Introduction

Wild-type Dictyostelium discoideum are obligate phagocytes that rely on the uptake of bacteria (food particles) for growth. Bacteria are engulfed through the formation of a phagocytic cup, a process that involves dynamic reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton and directed vesicle movement. In contrast, fluid-phase endocytosis (pinocytosis) allows the uptake of soluble extracellular components in large quantities. This process begins at the plasma membrane, mediated by either clathrin-coated or non-coated vesicles, and progresses through early and late endosome formation before the contents are transported to lysosomes. Subsequently, the processed materials are expelled back into the external medium via the plasma membrane.

Our studies reveal that the xanthine alkaloid caffeine impacts the “mechanistic Target of Rapamycin Complexes” (mTORC1 and mTORC2) in

Dictyostelium, where mTOR acts as a shared component of both complexes. mTORC1 plays a pivotal role in controlling cell growth, and growth to -developmental switch [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5], while mTORC2 is essential for regulating cell polarization and chemotaxis [

6,

7,

8,

9]. mTORC2 also facilitates actin assembly, which is critical for nutrient uptake (Rosel et al., 2012). Notably, inhibiting mTORC1 by nutrient depletion or genetic ablation of Raptor (a mTORC1 component), or short-term rapamycin treatment does not affect phagocytosis [

3]. In contrast, the loss of mTORC2 components, including Rictor/Pia, SIN1/RIP3, and Lst8, significantly enhances nutrient uptake by increasing phagocytosis [

3]. Moreover, macropinocytosis, an AKT-dependent mechanism for fluid-phase nutrient uptake, is independent of both mTORC1 and mTORC2 [

3].

Caffeine has been shown to influence cell growth and development by modulating mTORC1 and mTORC2 activity [

10,

11,

12,

13]. In

Dictyostelium, caffeine or adenosine-mediated inhibition of mTORC1 and mTORC2 activity may similarly disrupt the uptake of food particles and fluids. Additionally, caffeine is known to inhibit fluid uptake by increasing cytosolic Ca²⁺ levels, which disrupts vesicular trafficking associated with endocytosis [

14]. In macrophages, adenosine inhibits phagocytosis, potentially through cAMP signaling [

15]. Conversely, in mice, adenosine administration has been associated with increased pinocytic activity [

16]. Notably, the inhibition of endocytosis by caffeine is reversible upon drug removal and can be partially mitigated by 10 mM adenosine [

14].

To investigate this, we measured phagocytosis by analyzing the uptake of 1 µm fluorescently labeled particles and assessed fluid-phase uptake using FITC-dextran in the presence and absence of caffeine and adenosine. Experiments were conducted using wild-type Dictyostelium cells as well as cells with mutations in rip-3 and lst-8, components of the mTOR complexes.

Results

Caffeine Inhibits mTORC2, Leading to Increased Phagocytosis and Reduced Fluid Uptake

Dictyostelium cells acquire nutrients through both phagocytosis and pinocytosis. While caffeine is known to influence cell growth and development by modulating the activity of mTORC1 and mTORC2, its impact on pinocytosis and phagocytosis via these complexes remains unclear.

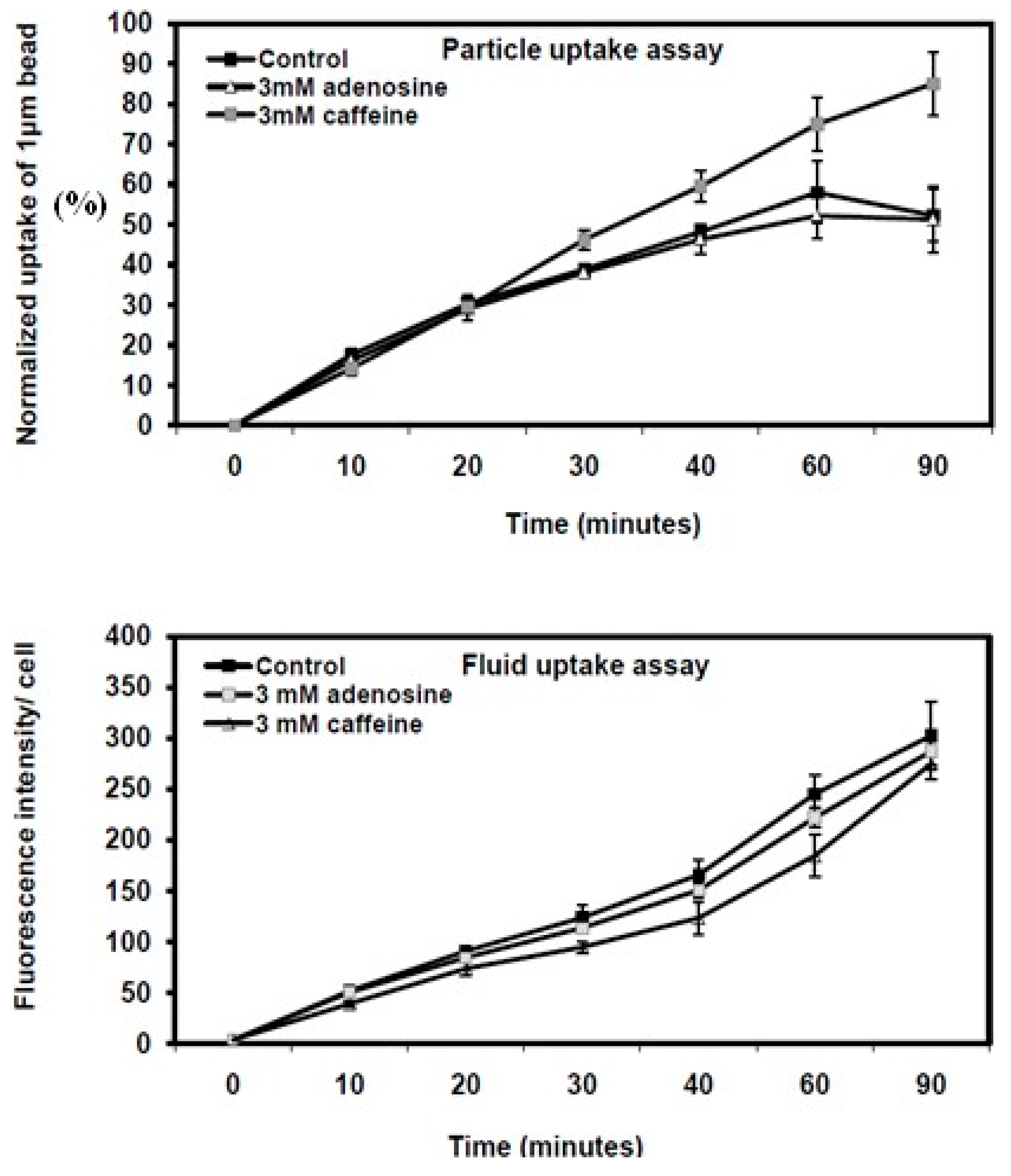

To investigate this, we measured phagocytic activity during growth by assessing the uptake rate of 1 μm fluorescently labeled particles in the presence of caffeine and adenosine over specific incubation periods. Caffeine treatment resulted in an increase in phagocytic activity, whereas adenosine had no effect (

Figure 1). In caffeine-treated cells, the particle uptake rate accelerated after 20 minutes of incubation and continued to increase logarithmically over time. In contrast, control cells exhibited a decline in uptake rate after 60 minutes (

Figure 1).

Fluid-phase pinocytosis kinetics were analyzed in growth media containing caffeine or adenosine using FITC-dextran as a marker dye. Caffeine markedly inhibited fluid-phase pinocytosis, with a noticeable reduction in FITC-dextran uptake after 10 minutes that progressively decelerated (

Figure 1). Adenosine caused only a slight decrease in uptake after 20 minutes, with subsequent reductions being minimal and comparable to untreated controls (

Figure 1). While adenosine promotes cell growth, it does not significantly alter phagocytosis or pinocytosis kinetics. The observed changes in phagocytosis and pinocytosis in the presence of caffeine may result from the inactivation of mTOR complexes.

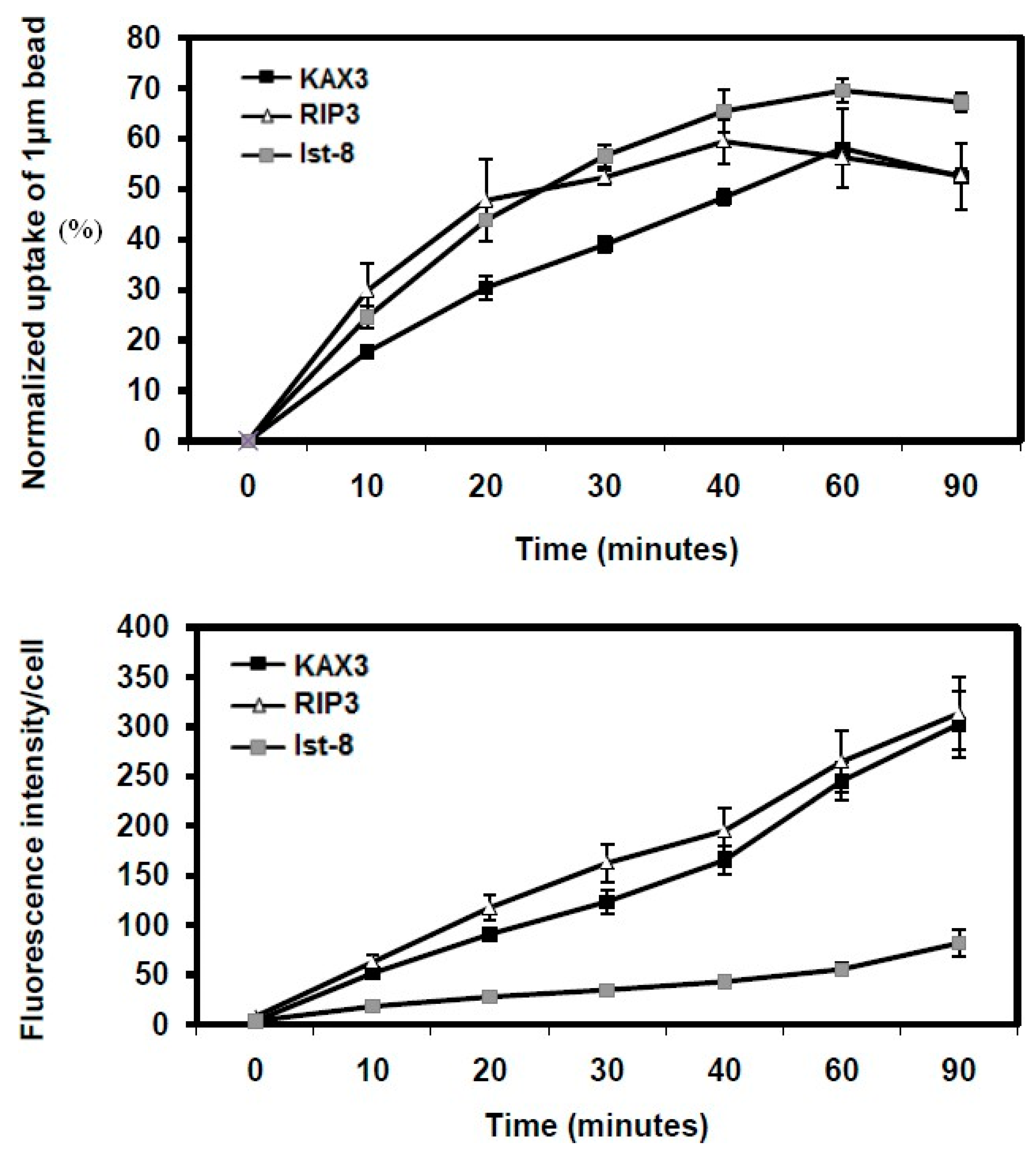

To investigate whether caffeine alters particle or fluid uptake by inactivating mTORC1 or mTORC2, we analyzed phagocytosis and fluid-phase pinocytosis kinetics in

Dictyostelium wild-type KAX3 cells and mutant cells with disruptions in mTOR complex components: RIP3 (specific to mTORC2) and Lst8 (shared by mTORC1 and mTORC2). Notably, both phagocytosis and pinocytosis rates were elevated in

rip3- cells compared to their parental KAX3 cells (

Figure 2). Additionally, the particle uptake rate in

lst8- cells was even higher than that observed in

rip3- and control cells (

Figure 2).

In contrast, the pinocytosis rate was significantly reduced in

lst8- cells (

Figure 2). The phagocytosis kinetics of

lst8- and

rip3- cells resembled those of

Dictyostelium wild-type KAX3 cells treated with caffeine (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). The inactivation of mTORC2, either through the loss of its components RIP3 or Lst8 or by caffeine treatment, led to increased particle uptake. The enhanced phagocytosis observed in wild-type cells, as well as in

rip3- and

lst8- cells treated with caffeine, highlights the role of mTORC2 in regulating endocytosis.

The reduced fluid uptake rate in

lst8- cells (

Figure 2) and caffeine-treated wild-type KAX3 cells (

Figure 1), contrasted with the increased fluid uptake rate in

rip3- cells (

Figure 2), suggests that fluid-phase pinocytosis may be independently regulated by mTORC1 and genes upstream of the mTORC2 complex.

Loss of mTORC2 Components Confers Resistance to Caffeine

As demonstrated in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, caffeine increases phagocytosis while reducing pinocytosis rates. Similarly, mutants lacking mTORC2 components exhibited increased phagocytosis and decreased pinocytosis, except for

rip3- cells, which showed higher fluid-phase kinetics compared to wild-type cells. To further explore endocytosis, we examined

lst8-and

rip3- cells following caffeine and adenosine treatment.

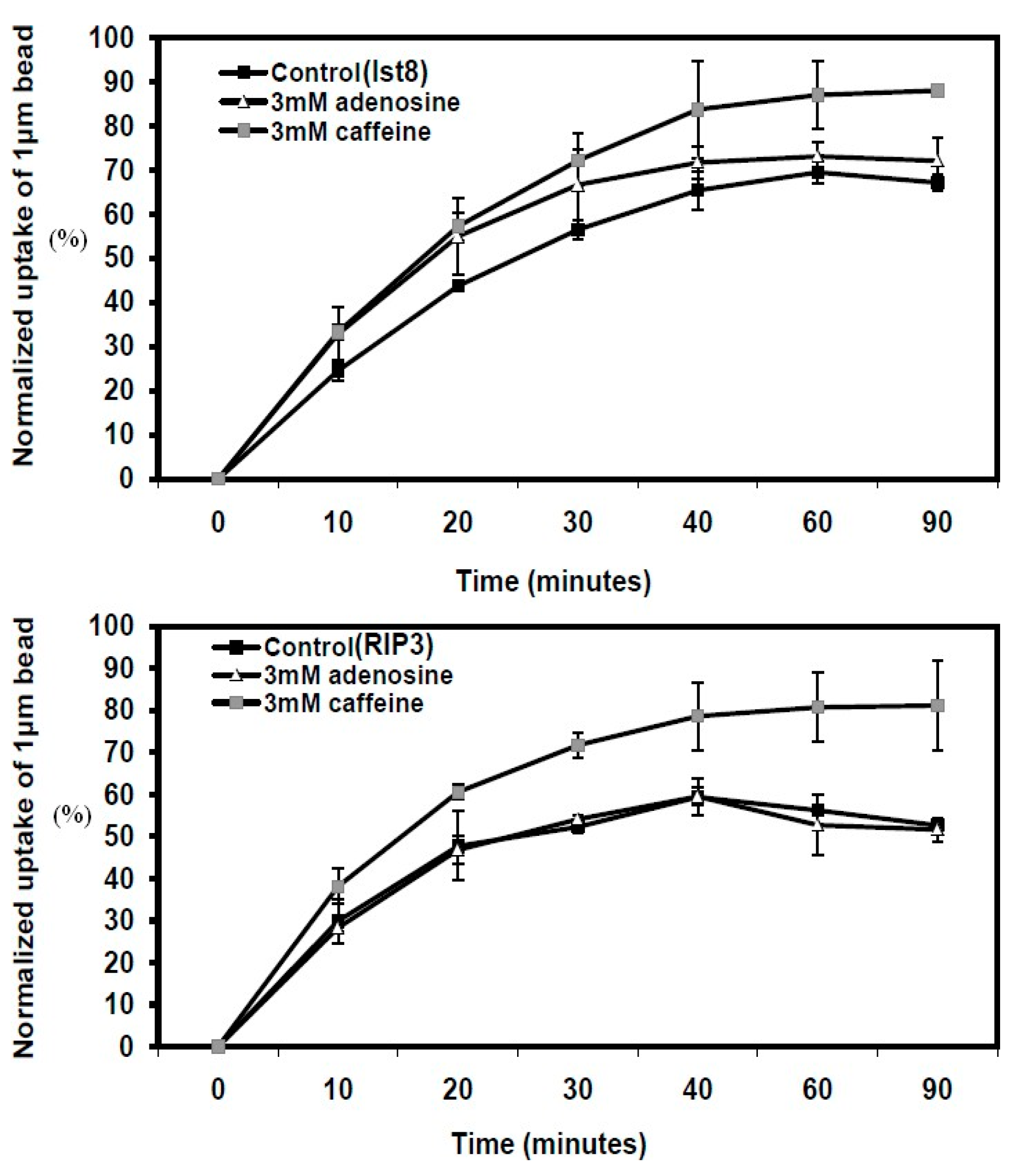

Both

lst8- and

rip3- cells displayed insensitivity to caffeine (

Figure 3). The particle uptake kinetics of these mutants in the presence of caffeine were similar to those of wild-type KAX3 cells under caffeine treatment (

Figure 3). Treatment with adenosine led to a slight increase in particle uptake in

lst8- cells compared to controls, while

rip3- cells showed no change (

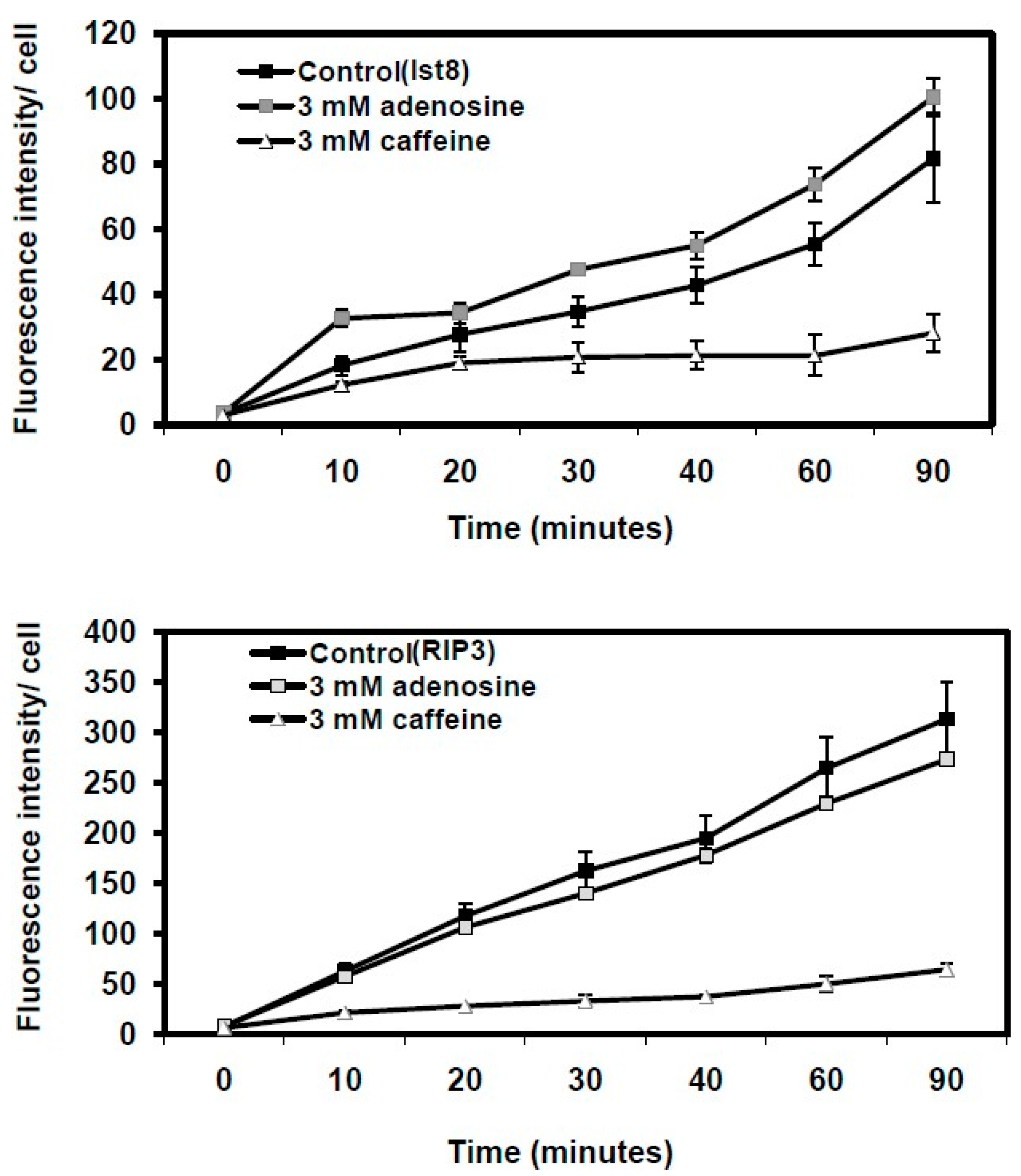

Figure 1). However, caffeine treatment significantly reduced fluid uptake in both

lst8- and

rip3- cells. Notably, fluid uptake in these mutants under caffeine treatment remained higher than that of parental KAX3 cells (

Figure 4). In the presence of adenosine, particle uptake in both mutants decreased marginally, mirroring the response of KAX3 cells treated with adenosine.

The resistance of lst8- and rip3- cells to caffeine confirms that mTORC2 is a target of caffeine and plays a role in regulating phagocytosis. The pronounced effect of caffeine on fluid uptake in lst8- and rip3- cells suggests that pinocytosis is not directly governed by mTORC2 but may be influenced by upstream gene products regulated by mTORC2. These findings also confirm that adenosine does not affect particle or fluid uptake, indicating that its growth-promoting effects are unrelated to nutrient uptake mechanisms.

Caffeine's Target Binding Sites in mTOR Kinases of mTORC1 and mTORC2

The mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) in

Dictyostelium encodes a protein of 2380 amino acids (MW-268KD). The software program SMART (Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool-

http://smart.embl heidelberg.de/smart) predicted two catalytic sites in mTOR protein, namely, FRB (FKBP12-rapamycin binding domain) and PI3Kc kinase domain at 99 and 286 amino acids respectively. The remaining amino acids were predicted to be internal repeats, heat repeat FAT and FATc domains. In mammals, studies show that caffeine inhibits mTOR activity (IC

50 = 0.4 mm) by directly acting on phosphatidylinositol 3- kinase domain (PI3Kc) [

17]. Caffeine is known to induce apoptosis by enhancing autophagy by inhibiting PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway [

18]. Phosphorylation of Akt

S473 by mTORC2 (mTOR-Rictor complex) is caffeine sensitive. In yeast cells, m

TORC1 pathway is an important target of caffeine. Single mutations in these domains are less resistant to caffeine than double mutations, one in FRB domain and another in PI3Kc kinase domain [

13]. Rapamycin, an immunosuppressant drug binds to FRB domain of mTOR and when it complexes with FK506 binding protein (FKBP12), mTOR kinase activity is impaired. Caffeine may also bind to FRB domain like rapamycin and decrease the kinase activity as both caffeine and rapamycin alters the expression levels of identical set of genes in yeast.

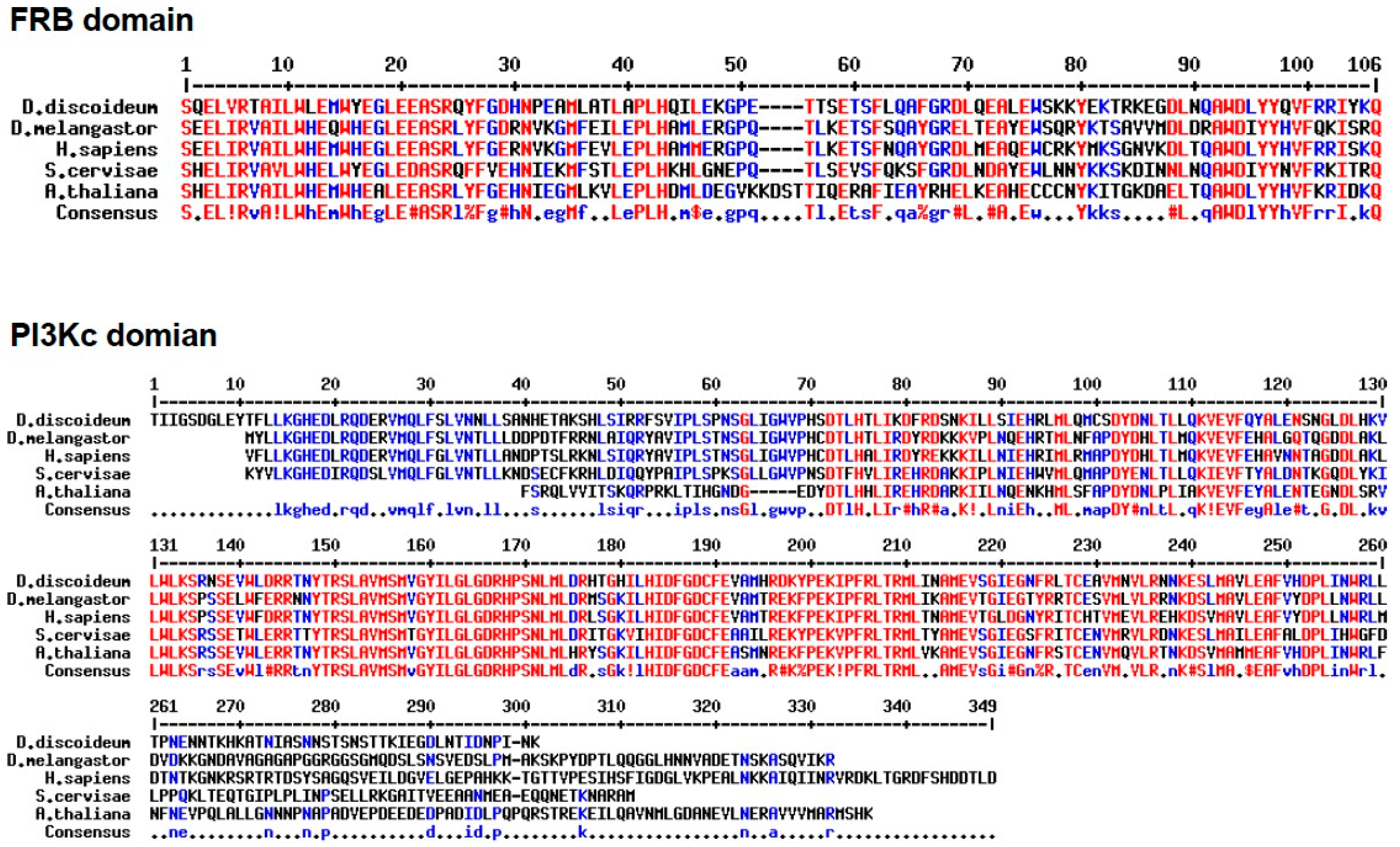

The PI3Kc kinase domain of mTOR in

Dictyostelium shares strong sequence similarity with human orthologues (63 %), 61 % similarity with flies, 59 % similarity with yeast and 53% with plants (

Figure 5,

Table 1). Amino acid sequence alignment of FRB domain of mTOR of

D. discoideum, shows high sequence similarity with

Arabidopsis thaliana (plant) 55%,

Homo sapiens (human) 63 %,

Drosophila melanogaster (fly) 57% and

Saccharomyces cerevisiae (yeast) 56 % (

Figure 5,

Table 2). Based on sequence similarity of PI3Kc and FRB domains of

Dictyostelium mTOR and other organisms, it is hypothesized that caffeine could possibly bind to these domains in slime molds as well. Since mTOR unit of

Dictyostelium is common in both mTOR complexes (mTORC1 and mTORC2; [

3]) caffeine by inhibiting mTOR kinase activity, could possibly alter the activity of both the mTOR complexes.

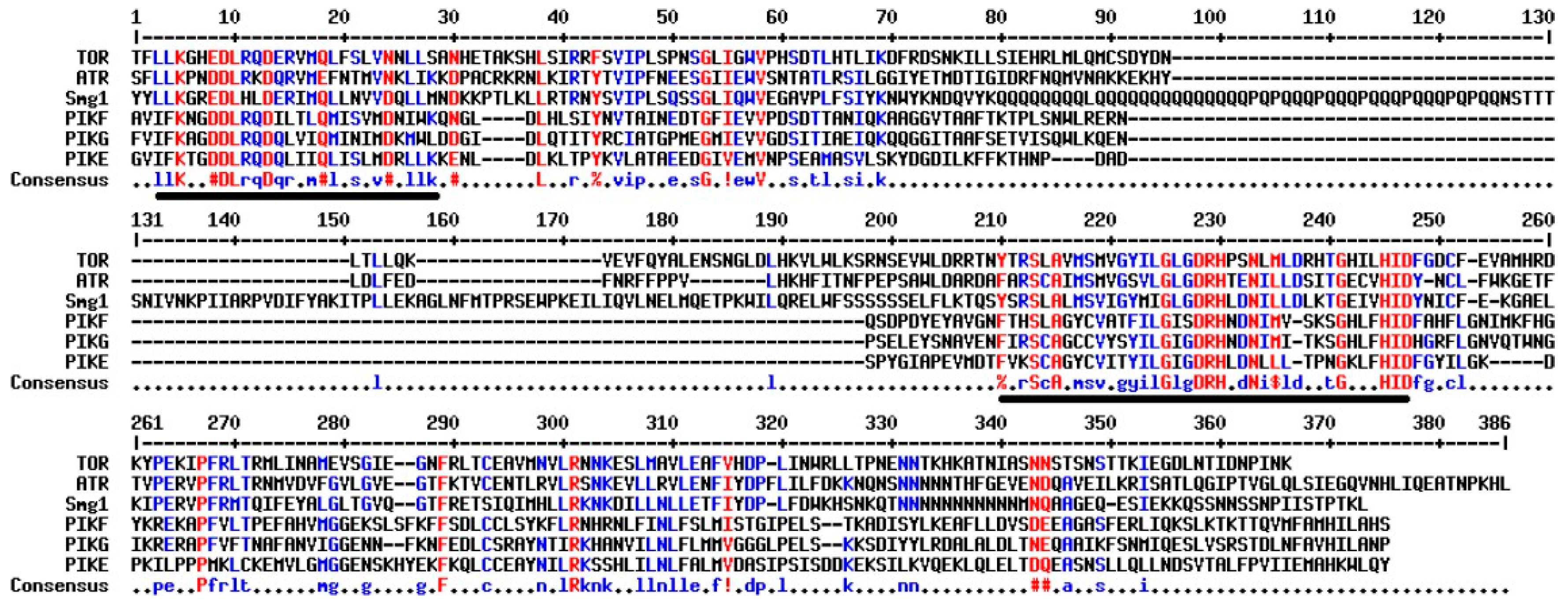

The PI3k kinase domain of the

Dictyostelium has high similarity with the kinase of the genes involved in DNA repair mechanism and PI3k signal cascade. For example, ATR, smg-1 and PckDNA (involved in DNA repair) [

19], PikD, PikF and PikE (development, [

20] have strong sequence similarity to the PI3k kinase domain of mTOR (

Figure 6). Thus, besides TOR caffeine could also possibly act on other kinases mentioned earlier carrying PI3Kc domain.

Discussion

The mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathways play crucial roles in regulating cell growth, nutrient sensing, and endocytic processes. mTORC1 is known to promote growth in response to nutrient availability [

21], while mTORC2 regulates processes such as cytoskeletal organization and endocytosis independently of mTORC1 [

3]. This study investigates the effects of caffeine on nutrient uptake via phagocytosis and pinocytosis in

Dictyostelium, shedding light on the differential regulation of these processes by mTORC1 and mTORC2.

Our findings reveal that caffeine significantly enhances phagocytosis while inhibiting fluid-phase pinocytosis. The observed increase in phagocytosis in wild-type cells treated with caffeine, as well as in lst8- and rip3- cells, strongly supports the role of mTORC2 in suppressing phagocytic activity under normal conditions. Caffeine’s inactivation of mTORC2 either directly or through associated pathways likely explains the increased particle uptake observed. Furthermore, the similarity in phagocytic kinetics between caffeine-treated wild-type cells and lst8- and rip3- cells highlights mTORC2 as a critical target of caffeine in regulating phagocytosis.

In contrast, fluid-phase pinocytosis appears to be regulated through a distinct mechanism involving both mTORC1 and mTORC2. Caffeine treatment significantly reduced fluid uptake in wild-type cells, suggesting its effect on both complexes. Interestingly,

lst8- cells showed a more pronounced decrease in pinocytosis compared to

rip3- cells, indicating that mTORC1 may play a more dominant role in this process. Additionally, the enhanced fluid uptake in

rip3- cells compared to wild-type cells further implies that pinocytosis involves mTORC1 and possibly other upstream regulators of mTORC2, such as phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3Ks) or AKT kinases [

3].

The effects of caffeine on endocytosis can also be due to its action on multiple targets, including PI3K-related kinases such as smg1, ATR, and DNA-PKcs [

22]. PI3Ks are key regulators of pinocytosis [

23], and their inhibition by caffeine could contribute to the observed reduction in fluid uptake. Additionally, increased cytosolic Ca

++ levels induced by caffeine [

14] may further impair pinocytosis.

Interestingly, adenosine treatment had no significant impact on phagocytosis or pinocytosis in wild-type or mutant cells, even though it is known to promote growth. This suggests that adenosine enhances cell growth through mechanisms independent of endocytosis.

In conclusion, our study highlights the critical role of mTORC2 in regulating phagocytosis and provides evidence for the involvement of both mTORC1 and mTORC2 in fluid-phase pinocytosis. Caffeine’s ability to modulate these pathways underscores its value as a tool for dissecting mTOR signaling. The resistance of lst8- and rip3- cells to caffeine further validates mTORC2 as a primary target. These findings advance our understanding of nutrient uptake mechanisms in Dictyostelium and offer a framework for exploring the broader implications of mTOR signaling in cellular processes.

In the future, the effects of caffeine on secreted factors, such as the regulation of DPF1 [

24] and its impact on multicellular development through regulated endocytosis, can be investigated. Additionally, the influence of caffeine on innate immunity during Salmonella infection, mediated through the cGAS and RIG-I pathways [

25,

26], can also be explored.

Material and Methods

Cell Culture

KAX3

Dictyostelium cells were cultured in Cosson HL5 medium, composed of 14.3 g/L bactopeptone, 7.15 g/L yeast extract, 18 g/L maltose monohydrate, and 3.6 mM Na

2HPO

4/KH

2PO4 buffer, supplemented with penicillin (100 U/mL) and streptomycin (100 μg/mL) to prevent bacterial contamination. The cells were maintained at 22°C, either in petri dishes or shaking suspension at 150 rpm, following previously described protocols [

11,

27].

For lst8‾ and rip3‾ mutant cells, the culture medium was supplemented with 5 μg/mL blasticidin alongside penicillin and streptomycin (at the same concentrations as above) to ensure the selection of mutants and prevent bacterial contamination.

Flow Cytometry-Based Uptake Assay (Phagocytosis/Pinocytosis)

To evaluate particle or fluid uptake rates, KAX3 Dictyostelium cells were cultured in growth medium until they reached 80% confluency. Two hours before the experiment, cells were harvested, and 1 × 107 cells were resuspended in 5 mL of growth medium in a six-well plate. The plate was placed on a platform shaker set at 150 rpm. To assess the effects of caffeine and adenosine, 3 mM of either compound was added to the growth medium.

For measuring particle uptake, 1 μm size fluorescent beads (2 × 109; Fluoresbrite® YG 1-micron microspheres, Polysciences, Inc.) were washed with growth medium and briefly sonicated to create a uniform suspension. FITC-dextran was used to quantify fluid uptake.

Before adding beads or FITC-dextran, 0.5 mL of cells (1 × 106) were harvested to serve as baseline samples for subsequent time points. At time zero, the fluorescent beads or FITC-dextran were added to the remaining cell suspension, which was then incubated at room temperature with constant shaking at 120 rpm. At each time point, 0.5 mL of the cell suspension was collected, and uptake was stopped by placing the cells in ice-cold Sorensen’s buffer (120 mM sorbitol, 5 mM sodium azide) and storing them on ice. Cells were centrifuged at 1,500 rpm for 5 minutes at 4°C, resuspended in 0.5 mL of ice-cold Sorensen’s buffer containing 120 mM sorbitol, and analyzed immediately.

Fluorescence was measured using a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson™, USA), with data acquired from 20,000 events per time point. Histograms of fluorescence intensity versus event counts were analyzed to calculate mean fluorescence. The accuracy of the assay was validated by confirming that the initial uptake rate was proportional to the starting concentration of beads over a broad range.

To quantify bead uptake, we used the following formula:

References

- Jaiswal, P.; Majithia, A.R.; Rosel, D.; Liao, X.H.; Khurana, T.; Kimmel, A.R. Integrated actions of mTOR complexes 1 and 2 for growth and development of Dictyostelium. Int J Dev Biol 2019, 63, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaiswal, P.; Kimmel, A.R. mTORC1/AMPK responses define a core gene set for developmental cell fate switching. BMC Biol 2019, 17, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosel, D.; Khurana, T.; Majithia, A.; Huang, X.; Bhandari, R.; Kimmel, A.R. TOR complex 2 (TORC2) in Dictyostelium suppresses phagocytic nutrient capture independently of TORC1-mediated nutrient sensing. Journal of Cell Science 2012, 125, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaiswal, P. Caffeine and Rapamycin Impair Growth and Morphogenesis by Affecting Both TOR-Dependent Pathways in <em>Dictyostelium</em>. Preprints 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, P.K.; Kimmel, A.R. Nutrient/Starvation sensing for Reciprocal mTORC1/AMPK response in Dictyostelium, at the junction between Growth and Development. The FASEB Journal 2018, 32, lb141–lb141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Comer, F.I.; Sasaki, A.; McLeod, I.X.; Duong, Y.; Okumura, K.; Yates, J.R.; Parent, C.A.; Firtel, R.A. TOR Complex 2 Integrates Cell Movement during Chemotaxis and Signal Relay in Dictyostelium. Molecular Biology of the Cell 2005, 16, 4572–4583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamimura, Y.; Devreotes, P.N. Phosphoinositide-dependent Protein Kinase (PDK) Activity Regulates Phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-Trisphosphate-dependent and -independent Protein Kinase B Activation and Chemotaxis *<sup> </sup>. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2010, 285, 7938–7946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.-H.; Buggey, J.; Kimmel, A.R. Chemotactic activation of Dictyostelium AGC-family kinases AKT and PKBR1 requires separate but coordinated functions of PDK1 and TORC2. Journal of Cell Science 2010, 123, 983–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, P.; Meena, N.P.; Chang, F.S.; Liao, X.H.; Kim, L.; Kimmel, A.R. An integrated, cross-regulation pathway model involving activating/adaptive and feed-forward/feed-back loops for directed oscillatory cAMP signal-relay/response during the development of Dictyostelium. Front Cell Dev Biol 2023, 11, 1263316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, P.; Singh, S.P.; Aiyar, P.; Akkali, R.; Baskar, R. Regulation of multiple tip formation by caffeine in cellular slime molds. BMC Dev Biol 2012, 12, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, P.; Soldati, T.; Thewes, S.; Baskar, R. Regulation of aggregate size and pattern by adenosine and caffeine in cellular slime molds. BMC Dev Biol 2012, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaiswal, P. Interplay between mTORC1 and mTORC2 in Regulating cAMP Signaling and Cell Adhesion in <em>Dictyostelium discoideum</em>. Preprints 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinke, A.; Chen, J.C.Y.; Aronova, S.; Powers, T. Caffeine Targets TOR Complex I and Provides Evidence for a Regulatory Link between the FRB and Kinase Domains of Tor1p*. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2006, 281, 31616–31626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, C.; Klein, G.; Satre, M. Caffeine, an inhibitor of endocytosis in dictyostelium discoideum amoebae. Journal of Cellular Physiology 1990, 144, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppell, B.A.; Newell, A.M.; Brown, E.J. Adenosine receptors are expressed during differentiation of monocytes to macrophages in vitro. Implications for regulation of phagocytosis. The Journal of Immunology 1989, 143, 4141–4145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, Z.A.; Parks, E. The regulation of pinocytosis in mouse macrophages. 3. The induction of vesicle formation by nucleosides and nucleotides. J Exp Med 1967, 125, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foukas, L.C.; Daniele, N.; Ktori, C.; Anderson, K.E.; Jensen, J.; Shepherd, P.R. Direct Effects of Caffeine and Theophylline on p110δ and Other Phosphoinositide 3-Kinases: DIFFERENTIAL EFFECTS ON LIPID KINASE AND PROTEIN KINASE ACTIVITIES*. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2002, 277, 37124–37130. [Google Scholar]

- Saiki, S.; Sasazawa, Y.; Imamichi, Y.; Kawajiri, S.; Fujimaki, T.; Tanida, I.; Kobayashi, H.; Sato, F.; Sato, S.; Ishikawa, K.-I.; et al. Caffeine induces apoptosis by enhancement of autophagy via PI3K/Akt/mTOR/p70S6K inhibition. Autophagy 2011, 7, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, D.-W.; Gaudet, P.; Hudson, J.J.R.; Pears, C.J.; Lakin, N.D. DNA Damage Signalling and Repair in Dictyostelium discoideum. Cell Cycle 2006, 5, 702–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firtel, R.A. Integration of signaling information in controlling cell-fate decisions in Dictyostelium. Genes Dev 1995, 9, 1427–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas, M.E.; Cutler, N.S.; Lorenz, M.C.; Di Como, C.J.; Heitman, J. The TOR signaling cascade regulates gene expression in response to nutrients. Genes Dev 1999, 13, 3271–3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturgill, T.W.; Hall, M.N. Activating Mutations in TOR Are in Similar Structures As Oncogenic Mutations in PI3KCα. ACS Chemical Biology 2009, 4, 999–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rupper, A.; Lee, K.; Knecht, D.; Cardelli, J. Sequential activities of phosphoinositide 3-kinase, PKB/Aakt, and Rab7 during macropinosome formation in Dictyostelium. Mol Biol Cell 2001, 12, 2813–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meena, N.P.; Jaiswal, P.; Chang, F.S.; Brzostowski, J.; Kimmel, A.R. DPF is a cell-density sensing factor, with cell-autonomous and non-autonomous functions during Dictyostelium growth and development. BMC Biol 2019, 17, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, S.; Jena, K.K.; Mehto, S.; Chauhan, N.R.; Sahu, R.; Dhar, K.; Yadav, R.; Krishna, S.; Jaiswal, P.; Chauhan, S. Innate immunity and inflammophagy: balancing the defence and immune homeostasis. Febs j 2022, 289, 4112–4131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehto, S.; Jena, K.K.; Yadav, R.; Priyadarsini, S.; Samal, P.; Krishna, S.; Dhar, K.; Jain, A.; Chauhan, N.R.; Murmu, K.C.; et al. Selective autophagy of RIPosomes maintains innate immune homeostasis during bacterial infection. Embo j 2022, 41, e111289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.P.; Dhakshinamoorthy, R.; Jaiswal, P.; Schmidt, S.; Thewes, S.; Baskar, R. The thyroxine inactivating gene, type III deiodinase, suppresses multiple signaling centers in Dictyostelium discoideum. Dev Biol 2014, 396, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).