Submitted:

02 December 2024

Posted:

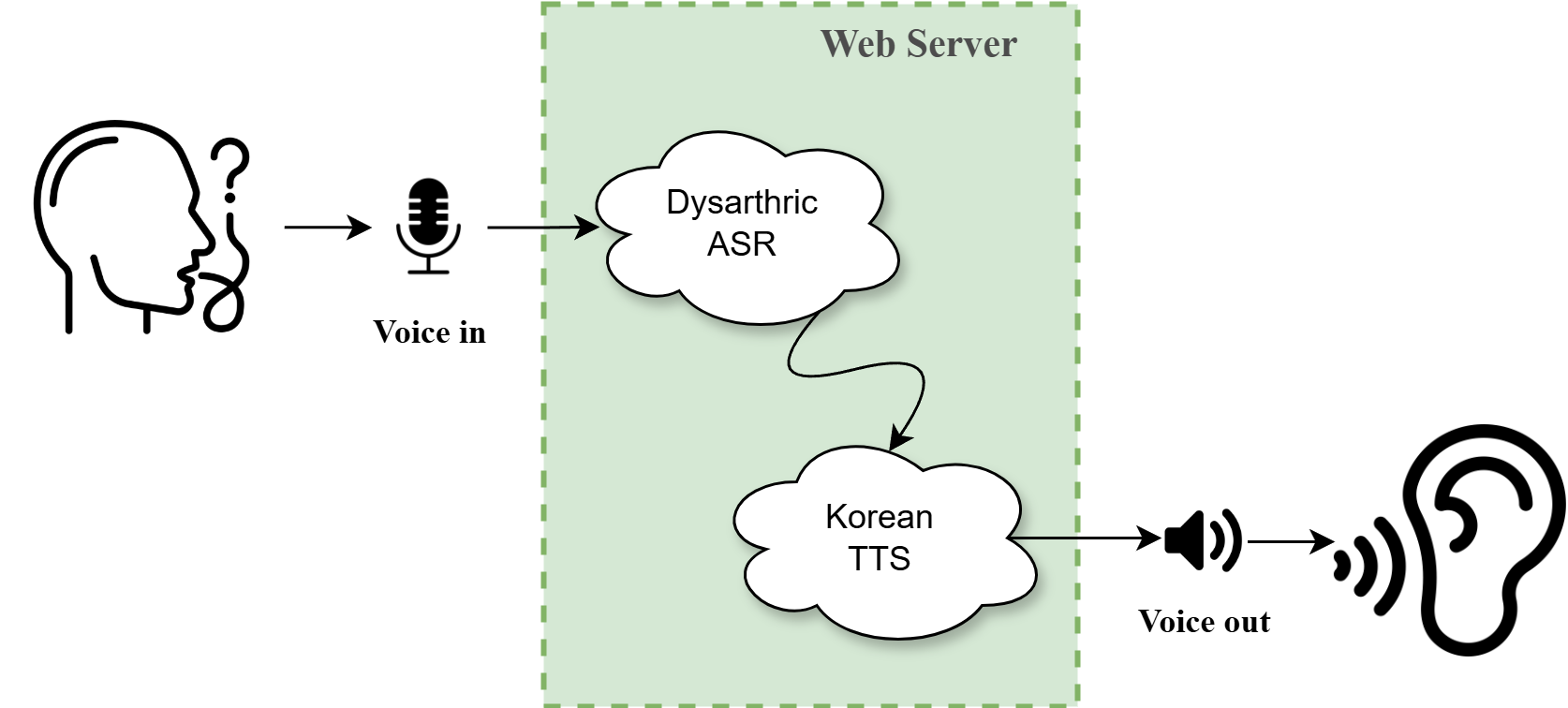

03 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

2.1. AAC:VIVOCA

2.2. Korean Dysarthric Speech Recognition

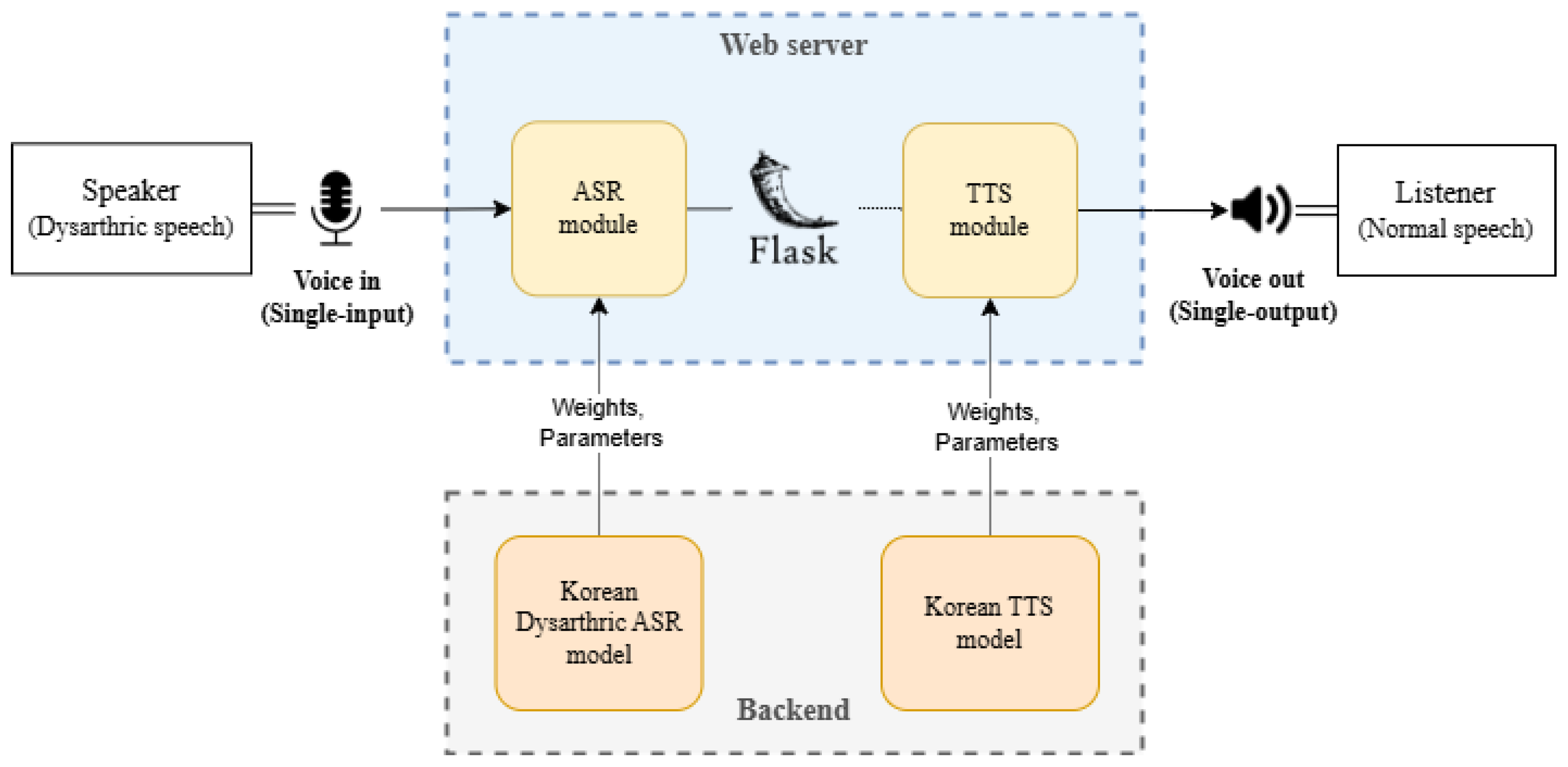

3. Proposed Real-Time Communication Aid System for Korean Dysarthric Speech

- ASR model for Korean dysarthric speech recognition: This model processes speech input from individuals with dysarthria, identifying and converting it into textual information.

- TTS model for normal speech synthesis: Based on the recognized text, this model generates high-quality non-dysarthric speech, making the output more natural and intelligible for effective communication.

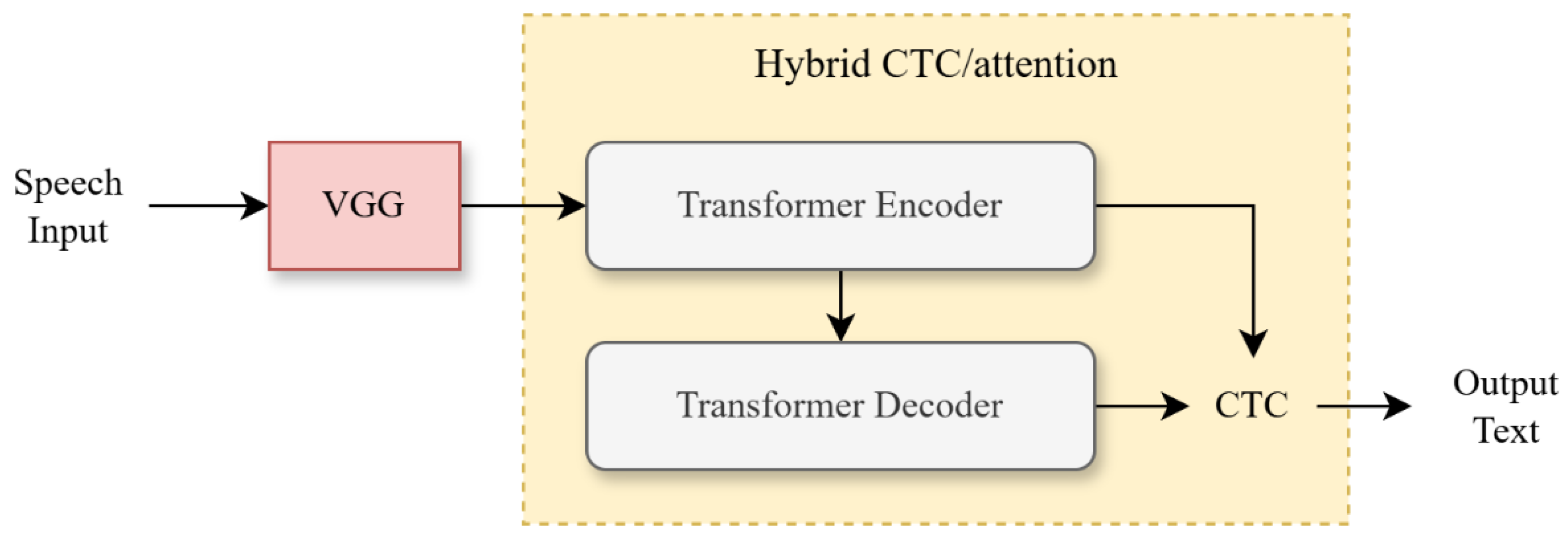

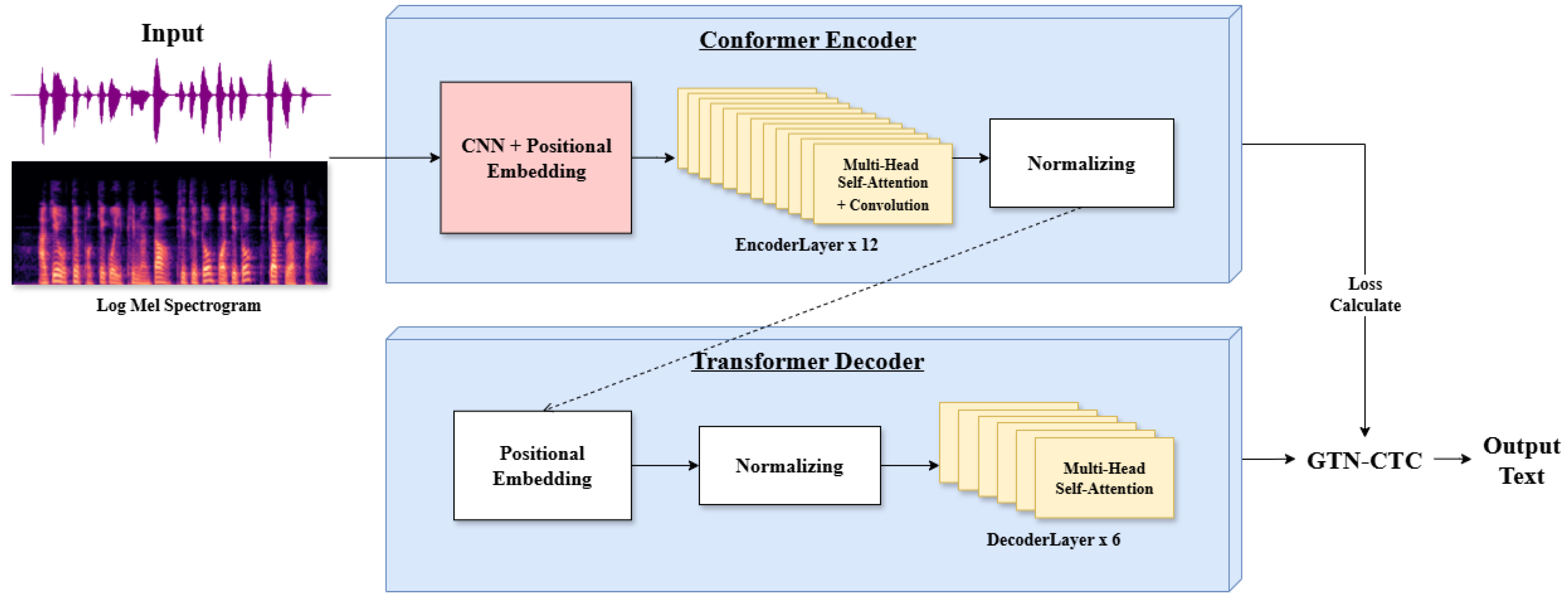

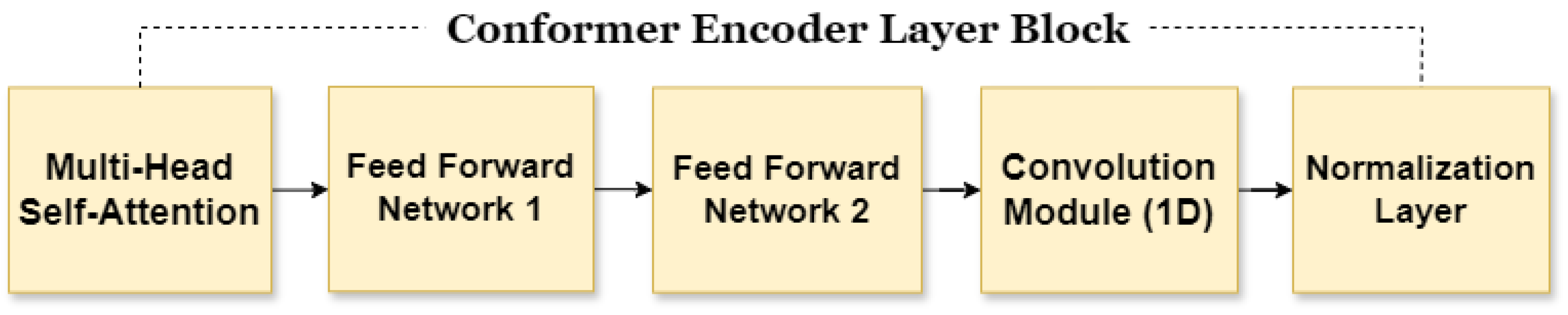

3.1. Conformer-Based Korean Dysarthric ASR

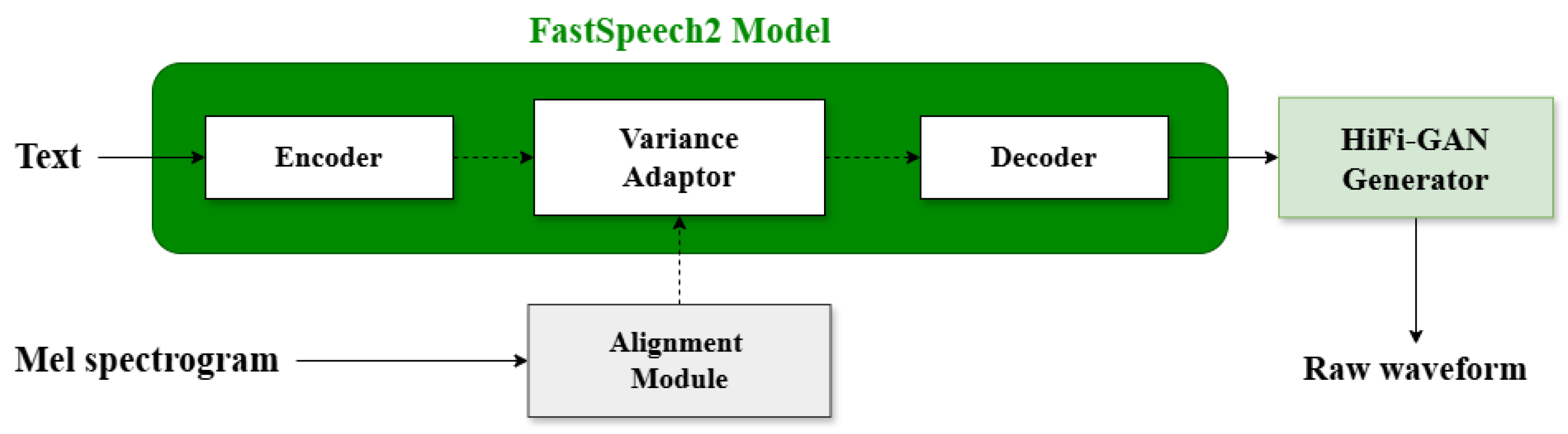

3.2. Korean TTS Model

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.2. Experimental Results

4.2.1. ASR Model

4.2.2. TTS Model

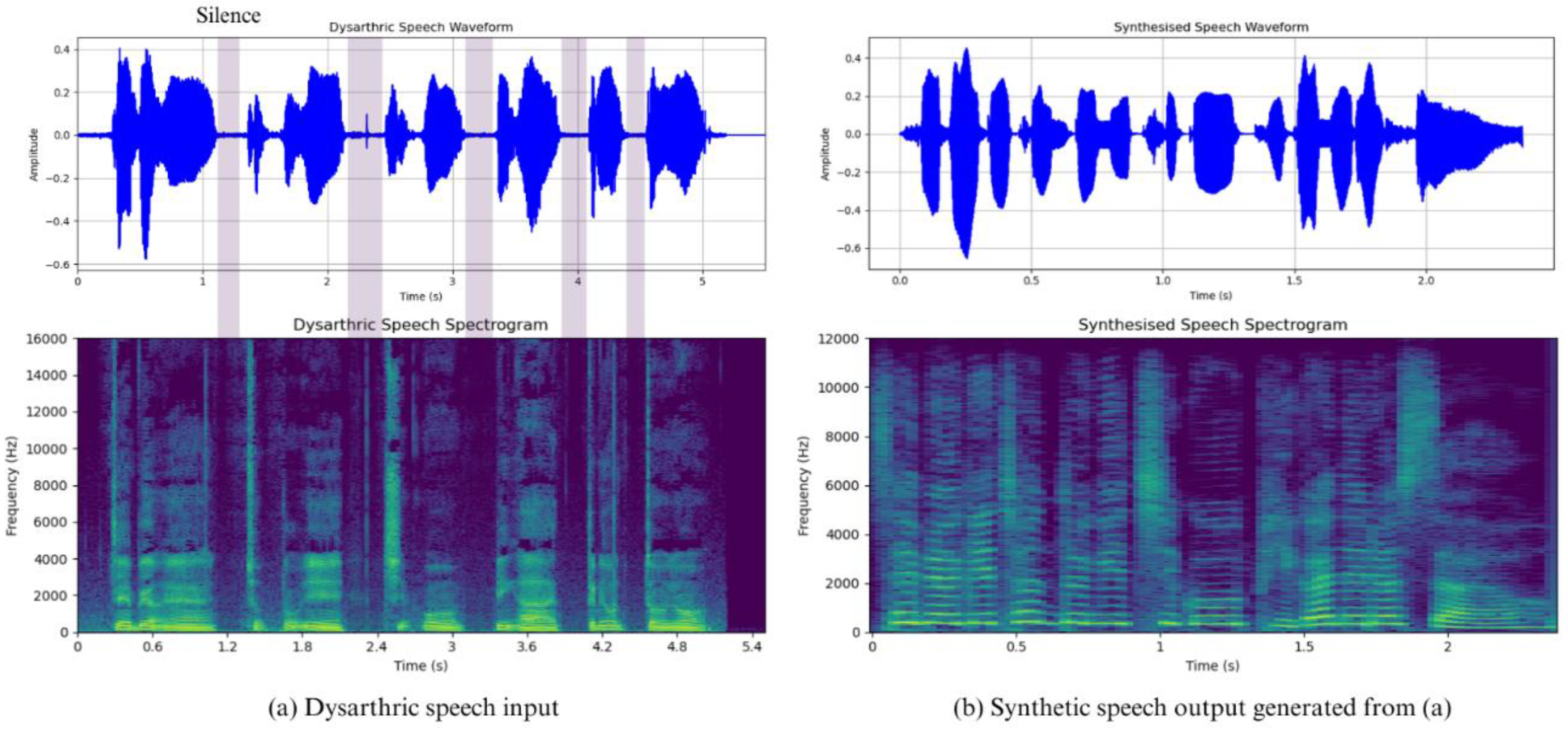

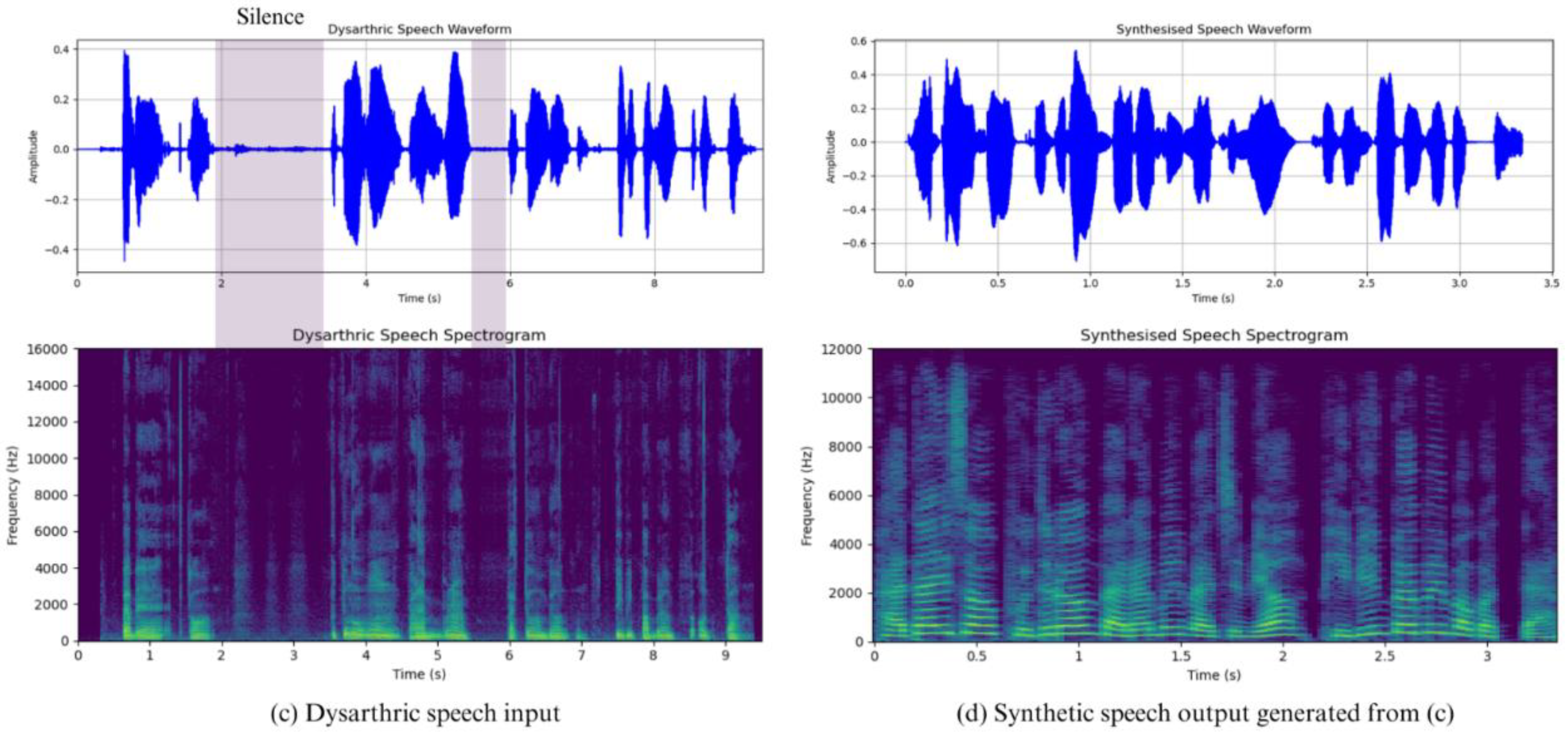

4.3. Integrated Communication Aid Systems

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Enderby, P. Disorders of communication: dysarthria. Handbook of Clinical Neurology 2013, 110, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.-J.; Lee, H.-J.; Park, K.-Y.; Lee, J.-S. A survey of speech sound disorders in clinical settings. Communication Sciences & Disorders 2015, 20, 133–144. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, J.L.; Hull, M.; Edwards, M.L. Preschool speech error patterns predict articulation and phonological awareness outcomes in children with histories of speech sound disorders. 2013.

- Rampello, L.; D'Anna, G.; Rifici, C.; Scalisi, L.; Vecchio, I.; Bruno, E.; Tortorella, G. When the word doesn't come out: A synthetic overview of dysarthria. Journal of the Neurological Sciences 2016, 369, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, A.D.; Yorkston, K.M. Communicative participation in dysarthria: Perspectives for management. Brain Sciences 2022, 12, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, L.C.; Hillis, A.E. Disorders of speech and language: aphasia, apraxia and dysarthria. Current Opinion in Neurology 2006, 19, 580–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selouani, S.-A.; Sidi Yakoub, M.; O'Shaughnessy, D. Alternative speech communication system for persons with severe speech disorders. EURASIP Journal on Advances in Signal Processing 2009, 2009, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, J.; McNaughton, D. Supporting the communication, language, and literacy development of children with complex communication needs: State of the science and future research priorities. Assistive Technology 2012, 24, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Judge, S. The Design of Voice Output Communication Aids; Ph.D. Thesis, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hawley, M.S.; Cunningham, S.P.; Green, P.D.; Enderby, P.; Palmer, R.; Sehgal, S.; O'Neill, P. A voice-input voice-output communication aid for people with severe speech impairment. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 2012, 21, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, M.; Singh, A.; Tang, H. The relationship between perceptual disturbances in dysarthric speech and ASR performance. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 2016, 140, EL416–EL422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z.; Xiao, K. A survey of automatic speech recognition for dysarthric speech. Electronics 2023, 12, 4278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharti, K.; Das, P.K. A survey on ASR systems for dysarthric speech. In Proceedings of the 2022 4th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Speech Technology (AIST), IEEE, 2022. Bhubaneswar, India, 9–11 December 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Jayaram, G.; Abdelhamied, K. Experiments in dysarthric speech recognition using artificial neural networks. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development 1995, 32, 162–162. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vachhani, B.; Bhat, C.; Kopparapu, S.K. Data augmentation using healthy speech for dysarthric speech recognition. Proceedings of Interspeech 2018, Hyderabad, India, 2–6 September 2018; pp. 471–475. [Google Scholar]

- Harvill, J.; Bejleri, A.; Arfath, M.; Das, D.; Thomas, S. Synthesis of new words for improved dysarthric speech recognition on an expanded vocabulary. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2021-2021 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Toronto, ON, Canada, 2021, 6–11 June 2021; IEEE; pp. 6428–6432. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Liu, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, P.; Meng, H. Exploiting visual features using Bayesian gated neural networks for disordered speech recognition. Proceedings of Interspeech 2019, Graz, Austria, 15–19 September 2019; pp. 4120–4124. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Du, J.; Dai, L.; Lee, C.-H. Robust audio-visual speech recognition using bimodal DFSMN with multi-condition training and dropout regularization. Proceedings of ICASSP 2019-2019 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Brighton, UK, 2019, 12–17 May 2019; IEEE; pp. 6570–6574. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.; Su, X.; Qian, Z. Multi-stage audio-visual fusion for dysarthric speech recognition with pre-trained models. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 2023, 31, 1912–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahamiri, S.R. Speech vision: An end-to-end deep learning-based dysarthric ASR system. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 2021, 29, 852–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almadhor, A.; Qaddoumi, A.; Al-Obaidi, S.; Al-Ali, K. E2E-DASR: End-to-end deep learning-based dysarthric ASR. Expert Systems with Applications 2023, 222, 119797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albaqshi, H.; Sagheer, A. Dysarthric speech recognition using convolutional recurrent neural networks. International Journal of Intelligent Engineering & Systems 2020, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Soleymanpour, M.; Karuppiah, S.; Narayanasamy, T. Synthesizing dysarthric speech using multi-speaker TTS for dysarthric speech recognition. Proceedings of ICASSP 2022-2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Singapore, 2022, 22–27 May 2022; IEEE; pp. 7382–7386. [Google Scholar]

- Baali, M.; Alami, M.; Amar, M.; Merzouk, R. Arabic dysarthric speech recognition using adversarial and signal-based augmentation. arXiv Preprint 2023, arXiv:2306.04368. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Chang, J.; Yun, S.; Kim, Y. Dysarthric speech database for universal access research. Proceedings of Interspeech 2008, Brisbane, Australia, 22–26 September 2008; pp. 1741–1744. [Google Scholar]

- Rudzicz, F.; Namasivayam, A.K.; Wolff, T. The TORGO database of acoustic and articulatory speech from speakers with dysarthria. Language Resources and Evaluation 2012, 46, 523–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dysarthric speech recognition data. Available online: https://aihub.or.kr/aihubdata/data/view.do?currMenu=115&topMenu=100&dataSetSn=608 (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Xiao, Z.; Liu, W.; Huang, L. Hybrid CTC-attention based end-to-end speech recognition using subword units. In Proceedings of the 2018 11th International Symposium on Chinese Spoken Language Processing (ISCSLP), Taipei, Taiwan, 2018, 26–29 November 2018; IEEE; pp. 146–150. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, S.; Hori, T.; Karita, S.; Hayashi, T.; Nishitoba, S.; Unno, Y.; Morita, K.; Kawakami, K.; Baskar, M.A.; Fujita, Y. ESPnet: End-to-end speech processing toolkit. arXiv Preprint 2018, arXiv:1804.00015. [Google Scholar]

- Bang, J.-U.; Kim, J.-S.; Yoon, J.-H.; Joo, S.-Y.; Lee, S.-M.; Cho, S.-K. Ksponspeech: Korean spontaneous speech corpus for automatic speech recognition. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 6936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karita, S.; Watanabe, S.; Chen, Z.; Hayashi, T.; Hori, T.; Inaguma, H.; Jiang, Z.; Someki, M.; Soplin, N.E.Y.; Yamamoto, R. A comparative study on transformer vs. In RNN in speech applications. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Automatic Speech Recognition and Understanding Workshop (ASRU), Sentosa, Singapore, 2019, 14–18 December 2019; IEEE; pp. 449–456. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, P.; Watanabe, S.; Kawahara, T.; Takeda, K. Recent developments on ESPnet toolkit boosted by conformer. Proceedings of ICASSP 2021-2021 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Toronto, ON, Canada, 2021, 6–11 June 2021; IEEE; pp. 5874–5878. [Google Scholar]

- Voita, E.; Talbot, D.; Moiseev, F.; Sennrich, R.; Titov, I. Analyzing multi-head self-attention: Specialized heads do the heavy lifting, the rest can be pruned. arXiv Preprint 2019, arXiv:1905.09418. [Google Scholar]

- Bebis, G.; Georgiopoulos, M. Feed-forward neural networks. IEEE Potentials 1994, 13, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, P.; Zoph, B.; Le, Q.V. Searching for activation functions. arXiv Preprint 2017, arXiv:1710.05941. [Google Scholar]

- Hannun, A.; Case, C.; Casper, J.; Catanzaro, B.; Cong, Y.; Fougner, C.; Han, T.; Kang, Y.; Krishnan, P.; Prenger, R.; Sengupta, S. Differentiable weighted finite-state transducers. arXiv Preprint 2020, arXiv:2010.01003. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, D.; Jung, S.; Kim, E. JETS: Jointly training FastSpeech2 and HiFi-GAN for end-to-end text-to-speech. arXiv Preprint 2022, arXiv:2203.16852. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Y.; Hu, C.; Tan, X.; Qin, T.; Zhao, S.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, T.-Y. FastSpeech 2: Fast and high-quality end-to-end text-to-speech. arXiv Preprint 2020, arXiv:2006.04558. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, J.; Kim, J.; Bae, J. HiFi-GAN: Generative adversarial networks for efficient and high fidelity speech synthesis. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, 33, 17022–17033. [Google Scholar]

- KSS Dataset: Korean Single Speaker Speech Dataset. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/dataset/speech-recognition (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Hayashi, T.; Yasuda, K.; Watanabe, S.; Higuchi, Y.; Takeda, K.; Kawahara, T. ESPnet-TTS: Unified, reproducible, and integratable open source end-to-end text-to-speech toolkit. Proceedings of ICASSP 2020-2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Barcelona, Spain, 2020, 4–8 May 2020; IEEE; pp. 7654–7658. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Pang, R.; Weiss, R.J.; Schuster, M.; Jaitly, N.; Yang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Skerrv-Ryan, R. Natural TTS synthesis by conditioning WaveNet on mel spectrogram predictions. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Calgary, AB, Canada, 2018, 15–20 April 2018; IEEE; pp. 4779–4783. [Google Scholar]

- Li, N.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Liu, M.; Zhou, L. Neural speech synthesis with transformer network. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Honolulu, HI, USA, 27 January–1 February 2019; pp. 6706–6713. [Google Scholar]

| Reference | Type | Method |

Speech Recognition Level |

Dataset | Performance (WRA) |

| Hawley et al. (2012) [10] | AAC | ASR + Message Reconstruction + TTS | Extremely limited Word Level |

Self-collection (English) |

96% (Restrict specific words) |

| Yu et al. (2023) [20] | ASR | Audio-Visual fusion framework (Audio + Motion images of faces) |

Word Level | UA-Speech (English) |

36% ~ 94% (Extremely Severe ~ Mild) |

| Shahamiri (2021) [21] | ASR | Spatial-CNN (Using Voicegram) |

Word Level | UA-Speech (English) |

64% |

| Almadhor et al. (2023) [22] | ASR | Spatial-CNN + Transformer (Using Voicegram) |

Word Level | UA-Speech (English) |

65% |

|

Hussain Albaqshi and Alaa Sagheer (2020) [23] |

ASR | CRNN (CNN + RNN) |

Word, Phrase, Sentence | Torgo (English) |

40% |

| Soleymanpour et al. (2022) [24] | TTS | Multi-Speaker TTS (Data augmentation) |

Word, Sentence | Torgo (English) |

59% ~ 61% |

| Baali et al. (2023) [25] | ASR | Wave GAN + Conformer (Data augmentation + ASR) |

Word, Sentence | Self-collection (Arabic), Torgo, LJspeech (English) |

82% |

| Model | CER (%) | WER (%) | ERR (%) |

| Hybrid CTC/attention transformer model [27] |

15.6 | 18.8 | 41.7 |

| Proposed conformer-based GTN-CTC model |

9.1 | 11.6 | 38.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).