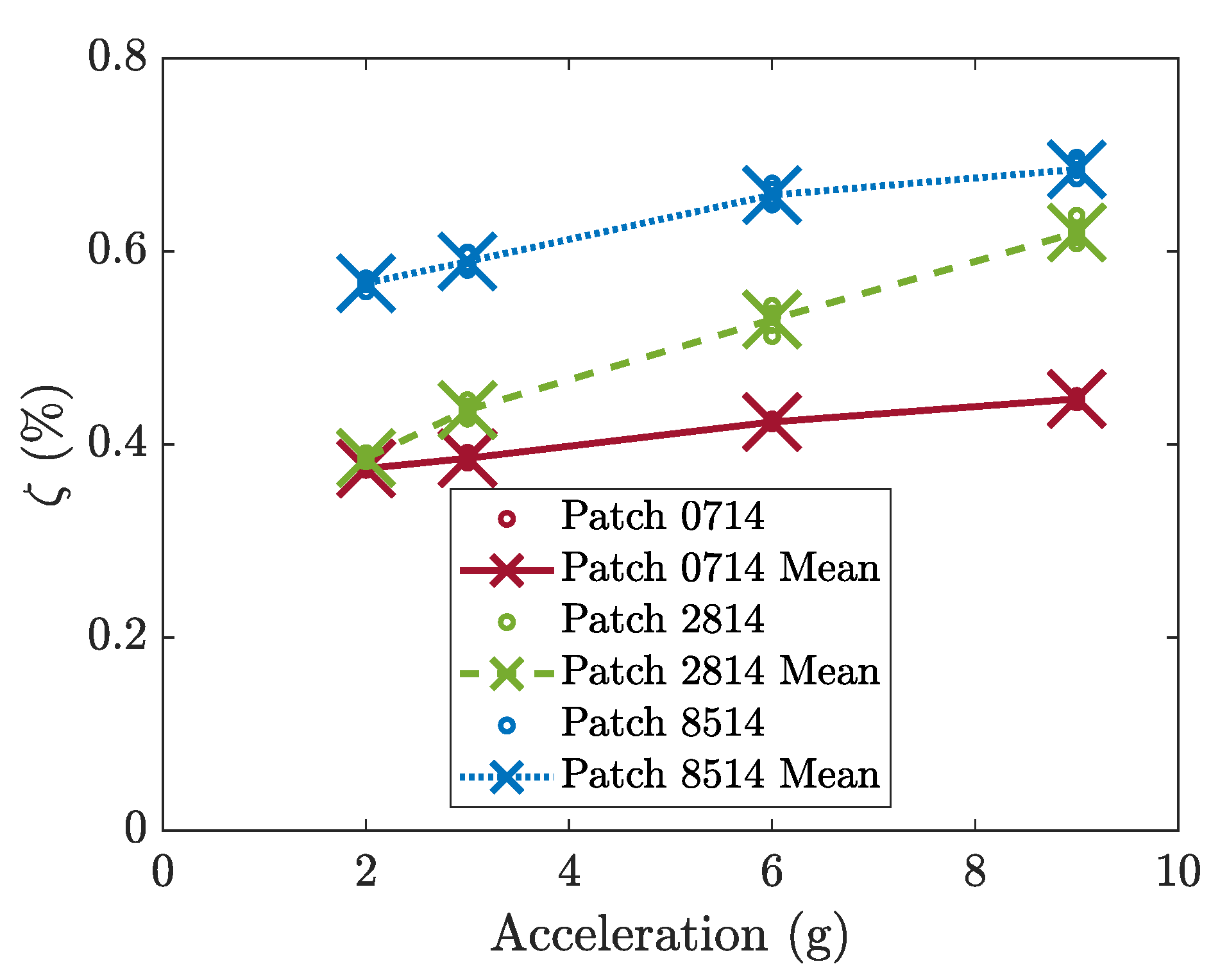

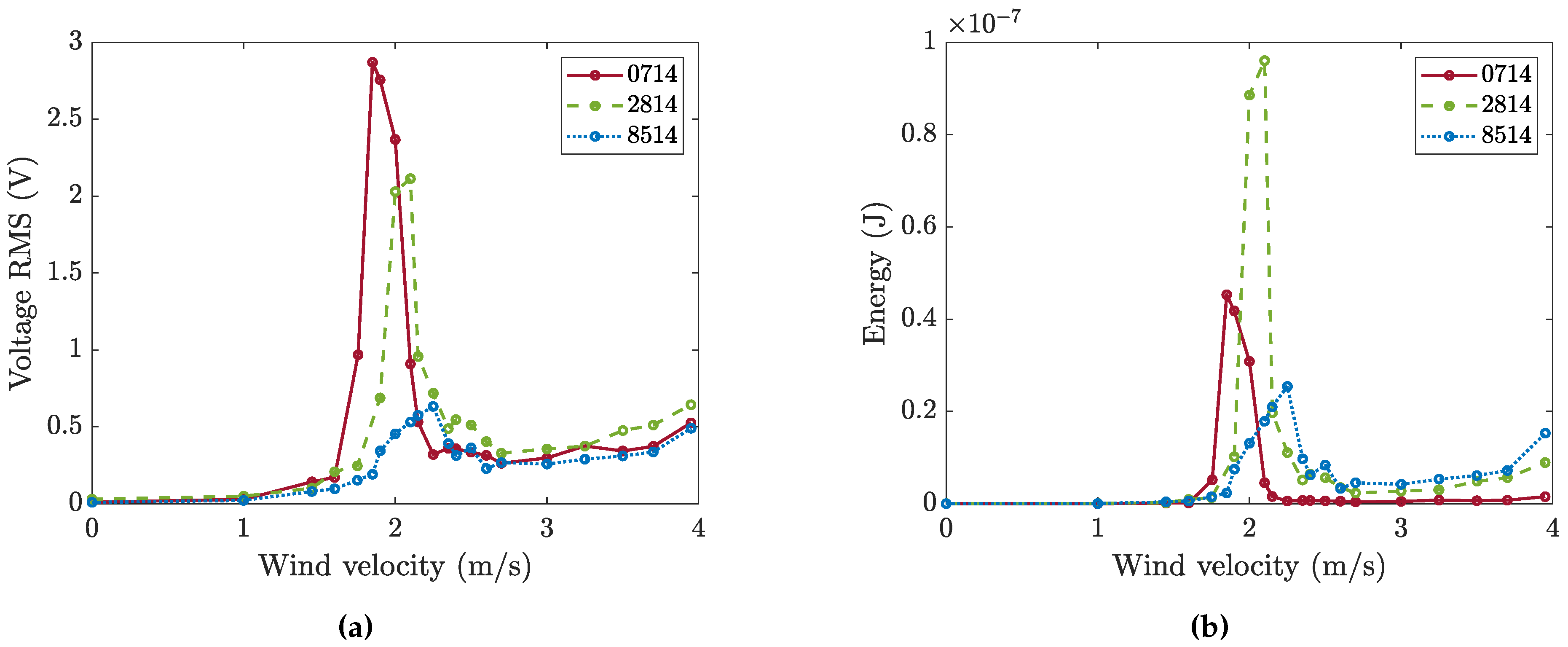

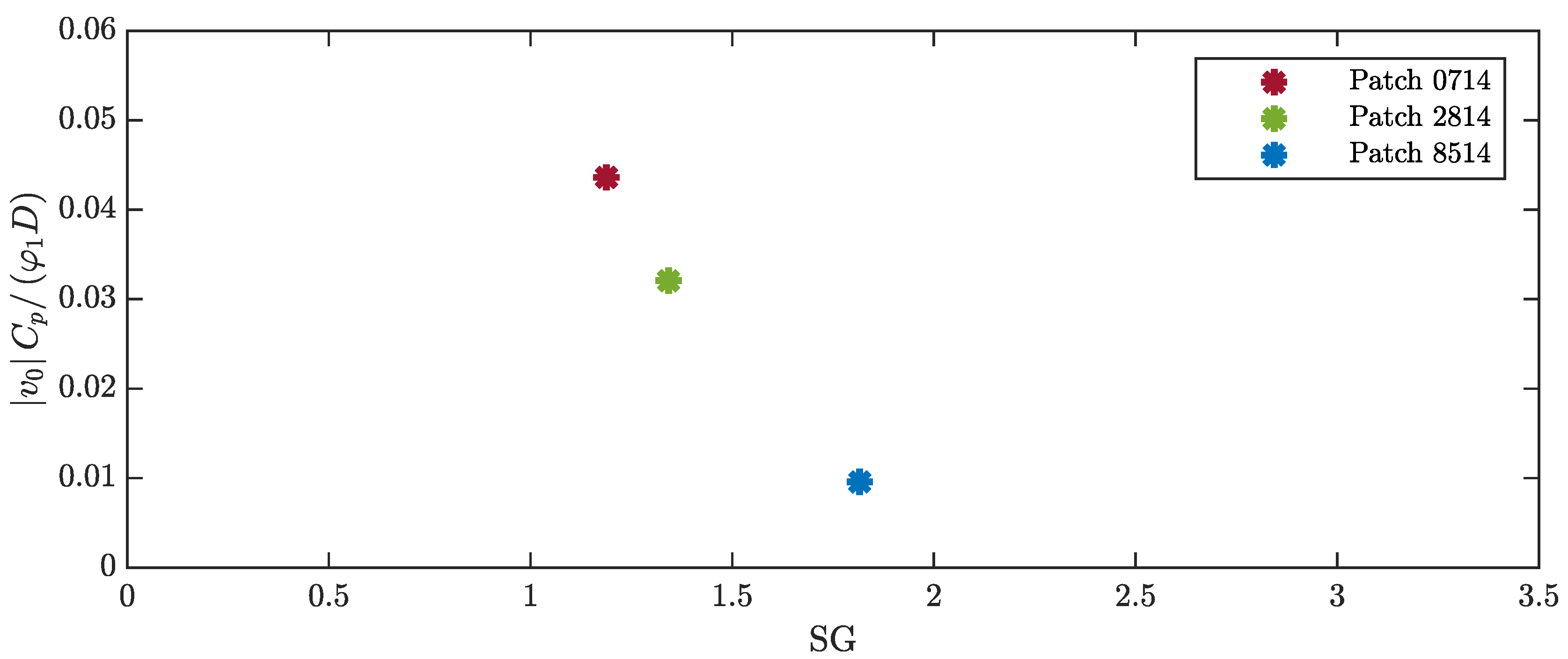

4.2. Effect of Patch Length

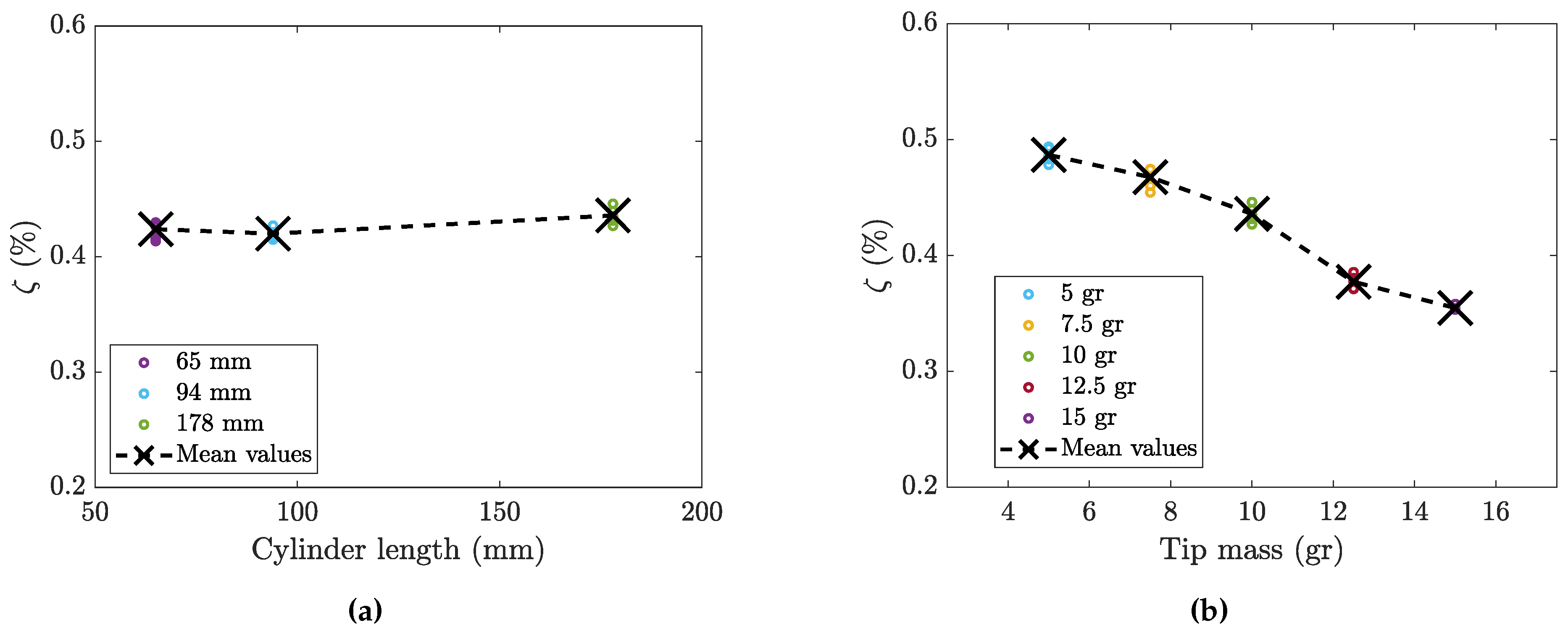

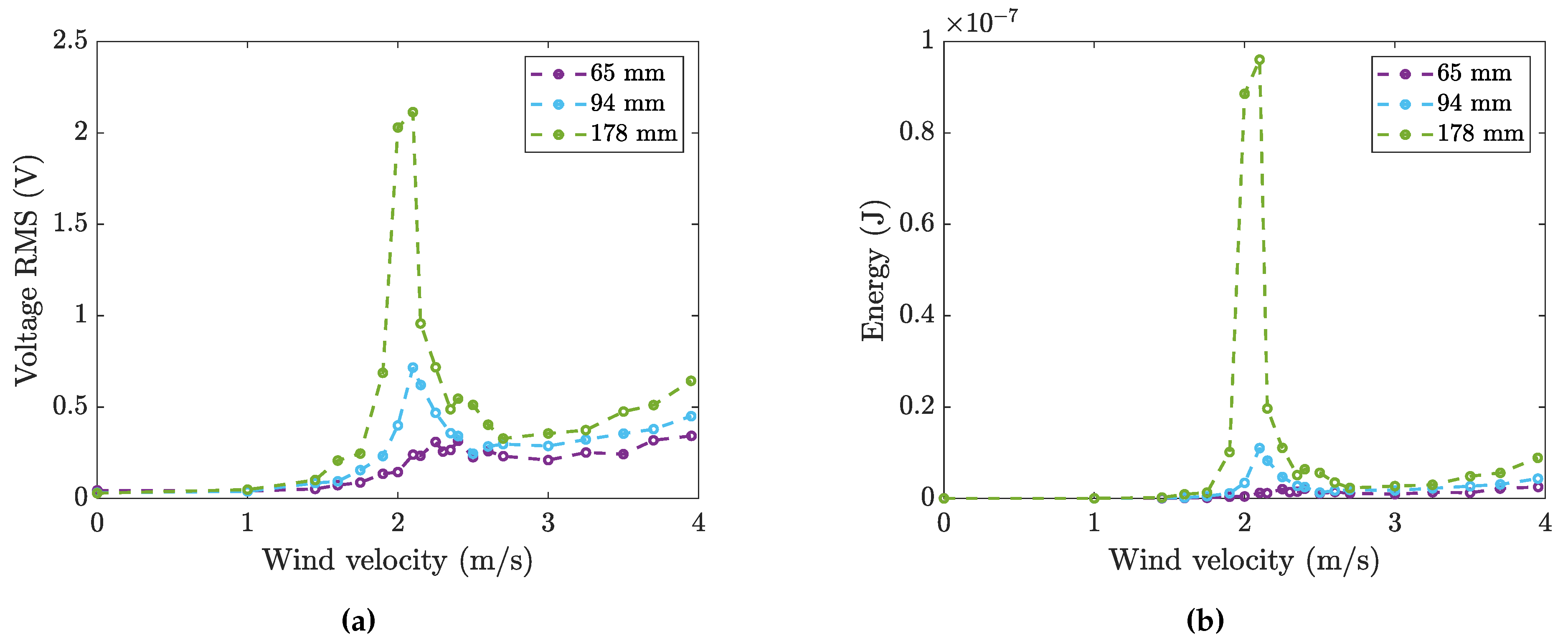

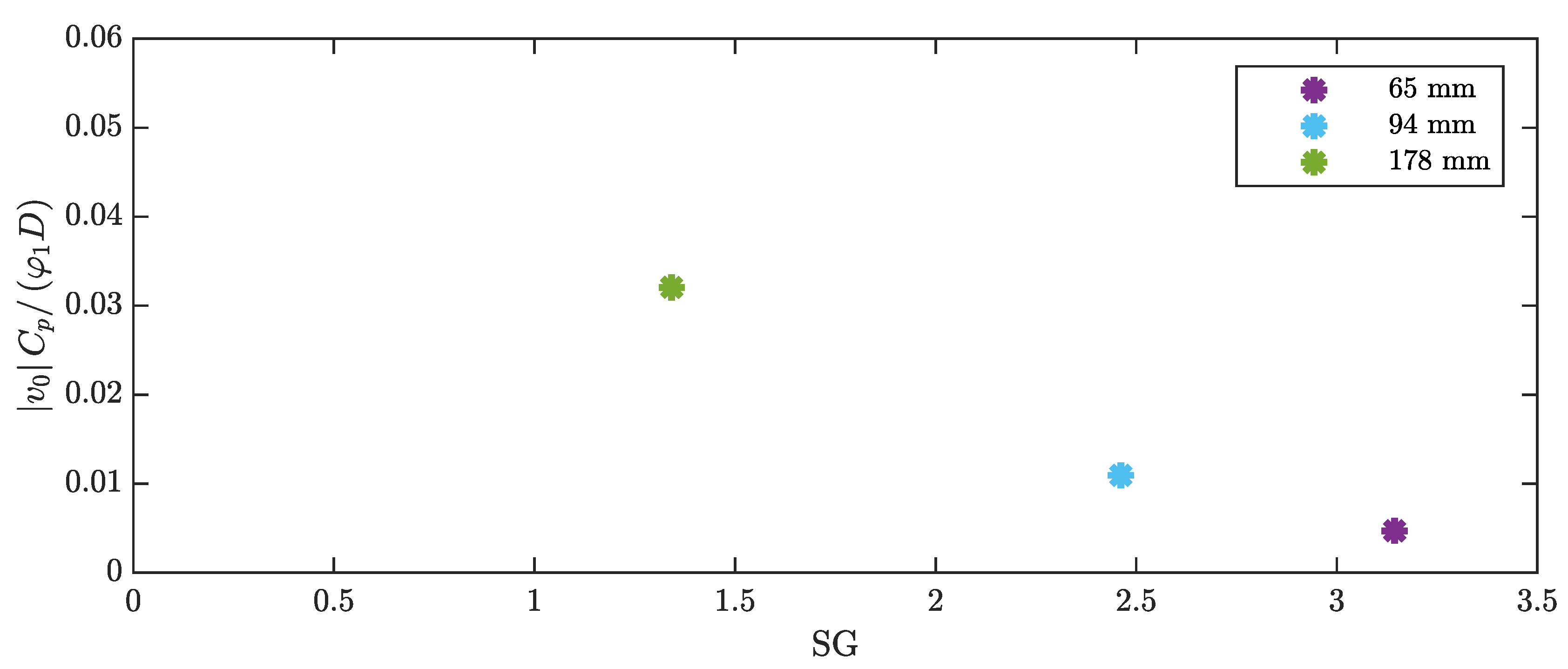

4.3. Effect of Cylinder Length

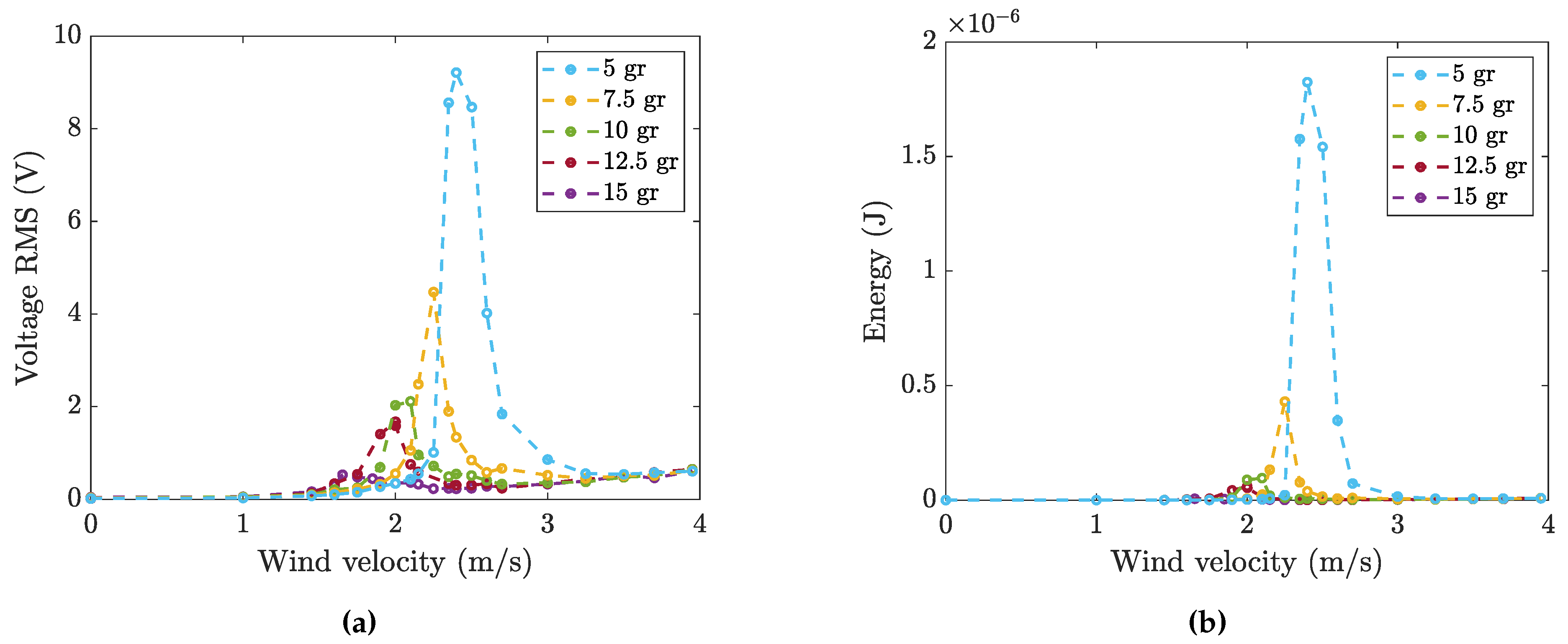

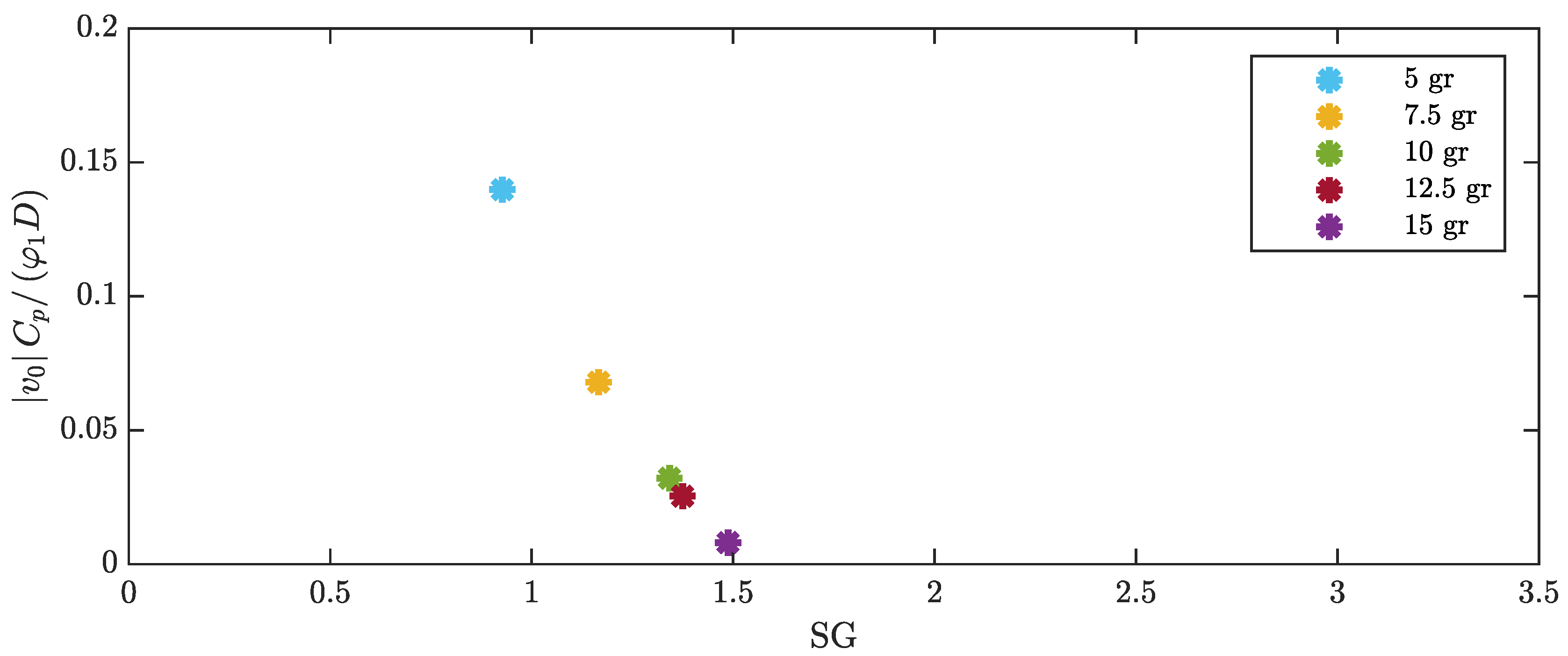

4.4. Effect of Cylinder Mass

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blevins, R.D. Flow-induced vibration; Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, 1977.

- Matsumoto, M. VORTEX SHEDDING OF BLUFF BODIES: A REVIEW. Journal of Fluids and Structures 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assi, G.; Bearman, P.; Kitney, N. Low drag solutions for suppressing vortex-induced vibration of circular cylinders. Journal of Fluids and Structures 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadeh-Ranjbar, V.; Elvin, N.; Andreopoulos, Y. Vortex-induced vibration of finite-length circular cylinders with spanwise free-ends: Broadening the lock-in envelope. Physics of Fluids 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalak, A.; Williamson, C. MOTIONS, FORCES AND MODE TRANSITIONS IN VORTEX-INDUCED VIBRATIONS AT LOW MASS-DAMPING. Journal of Fluids and Structures 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, I.; Scanlan, R.; Jones, N. Vortex-induced vibration of circular cylinders. I: Experimental data. Journal of Engineering Mechanics. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Geng, L.; Ding, L.; Zhu, H.; Yurchenko, D. The state-of-the-art review on energy harvesting from flow-induced vibrations. Applied Energy 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukymbekov, D.; Saymbetov, A.; Nurgaliyev, M.; Kuttybay, N.; Dosymbetova, G.; Svanbayev, Y. Intelligent autonomous street lighting system based on weather forecast using LSTM. Energy 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Ma, S.; Tao, P.; Pei, W.; Liu, Y.; Tao, L.; Wu, Y. A Wind-Solar Hybrid Energy Harvesting Approach Based on Wind-Induced Vibration Structure Applied in Smart Agriculture. Micromachines 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doria, A.; Fanti, G.; Filipi, G.; Moro, F. Development of a novel piezoelectric harvester excited by raindrops. Sensors (Switzerland) 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaydin, H.; Elvin, N.; Andreopoulos, Y. The performance of a self-excited fluidic energy harvester. Smart Materials and Structures 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Abdelkefi, A.; Wang, L. Theoretical modeling and nonlinear analysis of piezoelectric energy harvesting from vortex-induced vibrations. Journal of Intelligent Material Systems and Structures 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Hu, X.; Tan, T.; Yan, Z.; Zhang, W. Piezoelectric galloping energy harvesting enhanced by topological equivalent aerodynamic design. Energy Conversion and Management 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, W. Optimization of galloping piezoelectric energy harvester with V-shaped groove in low wind speed. Energies 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orrego, S.; Shoele, K.; Ruas, A.; Doran, K.; Caggiano, B.; Mittal, R.; Kang, S. Harvesting ambient wind energy with an inverted piezoelectric flag. Applied Energy 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobeck, J.; Inman, D. Artificial piezoelectric grass for energy harvesting from turbulence-induced vibration. Smart Materials and Structures 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, G.; Wang, J.; Yang, K.; Yurchenko, D. A hybrid piezo-dielectric wind energy harvester for high-performance vortex-induced vibration energy harvesting. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Abdelkefi, A.; Yang, Y.; Wang, L. Orientation of bluff body for designing efficient energy harvesters from vortex-induced vibrations. Applied Physics Letters 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fershalov, A.; Albano, J.; Orlandini, P.; Elvin, N.; Liu, Y. HARVESTING SUSTAINABLE ENERGY THROUGH VORTEX-INDUCED CYLINDER VIBRATIONS. 2024, Vol. 1. [CrossRef]

- Boddapati, K.; Arrieta, A.F. Structural multistability for multi-speed wind energy harvesting from vortex-induced vibrations. Smart Materials and Structures 2024, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchinetti, M.; de Langre, E.; Biolley, F. Coupling of structure and wake oscillators in vortex-induced vibrations. Journal of Fluids and Structures 2004, 19, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaydin, H.D.; Elvin, N.; Andreopoulos, Y. Experimental study of a self-excited piezoelectric energy harvester. 2010, Vol. 1, p. 179 – 185.

- Mehmood, A.; Abdelkefi, A.; Hajj, M.; Nayfeh, A.; Akhtar, I.; Nuhait, A. Piezoelectric energy harvesting from vortex-induced vibrations of circular cylinder. Journal of Sound and Vibration 2013, 332, 4656–4667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Home of the MFC. https://www.smart-material.com/MFC-product-mainV2.html. accessed on. 25 November.

- Erturk, A.; Inman, D. On Mechanical Modeling of Cantilevered Piezoelectric Vibration Energy Harvesters. Journal of Intelligent Material Systems and Structures 2008, 19, 1311–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erturk, A.; Inman, D.J. A Distributed Parameter Electromechanical Model for Cantilevered Piezoelectric Energy Harvesters. Journal of Vibration and Acoustics 2008, 130, 041002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasetto, A.; Tonan, M.; Doria, A. Development of a Hybrid Harvester for Collecting Energy From Wind and Vibrations in Light Vehicles. 2024, Vol. Volume 1: 26th International Conference on Advanced Vehicle Technologies (AVT), International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference, p. V001T01A012. [CrossRef]

- Erturk, A.; Inman, D. Piezoelectric Energy Harvesting; John Wiley and Sons, Ltd, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Doria, A.; Marconi, E.; Moro, F. Energy Harvesting from Bicycle Vibrations by Means of Tuned Piezoelectric Generators. Electronics 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, D.J. Introduction to Electrodynamics, 5 ed.; Cambridge University Press, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Bearman, P.W. Vortex shedding from oscillating bluff bodies. Annual review of fluid mechanics 1984, 16, 195–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, C.H.; Govardhan, R. Vortex-induced vibrations. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2004, 36, 413–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tommasino, D.; Tonan, M.; Moro, F.; Doria, A. Identification of the Piezoelectric Properties of Materials From Impulsive Tests on Cantilever Harvesters. 2023, Vol. Volume 12: 35th Conference on Mechanical Vibration and Sound (VIB), International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference, p. V012T12A005. [CrossRef]

- Unal, M.; Rockwell, D. On vortex formation from a cylinder. Part 2. Control by splitter-plate interference. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 1988, 190, 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Patch 0714 | Patch 2814 | Patch 8514 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hz) | 16.0 | 16.8 | 19.2 |

| 0.45 | 0.62 | 0.68 |

| Cylinder Length | 65 mm | 94 mm | 178 mm |

|---|---|---|---|

| AR | 3.4 | 5.0 | 9.4 |

| 0.32 | 0.22 | 0.12 | |

| mass ratio | ∼570 | ∼430 | ∼210 |

| Cylinder Mass | 5 gr | 7.5 gr | 10 gr | 12.5 gr | 15 gr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Hz) | 20.7 | 18.1 | 16.8 | 15.1 | 14.1 |

| mass ratio | ∼130 | ∼170 | ∼210 | ∼250 | ∼290 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).