Submitted:

14 July 2025

Posted:

16 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Age ≥70 years.

- Histologically confirmed diagnosis of invasive breast carcinoma.

- Negative axillary status confirmed by axillary ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT). Patients with suspicious imaging findings but negative preoperative biopsy (vacuum-assisted biopsy [VAB] or core needle biopsy [CNB]) were also included.

- No neoadjuvant treatment.

- Patients who underwent either mastectomy or breast-conserving surgery.

- Patients in whom sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) was performed.

- Patients who did not undergo surgical intervention.

- Lack of axillary assessment via SLNB.

2.1. Statistical Analysis:

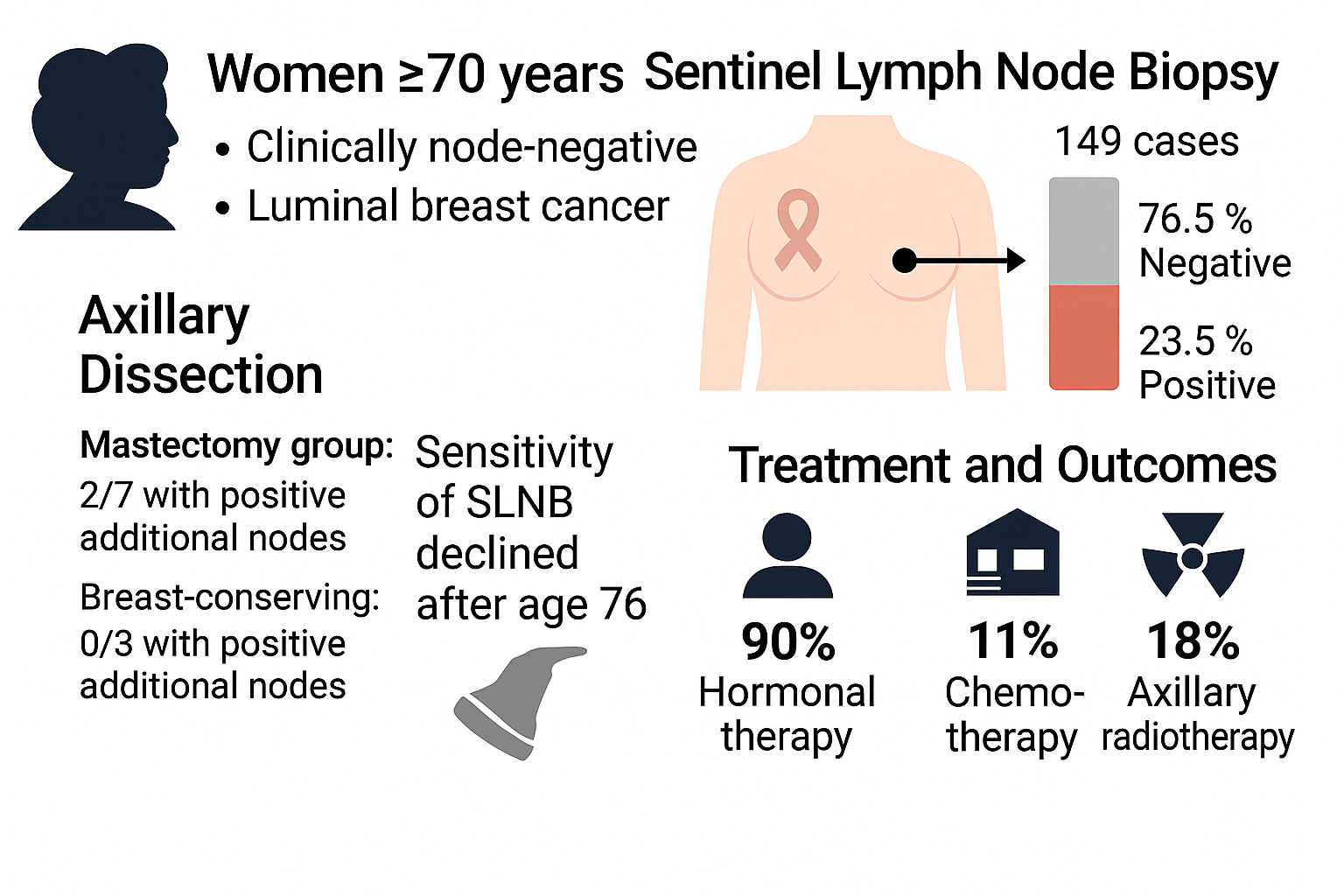

3. Results

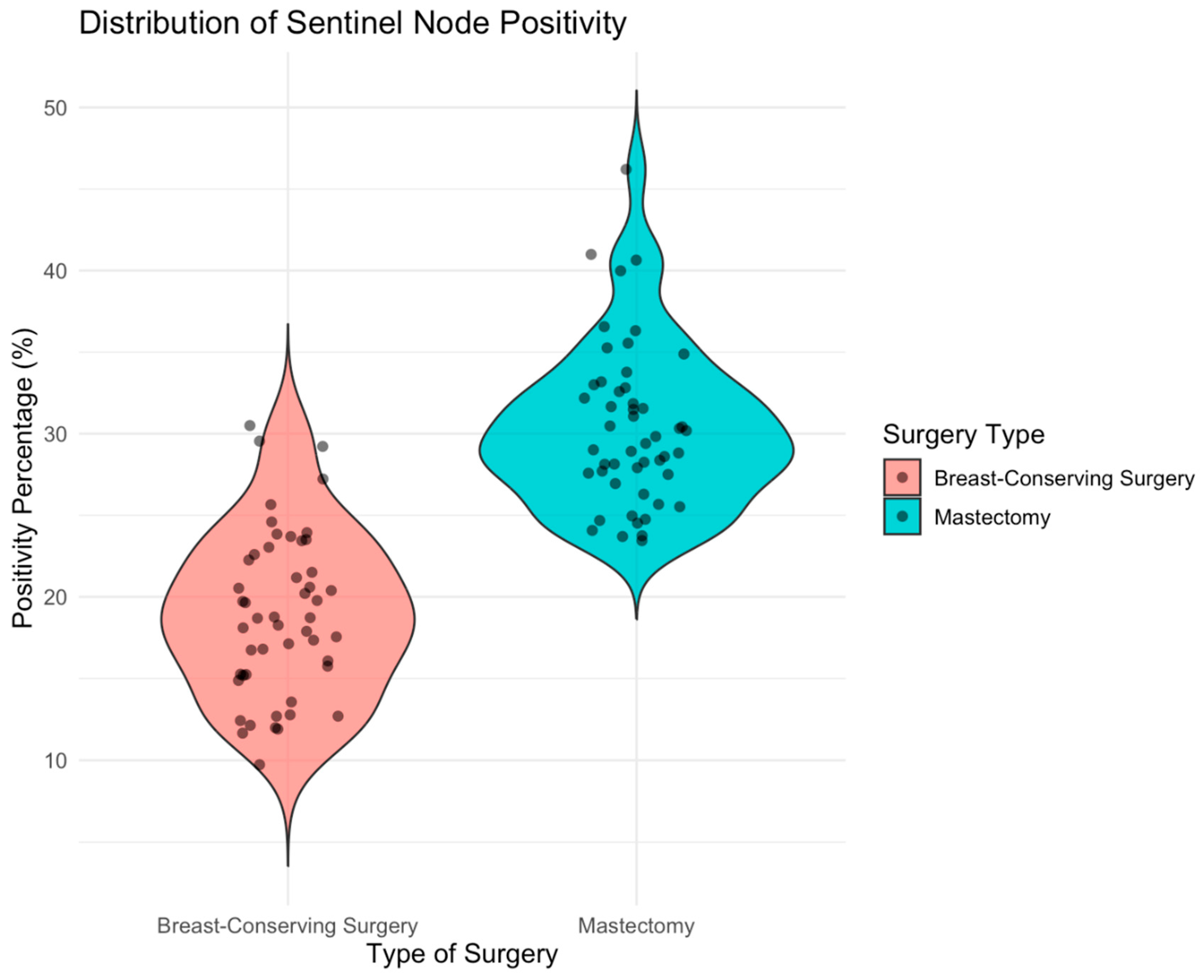

3.1. Analysis by Type of Surgery:

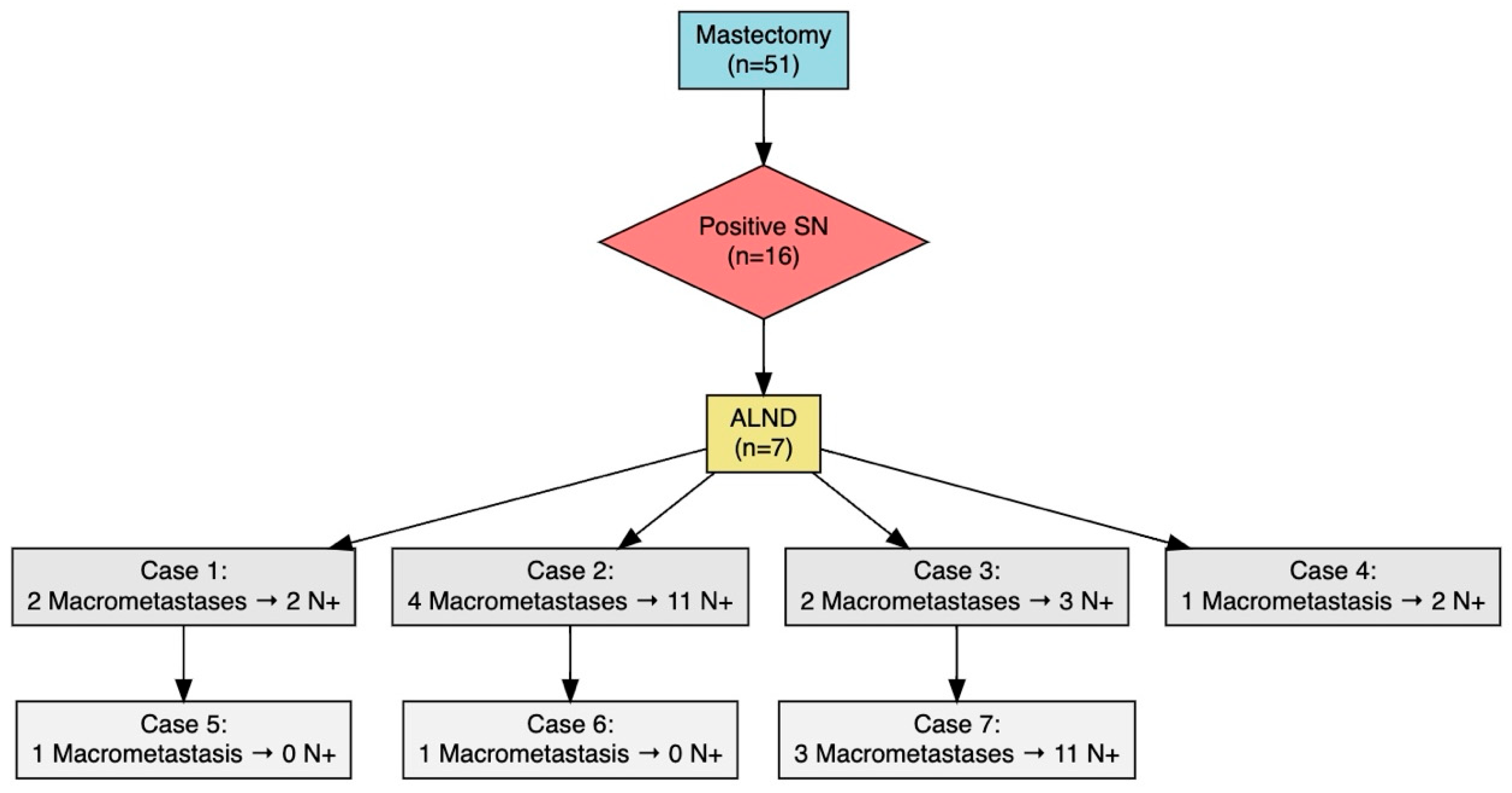

3.1.1. Mastectomy Group:

- 3 patients with one macrometastasis (2 of whom had no additional positive nodes on ALND).

- 4 patients with two or more macrometastases, all of whom had additional positive lymph nodes on ALND. In this subgroup, 100% of patients who underwent ALND had further nodal involvement.

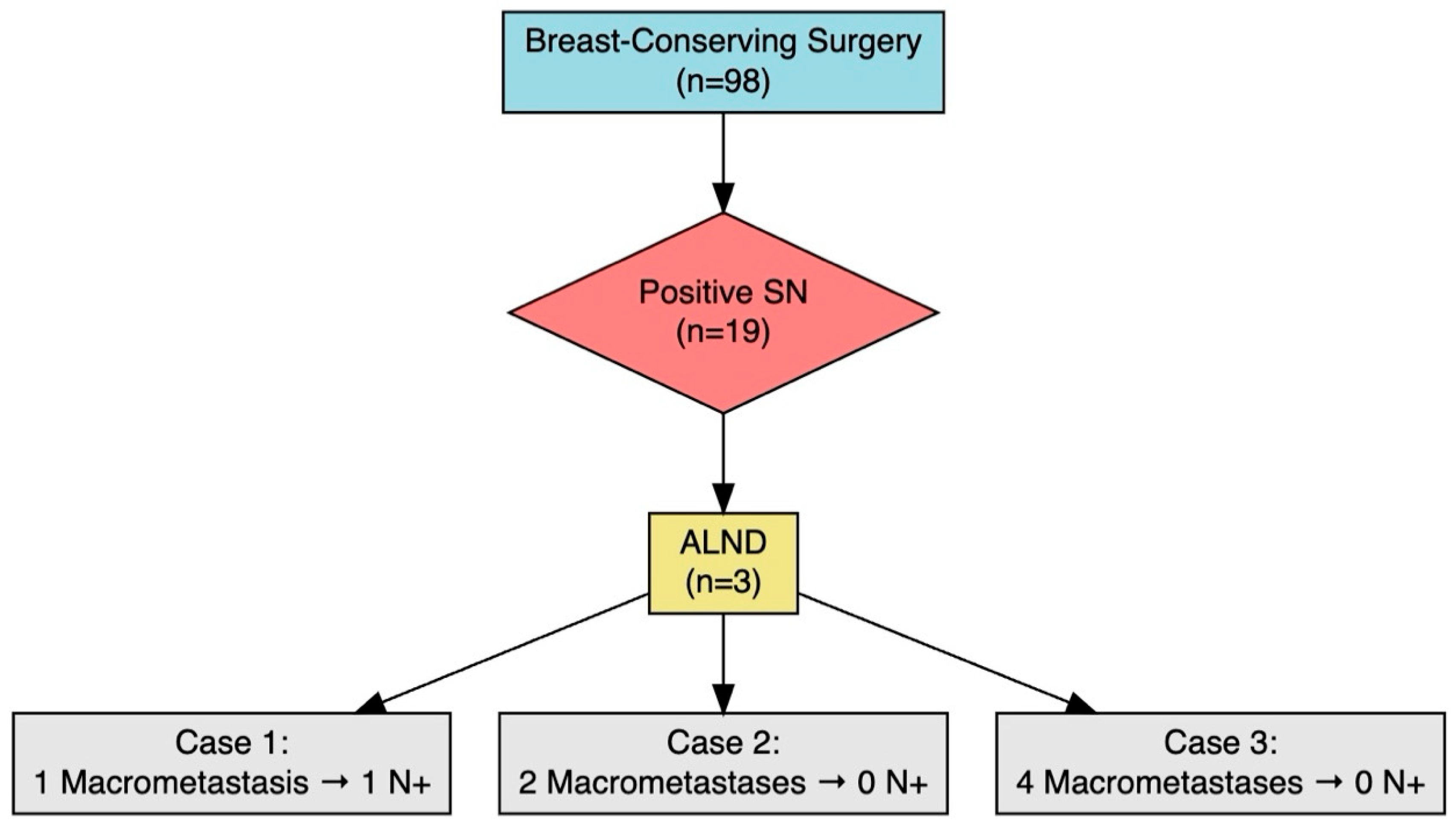

3.1.2. Breast-Conserving Surgery Group:

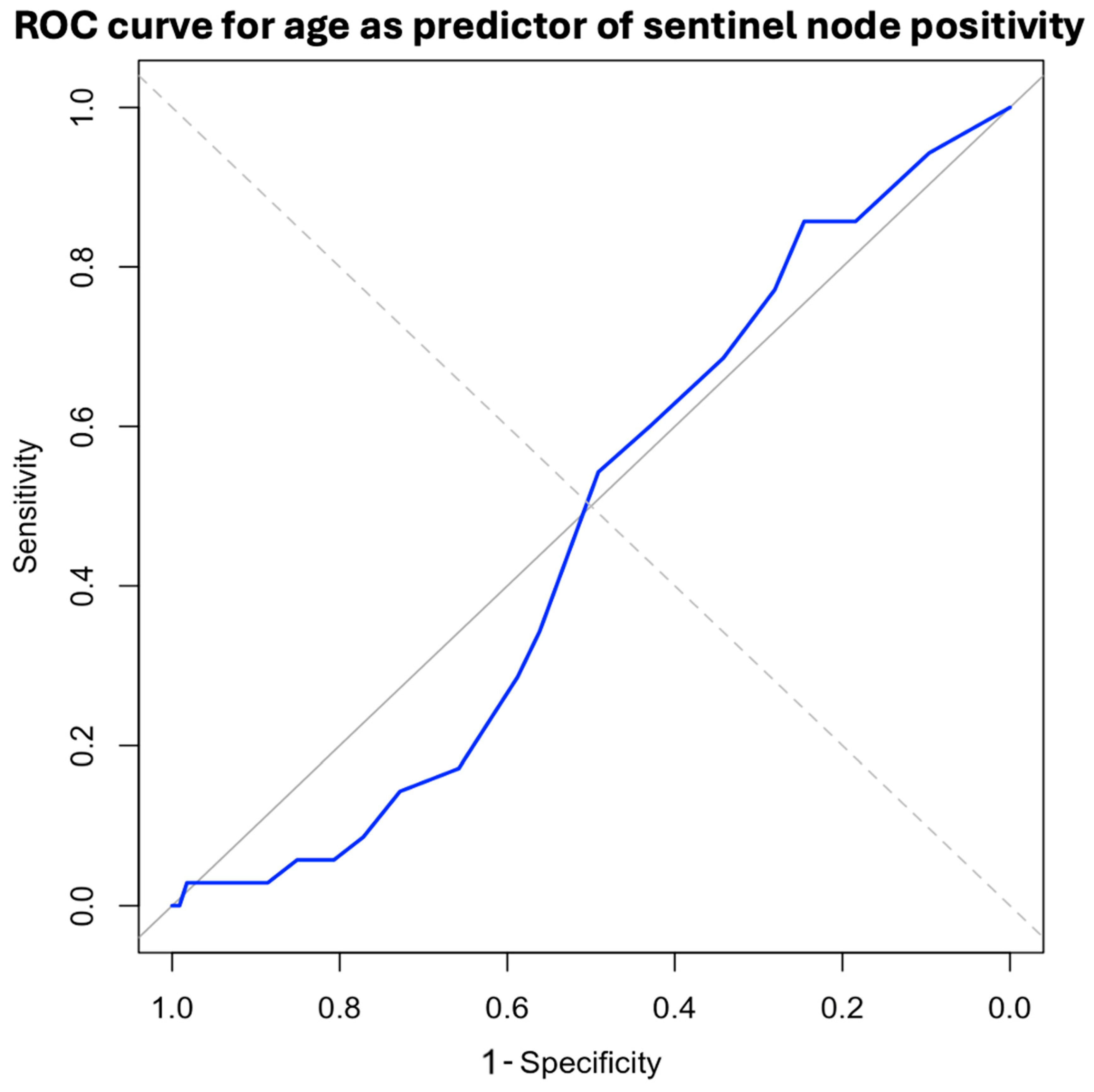

3.1.3. Sensitivity and Specificity Analysis of Sentinel Node According to Age:

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Ethical Considerations

Conflict of Interest

References

- Minami CA, Bryan AF, Freedman RA, Revette AC, Schonberg MA, King TA, et al. Assessment of Oncologists’ Perspectives on Omission of Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy in Women 70 Years and Older with Early-Stage Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(8): e2228524. [CrossRef]

- Sevensma KE, Lewis CR. Axillary sentinel lymph node biopsy. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. PMID: 31985977.

- Boughey JC, Haffty BG, Habermann EB, Hoskin TL, Goetz MP. Has the Time Come to Stop Surgical Staging of the Axilla for All Women Age 70 Years or Older with Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer? Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(3):614-17. [CrossRef]

- Vogel CL, Johnston MA, Capers C, Braccia D. Toremifene for breast cancer: A review of 20 years of data. Clin Breast Cancer. 2014;14(1):1-9. [CrossRef]

- Rudenstam CM, Zahrieh D, Forbes JF, Crivellari D, Holmberg SB, Rey P, et al. Randomized trial comparing axillary clearance versus no axillary clearance in older patients with breast cancer: First results of International Breast Cancer Study Group trial 10-93. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(3):337-44. [CrossRef]

- Heidinger M, Maggi N, Dutilh G, Mueller M, Eller RS, Loesch JM, et al. Use of sentinel lymph node biopsy in elderly patients with breast cancer – 10-year experience from a Swiss university hospital. World J Surg Oncol. 2023;21(1). [CrossRef]

- Marco Sanz L, del Olmo Bautista S, Sánchez Quirós H, Pérez Martínez Y, Gutiérrez García S, Palomo Cabañes V, et al. Breast cancer in patients aged over 80 years: Primary treatment. Revista de Senologia y Patologia Mamaria. 2025;38(3). [CrossRef]

- Giuliano AE, Ballman K V., McCall L, Beitsch PD, Brennan MB, Kelemen PR, et al. Effect of axillary dissection vs no axillary dissection on 10-year overall survival among women with invasive breast cancer and sentinel node metastasis: The ACOSOG Z0011 (Alliance) randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318(10):918–26. [CrossRef]

- Qualina Abreu PE, González Pereira S. Breast cancer in patients over 70 years of age: Clinical presentation, histopathological features and therapeutic approach in Argentina. Rev Argent Mastol. 2019;38(140):58–81.

- Acosta M V, Acosta F V, Ramírez C AK, Marín E, Contreras A, Longobardi I, et al. Breast cancer in patients over 80 years of age: Are we still performing sentinel lymph node biopsy? Rev Venez Oncol. 2024;36(4):212–21.

- Pijuan i Panadés N, Nogueiras Pérez R, Gumí Caballero I, López Mestres A, Medina Argemi S, Ramírez Pujadas A, et al. Do women with breast cancer older than 70 years receive equal treatment to younger women? Rev Senol Patol Mamar. 2020;33(2):50–6. [CrossRef]

- Minami CA, Jin G, Freedman RA, Schonberg MA, King TA, Mittendorf EA. Physician-level variation in axillary surgery in older adults with T1N0 hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: A retrospective population-based cohort study. J Geriatr Oncol. 2024 Jun 1;15(5). [CrossRef]

- Minami CA, Dey T, Chen YJ, Freedman RA, Lorentzen EH, King TA, et al. Regional Variation in Deescalated Therapy in Older Adults With Early-Stage Breast Cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(10):e2441152. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Wang L, Wang Y, Ma L, Zheng R, Ding J, et al. Omission of sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with clinically axillary lymph node-negative early breast cancer (OMSLNB): protocol for a prospective, non-inferiority, single-arm, phase II clinical trial in China. BMJ Open. 2024;14(9):e087700. [CrossRef]

- Wang T, Mott N, Miller J, Berlin NL, Hawley S, Jagsi R, et al. Patient Perspectives on Treatment Options for Older Women with Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer: A Qualitative Study. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9). [CrossRef]

- Castelo M, Hansen BE, Paszat L, Baxter NN, Scheer AS. Omission of Axillary Staging and Survival in Elderly Women With Early Stage Breast Cancer. Ann Surg Open. 2022;3(2):e159. [CrossRef]

- Fitzal F, Helfgott R, Moinfar F, Gnant M. Sized Influences Nodal Status in Women Aged #70 with Endocrine Responsive Breast Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(Suppl 3):555-6. [CrossRef]

- Chagpar AB, McMasters KM, Edwards MJ. Can sentinel node biopsy be avoided in some elderly breast cancer patients? Ann Surg. 2009;249(3):455–60. [CrossRef]

- Esposito E, Di Micco R, Gentilini OD. Sentinel node biopsy in early breast cancer. A review on recent and ongoing randomized trials. Breast. 2017;36:14-9. [CrossRef]

- Luo SP, Zhang J, Wu Q Sen, Lin YX, Song CG. Association of Axillary Lymph Node Evaluation With Survival in Women Aged 70 Years or Older With Breast Cancer. Front Oncol. 2021;10:596545. [CrossRef]

- Davey MG, Kerin EP, McLaughlin RP, Barry MK, Malone CM, Elwahab SA, et al. Evaluating the Necessity for Routine Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy in Postmenopausal Patients Being Treated for Clinically Node Negative Breast Cancer the Era of RxPONDER. Clin Breast Cancer. 2023;23(5):500–7. [CrossRef]

- Lee J, Noh J, Jeong JY. Oncological outcomes of omitting sentinel lymph node biopsy in elderly patients with breast cancer. Asian J Surg. 2020;43(11):1090-2. [CrossRef]

- Daly GR, Dowling GP, Said M, Qasem Y, Hembrecht S, Calpin GG, et al. Impact of Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy on Management of Older Women With Clinically Node-Negative, Early-Stage, ER+/HER2−, Invasive Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Breast Cancer. 2024;24(8):e681-8.e1. [CrossRef]

- Pilewskie M, Sevilimedu V, Eroglu I, Le T, Wang R, Morrow M, et al. How Often Do Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy Results Affect Adjuvant Therapy Decisions Among Postmenopausal Women with Early-Stage HR+/HER2− Breast Cancer in the Post-RxPONDER Era? Ann Surg Oncol. 2022;29(10):6267–73. [CrossRef]

- Jatoi I, Kunkler IH. Omission of sentinel node biopsy for breast cancer: Historical context and future perspectives on a modern controversy. Cancer. 2021;127(23):4376-83. [CrossRef]

- Kunkler IH et al. Breast-conserving surgery with or without irradiation in women aged 65 years or older with early breast cancer (PRIME II): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(3):266–73. [CrossRef]

- Wang T, Baskin A, Miller J, Metz A, Matusko N, Hughes T, et al. Trends in Breast Cancer Treatment De-Implementation in Older Patients with Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer: A Mixed Methods Study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28(2):902–13. [CrossRef]

- McEvoy AM, Poplack S, Nickel K, Olsen MA, Ademuyiwa F, Zoberi I, et al. Cost-effectiveness analyses demonstrate that observation is superior to sentinel lymph node biopsy for postmenopausal women with HR + breast cancer and negative axillary ultrasound. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020;183(2):251-62. [CrossRef]

- Hrebinko KA, Bryce CL, Downs-Canner S, Diego EJ, Myers SP. Cost-effectiveness of Choosing Wisely guidelines for axillary observation in women older than age 70 years with hormone receptor–positive, clinically node-negative, operable breast tumors. Cancer. 2022;128(12):2258–68. [CrossRef]

- Piñero Madrona A, Giménez J, Merck B, Vázquez C. Consensus meeting on selective biopsy of the sentinel node in breast cancer. Spanish Society of Senology and Breast Disease. Rev Esp Med Nucl. 2007;26(3):176-80. [CrossRef]

- Alamoodi M, Wazir U, Mokbel K, Patani N, Varghese J, Mokbel K. Omitting Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy after Neoadjuvant Systemic Therapy for Clinically Node Negative HER2 Positive and Triple Negative Breast Cancer: A Pooled Analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(13): 3325. [CrossRef]

- Carleton N, Zou J, Fang Y, Koscumb SE, Shah OS, Chen F, et al. Outcomes after Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy and Radiotherapy in Older Women with Early-Stage, Estrogen Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(4). [CrossRef]

- Rebaza Vasquez LP, Ponce de la Torre J, Alarco R, Ayala Moreno J, Gomez Moreno H. Axillary management in early-stage breast cancer with upfront surgery and positive sentinel lymph node. ecancermedicalscience. 2021;15:1193. [CrossRef]

- Tuttle TM, Hui JYC, Yuan J. Omitting Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy in Elderly Patients: A Lost Opportunity? Vol. 28, Annals of Surgical Oncology. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28(9):5442-3. [CrossRef]

- Chung AP, Dang CM, Karlan SR, Amersi FF, Phillips EM, Boyle MK, et al. A Prospective Study of Sentinel Node Biopsy Omission in Women Age ≥ 65 Years with ER+ Breast Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2024;31(5):3160–7. [CrossRef]

- Reimer T. Omission of axillary sentinel lymph node biopsy in early invasive breast cancer. Breast. 2023;67:124–8. [CrossRef]

- Reimer T, Stachs A, Veselinovic K, Kühn T, Heil J, Polata S et al. Axillary Surgery in Breast Cancer - Primary Results of the INSEMA Trial. N Engl J Med. 2025;392(11):1051-64. [CrossRef]

- Kell MR, Burke JP, Barry M, Morrow M. Outcome of axillary staging in early breast cancer: A meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;120(2):441–7. [CrossRef]

- Lewis JD, Chagpar AB, Shaughnessy EA, Nurko J, McMasters K, Edwards MJ. Excellent outcomes with adjuvant toremifene or tamoxifen in early stage breast cancer. Cancer. 2010;116(10):2307–15. [CrossRef]

- Fitzal F, Helfgott R, Moinfar F, Gnant M. Sized Influences Nodal Status in Women Aged #70 with Endocrine Responsive Breast Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(Suppl 3):555-6. [CrossRef]

- Reimer T, Engel J, Schmidt M, Offersen BV, Smidt ML, Gentilini OD. Is Axillary Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy Required in Patients Who Undergo Primary Breast Surgery? Breast Care (Basel). 2018;13(5):324-30. [CrossRef]

- Williams AD, Khan AJ, Sevilimedu V, Barrio A V., Morrow M, Mamtani A. Omission of Intraoperative Frozen Section May Reduce Axillary Overtreatment Among Clinically Node-Negative Patients Having Upfront Mastectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022;29(13):8037–43. [CrossRef]

- Hu X, Xue J, Peng S, Yang P, Yang Z, Yang L, et al. Preoperative Nomogram for Predicting Sentinel Lymph Node Metastasis Risk in Breast Cancer: A Potential Application on Omitting Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy. Front Oncol. 2021;11:665240. [CrossRef]

|

Mastectomy (%) |

Breast-conserving surgery (%) |

Total (%) |

|||

| n | 51 (34.23) | 98 (65.7) | 149 | ||

| Age | Mean age ± SD (years) | 78.51 ± 5.83 | 76.50 ± 4,80 | 77.19 ± 5.24 | |

| 95% CI range (years) | 76.87 – 80.15 | 75.54 - 77,46 | 76.34 – 78.04 | ||

| Sexe | Female | 50 (98.04) | 98 (100.00) | 148 (99.33) | |

| Male | 1 (1.96) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.67) | ||

| ASA | I | 1 (1.96) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.67) | |

| II | 36 (70.59) | 79 (80.61) | 115 (77.18) | ||

| III | 13 (25.49) | 19 (19.39) | 32 (21.48) | ||

| IV | 1 (1.96) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.67) | ||

| V | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Breast laterality | Right | 22 (43.14) | 57 (58.16) | 79 (53.02) | |

| Left | 29 (56.86) | 41 (41.84) | 70 (46.98) | ||

| Previous breast neoplasm | 6 (11.76) | 13 (13.27) | 19 (12.75) | ||

| Breast laterality | Ipsilateral | 1 (16.67) | 1 (7.69) | 2 (10.53) | |

| Contralateral | 5 (83.33) | 12 (92.31) | 17 (89.47) | ||

| Molecular type | Same | 3 (50.00) | 5 (38.46) | 8 (42.11) | |

| Diferent | 2 (33.33) | 7 (53.85) | 9 (47.38) | ||

| Not available | 1 (16.67) | 1 (7.69) | 2 (10.53) | ||

| Imaging diagnosis | Ultrasound | 51 (100.00) | 98 (100.00) | 149 (100.00) | |

| MRI | 11 (21.57) | 19 (19.39) | 30 (20.13) | ||

| PET-CT | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1.02) | 1 (0.67) | ||

|

Mastectomy (%) |

Breast-conserving surgery (%) |

Total (%) |

|||

| Histological type | Invasive carcinoma of no special type | 24 (47.06) | 63 (64.29) | 87 (58.39) | |

| Invasive lobular carcinoma | 16 (31.37) | 14 (14.29) | 30 (20.13) | ||

| Invasive ductal carcinoma | 2 (3.92) | 3 (3.06) | 5 (3.36) | ||

| Mucinous carcinoma | 6 (11.76) | 4 (4.08) | 5 (3.36) | ||

| Solid papillary carcinoma | 1 (1.96) | 3 (3.06) | 4 (2.68) | ||

| Micropapillary carcinoma | 0 (0,00) | 0 (0.00) | 5 (3.36) | ||

| Mixed invasive carcinoma | 2 (3.92) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (1.34) | ||

| Invasive papillary carcinoma | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1.02) | 1 (0.67) | ||

| Neuroendocrine tumor | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1.02) | 1 (0.67) | ||

| Invasive apocrine carcinoma | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1.02) | 1 (0.67) | ||

| Adenoid cystic carcinoma | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1.02) | 1 (0.67) | ||

| Solid invasive carcinoma | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1.02) | 1 (0.67) | ||

| Tubular and cribriform invasive carcinoma | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1.02) | 1 (0.67) | ||

| Invasive micropapillary carcinoma | 0 (0.00) | 5 (5.10) | 5 (3.36) | ||

| T stage | T1 | 25 (49.02) | 82 (83.67) | 107 (71.81) | |

| T2 | 23 (45.10) | 14 (14.29) | 37 (24.83) | ||

| T3 | 3 (5.88) | 2 (2.04) | 5 (3.36) | ||

| T4 | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Histological grade | I | 8 (15.69) | 26 (26.53) | 34 (22.82) | |

| II | 40 (78.43) | 65 (66.33) | 105 (70.47) | ||

| III | 3 (5.88) | 7 (7.14) | 10 (6.71) | ||

| Molecular type | Luminal A | 15 (29.41) | 52 (53.06) | 67 (44.97) | |

| Luminal B | 27 (52.94) | 34 (34.69) | 61 (40.94) | ||

| Luminal B-Her2+ | 3 (5.88) | 2 (2.04) | 5 (3.36) | ||

| Her2+ | 3 (5.88) | 3 (3.06) | 6 (4.03) | ||

| Triple-negative | 3 (5.88) | 7 (7.14) | 10 (6.71) | ||

| SLNB | Positive | 16 (31.37) | 19 (19.39) | 35 (23.49) | |

| Negative | 35 (68.63) | 79 (80.61) | 114 (76.51) | ||

| SLNB features | >1 micrometastases | 8 (50.00) | 7 (36.84) | 15 (42.86) | |

| 1 macrometastases | 7 (43.75) | 8 (42.11) | 20 (57.14) | ||

| Macrometastases + micrometastases | 1 (6.25) | 4 (21.05) | 5 (27.30) | ||

| ALND | 7 (13.73) | 3 (3.06) | 10 (6.71) | ||

| ALND features | pN0 | 35 (66.67) | 77 (77.55) | 112 (75.17) | |

| pN1 | 13 (25.49) | 20 (20.41) | 33 (22.15) | ||

| pN2 | 1 (1.96) | 1 (1.02) | 2 (1.34) | ||

| pN3 | 2 (3.92) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (1.34) | ||

|

Mastectomy (%) |

Breast-conserving surgery (%) |

Total (%) |

||||

| Breast adjuvant radiotherapy | 16 (37.21 | 86 (87.76) | 102 (68.46) | |||

| Axillary adjuvant radiotherapy | 9 (20.93) | 17 (17.35) | 26 (17.45) | |||

| Irradiated lymph node levels | I | 6 (66.67) | 15 (88.24) | 20 (76.92) | ||

| II | 6 (66.67) | 15 (88.24) | 20 (76.92) | |||

| III | 7 (77.78) | 9 (52.94) | 13 (50.00) | |||

| IV | 1 (11.11) | 6 (35.29) | 7 (26.92) | |||

| V | 0 (0.00) | 1 (5.88) | 1 (3.85) | |||

| Breast adjuvant hormonotherapy | 45 (88.24) | 89 (90.82%) | 134 (89.93) | |||

| Breast adjuvant chemotherapy | 8 (15.69) | 9 (7.50%) | 17 (11.41) | |||

| Mastectomy: | ||||||

| ALND | ||||||

| N+ | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 11 | |

| SLNB with criteria for ALND | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||

| 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 3 | 1 | |||||

| 4 | 1 | |||||

|

Breast-conserving surgery: | ||||||

| ALND | ||||||

| N+ | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 11 | |

| SLNB with criteria for ALND | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 2 | 1 | |||||

| 3 | ||||||

| 4 | 1 | |||||

| Age (years) | Sensibility | Specificity |

| 70 | 0.9429 | 0.9035 |

| 71 | 0.9 | 0.8596 |

| 72 | 0.8571 | 0.7851 |

| 73 | 0.8143 | 0.7368 |

| 74 | 0.7286 | 0.6886 |

| 75 | 0.6429 | 614 |

| 76 | 0.5714 | 0.5395 |

| 77 | 0.4429 | 0.4737 |

| 78 | 0.3143 | 0.4254 |

| 79 | 0.2286 | 0.3772 |

| 80 | 0.1571 | 307 |

| 81 | 0.1143 | 0.25 |

| 82 | 0.0714 | 0.2105 |

| 83 | 0.0571 | 0.1711 |

| 84 | 0.0429 | 0.1316 |

| 85 | 0.0286 | 0.0965 |

| 86 | 0.0286 | 0.0702 |

| 87 | 0.0286 | 0.0526 |

| 88 | 0.0286 | 0.0395 |

| 89 | 0.0286 | 0.0307 |

| 90 | 0.0286 | 0.0219 |

| 91 | 0.0214 | 0.0154 |

| 92 | 0.0071 | 11 |

| 93 | 0.0 | 0.0088 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).