Submitted:

03 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Subjects

2.2. Surgical Technique

2.3. ICG Lymphography Examination

2.4. Follow-up and Outcomes

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boccardo, F.M.; Ansaldi, F.; Bellini, C.; Accogli, S.; Taddei, G.; Murdaca, G.; Campisi, C.; Villa, G.; Icardi, G.; Durando, P.; et al. Prospective evaluation of a prevention protocol for lymphedema following surgery for breast cancer. Lymphology 2009, 42, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hahamoff, M.; Gupta, N.; Munoz, D.; Lee, B.T.; Clevenger, P.; Shaw, C.; Spiguel, L.; Singhal, D. A Lymphedema Surveillance Program for Breast Cancer Patients Reveals the Promise of Surgical Prevention. J. Surg. Res. 2018, 244, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciudad, P.; Escandón, J.M.; Bustos, V.P.; Manrique, O.J.; Kaciulyte, J. Primary Prevention of Cancer-Related Lymphedema Using Preventive Lymphatic Surgery: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Indian J. Plast. Surg. 2022, 55, 018–025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Hoskin, T.L.; Habermann, E.B.; Cheville, A.L.; Boughey, J.C. Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema Risk is Related to Multidisciplinary Treatment and Not Surgery Alone: Results from a Large Cohort Study. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 24, 2972–2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDuff, S.G.R.; Mina, A.I.; Brunelle, C.L.; Salama, L.; et al. Timing of Lymphedema After Treatment for Breast Cancer: When Are Patients Most At Risk? Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2019, 103, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.; Janssen, C.F.; Velasquez, F.C.; Zhang, S.; Aldrich, M.B.; Shaitelman, S.F.; DeSnyder, S.M.; Sevick-Muraca, E.M. Radiation Dose-Dependent Changes in Lymphatic Remodeling. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2019, 105, 852–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyawan, I.B.; Kurnia, D.; Setiaji, K.; Anwar, S.L.; Purwanto, D.J.; Azhar, Y.; Budijitno, S.; Suprabawati, D.G.A.; Priyono, S.H.; Siregar, B.A.; et al. Sociodemographic disparities associated with advanced stages and distant metastatic breast cancers at diagnosis in Indonesia: a cross-sectional study. Ann. Med. Surg. 2023, 85, 4211–4217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiSipio, T.; Rye, S.; Newman, B.; Hayes, S. Incidence of unilateral arm lymphoedema after breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14, 500–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Garza, R.M.; Chang, D.W. Lymphatic Microsurgical Preventive Healing Approach (LYMPHA) for the prevention of secondary lymphedema. Breast J. 2019, 26, 721–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.K.; Chang, D.W. Vascularized lymph node transfer and lymphovenous bypass: Novel treatment strategies for symptomatic lymphedema. J. Surg. Oncol. 2016, 113, 932–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayan, J.H.; Ly, C.L.; Kataru, R.P.; Mehrara, B.J. Lymphedema: Pathogenesis and Novel Therapies. Annu Rev Med 2018, 69, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunelle, C.L.; Taghian, A.G. Lymphoedema screening: setting the standard. Br. J. Cancer 2020, 123, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrio, A.V.; Eaton, A.; Frazier, T.G. A Prospective Validation Study of Bioimpedance with Volume Displacement in Early-Stage Breast Cancer Patients at Risk for Lymphedema. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 22, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gursen, C.; Dylke, E.S.; Moloney, N.; Meeus, M.; De Vrieze, T.; Devoogdt, N.; De Groef, A. Self-reported signs and symptoms of secondary upper limb lymphoedema related to breast cancer treatment: Systematic review. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2021, 30, e13440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafn, B.S.; Christensen, J.; Larsen, A.; Bloomquist, K. Prospective Surveillance for Breast Cancer–Related Arm Lymphedema: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 1009–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundred, N.; Foden, P.; Todd, C.; Morris, J.; Watterson, D.; Purushotham, A.; Bramley, M.; Riches, K.; Hodgkiss, T.; et al.; the Investigators of BEA/PLACE studies Increases in arm volume predict lymphoedema and quality of life deficits after axillary surgery: a prospective cohort study. Br. J. Cancer 2020, 123, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, E.S.; Bowen, M.J.; Chen, W.F. Diagnostic accuracy of bioimpedance spectroscopy in patients with lymphedema: A retrospective cohort analysis. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2018, 71, 1041–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihara, M.; Hara, H.; Araki, J.; Kikuchi, K.; Narushima, M.; Yamamoto, T.; Iida, T.; Yoshimatsu, H.; Murai, N.; Mitsui, K.; et al. Indocyanine Green (ICG) Lymphography Is Superior to Lymphoscintigraphy for Diagnostic Imaging of Early Lymphedema of the Upper Limbs. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e38182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akita, S.; Nakamura, R.; Yamamoto, N.; Tokumoto, H.; Ishigaki, T.; Yamaji, Y.; Sasahara, Y.; Kubota, Y.; Mitsukawa, N.; Satoh, K. Early Detection of Lymphatic Disorder and Treatment for Lymphedema following Breast Cancer. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2016, 138, 192e–202e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soran, A.; Bengur, F.B.; Rodriguez, W.; Chroneos, M.Z.; Sezgin, E. Early Detection of Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema: Accuracy of Indocyanine Green Lymphography Compared with Bioimpedance Spectroscopy and Subclinical Lymphedema Symptoms. Lymphat. Res. Biol. 2023, 21, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.; Azuelos, A. Near-Infrared Based Technologies. In Supermicrosurgical Lymphatico Venular Anastomosis: A Practical Textbook; Visconti, G., Hayashi, A., Eds.; Lulu, 2020; pp. 1–404. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, T.; Matsuda, N.; Doi, K.; Oshima, A.; Yoshimatsu, H.; Todokoro, T.; Ogata, F.; Mihara, M.; Narushima, M.; Iida, T.; et al. The Earliest Finding of Indocyanine Green Lymphography in Asymptomatic Limbs of Lower Extremity Lymphedema Patients Secondary to Cancer Treatment. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2011, 128, 314e–321e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, T.; Yamamoto, N.; Hara, H.; Mihara, M.; Narushima, M.; Koshima, I. Upper Extremity Lymphedema Index. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2013, 70, 47–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brahma, B.; Putri, R.I.; Reuwpassa, J.O.; Tuti, Y.; Alifian, M.F.; Sofyan, R.F.; Iskandar, I.; Yamamoto, T. Lymphaticovenular Anastomosis in Breast Cancer Treatment-Related Lymphedema: A Short-Term Clinicopathological Analysis from Indonesia. J. Reconstr. Microsurg. 2021, 37, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, T.; Yamamoto, N.; Kageyama, T.; Sakai, H.; Fuse, Y.; Tsuihiji, K.; Tsukuura, R. Technical pearls in lymphatic supermicrosurgery. Glob. Heal. Med. 2020, 2, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savetsky, I.L.; Torrisi, J.S.; Cuzzone, D.A.; Ghanta, S.; Albano, N.J.; Gardenier, J.C.; Joseph, W.J.; Mehrara, B.J. Obesity increases inflammation and impairs lymphatic function in a mouse model of lymphedema. Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 2014, 307, H165–H172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, K.S.; Karaman, S.; Proulx, S.T.; Ochsenbein, A.M.; Luciani, P.; Leroux, J.-C.; Wolfrum, C.; Detmar, M. Chronic High-Fat Diet Impairs Collecting Lymphatic Vessel Function in Mice. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e94713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, J.M.; New, J.; Hamilton, C.D.; Lominska, C.; Shnayder, Y.; Thomas, S.M. Radiation-induced fibrosis: mechanisms and implications for therapy. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 141, 1985–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avraham, T.; Daluvoy, S.; Zampell, J.; Yan, A.; Haviv, Y.S.; Rockson, S.G.; Mehrara, B.J. Blockade of Transforming Growth Factor-β1 Accelerates Lymphatic Regeneration during Wound Repair. Am. J. Pathol. 2010, 177, 3202–3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavin, N.W.; Avraham, T.; Fernandez, J.; Daluvoy, S.V.; et al. TGF-β 1 is a negative regulator of lymphatic regeneration during wound repair. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 2008, 295, H2113–H2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, T.S.; Nepiyushchikh, Z.; Hooks, J.S.T.; Razavi, M.S.; Lewis, T.; Clement, C.C.; Thoresen, M.; Cribb, M.T.; Ross, M.K.; Gleason, R.L.; et al. Lymphatic remodelling in response to lymphatic injury in the hind limbs of sheep. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 4, 649–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, Y.; Otsubo, R.; Shinohara, S.; Morita, M.; Kuba, S.; Matsumoto, M.; Yamanouchi, K.; Yano, H.; Eguchi, S.; Nagayasu, T. Lymphedema After Axillary Lymph Node Dissection in Breast Cancer: Prevalence and Risk Factors—A Single-Center Retrospective Study. Lymphat. Res. Biol. 2022, 20, 600–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren, A.G.; Brorson, H.; Borud, L.J.; Slavin, S.A. Lymphedema. Ann Plast Surg 2007, 59, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilbreath, S.; Refshauge, K.; Beith, J.; Ward, L.; Ung, O.; Dylke, E.; French, J.; Yee, J.; Koelmeyer, L.; Gaitatzis, K. Risk factors for lymphoedema in women with breast cancer: A large prospective cohort. Breast 2016, 28, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Invernizzi, M.; Corti, C.; Lopez, G.; Michelotti, A.; Despini, L.; Gambini, D.; Lorenzini, D.; Guerini-Rocco, E.; Maggi, S.; Noale, M.; et al. Lymphovascular invasion and extranodal tumour extension are risk indicators of breast cancer related lymphoedema: an observational retrospective study with long-term follow-up. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyigun, Z.E.; Duymaz, T.; Ilgun, A.S.; Alco, G.; Ordu, C.; Sarsenov, D.; Aydin, A.E.; Celebi, F.E.; Izci, F.; Eralp, Y.; et al. Preoperative Lymphedema-Related Risk Factors in Early-Stage Breast Cancer. Lymphat. Res. Biol. 2018, 16, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.R.; Singhal, D. Immediate lymphatic reconstruction. J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 118, 750–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasinski, B.B. Complete Decongestive Therapy for Treatment of Lymphedema. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2013, 29, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzo, J.; Manheimer, E.; McNeely, M.L.; Howell, D.M.; Weiss, R.; I Johansson, K.; Bao, T.; Bily, L.; Tuppo, C.M.; Williams, A.F.; et al. Manual lymphatic drainage for lymphedema following breast cancer treatment. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD003475–CD003475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramanandam, V.S.; Dylke, E.; Clark, G.M.; Daptardar, A.A.; Kulkarni, A.M.; Nair, N.S.; Badwe, R.A.; Kilbreath, S.L. Prophylactic Use of Compression Sleeves Reduces the Incidence of Arm Swelling in Women at High Risk of Breast Cancer–Related Lymphedema: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 2004–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochalek, K.; Gradalski, T.; Partsch, H. Preventing Early Postoperative Arm Swelling and Lymphedema Manifestation by Compression Sleeves After Axillary Lymph Node Interventions in Breast Cancer Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2017, 54, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochalek, K.; Partsch, H.; Gradalski, T.; Szygula, Z. Do Compression Sleeves Reduce the Incidence of Arm Lymphedema and Improve Quality of Life? Two-Year Results from a Prospective Randomized Trial in Breast Cancer Survivors. Lymphat. Res. Biol. 2019, 17, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paskett, E.D.; Le-Rademacher, J.; Oliveri, J.M.; Liu, H.; Seisler, D.K.; Sloan, J.A.; Armer, J.M.; Naughton, M.J.; Hock, K.; Schwartz, M.; et al. A randomized study to prevent lymphedema in women treated for breast cancer: CALGB 70305 (Alliance). Cancer 2020, 127, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coriddi, M.; Mehrara, B.; Skoracki, R.; Singhal, D.; Dayan, J.H. Immediate Lymphatic Reconstruction: Technical Points and Literature Review. Plast. Reconstr. Surg.- Glob. Open 2021, 9, e3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boccardo, F.; Casabona, F.; De Cian, F.; Friedman, D.; Villa, G.; Bogliolo, S.; Ferrero, S.; Murelli, F.; Campisi, C. Lymphedema Microsurgical Preventive Healing Approach: A New Technique for Primary Prevention of Arm Lymphedema After Mastectomy. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2009, 16, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akita, S.; Mitsukawa, N.; Kuriyama, M.; Hasegawa, M.; Kubota, Y.; Tokumoto, H.; Ishigaki, T.; Hanaoka, H.; Satoh, K. Suitable therapy options for sub-clinical and early-stage lymphoedema patients. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2014, 67, 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.; Yamamoto, N.; Yamashita, M.; Furuya, M.; Hayashi, A.; Koshima, I. Efferent Lymphatic Vessel Anastomosis. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2016, 76, 424–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahma, B.; Yamamoto, T.; Agdelina, C.; Adella, D.; Putri, R.I.; Hanifah, W.; Sundah, V.H.; Perdana, A.B.; Putra, M.R.A.; Taher, A.; et al. Immediate-delayed lymphatic reconstruction after axillary lymph nodes dissection for locally advanced breast cancer-related lymphedema prevention: Report of two cases. Microsurgery 2023, 44, e31033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Patients, no (%) n=69 |

|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), years | 47.0 (40.0-54.0) |

| BMI, mean± SD kg/m2 | 26.3 ± 5.1 |

| Breast cancer stage | |

| II A | 11 (15.9) |

| II B | 8 (11.6) |

| III A | 15 (21.7) |

| III B | 15 (21.7) |

| III C | 16 (23.2) |

| IV | 4 (5.8) |

| Breast surgery | |

| Mastectomy | 53 (76.8) |

| BCS | 15 (21.7) |

| Wide excision | 1 (1.4) |

| ALND Level | |

| I-II | 51 (73.9) |

| I-III | 18 (26.1) |

| Radiotherapy | |

| Yes | 42 (60.9) |

| No | 27 (39.1) |

| Chemotherapy | |

| Yes | 64 (93.8) |

| No | 5 (7.2) |

| Hormonal therapy | |

| Yes | 49 (71.0) |

| No | 20 (29.0) |

| Dissected Lymph Nodes, median (IQR) | 18 (14-21) |

| Lymph Nodes Metastases, median (IQR) | 2 (0-10) |

| Lymph Vessel Obstruction | |

| Yes | 16 (23.2) |

| No | 52 (75.4) |

| Missing | 1 (1.4) |

| Histopathology Feature | |

| NST | 66 (95.7) |

| Lobular | 1 (1.4) |

| Others | 2 (2.9) |

| Breast Cancer Subtype | |

| Luminal A | 4 (5.8) |

| Luminal B HER2- | 17 (24.6) |

| Luminal B HER2+ | 9 (13) |

| HER2+ | 18 (26.1) |

| TNBC | 21 (30.4) |

| Variable | Patients, n (%) N = 35 |

|---|---|

| Symptoms | |

| Yes | 25 (71.4) |

| Heaviness | 15 (60) |

| Swelling | 12 (48) |

| Pain | 6 (24) |

| No | 10 (28.6) |

| UEL Index percentage difference > 10% | |

| Yes | 11 (31.4) |

| No | 24 (68.6) |

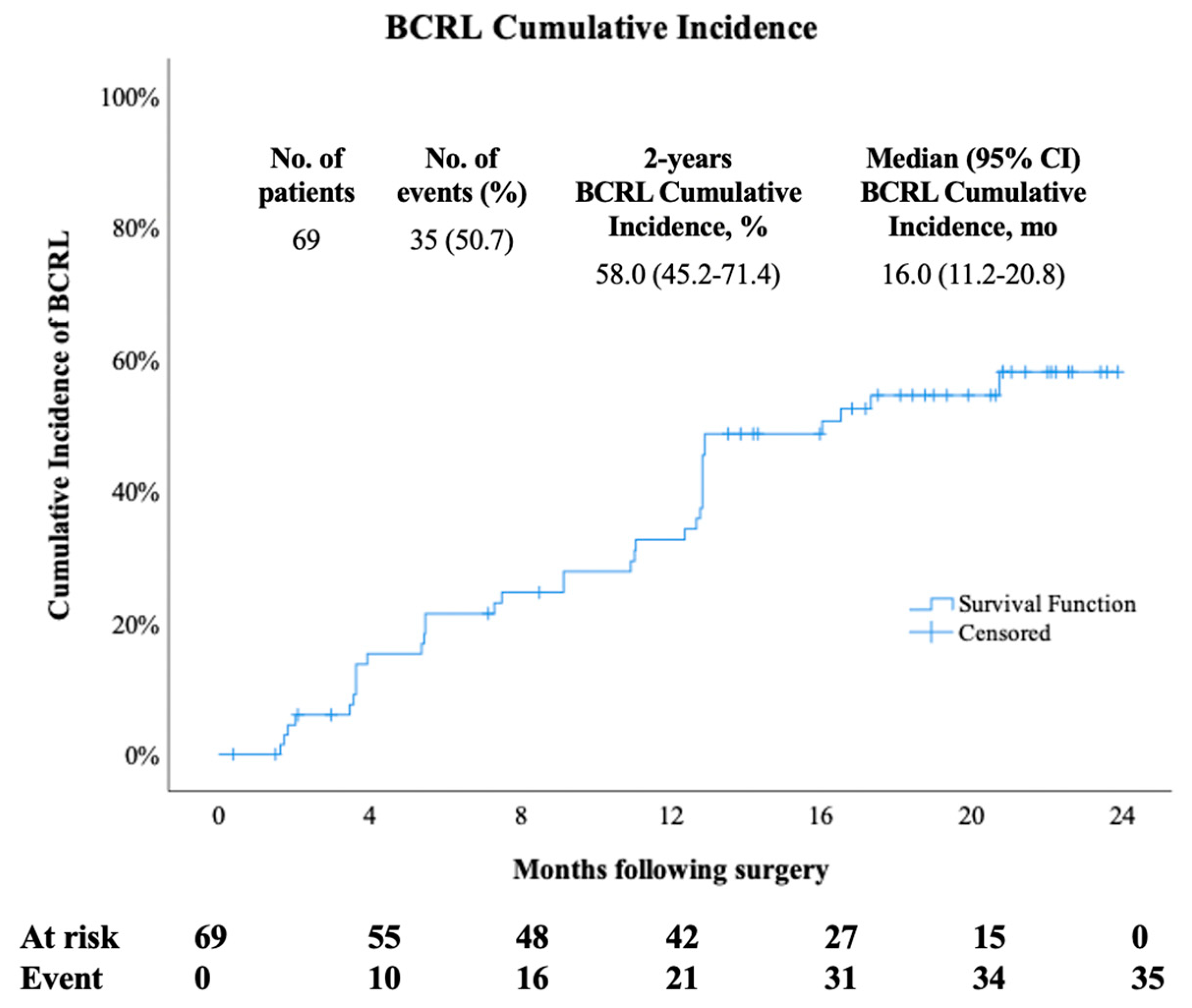

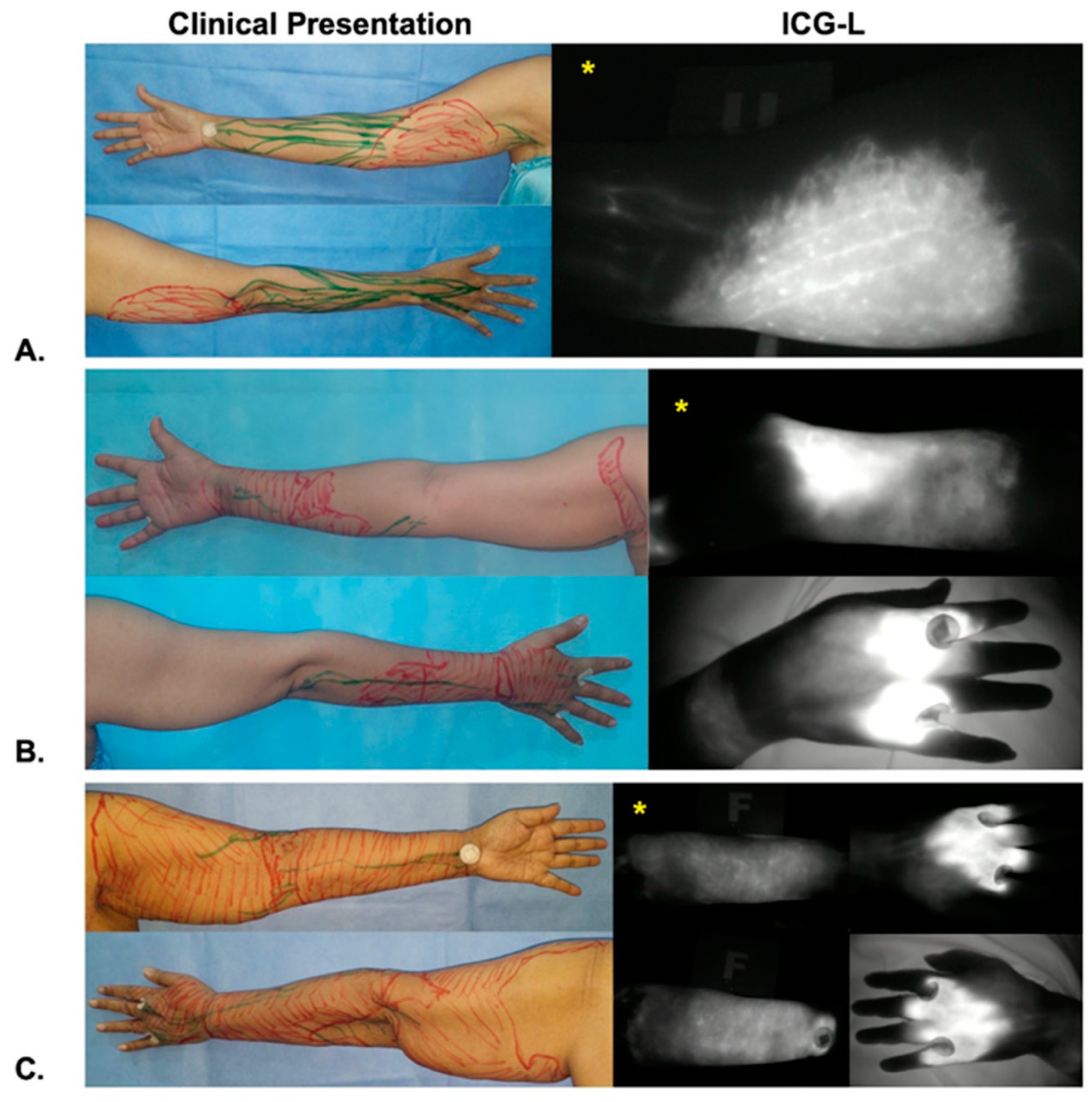

| ICG-L Stage at Onset | |

| II | 18 (51.4) |

| III | 14 (40.0) |

| IV | 3 (8.6) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).