Submitted:

03 December 2024

Posted:

03 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. Chemicals

2.3. Extraction and Sample Preparation

2.4. Anthocyanin Identification and Quantification

3. Results and Discussion

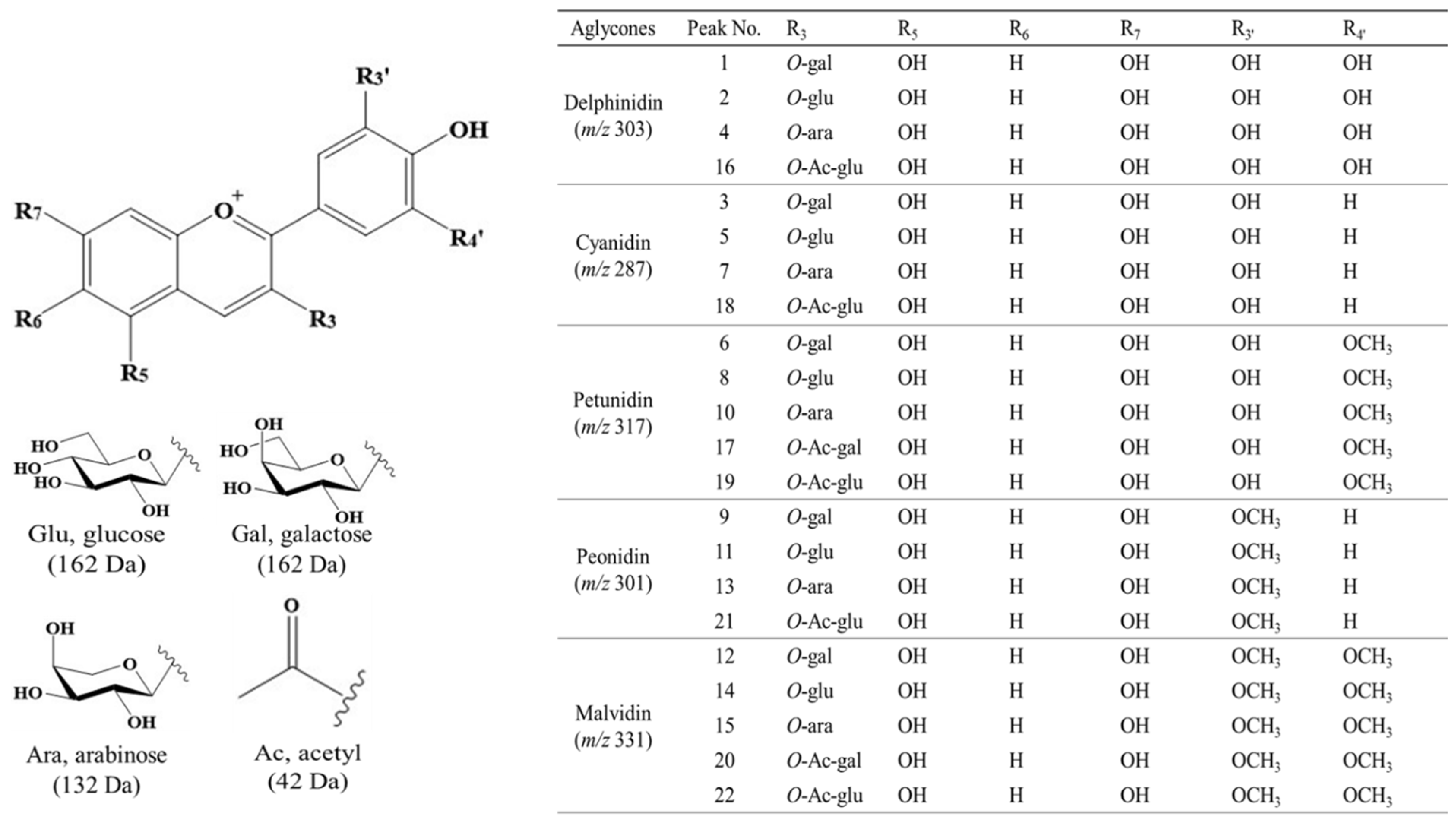

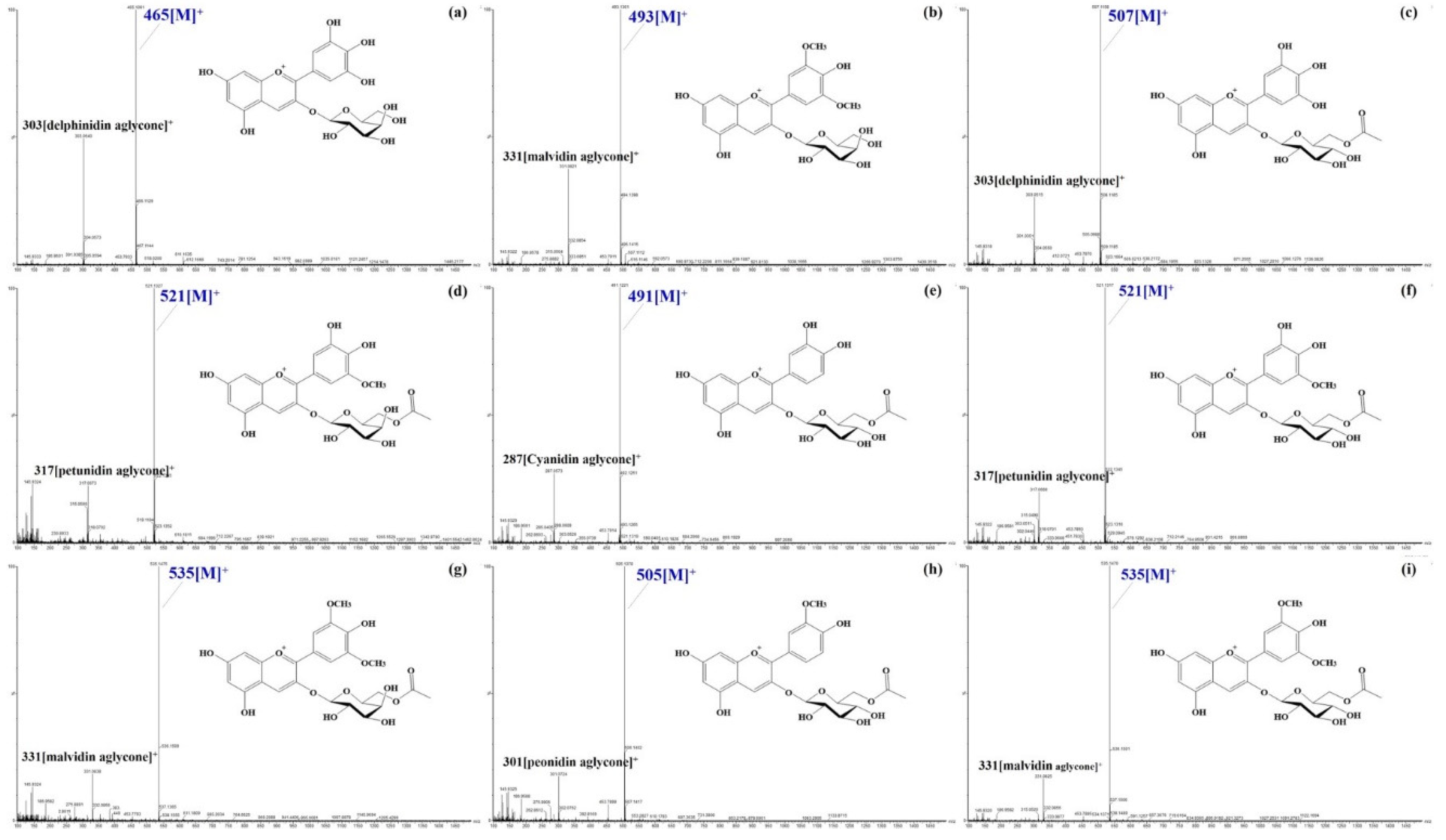

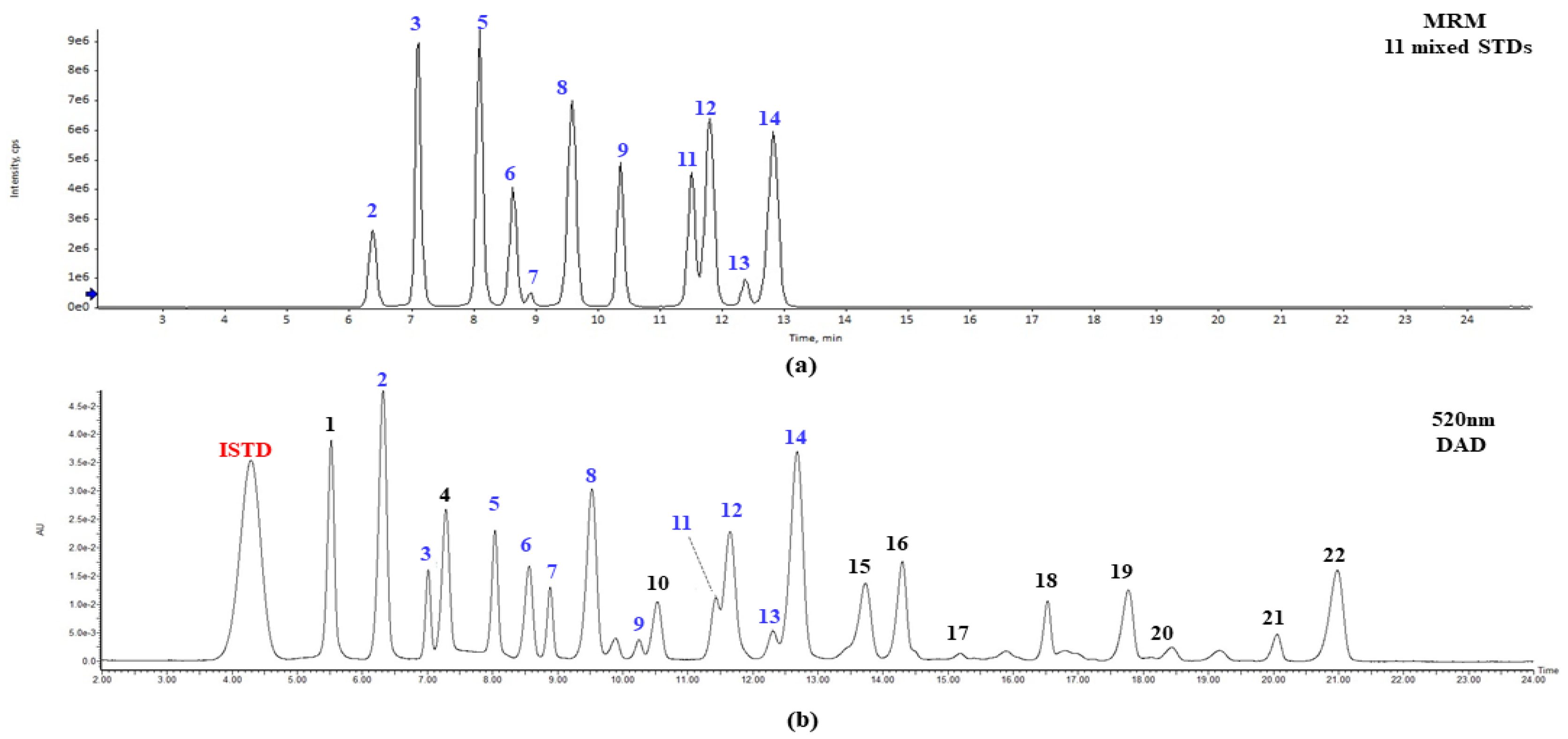

3.1. Identification of 22 Anthocyanin Glycosides from Blueberry Cultivars

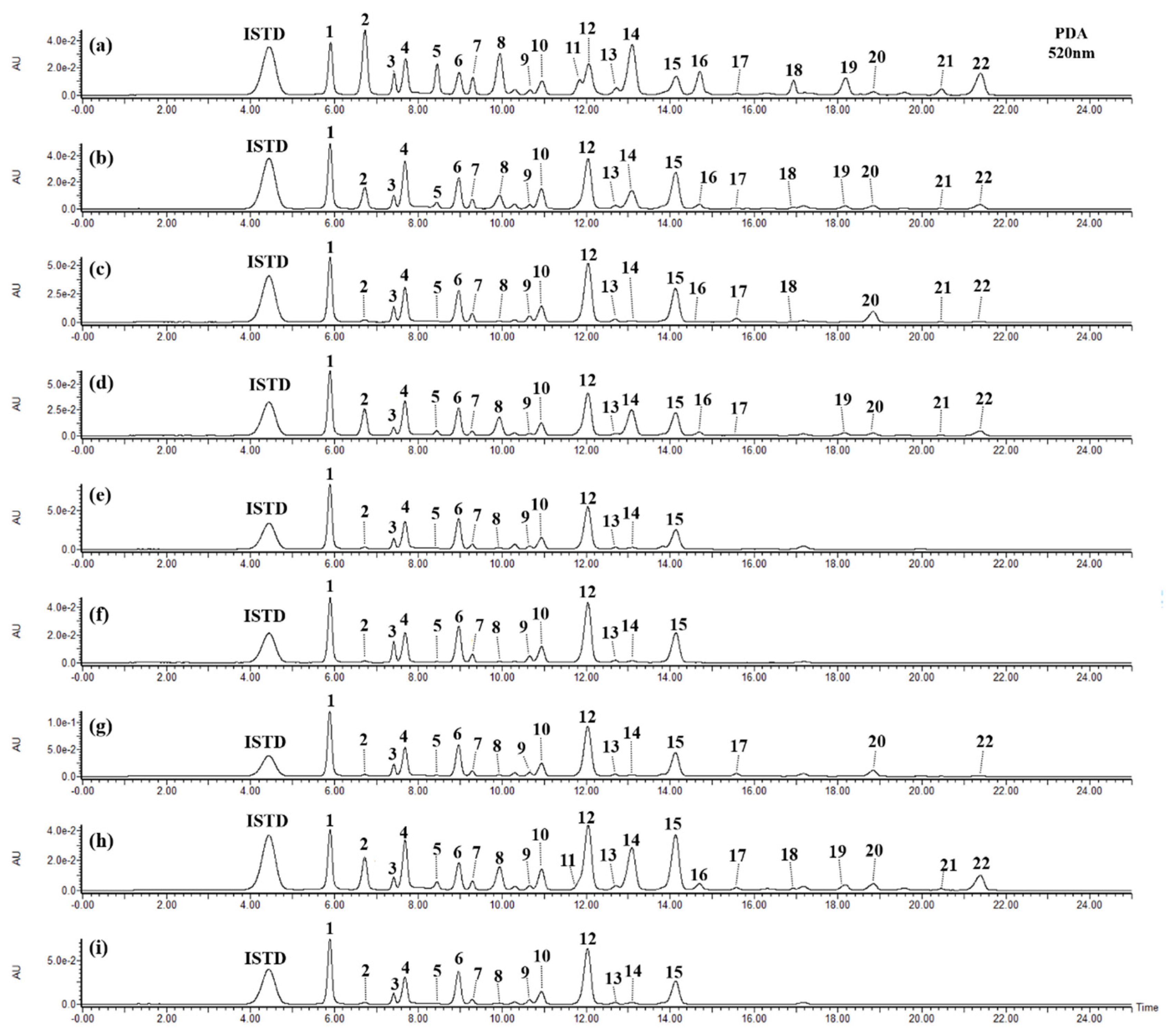

3.2. Variation in Anthocyanin Contents Depending on Highbush Blueberry Cultivars

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, J.G.; Ryou, M.S.; Jung, S.M.; Hwang, Y.S. Effects of cluster and flower thinning on yield and fruit quality in highbush ’Jersey’ blueberry. J. Bio-Env. Con. 2010, 19, 392–396. [Google Scholar]

- Kogan, C.; DeVetter, L.W.; Hoheisel, G.-A. Modeling northern Highbush blueberry cold hardiness for the Pacific Northwest. HortScience 2023, 11, 1314–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacalone, G.; Peano, C.; Guarinoni, A.; Beccaro, G.; Bounous, G. Ripening curve of early, midseason and late maturing highbush blueberry cultivars. In VII International Symposium on Vaccinium Culture 2000, 574, 119–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baenas, N.; Ruales, J.; Moreno, D.A.; Barrio, D.A.; Stinco, C.M.; Martinez-Cifuentes, G.; Melendez-Martinez, A.J.; Garcia-Ruiz, A. Characterization of Andean blueberry in bioactive compounds, evaluation of biological properties, and in vitro bioaccessibility. Foods 2020, 9, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinonen, I.M.; Lehtonen, P.J.; Hopia, A.I. Antioxidant activity of berry and fruit wines and liquors. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998, 46, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeram, N.P.; Adams, L.S.; Zhang, Y.; Lee, R.; Sand, D.; Scheuller, H.S.; Heber, D. Blackberry, black raspberry, blueberry, cranberry, red raspberry, and strawberry extracts inhibit growth and stimulate apoptosis of human cancer cells in vitro. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 9329–9339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martineau, L.C.; Couture, A.; Spoor, D.; Benhaddou-Andaloussi, A.; Harris, C.; Meddah, B.; Leduc, C.; Burt, A.; Vuong, T.; Le, P.M.; Prentki, M.; Bennett, S.A.; Arnason, J.T.; Haddad, P.S. Anti-diabetic properties of the Canadian lowbush blueberry Vaccinium angustifolium Ait. Phytomedicine 2006, 13, 612–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gallegos, J.L.; Haskell-Ramsay, C.; Lodge, J.K. Effects of blueberry consumption on cardiovascular health in healthy adults: A cross-over randomised controlled trial. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornsek, S.M.; Ziberna, L.; Polak, T.; Vanzo, A.; Ulrih, N.P.; Abram, V.; Tramer, F.; Passamonti, S. Bilberry and blueberry anthocyanins act as powerful intracellular antioxidants in mammalian cells. Food Chem. 2012, 4, 1878–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kader, F.; Rovel, B.; Girardin, M.; Metche, M. Fractionation and identification of the phenolic compounds of Highbush blueberries (Vaccinium corymbosum, L.). Food Chem. 1995, 55, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldo, A.R.; Cavallini, E.; Jia, Y.; Moss, S.M.A.; McDavid, D.A.J.; Hooper, L.C.; Robinson, S.P.; Tornielli, G.B.; Zenoni, S.; Ford, C.M.; Boss, P.K.; Walker, A.R. A Grapevine anthocyanin acyltransferase, transcriptionally regulated by VvMYBA, can produce most acylated anthocyanins present in grape skins. Plant Physiol. 2015, 169, 1897–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kähkönen, M.P.; Heinämäki, J.; Ollilainen, V.; Heinonen, M. Berry anthocyanins: isolation, identification and antioxidant activities. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2003, 14, 1403–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, J.S.; Nguyen, H.P.; Shen, S.; Schug, K.A. General method for extraction of blueberry anthocyanins and identification using high performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-ion trap-time of flight-mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2009, 1216, 4728–4735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinardi, A.; Cola, G.; Gardana, C.S.; Mignani, I. Variation of anthocyanin content and profile throughout fruit development and ripening of highbush blueberry cultivars grown at two different altitudes. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smrke, T.; Veberic, R.; Hudina, M.; Stamic, D.; Jakopic, J. Comparison of highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.) under ridge and pot production. Agriculture 2021, 11, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Z.; Herrera-Balandrano, D.D.; Yu, H.; Beta, T.; Zeng, Q.; Zhang, X.; Tian, L.; Niu, L.; Huang, W. A comparative analysis on the anthocyanin composition of 74 blueberry cultivars from China. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2021, 102, 104051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Cruz, A.A.; Hilbert, G.; Rivière, C.; Mengin, V.; Ollat, N.; Bordenave, L.; Decroocq, S.; Delaunay, J.-C.; Delrot, S.; Mérillon, J.-M.; Monti, J.-P.; Gomes, E.; Richard, T. Anthocyanin identification and composition of wild Vitis spp. accessions by using LC–MS and LC–NMR. Anal. Chim. Acta 2012, 732, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, V.V.d.; Hillebrand, S.; Montilla, E.C.; Bobbio, F.O.; Winterhalter, P.; Mercadante, A.Z. Determination of anthocyanins from acerola (Malpighia emarginata DC.) and açai (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) by HPLC–PDA–MS/MS. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2008, 21, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, R.L.; Lazarus, S.A.; Cao, G.; Muccitelli, H.; Hammerstone, J.F. Identification of procyanidins and anthocyanins in blueberries and cranberries (Vaccinium spp.) using high-performance liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 1270–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, W.; Sun, S.; Wang, J.; Zhu, J.; Liang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, G. Quantitative analysis of anthocyanins in grapes by UPLC-Q-TOF MS combined with QAMS. Separations 2022, 9, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, R.H.; Kim, H.-W.; Lee, S.; Lee, S.-J.; Na, H.; Kim, J.H.; Wee, C.-D.; Yoo, S.M.; Lee, S.H. Isoflavone characterization in soybean seed and fermented products based on high-resolution mass spectrometry. J. Korean Soc. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 50, 950–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-J.; Kim, H.-W.; Lee, S.; Na, H.; Kwon, R.H.; Kim, J.H.; Yoon, H.; Choi, Y.-M.; Wee, C.-D.; Yoo, S.M.; Lee, S.H. Characterization of isoflavones from seed of selected soybean (Glycine max L.) resources using high-resolution mass spectrometry. Korean J. Food Nutr. 2020, 33, 655–665. [Google Scholar]

- Cardenosa, V.; Girones-Vilaplana, A.; Muriel, J.L.; Moreno, D.A.; Moreno-Rojas, J.M. Influence of genotype, cultivation system and irrigation regime on antioxidant capacity and selected phenolics of blueberries (Vaccinium corymbosum L.). Food Chem. 2016, 202, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakajima, J.-i.; Tanaka, I.; Seo, S.; Yamazaki, M.; Saito, K. LC/PDA/ESI-MS profiling and radical scavenging activity of anthocyanins in various berries. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2004, 2004, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouari, Y.E.; Migalska-Zalas, A.; Arof, A.K.; Sahraoui, B. Computations of absorption spectra and nonlinear optical properties of molecules based on anthocyanidin structure. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2015, 47, 1091–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-K.; Kim, H.-W.; Lee, S.-H.; Kim, Y.J.; Jang, H.-H.; Jung, H.-A.; Hwang, Y.-J.; Choe, J.-S.; Kim, J.-B. Compositions and contents anthocyanins in blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.) varieties. Korean J. Environ. Agric. 2016, 35, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.N.; Shipley, P.R. Determination of anthocyanins in cranberry fruit and cranberry fruit products by high-performance liquid chromatography with ultraviolet detection: Single-laboratory validation. J. AOAC Int. 2011, 94, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Prior, R.L. Systematic identification and characterization of anthocyanins by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS in common foods in the United States: Fruits and Berries. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 2589–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.J.; Howard, L.R.; Prior, R.L.; Clark, J.R. Flavonoid glycosides and antioxidant capacity of various blackberry, blueberry and red grape genotypes determined by high-performance liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2004, 84, 1771–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Meng, X.; Li, B. Profiling of anthocyanins from blueberries produced in China using HPLC-DAD-MS and exploratory analysis by principal component analysis. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2016, 47, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.W.; Yu, D.J.; Lee, H.J. Changes in anthocyanidin and anthocyanin pigments in highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum cv. Bluecrop) fruits during ripening. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2016, 57, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.S.; Kwak, I.A.; Lee, S.G.; Cho, H.-S.; Cho, Y.-S.; Kim, D.-O. Influence of production systems on phenolic characteristics and antioxidant capacity of highbush blueberry cultivars. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 2949–2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovanelli, G.; Buratti, S. Comparison of polyphenolic composition and antioxidant activity of wild Italian blueberries and some cultivated varieties. Food Chem. 2009, 112, 903–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, B.; Dong, K.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Sun, H. Identification and quantification of anthocyanins of 62 blueberry cultivars via UPLC-MS. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2022, 36, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latti, A.K.; Kainulainen, P.S.; Hayirlioglu-Ayaz, S.; Ayaz, F.A.; Riihinen, K.R. Characterization of anthocyanins in Caucasian blueberries (Vaccinium arctostaphylos L.) native to Turkey. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 5244–5249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tao, C.; Liu, M.; Pan, Y.; Lv, Z. Effect of temperature and pH on stability of anthocyanin obtained from blueberry. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2018, 12, 1744–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubi, B.E.; Honda, C.; Bessho, H.; Kondo, S.; Wada, M.; Kobayashi, S.; Moriguchi, T. Expression analysis of anthocyanin biosynthetic genes in apple skin: Effect of UV-B and temperature. Plant Sci. 2006, 170, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; He, Y.N.; Yue, T.X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.W. Effects of climatic conditions and soil properties on Cabernet Sauvignon berry growth and anthocyanin profiles. Molecules 2014, 19, 13683–13703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, A.M.; Luby, J.J.; Tong, C.B.S.; Finn, C.E.; Hancock, J.F. Genotypic and environmental variation in antioxidant activity, total phenolic content, and anthocyanin content among blueberry cultivars. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2002, 127, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Mazza, G. Quantitation and distribution of simple and acylated anthocyanins and other phenolics in blueberries . J. Food Sci. 1994, 59, 1057–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overall, J.; Bonney, S.A.; Wilson, M.; Beermann, A.; Grace, M.H.; Esposito, D.; Lila, M.A.; Komarnytsky, S. Metabolic effects of berries with structurally diverse anthocyanins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gui, H.; Dai, J.; Tian, J.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, G.; Song, B.; Wang, M.; Saiwaidoula, M.; Dong, W.; Li, B. The isolation of anthocyanin monomers from blueberry pomace and their radical-scavenging mechanisms in DFT study. Food Chem. 2023, 418, 135872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trikas, E.D.; Melidou, M.; Papi, R.M.; Zachariadis, G.A.; Kyriakidis, D.A. Extraction, separation and identification of anthocyanins from red wine by-product and their biological activities. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 25, 548–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cultivar | Harvest season | Species |

|---|---|---|

| Reka | Early | northern highbush |

| Hannah’s choice | Early | northern highbush |

| Spartan | Early | northern highbush |

| Draper | Early | northern highbush |

| Patriot | Early | northern highbush |

| Legacy | Mid | northern highbush |

| Suziblue | Early | southern highbush |

| Farthing | Early | southern highbush |

| Newhanover | Mid | southern highbush |

| No. | Compound name | Formula | RT1) (min) |

Precursor ion (m/z) |

Product ion (m/z) |

DP (V)2) | CE (V)3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Delphinidin 3-O-glucoside (mirtillin) | C25H21O12+ | 6.36 | 465 | 303 | 86 | 29 |

| 3 | Cyanidin 3-O-galactoside (ideain) | C21H21O11+ | 7.09 | 449 | 287 | 86 | 33 |

| 5 | Cyanidin 3-O-glucoside (asterin) | C21H21O11+ | 8.08 | 449 | 287 | 31 | 39 |

| 6 | Petunidin 3-O-galactoside | C22H23O12+ | 8.62 | 479 | 317 | 86 | 35 |

| 7 | Cyanidin 3-O-arabinoside | C20H19O10+ | 8.87 | 419 | 287 | 236 | 27 |

| 8 | Petunidin 3-O-glucoside | C22H23O12+ | 9.57 | 479 | 317 | 86 | 31 |

| 9 | Peonidin 3-O-galactoside | C22H23O11+ | 10.35 | 463 | 301 | 20 | 33 |

| 11 | Peonidin 3-O-glucoside | C22H23O11+ | 11.50 | 463 | 301 | 20 | 33 |

| 12 | Malvidin 3-O-galactoside (primulin) | C22H25O12+ | 11.79 | 493 | 331 | 11 | 35 |

| 13 | Peonidin 3-O-arabinoside | C21H21O10+ | 12.36 | 433 | 301 | 104 | 33 |

| 14 | Malvidin 3-O-glucoside (enin) | C22H25O12+ | 12.81 | 493 | 331 | 16 | 37 |

| Compound name | Regression equation | Correlation coefficient1) (R2) | LOD2) (µg/mL) |

LOQ3) (µg/mL) |

Precision RSD (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| intraday (n = 6) |

interday(n = 6) | |||||

| Delphinidin 3-O-glucoside | Y = 1779297.1511X + 9835.2387 | 0.9999 | 0.0025 | 0.0076 | 1.83 | 6.54 |

| Cyanidin 3-O-galactoside | Y = 2178374.9200X + 25655.6942 | 1.0000 | 0.0026 | 0.0080 | 0.50 | 5.63 |

| Cyanidin 3-O-glucoside | Y = 3597678.5489X + 27299.5857 | 1.0000 | 0.0030 | 0.0091 | 0.03 | 5.27 |

| Petunidin 3-O-galactoside | Y = 1184176.7790X + 8718.2247 | 0.9998 | 0.0011 | 0.0033 | 5.90 | 4.34 |

| Cyanidin 3-O-arabinoside | Y = 532110.7X + 5725.4070 | 0.9999 | 0.0039 | 0.0117 | 0.50 | 1.96 |

| Petunidin 3-O-glucoside | Y = 2320782.4X + 22315.0959 | 0.9999 | 0.0017 | 0.0053 | 0.03 | 3.42 |

| Peonidin 3-O-galactoside | Y = 1537207.3321X + 46.9756 | 0.9999 | 0.0035 | 0.0106 | 5.43 | 3.21 |

| Peonidin 3-O-glucoside | Y = 1639444.6549X + 6829.8984 | 0.9999 | 0.0035 | 0.0105 | 0.49 | 4.57 |

| Malvidin 3-O-galactoside | Y = 3097011.3147X + 49762.1926 | 0.9998 | 0.0042 | 0.0128 | 0.03 | 3.31 |

| Peonidin 3-O-arabinoside | Y = 817530.9732X + 15169.9675 | 0.9998 | 0.0028 | 0.0085 | 6.69 | 3.84 |

| Malvidin 3-O-glucoside | Y = 3094396.6155X + 62198.3776 | 0.9998 | 0.0017 | 0.0051 | 0.49 | 3.95 |

| Peak No. |

RT (min) |

Compound name | Formula | Experimental ion (m/z, [M]+) | Error (ppm) 1) |

Product ions (m/z) | Species 2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5.99 | Delphinidin 3-O-galactoside | C21H21O12+ | 465.1022 | −1.2 | 465, 303 | a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i |

| 2 | 6.82 | Delphinidin 3-O-glucoside | C25H21O12+ | 465.1021 | −1.4 | 465, 303 | a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i |

| 3 | 7.52 | Cyanidin 3-O-galactoside | C21H21O11+ | 449.1080 | 0.4 | 449, 287 | a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i |

| 4 | 7.79 | Delphinidin 3-O-arabinoside | C20H19O11+ | 435.0922 | 0.0 | 435, 303 | a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i |

| 5 | 8.56 | Cyanidin 3-O-glucoside | C21H21O11+ | 449.1080 | 0.4 | 449, 287 | a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i |

| 6 | 9.09 | Petunidin 3-O-galactoside | C22H23O12+ | 479.1184 | 0.0 | 479, 317 | a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i |

| 7 | 9.41 | Cyanidin 3-O-arabinoside | C20H19O10+ | 419.0975 | 0.5 | 419, 287 | a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i |

| 8 | 10.06 | Petunidin 3-O-glucoside | C22H23O12+ | 479.1185 | 0.2 | 479, 317 | a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i |

| 9 | 10.79 | Peonidin 3-O-galactoside | C22H23O11+ | 463.1270 | 0.5 | 463, 301 | a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i |

| 10 | 11.08 | Petunidin 3-O-arabinoside | C21H21O11+ | 449.1078 | −0.1 | 449, 317 | a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i |

| 11 | 11.98 | Peonidin 3-O-glucoside | C22H23O11+ | 463.1234 | −0.2 | 463, 301 | e, g |

| 12 | 12.20 | Malvidin 3-O-galactoside | C22H25O12+ | 493.1337 | −0.7 | 493, 331 | a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i |

| 13 | 12.85 | Peonidin 3-O-arabinoside | C21H21O10+ | 433.1133 | 0.9 | 433, 301 | a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i |

| 14 | 13.25 | Malvidin 3-O-glucoside | C22H25O12+ | 493.1342 | 0.3 | 493, 331 | a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i |

| 15 | 14.30 | Malvidin 3-O-arabinoside | C22H23O11+ | 463.1235 | 0.0 | 463, 331 | a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i |

| 16 | 14.88 | Delphinidin 3-O-(6’‘-O-acetyl)glucoside | C23H23O13+ | 507.1135 | 0.4 | 507, 303 | a, b, c, e, g |

| 17 | 15.78 | Petunidin 3-O-(6’‘-O-acetyl)galactoside | C24H25O13+ | 521.1292 | 0.4 | 521, 317 | a, b, c, e, g, i |

| 18 | 17.13 | Cyanidin 3-O-(6’‘-O-acetyl)glucoside | C23H23O12+ | 491.1187 | 0.6 | 491, 287 | a, b, c, e, g |

| 19 | 18.39 | Petunidin 3-O-(6’‘-O-acetyl)glucoside | C24H25O13+ | 521.1292 | 0.4 | 521, 317 | a, b, c, e, g |

| 20 | 19.06 | Malvidin 3-O-(6’‘-O-acetyl)galactoside | C25H27O13+ | 535.1449 | 0.5 | 535, 331 | a, b, c, e, g, i |

| 21 | 20.69 | Peonidin 3-O-(6’‘-O-acetyl)glucoside | C24H25O12+ | 505.1343 | 0.4 | 505, 301 | a, b, c, e, g |

| 22 | 21.62 | Malvidin 3-O-(6’‘-O-acetyl)glucoside | C25H27O13+ | 535.1448 | 0.3 | 535, 331 | a, b, c, e, g, i |

| Peak No. 1) | Anthocyanin content (mg/100 gdry weight) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reka | Hannah’s choice | Spartan | Suziblue | Farthing | Patriot | Draper | Legacy | New Hanover | |

| Early-season | Mid-season | ||||||||

| 1 | 86.7 ± 1.4d | 94.7 ± 1.8d | 123.4 ± 7.7c | 71.2 ± 2.1e | 119.7 ± 2.6c | 72.8 ± 2.5e | 164.4 ± 19.4b | 165.1 ± 3.1b | 200.4 ± 16.8a |

| 2* | 33.2 ± 1.9d | 4.1 ± 0.2e | 74.2 ± 2.2b | 49.0 ± 2.0c | 3.3 ± 1.3e | 110.0 ± 0.9a | 4.0 ± 0.6e | 4.8 ± 0.7e | 4.8 ± 0.4e |

| 3* | 10.7 ± 0.7fg | 14.8 ± 0.5de | 8.3 ± 0.1e | 9.0 ± 0.5ge | 12.2 ± 1.4ef | 17.0 ± 1.6c | 27.7 ± 3.0a | 16.2 ± 2.2cd | 22.8 ± 2.5b |

| 4 | 65.7 ± 0.9cd | 51.8 ± 0.9e | 71.1 ± 2.9bc | 59.5 ± 2.7d | 52.0 ± 1.5e | 49.4 ± 2.6e | 74.3 ± 6.7b | 74.4 ± 1.5b | 91.7 ± 7.4a |

| 5* | 5.4 ± 0.7b | 0.7 ± 0.2c | 6.9 ± 0.2b | 6.2 ± 0.5b | 0.4 ± 0.1c | 33.7 ± 2.3a | 0.7 ± 0.2c | 0.6 ± 0.2c | 0.6 ± 0.1c |

| 6* | 84.4 ± 3.7de | 102.7 ± 5.9d | 108.0 ± 1.5d | 73.8 ± 6.0ef | 127.8 ± 10.3c | 61.9 ± 0.3f | 159.4 ± 13.4b | 157.3 ± 14.6b | 193.6 ± 18.3a |

| 7* | 7.5 ± 0.8c | 7.3 ± 1.2c | 3.6 ± 0.3f | 6.0 ± 0.5de | 5.3 ± 0.4e | 13.2 ± 0.9a | 11.0 ± 0.1b | 7.0 ± 0.6cd | 10.6 ± 0.8b |

| 8* | 22.5 ± 2.1d | 2.8 ± 0.0e | 56.0 ± 1.0b | 38.6 ± 2.6c | 2.7 ± 0.1e | 72.1 ± 3.9a | 3.4 ± 0.1e | 3.8 ± 0.3e | 3.8 ± 0.3e |

| 9* | 5.0 ± 1.0ef | 8.6 ± 2.1b | 3.4 ± 0.1g | 4.5 ± 0.2f | 7.5 ± 1.1bc | 6.1 ± 0.3de | 11.2 ± 0.8a | 6.7 ± 0.6cd | 11.2 ± 1.0a |

| 10 | 35.4 ± 0.5d | 27.1 ± 0.5e | 32.8 ± 1.8d | 32.5 ± 1.8d | 27.8 ± 1.0e | 22.7 ± 1.3f | 42.6 ± 1.4b | 39.4 ± 0.8c | 47.5 ± 3.5a |

| 11* | 4.4 ± 0.7d | 1.0 ± 0.3e | 5.8 ± 0.6c | 7.7 ± 0.5b | 0.7 ± 0.1e | 23.1 ± 1.4a | 0.9 ± 0.2e | 0.8 ± 0.1e | 0.9 ± 0.1e |

| 12* | 103.5 ± 3.2d | 133.8 ± 11.7c | 121.8 ± 3.1cd | 120.9 ± 7.3cd | 157.9 ± 14.0b | 59.9 ± 3.7e | 177.9 ± 15.9b | 157.7 ± 13.1b | 238.1 ± 22.7a |

| 13* | 0.8 ± 0.5e | 2.2 ± 0.2c | NDf | 0.7 ± 0.1e | 1.5 ± 0.1d | 1.9 ± 0.1c | 2.2 ± 0.2b | 1.2 ± 0.1d | 2.7 ± 1.1a |

| 14* | 49.7 ± 2.6c | 3.9 ± 0.3d | 109.4 ± 7.9b | 110.5 ± 6.6b | 4.0 ± 0.4d | 140.9 ± 9.0a | 4.5 ± 0.3d | 4.7 ± 0.4d | 5.8 ± 0.4d |

| 15 | 85.1 ± 1.5c | 87.1 ± 1.7c | 78.7 ± 3.6d | 109.7 ± 5.8b | 76.4 ± 2.0d | 46.2 ± 3.4e | 111.1 ± 4.7b | 85.6 ± 0.5c | 133.2 ± 7.5a |

| 16 | 6.9 ± 0.1c | 0.9 ± 0.3d | 9.0 ± 0.5b | 9.0 ± 0.6b | NDd | 43.9 ± 2.8a | NDd | NDd | NDd |

| 17 | 1.4 ± 0.0e | 6.5 ± 0.4b | 1.7 ± 0.3de | 3.2 ± 0.1c | NDf | 2.1 ± 0.2d | NDf | NDf | 10.5 ± 0.9a |

| 18 | 2.3 ± 0.5b | 0.9 ± 0.1de | 1.3 ± 0.1cd | 2.0 ± 0.2bc | NDe | 21.0 ± 1.1a | NDe | NDe | NDe |

| 19 | 5.8 ± 0.4c | NDd | 9.8 ± 0.4b | 9.3 ± 0.6b | NDd | 36.0 ± 1.5a | NDd | NDd | NDd |

| 20 | 6.7 ± 0.2e | 26.9 ± 0.5b | 8.9 ± 0.3d | 11.8 ± 0.8c | NDf | 6.2 ± 0.3e | NDf | NDf | 31.6 ± 2.0a |

| 21 | 1.3 ± 0.0c | 0.7 ± 0.0d | 0.9 ± 0.1cd | 2.1 ± 0.2b | NDe | 11.2 ± 0.7a | NDe | NDe | NDe |

| 22 | 11.5 ± 0.0d | 2.7 ± 0.1e | 20.7 ± 0.5c | 34.0 ± 1.8b | NDf | 59.2 ± 3.9a | NDf | NDf | 1.9 ± 0.1e |

| Total anthocyanin |

635.9 ± 18.9d | 581.1 ± 23.8de | 855.5 ± 27.3bc | 771.1 ± 32.7c | 599.3 ± 12.5e | 910.4 ± 36.8ab | 795.3 ± 31.5c | 725.4 ± 36.8ab | 1011.7 ± 66.4a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).