1. INTRODUCTION

The growing global demand for petroleum has driven the expansion of the petroleum industry, now covering vast areas of soil in many countries. It is well known that the petroleum industry's activities are complex, starting with new crude oil deposit identification, exploitation, transportation, refining, storage, and distribution of petroleum products. Accidents can often occur at any stage of this technological chain, causing soil pollution with harmful effects on human health and other biotic components (Mustafa et al., 2015). Pollution caused by petroleum hydrocarbons occurs not only in the petroleum industry but also in other sectors that utilize petroleum products as an energy source or raw material (Ossai et al., 2020). Currently, soil pollution with petroleum hydrocarbons is among the most widespread and significant environmental issues worldwide. Petroleum hydrocarbons are a complex mixture of thousands of aliphatic and aromatic compounds with distinct physical and chemical properties (Stancu, 2020, 2023, 2024). Once petroleum hydrocarbons pollute the soil, they undergo various transformations over time: physical (e.g., evaporation, adsorption), chemical (e.g., reactions with environmental chemical elements), and biological (e.g., interaction with aerobic and anaerobic microbiota). These transformation processes contribute to the degradation of petroleum hydrocarbons and further environmental pollution (Ossai et al., 2020). Consequently, large areas of soil polluted with petroleum hydrocarbons have become unusable (Polyak et al., 2018). Lack of timely intervention on spills allows petroleum hydrocarbons to migrate through the soil, contaminating the groundwater. Due to the complexity of these contaminants, the effects on soil are complex. Pollution with petroleum hydrocarbons negatively impacts the soil's physical (e.g., texture, compaction, hydraulic conductivity), chemical (e.g., mineral content), and microbiological properties (Ossai et al., 2020). In contaminated soil, hydrocarbons significantly impact indigenous microorganisms, affecting their diversity, abundance, and functional roles. Many hydrocarbons suppress sensitive microbial populations and promote the growth of hydrocarbon-degrading microorganisms. As a result, hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria often dominate contaminated soils, whereas microorganisms involved in nutrient cycling (e.g., nitrogen-fixing bacteria) are adversely affected, disrupting the ecosystem processes (Das and Chandran, 2011; Al-Hawash et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2018; Ravi et al., 2022; Jia et al., 2023).

Remediation of petroleum-contaminated sites has become a global concern, aiming to limit negative impacts and restore affected soils. Several decontamination technologies have been developed, including physical, chemical, mechanical, and biological methods. Among these, biotechnologies are the most efficient, environmentally friendly, and cost-effective options used in many countries to treat soil contaminated with petroleum and petroleum products (Abena et al., 2019). Biotechnologies generally depend on microorganisms that efficiently degrade hydrocarbons, ultimately breaking them down into carbon dioxide and water (Das and Chandran, 2011; Al-Hawash et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2018; Chicca et al., 2022). Bioremediation of soils using microorganisms can be achieved through either in-situ or ex-situ treatment techniques, each with advantages and disadvantages. In-situ treatment occurs directly at the contaminated site, without excavating the soil. This method reduces costs and limits the release of pollutants into the atmosphere, though the processes are harder to control and often slower. In-situ treatment is generally suitable for sites with permeable soil. Ex-situ treatment involves removing contaminated soil for treatment at a bioremediation platform. While this method incurs higher costs, it offers faster and more easily controlled processes and can treat a wide range of pollutants. Several methods such as biostimulation, bioaugmentation, and composting can be applied in this case. Additionally, the application of microorganisms and nutrients, as well as oxygen supply through soil aeration, is easier in ex-situ treatment compared to in-situ treatment (Ossai et al., 2020).

Sewage sludge, a byproduct of municipal wastewater treatment, has emerged as a valuable resource in ecological restoration due to its high organic matter content, nutrients, and potential to improve soil structure. Traditionally considered a waste material, sewage sludge is now being repurposed for its capacity to rehabilitate degraded soils. The organic matter and nutrients present in sewage sludge can enhance soil fertility, stimulate microbial activity, and support plant growth, all of which are essential for recovering contaminated ecosystems (Kicińska et al., 2018; Rorat et al., 2019; Gielnik et al., 2021).

Petroleum contaminants frequently degrade the soil quality, disrupt plant growth, and hinder the natural recovery of ecosystems. The ecological restoration of such sites has become a critical focus in environmental restoration efforts, aimed at restoring health, biodiversity, and functionality of petroleum-contaminated soils. Understanding the interaction between petroleum pollutants and indigenous bacteria is essential for developing effective bioremediation strategies. This study aimed to assess the potential of using dehydrated sewage sludge from a wastewater treatment plant to enhance the bioremediation efficiency in petroleum-contaminated soil. The evolution of bioremediation parameters, along with the dynamics of indigenous hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria, was monitored using physicochemical and microbiological methods. Furthermore, geotechnical analyses were conducted to examine the influence of dehydrated sewage sludge on soil quality, assessing its potential for reuse as a filling material in the ecological restoration of petroleum-contaminated sites.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Bioremediation Experiment of Petroleum-Contaminated Soil Treated with Sewage Sludge

The bioremediation experiment was conducted in an area (Constanta County, Romania) highly contaminated with petroleum products. The petroleum-contaminated soil was collected from a depth range of 0.8 to 2 m. Untreated petroleum-contaminated soil was used as the control. The bioremediation experiment was conducted for three months and was initiated by mixing the petroleum-contaminated soil (denoted S) with dehydrated sewage sludge (denoted N), in different proportions: S1:N1 (1:1, v/v), S2:N1 (2:1, v/v), and S1:N2 (1:2, v/v) for each mixture forming a pile (biopile). A biopile formed only from the contaminated soil was used as a control. The dehydrated sewage sludge was collected from a wastewater treatment plant (Galați County, Romania). The experiment was conducted on a bioremediation platform, and during the three months at one-week intervals, the petroleum-contaminated soil treated with sewage sludge and the control soil contaminated was aerated by using an excavator. For microbiological and physico-chemical analyses, samples were collected in sterile containers and stored at 4°C for further analyses.

2.2. Physicochemical Analysis of Petroleum Products Contaminated Soil Treated with Sewage Sludge

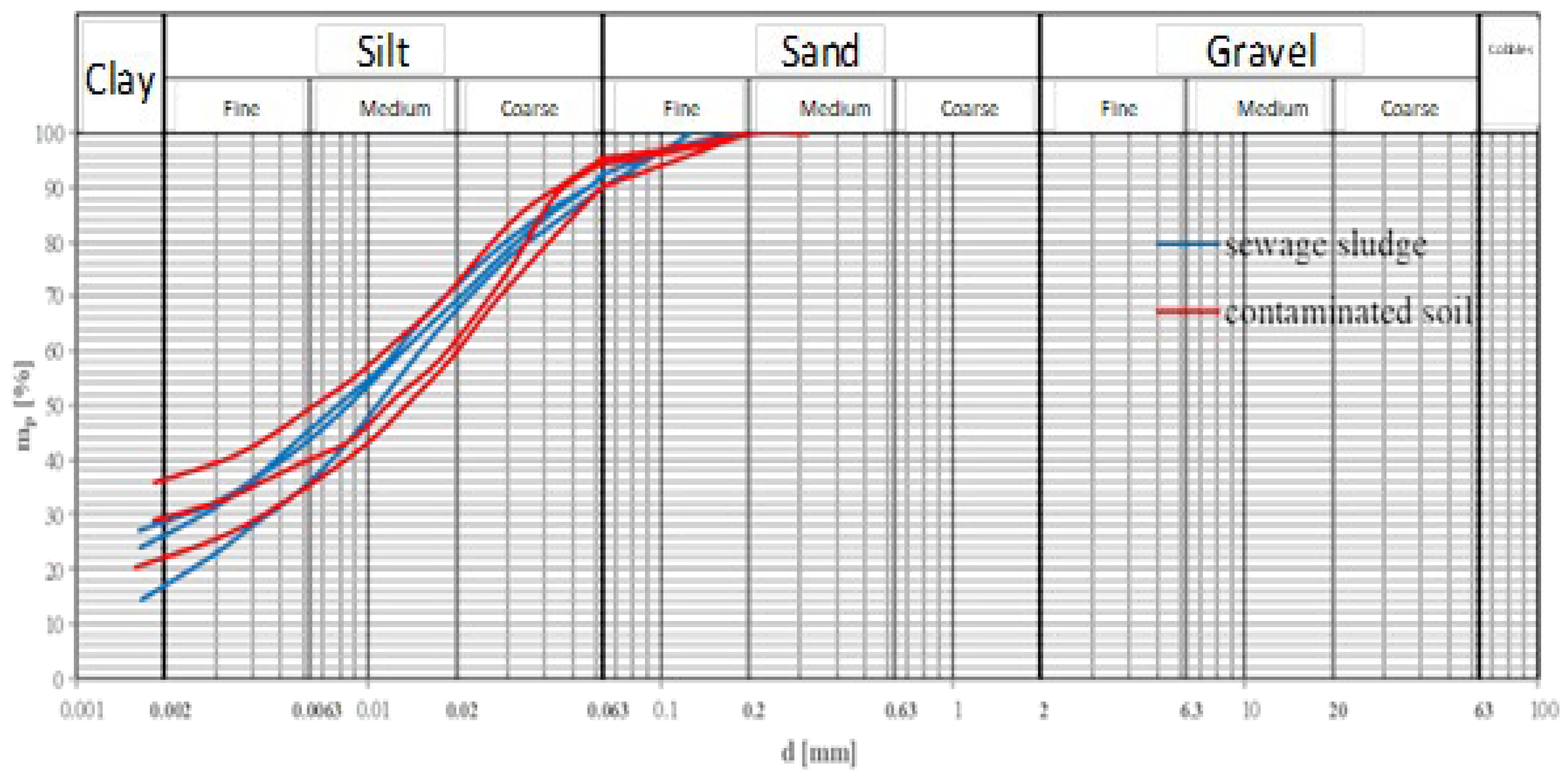

The moisture content of samples (triplicate) was determined by the oven-dry (at 105°C) method (Jia et al., 2023). The soil organic matter (SOM) content of samples was determined by using combustion (440°C, 6 hours) (ASTM D2974-20) and oxidation (20% hydrogen peroxide) methods (ISO 17892-4:2017; Satoh et al., 2023). The particle size distribution of the samples was determined by the combined method (sieving and sedimentation) (EN ISO 14688-1, 2018). The percentage distribution by grain fractions is graphically represented on a semi-logarithmic graph by the granulometric distribution curve and on a ternary plot.

Heavy metal concentrations in samples were determined using the inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) method (Simionov et al., 2023) by using a NexION 2000 ICP Mass Spectrometer. Oven-dried samples (at 80°C) were grounded and then sieved using a 2 mm to 0.25 mm sieve. The extracts for ICP-MS analysis were obtained by mineralization with HNO3 (65%) and H2O2 (30%), using a Milestone ETHOS EASY - Advanced Microwave Digestion System.

Total petroleum hydrocarbon (TPH) concentration in samples was determined through infrared spectroscopy (IR). Sample extracts were obtained by using S-316 solvent. After polar compounds removal (with activated aluminum oxide), non-polar compounds were determined by measuring the absorbance at a wavelength of 2930 cm-1, using an IR spectrometer InfraCal2, by the baseline method (Okparanma and Mouazen, 2013).

2.3. Enumeration and Isolation of Bacteria from Petroleum-Contaminated Soil Treated with Sewage Sludge

Samples were mixed (1:1 g/v) with phosphate buffer saline (PBS, Sambrook and Russel 2001) and incubated at room temperature on a rotary shaker (200 rpm) for one hour. Then, serial dilutions (10-1-10-12) were done in PBS. The pH of the samples was determined by using a Hanna pH 213 (Woonsocket, Rhode Island, USA).

The enumeration of the hydrocarbon-tolerant and hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria in the samples (initially, after two and three months of treatment) was performed through the most probable number (MPN) method (Stancu and Grifoll, 2011). Serial dilutions of each sample (10-1-10-12 in PBS) were inoculated into 96-multiwall plates containing LB (Sambrook and Russel, 2001) supplemented with 5% (v/v) diesel for hydrocarbon-tolerant bacteria enumeration and minimal medium (Stancu, 2023, 2024) supplemented with 5% (v/v) diesel for hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria enumeration. Multiwall plates were incubated for 1-14 days at 30°C. The viability of the bacteria (cell g-1 soil) was determined using 0.3% (w/v) triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC) dye as a redox indicator of cellular respiration as previously described by Stancu and Grifoll (2011).

The enumeration of the enterobacteria was performed through the plate count agar (PCA) method. Serial dilutions of the samples (10-1-10-6 in PBS) were inoculated onto EMB agar. Petri dishes were incubated for 1-5 days at 30°C. Then, the number of enterobacteria present per g of sample (cfu g-1 soil) was determined.

The hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria were isolated from the samples (initially, after two and three months of treatment) by the enrichment culture method. The samples (5% v/v) were used to initiate enrichment cultures in a liquid minimal medium (Stancu, 2023, 2024) supplemented with 5% (v/v) diesel as the sole carbon source. The tubes were incubated for 14 days on a rotary shaker (200 rpm) at 30°C. The obtained enrichment cultures (5% v/v) were then transferred into fresh minimal medium with 5% (v/v) diesel. The tubes were incubated under the same conditions for another 14 days. The isolated hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria were stored at -80°C in 25% (v/v) glycerol. The growth of the hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria was determined by measuring the optical density at 660 nm (OD660) and cell viability (Stancu, 2023, 2024) on LB agar and EMB agar. Biosurfactant production by isolated bacteria was studied by using the emulsification index, diesel overlay agar, and CTAB blue agar method as earlier described (Stancu, 2020, 2023, 2024). Diesel biodegradation by the isolated bacteria was established by diesel film fragmentation and by the determination of the free carbon dioxide (CO2 mg l-1) (Stancu, 2023).

2.4. Geotechnical Tests for Petroleum-Contaminated Soil Treated with Sewage Sludge

Normal Proctor tests were performed on the samples at the end of the bioremediation experiment using a normal Proctor hammer (manual) and a normal Proctor die to determine the degree of compaction (ASTM D698-12, 2021). To determine the deformability characteristics, samples (duplicate), with the highest dry density, obtained in the normal Proctor test, were loaded into the odometer by increasing (from 12.5 kPa to 500 kPa) the vertical stress (starting at a contact pressure of 12.5 kPa, following the loading steps of 50 kPa, 100 kPa, 200 kPa, 300 kPa and to 500 kPa). The deformation was measured (0.01 mm precision) after 24 hours for each loading step.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Bioremediation Experiment of Petroleum-Contaminated Soil Treated with Sewage Sludge

The bioremediation experiment was conducted in an area highly contaminated with petroleum products due to the existence in the past of an old deposit of petroleum products (e.g., oil, gasoline, light liquid fuel, and engine, and transmission oils). As we mentioned in the material and methods section, during the three months of the bioremediation experiment, at one-week intervals, the petroleum-contaminated soil treated or not with dehydrated sewage sludge was aerated by using an excavator (

Figure 1) to promote aerobic degradation. Generally, the bioremediation efficiency depends on various factors, like the geological and geographical characteristics of the petroleum-contaminated site, environmental conditions (e.g., pH, temperature, availability of nutrients and oxygen, contaminants bioavailability), and the native microbial community structure. Oxygen is the key electron acceptor in aerobic bioremediation, and, if it is not present in adequate concentrations, can significantly limit the biodegradation potential of aerobic microorganisms, including bacteria. In the absence of oxygen, the anaerobic degradation of petroleum hydrocarbons ensues at a slower rate than that of aerobic microbial degradation. Hence, providing adequate concentrations of oxygen in the contaminated soil is essential for higher biodegradation rates (Mekonnen et al., 2024).

3.2. Physicochemical Analysis of Petroleum Products Contaminated Soil Treated with Sewage Sludge

Before starting the bioremediation experiment, some physicochemical parameters (i.e., pH, humidity, organic matter, heavy metals, total petroleum hydrocarbon) of the soil contaminated with petroleum products and sludge were determined (

Table 1). The physicochemical parameters determined in this study are very important for the bioremediation process of soils contaminated with petroleum products and for the use of sludge in ecological remediation. As we mentioned in the introduction, sewage sludge represents an important source of both micronutrients and macronutrients, as well as of water that could have a positive effect on the activity of microorganisms that exist in the petroleum-contaminated soil (Chibuike and Obiora, 2014). Previously, it was reported that several parameters, such as pH (below 6.5), humidity (below 40%), high concentrations of hydrocarbons, and heavy metals, and low nutrients nutrient content (nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium) can limit the biodegradation process by inhibiting the development of bacteria capable of degrading hydrocarbons (Chibuike and Obiora, 2014; Castro et al., 2016; Patowary et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2018; Ravi et al., 2022; Jia et al., 2023).

At the initiation of the bioremediation experiment, both soil (pH 7.3) and sludge (pH 6.8) exhibited near-neutral

pH values (

Table 1). Soil contamination with petroleum products can significantly influence pH levels. Acidic compounds form in petroleum and their derivatives through chemical and/or biochemical oxidation, are reducing pH in the contaminated sites. In contrast, the presence of soil minerals, and salts of large organic acid molecules can undergo basic hydrolysis, raising pH levels in contaminated sites (Onojake et al., 2014).

The initial

moisture content of the soil was 19.06%, while the sludge exhibited a moisture content of 305% (

Table 1). Soil moisture is inherently variable, influenced by climatic conditions and petroleum contamination (Devatha et al., 2019). In contrast, sludge moisture content is determined by wastewater treatment processes and the organic matter content (Gui et al., 2021). The high moisture content of sewage sludge provides a significant advantage by reducing the requirement for additional water during the bioremediation process (Gielnik et al., 2021).

The

soil organic matter (SOM) content analyzed using combustion and oxidation methods. The results, detailed in

Table 1, show slight differences between the two methods, with values of 5.2% and 5.5% for soil and 38.2% and 39.3% for sludge, respectively. The combustion method yielded marginally lower values (0.3% for soil and 0.9% for sludge), likely due to water loss from clay mineral structures during heating and the water retention properties of organic matter (Bot and Benites, 2005). Despite these minor discrepancies, the combustion method is faster and provides reliable results.

The

particle size distribution of the petroleum-contaminated soil significantly affects the bioremediation process. For example, sandy soil due to its higher porosity, allows better oxygenation, enhancing bioremediation efficiency. In contrast, clay soils retain water and other substances, obstructing oxygen diffusion and slowing the bioremediation process (Mekonnen et al., 2024). Periodic soil aeration was used to maintain adequate oxygen levels in this study. The contaminated soil consisted of approximately 64% silt, 7% sand, and 29% clay, classifying it as silty clay or clayey silt. Similarly, the sludge contained 68% silt, 8% sand, and 24% clay, categorizing it as clayey silt or silty clay. Both materials showed overlapping particle size distribution curves, with slight variations in the clay fraction (

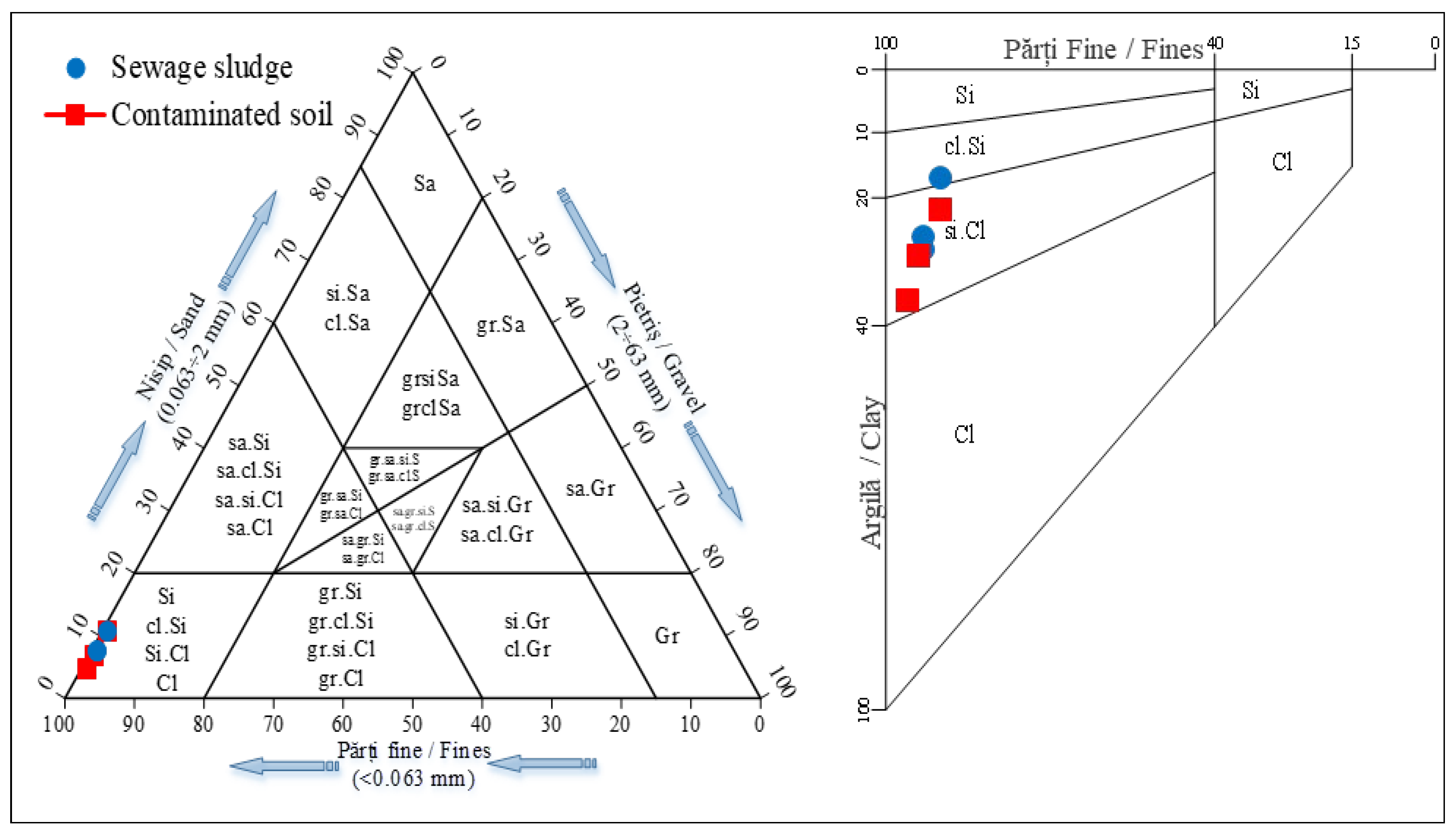

Figure 2). The ternary diagram (

Figure 3) further corroborates the similarity in granulometric composition.

The density of the mineral skeleton (ρS) is critical in determining soil porosity, void ratio, and pedotransfer functions. The mineral skeleton density for soil and sludge samples was determined as 2.662 g cm⁻³ and 2.674 g cm⁻³, respectively, consistent with the typical range for mineral soils (2.4 – 2.9 g cm⁻³) (Ruehlmann, 2020; Ruehlmann and Körschens, 2020).

Hence,

heavy metal concentrations in the soil and sludge were analyzed before initiating the bioremediation process (

Table 1). The results showed similar cadmium concentrations (<0.8 mg kg⁻¹ ds) in both samples and comparable nickel concentrations (26.1 mg kg⁻¹ ds in soil, 28.6 mg kg⁻¹ ds in sludge). However, concentrations of chromium (30.6 mg kg⁻¹ ds), copper (107 mg kg⁻¹ ds), lead (27.0 mg kg⁻¹ ds), and zinc (348 mg kg⁻¹ ds) were significantly higher in sludge than in soil, with the latter showing values of 19.9 mg kg⁻¹ ds, 21.6 mg kg⁻¹ ds, 12.2 mg kg⁻¹ ds, and 50 mg kg⁻¹ ds, respectively. The most pronounced difference was observed for zinc, with sludge concentrations exceeding soil levels by approximately seven-fold. Analyzing the values of the concentrations of heavy metals in the soil sample, it is found that only in the case of copper and nickel, exceedances slightly above the normal values are recorded, which means that the pollutants specific to the activity were not heavy metals. For the sludge sample, all the heavy metal concentration values exceed the normal values, and in the case of zinc and copper, some values exceed the normal values by 3.5 times and 5 times, respectively.

Total petroleum hydrocarbon (TPH) content is a key indicator of environmental pollution. The soil sample exhibited a TPH concentration of 4630 mg kg⁻¹ ds (

Table 1), approximately 50 times higher than the normal value, attributed to accidental petroleum and their derivative spills during warehouse operations. The sludge sample also contained significant petroleum hydrocarbons (3810 mg kg⁻¹ ds,

Table 1), likely originating from wastewater contamination from anthropogenic release of petroleum product pollutants.

3.3. Enumeration and Isolation of Bacteria from Petroleum-Contaminated Soil Treated with Sewage Sludge

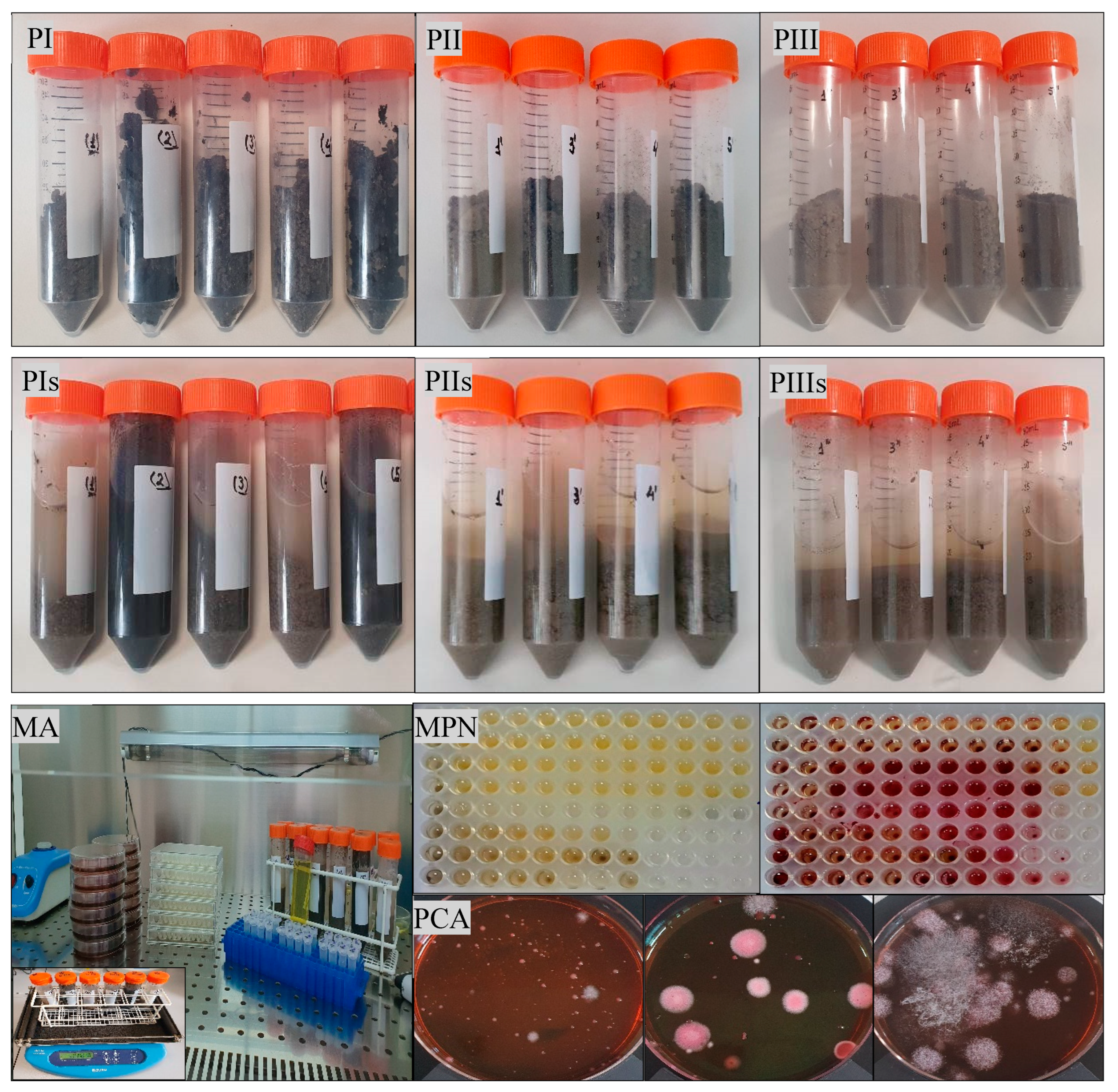

Microorganisms play a key role in sustaining soil ecological functions. Bioremediation of petroleum-contaminated soil by indigenous microorganisms is considered an efficient, environmentally friendly, and cost-effective technology, as compared with other physicochemical treatment methods. Bioremediation of the contaminated soils depends on the composition and concentration of petroleum, the presence of suitable microorganisms, and environmental factors (e.g., pH, temperature) (Al-Hawash et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2018; Chicca et al., 2022; Ravi et al., 2022). At the initiation of the bioremediation experiment, all analyzed samples had a neutral pH (6.8-7.3). The soil sample untreated with sludge (control) had a higher pH value (7.2-7.3), compared with those obtained for the soil samples treated for two and three months with sludge (pH 6.5-6.9). The pH can be highly variable in soils and should be taken into consideration when we try to improve the biological treatment methods in sites contaminated with petroleum hydrocarbons (Al-Hawash et al., 2018). The microorganisms that are frequently involved in the decontamination of petroleum-polluted soils are bacteria, fungi, and yeasts. Bacteria play the most important role in the bioremediation of petroleum-contaminated soils (Patowary et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2018; Ravi et al., 2022; Jia et al., 2023). In the soil samples treated or not with sludge (initially, after two and three months,

Figure 4), by using the most probable number (MPN) method we revealed the existence of hydrocarbon-tolerant and hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria, and by the plate culture method the existence of enterobacteria. The number of hydrocarbon-tolerant bacteria and hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria varied from one sample to another (10

4.-10

12 cell g

-1 soil) during the bioremediation experiment (

Table 2). In the samples collected at the beginning of the experiment, the number of hydrocarbon-tolerant bacteria was higher (10

11 cell g

-1), compared to the number of hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria (10

4-10

10 cell g

-1). Thus, not all bacteria existing in the samples could degrade petroleum hydrocarbons. In the samples collected after two months, the number of hydrocarbon-tolerant bacteria (10

11-10

12 cell g

-1) and the number of hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria (10

11 cell g

-1) had very close values. Most of the hydrocarbon-tolerant bacteria present in the analyzed samples were also capable of growing on a minimal medium in the presence of 5% diesel as a sole carbon source. In the samples collected after three months, the number of hydrocarbon-tolerant bacteria was higher (10

10.-10

11 cell g

-1), compared to the number of hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria (10

5 cell g

-1). The variations observed in the number of hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria in the analyzed samples are explainable because the number of these bacteria is higher when the concentration of petroleum hydrocarbons is high and subsequently decreases with the reduction of hydrocarbon contamination. Like in the case of the other two tested bacteria, the number of enterobacteria varied from one sample to another (0

.-10

6 ufc g

-1 soil) (

Table 2). In the samples collected at the initiation of the experiment, the number of enterobacteria was higher (10

4-10

5 ufc g

-1), compared with their numbers in samples collected after two and three months (0 cell g

-1). In the samples collected after two and three months, we observed the presence of filamentous fungi that are more resistant to stress conditions than other microorganisms. The presence of filamentous fungi in soils contaminated with petroleum hydrocarbons has a beneficial effect on bioremediation efficiency (Al-Hawash et al., 2018; Bidja Abena et al., 2020). Sometimes they were described as more efficient than bacteria in the degradation of high molecular weight hydrocarbons in contaminated soils (Chicca et al., 2022). Fungi such as

Aspergillus,

Penicillium, and

Graphium are microorganisms that can degrade persistent petroleum pollutants (Al-Hawash et al., 2018).

Using the enriched culture method, we isolated twelve hydrocarbon-degrading bacterial consortia from the petroleum-contaminated soil sample treated or not with sludge (

Figure 5,

Table 3). Consortia C1.1, C1.3, C1.4, C1.5 were isolated from samples collected at the initiation of the bioremediation experiment (PI), and consortia C2.1, C2.3, C2.4, C2.5 and C3.1, C3.3, C3.4, C3.5 were isolated from the samples collected after two (PII) and three (PIII) months, respectively. The growth of hydrocarbon-degrading bacterial consortia in the presence of 5% diesel as the sole carbon source varied from one sample to another (OD

660 0.58-0.97). In the samples collected at the beginning of the experiment, the growth of hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria was higher (DO

660 0.89-0.97), compared to the growth of these bacteria in the samples collected after two and three months (DO

660 0.58-0.82). No significant differences in hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria viability were observed from one sample to another. All the isolated hydrocarbon-degrading consortia showed very good viability (100%) on the LB agar supplemented or not with diesel. Furthermore, all these consortia showed very good viability also on EMB agar, a medium which is a selective culture medium used for the identification of Gram-negative bacteria, specifically enterobacteria. Our results prove that some of the hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria from the isolated consortia could belong to the Enterobacteriaceae.

We further investigate if the isolated bacterial consortia produced biosurfactants (

Table 3). Some of the bacterial consortia isolated from the samples collected at the initiation of the experiment (i.e., C1.1, C1.3) and from the samples collected after two months (C2.1, C2.3) produced a higher amount of biosurfactants (

E24 50-100%), compared to the rest of consortia (

E24 10%). These four bacterial consortia (C1.1, C1.3, C2.1, C2.3) gave a positive reaction when the diesel overlay agar assay was used as a screening method, confirming biosurfactant production. Moreover, five of the bacterial consortia (C1.3, C2.1, C2.3, C2.4, C3.5) gave a positive reaction when they were grown on CTAB blue agar, confirming biosurfactant production.

The biodegradation of diesel oil by hydrocarbon-degrading bacterial consortia was confirmed by breaking up the diesel film from the surface of the minimal liquid medium and by monitoring the free CO

2 (

Figure 5,

Table 3). All isolated consortia were able to break the diesel film when grown in a medium with a minimum of 5% diesel. The amount of free CO

2 released in the growth medium varied from one sample to another from 1416 to 1848 mg l

-1. Similar results were earlier reported by Stancu (2023) when different strains of the genera

Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter, Stenotrophomonas and

Bacillus were grown in a medium with a minimum of 3% diesel.

Pseudomonas along with other bacterial genera, such as

Achromobacter,

Acinetobacter,

Alcaligenes,

Arthrobacter,

Bacillus,

Burkholderia,

Corynebacterium,

Enterobacter,

Flavobacterium, Lysinibacillus, Micrococcus, and

Rhodococcus were reported to have a good ability to degrade petroleum hydrocarbons (Xu et al., 2018).

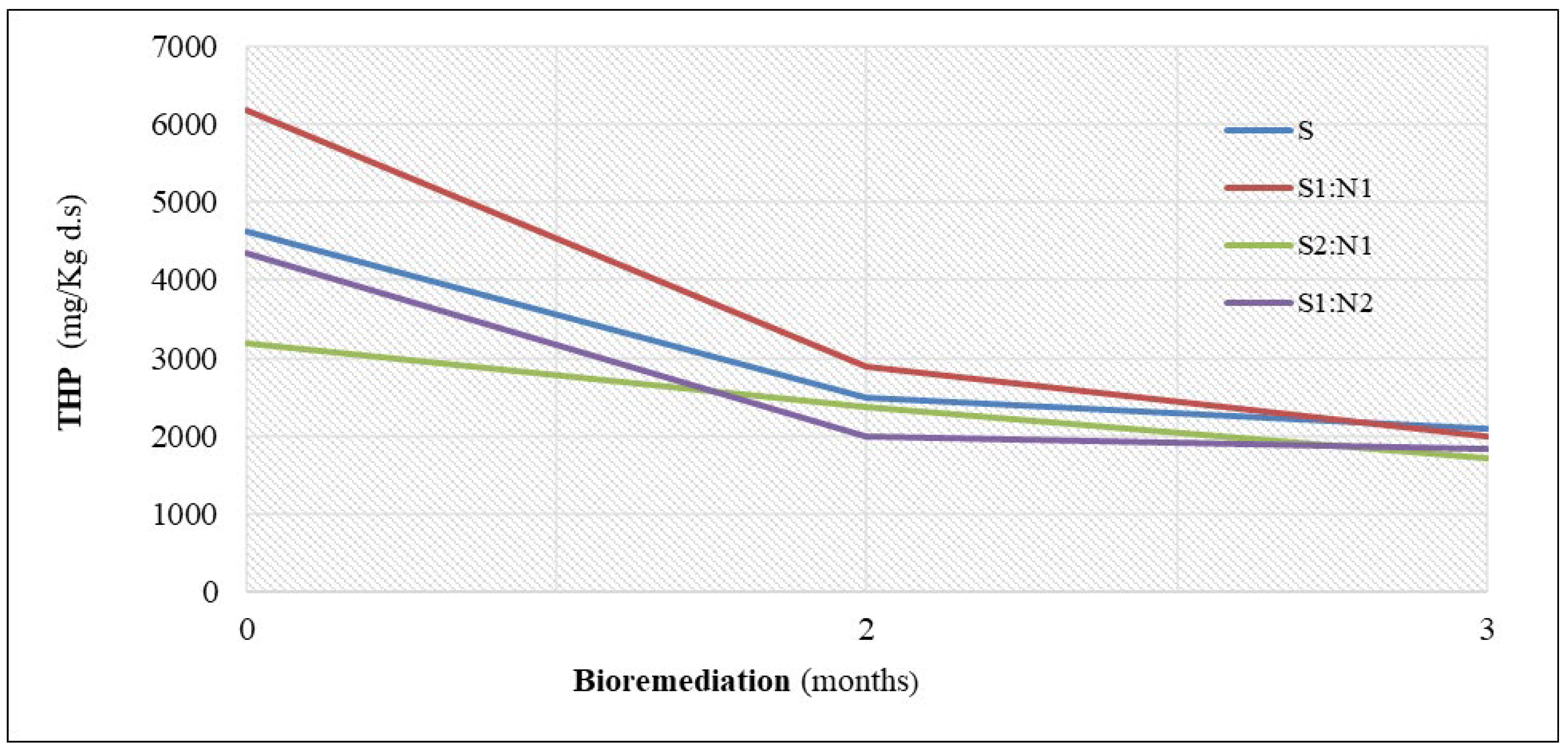

At the start of the bioremediation experiment, TPH concentrations varied from one sample to another (

Table 4,

Figure 6). The highest TPH concentration (6190 mg kg⁻¹ ds) was observed in the S1:N1 mixture, followed by S (4630 mg kg⁻¹ ds), S1:N2 (4350 mg kg⁻¹ ds), and the lowest in the S2:N1 mixture (3200 mg kg⁻¹ ds). A significant reduction in TPH concentrations occurred during the first two months. The largest decrease was recorded in the S1:N1 mixture (3290 mg kg⁻¹ ds), followed by S (2100 mg kg⁻¹ ds), S1:N2 (1970 mg kg⁻¹ ds), and S2:N1 (1200 mg kg⁻¹ ds). In the later stages of the experiment, TPH reduction slowed, with decreases observed in S1:N1 (900 mg kg⁻¹ ds), S1:N2 (540 mg kg⁻¹ ds), S (400 mg kg⁻¹ ds), and S2:N1 (290 mg kg⁻¹ ds). These findings indicate that mixtures with higher initial TPH concentrations exhibited greater reductions. Degradation rates were particularly high during the first two months, with approximately 80% reductions observed across mixtures, while the control soil exhibited a slightly higher rate of ~85%. In the last month, degradation rates decreased to approximately 20% for the mixtures and 15% for the control soil. The degradation rates over the entire period of the experiment are as follows: in the mixture S1:N1 (67.7%), followed in order by S1:N2 (58%), S (54.6%), S2:N1 (53.4%).

Heavy metal concentration varied from one sample to another in the bioremediation experiment (

Table 4). The sludge exhibited higher levels of heavy metals than the prepared mixtures (S1:N1, S2:N1, S1:N2), reflecting dilution effects in the mixtures. Throughout the bioremediation experiment, heavy metal concentrations in the mixtures remained relatively stable, with minor variations attributed to sampling and measurement uncertainties. The concentrations of chromium and lead in all mixtures remained below the normal allowable limits. Zinc concentrations in the S2:N1 mixture also fell within normal limits. However, for the other samples, concentrations of copper, nickel, and zinc exceeded normal levels but remained below regulated thresholds. Cadmium concentrations were consistently below the detection limit across all samples, indicating negligible presence. Heavy metal concentrations can negatively impact soil health, plant growth, and human health (Briffa et al., 2020; Swain, 2024). In bioremediation, excessive heavy metal concentrations inhibit the activity of hydrocarbon-degrading microorganisms, reducing biodegradation efficiency (Chibuike and Obiora, 2014).

3.4. Geotechnical Tests for Petroleum-Contaminated Soil Treated with Sewage Sludge

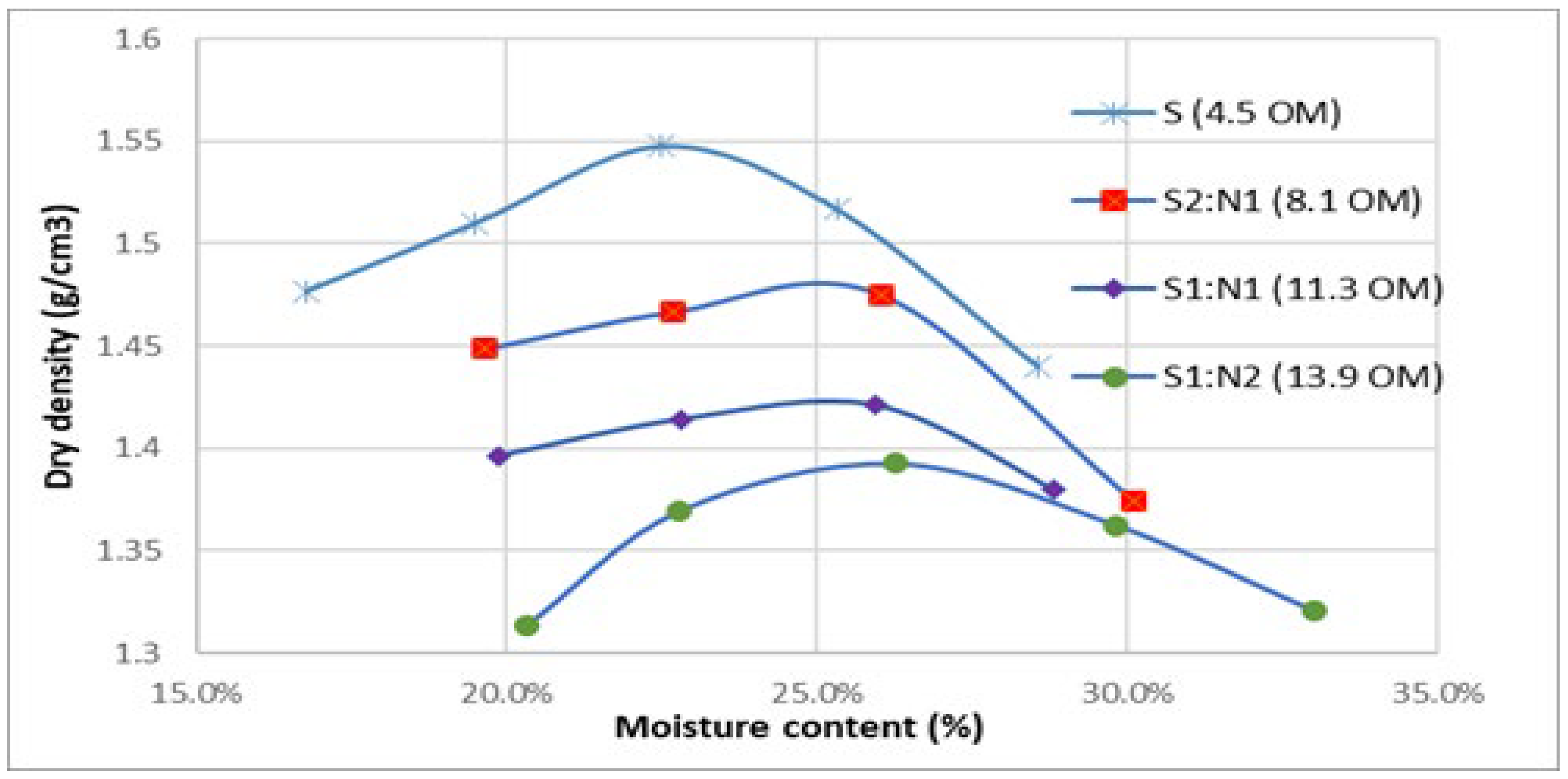

After the completion of the bioremediation process, it is necessary to know the geotechnical characteristics for the reintroduction of the bioremedied soils in the voids from which they were extracted by excavation. A key parameter in this context is the degree of compaction. The results of the compaction tests are presented graphically, with a curve plotted for each mixture to determine the maximum dry density and the optimal compaction moisture content under an energy of 0.6 J cm⁻³ (

Figure 7). The Proctor test results indicate a strong correlation between soil organic matter content, optimal compaction moisture, and maximum dry density. For soil with 4.5% organic matter, the maximum dry density and optimal compaction moisture were 1.55 g cm⁻³ and 22.5%, respectively. Similarly, for the S2:N1 mixture containing 8.1% organic matter, the values were 1.48 g cm⁻³ and 25%, and for S1:N2 with 13.9% organic matter, the corresponding values were 1.42 g cm⁻³ and 25.8%. As the organic matter content increased, the maximum dry density decreased, while the optimal compaction moisture content increased. This trend aligns with the known properties of organic matter, which retains significant moisture and exhibits a lower density compared to mineral particles (Gui et al., 2021).

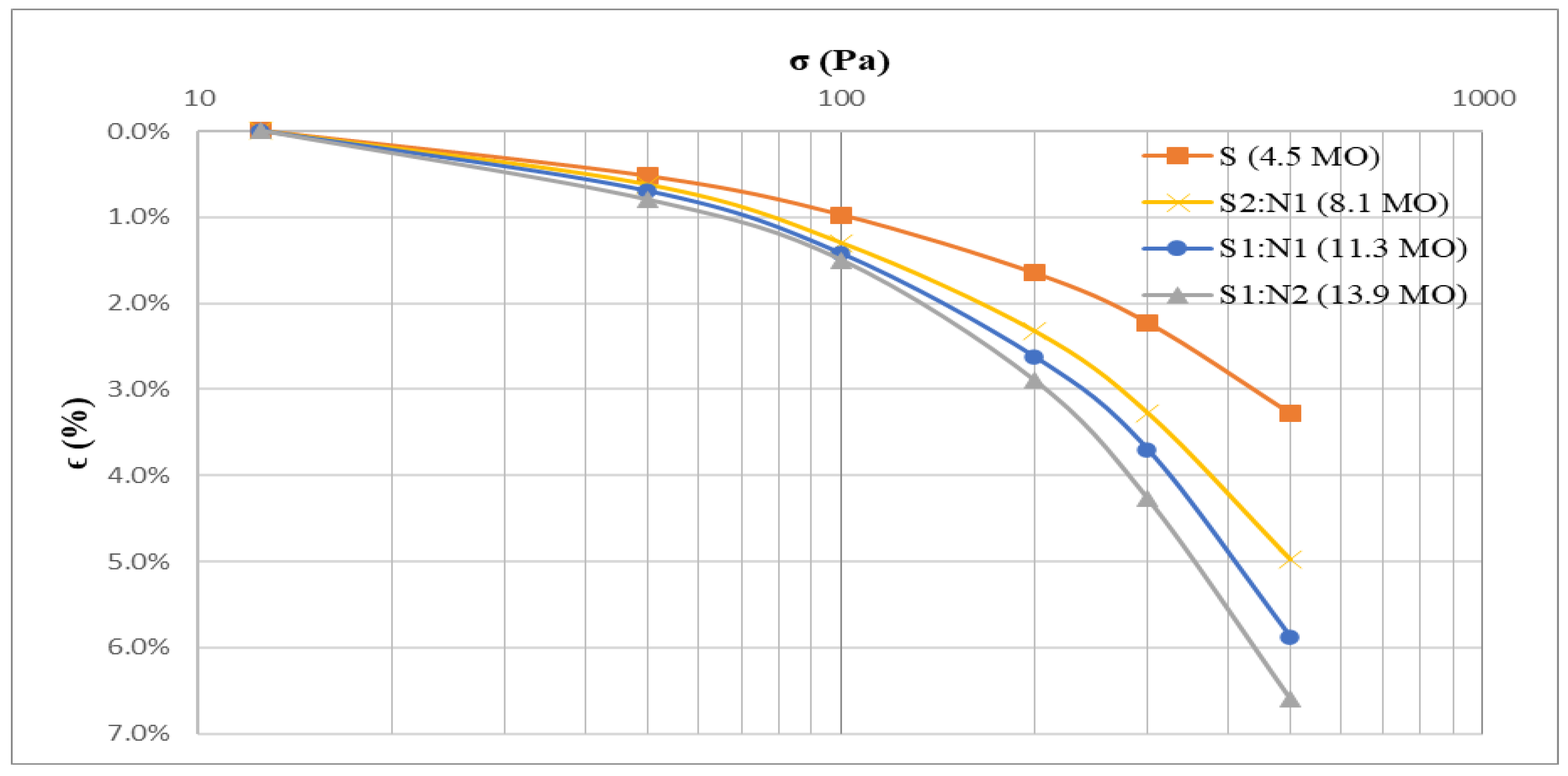

Analysis of compressibility curves (

Figure 8,

Table 5) also demonstrated a clear relationship between density, oedometric modulus values, and organic matter content. The increased organic matter resulted in decreased density and correspondingly lower oedometric modulus values. Consequently, the material transitioned from medium compressibility (E

oed = 10,000–20,000 kPa) to high compressibility (E

oed = 5,000–10,000 kPa) as defined by international standards (ISO 17892 -5:2017). Previous studies have shown that soil organic matter significantly influences the physical and mechanical properties of clay (Gui et al., 2021). At the end of the experiment, the organic matter content in the soil treated with sludge was evaluated. The findings revealed that higher sludge proportions in the mixtures corresponded to higher organic matter contents: S (4.5%), S2:N1 (8.1%), S1:N1 (11.3%), and S1:N2 (13.9%). Although the initial organic matter content in the contaminated soil was 5.2%, its final value was lower after the bioremediation process (4,5%). A similar reduction in organic matter may have occurred in the mixtures, though the final values, which influence their suitability for excavation backfill, were the focus of this assessment. For the evaluated moisture content of 305%, with an organic matter contribution of 39% from the sludge and 5% from the contaminated soil, the observed organic matter percentages in the mixtures closely aligned with theoretical predictions. This consistency supports the feasibility of utilizing these treated materials for geotechnical applications in excavation backfill.

4. CONCLUSIONS

This comprehensive analysis underscores the physicochemical and biological conditions that influence the bioremediation process, highlighting the interplay of soil and sewage sludge properties in petroleum hydrocarbon degradation. Our obtained results highlight also the effectiveness of bioremediation in reducing petroleum hydrocarbon concentrations and demonstrate the stability of heavy metal concentrations throughout the treatment process. Bacteria, such as hydrocarbon-tolerant, hydrocarbon-degrading, and enterobacteria are found in a wide range of natural environments, including in petroleum hydrocarbon-contaminated soils and dehydrated sewage sludges. During the three months of the bioremediation experiment, the number of hydrocarbon-tolerant bacteria, hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria, and enterobacteria varied from one sample to another. In the samples taken at the beginning and at the end of the experiment, the number of hydrocarbon-tolerant bacteria was higher compared to the number of hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria. Although enterobacteria were presented in the samples at the initiation of the experiment, they were not detected in soil samples treated for two and three months with sludges. The obtained results could be explained by the fact that not all the bacteria existing in the soil samples contaminated with petroleum products treated with sewage sludge can tolerate and/or degrade the toxic hydrocarbons that exist in the composition of petroleum products like diesel. Incorporating sewage sludge into petroleum-contaminated sites as a soil amendment not only helps restore soil health but also contributes to bioremediation by stimulating the degradation of hydrocarbons through enhanced indigenous microbial activity.

The use of treated soil as filling material for excavated pits is extremely important because it eliminates the use of natural resources (input of clean soil) and does not produce natural imbalances.

The paper provides a detailed discussion of the results of each test, aiming for a deep understanding of their impact on the advanced bioremediation solution. It was found that the best ratio contaminated soil/sludge=1, in volume, for the cases studied.

To our current knowledge, the topic of the paper is a novelty in the field of decontamination of oil-contaminated soils. In addition, this work advanced a dual recovery process, namely soil recovery, sewage sludge recovery. Also, the process we propose belongs to the zero-waste technology class, as it did not leave behind any volume of waste.

Further research is expected to improve the effectiveness of biological degradation of hydrocarbons and to decrease the content of heavy metals in bioremedied soil.

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by project no. 197/2023 from the “Dunărea de Jos” University of Galați and project no. RO1567-IBB05/2023 from the Institute of Biology Bucharest of Romanian Academy.

References

- Abena M. T. B, Tongtong L., Shah M. N., Zong W., 2019, Biodegradation of total petroleum hydrocarbons (TPH) in highly contaminated soils by natural attenuation and bioaugmentation, Chemosphere, 234, 864-874. [CrossRef]

- Abena M. T. B., Chen G., Chen Z., Zheng X., Li S., Li T., Zhong W., 2020, Microbial diversity changes and enrichment of potential petroleum hydrocarbon degraders in crude oil-, diesel-, and gasoline-contaminated soil. 3 Biotech., 10: 42. [CrossRef]

- Al-Hawash A. B., Dragh M. A., Li S., Alhujaily A., Abbood H. A., Zhang X., Ma F., 2018, Principles of microbial degradation of petroleum hydrocarbons in the environment. The Egyptian Journal of Aquatic Research, 44(2): 71-76.

- Bot A., Benites J., 2005, The importance of soil organic matter. Key to drought-resistant soil and sustained food production, ISBN 92-5-105366-9, ISSN 0253-2050.

- Briffa J., Sinagra E., Blundell R., 2020, Heavy metal pollution in the environment and their toxicological effects on humans, Heliyon 6, e04691. [CrossRef]

- Castro G. A. S., Calvo A. R., Laguna J., Lopez J. G., 2016, Autochtonus microbial responses and hydrocarbons degradation in polluted soil during biostimulating treataments under different soil moisture. Assay in pilot plant, International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation, 108, 91-98. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ibiod.2015.12.009.

- Chibuike G. U., Obiora S.C., 2014, Heavy Metal Polluted Soils: Effect on Plants and Bioremediation Methods, 2014, 752708, http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/752708.

- Chicca I., Becarell, S., Di Gregorio S., 2022, Microbial involvement in the bioremediation of total petroleum hydrocarbon polluted soils: Challenges and perspectives. Environments, 9: 52. [CrossRef]

- Das N., Chandran P., 2011, Microbial Degradation of Petroleum Hydrocarbon Contaminants: An Overview, Hindawi Access to Research Biotechnology Research International, 2011, 941810, doi:10.4061/2011/941810.

- Devatha C. P. A., Vishnu V. A. V., Rao J. P. Ch., 2019, Investigation of physical and chemical characteristics on soil due to crude oil contamination and its remediation, Applied Water Science, 9:89. [CrossRef]

- Gielnik A., Pechaud Y., Huguenot D., Cebron A., Esposito G., van Hullebusch E. D., 2021, Functional potential of sewage sludge digestate microbes to degrade aliphatic hydrocarbons during bioremediation of a petroleum hydrocarbons contaminated soil. Journal of Environmental Management, 280: 111648. [CrossRef]

- Gui Y., Zhang Q., Qin X., Wang J., 2021, Influence of Organic Matter Content on Engineering Properties of Clays, Hindawi Advances in Civil Engineering, 2021, 6654121. [CrossRef]

- Jia W., Cheng L., Tan Q., Liu Y., Dou J., Yang K., Yang Q., Wang S., Li J., Niu G., Zheng L., Ding A., 2023, Response of the soil microbial community to petroleum hydrocarbon stress shows a threshold effect: research on aged realistic contaminated fields. Frontiers in Microbiology, 14: 1188229. [CrossRef]

- Kicińska A., Kosa-Burda B., Kozub P., 2018, Utilization of a sewage sludge for rehabilitating the soils degraded by the metallurgical industry and a possible environmental risk involved. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment, 24: 1990-2010. [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen B. A., Aragaw T. A., Genet M. B., 2024, Bioremediation of petroleum hydrocarbon contaminated soil: a review on principles, degradation mechanisms, and advancements, Frontiers in Environmental Science, 12:1354422, doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2024.1354422.

- Mustafa A. D., Juahir H., Yunus K., Amran M. A., Hasnam C. N. C., Azaman, F., Abidin I. Z., Azmee S. H., Sulaiman N. H., 2015, Oil spill related heavy metal: a review, Malaysian Journal of Analytical Sciences, 19 (6): 1348 – 1360.

- Okparanma. R. N., Mouazen A. M., 2013, Determination of Total Petroleum Hydrocarbon (TPH) and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon (PAH) in soils: A Review of Spectroscopic and non-spectroscopic techniques, 48(6):458-486. [CrossRef]

- Onojake M. C., Omokheyeke O., Osakwe, J. O., 2014. Hydrocarbon contamination to environment, Bulletin of Earth Sciences of Thailand 6, (1), 67-79.

- Ossai I. Ch., Ahmed A., Hassan A., Hamid F. Sh., 2020, Remediation of soil and water contaminated with petroleum hydrocarbon: A review, Environmental Technology & Innovation 17: 100526. [CrossRef]

- Patowary K., Patowary R., Kalita M. C., Deka S., 2016, Development of an efficient bacterial consortium for the potential remediation of hydrocarbons from contaminated sites. Frontiers in Microbiology, 7: 1-14.

- Polyak Y. M., Bakina L. G., Chugunova M. V., Mayachkina N. V., Gerasimov A. O., Bure V. M., 2018, Effect of remediation strategies on biological activity of oil-contaminated soil–A field study, International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation, 126: 57-68. [CrossRef]

- Ravi A., Ravur, M., Krishnan R., Narenkumar J., Anu K., Alsalhi M. S., Devanesan S., Kamala-Kannan S., Rajasekar A., 2022, Characterization of petroleum degrading bacteria and its optimization conditions on effective utilization of petroleum hydrocarbons. Microbiological Research, 265: 127184.

- Rorat A., Courtois P., Vandenbulcke F., Lemiere S., 2019, Sanitary and environmental aspects of sewage sludge management. Industrial and Municipal Sludge, 2019: 155-180. [CrossRef]

- Ruehlmann J., 2020, Soil particle density as affected by soil texture and soil organic matter: 1. Partitioning of SOM in conceptional fractions and derivation of a variable SOC to SOM conversion factor, Geoderma 375, 114542. [CrossRef]

- Ruehlmann J., Körschensb M., 2020, Soil particle density as affected by soil texture and soil organic matter: 2. Predicting the effect of the mineral composition of particle-size fractions, Geoderma 375, 114543. [CrossRef]

- Sambrook J., Russel D., 2001. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 3rd edition. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, New York.

- Satoh Y., Ishizuka Sh., Hiradate S., Nagano M. A. A. H., Koarashi J., 2023, Sequential loss-on-ignition as a simple method for evaluating the stability of soil organic matter under actual environmental conditions, 239, 117224. [CrossRef]

- Simionov I. A., Călmuc M., Iticescu C., Călmuc V., Georgescu P. L., Faggio C., Petrea Ş. M., 2023, Human health risk assessment of potentially toxic elements and microplastics accumulation in products from the Danube River Basin fish market, Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology, 104, 104307.

- Stancu M. M., 2020, Kerosene tolerance in Achromobacter and Pseudomonas species. Annals of Microbiology, 70(8). [CrossRef]

- Stancu M. M., 2023, Characterization of new diesel-degrading bacteria isolated from freshwater sediments. International Microbiology, 26: 109-122.

- Stancu M. M., 2024, Characterization of a new Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain isolated from petroleum-polluted soil. Waste and Biomass Valorization, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Stancu M. M., Grifoll M., 2011, Multidrug resistance in hydrocarbon-tolerant Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. The Journal of General and Applied Microbiology, 57: 1-18.

- Swain Ch. K., 2024, Environmental pollution indices: a review on concentration of heavy metals in air, water, and soil near industrialization and urbanization, Discover Environment, 2: 5. [CrossRef]

- Xu X., Liu W., Tian S., Wang W., Qi Q., Jiang P., Jiang P., Gao X., Li F., Li H., Yu, H., 2018, Petroleum hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria for the remediation of oil pollution under aerobic conditions: A perspective analysis. Frontiers in Microbiology, 9: 2885. [CrossRef]

- EN ISO 14688-1, 2018, Geotechnical research and testing - soil identification and classification Part 1: identification and description.

- EN ISO 17892 -5:2017 - Geotechnical investigation and testing - Laboratory testing of soil - Part 5: Incremental loading oedometer test.

- ASTM D698-12, 2021, - Standard test method for laboratory Compaction of soil using standard effort (12 400 ft-lb/ft3 (600kN-m/m3))1, https://www.studocu.com/bo/document/escuela-militar-de-ingenieria/mecanica-de-suelos-1/astm-d698-12-compactacion-estandar-compress/33534831.

- ASTM International D2974-20 Standard test methods for moisture, ash, and organic matter of peat and other organic soils.

Figure 1.

Bioremediation experiment of petroleum-contaminated soil treated with sludge Biopile (BP); soil aeration (SA); soil sampling (SS).

Figure 1.

Bioremediation experiment of petroleum-contaminated soil treated with sludge Biopile (BP); soil aeration (SA); soil sampling (SS).

Figure 2.

Granulometric distribution of the petroleum-contaminate soil and sludge.

Figure 2.

Granulometric distribution of the petroleum-contaminate soil and sludge.

Figure 3.

Ternary diagram for the soil and sludge classification.

Figure 3.

Ternary diagram for the soil and sludge classification.

Figure 4.

Microbiological analysis of petroleum-contaminated soil treated with sludge Initial samples (PI), after two (PII) and three (PIII) months of treatment; sample suspensions (PIs, PIIs, PIIIs); microbiological analysis (MA) of the samples, most probable number (MPN) method, plate count agar (PCA) method.

Figure 4.

Microbiological analysis of petroleum-contaminated soil treated with sludge Initial samples (PI), after two (PII) and three (PIII) months of treatment; sample suspensions (PIs, PIIs, PIIIs); microbiological analysis (MA) of the samples, most probable number (MPN) method, plate count agar (PCA) method.

Figure 5.

Isolation of hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria from petroleum-contaminated soil treated with sludge Enrichment cultures (EC) on minimal medium with diesel; growth of isolated bacteria on agar media (LB, EMB), bacteria isolated from initial samples (CI), after two (CII) and three (CIII) months of treatment.

Figure 5.

Isolation of hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria from petroleum-contaminated soil treated with sludge Enrichment cultures (EC) on minimal medium with diesel; growth of isolated bacteria on agar media (LB, EMB), bacteria isolated from initial samples (CI), after two (CII) and three (CIII) months of treatment.

Figure 6.

Bioremediation of the petroleum-contaminated soil treated with sludge.

Figure 6.

Bioremediation of the petroleum-contaminated soil treated with sludge.

Figure 7.

Compaction tests for the petroleum-contaminated soil treated with sludge.

Figure 7.

Compaction tests for the petroleum-contaminated soil treated with sludge.

Figure 8.

Compressibility tests for petroleum-contaminated soil treated with sludge.

Figure 8.

Compressibility tests for petroleum-contaminated soil treated with sludge.

Table 1.

Physico-chemical characterization of petroleum-contaminated soil and sludge.

Table 1.

Physico-chemical characterization of petroleum-contaminated soil and sludge.

| Parameters |

Samples |

| Soil |

Sludge |

| pH |

7.3 |

6.8 |

| Moisture (W, %) |

19.06 |

305 |

| Density of the mineral skeleton (ρsmediu , g cm-3) |

2.662 |

2.674 |

| Organic matter (%) |

Loss-on-ignition |

5.2 |

38.2 |

| Oxidation |

5.5 |

39.3 |

| Heavy metals (mg/Kg ds) |

Cadmium |

<0.8 |

<0.8 |

| Cromium |

19.9 |

30,6 |

| Copper |

21.6 |

107.0 |

| Nickel |

26.1 |

28.6 |

| Lead |

12.2 |

27.0 |

| Zinc |

50.0 |

348.0 |

| Petroleum hydrocarbons (mg kg-1 ds) |

4630 |

3810 |

Table 2.

Hydrocarbon-tolerant, hydrocarbon-degrading, and enterobacteria in the petroleum-contaminated soil treated with sludge.

Table 2.

Hydrocarbon-tolerant, hydrocarbon-degrading, and enterobacteria in the petroleum-contaminated soil treated with sludge.

| Number of bacteria |

Samples |

| Soil |

Soi and sludge mixtures (v/v) |

| S1:N1 |

S2:N1 |

S1:N2 |

| Hydrocarbon-tolerant bacteria (cell g-1) |

PI |

2.5×1011

|

2.5×1011

|

2.5×1011

|

2.5×1011

|

| PII |

1.6×1012

|

2.5×1011

|

2.5×1011

|

2.5×1011

|

| PIII |

3.0×1010

|

2.5×1011

|

2.5×1011

|

2.5×1011

|

| Hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria (cell g-1) |

PI |

1.7×1010

|

1.7×109

|

1.7×107

|

9.5×104

|

| PII |

2.0×1011

|

2.5×1011

|

2.5×1011

|

2.5×1011

|

| PIII |

3.0×105

|

8.0×105

|

9.5×105

|

1.7×105

|

| Enterobacteria (cfu g-1) |

PI |

2.0×105

|

3.6×105

|

3.5×104

|

2.5×104

|

| PII |

0, Ff |

0, Ff |

0, Ff |

0, Ff |

| PIII |

0, Ff |

0, Ff |

0, Ff |

0, Ff |

| Initial samples (PI), after two (PII) and three (PIII) months of treatment; filamentous fungi (Ff) on EMB agar. |

Table 3.

Hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria isolated from the petroleum-contaminated soil treated with sludge.

Table 3.

Hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria isolated from the petroleum-contaminated soil treated with sludge.

| Hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria |

CI |

CII |

CIII |

| C1.1 |

C1.3 |

C1.4 |

C1.5 |

C2.1 |

C2.3 |

C2.4 |

C2.5 |

C3.1 |

C3.3 |

C3.4 |

C3.5 |

| Growth on diesel |

Absorbance (OD660 nm) |

0.97 |

0.90 |

0.95 |

0.89 |

0.82 |

0.80 |

0.75 |

0.69 |

0.76 |

0.70 |

0.68 |

0.58 |

| Viability (LB, %) |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

| Viability (LB-diesel, %) |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

| Viability (EMB, %) |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

| Biosurfactants |

Emulsification index (E24, %) |

100 |

50 |

10 |

10 |

50 |

50 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

| Diesel overlay |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| CTAB blue |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

| Diesel biodegradation |

Diesel fragmentation |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| CO2 (mg l-1) |

1848 |

1748 |

1660 |

1630 |

1748 |

1748 |

1560 |

1460 |

1460 |

1460 |

1416 |

1416 |

| Bacteria isolated from initial samples (CI), after two (CII) and three (CIII) months of treatment; consortia (C1.1, 1.3, 1.4, 1.5; C2.1, 2.3, 2.4, 2.5; C3.1, 3.3, 3.4, 3.5); biosurfactants, diesel overlay, CTAB blue method, positive reaction (+), negative reaction (-); diesel fragmentation, positive reaction (+); CO2 production (CO2 mg l-1). |

Table 4.

Physico-chemical characterization of petroleum-contaminated soil treated with sludge.

Table 4.

Physico-chemical characterization of petroleum-contaminated soil treated with sludge.

| Parameters |

Samples |

| Soil |

Soil and sludge mixtures (v/v) |

| S1:N1 |

S2:N1 |

S1:N2 |

| Organic matter (%) |

Combustion |

PI |

5.2 |

ND |

ND |

ND |

| PIII |

4.5 |

11.3 |

8.1 |

13.9 |

| Heavy metals (mg Kg-1 ds) |

Cadmium (Cd) |

PI |

<0.8 |

<0.8 |

<0.8 |

<0.8 |

| PIII |

<0.8 |

<0.8 |

<0.8 |

<0.8 |

| Chromium (Cr) |

PI |

19.9 |

22.6 |

20.5 |

24.0 |

| PIII |

23.5 |

24.3 |

25.6 |

24.2 |

| Copper (Cu) |

PI |

21.6 |

37.9 |

28.5 |

48.1 |

| PIII |

22.7 |

37.8 |

33.8 |

42.4 |

| Nickel (Ni) |

PI |

26.1 |

26.7 |

25.2 |

27.2 |

| PIII |

26.8 |

25.8 |

27.4 |

26.4 |

| Lead (Pb) |

PI |

12.2 |

16.3 |

17.4 |

17.1 |

| PIII |

14.2 |

16.8 |

16.3 |

18.0 |

| Zinc (Zn) |

PI |

50.0 |

110.0 |

74.2 |

141.0 |

| PIII |

54.8 |

110.0 |

91.4 |

121.0 |

| Petroleum hydrocarbons (mg Kg-1 ds) |

PI |

4630 |

6190 |

3200 |

4350 |

| PII |

2500 |

2900 |

2000 |

2380 |

| PIII |

2100 |

2000 |

1710 |

1840 |

| Not determined (ND). |

Table 5.

Compressibility modules for petroleum-contaminated soil treated with sludge.

Table 5.

Compressibility modules for petroleum-contaminated soil treated with sludge.

| Vertical stress1cyyσ (kPa) |

Oedometer modules |

Samples |

| Soil |

Soil and sludge mixtures (v/v) |

| S1:N1 |

S2:N1 |

S1:N2 |

| 100 |

Eoed100-200 |

14815 |

8333 |

9756 |

7143 |

| 200 |

Eoed200-300 |

17391 |

9302 |

10526 |

7273 |

| 300 |

Eoed300-500 |

19048 |

9195 |

11765 |

8602 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).