Submitted:

21 December 2024

Posted:

23 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Perch Hydrolysate Preparation

2.2. Determination of Free and Hydrolyzed Amino Acid Compositions

2.3. Analysis of Soluble Protein Content

2.4. Determination of Peptide Content by α-Amino Group Content

2.5. Determination of Degree of Hydrolysis

2.6. Analysis of Protein Profile

2.7. Identification of Peptide Sequence by LC-MS/MS Analysis

2.8. Wound Healing Assay in Animal Model

2.9. Analytical Assays for Fibronectin, Procollagen I and Hyaluronan in Human Fibroblasts

2.10. Statistical Analysis of Data

3. Results

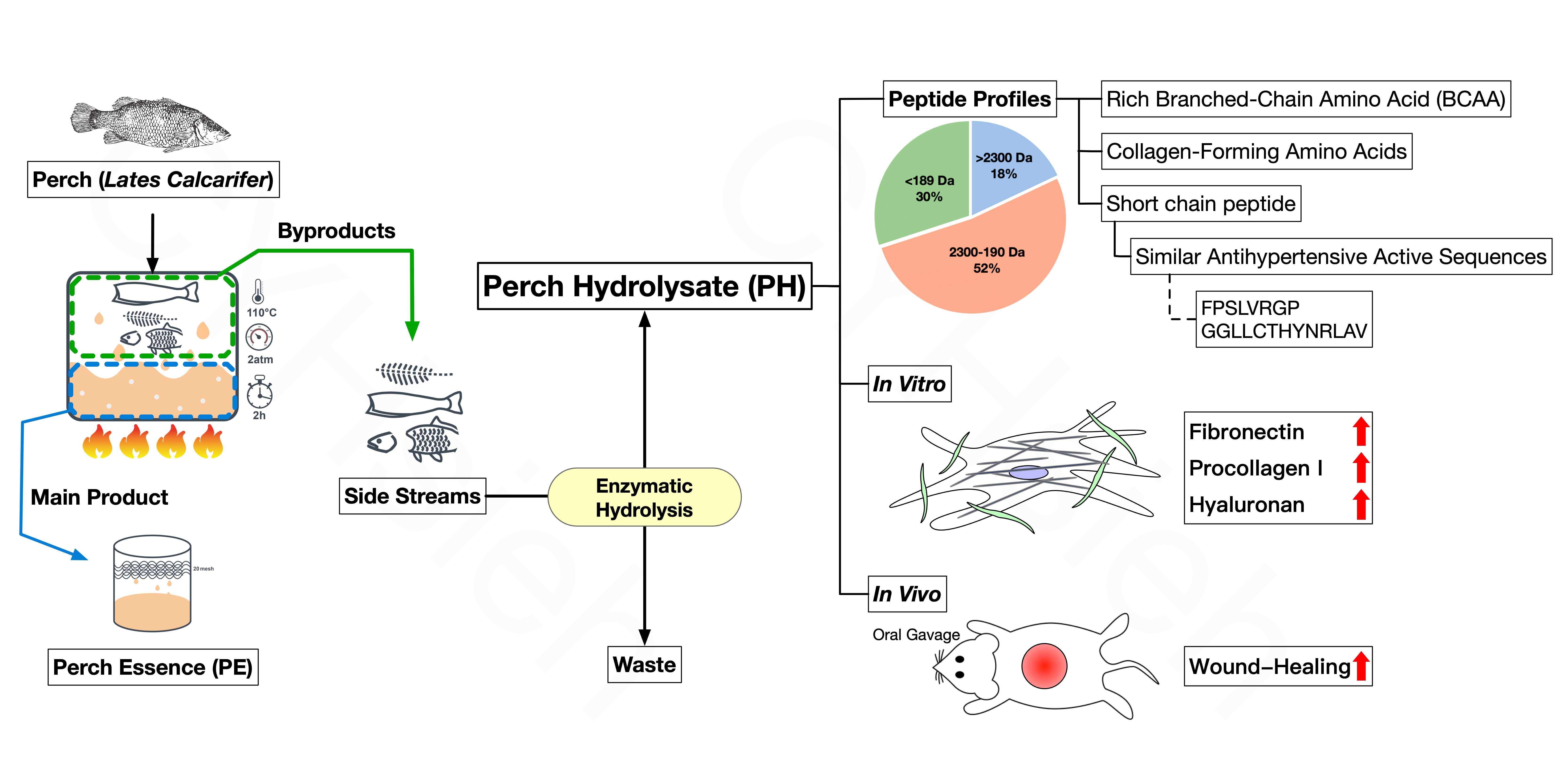

3.1. Upcycled Perch Hydrolysates from Perch Side Steams

3.2. Protein Profiles and Amino Acid Composition in PH

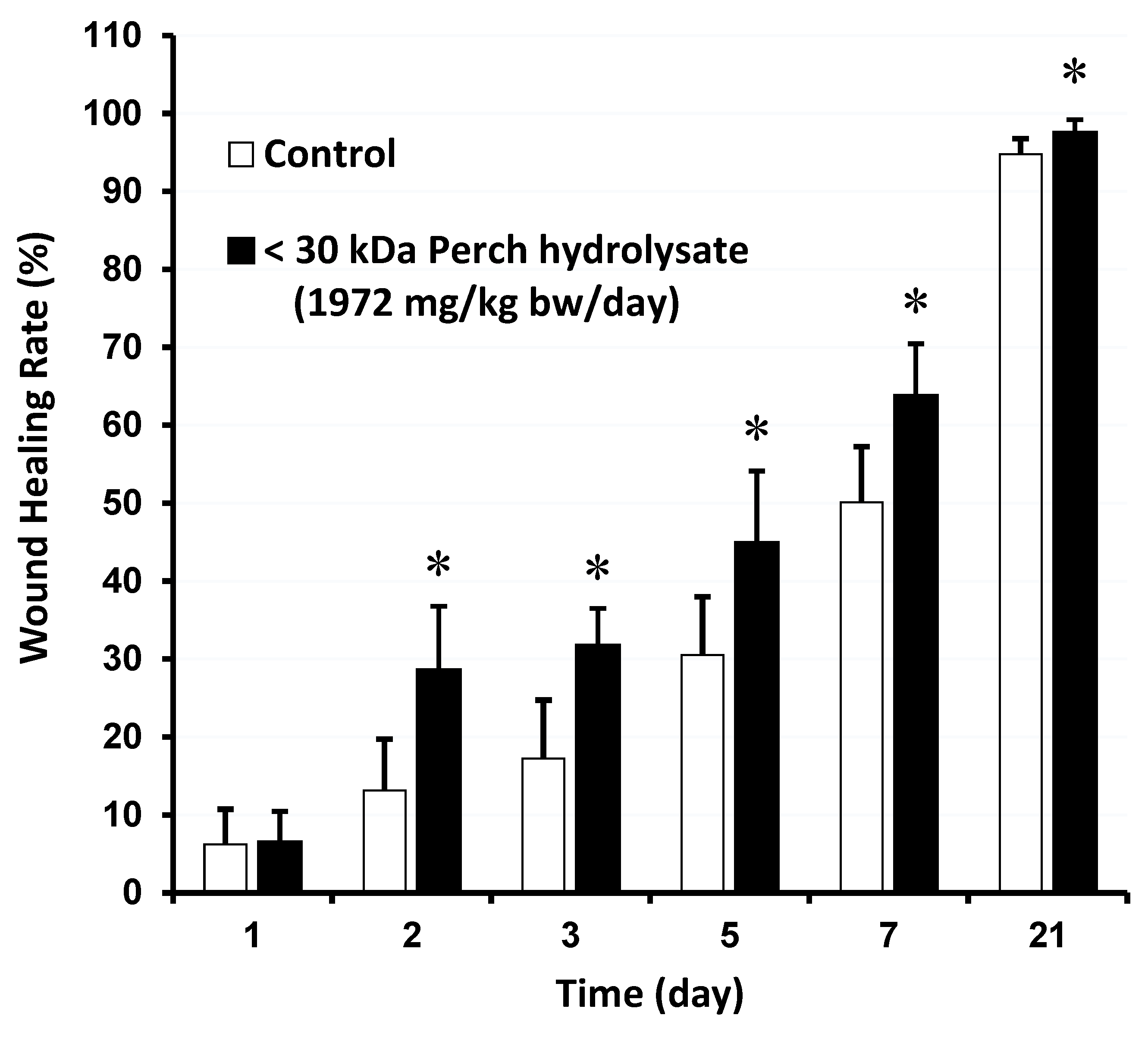

3.3. Effect of PH on Wound Healing Rate in the Animal Model

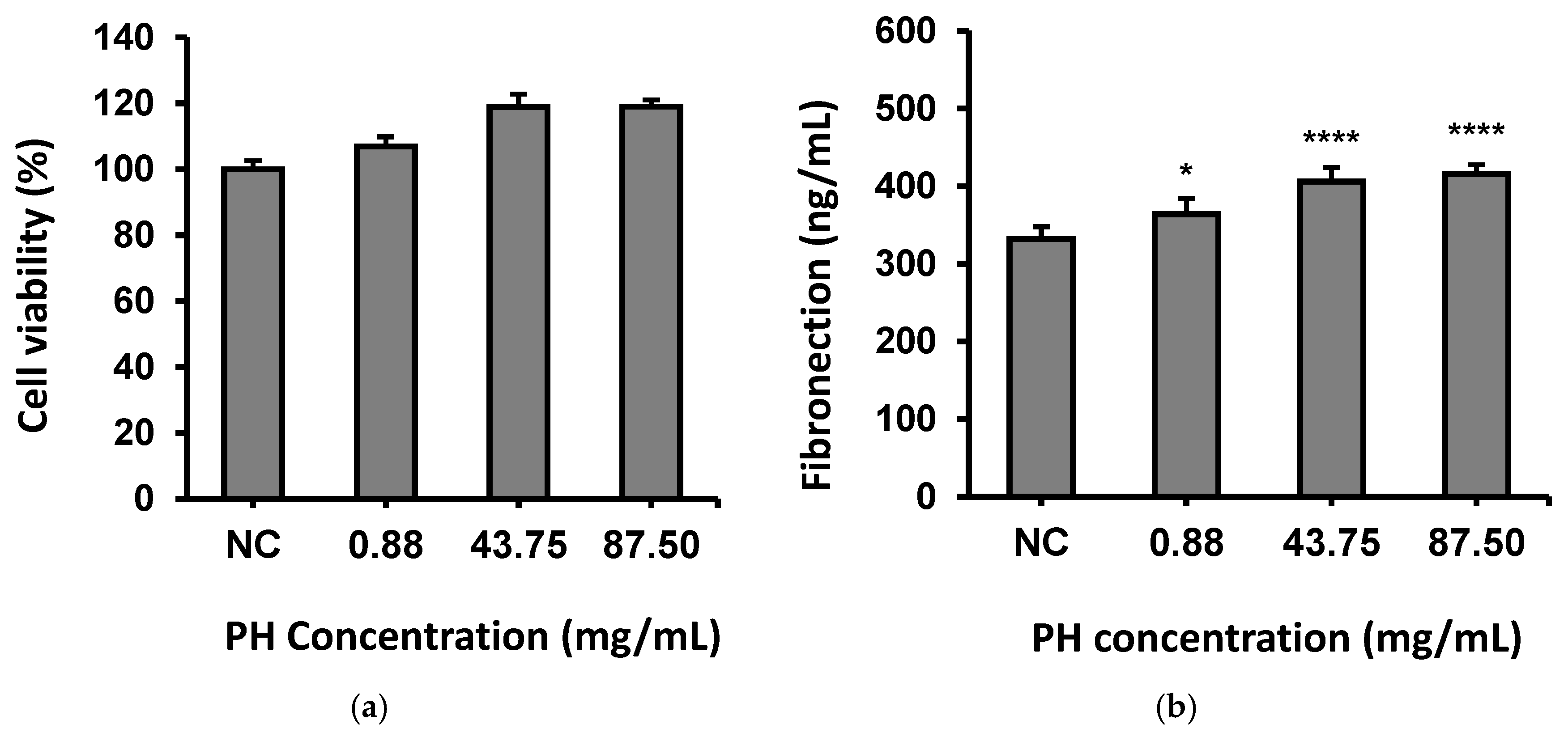

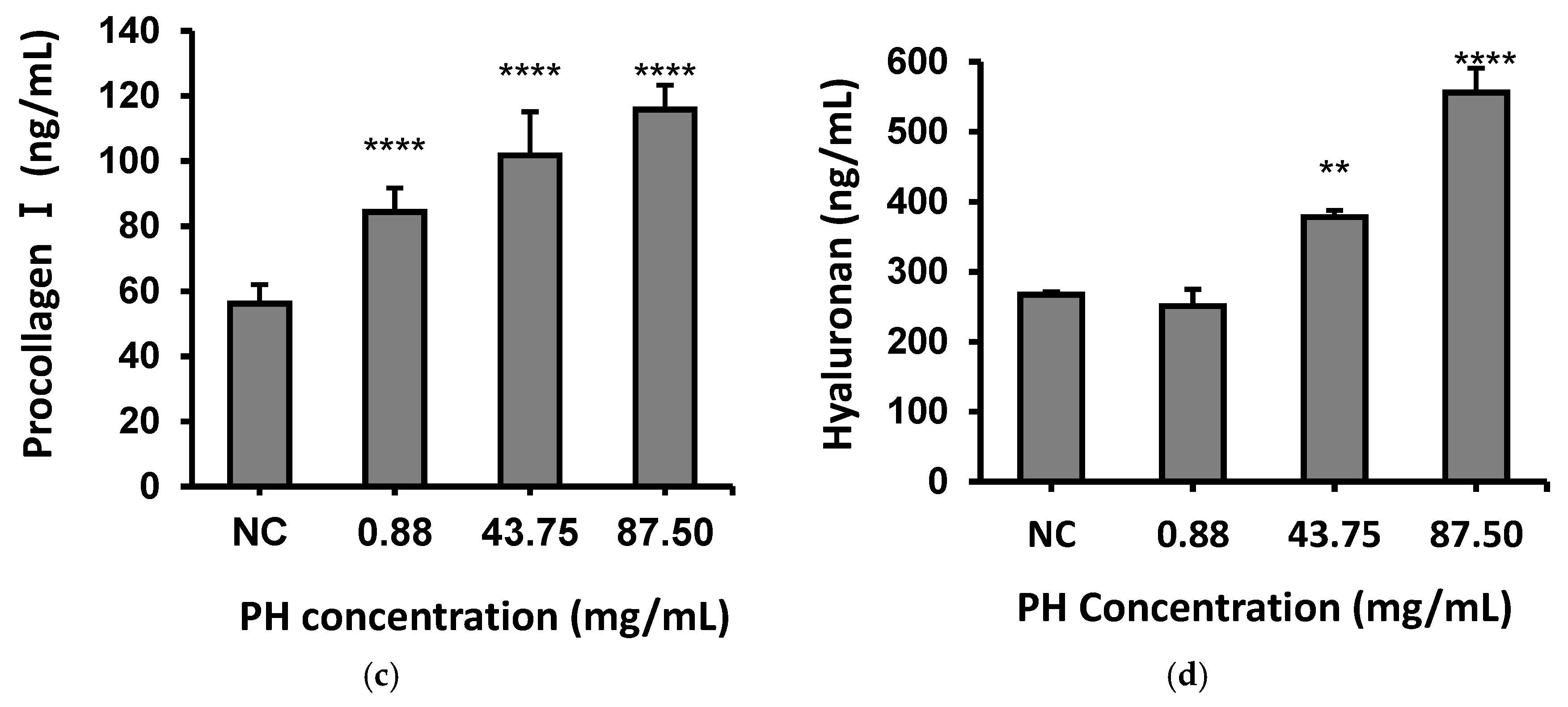

3.4. Effects of PH on Fibroblasts Through Secreting Fibronectin, Procollagen I and Hyaluronan

3.5. Relative Abundance of Peptide Sequence in Perch Hydrolysates

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ohshima, T. By-products and seafood production in japan. Journal of Aquatic Food Product Technology 1996, 5, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karayannakidis, P.D.; Zotos, A. Fish processing by-products as a potential source of gelatin: a review. Journal of Aquatic Food Product Technology 2016, 25, 65–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-González, D.C.; Rodríguez-Félix, D.E.; García-Sifuentes, C.O.; Castillo-Ortega, M.M.; Encinas-Encinas, J.C.; Ortega, H.D.C.S.; Romero-García, J. Collagen scaffold derived from tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) skin: obtention, structural and physico-chemical properties. Journal of Aquatic Food Product Technology 2022, 31, 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remme, J.; Tveit, G.M.; Toldnesb, B.; Slizyte, R.; Carvajal, A.K. Production of protein hydrolysates from cod (Gadus morhua) heads: lab and pilot scale studies. Journal of Aquatic Food Product Technology 2022, 31, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehinde, B.A.; Sharma, P. Recently isolated antidiabetic hydrolysates and peptides from multiple food sources: a review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2020, 60, 322–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbarian, M.; Khani, A.; Eghbalpour, S.; Uversky, V.N. Bioactive Peptides: Synthesis, Sources, Applications, and Proposed Mechanisms of Action. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 23–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powers, J.-P. S.; Hancock, R.E.W. The relationship between peptide structure and antibacterial activity. Peptides 2003, 24, 1681–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, R.; Meisel, H. Food-derived peptides with biological activity: from research to food applications. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2007, 18, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karami, Z.; Akbari-Adergani, B. Bioactive food derived peptides: a review on correlation between structure of bioactive peptides and their functional properties. Journal of Food Science and Technology 2019, 56, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sosalagere, C.; Kehinde, B.A.; Sharma, P. Isolation and functionalities of bioactive peptides from fruits and vegetables: A reviews. Food Chemistry, 2022; 366, 130494. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Q.; Chen, P.; Chen, X. Bioactive peptides derived from fermented foods: Preparation and biological activities. Journal of Functional Foods 2023, 101, 105404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senevirathne, M.; Kim, S.-K. Development of bioactive peptides from fish proteins and their health promoting ability. Advances in Food and Nutrition Research 2012, 65, 235–248. [Google Scholar]

- Cudennec, B.; Ravallec-Plé, R.; Courois, E.; Fouchereau-Peron, M. Peptides from fish and crustacean by-products hydrolysates stimulate cholecystokinin release in STC-1 cells. Food Chemistry 2008, 111, 970–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazeer, R.A.; Sampath Kumar, N.S.; Jai Ganesh, R. In vitro and in vivo studies on the antioxidant activity of fish peptide isolated from the croaker (Otolithes ruber) muscle protein hydrolysate. Peptides 2012, 35, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dale, H.F.; Madsen, L.; Lied, G.A. Fish–derived proteins and their potential to improve human health. Nutrition Reviews 2019, 77, 572–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, M.J.; Carson, B.P. The potential role of fish-derived protein hydrolysates on metabolic health, skeletal muscle mass and function in ageing. Nutrients, 2020; 12, 2434. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, D.; Cui, S.; Chen, L.; Zheng, S.; Zhao, D.; Yin, X.; Yang, F.; Chen, J. Marine-Derived bioactive peptides self-assembled multifunctional materials: antioxidant and wound healing. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 12–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, T.; Zhang, K.; Li, B.; Hou, H. Effects of oral administration of peptides with low molecular weight from Alaska Pollock (Theragra chalcogramma) on cutaneous wound healing. Journal of Functional Foods 2018, 48, 682–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oslan, S.N.H.; Li, C.X.; Shapawi, R.; Mokhtar, R.A.M.; Noordin, W.N.M.; Huda, N. Extraction and characterization of bioactive fish by-product collagen as promising for potential wound healing agent in pharmaceutical applications: Current Trend and Future Perspective. International Journal of, 2022; 9437878. [Google Scholar]

- Lowry, O.H.; Rosebrough, N.J.; Farr, A.L.; Randall, R.J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. The Journal of Biological and Chemistry 1951, 193, 265–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, F.C.; Swaisgood, H.E.; Porter, D.H.; Catignani, G.L. Spectrophotometric Assay Using o-Phthaldialdehyde for Determination of Proteolysis in Milk and Isolated Milk Proteins, Journal of Dairy Science 1983, 66, 1219-1227.

- Linarès, E.; Larré, C.; Popineau, Y. Freeze- or spray-dried gluten hydrolysates. 1. Biochemical and emulsifying properties as a function of drying process, Journal of Food Engineering 2001, 48, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, D.; Shaikh, A.R. Interaction of arginine, lysine, and guanidine with surface residues of lysozyme: implication to protein stability. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics 2016, 34, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, B.; Shin, K.H.; Kim, S.K. Muscle Protein Hydrolysates and Amino Acid Composition in Fish. Marine Drugs 2021, 19, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felician, F.F.; Yu, R.H.; Li, M.Z.; Li, C.J.; Chen, H.Q.; Jiang, Y.; Tang, T.; Qi, W.-Y.; Xu, H.M. The wound healing potential of collagen peptides derived from the jellyfish Rhopilema esculentum. Chinese Journal of Traumatology 2019, 22, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, M.; Verma, A.K.; Patel, R. Collagen extraction and recent biological activities of collagen peptides derived from sea-food waste: a review. Sustainable Chemistry and Pharmacy 2020, 18, 100315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtkowiak, D.; Frydrychowski, A.F.; Hadzik, J.; Dominiak, M. Identification of small peptides of acidic collagen extracts from silver carp skin and their therapeutic relevance. Advances in Clinical and Experimental Medicine 2016, 25, 227–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Yang, P.; Zhou, C.; Li, S.; Hong, P. Marine collagen peptides from the skin of Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus): Characterization and wound healing evaluation. Marine drugs 2017, 15, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, E.M.; Oliveira, A.S.; Silva, S.; Ribeiro, A.B.; Pereira, C.F.; Ferreira, C.; Casanova, F.; Pereira, J.O.; Freixo, R.; Pintado, M.E.; Carvalho, A.P.; Ramos, O.L. Spent yeast waste streams as a sustainable source of bioactive peptides for skin applications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24(3), 24–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, H.; Chang, J.-H.; Hung, Y.-T.; Lin, C.-C. The protein profile of perch essence and its improvement of metabolic syndrome in vitro. MOJ Food Processing & Technology 2022, 10, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui, S.A.; Schulte, H.; Pleissner, D.; Schönfelder, S.; Kvangarsnes, K.; Dauksas, E.; Rustad, T.; Cropotova, J.; Heinz, V.; Smetana, S. Transformation of seafood side-streams and residuals into valuable products. Foods 2023, 12, 12–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.-S.; Lee, W.W.; Lee, J.H.; Sanjeewa, K.K.A.; Fernando, I.P.S.; Ko, S.-C.; Lee, S.-H.; Kim, Y.-T.; Jeon, Y.-J. Purification and identification of an antioxidative peptide from digestive enzyme hydrolysis of cutlassfish muscle. Journal of Aquatic Food Product Technology 2018, 27, 934–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phadke, G.G.; Rathod, N.B.; Ozogul, F.; Elavarasan, K.; Karthikeyan, M.; Shin, K.-H.; Kim, S.-K. Exploiting of secondary raw materials from fish processing industry as a source of bioactive peptide-rich protein hydrolysates. Marine Drugs 2021, 19, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ucak, I.; Afreen, M.; Montesano, D.; Carrillo, C.; Tomasevic, I.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Barba, F.J. Functional and bioactive properties of peptides derived from marine side streams. Marine Drugs 2021, 19, 19–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, C.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Z.-G.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Z.- K.; Wang, B.; Luo, H.- Y. Evaluation of the anti-inflammatory activity of enzymatic hydrolysis peptide sep-3 from Skipjack (Katsuwonus pelamis) based on NF-κB and MAPK pathways. Journal of Aquatic Food Product Technology 2022, 31, 1128–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Xu, J.; Tian, Y.; Liu, W.; Peng, B. Marine fish peptides (collagen peptides) compound intake promotes wound healing in rats after cesarean section. Food & Nutrition Research 2020, 64, 4247. [Google Scholar]

- Abachi, S.; Pilon, G.; Marette, A.; Bazinet, L.; Beaulieu, L. Beneficial effects of fish and fish peptides on main metabolic syndrome associated risk factors: Diabetes, obesity and lipemia. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2022, 63, 7896–7944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arribas-López, E.; Zand, N.; Ojo, O.; Snowden, M.J.; Kochhar, T. The effect of amino acids on wound healing: a systematic review and meta-analysis on arginine and glutamine. Nutrients 2021, 13, 13–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Xu, M.; Liang, R.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y. Oral administration of marine collagen peptides prepared from chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta) improves wound healing following cesarean section in rats. Food & Nutrition Research 2015, 59, 26411. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, L.V.; Shakila, R.J.; Jeyasekaran, G. In vitro anti-cancer, anti-diabetic, anti-inflammation and wound healing properties of collagen peptides derived from unicorn leatherjacket (Aluterus Monoceros) at different hydrolysis. Turkish Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2019, 19, 551–560. [Google Scholar]

- Bauchart, C.; Morzel, M.; Chambon, C.; Mirand, P.; Reynès, C.; Buffière, C.; Rémond, D. Peptides reproducibly released by in vivo digestion of beef meat and trout flesh in pigs. British Journal of Nutrition 2007, 98, 1187–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rémond, D.; Savary-Auzeloux, I.; Gatellier, P.; Santé-Lhoutellier, V. Nutritional properties of meat peptides and proteins: impact of processing. SCIENCES DES ALIMENTS 2008, 28, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skibska, A.; Renata, P. Signal peptides - Promising ingredients in cosmetics. Current Protein & Peptide Science 2021, 22, 22–716. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, A.C.; Costa, T.G.; Andrade, Z.A.; Medrado, A.R.A.P. Wound healing –A literature review. Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia 2016, 91, 614–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, P.; Shanthi, C. Cryptic peptides from collagen: a critical review. Protein & Peptide Letters, 2016; 23, 664–672. [Google Scholar]

- Sivaraman, K.; Shanthi, C. Matrikines for therapeutic and biomedical applications. Life Science 2018, 214, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Castro Brás, L.E.; Frangogiannis, N.G. Extracellular matrix-derived peptides in tissue remodeling and fibrosis. Matrix Biology, 2020; 91–92, 176–187. [Google Scholar]

- Graça, M.F.P.; Miguel, S.P.; Cabral, C.S.D.; Correia, I.J. Hyaluronic acid-Based wound dressings: A review. Carbohydrate Polymers 2020, 1, 116364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermeirssen, V.; Camp, J.; Verstraete, W. Bioavailability of angiotensin I converting enzyme inhibitory peptides. British Journal of Nutrition 2004, 92, 357–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosulski, F.W.; Imafidon, G.I. Amino acid composition and nitrogen-to-protein conversion factors for animal and plant foods. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 1990, 38, 38–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausch, F.; Shan, L.; Santiago, N.A.; Gray, G.M.; Khosla, C. Intestinal digestive resistance of immunodominant gliadin peptides. American Journal Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology 2002, 283, G996–G1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Hydrolysis time (hr) |

α-Amino group concentration (mg/mL) |

Hydrolysis degree (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 4.62 ± 0.34 | 10.68 |

| 2 | 9.63 ± 0.28 | 22.28 |

| 4 | 12.43 ± 0.17 | 28.75 |

| 5 | 18.66 ± 0.32 | 43.14 |

| 6 | 18.88 ± 0.64 | 43.67 |

| 10 | 21.49 ± 0.09 | 49.69 |

| 24 | 24.84 ± 0.23 | 57.45 |

| Molecular weight (Da) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Perch essence | Perch hydrolysate (PH) | |

| >2300 | 62.9 | 18.4 |

| 2300-1200 | 14.5 | 15.2 |

| 1199-580 | 10.7 | 15.8 |

| 579-240 | 7.9 | 17.0 |

| 239-189 | 1.3 | 4.0 |

| <189 | 2.7 | 29.6 |

| Average | 5843 | 1289 |

| Amino Acid | Concentration (mg/100g) |

|---|---|

| Leucine | 212.84 |

| Lysine | 113.29 |

| Valine | 96.22 |

| Arginine | 94.60 |

| Phenylalanine | 84.75 |

| Isoleucine | 87.41 |

| Methionine | 62.24 |

| Tyrosine | 50.58 |

| Proline | 20.02 |

| Carnosine | 8.80 |

| Tryptophan | 4.80 |

| β-Aminoisobutyric Acid | 4.75 |

| DL-plus allo-δ-Hydroxylysine | 4.52 |

| Cystathionine | 4.47 |

| Cysteine | 3.44 |

| Ornithine | 2.31 |

| γ-Aminobutyric Acid | 2.32 |

| Hydroxyproline | N.D. |

| Total | 890.58 |

| Hydrolyzed Amino Acid Profiles | Concentration (mg/100g) |

|---|---|

| Glutamic acid | 957 |

| Aspartic acid | 660 |

| Glycine | 631 |

| Lysine | 574 |

| Alanine | 500 |

| Leucine | 499 |

| Arginine | 443 |

| Proline | 383 |

| Threonine | 332 |

| Valine | 332 |

| Isoleucine | 290 |

| Serine | 283 |

| Phenylalanine | 256 |

| Methionine | 202 |

| Hydroxyproline | 169 |

| Histidine | 166 |

| Total | 6677 |

| Sequence | Relative abundance (%) |

|---|---|

| FPSLVRGP | 6.21% |

| GGLLCTHYNRLAV | 5.16% |

| GALGMLGDYSLV | 2.89% |

| LNLAMNALDLYL | 2.87% |

| MGLLCKGSPATP | 2.79% |

| TSEGTRVAPW | 2.66% |

| QLGMLMYGPGLTGQ | 1.99% |

| PEDVLLDAFKVLDPKYHRT | 1.90% |

| MGLGTPWLNQF | 1.72% |

| GMTGLWPW | 1.49% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).