1. Introduction

The forehand smash was reported as the last shot played in 29% and 22% of the men’s and women’s singles rallies at the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games (Abian-vicen et al., 2017). It is widely regarded as the most effective and aggressive stroke in badminton. The success of this stroke is to create a fast downward trajectory of the shuttlecock towards a desired location on the opposite court and to put opponent into a defensive situation (Phomsoupha & Laffaye, 2014). Unsurprisingly, the post-impact shuttlecock speed is often used to define the quality of the shot. As a result, substantial attention was given from researchers to understand the development of speed in badminton smash (King et al., 2020; Ramasamy et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2016), as well as to other similar projectile-hitting sporting motions such as the tennis serve (Gordon, 2006; Koike & Hashiguchi, 2014; Tanabe & Ito, 2007) and volleyball jump spike (Fuchs et al., 2019; Seminati et al., 2015; Serrien et al., 2016). At the elite level, the badminton smash shuttlecock speed may vary due to, but not limited to, body positioning, technique and timing (impact location) of the smash (McErlain-Naylor et al., 2020; Towler et al.,, 2023). However, to the authors’ knowledge, there is no study to date that has conducted any intra-individual analysis investigating why a given player’s shuttlecock speed may vary between smash strokes.

A higher velocity in the smash is associated with specific characteristics at the moment of racket-shuttlecock contact including a more internally rotated shoulder (King et al., 2020; Ramasamy et al., 2021), as well as reduced elevation of the shoulder and less extension of the elbow (Ramasamy et al., 2021). Additionally, a faster smash is linked to greater angular velocity of shoulder internal rotation, a factor contributing significantly (66%) to the development of racket head speed (Xiang Liu, Wangdo Kim, 2002). Other key elements contributing to the acceleration phase of the smash include forearm pronation (Rusdiana et al., 2016; Zhang & Sc, 2012) and wrist flexion (Rusdiana et al., 2016). Notably, the rotational motion of the trunk during both the backswing and forward acceleration phase also play a substantial role in achieving a faster smash speed (Teu et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2016). Furthermore a consistent impact location of the shuttlecock on the racket face is critical to minimise reductions in smash speed due to the impact location (McErlain-Naylor et al., 2020).

Previous research has considered differences in technique for overhead sports such as badminton, tennis and volleyball. In the badminton smash, significantly higher shoulder internal rotation, horizontal abduction and wrist flexion torque were found for skilled players compared to unskilled players (Rusdiana et al., 2021). Furthermore participants who produced faster smash speeds have been shown to have greater shoulder internal rotation at impact and greater pelvis-thorax separation angle in the transverse plane at the end of retraction compared to participants with slower smashes (King et al., 2020). In the tennis serve shoulder internal rotation has been shown to be the major contributor to the differences in horizontal racket head velocity between fast and slow servers (Tanabe & Ito, 2007). In the volleyball spike, differences in upper limb angular velocities during successful versus faulty spikes were found for phases: 35% to 45% and 76% to 100% of the motion (Sarvestan et al., 2021).

The parameters that contribute to intra individual variations in badminton smash speeds are unknown when the goal is to maximise shuttlecock speed. This does not include times where a reduction in speed may be the goal in favour of a different trajectory e.g., a steeper smash (‘stick smash’). Previously, several key determinants have been identified to differentiate between shuttlecock speed across a cohort of players, however, these results should not be generalised to the individual. Different players could have adopted a different smash technique and/or choice of sequencing and timing patterns depending on their individual skills or preferences (Phomsoupha & Laffaye, 2014). As such, the objective of this study was to investigate the causes of reduction in intra-individual shuttlecock speed during the badminton smash among Malaysian elite players. Understanding whether technique and/or racket / shuttlecock variables cause reductions in the shuttlecock speed at an individual level will allow the coaches and practitioners to better advise the players on how to consistently execute their fastest smash.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Nineteen-elite male Malaysian badminton players were recruited for this study (age 20.2 ± 0.7 years, mass 71.7 ± 4.5 kg, height 1.77 ± 0.06 m; reported as mean ± SD). All players were in preparation for competition and injury-free at the time of data collection. Ethical approval was obtained from National Sports Institute of Malaysia (ISN) Research Ethics Committee and written informed consent of participants was provided prior to their participation. Players own rackets were used for all testing with the manufacturer reported unstrung racket mass of 84.0 ± 1.8 g and self-reported string tensions of 29.8 ± 0.7 lb.

2.2. Data collection

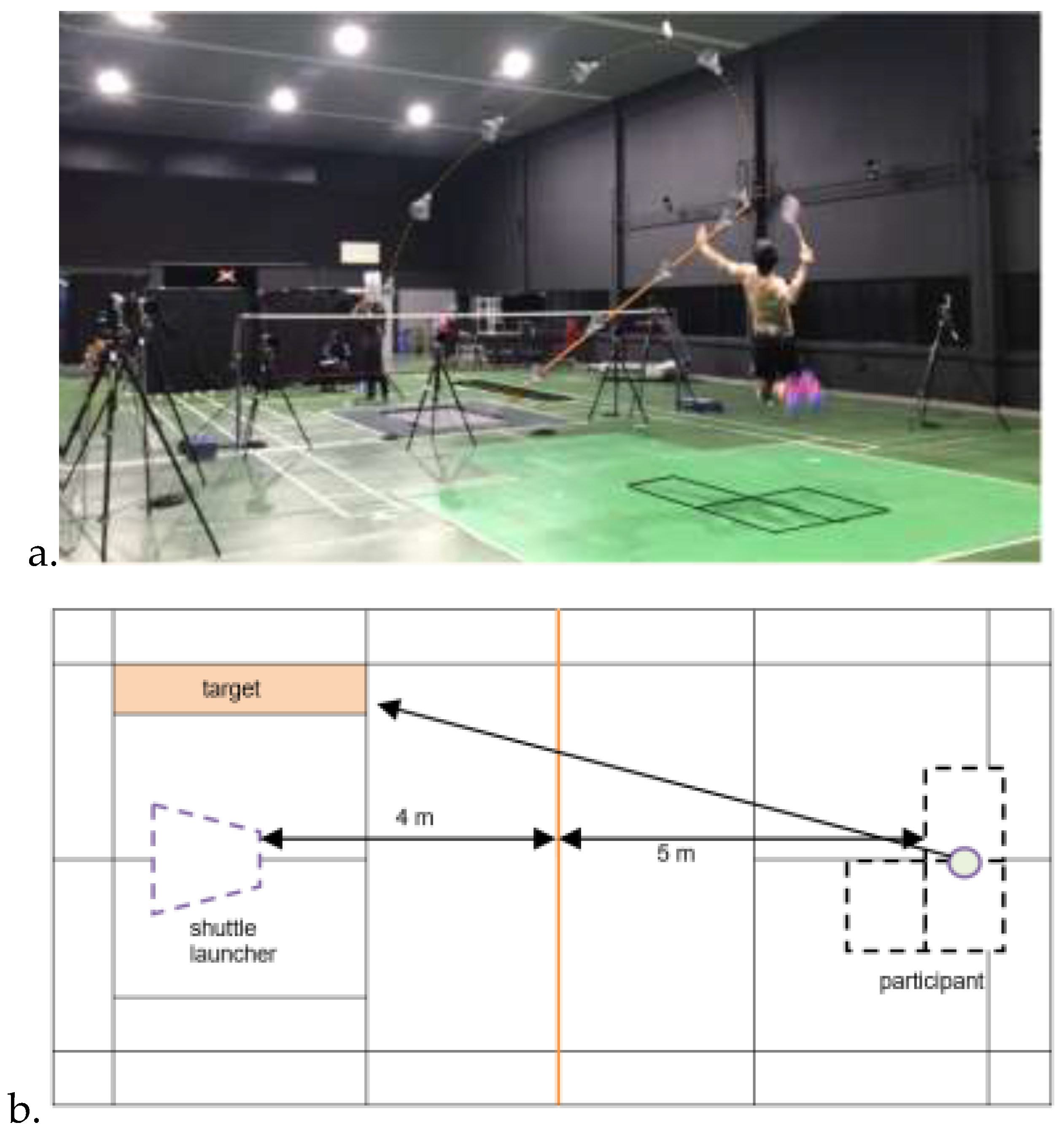

All data collections were conducted on an instrumented standard full-size badminton court at the Sports Biomechanics Laboratory in ISN under controlled conditions (

Figure 1a). The kinematics of each jump smash were recorded using 25 Oqus 7+ series infrared cameras (Qualisys AB 411 05, Goteborg, Sweden) at 700 Hz (

Figure 1a).

A total of sixty-two, 12.5 mm reflective markers were attached to key bony landmarks (

Figure 2a) using Qualisys double-sided and hypafix non-woven adhesive tape to create a 15-segment representation including head, thorax, pelvis, 2 x upper arm, 2 x forearm, 2 x hand, 2 x thigh, 2 x shank, and 2 x feet (Ramasamy et al., 2021) in Visual 3D v6.00.18 (C-Motion Inc., Germantown, USA). The definition of each segment was constructed by a local reference frame using a minimum of three markers on the segment based on the three axes (x: pointing to participants’ right; y: pointing forward; z: pointing from distal to proximal) as reported in a previous study (King et al., 2020). Each racket was equipped with one 12.5 mm marker at the bottom of the handle and eight pieces of 10 mm

2 retro-reflective tape on the racket head and shaft (

Figure 2b). New Yonex Aerosense 30 shuttlecocks were used for all data collections with a circle-reflective tape (diameter 19 mm) attached to the tip of the shuttlecock (

Figure 2c). Mis-shaped or broken shuttlecocks were discarded.

All participants were given approximately 20 minutes for warm-up and 15–30 minutes for court familiarisation before the data collection. During the data collection, high serves/ lifts were replicated using a Knight Trainer shuttle launcher (Black Knight, Canada) for the participants to perform their maximum jump smashes taking off and landing on a fixed area with both feet (

Figure 1b). Twenty-five maximum jump smashes aiming at a designated area on the opposite side of the court were performed by each participant. Trials that did not land in the designated area were excluded.

2.3. Data Reduction

The three fastest and three slowest jump smashes (identified by the post-impact shuttlecock speed) for each participant were categorised into FAST and SLOW conditions, respectively, for further analysis. Position data were labelled using Qualisys Track manager (QTM2021.2; build 4260, Qualisys, Goteburg, Sweden) and gaps within the data were filled using a combination of linear and polynomial interpolation. All body marker position data were filtered within Visual 3D using a low-pass Butterworth filter with a cut-off frequency of 60 Hz that was determined through a residual analysis (Winter, 2009) using MATLAB R2022a (The MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA).

A 15-segment model in Visual 3D was used to calculate kinematic parameters during the swing phase for each trial according to two key instants: (a) start, defined as the instant when racket head speed reached 5 m/s during backswing phase and did not subsequently drop below this threshold, and (b) shuttle-racket contact, defined by the frame where the anterior-posterior velocity of the shuttlecock changes from negative to positive (Ramasamy et al., 2022). Joint angles were calculated as Cardan angles (

Table 1), where an xyz rotation sequence was used (Worthington et al., 2013) for all angles except for the shoulder where a zyz rotation sequence was used (Wu et al., 2005) following the ISB recommendation, and thorax where a yxz rotation sequence was used (Mears et al., 2015)).

Post-impact shuttlecock speed, racket head speed, impact timing (swing time from the start of forward swing to racket-shuttlecock contact) and impact location were calculated using a curve-fitting methodology (Peploe et al., 2018), that was adapted for badminton (McErlain-Naylor et al., 2020) to include a 1 ms contact period (Cohen et al., 2015). Additionally, racket face angle relative to vertical at contact and shuttlecock angle post-impact relative to the horizontal were calculated (Li et al., 2016; Zhu, 2013).

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Technique Variables

Technique variables include the following kinematic parameters, namely the shoulder plane of elevation, elevation and rotation, elbow flexion/extension angle and angular velocity, and trunk angle data during the swing phase. All angle and angular velocity curves were time-normalised to the period start of forward swing to racket-shuttle contact. The reliability of each variable for both FAST and SLOW conditions were analysed using integrated pointwise indices (intra-class correlation, ICC) test.

2.4.2 Racket/Shuttlecock Variables

Post-impact shuttlecock speed, racket head speed, swing time and impact location (longitudinal and medio-lateral) relative to the racket-head centre were separated into FAST and SLOW conditions based on the post-impact shuttlecock speed.

2.4.3 Statistical Analysis

Integrated pointwise indices using the ICC (type: consistency) were calculated using variance components of an ANOVA based on a two-way mixed model (Schelin et al., 2021) with pointwise confidence intervals set to 95% supplemented at each time point to analyse the test-retest reliability for the curve data. The classification of ICCs according to (Cicchetti, 1994) were adapted for interpretation: (poor < 0.4, 0.4 ≤ fair < 0.6, 0.6 ≤ good ≤ 0.74 0.74 < excellent). Data were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test, where the assumption of normality was met p > 0.05. If high similarity within each participant’s condition (FAST vs SLOW) was found (indicated by a high ICC value), the three trials for each condition were averaged (mean) into two single time-histories to provide a representative time-history of the technique used during each condition. A within-measures ANOVA and statistical parametric mapping (SPM) were performed to assess any significant differences in the technique variables between conditions over the normalised swing phase. The significance threshold of alpha < 0.05 was set for ANOVA measurements, whilst a Bonferroni correction was used to adjust for post-hoc analysis. Paired T-tests were performed in order to detect differences between the racket / shuttlecock variables for each of the two conditions (FAST vs SLOW). Within-measures ANOVA using 1D-Statistical parametric mapping (1D-SPM) (Pataky, 2010) as performed in MATLAB R2022a (The MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA) and ICC test and paired t-test were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics 26 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

Overall, the ICC test revealed excellent similarities in all participant’s technique variables in both the FAST and SLOW conditions, identified by a high average ICC value of 0.983 ± 0.065 (mean ± SD). Hence, the three fastest and three slowest trials of each participant were combined into two single time-histories (FAST and SLOW) for each technique variable studied to represent the technique used when performing fast and slow smashes, respectively.

3.1. Technique Variables

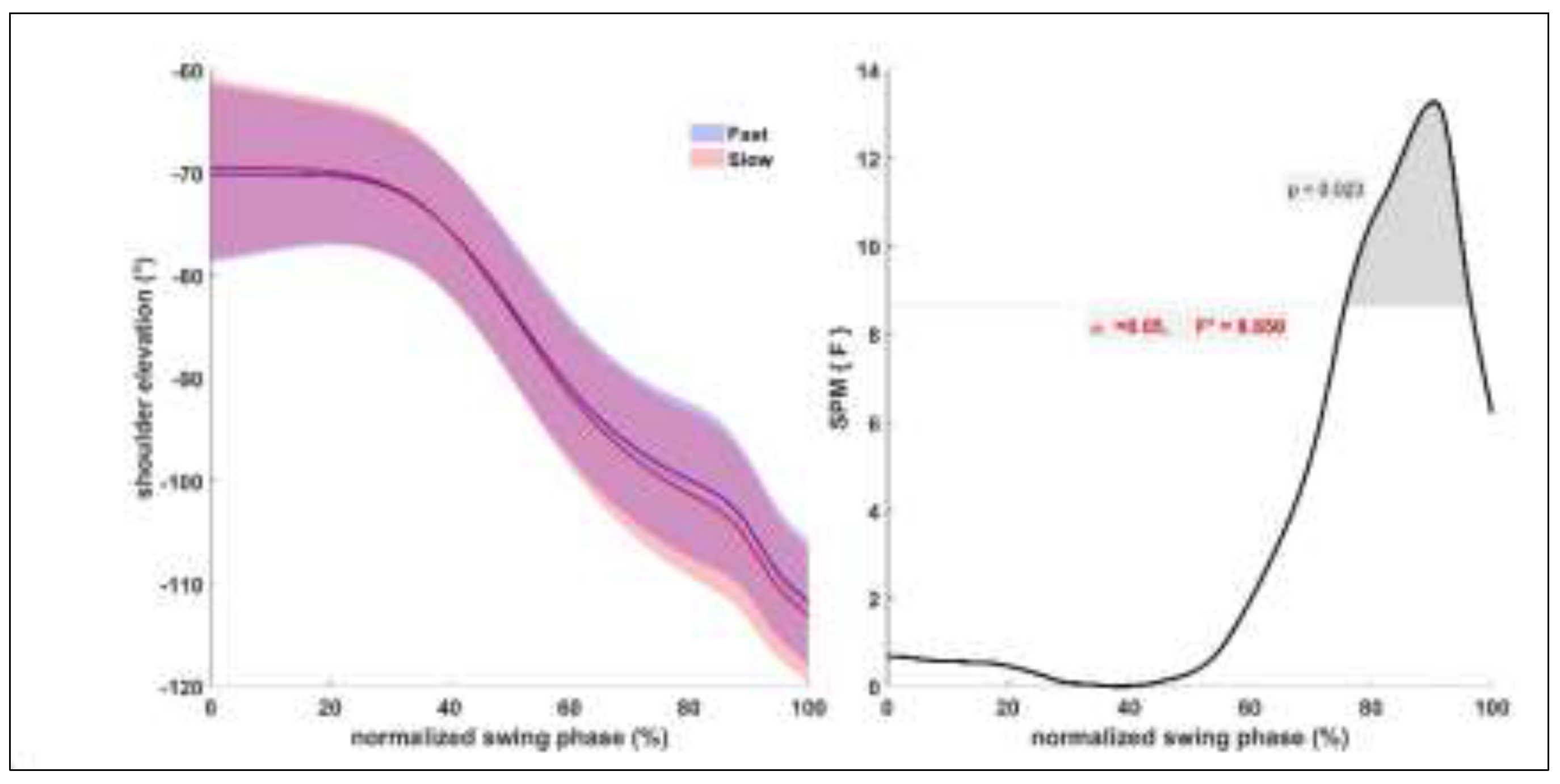

Of the five technical variables only the shoulder elevation angle was found to have significant differences between FAST and SLOW during the swing phase. There was a significant difference in the shoulder elevation angle from 75% to 95% (

Figure 3) of the forward swing between FAST and SLOW trials (p = 0.023), with players that were less elevated at the shoulder joint during FAST trials compared to their SLOW trials.

3.2. Racket/Shuttlecock Variables

The overall range of badminton smash speeds was 75.8 – 100.6 m⋅s

-1, with the largest variation for an individual being 13.4 m⋅s

-1 (13% difference) and the smallest difference for an individual being 3.3 m⋅s

-1 (3% difference). Across the 19 participants, significant differences were observed between the FAST and SLOW trials in post-impact shuttlecock speed (95.0 ± 3.6 m⋅s

-1 vs 85.8 ± 5.8 m⋅s

-1,

p < 0.001, racket head speed at contact (66.3 ± 3.4 m⋅s

-1 vs 64.3 ± 3.7 m⋅s

-1,

p < 0.0005) and longitudinal impact location (8.5 mm vs -2.6 mm, p = 0.027) (

Table 2). Interestingly, paired T-test also revealed that were significant differences in the swing duration and impact location between the FAST and SLOW trials. The swing duration during the FAST condition was on average 0.0036 s (3.6 ms) shorter than the SLOW trials (

p = 0.0012). Meanwhile, players in their SLOW trials were observed to demonstrate ‘worse’ impact locations, demonstrated by a greater absolute distance of the impact location from the geometric centre on average (13.41 mm;

p = 0.001) compared to their FAST trials.

Figure 3.

Shoulder elevation angle mean ± standard deviation (SD) for fast and slow condition on the left and ANOVA SPM (t) on the right.

Figure 3.

Shoulder elevation angle mean ± standard deviation (SD) for fast and slow condition on the left and ANOVA SPM (t) on the right.

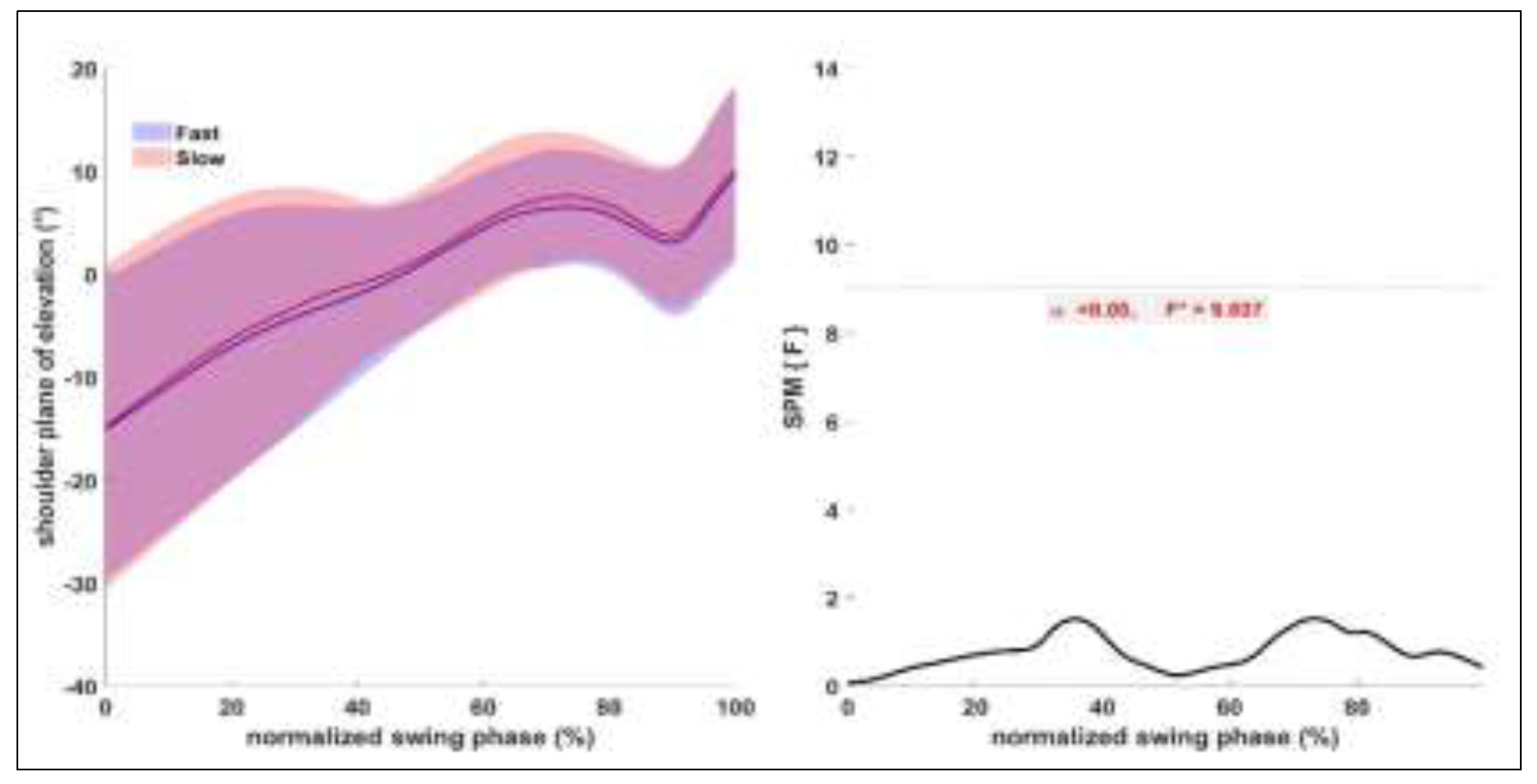

Figure 4.

Shoulder plane of elevation angle mean ± standard deviation (SD) for fast and slow condition on the left and ANOVA SPM (t) on the right.

Figure 4.

Shoulder plane of elevation angle mean ± standard deviation (SD) for fast and slow condition on the left and ANOVA SPM (t) on the right.

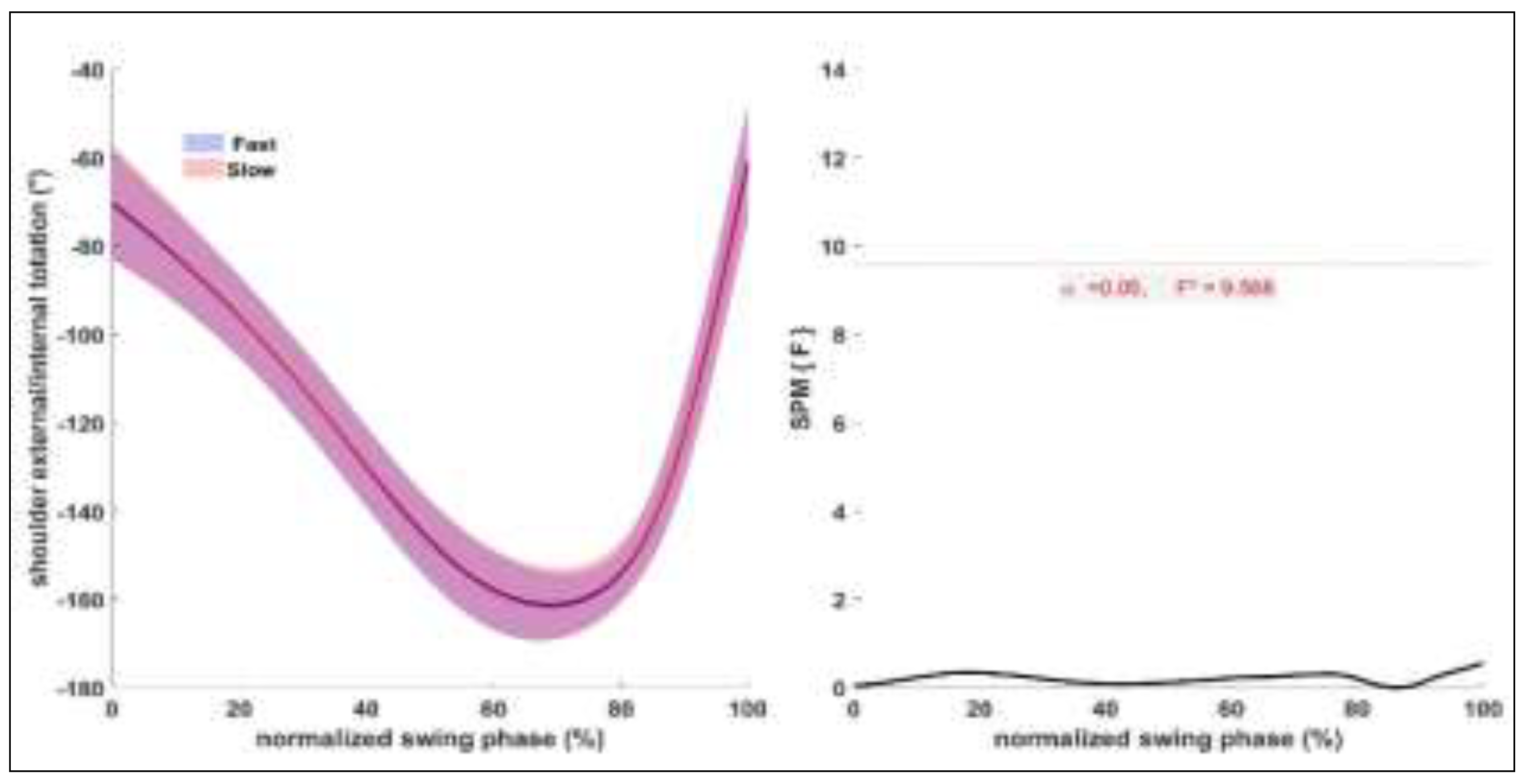

Figure 5.

Shoulder internal and external rotation angle mean ± standard deviation (SD) for fast and slow condition on the left and ANOVA SPM (t) on the right.

Figure 5.

Shoulder internal and external rotation angle mean ± standard deviation (SD) for fast and slow condition on the left and ANOVA SPM (t) on the right.

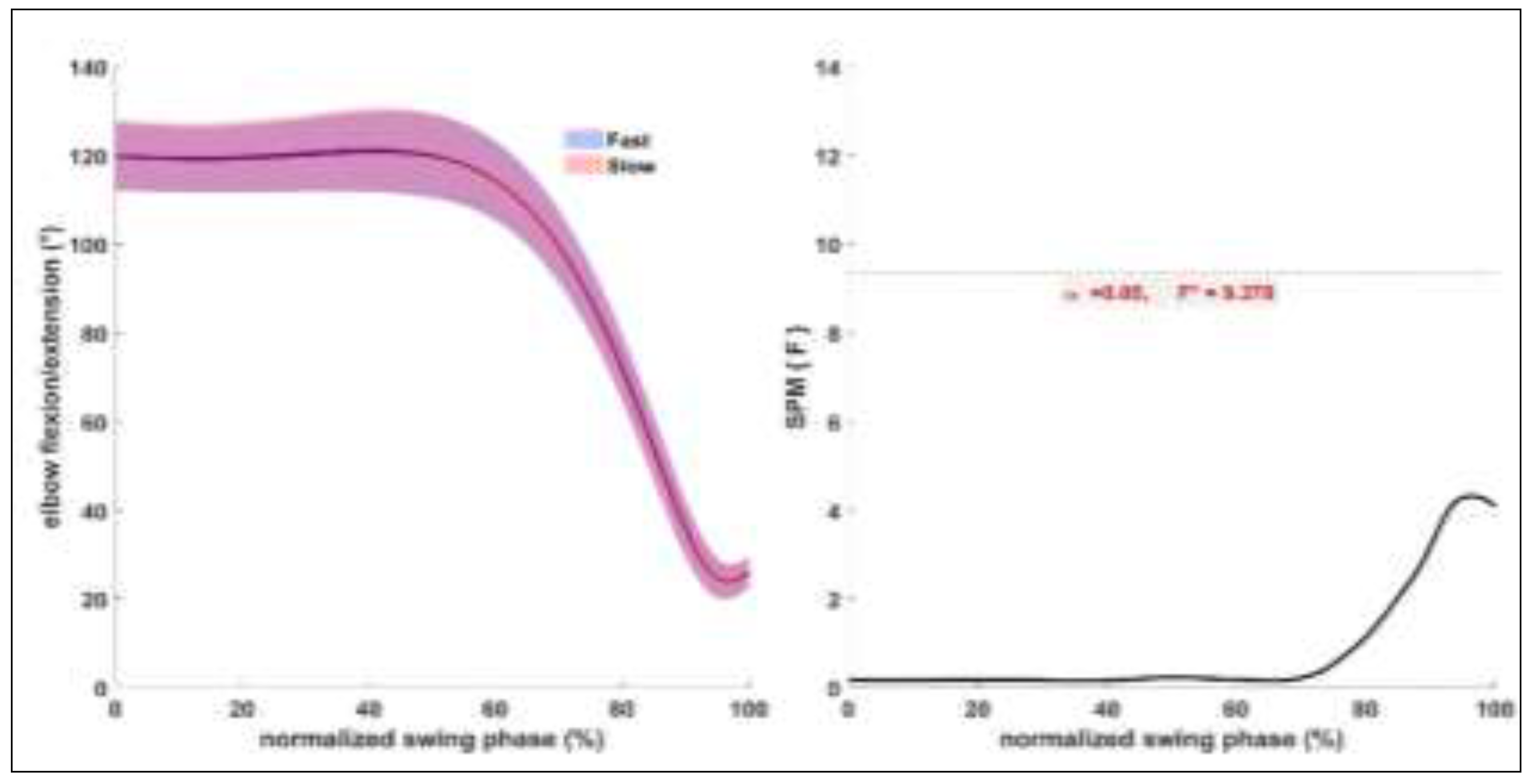

Figure 6.

Elbow flexion extension angle mean ± standard deviation (SD) for fast and slow condition on the left and ANOVA SPM (t) on the right.

Figure 6.

Elbow flexion extension angle mean ± standard deviation (SD) for fast and slow condition on the left and ANOVA SPM (t) on the right.

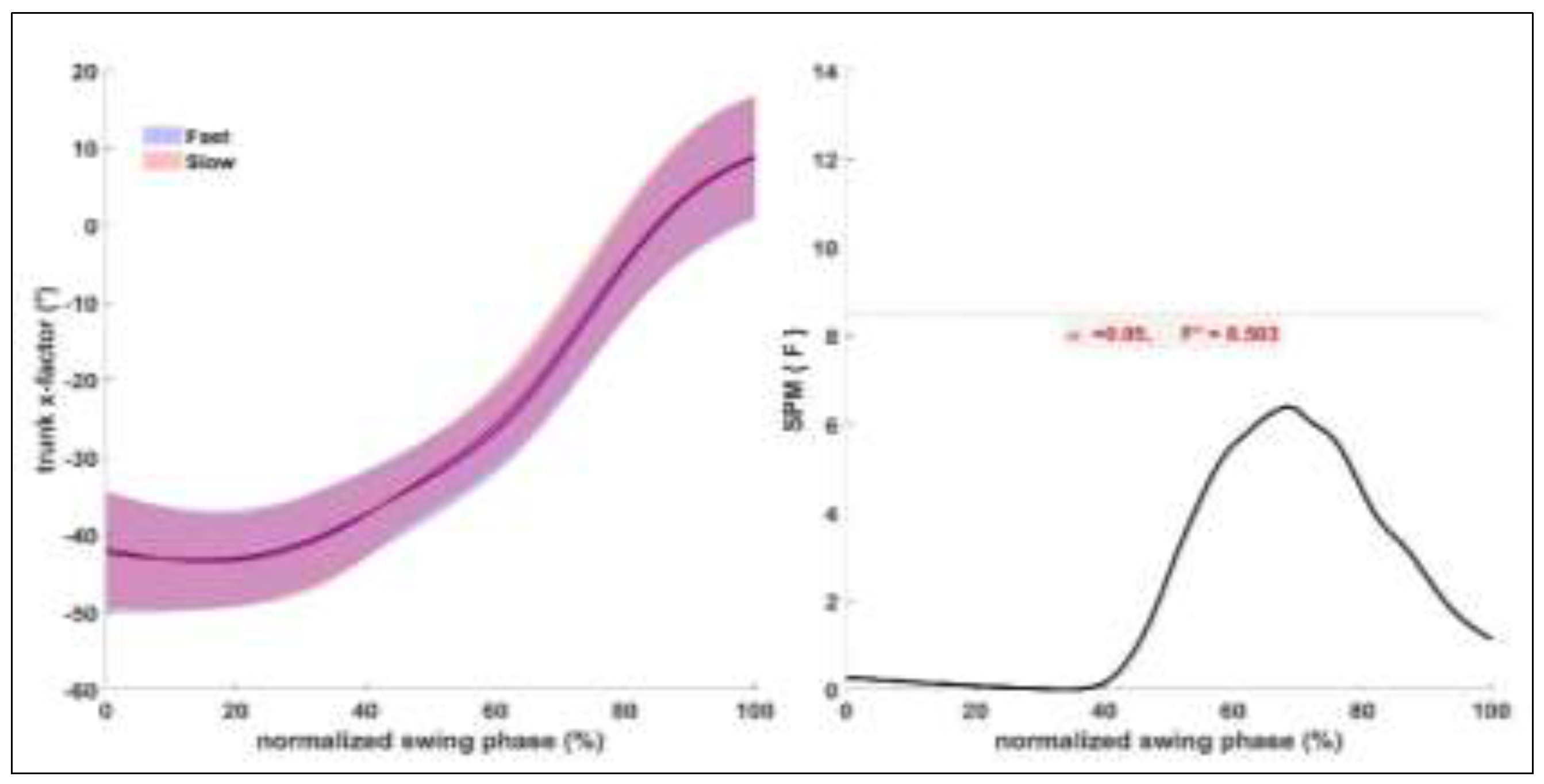

Figure 7.

Trunk x factor angle mean ± standard deviation (SD) for fast and slow condition on the left and ANOVA SPM (t) on the right.

Figure 7.

Trunk x factor angle mean ± standard deviation (SD) for fast and slow condition on the left and ANOVA SPM (t) on the right.

4. Discussion

The intra-individual variation in shuttlecock smash speed across the 25 trials for each participant varied from 3.3 – 13.4 m⋅s-1 with significant differences between the FAST and SLOW groups for both post-impact shuttlecock speed and racket head speed. A maximum difference of 3.3 m⋅s-1 (3%) across 25 trials could be considered a small difference and perhaps what might be expected for elite players, but 13.4 m⋅s-1 (13%) is over three times as much and for an elite player is perhaps surprising. This drop of 13% would bring an ‘elite’ player in line with ‘regional’ level players, based on data from King et al. (2020) where elite players achieved similar shuttlecock speeds of 94.6 m⋅s-1 whilst regional players achieved 84.6 m⋅s-1.

A comparison of technique and racket / shuttlecock variables revealed several important differences between the FAST and SLOW conditions. Unsurprisingly, significant differences existed between FAST and SLOW conditions for post-impact shuttlecock speed and racket head speed, respectively, given the high correlation between the two variables (r = 0.90; King et al., 2020).

Overall participants performed smashes with greater longitudinal impact locations (11 mm closer to the racket tip) in the FAST group compared to the SLOW group. It is not obvious why this difference in impact location occurred across a group of elite players, but it could indicate that coordinating the timing of the racket shuttle impact was challenging even for elite players. Having an impact location closer to the tip of the racket does result in a faster speed of the racket at the point of impact on the racket and therefore it makes sense that the fastest shuttlecock speeds came from impacts slightly closer to the tip of the racket. There would become a point at which an increase in longitudinal impact location would cause a reduction in shuttlecock speed due to the impact efficiency between the stringbed and shuttlecock. The mean longitudinal and mediolateral impact location during the FAST condition were similar to the ‘optimal’ impact location reported by (McErlain-Naylor et al., 2020), 8.5 vs. 11.6 mm and -15.3 vs. -5.7 mm, respectively.

The ‘impact quality’ may also be related to the significant difference in swing duration, where players performed on average 3.6 ms shorter swing durations during the FAST conditions. The small amount of extra time during the SLOW condition swings perhaps allowed the shuttle more time to drop and thus produce impact locations lower on the racket head and further away from optimal (McErlain-Naylor et al., 2020).

The technique of participants during FAST and SLOW conditions did not vary substantially with only one upper-body joint angle different between FAST and SLOW conditions, namely the shoulder elevation angle between 75-95% of the swing phase. Players held their arm in less elevated position during the FAST trials compared to SLOW trials and this is supported by Ramasamy et al. (2021), where the arm is placed on a more favourable position to generate greater shoulder internal rotation angular velocities. Given the ability level of the participants, it was unlikely that their technique would differ between the two conditions. Whilst the technique (joint kinematics) at the various joints were similar between conditions, and therefore overall ranges of motion, they were completed over shorter periods of time during the FAST condition implying greater angular velocities and thus greater racket head speeds transferring more momentum to the shuttlecock (assuming an equivalent impact efficiency).

Previous studies have found shoulder internal rotation at contact to be an important technique variable, with a more internally rotated shoulder linked to greater shuttlecock speed (King et al., 2020, Ramasamy et al., 2021). Similarly, players who achieve a more counter-rotated trunk position at the end of the backswing phase achieved greater shuttlecock speeds (King et al., 2020; Ramasamy et al., 2021). Neither of these technique variables showed any differences between FAST and SLOW conditions when assessing intra-individual variation throughout the entire swing phase. These results suggest that players changing their technique is unlikely to be the cause of variation in shuttlecock speed, and instead successfully executing and timing their technique to ensure an efficient impact is likely to explain this variation in shuttlecock speed.

Future work should investigate technique differences with non-elite populations, or different age groups, as well as longitudinal studies to see what technique changes are made as players progress through various stages and performance groups, thereby highlighting which technique factors are important for consistently developing greater racket head speed and shuttlecock smash speed. It is also likely that players of a lower standard have more variability in their technique allowing a greater understanding of what technique factors cause a reduction in shuttlecock speed.

In conclusion, for elite players, the differences in shuttlecock speeds between smash and slow strokes is likely to be caused by racket / shuttlecock variables and not specific changes in technique, particularly more distal longitudinal impact locations within sensible limits where impact efficiency is not significantly impacted and completing the swing phase over a shorter period of time thereby generating greater racket head speeds.

5. Limitations

The study design differentiated between FAST and SLOW smash conditions, rather than assigning athletes to distinct groups. This choice may not fully encapsulate motor control or technical variability across different performance levels or fatigue states. Specifically, the lack of differentiation between unfatigued and fatigued states raises concerns about whether repeated smashes (25 in total) induced fatigue, potentially confounding the observed biomechanical parameters under the FAST vs. SLOW categorisation. Consequently, some of the variation noted could be attributable to factors beyond the designated conditions, such as muscular fatigue.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

In summary, this study presents preliminary insights into biomechanical differences in badminton smashes under FAST and SLOW conditions, providing an initial step toward understanding movement variability and performance in sport-specific contexts. Despite the limitations, the findings highlight the importance of nuanced analysis methods in biomechanical studies, particularly in complex, high-performance movements such as the badminton smash. However, more sophisticated design and analysis choices may be necessary to capture the full scope of motor control mechanisms underlying elite badminton techniques, especially when addressing intra-individual variations and compensatory joint mechanics. Additionally, from a tactical perspective, it may also be relevant to create conditions where players have a particular focus on generating maximum shuttlecock speed vs. accuracy, and evaluate what technique factors change in the likely scenario that players reduce racket head speed and shuttlecock speed to increase the smash accuracy.

Future studies should consider incorporating fatigue assessments to better understand its impact on smash performance. This might involve controlled comparisons of fatigued versus unfatigued states to provide a clearer interpretation of FAST vs. SLOW conditions and their potential effects on biomechanics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.R., Y.M.W., H.T., M.K. writing—original draft preparation, Y.R.; writing—review and editing, Y.R., Y.M.W., H.T., M.K.; supervision, Y.R., H.T., M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received internal funding from the National Sports Institute of Malaysia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of National Sports Institute of Malaysia.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express special thanks to Badminton Association of Malaysia for the support throughout this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abian-vicen, J., Castanedo, A., Abian, P., Sampedro, J., Abian-vicen, J., Castanedo, A., Abian, P., & Sampedro, J. (2017). Temporal and notational comparison of badminton matches between men’s singles and women ’ s singles. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 8668(June). [CrossRef]

- Cicchetti, D. V. (1994). Guidelines, Criteria, and Rules of Thumb for Evaluating Normed and Standardized Assessment Instruments in Psychology. In Psychological Assessment (Issue 4).

- Cohen, C., Texier, B. D., Quéré, D., & Clanet, C. (2015). The physics of badminton. New Journal of Physics, 17(6). [CrossRef]

- Dutton, M., Gray, J., Prins, D., Divekar, N., & Tam, N. (2020). Overhead throwing in cricketers: A biomechanical description and playing level considerations. Journal of Sports Sciences, 38(10), 1096–1104. [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, P. X., Menzel, H. J. K., Guidotti, F., Bell, J., von Duvillard, S. P., & Wagner, H. (2019). Spike jump biomechanics in male versus female elite volleyball players. Journal of Sports Sciences, 37(21), 2411–2419. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, B. J. (2006). Contributions of joint rotations to racquet speed in the tennis serve. Journal of Sports Sciences, 24(January), 31–49. [CrossRef]

- King, M., Towler, H., Dillon, R., & McErlain-Naylor, S. (2020). A correlational analysis of shuttlecock speed kinematic determinants in the badminton jump smash. Applied Sciences (Switzerland), 10(4). [CrossRef]

- Koike, S., & Hashiguchi, T. (2014). Dynamic contribution analysis of badminton-smash-motion with consideration of racket shaft deformation (A model consisted of racket-side upper limb and a racket). Procedia Engineering, 72, 496–501. [CrossRef]

- Li, S., Zhang, Z., Wan, B., Wilde, B., & Shan, G. (2016). The relevance of body positioning and its training effect on badminton smash. Journal of Sports Sciences, 35(4), 310–316. [CrossRef]

- McErlain-Naylor, S. A., Towler, H., Afzal, I. A., Felton, P. J., Hiley, M. J., & King, M. A. (2020). Effect of racket-shuttlecock impact location on shot outcome for badminton smashes by elite players. Journal of Sports Sciences, 38(21), 2471–2478. [CrossRef]

- Mears, A., Roberts, J., Wallace, E., Kong, P. W., & Forrester, S. E. (2015). Comparison of two- andthree-dimensional methods for analysis of trunk kinematic variables in the golf swing. Journal of Applied Biomechanics, 32(1), 23–31. [CrossRef]

- Applied Biomechanics, 32(1), 23–31. [CrossRef]

- Pataky, T. C. (2010). Generalized n-dimensional biomechanical field analysis using statistical parametric mapping. Journal of Biomechanics, 43(10), 1976–1982. [CrossRef]

- Peploe, C., McErlain-Naylor, S. A., Harland, A. R., & King, M. A. (2018). The relationships between impact location and post-impact ball speed, bat torsion, and ball direction in cricket batting. Journal of Sports Sciences, 36(12), 1407–1414. [CrossRef]

- Phomsoupha, M., & Laffaye, G. (2014). The Science of Badminton : Game Characteristics , Anthropometry , Physiology , Visual Fitness and Biomechanics. Sports Medicine, 45(4), 473–495. [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, Y., Sundar, V., Towler, H., Usman, J., & King, M. A. (2021). Kinetic and kinematic determinants of shuttlecock speed in the forehand jump smash performed by elite male Malaysian badminton players. Sports Biomechanics, 00(00), 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, Y., Sundar, V., Usman, J., Towler, H., King, M. A., & Razman, |Rizal. (2022). Relationships between Racket Arm Joint Moments and Racket Head Speed during the Badminton Jump Smash Performed by Elite Male Malaysian Players. Journal of Applied Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Rusdiana, A., Bin Abdullah, M. R., Syahid, A. M., Haryono, T., & Kurniawan, T. (2021). Badminton overhead backhand and forehand smashes: A biomechanical analysis approach. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 21(4), 1722–1727. [CrossRef]

- Rusdiana, A., Ruhayati, Y., Korea, S., & Korea, S. (2016). 3D Kinematic Analysis of Standing and Jumping Smash Technique of Indonesian Badminton. 96(8), 2525–2535.

- Sarvestan, J., zdenek, svoboda, Fatemeh, A., & frankly, mulloy. (2021). Analysis of Whole-Body Coordination Patterning in Successful and Faulty Spikes Using Self-Organising Map-Based Cluster Analysis: A Secondary Analysis. Measurement: Sensors, 21(1345). [CrossRef]

- Schelin, L., Pini, A., Markström, J. L., & Häger, C. K. (2021). Test-retest reliability of entire time-series data from hip, knee and ankle kinematics and kinetics during one-leg hops for distance: Analyses using integrated pointwise indices. Journal of Biomechanics, 124(June). [CrossRef]

- Seminati, E., Marzari, A., Vacondio, O., & Minetti, A. E. (2015). Shoulder 3D range of motion and humerus rotation in two volleyball spike techniques: injury prevention and performance. Sports Biomechanics, 14(2), 216–231. [CrossRef]

- Serrien, B., Clijsen, R., Blondeel, J., Goossens, M., & Baeyens, J.-P. (2015). Differences in ball speed and three-dimensional kinematics between male and female handball players during a standing throw with run-up. BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation, 7(1). [CrossRef]

- Serrien, B., Ooijen, J., Goossens, M., & Baeyens, J.-P. (2016). A Motion Analysis in the Volleyball Spike - Part 1: Three-dimensional Kinematics and Performance. International Journal of Human Movement and Sports Sciences, 4(4), 70–82. [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. C., Roberts, J. R., Wallace, E. S., Kong, P., & Forrester, S. E. (2016). Comparison of two- and three-dimensional methods for analysis of trunk kinematic variables in the golf swing. Journal of Applied Biomechanics, 32(1), 23–31. [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, S., & Ito, A. (2007). A three-dimensional analysis of the contributions of upper limb joint movements to horizontal racket head velocity at ball impact during tennis serving. Sports Biomechanics, December 2014, 37–41. [CrossRef]

- Teu, K. K., Kim, W., Tan, J., & Fuss, F. K. (2005). Using dual Euler angles for the analysis of arm movement during the badminton smash. Sports Engineering, 8(3), 171–178. [CrossRef]

- Towler, H., Mitchell, S. R., & King, M. A. (2023). Effects of racket moment of inertia on racket head speed, impact location and shuttlecock speed during the badminton smash. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Worthington, P. J., King, M. A., & Ranson, C. A. (2013). Relationships between fast bowling technique and ball release speed in cricket. Journal of Applied Biomechanics, 29(1), 78–84. [CrossRef]

- Wu, G., Van Der Helm, F. C. T., Veeger, H. E. J., Makhsous, M., Van Roy, P., Anglin, C., Nagels, J., Karduna, A. R., McQuade, K., Wang, X., Werner, F. W., & Buchholz, B. (2005). ISB recommendation on definitions of joint coordinate systems of various joints for the reporting of human joint motion - Part II: Shoulder, elbow, wrist and hand. Journal of Biomechanics, 38(5), 981–992. [CrossRef]

- 31. Xiang Liu, Wangdo Kim, J. T. (2002). An Analysis of the Biomechanics of Arm Movement During a Badminton Smash (Vol. 1).

- Zhang, Z., Li, S., Wan, B., Visentin, P., Jiang, Q., Dyck, M., Li, H., & Shan, G. (2016). The Influence of X-Factor (Trunk Rotation) and Experience on the Quality of the Badminton Forehand Smash. Journal of Human Kinetics, 53(1), 9–22. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., & Sc, B. (2012). The Influence Of Body Positioning, Trunk Rotation (X-Factor) And Training Effect On Quality Of The Badminton Forehand Overhead Smash.

- Zhu, Q. (2013). Expertise of using striking techniques for power stroke in badminton. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 117(2), 427–441. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).