1. Introduction

In recent years, malware has evolved into one of the most pervasive cybersecurity threats, capable of targeting not only traditional systems such as PCs, but also mobile devices, IoT, and cloud platforms. Malware is becoming increasingly complex and varied by employing methods such as code obfuscation, encryption, polymorphism, and metamorphism to avoid detection [

1]. The increasing sophistication of malware and its capability to bypass conventional security measures have caused significant financial, operational, and reputational damage to individuals, businesses, and governments. As technology becomes increasingly integrated across platforms, cybercriminals can simultaneously exploit multiple systems. Therefore, a thorough investigation of multi-platform malware detection is not only timely but crucial for ensuring cybersecurity resilience.

In the context of cybersecurity, malware refers to malicious software that is intentionally designed to disrupt, damage, or gain unauthorized access to computer systems. In contrast, multi-platform malware is malware capable of infecting and spreading across various types of platforms, often simultaneously. Malware can be categorized into several forms depending on its purpose and information-sharing system, such as ransomware, spyware, adware, rootkits, worms, horses, botnets, trojans, and viruses. Machine learning (ML), in this study, refers to computational techniques that allow systems to learn from data and improve their performance over time without being explicitly programmed. The application of ML for malware detection has shown significant potential for automating threat identification and reducing detection latency, especially in environments with high complexity and variability.

The increasing prevalence of malware is evidenced by the increasing number of global cyberattacks. According to the 2024 Cisco Cybersecurity Readiness Index [

2], 76% of firms experience malware attacks, as shown in

Figure 1. Astra’s Malware Statistics 2024 reports that 560,000 new malware pieces are detected daily, adding to over 1 billion existing programs. This large volume of malware thwarts organizational security, often resulting in ransomware attacks [

3]. The scale and impact of ransomware attacks are expected to increase significantly in the future. Cybersecurity Ventures predict that victims could pay approximately

$265 billion annually by 2031, with costs increasing by 30% each year [

4]. Malware targeting Linux systems has also increased, with a 35% increase in infections and the emergence of new malware families impacting Linux-based platforms [

5].

Furthermore, 2023 marked a pivotal moment for IoT security threats. A report from Zscaler ThreatLabz in October 2023 showed a 400% increase in IoT malware attacks compared to the previous year [

6]. Overall, the global proliferation of mobile devices, IoT systems, and cloud computing has expanded the attack surface, providing cybercriminals with new vectors for deploying malware. Hence, new challenges have arisen for malware detection. Traditional malware detection methods tailored to specific platforms, such as PCs or mobile devices, are insufficient to counter these new threats. This underscores the necessity of adopting a unified, multi-platform approach to malware detection that can provide holistic defense strategies.

In response to this evolving threat landscape, numerous studies have been conducted with an increasing focus on machine learning (ML), owing to its ability to handle the complexity of modern threats. Traditional approaches to malware detection, such as signature-based and heuristic methods, have proven inadequate for combating sophisticated and polymorphic malware, particularly in dynamic, multi-platform environments. Thus, the development of more advanced detection techniques, such as behavior-based and machine learning (ML)-driven approaches, has become essential in modern cybersecurity defenses

Despite the rising threat of multi-platform malware, existing research on malware detection remains predominantly focused on single platforms, either PCs or mobile devices, with relatively few studies addressing IoT or cloud environments. Moreover, these studies often fail to account for the growing interconnectivity between platforms, which allows malware to migrate easily from one system to another. This creates a significant gap in the literature, as there is no comprehensive review of machine learning techniques that address malware detection across PCs, mobile devices, IoT, and cloud environments.

Multi-platform malware detection is, therefore, critical for several reasons. Cyberattacks today often exploit the weakest link across interconnected systems. For instance, a single vulnerability in an IoT device can be leveraged to infiltrate broader networks, including enterprise cloud systems. Second, malware has evolved to operate across multiple platforms, with many modern malware variants designed to be adaptable to different operating environments. Mirai, a botnet initially designed to target IoT devices, was later modified to attack cloud-based systems and enterprise networks. Hence, developing unified defense strategies is essential, as organizations adopt hybrid environments that combine on-premises and cloud-based systems.

This survey aims to fill this gap by providing a holistic review of the recent literature on malware detection using ML methods across diverse platforms. This paper reviews the state-of-the-art ML techniques used to detect malware on PCs, mobile devices, IoT systems, and cloud environments. It also outlines the specific challenges encountered on each platform and provides insights for adapting techniques for cross-platform usage. In doing so, this survey not only serves as a valuable resource for researchers and practitioners in cybersecurity, but also offers a foundation for future research into adaptable, cross-platform malware detection strategies using machine learning.

The key contributions of this study are as follows.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive review of malware detection in PCs, mobile devices, IoT systems, and cloud environments using machine-learning techniques.

This study details the various types of features (e.g., static, dynamic, memory, and hybrid) used to train the ML models. It also discusses the malware landscape across platforms and identifies both platform-specific challenges and cross-platform issues that affect the development of effective ML-based malware detection techniques.

This study examines existing malware detection techniques using various ML and DL models and provides the overall research trends observed for each platform.

This study highlights gaps in the existing research and proposes future directions, such as developing adaptable, scalable, and efficient ML algorithms for multiple platforms and promoting unified cross-platform malware detection approaches.

The structure of this survey is organized as follows:

Section 2 provides a comparison with previous related work.

Section 3 provides an overview of malware, including malware definitions, leading malware threats, malware analysis, and features used to build the ML model for malware detection.

Section 4 describes the malware landscape across diverse platforms.

Section 5 presents an overview of machine learning algorithms for malware detection.

Section 6 provides an extensive review of malware detection using ML techniques with respect to PCs, mobile devices, the IoT, and cloud platforms.

Section 7 presents the challenges associated with platform and cross-platforms.

Section 8 presents the limitations of the existing literature and future research directions. Finally,

Section 9 concludes the paper.

2. Comparison with Previous Related Surveys

This section examines survey papers on malware detection via machine learning from 2017 onwards, highlighting the gaps that we intend to address. This will help researchers to establish a baseline for developing countermeasures.

Table 1 compares our survey with existing surveys.

Existing surveys on malware detection using machine learning and deep learning typically focus on specific platforms such as Windows [

7,

8,

9,

11] or Android [

10,

12,

13]. A small number of studies [

17,

18] have examined both Windows and Android. Some surveys [

14,

15,

16] have addressed malware classification in IoT platforms using ML and DL techniques. However, many current studies lack a comprehensive understanding of the IoT malware. Few studies have focused on cloud malware. Belal and Sundaram [

19] provided a taxonomy of ML/DL-based cloud security, addressing issues, challenges, and trends, whereas Aslan et al. [

20] discussed behavior-based malware detection in the cloud.

Table 1 also reveals that several surveys have focused exclusively on DL technologies for malware detection, such as those in [

9,

17,

21,

22], without focusing on traditional ML or ensemble learning techniques. However, traditional ML and ensemble learning offer distinct advantages including lower computational requirements, faster training times, and better performance on smaller datasets.

These benefits highlight the importance of exploring these techniques along with DL for comprehensive malware detection strategies. Moreover, existing surveys fail to comprehensively address malware detection across platforms such as Linux, macOS, iOS, IoT, and the cloud, which are also frequently targeted by malware. The lack of platform diversity in current surveys highlights the need for an inclusive review that covers various environments to thoroughly understand malware-detection methods. To fill these gaps, this study provides a comprehensive survey of recent ML and DL approaches for malware detection across Windows, Linux, macOS, Android, IoT, and cloud platforms, which are frequently targeted by malware.

3. Malware Fundamentals

This section explores the fundamental aspects of malware, including its definition, type, and disruptive impact on systems and data. It also highlights recent and significant malware threats, discusses standard analysis techniques, and examines the critical features that enable machine learning to detect and combat these threats.

3.1. What is Malware

Malware refers to malicious software designed to compromise computer systems or to gain unauthorized access. Despite advancements in cybersecurity, malware remains a significant threat, disrupting systems by stealing information, rendering services unavailable, or damaging files. Common malware categories include viruses, worms, trojans, backdoors, spyware, adware, botnets, rootkits and ransomware. Each exhibits distinct behaviors: viruses modify or delete files, worms self-replicate across networks, rootkits allow remote control, and Trojans masquerade as legitimate applications for covert activities. Adware displays unwanted ads, spyware tracks user activities, botnets exploit resources, backdoors bypass security for unauthorized access, and ransomware encrypts data, demanding payments for decryption [

23]. This classification highlights the diverse operational goals of the malware.

3.2. Leading Malware Threats in the Current Cyber Landscape

The cyberthreat landscape is dominated by sophisticated malware that targets multiple platforms. Malware increasingly employs evasive, polymorphic, and adaptive tactics to evade traditional security measures, thereby posing detection and mitigation challenges. Cybercriminals also leverage AI-powered malware, further complicating defense.

In this section, we examine prevalent malware threats, their characteristics, attack methods, and associated damages, underscoring the need for cybersecurity professionals to remain informed and proactive against these evolving threats.

Ransomware: Ransomware continues to be one of the most widespread and damaging forms of malware. The COVID-19 pandemic led to an increase in ransomware activities, which have further escalated in 2023. Ransomware attacks have shifted from targeting large enterprises with complex methods to widespread attacks on small businesses facilitated by Ransomware-as-a-Service kits. Currently, LockBit is the most prevalent ransomware toolset. In February 2024, an international law enforcement operation seized 34 LockBit servers; however, LockBit3.0 quickly emerged just five days later [

24].

Ransomware attacks target a wide range of computing devices, including desktops, mobiles, IoT, and cloud environments. Cybercriminals employ various attack vectors such as phishing spams and exploit vulnerabilities to deliver malicious files [

25]. The ransomware then encrypts the critical files and collects information regarding the target. They frequently connect to remote servers to obtain additional components or transfer files. Victims receive recovery instructions, often through ransom notes or desktop changes, in exchange for payments.

Recent high-profile ransomware attacks by Conti, REvil, Darkside, and LockBit 3.0 have significantly impacted global infrastructure, healthcare, and businesses. For instance, Conti’s attack on Costa Rica’s government led to a national state of emergency [

26], whereas REvil’s Kaseya breach demanded a

$70 million ransom [

27]. Darkside is known for stealthy compromises such as the Colonial Pipeline incident, costing

$5 million [

28]. LockBit 3.0 has also carried out significant attacks, such as the Accenture breach, demanding a

$50 million ransom [

29].

Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs): Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs) have become a growing concern in recent malware trends, and are projected to reach a

$12.5 billion market by 2025 [

30]. APTs are characterized by their sophistication, advanced tactics, and prolonged, targeted campaigns against digital infrastructure for sabotage or espionage. They differ from conventional cyber threats in that they are more persistent and complex than other malware, such as ransomware.

APTs leverage obfuscation, anti-analysis tactics, and AI to evade detection and create zero-day exploits [

31]. It operates through a multistage process to infiltrate and persist within a network. They start with reconnaissance, gathering information via open-source intelligence (OSINT) and social engineering, followed by initial access by spear phishing or system exploits. Attackers establish control, escalate privileges, move laterally, and exfiltrate data while maintaining a stealth to evade detection.

Prominent APT attacks include Stuxnet, which disrupts Natanz’s centrifuges through zero-day vulnerabilities and fake software signatures [

32]. The SolarWinds attack is another example of APT that deploys malware via a supply chain compromise in the Orion system [

31].

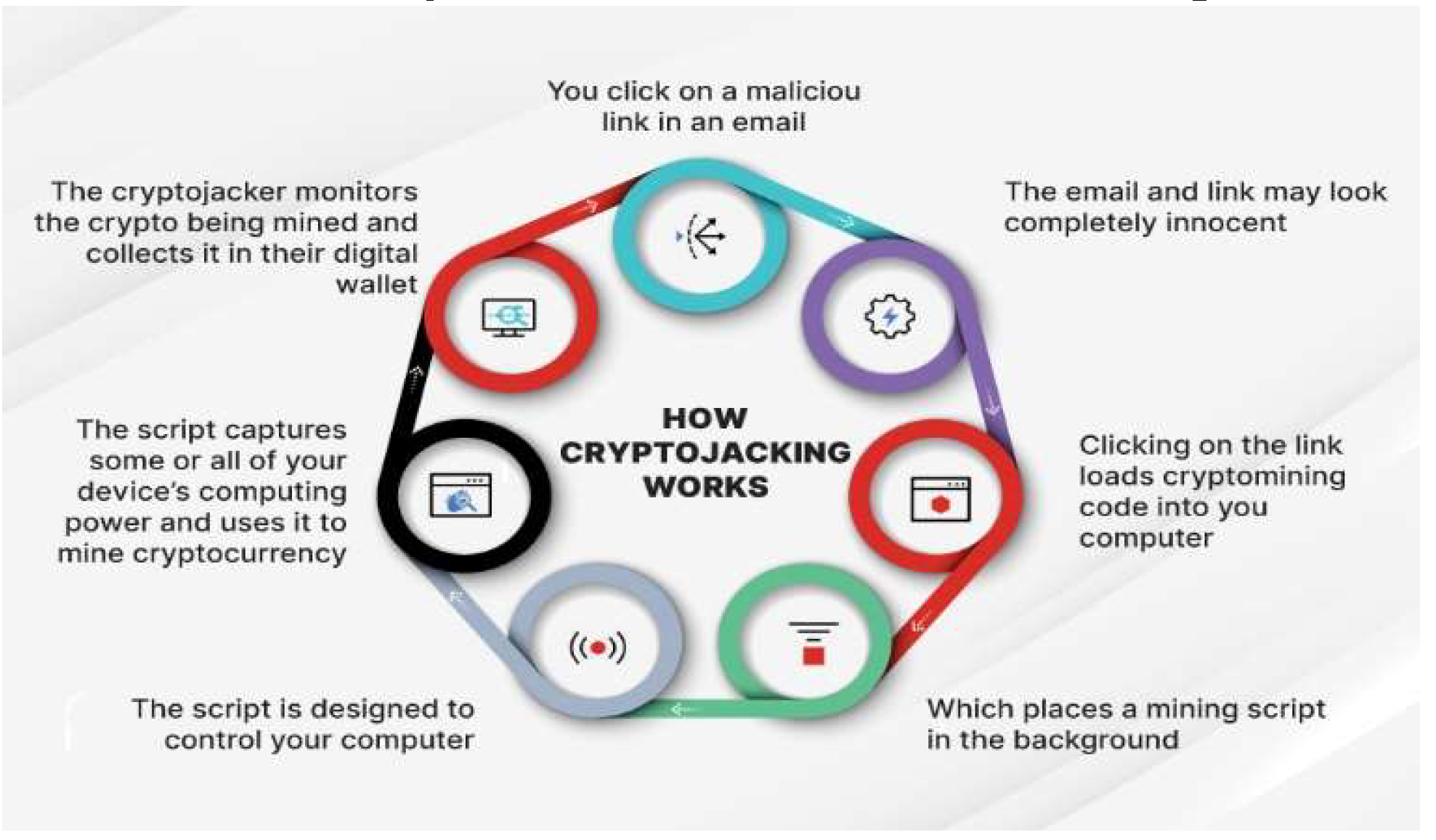

Cryptojacking: Cryptojacking is a stealthy cyberattack in which malware is typically injected via malicious links into a network of devices and runs covertly in the background to harness the victim’s computing resources for mining cryptocurrency. In 2023, cryptojacking incidents skyrocketed, exceeding the previous year’s total by early April and reaching

$1.06 billion by the year-end–a 659% increase [

33]. Unlike ransomware, cryptojacking avoids direct payment demands and uses obfuscation to avoid detection.

Figure 2 [

34] illustrates how this process works step-by-step.

Cryptojacking targets various platforms, including desktops, servers, mobile devices, and cloud services, using different forms of malware or scripts.

Browser-based cryptojacking: This form of cryptojacking uses malicious JavaScript on websites to exploit user devices for cryptocurrency mining. It requires no software installation but may cause increased CPU usage, slowing down, or overheating devices.

Host-based cryptojacking: In host-based cryptojacking, attackers misuse the CPU or GPU of a system to mine cryptocurrencies. Unlike browser-based methods, this approach involves direct installation of malicious scripts on a host, often through phishing or bundled software. These scripts exploit the system’s resources to convert cryptocurrencies.

Cloud cryptojacking: Cloud cryptojacking involves exploiting server and container vulnerabilities to mine cryptocurrency, impacting providers and customers through financial losses and reduced performance.

Notable cryptojacking incidents include the hacking of a European water utility, Tesla’s cloud breach, and the cryptojacking code hidden on the Los Angeles Times website in 2018 [

33,

34]. Moreover, in 2020, the U.S. Department of Defense found cryptojacking malware on its servers [

35], and in 2019, a Russian nuclear facility employee was fined

$7000 for mining Bitcoin illegally [

36].

Spyware: Spyware enables cybercriminals to infiltrate networks by stealing sensitive data such as login credentials, screenshots, and chat histories. Pegasus, a well-known spyware variant, steals data from mobile devices and leverages BYOD policies to infiltrate secure networks. It provides cybercriminals with insider access, enabling them to locate and compromise valuable assets such as emails, SMS messages, app data, and multimedia. Its ability to bypass multi-factor authentication by extracting one-time passwords makes it even more dangerous [

24].

Wiper malware: Wipers are malicious programs that permanently destroy user data and target both public and private computer networks. Threat actors use wipers to conceal their intrusion and to hinder the victim’s response. Nation-state attackers deploy them to disrupt supply chains and military operations, while “hacktivists” use them to impede business activities in response to perceived injustices [

37].

Recent examples include WhisperGate malware that targeted Ukraine in January 2022 [

38] and HermeticWiper, which impacted various Ukrainian organizations in February 2022 [

37].

Remote Access Trojans (RATs): RATs, a specific trojan type, are popular with cybercriminals for remotely controlling the endpoint devices. They trick users to run malicious codes by masking them as legitimate applications. Ghost, a Remote Access Trojan, controls the infected endpoints. Unlike typical malware, Ghost is manually deployed, suggesting that victims are already compromised by other malware [

24].

Understanding the current landscape of malware threats is crucial for developing robust countermeasures and improving the detection capabilities.

3.4. Malware Analysis

In this subsection, we discuss various malware analysis methods that are crucial for the development of malware detection systems. The main goal of malware analysis is to identify the characteristics and purposes of suspicious files. Significant approaches for conducting malware analysis across platforms like Windows, Linux, and Android include [

39]-

Static analysis

Dynamic analysis

Memory analysis and

Hybrid analysis

Static analysis techniques extract static signatures, features, or patterns from binary files without execution. This method is fast, secure, and efficient in identifying known malware samples, and does not require kernel privileges or a virtual machine. However, static analysis has significant limitations: it cannot examine malware strains using obfuscation techniques and is ineffective against malware that uses packers to compress and encrypt payloads [

40].

Conversely, dynamic analysis involves executing malware in a controlled environment to observe runtime behavior. This enhances the understanding of malware functionality and enables the identification of previously unknown or zero-day malware. However, this approach is often slower and more time-consuming [

40]. Additionally, dynamic analysis also has limitations in tracking highly sophisticated malware, such as fileless (memory-resident) malware.

Consequently, Memory analysis offers an alternative method for detecting malicious behaviors of fileless malware by capturing and examining volatile memory images during execution. While encryption and packing can conceal suspicious files, all processes are visible in the memory during runtime. Malware must disclose critical information (e.g., logs, code, and data segments) for operational functionality, making detection possible. Volatile memory analysis detects malware by examining its presence in the system’s RAM, identifying fileless malware that evades detection by not leaving traces on hard drives [

41].

The hybrid malware analysis methodology combines multiple analysis approaches, offering greater effectiveness than a single analysis technique.

3.5. Features Used in ML-Based Malware Detection

This subsection provides an overview of the features extracted from various platforms, each of which uses distinct file formats and yields different features. In Windows, malware features are extracted from executable (EXE) files, whereas Linux malware is analyzed using Executable and Linkable Format (ELF) files. In macOS, the Mach-O file format is used to analyse and extract the features. Android relies on APKs, and iOS utilizes IPA files. The APK file enables the extraction of static features from classes.dex files and dynamic features from the AndroidManifest.xml file [

42]. IoT platforms derive features from firmware binaries, whereas cloud environments use container images and VM disk files, such as Docker and VMDK, for feature extraction.

Table 2 classifies platform-specific features into static, dynamic, and memory-based features suited to different file formats and operating environments.

Static features derived from binaries or metadata without execution include file headers, opcode sequences, and metadata, which are essential for assessing executables and packages on Windows, Linux, macOS, Android, and iOS. Dynamic features capture behavior during execution, including system calls, API invocations, network activities, and registry or file system changes, aiding in the identification of complex or evasive malware. Memory features, such as memory allocation patterns and mapping, are vital for detecting sophisticated threats, particularly in IoT and cloud environments. This structured feature analysis underpins the implementation of machine learning models attached to each platform’s unique characteristics.

4. Malware Landscape Across Platforms

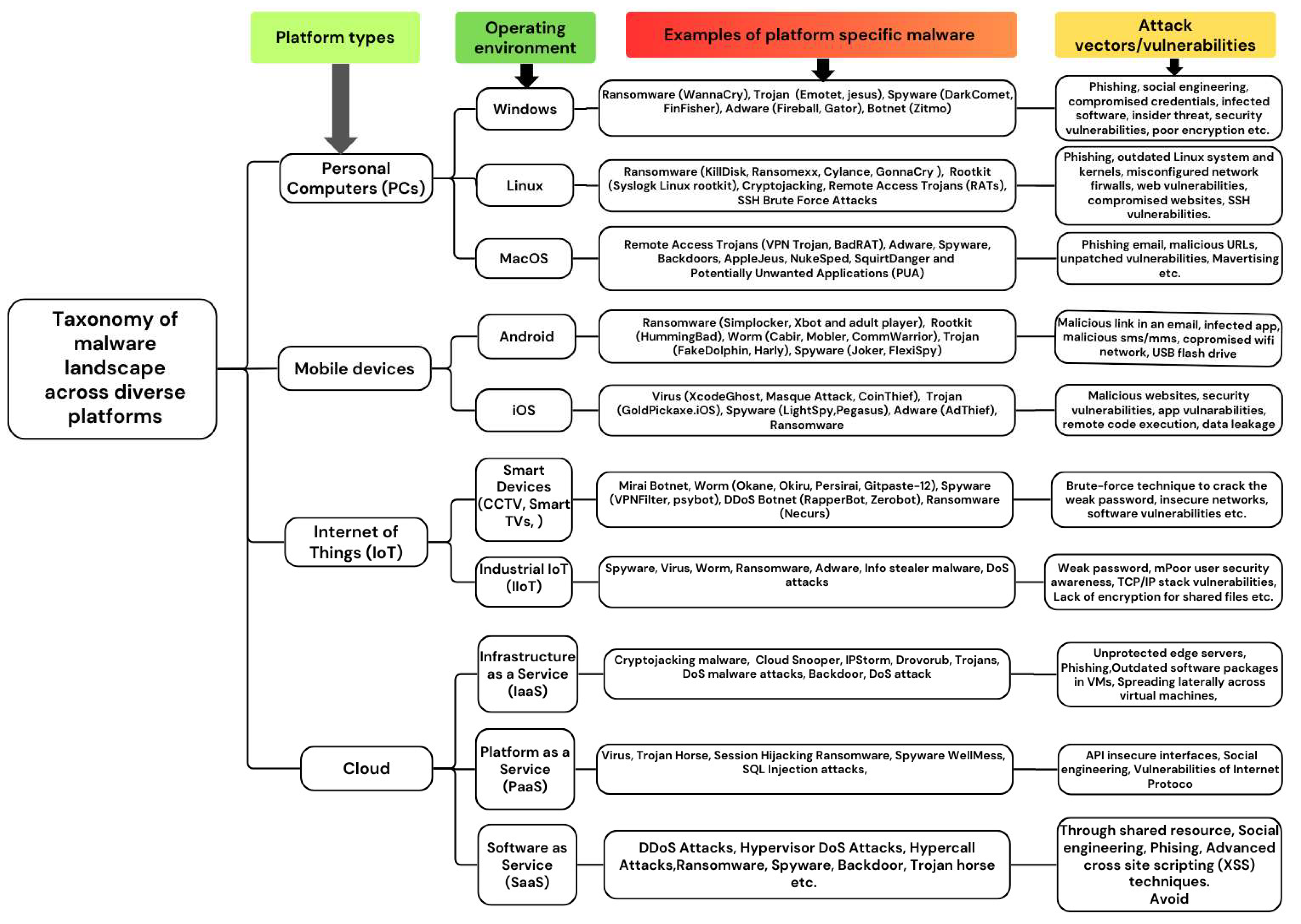

The proliferation of digital technologies has expanded the malware threat landscape across various platforms including PCs, mobile devices, IoT, and cloud systems. Understanding the targeted operating system or device is crucial to comprehending malware behavior, as malicious software is often crafted for specific platforms that exploit system-specific vulnerabilities. In this study, the terms “platform” and “operating system” will be utilized synonymously, and we classify the target platforms for malware into four primary categories: PCs, mobile devices, IoT and cloud systems. Each platform has unique vulnerabilities, attack vectors, and security issues that require distinct detection and mitigation strategies. This section provides an overview of the malware landscape across these platforms, as shown in

Figure 3.

4.1. PCs

The PC platform is a primary target for malware, facing various types that exploit specific vulnerabilities in Windows, macOS, and Linux environments. This study examines the malware landscape for each operating system, emphasizing common threats, typical attack vectors, and mitigation mechanisms.

4.1.1. Windows

The Windows platform remains a primary target for malware owing to its extensive use in personal and enterprise settings. Malware types include viruses, worms, trojans, ransomware, spyware, adware, and rootkits, each threatening system integrity and data security. Cybercriminals exploit phishing emails, malicious websites, software vulnerabilities, and removable media to initiate infection. Advanced techniques such as polymorphism, obfuscation, and encryption are used to avoid traditional detection, necessitating adaptive and robust detection mechanisms [

8]. The platform’s broad software ecosystem provides numerous entry points for attack. Although Microsoft employs security measures, such as Windows Defender and regular updates, their effectiveness depends on users practicing safe computing and maintaining updated systems. The impact of malware on Windows can lead to system performance issues, data theft, system crashes, and financial losses, thereby highlighting the significant consequences of these attacks.

4.1.2. Linux

Linux has become the leading operating system in multi-cloud environments, powering 78% of the world’s top websites. This widespread use has increased the scale and complexity of linux-based systems [

45]. The Linux OS supports various distributions for diverse hardware requirements, making it integral to many Internet-based desktop devices and a target for cybercriminals. The rise in Linux-based malware attacks is mainly due to the prevalence of IoT devices running Linux-based firmware, such as smart home assistants, security cameras, and industrial control systems. These devices often lack robust security mechanisms, making them susceptible to attacks that can compromise the ecosystem. In addition, as more companies adopt Linux-based servers and networks, hackers increasingly target these systems for potentially greater rewards. Trend Micro’s research shows that 90% of public cloud workloads run on Linux, further motivating hackers to develop Linux malware [

46]. Recently, Linux-based systems have become increasingly targeted for various malware attacks. According to the VMware threat report [

45], these devices face an increase in cryptojacking malware, remote access trojans (RATs), SSH brute force attacks, web shell malware, and ransomware. The Trend Micro Linux Threat Landscape Report indicated a 62% increase in ransomware attacks on Linux from 2022 to 2023. The report identified that KillDisk Ransomware, among others, specifically targeted financial institutions, exploiting phishing attacks and outdated Linux systems and kernels. This report also states that Webshell exploits are the most common Linux malware at 49.6%, followed by Trojans at 29.4%, whereas backdoors and crypto miners are less prevalent [

46]. Cybercriminals primarily exploit web vulnerabilities such as SQL injection, XSS, and SSRF to compromise web resources. They also targeted cloned websites, misconfigured firewalls, and SSH vulnerabilities to execute malware attacks on Linux systems.

4.1.3. macOS

The evolving macOS threat landscape necessitates greater vigilance from users and developers. Despite macOS’s reputation for robust security, it remains vulnerable to cyber threats in 2022; malware detection on macOS rose significantly by 165%, accounting for 6.2% of the total increase from the previous year [

47].

MacOS employs security features such as XProtect and Gatekeeper; however, they have limitations. XProtect’s signature-based detection is ineffective against unknown or modified malware and lacks the dynamic scanning capabilities of third-party EDR tools. Gatekeeper is another security feature that blocks unsigned or malicious Internet applications, verifies developer IDs, and checks for alterations after signing. However, attackers can bypass this by using stolen developer IDs or exploiting legitimate apps to run malicious code. Additionally, while Sandboxing applications limit access to vital system resources, attackers have devised techniques to escape and obtain illicit access [

47].

The most prevalent malware on macOS include adware, potentially unwanted programs (PUPs), backdoor spyware, remote access Trojans, stealers, ransomware, and other emerging malware types [

47,

48]. Over the years, new malware threats have emerged, including AppleJeus, which shifted tactics from Windows to macOS in 2018, and NukeSped, which functions as ransomware, spyware, and stealer and was detected in 2019. SquirtDanger, a macOS-targeting malware with advanced evasion techniques, was discovered in 2022 [

47]. Common attack vectors include malvertising, phishing emails, malicious URLs, and unpatched vulnerabilities with persistent macOS vulnerabilities.

4.2. Mobile Devices

The increasing prevalence of mobile devices in modern society has made them prime targets for malware, particularly for smartphones. Malware developers primarily target Android and iOS operating systems, which dominate the global mobile OS market.

4.2.1. Android

The widespread adoption of Android platforms on smartphones, tablets, and IoT devices has increased its vulnerability to malicious cyber-attacks. The flexibility, cost-effectiveness, and computing power of Android devices have increased their popularity. They offer user-friendly third-party applications, such as games, fitness, monitoring, and healthcare, accessible globally via on-demand internet connections. However, the widespread popularity of Android has made it susceptible to cyber-attack. A recent report revealed that over 438,000 mobile malware installation packages were detected in the third quarter of 2023, marking a 19% increase from the second quarter [

49]. Another report revealed that in Q2 2024, Android led the global mobile market with a 71.65% share, while iOS accounted for approximately 27.62% [

50]. Android platforms face a range of malware threats, including credential theft, privacy breaches, bank fraud, ransomware, adware, and SMS fraud. Therefore, the development of automatic Android malware detection methods is vital for protecting the system security and user privacy.

Android is an open-source Linux-based mobile OS that allows anyone to access and use its own code. Its architectural framework comprises several distinct layers: kernel, hardware abstraction layer, Android runtime, libraries, application framework, and applications. These components collectively serve to optimize the system efficiency and application performance. Android offers security mechanisms, such as sandboxing, permissions, and encryption to protect data and ensure app integrity [

51]. Android apps operate in isolated sandboxes with user-approved permissions for resources like cameras and Wi-Fi. Therefore, users should exercise caution when granting permissions because malicious apps can access sensitive resources once allowed.

Various forms of malware, such as SMS Trojans, Ransomware, Adware, Backdoors, Rootkits, Spyware, Botnets, and Installer malware, significantly threaten mobile device security [

52,

53]. Malware spreads on mobile devices through malicious links in emails or SMS, infected apps from Google Play Stores, third-party sources, or malicious Wi-Fi networks. Significant vulnerabilities in the Android OS include information gain, code execution, denial of service (DoS), overflow, SQL Injection, and privilege escalation [

53].

4.2.2. iOS

iOS, introduced in 2007, is a Unix-based operating system that powers popular Apple devices such as iPhones and iPads, ranking as the second most used mobile OS globally. The iOS architecture consists of four layers with specific functions: Core OS handles hardware interactions, Core Services provide data protection and storage features, media supports multimedia processing, and Cocoa Touch enables app development and user interface management [

53].

iOS offers robust security compared with Android through a closed system design incorporating device-level protection (e.g., PINs, remote wipe), system-level features (e.g., Secure Enclave, secure boot), and mandatory data encryption. Apple’s control over hardware and software makes jailbreaking and unauthorized access challenging. The iOS enhances security through sandboxing, encryption, and automatic data erasure. Applications are isolated from each other to prevent unauthorized access, whereas encryption protects files using hardware and software keys [

54]. iOS automatically grants most permissions, thereby reducing user involvement. In addition, the auto-erase feature wipes data after multiple incorrect passcode attempts, offering a higher level of security than Android [

55]. According to a McAfee report, iOS malware has surged in recent years, with a 70% increase in malware targeting iPhones and iPads by 2020 [

53]. The most common malware on the iOS platform are ransomware, spyware, viruses, trojans, and adware [

53,

56]. Notable attacks include Pegasus, which exploits zero-day vulnerabilities for surveillance [

57]. Additionally, LightSpy Spyware, a sophisticated iOS implant, was infiltrated via compromised news sites [

58]. Common vulnerabilities, such as memory overflow, remote code execution, and data leakage, present significant risks to iOS users, highlighting the need for enhanced device security.

4.3. IoT Platform

The Internet of Things (IoT), introduced by Ashton in 1999, refers to a network of interconnected devices that collect and exchange data via the Internet or other networks. This is a combination of devices, sensors, networks, computing resources, and software tools. IoT devices fall into two main categories: Consumer IoT, such as personal and wearable smart devices, and Industrial IoT (IIoT), which includes interconnected industrial machinery and energy management devices.

The number of IoT devices is increasing significantly every year. According to Statista, global IoT devices will nearly double from 15.9 billion in 2023 to over 32.1 billion by 2030. By 2033, China will have the highest number of IoT devices, with approximately 8 billion consumer devices [

59]. However, the rapid rise of IoT coupled with insufficient security measures has made these devices prime targets for malware. Recent reports from Zscaler ThreatLabz show a 400% increase in IoT malware attacks [

60]. High-profile incidents, such as the Mirai botnet in 2016, exploit weak passwords and unpatched vulnerabilities, enabling DDoS attacks and data exfiltration [

60]. IoT malware also takes advantage of other vulnerabilities, such as the absence of software and security updates, insecure networks, poor user security awareness, TCP/IP stack vulnerabilities, and a lack of encryption. Modern IoT malware, including Okane, VPNFilter, and Necurs, increasingly employs brute-force methods, spyware tactics, and anti-virtualization techniques to gain access to devices [

14].

4.4. Cloud Environments

Cloud computing enables remote access to computing resources such as storage, applications, networks, and servers via an Internet connection. Conversely, cloud malware is a cyberattack that targets cloud platforms with malicious code or services.

Cloud computing offers three types of services: Platform as a Service (PaaS), Software as a Service (SaaS), and Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS). PaaS provides an environment for programmers to develop, deploy, and test applications, as exemplified by the Azure and Google App Engine. SaaS supports all applications within the cloud environment such as email and office software. IaaS offers hardware resources, computing capabilities, storage, servers, networking devices, and virtual machines [

19,

61]. Common examples of cloud malware include DDoS Attacks, Hypervisor DoS Attacks, Hypercall Attacks (exploits the hypervisor to gain cloud control), Hyperjacking (when an attacker takes control of a virtual machine for malicious purposes), Exploiting Live Migrations (moves a VM or application without client disconnection from one physical location to another), Ransomware, Spyware, Backdoor, Trojan horse etc. [

19,

62].

5. Machine Learning Algorithms for Malware Detection

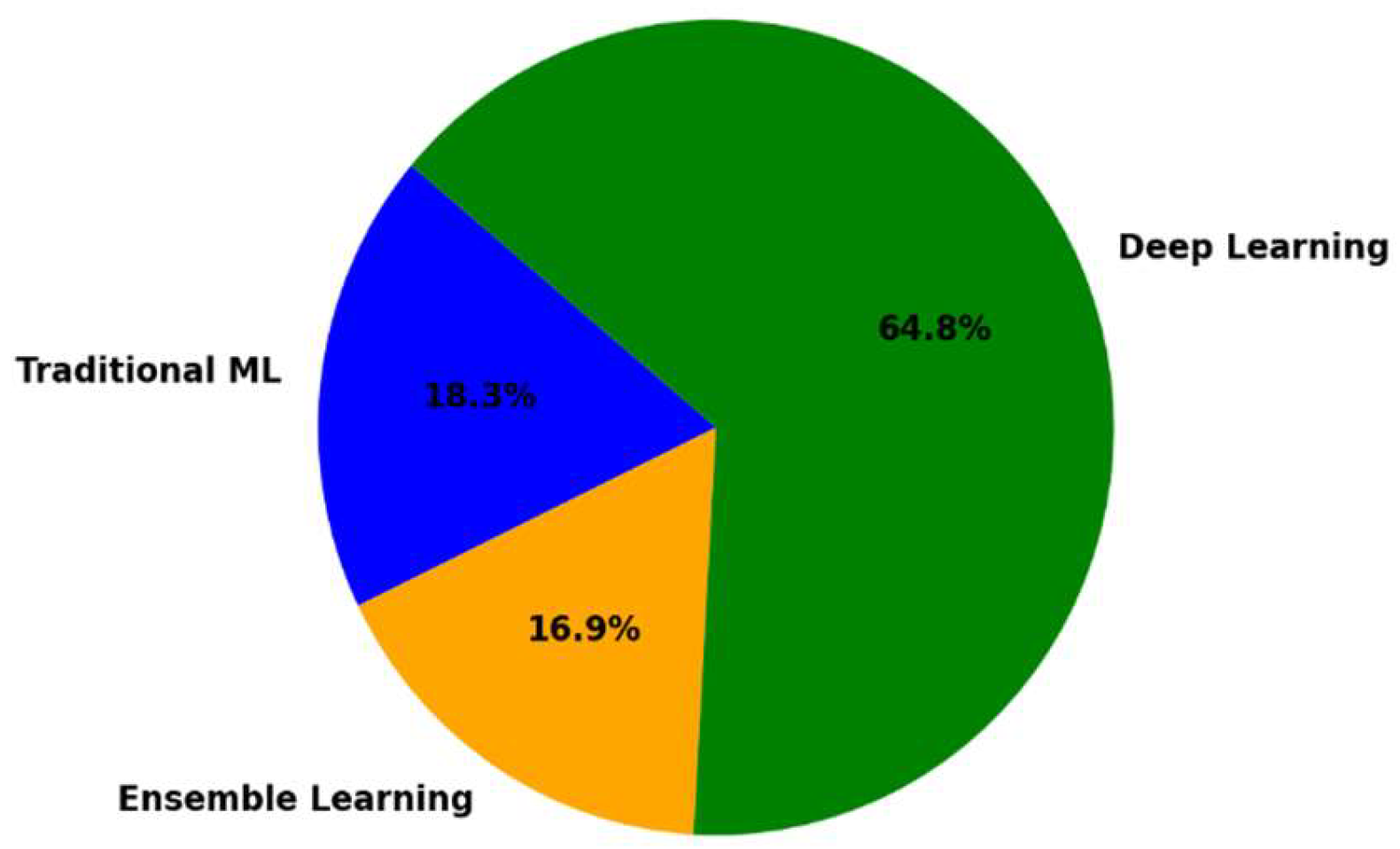

In this section, we present a summary of various machine learning algorithms used for malware detection on diverse platforms, including traditional, ensemble, and advanced deep learning approaches, as outlined in

Table 3. Traditional algorithms such as SVM, KNN, and DT are simple yet effective in classifying malicious and benign samples. Ensemble methods, such as RF and Gradient Boosting, enhance the accuracy and robustness by combining multiple models. Deep learning algorithms, including CNN and transformers, excel in processing complex, high-dimensional, and sequential malware data. Techniques such as GAN and Transfer Learning address challenges such as limited datasets and feature extraction. The table underscores the diversity of machine learning methodologies in malware detection. The analysis outcomes of the table are reflected in the pie chart shown in

Figure 4, highlighting the key trends in machine learning techniques for malware detection.

6. Application of Machine Learning on Malware Detection

This section reviews recent studies that have utilized the various ML algorithms discussed in

Section 5 to develop malware detection models for Windows, Linux, Android, IoT, and cloud platforms.

6.1. PC (Personal Computers) Malware Detection

This section covers malware detection on personal computers, including Windows, Linux, and macOS. Windows, the most widely used OS, are the primary target for malware. Despite Linux’s robust permission-based architecture, it is facing growing threats in the server and enterprise settings. With its increasing popularity, macOS has increased the risk of malware. Detection methods employ static, dynamic, and hybrid analyses, which are frequently enhanced using machine learning, to counter evolving threats.

6.1.1. Malware Detection in Windows platform

In this subsection, we provide an extensive review of machine learning-based malware detection techniques for the Windows platform are summarized in

Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of reviewed models for Windows-based malware detection: dataset sources, feature details, and experimental result.

Table 4.

Summary of reviewed models for Windows-based malware detection: dataset sources, feature details, and experimental result.

| Reference |

Data source |

Feature category |

Features |

ML algorithms |

Result (accuracy) |

Limitations |

| Static feature-based malware detection |

| [63] |

Malimg |

Static |

Opcode sequences |

Deep RNN |

96% |

It requires significant computational resources |

| [73] |

Microsoft BIG 2015 |

Static |

Opcodes, images, byte sequence, etc |

DNN, LSTM, and CNN. |

98.35% |

It is useless against zero-day malware. |

| [102] |

BIG 2015, Malimg, MaleVis and Malicia dataset |

Static |

2D images |

DenseNet |

98.23% |

It has high false negatives and highly imbalanced datasets |

| [74] |

Microsoft BIG 2015 |

Static |

Image-based opcode features |

CNN |

99.12% |

Outdated dataset |

| [103] |

Malimg dataset, Microsoft BIG 2015 |

Static |

Grayscale images from PE files |

VGG16, VGG19, ResNet50, and inceptionV3 |

98.92% |

Cannot detect advanced-packed malware |

| [106] |

Malimg |

Static |

Static signatures |

ATT-DNNs |

98.09% |

Cannot detect obfuscated malware |

| [75] |

Malware API-class |

Static |

Executable file to static images |

CNN |

98.00% |

_ |

| [76] |

VirusShare, Hybrid-Analysis |

Static |

Executable file to static images |

Xception Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) |

98.20% |

_ |

| [107] |

Microsoft BIG 2015 |

Static |

Malware binary files into static images |

DNN |

97.80% |

_ |

| Dynamic feature-based malware detection |

| [92] |

VirusShare |

Dynamic |

Sequences of API calls |

Bi-LSTM |

97.31% |

Limited to execute samples in a Windows 7 environment. |

| [108] |

Custom datasets |

Dynamic |

Sequences of API calls |

Markov chain representation |

99.7% |

- |

| [109] |

VirusTotal |

Dynamic |

API calls |

LSTM |

95% |

Limited to execute samples in a Windows 7 environment. |

| [93] |

VirusTotal |

Dynamic |

API call sequences |

LSTM and GRU |

96.8% |

Highly imbalanced dataset |

| [64] |

CA Tech-

neologises VET Zoo |

Dynamic |

Run time behaviour |

MRed, ReliefF, SVM |

99.499% |

High computational complexity |

| [94] |

Audit log events |

Dynamic |

Process names, action types, and accessed file |

LSTM |

91.05% |

High false positives and lack of scalability |

| [77] |

Multiclass dataset (Ember Dataset, private dataset) |

Dynamic |

loaded DLLs, registry changes, API call sequences, file changes, and |

CNN-LSTM |

96.8% |

Susceptible to adversarial attacks |

| Hybrid feature-based Malware Detection Techniques |

| [78] |

VirusTotal |

Hybrid (Static and dynamic)

|

Combination of static and dynamic features (PE section, PE import, PE API, and PE images) |

CNN |

97% |

Failed to validate the robustness against adversarial attacks |

| [71] |

The Korea Internet & Security Agency (KISA) |

Hybrid |

Size of file and

Header, Counts of file sections. Entropy, File system changes API call, DLL loaded info, network activities, etc. |

RF, MLP |

85.1% |

Extensive time is needed for feature extraction |

| [104] |

VirusShare |

Hybrid |

Image-based static and dynamic features |

VGG16 |

94.70% |

- |

| [110] |

VirusShare |

Hybrid |

Function Length Frequency

Representation, Registry activities, API calls, and file operation features |

SVM |

97.10% |

Small dataset |

| [79] |

VirusTotal |

Hybrid |

Opcodes and system calls |

CNN, LSTM, and an attention-based LSTM |

99% |

Lack of diverse features. |

| Memory-feature-based malware detection techniques. |

| [80] |

Dumpware10 |

Memory |

Memory images of running processes |

CNN |

98% |

Malware processing cost is high under limited resource capabilities |

| [81] |

Dumpware10, BIG2015 dataset |

Memory |

Memory images of running processes |

GAN and CNN |

99.86% for BIG2015 dataset |

Only one type of data, like bytes, is used. Need to make the dataset more diverse. |

| [82] |

CIC-MalMem-2022

https://www.unb.ca/cic/datasets/malmem-2022.html |

Memory |

Memory images of running processes |

CNN and MLP |

99.8% |

Training time complexity and vulnerability to adversarial attacks |

| [68] |

CIC-MalMem-2022

https://www.unb.ca/cic/datasets/malmem-2022.html

|

Memory |

Multi-memory features |

RF, DT, LR, MLP and CNN |

99.89% |

- |

Static feature-Based Malware Detection Techniques

Jeon and Moon [

63] proposed a DL-based malware detection method using static opcode sequences with dynamic RNN and CNN. A convolutional autoencoder compresses long opcode sequences, and a recurrent neural network classifies malware using the features generated by the autoencoder. This method achieved 96% accuracy and 95% true-positive rate. However, it requires substantial computational resources owing to the inter-procedural control-flow analysis, making it less suitable for resource-limited systems. Snow et al. [

73] developed a multi-modal deep-learning-based malware detection method using the Microsoft BIG 2015 dataset. Although the model achieved a high accuracy rate of 98.35%, it proved ineffective against zero-day malware that evaded detection with new static signatures. A previous study [

102] employed a CNN-based pre-trained DenseNet model for malware detection by converting benign and malicious binaries into 2D images. Experiments on Malimg, BIG 2015, MaleVis, and Malicia datasets showed 98.23% accuracy on Malimg but revealed high false negatives and used highly imbalanced datasets. Darem et al. [

74] implemented a deep CNN-based model to detect malware using opcode-level features from malware and benign binary files converted into images for training. The model achieved a detection rate of 99.12% %on the Microsoft BIG 2015 dataset. However, outdated datasets can affect the detection of new and unseen malware. Kumar & Janet [

103] proposed an image-based deep transfer learning model for detecting Windows malware using a pre-trained deep CNN. The model efficiently extracts high-level features from grayscale images of Windows executables, conserving resources and time; however, it struggles to identify advanced-packed malware. A study in [

106] introduced an attention-based deep neural network (ATT-DNN) for malware detection, extracting static features from executable files. Despite achieving a high accuracy of 98.09%, its use is limited to malware detection based on static signatures. The research in [

75,

76,

107] also focused on malware detection via static image analysis.

Dynamic Feature-Based Malware-Detection Techniques

Li et al. [

92] developed a DL model for malware detection in executables using API call sequences within a Cuckoo sandbox, achieving an F1-score of 0.9724 and 97.31% accuracy on new sequences. The limitations of this study include its focus on Windows 7 executables and the potentially reduced effectiveness against zero-day malware over time. In [

108], contextual analysis of API call sequences was utilized to enhance the dynamic detection and prediction of Windows malware, thereby improving both accuracy and adaptability to evolving threats. By employing the Markov chain method, they achieved an average accuracy of 99.7%. Catak et al. [

109] proposed an LSTM-based malware detection method that achieved 95% accuracy and 0.83 F1 score using a behavioral dataset of API calls. They also released a new, publicly available API call dataset for malware detection. Aditya et al. [

93] used LSTM and GRU deep learning models to classify malware based on API call sequences and achieved 96.8% accuracy with LSTM. However, their dataset was highly imbalanced, with only 1,035 benign samples of 8,142. In [

64], a hybrid framework combining multiple complementary filters with a wrapper feature selection method was proposed to identify critical run-time behavioral traits of malware. The ML algorithms, including MRed, SVM, and Fisher, achieved a detection accuracy of 99.499%. Ring et al. [

94] used an LSTM-based model to detect malware based on audit-log features. However, it suffers from high false positive rates and lacks the evaluation of larger datasets to assess the model’s scalability. Jindal et al. [

77] proposed Neurlux, a stacked ensemble of CNN-LSTM with an attention mechanism to detect malware in Windows systems using dynamic features effectively but is susceptible to adversarial attacks.

Hybrid-Feature-Based Malware Detection Techniques

Hybrid feature-based learning approaches have shown promise in cybersecurity, outperforming single-type feature methods. By combining diverse feature types, such as static, dynamic, and memory-based, these techniques enable learning from multiple semantic perspectives, leading to an enhanced model accuracy for malware detection and classification.

The authors of article [

78] created a CNN-based hybrid malware classification model for Windows, integrating static features from the executable section, static API call imports, dynamic API calls, and executable file images, achieving a detection accuracy of 97%. However, this method does not validate the effectiveness of the combined feature sets against adversarial attacks. AI-HydRa [

71] represents an advanced hybrid malware classification method that combines RF and deep learning, achieving a mean detection rate of 0.851 with a standard deviation of 0.00588 over three tests. Huang et al. [

104] introduced a hybrid method using static images and dynamic API call sequence visualizations to classify malicious behaviors. Utilizing a CNN (VGG16) for feature extraction, the technique attained 94.70% accuracy but had difficulty accurately identifying specific malware types, including password-stealing (PSW) Trojans and some outdated variants. RansHunt [

110] integrated static and dynamic features for improved ransomware detection using an SVM, achieving an accuracy of 97.10%, outperforming traditional anti-virus solutions. Darabian et al. [

79] used static and dynamic features from 1,500 cryptojacking malware samples. They used opcodes and system calls to construct CNN, LSTM, and attention-based LSTM classification models, achieving 95% accuracy in static analysis and 99% accuracy in dynamic analysis.

Karbab et al. [

111] introduced SwiftR, an approach that detects ransomware attacks by integrating various static and dynamic features from benign and malicious executable file reports. The proposed method achieved an F1 score of 98%.

Memory-Feature-Based Malware Detection Techniques

Malware detection using static or dynamic analysis is insufficient for advanced memory-resident malware and obfuscated malware. Thus, contemporary research emphasizes memory analysis methods that are effective in detecting sophisticated malware variants [

41]. The study [

80] developed a CNN model was developed that uses memory images of both suspicious and benign processes to detect malware attacks with a detection rate of 98%, leveraging features extracted from grey-level co-occurrence matrices and local binary patterns. Another study [

81] proposed a DL-based approach that integrated GAN and CNN models, achieving 99.60% detection accuracy on unseen samples when tested on the DumpWare10 dataset to identify advanced malware by visualizing running processes. In addition, Naeem et al. [

82] developed a high-performance stacked CNN and MLP model using memory images that achieved an accuracy of 99.8%. However, it has limitations in terms of the training time complexity and susceptibility to adversarial attacks. In [

68], the authors used the latest dataset, the CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset, to develop a CNN-based detection model that detects obfuscated malware in memory.

Summary of Key Trends and Insights on Malware Detection in Windows Platforms

A summary of the malware detection methods for Windows is presented in

Table 4. The table outlines the studies with respect to their data collection source, feature type, features, ML algorithms used, detection accuracies, and limitations.

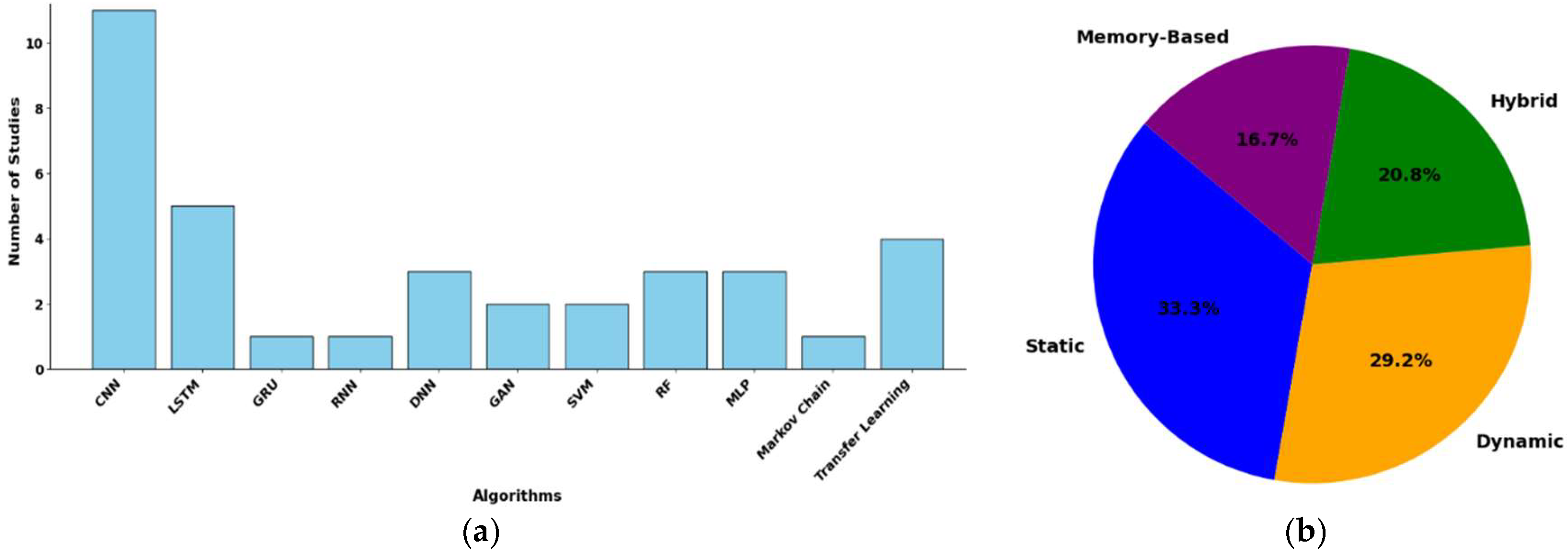

Figure 5 illustrates the distribution of the techniques, features, and evaluation datasets used in these studies.

Dataset evaluation: Table 4 reveals that many recent studies have relied on outdated datasets, such as Malimg (2011) and Microsoft BIG 2015. VirusTotal and Virus Share remain the most popular data sources for Windows malware detection systems, followed by dumpware10 and Hybrid Analysis. com. In contrast, newer datasets such as CIC-MalMem-2022 provide updated benchmarks. However, the prevalence of outdated datasets and the lack of diversity in recent studies have limited their effectiveness against zero-day malware and emerging threats.

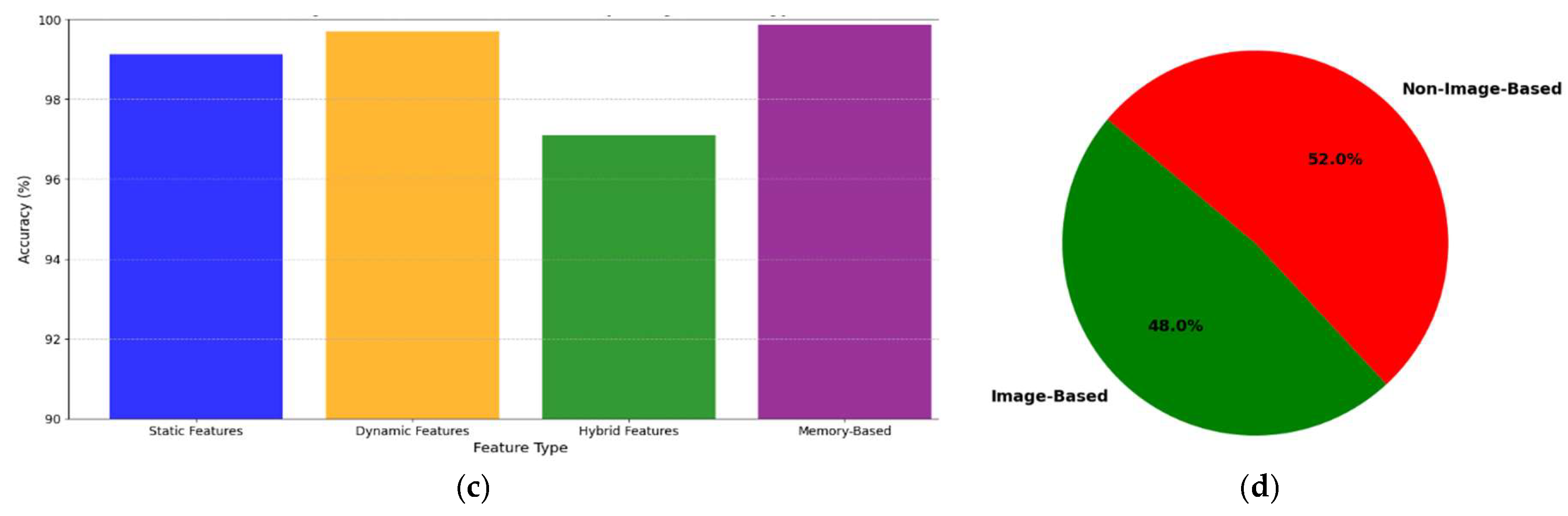

Detection algorithms used in the studies: The bar chart in

Figure 5 (a) illustrates the distribution of detection algorithms employed in various detection techniques, highlighting their relative popularity among the studies. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are the most utilized algorithms, likely because of their efficiency in handling images and spatial data. LSTM networks also stand out and are likely to be favored because of their strength in temporal or sequential data processing. Algorithms such as GANs and transfer learning are used less frequently and hint at emerging or specialized applications. However, GRU, RNN, and Markov Chains appear less favored, possibly because of their limited generalizability or lower performance in detection tasks. The chart collectively underscores the significance of choosing algorithms that align with the nature of the problem and the data characteristics.

Detection feature type: The chart 5 (b) highlights the distribution of feature types in malware detection techniques. Static features lead by 33.3%, favoring their simplicity and effectiveness against known malware. Dynamic features follow closely at 29.2%, offering strong runtime analysis capabilities but requiring controlled execution environments. Hybrid features, at 20.8%, integrate static and dynamic methods for comprehensive detection but involve higher computational demands. Memory-based features, representing 16.7%, are powerful for analyzing runtime data, such as API calls, but are less commonly used because of their resource-intensive nature.

Accuracy of malware detection techniques by feature type: The bar chart as outlined in

Figure 5 (c) compares the accuracy of malware detection techniques based on four feature types: static, dynamic, hybrid, and memory. Memory-based features achieved the highest accuracy (~99.89%), demonstrating their effectiveness in capturing runtime behaviors, although they may require higher computational resources. Dynamic features also perform well (~99.49%), leveraging runtime analysis, whereas static features (~99.12%) offer robust results through code and signature analysis. Hybrid features (~99%) combine static and dynamic methods but do not significantly outperform individual approaches. Overall, memory-based and dynamic features demonstrated the highest potential for accurate malware detection.

Image-based vs. non-image-based detection techniques: The pie chart in

Figure 5 (d) shows a close competition between the non-image-based (52%) and image-based (48%) detection methods. While non-image-based methods lead slightly because of their flexibility with diverse data types, image-based approaches are emerging as powerful tools in malware detection. By converting malware binaries into images, image-based methods use CNNs to analyze spatial patterns and effectively identify complex obfuscated malware. The availability of labelled malware datasets, efficient pre-trained models, and generalization capabilities further drive their adoption, reflecting the growing significance and scalability of image-based methods in modern malware detection.

6.1.2. Malware Detection in Linux OS

Researchers have also utilized various ML algorithms to detect malware attacks on Linux systems. The ML-based Linux detection techniques are listed in

Table 5. Xu et al. [

105] developed a graph-based Linux malware detection system called HawkEye that achieved 96.82% accuracy. Hwang et al. [

112] also demonstrated the effectiveness of deep learning for Linux threat detection, using a large dataset of 10,000 malicious and 10,000 benign files to train and test a DNN model. Bai et al. [

72] proposed a Linux malware detection method that analyzes system calls in ELF executable symbol tables using 756 benign and 763 malware ELF samples. They achieved up to 98% accuracy with various classifiers, including J48, random forest, AdaBoostM1, and IBk. Landman and Nissim’s Deep-Hook [

83] used CNNs to analyze VM-captured memory dumps and identify Linux malware with up to 99.9% accuracy. Similarly, another study [

43] classified malware using behavioral features from volatile memory.

6.1.3. Malware Detection in macOS

Despite the rising threats of OS X malware, research on its detection remains scarce, with only a few studies focusing on malware detection on the macOS platform. For example, a study [

113] proposed OS X malware and rootkit detection by analyzing static file structures and tracing memory activities. Pajouh et al. [

114] developed an SVM model with novel library call weighting for OS X malware detection, attaining 91% accuracy on a balanced dataset. SMOTE-enhanced datasets increased the accuracy to 96%, with slight false alarm increases, indicating that larger synthetic datasets enhance accuracy, but may impact false-positive rates.

6.2. Malware Detection in Mobile Platform

The increase in mobile device usage, mainly Android, has led to increased malware threats. This section reviews machine learning techniques for detecting malicious applications on both Android and iOS platforms.

6.2.1. Android Malware Detection

This subsection examines ML-based Android malware detection techniques categorized by APK file features, with the dataset details summarized in

Table 6.

Static Feature-Based Malware Detection Techniques

A study [

115] proposed GDroid, a graph convolutional neural network model for detecting Android malware through API call patterns using static analysis. Although effective in detecting malicious apps, its accuracy decreases in real-world Android devices.

Pektaş and Acarman [

84] proposed a CNN- and LSTM-based model utilizing static features, including opcodes, API calls, and call graphs, for Android malware detection. Despite achieving 91.42% accuracy and 91.91% F-measure on unknown samples, the model’s dependence on static features may restrict its effectiveness against obfuscated malware. Similarly, in [

69], the authors proposed H-LIME, a novel XAI method that enhances LIME by incorporating opcode-sequence hierarchy for better Android malware detection explanations. They evaluated H-LIME using the MalDroid-2020 dataset, and H-LIME outperformed LIME in explanation quality and efficiency, but they faced challenges with shorter programs in real-world malware. Lakshmanarao and Shashi [

95] created an LSTM-based malware detection model using opcode sequences from Android apps, achieving 96% accuracy, albeit on a limited dataset of 1,500 apps. Potha et al. [

70] created an ensemble model combining LR, MLP, and Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD), demonstrating that larger, homogeneous ensembles with feature selection outperformed smaller ones, achieving strong AUC and accuracy on Android malware datasets. Furthermore, Aamir et al. [

85] introduced the AMDDL model, achieving a 99.92% accuracy in malware detection using CNNs. This study highlights the challenges related to limited malware diversity, deep learning interpretability, and scalability.

Dynamic Feature-Based Malware Detection Techniques

Ma et al. [

96] proposed Droidect, a Bi-LSTM-based model for classifying malicious Android apps, achieving 97.22% accuracy on a dataset of 11,982 benign and 9,616 malicious files. Despite its success, this model suffers from long detection times. Wang et al. [

116] presented a malware detection technique employing network traffic analysis and the C4.5 algorithm, achieving a 97.89% detection rate on the Drebin dataset, outperforming current methods. The study in [

97] introduced MemDroid, an LSTM-based detection method trained on Androzoo malware samples. Apps were run in a sandbox to capture system call sequences, which were used to train the LSTM classifier, achieving 99.23% malware detection accuracy. The study in [

98] used LSTM to develop classifiers for detecting Android malware via dynamic API and system calls, achieving F1-scores of 0.967 and 0.968, respectively, across different datasets.

Hybrid-Feature-Based Malware Detection Techniques

Alzaylaee et al. [

65] introduced DL-Droid, a deep learning-based framework for Android malware detection using static and dynamic analysis. They achieved 97.8% detection with dynamic features and 99.6% with combined features, taking 190 s/app on average. Saracino et al. [

52] introduced MADAM, an Android malware detection system analyzing kernel, application, user, and package-level features. MADAM detected over 96% of malicious apps in a 2800-app test but is susceptible to mimicry attacks and cannot identify unknown malware. Wu et al. [

99] presented DeepCatr, a hybrid learning approach for Android malware detection, which combines text mining and call graphs with bidirectional LSTM and graph neural networks, achieving accuracies of 95.94% and 95.83% on 18,628 samples. Mahdavifar et al. [

101] created a semi-supervised deep learning model for Android malware detection, employing a stacked auto-encoder trained on hybrid features, obtaining a 98.28% accuracy and 1.16% false positive rate.

Memory-Feature-Based Malware Detection Techniques

Memory analysis has been utilized to develop deep learning models for detecting obfuscated and memory-resident Android malware. A framework combining weak learners (CNNs) and a meta-learner (MLP) to create a deep-stacked ensemble model along with an explainable AI approach for result interpretation and validation was proposed by Naeem et al. [

86]. The framework achieved an accuracy of 94.3% using 2,375 images in an empirical evaluation.

Summary of Research Trends on Malware Detection in the Android Platform

Table 6 summarizes mobile device malware detection systems, including datasets, features, detection algorithms, and study accuracy.

Figure 6 shows the distribution of the dataset sources, techniques, and features used in these studies.

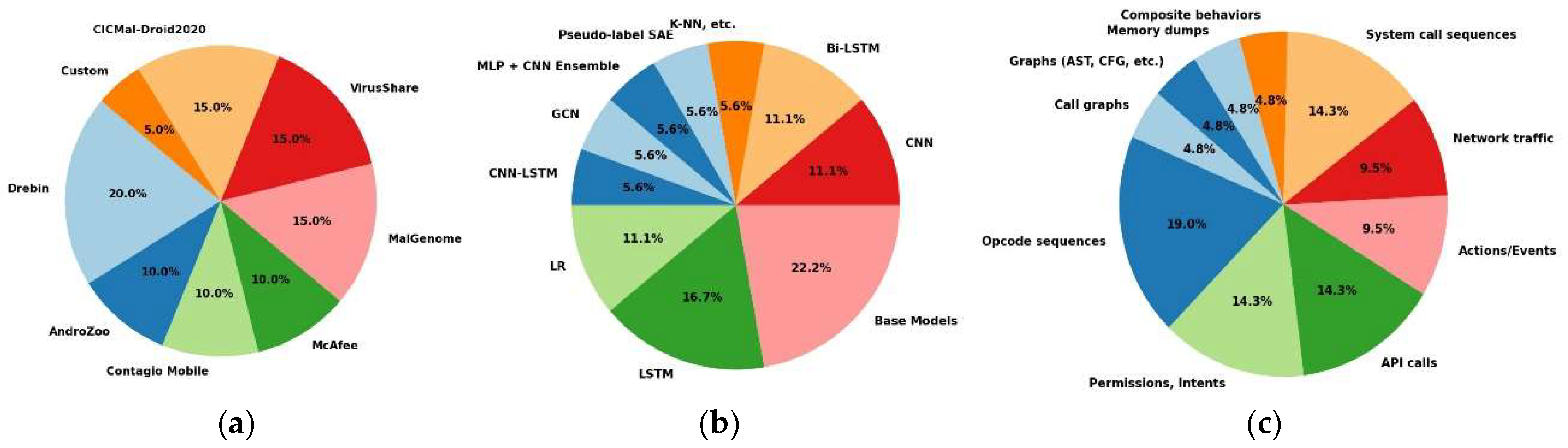

Proportion of datasets used: The pie chart in

Figure 6 (a) reveals a clear preference for established datasets in Android malware detection studies. Drebin emerges as the most-used dataset (31%), owing to its extensive malware diversity and widespread acceptance as a benchmark in the field. Medium-utilized datasets, including MalGenome, VirusShare, and CICMal-Droid2020 (23% each), are valued for their reliability and growing prominence in the evaluation of detection techniques. The relatively low adoption of custom datasets highlights the focus on standardized datasets, limiting opportunities for novel malware detection approaches tailored to evolving threats.

Detection algorithms: The pie chart in

Figure 6 (b) demonstrates that base models (31%), including Logistic Regression and Random Forest, are the most commonly used detection algorithms, valued for their reliability, simplicity, and ease of implementation. Deep learning methods, such as LSTM (23%) and CNN (15%), are gaining popularity owing to their ability to process complex and large-scale malware patterns effectively. Hybrid techniques (8%), ensemble models (8%), and exploratory approaches, such as Pseudo-label SAE and K-NN (8% each), showcase ongoing innovations aimed at improving detection accuracy and robustness. This distribution underscores the balance between traditional dependable methods and modern complexity-driven approaches to malware detection.

Detection features: As shown in

Figure 6 (c), the chart indicates that opcode sequences (31%) are the most commonly used features because of their effectiveness in static analysis. Permissions, intents, and API calls (23% each) are essential for identifying behavioral anomalies. System call sequences (23%) and network traffic (15%) are gaining prominence in runtime analyses. Composite behaviors and memory dumps (8% each) remain underexplored, likely due to their complexity and resource demands

6.2.2. Malware Detection in iOS

In [

117], the authors focused on identifying iOS malware using static analysis and machine learning, achieving a high precision of 0.971 and recall of 1.0. It addresses the underexplored domain of iOS malware detection owing to the platform’s closed source nature. Zhou et al. [

118] examine the risks of legitimate applications being hijacked for malware communication. They presented the ChanDet model to identify potential channel applications and proposed mitigation strategies. Mercaldo and Santone [

119] successfully classified 50,000 Android and 230 iOS malware samples using deep learning on grayscale images of executables, tackling obfuscation and false positives.

Summary of Research Trends on Malware Detection in iOs Platform

The current literature highlights advancements in iOS malware detection, leveraging machine learning and static analysis to address the platform’s closed-source challenges. Researchers have introduced high-precision models and deep learning techniques, such as those using executable images, to mitigate obfuscation. Despite these advancements, challenges such as limited datasets, lack of hybrid analysis, and insufficient attention to real-time cross-platform threats persist. Future work should focus on expanding the datasets, utilizing transfer learning, enhancing anti-obfuscation methods, and developing comprehensive detection frameworks.

6.3. Malware Detection in IoT Platform

This section compares the surveys on machine-learning-based malware detection in IoT, which are summarized in

Table 7.

Ali et al. [

66] used machine learning algorithms on the IoT-23 dataset to detect IoT network anomalies. The RF algorithm demonstrated the highest efficacy, achieving 99.5% accuracy. Sudheera et al. [

87] introduced Adept, a distributed framework that detects and classifies attack stages in IoT networks through local anomaly detection, pattern mining for correlated alerts, and machine learning-based classification. This method can identify five times more attack patterns with 99% accuracy in classifying attack stages. Vasan et al. [

88] proposed a cross-architectural malware detection method suitable for diverse IoT processor architectures, such as MIPS, PowerPC, and SPARC.

Researchers have used sandboxing as a dynamic method to detect malware in IoT environments. However, existing sandboxes are inadequate for resource-limited IoT settings, lack support for diverse CPU architectures, and do not offer library sharing options [

120]. Hai-Viet et al. [

89] proposed an IoT botnet detection approach using system call graphs and a one-class CNN classifier, which improved sandboxing to capture system behaviors and utilized graph features for robust detection, overcoming dataset imbalance and architectural constraints, attaining 97% accuracy. Jeon et al. [

100] introduced HyMalD, a hybrid IoT malware detection method using Bi-LSTM and SPP-Net to analyze static and dynamic features, extracting opcode and API call sequences for classification. It achieved 92.5% accuracy, surpassing the 92.09% accuracy of the static analysis. Researchers have now converted network traffic or OpCode into 2D images for malware detection using visual methods. Shire et al. [

90] utilized visual detection techniques in IoT malware detection, transforming network traffic into 2D images for machine learning analysis. He et al. [

67] proposed an efficient and scalable lightweight IoT intrusion detection method utilizing feature grouping, which attained over 99.5% accuracy on three public IoT datasets while consuming fewer computational resources than baseline methods. Jiang et al. [

91] proposed FGMD, a framework that protects IoT intrusion detectors from adversarial attacks, preserving efficacy and performance. Conversely, Zhou et al. [

121] introduced HAA, a hierarchical adversarial attack strategy for GNN-based IoT detectors, which reduces the classification accuracy by over 30% through minor perturbations and node prioritization techniques.

6.4. Malware Detection in Cloud Platform

Malware detection in cloud platforms is becoming increasingly vital as organizations move data and services to the cloud. Unlike traditional systems, cloud environments pose unique challenges due to their distributed architecture, multi-tenancy, and scalability. The dynamic and large-scale nature of the cloud enables rapid malware propagation, outpacing traditional detection methods. Detection agents on cloud servers provide security services, allowing users to upload files and receive malware reports.

Xiao et al. [

123] proposed a cloud-based malware detection scheme utilizing Q-learning to optimize the offloading rate for mobile devices without prior knowledge of trace generation or radio bandwidth. They employed the Dyna architecture and post-decision state learning to enhance performance and expedite the reinforcement learning process. Testing revealed that their scheme improved detection accuracy by 40%, reduced delay by 15%, and increased mobile device utility by 47% with 100 devices, thereby enhancing overall performance. Additionally, Yadav R. Mahesh [

61] introduced a malware detection system for cloud environments using a novel consolidated Weighted Fuzzy K-means clustering algorithm with an Associative Neural Network (WFCM-AANN). The proposed classifier identified malware with a high detection precision of 92.45%, surpassing existing classifiers.

7. Challenges Associated with Platform-Specific and Cross-Platform

This section discusses platform-specific research challenges related to malware detection, such as Windows, Linux, macOS, Android, iOS, IoT and Cloud. We also present the cross-platform challenges in ML-based malware detection.

Windows platform-

The use of outdated Windows versions, which no longer receive official support, exposes the systems to unpatched vulnerabilities.

The variety of third-party applications on Windows expands the attack surface, thereby increasing the risk of exploitation.

The rise of fileless malware, which primarily lives in memory, presents challenges for traditional detection and mitigation methods.

Inconsistent user behavior and poor adherence to security best practices increases vulnerability.

Linux platform: The primary challenges in Linux malware research include the following.

Linux systems support diverse computer architectures, requiring analysts to create specific malware analysis codes for each architecture, leading to high costs and operational complexity owing to extensive code management.

The analysis environment may lack the necessary loader for the ELF file format, thereby preventing sample execution.

Constructing refined datasets is difficult because of the varied devices, vendors, and architectures of Linux systems.

Moreover, complexity demands expert manual analysis.

macOS platform-

As macOS gains market share, it increasingly targets malware, which requires continuous advancements in detection techniques.

The limited tools available for malware analysis of macOS hinder large-scale studies.

Owing to the historically low prevalence of malware, MacOS users may be less vigilant about security risks.

Android platform-

Android’s dependency on multiple manufacturers slows OS updates, leaving many outdated devices and exposed to security risks.

Third-party Android apps elevate malware risks, thereby threatening device security and user privacy.

Unlike iOS, Android allows users to control permissions, potentially enabling malicious apps to misuse the granted access.

The variety of Android devices and OS versions complicate uniform patching and security protocols.

Android’s open-source framework enables adversaries to examine their code, facilitating reverse engineering and exploitation creation.

iOS platform-

iOS’s auto-erase feature of iOS enhances security but may cause unintended data loss following unsuccessful login attempts.

Despite advanced Face ID, earlier iOS versions were vulnerable to photos or masks, compromising security.

iOS apps use obfuscation to prevent reverse engineering; however, skilled attackers can bypass these defenses to access sensitive data.

In summary, Android’s flexibility through open-source and diverse devices creates scalability but risks security, whereas iOS enhances security with strict policies, thus limiting flexibility. Future research should focus on balancing security, usability, and standardization.

IoT platform: The rapid growth and heterogeneity of IoT devices introduce significant security challenges, especially in combating malware threats.

Most IoT devices use the Android operating system, which is open-sourced and, unlike iOS, is more vulnerable to exposure.

IoT devices possess considerably less computing power than x86-architecture PCs, making them highly vulnerable to malware due to their limited resources.

In machine and deep learning, larger datasets facilitate faster model learning and improvement. However, there is a significant shortage of valid datasets of IoT malware.

Cloud platform: The dynamic and distributed nature of cloud environments poses distinct challenges to the malware landscape.

The interconnected nature of the cloud infrastructure increases the impact of malware.

A shared responsibility model for cloud security can obscure responsible security tasks. This can lead to organizations having limited visibility and control, thus hindering threat detection and response.

Attackers can leverage the automation and scalability features of the cloud to quickly launch large-scale attacks.

Cross-platform issues-

Data heterogeneity: Variations in file formats, system call sequences, and behavioral patterns across platforms make it challenging to create generalized models.

Lack of unified datasets: The absence of a standardized, diverse, and large-scale dataset that incorporates samples from Windows, macOS, Linux, Android, IoT, and cloud environments.

Inconsistent feature representations: Differences in how features like static metadata, dynamic behavior, and memory traces are extracted and represented across platforms.

Transferability of models: ML models trained on one platform (e.g., Windows) may not generalize well to others (e.g., Linux or IoT) because of differences in malware characteristics.

Performance scalability: Ensuring scalability and efficiency of detection techniques when applied to cloud and IoT systems with resource limitations.

These challenges emphasize the need for a multi-platform approach to malware detection that considers platform-specific constraints while addressing overarching cross-platform issues.

8. Limitations in the Existing Literature and Future Research Directions

Based on a comprehensive review, we identified some significant research gaps or limitations and list some significant future works to enhance malware detection using machine learning techniques

Insufficient Model Adaptability to Emerging Malware Variants

Malware continually evolves, with new variants employing polymorphic and metamorphic techniques to evade detection, rendering static or narrowly trained ML models ineffective. Transfer learning and continual learning strategies can be used to train models incrementally using new data from different platforms and emerging malware types. This can help maintain model accuracy without retraining from scratch, thereby addressing the limitations of static ML approaches in dynamic threat landscapes.

High Computational Demands of ML Models in Resource-Constrained Environments

The IoT and mobile devices typically have limited processing power and memory, making it challenging to implement advanced ML-based detection techniques that require substantial computational resources. We need to develop lightweight, energy-efficient ML algorithms that are explicitly optimized for IoT and mobile environments. Techniques such as model pruning, quantization, and distillation can reduce the computational load, enabling robust malware detection, even in devices with limited resources.

Limited Transparency and Interpretability of ML-Driven Detection Systems

The opacity of complex ML models’ intense learning methods hinders their adoption in security-critical applications, where interpretability is essential for understanding detection decisions and incident responses. Incorporate explainable AI (XAI) techniques are used in malware detection models, making it easier for cybersecurity professionals to interpret ML-driven decisions. XAI methods, such as Shapley Additive exPlanations) or Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME), could provide insights into model predictions, enhancing trust and transparency.

Vulnerability to Adversarial Attacks

Adversarial examples, where attackers subtly alter input data to deceive ML models, remain a challenge for malware detection systems, particularly in high-stakes environments, such as IoT and cloud systems. Adversarial training techniques can be integrated to improve model robustness against adversarial samples. Additionally, anomaly detection methods can help identify abnormal patterns that adversarial examples might exhibit, thereby strengthening defense mechanisms.

Limited Research on Hybrid Detection Approaches Combining Static, Dynamic, and Memory Analysis

Most malware detection techniques rely on either static or dynamic analysis, omitting the combined potential of hybrid models that use static, dynamic, and memory features for enhanced detection. To approach this issue, hybrid models can be implemented that integrate static, dynamic, and memory-based analysis techniques, thereby creating a more comprehensive view of malware behaviors across platforms. This approach can improve the detection accuracy and adaptability, especially against complex and evasive malware that may bypass single-method detection.

The proposed solutions offer a roadmap for future research aimed at enhancing the resilience, adaptability, and effectiveness of ML-based malware detection across interconnected digital environments.

9. Conclusion