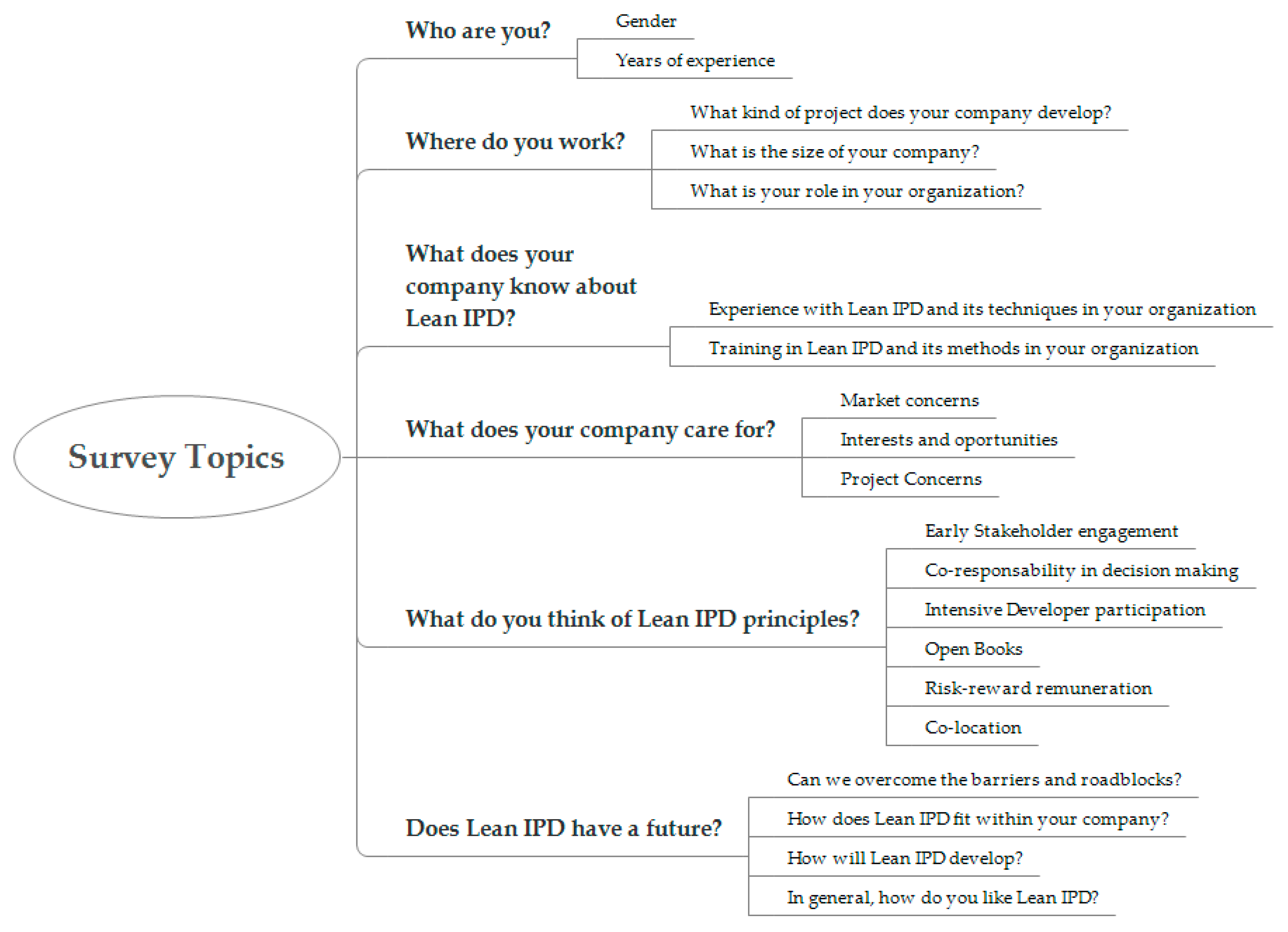

3.3.1. Lean IPD Principles

Lean IPD is based on the simultaneous application of a series of governance mechanisms and the use of a specific operating system [

33] he philosophical foundation of Lean emphasizes values such as long-term thinking, putting people at the center, eliminating waste, and stabilizing workflow, among others [

34]. The application of certain techniques such as the Last Planner System, Target Value Design, Takt-Time, or 5S aims to promote these values and constitutes the operating system of projects.

Among the governance principles of Lean IPD are early stakeholder involvement, shared decision-making responsibility, intensive developer participation, open-book accounting, risk-reward compensation, and co-location [

35]

The involvement of the contractor, the owner, and the architectural firm from the start of the project is one of the foundations of Lean IPD and one of its most distinguishing principles compared to the sequential Design-Bid-Build method. Its purpose is to leverage the expertise of contractors during the design phase to avoid rework in the future. In a broader sense, it can be stated that: “The knowledge about the construction, operation, and use processes is often introduced sequentially, greatly diminishing its impact of making a building high-performing. Integrating process knowledge makes knowledge about all critical life cycle phases available to the IPD team early and comprehensively.” [

27]

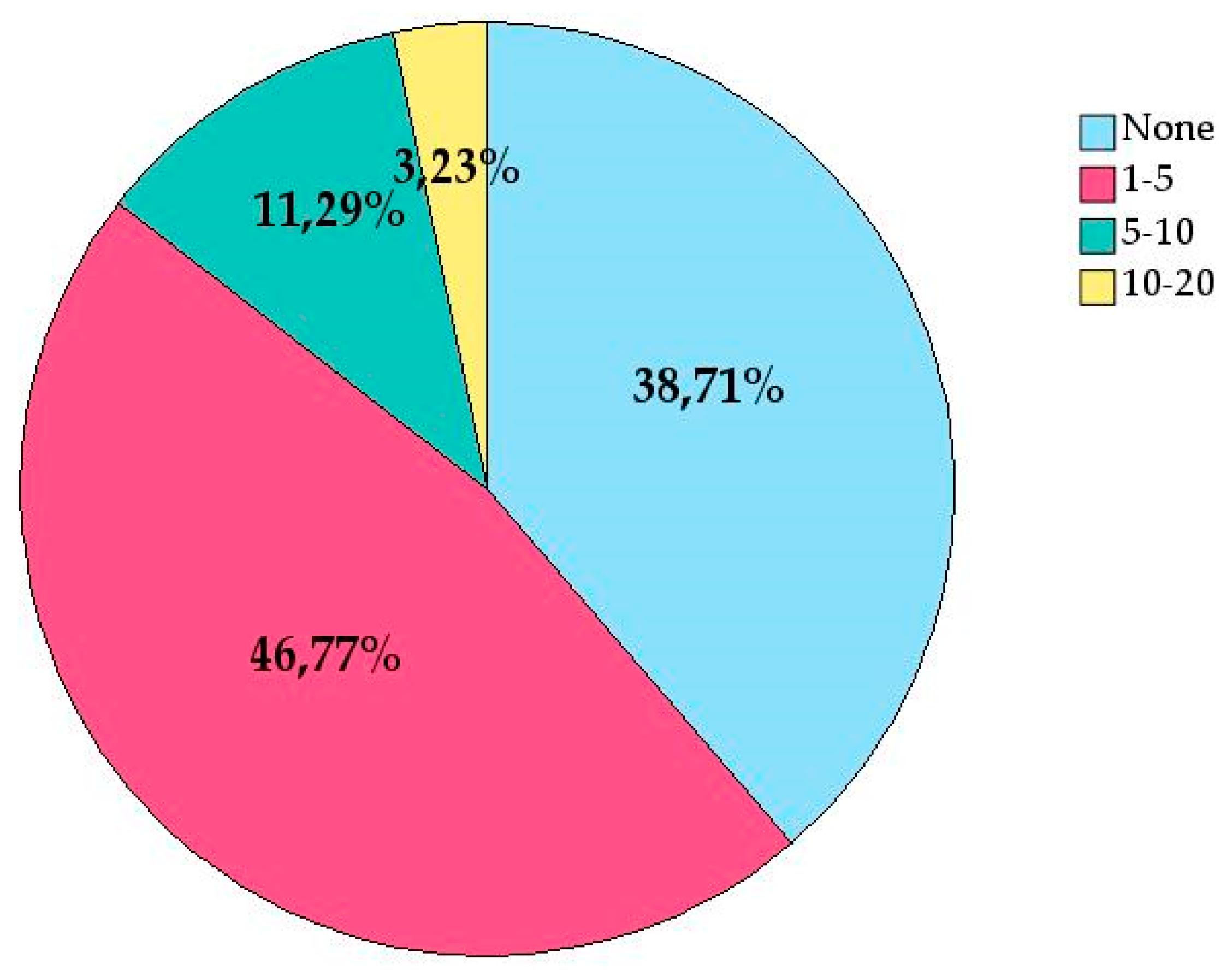

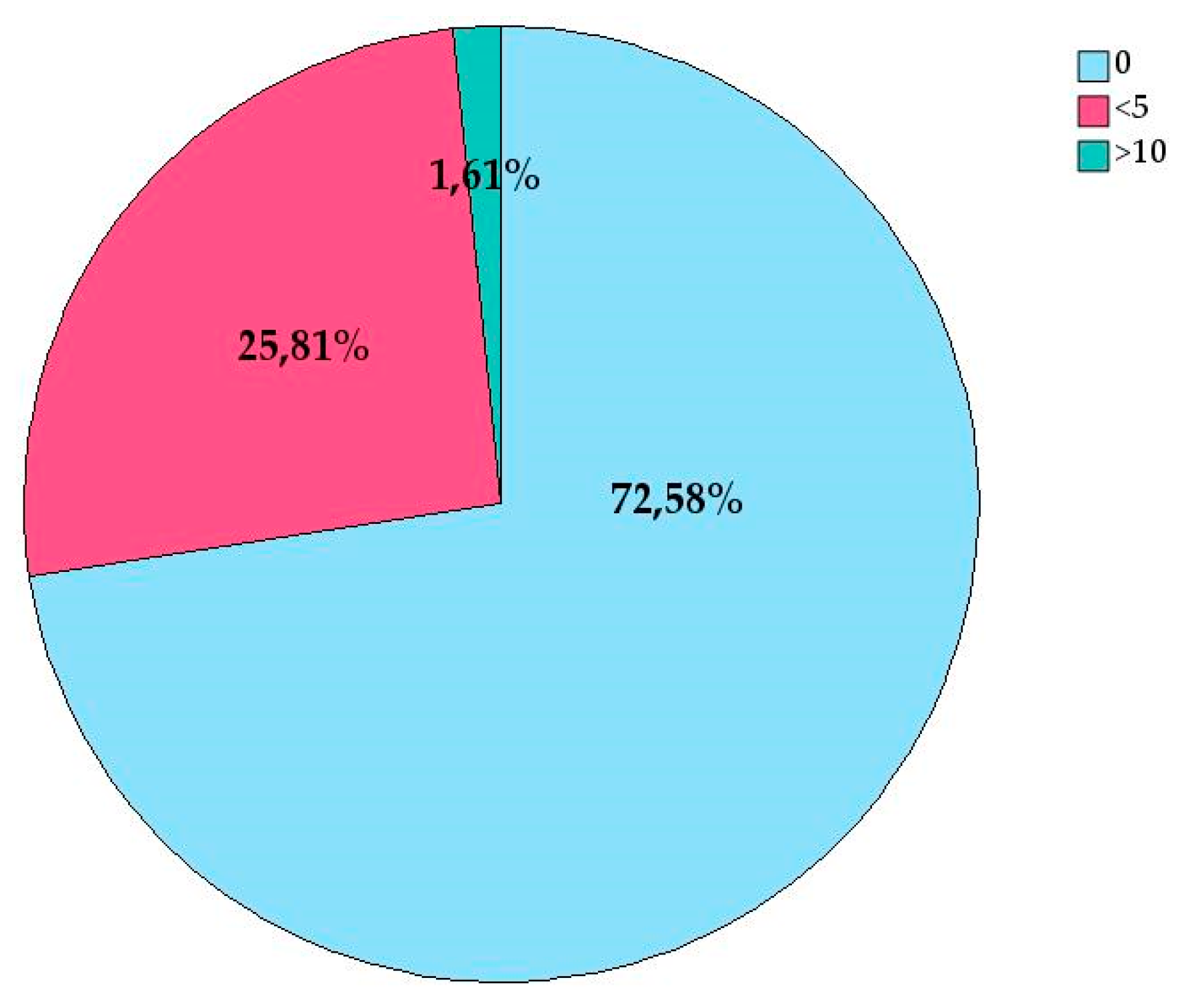

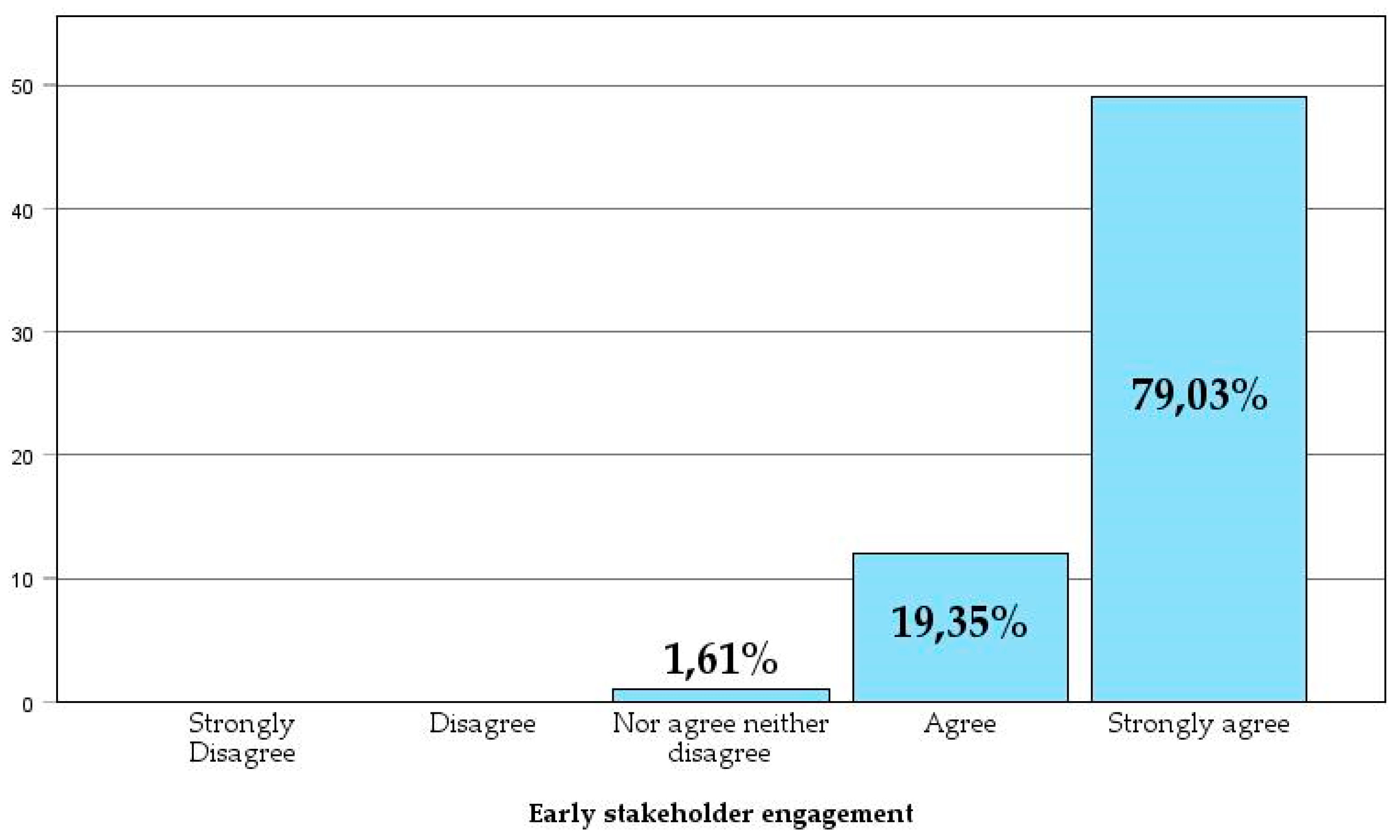

The majority of respondents (79.03%) strongly agreed that the involvement of the contractor, the owner, and the architectural firm from the beginning of the project enhances product definition, the integration of various technical solutions, team training, understanding of project objectives, understanding of costs, and reduces uncertainties and risks. None of the respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed, and only one person was neutral.

The broad consensus on the positive effects of early stakeholder engagement makes it the most celebrated principle of Lean IPD among respondents. This finding opens the door to many reflections: How are teams formed before the design phase? How is the contractor remunerated during this phase? How is the expected construction cost established? Can a different contractor be selected for the construction phase than the one involved in the design?

The decision-making process in Lean IPD differs from the traditional Design-Bid-Build approach, as decisions are made collaboratively by all stakeholders for the benefit of the project. With the involvement of all parties from the outset, the contractor, the architectural firm, and the owner or their representative have a voice and vote in project decisions, contributing their experience and expertise. This does not exclude that “one of the first things the IPD team needs to do is to assign work and decision-making responsibilities that cover the duration of the project. For example, in earlier phases of the project, the designer will often take the lead, whereas when it transitions to construction, the general contractor or a trade contractor may lead the effort. Documentation of these responsibilities is sometimes called a task or responsibility matrix"[

28]

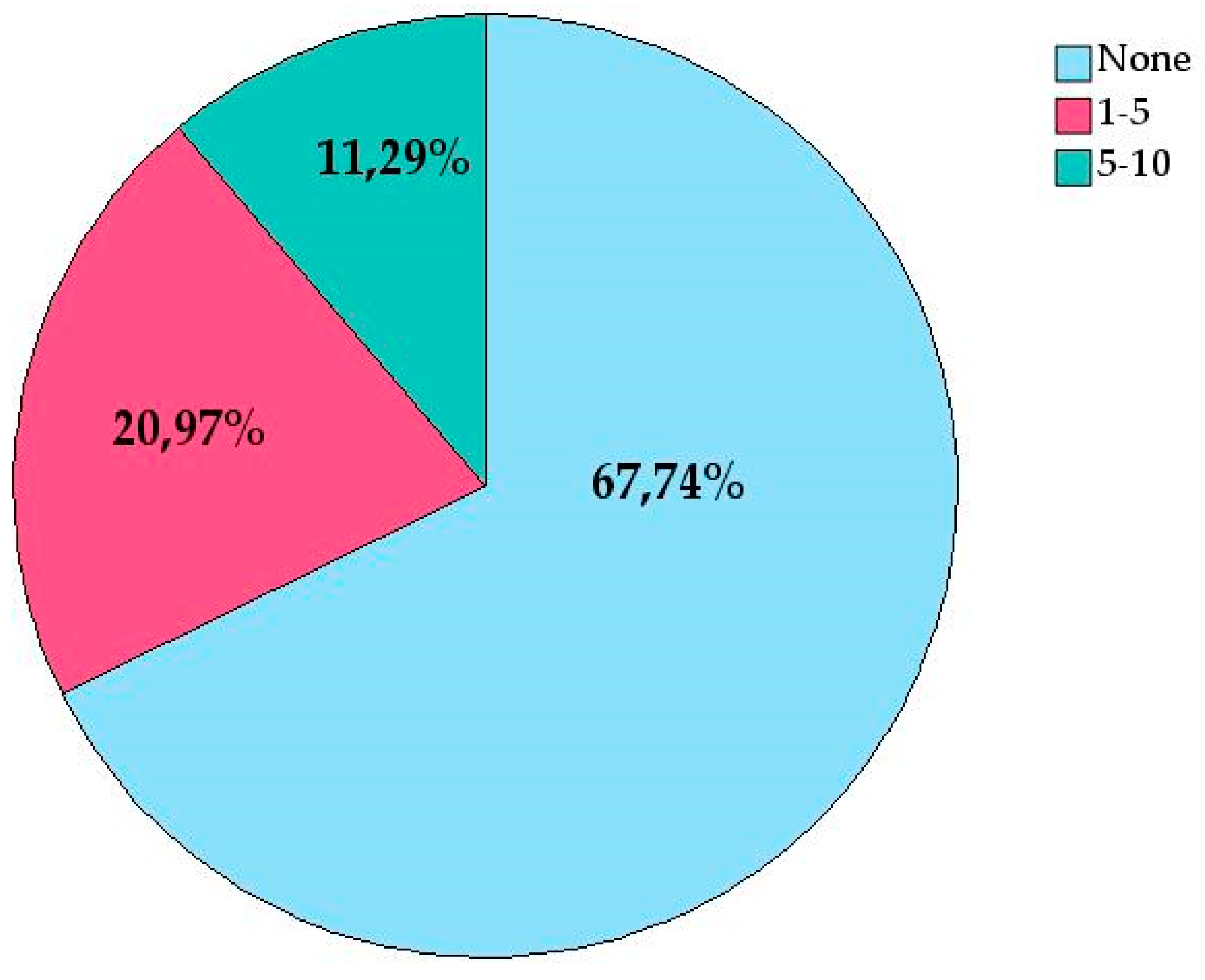

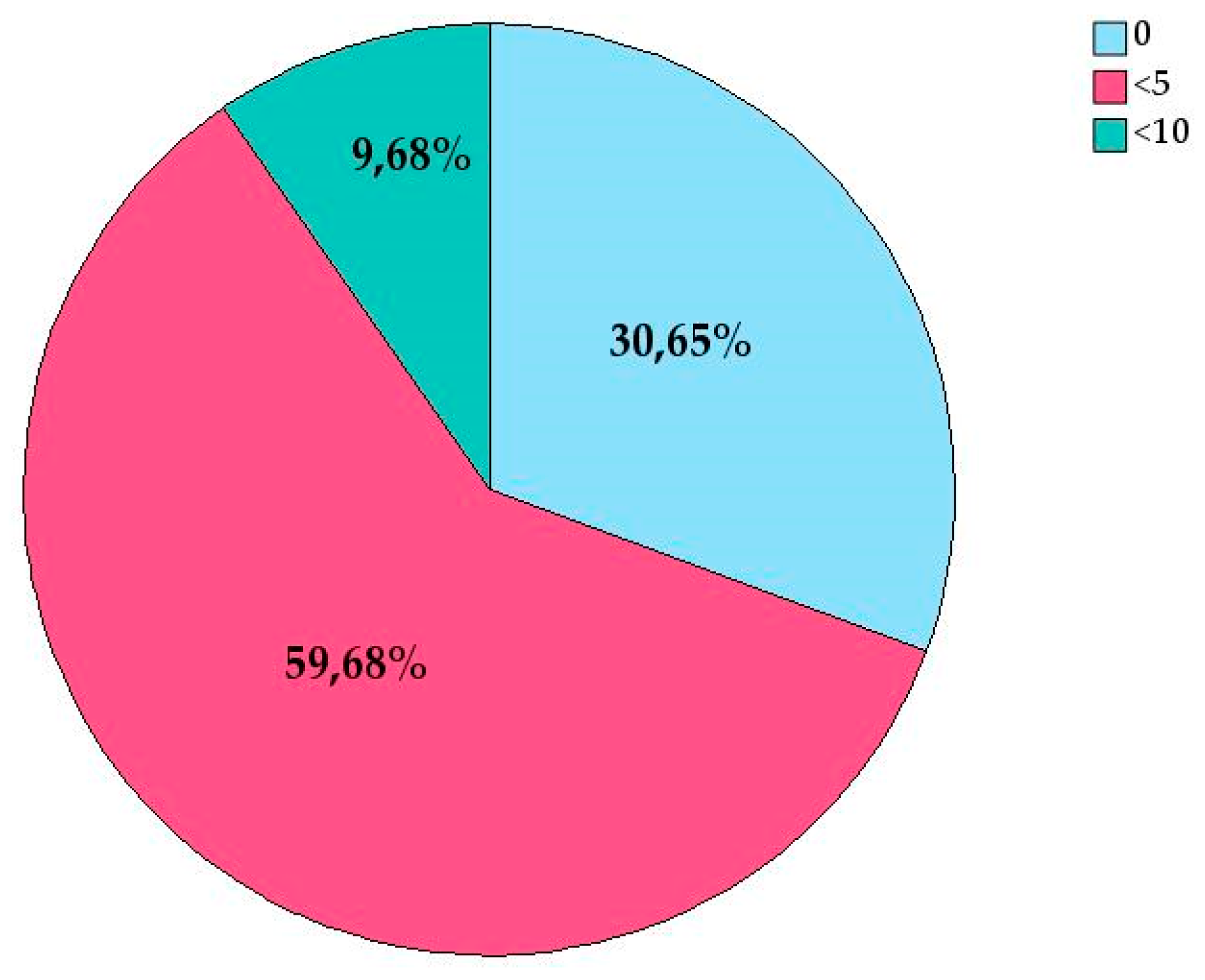

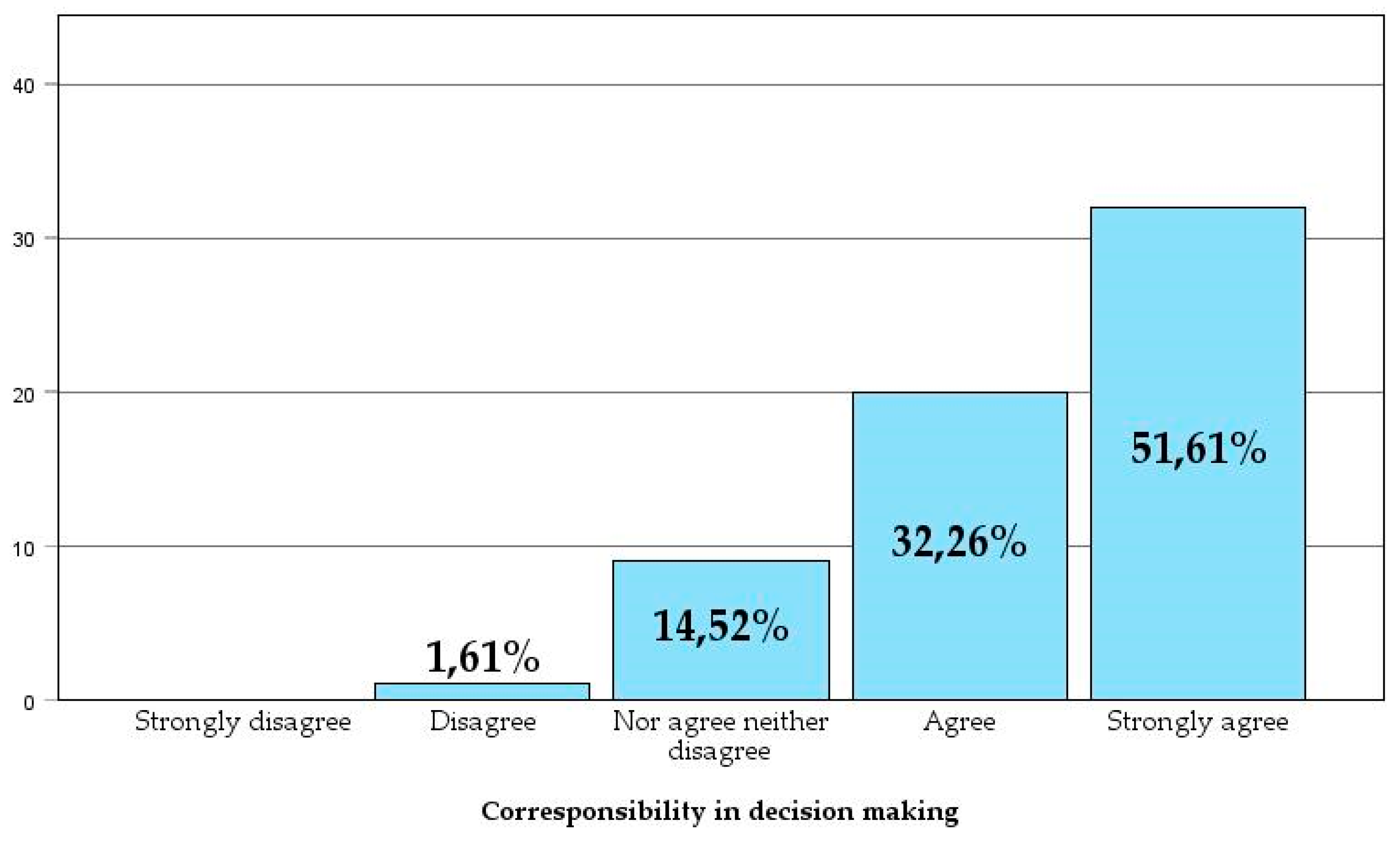

The vast majority of respondents (83.87%) agreed or strongly agreed that co-responsibility in decision-making ensures that the work executed must be consensus-based. This approach improves the quality of decisions, reduces blame attribution, and prioritizes the project’s interests over those of individual parties. Only one respondent disagreed, and none strongly disagreed with this statement.

Lean IPD promotes a shift in the role of the owner, who must transition from the role of a client to that of an active member of the development and construction team. To achieve this, the owner must have professionals with real estate market knowledge, as well as technical profiles capable of dedicating sufficient time to actively fulfill this new role in projects. Intensive Owner Participacion "… requires effort, but it is also an opportunity because it allows the owner to directly influence the project's outcome. Moreover, by being directly engaged, the owner eliminates the propose/review/approve cycles that can result in delay and rework."[

28] Besides, "this leadership role should not be delegated to outside consultants, because they rarely are empowered to make owner-level decisions". [

36]

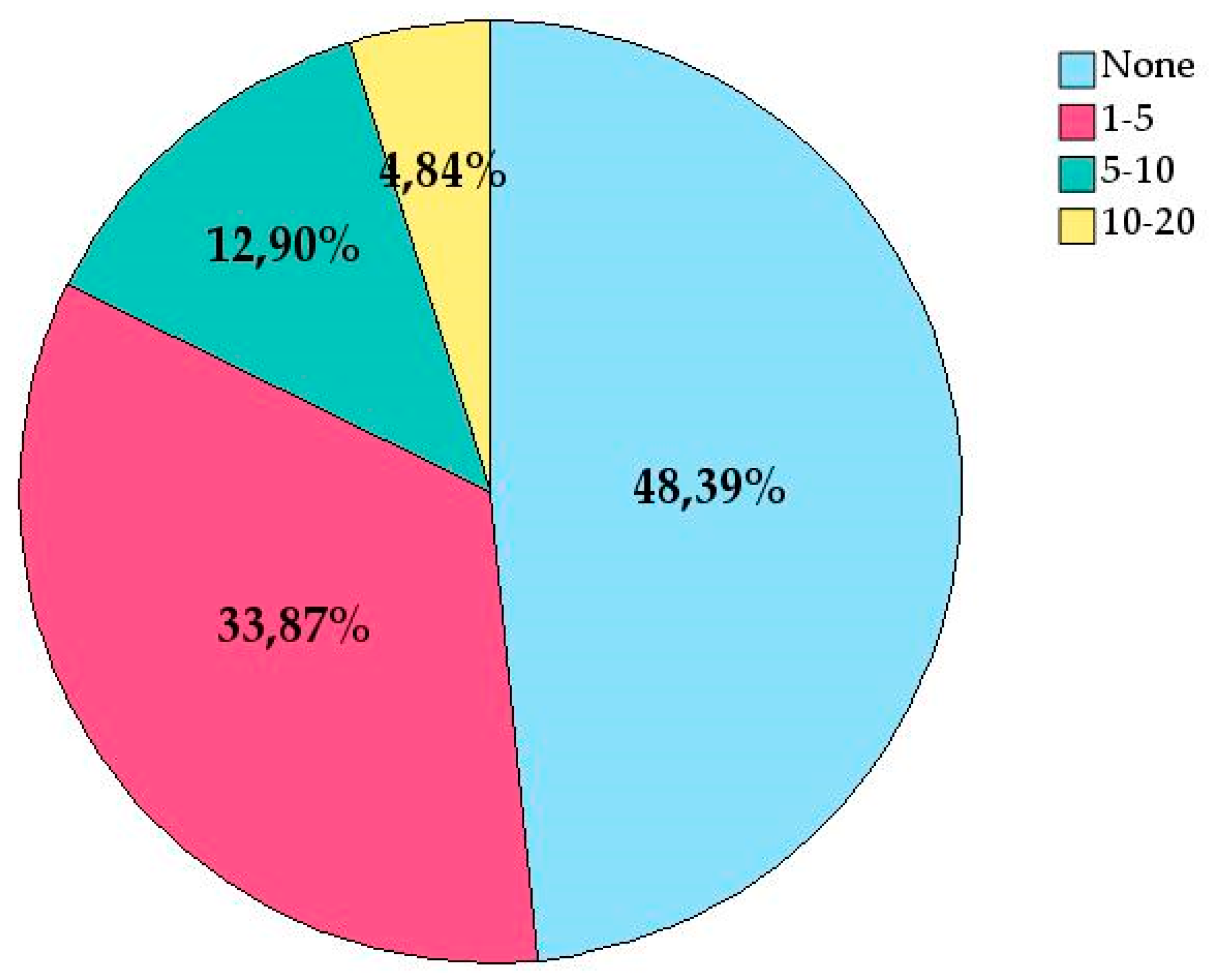

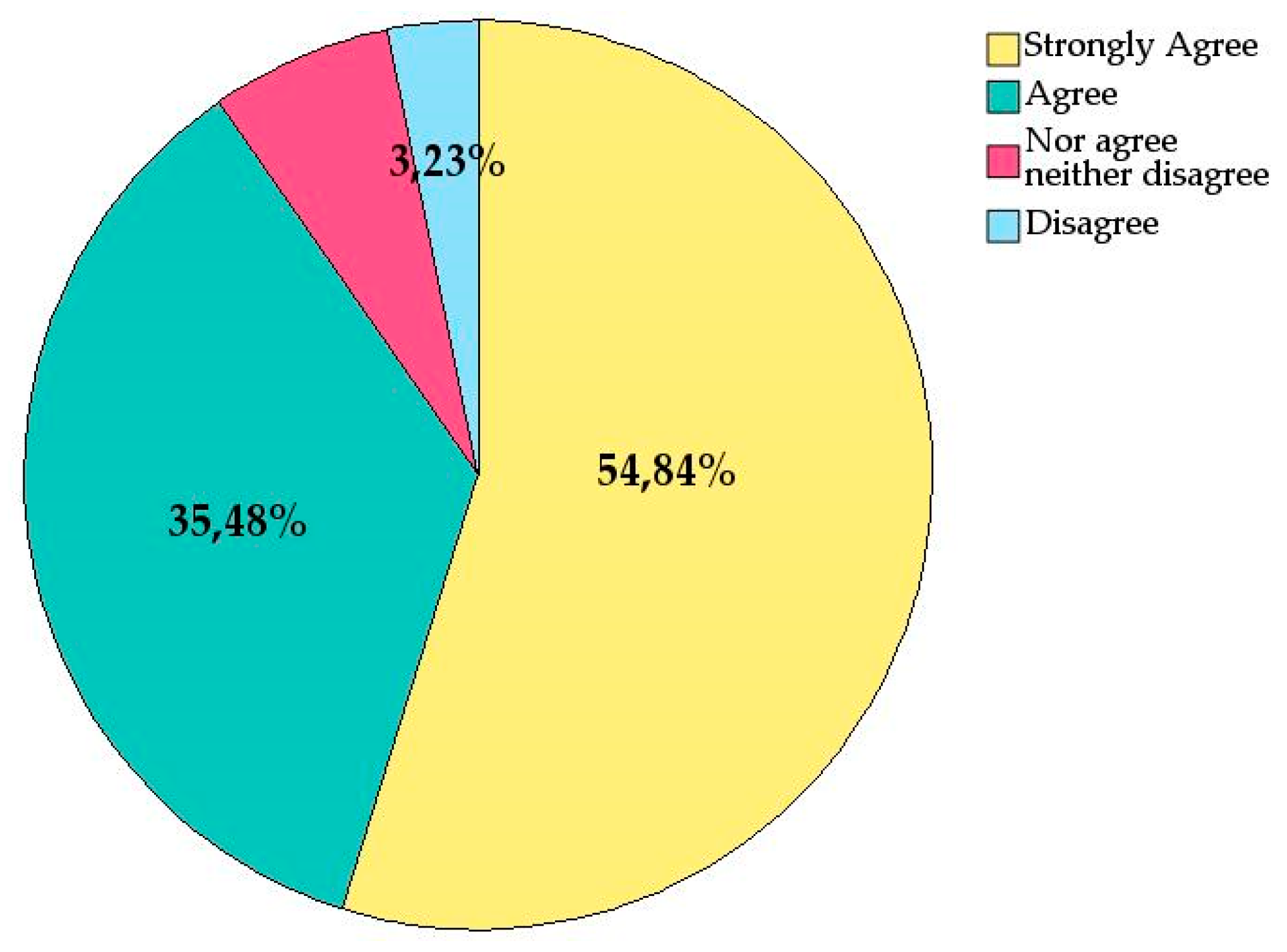

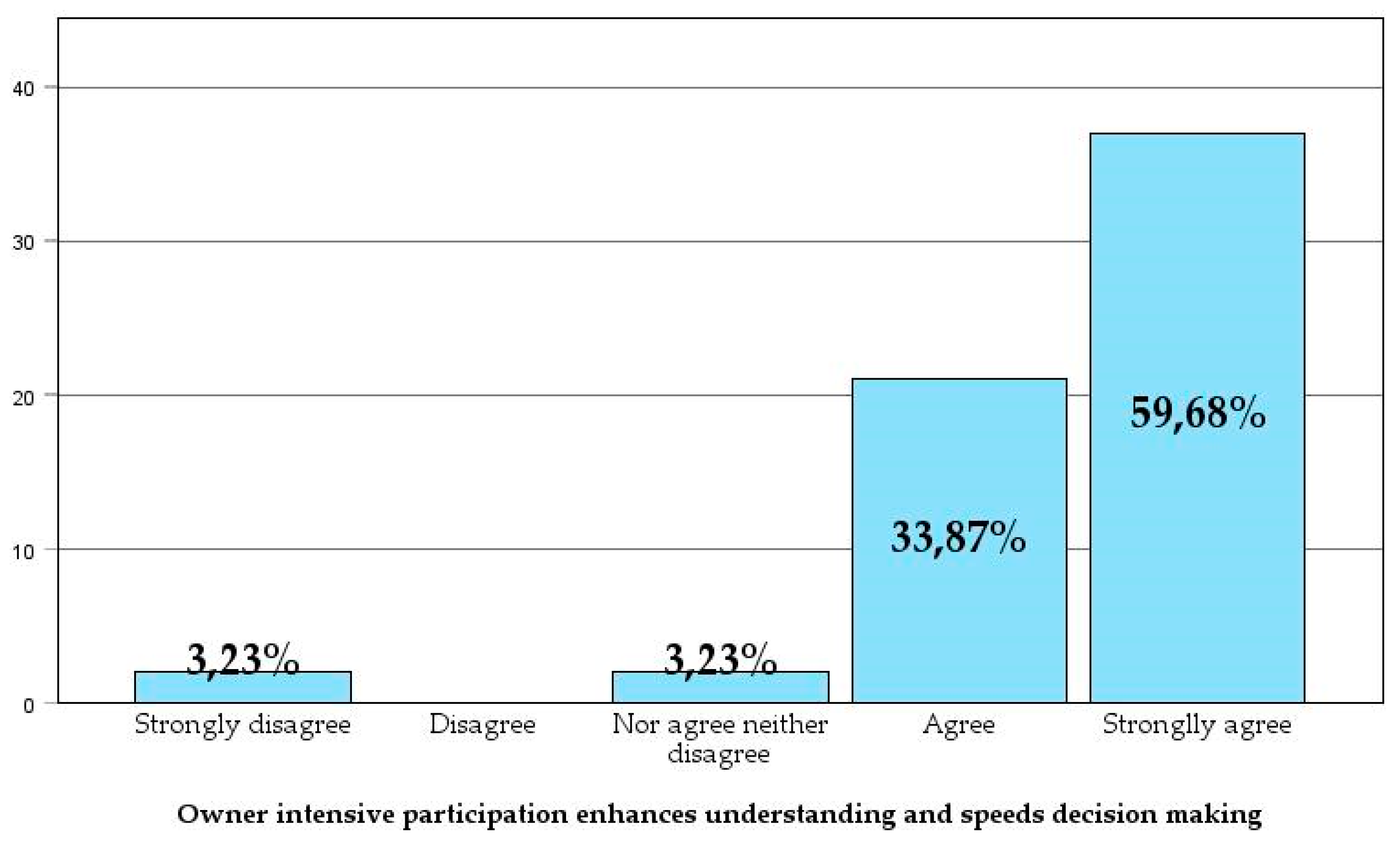

The vast majority of respondents (93.55%) agree or strongly agree that intensive owner participation improves their understanding of the project and accelerates decision-making. Additionally, 82.26% of respondents agree or strongly agree that the owner should attend integrated project team meetings as an equal member, valuing intensive participation over occasional involvement during key moments.

To achieve this level of dedication in projects, it is essential for real estate development companies to have sufficient technical staff prepared to participate intensively in projects. A significant majority of respondents (79.03%) stated that their organizations place great importance on technical profiles and that they are ready to engage intensively in projects.

Although there is no consistent definition of Open-Book Accounting (OBA), most authors “emphasize two important characteristics of OBA practices: the regular disclosure of private information beyond corporate borders and the sharing of financial data”[

37].

In practical terms, sharing financial records provides opportunities to optimize costs across the entire value chain while promoting trust and a culture of accountability. The appeal of implementing open-book accounting (OBA) depends not only on the specific nature of the sector in which it is introduced but also on exogenous environmental factors, such as the degree of market competition or the prevailing economic growth trend at the time of consideration. Endogenous variables also come into play, such as company size, the ability to manage accounting systems, competitive policies, and a long-term commitment vision.[

38]

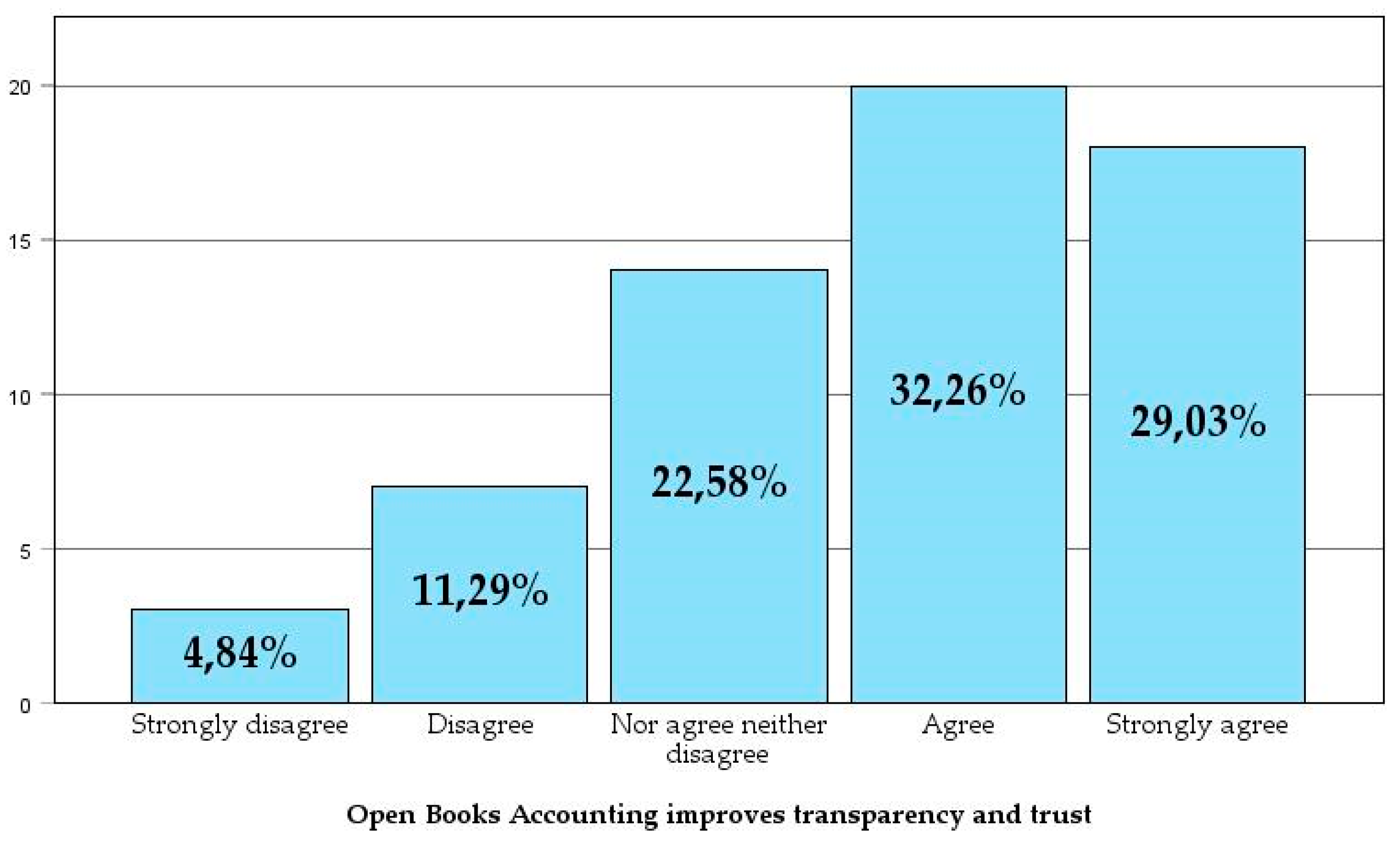

Most respondents (61.33%) agree or strongly agree that open-book accounting improves transparency and trust among stakeholders during the design and construction process. They also believe that by eliminating economic tension, the likelihood of one party attempting to profit at the expense of others is reduced. However, despite generally agreeing that open-book accounting is beneficial for projects, there is greater variability in responses when asked if their organization would be willing to embrace the level of transparency and cost uncertainty it entails. While 50% are willing to take on the challenges of open-book accounting, 30.64% of the sample expressed disagreement or strong disagreement. Additionally, the percentage of respondents who were neutral (neither agree nor disagree) increased to 19.35%.

These results, although positive, highlight a potential misalignment between industry culture and the principles of Lean IPD, which will be explored further below. According to Bhonde, “there is resistance throughout the construction industry to provide financial transparency and ‘open book’ project management, believing that such transparency could make an organization more vulnerable."[

14]

One of the most effective tools for aligning the interests of all parties is to compensate stakeholders based on the risk they assume in the project and the success they achieve in meeting shared objectives. These objectives, set by the owner and agreed upon by the rest of the IPD team, are not exclusively economic; they may also relate to factors such as schedule, sustainability, or compliance with other conditions of satisfaction.

According to Rodrigues et al. (2021), "the greatest benefit of sharing risk and reward reported in the Tønsberg project is the parties realizing they need to work toward the common goal, prioritizing the whole instead of individual performance."[

39]

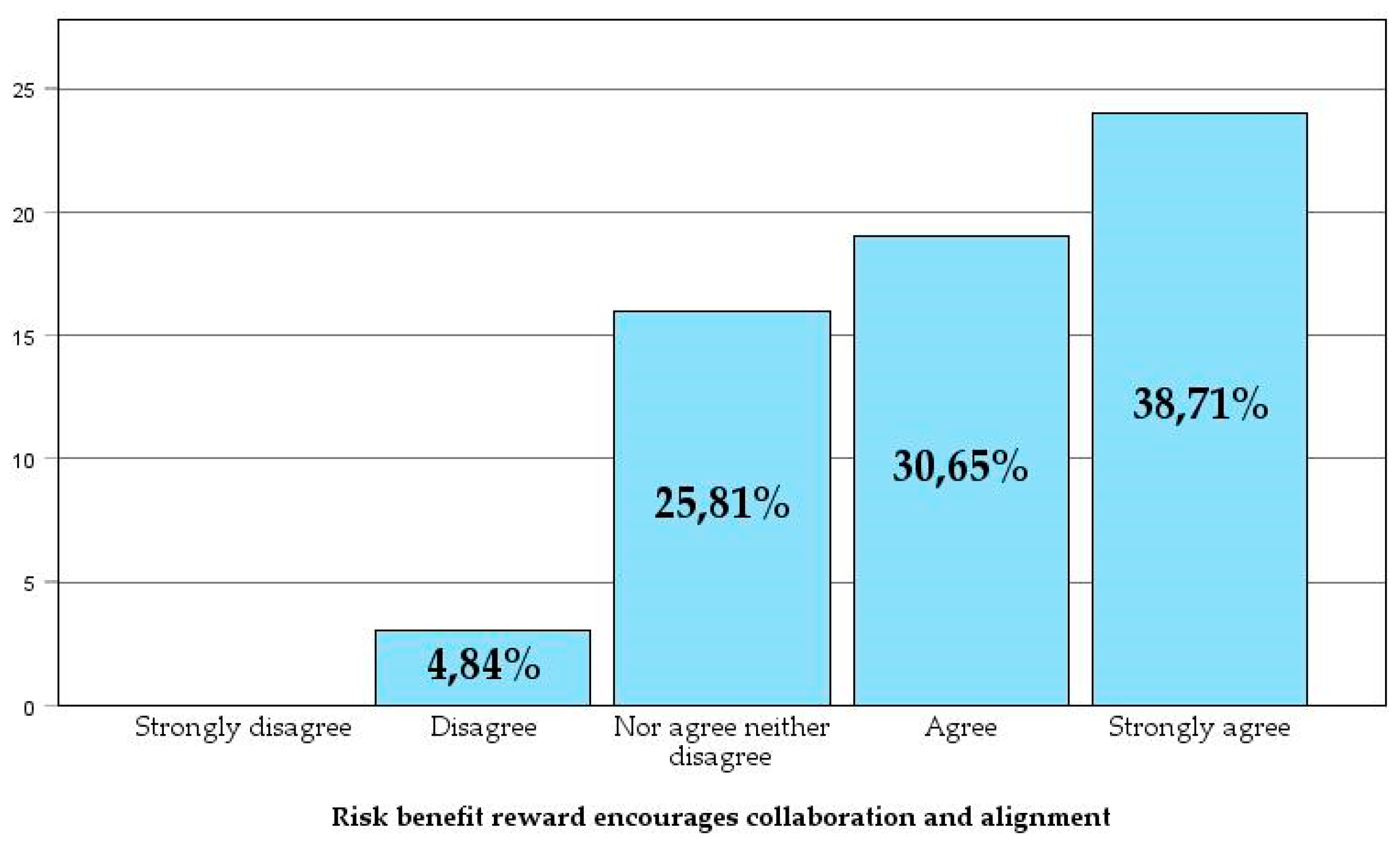

Most respondents (69.36%) agree or strongly agree that risk-reward compensation encourages collaboration and a sense of teamwork, placing the project at the center rather than the individual interests of the stakeholders. A quarter of the sample neither agree nor disagree, and only 4.84% disagree with this statement.

However, the level of agreement drops to 50% when respondents are asked if linking stakeholders’ profits to the project’s success could be unfair, given the multitude of factors beyond their control, such as labor shortages or economic conditions. Additionally, 22.6% disagree or strongly disagree with this statement, indicating that many consider this approach to be unfair.

Co-location involves members of the integrated project team working in the same physical space during the development and construction phases. This location should be a neutral space that fosters a sense of belonging to the project for all team members, regardless of their employer. There is broad consensus regarding the benefits of co-location: “co-location can build relationships and ensure those right experts are available in a timely manner." [

10] and although research “tends to acknowledge this as a highly recommendable solution” [

40], reservations may arise when projects are of moderate size and resources are not fully dedicated.[

35]

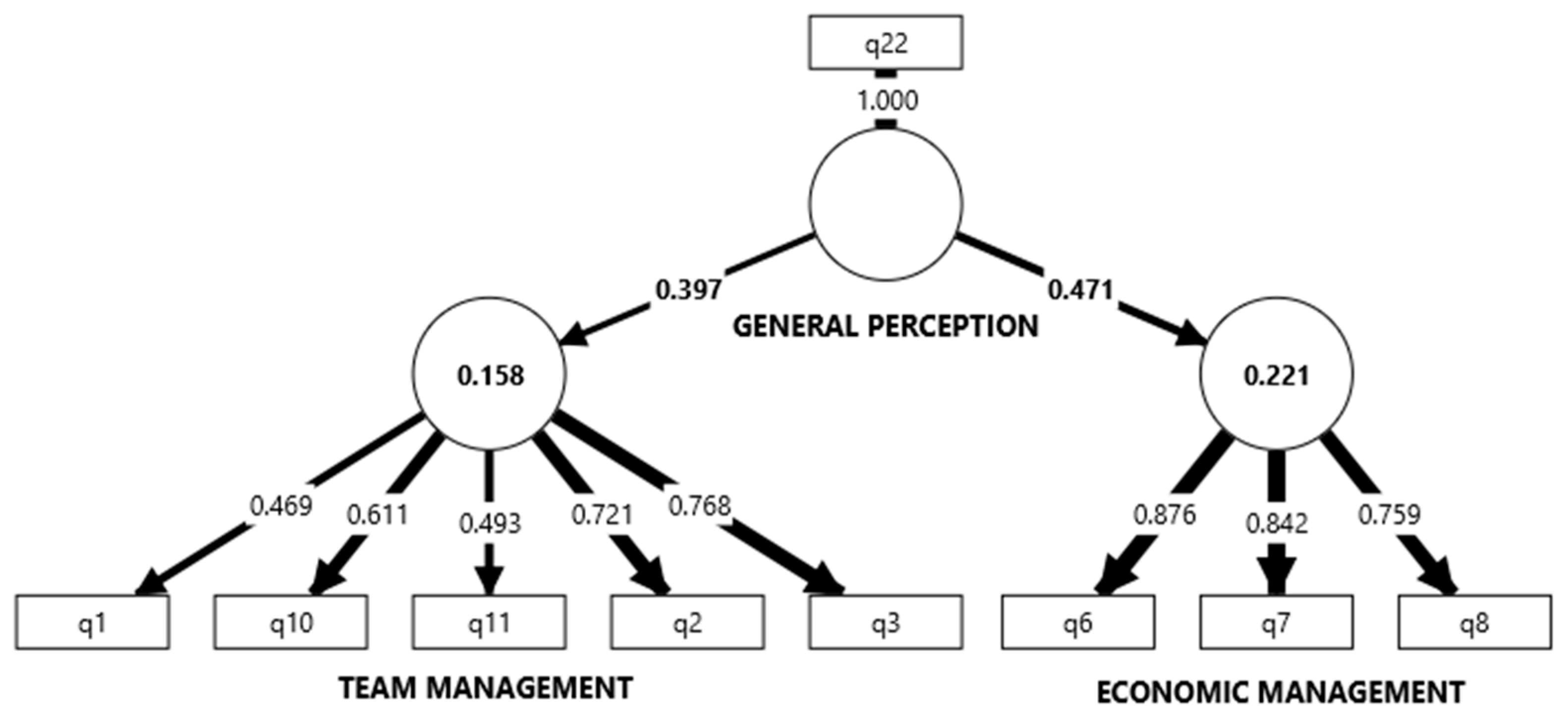

Figure 9.

The involvement of the contractor, the owner, and the architectural firm from the start of the project improves product definition, the integration of various technical solutions, team training, understanding of project objectives, understanding of costs, and the reduction of uncertainties and risks.

Figure 9.

The involvement of the contractor, the owner, and the architectural firm from the start of the project improves product definition, the integration of various technical solutions, team training, understanding of project objectives, understanding of costs, and the reduction of uncertainties and risks.

Figure 10.

Co-responsibility in decision-making improves the quality of decisions, reduces blame attribution, and prioritizes the project’s interests over those of individual parties.

Figure 10.

Co-responsibility in decision-making improves the quality of decisions, reduces blame attribution, and prioritizes the project’s interests over those of individual parties.

Figure 11.

Intensive owner participation—understood as attending work meetings as an active member of the team—improves understanding and accelerates decision-making.

Figure 11.

Intensive owner participation—understood as attending work meetings as an active member of the team—improves understanding and accelerates decision-making.

Figure 12.

Open-book accounting improves transparency and trust among stakeholders during the process. By eliminating economic tension between parties, it reduces the likelihood of one party attempting to profit at the expense of others.

Figure 12.

Open-book accounting improves transparency and trust among stakeholders during the process. By eliminating economic tension between parties, it reduces the likelihood of one party attempting to profit at the expense of others.

Figure 13.

Risk-reward compensation incentivizes collaboration and teamwork while prioritizing the project over the individual interests of the stakeholders.

Figure 13.

Risk-reward compensation incentivizes collaboration and teamwork while prioritizing the project over the individual interests of the stakeholders.

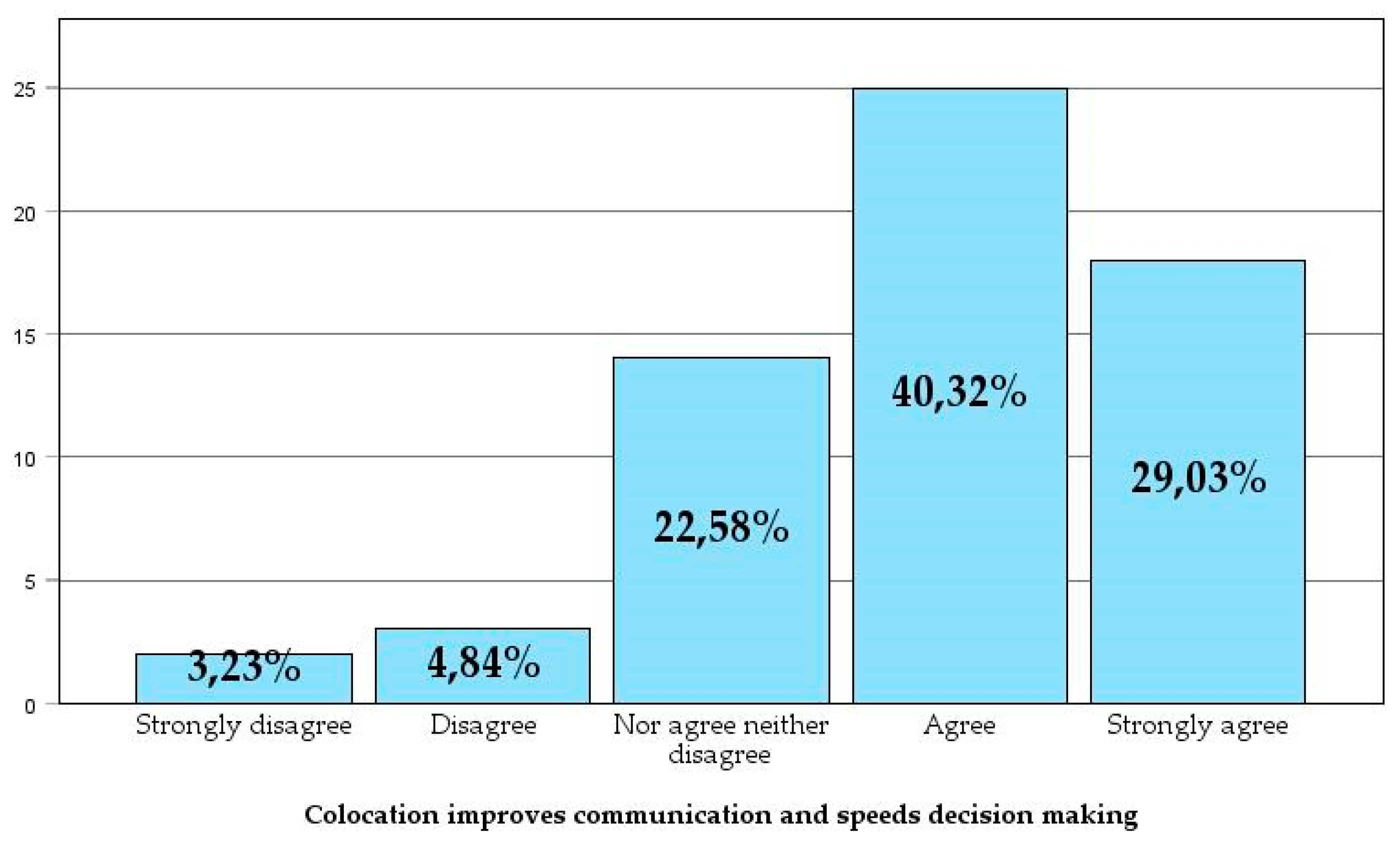

Figure 14.

Co-location enhances communication by accelerating the flow of information and decision-making while fostering a sense of teamwork and prioritizing the project.

Figure 14.

Co-location enhances communication by accelerating the flow of information and decision-making while fostering a sense of teamwork and prioritizing the project.

A total of 69.35% of respondents agree or strongly agree that co-location is beneficial for projects. Additionally, 40.32% agree that co-location, combined with intensive owner participation, improves communication by enabling faster information flow and accelerating decision-making. It also enhances the sense of belonging to the project, placing the project above individual organizations.

When asked about the economic feasibility of this strategy, 50% of respondents stated that it would be possible to cover the costs for projects within their organization, while 22.58% said it would not be feasible. A further 27.42% were neutral, indicating a division of opinions on this issue.

Most respondents (43.5%) remained neutral about whether co-location is desirable but not essential for Lean IPD, while 37.1% agreed and 19.4% disagreed.

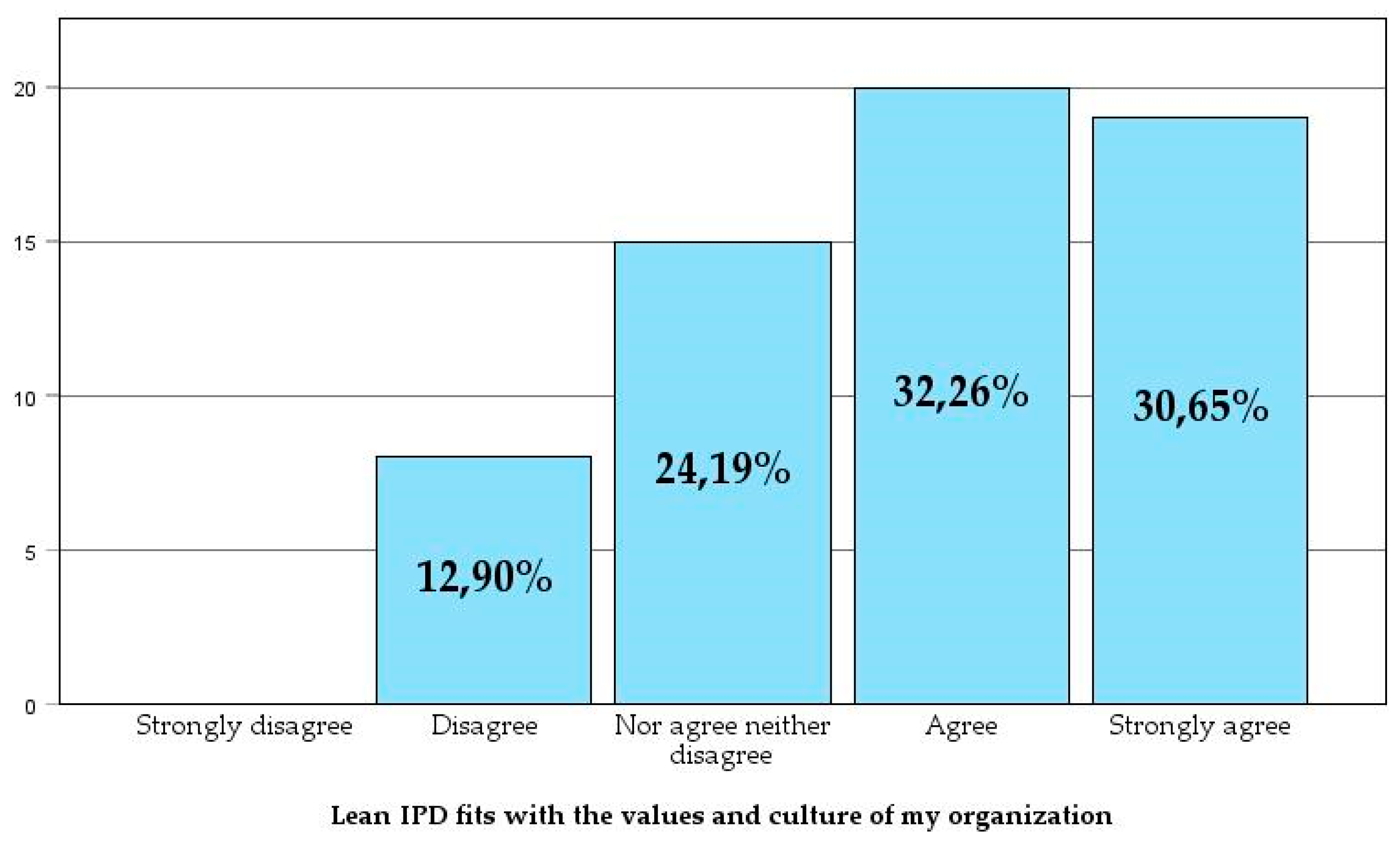

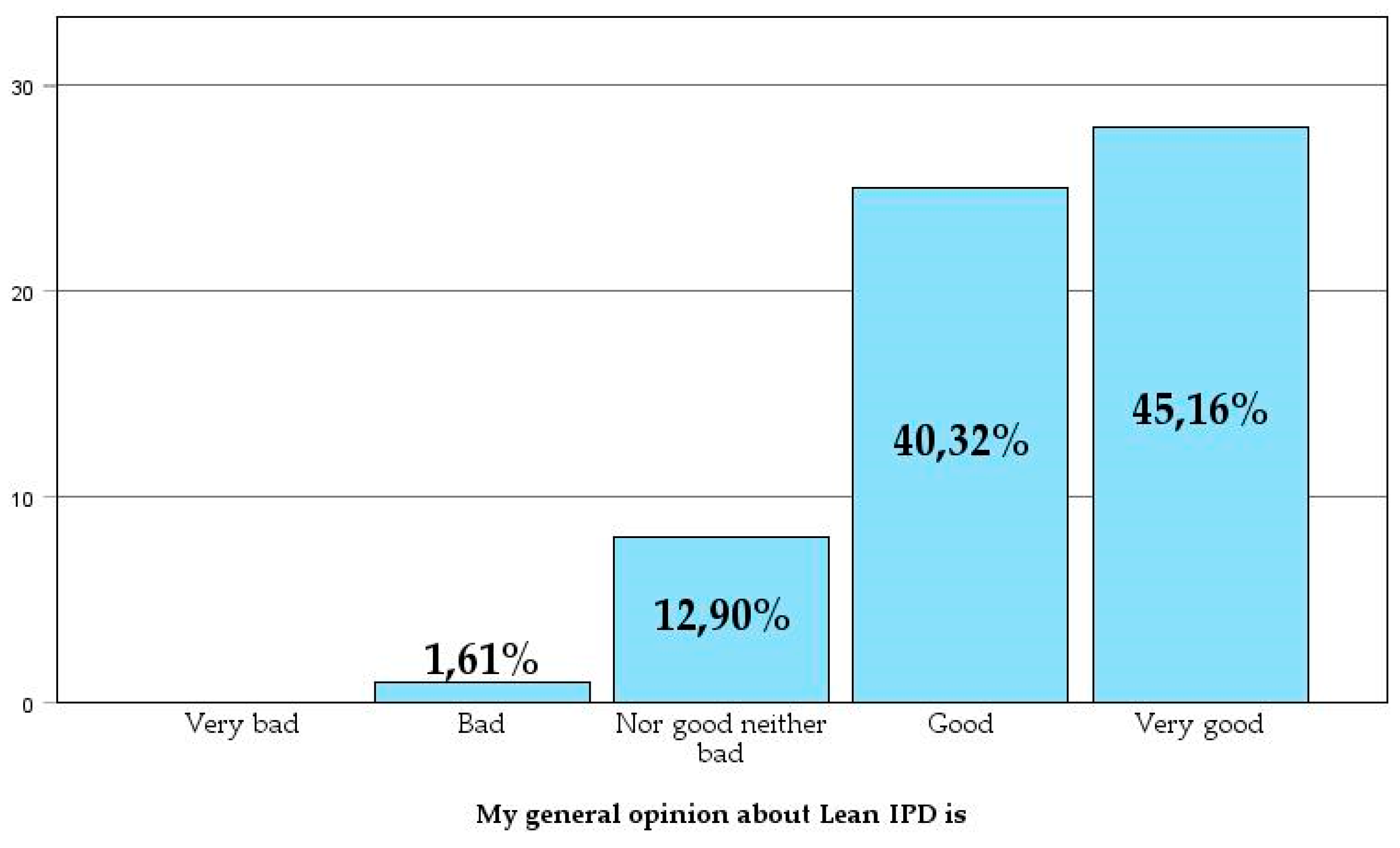

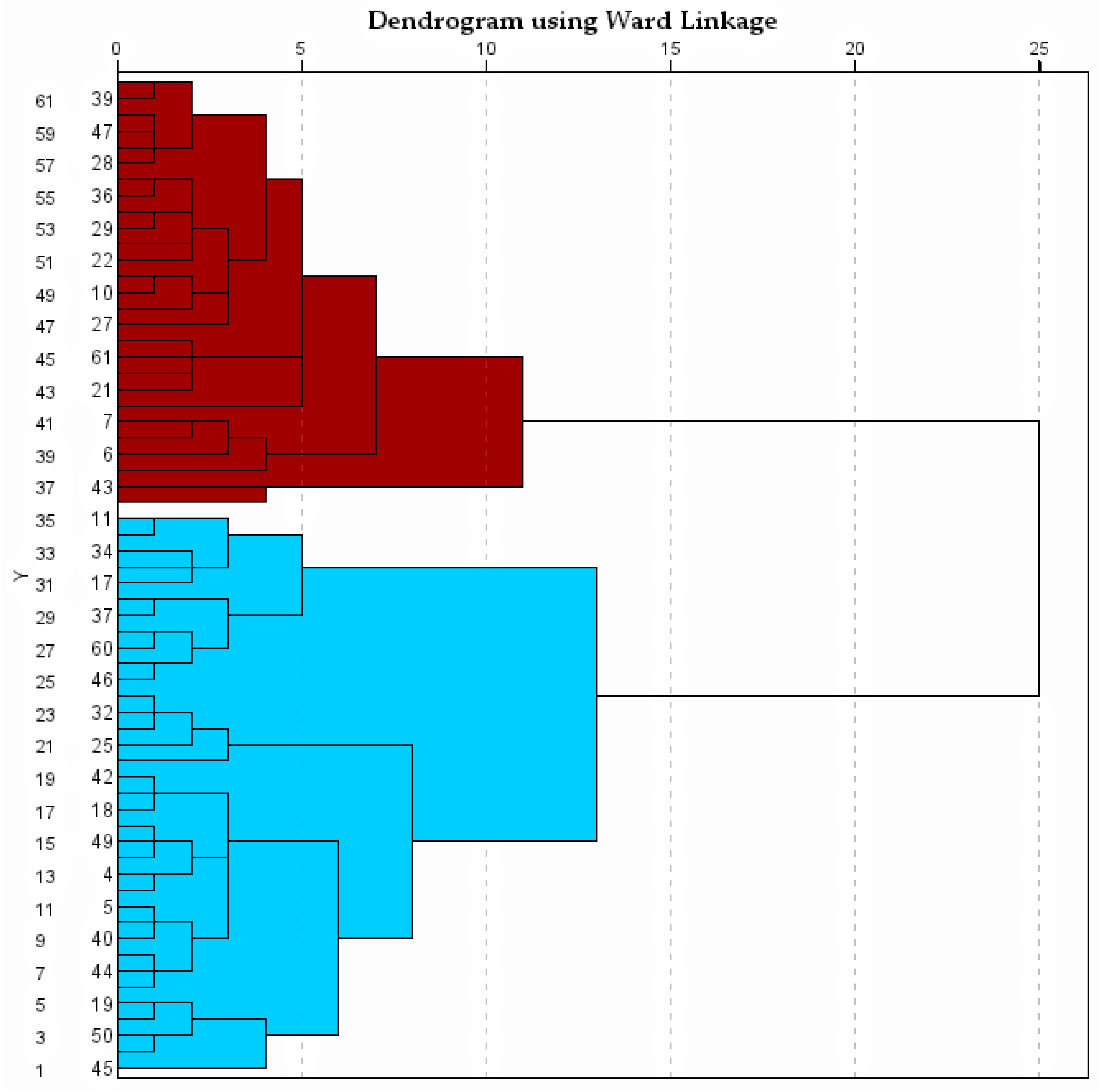

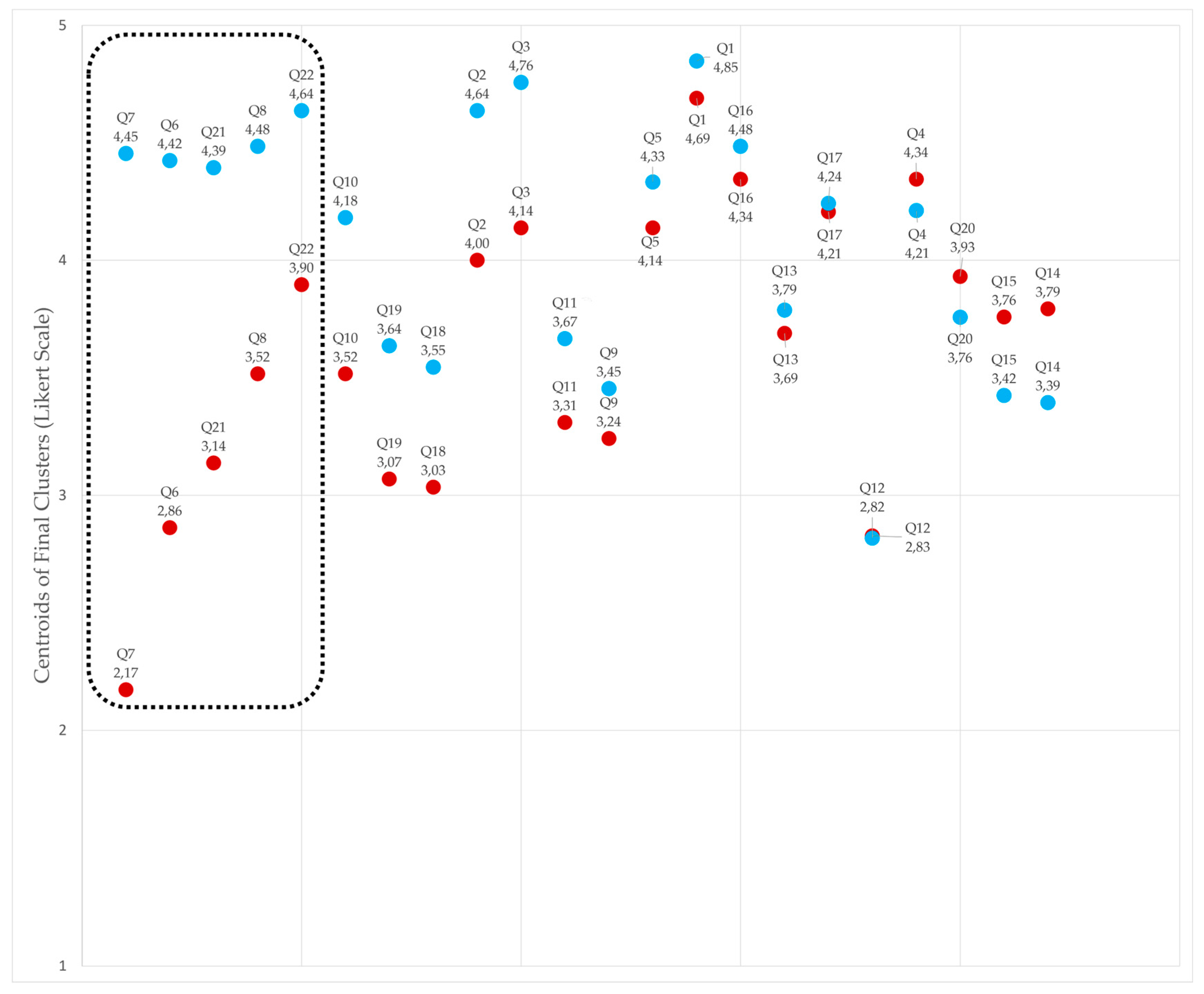

3.3.2. Industry Culture and Barriers to Implementation

The culture of the construction sector operates under the logic of zero-sum games, [

41] where for one party to gain, another must lose. This is largely because the Design-Bid-Build (DBB) delivery method has been adopted as if there were no other way to govern projects. However, the DBB method was not always the dominant paradigm; it only began to gain popularity after the Rural Post Roads Act of 1916, which aimed to minimize corruption in public procurement in the United States[

42]. Until well into the 20th century, projects often followed a much more collaborative approach [

43].

In Spain, the legal framework prescribes a single delivery method—DBB. While this method has been applied to all types of projects, it becomes inefficient in the face of the increasing complexity and uncertainty that many projects must handle [

44] and it is considered the least effective in terms of outcomes [

45]. Breaking projects into phases to seek the most competitive bid and assigning isolated responsibilities to each stakeholder has led to a scenario where, in the face of potential project failure, stakeholders prioritize their own interests over those of the project. The rules of DBB encourage opportunistic behaviors from all parties, resulting in distrust and, ultimately, conflict.

The culture of confrontation and lack of trust are seen as significant barriers to Lean IPD by the majority of respondents (56.5%). Respondents agreed that the confrontational culture, lack of trust, and entrenched behaviors of stakeholders are deeply ingrained. They also noted that a generational shift would likely be necessary for Lean IPD to reach its full potential. Nonetheless, 25.8% of respondents remained neutral. This suggests that these cultural issues are perceived as major obstacles that need to be addressed for the effective implementation of Lean IPD.

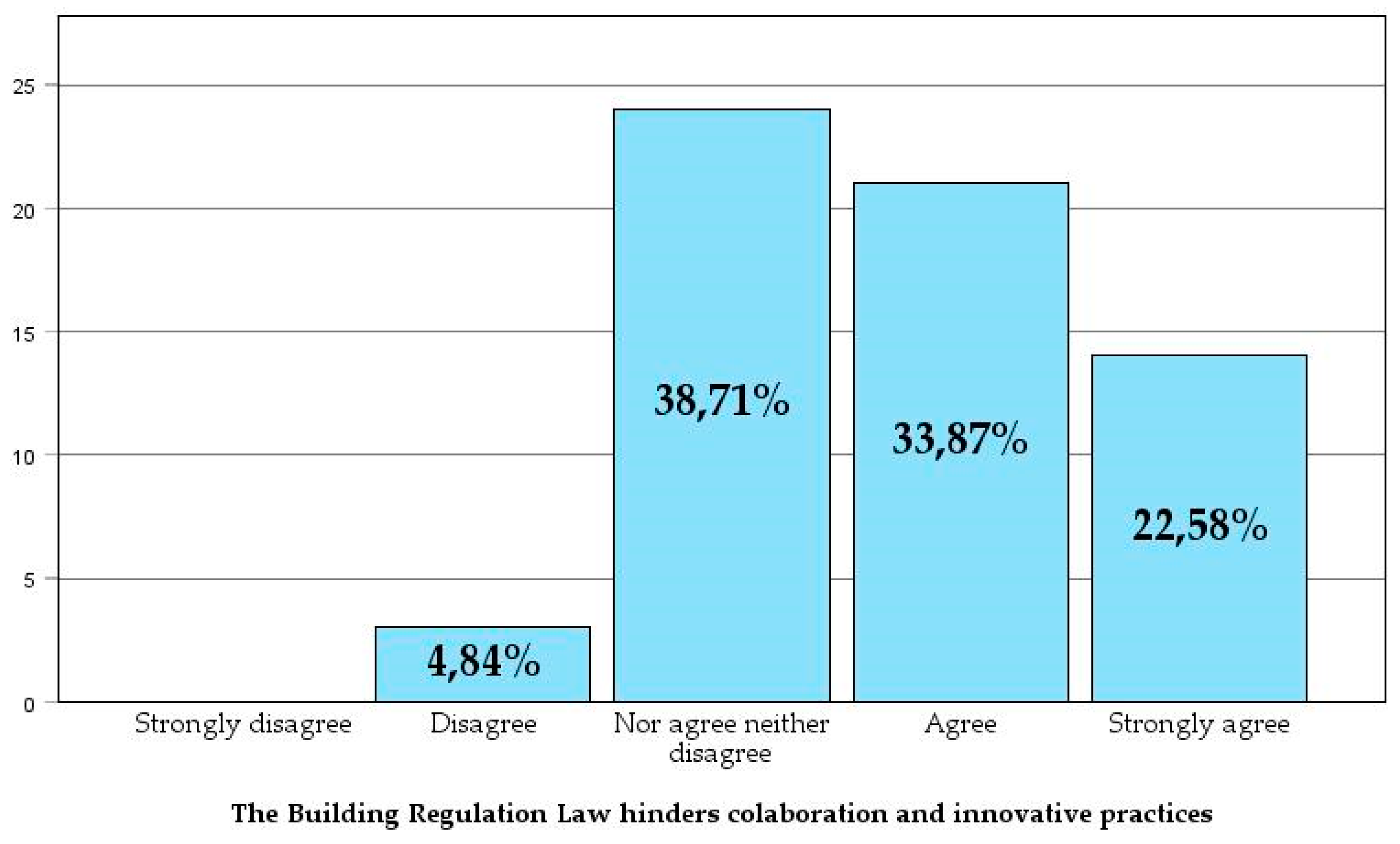

In Spain, the Building Regulation Law of 1999 (LOE) implicitly repeals the Civil Code of 1889 [

46] with the aim of regulating the design and construction processes of real estate properties. This law provides a limited list of Construction Agents and clearly defines their roles and responsibilities [

47]. Over the last 30 years, numerous roles and positions have emerged that were impossible to foresee at the time. Today, construction projects often include roles not covered by the law, such as Project Managers, sustainability consultants, certification entities, Lean Construction consultants, Quantity Surveyors, Cost Managers, BIM Managers, and a wide range of specialists who address the increasingly complex demands of real estate projects.

For many professionals and academics, the restrictive nature of the definition of Construction Agents in the law, along with its Napoleonic approach to assigning responsibilities, presents barriers to innovation [

48] and raises significant doubts about the implementation of collaborative contracting [

49].

Most respondents (56.45%) agree or strongly agree that the responsibilities described in the LOE for various construction agents hinder innovation in contract design, compared to the Common Law systems in Anglo-Saxon countries, which allow greater flexibility. However, 38.7% remain neutral, which could indicate uncertainty or a lack of clear information about the impact of the LOE.

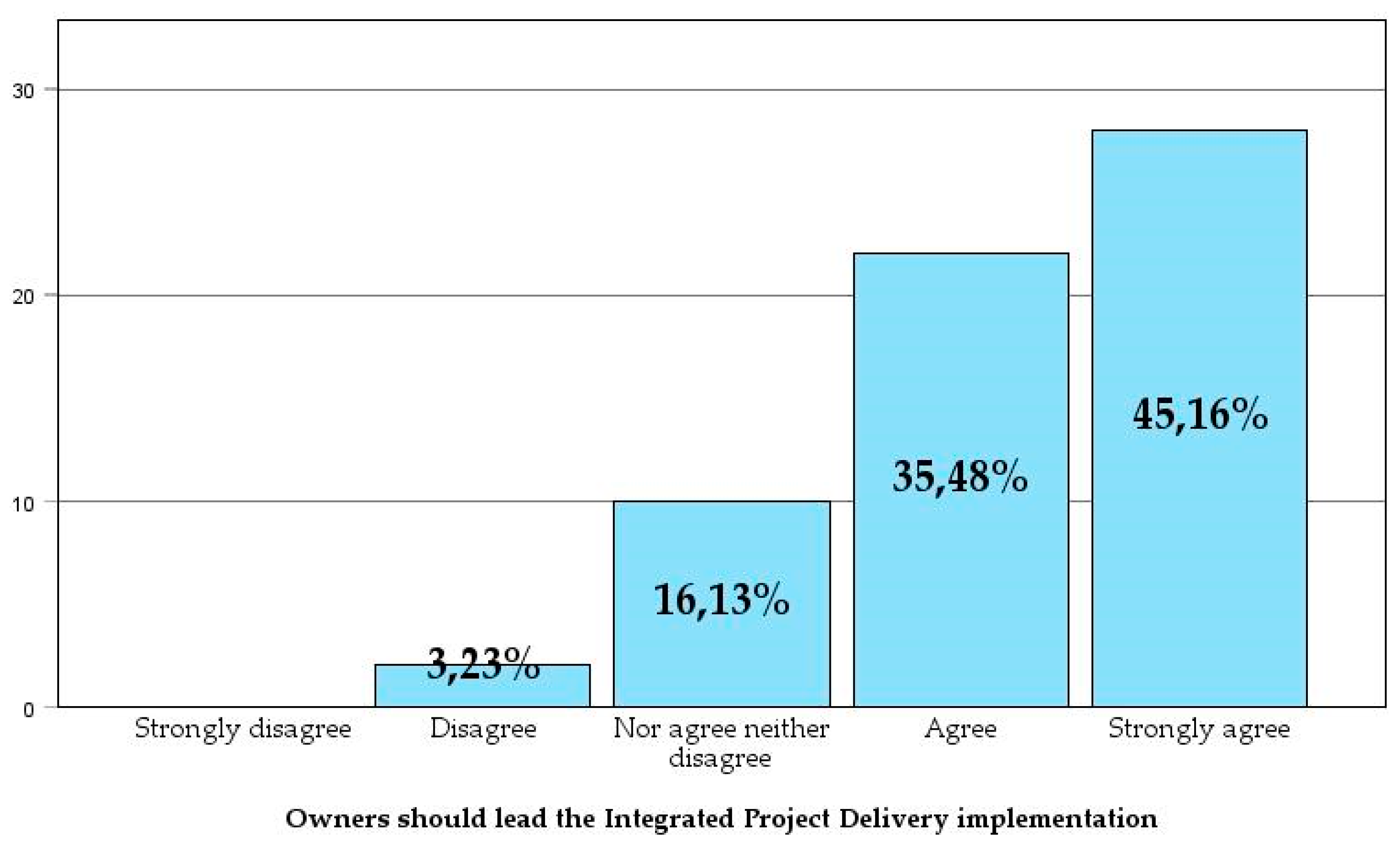

The cross-disciplinary nature of Lean IPD's implementation may raise questions about who should drive this paradigm shift, whether it should be a collaborative effort or led by a specific stakeholder. A recent precedent can be found in the mid-2010s when architectural firms and engineering companies led the adoption of BIM, despite limited demand from their clients[

50].

Maturity in Lean Construction is not something that will be achieved overnight. Similarly, the adoption of Lean IPD will encounter many types of barriers. But who should be the figure to lead this transformation?

A total of 80.7% of surveyed owners agree or strongly agree that real estate owners should take on the role of driving Lean Construction and IPD, indicating strong expectations for these actors to lead the adoption of these methodologies.

It is possible, and often the case, that in their effort to improve outcomes, contractors take the initiative to implement Lean Construction techniques such as the Last Planner System, 5S, or Takt-Time. These changes can have a positive impact on a limited portion of the production process. However, the design of relationships between various stakeholders and the governance principles of projects should align with the owner's corporate philosophy.

Owners should ask themselves this question: Do we want to build stable, long-term teams of collaborators who treat the company's projects as their own, or do we prefer to seek the highest bidder for each project?

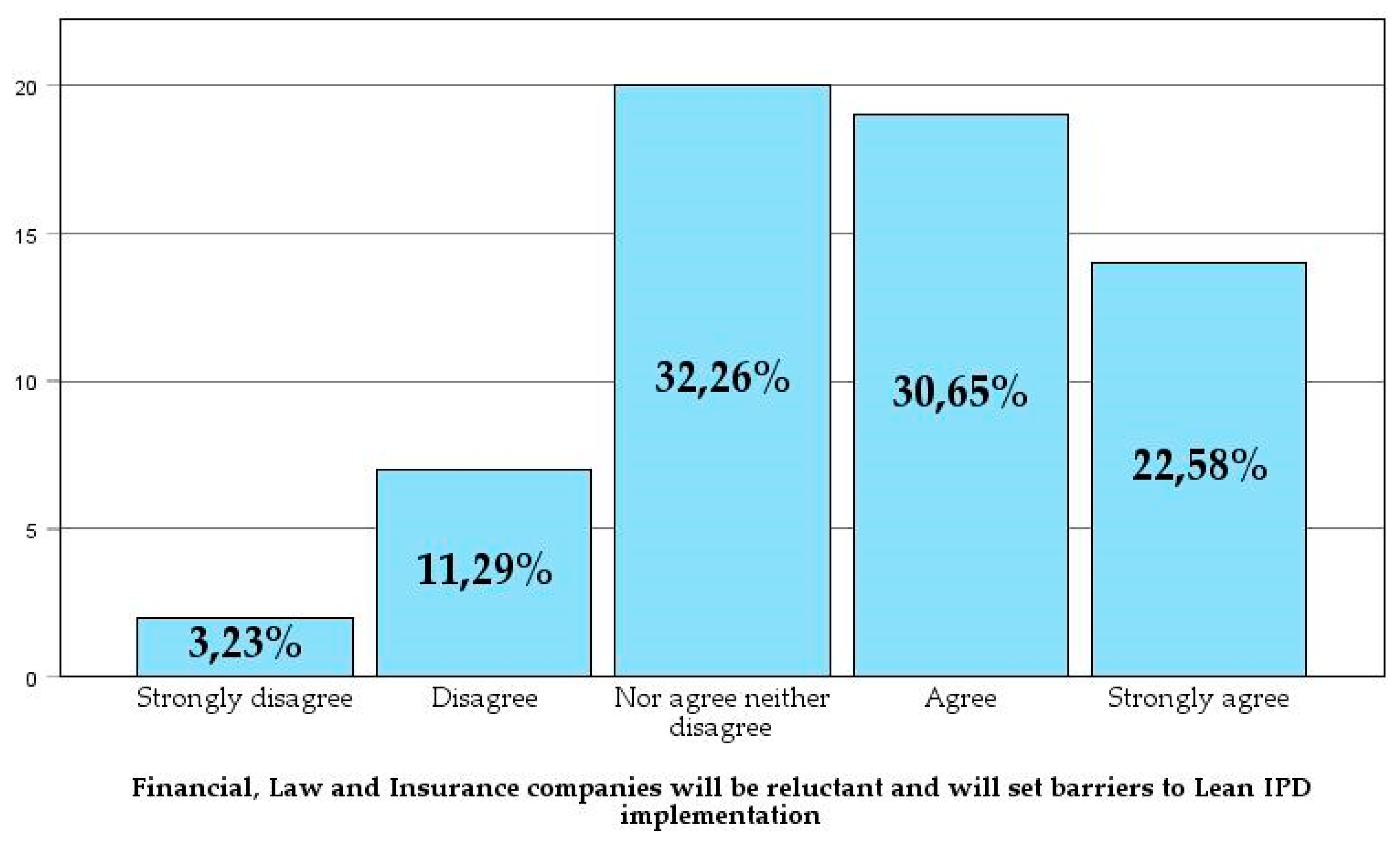

Construction projects are complex, and increasingly so [

51]. In addition to the traditional objectives of time, cost, and quality, new goals have emerged, such as building wellness, ESG objectives, corporate social responsibility, brand reputation, and end-user satisfaction. Financial needs and risk aversion have also evolved, giving greater importance to actors like banks, law firms, and insurance companies in the construction process. Significant changes, such as those proposed by Lean IPD during the design and construction phases, could intimidate these non-technical stakeholders and potentially introduce new barriers to Lean IPD’s advancement.

A total of 53.3% of owners agree or strongly agree that banks, lawyers, and insurers represent a significant barrier to the implementation of Lean IPD and that it will be challenging for them to understand it. However, 32.26% of respondents are neutral, and 14.23% disagree or strongly disagree. This indicates a perception of moderate resistance from these institutions, with only a slight majority holding this view.

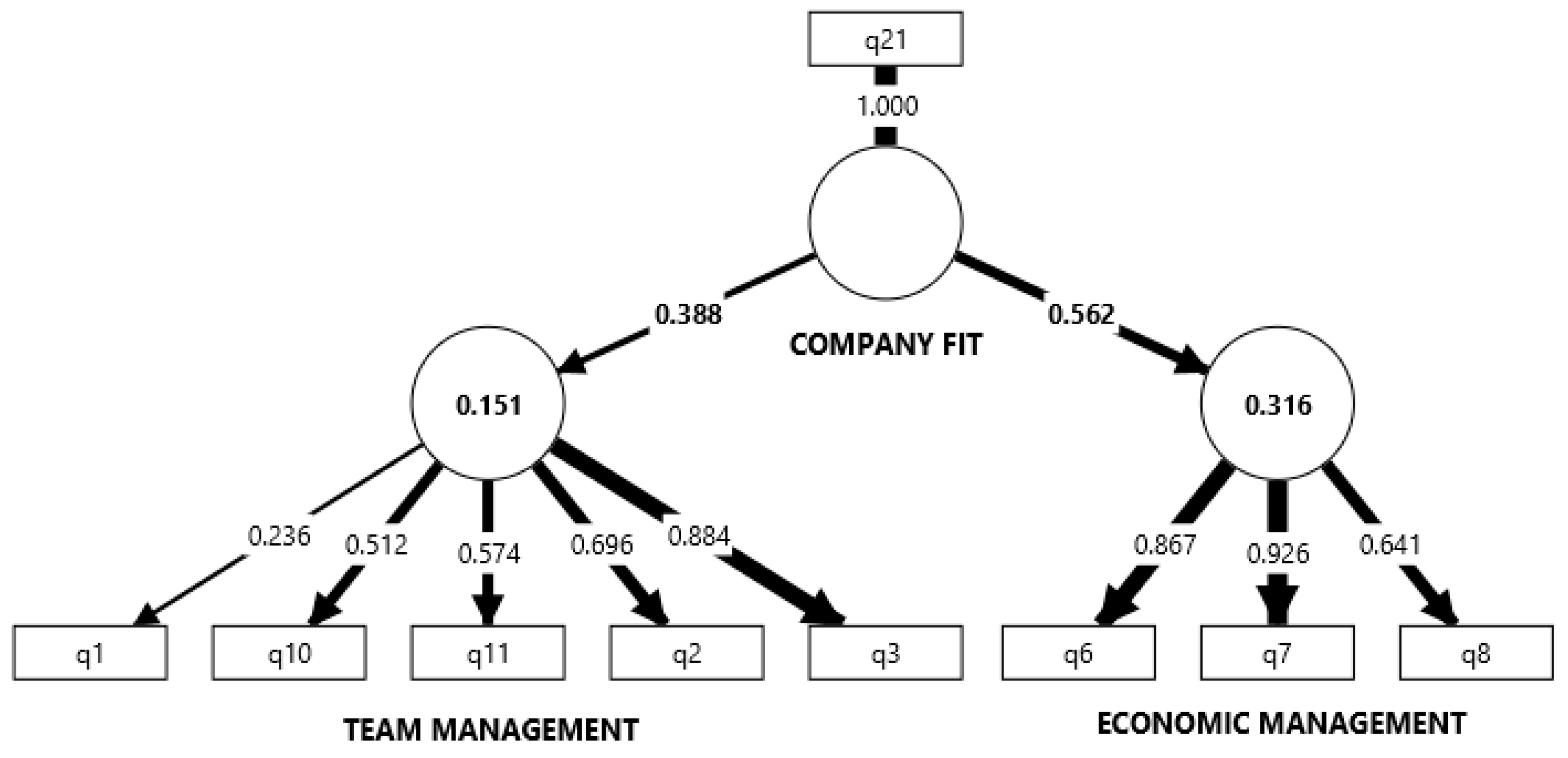

Figure 15.

The responsibilities described in the LOE for various construction agents hinder innovation in contract design compared to the Common Law systems in Anglo-Saxon countries, which allow greater flexibility.

Figure 15.

The responsibilities described in the LOE for various construction agents hinder innovation in contract design compared to the Common Law systems in Anglo-Saxon countries, which allow greater flexibility.

Figure 16.

The owner is the key figure who must drive Lean Construction and Integrated Project Delivery for their own benefit.

Figure 16.

The owner is the key figure who must drive Lean Construction and Integrated Project Delivery for their own benefit.

Figure 17.

Banks, lawyers, and insurers are a significant barrier to the implementation of Lean IPD. It will be very challenging for them to understand it, and they are likely to impose considerable resistance.

Figure 17.

Banks, lawyers, and insurers are a significant barrier to the implementation of Lean IPD. It will be very challenging for them to understand it, and they are likely to impose considerable resistance.