1. Introduction

Gallic acid (3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoic acid), an aromatic hydroxycarboxylic acid, is widely used for the synthesis of functional organic compounds, including drugs. Gallic acid (GA) is found in green tea, bearberry leaves, hazel, primrose, grape seeds, from where it can be extracted by various methods [

1]. In the food industry, its esters are used to impart antioxidant properties to compositions. Gallic acid and its derivatives not only provide protection to the cells against oxidative stress but also exhibit excellent anticarcinogenic, antimutagenic, and antimicrobial properties [

2]. Composite films based on chitosan and GA demonstrated high activity against most microorganisms compared to films containing only chitosan, while maintaining mechanical and protective properties [

3].

Covalent cross-linking with a polysaccharide is one of the ways to stabilize antioxidants and drugs thereby improve their bioavailability and safety. A special place among natural biocompatible biodegradable polymers like polysaccharides is occupied by chitin and chitosan derivatives. Their antibacterial activity is comparable to the activity of traditional antibiotics, since the increased cationic density of chitosan macromolecules and its derivatives leads to strong electrostatic interaction with negatively charged areas of the bacterial surface [

4,

5]. The introduction of a benzyl substituent into the structure of chitosan contributed to an increase in the inhibitory activity of the derivatives against fungi [

6]. Experimental data obtained both

in vitro and

in vivo indicate significant biological activity of GA-modified chitosan, in particular as a free radical inhibitor that prevents damage to cellular systems [

7].

Literary sources describe quite a few methods for combining GA and chitosan, both by simple inclusion in chitosan-containing materials and for the purpose of obtaining derivatives. For example, hydrogel composites were obtained by encapsulating GA in cross-linked chitosan [

8,

9,

10]; plasticized films were obtained by adding GA or its salts to a solution of chitosan in 1% acetic acid [

11,

12], including chitosan based ZnO nanoparticles loaded GA films [

13] for active food packaging or spongy materials by lyophilization [

14]; microemulsions were obtained using the water-in-oil method based on natural oils containing GA in the aqueous phase and chitosan as a carrier to ensure its protection and effectiveness during nasal administration [

15]; nanoparticles were prepared by ionotropic gelation using tripolyphosphate at different combinations of component concentration [

16]; chitosan-Cu-GA based antibacterial nanocomposite as wound dressing were fabricated by combining ion-crosslinking, in-situ reduction and microwave-assisted methods [

17].

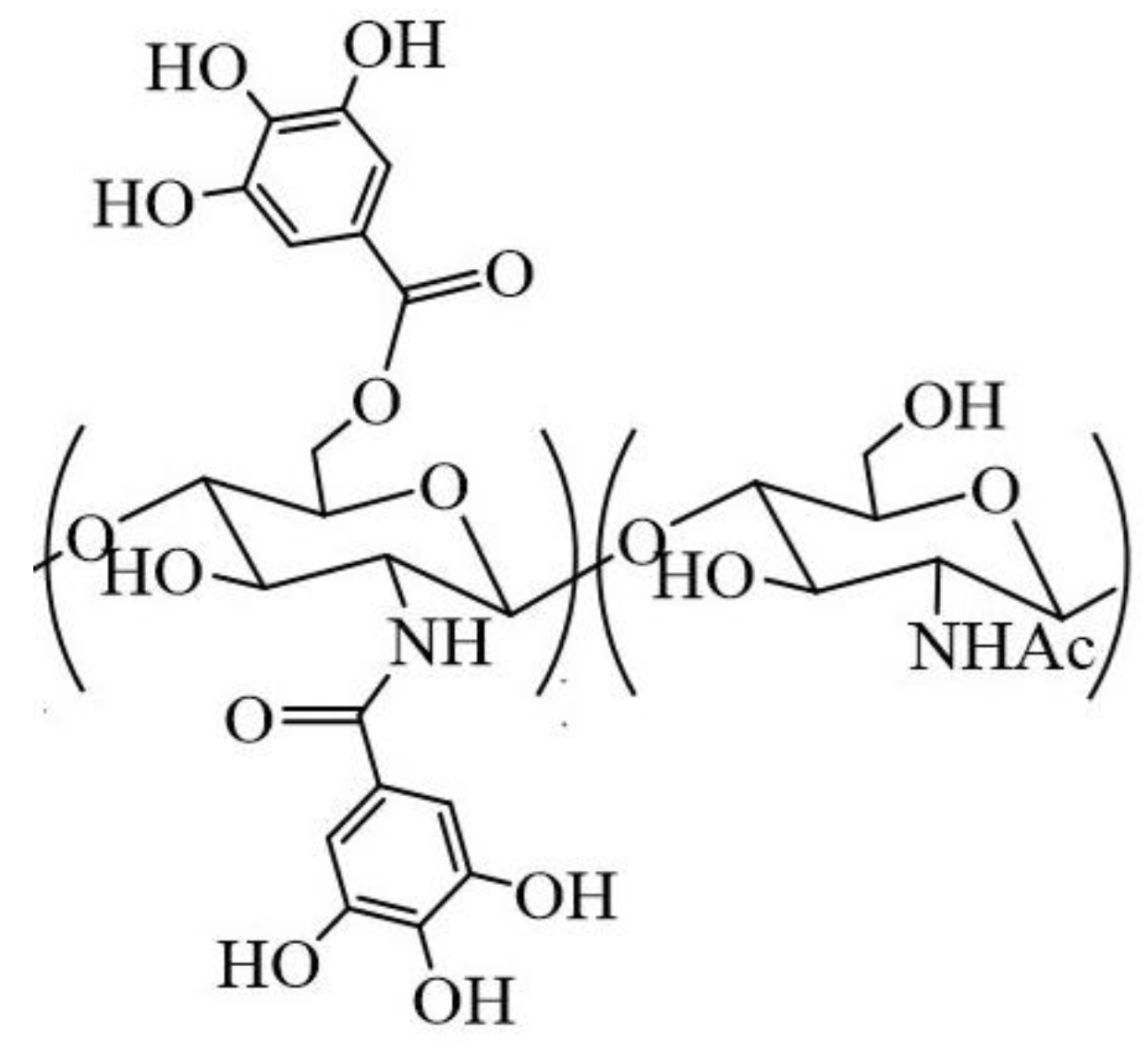

Covalently bound derivatives through the amide and ether linkage of the gallate group with chitosan, the possible structure of which is shown in

Figure 1, are obtained heterogeneously in an aqueous or organic solvent (ethanol) medium in the presence of1-ethyl-3-(3’-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide and using formed N-hydroxysuccinimide as intermediate [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22] or an ascorbic acid/hydrogen peroxide redox pair in an inert atmosphere to initiate free radical mediated process [

23,

24,

25]. All these methods have common disadvantages, namely multi-stage and lengthy processes and the difficulty in purifying target products from additives and solvent residues. Therefore, the growing needs of medicine and biotechnology call for innovative methods of designing chitosan-gallate materials with desirable properties.

Currently, one of the most important synthetic directions is the development of green chemistry methods, which involve the absence of toxic organic solvents and catalysts. Since gallic acid is a solid, limitedly soluble compound with a high melting point (220-240 °C), it was of interest to study its interaction with chitosan at conditions of solid-state synthesis under shear deformations. This approach hinges on activation of the substrate and the reactant during their intense intermixing by applying external mechanical energy. The method has numerous advantages because the entire modification process proceeds in the solid state and does not require melting of components or the use of any solvents as a dispersive medium. The grinding of the substances under shear deformation along with intermixing at the molecular level leads to generation of structural defects, free radicals, double electric layers and excited electron states [

26]. It is worth noting also that, under these conditions, the reactions often proceed “spontaneously”, that is, there is no need in introducing any initiators or catalysts.

Within the framework of the presented work, the experimental conditions were selected using a semi-industrial twin-screw extruder designed for processing solid dispersions. The study of the relationship between the structure of the obtained derivatives and the properties exhibited also seems to be an important task and is the subject of this study.

2. Materials and Methods

Crab chitin (moisture 4.3%, ash content 1.8%) was purchased from Xiamen Fine Chemical Import & Export CO., LTD (China). Chitosan (Chs) were prepared through mechanochemical alkaline deacetylation of this chitin in accordance with the published procedure [

27,

28]. The average molecular weight and degree of deacetylation were 140kDa and 93%, respectively. Gallic acid (3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoic acid, 98%, CAS no. 149-91-7) was purchased from Dia-M (Moscow, Russia) as analytical grade. All other chemicals and reagents used in this study were of analytical grade and commercially available.

The chitosan/gallic acid blends were processed in a pilot twin-screw extruder (Berstorff, Germany) with parallel rotation of screws (d = 40 mm) and controlled heating (4 zones). Pre-mixed reagents with molar ratio of repeating unit of chitosan to GA 1:0.7 were fed manually at screw rotation speed of 60 rpm and processed at temperatures of 40, 100, 120, and 150 °C sequentially (samples CGA1, CGA2, CGA3, and CGA4, respectively). With a residence time of ca. 2 – 3 minutes for one run, feed rate of 30 g min-1 was achieved.

The products were thoroughly rinsed with ethanol to remove unreacted gallic acid and dried in vacuum oven for 24 h (the samples marked using “r” as suffix).The purified samples were dissolved in 2% CH

3COOH (AcOH), and then the insoluble products were separated by centrifugation at 9500 rpm. The soluble fractions were precipitated with 1 M NaOH, and then dialyzed with distilled water for 48 h to remove low molecular weight impurities followed by freeze-drying to produce the samples in powder form (the samples marked using “p” as suffix). In

Table 1 are listed data on the conditions of sample synthesis and their solubility.

Table 2 presents data on the amount of GA bonded with chitosan, depending on the synthesis conditions.

FT-IR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Vertex 70 spectrometer (USA) in the frequency range of 4000–400 cm

−1and treated using a set of programs Bruker Opus. All spectra were initially collected in ATR mode at resolution of 4 cm

-1 by employing an ATR-monorefection Gladi ATR (Pike Technologies, USA) accessory equipped with diamond crystal (n = 2.4; angle of incidence 45 deg.). The obtained ATR spectra were converted into IR-Absorbance mode. All the chitosan-contained spectra were normalized to the same intensity of the composite band of C–O stretching vibrations of pyranose ring at 1075 см

–1 [

29]. The band assignments were made according to [

29,

30,

31].

Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) spectra were recorded at 30 °C for samples (weighing about 8 mg) dissolved in 1% DCl/D2O (v/v) using a Bruker-Avance spectrometer (Bruker Corporation, Massachusetts, USA) under a static magnetic field of 400 MHz and Me4Si as an internal standard.

The light attenuation spectra of 1% polymer solution in 2% AcOH were recorded using a Shimadzu UV 2501 PC spectrophotometer (Japan) in a quartz cuvette with an optical path of 1 cm. Spectral data were analyzed after subtracting the contribution of the solvent.

Fluorescence spectra were measured on a FLUORAN-2 spectrophotometer/spectrofluorimeter (VNIIOFI, Russia) in standard 10×10 mm quartz cuvettes.

The dynamic viscosity of 1% solutions of samples in 2% acetic acid was measured on a Brookfield DV-E rotational viscometer (spindle No. 2) at 25 °C and shear rate of 50, 60 and 100 rpm.

Ultrasound treatment was carried out by using laboratory ultrasonic generatorI-10-0.63 (Inlab-Ultrasound, Russia). The probe tip (diameter 13mm) was immersed in the processing solution down to ~1.5 cm above the bottom of the sonoreactor vessel. The sonication was run at a fixed wavelength of 23 kHz for 60 sec.

Microstructure of the samples was imagined using a Levenhuk D320 L digital monocular microscope (USA). Magnification of ×400 was used.

3. Results

3.1. UV-vis

As shown in

Figure S1a, GA has an absorption band in the region of 240-320 nm depending on the pH of the medium. A clearly defined Gaussian absorption band with a maximum at 271 nm was observed in 2% AcOH solution. When diluted in water at different optical densities (2 and 0.2), the maximum is at 265 and 260 nm, respectively. Original Chs is characterized by low absorption intensity, and is practically transparent in this region. Unlike Chs, GA absorbs 2–3 orders of magnitude more intensely, therefore, to study the absorption region of GA, additional dilution of the CGA products was carried out.

The light attenuation spectrum of the original chitosan contains scattering on particles with a size much smaller than the wavelength and weak absorption bands with maxima at about 252, 299 and 348 nm (

Figure S1b), which we have previously observed on chitosan samples obtained by the solid-state method [

32]. For further analysis, mathematical separation of absorption and scattering bands was not carried out.

Four CGA samples obtained under different processing conditions in extruder were analyzed in comparison with the initial solutions of Chs and GA. All solutions were prepared in 2% ACOH, which is a good solvent for Chs and products based on it.

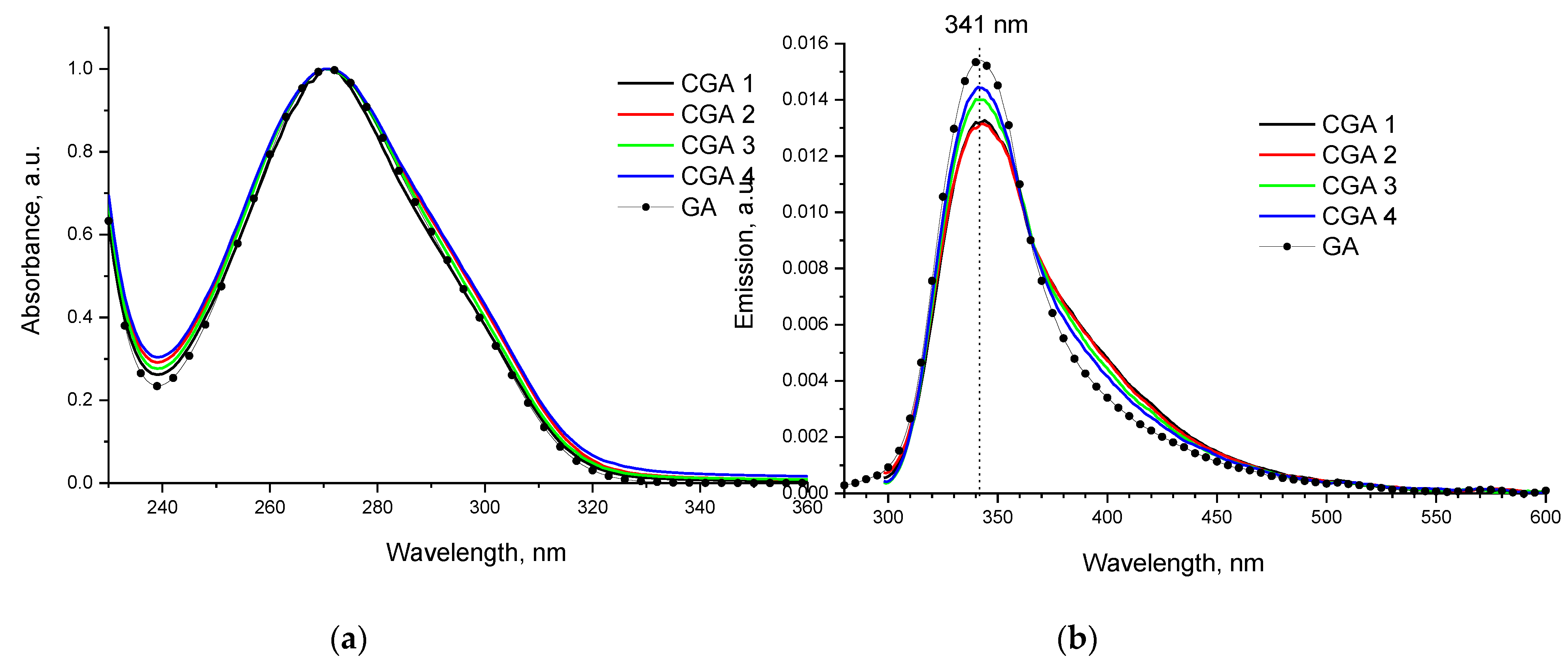

The absorption spectra of dilute solutions of CGA contain an intense absorption band with a maximum at 270-271 nm, characteristic of the original GA (

Figure 2). When excited to this band, the solutions are characterized by weak but clearly observable fluorescence, close in position to the original GA.

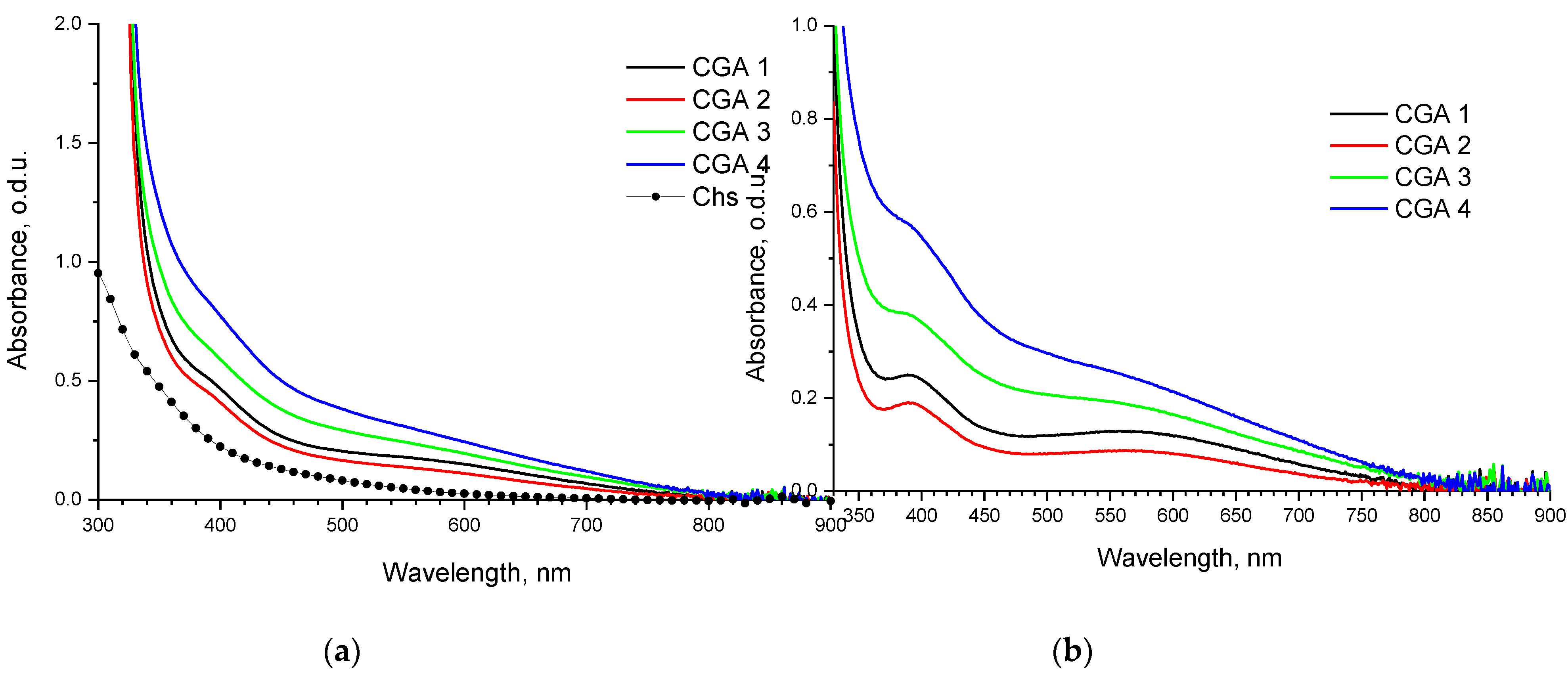

The native spectra of the CGA samples have a greater absorption in the region of 350-900 nm, compared to the original solution of Chs (Figure3a). They are also characterized by the presence of scattering on particles with a size much smaller than the wavelength. To assess the change in the shape of the absorption spectrum, difference spectra were used, for which the spectrum of the original Chs was subtracted from the recorded spectra (

Figure 3b).

3.2. FT-IR

The FT-IR spectra of GA and original chitosan are shown in

Figure S2. A band at 1590 cm

-1 in IR-spectrum of chitosan is characteristic for primary amines. The IR-bands of the carbonyl stretching, ν

C=O (amide I, at 1650 cm

-1), and the NH bending, δ

NH (amide II, at 1550 cm

-1) belong to acetylated units of chitosan. The stretching vibrations of hydroxyl and amine groups involved in hydrogen bonding are observed in 3000 – 3500 cm

-1 region; N-H stretching mode, split into doublet (symmetric and asymmetric vibrations), appears near 3300 cm

-1. GA spectrum presents the characteristic bands of absorption at 3492, 3370 and 3270 cm

–1, related to different forms of benzene ring–OH stretching vibrations; bands at 2920 and 2850 cm

–1 corresponding to the stretching of C−H in aromatics; a band at 1700 cm

–1 corresponding to the carbonyl absorption in carboxylic acid. The band corresponding to the carboxyl group conjugated to double bond ν

C=O appears near 1680 cm

–1 in the spectrum. The IR-bands 1605/1540 and shoulder at 1483 cm

–1 belong to stretching vibrations of C=C of benzene ring and C−O/C−C stretching vibrations appear within 1200–1300 cm

−1.

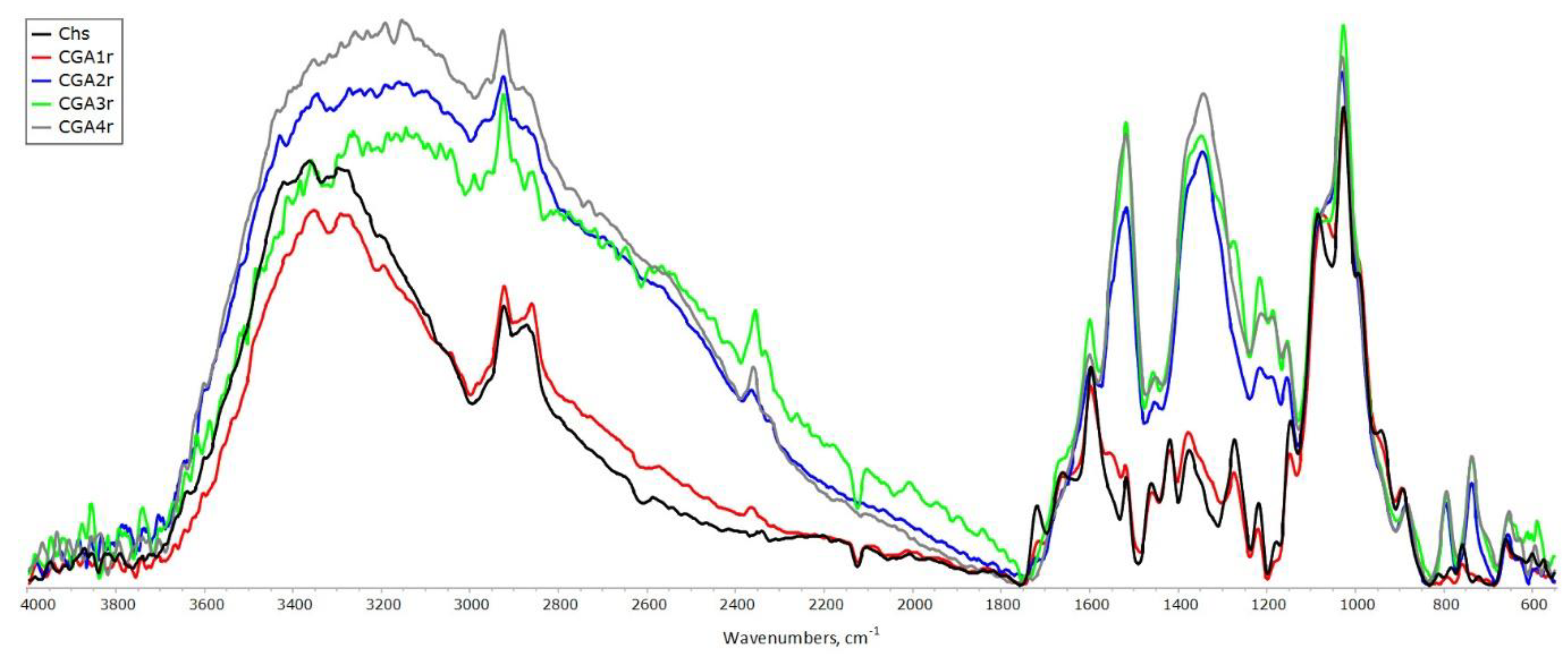

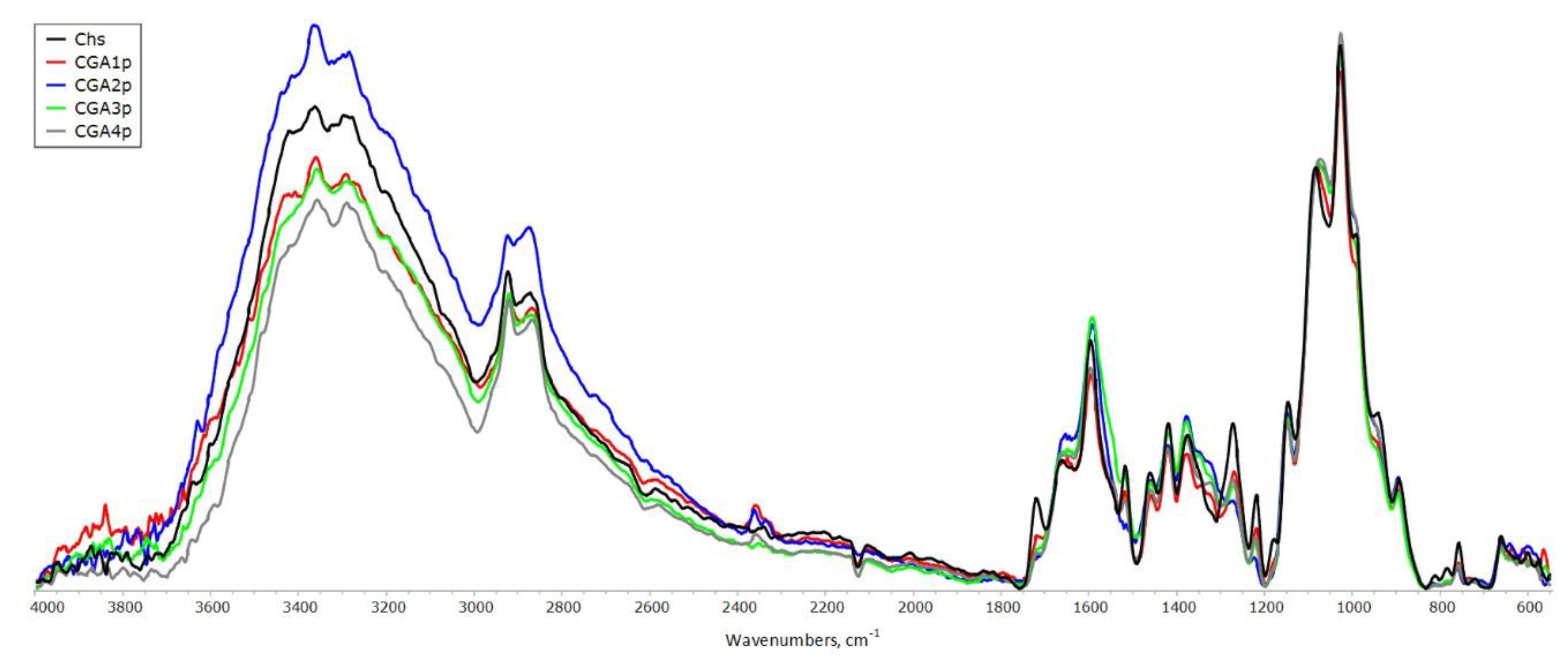

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 show the IR spectra of CGAr and CGAp samples, respectively.

3.3. 1H NMR Spectroscopy

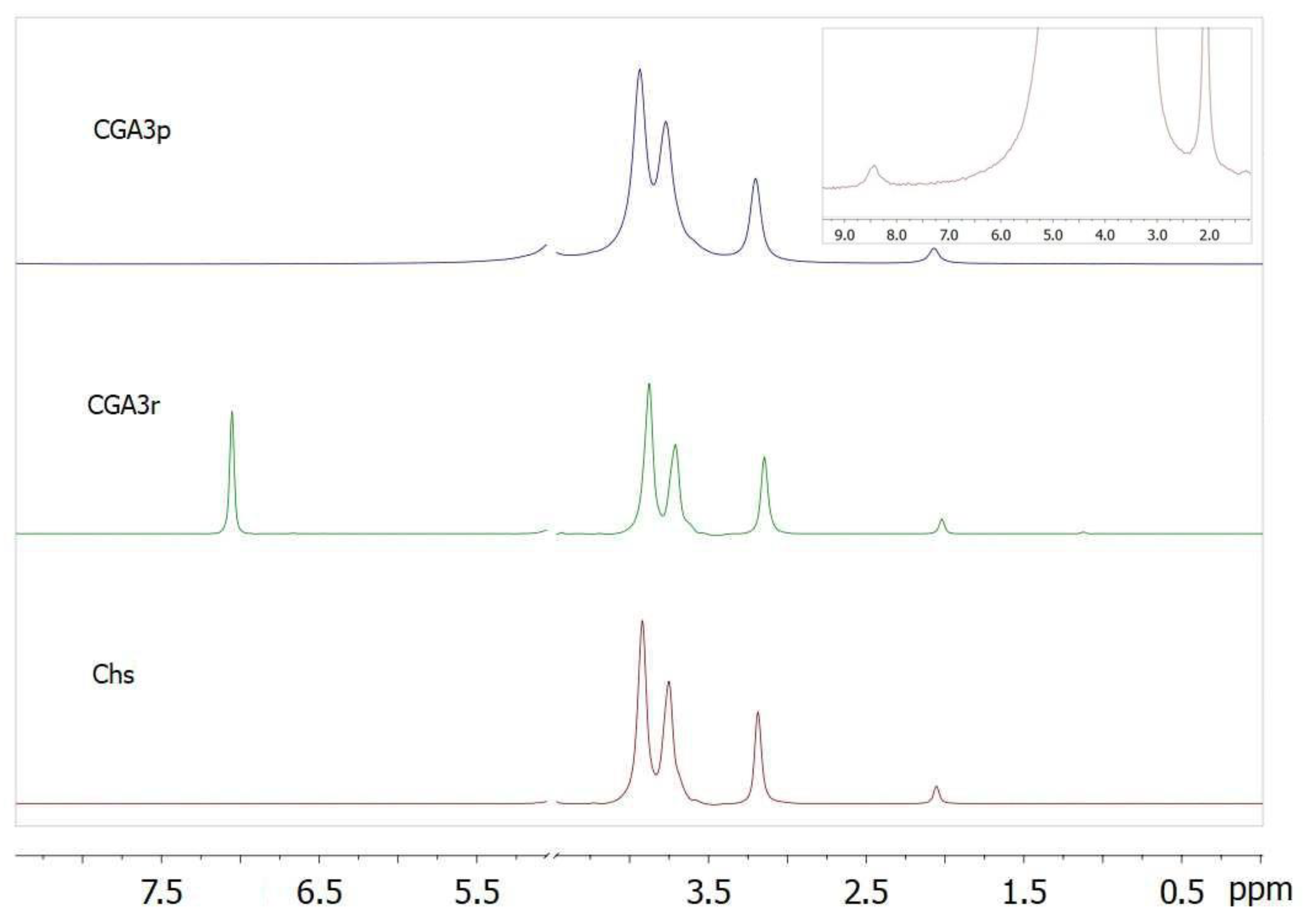

Figure 6 shows the

1H NMR spectra of CGA3 samples

vs original chitosan. As shown in

Figure 6, original chitosan peaks occurred at δ = 2.1 ppm (

H3C–CONH–), 3.2 (>C

H–NH

2), and 3.6–4.0 (H-3 to H-6 of pyranose ring), and the CGA3r showed a new peak at 7.1 ppm belonging to phenyl protons as compared to the chitosan. The selected region of the CGA3p spectrum is shown to detect low intensity signal of the protons of phenyl group.

3.4. Rheology and Behavior of the Sinthesized CGA Samples in Water

A study of the dependence of the dynamic viscosity of chitosan solutions in 2% AcOH on concentration shows that the crossover point when the polymer macromolecules begin to associate corresponds to 2.0±0.2 wt% [

33]. Therefore, rheology experiments were done with 1 wt.% solutions of chitosan and CGA samples in the region of a weak dependence of viscosity on concentration. The data on dynamic viscosity of chitosan and the synthesized CGA in 2% AcOH at different shear rates are presented in

Table 3 and

Figure S3.

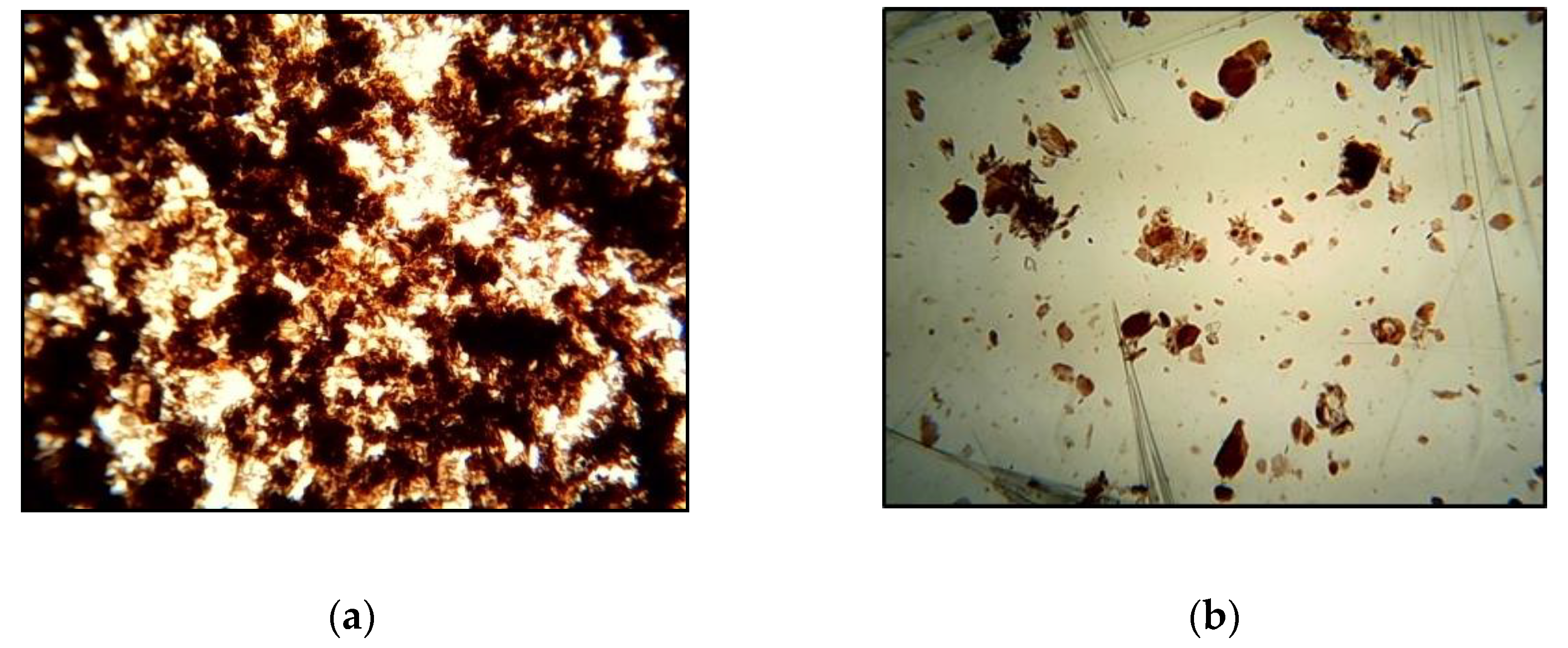

The obtained products were found to swell well and partially dissolve in water. After drying of the dilute aqueous suspension (1 wt.% polymer), they tend to form films, where the well-swollen fraction is dispersed in the polymer matrix as a continuous phase. As shown in

Figure 7, this behavior differs significantly from the physical mixing of the components in the same ratio. The latter form powders when dried (

Figure 7b).

An aqueous suspension of sample CGA3 was also ultrasonically treated at 23 kHz. The ability of suspended particles to associate was observed due to rearrangement after ultrasonic treatment, as shown in

Figure S4. The aggregates with an average size of 206±36 µm were obtained.

4. Discussion

According to UV-vis spectroscopy data, when CGA samples are dissolved in water, both chitosan and GA are present in the solution. The position of the GA absorption maximum in the spectrum corresponds to the absorption region of GA in the aqueous solution. Part of the samples does not pass into solution, and forms dispersion of swollen particles that transform into a gel with a characteristic lilac color when kept. As it is shown in

Figure S5, the characteristic coloration appears in powder samples during processing in the extruder, and its intensity depends on the temperature and duration of the process. It can be assumed that mechanical-chemical treatment leads to the formation of both the salt form of chitosan and GA, and derivatives with varying degrees of substitution of the functional groups of chitosan.

As shown in

Figure 2a, GA and CGA samples exhibited absorption band at 271 nm when dissolved in 2% ACOH, which should be assigned to the π-system of the benzene ring. When excited to this band, the solutions are characterized by weak but clearly observable fluorescence, close in position to the original GA (

Figure 2b). The long-wavelength fluorescence edge of all CGA samples is slightly broadened compared to the original GA spectrum, probably due to the formation of a bond with chitosan. The fluorescence intensity increased with the increase of phenolic content in CGA samples, indicating the successful binding of GA to chitosan.

From the analysis of the difference spectra (

Figure 3b) it is evident that after processing in the extruder, a wide diffuse absorption in the region of 350-800 nm appeared in the spectra of the CGA products. The new absorption band with a maximum at 396 nm, the contribution of which increases with increasing temperature and treatment time, we assume is due to chromophores as a result of the interaction of the amino groups of chitosan and gallic acid to form an amide. This band is associated with a new system of conjugated bonds due to the participation of the electron of the lone pair of the nitrogen atom in π→π* absorption [

34]. Thus, the products contain groups characteristic of GA, and new chromophore groups of the modified main chain of chitosan are also observed.

The synthesized CGA samples were characterized by FT-IR spectroscopy. The binding of GA to chitosan is possible either at C-2 to form an amide bond, or at C-3 and C-6 to obtain the ester linkage (

Figure 1). The band at 1730 cm

-1, which assigned to the C=O stretching in esters, was not obvious, indicating that the ester groups were not formed under studied processing conditions. Spectrum of CGA1r samples shows decrease in intensity at 1600 cm

-1, as compared to initial chitosan, implying the consumption of amine groups in the reaction (

Figure 4). With an increase in the content of bound acid in the samples (see data in

Table 2), the intensity of this band increases significantly due to the superposition of the band of stretching vibrations of the double bonds of the benzene ring. But the most intense bands in this region of the CGA2-4 spectra are the superposition of the characteristic bands of GA and stretching vibrations of carboxylate ions appear near 1575 cm

–1. The band at 1340 cm

–1 with shoulder at 1380 cm

–1 is assigned to the symmetric vibrations of carboxylate groups; the band centered at 1183 cm

–1 – to deformation vibrations of the skeleton of the (C=O)-O group. In addition, these bands intensity increased with the increase of phenolic content in CGA samples. The N-H stretching modes at 3294 and 3361 cm

–1 overlap with a broad band of stretching vibrations of hydroxyl groups, participating in the newly formed hydrogen bond network.

For the precipitated samples, the increase in intensity of the absorption bands at around 1650, 1550 and 1320 cm

−1 was observed, corresponding to the C=O stretching (amide I), N-H bending (amide II) and C-N stretching (amide III), respectively. The changes are most pronounced for CGA2,3 samples obtained at a moderate synthesis temperature (100-120 °C), indicating the possibility of a reaction occurring with the formation of amide linkages between chitosan and GA. A slight decrease in solubility was found for samples prepared at temperatures above 100 °C (see data in

Table 1). The insoluble fractions were a gel separated from the solutions by centrifugation.

As shown in

Figure 6, the

1H NMR spectra of CGA3r showed a new peak at 7.1 ppm belonging to phenyl protons as compared to the chitosan. However, the spectrum of the reprecipitated sample contains only a weak signal of the phenyl protons, shifted to 8.5 ppm. It can be concluded that the gallate groups were predominantly introduced onto chitosan via salt linkages. Although the resulting compounds were only partially soluble in water, the well-swelling suspended particles tended to aggregate with the formation of a continuous phase, as shown in

Figure 7a. It can be assumed that such aggregates with an average size of 206±36 µm (see

Figure S4) will be of interest as microcarriers for drug delivery.

Under the experimental conditions studied, solutions of chitosan and its derivatives, like many high-molecular biopolymers and polyelectrolytes, demonstrated non-Newtonian behavior with increasing shear rate (

Figure S3).The data presented in

Table 3 also show that the dynamic viscosity of 1% solutions of CGA samples is significantly lower compared to the original chitosan, which is probably due to the destruction of the polymer chain during extrusion in the presence of GA. However, films prepared from both chitosan and CGA samples by casting from solutions in dilute acetic acid had satisfactory mechanical strength.

5. Conclusions

To introduce gallate groups into chitosan chains, mechanochemical treatment was used under shear deformation of solid dispersions of components in a twin-screw extruder. Then, the synthesized compounds were characterized by UV–vis, Fourier-transform infrared and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy to confirm the structure. As studies have shown, solid salts of chitosan and gallic acid were obtained with a phenolic compound content of more than 600 mg per 1 g of polymer. All the methods used also indicate the possibility of a reaction with the formation of amide bonds between chitosan and GA under chosen conditions of solvent-free synthesis. Since the bands that can be assigned to the ester groups were not found, it can be conclude that radical processes do not contribute to the formation of reaction products under studied processing parameters. To investigate the physical–chemical properties of GA-chitosan products, their solubility was evaluated; rheological behavior and morphological structure were determined by rheometry measures and optic microscopy, respectively. It was shown that the resulting products swelled well and partially dissolved in water with a tendency to form aggregates in aqueous media. The obtained results can contribute to the development of a novel natural-compound-based antioxidants and antibacterial compositions to functionalize chitosan with aromatic hydroxycarboxylic acids by green chemistry mechanical-chemical approach without the use of any solvents or toxic catalysts and initiators in the processes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Figure S1: Light attenuation spectra: (a) 1% solution of GA in 2% AcOH and in water at different dilutions, (b) 1% solution of chitosan in 2% AcOH; Figure S2: FT-IR spectra of GA and original chitosan; Figure S3: Dynamic viscosity versus shear rate curves for chitosan and CGAr samples dissolved in 2% acetic acid at 25°C and 1% polymer concentration; Figure S4: Optical microphotographs of the 1 wt.% aqueous suspension of CGA3 sample after ultrasonic treatment and size distribution of the suspended particles; Figure S5: Optical micrographs of the powder samples after processing in the extruder and the samples dissolved in 2% acetic acid at 1% polymer concentration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.K. and T.A.A.; methodology, T.A.A. and P.L.I.; validation, T.A.A. and E.A.S.; investigation, E.A.S., T.N.P., B.V.M., N.B.S. and A.A.Z.; data curation, M.A.K. and T.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, T.A.A. and N.B.S.; writing—review and editing, T.A.A.; visualization, M.A.K. and A.A.Z.; supervision, T.A.A.; project administration, T.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Russian Science Foundation, grant number 24-23-20057.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The spectroscopy experiments were performed using the equipment of the Center for Collective Usage “Center for Investigation of Polymers” of the Institute of Synthetic Polymeric Materials, Russian Academy of Sciences and supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (topic number FFSM-2024-0002).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Wianowska, D.; Olszowy-Tomczyk, M. A Concise Profile of Gallic Acid—From Its Natural Sources through Biological Properties and Chemical Methods of Determination. Molecules 2023, 28, 1186–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choubey, S.; Goyal, S.; Varughese, L. R.; Kumar, V.; Sharma, A. K.; Beniwal, V. . Probing Gallic Acid for Its Broad Spectrum Applications. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2018, 18, 1283–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lunkov, A.P.; Ilyina, A.V.; Varlamov, V.P. Antioxidant, antimicrobial, and fungicidalproperties of chitosan based films (review). Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2018, 54, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhuang, S. Antibacterial activity of chitosan and its derivatives and their interaction mechanism with bacteria: Current state and perspectives. Eur. Polym. J. 2020, 138, 109984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xue, C.; Mao, X. Chitosan: Structural modification, biological activity and application. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 4532–4546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badawy, M.E.I.; Rabea, E.I.; Taktak, N.E.M. Antimicrobial and inhibitory enzyme activity of N-(benzyl) and quaternary N-(benzyl) chitosan derivatives on plant pathogens. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 111, 670–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varlamov, V.P.; Il’ina, A.V.; Shagdarova, B.T.; Lunkov, A.P.; Mysyakina, I.S. Chitin/Chitosan and Its Derivatives: Fundamental Problems and Practical Approaches. Biochem. 2020, 85( Suppl. 1.), S154–S176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.; Vales, T.P.; Cho, B.-K.; Kim, J.-K.; Kim, H.-J. Development of Gallic Acid-Modified Hydrogels Using Interpenetrating Chitosan Network and Evaluation of Their Antioxidant Activity. Molecules 2017, 22, 1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thanyacharoen, T.; Chuysinuan, P.; Techasakul, S.; Nooeaid, P.; Ummartyotin, S. Development of a gallic acid-loaded chitosan and polyvinyl alcohol hydrogel composite: Release characteristics and antioxidant activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 107, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzano, M.; Borbone, N.; Amato, F.; Fucile, P.; Russo, T.; Sannino, F. 3D Chitosan-Gallic Acid Complexes: Assessment of the Chemical and Biological Properties. Gels 2022, 8, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wang, Z.; Kadouh, H.; Zhou, K. The antimicrobial, mechanical, physical and structural properties of chitosan–gallic acid films. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2014, 57, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarandona, I.; Puertas, A.I.; Dueñas, M.T.; Guerrero, P.; De La Caba, K. Assessment of active chitosan films incorporated with gallic acid. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 101, 105486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Mehrotra, G.K.; Dutta, P.K. Chitosan based ZnO nanoparticles loaded gallic-acid films for active food packaging. Food Chem. 2021, 334, 127605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thangavel, P.; Ramachandran, B.; Muthuvijayan, V. Fabrication of chitosan/gallic acid 3D microporous scaffold for tissue engineering applications. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Applied Biomaterials. 2016, 104, 750–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitsou, E.; Pletsa, V.; Sotiroudis, G.T.; Panine, P.; Zoumpanioti, M.; Xenakis, A. Development of a microemulsion for encapsulation and delivery of gallic acid. The role of chitosan. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2020, 190, 110974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamarra, J.; Rivero, S.; Pinotti, A. Design of chitosan-based nanoparticles functionalized with gallic acid. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2016, 67, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Dong, M.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Jia, P.; Bu, T.; Liu, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, L. Multifunctional chitosan-copper-gallic acid based antibacterial nanocomposite wound dressing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 167, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasanphan, W.; Chirachanchai, S. Conjugation of gallic acid onto chitosan: An approach for green and water-based antioxidant. Carbohydr. Polym. 2008, 72, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M. , et al. , Grafting of Gallic Acid onto Chitosan Enhances Antioxidant Activities and Alters Rheological Properties of the Copolymer. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2014, 62, 9128–9136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rui, L.; Xie, M.; Hu, B.; Zhou, L.; Yin, D.; Zeng, X. A comparative study on chitosan/gelatin composite films with conjugated or incorporated gallic acid. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 173, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Anderson, J.D.; Bozell, J.J.; Zivanovic, S. The effect of solvent composition on grafting gallic acid onto chitosan via carbodiimide. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 140, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Du, H.; Xie, M.; G Ma, Yang, W. ; Hu, Q.; Pei, F. Characterization of the physical properties and biological activity of chitosan films grafted with gallic acid and caffeic acid: A comparison study. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2019, 22, 100401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lu, J.; Kan, J.; Jin, C. Synthesis of chitosan-gallic acid conjugate: Structure characterization and in vitro anti-diabetic potential. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2013, 62, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, Y.-S. , Kim, S.K.; Ahn, C.B.; Je, J.Y. Preparation, characterization, and antioxidant properties of gallic acid-grafted-chitosans. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 83, 1617–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Wang, T.; Zhou, M.; Xue, J.; Luo, Y. In Vitro Antioxidant-Activity Evaluation of Gallic-Acid-Grafted Chitosan Conjugate Synthesized by Free-Radical-Induced Grafting Method. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 5893–5900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butyagin, P.Y. Forced Reactions in Inorganic and Organic Chemistry. Colloid J. 1999, 61, 537–544. [Google Scholar]

- Rogovina, S.Z.; Akopova, T.A.; Vikhoreva, G.A. Investigation of Properties of Chitosan Obtained by Solid-Phase and Suspension Methods. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1998, 70, 927–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akopova, T.A.; Zelenetskii, A.N.; Ozerin, A.N. Solid State Synthesis and Modification of Chitosan. In Focus on Chitosan Research; Ferguson, A.N., O'Neill, A.G., Eds.; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: NY, 2011; Chapter 8, pp. 223-254. [Google Scholar]

- Brugnerotto, J.; Lizardi, J.; Goycoolea, F.M.; Argüelles-Monal, W.; Desbrières, J.; Rinaudo, M. An infrared investigation in relation with chitin and chitosan characterization. Polymer 2001, 42, 3569–3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, M.L.; Ferreira, M.C.; Marvao, M.R.; Rocha, J. An optimised method to determine the degree of acetylation of chitin and chitosan by FTIR spectroscopy. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2002, 31, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellamy, L.J. The infra-red spectra of complex molecules, 2nd ed.; Methuen: London, Wiley, New York, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Popyrina, T.N.; Svidchenko, E.A.; Demina, T.S.; Akopova, T.A.; Zelenetsky, A.N. Effect of the Chemical Structure of Chitosan Copolymers with Oligolactides on the Morphology and Properties of Macroporous Hydrogels Based on Them. Polym. Sci. B 2021, 63, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uspenskii, S.; Potseleev, V.; Svidchenko, E.; Goncharuk, G.; Zelenetskii, A.; Akopova, T. Photo-curing chitosan-g-N-methylolacrylamide compositions: Synthesis and Characterization. Polysaccharides 2022, 3, 831–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, S.F. Electronic absorption spectra of heterocyclic compounds. In Phys. Methods Heterocycl. Chem.; Katritzky, A.R., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, 1967; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).