Submitted:

03 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

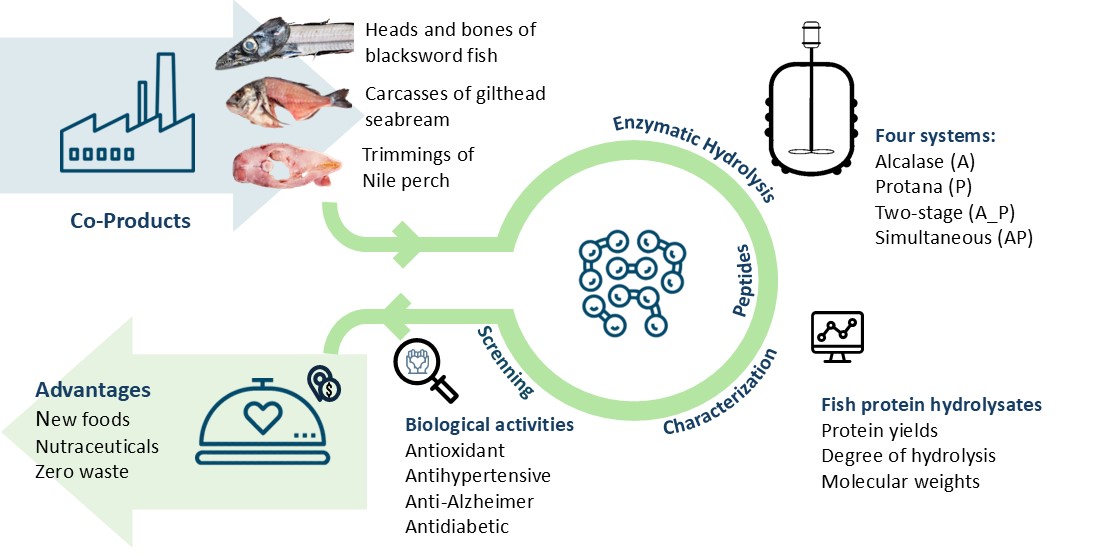

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Hydrolysis Process and FPH Characterization

2.1.1. Characterization of Co-Products and FPH - Proximate Composition

2.1.2. Evolution of Degree of Hydrolysis and Yields

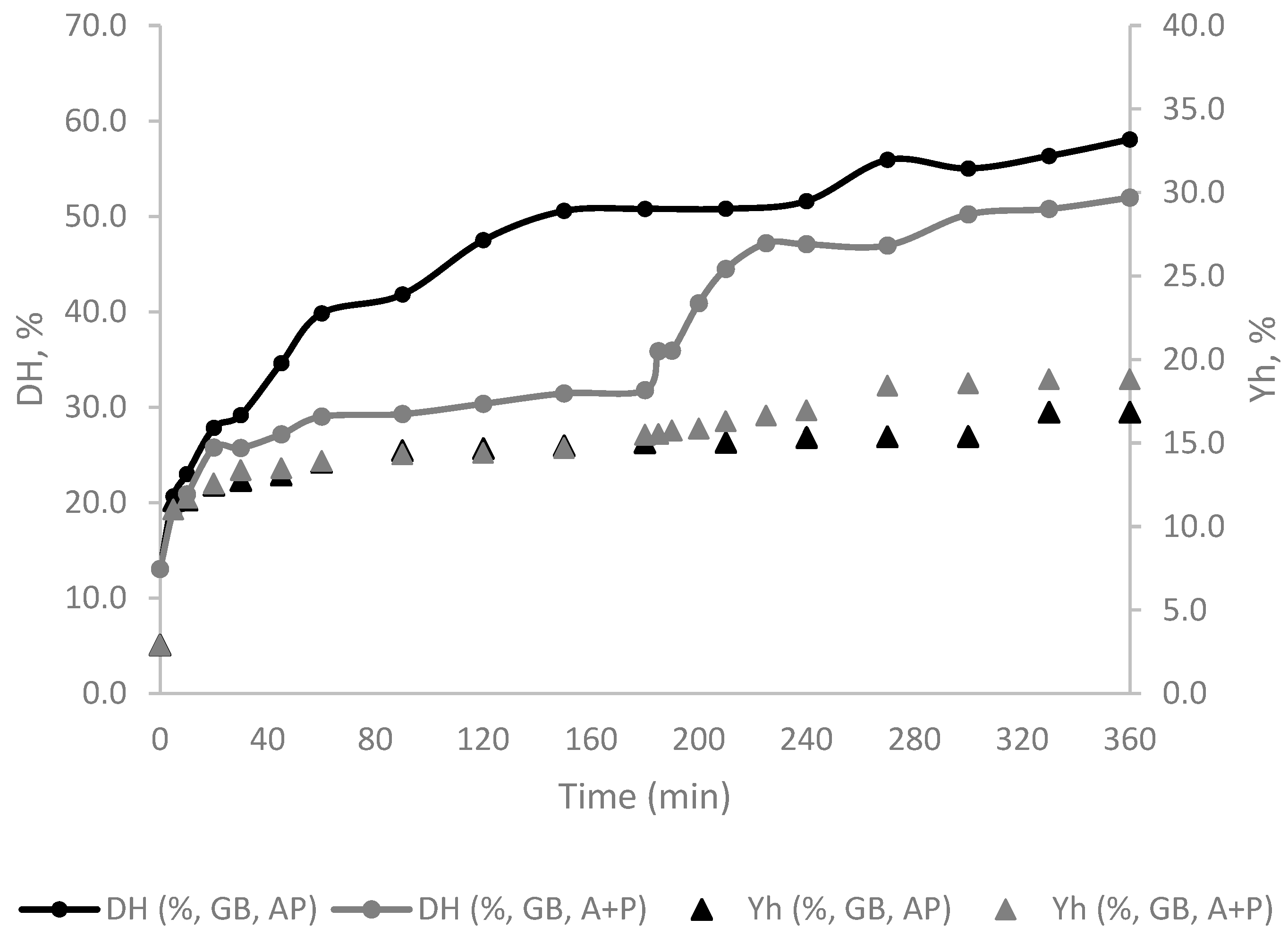

2.1.3. Molecular Weight

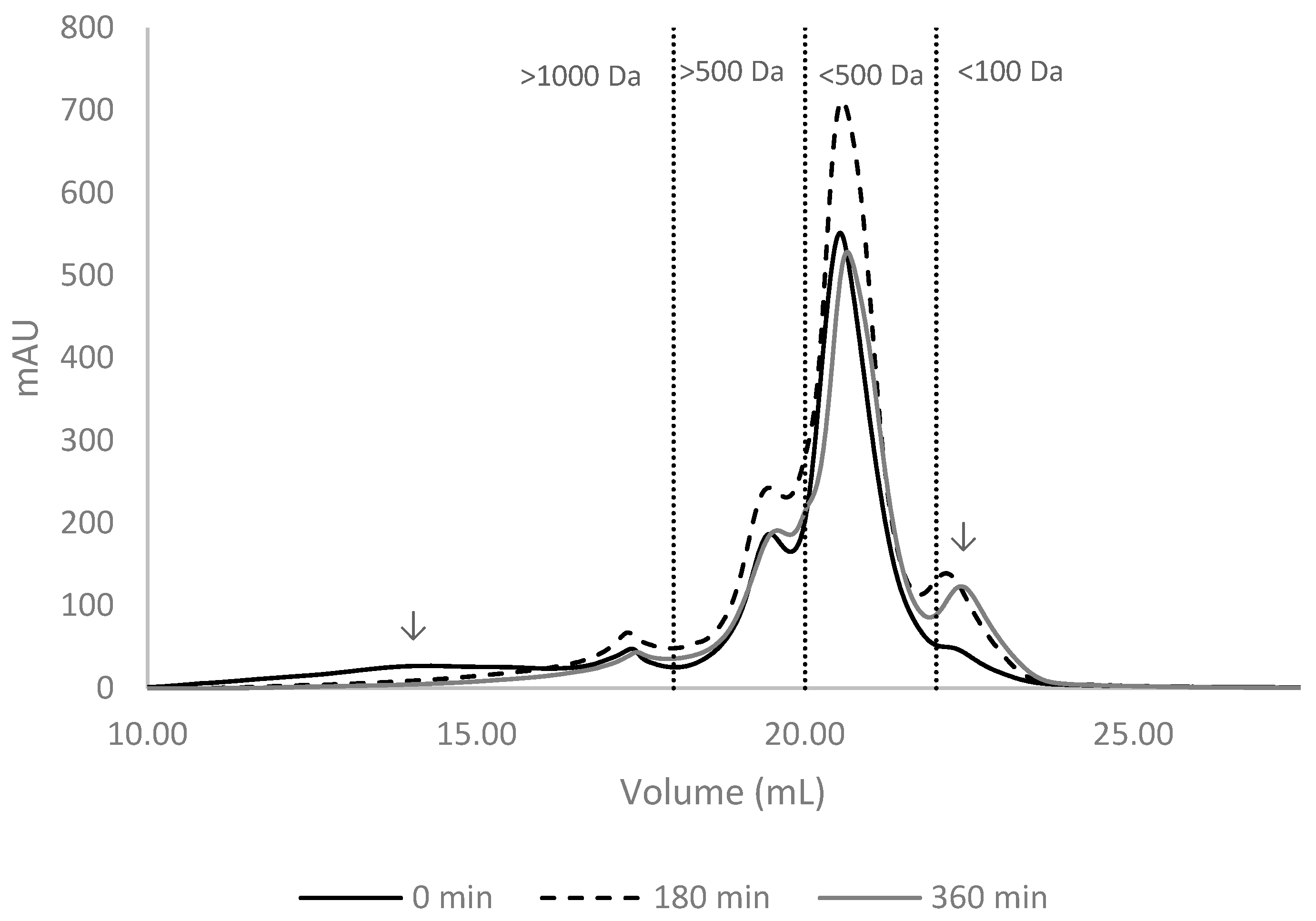

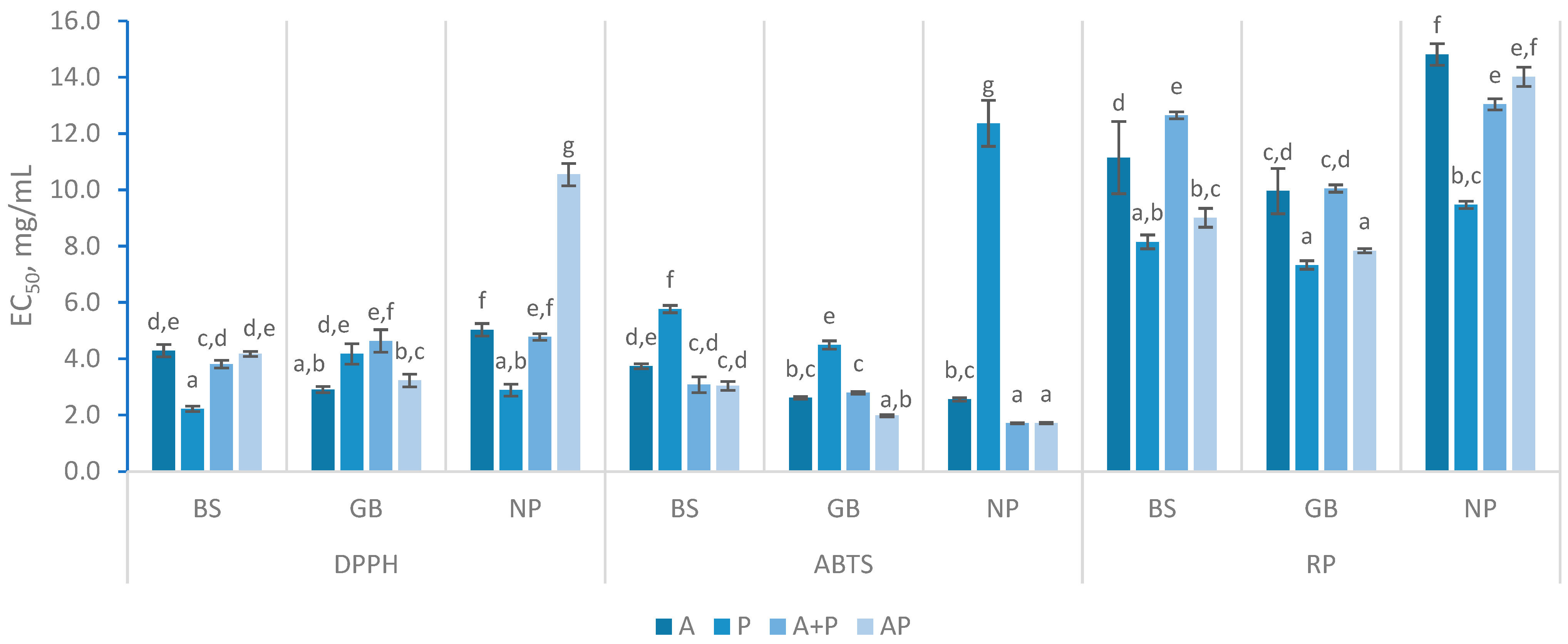

2.2. Antioxidant Activity

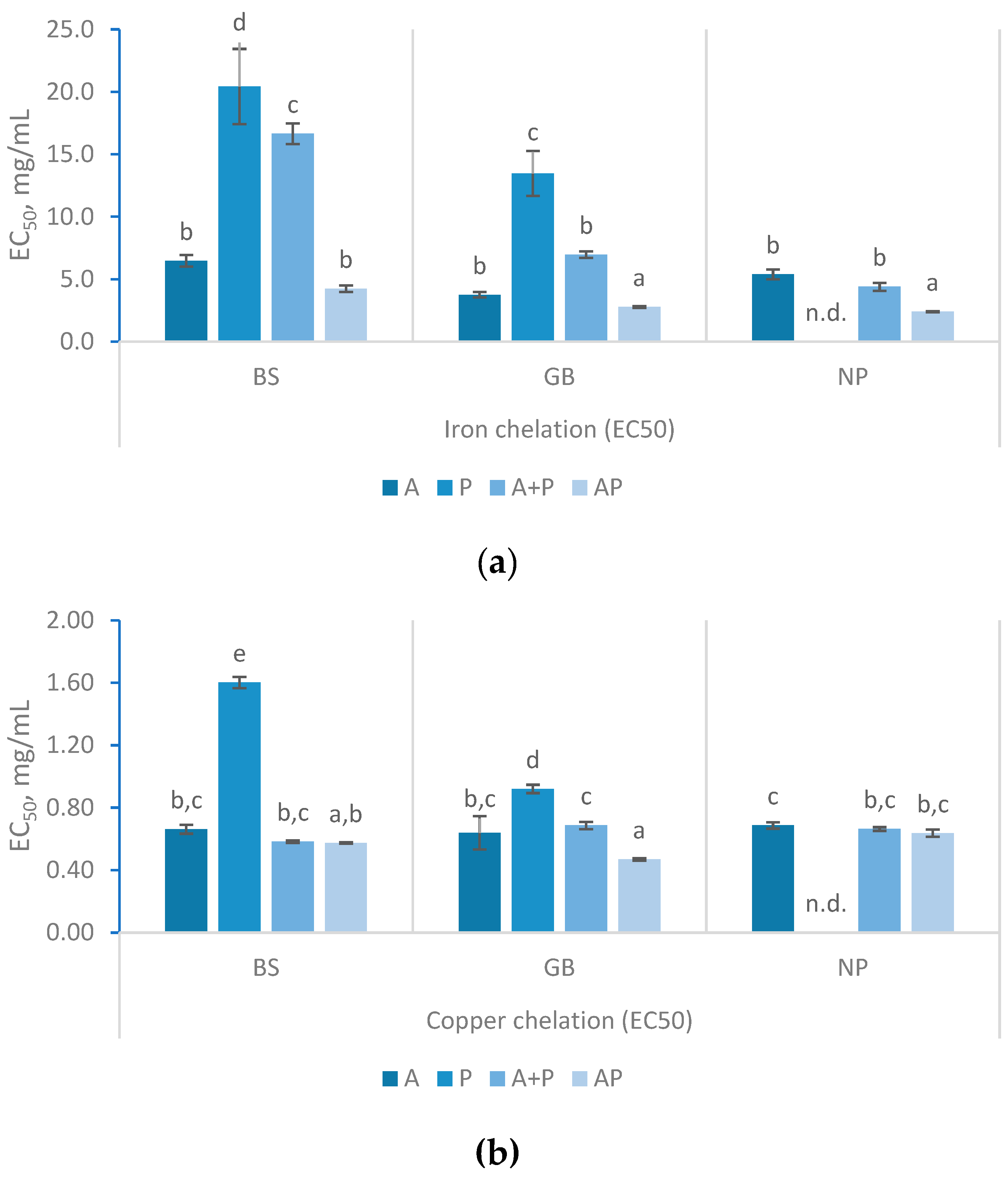

2.3. Metal Chelating Activities

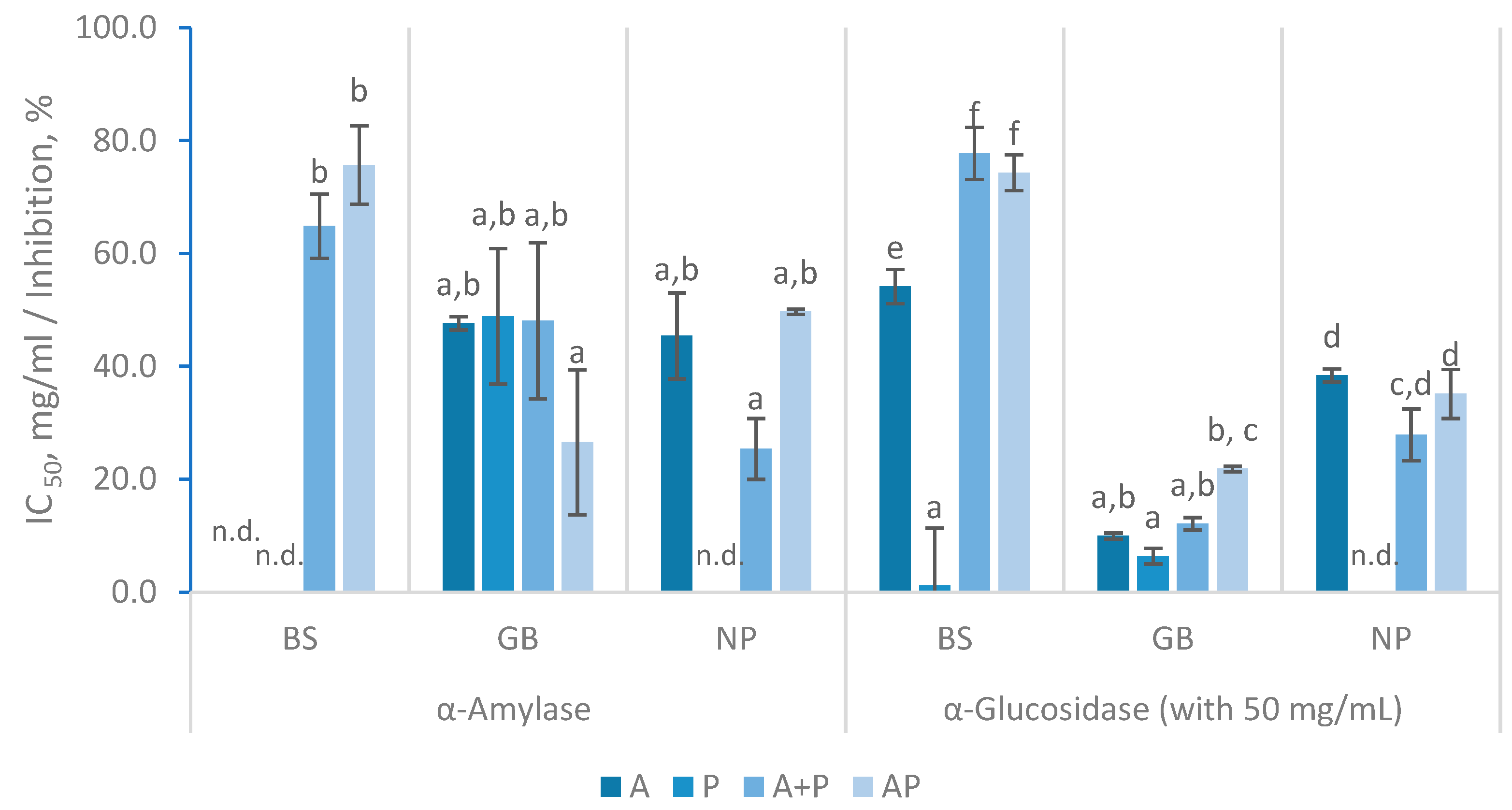

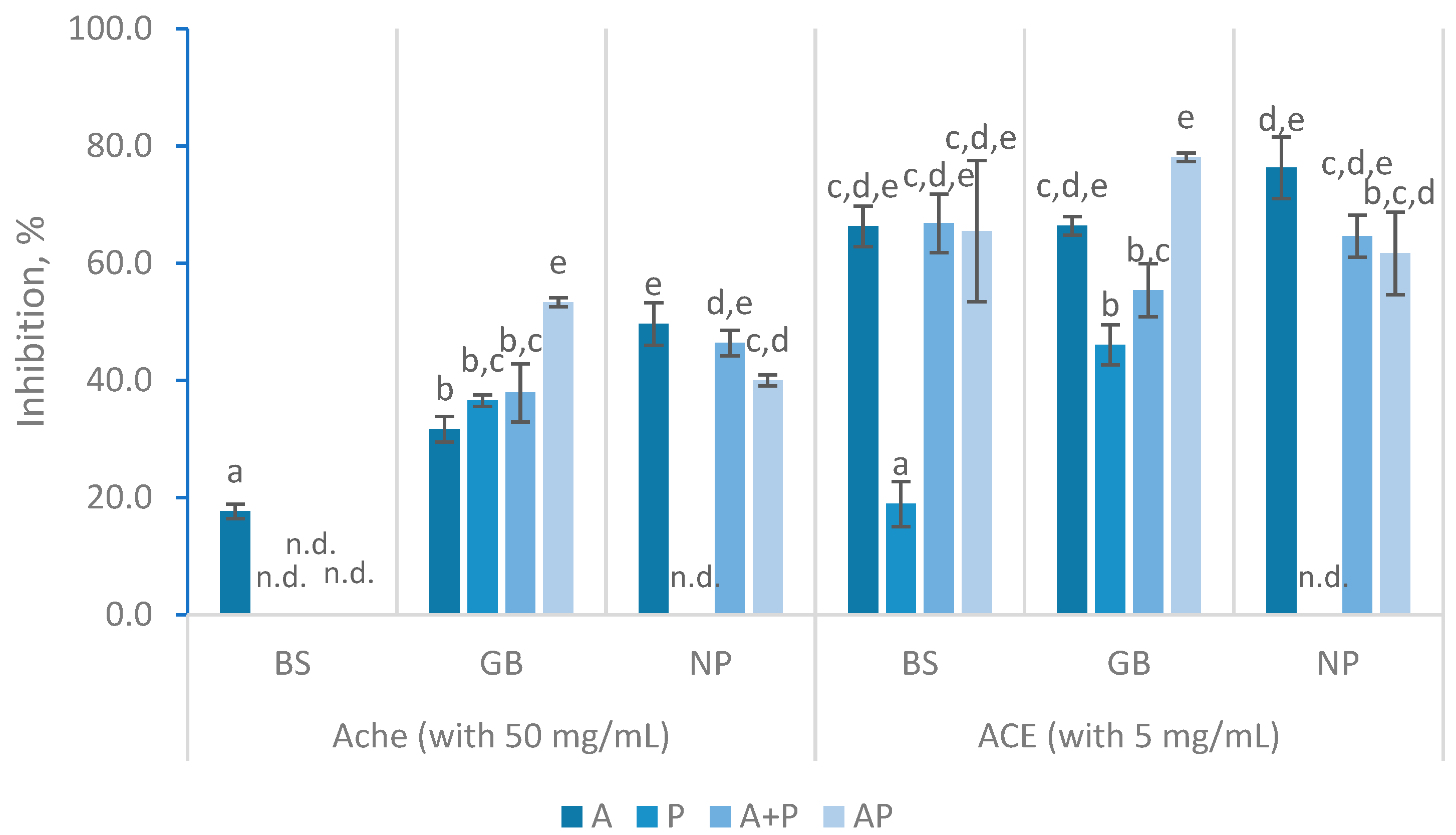

2.4. Biological Activities

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Raw Materials

3.2. Chemicals and Reagents

3.3. Proximate Composition

3.4. Enzymatic Hydrolysis

3.5. Fish Protein Hydrolysates Characterization

3.5.1. Yields

3.5.2. Degree of Hydrolysis (DH)

3.5.3. Molecular Weight Distribution (MWD)

3.6. Determination of Antioxidant Activity

3.6.1. DPPH• Radical Scavenging Activity

3.6.2. ABTS•+ Radical Scavenging Activity

3.6.3. Reducing Power (RP)

3.7. Metal Chelating Activities

3.7.1. Cu2+ Chelating Activity

3.7.2. Fe2+ Chelation Activity

3.8. Determination of Biological Activity

3.8.3. Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) Inhibitory Activity

3.8.4. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitory Activity

3.9. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024; FAO: Rome, 2024; ISBN 978-92-5-138763-4. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, K.; Watson, A.W.; Lonnie, M.; Peeters, W.M.; Oonincx, D.; Tsoutsoura, N.; Simon-Miquel, G.; Szepe, K.; Cochetel, N.; Pearson, A.G.; et al. Meeting the Global Protein Supply Requirements of a Growing and Ageing Population. Eur J Nutr 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ideia, P.; Pinto, J.; Ferreira, R.; Figueiredo, L.; Spínola, · Vítor; Castilho, P.C. Fish Processing Industry Residues: A Review of Valuable Products Extraction and Characterization Methods Statement of Novelty. Waste Biomass Valorization 2020, 11, 3223–3246. [CrossRef]

- IFFO By-Product. Available online: https://www.iffo.com/product (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- Lorenzo, J.M.; Barba, F.J. Advances in Food and Nutrition Research; 1st ed.; Academic Press, 2020; Vol. 92;

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation Towards the Circular Economy Vol. 1: An Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition; 2013; Vol. 1;

- European Union Regulation (EC) No 1069/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council. Official Journal of the European Union 2009.

- Pires, C.; Leitão, M.; Sapatinha, M.; Gonçalves, A.; Oliveira, H.; Nunes, M.L.; Teixeira, B.; Mendes, R.; Camacho, C.; Machado, M.; et al. Protein Hydrolysates from Salmon Heads and Cape Hake By-Products: Comparing Enzymatic Method with Subcritical Water Extraction on Bioactivity Properties. Foods 2024, 13, 2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddik, M.A.B.; Howieson, J.; Fotedar, R.; Partridge, G.J. Enzymatic Fish Protein Hydrolysates in Finfish Aquaculture: A Review. Rev Aquac 2021, 13, 406–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora-Sillero, J.; Ramos, P.; Monserrat, J.M.; Prentice, C. Evaluation of the Antioxidant Activity In Vitro and in Hippocampal HT-22 Cells System of Protein Hydrolysates of Common Carp (Cyprinus Carpio) By-Product. Journal of Aquatic Food Product Technology 2018, 27, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, V. Enzymes from Seafood Processing Waste and Their Applications in Seafood Processing. In; 2016; pp. 47–69.

- Kristinsson, H.G.; Rasco, B.A. Fish Protein Hydrolysates: Production, Biochemical, and Functional Properties. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2000, 40, 43–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iñarra, B.; Bald, C.; Gutierrez, M.; San Martin, D.; Zufía, J.; Ibarruri, J. Production of Bioactive Peptides from Hake By-Catches: Optimization and Scale-Up of Enzymatic Hydrolysis Process. Mar Drugs 2023, 21, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunsakul, K.; Laokuldilok, T.; Sakdatorn, V.; Klangpetch, W.; Brennan, C.S.; Utama-ang, N. Optimization of Enzymatic Hydrolysis by Alcalase and Flavourzyme to Enhance the Antioxidant Properties of Jasmine Rice Bran Protein Hydrolysate. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 12582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez Fuentes, L.; Richard, C.; Chen, L. Sequential Alcalase and Flavourzyme Treatment for Preparation of α-Amylase, α-Glucosidase, and Dipeptidyl Peptidase (DPP)-IV Inhibitory Peptides from Oat Protein. J Funct Foods 2021, 87, 104829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffernan, S.; Giblin, L.; O’Brien, N. Assessment of the Biological Activity of Fish Muscle Protein Hydrolysates Using in Vitro Model Systems. Food Chem 2021, 359, 129852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd El-Rady, T.K.; Tahoun, A.M.; Abdin, M.; Amin, H.F. Effect of Different Hydrolysis Methods on Composition and Functional Properties of Fish Protein Hydrolysate Obtained from Bigeye Tuna Waste. Int J Food Sci Technol 2023, 58, 6552–6562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture (FishInfo). Resources factsheets 2024.

- Valcarcel, J.; Sanz, N.; Vázquez, J.A. Optimization of the Enzymatic Protein Hydrolysis of By-Products from Seabream (Sparus Aurata) and Seabass (Dicentrarchus Labrax), Chemical and Functional Characterization. Foods 2020, 9, 1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas, M.; Costa, L.; Delgado, J.; Jiménez, S.; Timóteo, V.; Vasconcelos, J.; González, J.A. Deep-Sea Sharks as by-Catch of an Experimental Fishing Survey for Black Scabbardfishes (Aphanopus Spp.) off the Canary Islands (NE Atlantic). Sci Mar 2018, 82, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, I.; Ramos, C.; Coutinho, J.; Bandarra, N.M.; Nunes, M.L. Characterization of Protein Hydrolysates and Lipids Obtained from Black Scabbardfish (Aphanopus Carbo) by-Products and Antioxidative Activity of the Hydrolysates Produced. Process Biochemistry 2010, 45, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasswa, J.; Tang, J.; Gu, X. Functional Properties of Grass Carp ( Ctenopharyngodon Idella), Nile Perch (Lates Niloticus) and Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis Niloticus) Skin Hydrolysates. Int J Food Prop 2008, 11, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Moreno, P.J.; Batista, I.; Pires, C.; Bandarra, N.M.; Espejo-Carpio, F.J.; Guadix, A.; Guadix, E.M. Antioxidant Activity of Protein Hydrolysates Obtained from Discarded Mediterranean Fish Species. Food Research International 2014, 65, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhina, C.F.; Jung, H.Y.; Kim, J.K. Recovery of Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Peptides through the Reutilization of Nile Perch Wastewater by Biodegradation Using Two Bacillus Species. Chemosphere 2020, 253, 126728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacias-Pascacio, V.G.; Morellon-Sterling, R.; Siar, E.-H.; Tavano, O.; Berenguer-Murcia, Á.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Use of Alcalase in the Production of Bioactive Peptides: A Review. Int J Biol Macromol 2020, 165, 2143–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forde, A.; Fitzgerald, G.F. Biotechnological Approaches to the Understanding and Improvement of Mature Cheese Flavour. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2000, 11, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, H.; Iñarra, B.; Labidi, J.; Mendiola, D.; Bald, C. Comparison of Amino Acid Release between Enzymatic Hydrolysis and Acid Autolysis of Rainbow Trout Viscera. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrera-Alvarado, G.; Toldrá, F.; Mora, L. DPP-IV Inhibitory Peptides GPF, IGL, and GGGW Obtained from Chicken Blood Hydrolysates. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 14140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuentes, C.; Verdú, S.; Grau, R.; Barat, J.M.; Fuentes, A. Impact of Raw Material and Enzyme Type on the Physico-Chemical and Functional Properties of Fish by-Products Hydrolysates. LWT 2024, 201, 116247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Yan, W.; Zhang, Y.-Q. Effects of Spray Drying and Freeze Drying on Physicochemical Properties, Antioxidant and ACE Inhibitory Activities of Bighead Carp (Aristichthys Nobilis) Skin Hydrolysates. Foods 2022, 11, 2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, A.; Vázquez, J.A.; Valcarcel, J.; Mendes, R.; Bandarra, N.M.; Pires, C. Characterization of Protein Hydrolysates from Fish Discards and By-Products from the North-West Spain Fishing Fleet as Potential Sources of Bioactive Peptides. Mar Drugs 2021, 19, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Y.-M.; Li, L.-Y.; Chi, C.-F.; Wang, B. Twelve Antioxidant Peptides From Protein Hydrolysate of Skipjack Tuna (Katsuwonus Pelamis) Roe Prepared by Flavourzyme: Purification, Sequence Identification, and Activity Evaluation. Front Nutr 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimada, Kazuko.; Fujikawa, Kuniko.; Yahara, Keiko.; Nakamura, Takashi. Antioxidative Properties of Xanthan on the Autoxidation of Soybean Oil in Cyclodextrin Emulsion. J Agric Food Chem 1992, 40, 945–948. [CrossRef]

- Opitz, S.E.W.; Smrke, S.; Goodman, B.A.; Yeretzian, C. Methodology for the Measurement of Antioxidant Capacity of Coffee. In Processing and Impact on Antioxidants in Beverages; Elsevier, 2014; pp. 253–264.

- Amini Sarteshnizi, R.; Sahari, M.A.; Ahmadi Gavlighi, H.; Regenstein, J.M.; Nikoo, M.; Udenigwe, C.C. Influence of Fish Protein Hydrolysate-Pistachio Green Hull Extract Interactions on Antioxidant Activity and Inhibition of α-Glucosidase, α-Amylase, and DPP-IV Enzymes. LWT 2021, 142, 111019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyaizu, M. Reducing Power - Studies on Products of Browning Reaction. Japanese Journal of Nutrition 1986, 44, 307–315. [Google Scholar]

- Karoud, W.; Sila, A.; Krichen, F.; Martinez-Alvarez, O.; Bougatef, A. Characterization, Surface Properties and Biological Activities of Protein Hydrolysates Obtained from Hake (Merluccius Merluccius) Heads. Waste Biomass Valorization 2019, 10, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, C.; Clemente, T.; Batista, I. Functional and Antioxidative Properties of Protein Hydrolysates from Cape Hake By-products Prepared by Three Different Methodologies. J Sci Food Agric 2013, 93, 771–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decker, E.A.; Welch, B. Role of Ferritin as a Lipid Oxidation Catalyst in Muscle Food. J Agric Food Chem 1990, 38, 674–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Fuentes, C.; Alaiz, M.; Vioque, J. Affinity Purification and Characterisation of Chelating Peptides from Chickpea Protein Hydrolysates. Food Chem 2011, 129, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghdi, S.; Rezaei, M.; Tabarsa, M.; Abdollahi, M. Fish Protein Hydrolysate from Sulfated Polysaccharides Extraction Residue of Tuna Processing By-Products with Bioactive and Functional Properties. Global Challenges 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Jiang, H.; Huang, G. Protein Hydrolysates as Promoters of Non-Haem Iron Absorption. Nutrients 2017, 9, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, T.F.M.; Pessoa, L.G.A.; Seixas, F.A.V.; Ineu, R.P.; Gonçalves, O.H.; Leimann, F.V.; Ribeiro, R.P. Chemometric Evaluation of Enzymatic Hydrolysis in the Production of Fish Protein Hydrolysates with Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitory Activity. Food Chem 2022, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, G.; Zhao, T.; Zhao, Y.; Sun-Waterhouse, D.; Qiu, C.; Huang, P.; Zhao, M. Effect of Anchovy (Coilia Mystus) Protein Hydrolysate and Its Maillard Reaction Product on Combating Memory-Impairment in Mice. Food Research International 2016, 82, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elavarasan, K.; Shamasundar, B.A. Angiotensin I-converting Enzyme Inhibitory Activity of Protein Hydrolysates Prepared from Three Freshwater Carps (Catla Catla, Labeo Rohita and Cirrhinus Mrigala) Using Flavorzyme. Int J Food Sci Technol 2023, 49, 1344–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists 1990.

- Saint-Denis, T.; Goupy, J. Optimization of a Nitrogen Analyser Based on the Dumas Method. Anal Chim Acta 2004, 515, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapatinha, M.; Afonso, C.M.; Cardoso, C.L.; Pires, C.; Mendes, R.; Montero, M.P.; Gómez-Guillén, M.C.; Bandarra, N.M. Lipid Nutritional Value and Bioaccessibility of Novel Ready-to-eat Seafood Products with Encapsulated Bioactives. Int J Food Sci Technol 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, J.A.; Fernández-Compás, A.; Blanco, M.; Rodríguez-Amado, I.; Moreno, H.; Borderías, J.; Pérez-Martín, R.I. Development of Bioprocesses for the Integral Valorisation of Fish Discards. Biochem Eng J 2019, 144, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, P.M.; Petersen, D.; Dambmann, C. Improved Method for Determining Food Protein Degree of Hydrolysis. J Food Sci 2001, 66, 642–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picot, L.; Ravallec, R.; Fouchereau-Péron, M.; Vandanjon, L.; Jaouen, P.; Chaplain-Derouiniot, M.; Guérard, F.; Chabeaud, A.; LeGal, Y.; Alvarez, O.M.; et al. Impact of Ultrafiltration and Nanofiltration of an Industrial Fish Protein Hydrolysate on Its Bioactive Properties. J Sci Food Agric 2010, n/a-n/a. [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant Activity Applying an Improved ABTS Radical Cation Decolorization Assay. Free Radic Biol Med 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansawasdi, C.; Kawabata, J.; Kasai, T. Alpha-Amylase Inhibitors from Roselle ( Hibiscus Sabdariffa Linn.) Tea. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 2000, 64, 1041–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Qiu, L.; Song, H.; Xiao, T.; Luo, T.; Deng, Z.; Zheng, L. Inhibition Mechanism of Oligopeptides from Soft-shelled Turtle Egg against A-glucosidase and Their Gastrointestinal Digestive Properties. J Food Biochem 2022, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, C.-B.; Lee, K.-H.; Je, J.-Y. Enzymatic Production of Bioactive Protein Hydrolysates from Tuna Liver: Effects of Enzymes and Molecular Weight on Bioactivity. Int J Food Sci Technol 2010, 45, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Aluko, R.E.; Muir, A.D. Improved Method for Direct High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Assay of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme-Catalyzed Reactions. J Chromatogr A 2002, 950, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Co-Products | Protein, % | Fat, % | Moisture, % | Ash, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BS | RM | 14.3 ± 1.9 A | 8.1 ± 0.3 A | 71.0 ± 0.1 B | 6.9 ± 0.4 C |

| A | 77.1 ± 0.1 g | 2.3 ± 0.1 a,b | 5.4 ± 0.1 b | 15.2 ± 0.0 d | |

| P | 56.8 ± 0.2 a | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A + P | 64.2 ± 0.4 c | 0.5 ± 0.0 a | 9.1 ± 0.1 f | 17.7 ± 0.1 f | |

| AP | 68.4 ± 0.0 d | 4.1 ± 0.2 c,d | 7.3 ± 0.3 c | 18.7 ± 0.7 f | |

| GB | RM | 16.5 ± 0.6 A,B | 11.6 ± 0.2 B | 60.9 ± 0.1 A | 5.3 ± 0.0 B |

| A | 70.0 ± 1.0 e | 5.6 ± 0.5 d | 4.5 ± 0.1 a | 16.5 ± 0.2 e | |

| P | 72.9 ± 0.5 f | 11.9 ± 1.0 f | 7.7 ± 0.0 d | 12.7 ± 0.0 b,c | |

| A + P | 59.6 ± 0.8 b | 12.1 ± 1.2 f | 7.2 ± 0.1 c | 17.7 ± 0.8 f | |

| AP | 77.1 ± 0.5 g | 9.3 ± 0.0 e | 5.5 ± 0.1 b | 9.7 ± 0.3 a | |

| NP | RM | 19.3 ± 0.3 B | 9.1 ± 0.9 A | 72.9 ± 0.1 C | 2.4 ± 0.2 A |

| A | 82.2 ± 0.2 h | 2.0 ± 0.4 a,b | 4.3 ± 0.1 a | 13.4 ± 0.3 c | |

| P | 86.5 ± 0.1 i | n.d. | 5.3 ± 0.0 b | 12.3 ± 0.1 b | |

| A + P | 68.6 ± 0.1 d | 3.6 ± 0.1 b,c | 8.7 ± 0.1 e | 16.3 ± 0.2 e | |

| AP | 81.7 ± 0.1 h | 3.3 ± 1.0 b,c | 5.2 ± 0.0 b | 12.7 ± 0.0 b,c |

| Hydrolysate raw material | Enzyme | DH (%) | Y hydrolysis (%) | Y protein (%) |

| 180 min / 360 min | ||||

| BS | A | 25.9 ± 0.4 b | 12.5 ± 0.2 c | 68.3 ± 0.1 d |

| P | 28.2 ± 0.2 b,c | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A + P | 29.6 ± 0.5 c,d / 61.4 ± 0.9 i | 15.7 ± 0.3 d,e | 73.3 ± 0.4 f | |

| AP | 44.7 ± 0.5 g / 51.9 ± 0.9 h | 14.7 ± 0.3 c | 71.9 ± 0.0 e | |

| GB | A | 36.2 ± 0.6 f | 16.5 ± 0.3 d | 71.3 ± 1.0 e |

| P | 32.8 ± 1.2 e | 5.9 ± 0.1 b | 26.2 ± 0.2 b | |

| A + P | 31.8 ± 0.3 d,e / 52.0 ± 0.4 h | 18.8 ± 0.2 f | 67.9 ± 0.9 d | |

| AP | 50.8 ± 2.8 h / 58.1 ± 0.8 g | 16.9 ± 0.3 e | 80.7 ± 0.7 g | |

| NP | A | 28.5 ± 2.9 b,c | 14.0 ± 1.76 c | 55.4 ± 0.1 c |

| P | 8.5 ± 0.4 a | 3.4 ± 0.2 a | 16.2 ± 0.0 a | |

| A + P | 29.3 ± 0.7 c,d / 56.1 ± 1.8 g | 11.3 ± 0.3 g | 79.7 ± 0.1 g | |

| AP | 36.5 ± 0.6 f / 45.0 ± 1.5 g | 12.6 ± 0.4 f | 80.8 ± 0.1 g |

| Enzyme | Time (min) | Range | Peak area (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BS | GB | NP | |||

| Alcalase (A) | 180 * | >1000 Da | 23.6 | 19.7 | 21.3 |

| 1000-500 Da | 13.0 | 20. 2 | 10.5 | ||

| 500 - 100 Da | 55.1 | 56.1 | 68.3 | ||

| <100 Da | 8.2 | 4.0 | --- | ||

| Protana (P) | 180 * | >1000 Da | n.d. | 4.7 | 5.1 |

| 1000-500 Da | n.d. | 22.2 | 6.2 | ||

| 500 - 100 Da | n.d. | 68.9 | 83.6 | ||

| <100 Da | n.d. | 4.3 | 5.04 | ||

| Alcalase followed by Protana (A+P) |

5 | >1000 Da | 26.3 | 17.7 | 17.2 |

| 1000-500 Da | 6.2 | 18.0 | 4.6 | ||

| 500 - 100 Da | 59.1 | 60.6 | 78.2 | ||

| <100 Da | 8.3 | 3.8 | --- | ||

| 180 | >1000 Da | 24.1 | 15.4 | 21.8 | |

| 1000-500 Da | 12.1 | 21.0 | 8.8 | ||

| 500 - 100 Da | 53.6 | 59.0 | 69.5 | ||

| <100 Da | 10.2 | 4.6 | --- | ||

| 360 | >1000 Da | 15.8 | 7.67 | 9.0 | |

| 1000-500 Da | 11.3 | 19.89 | --- | ||

| 500 - 100 Da | 54.3 | 62.2 | 80.9 | ||

| <100 Da | 18.6 | 10.23 | 10.1 | ||

| Alcalase and Protana (AP) |

5 | >1000 Da | 24.9 | 17.2 | 22.2 |

| 1000-500 Da | 5.0 | 16.8 | 4.9 | ||

| 500 - 100 Da | 59.2 | 62.8 | 68.8 | ||

| <100 Da | 11.0 | 3.1 | 4.1 | ||

| 180 | >1000 Da | 14.4 | 10.0 | 15.7 | |

| 1000-500 Da | 17.5 | 17.4 | 10.8 | ||

| 500 - 100 Da | 50.2 | 60.6 | 66.5 | ||

| <100 Da | 17.8 | 12.0 | 7.0 | ||

| 360 | >1000 Da | 9.6 | 8.7 | 11.7 | |

| 1000-500 Da | 25.3 | 16.1 | --- | ||

| 500 - 100 Da | 47.2 | 62.1 | 79.3 | ||

| <100 Da | 17.8 | 13.1 | 9.0 | ||

| Enzyme | Time (min) | Temperature (°C) | pH | E/S ratio (v/w) |

| Alcalase (A) | 180 | 60 | 8.5 | 1% |

| Protana (P) | 180 | 55 | 5.5 | 1% |

| Alcalase + Protana (A+P) | 180; 180 | 55 | 8.5 (A); 5.5 (P) | 1% (A); 1% (P) |

| Alcalase and Protana (AP) | 360 | 55 | 7 | 1% and 1% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).