1. Introduction

The adoption of generative artificial intelligence (genAI) into healthcare is inevitable with evidence pointing to its current wide applications in different healthcare settings (Yim et al., 2024). As genAI advances rapidly in its capabilities, it would fundamentally transform healthcare with subsequent revolution in operational efficiency with improved patient outcomes (Sallam, 2023; Verlingue et al., 2024). Nevertheless, the integration of genAI into healthcare practices is expected to introduce formidable challenges (Dave et al., 2023; Sallam, 2023). Central to these challenges is the expected profound implications on the structure and composition of the workforce in healthcare (Daniyal et al., 2024; Rony et al., 2024b).

On a positive note, the potential of genAI to streamline workflow in healthcare settings is hard to dispute (Fathima & Moulana, 2024; Mese et al., 2023). As stated in a commentary by (Bongurala et al., 2024), AI assistants can decrease documentation time for healthcare professionals (HCPs) by as much as 70% which would enable a greater focus on direct patient care. To be more specific with examples, the improved efficiency provided by genAI can be achieved through automated transcription of patient encounters, data entry into electronic health records (EHRs), and improved patient communication as illustrated by (Small et al., 2024; Tai-Seale et al., 2024).

On the other hand, alongside the aforementioned opportunities, genAI introduces complex challenges in healthcare where even minor errors can lead to grave consequences (Panagioti et al., 2019). An urgent concern of genAI integration into healthcare is the fear of job displacement (Christian et al., 2024; Rony et al., 2024b; Sallam et al., 2024a). As genAI abilities to handles routine and complex tasks in healthcare is realized, the demand for human intervention may diminish, prompting shifts in job roles or even losses (Ramarajan et al., 2024; Rawashdeh, 2023). However, this genAI anticipated impact is not uniform and it could vary across healthcare specialties and cultural contexts. This variability demands careful study to identify determinants of attitude to genAI and devise strategies that maximize genAI benefits in healthcare while addressing critical concerns, including job security.

Research studies have already started to examine how health science students and HCPs perceive the genAI tools such as ChatGPT mostly in the context of Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Abdaljaleel et al., 2024; S. Y. Chen et al., 2024; Sallam et al., 2023). In the context of concerns of possible job displacement, (Rony et al., 2024b) reported that HCPs in Bangladesh expressed concerns about AI undermining roles traditionally occupied by humans. Their analysis highlighted several concerns such as threats to job security, moral questions regarding AI-driven decisions, impacts on patient-HCP relationships, and ethical challenges in automated care (Rony et al., 2024b). In Jordan, a study among medical students developed and validated the FAME scale to measure Fear, Anxiety, Mistrust, and Ethical concerns associated with genAI (Sallam et al., 2024a). This study revealed a range of concerns among medical students, highlighting notable apprehension regarding the impact of genAI on their future careers as physicians (Sallam et al., 2024a). Notably, mistrust and ethical issues predominated over fear and anxiety, illustrating the complicated emotional and cognitive reactions that are elicited by this inevitable novel technology (Sallam et al., 2024a).

From a broader perspective, Nicholas Caporusso introduced the term “Creative Displacement Anxiety” (CDA) to define a psychological state triggered by the perceived or actual infiltration of genAI on areas that required human creativity (Caporusso, 2023). The CDA reflects a complex range of emotional, cognitive, and behavioral responses to the expanding roles of genAI in areas traditionally dependent on human creativity (Caporusso, 2023). Caporusso argued that a thorough understanding genAI and its adoption could alleviate its negative psychological impacts, advocating for proactive engagement with this transformative technology (Caporusso, 2023).

Extending on the previous research on genAI apprehension in the context of healthcare, our study broadens the FAME scale’s validation to a diverse, multinational sample of health sciences students in order to offer a more comprehensive understanding of attitude to genAI in healthcare. Key to our inquiry was the delineation of “Apprehension” as a distinct state of reflective unease that differs fundamentally from the immediate, visceral responses associated with fear or anxiety based on (Grillon, 2008). Herein, Apprehension was defined as a measure to reflect the awareness and cautious consideration of genAI’s future implications rather than acute, present-focused threats.

Thus, our study objectives involved the assessment of student apprehension toward genAI integration in healthcare settings, with confirmatory validation of the FAME scale to ensure its reliability in measuring anxiety, fear, mistrust, and ethical concerns. Specifically, our study addressed the following major questions: First, what is the degree of apprehension toward genAI among health sciences students across various disciplines, including medicine, dentistry, pharmacy, nursing, rehabilitation, and medical laboratory sciences? Second, does the FAME scale effectively capture and measure the specific determinants underlying this apprehension? Finally, which demographic variables and FAME constructs are significantly associated with apprehension toward genAI among health students in Arab countries?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Settings and Participants

This study utilized a cross-sectional survey design targeting health sciences students, spanning fields of medicine, dentistry, pharmacy/doctor of pharmacy, nursing, rehabilitation, and medical laboratory sciences. The study group comprised students of Arab nationality enrolled in universities across the Arab region, as outlined in the survey’s introductory section.

Recruitment of the potential participants was based on snowball sampling convenient approach as outlined by (Leighton et al., 2021). This approach depended on widely-used social media and messaging platforms, including Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), Instagram, LinkedIn, Messenger, and WhatsApp, starting with the authors’ networks across Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia and encouraging further survey dissemination. Data collection started on October 27 and ended on November 5, 2024.

Adhering to the Declaration of Helsinki, the ethical approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the Deanship of Scientific Research at Al-Ahliyya Amman University, Jordan. Participation was voluntary without monetary incentives, and all respondents provided electronic informed consent following an introduction of the survey that detailed study aims, procedures, and confidentiality issues.

Hosted on SurveyMonkey (SurveyMonkey Inc., San Mateo, California, USA) in both Arabic and English, the survey access was limited to a single response per IP address to ensure data reliability. All items required mandatory responses for study inclusion, with rigorous quality checks to ensure data integrity. A minimum response time of 120 seconds was set, guided by a median pre-filtration response time of 222.5 seconds and a 5th percentile benchmark of 111.85 seconds. Additionally, responses were screened for contradictions: participants who selected “none” for genAI model use but indicated the use of specific genAI models were excluded for inconsistency.

Our study design adhered to Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) guidelines which suggest a minimum of 200 participants for sufficient statistical power (Mundfrom et al., 2005). Considering the multinational scope, we targeted over 500 participants to robustly estimate apprehension to genAI across diverse populations.

2.2. Details of the Survey Instrument

Following informed consent, the survey began with demographic data collection including the following variables: age, sex, faculty, nationality, university location, institution type (public vs. private), and the latest grade point average (GPA). The second section inquired about the prior use of genAI, frequency of use, and the self-rated competency in using genAI tools.

The primary outcome measure in the study was “Apprehension toward genAI” entailing assessment of the anticipatory unease about genAI’s future impact on healthcare. Apprehension was assessed through three items adapted and modified from the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) (Spielberger et al., 1971; Spielberger & Reheiser, 2004). These items were: (1) I feel tense when thinking about the impact of generative AI like ChatGPT on my future in healthcare; (2) The idea of generative AI taking over aspects of patient care makes me nervous; and (3) I feel uneasy when I hear about new advances in generative AI for healthcare. The three items were assessed on a 5-point Likert scale from "agree," "somewhat agree," "neutral," "somewhat disagree," to "disagree." Finally, the validated 12-item FAME scale was administered (Sallam et al., 2024a), measuring Fear, Anxiety, Mistrust, and Ethics, with each construct represented by three items rated on a 5-point Likert scale from "agree" to "disagree." The full questionnaire is provided in (

Supplementary S1).

2.3. Statistical and Data Analysis

In the statistical and data analyses, IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp and JASP software (Version 0.19.0) were used (Jasp Team, 2024). Each construct score—Apprehension, Fear, Anxiety, Mistrust, and Ethics—was calculated by summing responses to the corresponding three items, where "agree" was assigned a score of 5, and "disagree" a score of 1, yielding higher scores for stronger agreement with each construct.

Data normality for these 5 scale variables was assessed via the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, justifying subsequent use of the non-parametric tests ((Mann Whitney U test (M-W) and Kruskal Wallis test (K-W)) for univariate associations based on non-normality of the five scales (P<.001 for all). Spearman’s rank-order correlation was used to assess the correlation between two scale variables by measuring the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (ρ).

In examining predictors of apprehension toward genAI, univariate analyses identified candidate variables for inclusion in multivariate analysis based on the P value threshold of .100. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was employed to confirm the linear regression model validity with multicollinearity diagnostics using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) to flag any potential multicollinearity issues, with VIF threshold of >5 (Kim, 2019). Statistical significance for all analyses was set at P<.050.

To validate the structure of the FAME scale, EFA was conducted with maximum likelihood estimation and Oblimin rotation and sampling adequacy checked through the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure, while the factorability was confirmed by Bartlett’s test of sphericity. Subsequent CFA was performed to confirm the FAME scale latent factor structure. Fit indices, including the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) were employed to evaluate model fit. Internal consistency across survey constructs was evaluated using Cronbach’s α, with a threshold of α ≥ 0.60 considered acceptable for reliability (Taber, 2018; Tavakol & Dennick, 2011).

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Study Sample Following Quality Checks

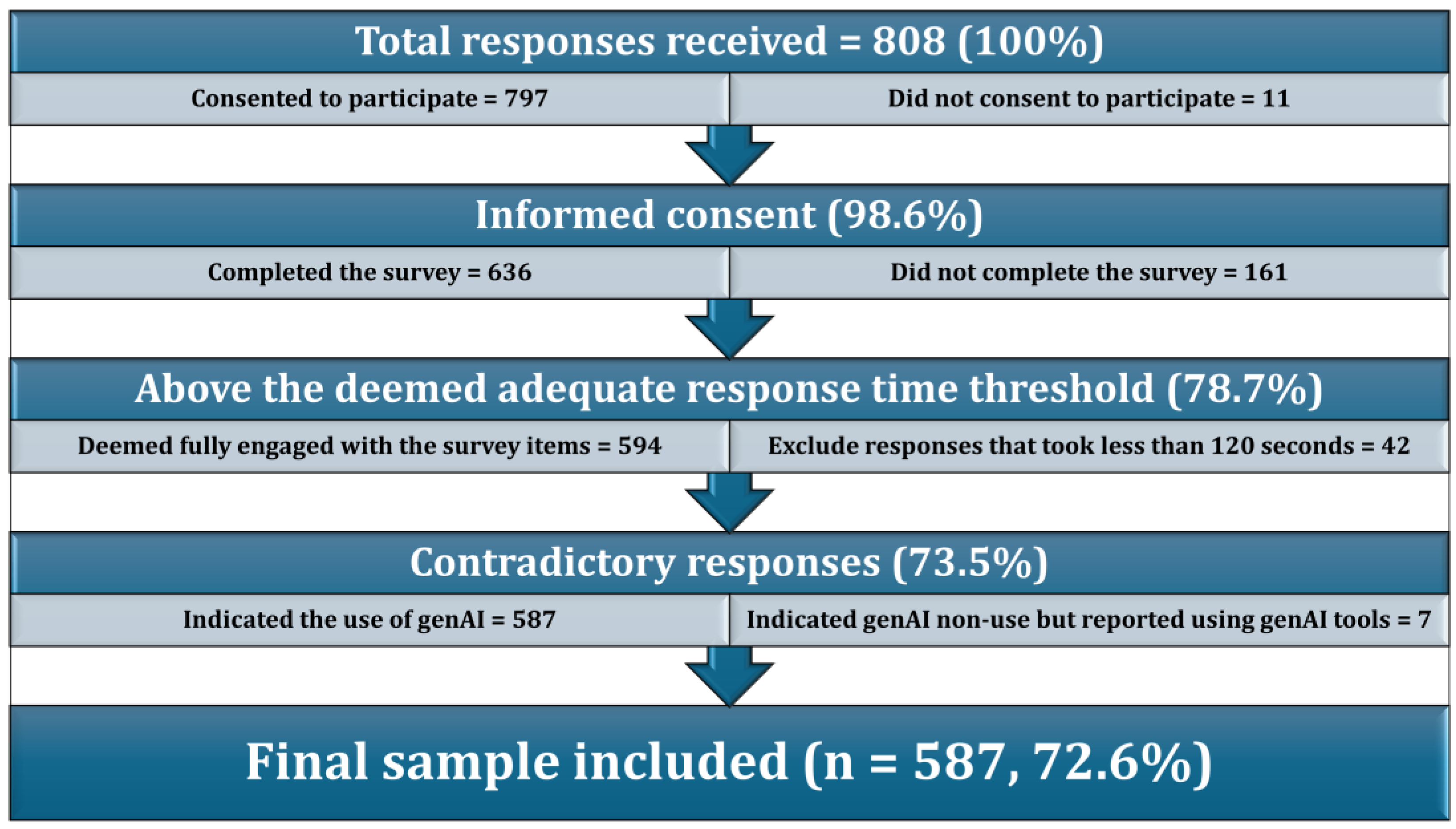

As indicated in (

Figure 1), the final study sample comprised 587 students representing 72.6% of the participants who consented to participate and met the quality check criteria.

As indicated in (

Figure 1), the final study sample comprised 587 students representing 72.6% of the participants who consented to participate and met the quality check criteria.

The final sample primarily consisted of students under 25 years (92.7%) and females (72.9%). Medicine (35.8%) and Pharmacy/PharmD (34.2%) were the most represented faculties. The most common nationality was Jordanian (31.3%), and a slight majority of participants were studying in Jordan (51.3%), with most attending public universities (59.1%). A significant portion indicated high academic performance, with 67.1% reporting either excellent or very good latest GPAs. Generative AI use was widespread, with 80.4% indicating previous use of ChatGPT, although other genAI tools were used less frequently. Regular genAI engagement was common, and 55.9% of participants reported being either competent or very competent (

Table 1).

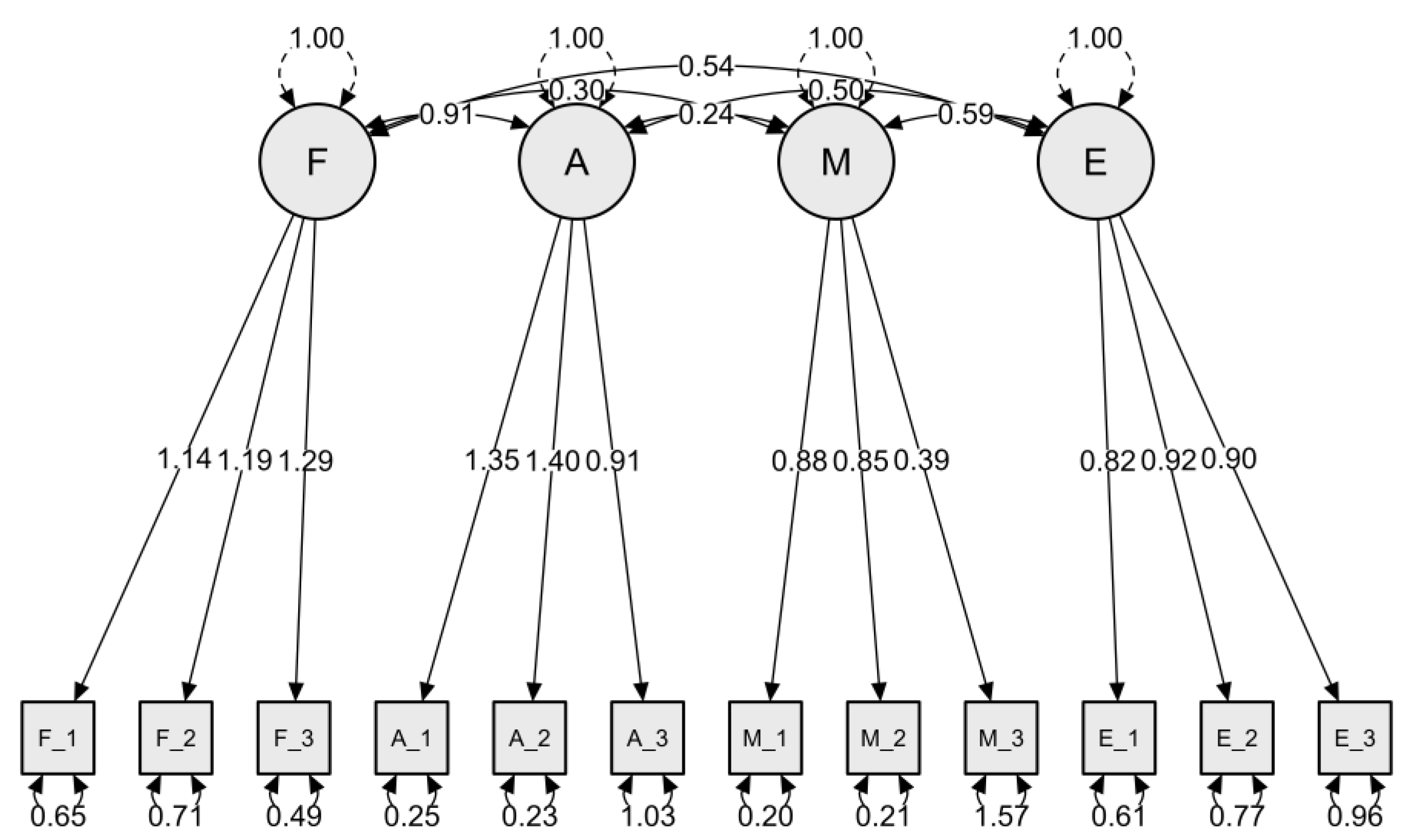

3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the FAME Scale

The CFA for the FAME scale showed a good model fit across several fit indices. The chi-square difference test revealed a statistically significant model fit improvement for the hypothesized factor structure (χ2(48)=194.455, p<.001) compared to the baseline model (χ2(66)=4315.983), which suggested that the four-factor model captured the structure of the data. The CFI was 0.966 and the TLI was 0.953, both of which indicated a good model fit while the RMSEA was 0.072 indicating an acceptable model fit.

Bartlett’s test of sphericity (χ

2(66) = 4273.092,

p<.001) and the KMO measure of sampling adequacy (0.872 overall) indicated that the data were appropriate for factor analysis (

Table 2).

Figure 2 presents the CFA model for the FAME scale, evaluating constructs related to Fear, Anxiety, Mistrust, and Ethics as factors influencing health science students’ perceptions of genAI in healthcare.

Each factor demonstrated strong factor loadings for its respective indicators, suggesting adequate construct validity within the model. Factor loadings ranged from 0.65 to 1.40 across items, indicating robust relationships between observed variables and their underlying latent constructs.

The inter-factor correlations revealed significant relationships between Fear and Anxiety (0.30), Fear and Mistrust (0.24), Anxiety and Mistrust (0.50), and Anxiety and Ethics (0.54), while Mistrust and Ethics showed a correlation of 0.59. The results highlighted the structural validity of the FAME scale, suggesting that Fear, Anxiety, Mistrust, and Ethics can be reliably measured as distinct yet related factors in understanding health students’ attitude toward genAI role in healthcare.

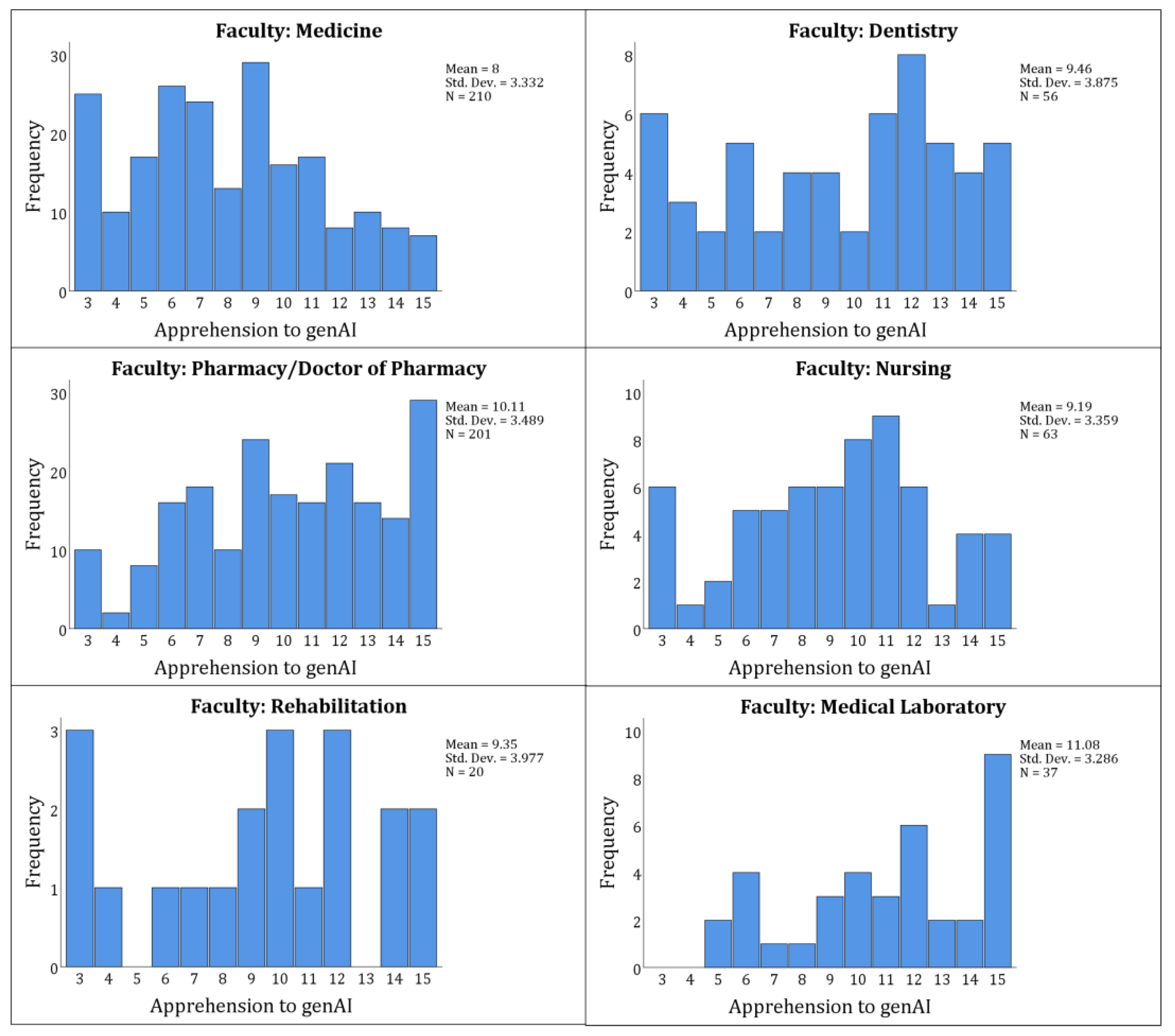

3.3. Apprehension to genAI in the Study Sample

Apprehension toward genAI, as measured by a 3-item scale that showed an acceptable internal consistency with a Cronbach’s α of 0.850, yielded a mean score of 9.23±3.60, indicating a neutral attitude with a tendency toward agreement.

Significant variations in apprehension were observed across several study variables. Faculty showed the highest apprehension in Medical Laboratory (11.08±3.29) and Pharmacy/Doctor of Pharmacy (10.11±3.49) students, contrasting with lower scores in Medicine (8.00±3.33;

P<.001,

Figure 3).

Kuwaiti students had the lowest apprehension (7.92±3.46; p=.006), with students studying in Kuwait also reporting a lower apprehension (7.21±3.48; p=.004). Public university students exhibited less apprehension (8.61±3.55) than those in private universities (10.13±3.47; p<.001).

Previous ChatGPT users reported lower apprehension (8.94±3.5) than non-users (10.43±3.75;

p<.001), and daily users of genAI had lower apprehension (8.16±3.49) compared to less frequent users (

p<.001). Competency in genAI use was inversely related to apprehension, with “not competent” individuals scoring higher (10.9±3.66) than those self-rated as “very competent” (8.63±3.66;

p=.006,

Table 3).

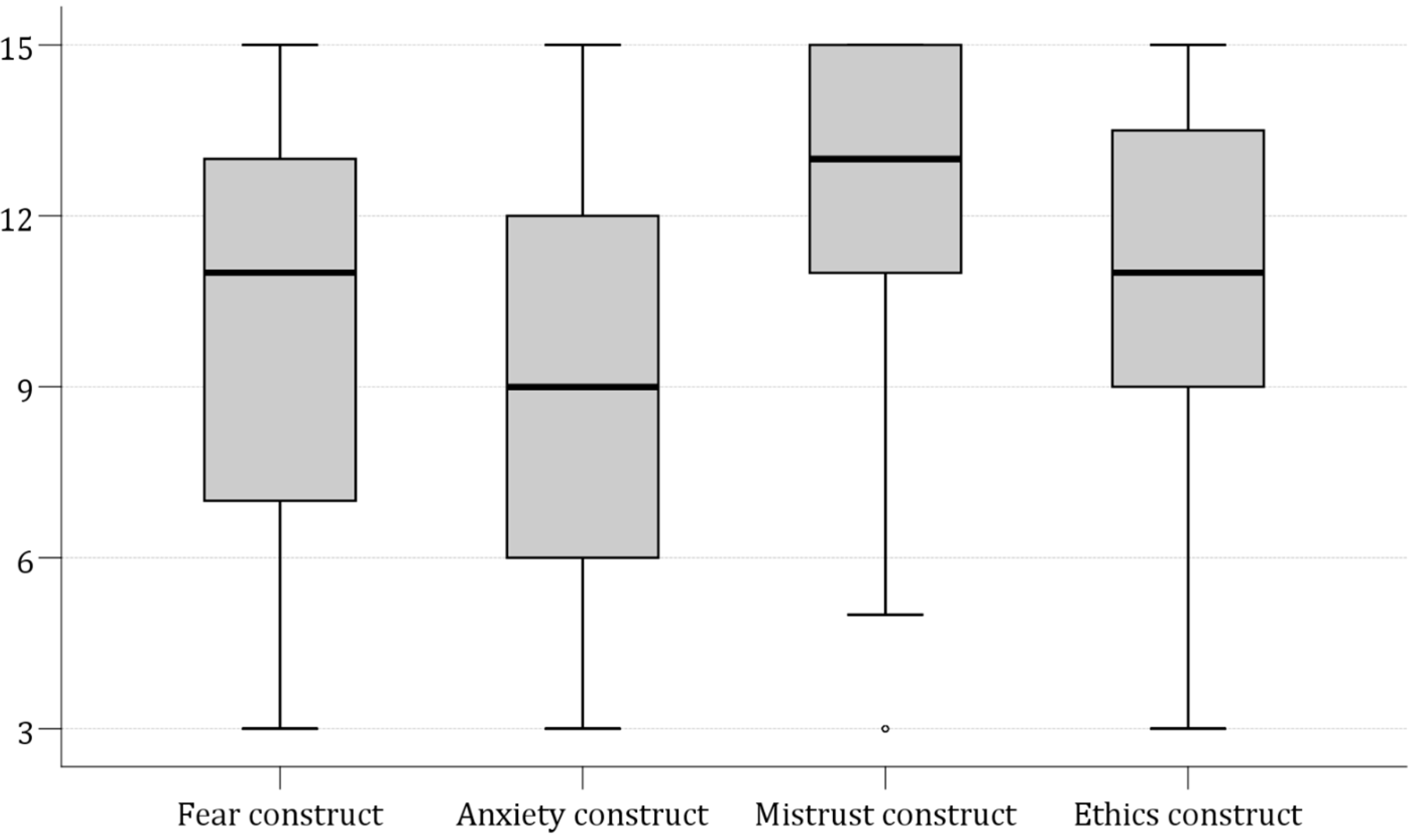

3.4. The FAME Scale Scores in the Study Sample

The mean scores for the FAME constructs indicated varying distribution with Mistrust scoring the highest at 12.46±2.54, followed by Ethics at 11.10±3.06, Fear at 9.96±3.88, and Anxiety at 9.18±3.85 (

Figure 4).

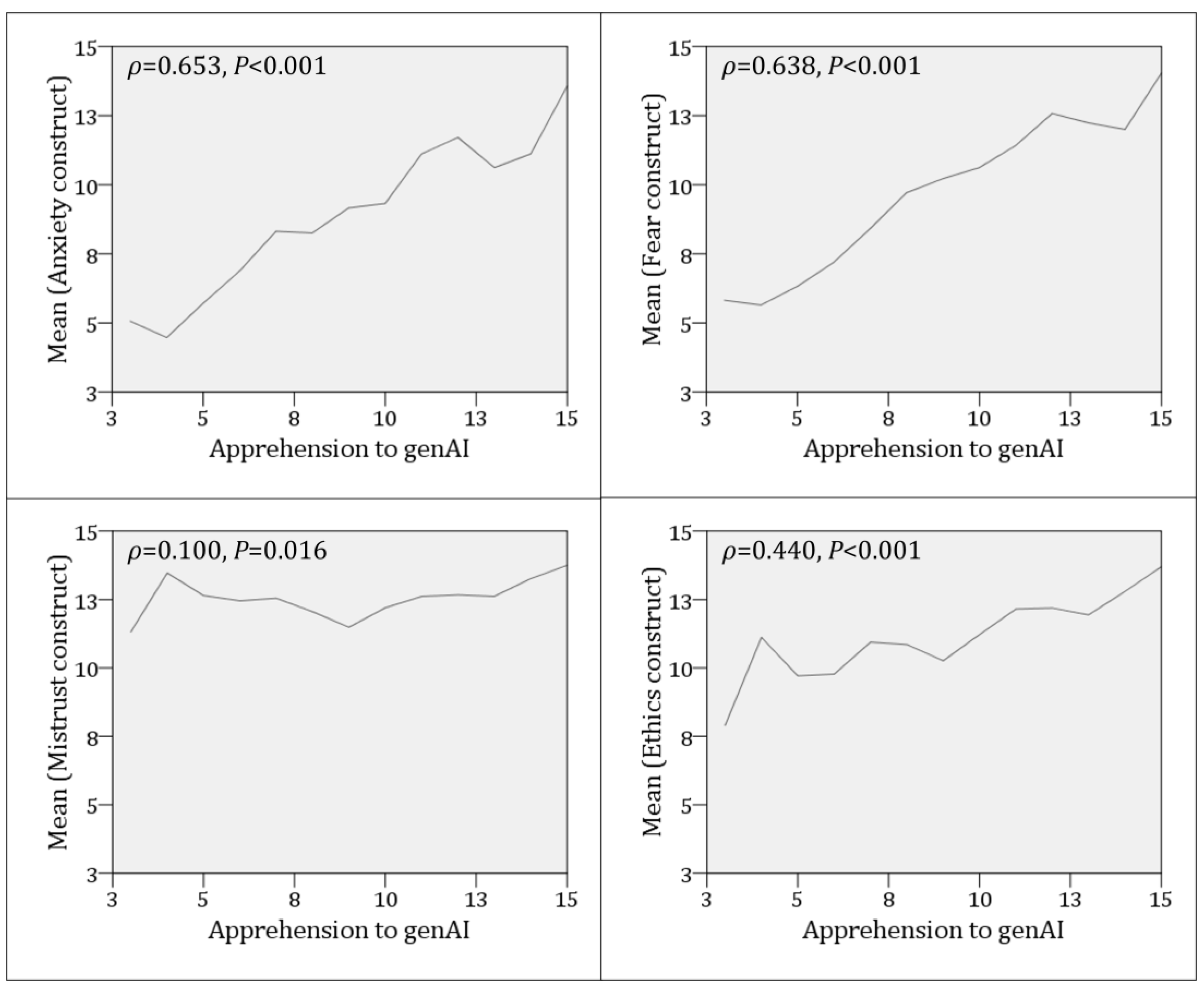

A Spearman’s rank-order correlation was conducted to assess the relationship between apprehension towards genAI and the FEAR four constructs. The analysis revealed a statistically significant positive correlation between the Fear and apprehension constructs,

ρ=0.653,

p<.001; the Anxiety and apprehension constructs,

ρ=0.638,

p<.001; a weak yet statistically significant positive correlation with the Mistrust score,

ρ=0.100;

p=.016, a moderate, statistically significant positive correlation with the Ethics construct,

ρ=0.440, <0.001 (

Figure 5).

3.5. Multivariate Analysis for the Factors Associated with Apprehension to genAI

The regression analysis explained a substantial variance, with R2 of 0.511, indicating that 51.1% of the variance in apprehension toward genAI was accounted for by the included predictors in the model. The regression model demonstrated statistical significance with an F-value of 54.720 and a p<.001 by ANOVA confirming that the whole model was a significant predictor of apprehension toward genAI.

The regression model examining predictors of apprehension toward genAI showed that faculty affiliation (B=0.209, p=.010) and ChatGPT non-use prior to the study (B=−0.635, p=.027) were both significantly associated with apprehension, with faculty having a positive effect and non-ChatGPT use having a negative effect.

Nationality (B=−0.180,

p=.034) and the country where the university is located (B=0.183,

p=.036) also demonstrated significant associations with apprehension levels. Among the psychological constructs, Fear (B=0.302,

p<.001), Anxiety (B=0.251,

p<.001), and Ethics (B=0.212,

p<.001) all showed strong positive associations with apprehension, suggesting that higher agreement with these constructs were linked with greater apprehension toward genAI (

Table 4). In terms of multicollinearity, the VIF values indicated no severe multicollinearity concerns, as all are below 5. However, the Fear (VIF=3.105) and Anxiety constructs (VIF=3.118) were higher relative to other variables, suggesting moderate correlation with other predictors.

4. Discussion

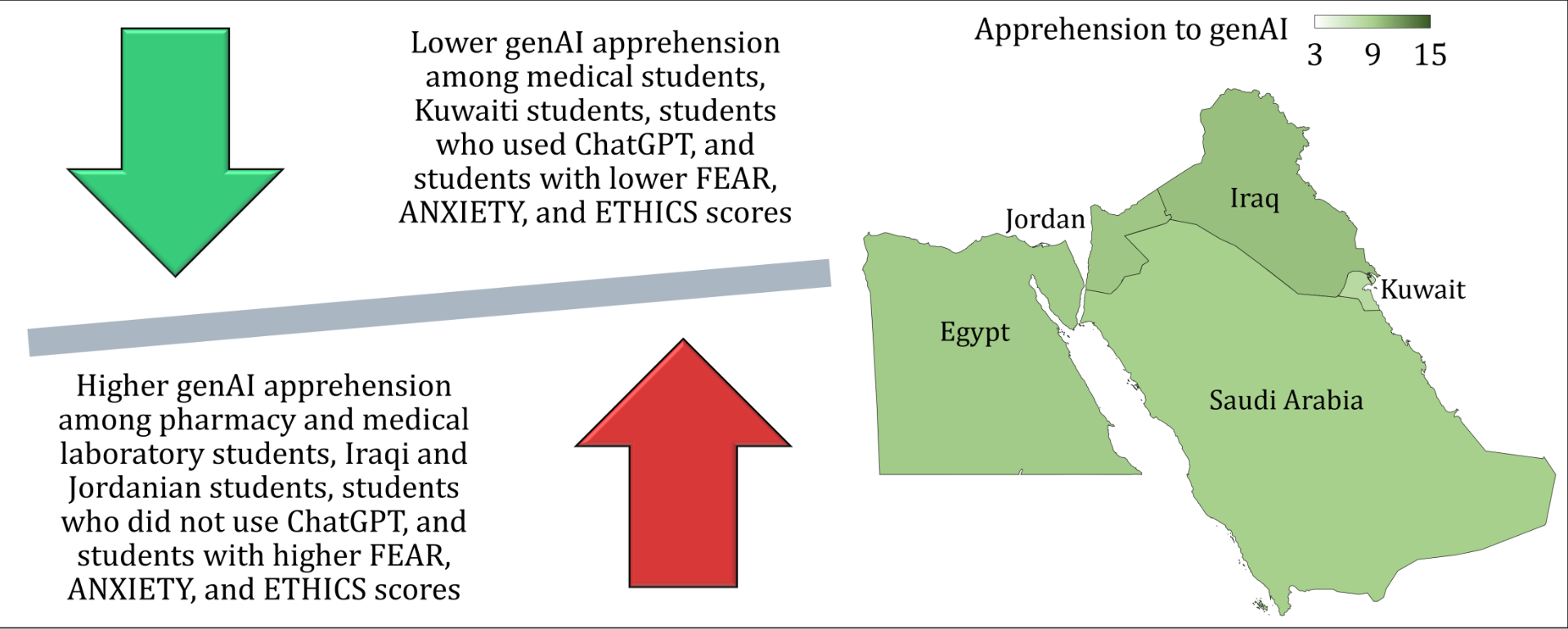

In our study, we investigated the apprehension toward genAI models among health sciences students mainly in five Arab countries. The results pointed to a slight inclination toward apprehension about genAI, albeit the level of apprehension being close to neutral. Nevertheless, the level of genAI apprehension varied with notable disparities found in different demographic and educational contexts (e.g., nationality, faculty). The results suggested that while the participating students were not overwhelmingly apprehensive regarding genAI, they did harbor some apprehension about the implications of genAI in their future careers. This was manifested as a cautious acceptance of genAI rather than outright enthusiasm or rejection for this novel and inevitable technology.

The validity of our results is supported by the following factors. First, the rigorous quality check for responses received included ensuring the receipt of a single response per IP address, checking for contradictory responses, and setting a threshold for acceptable time to complete the survey to avoid common potential caveats in survey studies as listed by (Nur et al., 2024). Second, the robust statistical analyses including EFA and CFA conducted helped to confirm the structural reliability of the FAME scale utilized in our assessment. Third, the diverse study sample primarily involving five different Arab countries provided acceptable credibility and generalizability to the study findings.

In this study, a substantial majority of the participants (87.4%) reported using at least one genAI tool, with a predominant use of ChatGPT by 80.4% of respondents. This result could highlight a trend hinting to the normalization of genAI tools’ use among health sciences students in Arab countries. In turn, this could reflect a broader genAI acceptance and integration into the students’ academic and potential professional careers.

The widespread use of ChatGPT specifically hints to its dominant presence and popularity compared to other genAI tools. As shown by the results of this study, lesser engagement with other genAI tools such as My AI On Snapchat (16.4%), Copilot (12.9%), and Gemini (10.6%) may indicate a disparity in functionality, user experience, or perhaps availability of different genAI tools, which suggests the ChatGPT position as the pioneering genAI tool. The pattern of genAI tool preference aligned with findings from other regional studies, such as that conducted by (Sallam et al., 2024a), which also noted a variability of genAI use among medical students in Jordan, with ChatGPT leading significantly.

The dominant use of genAI tools, particularly ChatGPT, among university students, which was revealed in our study, hints to an emerging norm among university students in Arab countries as also shown in a recent study in the United Arab Emirates (Sallam et al., 2024b). This finding was reported internationally, as evidenced by (Ibrahim et al., 2023) in a large multinational study that was conducted in Brazil, India, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The aforementioned study highlighted a strong tendency among students to employ ChatGPT in university assignments as shown in other studies as well (Ibrahim et al., 2023; Mansour & Wong, 2024; Strzelecki, 2023, 2024). Taken together, the observed rise of genAI models’ use in higher education demands an immediate and thorough examination by educational institutions and educators alike.

Specifically, this scrutiny must assess how genAI models could influence learning outcomes and academic integrity as reported in a recent scoping review by (Xia et al., 2024). Such an evaluation is essential to ensure that the integration of genAI models in higher education does not compromise the foundational principles of educational fairness and integrity, but rather enhances them, maintaining a balance between innovation and traditional academic values (Yusuf et al., 2024).

The major finding of our study was the demonstration of a mean apprehension score of 9.23 regarding genAI among health sciences students in Arab countries. This result suggests a level of readiness among those future HCPs to engage with genAI tools, albeit with an underlying caution. Particularly pronounced was the Mistrust expressed in the FAME scale, where the Mistrust construct achieved the highest mean of 12.46 of the four constructs. This high score denoted an agreement among the participating students on the view of genAI inability to replicate essential human attributes required in healthcare such as empathy and personal insight. Such skepticism likely derives from concerns that genAI, for all its analytical capabilities, cannot fulfill the demands of empathetic patient care, which remains a cornerstone of high-quality healthcare and patients’ satisfaction as shown by (Moya-Salazar et al., 2023). Nevertheless, this view has already been refuted in several studies that showed the empathetic capabilities of genAI at least to an acceptable extent (Ayers et al., 2023; D. Chen et al., 2024; Hindelang et al., 2024).

Additionally, ethical concerns among the participating students in this study were notable. This was illustrated by a mean score for the Ethics construct of 11.10, highlighting the anticipated ethical ramifications of genAI deployment in healthcare which were extensively investigated in recent literature (Haltaufderheide & Ranisch, 2024; Ning et al., 2024; Oniani et al., 2023; Sallam, 2023; Wang et al., 2023). In this study, the students voiced substantial concerns over potential ethical breaches, including fears of compromised patient privacy and exacerbated healthcare inequities which are among the most feared and anticipated concerns of genAI use in healthcare (Khan et al., 2023). Thus, there is a necessity for robust ethical guidelines and regulatory frameworks to ensure that genAI applications are deployed responsibly, safeguarding both equity and confidentiality in patient care (Ning et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2023).

In this study, the Fear construct showed a mean score of 9.96. This result could signal a cautiously neutral yet discernibly fearful stance among health science students about the implications of genAI for job security and the relevance of human roles in the future healthcare. Such fear likely stems from concerns that genAI efficiency and accuracy could overshadow the human roles in healthcare. Subsequently, this can lead to job redundancies and a transformative shift in the professional healthcare settings. This result was in line with fears expressed in a recent studies among HCPs in Bangladesh (Rony et al., 2024a; Rony et al., 2024b). Additionally, the Anxiety construct, with a score of 9.18, may suggest that the traditional healthcare curricula may not be fully preparing health science students for an AI-driven healthcare settings in the near future (Gantwerker et al., 2020). This suggests an urgent need to bridge the gap between current educational programs and the futuristic demands of a technology-driven healthcare sector as reviewed by (Charow et al., 2021).

In regression analysis, the primary determinants of apprehension to genAI in this study included academic faculty, nationality, and the country in which the university is located. Additionally, statistically significant factors correlated with apprehension to genAI included the previous ChatGPT use and three out of the four constructs from the FAME scale namely Fear, Anxiety, and Ethics.

Specifically, the regression coefficients indicated distinct apprehension among pharmacy/doctor of pharmacy and medical laboratory students. This result could be seen as a rational response to the feared devaluation of the specialized skills and traditional roles of pharmacists and medical technologists by genAI (Chalasani et al., 2023). Additionally, the heightened apprehension toward genAI among pharmacy and medical laboratory students, relative to their peers in other health disciplines, can be attributed to the specific vulnerabilities of their fields to AI integration (Antonios et al., 2021; Hou et al., 2024). Pharmacy students may perceive a direct threat to their roles in medication management and patient counseling, as genAI promises to streamline treatment personalization, potentially diminishing the pharmacist involvement in direct patient care (Roosan et al., 2024).

Similarly, medical laboratory students face the prospect of AI automating complex diagnostic processes, potentially reducing their participation in critical decision-making and analytical reasoning (Dadzie Ephraim et al., 2024). On the other hand, medical students in this study showed a relatively lower apprehension toward genAI. This may stem from the perception that their roles involve a broader range of responsibilities and skills that are harder to automate and the many options of specialization they have. The practice of medicine involves complex decision-making, direct patient interactions, and nuanced clinical judgment, areas where AI is seen as a support tool rather than a replacement (Bragazzi & Garbarino, 2024). Nursing and dental students, like their medical counterparts in this study, exhibited relatively lower apprehension toward genAI likely due to the hands-on and interpersonal nature of their disciplines, which are perceived as less susceptible to automation.

An interesting result of the study was the variability in apprehension toward genAI among health sciences students from different Arab countries. Specifically, heightened apprehensions to genAI were found among student from Iraq, Jordan, and Egypt, contrasted with the significantly lower apprehension in Kuwait. This result can be explained through several socio-economic, educational, and cultural perspectives. Such an observation could potentially reflect a broader socio-economic uncertainties and disparities in technological integration within healthcare systems in Iraq, Jordan, and Egypt. These countries, while rich in educational history, face economic challenges that could affect the employment rates and resulting in healthcare resource constraints (Katoue et al., 2022; Lai et al., 2016). In such conditions, the introduction of genAI might be viewed more as a competitive threat than a supportive tool, exacerbating fears of job displacement amidst already competitive job markets.

The higher apprehension observed in these countries is likely compounded by concerns over the ethical use of AI in settings where regulatory frameworks might be perceived as underdeveloped or inadequately enforced. Conversely, Kuwaiti students’ lower levels of apprehension can be attributed to several factors. Economically more stable and with substantial investments in healthcare and education, Kuwait among other Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries offers a more optimistic outlook on technological advancements (Shamsuddinova et al., 2024). Subsequently, the integration of genAI into healthcare would be seen as an enhancement to professional capabilities rather than a threat.

Finally, the pronounced apprehension toward genAI among students exhibiting higher scores in the Fear, Anxiety, and Ethics constructs of the FAME scale, as well as among those who had not previously used ChatGPT should be dissected through a psychological perspective. Students scoring higher in Fear and Anxiety constructs likely perceive genAI not merely as a technological tool, but as a profound disruption. Fear often stems from the perceived threat of job displacement which is a sentiment deeply in-built in the collective psyche of individuals entering competitive fields like healthcare (Kurniasari et al., 2020; Reichert et al., 2015; Zirar et al., 2023).

Anxiety, closely tied to fear as reveled in factor analysis, might be amplified by the uncertainty of coping with rapidly evolving genAI technologies that could alter the whole healthcare future settings (Zirar et al., 2023). On the other hand, the higher scores in Ethics construct in association with higher genAI apprehension suggested the role of ethical implications of integrating genAI in healthcare. Based on the items included in the Ethics construct, the students were likely worried about patient privacy, the integrity of data handling by genAI, and the equitable distribution of AI-enhanced healthcare services which are plausible issue as discussed extensively in recent literature (Bala et al., 2024; Ning et al., 2024; Oniani et al., 2023; Williamson & Prybutok, 2024). The heightened apprehension among students who had not previously used ChatGPT before the study can be attributed to a lack of familiarity and understanding of genAI capabilities and limitations.

The study findings highlight the need for a systematic revision of the current healthcare curricula to address apprehensions about genAI and prepare future HCPs for careers soon to be heavily influenced by AI technologies (Tursunbayeva & Renkema, 2023). To address genAI apprehension and enhance proficiency, curricular developments should include AI literacy courses to explore AI functionalities and ethical dimensions, tailored to each healthcare discipline given the current lack of such curricular as revealed by (Busch et al., 2024).

Ethics modules in healthcare education, specifically dealing with AI, should dissect real-world scenarios and ethical dilemmas (Naik et al., 2022). Additionally, the curriculum can encourage research and critical analysis projects that assess genAI impact on healthcare outcomes and patient satisfaction. Workshops aimed at hands-on training in genAI tools can help diminish fear of redundancy by illustrating how genAI augments rather than replaces human expertise (Giannakos et al., 2024). These initiatives can collectively culminate in successful incorporation of AI into educational frameworks, fostering a generation of HCPs who are both technically confident and ethically prepared.

The current study methodological rigor and multinational scope provided a strong foundation for its findings; nevertheless, despite its strengths, our study was not without limitations. First, the use of a cross-sectional survey design precluded the ability to establish causal relationships between the study variables, and longitudinal future studies are recommended to assess the trends of changing attitude to genAI and causality. Second, recruitment of the potential participants was based on a convenience and snowball sampling approach, which could have introduced bias by over-representing certain groups within the network of the initial participants and under-representing others outside of these networks. Finally, the study relied on self-reported data (e.g., latest GPA, genAI use, etc.), which can be subject to response biases such as social desirability or recall biases.

5. Conclusions

In this multinational survey, Arab health sciences students exhibited a predominantly neutral yet cautiously optimistic attitude towards genAI, as evidenced by a mean apprehension score that leaned slightly towards agreement. This perception varied notably by discipline and nationality as pharmacy and medical laboratory students expressed the highest apprehension, likely due to the perceived potential disruption of genAI in their specialized fields. On the other hand, Kuwaiti students showed the lowest genAI apprehension, potentially reflecting national policies favoring technological adoption and integration into educational systems or underlying job security. Significant associations were found between apprehension and three constructs of the FAME scale—fear, anxiety, and ethics—highlighting deep-seated concerns that call for targeted educational strategies to address genAI apprehension. As genAI tools advance, it is crucial for healthcare education to evolve accordingly, ensuring that future HCPs are not only technologically proficient but also well-prepared to address ethical issues introduced by genAI. Integrating genAI into healthcare curricula must be done strategically and ethically, to prepare the students to effectively manage both the technological and ethical challenges posed by AI, thereby enhancing their readiness to address fears of job displacement and ethical dilemmas.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org, Supplementary File S1: The full questionnaire used in the study as retrieved from SurveyMonkey.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Malik Sallam; Data curation: Malik Sallam, Kholoud Al-Mahzoum, Haya Alaraji, Noor Albayati, Shahad Alenzei, Fai AlFarhan, Aisha Alkandari, Sarah Alkhaldi, Noor Alhaider, Dimah Al-Zubaidi, Fatma Shammari, Mohammad Salahaldeen, Aya Saleh Slehat, Maad M. Mijwil, Doaa H. Abdelaziz, Ahmad Samed Al-Adwan; Formal analysis: Malik Sallam; Investigation: Malik Sallam, Kholoud Al-Mahzoum, Haya Alaraji, Noor Albayati, Shahad Alenzei, Fai AlFarhan, Aisha Alkandari, Sarah Alkhaldi, Noor Alhaider, Dimah Al-Zubaidi, Fatma Shammari, Mohammad Salahaldeen, Aya Saleh Slehat, Maad M. Mijwil, Doaa H. Abdelaziz, Ahmad Samed Al-Adwan; Methodology: Malik Sallam, Kholoud Al-Mahzoum, Haya Alaraji, Noor Albayati, Shahad Alenzei, Fai AlFarhan, Aisha Alkandari, Sarah Alkhaldi, Noor Alhaider, Dimah Al-Zubaidi, Fatma Shammari, Mohammad Salahaldeen, Aya Saleh Slehat, Maad M. Mijwil, Doaa H. Abdelaziz, Ahmad Samed Al-Adwan; Project administration: Malik Sallam; Resources: Malik Sallam; Software: Malik Sallam; Supervision: Malik Sallam, Ahmad Samed Al-Adwan; Validation: Malik Sallam, Ahmad Samed Al-Adwan; Visualization: Malik Sallam; Writing – original draft: Malik Sallam; Writing – review and editing: Malik Sallam, Kholoud Al-Mahzoum, Haya Alaraji, Noor Albayati, Shahad Alenzei, Fai AlFarhan, Aisha Alkandari, Sarah Alkhaldi, Noor Alhaider, Dimah Al-Zubaidi, Fatma Shammari, Mohammad Salahaldeen, Aya Saleh Slehat, Maad M. Mijwil, Doaa H. Abdelaziz, Ahmad Samed Al-Adwan. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and it was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Deanship of Scientific Research at Al-Ahliyya Amman University, Jordan. The study included an electronic informed consent per the recommendation of IRB approval, ensuring that all participants understand the study objectives, procedures, and confidentiality measures.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the public data tool Open Science Framework (OSF), using the following link:

https://osf.io/ph32d/

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| AI |

Artificial intelligence |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of Variance |

| CDA |

Creative Displacement Anxiety |

| CFA |

Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| EFA |

Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| EHRs |

Electronic health records |

| FAME |

Fear, Anxiety, Mistrust, and Ethics |

| GCC |

Gulf Cooperation Council |

| genAI |

Generative artificial intelligence |

| GFI |

Goodness of Fit Index |

| GPA |

Grade point average |

| HCPs |

Healthcare professionals |

| HSSs |

Health sciences students |

| KMO |

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin |

| K-W |

Kruskal Wallis test |

| M-W |

Mann Whitney U test |

| RMSEA |

Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| SD |

Standard deviation |

| SRMR |

Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

| STAI |

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory |

| TAM |

Technology Acceptance Model |

| TLI |

Tucker-Lewis Index |

| VIF |

Variance Inflation Factor |

References

- Abdaljaleel, M.; Barakat, M.; Alsanafi, M.; Salim, N.A.; Abazid, H.; Malaeb, D.; Mohammed, A.H.; Hassan, B.A.R.; Wayyes, A.M.; Farhan, S.S.; Khatib, S.E.; Rahal, M.; Sahban, A.; Abdelaziz, D.H.; Mansour, N.O.; AlZayer, R.; Khalil, R.; Fekih-Romdhane, F.; Hallit, R.; …Sallam, M. A multinational study on the factors influencing university students’ attitudes and usage of ChatGPT. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonios, K.; Croxatto, A.; Culbreath, K. Current State of Laboratory Automation in Clinical Microbiology Laboratory. Clin Chem 2021, 68, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers, J.W.; Poliak, A.; Dredze, M.; Leas, E.C.; Zhu, Z.; Kelley, J.B.; Faix, D.J.; Goodman, A.M.; Longhurst, C.A.; Hogarth, M.; Smith, D.M. Comparing Physician and Artificial Intelligence Chatbot Responses to Patient Questions Posted to a Public Social Media Forum. JAMA Intern Med 2023, 183, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, I.; Pindoo, I.; Mijwil, M.; Abotaleb, M.; Yundong, W. Ensuring Security and Privacy in Healthcare Systems: A Review Exploring Challenges, Solutions, Future Trends, and the Practical Applications of Artificial Intelligence. Jordan Medical Journal 2024, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongurala, A.R.; Save, D.; Virmani, A.; Kashyap, R. Transforming Health Care With Artificial Intelligence: Redefining Medical Documentation. Mayo Clinic Proceedings: Digital Health 2024, 2, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragazzi, N.L.; Garbarino, S. Toward Clinical Generative AI: Conceptual Framework. Jmir ai 2024, 3, e55957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busch, F.; Hoffmann, L.; Truhn, D.; Ortiz-Prado, E.; Makowski, M.R.; Bressem, K.K.; Adams, L.C.; Abdala, N.; Navarro, Á.A.; Aerts, H.J.W.L.; Águas, C.; Aineseder, M.; Alomar, M.; Angkurawaranon, S.; Angus, Z.G.; Asouchidou, E.; Bakhshi, S.; Bamidis, P.D.; Barbosa, P.N.V.P.; …Consortium, C. Global cross-sectional student survey on AI in medical, dental, and veterinary education and practice at 192 faculties. BMC Medical Education 2024, 24, 1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporusso, N. Generative Artificial Intelligence and the Emergence of Creative Displacement Anxiety: Review. Research Directs in Psychology and Behavior 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalasani, S.H.; Syed, J.; Ramesh, M.; Patil, V.; Pramod Kumar, T.M. Artificial intelligence in the field of pharmacy practice: A literature review. Explor Res Clin Soc Pharm 2023, 12, 100346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charow, R.; Jeyakumar, T.; Younus, S.; Dolatabadi, E.; Salhia, M.; Al-Mouaswas, D.; Anderson, M.; Balakumar, S.; Clare, M.; Dhalla, A.; Gillan, C.; Haghzare, S.; Jackson, E.; Lalani, N.; Mattson, J.; Peteanu, W.; Tripp, T.; Waldorf, J.; Williams, S.; …Wiljer, D. Artificial Intelligence Education Programs for Health Care Professionals: Scoping Review. JMIR Med Educ 2021, 7, e31043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Parsa, R.; Hope, A.; Hannon, B.; Mak, E.; Eng, L.; Liu, F.F.; Fallah-Rad, N.; Heesters, A.M.; Raman, S. Physician and Artificial Intelligence Chatbot Responses to Cancer Questions From Social Media. JAMA Oncol 2024, 10, 956–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.Y.; Kuo, H.Y.; Chang, S.H. Perceptions of ChatGPT in healthcare: Usefulness, trust, and risk. Front Public Health 2024, 12, 1457131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christian, M.; Pardede, R.; Gularso, K.; Wibowo, S.; Muzammil, O.M.; Sunarno. (2024, 7-8 Aug. 2024). Evaluating AI-Induced Anxiety and Technical Blindness in Healthcare Professionals. 2024 3rd International Conference on Creative Communication and Innovative Technology (ICCIT).

- Dadzie Ephraim, R.K.; Kotam, G.P.; Duah, E.; Ghartey, F.N.; Mathebula, E.M.; Mashamba-Thompson, T.P. Application of medical artificial intelligence technology in sub-Saharan Africa: Prospects for medical laboratories. Smart Health 2024, 33, 100505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniyal, M.; Qureshi, M.; Marzo, R.R.; Aljuaid, M.; Shahid, D. Exploring clinical specialists’ perspectives on the future role of AI: Evaluating replacement perceptions, benefits, and drawbacks. BMC Health Services Research 2024, 24, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dave, T.; Athaluri, S.A.; Singh, S. ChatGPT in medicine: An overview of its applications, advantages, limitations, future prospects, and ethical considerations. Front Artif Intell 2023, 6, 1169595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fathima, M.; Moulana, M. Revolutionizing Breast Cancer Care: AI-Enhanced Diagnosis and Patient History. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin 2024, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantwerker, E.; Allen, L.M.; Hay, M. Future of Health Professions Education Curricula. In D. Nestel, G. Reedy, L. McKenna, & S. Gough (Eds.), Clinical Education for the Health Professions: Theory and Practice (pp. 1-22). Springer Nature Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Giannakos, M.; Azevedo, R.; Brusilovsky, P.; Cukurova, M.; Dimitriadis, Y.; Hernandez-Leo, D.; Järvelä, S.; Mavrikis, M.; Rienties, B. The promise and challenges of generative AI in education. Behaviour & Information Technology 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillon, C. Models and mechanisms of anxiety: Evidence from startle studies. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008, 199, 421–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haltaufderheide, J.; Ranisch, R. The ethics of ChatGPT in medicine and healthcare: A systematic review on Large Language Models (LLMs). npj Digital Medicine 2024, 7, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindelang, M.; Sitaru, S.; Zink, A. Transforming Health Care Through Chatbots for Medical History-Taking and Future Directions: Comprehensive Systematic Review. JMIR Med Inform 2024, 12, e56628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, H.; Zhang, R.; Li, J. Artificial intelligence in the clinical laboratory. Clinica Chimica Acta 2024, 559, 119724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, H.; Liu, F.; Asim, R.; Battu, B.; Benabderrahmane, S.; Alhafni, B.; Adnan, W.; Alhanai, T.; AlShebli, B.; Baghdadi, R.; Bélanger, J.J.; Beretta, E.; Celik, K.; Chaqfeh, M.; Daqaq, M.F.; Bernoussi, Z.E.; Fougnie, D.; Garcia de Soto, B.; Gandolfi, A.; …Zaki, Y. Perception, performance, and detectability of conversational artificial intelligence across 32 university courses. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 12187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasp Team. JASP (Version 0.19.0) [Computer Software]. 2024. Available online: https://jasp-stats.org/ (accessed on 9 November 2024).

- Katoue, M.G.; Cerda, A.A.; García, L.Y.; Jakovljevic, M. Healthcare system development in the Middle East and North Africa region: Challenges, endeavors and prospective opportunities. Front Public Health 2022, 10, 1045739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, B.; Fatima, H.; Qureshi, A.; Kumar, S.; Hanan, A.; Hussain, J.; Abdullah, S. Drawbacks of Artificial Intelligence and Their Potential Solutions in the Healthcare Sector. Biomed Mater Devices 2023, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H. Multicollinearity and misleading statistical results. Korean J Anesthesiol 2019, 72, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurniasari, L.; Suhariadi, F.; Handoyo, S. Are Young Physicians Have Problem in Job Insecurity? The Impact of Health systems’ Changes. Journal of Educational, Health and Community Psychology 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Ahmad, A.; Wan, C.D. Higher Education in the Middle East and North Africa: Exploring Regional and Country Specific Potentials. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leighton, K.; Kardong-Edgren, S.; Schneidereith, T.; Foisy-Doll, C. Using Social Media and Snowball Sampling as an Alternative Recruitment Strategy for Research. Clinical Simulation In Nursing 2021, 55, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, T.; Wong, J. Enhancing fieldwork readiness in occupational therapy students with generative AI. Front Med (Lausanne) 2024, 11, 1485325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mese, I.; Taslicay, C.A.; Sivrioglu, A.K. Improving radiology workflow using ChatGPT and artificial intelligence. Clin Imaging 2023, 103, 109993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moya-Salazar, J.; Goicochea-Palomino, E.A.; Porras-Guillermo, J.; Cañari, B.; Jaime-Quispe, A.; Zuñiga, N.; Moya-Salazar, M.J.; Contreras-Pulache, H. Assessing empathy in healthcare services: A systematic review of South American healthcare workers’ and patients’ perceptions. Front Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1249620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundfrom, D.J.; Shaw, D.G.; Ke, T.L. Minimum Sample Size Recommendations for Conducting Factor Analyses. International Journal of Testing 2005, 5, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, N.; Hameed, B.M.Z.; Shetty, D.K.; Swain, D.; Shah, M.; Paul, R.; Aggarwal, K.; Ibrahim, S.; Patil, V.; Smriti, K.; Shetty, S.; Rai, B.P.; Chlosta, P.; Somani, B.K. Legal and Ethical Consideration in Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: Who Takes Responsibility? Front Surg 2022, 9, 862322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Y.; Teixayavong, S.; Shang, Y.; Savulescu, J.; Nagaraj, V.; Miao, D.; Mertens, M.; Ting, D.S.W.; Ong, J.C.L.; Liu, M.; Cao, J.; Dunn, M.; Vaughan, R.; Ong, M.E.H.; Sung, J.J.; Topol, E.J.; Liu, N. Generative artificial intelligence and ethical considerations in health care: A scoping review and ethics checklist. Lancet Digit Health 2024, 6, e848–e856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nur, A.A.; Leibbrand, C.; Curran, S.R.; Votruba-Drzal, E.; Gibson-Davis, C. Managing and minimizing online survey questionnaire fraud: Lessons from the Triple C project. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 2024, 27, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oniani, D.; Hilsman, J.; Peng, Y.; Poropatich, R.K.; Pamplin, J.C.; Legault, G.L.; Wang, Y. Adopting and expanding ethical principles for generative artificial intelligence from military to healthcare. npj Digital Medicine 2023, 6, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panagioti, M.; Khan, K.; Keers, R.N.; Abuzour, A.; Phipps, D.; Kontopantelis, E.; Bower, P.; Campbell, S.; Haneef, R.; Avery, A.J.; Ashcroft, D.M. Prevalence, severity, and nature of preventable patient harm across medical care settings: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj 2019, 366, l4185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramarajan, M.; Dinesh, A.; Muthuraman, C.; Rajini, J.; Anand, T.; Segar, B. (2024). AI-Driven Job Displacement and Economic Impacts: Ethics and Strategies for Implementation. In K. L. Tennin, S. Ray, & J. M. Sorg (Eds.), Cases on AI Ethics in Business (pp. 216-238). IGI Global. [CrossRef]

- Rawashdeh, A. The consequences of artificial intelligence: An investigation into the impact of AI on job displacement in accounting. Journal of Science and Technology Policy Management 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, A.R.; Augurzky, B.; Tauchmann, H. Self-perceived job insecurity and the demand for medical rehabilitation: Does fear of unemployment reduce health care utilization? Health Econ 2015, 24, 8–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rony, M.K.K.; Numan, S.M.; Johra, F.T.; Akter, K.; Akter, F.; Debnath, M.; Mondal, S.; Wahiduzzaman, M.; Das, M.; Ullah, M.; Rahman, M.H.; Das Bala, S.; Parvin, M.R. Perceptions and attitudes of nurse practitioners toward artificial intelligence adoption in health care. Health Sci. Rep. 2024, 7, e70006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rony, M.K.K.; Parvin, M.R.; Wahiduzzaman, M.; Debnath, M.; Bala, S.D.; Kayesh, I. "I Wonder if my Years of Training and Expertise Will be Devalued by Machines": Concerns About the Replacement of Medical Professionals by Artificial Intelligence. SAGE Open Nurs 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roosan, D.; Padua, P.; Khan, R.; Khan, H.; Verzosa, C.; Wu, Y. Effectiveness of ChatGPT in clinical pharmacy and the role of artificial intelligence in medication therapy management. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2024, 64, 422–428.e428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M. ChatGPT Utility in Healthcare Education, Research, and Practice: Systematic Review on the Promising Perspectives and Valid Concerns. Healthcare (Basel) 2023, 11, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallam, M.; Al-Mahzoum, K.; Almutairi, Y.M.; Alaqeel, O.; Abu Salami, A.; Almutairi, Z.E.; Alsarraf, A.N.; Barakat, M. Anxiety among Medical Students Regarding Generative Artificial Intelligence Models: A Pilot Descriptive Study. International Medical Education 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M.; Elsayed, W.; Al-Shorbagy, M.; Barakat, M.; El Khatib, S.; Ghach, W.; Alwan, N.; Hallit, S.; Malaeb, D. ChatGPT usage and attitudes are driven by perceptions of usefulness, ease of use, risks, and psycho-social impact: A study among university students in the UAE [Original Research]. Frontiers in Education 2024, 9, 1414758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M.; Salim, N.A.; Barakat, M.; Al-Mahzoum, K.; Al-Tammemi, A.B.; Malaeb, D.; Hallit, R.; Hallit, S. Assessing Health Students’ Attitudes and Usage of ChatGPT in Jordan: Validation Study. JMIR Med Educ 2023, 9, e48254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsuddinova, S.; Heryani, P.; Naval, M.A. Evolution to revolution: Critical exploration of educators’ perceptions of the impact of Artificial Intelligence (AI) on the teaching and learning process in the GCC region. International Journal of Educational Research 2024, 125, 102326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, W.R.; Wiesenfeld, B.; Brandfield-Harvey, B.; Jonassen, Z.; Mandal, S.; Stevens, E.R.; Major, V.J.; Lostraglio, E.; Szerencsy, A.; Jones, S.; Aphinyanaphongs, Y.; Johnson, S.B.; Nov, O.; Mann, D. Large Language Model-Based Responses to Patients’ In-Basket Messages. JAMA Netw Open 2024, 7, e2422399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spielberger, C.D.; Gonzalez-Reigosa, F.; Martinez-Urrutia, A.; Natalicio, L.F.; Natalicio, D.S. The state-trait anxiety inventory. Revista Interamericana de Psicologia/Interamerican journal of psychology 1971, 5, 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger, C.D.; Reheiser, E.C. (2004). Measuring anxiety, anger, depression, and curiosity as emotional states and personality traits with the STAI, STAXI and STPI. In Comprehensive handbook of psychological assessment, Vol. 2: Personality assessment. (pp. 70-86). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Strzelecki, A. To use or not to use ChatGPT in higher education? A study of students’ acceptance and use of technology. Interactive Learning Environments 2023, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strzelecki, A. Students’ Acceptance of ChatGPT in Higher Education: An Extended Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. Innovative Higher Education 2024, 49, 223–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K.S. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Research in Science Education 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai-Seale, M.; Baxter, S.L.; Vaida, F.; Walker, A.; Sitapati, A.M.; Osborne, C.; Diaz, J.; Desai, N.; Webb, S.; Polston, G.; Helsten, T.; Gross, E.; Thackaberry, J.; Mandvi, A.; Lillie, D.; Li, S.; Gin, G.; Achar, S.; Hofflich, H.; …Longhurst, C.A. AI-Generated Draft Replies Integrated Into Health Records and Physicians’ Electronic Communication. JAMA Netw Open 2024, 7, e246565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int J Med Educ 2011, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tursunbayeva, A.; Renkema, M. Artificial intelligence in health-care: Implications for the job design of healthcare professionals. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 2023, 61, 845–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlingue, L.; Boyer, C.; Olgiati, L.; Brutti Mairesse, C.; Morel, D.; Blay, J.Y. Artificial intelligence in oncology: Ensuring safe and effective integration of language models in clinical practice. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2024, 46, 101064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, S.; Yang, H.; Guo, J.; Wu, Y.; Liu, J. Ethical Considerations of Using ChatGPT in Health Care. J Med Internet Res 2023, 25, e48009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, S.M.; Prybutok, V. Balancing Privacy and Progress: A Review of Privacy Challenges, Systemic Oversight, and Patient Perceptions in AI-Driven Healthcare. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Weng, X.; Ouyang, F.; Lin, T.J.; Chiu, T.K.F. A scoping review on how generative artificial intelligence transforms assessment in higher education. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 2024, 21, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, D.; Khuntia, J.; Parameswaran, V.; Meyers, A. Preliminary Evidence of the Use of Generative AI in Health Care Clinical Services: Systematic Narrative Review. JMIR Med Inform 2024, 12, e52073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, A.; Pervin, N.; Román-González, M. Generative AI and the future of higher education: A threat to academic integrity or reformation? Evidence from multicultural perspectives. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 2024, 21, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zirar, A.; Ali, S.I.; Islam, N. Worker and workplace Artificial Intelligence (AI) coexistence: Emerging themes and research agenda. Technovation 2023, 124, 102747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).